Abstract

Allergies have been linked to immune dysfunction, genetics, and environmental factors. However, environmental exposures are often highly correlated similar to genetic predictors making the cumulative assessment of exposures difficult. Here, we aim to investigate the relative contribution of genetic variants as well as different individual and environmental factors on the presence or absence of allergies in 450 elderly German women enrolled in the SALIA cohort study living in the Ruhr area by using genetic risk score (GRS) and exposomal risk scores (ERS). We used the novel cross leverage scores (CLS) to select genetic variants to be included in the GRS. The weights of the risk scores were obtained through bootstrapped and cross-validated ridge regression. We characterized the relative contributions of the risk scores to presence of allergies such as atopic dermatitis, asthma, or allergic rhinitis using McFadden’s Pseudo R-squared. Overall, our model was able to explain 11.13% of the variance of allergy diagnosis. The modest variance explained is consistent with prior work on complex polygenic and environmentally influenced traits, reflecting that no single exposure or domain is likely to fully capture individual risk. The GRS had the highest relative contribution at 3.80%, followed by the meteorological risk score with 1.13%. This method can easily be adapted to other diseases and can facilitate health risk assessments of exposomal factors. In addition, the results may aid policy-making, for example, by regulating specific sources of exposure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Allergic conditions arise when the immune system inappropriately responds to a normally harmless substances or allergens1. This response activates the immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated pathways and the release of inflammatory mediators such as histamine. This hypersensitivity reaction can lead to a range of clinical manifestations, including atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, or collectively known as the atopic march. Allergies have multi-factorial etiology, including immune dysfunction, sex hormones, genetic predisposition and environmental factors2. As documented by previous cohort studies, atopic march typically begins during childhood3,4,5,6. During this period boys were observed to have higher prevalence of allergic diseases than girls until puberty when the trend switches7,8. The increase of incidence and severity of allergic diseases among women has been attributed to female sex hormones which can amplify immune response contributing to airway hyperresponsiveness, inflammation, and increased mucus production9,10,11. There is an evidence gap specifically addressing allergies in elderly women which further highlights the need for more research, a population that remains underrepresented despite its relevance for understanding late-life allergy patterns.

Moreover, adult-onset atopic diseases can also be driven by environmental exposures. Several epidemiological studies have shown that environmental factors (e.g. air pollution, meteorological factors, green space, etc.) are also strongly associated with existing allergies as well as the new development of allergies12,13,14. Specifically, air pollution and climatic factors are linked to allergies in children14. The strongest associations were found for the air pollutants nitrogen dioxide (NO2), particulate matter of an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 μm or less (PM2.5) and ultrafine particles as well as temperature15. Changes in temperature has been associated with longer pollen seasons and skin barrier dysfunction16,17. In Germany, where allergic rhinitis is the most common allergic disease, climate change is seen to indirectly influence allergy incidence18. Additionally, factors such as active smoking or exposure to secondhand smoking have also been associated with higher risk of atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis19,20.

The environmental exposures are often highly correlated, which causes collinearity of the exposure variables and makes the cumulative assessment of the effects of multiple exposures on health outcomes difficult. One challenge in environmental epidemiology is estimating the independent effects of many correlated exposures. General approaches include assessing each exposure in separate models, adjusting for other exposures domains, or assessing all exposures simultaneously in a single model such as semi-Bayes modeling. However, often the optimal strategy remains uncertain and the combined effect of exposures is not studied.

In addition, the genetic make-up is involved in the pathogenesis of allergies21,22. Genetic risk scores (GRS) were developed for determining the cumulative genetic effect on a trait or disease23. Methodology initially developed for genome-wide analyses can also be useful for analyses of environmental exposures, since environmental predictors are also highly correlated similar to genetic factors. In a previous study24, the GRS methodology was adopted for assessing the extent to which various domains of exposomic factors contribute to health outcomes, building risk scores (RS) from several correlated exposure variables to assess the cumulative effect of one domain. Here, we extend this approach and explore its utility on binary health outcomes. Moreover, instead of select relevant SNPs based on previous genome-wide association studies, we use a new screening approach, called cross leverage scores (CLS), incorporating all available SNPs simultaneously.

Joint modeling genetic predisposition and environmental exposures is necessary in the context of allergic diseases development. While allergies are triggered by environmental exposures, genes have the imprint on immune recognition, barrier function, and inflammatory responses that determine how the body respond to these triggers. As a complement to genome, the exposome captures the totality of exposures in providing a more comprehensive understanding of disease etiology and its multifactorial nature25,26. In fact, recent study comprising 14 European cohorts demonstrated that an ERS integrating multiple external exposome domains was associated with higher incidence of asthma27. As such, we aim to use an exposomic approach considering different domains of exposures, along with genetic risk, in identifying their relative contribution to allergies. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to look at both genetic and multiple exposomic factors on allergy. Ranking the different contributions of exposures may aid health risk assessment of allergies and aid policy-making by identifying which domains of exposures should be prioritized in setting limit values.

Materials and methods

Cohort data

In this article, we used the second follow-up examination of the SALIA cohort study (Study on the influence of air pollution on lung function, inflammation and aging) from 2007 to 2010 comprising of 450 German elderly women from the Ruhr area and Southern Münsterland with available genetic data. The elderly women were first recruited when they were aged 54–55 in 1985. Men were not recruited to avoid bias due to occupational exposure since the setting was a German region with mining and steel industry at the time. More details on the SALIA cohort can be found in previous studies28. The cohort study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ruhr University, Bochum (protocol code 2732 and date of approval: 4 April 2006) and the Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf (protocol code 3507 and date of approval: 24 November 2010) for studies involving humans. All women gave their written informed consent before the investigation. The primary outcome of this study is an existing or previous physician’s diagnosis of an allergy, which includes bronchial asthma, atopic dermatitis/eczema, and allergic rhinitis/hay fever. Participant’s information on age, body mass index (BMI), and socioeconomic status (SES) were derived from the cohort interview questionnaire as single predictors or fixed confounding variables in our models. For the current analysis, a participant was classified with high SES if she or her partner’s number of school years is 10 or more years, and low SES otherwise. In addition, responses on smoking behavior questions such as currently smoking, number of pack-years, formerly smoking, and exposure to secondhand smoking, were used to develop a Smoking Risk Score.

Genetic assessment

Genome-wide genotyping was performed in 752 from different biological samples (venous blood, saliva from buccal swab or Oragene collection kit OG-500) at different time points using the Axiom Precision Medicine Research Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) (GRCh37/hg19) resulting in 871,262 variants. After quality controls29 and genotype imputation against the Haplotype Reference Consortium using the Michigan Imputation Server30, 586 individuals and 7,643,653 SNPs remained. The full set of almost 8 million SNPs were screened using Cross Leverage Scores (CLS). This procedure detects the most influential SNPs on a health outcome through a computationally efficient sketching approach based on QR-decomposition31. Specifically, the CLS of the ith SNP is determined by the dot product of rows Qi. and Qp*., where matrix Q is the orthonormal basis for the column space of the binded matrix [X y]T. The advantage of using CLS over performing multiple testing of p-values from simple (generalized) linear models is that it uses all of the hundred-thousands of SNPs and, thereby, inherently considering the interaction effects, in the computation of each SNP importance. In this study, we selected the 300 SNPs with the highest absolute CLS of the allergy-associated SNPs. In addition, we also took into account the first 10 principal components of the genotype matrix to control for population structure during CLS computation. The top 300 SNPs are then filtered after pruning with linkage disequilibrium threshold of 0.20 using the SNPRelate32 R package. SNPs included in the GRS are annotated with their corresponding or nearest gene using Ensembl33 of the biomaRt Bioconductor package implemented in R.

Exposure assessment

To build the air pollution risk score, air pollutants (e.g., PM2.5, PM10, and NO₂) were estimated using the optimal interpolation method at a spatial resolution of 2 × 2 km2. These estimates were provided by the German Environment Agency (Umweltbundesamt) and rescaled to a spatial resolution of 1 × 1 km234. In terms of meteorological risk score, the ambient temperature and humidity data of 6 × 6 km2 resolution were extracted from Consortium for Small-scale Modeling – Regional Reanalysis 6 (COSMO-REA6)35. Specifically, for both air pollution and meteorological variables, estimated levels were assigned to participants’ geocoded home address to minimize spatial exposure misclassification and we use the average of 1 year prior and the average of 1 month prior to the examination date to reduce temporal misclassification. For the greenness risk score, we included the normalized difference of vegetation indices (NDVI) of varying buffers: 300 m, 500 m, 1000 m around participants’ residence to capture local variation in greenspace exposure.

Bootstrapping and splitting into training-testing samples

Following a stratified bootstrap method, all analysis is repeated B times. For this analysis we repeated B = 200 times for computational efficiency since in each bootstrap we do 10 replications to reduce variation due to folds as described below. This number of iterations was also used before24 and seemed to yield stable results. Stratification means that the bootstrapped datasets are generated by randomly selecting participants from the original sample with replacement while maintaining the baseline proportion of cases and controls. The observations in each of these bootstrap replicates are then randomly split into training (60%) and test (40%) sets, in accordance with the recommendation from Dudbridge23. The training samples are used to learn the risk score weights while the relative contributions of the risk scores are assessed in the testing sample as further discussed in the following subsection.

Training for risk score weights

To determine the weights in their respective risk scores, a cross-validated logistic ridge regression is utilized using the glmnet36 R package. The model solves the optimization problem with an L2 penalty term and addresses potential multicollinearity among the variables. The parameter λ determining the strength of the penalty of ridge regression is tuned through 10-fold cross-validation. Within the folds, the ratio of cases and controls is still maintained. Following the principle employed by Wigmann24, the estimation of coefficients or weights is repeated ten times and average to reduce the randomness due to the folds. Then for every risk score, the respective subsets of weights are normalized so that the resulting weights sum to one.

Relative contributions of risk scores in the test sample

Based on the logistic linear model of the risk scores (RS) explaining the binary allergic outcome y, i.e., log((π(y))/(1-π(y))) = β0 + β1 Age + β2 BMI + β3 SES + β4 Smoking RS + β5 Air Pollution RS + β6 Meteorological RS + β7 Greenness RS + β8 GRS + ϵ, dominance analysis is performed using the R package dominanceanalysis37. Dominance analysis compares the R-squared of all possible subset models of the full model. In the process, it decomposes the overall measure into relative contributions of each predictor.

In the logistic regression context, we use McFadden’s Pseudo R-squared, also called as deviance R2, among other pseudo R-squared statistics since it reflects the “variance-accounted” for the logistic regression model. Mathematically, McFadden’s is given by R2 = 1-L1 /L0 where L1 is the full-model log-likelihood and L0 is the intercept-only log-likelihood. In addition, it was previously shown that the measure is relatively independent of the base rate of the binary outcome variable compared to other Pseudo R-squared indices38. This may be crucial when the analysis is applied to cohorts with unbalanced outcome data such as allergies.

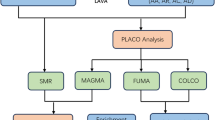

From 200 bootstrap replications, median relative contributions of the predictors and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (C.I.) are estimated. Similarly, the median regression coefficients and confidence intervals are estimated. See Supplementary Fig. S1 for the analytic workflow of the study.

Sensitivity analyses

Based on previous studies, which showed that the relative contribution of GRS tends to be much higher than that of the remaining risk scores, a sensitivity analysis was conducted without the GRS. In addition, we performed a sensitivity analysis with broader definition of having allergies where participants who had total IgE level > 100IU/L, but not necessarily a diagnosed allergy are also considered cases.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Among the 450 participants with available genetic data, 94 (20.89%) have been diagnosed with an allergic disease. Among those with an allergic disease, the most common allergy was allergic asthma (48%), followed by allergic rhinitis/hay fever (45%) and atopic dermatitis/eczema (22%). A total of 13 participants have more than one manifestation: one woman with eczema, rhinitis, and asthma; seven with eczema and rhinitis; three with both eczema and asthma; two with both asthma and rhinitis.

Table 1 shows the descriptive summary of the participants, as well as cross-tabulation by their allergic status. The women were at a mean age of 73.9 (SD = 2.8) years during the second follow-up examination with mean BMI of 27 kg/m2 or mildly overweight across both case and control groups. Those without allergies (83%) had a higher percentage of high socioeconomic status (SES) than those with allergies (47%). Women with allergies had a higher number of cigarette pack-years than women without allergies.

Air pollution variables were generally higher in the residential areas of those with allergies. For meteorological variables, there is a contrasting trend. For SNPs included, it is expected to have a pattern in their mean number of variants since the relevant SNPs were already selected using cross leverage scores (CLS).

Genetic risk score (GRS)

After pruning the 300 SNPs with the highest CLS, only 50 SNPs remain to be included in the constructed GRS. Supplementary Table S1 shows that rs10759210 has the highest absolute CLS.

To investigate the role of the SNPs in the constructed GRS, the median normalized weights of these SNPs after being trained in logistic ridge regression across 200 bootstraps are shown. See Supplementary Fig. S2 and Table S1. The magnitude of the weights of the SNPs ranged from − 0.023 to 0.055 and multiple SNPs are used to explain or predict the allergic disease of the patients. rs2780980 achieved the highest positive normalized weight while rs6065705 had the most negative normalized weight.

Among the genes that were annotated to the SNPs in the GRS, the RAR-related orphan receptor A (RORA) gene had the most extensive literature on being associated to allergies in humans and mouse models. The expressed gene restrains allergic skin inflammation and influence immunologic features of asthma39,40.

Exposomal risk scores (ERSs)

Based on the normalized weights of the pollutants in the Air Pollution RS, these were mostly positively weighted with the monthly mean exposure to NO2 having a median weight of 0.29. See Fig. 1. On the other hand, factors in the Smoking RS did not show clear directions except for pack-years and active smoking which are negatively weighted on average. For the Meteorological RS, there is a consistent pattern as in the descriptive analysis where monthly mean relative humidity and annual temperature are weighted positively while monthly mean temperature and annual relative humidity are weighted inversely. Meanwhile, the weights of the variables in the Greenness RS such as NDVI at 300m2 and at 500m2 lean more positively.

Determining the relative contribution in the testing sample

Building several risk scores effectively reduced the correlation between predictors as they are contained within the risk scores. See Supplementary Fig. S3. Only the Air Pollution RS has a low positive correlation with Meteorological RS.

Based on the fitted model in the test sample, all the risk scores and the single predictors “explain” 11.13% (3.05, 21.42) of the variance (See Fig. 2). In the technical sense of using McFadden’s Pseudo R-squared, the fitted model indicates this percentage improvement in log-likelihood relative to an intercept-only model. The GRS has the highest contribution with median of 3.80% (0.12, 11.40). This indicates adding the genetic risk score provided the largest gain in the model fit, suggesting it may be the most useful single marker for improving risk stratification. At second, Meteorological RS has a relative contribution of 1.13% (0.05, 6.32). This was followed by Air Pollution RS with relative contribution of 0.73% (0.03, 5.07). The constructed Greenness RS contributes to allergy relatively at 0.58% (0.02, 4.58) while Smoking RS has a median relative contribution of 0.39% (0.01, 3.12). The single predictors, namely BMI, Age and SES have the least relative contributions with medians of 0.35% (0.01, 3.78), 0.32% (0.03, 2.73), and 0.03% (0.01, 2.50), respectively. Across the 200 bootstrap replicates, all models with risk scores in the test split converged.

The GRS is significantly associated with the diagnosis of allergies [OR: 2.06 (1.15, 4.21)] in the fitted model. See Fig. 3. On the other hand, the ERSs and single predictors are not significantly associated based on the bootstrap confidence intervals. In terms of median estimate, we note that the Meteorological RS [OR = 1.50 (0.71, 4.43)], Air Pollution RS [OR = 1.19 (0.51, 2.99)], and Greenness RS [OR = 1.26 (0.58, 2.44)] have odds ratios greater than 1 which implies that on most models across the 200 bootstraps they are contributing risk to having allergies. In contrast, BMI [OR = 0.88 (0.53, 1.33)] has odds ratio below 1 and is inversely related to diagnosis of allergies. The remaining risk scores have odds ratio very close to 1 i.e., Smoking RS = 1.00 (0.57, 1.72), SES = 0.98 (0.69, 1.60), and Age = 0.97 (0.62, 1.59).

Sensitivity analysis

After removing the GRS from the analysis, the relative contributions of ERSs remained small as shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. The model containing only the ERSs and individual factors as single predictors explains 6.50% (1.19, 14.08) of the variance. There were little changes in the median relative contribution estimates of the risk scores. In terms of ranking, only the low-contributing single predictors Age and SES have switched. This sensitivity analysis shows that, still, none of the ERSs and predictors were significantly associated with allergies. See Supplementary Fig. S5.

Using a broader definition of allergic cases that included participants with high IgE levels, we found that the proportion of cases increased from 20.89% to 27.11%. Considering this outcome, the model showed a slight decrease in the overall percentage explained by the fitted model to 10.97% (3.60, 22.20). The relative contribution of GRS did not change much with a median of 3.84% (0.28, 11.81). Similar to the main model, only the GRS has a significant association to allergies. Supplementary Table S3 shows the relative contributions and odds ratio of the risk scores and predictors in this sensitivity analysis.

Discussion

Overall, the proposed approach was able to demonstrate how to quantify the contributions of genetic factors and several domains of exposures to allergy in terms of percentage of explained variance. In this SALIA cohort, the model containing GRS and ERSs showed modest improvement of model fit on explaining allergic diagnosis in elderly German women.

GRS, through CLS-screened set of SNPs, attained the highest relative contribution among other risk scores. Several genome-wide association studies already support the genetic influence in allergies as SNPs from different loci relevant in the epithelial barrier, innate-adaptive immunity, IL-1 family signaling, regulatory T cells, and vitamin D pathway have been identified41,42.

Even after excluding the GRS in a sensitivity analysis, the relative contributions of ERSs are still low. Since the outcome used in the cohort is defined as prevalence (or being ever diagnosed of allergy), the impact of meteorological risk score and air pollution risk score is likely to have been understated. The measurements of the included variables were derived only on the most recent year and month before the data was collected, which may not capture the biologically relevant exposure windows. Several literature support that atopic march often develops in early childhood which indicates that the exposure window for allergies are more susceptible at this time3,43,44. However, recent studies show that it could develop at any age which means that for elderly it might take a more long-term or longer lagged exposure to air pollution and climatic factors45,46. Notably, other confounders such as diet, medication use, and exposure to house dust mite allergens were not considered in the model which may underestimate the overall variance in explaining allergies.

Gene-environment studies on allergies in adults are scarcer compared to children and adolescents. In both populations, we were not able to find any study on allergies that compared the relative contribution of genotype data and environmental exposures. Existing studies usually examine genetic risk through a single variant or a GRS along with an environmental variable. For example, variant in PID1 gene have been associated to asthma related to exposure to irritants47. Likewise, SNPs in IL1RN gene have been linked to asthma risk in settings with tobacco smoke exposure during childhood48. Among infants, it was found that prenatal exposure of mothers to indoor PM10 and a GRS for asthma reduces lung function49. For childhood asthma incidence, the main effect of GRS for asthma was significant but not the main effects of air pollutants in one study50. In another study, the main effects of traffic-related NO2 and PM2.5 were significant to asthma among children and were linked to higher genetic susceptibility in the GSTP1 gene51. Meanwhile, exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in early life was associated to higher risk of early-onset asthma considering variants in 17q21 locus52. Consistent with these studies, our results showed the significant association of constructing a GRS for allergies. In contrast, our built risk scores for air pollutants and smoking factors did not have significant effect on allergies. Clearly, there is still evidence gap for exposomic research on modeling allergic conditions.

While our approach integrated well the use of CLS in screening of SNPs and the utility of dominance analysis after risk score construction, it is proposed with some limitations. First, it relies on the calculation of relative contributions via McFadden’s Pseudo R-squared. While this was chosen as an analog of the R-squared in the linear regression context, some may argue of other alternative metrics in application to binary outcomes such as Tjur’s R-squared and Nagelkerke’s R-squared.

Second, splitting the available data set into training and test samples reduce statistical power in this analysis and it requires repeated execution of the fitting process to reduce the randomness. In addition, when working with a binary outcome, this may lead to some draws with highly unbalanced data which may hinder the convergence of the model at worst. Although there is no convergence errors in this analysis, the unbalanced data may explain why very wide confidence intervals were obtained across the bootstrap replicates.

Third, the estimated regression coefficients can be highly inflated with risk scores combining very discriminating variables multiplied further by their weights as in the case for GRS in our application. This can be further aggravated by the unbalanced case-control data. Future directions to mitigate this include possible subgrouping of SNPs in terms of their functional annotations to further decompose how the GRS massively explains allergic outcomes while maintaining interpretability.

Lastly, combining several covariates in weighted RS leads to some loss of information. It is possible and common among environmental variables to have non-linear relationship with the outcome and reducing this into sum-product through the risk score may have diluted their actual relative importance. Hence, constructing an environmental risk score containing non-linear functions of exposures such as splines is left to be explored.

Nonetheless, the dominance analysis approach can easily be adapted to other health outcomes. The proposed approach is flexible and can use continuous measures, such as spirometric outcomes, or other binary outcomes, such as a diabetes diagnosis, among others, even though we used the binary “allergy present/not allergy present” classification in this example.

Ranking the contributions of ERSs along with GRS may aid health risk assessment and aid policy-making by identifying which domains of exposures should be prioritized in setting limit values. For example, in our study, knowing GRS is the most influential on allergies among elderly women can enable targeted prevention and monitoring strategies. Depending on the exposomes with high contributions, public health policies may be developed and specific sources of exposure can be regulated to a particular disease. Aside from smoking regulations, ambient air quality standards can be strengthened and enforced by reducing industrial and combustion near vulnerable communities. Similarly, urban planning and creating more green spaces can be prioritized.

Conclusion

In summary, we observed that genetics had the highest influence to allergic diagnosis while the exposomal factors had lower relative contribution to allergies in this particular cohort data. Methodologically, we successfully applied the concept of dominance analysis based on McFadden’s Pseudo R-squared in the context of exposomal and genetic risk scores. Moreover, it allows us to rank the various domains of cumulative risk factors. In addition, we utilized CLS as a screening strategy for SNPs. Overall, we were able to integrate the application of CLS and dominance analysis with our results serving as their proof of concept. Potentially, this is useful for health risk assessment regulating specific sources of exposure, and priority setting of policy-making in public health. Future directions include applications to longitudinal studies and other methodological improvements to capture possible nonlinear relationships with exposomes.

Normalized weights of variables in ERSs. The violin plot shows the distribution of normalized weights of variables in the ERSs obtained through logistic ridge regression of the training split across the 200 bootstrap replications. 2ndsmoke: Secondhand smoking, exsmoker: Formerly smoking, packyr: cigarette pack-years, smoker: Currently smoking. mth-variable: mean of variable a month prior outcome evaluation, yr-variablename: mean of variable a year prior outcome evaluation.

Relative Contribution of GRS, ERSs, and single predictors to allergic diagnosis. The bar plot shows the median contribution of each variable in the increase of McFadden’s R2 on explaining allergic diagnosis. The error bars indicate the 95% bootstrapped confidence interval based on 200 replications in the test split of the analysis.

Estimated odds ratios (OR) of GRS, ERSs, and single predictors on allergic diagnosis in the Test split across 200 Bootstraps. The forest plot shows the median OR of each variable on explaining allergic diagnosis in the sensitivity analysis. The error bars indicate the 95% bootstrapped confidence interval based on 200 replications in the test split of the analysis. The dotted line represents the null value of OR = 1 (i.e., no association).

Data availability

Codes of the methods used are available at github.com/wincyreyes. However, the cohort data is not publicly accessible due to existing privacy laws, but are available from the corresponding author through tamara.schikowski@iuf-duesseldorf.de on reasonable request.

References

Kay, A. B. Allergy and allergic diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 30–37 (2001).

Brown, S. & Reynolds, N. J. Atopic and non-atopic eczema. Bmj 332, 584–588 (2006).

Nissen, S. P., Kjær, H. F., Høst, A., Nielsen, J. & Halken, S. The natural course of sensitization and allergic diseases from childhood to adulthood. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 24, 549–555 (2013).

Asher, M. I. et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 368, 733–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0 (2006).

Ballardini, N. et al. Development and comorbidity of eczema, asthma and rhinitis to age 12-data from the BAMSE birth cohort. Allergy 67, 217–217 (2012).

Illi, S. et al. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 113, 925–931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2004.01.778 (2004).

Osman, M. et al. Changing trends in sex specific prevalence rates for childhood asthma, eczema, and hay fever. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 42, 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.20545 (2007).

Ridolo, E. et al. Sex in respiratory and skin allergies. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 56, 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-017-8661-0 (2019).

Gutierrez-Brito, J. A. et al. Sex hormones and allergies: exploring the gender differences in immune responses. Front. Allergy. 5, 1483919. https://doi.org/10.3389/falgy.2024.1483919 (2024).

Lee, V. S. et al. Biological sex differences in rhinitis prevalence among adults in the united states: an all of Us research program database analysis. J. Aller Cl. Imm-Pract. 13 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2024.12.032 (2025).

Zein, J. G. & Erzurum, S. C. Asthma is different in women. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 15, 28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-015-0528-y (2015).

Burbank, A. J., Sood, A. K., Kesic, M. J., Peden, D. B. & Hernandez, M. L. Environmental determinants of allergy and asthma in early life. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 140, 1–12 (2017).

Fadadu, R. P., Abuabara, K., Balmes, J. R., Hanifin, J. M. & Wei, M. L. Air pollution and atopic dermatitis, from molecular mechanisms to population-level evidence: a review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20, 2526 (2023).

Park, S. K., Kim, J. S. & Seo, H. M. Exposure to air pollution and incidence of atopic dermatitis in the general population: a National population-based retrospective cohort study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 87, 1321–1327 (2022).

Kathuria, P. & Silverberg, J. Association of pollution and climate with atopic eczema in US children. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 27, 478–485 (2016).

Hui-Beckman, J. W., Goleva, E., Leung, D. Y. M. & Kim, B. E. The impact of temperature on the skin barrier and atopic dermatitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 131, 713–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2023.08.007 (2023).

Schramm, P. J. et al. A systematic review of the effects of temperature and precipitation on pollen concentrations and season timing, and implications for human health. Int. J. Biometeorol. 65, 1615–1628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-021-02128-7 (2021).

Bergmann, K. C. et al. Impact of climate change on allergic diseases in Germany. J. Health Monit. 8, 76–102. https://doi.org/10.25646/11654 (2023).

Kantor, R., Kim, A., Thyssen, J. P. & Silverberg, J. I. Association of atopic dermatitis with smoking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 75, 1119–1125 (2016). e1111.

Saulyte, J., Regueira, C., Montes-Martínez, A., Khudyakov, P. & Takkouche, B. Active or passive exposure to tobacco smoking and allergic rhinitis, allergic dermatitis, and food allergy in adults and children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 11, e1001611 (2014).

Brown, S. J., Elias, M. S. & Bradley, M. Genetics in atopic dermatitis: historical perspective and future prospects. Acta dermato-venereologica. 100, 5768 (2020).

Budu-Aggrey, A. et al. European and multi-ancestry genome-wide association meta-analysis of atopic dermatitis highlights importance of systemic immune regulation. Nat. Commun. 14, 6172. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41180-2 (2023).

Dudbridge, F. Power and predictive accuracy of polygenic risk scores. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003348 (2013).

Wigmann, C., Hüls, A., Krutmann, J. & Schikowski, T. Estimating the relative contribution of environmental and genetic risk factors to different aging traits by combining correlated variables into weighted risk scores. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19, 16746 (2022).

Barouki, R., Audouze, K., Coumoul, X., Demenais, F. & Gauguier, D. Integration of the human exposome with the human genome to advance medicine. Biochimie 152, 155–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2018.06.023 (2018).

Wan, M. et al. Exposomics: a review of methodologies, applications, and future directions in molecular medicine. EMBO Mol. Med. 17, 599–608. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44321-025-00191-w (2025).

Yu, Z. et al. External exposome and incident asthma across the life course in 14 European cohorts: a prospective analysis within the EXPANSE project. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 54, 101314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2025.101314 (2025).

Schikowski, T. et al. Decline in air pollution and change in prevalence in respiratory symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in elderly women. Respir. Res. 11, 113 (2010).

Reed, E. et al. A guide to genome-wide association analysis and post‐analytic interrogation. Stat. Med. 34, 3769–3792 (2015).

Das, S. et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat. Genet. 48, 1284–1287 (2016).

Teschke, S., Ickstadt, K. & Munteanu, A. Detecting interactions in High-Dimensional data using cross leverage scores. Biom. J. 66, e70014 (2024).

Zheng, X. et al. A high-performance computing toolset for relatedness and principal component analysis of SNP data. Bioinformatics 28, 3326–3328 (2012).

Dyer, S. C. et al. Ensembl 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D948–D957. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae1071 (2025).

Flemming, J. & Stern, R. Datenassimilation Auf Der Basis Der Optimalen Interpolation für Die Kartierung Von Immissionsbelastungen: Beschreibung Der Methodik Und Praktische Anwendung für 2002 (Freie Univ., Inst. für Meteorologie, 2004).

Bollmeyer, C. et al. Towards a high-resolution regional reanalysis for the European CORDEX domain. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 141, 1–15 (2015).

Friedman, J. H., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–22 (2010).

Navarrete, C. B. & Soares, F. C. Dominanceanalysis: dominance analysis. CRAN: Contributed Packages (2019).

Menard, S. Coefficients of determination for multiple logistic regression analysis. Am. Stat. 54, 17–24 (2000).

Lima, L. C. et al. Genetic variants in RORA are associated with asthma and allergy markers in an admixed population. Cytokine 113, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2018.07.004 (2019).

Malhotra, N. et al. RORalpha-expressing T regulatory cells restrain allergic skin inflammation. Sci. Immunol. 3 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aao6923 (2018).

Portelli, M. A., Hodge, E. & Sayers, I. Genetic risk factors for the development of allergic disease identified by genome-wide association. Clin. Experimental Allergy. 45, 21–31 (2015).

Tamari, M., Tanaka, S. & Hirota, T. Genome-wide association studies of allergic diseases. Allergology Int. 62, 21–28 (2013).

Lu, C., Norbäck, D., Li, Y. & Deng, Q. Early-life exposure to air pollution and childhood allergic diseases: an update on the link and its implications. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 16, 813–827 (2020).

Murrison, L. B., Brandt, E. B., Myers, J. B. & Hershey, G. K. K. Environmental exposures and mechanisms in allergy and asthma development. J. Clin. Investig. 129, 1504–1515 (2019).

Kilanowski, A. et al. Allergic disease trajectories up to adolescence: characteristics, early-life, and genetic determinants. Allergy 78, 836–850 (2023).

Lee, H. H., Patel, K. R., Singam, V., Rastogi, S. & Silverberg, J. I. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and phenotype of adult-onset atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 80, 1526–1532 (2019). e1527.

Andrianjafimasy, M. et al. PID1 is associated to a respiratory endotype related to occupational exposures to irritants. Free Radic Biol. Med. 172, 503–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.05.038 (2021).

Shao, Y. et al. Gene-Environment interaction between the IL1RN variants and childhood environmental tobacco smoke exposure in asthma risk. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062036 (2020).

Huls, A. et al. Genetic susceptibility to asthma increases the vulnerability to indoor air pollution. Eur. Respir J. 55 https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01831-2019 (2020).

Po, J. et al. Gene-Air pollution interaction and diversity of genetic sampling: the Southern California children’s health study. Genet. Epidemiol. 49, e70000. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.70000 (2025).

MacIntyre, E. A. et al. GSTP1 and TNF gene variants and associations between air pollution and incident childhood asthma: the traffic, asthma and genetics (TAG) study. Environ. Health Perspect. 122, 418–424. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1307459 (2014).

Bouzigon, E. et al. Effect of 17q21 variants and smoking exposure in early-onset asthma. N Engl. J. Med. 359, 1985–1994. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0806604 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank all study members and staff involved in data collection in each cohort and also the funding bodies for SALIA as follows—Study Directorate: R. Dolgner, U. Krämer, U. Ranft, T. Schikowski, and A. Vierkötter; Scientific Team Baseline: A. W. Schlipköter, M. S. Islam, A. Brockhaus, H. Idel, R. Stiller-Winkler, W. Hadnagy, and T. Eikmann; Scientific Team Follow-up: D. Sugiri, (A) Hüls, (B) Pesch, (A) Hartwig, H. Käfferlein, V. Harth, T. Brüning, T. Weiss, and H. Schwender; Study Nurses: G. Seitner-Sorge, V. Jäger, G. Petczelies, I. Podolski, T. Hering, and M. Goseberg; Administrative Team: (B) Schulten and S. Stolz.Over decades, many scientists, study nurses, and laboratories were involved in conducting the study. We are most grateful for all the women from the Ruhr area and Borken who participated in the study and the local health departments for organizing the study.

Funding

This work was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of project R3 in RTG 2624 Biostatistical Methods for High-Dimensional Data in Toxicology, project number 427806116. The IUF is funded by the federal and state governments - the Ministry of Culture and Science of North Rhine-Westphalia (MKW) and the Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMFTR). The SALIA cohort study was supported by the Ministry of the Environment of the state North Rhine-Westphalia (Düsseldorf, Germany), the Federal Ministry of the Environment (Berlin, Germany), the German Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMFTR) as well as by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) [grant numbers HE-4510/2 − 1, KR 1938/3 − 1, LU 691/4 − 1 and SCHI 1358/3 − 1], the German Statutory Accident Insurance (DGUV) [grant number 617.0-FP266], and the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2011) [grant agreement number 211250].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TS, CW, and HS designed and conceptualized the study. PWCR performed the data analysis with guidance from CW and HS. PWCR wrote the manuscript. TS acquired the funding for SALIA study. CW, SK, HS and TS edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reyes, P.W.C., Wigmann, C., Kress, S. et al. Exploring the relative contribution of genetic and external exposomic risk scores to allergies in elderly women. Sci Rep 16, 804 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32501-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32501-0