Abstract

Electrostatic monitoring technology for aero-engines has demonstrated considerable capability in early fault warning. However, raw electrostatic signals often contain significant noise and exhibit low signal-to-noise ratios, making denoising essential to improve the accuracy of fault-related information extraction. To address the issue of coupled noise in electrostatic signals, this study introduces methodologies based on Improved Complete Ensemble EMD with Adaptive Noise (ICEEMDAN), Autocorrelation Function (ACF), and Wavelet Soft-thresholding (WTD). We investigate the criteria and principles for screening intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) and propose a joint denoising algorithm, along with its specific procedure, based on IMF-optimized reconstruction and wavelet thresholding. The proposed method is validated using both simulated signals and actual electrostatic signals collected from a micro-turbojet engine test. Comparisons with other denoising techniques are conducted. Simulation results indicate that the proposed method improves denoising performance in terms of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), mean square error (MSE), and normalized cross-correlation (NCC). Test results further demonstrate that the method effectively suppresses random noise and power frequency interference while preserving useful abnormal particle signals more effectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gas path components are among the core elements of aero-engines. The extreme operating conditions of these engines render these components highly susceptible to failures and performance degradation, making effective condition monitoring essential. Conventional gas path monitoring techniques primarily rely on measurements of vibration, pressure, and exhaust temperature. However, these methods capture only indirect manifestations of faults, which typically become detectable only after a fault has already occurred, thus lacking the capability for early fault warning. In recent years, electrostatic monitoring technology has emerged as a research focus in engine condition monitoring due to its recognized sensitivity to incipient faults in the engine gas path1. Unlike conventional approaches, electrostatic monitoring detects changes in electrostatic levels within engine exhaust gases, which may indicate the presence of fault-related particles, thereby offering enhanced fault detection capability. Beyond gas path monitoring, electrostatic sensing also demonstrates significant potential in oil debris monitoring owing to its high sensitivity2,3.

In electrostatic monitoring, signal processing is a fundamental step that ensures accurate subsequent feature extraction and fault identification. The complex acquisition environment often introduces various types of noise. When useful fault-related particle signals are contaminated by noise, feature extraction and analysis are severely compromised, considerably diminishing monitoring effectiveness4. Typical noise interference in electrostatic signals includes power frequency interference, Gaussian white noise, and low-amplitude random impulse noise. Wen et al.5 investigated a wavelet-based denoising method for electrostatic signals, demonstrating its effectiveness against random white noise. However, due to the multi-component noise present in electrostatic signals, selecting an appropriate wavelet basis function is often a challenging task. Moreover, once selected, the wavelet basis constrains the flexibility of the denoising process. To address power frequency noise, Li et al.6 applied adaptive filtering and independent component analysis (ICA), finding that ICA effectively suppressed such interference while preserving other spectral components. Nonetheless, ICA requires prior knowledge to predefine the number of blind sources, which also limits algorithmic adaptability. Jiang et al.7 studied empirical mode decomposition (EMD)-based denoising using measured electrostatic signals. Their research demonstrated that EMD offers notable overall denoising performance, mitigating both power frequency interference and random white noise. However, a major limitation of plain EMD is the need to reconstruct Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) without clear criteria for IMF selection, which can potentially lead to the loss of useful signal information. On the hardware side, Fu et al.8 developed an active second-order low-pass filter circuit designed to suppress noise at the circuit level based on the characteristics of electrostatic signals. In the broader field of rotating machinery signal analysis, methods such as wavelet thresholding, wavelet packet decomposition, and compressed sensing are also widely employed for signal denoising.

Yin9 proposed a denoising method for electrostatic signals based on optimized reconstruction of EMD modal components combined with sparse representation. This approach effectively suppresses random noise while preserving useful signals from abnormal particles. Although EMD-based methods are among the most effective in extracting weak fault-related features from electrostatic signals, EMD itself is inherently limited in processing nonlinear and non-stationary signals, often suffering from mode mixing issues10. To address this, Liu et al.11,12 employed the Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (CEEMDAN) for electrostatic signal decomposition. However, CEEMDAN tends to generate spurious modes in the initial stages of decomposition, which may compromise the accuracy of the resulting signal components. Zhong et al.13 applied Total Variation Denoising (TVD) to suppress noise in electrostatic signals from aero-engine exhaust. The fundamental principle of TVD is to reduce noise while preserving significant edge features in the signal by minimizing its total variation. This approach effectively smooths noise without compromising abrupt transitional structures, making it particularly suitable for processing signals that exhibit piecewise constant or abrupt change characteristics. However, TVD also presents notable limitations: it tends to introduce staircase artifacts in smoothly varying regions, resulting in spurious piecewise constant behavior that compromises the integrity of fine details. Moreover, the denoising performance is highly sensitive to the selection of the regularization parameter, whose optimization often lacks adaptability, requiring tedious manual tuning that is susceptible to subjective influence.

More advanced mode decomposition approaches, such as variational mode decomposition (VMD)14, time-varying filtering-based empirical mode decomposition (TVF-EMD)15, and Fourier-based intrinsic filter decomposition (FIFD)16, have also been introduced in recent years. While these methods provide strong performance in controlled environments, they typically require predefined mode numbers, bandwidth constraints, or iterative optimization. For aero-engine electrostatic signals characterized by unknown spectral structure, non-stationarity, intermittency, and low signal-to-noise ratios, determining these parameters adaptively is highly challenging. Furthermore, their increased algorithmic complexity and parameter sensitivity may hinder the real-time applicability of these systems in engineering monitoring.

To address these limitations, a joint denoising algorithm based on Improved Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (ICEEMDAN) decomposition, IMFs optimization using the autocorrelation function, and wavelet soft-thresholding is proposed. The raw electrostatic signal is first decomposed into multiple IMFs using the ICEEMDAN algorithm. An Autocorrelation Function (ACF) based metric is then employed to evaluate and categorize IMFs into signal-dominant and noise-dominant groups. Wavelet soft-thresholding (WTD) is subsequently applied to the noise-dominant group to extract weak yet meaningful information, and the reconstructed signal is obtained by combining processed and unprocessed IMFs.

In this study, the present algorithm intentionally integrates three complementary yet robust modules—ICEEMDAN decomposition, ACF-based IMF screening, and wavelet soft-thresholding—into a unified denoising framework tailored for aeroengine gas-path electrostatic signals. ICEEMDAN improves upon CEEMDAN by mitigating spurious modes and stabilizing decomposition for nonlinear, non-stationary, and weakly impulsive signals17. The subsequent ACF-based criterion provides a simple, parameter-light, and interpretable means of distinguishing signal-dominant from noise-dominant IMFs, without requiring any prior assumptions about the underlying spectral content. Finally, wavelet soft-thresholding further extracts weak particle-induced impulsive components buried in noise-dominant IMFs while preserving useful transient details. The integration of these elements allows the proposed method to achieve a favorable balance among denoising performance, robustness to multi-source interference, computational efficiency, and engineering applicability—advantages that are difficult to obtain through a single advanced decomposition technique alone.

The effectiveness of the proposed method is validated using both simulated signals and real test data collected from a micro-turbojet engine, and is compared against several classical denoising approaches. Comparative results demonstrate that the proposed approach outperforms several classical denoising methods, including wavelet threshold denoising (WTD), hybrid EMD–WTD, and other state-of-the-art techniques13,14,18,19,20, in terms of denoising performance.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 introduces the theoretical analysis of the designed algorithm. Section 3 details the analysis of the simulation signal. The experimental signal analysis is shown in Sect. 4. Finally, Sect. 5 summarizes the main conclusions.

Theoretical analysis of the method

ICEEMDAN

The ICEEMDAN is employed in this study to address the nonlinearity, non-stationarity, and intermittency of aeroengine gas-path electrostatic signals. ICEEMDAN enhances decomposition stability by mitigating spurious modes and reducing residual noise in the early stages of decomposition.

Following Colominas et al.17, the ICEEMDAN procedure can be summarized as follows. Let 〈⋅〉 denotes the ensemble average, x is the original signal, X(i) is the signal after adding white noise, ω(i) is the white noise when the mean and unit variance are all zero, M(⋅) is the local mean of the signal, Ek(⋅) is the k-th IMF obtained through EMD, and βk is the noise coefficient adjusted at the k-th stage. The decomposition steps are:

-

Step 1:

Construct signal \(x^{{^{{(i)}} }} = x + \beta _{{_{0} }} E_{{_{1} }} (\omega ^{{(i)}} )\), then their local means \(M\left( {x^{{\left( i \right)}} } \right)\) are computed to obtain the first residual: \(r1 = \left\langle {M\left( {x^{{\left( i \right)}} } \right)} \right\rangle\).

-

Step 2:

The first component is obtained by subtracting the initial residual from the original signal:

$$IMF_{1} = x - r_{1}$$ -

Step 3:

The second residual is constructed: \(r2 = \left\langle {M\left( {r1 + \beta _{1} E_{2} \left( {\omega ^{{\left( i \right)}} } \right)} \right)} \right\rangle\), and the second IMF is computed:

$$IMF_{2} = r_{1} - r_{2} = r_{1} - \left\langle {M\left( {r_{1} + \beta _{1} E_{2} \left( {\omega ^{{\left( i \right)}} } \right)} \right)} \right\rangle$$ -

Step 4:

For k=3,4,…,K, the k-th residual is subtracted to obtain the value of the k-th component: \(IMF_{k} = r_{{k - 1}} - r_{k}\).

-

Step 5:

Repeat Step 4 until all components are obtained.

The constant βk−1 is chosen to adjust the signal-to-noise ratio between the added noise and the residual. When k = 1, β0=ε0⋅std(x)/std(E1ω((i))); for k≥2, βk=ε0⋅std(rk). Here, ε0 denotes the reciprocal of the desired signal-to-noise ratio between the input signal and the initially added noise, and std(rk) represents the standard deviation operation.

ICEEMDAN was further selected in this study because its algorithmic formulation provides several technical advantages that are particularly relevant to aeroengine electrostatic signals. First, the ensemble-mean local mean operator used in ICEEMDAN suppresses the spurious modes observed in CEEMDAN, producing IMFs with markedly improved stability under strong noise contamination. Second, the noise-assisted decomposition strategy allows ICEEMDAN to separate broadband random noise into the first few IMFs more effectively, which directly benefits subsequent IMF screening using ACF. Third, ICEEMDAN preserves intermittent impulsive events without excessive attenuation because its residual-update mechanism adapts well to transient structures. These algorithm-level properties make ICEEMDAN well-suited for processing low-SNR, sporadic, and highly non-stationary electrostatic signals encountered in aeroengine exhaust flows.

ACF

Whether employing EMD, EEMD, or CEEMDAN, not every intrinsic mode function (IMF) resulting from the decomposition accurately captures the meaningful features of the original signal X(t). Identifying relevant IMFs is crucial for both information extraction and noise suppression. In general, the stronger the correlation between an IMF and X(t), the more effectively it represents signal components. Therefore, a correlation coefficient-based approach is utilized to evaluate the relationship between each IMF and the input signal X(t), thereby facilitating the selection of informative modes. X(t) denote the correlation coefficient between the i-th IMF and X(t), defined as follows21,22:

Additionally, the sampled autocorrelation function (ACF) is incorporated to assess the statistical significance of each IMF. Autocorrelation is widely used to detect repeating patterns or periodicities within signals. For a discrete signal, the ACF quantifies the cross-correlation of the signal with a time-lagged version of itself. The sample ACF for the j-th IMF is given by:

where represents the time lag, and \(\:{\stackrel{-}{c}}_{j}\) is the mean of the j-th IMF.

Within time series analysis, the ACF helps evaluate the degree of periodicity in the data. Since white noise samples are independent and identically distributed, their ACF values are negligible beyond lag zero. In contrast, vibration signals with imbalances often exhibit inherent periodic structures, leading to significant autocorrelation at non-zero lags. Hence, the ACF magnitude serves as an indicator of periodic content within an IMF: lower ACF values suggest a lack of coherent periodic structure, typically characterizing noise-dominant components.

It is worth noting that the ACF in this study is applied not to the raw electrostatic signal but to the IMFs obtained through ICEEMDAN decomposition. Since each IMF is narrow-band and approximately stationary, the ACF serves as an effective low-order statistic to distinguish periodic or impulsive components from stochastic noise. Noise-dominant IMFs exhibit near-zero autocorrelation for nonzero lags, whereas signal-bearing IMFs retain identifiable correlation structures. Although more advanced nonlinear measures, such as mutual information or entropy-based criteria, could also be used, they require high computational complexity and parameter tuning, making them less suitable for engineering applications that may eventually require real-time implementation. Thus, ACF provides a simple, interpretable, and computationally efficient criterion for IMF screening in the proposed framework.

WTD

Wavelet threshold denoising was pioneered by Donoho23. This method performs signal decomposition and reconstruction through the wavelet transform, effectively removing noise by applying a thresholding strategy. The procedure of wavelet threshold denoising consists of the following steps:

-

Step 1

Select an appropriate wavelet function and decomposition level to decompose the input signal.

-

Step 2

During the thresholding process, a suitable threshold function and threshold value must be chosen. Wavelet coefficients below the threshold are considered noise and are set to zero; those above the threshold are retained as components of the useful signal. This strategy enables the effective separation of noise from the underlying signal and the appropriate modification of the wavelet coefficients.

-

Step 3

The denoised signal is reconstructed via the inverse wavelet transform of the thresholder coefficients. The choice of threshold is crucial to the algorithm’s performance, as it determines which wavelet coefficients are preserved or discarded, thereby influencing the denoising outcome. The hard thresholding function retains coefficients whose absolute values are greater than or equal to the threshold, while setting those below to zero. In contrast, the soft thresholding function sets coefficients below the threshold to zero, while also shrinking the coefficients above the threshold. The hard and soft thresholding functions are respectively defined as.

where \(\:{W}_{j,k}\) represents the original wavelet coefficient, \(\:{\widehat{W}}_{j,k}\) denotes the processed coefficient, \(\:\lambda\:\) is the threshold value, sgn(⋅) is the sign function, J indicates the maximum decomposition level with j=1,2,…,J, K is the total number of wavelet coefficients, k=1,2,…, nj, where \(n_{j} = N/2^{{J - j + 1}}\), and N is the length of the signal.

In practical applications, the discontinuity of the hard thresholding function may introduce artificial discontinuities or Gibbs-like phenomena in the denoised signal. The soft thresholding function generally yields smoother and more continuous denoising results. For noisy IMF components, the presence of such artifacts can significantly impact the signal quality and interpretability.

Proposed method

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the overall framework of the proposed denoising method involves decomposing the original electrostatic signal collected from an aero-engine into a set of IMFs using the ICEEMDAN method, followed by screening the signal-dominant components from the IMFs via the ACF algorithm. Useful information within the noise-dominant IMFs is then extracted and recombined with the signal components to reconstruct the denoised signal. The proposed approach consists of three main stages: (1) decomposition of the original signal into IMFs, (2) noise evaluation and IMF screening, and (3) wavelet-based extraction and signal reconstruction.

Decomposition of the original signal into IMFs

To address the nonlinear, non-stationary, and intermittent characteristics of electrostatic signals from the engine gas path, the ICEEMDAN method is employed for its demonstrated efficacy in processing such signals. This step decomposes the original signal into multiple IMFs, effectively separating dominant noise components from useful signal elements into a series of relatively stationary modal components.

Noise evaluation and IMF screening

The IMFs obtained through ICEEMDAN contain both noise and useful signal components. To distinguish between them, an ACF-based optimization criterion is introduced to evaluate noise prevalence and categorize the IMFs into two groups: those that are noise-dominant and those that are signal-dominant.

Wavelet-based extraction and signal reconstruction

The noise-dominant IMFs may still retain portions of useful information. To enhance denoising performance, a secondary extraction step is applied using wavelet soft-thresholding to recover residual signal components from these noise-dominant IMFs. The extracted components are subsequently combined with the signal-dominant IMFs to reconstruct the final denoised electrostatic signal of the aero-engine gas path.

Simulation signal analysis

Simulation signal design

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, a non-stationary electrostatic simulation signal () containing noise is constructed based on the characteristics of electrostatic signals associated with aero-engine gas path faults3,11:

where x1(t) denotes a constant-frequency signal, 2() represents a variable-frequency signal, () is a triangular pulse signal simulating a blade-loss fault (intermittent signal), () indicates the noise-free electrostatic signal, () refers to the noise-added electrostatic signal, () represents Gaussian noise.

The sampling time is set to 2 s; 0 denotes the pulse start time, assigned a random value; indicates the pulse width, i.e., the duration from start to end of the pulse, set to 0.005s; and h represents the pulse amplitude. The function () is configured to simulate four fault occurrences, with the second pulse representing a weak fault signal. When the standard deviation of the Gaussian noise () is set to 1.5, the resulting simulated signals are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Analysis of simulation results

Experimental parameter configuration

Four comparative experiments were conducted with the standard deviation of the Gaussian noise () set to 0.3, 0.7, 1.0, and 1.5, respectively, to evaluate the performance of the algorithms. Each experiment compared four denoising methods: the wavelet threshold denoising method, the EMD-wavelet threshold denoising method, the approach that discards the first two IMF components after ICEEMDAN decomposition, and the proposed method.

Parameter Settings: During the decomposition process, auxiliary noise with a standard deviation of 0.2 was introduced, with a total of 30 realizations. Wavelet threshold denoising was configured with five decomposition levels and the ‘sym8’ wavelet basis. The signal sampling rate was set to 2000 Hz.

The ICEEMDAN parameters used in this study follow recommended values reported in prior literature24,25,26. A realization number of 30 provides a favorable trade-off between decomposition stability and computational cost, as further increasing the number of realizations produced negligible improvement in our preliminary tests. The standard deviation of added noise (0.2) lies within the commonly adopted range of 0.1–0.4 × std(x), ensuring adequate noise-assisted separation without degrading mode purity.

For wavelet thresholding, the sym8 wavelet basis and a 5-level decomposition9,11 were selected because Symlet wavelets are well-suited for preserving transient impulses in low-SNR signals, and the chosen decomposition depth matches the 2000 Hz sampling rate. Experimental observations also showed that moderate variations in these parameters did not significantly alter the denoising outcome, indicating strong robustness.

The sampling rate was selected in accordance with methodologies employed in previous studies on electrostatic monitoring in aero-engine exhaust systems13,23,27. Based on the Nyquist theorem, these studies recommend a sampling rate at least twice the highest frequency component present in the signal. Empirical observations confirm that the fault-related frequency components in such signals are well below 1000 Hz. Hence, a sampling rate of 2000 Hz ensures accurate signal reconstruction without aliasing.

Denoising performance evaluation metrics

To quantitatively assess the denoising performance of the algorithms, three evaluation metrics are employed: the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)28,29, the Mean Squared Error (MSE)30, and the Normalized Cross-Correlation (NCC)31. A higher value of SNR or NCC, coupled with a lower value of MSE, indicates superior denoising performance. These metrics are defined as follows:

where, () denotes the original noise-free signal and () represents the denoised signal.

Results and discussion

Analysis of decomposition, IMF selection, and useful information re-extracted by the proposed method.

As illustrated in Fig. 3, when the standard deviation of the Gaussian noise () is set to 0.3, the noisy signal is decomposed via ICEEMDAN into a total of 11 IMF components and one residue. An autocorrelation function (ACF) analysis was applied to these 11 IMFs and the residue. The computed ACF values for each IMF are presented in Fig. 4. Based on the ACF results, the first four IMFs were identified as noise-dominated. Consequently, the proposed method selects IMFs 5 to 11 and the residue for signal reconstruction.

Following the IMF selection step, signal reconstruction was subsequently conducted. However, an important issue emerged: the IMFs excluded from reconstruction still contained non-negligible fault-related information. As shown in Fig. 5a, the waveform reconstructed using ICEEMDAN + ACF is compared with the raw signal. At the same time, Fig. 5b presents the comparison between the raw signal and the waveform reconstructed using the full proposed pipeline (ICEEMDAN + ACF + WTD). Figure 5c further depicts the reconstruction error of ICEEMDAN + ACF and the additional informative components extracted by the WTD stage.

The WTD procedure effectively retrieves residual fault features located within the local elliptical regions of the reconstruction error signal. Notably, the third and fourth fault events in the raw signal cannot be correctly identified when WTD is omitted; after applying WTD, the corresponding fault signatures are accurately recovered. This enhancement is essential for reliably detecting block–shedding–type faults in aero-engine gas-path monitoring.

Comparison of denoising performance under identical noise levels

Four denoising approaches were compared: wavelet threshold denoising, EMD-based wavelet threshold denoising, the method discarding the first two high-frequency IMFs based on permutation entropy and expert experience after ICEEMDAN decomposition, and the proposed method. The denoised results are shown in Fig. 6. Specifically, Fig. 6a displays the result of wavelet threshold denoising; Fig. 6b shows the outcome of EMD-wavelet threshold denoising; Fig. 6c presents the result obtained by discarding the first two IMFs; and Fig. 6d illustrates the denoised signal using the proposed method. When the original signal exhibited an SNR of 11.48 dB, the SNRs of the denoised signals obtained by the aforementioned methods were 13.58 dB, 18.77 dB, 17.96 dB, and 20.41 dB, respectively.

Comprehensive comparison of the denoising effects achieved by the four methods reveals the following observations. In Fig. 6a, wavelet threshold denoising causes significant signal distortion and yields the lowest signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The magnified view within the red circle shows that the second fault signal in the experiment is almost entirely filtered out. Figure 6b demonstrates that the EMD-wavelet threshold denoising method effectively removes most noise while retaining the fault signal, showing high similarity to the original signal. However, the region marked by the red circle indicates inadequate representation of the weak fault signal, suggesting limited local resolution of this method. As observed in Fig. 6c, the approach that discards the first two components after ICEEMDAN decomposition results in relatively low SNR, with substantial residual noise remaining in the signal. This carries a risk of high false alarm rates. Figure 6d illustrates that the proposed denoising method achieves the highest SNR. Although minor oscillations persist after denoising, most useful detailed information is preserved. Notably, the technique exhibits the best performance in extracting the second weak fault signal, indicating its superior capability in detecting subtle fault features. Compared to the other three methods, the proposed approach provides the highest local resolution in the denoised signal.

Comparison of denoising performance under different noise levels

A comparative evaluation of the four denoising methods was conducted under varying noise levels by adding Gaussian noise with different standard deviations to the simulated signal. The corresponding performance metrics are summarized in Tables 1, 2 and 3. In the tables, denotes the standard deviation of the added Gaussian noise, SNRin represents the SNR of the original noisy signal, and A, B, C, and D refer to the wavelet threshold denoising method, the EMD-wavelet threshold denoising method, the method discarding the first two IMFs after ICEEMDAN decomposition, and the proposed denoising method, respectively.

The results indicate that the proposed method not only improves the SNR but also maintains the mean square error (MSE) at the lowest level among all compared techniques. Furthermore, the normalized cross-correlation (NCC) value of the signal processed by the proposed method reaches the highest level, demonstrating its outstanding capability in recovering the characteristics of the original signal. Therefore, the proposed denoising method outperforms the other three approaches in both denoising effectiveness and overall performance metrics.

Effect of ablation experiment on denoising performance

EMD, ACFs, and WT are widely used signal processing techniques that have proven effective in denoising machinery fault signals18,19,20,32,33. To assess the impact of different strategies on performance enhancement, an ablation study is conducted. Figure 7 presents a comparison of nine distinct signal processing combinations: WT, EMD-IMFs, EMD + WTD, EMD + ACF, EMD + ACF + WTD, ICEEMDAN-IMFs, ICEEMDAN + WTD, ICEEMDAN + ACF, and the proposed method.

Given that the clean signal is known, the performance is evaluated using SNRout, MSE, and NCC, as depicted in Fig. 7. The results indicate that the proposed method consistently achieves higher SNRout and NCC values while exhibiting a lower MSE compared to the other methods, thereby demonstrating superior denoising performance and robustness.

Denoising performance comparisons with state-of-the-art methods

To further validate the effectiveness and advantages of the proposed approach, several state-of-the-art methods reported in recent years are selected for comparative analysis. Table 2 summarizes the denoising results obtained for the simulation signals described in Sect. 3.1.

Table 4 presents a comparison of the proposed method with five contemporary electrostatic signal denoising approaches: EMD-IMF1-IMF2-IMF3, EMD + Energy Values Select, VMD + Kurtosis + Permutation Entropy, TVD, and EMD + ACF.

-

(1)

The EMD-IMF1-IMF2-IMF3 method, introduced in a 2024 study, exhibited commendable denoising performance, with an output SNRout of 17.134 dB, an MSE of 0.024, and an NCC of 0.990. While it effectively selects IMF components for noise reduction, it remains limited under extreme noise conditions.

-

(2)

The EMD + Energy Highest Values method, proposed in 2023, showed significantly poorer performance, yielding an SNRout of 1.775 dB, an MSE of 0.825, and an NCC of 0.579. Despite automatic IMF selection based on energy values, this approach may still retain substantial noise components, leading to suboptimal results.

-

(3)

The VMD + Kurtosis + Permutation Entropy method, proposed in 2023, achieved an SNRout of 3.085 dB, an MSE of 0.610, and an NCC of 0.721. Although it uses kurtosis and permutation entropy for IMF selection, the need to manually specify VMD modes adds complexity and inconsistency under varying signal conditions.

-

(4)

The TVD method, introduced in 2022, showed solid denoising performance with an SNRout of 10.987 dB, an MSE of 0.099, and an NCC of 0.962. It efficiently reduces noise while preserving signal features.

-

(5)

The EMD + ACF method, proposed in 2021, combines EMD with autocorrelation function selection, achieving an SNRout of 15.853 dB, an MSE of 0.032, and an NCC of 0.987.

-

(6)

The proposed method in this study significantly outperforms all others, achieving an SNRout of 20.41 dB, an MSE of 0.011, and an NCC of 0.996. By optimizing signal decomposition and re-extracting useful information, our method minimizes noise while preserving signal features, demonstrating superior denoising capabilities and potential for automatic processing.

The comparative analysis clearly indicates that the proposed method surpasses existing approaches across all performance metrics, particularly in preserving signal quality and suppressing noise. Its ability to perform processing enhances its practicality, providing an effective solution for efficient denoising of electrostatic signals.

Denoising analysis of measured fault electrostatic signals

An experiment on fault conditions was conducted on a micro-turbojet engine test bench to validate the denoising capability of the proposed method for electrostatic signals in the engine gas path. The fault simulation test rig, shown in Fig. 8, primarily consists of a JT20 turbojet engine, an engine control unit, a particle injection device, an electrostatic sensor, a signal conditioning card, a data acquisition card, and a computer. During the experiment, simulated fault particles were injected into the engine exhaust duct via the particle injection device. In contrast, the electrostatic sensor, mounted within the exhaust extension tube, monitored the electrostatic signals in the exhaust flow.

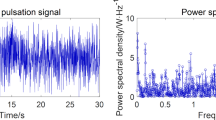

After the micro-turbojet engine was ignited and stabilized, fault particles were injected sequentially in varying quantities across a total of six simulated fault injection experiments. The sampling frequency was set to 2000 Hz, and the sampling duration was 55 s. The acquired raw signals are presented in Fig. 9. It can be observed that the original electrostatic signals contain substantial background noise from the operating environment, with the second fault signal nearly submerged by noise. The collected signals were processed using the proposed method. After the ICEEMDAN decomposition, 19 IMF components and a residue were obtained. Figure 10 displays the first 12 IMF components, which contain the most significant information.

The raw electrostatic signal was denoised using the four aforementioned methods, with the results shown in Fig. 11. The following observations can be made: (1) Although the conventional wavelet threshold denoising method successfully removes a substantial amount of noise, it also filters out the details of small particle electrostatic signals, leading to severe signal distortion and loss of more information related to normal operating conditions. This may hinder the subsequent calculation of the event rate of exhaust particles in fault diagnosis. (2) The EMD-wavelet threshold denoising method effectively reduces a significant amount of noise and allows a rough observation of the fault signal outline. However, its ability to extract weak signals—particularly the second faint fault signal—remains limited, indicating insufficient local resolution. This drawback may compromise the detection of pre-fault anomalies, thereby affecting early engine fault warning capability. (3) After ICEEMDAN decomposition and discarding the first two IMF components, the denoised signal still contains considerable noise, resulting in the poorest denoising performance among the four methods. This is likely to cause high false alarm rates in fault diagnosis. (4) The proposed denoising method not only preserves the fluctuations of normal engine electrostatic signals but also enhances the discernibility of fault signals. As shown in the zoomed-in view, the characteristics of the second weak fault signal are most distinctly represented after processing with the proposed approach.

These results demonstrate that the proposed method effectively retains the characteristic features and trends of the original signal while maximizing noise suppression, yielding a clearer and more accurate signal. The proposed method outperforms the other techniques in extracting informative signal components, showing promising potential for engineering applications.

Additionally, as discussed in Sect. 3.2.3, we evaluated the noise reduction performance of the proposed method by comparing it with several state-of-the-art techniques using real measured data, as illustrated in Fig. 12.

-

(1)

Figure 12a presents the denoised signal obtained by removing the first three IMF components and reconstructing the signal after EMD18. Although this method reduces some noise, noticeable residual noise remains, particularly in the region highlighted by the red circle, which obscures the weak fault signals. While the signal retains some original features, the residual noise negatively impacts the overall denoising quality.

-

(2)

Figure 12b displays the denoised signal obtained by selecting the IMF with the highest energy value after EMD19. This approach results in significant residual noise, rendering fault signal extraction nearly impossible. The high-energy IMF still contains substantial noise, indicating that relying solely on the highest energy IMF is insufficient for effective noise reduction.

-

(3)

Figure 12c shows the denoising result using the VMD + Kurtosis + Permutation Entropy method14. While some fault signals are extracted, the method fails to effectively capture weak fault signals, as highlighted by the red circle. The first fault signal extracted is lower in value compared to other methods, and other fault signals are distorted. Additionally, the method requires manual specification of the VMD modes, which introduces complexity and potential inconsistency.

-

(4)

Figure 12d illustrates the TVD method13, which significantly improves noise reduction while preserving the main signal features. Despite effectively suppressing noise, the technique still struggles with extracting weak fault signals, as indicated in the red-circled region.

-

(5)

Figure 12e illustrates the denoising result of the EMD + ACF method20, which demonstrates effective noise reduction. The red-circled area highlights significant noise suppression, and the method successfully preserves the primary characteristics of the signal. However, the overall noise level remains relatively high.

-

(6)

Figure 12f highlights the performance of the proposed method, which demonstrates superior denoising capabilities compared to the other methods. The plot exhibits significant noise reduction in the red-circled area, yielding a clean signal with well-preserved features. The method strikes an optimal balance between noise suppression and signal preservation. Additionally, its automatic processing feature enhances its practical applicability in real-world scenarios.

The comparative analysis of denoising methods applied to real aero-engine signals demonstrates that the proposed method outperforms the others in terms of both noise reduction and signal preservation. While methods such as TVD and EMD + ACF exhibit good performance, the proposed method achieves the best overall results, making it an exceptionally effective technique for denoising aero-engine signals.

In conclusion, the proposed method effectively captures the normal fluctuations of electrostatic signals in the engine, accurately distinguishing weak fault signals. It preserves the original signal characteristics and trends while eliminating noise, providing smoother and more accurate signals, as evidenced by the elliptical local magnification. This technique offers significant practical engineering value for real-world applications.

Conclusions

In response to the challenges posed by the intermittent, nonlinear, and non-stationary nature of electrostatic monitoring signals in aero-engines, as well as the limitations of conventional denoising methods such as wavelet thresholding and EMD, this paper proposes a denoising approach based on IMF optimized reconstruction and wavelet thresholding for processing low signal-to-noise ratio electrostatic signals from the engine gas path. The proposed method effectively reduces the mean square error, improves the signal-to-noise ratio, and enhances the normalized cross-correlation coefficient, demonstrating superior denoising performance compared to traditional techniques. This study provides both a methodological foundation and an engineering reference for the application of electrostatic monitoring technology in aero-engine fault diagnosis.

Although the proposed denoising framework demonstrates clear advantages, several limitations remain. First, the ICEEMDAN decomposition incurs a higher computational cost compared to simpler filtering approaches, which may limit its applicability at higher sampling rates or under strict real-time requirements. Second, the ACF-based IMF screening relies on low-order statistical correlation and may become suboptimal under extremely severe noise levels or when nonlinear dependencies dominate. Third, the real-engine experiments conducted in this study cover only a limited range of particle types and operating conditions; additional long-duration or high-load experiments would help further improve the method’s generalizability.

Future research will focus on developing adaptive or learning-based IMF selection strategies and exploring unified hybrid frameworks that incorporate more advanced decomposition techniques. Another priority is the implementation of the proposed algorithm on embedded or FPGA-based platforms, enabling real-time monitoring. In addition, more comprehensive validation will be conducted across diverse engine operating conditions, particle characteristics, and extended experimental durations to further assess the robustness and practical applicability of the method in aeroengine health-monitoring scenarios.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wen, Z., Hou, J. & Atkin, J. A. A review of electrostatic monitoring technology: the state of the Art and future research directions. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 94, 1–11 (2017).

Mao, H., Zuo, H. & Wang, H. Electrostatic sensor application for On-Line monitoring of wind turbine Gearboxes. Sensors 18, 3574 (2018).

Zhong, Z. et al. An Estimation method of particle charge based on array electrostatic sensors. Chin. J. Sci. Instrument. 41 (7), 80–90 (2020).

Powrie, H. & Novis, A. Gas path debris monitoring for F-35 joint strike fighter propulsion system PHM. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Aerospace Conference. 314–322 (2006).

Wen, Z. Aero-engine Gas Path Monitoring Technology Based on Electrostatic Induction. (Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2009).

Li, Y. et al. Simulated experiment of aircraft engine gas path debris monitoring technology. Acta Aeronautica Et Astronaut. Sinica. 30 (4), 604–608 (2009).

Jiang, X. et al. The research of aero-engine exhaust electrostatic signal denoising methods. Sci. Technol. Eng. 12 (28), 7298–73027325 (2012).

Fu, Y. & Zuo, H. Recognition for change-point of aero-engine components based on projective transformation. Inf. Technol. J. 13 (2), 347–352 (2014).

Yin, Y., Wen, Z. & Guo, X. A novel method of Gas-Path health assessment based on exhaust electrostatic signal and performance parameters. Measurement 224, 113810 (2024).

Li, M., Jiang, L. & Xiong, X. A novel EMD selecting thresholding method based on multiple iteration for denoising LIDAR signal. Opt. Rev. 22 (3), 477–482 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. Electrostatic signal self-adaptive denoising method combined with CEEMDAN and wavelet threshold. Aerospace 11 (6), 491 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. The electrostatic induction characteristics of SiC/SiC particles in Aero-engine exhaust gases: A simulated experiment and analysis. Aerospace 11 (6), 481 (2024).

Zhong, Z., Zuo, H. & Jiang, H. A nonlinear total variation based denoising method for electrostatic signal of low signal-to-noise ratio. Adv. Mech. Eng. 14 (11), 1–10 (2022).

Yin, Y., Wen, Z. & Zuo, H. Gas-Path fault identification method based on electrostatic signal variational mode decomposition and random Forest. Tuijin Jishu Propuls. Technol. 44, 2207017 (2023).

Li, Y. & Fang, S. A vibration signal decomposition method for time-varying structures using empirical multi-synchro extracting decomposition. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 224, 112107 (2025).

Jeng, Y., Yu, H. & Chen, C. Algorithm fusion for 3D Ground-Penetrating radar imaging with field Examples. Remote Sens. 15 (11), 2886 (2023).

Colominas, M., Schlotthauer, G. & Torres, M. Improved complete ensemble EMD: a suitable tool for biomedical signal processing. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 14, 19–29 (2014).

Tian, Z. et al. Charge pattern detection through electrostatic array sensing. Sens. Actuators Phys. 371, 115295 (2024).

Tian, Z. et al. September. Condition monitoring of pitting evolution using multiple sensing. In: Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Condition Monitoring and Asset Management. 1–12 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Energy entropy analysis of flame signals obtained by an electrostatic sensor array based on EMD denoising method. Zhongnan Daxue Xuebao[J]. 52, 285–293 (2021).

Yang, H., Ning, T. & Zhang, B. An adaptive denoising fault feature extraction method based on ensemble empirical mode decomposition and the correlation coefficient. Adv. Mech. Eng. 9 (4), 1–9 (2017).

Li, L., Wang, F. & Shang, F. Energy spectrum analysis of blast waves based on an improved Hilbert-Huang transform. Shock Waves. 27 (3), 487–494 (2017).

Liu, L., Zhang, J. & Xue, S. Photovoltaic power forecasting: using wavelet threshold denoising combined with VMD. Renew. Energy. 249, 123152 (2025).

Liang, Y., Lin, Y. & Lu, Q. Forecasting gold price using a novel hybrid model with ICEEMDAN and LSTM-CNN-CBAM. Expert Syst. Appl. 206, 117847 (2022).

Zhu, Z. et al. Optimising wellbore annular leakage detection and diagnosis model: A signal feature enhancement and hybrid intelligent optimised LSSVM approach. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 228, 112451 (2025).

Hu, Y., Ouyang, Y., Wang, Z., Yu, H. & Liu, L. Vibration signal denoising method based on CEEMDAN and its application in brake disc unbalance detection. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process. 187, 109972 (2023).

Liu, P., Zuo, H. & Sun, J. The electrostatic sensor applied to the online monitoring experiments of combustor carbon deposition fault in aero-engine. IEEE Sens. J. 14 (3), 686–694 (2014).

Hu, Y. et al. Vibration signal denoising method based on CEEMDAN and its application in brake disc unbalance detection. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 187, 109972 (2023).

Yang, K. et al. Adopting buffer layer for improving Signal-to‐Noise ratio of broadband photomultiplication type organic Photodetectors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35 (9), 2415978 (2025).

Lalawat, R. S. & Bajaj, V. Optimal variational mode decomposition based automatic stress classification system using EEG signals. Appl. Acoust. 231, 110478 (2025).

Zhan, L. et al. Fault size Estimation of rolling bearing based on weak magnetic detection. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 192, 110230 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. Denoising the hob vibration signal using improved complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise and noise quantization strategies. ISA Trans. 131, 715–735 (2022).

Li, Q. New sparse regularization approach for extracting transient impulses from fault vibration signal of rotating machinery. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 209, 111101 (2024).

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U2133202) and the Applied Technology Research Project of Hunan Industry Polytechnic (No. GYKYYJ202202).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, C.Y. and F.L.; methodology, C.Y. and Y.L.; software, C.Y.; validation, C.Y. and Y.L.; formal analysis, F.L.; investigation, C.Y.; re-sources, Y.L.; data curation, C.Y.; visualization, C.Y. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Y.; writing—review and editing, C.Y.; project administration, F.L.; funding acquisition, C.Y. and F.L.; supervision, F.L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, C., Liu, Y. & Lu, F. A denoising method for aeroengine gas path electrostatic signal of low signal-to-noise ratio based on IMFs optimized reconstruction and wavelet threshold. Sci Rep 16, 2762 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32599-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32599-2