Abstract

Hydrogen is a green energy carrier with high energy density. Its production and storage are facing challenges that have made researchers use different materials for its production and storage. Peptides are known to be very effective as the framework of metal cores for making electrocatalysts. Therefore, in this research, a network of nickel and copper with a peptide framework (PCuNi) was created on the surface of the graphite electrode by an electrochemical method, and then the performance of this electrocatalyst was evaluated for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) in an alkaline medium. The amount of peptide and metal cores in the network was optimized to achieve the maximum efficiency of performing the hydrogen evolution reaction, and the structure and morphology of the peptide frameworks were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), mapping detector and X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques. Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), cyclic voltammetry (CV), chronopotentiometry (CE), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) techniques were used to evaluate the performance of the PCuNi electrocatalyst, which indicated the good ability of this network to produce and store hydrogen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world’s primary source of energy has been fossil fuels, including coal, oil, and gas, for more than a century. A report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) shows that in 2020, approximately 84% of the world’s primary energy consumption will be fossil fuels1. The irreversible nature of fossil fuels and their negative effects such as global warming have drawn a lot of attention to green and renewable energy sources2.

Hydrogen is a promising energy carrier with zero carbon emission3 and high energy density of 142 MJ/kg4. This is a renewable energy carrier that can help solve intermittent issues associated with renewable energy sources due to its ability to store large amounts of energy for long periods of time1.

The safety and high cost of hydrogen storage are the most important limiting factors in its use as a fuel. There are different ways to store hydrogen, such as storing in gas cylinders, freezing liquid hydrogen, and electrochemical storage. None of these meets the global need for energy5. Hydrogen is mainly produced from fossil fuels that carbon is still present in its supply chain. Therefore, the most appropriate method for producing high amount of hydrogen with high purity is electrolysis of water whether by photochemistry method or electrochemical method3 Hydrogen production from electrolysis of water and storage for use in fuel cells for electricity generation was proposed by Bockris in 19706. In this method, by decomposition of water on the polarized electrode, hydrogen produce and absorbe on the electrode7. Alkaline water electrolysis has received much attention compared to electrolyzers with proton-exchange electrolytes, due to its many advantages such as power, long life, and low cost due to the use of cost-effective electrodes. However, the overpotential in an electrocatalytic process necessitates the design of a highly active electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction (HER)3. The most important route for efficient hydrogen production is the HER in the presence of electrocatalysts. Today, the most efficient HER electrocatalysts involve noble metals (Pt, Pd, Ru). However, due to the high cost and limited availability of these metals, these electrocatalysts are practically unavailable8.

An appropriate HER catalyst has several basic characteristics:

-

1.

A large number of active sites with an optimum electron density for bonding with the hydrogen atom in such a way that there is no barrier to absorption or desorption.

-

2.

Low charge transfer resistance on the electrode.

-

3.

Stability in the electrolyte.

Platinum (Pt), titanium (Ti), palladium (Pd), vanadium (V), ruthenium (Ru), iridium (Ir), and their oxides and hydroxides are the current state-of-the-art electrocatalysts for the reaction with hydrogen but their high cost and low abundance prevent them from being used on a global scale. Therefore, much attention has been paid to the use of carbon or non-noble metals, abundant in the earth with high activity and stability3,7. Accordingly, recent studies have used non-precious metal catalysts including Ni, Mo, Co, W, Fe, Cu, Mn-based electrocatalysts, metal oxide, metal phosphide9, metal nitride, metal carbide, metal boride, metal chalcogenide9/dichalcogenide-based catalysts, and metal-free catalysts. Among them, Ni-based electrocatalysts are of great interest (overpotentials: 12–328 mV at 10 mA/cm2) because Ni has excellent corrosion resistance in alkaline water8.

On the one hand, in the past decade, carbon-based materials have emerged as strong candidates for the electrochemical storage of hydrogen. Low atomic mass compared to metals, low cost, high surface area, and high abundance are some of the key advantages that make carbon a suitable media for the electrochemical storage of hydrogen6.

On the other hand, the design of catalysts based on biomolecules and affordable metals is of great interest10. Likewise, metal alloys have received a great deal of attention from researchers due to their special physical and chemical properties11. Compared to single metal catalysts, bimetallic catalysts have more catalytic activity due to synergistic effects and these synergistic effects are because of the geometric and electron effects of the alloy. The presence of particles of one metal along with particles of another metal can improve the size, surface composition, and morphology of the catalyst12,13.

It should be noted, that only when the charge transfer rate and hydrogen permeation are high enough, the alloy will be capable of high discharge that the charge transfer process is regulated by changing the current density. Generally, HRD (high rate dischargeability) performance, which is attributable to the properties of electrochemical kinetics, is influenced by two factors rate of charge transfer and hydrogen penetration14. Today, most published studies are focused on the design and synthesis of high-performance electrocatalysts for HER under alkaline conditions. This is because alkaline water electrolysis is the most commonly used route in industry, and alkaline HER is also a key step in the chlor-alkali process15. Since electrocatalytic performance depends very much on the composition and structure of the electrocatalyst, so far researchers have tried to, in addition to selecting an alloy or composite with the highest electrocatalytic performance, also design the electrode structure in such a way that it has the largest active surface area for the HER reaction, for example, using metal nanospheres, carbon nanotubes, or creating nanostructured coatings on nickel foam and mesh have been efforts in this direction. Also, choosing or designing lattice structures greatly helps in adsorbing hydrogen for the HER reaction9. Some of the electrodes with the highest discharge capacity in alkaline media have been reported in Table 1.

Various methods have been proposed for the design and fabrication of binary alloys. One of the most effective methods is the use of biological ligands and templates such as DNA, dendrimer, bacteria, proteins and peptides12,13,23. Meanwhile, the use of peptides as a template for metal alloys has received much attention from researchers, because metal alloys based on peptides can be made in aqueous media and at room temperature and also can be manufactured with very easy methods and peptides can change their physical and chemical properties by controlling the atomic structure of metal alloys12. Recently, Wen Wu et al. made peptide templated AuPt alloyed nanoparticles as electrocatalysts for HER and ORR reactions13, also this group made peptide Flg3 templated AuPd nanoparticles12 and peptide A4 based AuAg nanoparticles24 as electrocatalyst for ORR reaction. Zhuo Zong et al. used peptide-templated Au@Pd for HER and ORR reactions23.

In this work, we reported a very easy method to fabricate triptorelin templated NiCu networks and then evaluate the performance of this electrocatalyst for the HER reaction. For this purpose, in the first step, we synthesized the triptorelin peptide using the standard Fmoc strategy. Then, we electrochemically formed a bimetallic peptide framework (PCuNi) on the surface of a graphite electrode. In this step, the structure of the synthesized PCuNi framework was optimized in an alkaline medium and analyzed by microscopic and spectroscopic methods. Finally, the performance of this electrocatalyst in terms of electrocatalytic HER was evaluated using electrochemical techniques. A summary of the study can be seen in Fig. 1.

Experimental

Materials

All the utilized chemicals were analytical grade and used without any prior purification. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), nickel (II) chloride hexahydrate (NiCl2.6H2O), copper (II) chloride dehydrate (CuCl2.2H2O), cobalt (II) chloride hexahydrate (CoCl2.6H2O), acetonitrile, N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), Dimethylformamide (DMF), Dichloromethane (DCM), 2-(1 H-Benzotriazole-1-yl)−1,1,3,3-tetramethylaminium tetrafluoroborate (TBTU), Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), acetic anhydride and amino acids of tryptophan (Trp), serine (Ser), tyrosine (Tyr), and histidine (His) all were purchased from Merck chemical companies. In all solutions were used of deionization water. Also, commercial graphite, epoxy resin, and hardener were used to make the working electrode.

Instruments

An electrochemical cell with two and three-electrode configuration was used. A bar graphite rod and modified graphite (0.62 or 0.05 cm2) rod were used as the counter and the working electrode, respectively. Ag/AgCl- saturated KCl (3.5 M) electrode was used as the reference electrode. Studies were accomplished by an electrochemical system comprising EG&G model 273 A potentiostat/galvanostat. The system was run by a PC through M270 and M398 commercial software via a GPIB interface. The surface morphology of the working electrode was investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) model SIGMA VP (ZEISS company of Germany) also the X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was made by Oxford Instrument company of England. X-ray diffraction (XRD) study was performed by X-ray diffractometer model X’ Pert Pro (Panalytical company). All experiments were performed at room temperature.

Triptroline peptide synthesis

The synthesis procedure involved the utilization of rink amide resin (1.0 mmol/g) employing the standard fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) strategy (Fig. 2). Initially, Fmoc-Gly-OH (10 mmol) was affixed to the rink amide resin (5.000 g) with DIPEA (6.85 mL, 40 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (50 mL) at room temperature for 1 h. After filtration, the remaining rink amide groups were capped with DMF/acetic anhydride/DIPEA (25:5:1, 120 mL) for 30 min. The resin was then filtered and washed thoroughly with DCM (1 × 20 mL), followed by washes with DMF (4 × 20 mL). The resin-bound Fmoc-amino acid was treated with 25% piperidine in DMF (65 mL) for 30 min, followed by additional DMF washes (3 × 20 mL). A solution of Fmoc-pro-OH (7.5 mmol), TBTU (2.407 g, 7.5 mmol), DIPEA (4.28 mL, 25 mmol) in 30 mL DMF was then introduced to the resin-bound free amine, which was shaken for 1 h at room temperature. Post-coupling, the resin underwent thorough washing with DMF (4 × 20 mL). The coupling procedure was repeated for other amino acids in their sequences. The Kaiser Test confirmed the presence or absence of free primary amino groups, and Fmoc-determination was carried out using UV spectroscopy. After completing couplings, the coupled resin was washed with DMF (4 × 20 mL). Final deprotection used TFA (95%) and reagent K (TFA/TIS/Water 95:2.5:2.5). Excess TFA was removed under reduced pressure, and the desired peptide was precipitated in diisopropyl ether. The white precipitates were buffered in water/acetonitrile (50/50), purified using reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (> 99% purity) (Fig. S1), and measured for molecular weight using an atomic mass spectrometer (Fig. S2).

HPLC and mass spectrometry of triptorelin

The purification of the peptide was done using preparative HPLC with column (ODS-C18, 120 × 20 mm, Eurospher 100, 7 μm) and UV detector (λ = 210 nm). The elution solvent was ACN/H2O. The structure of triptorelin was approved using MS (ESI). LC-MS analyses were conducted using an Agilent Triple Quadrupole LC/MS 6410 diode array detector, ALS, TCC, Bin pump, and Degasser from the 1200 series. The MS instrument was operated with the following settings: drying gas (nitrogen) at 300 °C, source voltage at 3.5 kV, nebulizing gas pressure at 50 PSI, and ionization mode in electrospray. Product ions were scanned and monitored, as illustrated in Fig. S1. The mass spectrum of triptorelin for precursor ion m/z 656.9([M + 2 H]2+/2). The major fragments were m/z 656.9 and 1311.5.

Preparation of electrode

The graphite rods were used as the working electrodes. Firstly, they were placed in a 3 M HNO3 solution for about 24 h. Secondly, they were immersed in 6 M NaOH solution for about 30 min. Nextly, they were washed with deionization water. Finally, the graphite rods were coated with the solution of resin and hardener (10:1), and after drying; the surface of the electrodes was mechanically polished, washed, and dried.

To prepare the modified electrodes, a certain amount of peptide was weighed at each step (0.2, 0.5, 1, and 2 mg) and dissolved in 100 µl of the solvent including acetonitrile and water in a ratio of 50/50. This solution was then placed on the electrode surface and dried at ambient temperature. Formation of metals such as nickel, copper, and cobalt on the surface of graphite or modified graphite was done by placing electrodes in 1 M chloride salt solutions of each metal for specified periods (30 min, 60 min, 120 min) and then applying the potential in the negative range. It was performed by cyclic voltammetry technique (a cycle with a scan rate of 100 mV/s in the range 0 to −1 V) with the aim of reducing metal ions adsorbed by graphite or peptide structure. The prepared electrodes were then washed with deionized water and evaluated in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide solution by cyclic voltammetry, differential pulse voltammetry, chronopotentiometry, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy techniques. Cyclic voltammetry, differential pulse voltammetry, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy tests were performed with a three-electrode system and chronopotentiometry tests were performed with a two-electrode system.

Result and discussion

In this study, first, peptide-metal frameworks-modified graphite electrodes were synthesized and evaluated using microscopic and spectroscopic techniques such as SEM, EDS and XRD. Then, the electrochemical applications of this modified electrode were investigated and it was used as electrocatalysts for electrocatalytic HER. The performance of this electrocatalyst was evaluated using various electrochemical techniques such as DPV, CV, CE and EIS.

Electrode surface characterization

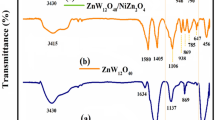

SEM images of graphite electrode, modified graphite electrode with peptide (GP), and modified graphite electrode with peptide, Cu and Ni (GPCuNi) are shown in Fig. 3 and their EDS spectrum and the XRD pattern are shown in Fig. 4. Comparing Fig. 3 (a) and (b), the placement of peptide particles on graphite is quite obvious also, Fig. 3 (c) and (d) clearly show the network of peptides, Cu and Ni.

In addition to the synergistic effect that exists between peptides, copper, and nickel, the structure created on the electrode surface has a great impact on the performance of the electrode (as mentioned earlier, the electrode structure plays a vital role in the hydrogen reduction reaction). When the graphite electrode with a peptide coating is placed in the metal salt solution, metal ions form a complex with the peptide and forms a MOF or in other words MPF (metal peptide framework). After applying a negative potential to this electrode, the copper and nickel in the peptide structure are reduced and remain in the same place as the metal atoms and maintain their network and structure. Likewise, metal atoms can maintain their strength through the force of hydrogen bonding. This regular and stable structure is an effective factor in the performance of the electrode.

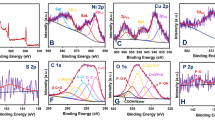

Comparing the EDS spectrum in Fig. 4 (a), (b) and (c), it can be seen that Ni and Cu with weight percentages of 20 and 25.9, respectively, are located in the structure of the GPCuNi electrode. It should be noted, the XRD patterns of these electrodes show different crystalline structures. The overall XRD pattern of graphite is preserved after modification by peptide (GP) and then by Cu and Ni (GPCuNi), but the decrease and increase in intensity of some peaks can be seen in Fig. 4 (e, f). The XRD results show that all samples exhibit the characteristic graphite peaks at 2θ ≈ 26° (002), 44°(101) and 54–55° (004), confirming the retention of the layered hexagonal graphite structure. After peptide modification, all reflections become more intense, suggesting improved stacking order or preferential alignment. In the peptide/Cu/Ni modified electrode, these peaks still maintained their intensity and sharpness, confirming the successful deposition and crystallization of metallic Cu and Ni species on the peptide-functionalized graphite. The persistence of the (004) reflection across all samples demonstrates that the intrinsic layered structure of graphite is preserved throughout the modification process.

Cyclic voltammetry (CV)

Figure 5 shows the cyclic voltammetric curves of the graphite electrode and the modified graphite electrodes in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide solution. To make a copper-modified graphite electrode (GCu), the graphite electrode was immersed in a solution of 1 M CuCl2.2H2O for 30 min and then cycled in this solution (1 cycle at the range of 0 to −1 with a scan rate of 100 mV/s). To make a peptide-modified graphite electrode (GP), 0.2 mg of the peptide was dissolved in a mixture of acetonitrile and water and placed on the surface of the electrode, and used after drying. Finally, to make a graphite electrode modified with peptide and copper (GPCu), after drying the solution containing 0.2 mg of the peptide on the graphite surface, the electrode was placed in a solution of 1 M CuCl2.2H2O for 30 min and then in the potential range of 0 to −1 was cycled. As can be seen in Fig. 5, the anodic current produced by the GPCu electrode is higher than other electrodes, which indicates the high electrocatalytic performance of this electrode due to the synergistic effect of the peptide and copper.

Usually, three methods are used for the electrochemical storage of hydrogen: 1- Galvanostatic charge and discharge method, 2- Cyclic voltammetry, chronoamperometry, and linear voltammetry methods 3- Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy25. In this research the first method was used. Figure 6 shows the discharge curves of the electrodes after charging in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide solution with a current of −20 mA/cm2 for 200 s. As shown in the figure, the GPCu electrode has a higher ability to hold charge than the GP and GCu electrodes. During the charging phase, water molecules are reduced on the electrode surface and hydrogen is produced (since all peptides form hydrogen bonds with water, water is easily absorbed on the electrode surface). The metalized peptide on the electrode surface not only acts as an electrocatalyst for the water reduction reaction (HER), but also provides a structure in which the hydrogen produced is stored23. The HER mechanism has three stages: Volmer, Tafel and Heyrovsky reactions. Two steps basically guide the electrochemical storage of hydrogen, the first being adsorption on the outer surface and the second penetrating into the sample mass. The mechanism that drives the electrochemical adsorption of hydrogen is a three-step process that involves the Volmer, Tafel, and Heyrovsky reactions. The initial step is the charge transfer reaction that occurs at the electrode/electrolyte interface, as shown in the following equation25.

This equation shows the Volmer reaction where water reduction to hydroxyl ions occurs and even adsorption of hydrogen atoms occurs within the electrode surface. Atoms adsorbed by the host material lead to the formation of subsurface hydrogen (Hss).

These subsurface hydrogen atoms penetrate into the mass as Habs:

In addition, the Tafel reaction occurs where adsorbed hydrogen atoms join to convert to hydrogen gas.

The Herovsky reaction occurs where hydrogen atoms form a hydrogen molecule by separating a hydrogen atom from a water molecule25.

Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV)

Differential pulse voltammetry technique was used to study the electrochemical performance of triptorelin peptide. Figure 6 is a comparison between the performance of a graphite electrode and a GP electrode. The peak observed in potential 0.494 V is related to water oxidation and the peak observed in potential 0.912 V is related to oxygen oxidation, both of them are seen in bare graphite, but the current produced by the GP electrode is higher. A peak at potential 1.28 V can also be seen, possibly due to the oxidation of one of the electrochemically active sites of the triptorelin peptide. Triptorelin is composed of several amino acids, among them, and based on literature, only the amino acids tryptophan, tyrosine, histidine, and serine are electrochemically active26.

Optimization of the electrode structure

To improve electrocatalytic performance of GPCu electrode, its structure was optimized in several steps. In the first step, the amount of peptide on the electrode surface was optimized. For this purpose, 4 solutions of 0.2, 0.5, 1, and 2 mg of peptide were prepared and placed on the electrodes. Then these electrodes were placed in the copper solution for 30 min, and then cycled in the negative potential range and finally, the performance of these electrodes was evaluated. According to Fig. 7, the best performance of the electrode made with 0.2 mg peptide with a discharge time of about 6000 s. According to Fig. 7, by decreasing the amount of peptide on the electrode surface, its efficiency improved. The reduction of the electrode performance with increasing the amount of peptide can be due to the increase of the resistance of the electrode surface. In another experiment, the duration of the GP electrode in copper solution was optimized. For this purpose, a solution containing 0.2 mg of the peptide was placed on the graphite electrodes and after drying, they were immersed in a solution of 1 M CuCl2.2H2O for 30 min, 60 min, and 120 min then cycled in the negative potential range and finally the performance of these electrodes was evaluated. According to Fig. 8, the best time to adsorb copper ions into the peptide structure of the electrode surface and generate a high-performance electrocatalyst was 60 min.

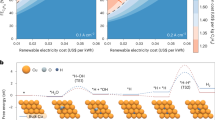

According to the literature, the use of binary or even ternary mixtures of transition metals to make electrocatalysts increases their performance due to the synergistic effect27. Therefore, at this stage, the peptide-coated electrode, instead of being placed in pure copper solution, was placed for 60 min, in a solution containing a mixture of 1 M of copper and cobalt ions and also a mixture of 1 M of copper and nickel ions. GPCo and GPNi electrodes were also fabricated. Figure 9 is a comparison of the performance of these electrodes. As shown in this figure, the graphite electrode modified with peptide, copper, and nickel has a very high performance and its discharge time is about 10,600 s and the hydrogen storage capacity (Based on the formula of: (It) discharge/(It)charge m Electroactive material) was obtained of 441.6 mAh/g. The reason for this high performance is the synergistic effects of the electrode components. To ensure the great importance of the presence of peptide in the electrode, the performance of graphite electrodes modified with nickel, cobalt, and copper metals was also evaluated (Fig. 10). To make each of these electrodes, graphite was immersed in a solution of nickel (II) chloride hexahydrate, copper (II) chloride dehydrate or cobalt (II) chloride hexahydrate for 30 min, and then was cycled in the negative potential range and after washing, they were charged and discharged in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide solution. Examining the data from Figs. 9 and 10, it is clear that the presence of peptide in the structure of the electrode is very effective in its performance. In the absence of peptide, maximum efficiency for water reduction and hydrogen storage was not observed.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

Figure 11(a) shows the Nyquist diagrams of the G, GP and GPCuNi electrodes in NaOH 0.1 mol/L at OCP potential and its equivalent circuit. According to Fig. 11, all the results of cyclic voltammetry and chronopotentiometry techniques are confirmed by impedance techniques. As can be seen in Fig. 11(a), the semicircular diameter of the curve for the GPCuNi electrode is much lower than that of the G and GP electrodes, indicating a lower charge transfer resistance in the modified electrode. In the equivalent circuit, elements 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 are equivalent to double layer capacitor, solution and electrode resistance, charge transfer resistance, electrode surface coating capacitor, and electrode surface coating resistance, respectively.

Figure 11(b) shows the Nyquist diagrams of the GPCuNi electrode in NaOH 0.1 mol/L at −1.49 V Ag/AgCl dc potential after 20, 50, and 100 s of charging. At high frequencies, electrode and electrolyte resistance are seen. As shown in Fig. 11(b), with increasing charging time, the resistance of the electrode increases due to the storage of more hydrogen in the electrode surface cavities, which is another sign of the electrode’s ability to store hydrogen.

Conclusions

A green and effective electrocatalyst for HER based on triptorelin peptide, Cu, and Ni was created by electrochemical method on the surface of graphite electrode. This electrode was characterized using DPV, CV, CE, and EIS techniques. The amount of hydrogen storage was checked by the galvanostatic charge/discharge method. It was found that in addition to the synergistic effect between triptorelin peptide, Cu, and Ni, the network created on the graphite electrode surface (metal peptide framework) also has a great impact on the performance of the electrode. The metalized triptorelin peptide on the electrode surface not only acts as an electrocatalyst for HER, but also provides a network in which the hydrogen produced is stored. The discharge capacity was obtained of 441.6 mAh/g.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

References

Ma, N., Zhao, W., Wang, W., Li, X. & Zhou, H. Large scale of green hydrogen storage: opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 50, 379–396 (2024).

Rasul, M. G., Hazrat, M. A., Sattar, M. A., Jahirul, M. I. & Shearer, M. J. The future of hydrogen: challenges on production, storage and applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 272, 116326 (2022).

Huang, D. et al. Fabrication of Cobalt porphyrin. Electrochemically reduced graphene oxide hybrid films for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution in aqueous solution. Langmuir 30, 6990–6998 (2014).

Karayilan, M. et al. Catalytic metallopolymers from [2Fe-2S] clusters: artificial metalloenzymes for hydrogen production. Angew Chemie. 131, 7617–7630 (2019).

Fernandez, P. S., Castro, E. B., Real, S. G. & Martins, M. E. Electrochemical behaviour of single walled carbon nanotubes–Hydrogen storage and hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 34, 8115–8126 (2009).

Oberoi, A. S., Nijhawan, P. & Singh, P. A novel electrochemical hydrogen storage-Based proton battery for renewable energy storage. Energies 12, 1–15 (2018).

Honarpazhouh, Y., Astaraei, F. R., Naderi, H. R. & Tavakoli, O. Electrochemical hydrogen storage in Pd-coated porous silicon/graphene oxide. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 41, 12175–12182 (2016).

Kojima, Y., Miyata, Y. & Nakanishi, H. MmNi5-based hydrogen storage alloy as an electrocatalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 87, 450–456 (2024).

Anantharaj, S. et al. Strategies and perspectives to catch the missing pieces in energy-efficient hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline media. Angew Chemie Int. Ed. 60, 18981–19006 (2021).

Mitra, S. et al. De Novo design of a self-assembled artificial copper peptide that activates and reduces peroxide. ACS Catal. 11, 10267–10278 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. A critical review of research progress for metal alloy materials in hydrogen evolution and oxygen evolution reaction. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30, 11302–11320 (2023).

Li, D., Tang, Z., Chen, S., Tian, Y. & Wang, X. Peptide-FlgA3‐based gold palladium bimetallic nanoparticles that catalyze the oxygen reduction reaction in alkaline solution. ChemCatChem 9, 2980–2987 (2017).

Wu, W. et al. Peptide templated AuPt alloyed nanoparticles as highly efficient bi-functional electrocatalysts for both oxygen reduction reaction and hydrogen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta. 260, 168–176 (2018).

Wang, W. et al. A novel AB4-type RE–Mg–Ni–Al-based hydrogen storage alloy with high power for nickel-metal hydride batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 317, 211–220 (2019).

Ding, X. et al. Dynamic restructuring of nickel sulfides for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 15, 5336 (2024).

Shi, W., Zhang, X. & Che, G. Hydrothermal synthesis and electrochemical hydrogen storage performance of porous Hollow NiSe nanospheres. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 38, 7037–7045 (2013).

Darband, G. B., Aliofkhazraei, M. & Rouhaghdam, A. S. Three-dimensional porous Ni-CNT composite nanocones as high performance electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Electroanal. Chem. 829, 194–207 (2018).

Zhao, X., Zhou, J., Shen, X., Yang, M. & Ma, L. Structure and electrochemical hydrogen storage properties of A2B-type Ti–Zr–Ni alloys. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 37, 5050–5055 (2012).

Chen, W. et al. Significantly improved electrochemical hydrogen storage properties of magnesium nickel hydride modified with nano-nickel. J. Power Sources. 280, 132–140 (2015).

Zeng, L. et al. One-step synthesis of Fe-Ni hydroxide nanosheets derived from bimetallic foam for efficient electrocatalytic oxygen evolution and overall water splitting. Chin. Chem. Lett. 29, 1875–1878 (2018).

Bai, J., Sun, Q., Wang, Z. & Zhao, C. Electrodeposition of Cobalt nickel hydroxide composite as a high-efficiency catalyst for hydrogen evolution reactions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164, H587 (2017).

Babar, P. et al. Cobalt iron hydroxide as a precious metal-free bifunctional electrocatalyst for efficient overall water splitting. Small 14, 1702568 (2018).

Zong, Z. et al. Peptide templated Au@ Pd core-shell structures as efficient bi-functional electrocatalysts for both oxygen reduction and hydrogen evolution reactions. J. Catal. 361, 168–176 (2018).

Wang, Q. et al. Peptide A4 based AuAg alloyed nanoparticle networks for electrocatalytic reduction of oxygen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 42, 11295–11303 (2017).

Kaur, M. & Pal, K. Review on hydrogen storage materials and methods from an electrochemical viewpoint. J. Energy Storage. 23, 234–249 (2019).

Sęk, S., Vacek, J. & Dorčák, V. Electrochemistry of peptides. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 14, 166–172 (2019).

Rostami, T., Jafarian, M., Miandari, S., Mahjani, M. G. & Gobal, F. Synergistic effect of Cobalt and copper on a nickel-based modified graphite electrode during methanol electro-oxidation in NaOH solution. Chin. J. Catal. 36, 1867–1874 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GHS.F: The corresponding author of current study, Main executor of the project, Substantial contributions to the conception, Design of the work, Have drafted the work, Prepared figures, Writing - Review & Editing, Analysis and interpretation of data and wrote the main manuscript. M.J: Writing - Review & Editing, Analysis and interpretation of data and wrote the main manuscript. S.R: Writing - Review & Editing, Analysis and interpretation of data and wrote the main manuscript. H.AMMA: Writing - Review & Editing, Analysis and interpretation of data and wrote the main manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferdowsi, G.S., Jafarian, M., Ramezanpour, S. et al. Design and synthesis of graphite/Ni/Cu/triptorelin peptide electrocatalyst for hydrogen production and storage. Sci Rep 16, 2779 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32616-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32616-4