Abstract

The role of eosinophils in patients with cancer receiving systemic therapy based on immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has become a subject of increasing interest. The aim of the present study was to assess the prognostic role of absolute eosinophil count (AEC) and neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio (NER) in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) receiving nivolumab. The associations of AEC and NER at baseline and their relative changes (Δ) after one month of nivolumab therapy with progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and objective response rate (ORR) were analyzed. In total, 458 patients were included. Baseline AEC ≥ 70 cells/µL (PFS: HR: 0.663, p = 0.009; OS: HR: 0.583, p = 0.002), AEC one month after nivolumab initiation ≥ 70 cells/µL (PFS: HR: 0.544, p = 0.001; OS: HR: 0.331, p < 0.001) and NER < 65 one month after nivolumab initiation (PFS: HR: 0.552, p < 0.001; OS: HR: 0.326, p < 0.001) was associated with superior PFS and OS, and baseline NER < 65 was associated with superior OS (HR: 0.664, p = 0.014). Regarding early dynamics, ΔNER ≥ 125% was associated with inferior PFS (HR: 1.950, p = 0.001) and OS (HR: 2.680, p < 0.001), and ΔAEC <-30% was associated with inferior OS (HR: 2.132, p < 0.001). Higher ORR was associated with baseline AEC ≥ 70 cells/µL (p = 0.048), baseline NER < 65 (p = 0.010); and NER one month after nivolumab initiation < 65 (p = 0.025). The results of the present study suggest that eosinophil-based blood parameters including AEC and NER and their early dynamics during the course of treatment with nivolumab are promising and readily available prognostic biomarkers in patients with mRCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The landscape of systemic therapies for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) has expanded substantially in recent years. However, mRCC remains a formidable malignancy, characterized by its aggressive nature and uncertain long-term prognosis, necessitating novel treatment approaches. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), based on monoclonal antibodies targeting Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) or its ligand (PD-L1), have been established as the cornerstone of systemic therapy for mRCC. Initially, one decade ago, a randomized phase III study demonstrated a survival benefit for nivolumab, an anti- PD-1 monoclonal antibody, in patients with mRCC refractory to at least one line of antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI). Compared to everolimus, nivolumab led to a clinically meaningful improvement in terms of overall survival (OS), objective response rate (ORR) and health-related quality of life1. Subsequently, combination immunotherapy regimens have emerged and become the standard of care for the frontline treatment of most patients with mRCC2,3. Numerous combination immunotherapy regimens have been registered and are currently available for the first-line, including nivolumab + ipilimumab, nivolumab + cabozantinib, pembrolizumab + lenvatinib, avelumab + axitinib, and pembrolizumab + axitinib4,5,6,7,8.

With regard to the use of nivolumab in mRCC, it spans a variety of clinical settings - from combination regimens in the first-line setting to monotherapy in the second- or third-line setting following TKIs. While ICIs have revolutionized the systemic treatment of mRCC, a comprehensive understanding of mechanism of action remains crucial across all clinical aspects. In particular the search for prognostic and predictive biomarkers continues to be a major focus in the field of current urology oncology. Circulating immune cells, which can be easily assessed in the peripheral blood samples as a part of routine care, have recently become a subject of increasing interest. Eosinophils are granulocytic leukocytes traditionally associated with allergic responses and parasitic infections. Recent research, however, has highlighted eosinophil involvement in cancer, where they may play dual roles depending on the specific context. Tumor-associated eosinophils (TAEs) can contribute to anti-tumor immunity by releasing cytotoxic granules, such as Major basic protein (MBP) and eosinophil peroxidase, producing cytokines like IL-2 and IFN-γ, and promoting the recruitment of CD8⁺ T cells and dendritic cells9,10. Conversely, in certain settings, eosinophils may facilitate tumor progression by promoting angiogenesis, extracellular matrix remodeling, or immune suppression through IL-10 or TGF-β secretion11,12. The functional impact of eosinophils in cancer appears to be highly context-dependent, varying by cancer type, factors associated with tumor microenvironment (TME), and disease stage, making them a subject of growing interest in cancer immunology13. Notably, there is growing evidence suggesting a prognostic role of peripheral eosinophil-based parameters in patients with various malignancies receiving immunotherapy9.

The aim of the present retrospective study was to assess the prognostic role of absolute eosinophil count (AEC) and neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio (NER) at baseline and their early dynamics in patients with mRCC receiving nivolumab as second or further line of systemic therapy.

Patients and methods

Study design

Clinical data from patients with mRCC who received nivolumab monotherapy in the second or higher line between 2013 and 2025 were retrospectively reviewed and data from whole peripheral blood counts performed at baseline and one month after nivolumab treatment initiation were analyzed. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the association of AEC and NER at baseline, one month after nivolumab treatment initiation, and their relative change between baseline and after one month of treatment (ΔAEC, ΔNER) with patient outcomes including progression-free survival (PFS), OS and ORR.

The present analysis used data from seven cancer centers in the Czech Republic and three cancer centers in the Slovak Republic. Clinical data were obtained from the Renal Cell Carcinoma Information System II (RENIS II) registry (http://renis.registry.cz), which has been described previously. Data on eosinophil-based parameters were extracted from the hospital information systems and merged to the registry data. The RENIS II registry and the use of registry data for analysis were approved on October 28, 2019 (nr. 201928/52/MOU), by the Multicentre Ethics Committee of the Masaryk Memorial Cancer Institute in Brno, Czech Republic. An informed consent was signed by all the patients included in the study.

Patients and treatment

Nivolumab was administered intravenously as a single agent using one of the standard approved schedules (240 mg every two weeks or 480 mg every four weeks). The treatment was continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or patient refusal. None of the patients had received prior ICI therapy.

Outcome assessment

The follow-up visits including physical examination and routine laboratory tests were performed every two to four weeks, and computed tomography (CT) was performed every three to four months during the treatment. The objective response was assessed locally using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 in terms of: complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) and progressive disease (PD); objective response rate (ORR) was calculated as a sum of patients achieving CR or PR14.

Statistical analysis

Common descriptive statistics and observation frequencies were used to characterize the patient cohort. PFS has been calculated as the interval between treatment initiation and the documented progression or death. OS has been defined from treatment initiation until death, regardless of its cause. Patients without records of progression or death were censored at the date of their last follow-up. PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method (with linear interpolation to particular calculation points), along with 95% confidence intervals. The median follow-up duration was determined with the inverse Kaplan-Meier method. The relative changes were calculated by dividing the absolute changes by the initial (baseline) values and expressed in percent (in case of zero initial value, the relative change was set to a fixed limit of 6300%). The associations of AEC and NER with PFS and OS were assessed by means of univariable Cox proportional hazards model.

To identify optimal dichotomization thresholds for AEC, NER, and their early relative changes (ΔAEC and ΔNER), we used a semi-empirical approach based on stratified Cox-Mantel p-values plotted against all possible thresholds. Thresholds were selected to provide maximal separation of low- and high-risk groups across both PFS and OS outcomes, with preference for values that performed consistently across both endpoints. The following cut-off values were selected: AEC ≥ 70 cells/µL, NER < 65, ΔAEC <–30%, and ΔNER ≥ 125%. These thresholds were derived post hoc and should be considered exploratory, as no prior external validation exists in the mRCC setting.

A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was then used to assess the independence of AEC levels and NER values on other potential prognostic clinical factors. The associations of AEC levels and NER values with ORR were analyzed by means of the Fisher’s exact test. The level of statistical significance was set at α = 0.05, and all p-values and confidence intervals reported in the study are two-tailed. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica (Version 10Cz; StatSoft, Inc., TuIsa, OK, USA) and MATLAB (R2021a, The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

The study cohort included 458 mRCC patients receiving nivolumab monotherapy as the second or higher line of systemic therapy. The baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Survival outcomes

At the time of data analysis, 338 (73.8%) patients progressed on nivolumab, 274 (59.8%) patients died, and the median follow-up time was 34.4 months. Median PFS and OS for the whole cohort were 8.3 months (95% CI 6.9–10.1) and 23.8 months (95% CI 20.7–28.6), respectively.

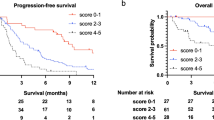

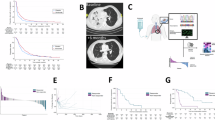

PFS and OS outcomes were significantly superior in patients with AEC ≥ 70 cells/µL at baseline (9.7 [95% CI 7.7–11.0] vs. 4.8 [95% CI 3.9–5.8] months, p = 0.004 and 26.4 [95% CI 22.3–32.5] vs. 14.4 [95% CI 8.2–20.8] months, p = 0.001, respectively), AEC one month after nivolumab initiation ≥ 70 cells/µL (9.9 [95% CI 7.9–11.3] vs. 5.1 [95% CI 3.4–7.3] months, p = 0.002 and 28.6 [95% CI 24.6–33.0] vs. 10.1 [95% CI 5.5–15.5] months, p < 0.001, respectively), baseline NER < 65 (10.1 [95% CI 8.1–11.3] vs. 4.8 [95% CI 3.5–5.4] months, p < 0.001 and 26.6 [95% CI 23.0–33.0] vs. 12.8 [95% CI 7.9–20.5] months, p < 0.001, respectively) and NER one month after nivolumab initiation < 65 (10.2 [95% CI 8.5–11.8] vs. 4.4 [95% CI 3.4–5.8] months, p < 0.001 and 29.7 [95% CI 25.5–33.8] vs. 8.1 [95% CI 5.3–13.1] months, p < 0.001, respectively). Regarding the early dynamics of the eosinophil-based parameters, PFS and OS outcomes were significantly inferior in patients with ΔAEC <−30% (7.5 [95% CI 4.8–8.8] vs. 9.6 [95% CI 7.4–11.1] months, p = 0.044 and 13.1 [95% CI 6.7–23.7] vs. 28.1 [95% CI 21.8–32.6] months, p < 0.001, respectively) and patients with ΔNER ≥ 125% (4.3 [95% CI 3.4–6.3] vs. 9.7 [95% CI 8.0–11.3] months, p < 0.001 and 11.7 [95% CI 5.2–15.5] vs. 26.3 [95% CI 22.5–31.9] months, p = 0.001, respectively). The Kaplan-Meier estimates of patient survival are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Complete survival data for the specified subgroups are shown in Supplementary Table 1 S.

The multivariable Cox proportional hazards models included age, gender, synchronous metastatic disease, grade, line of therapy, International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) risk group, bone metastases, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), and the assessed eosinophil-based parameter. The results of the multivariable Cox proportional hazards models regarding the assessed eosinophil-based parameters are summarized in Table 2 (see Supplementary Table 2 S for detailed results of the multivariable Cox models performed for each eosinophil-based parameter separately). In the multivariable Cox proportional hazards models (performed for each eosinophil-based parameter separately), baseline AEC ≥ 70 cells/µL (PFS: HR: 0.663 [95%CI 0.487–0.901], p = 0.009; OS: HR: 0.583 [95%CI 0.413–0.823], p = 0.002), AEC one month after nivolumab initiation ≥ 70 cells/µL (PFS: HR: 0.544 [95%CI 0.382–0.776], p = 0.001; OS: HR: 0.331 [95%CI 0.227–0.485], p < 0.001), and NER one month after nivolumab initiation < 65 (PFS: HR: 0.552 [95%CI 0.402–0.757], p < 0.001; OS: HR: 0.326 [95%CI 0.230–0.463], p < 0.001) remained an independent significant factors associated with superior PFS and OS, and baseline NER < 65 remained an independent significant factor associated with superior OS (HR: 0.664 [95%CI 0.478–0.922], p = 0.014) but not PFS (HR: 0.750 [95%CI 0.558–1.009], p = 0.058). Furthermore, the multivariable Cox proportional hazards models show that ΔNER ≥ 125% remained an independent significant factor associated with inferior PFS (HR: 1.950 [95%CI 1.319–2.882], p = 0.001) and OS (HR: 2.680 [95%CI 1.735–4.140], p < 0.001), and ΔAEC <−30% remained an independent significant factor associated with inferior OS (HR: 2.132 [95%CI 1.447–3.145], p < 0.001).

When baseline characteristics were stratified by eosinophil- and NER-related parameters, patients with lower AEC and higher NER values at baseline and at one month, as well as those with decreasing AEC or increasing NER during treatment, were significantly more likely to have adverse prognostic features. In particular, these patients more frequently presented with poorer ECOG performance status (p-values 0.002 to < 0.001) and higher IMDC risk categories (p-values 0.006 to < 0.001, with a nonsignificant trend for ΔAEC, p = 0.086). Similar associations were observed for prior nephrectomy and the presence of synchronous metastases. Full results are provided in Supplementary Table S3.

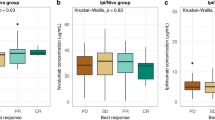

Objective response rate

ORR was 32.3% for patients with baseline AEC ≥ 70 cells/µL vs. 20.0% for patients with < 70 cells/µL (p = 0.048); 33.2% for patients with baseline NER < 65 vs. 18.1% for patients with ≥ 65 (p = 0.010); 33.0% for patients with NER one month after nivolumab initiation < 65 vs. 18.8% for patients with ≥ 65 (p = 0.025) (Fig. 3). No significant associations with ORR were found when the patients were stratified according to AEC one month after nivolumab initiation (p = 0.099), ΔAEC (p = 0.404), and ΔNER (p = 0.453).

Comparison of overall response rate (complete remission (CR) or partial remission (PR)) according to baseline absolute eosinophil count (AEC) (a), relative change of AEC after one month of nivolumab therapy (ΔAEC) (b), baseline neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio (NER) (c), and NER after one month of nivolumab therapy (d).

Discussion

Eosinophils play a multifaceted role in cancer, exhibiting both pro- and anti-tumorigenic activities depending on the cancer type, TME and specific signaling pathways involved9. They contribute to anti-tumor immunity by promoting cytotoxic T cell recruitment, modulating macrophage activity, and releasing granules with tumoricidal properties. However, under certain conditions, they may promote angiogenesis or suppress effective immune responses. As a result, eosinophils have become a focus of increasing interest in cancer research. Notably, eosinophils have emerged as promising candidates for cellular prognostic and predictive biomarkers and even as potential effector cells in cancer therapy15,16,17,18. The results of the present study demonstrate that AEC and NER assessed at baseline and one month after nivolumab initiation, as well as their relative change after one month of the treatment (ΔAEC and ΔNER) are associated with outcome in patients with mRCC.

Recently, several studies have suggested an association between eosinophil-based parameters in peripheral blood, including AEC and NER, and outcome in patients with various malignancies, especially in those treated with ICIs. However, available data are limited and equivocal. Thus, the prognostic and/or predictive role of eosinophil-based peripheral blood parameters remains poorly understood. Higher baseline AEC has been positively correlated with response and survival in patients with advanced melanoma treated with ipilimumab or pembrolizumab, patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma receiving nivolumab, patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with ICIs, and patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma treated with ICIs19,20,21,22,23. In particular, data on the prognostic role of baseline AEC for mRCC are limited and inconclusive. Giommoni et al. reported an association between high baseline AEC and higher ORR (p = 0.003) in 168 patients with various cancers, including 43 (26.0%) cases of mRCC24. This is in agreement with the results of the present study. On the other hand, Herrmann et al. did not find correlation between baseline AEC and response to nivolumab in a small retrospective study including 65 patients25. However, the interpretation of the negative results of this study is difficult because of a small number of patients. Other studies focusing on eosinophil-based blood parameters in mRCC did not report results specifically for baseline AEC values. The findings derived from experimental studies provide mechanistic evidence that eosinophils, as effector cells, play an active role in the antitumor response induced by ICI treatment26,27. Eosinophils are closely involved in regulating macrophage polarization and promoting the recruitment of CD8 + T lymphocytes28,29. There has been accumulating evidence suggesting that an early increase of AEC following ICI treatment initiation is associated with improved patient outcomes in various malignancies30. Notably, the data in mRCC are currently only available from a few retrospective studies with relatively small patient cohorts. Yoshimura et al. reported significantly longer PFS and OS for patients with high AEC compared to those with low AEC assessed one month after nivolumab initiation (p = 0.03 and p = 0.009, respectively) in a retrospective study including 83 mRCC patients receiving nivolumab in the second or further line of systemic therapy31. Similarly, a Dutch registry-based retrospective study including 264 patients showed that an increase in AEC by week 8 predicted improved OS (p = 0.003) and PFS (p < 0.001)32. These findings are in agreement with the present results.

Combined peripheral blood cellular biomarkers, such as neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) or platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), have been proposed to predict therapeutic response and prognosis in cancer patients treated with ICIs33,34,35. In the scope of eosinophil-based biomarkers, NER has recently appeared to be a promising predictive blood cellular biomarker in mRCC. In a retrospective study including 110 mRCC patients treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab, PFS (HR: 0.50, p < 0.01) and OS (HR: 0.31, p < 0.01) were significantly longer and also the ORR (40% vs. 21.8%, p = 0.04) was higher in patients with higher baseline NER36. The study was subsequently expanded to include 150 mRCC patients and was complemented by analyzing NER dynamics after 6 weeks of treatment. This analysis showed that decreased NER > 50% was associated with improved PFS (adjusted HR: 0.55, p = 0.03) and OS (adjusted HR: 0.37, p = 0.02)37. Although the analysis of NER dynamics in the present study was performed to identify patients at high risk of progression or death, the results are similar and show that an increase in NER ≥ 125% has a strong negative impact on PFS and OS. An important study recently conducted by Tucker et al. focused on the association between baseline NER and outcomes of mRCC patients enrolled in the randomized phase 3 clinical trial, JAVELIN Renal 101, comparing avelumab plus axitinib with sunitinib in the first-line setting38. The results of this post hoc exploratory analysis suggest that baseline NER may serve as a prognostic biomarker for OS in mRCC patients, regardless of the treatment regimen. However, the analyses of potential differences in treatment effects with avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib according to the NER value remained inconclusive. Similarly, Yildrim et al. suggested that low baseline NER is associated with improved PFS (HR: 0.67, p = 0.003) and OS (HR: 0.63, p = 0.004) in a retrospective study including 401 mRCC patients treated with ICIs in a routine clinical setting39.

The present study has several limitations and strengths. The principal limitations arise from the retrospective design and the lack of prospective control.

There was no centralized review of radiological imaging, and peripheral blood cell counts were obtained from different certified laboratories. Furthermore, the use of nivolumab monotherapy following the failure of TKIs reflects historical practice; while this approach was standard at the time of patient inclusion, most current mRCC patients now receive first-line combination regimens. Therefore, the generalizability of our findings to modern treatment paradigms may be limited. The cut-off values for AEC, NER, and their early dynamics were selected based on a semi-empirical approach maximizing statistical separation by scanning across the p-values resulting from stratifications based upon all possible thresholds. While these thresholds have not been previously validated and should be considered exploratory, they were selected to optimize prognostic discrimination across both PFS and OS outcomes and to remain clinically interpretable. Furthermore, we acknowledge that the AEC ≥ 70 cells/µL threshold identified a large proportion of patients as “high AEC”, which may limit its clinical discrimination. However, this cut-off was chosen to optimize separation of survival outcomes rather than to balance subgroup sizes. Our intention was to identify a subgroup of patients at increased risk, and the selected threshold demonstrated a consistent prognostic value across analyses. Similar thresholds have been used in other ICI-treated populations, but they were determined post hoc and should be considered exploratory, as no external validation has yet been performed. The absence of an independent validation cohort represents a limitation. Further prospective studies are necessary to confirm the robustness and clinical utility of these thresholds. In addition, eosinophil counts may be affected by a variety of non-tumor-related factors, including infections, allergic conditions, and the use of systemic corticosteroids. While our multivariable models adjusted for known clinical parameters, the retrospective nature of the study precluded systematic documentation of all relevant confounders, such as concomitant medications or transient inflammatory states. This limitation may have influenced the observed associations and underscores the need for more granular data collection in future prospective validation efforts. In addition, stratified analyses showed that unfavorable eosinophil- and NER-related profiles (low AEC, high NER, decreasing AEC, or increasing NER) were associated with adverse baseline characteristics, including poorer ECOG performance status and higher IMDC risk categories. These correlations support the biological plausibility of eosinophil-based markers, but also raise the possibility of collinearity with established prognostic models. Importantly, in multivariable Cox analyses including IMDC and other available covariates, eosinophil- and NER-based parameters retained their prognostic significance, supporting their potential independence from established risk factors. Nevertheless, residual confounding cannot be excluded given the retrospective nature of the study, underscoring the need for prospective validation to determine the independent prognostic value of these parameters. Furthermore, we acknowledge that our cohort reflects a historical treatment setting, in which nivolumab was used as monotherapy following TKI failure, whereas current guidelines increasingly favor ICI-based combination therapies in the first-line setting. This temporal shift in treatment paradigms may limit the direct applicability of our findings to today’s practice. Nevertheless, the immune-related mechanisms reflected by eosinophil dynamics may remain relevant across different ICI-based strategies. Therefore, our results contribute valuable biological insights into the prognostic potential of eosinophil-based parameters, especially in the context of immune activation and early treatment response. While prospective validation in modern treatment settings will be essential, the present study offers a large, homogeneous, real-world cohort uniquely suited to exploring these immune biomarkers.

Despite these limitations, the present study remains highly relevant and reliable, as it examines eosinophil-based blood parameters in a large and well-defined cohort of patients with mRCC who underwent immunotherapy with nivolumab. Although eosinophil-related biomarkers have been studied in other types of cancer, evidence specific to metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) is limited. Most previous studies either included small mRCC subgroups or mixed tumor cohorts, limiting their interpretability for this patient population. To our knowledge, the present study is one of the largest single-cohort studies focusing exclusively on mRCC patients treated with nivolumab monotherapy. Moreover, the simultaneous assessment of both baseline values and early dynamics of AEC and NER adds an important temporal dimension that may help elucidate early immune responses associated with clinical outcomes. While the IMDC model remains the standard prognostic framework in mRCC, it is static and does not reflect early immune dynamics. The present study results suggest that ΔNER, in particular, may serve as a strong and accessible dynamic biomarker of early treatment response. Eosinophil-based parameters are readily available, inexpensive, and routinely monitored. If validated prospectively, their early dynamics, particularly ΔNER, could support clinical decision-making by identifying patients at risk of early progression and potentially complement established risk models such as IMDC. However, we acknowledge that the clinical applicability of these markers is not yet established. Given the retrospective nature of our study and the exploratory cut-offs used, our findings should be viewed as hypothesis-generating. Future prospective validation in larger cohorts will be essential to confirm the utility and robustness of AEC and NER dynamics as potential prognostic adjuncts.

Conclusions

The results of the present study suggest that eosinophil-based blood parameters including AEC and NER assessed at baseline and their early dynamics during the course of treatment with nivolumab are promising and readily available prognostic biomarkers in patients with mRCC. Further research is warranted to clarify the role of eosinophils in cancer, particularly the role of eosinophil-based blood parameters in the outcome of cancer patients treated with immunotherapy.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient data security but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable’ for that section.

References

Motzer, R. J. et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl. J. Med. 373, 1803–1813. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1510665 (2015).

Powles, T. et al. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 35, 692–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2024.05.537 (2024).

Bex, A. et al. European association of urology guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: the 2025 update. Eur. Urol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2025.02.020 (2025).

Motzer, R. J. et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl. J. Med. 378, 1277–1290. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1712126 (2018).

Choueiri, T. K. et al. Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib versus Sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl. J. Med. 384, 829–841. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2026982 (2021).

Motzer, R. et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma. N Engl. J. Med. 384, 1289–1300. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2035716 (2021).

Motzer, R. J. et al. Avelumab plus axitinib versus Sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl. J. Med. 380, 1103–1115. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1816047 (2019).

Rini, B. I. et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus Sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl. J. Med. 380, 1116–1127. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1816714 (2019).

Grisaru-Tal, S., Itan, M., Klion, A. D. & Munitz, A. A new dawn for eosinophils in the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 20, 594–607. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-020-0283-9 (2020).

Carretero, R. et al. Eosinophils orchestrate cancer rejection by normalizing tumor vessels and enhancing infiltration of CD8⁺ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 16, 609–617. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3159 (2015).

Reichman, H. et al. Activated eosinophils exert anti-tumorigenic activities in colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 7, 388–400. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0543 (2019).

Blanchard, C. & Rothenberg, M. E. Biology of the eosinophil. Adv. Immunol. 101, 81–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2776(08)01003-1 (2009).

Simson, L. & Foster, P. S. Eosinophils and cancer. In: (eds Rothenberg, M. E. & Hogan, S. P.) Eosinophils in Health and Disease. Elsevier; :509–523. (2013).

Therasse, P. et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumours. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92, 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/92.3.205 (2000).

Sosman, J. A. et al. Evidence for eosinophil activation in cancer patients receiving Recombinant interleukin-4: effects of interleukin-4 alone and following interleukin-2 administration. Clin. Cancer Res. 1, 805–812 (1995).

Ellem, K. A. et al. A case report: immune responses and clinical course of the first human use of granulocyte/macrophage-colony-stimulating-factor-transduced autologous melanoma cells for immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 44, 10–20 (1997).

Simon, H. U. et al. Interleukin-2 primes eosinophil degranulation in hypereosinophilia and wells’ syndrome. Eur. J. Immunol. 33, 834–839. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.200323634 (2003).

Gebhardt, C. et al. Myeloid cells and related chronic inflammatory factors as novel predictive markers in melanoma treatment with ipilimumab. Clin. Cancer Res. 21, 5453–5459. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0676 (2015).

Martens, A. et al. Baseline peripheral blood biomarkers associated with clinical outcome of advanced melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 2908–2918. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2206 (2016).

Weide, B. et al. Baseline biomarkers for outcome of melanoma patients treated with pembrolizumab. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 5487–5496. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0583 (2016).

Hude, I. et al. Leucocyte and eosinophil counts predict progression-free survival in relapsed or refractory classical hodgkin lymphoma patients treated with PD1 Inhibition. Br. J. Haematol. 181, 837–840. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14705 (2018).

Chu, X. et al. Association of baseline peripheral-blood eosinophil count with immune checkpoint inhibitor-related pneumonitis and clinical outcomes in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Lung Cancer. 150, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.08.015 (2020).

Mota, J. M. et al. Pretreatment eosinophil counts in patients with advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors. J. Immunother. 44, 248–253. https://doi.org/10.1097/CJI.0000000000000372 (2021).

Giommoni, E. et al. Eosinophil count as predictive biomarker of immune-related adverse events in immune checkpoint inhibitors therapies in oncological patients. Immuno 1, 253–263. https://doi.org/10.3390/immuno1030017 (2021).

Herrmann, T. et al. Eosinophil counts as a relevant prognostic marker for response to nivolumab in the management of renal cell carcinoma: a retrospective study. Cancer Med. 10, 6705–6713. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.4208 (2021).

Zheng, X. et al. CTLA4 Blockade promotes vessel normalization in breast tumors via the accumulation of eosinophils. Int. J. Cancer. 146, 1730–1740. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.32829 (2020).

House, I. G. et al. Macrophage-derived CXCL9 and CXCL10 are required for antitumor immune responses following immune checkpoint Blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 487–504. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1868 (2020).

Yoon, J. et al. Eosinophil activation by toll-like receptor 4 ligands regulates macrophage polarization. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 7, 329. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2019.00329 (2019).

Cheng, J. N. et al. Radiation-induced eosinophils improve cytotoxic T lymphocyte recruitment and response to immunotherapy. Sci. Adv. 7, eabc7609. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abc7609 (2021).

Lang, B. M. et al. Long-term survival with modern therapeutic agents against metastatic melanoma: Vemurafenib and ipilimumab in a daily life setting. Med. Oncol. 35, 24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-018-1084-9 (2018).

Moreira, A., Leisgang, W., Schuler, G. & Heinzerling, L. Eosinophilic count as a biomarker for prognosis of melanoma patients and its importance in the response to immunotherapy. Immunotherapy 9, 115–121. https://doi.org/10.2217/imt-2016-0138 (2017).

Yoshimura, A. et al. The prognostic impact of peripheral blood eosinophil counts in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with nivolumab. Clin. Exp. Med. 24, 111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-024-01370-8 (2024).

Verhaart, S. L. et al. Real-world data of nivolumab for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma in the netherlands: an analysis of toxicity, efficacy, and predictive markers. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer. 19, 274e1–27416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clgc.2020.10.003 (2021).

Templeton, A. J. et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 106, dju124. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju124 (2014).

Guthrie, G. J. et al. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: experience in patients with cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 88, 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.03.010 (2013).

Templeton, A. J. et al. Prognostic role of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 23, 1204–1212. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0016 (2014).

Tucker, M. D. et al. Association of baseline neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio with response to nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Biomark. Res. 9, 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-021-00334-4 (2021).

Chen, Y. W. et al. The association between a decrease in on-treatment neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio at week 6 after ipilimumab plus nivolumab initiation and improved clinical outcomes in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 14, 3830. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14153830 (2022).

Tucker, M. et al. Association between neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio and efficacy outcomes with avelumab plus axitinib or Sunitinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: post hoc analyses from the JAVELIN renal 101 trial. BMJ Oncol. 3, e000181. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjonc-2023-000181 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The Authors would like to thank all patients who voluntarily took part in the study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Charles University Research Fund (Cooperatio No. 43—Surgical Disciplines), the Institutional Research Fund of University Hospital Pilsen, FN 00669806 and by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement N856620 and by the project National Institute for Cancer Research—NICR (Programme EXCELES, ID Project No. LX22NPO5102)—Funded by the European Union—Next Generation EU. Funders played no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.F. and K.R. designed the study; O.F., K.R., T.B., H.Š., A.P., M.V., P.H., J.K., M.M., A.Z., M.S., M.T., P.P., J.K., R.L., L.G., A.S., K.Š., J.O., D.Š., P.S., B.H., and P.P. collected clinical data; O.F., P.P., and P.H. wrote the manuscript with support from all authors; P.H. performed statistical analyzes, Tables and Figures.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Ondřej Fiala received honoraria from Novartis, Janssen, Merck, Ipsen, BMS, MSD, Pierre Fabre, and Pfizer for consultations and lectures unrelated to this project.Katarina Rejlekova has received payment for speakers’ bureaus, presentations, lectures or educational events from Bayer, Novartis, Ipsen, Merck and Pfizer. All the above are unrelated to this paper.Tomas Buchler has received research support: AstraZeneca, Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, Exelixis, Merck KGaA, MSD, and Novartis; consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Astellas, Janssen, and Sanofi/Aventis; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Ipsen, Bristol Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Roche, Servier, Accord, MSD, and Pfizer. All unrelated to the present paper. All of the above are unrelated to the present paper.Hana Študentová has received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, MSD, Ipsen, Novartis, Astellas and Janssen; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, or educational events from Ipsen, Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, MSD, and Pfizer. All of the above are unrelated to the present paper.Alexandr Poprach has received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Roche, Eisai, Astellas, Johnson & Johnson, Zentiva, Novartis, Pfizer, Merck, MSD, Ipsen; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Ipsen, Bristol Myers Squibb, MSD, Merck, Novartis, Eisai, Astellas, Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer. All of the above are unrelated to the present paper.Michal Vočka has received consulting fees from Merck, Roche, MSD; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from BMS, MSD, Merck, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Roche and Pfizer. All of the above are unrelated to the present paper.Jindřich Kopecký has received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Merck, MSD, Ipsen; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Ipsen, Bristol Myers Squibb, MSD, Merck, Novartis and Pfizer. All of the above are unrelated to the present paper.Martin Matějů has received consulting fees from Novartis, MSD, Astellas; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Ipsen, BMS, MSD, Merck, Novartis, Eisa, AstraZeneca, Roche and Pfizer. All of the above are unrelated to the present paper.Radka Lohynská has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Roche, Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, MSD and Merck. All of the above are unrelated to the present paper.Bohuslav Melichar received honoraria from Novartis, Pfizer, Bayer-Schering, Astellas, and Roche for lectures and advisory boards unrelated to this project.Patrik Palacka has received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Astellas, Pfizer and Merck; payment for speakers’ bureaus, presentations, lectures or educational events from Bayer, MSD, Novartis, Ipsen, Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Astellas and Pfizer. All the above are unrelated to this paper.All other authors have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors have approved the manuscript for publication.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in accordance with the study protocol, the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki as well as those indicated in the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Note for Guidance on Good Clinical Practice (GCP; ICH E6, 1995), and all applicable regulatory requirements. RENIS II registry was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Masaryk Memorial Cancer Institute, Brno, Czech Republic. All patients provided informed consent. For deceased or untraceable individuals, the Institutional Review Board of the coordinating center waived the requirement for consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fiala, O., Rejleková, K., Buchler, T. et al. Baseline and early changes in eosinophil count and neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio predict outcomes in metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab. Sci Rep 16, 2811 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32593-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32593-8