Abstract

This study was designed to investigate the nonlinear load behavior and fatigue life of distributed small wind turbines in natural turbulent wind fields through an in-situ field experiment. A test platform was deployed in a representative wind resource area in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, using a self-developed 5 kW variable-pitch wind turbine prototype to perform synchronous high-frequency monitoring of wind speed, direction, and blade root loads. The aerodynamic loads were estimated via blade element theory, and rain-flow counting was used to identify the stress cycle history at the blade root, followed by fatigue life prediction using S-N curves and Miner’s linear damage model. A comparative study was conducted on two cases with comparable mean wind speeds but contrasting turbulence intensities. The analysis revealed that increased turbulence intensity significantly amplifies stress fluctuations, raising fatigue damage by 45.7% and reducing blade life by about 31.7%. The results further indicate that adjusting the pitch angle can effectively reduce excessive power output and peak structural loads, confirming the practical control performance of the newly developed pitch actuator. The research offers both measured data and theoretical insights for improving structural reliability and predicting fatigue life of small-scale wind turbines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As global awareness of environmental protection increases and conventional energy resources dwindle, renewable energy generation has become central to future energy security. Owing to its clean and sustainable nature, wind energy has emerged as one of the most significant renewable sources1. Historically, China’s wind energy development has focused on centralized grid-connected generation. As accessible wind-rich regions diminish, distributed wind energy is anticipated to grow rapidly. The China County-Level Green and Low-Carbon Energy Transition Report estimates that China’s technical potential for distributed wind power could reach 250 GW2,3. An analysis of damage reports for wind turbines revealed that blade failures account for approximately 12–19% of reported cases4,5,6. Research on small- and medium-sized wind turbines has predominantly focused on ideal and stable environments. In contrast, distributed deployment scenarios are subject to complex influences from terrain, surface roughness, and atmospheric stability, leading to greater uncertainty and spatial heterogeneity7, Frequent wind direction shifts and intense gusts can result in turbulence far exceeding standard conditions. These complex wind conditions can substantially increase cyclic loading, shorten fatigue life, and elevate structural failure risks, thereby compromising operational reliability and performance. This puts forward certain application requirements for small- and medium-sized wind turbines8,9,10,11. Accordingly, this work investigates the operational behavior of distributed small-scale wind turbines in natural wind fields, emphasizing the mechanisms governing output performance and fatigue response.

In recent years, the structural dynamic characteristics and load response behaviors of wind turbines have become key research focuses, with various experimental techniques widely employed for dynamic identification and structural safety assessment. Chen et al. revealed the coupled dynamic responses between the rotor and nacelle based on strain measurements and frequency-domain analysis12. Yang et al. tested a horizontal-axis wind turbine model in an atmospheric boundary layer wind tunnel and demonstrated that turbulence intensity and yaw angle significantly affect dynamic responses13. Li et al. developed a remote monitoring system integrating optical flow analysis and unmanned aerial vehicles, enabling high-precision dynamic identification of large-scale wind turbines14. Bao et al. conducted load testing on critical components of variable-pitch wind turbines, verifying their structural response capabilities under fluctuating load conditions15. Li et al. proposed a novel strain identification method for dynamic conditions, using high-speed cameras to capture blade motion and inferring strain fields from image-based displacement data16. Numerous studies have demonstrated that turbulence characteristics in real wind fields exert direct and profound influences on the load spectra, fatigue life, and dynamic responses of wind turbines17,18. Elevated turbulence intensity can markedly amplify fatigue loading, induce severe vibrations, accelerate structural degradation, and even trigger catastrophic failures—making it a critical contributor to fracture-related damage in wind turbines19,20. For instance, Pagnini’s field measurements on two 20 kW turbines revealed that wind speed fluctuations substantially disrupted turbine operation, preventing rated power output from being achieved21. Lubitz, through field observations of a 1 kW turbine, found that while turbulence may enhance power output at low wind speeds, it leads to reduced output under near-rated conditions22. In addition, Rafiee and Hashemi-Taheri analyzed failure at the adhesive joint of a composite blade5, while the influence of material properties on aeroelastic behavior23 and the aeroelastic investigation of composite blades24 provide valuable insights into composite blade performance. These studies complement the present work on small variable-pitch blades in natural wind fields.

To systematically evaluate the structural response and fatigue performance of variable-pitch small wind turbines under real wind conditions, this study adopts a three-stage approach encompassing field testing, load measurement, and fatigue analysis. A field measurement platform was first established in a natural wind environment, with site selection, sensor deployment, and multi-condition testing conducted in accordance with IEC standards. High-frequency measurements of wind speed, pitch angle, and blade root loads were then performed to assess the regulatory impact of pitch control on power output and structural loading. Subsequently, rain-flow counting and Miner’s linear damage rule were employed to analyze blade root stress histories and quantify fatigue damage and life variation under representative turbulent conditions. By integrating measured wind speed and load data with aerodynamic theory and fatigue modeling, the study demonstrates the feasibility of the novel pitch control mechanism in enhancing operational stability and extending structural lifespan, thereby providing both experimental evidence and theoretical guidance for the structural optimization and fatigue design of distributed small wind turbines.

Methodology

Blade element theory

Blade element theory is a fundamental approach in aerodynamic analysis of wind turbines, in which the blade is discretized along the spanwise direction. Typically, the rotor blade is divided into infinitesimal differential segments, commonly into ten spanwise elements in practical applications22,25, collectively referred to as blade elements. By numerically integrating the aerodynamic forces on each blade element over the span, the overall aerodynamic characteristics of the entire blade can be reconstructed. In applying blade element theory, the wind turbine is typically modeled with N, blades, a rotor radius of R, blade element chord length c, pitch angle β, rotational speed Ω, and incoming free-stream velocity v1. When accounting for tangential induction effects, the blade’s rotational motion yields a tangential velocity of Ω, while the induced velocity in the wake region is modified by the tangential induction factor a’, resulting in an induced velocity of a’Ω r. According to the principle of momentum conservation, the effective tangential flow velocity experienced by a blade element is given by: (1-a’) Ω r.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the relative inflow velocity W at the blade element is composed of both axial and tangential components, and is mathematically expressed as:

The inflow angle φ is defined as the geometric angle between the relative velocity vector W and the rotor plane, with the following trigonometric relationship:

The angle of attack α is defined as the angle between the relative velocity W and the airfoil chord line, expressed as:

Based on the aerodynamic angles defined above, the aerodynamic forces acting on an infinitesimal blade element of spanwise length dr can be decomposed as follows:

The following expressions (7) and (8) represent the force components projected onto the directions normal and tangential to the rotor plane, respectively:

The nondimensionalized form is given by:

For a rotor with N blades, the thrust and torque generated over a blade element of spanwise thickness dr can be expressed as:

In this study the classical blade element theory (BEM) was employed owing to its simplicity, low computational cost and easy coupling with fatigue analysis. Compared with advanced aerodynamic models such as CFD or hybrid BEM–CFD approaches, the classical BEM model does not fully capture three-dimensional flow, unsteady aerodynamic effects or dynamic stall. However, for small-scale turbines under the present test conditions it provides sufficiently accurate estimates of aerodynamic forces while maintaining computational efficiency.

Rain-flow counting method

In structural fatigue life prediction and accelerated test design, accurately capturing the stress spectrum representative of actual service conditions forms the essential foundation. To enhance the efficiency of fatigue analysis and simplify experimental data processing, statistical techniques such as the rain-flow counting method are commonly employed to convert random load time histories into standardized stress cycle sequences. Fundamentally, the method involves a systematic counting process to extract key parameters-stress amplitude and the corresponding number of cycles-from dynamic loading histories, thereby providing input data for fatigue damage calculations. Counting methods can be categorized as single- or two-parameter approaches based on their dimensional characteristics; the latter, exemplified by the rain-flow method, is widely adopted in engineering practice due to its superior capability in capturing the complexity of loading signals26,27,28.

The rain-flow counting method was first proposed by M. Matsuishi and T. Endo in the 1950s. Based on the principle of fatigue damage equivalence, it simplifies complex, irregular loading sequences into a series of equivalent cycles by simultaneously considering stress amplitudes and mean values. In practice, all extrema-peaks and valleys-are extracted from the load-time history to form an ordered sequence, which is then subjected to a rule-based process to identify and pair cycles, resulting in a set of closed stress cycles. Residual stress fluctuations that do not form complete cycles are generally considered to have negligible impact on fatigue and are therefore omitted. The final output, consisting of stress amplitude-cycle count pairs, serves as input for subsequent fatigue life evaluations, such as those using Miner’s linear cumulative damage model. A schematic illustration of the rain-flow counting method is shown in Fig. 2.

The implementation of the rain-flow counting method follows a systematic set of rules and procedures. Its core concept mimics the path of a raindrop “flowing” along the stress-time curve to identify complete stress cycles. Specifically, each counting process begins at a local peak in the stress-time history and proceeds “downstream” along the inward-facing slope. During this flow, if a subsequent peak is higher than the initial peak, indicating that the flow path cannot close, the counting is terminated for that trajectory. Similarly, if the current path intersects with a previously completed “rain-flow” trajectory, the counting is also terminated to preserve cycle integrity. This procedure allows for the effective extraction of all closed-cycle stress intervals and records the stress amplitude for each identified cycle. Any residual, non-closed stress sequences-exhibiting diverging or converging characteristics-are subjected to a second-pass counting stage to recover potentially missed cycles. Ultimately, a combined analysis of both counting stages yields the total number of valid stress cycles present in the complete stress-time history, providing the structural load spectrum required for fatigue life analysis.

Fatigue damage theory

Fatigue life analysis refers to the evaluation of cumulative damage in structural materials under cyclic loading and the prediction of potential failure risks29,30. It represents a critical component in the structural design of wind turbines. Taking wind turbine blades as an example, preventing fatigue failure over their service lifetime requires close attention to the flapwise bending moments at the blade root, which is generally recognized as the most fatigue-sensitive region31. Under alternating loads, repeated stress cycles induce localized microstructural damage, which accumulates over time and leads to macroscopic fatigue failure once a critical threshold is reached. Fatigue damage theory provides a foundational framework for establishing the relationship among loading, damage accumulation, and structural lifespan.

Miner’s rule for linear fatigue damage accumulation

Among various fatigue accumulation models, Miner’s linear damage rule is widely adopted due to its simplicity and engineering applicability. The model assumes that at a given stress level, each stress cycle contributes a fixed amount of fatigue damage, and that damages from different stress levels are independent and linearly cumulative. Fatigue failure is considered to occur when the total accumulated damage reaches a critical value, typically taken as 1. The fatigue damage accumulated under cyclic loading is expressed as :

where: D——denotes the cumulative fatigue damage under cyclic loading, with a value ranging from 0 to 1;

\({n_i}\)——is the number of applied load cycles at a given stress level;

\({N_i}\)——is the number of cycles required to cause material failure at \({\sigma _i}\) .

S-N curve for material fatigue performance

The S-N curve (Wöhler curve) characterizes the number of load cycles N that a material can withstand under a given stress amplitude S, and serves as one of the fundamental tools in fatigue design. By mapping experimentally measured or numerically simulated structural loads onto the corresponding S-N curve, the fatigue life and damage level of a structure can be quantitatively predicted. In engineering practice, the S-N relationship is commonly fitted using a power-law form, as expressed by the following equation:

Where:C——is the fatigue coefficient, dependent on the test load conditions;

m——is the fatigue exponent, typically related to the stress ratio;

σ——is the applied stress amplitude, expressed in MPa;

N——is the number of load cycles to failure (fatigue life).

According to the fatigue design requirements in the GL 2010 guidelines, the failure cycle count for wind turbine design life must exceed 107,107, categorizing the failure mode as high-cycle fatigue. Since S-N curves are typically derived under fully reversed (symmetric) cyclic loading, a correction must be applied when the actual stress state is non-symmetric. The Goodman relation is commonly employed for this purpose, as given by the following Eq. (15) :

Where,\({\sigma _a}\)——is the stress amplitude under non-symmetric loading;

\({\sigma _m}\)——is the mean stress;

\({\sigma _b}\)——is the ultimate tensile strength of the material;

\({\sigma _{a( - 1)}}\)——is the equivalent stress amplitude under fully reversed (symmetric) loading.

Experimental setup

This chapter presents a field-testing approach aimed at investigating the structural dynamic response of a variable-pitch wind turbine subjected to nonlinear aerodynamic loading under naturally turbulent wind conditions. Prior to testing, relevant standards were referenced to standardize the experimental procedure and load measurement methodology. Although standards such as IEC 61400-2 (Design Requirements for Small Wind Turbines) are primarily intended for turbine design and certification, the present study focuses on analyzing dynamic responses under turbulent wind conditions rather than validating turbines for commercial production. Consequently, the application of these standards is adapted to suit the research objectives. According to IEC 61400-2, the reference wind speed for Class III small wind turbines is 10.5 m/s32. Therefore, the experimental campaign emphasized measurements near this design operating condition. The standard recommends that measured data span the range from the cut-in wind speed Vin=2.5 m/s to twice the average wind speed 2Vave = 15 m/s, with a minimum of 30 one-minute averaged datasets collected within each wind speed interval (i.e., sampling frequency ≥ 0.5 Hz). Due to limitations in test duration and external wind resource availability, such as frequent low-wind conditions at the site, the full standard requirements could not be strictly satisfied. Nevertheless, efforts were made to span the entire operational wind speed range of the turbine. It should be noted that long-term durability tests specified in the standard, such as assessments of structural integrity, material degradation, and long-term dynamic operation, are beyond the scope of this study. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the experimental data, all stages of the study, from site selection and equipment calibration to data acquisition and post-processing, were meticulously planned and conducted in accordance with standardized procedures.

Test site

As this study was conducted under natural wind field conditions, the field test offers greater fidelity to real-world operations compared to controlled wind tunnel experiments. It enables the capture of aerodynamic performance and dynamic responses of the turbine under complex, unsteady wind inflows. To ensure safety and logistical feasibility, the experiment was carried out at a renewable energy testing base in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia. Figure 3 shows the location of the wind field and the experimental wind turbine. Site selection was based on evaluations of wind speed variability, directional consistency, and regional meteorological data33. The site satisfies key criteria including a representative wind speed distribution, favorable wind direction conditions, and environmental compatibility with the installation context of the tested turbine. The wind speed in the test area fluctuated within the range of 0 to 12 m/s, making it suitable for evaluating the turbine’s load characteristics under realistic operating conditions.

Experimental apparatus

The prototype turbine used in this experiment was assembled based on a modified version of the WM-5 horizontal-axis wind turbine, originally manufactured by Hefei Weimin Power Co. Ltd. The generator is a 5 kW permanent magnet synchronous generator developed by Baotou Tianlong Permanent Magnet Motor Co. Ltd. Its hollowed main shaft is integrated with a newly designed variable-pitch regulation mechanism, a transmission system, the base frame, and the tower—all of which were independently developed for this study. Detailed specifications of the main components are listed below:

Blades

The wind turbine blades adopt a NACA 4412 airfoil profile, with corresponding cross-sectional data summarized in Table 1. To ensure sufficient strength and reliability during operation, the blades are fabricated using pine wood and polyester fiber composites. Based on the fatigue failure stress analysis method specified in Sect. 7.9.2 of GB/T 17,646 − 2013 (Small Wind Turbine Generating Systems), the blade’s estimated fatigue cycle limit is 5.9 × 1010. Assuming a 20-year operational lifespan with 3000 annual operating hours, the estimated cumulative fatigue cycles total 7.92 × 108. Therefore, the blade design satisfies the fatigue performance requirements for the intended testing conditions34.

Generator

The generator is a 5 kW low-speed permanent magnet synchronous generator developed by Baotou Tianlong Permanent Magnet Motor Co., Ltd. The generator shaft is custom-designed with a hollow structure, allowing the actuator rod to pass through and connect directly to the blades for pitch angle adjustment. The key performance parameters of the generator are summarized in Table 2.

Pitch regulation mechanism

A novel, low-cost, structurally simple, and reliable power control method for small wind turbines was proposed by the research team. It employs a unified pitch regulation mechanism that utilizes a rack-and-pinion transmission system to achieve synchronized pitch adjustment across all three blades. The wind turbine system consists primarily of a pitch regulation mechanism and a driving unit. Figure 4 shows a schematic of the overall pitch-regulated wind turbine system, which includes the pitch actuator, driving mechanism, generator, and transmission rod.

The generator is equipped with a hollow main shaft, within which the pitch regulation mechanism is integrated. This mechanism comprises a rack synchronization disk, a pitch bearing, and a rack-and-pinion transmission system. A worm-gear reducer combined with a thrust bearing forms the core of the adjustment unit. During testing, pitch angle control is achieved via a hydraulic actuator, whose stroke is regulated by adjusting the hydraulic oil flow rate and pressure. In the power regulation phase, the drive system pushes the transmission rod axially through the generator’s hollow shaft. The actuator must output a thrust force F that counterbalances the aerodynamic torque T exerted by the blades. Figure 5 shows a schematic diagram of the regulating drive structure in a variable-pitch wind turbine. The transmission rod is mechanically linked to a synchronization disk, which imparts axial motion to the rack assembly and induces rotation of the meshed gear. The gear is rigidly connected to the pitch bearing, enabling coordinated rotation of both the bearing and the blade to achieve pitch angle adjustment. During steady-state operation, the regulation mechanism remains in standby mode, maintaining dynamic equilibrium between the actuator thrust F and blade torque T, thereby ensuring pitch stability across the turbine’s entire operating envelope.

Figure 6 illustrates the mechanical schematic of the pitch adjustment process. When the drive system is activated, the transmission rod moves axially along the hollow shaft. Through its mechanical linkage with the rack synchronization disk, this motion causes axial displacement of the rack, which in turn drives the gear to rotate. The blade connector then transmits this motion, rotating the blade and completing the pitch angle adjustment.

Tower

The tower has a total height of 10 m and is designed as a hollow prismatic structure. The inner diameter at the top of the tower is 116 mm, while the diameter at the base expands to 380 mm. The main body of the tower is fabricated from Q345 high-strength low-alloy structural steel. To ensure structural integrity, upper and lower flanges are joined using a welded assembly of shaped steel plates. The flange components are made from Q235 carbon structural steel.

Basic specifications of the experimental prototype

The basic design specifications of the wind turbine prototype are presented in Table 3.

Figure 7 shows the experimental wind turbine prototype, providing a visual overview of its structural configuration and design details. The labeled components are as follows: A, blade; B, nacelle fairing; C, generator; D, tower; E, anemometer and wind vane; F, nacelle; G, tail fin; H, base-mounted transition flange.

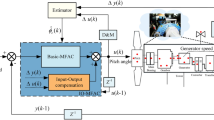

Wind turbine control system

Figure 8 shows the user interface of the integrated control and monitoring system for the wind turbine. The system aggregates data from various sensors, records them in real time, and transmits the information to the central controller. Key parameters such as wind speed, wind direction, pitch angle and blade position, output power, and rotor speed are simultaneously displayed and logged. This ensures the completeness and integrity of the experimental dataset. Additionally, the control software allows for precise regulation of the turbine’s pitch angle.

Figure 9 illustrates the calibration process in which the blade position signal from the control system is aligned with the actual pitch angle measured using a WD digital inclinometer and a spirit level. By comparing the pitch position signal from the control system with real-time pitch angle measurements obtained from the inclinometer, a conversion relationship between the two was established. This calibration ensures that when a specific pitch command is issued by the control system, the actual blade pitch angle corresponds precisely to the intended value. As a result, closed-loop control and accurate adjustment of the pitch regulation process are achieved. The specific calibration relationship is given as follows:

Where, y ——is the pitch position signal from the control system, %;

x ——is the measured blade pitch angle, °.

Equipment calibration and test preparation

In field testing of wind turbines, equipment calibration is of critical importance, as variations in wind speed and direction can directly affect the accuracy of measured data. Therefore, to ensure data reliability, all measurement instruments must be rigorously calibrated prior to the start of the experiment. This ensures that the equipment remains stable and responsive under real-world conditions where wind speeds fluctuate significantly. The key calibrated instruments include:

Anemometer and wind direction sensor

An anemometer (model: Thies Clima 4.4000.00) was mounted at the top of the wind turbine tower. It is designed to operate within a wind speed range of 0–45 m/s and provides high-precision wind speed data even under highly variable wind conditions. A wind direction sensor (model: R. M. Young 5103 Wind Monitor) was also installed at the tower top to capture wind direction changes with high accuracy. Both wind speed and direction were sampled at a frequency of 1 Hz. The combined measurements provide a comprehensive representation of site-specific meteorological conditions, thereby informing turbine operation and performance optimization.

Load measurement system

One of the core objectives of this field test was to measure the loads acting on key components of the wind turbine. According to the mechanical load measurement standard IEC 61400-13, the blade root is identified as the most heavily loaded region, making load monitoring at this location particularly critical. Given the design characteristics of the variable-pitch regulation system in this turbine, the experiment focused on capturing dynamic loads at the blade root in both edgewise and flapwise directions. This approach enables a comprehensive assessment of the loading conditions experienced at the blade root. As the blade root adopts a dual-plate clamping structure, the measurement points were installed on the outer surfaces of the clamping plates. During testing, the rotor was in continuous motion; therefore, the load data from the blade root sensors were wirelessly transmitted to the data acquisition unit via a Bluetooth module (model: CAN blue II). The specific sensor placement is illustrated in Fig. 10.

The resistance strain gauges were supplied by AVIC Electromechanical Measurement Instrument Co., Ltd. Each gauge has a nominal resistance of 350.4 ± 0.3 Ω and a gauge factor of 2.07 ± 1%. These high-sensitivity gauges enable accurate load measurements at the blade root of the wind turbine.

The load testing apparatus is shown in Fig. 11 and the measurement system consists of a main control cabinet and a signal acquisition cabinet. The main control cabinet houses a PC workstation, an IMC BusDAQ data acquisition module, and an IMC SC15 analog signal module, which together handle core data processing tasks. All sensor signals are processed through a high-performance data acquisition system. The central control unit (model: IMC BusDAQ) integrates signal acquisition, transmission, storage, and processing functionalities. During testing, the sampling frequency was set at 20 Hz. The IMC BusDAQ module operated in conjunction with multiple signal acquisition units to receive real-time load data from all measurement points. The collected data were transmitted to the central PC for further analysis.

After data acquisition, all raw signals were post-processed using a dedicated signal processing system. As multiple types of sensors were employed in the experiment, the data underwent calibration, noise reduction, and signal filtering proceduresto ensure the accuracy and validity of the measurements.

Wind turbine test results and analysis

Analysis of wind turbine power output

Based on a large dataset obtained under various pitch angles and wind speeds (averaged across multiple measurements), the power output-wind speed curves for different pitch angles were derived, as shown in Fig. 12. It is evident from the figure that the turbine achieves optimal generator output performance across the full wind speed range when the pitch angle is set to 6°. Deviations from this optimal pitch-whether increased or decreased—lead to noticeable reductions in output power. A detailed analysis of the wind speed-power output relationship under different pitch settings reveals that when the pitch angle is fixed at 0°, 6°, or 12°, the output power increases rapidly with wind speed, exhibiting a strong positive correlation. This behavior highlights a critical safety concern for conventional fixed-pitch small wind turbines operating under high wind speeds, primarily due to the inability to limit power output effectively, thereby posing risks to structural integrity and operational stability. Furthermore, Fig. 12 shows that at a given wind speed, increasing or decreasing the pitch angle from the optimal value results in power output degradation, with larger reductions observed at higher wind speeds. These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of the novel pitch regulation mechanism in moderating power output under high wind speed conditions.

To investigate the abnormal decline in power output observed under the 0° pitch angle condition, it is essential to understand the two primary pitch control strategies in wind turbines-namely, positive and negative pitch regulation. Positive pitch control refers to blade rotation in the direction that reduces the angle of attack. Conversely, negative pitch control involves blade rotation that increases the angle of attack. Specifically, the positive pitch control strategy actively reduces the blade’s angle of attack to lower aerodynamic lift, thereby enabling a gradual and controlled reduction in power output. In this process, the power output decreases smoothly as the pitch angle increases. In contrast, the negative pitch strategy induces active stall by increasing the angle of attack, resulting in a sharp drop in power output with only small changes in pitch angle35.

As illustrated by the power output measurements under varying pitch angles in Fig. 12, a steady decline in power output is observed when the pitch angle increases from 6° to 12°, which is consistent with the expected behavior of forward pitch regulation. In contrast, when the pitch angle is adjusted in the reverse direction from 6° to 0°, a sharp drop in power output occurs when the wind speed exceeds 11 m/s, aligning well with the stall-inducing characteristics typical of reverse pitch control.

Given that the wind turbine consistently achieved its maximum power output under a 6° pitch angle across a range of inflow wind speeds, further analysis was conducted to evaluate the output characteristics under this condition. By adjusting the external load, the generator output voltage was regulated at 380 V (its rated voltage), and the corresponding power output data were recorded. A scatter plot illustrating the relationship between power output and wind speed at the 6° pitch angle is presented in Fig. 13. In theory, the turbine’s power output should exhibit a positive correlation with wind speed. However, due to practical factors such as pitch control response delay and wind speed instability, significant deviations and power attenuation were observed. The results also demonstrate that the turbine’s measured power output generally followed the expected rated power curve during field operation. While some wind speeds exceeded the turbine’s rated value, the corresponding power output remained slightly below the rated level. Conversely, even at wind speeds below the turbine’s designated cut-in threshold, a measurable level of power output was still detected.

Figure 14 illustrates the frequency distributions of wind speed and output power. Under operating conditions where power is generated, the wind speed is predominantly distributed within the range of 4 m/s to 10 m/s, following a Rayleigh distribution. However, the corresponding power output fails to reach the rated design values. Experimental results indicate that the majority of the power output is concentrated in the range of 1 kW to 2 kW.

This phenomenon can be attributed to several contributing factors. Firstly, the inherent variability in wind speed and direction within the test field prevents the turbine from operating under steady-state design conditions for extended periods, making it difficult for the rotor to maintain the optimal tip-speed ratio. Secondly, yaw misalignment introduces deviations in the inflow angle from its optimal design orientation, thereby impairing aerodynamic performance and reducing power output. Thirdly, limitations in controller performance may prevent timely and accurate adjustments to blade pitch or other critical operational parameters, further diminishing power conversion efficiency. In addition, the observation of measurable power output under wind speeds below the theoretical cut-in threshold is likely due to the rotor’s inertia, which allows the turbine to temporarily sustain operation during short-term drops in wind speed.

Root bending moment analysis

The root bending moment is one of the primary loads experienced by wind turbine blades, and its variation directly affects both the blade’s fatigue life and structural integrity. In this field test, we investigated the load characteristics of the distributed pitch-regulated wind turbine under normal operating conditions by recording both the in-plane (flapwise) and out-of-plane (edgewise) root bending moments at various pitch angles. The flapwise bending moment refers to the bending moment acting out of the rotor plane, primarily driven by aerodynamic forces perpendicular to the plane of rotation, such as wind pressure, turbulence, and wind shear. The edgewise bending moment acts within the plane of rotation and is mainly induced by centrifugal forces, gravitational cyclic loads, and aerodynamic drag, such as chordwise forces on the blade.

The scatter plots of root edgewise bending moment (Mx) and flapwise bending moment (My) under 0°, 6°, and 12° pitch angles are presented for inflow wind speeds ranging from 2 to 16 m/s. It can be observed that the root bending moment is predominantly in the flapwise direction, while the edgewise bending moment remains relatively small. Figure 15a,c,e show the flapwise root bending moment under varying pitch angles and wind speeds. The scatter plots reveal that flapwise bending moments exhibit a trend of linear aggregation across different wind speeds. The presence of negative values indicates that the blade vibration occurred in the opposite direction to the selected analysis axis; the sign merely reflects the vibration direction. At lower wind speeds (2–4 m/s), the bending moment values are more scattered, indicating that during initial blade rotation, the flapwise bending moment is highly sensitive to wind variations. At moderate wind speeds (5–11 m/s), both the maximum values and the dispersion of flapwise root bending moment increase with wind speed, suggesting stronger aerodynamic influence at higher speeds. When the wind speed exceeds the rated value of 11 m/s, the overall flapwise root bending moment continues to rise, accompanied by pronounced dispersion.

Figure 15b,d,f depict the scatter plots of the root edgewise bending moment under various pitch angles and wind speeds. The data points show a clear linear aggregation pattern, with the magnitude of edgewise bending moment increasing as wind speed rises. The occurrence of both positive and negative values arises from the alternating edgewise bending directions as the blade rotates from its highest point (above the hub) to the lowest point (below the hub), and vice versa. At low wind speeds (2–4 m/s), the data points of edgewise bending moment are less dispersed. This is attributed to the initial rotation stage of the rotor, where the rotational speed is low and the blades are more sensitive to wind load variations. In this regime, the dominant contributor to the edgewise moment is blade gravity. In the moderate-to-high wind speed range (5–11 m/s), both the magnitude and dispersion of the edgewise root bending moment increase with wind speed. This trend is primarily driven by the increasing rotor speed, which enhances the combined effects of centrifugal and gravitational forces acting on the blade. When the wind speed exceeds the rated value (11 m/s), the data points exhibit pronounced dispersion. This is mainly due to the uncontrolled increase in rotor speed under a fixed pitch angle, which amplifies the centrifugal loads and intensifies the gravitational load fluctuations experienced by the rotating blades.

Power spectral analysis of blade root loads

To further investigate the characteristics of the measured data, a comparative power spectral analysis was conducted for the flapwise and edgewise loads at the blade root under varying pitch angles, as illustrated in Fig. 16. All three curves exhibit high power spectral density (PSD) in the low-frequency range (0.1–1 Hz), with the PSD gradually decreasing as frequency increases. This indicates that the signal energy is primarily concentrated in the low-frequency region, while the energy contribution diminishes in higher frequency bands. As the pitch angle increases from 0° to 12°, the PSD in the 0.1–1 Hz band is significantly higher under the 0° condition compared to 6°and 12°. In the high-frequency range (1–10 Hz), substantial differences in PSD are observed among the three curves. The 0°pitch condition demonstrates relatively higher PSD in the high-frequency region, while the 12° condition shows the lowest PSD. These results suggest that the PSD of blade loading decreases with increasing pitch angle across both low- and high-frequency ranges, which is likely influenced by changes in system stiffness, damping, or the frequency characteristics of external excitation.

The PSD plots in Fig. 16a,b reveal distinct frequency peaks in both flapwise and edgewise bending moments, primarily associated with rotor rotational frequencies and the natural frequencies of key wind turbine components. For a three-bladed wind turbine, the dominant excitation frequencies are typically the 1P and 3P harmonics of rotor speed. When the excitation frequency coincides with a structural natural frequency, resonance may occur, potentially causing damage and reducing the turbine’s operational lifespan27. The first-order flapwise and edgewise frequencies are identified at approximately 0.216 Hz and 0.281 Hz, respectively, while the second-order frequencies occur near 1.135 Hz (flapwise) and 1.22 Hz (edgewise), each exhibiting notable peaks. The magnitudes of these peaks diminish with increasing pitch angle, attributable to reduced excitation energy, although the natural frequencies themselves remain unchanged. Furthermore, the presence of a 2P peak in the blade’s power spectrum indicates aerodynamic or mass imbalance in the rotor system.

Fatigue life analysis of wind turbine blades

A time-domain fatigue analysis method was employed to evaluate the fatigue life of blades from a distributed wind turbine operating under natural wind conditions. The measured blade root bending moment time histories were converted into corresponding stress histories. Rain-flow counting was used to identify stress cycles, extracting stress amplitudes and their associated cycle counts to quantify fatigue damage. Data processing and damage assessment were implemented using MATLAB scripts, with a focus on investigating the impact of turbulence intensity on blade fatigue performance.

Two representative 10-minute data segments from field measurements were selected for comparative analysis. Both samples had similar mean wind speeds near the turbine’s rated value, but exhibited significantly different turbulence intensities. The first sample had a mean wind speed of 10.23 m/s and a turbulence intensity of 9.6%, while the second had a mean wind speed of 10.36 m/s with a turbulence intensity of 18. 8%. Bending moment signals were batch-processed and converted to equivalent stress histories, followed by rain-flow cycle counting to obtain the stress amplitude distributions. Based on Miner’s linear fatigue damage rule and incorporating the S-N curve of the blade material along with Goodman mean stress correction, the short-term fatigue damage was extrapolated to estimate full-life fatigue performance. The detailed analytical procedure is illustrated in Fig. 17.

Processing of stress time series data

To determine the equivalent applied stress \({\sigma _{eqB}}\) required for fatigue analysis, the procedure follows the specifications outlined in GB/T 17,646 − 2017 Small Wind Turbine Systems and assumes the blade behaves as a cantilever beam. Under this assumption, the maximum fatigue load occurs at the blade root, where the bending moment reaches its peak. The total bending moment at the root can be expressed as:

The axial and bending components are provided by Eqs. (20) and (21), respectively:

where, \({A_B}\)——A denotes the cross-sectional area at the blade root, m²;

\({W_{xB}}={I_{xx}}/\bar {x}\)——is the section modulus in the flapwise direction, m³.

\({W_{yB}}={I_{yy}}/\bar {y}\)——is the section modulus in the edgewise direction, m2.

The cross-sectional dimensions at the blade root are 250 mm in width and 40 mm in height, as illustrated in Fig. 18.

The calculated cross-sectional properties of the blade root are as follows: the moment of inertia about the y-axis is Ixx=5.208 × 10− 5 m4, the moment of inertia about the x-axis is Iyy=1.33 × 10− 6 m4, and the cross-sectional area is A = 0.01 m2. Compared with the bending in the flapwise direction, the moment of inertia in the edgewise direction is approximately 40 times stronger, and the flapwise bending moment is the dominant load component relative to axial centrifugal loads and edgewise vibrations. In the design of small-scale wind turbine blades with relatively high stiffness, these two minor loads are typically neglected. According to standardized load evaluation, both edgewise and centrifugal stresses should remain below 5% of the maximum flapwise fatigue stress. Therefore, the equivalent stress at the blade root can be simplified as being solely induced by flapwise loads and the corresponding sectional stiffness.

The measured time-history data of blade root bending moments were converted into the corresponding stress time-history curves. The results are illustrated in Fig. 19, from which it is evident that the sample with low turbulence intensity exhibits relatively small stress fluctuations, with the time-history curve showing smooth periodic variations and minor differences between peak and valley values. In contrast, the sample with high turbulence intensity demonstrates significantly enhanced stress fluctuations, characterized by increased high-frequency oscillations and intermittent spikes in the time-history curve. The elevated turbulence intensity induces more rapid variations in instantaneous wind speed, which exacerbates the structural dynamic response and potentially increases the risk of fatigue damage.

Load cycle calculation

In this study, the stress time-history data were processed using the rain-flow counting method implemented via MATLAB programming. The amplitude of load cycles, a critical factor in fatigue damage, plays a decisive role in both fatigue life prediction and the accuracy of experimental results. This analytical approach enables dimensionality reduction of the load spectrum data, thereby providing a solid data foundation for subsequent fatigue damage assessment. The stress–life (S–N) theory, originating from Wöhler’s curve system and the endurance limit principle, serves as the core analytical method for infinite life design. This theory defines a quantitative relationship between stress amplitude and the number of cycles to failure under constant-amplitude, symmetric cyclic loading, based on standardized specimen tests. Based on this theoretical model, fatigue life of structural components can be quantitatively assessed by integrating the measured stress amplitude distribution with the characteristics of the corresponding S-N curve.

Figure 20 presents the amplitude-frequency histogram of load cycles derived from the rain-flow counting process, with Fig. 20a illustrating the results under low-turbulence conditions. It is observed that the majority of mid-frequency load cycles are concentrated in the amplitude range of 10 MPa to 20 MPa. As the stress amplitude increases to 20 MPa-40 MPa, the cycle frequency drops significantly, with the maximum amplitude reaching 42.2 MPa. Under high turbulence conditions, the load cycles are primarily concentrated between 20 MPa and 40 MPa, with extreme stress amplitudes exceeding 100 MPa. Although such high-stress events are infrequent, the fatigue damage caused by low-amplitude stress cycles is negligible, whereas significant fatigue damage is predominantly induced by high-amplitude load cycles.

Fatigue life calculation of the blade

The blades of the distributed variable-pitch wind turbine used in the experiment were constructed from pine wood, and the corresponding material coefficients are listed in Table 4.

Based on the research findings of Peterson and Clausen from Newcastle University, the present study adopts an empirical formula for estimating the fatigue life (number of cycles to failure) of pine wood, as expressed in the following equation:

Based on the empirical equation, the corresponding S-N curve for pine wood is plotted as shown in Fig. 21.

According to Miner’s linear cumulative damage theory, “damage” is defined as a parameter, where an undamaged material has a damage value of 0, and fatigue failure is considered to occur when this value reaches 1. Although damage is not a physical quantity, it has been widely used as an effective metric for fatigue life prediction. Based on the stress amplitude frequency distribution obtained from the rain-flow counting method, the material’s S-N curve, and Miner’s linear cumulative damage rule, the fatigue life of the wind turbine blade is estimated using the stress-life (S-N) approach.

The cumulative damage values under two different turbulence intensity conditions were calculated: D = 5.0749 × 10− 7 for the first case and D = 7.3887 × 10− 7 for the second. Based on the total damage (D) accumulated over a 10-minute wind speed interval, the estimated fatigue life of the blade root was approximately 37.49 years for the first condition and 25.7 years for the second. The damage rate in the second case was 45.7% higher than in the first, leading to a fatigue life reduction of approximately 31.7%.These results clearly demonstrate the significant impact of turbulence intensity on the fatigue life of wind turbine blades.

Conclusion

This work carried out a field-based investigation of a prototype 5 kW variable-pitch wind turbine, with the aim of clarifying both its aerodynamic performance and structural fatigue behavior under natural turbulent wind conditions. The study combined in-situ measurements, aerodynamic modelling, and fatigue analysis, leading to several key outcomes:

-

(1)

The prototype turbine generated power primarily within the 4–10 m/s wind speed range, with output concentrated between 1 and 2 kW. The deviation from rated capacity was attributed to turbulence, yaw misalignment, and non-ideal inflow conditions, which limited the rotor’s ability to maintain its optimal tip-speed ratio. A comparison between BEM-based predictions and field measurements showed reasonable agreement, supporting the adequacy of the aerodynamic model for small-scale applications.

-

(2)

Blade root loads were characterized in both flapwise and edgewise directions. Results indicated that flapwise bending dominated the fatigue-relevant loading, and both components increased with wind speed. Adjusting the pitch angle significantly reduced the magnitude and dispersion of these loads, confirming the role of pitch control in alleviating dynamic stresses under turbulent inflows.

-

(3)

Power spectral density analysis revealed distinct peaks corresponding to rotor rotational harmonics (1P and 3P) and the natural frequencies of the blade. The load energy was concentrated in the low-frequency range, with the 0° pitch case showing consistently higher spectral densities. These observations suggest that inappropriate pitch settings can exacerbate resonance risks and should be avoided in practice.

-

(4)

Blade root loads were processed using rain-flow counting to obtain stress cycle distributions. Fatigue damage was then evaluated using S–N curves and Miner’s linear rule as a first-order approximation, focusing on the effect of turbulence intensity on fatigue life. Special attention was given to the sensitivity of the flapwise bending moment, which dominates fatigue behavior. The results highlight how variations in turbulence intensity directly influence stress fluctuations, cumulative damage, and blade longevity.

The present conclusions are derived from short-term field measurements at a single inland site using pine–polyester composite blades. Environmental conditions such as seasonal temperature changes and dust accumulation may have influenced the measurements, while the limited duration of monitoring restricted the range of operating conditions captured. Further long-term testing, expanded wind speed and pitch ranges, and validation through FEM simulations are required to enhance the robustness of the results. Future studies will also address progressive fatigue modelling of composite materials and explore multi-physical couplings—including thermo-structural and fluid-structure interactions—to provide a more comprehensive framework for fatigue life prediction and control strategy development.

Data availability

The authors ensure the authenticity and validity of the materials and data in the article. Requests for data access should be directed to Dr. Jun Zhang at 20231800274@imut.edu.cn.

References

Kebede, A. A., Kalogiannis, T., Van Mierlo, J. & Berecibar, M. A comprehensive review of stationary energy storage devices for large scale renewable energy sources grid integration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 159 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112213 (2022).

Zhang, D., Feng, K., Shi, Z. & Yu, Q. Current states and recommendations for grid integration of new energy in China. Sol. Energy 89–97. https://doi.org/10.19911/j.1003-0417.tyn20240605.03 (2024).

Zhou, L. et al. Intelligent optimization distributed wind power distribution system model based on mixed integer linear programming. Autom. Instrum. 93–98. https://doi.org/10.14016/j.cnki.1001-9227.2024.01.093 (2024).

Chou, J. S., Chiu, C. K., Huang, I. K. & Chi, K. N. Failure analysis of wind turbine blade under critical wind loads. Eng. Fail. Anal. 27, 99–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2012.08.002 (2013).

Rafiee, R. & Hashemi-Taheri, M. R. Failure analysis of a composite wind turbine blade at the adhesive joint of the trailing edge. Eng. Fail. Anal. 121, 105148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2020.105148 (2021).

Reder, M. D., Gonzalez, E. & Melero, J. J. Wind turbine failures-tackling current problems in failure data analysis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 753, 072027. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/753/7/072027 (2016).

Tabrizi, A. B., Whale, J., Lyons, T. & Urmee, T. Rooftop wind monitoring campaigns for small wind turbine applications: effect of sampling rate and averaging period. Renew. Energy. 77, 320–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2014.12.037 (2015).

Chagas, C. C. M. et al. From megawatts to kilowatts: A review of small wind turbine applications, lessons from the US to Brazil. Sustainability 12, e2760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072760 (2020).

Stoyanov, I., Iliev, T., Fazylova, A. & Yestemessova, G. A. Dynamic control model of the blades position for the vertical-axis wind generator by a program method. Inventions 8 2411–5134. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions8050120 (2023).

Tummala, A., Velamati, R. K., Sinha, D. K., Indraja, V. & Krishna, V. H. A review on small scale wind turbines. Renew. Sustainable Energy Reviews. 56, 1351–1371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.027 (2016).

Weir, T., Kumar, M., Glade, T. & Murty, T. S. Renewable energy can enhance resilience of small Islands. Nat. Hazards 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-020-04266-4 (2020).

Chen, T., Chen, Y., Gao, Z., Jiang, X. & Wang, J. Dynamic response characteristics analysis of small wind turbine’s rotor and nacelle. Renew. Energy Resour. 36, 1080–1085. https://doi.org/10.13941/j.cnki.21-1469/tk.2018.07.021 (2018).

Yang, S., Lin, K. & Zhou, A. Exploring the performance of horizontal axis wind turbine in yawed turbulent flows through wind tunnel experiments. Renew. Energy 243 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2025.122579 (2025).

Li, W., Zhao, W., Li, J. & Du, Y. Structural dynamic characteristic test of large wind turbine based on optical flow method and UAV. J. Hunan University:Natural Sci. 50, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.16339/j.cnki.hdxbzkb.2023117 (2023).

Bao, D. et al. Acta Energiae Solaris Sinica 43, 242–248 https://doi.org/10.19912/j.0254-0096.tynxb.2021-1333 (2022).

Li, D., Wang, X., Mo, W. & Zhang, X. Analysis on the influence of dynamic aerodynamic loads and component vibration of wind turbine on aeroelastic characteristics. J. Mech. Eng. 52, 165–173. https://doi.org/10.3901/JME.2016.14.165 (2016).

Liang, Z., Hu, F., Shi, Y., Zhang, Z. & Liu, L. Research of mast shadow effect on the average wind Speedand turbulence intensity by field experiment. J. Experiments Fluid Mech. 38, 88–97. https://doi.org/10.11729/syltlx20220010 (2024).

Shen, H. et al. Study on turbulent wind field of wind turbine site in High-Slope complex terrain. Eng. Mech. 42, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.6052/j.issn.1000-4750.2022.12.1098 (2025).

Pagnini, L. C., Burlando, M. & Repetto, M. P. Experimental power curve of small-size wind turbines in turbulent urban environment. Appl. Energy. 154, 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.04.117 (2015).

Wu, F., Yang, C., Wang, D. & Yang, L. Effects of turbulence intensity on dynamic characteristics and load of wind turbine. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agricultural Eng. 36, 48–55. https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2020.13.006 (2020).

Lubitz, W. D. Impact of ambient turbulence on performance of a small wind turbine. Renew. Energy. 61, 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2012.08.015 (2014).

Yin, J., Shen, W. Z., Sun, Z., Zhu, W. J. & Cho, H. A new blade element momentum theory for both compressible and incompressible wind turbine flow computations. Energy. Conv. Manag. 328 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2025.119619 (2025).

Rafiee, R., Moradi, M. & Khanpour, M. The influence of material properties on the aeroelastic behavior of a composite wind turbine blade. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 8 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4968600 (2016).

Rafiee, R. & Fakoor, M. Aeroelastic investigation of a composite wind turbine blade. Wind Struct. 17, 671–680. https://doi.org/10.12989/was.2013.17.6.671 (2013).

Hou, H., Shi, W., Xu, Y. & Song, Y. Actuator disk theory and blade element momentum theory for the force-driven turbine. Ocean Eng. 285 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.115488 (2023).

Pieniak, D. et al. The influence of geometric nonconformance of the SB4 tension clamps on their strength and elasticity characteristics. Sci. Rep. 14, 29540. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80944-8 (2024).

Yan, F., Lu, H. & Xiao, L. Fatigue life prediction of cracked cross beam of mining linear vibrating screen under Cyclic load. Sci. Rep. 14, 19631. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02936-6 (2024).

Yang, G. et al. Bolt loosening evaluation method based on normalized screw root equivalent stress and loosening life curve. Sci. Rep. 15, 20815. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02936-6 (2025).

Gaidai, O., Yakimov, V., Wang, F., Zhang, F. & Balakrishna, R. Floating wind turbines structural details fatigue life assessment. Sci. Rep. 13, 16312. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43554-4 (2023).

Guan, X. et al. Study on structural dynamic response of offshore wind turbine under floating ice load. Sci. Rep. 15, 17050. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00471-y (2025).

Srinivasa Sudharsan, G., Natarajan, K., Rahul, S. G. & Kumar, A. Active power control in horizontal axis wind turbine considering the fatigue structural load parameter using Psuedo adaptive- model predictive control scheme. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 57 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2023.103166 (2023).

61400-1, I. & Turbine, W. Wind energy generation systems–part 1: design requirements. Int. Electrotech. Commission (2019).

Wang, W., Chen, K., Bai, Y., Wang, J. & Comparative Study On Wind Speed Distribution Models Of Hohhot Suburb Based On Measured Data. Acta Energiae Solaris Sinica 42, 370–376 https://doi.org/10.19912/j.0254-0096.tynxb.2021-0130 (2021).

Earnest, J. & Rachel, S. Wind power technology third edition (PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd., 2019).

Aree & Pichai. Precise dynamic initialisation of fixed-speed wind turbines under active-stall and active-pitch controls from their aerodynamic power coefficients using unified Newton–Raphson power-flow approach. Iet Generation Transmission Distribution. 12, 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-gtd.2016.1225 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank the Key Laboratory of Wind Energy and Solar Energy Utilization Technology, Ministry of Education, for providing the essential experimental site for this study. Additional technical support was provided by the Inner Mongolia Key Laboratory of New Energy and Energy Storage Technology and the Inner Mongolia New Energy Productivity Promotion Center, both of which are affiliated with Inner Mongolia University of Technology. We also appreciate the valuable support and guidance in engineering applications from Yunda Energy Technology Group Co., Ltd. and Inner Mongolia Yufeng Mugang Energy Co., Ltd. Finally, the authors are grateful to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their rigorous and constructive comments.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 52266013), and the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region “Listed and Commanded” Project (grant No. 2024JBGS0025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Daorina Bao; Funding preparation: Yongshui Luo, Xiaohu Ao, Jingsen Chen; Data collection and sorting: Aoxiang Jiang, Zhongyu Shi; Draft manuscript writing: Daorina Bao, Jun Zhang ; All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bao, D., Zhang, J., Jiang, A. et al. Operational characteristics and blade fatigue life analysis of a novel variable-pitch wind turbine under natural wind conditions. Sci Rep 16, 2708 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32507-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32507-8