Abstract

Smoking, a risk factor for periodontitis and peri-implantitis, is associated with shifts in the oral microbiome (OM) composition. Although smoking habits are almost always established before adulthood, data on effects of smoking on the OM in adolescents is rare. The aim of this study was to investigate the early impact of smoking on the OM composition in pupils. The adolescent cohort, aged 14–20, comprised 98 smokers and 98 non-smokers matched for several physiological co-variates. Buccal swabs were analysed for OM composition using high-throughput sequencing of the full-length 16 S rRNA gene targeting species-level resolution. Parameters of bacterial diversity and abundance of individual bacterial taxa were related to information on smoking. The microbiome dataset contained 733 species-level taxa. Streptococcus, Rothia, and Haemophilus dominated both groups, smokers and non-smokers. Smoking exerted a discernible influence on the overall microbial composition as measured by weighted UniFrac distances. The number of species-level bacterial taxa was significantly higher in individual smokers compared to non-smokers. Furthermore, several taxa, including known pathogens, exhibited significant differences in abundance between the two groups. The genera Veillonella, and Actinomyces, as well as and multiple Actinomyces species, Dialister invisus, Atopobium parvulum, Streptococcus mutans and Prevotella melaninogenica were significantly more abundant in smokers. Our findings indicated an early onset of smoking-related changes already in the oral microbiome of adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The human oral microbiome contains over 700 known species of bacteria1,2.Metagenomic data also suggest that several thousand additional species remain largely undescribed3,4. A single individual oral sample typically contains a fraction of this spectrum, usually between 50 and 200 different bacterial species5,6. These bacteria fulfill a variety of functions and many of them are critical for maintaining oral health7. A shift in the oral microbiome, known as dysbiosis, is a critical step in the development of oral diseases such as periodontitis and dental caries8,9,10,11. Smoking is associated with shifts in the composition of the oral microbiome12,13,14,15 and can contribute to the development and progression of periodontitis16,17,18 and oral peri-implantitis19,20,21. Studies in adults show that smoking changes several conditions for bacterial growth in the oral cavity22. These alterations include complex effects on the immune system resulting in suppressed immune cell function23,24 but increased pro-inflammatory mediators25,26. Additionally, the oxygen tension in gingival pockets, which reflects the partial pressure of oxygen available for microbial metabolism, and saliva pH are reduced in smokers27,28,29. Cigarettes were also shown to directly contain bacteria, including several taxa with pathogenic potential, and might therefore contribute to the accumulation of these taxa in the oral microbiome of smokers30. These smoking-related effects seem to favour a pathogenic shift in the oral microbiome which has been observed for adult smokers so far12,15,22,31.

While most studies on the effects of smoking are conducted in adult long-term smokers, smoking habits are mostly already established before the age of 1832. In 2022, approximately 16% of German 14- to 17-year-old adolescents and 40.8% of 18- to 24-year-old adolescents classified as current smokers33,34. While it appears likely that the first smoking-related changes of the oral microbiome will develop with the beginning of smoking the oral microbiome of adolescent smokers is severely understudied. We conducted a comprehensive assessment of oral microbiome community compositions and bacterial abundances in 196 pupils, including 98 smokers and 98 matched non-smokers to improve the understanding of the impact of smoking on the oral microbiome in adolescents.

Materials and methods

Study population

This study was carried out in the framework of the longitudinal Transmission Analytic COVID-19 (TRAC-19) study, which analysed infections, behavioural patterns and vaccination hesitancy during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in two schools within a German city35. Participation in the study was voluntary and required the written consent of the participants and the legal guardians of minors. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hannover Medical School (Ethical Vote No. 9085_BO_S_2020) and is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki35.

Samples for this sub-study on the oral microbiome were collected on-site during school hours from June to December 2020 from secondary-school pupils. All included participants were between 14 and 20 years of age, indicated that they brushed their teeth at least twice a day and did not take regular medication except for hormonal contraceptives or either paracetamol and/or ibuprofen and/or lactase on less than one occasion a week. Participants who had taken antibiotics were excluded from the study. All participants reported good oral hygiene practices and the absence of oral health issues.

A total of 98 samples were collected from current smokers. These smoking participants were matched one-to-one with similar participants who reported that they had never smoked, resulting in a combined dataset consisting of 196 participants. The following criteria were taken into account for matching: sex, age, height, BMI, and use of hormonal contraceptives. Successfully balanced matching was verified as detailed in Table 1. Independent t-test, Chi-square and Fisher exact test were calculated with the R package stats (version 4.1.0).

Data and sample collection

To analyse the oral microbiome, samples were taken from the buccal mucosa of all participants. This was done using sterile and DNA-free cotton swabs (Sarstedt, Nuembrecht, Germany), which were wiped three times for approximately ten seconds on the inside of each cheek. Afterwards, each cotton swab was transferred to 1 ml DNA/RNA shield (Zymo Research, Freiburg, Germany), and stored at − 80 °C. Health data of the participants were collected with a questionnaire (see Supplementary Table 1). The following parameters were queried: age, sex, weight, height, oral health status, tooth brushing frequency, known chronic diseases, and type and frequency of regular medication intake including hormonal contraceptives. In addition, several questions defined the smoking behaviour. Students self-reported whether they had ever smoked before and if so, whether they consumed conventional cigarettes, electronic cigarettes or both. Smoking pupils classified their smoking frequency with one of six categories from “less than once/month” to “more than 20 cigarettes/day”. The majority of smoking pupils consumed conventional cigarettes (81 out of 98), but also e-cigarettes were frequently used (48 out of 98). Bacterial communities of smokers using only conventional, only e-cigarettes, or a combination showed no significant differences (see Supplementary Fig. 3). Therefore, we combined all smokers of conventional and e-cigarettes into the single category “smokers”.

Oral microbiota analyses

Sample preparation and SMRT full-length 16 S rDNA amplicon sequencing

DNA was extracted under DNA-free conditions using a combination of mechanical disruption and column-based DNA isolation (see Supplementary Methods). Bacterial 16 S rDNA genes were amplified using the bacteria-specific primer pair 27 F (AGRGTTYGATYMTGGCTCAG) and 1492R (RGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT), sequenced using PacBio Sequel technology, and analysed with an in-house pipeline (see Supplementary Methods).

Bacterial spike-ins

To allow for absolute quantification of bacterial cells of oral microbiota species, and to test for sample-specific variations in DNA extraction efficiency for bacterial species with different cell wall characteristics, 2.8 µl ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control I (Zymo Research, Freiburg, Germany) were added to each sample as well as to every empty control. This spike-in control contains specified cell numbers of the bacterial species Imtechella halotolerans and Allobacillus halotolerans, which are not members of the human microbiome.

Negative controls

To control for potential laboratory or chemical contaminants, empty samples consisting of clean cotton swabs in 1 ml DNA/RNA shield were processed in parallel during all steps of sample preparation, from DNA extraction to library preparation and sequencing (see Supplementary Table 2 for a list of potential contaminants).

Microbiota statistics

Alpha-diversity metrics (number of observed species-level taxa, Shannon index, evenness) were calculated for comparison of intra-sample diversity. To allow inter-sample comparability for these metrics, all samples were subsampled to 3,040 sequence reads. One sample and its corresponding match were excluded from this analysis (97 pairs remained) because it contained only 1,316 sequences. The observed number of species-level taxa and the Shannon index were determined with the functions tax_glom and estimate_richness of the R package phyloseq (version 1.36.0)36. Based on this, evenness was calculated as follows: Shannon index/loge(number of observed species-level taxa). Descriptive statistics, tests for homogeneity of variance and normal distribution, independent t-test, and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated with the R packages car (version 3.1.1), stats (version 4.1.0) and lsr (version 0.5.2).

The sample-specific extraction efficiency index was calculated based on the spike-in species ratio (see Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Fig. 1). All PERMANOVA and DESeq2 analyses were performed while controlling for this sample-specific technical variable.

Analyses of beta-diversity were based on weighted UniFrac distances37. The underlying phylogenetic tree was inferred on the basis of an infernal 1.1.2 alignment38 using the double-precision version of FastTree 239. Principal Coordinates Analyses (PCoA) as a multivariate, unconstrained ordination method were calculated using the R package phyloseq (version 1.36.0). Significance of overall group differences were assessed using PERMANOVA as implemented in the adonis2 function of the R package vegan (version 2.6.4). The following possible non-technical co-variates were included in the PERMANOVA calculations as indicated: age in years, BMI, sex, hormonal contraceptives and percentage of Imtechella reads as proxy for the number of bacterial cells in the original sample. Differences in averages of pairwise weighted UniFrac distances between all samples of selected groups were calculated as independent t-test or ANOVA with R package stats (version 4.1.0). Association of individual taxa with the smoking behaviour (smoking/non-smoking) were tested with DESeq2 controlling for sample-specific extraction efficiency index40.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

A group of 98 smokers (age 14.2–20.3 years) and 98 matched non-smokers (age 14.2–19.4 years) was analysed (Table 1). Pupils in each study group had a median age of 17 years, normal weight (median BMI of 21 kg/m2 in both), and used hormonal contraceptives in 13 cases. Although sexes were balanced between smokers and non-smokers, more study participants were female than male. Four participants, all from the group of smokers, reported use of either paracetamol and/or ibuprofen and/or lactase on less than one occasion a week.

Smoking frequencies that were reported by the pupils covered five categories ranging from “less than once/month” (category 1) to “every day” (category 5) (Supplementary Fig. 2). No participant met the criterion for heavy smoking (more than 20 cigarettes/day, category 6).

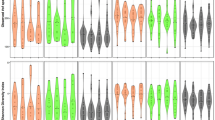

Smoking increases the number of species-level taxa

To compare the diversity of bacterial communities within each sample (alpha-diversity) between smokers and non-smokers, samples were rarefied to equal sequence numbers before calculating richness (number of observed species-level taxa), evenness, and Shannon index. The observed numbers of species-level taxa were significantly higher in smokers registering a mean of 140 ± 41 compared to 127 ± 33 in non-smokers (t-test, p = 0.022, Fig. 1), although the effect was small (Cohen’s d = 0.33). No significant differences were observed for evenness and Shannon index. The smoking frequency was not associated with significant differences in alpha-diversity (ANOVA, p > 0.5). Comparison of total cell numbers of smokers and non-smokers indicated that both groups of buccal samples contained similar amounts of bacterial cells (t-test: p > 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 4).

Alpha diversity measurements on species-level in non-smokers and smokers. Number of observed species-level taxa (left panel) and calculated evenness (right panel) are displayed as boxes with median (50th percentile), 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers that reach to 1.5 times of the interquartile ranges. Outliers are depicted as black dot.

The bacterial composition differs between smokers and non-smokers

The overall composition of the microbiome differed significantly between smokers and non-smokers (PERMANOVA based on weighted UniFrac distances including only the technical co-variate: p = 0.026, R2 = 0.013; including technical and non-technical co-variates: p = 0.038, R2 = 0.011). A principal coordinates analysis indicated a corresponding small shift in smoking behaviour-dependent clustering of samples (Fig. 2). Pairwise weighted UniFrac distances between all samples within the group of smokers did not significantly differ from distances within the group of non-smokers (ANOVA, Supplementary Fig. 5). The microbiome composition did not significantly differ between groups of different smoking frequencies (PERMANOVA based on weighted UniFrac distances, p > 0.5) which are characterized by varying, small subgroup sizes (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Most abundant taxa in the Microbiome of adolescents

Overall, the buccal microbiome of the adolescents comprised 12 phyla, 78 families, 169 genera and 733 species-level taxa that could be identified. The most prominent bacterial phyla in the adolescents’ microbiomes were Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Fusobacteria, together accounting for more than 99% of sequence reads on average (Fig. 3A). Streptococcus was on average the most abundant genus in smokers as well as in non-smokers (38 ± 15% in smokers, 39 ± 17% in non-smokers; Fig. 3B), with the Streptococcus mitis/oralis group as the most abundant species-level taxon (24 ± 15% in smokers, 26 ± 18% in non-smokers; Supplementary Fig. 6). The genera Rothia (8 ± 7% in smokers, 9 ± 9% in non-smokers), Haemophilus, Neisseria, and Gemella made up considerable proportions of the community in both smokers and non-smokers. None of these five most abundant genera differed significantly in abundance between smokers and non-smokers, as tested with DESeq2 (p adjusted > 0.05). The microbiota composition differed considerably between the individual participants (Fig. 3).

Several taxa differed significantly between smokers and non-smokers

When testing for individual taxa that significantly differed between smokers and non-smokers, we identified two phyla, 12 families 15 genus-level taxa and 34 species-level taxa that were either more or less abundant in smokers, including higher levels of Veillonella (e.g. V. atypica), multiple Actinomyces species, Dialister invisus, Atopobium parvulum, Streptococcus mutans and Prevotella melaninogenica in the smoking group (Table 2). No taxon was found to be significantly associated with the number of bacterial cells in the sample.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effects of smoking on the oral microbiome during the early stages of uptake—typically occurring in adolescence—rather than in adults with long-term established smoking habits32. In a recent German study, 15% of 14- to 20-year-olds already defined themselves as smokers33,34. While adult studies often include smokers that use more than 20 cigarettes per day12,41, in our study all of the adolescent smokers indicated lower smoking frequencies. In the present study, no effects of smoking frequency on the smokers’ oral microbiome could be demonstrated, likely due to the small sample sizes in some frequency groups. Projects to specifically examine those dose-dependent effects will likely need to be specifically targeted towards more equal representation of all smoking frequencies groups. As in our cohrt of pupils the exact duration since the first cigarette is necessarily confounded with age effects, we could not directly include this factor into our analysis, and no direct information on the duration of the participants’ smoking history was collected. Instead, we consider all smoking adolescents to be in the beginning stage of their smoking history. Combining all smokers, conventional cigarette, e-cigarette and “both types of cigarette”-smoker, into one group does of course preclude distinguishing the effects of e-cigarettes from that of tobacco smoke. However, most smokers in our study group stated that they used both conventional and e-cigarettes, hindering meaningful separation of the effects, especially when considering the limited subgroup sizes. The young age of the participants, as well as the overall low intensity of smoking, allow for an analysis of the earliest smoking-related effects on the composition of the oral microbiome. As all participants reported good oral hygiene practices and the absence of oral health issues, the observed changes predate smoking-related oral diseases. Oral health status was based solely on self-reported questionnaire data from the children, which may include inaccuracies. However, while potential undiagnosed conditions cannot be excluded, the large sample size should help to offset individual misreporting. The careful balancing of the dataset for various physiological characteristics of the participants enables reliable detection of these beginning microbiome changes at the onset of smoking. Besides other characteristics in our cohort, hormonal contraceptive use was recorded and carefully balanced between groups. Ongoing work in our group aims to elucidate its impact on the adolescent oral microbiome in greater detail. In contrast to most other studies on smoking-related changes in the oral microbiome, which are based on partial 16 S sequences, our analysis are based on full-length 16 S sequences, which allows for a higher taxonomic resolution and for classification at the species level for most sequences.

Independent of smoking, oral microbiome compositions of healthy adolescents have only rarely been analysed42. The oral communities of the adolescents in our study group are dominated by Firmicutes, mostly of the genus Streptococcus. But also Proteobacteria, in particular Haemophilus sp. and Neisseria sp., Actinobacteria (mostly Rothia sp.), and Bacteroidetes (Prevotella sp.) made up large proportions of the microbiome. This resembles the composition of healthy oral microbiomes in adults41,43,44 and young adults45, and is also similar to the saliva microbiome of children45. The numbers of species-level taxa identified in the individual oral microbiomes of the adolescents in our study match the numbers that have been reported in young adolescents and adults5,45,46, indicating that the adolescent microbiome of our cohort of 14- to 20-year-olds resembles the adult microbiome in bacterial diversity and composition, which is in line with previous findings. The overall differences in oral microbiota composition of our adolescent study group are dominated by the differences between individuals, as is usually the case in the adult oral microbiome5,47. This matches existing studies showing that during the development of the oral microbiome from newborns to adults the bacterial diversity increases, reaching approximately adult levels during adolescence45,48,49,50. While host genetics has a discernible impact on the oral microbiome in young children, this influence decreases with age51 and is overlaid by an increasing effect of environmental factors, leading to a more and more individual-specific oral microbiome until adulthood46,48,52. Smoking is known as one of these factors, which have a significant impact on the oral microbiome, altering both the composition and diversity of bacterial communities. But its effect on the adolescent microbiome has been unknown so far.

Our study demonstrates that smoking exerts a discernible impact on the overall microbiome composition of adolescents which also occurs in adults12,53. If the observed effects are nicotine-dosage dependent as observed in airway samples of adults54, could not sufficiently be addressed here because of low participant numbers in sub-groups with different smoking frequencies. One of these changes detected in the present study is a small but significant increase in species-level taxon diversity in adolescent smokers. Previous studies in adult long-term smokers could not draw a clear picture regarding the alpha-diversity in the oral microbiome. While some studies observed a reduced diversity in the buccal microbiome of smokers41, others indicated the opposite effect55, or no difference in the buccal mucosa alpha diversity14. While some of this variation might be due to technical differences leading to differences in taxonomic resolution, or to differences in the numbers of participants, an influence of demographic differences, such as sex ratios, in the selected participant groups seems likely.

Several taxa exhibited significant increased relative abundance in smokers compared to non-smokers in our study group, including the genus Veillonella and Veillonella atypica, Actinomyces and several Actinomyces species, Dialister invisus, Atopobium parvulum, Streptococcus mutans and Prevotella melaninogenica. Most of these taxa have consistently been found to be more abundant in adult smokers as well, although often on a higher taxonomic level56. Interestingly, these taxa can mostly be classified as oral pathogens, which is in line with the current literature on the oral microbiome in adult smokers, as pathogens have already been shown to be more prevalent in smokers13,57.

As one example, Veillonella sp. have been reported to play a major role as a bridging organism in the development of commensal oral biofilms but were also suggested to promote disease progression by being the physical anchor and generator of favorable growth conditions for pathogens such as P. gingivalis, and in this way may act as “accessory pathogen”58,59,60,61. In addition, Veillonella atypica was also reported in a case study of a retropharyngeal abscess62. Dialister invisus was shown to be significantly associated with periodontal infections63, Streptococcus mutans is involved in the development of dental caries64, and Atopobium parvulum, was linked to dental caries65 and halitosis66, a condition characterised by bad smelling breath caused by a dysbiosis of the oral microbiome67. In addition to those taxa connected to oral infectious diseases and caries, the species Prevotella melaninogenica has been shown to be more common in saliva samples from patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) than in patients without OSCC68. Though, Streptococcus mitis, which likewise appeared with higher levels in patients with OSCC68, was identified more frequently in non-smokers in our analysis.

Several taxa appeared with a higher relative abundance in adolescent non-smokers, some of those having been observed in other studies associated with the oral microbiome of adult non-smokers as well. This refers to the taxa Leptotrichia trevisanii or the genus Leptotrichia12, Neisseria sp13. , Haemophilus sp69. , Capnocytophaga sp12,70. and Gemella sp71. Several species of the genus Rothia including Rothia dentocariosa were increased in the adolescent non-smokers in our cohort, while other studies in adults did not observe an association with non-smokers but rather an increase in the oral microbiome of smokers14,71,72. Interestingly, almost all of the taxa, which were more abundant in non-smoking adolescents in our study, namely the Streptococcus mitis/oralis group, Neisseria sp., Haemophilus sp., Rothia dentocariosa, and Leptotrichia sp. have been associated with oral health states elsewhere63,73,74. In summary, not only did our study detect similar smoking related-shifts in several bacterial taxa in adolescent microbiome as have been observed in adult smokers, but we also identified first smoking-associated changes towards the more pathogenic bacterial community in adolescents that have regularly been observed in adults.

Several mechanisms for microbial community shifts have been proposed in relation to smoking. Previous studies suggested, that smoking reduces oxygen, pH and immune cell-based defence23,24,28,29 and thereby favours growth of anaerobic, acid-tolerant, and pathogenic over commensal bacteria in the oral microbiomes of adult smokers12,15,22,31. In line with this, several obligate anaerobic bacterial taxa have been found with differential abundance in this study, (almost) all of which were significantly increased in smokers, indicating that reduced local oxygen tension, and the associated lower availability of oxygen for microbial metabolism, could play a role in oral biofilm formation of adolescent smokers as well. Several of these taxa have pathogenic potential and could shift the biofilm towards a more pathogenic state, especially since immune defence is reduced in smokers. These smoking-associated shifts in the oral microbiome could in the long term contribute to the development and progression of oral infectious diseases as it has been described for periodontitis and peri-implantitis in adults17,19,57,75. The oral microbiome of adolescents might already set the course for future health-associated microbiomes, such as shown for an association between the oral microbiome and weight gain76, celiac disease77 and Henoch-Schönlein purpura disease78. In summary, the smoking-associated oral microbiome changes captured in this study represent a very early stage of the adverse developments in the oral microbiome of smokers.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates the early onset of smoking-related changes in the oral microbiome. These findings related to oral health provide an illustrative example of the direct adverse health consequences of smoking that might seem more tangible to adolescents than the more drastic, severe consequences that can occur later in life. Highlighting these changes in the oral microbiome might be beneficial in raising awareness of the importance of smoking prevention.

Data availability

The sequence datasets generated and analysed during the current study have been deposited at NCBI (Sequence Read Archive) and are available under the BioProject PRJNA1140369.

References

Aas, J. A., Paster, B. J., Stokes, L. N., Olsen, I. & Dewhirst, F. E. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43(11), 5721–5732 (2005).

HOMD. Human Oral Microbiome Database V3.1 https://homd.org/ 01.07.2024 (2024).

Pasolli, E. et al. Extensive unexplored human microbiome diversity revealed by over 150,000 genomes from metagenomes spanning age, geography, and lifestyle. Cell 176(3), 649–662 (2019).

Zhu, J. et al. Over 50,000 metagenomically assembled draft genomes for the human oral microbiome reveal new taxa. Genomics Proteom. Bioinf. 20(2), 246–259 (2022).

Desch, A. et al. Biofilm formation on zirconia and titanium over time-an in vivo model study. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 31(9), 865–880 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Addition of cariogenic pathogens to complex oral microflora drives significant changes in biofilm compositions and functionalities. Microbiome 11(1), 123 (2023).

Belda-Ferre, P. et al. The oral metagenome in health and disease. ISME J. 6(1), 46–56 (2012).

Wade, W. G. The oral microbiome in health and disease. Pharmacol. Res. 69(1), 137–143 (2013).

Lamont, R. J., Koo, H. & Hajishengallis, G. The oral microbiota: dynamic communities and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16(12), 745–759 (2018).

Deng, Z. L., Szafranski, S. P., Jarek, M., Bhuju, S. & Wagner-Dobler, I. Dysbiosis in chronic periodontitis: key microbial players and interactions with the human host. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 3703 (2017).

Zheng, H. et al. Analysis of oral microbial dysbiosis associated with early childhood caries. BMC Oral Health. 21(1), 181 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. Cigarette smoking and the oral microbiome in a large study of American adults. ISME J. 10(10), 2435–2446 (2016).

Pfeiffer, S. et al. Different responses of the oral, nasal and lung microbiomes to cigarette smoke. Thorax 77(2), 191–195 (2022).

Karabudak, S. et al. Analysis of the effect of smoking on the buccal microbiome using next-generation sequencing technology. J. Med. Microbiol. 68(8), 1148–1158 (2019).

Mason, M. R. et al. The subgingival microbiome of clinically healthy current and never smokers. ISME J. 9(1), 268–272 (2015).

Leite, F. R. M., Nascimento, G. G., Scheutz, F. & Lopez, R. Effect of smoking on periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-regression. Am. J. Prev. Med. 54(6), 831–841 (2018).

Shchipkova, A. Y., Nagaraja, H. N. & Kumar, P. S. Subgingival microbial profiles of smokers with periodontitis. J. Dent. Res. 89(11), 1247–1253 (2010).

Machtei, E. E. et al. Longitudinal study of predictive factors for periodontal disease and tooth loss. J. Clin. Periodontol. 26(6), 374–380 (1999).

Dreyer, H. et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of peri-implantitis: A systematic review. J. Periodontal Res. 53(5), 657–681 (2018).

Roos-Jansaker, A. M., Renvert, H., Lindahl, C. & Renvert, S. Nine- to fourteen-year follow-up of implant treatment. Part III: factors associated with peri-implant lesions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 33(4), 296–301 (2006).

Pimentel, S. P. et al. Occurrence of peri-implant diseases and risk indicators at the patient and implant levels: A multilevel cross-sectional study. J. Periodontol. 89(9), 1091–1100 (2018).

Huang, C. & Shi, G. Smoking and Microbiome in oral, airway, gut and some systemic diseases. J. Transl. Med. 17(1), 225 (2019).

Archana, M. S., Bagewadi, A. & Keluskar, V. Assessment and comparison of phagocytic function and viability of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in saliva of smokers and non-smokers. Arch. Oral Biol. 60(2), 229–233 (2015).

White, P. C. et al. Cigarette smoke modifies neutrophil chemotaxis, neutrophil extracellular trap formation and inflammatory response-related gene expression. J. Periodontal Res. 53(4), 525–535 (2018).

Churg, A., Dai, J., Tai, H., Xie, C. & Wright, J. L. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is central to acute cigarette smoke-induced inflammation and connective tissue breakdown. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 166(6), 849–854 (2002).

Lee, J., Taneja, V. & Vassallo, R. Cigarette smoking and inflammation: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Dent. Res. 91(2), 142–149 (2012).

Kenney, E. B., Saxe, S. R. & Bowles, R. D. The effect of cigarette smoking on anaerobiosis in the oral cavity. J. Periodontol. 46(2), 82–85 (1975).

Hanioka, T., Tanaka, M., Takaya, K., Matsumori, Y. & Shizukuishi, S. Pocket oxygen tension in smokers and non-smokers with periodontal disease. J. Periodontol. 71(4), 550–554 (2000).

Kanwar, A. S. K., Grover, N., Chandra, S. & Singh, R. R. Long-term effect of tobacco on resting whole mouth salivary flow rate and pH: An institutional based comparative study. Eur. J. Gen. Dent. 2, 296–299 (2013).

Sapkota, A. R., Berger, S. & Vogel, T. M. Human pathogens abundant in the bacterial metagenome of cigarettes. Environ. Health Perspect. 118(3), 351–356 (2010).

Ganesan, S. M. et al. A tale of two risks: Smoking, diabetes and the subgingival Microbiome. ISME J. 11(9), 2075–2089 (2017).

Muttarak, R. et al. Why do smokers start? Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 22(2), 181–186 (2013).

Kastaun, S. et al. Study protocol of the German study on tobacco use (DEBRA): A national household survey of smoking behaviour and cessation. BMC Public. Health. 17(1), 378 (2017).

Kotz, D., Acar, Z. & Klosterhalfen, S. German Study on Tobacco Use (DEBRA): A national household survey of smoking behaviour and cessation Factsheet 09 Konsum von Tabak und E-Zigaretten bei Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen. https://www.debra-study.info/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Factsheet-09-v3.pdf01.07.20242022

Paulsen, M. et al. Children and adolescents’ behavioral patterns in response to escalating COVID-19 restriction reveal sex and age differences. J. Adolesc. Health. 70(3), 378–386 (2022).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of Microbiome census data. PLoS One. 8(4), e61217 (2013).

Hamady, M., Lozupone, C. & Knight, R. Fast unifrac: Facilitating high-throughput phylogenetic analyses of microbial communities including analysis of pyrosequencing and phylochip data. ISME J. 4(1), 17–27 (2010).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29(22), 2933–2935 (2013).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One. 5(3), e9490 (2010).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15(12), 550 (2014).

Yu, G. et al. The effect of cigarette smoking on the oral and nasal microbiota. Microbiome 5(1), 3 (2017).

D’Agostino, S., Ferrara, E., Valentini, G., Stoica, S. A. & Dolci, M. Exploring oral microbiome in healthy infants and children: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19(18), 11403 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Comparative evaluation of the salivary and buccal mucosal microbiota by 16S rRNA sequencing for forensic investigations. Front. Microbiol. 13, 777882 (2022).

Segata, N. et al. Composition of the adult digestive tract bacterial Microbiome based on seven mouth surfaces, tonsils, throat and stool samples. Genome Biol. 13(6), R42 (2012).

Lif Holgerson, P., Esberg, A., Sjodin, A., West, C. E. & Johansson, I. A longitudinal study of the development of the saliva microbiome in infants 2 days to 5 years compared to the microbiome in adolescents. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 9629 (2020).

Esberg, A., Haworth, S., Kuja-Halkola, R., Magnusson, P. K. E. & Johansson, I. Heritability of oral microbiota and immune responses to oral bacteria. Microorganisms 8(8), 1126 (2020).

Hall, M. W. et al. Inter-personal diversity and temporal dynamics of dental, tongue, and salivary microbiota in the healthy oral cavity. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 3, 2 (2017).

Mason, M. R., Chambers, S., Dabdoub, S. M., Thikkurissy, S. & Kumar, P. S. Characterizing oral microbial communities across dentition states and colonization niches. Microbiome 6(1), 67 (2018).

Dashper, S. G. et al. Temporal development of the oral microbiome and prediction of early childhood caries. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 19732 (2019).

Dzidic, M. et al. Oral microbiome development during childhood: An ecological succession influenced by postnatal factors and associated with tooth decay. ISME J. 12(9), 2292–2306 (2018).

Gomez, A. et al. Host genetic control of the oral microbiome in health and disease. Cell. Host Microbe. 22(3), 269–278 (2017).

Li, X., Liu, Y., Yang, X., Li, C. & Song, Z. The oral microbiota: Community composition, influencing factors, pathogenesis, and interventions. Front. Microbiol. 13, 895537 (2022).

Fan, J. Y. et al. Cross-talks between gut microbiota and tobacco smoking: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. BMC Med. 21(1), 163 (2023).

Lim, M. Y. et al. Analysis of the association between host genetics, smoking, and sputum microbiota in healthy humans. Sci. Rep. 6, 23745 (2016).

Gopinath, D. et al. Compositional profile of mucosal bacteriome of smokers and smokeless tobacco users. Clin. Oral Investig. 26(2), 1647–1656 (2022).

Maki, K. A. et al. The role of the oral Microbiome in smoking-related cardiovascular risk: A review of the literature exploring mechanisms and pathways. J. Transl. Med. 20(1), 584 (2022).

Kumar, P. S., Matthews, C. R., Joshi, V., de Jager, M. & Aspiras, M. Tobacco smoking affects bacterial acquisition and colonization in oral biofilms. Infect. Immun. 79(11), 4730–4738 (2011).

Periasamy, S. & Kolenbrander, P. E. Central role of the early colonizer Veillonella sp. in establishing multispecies biofilm communities with initial, middle, and late colonizers of enamel. J. Bacteriol. 192(12), 2965–2972 (2010).

Zhou, P., Manoil, D., Belibasakis, G. N. & Kotsakis, G. A. Veillonellae: Beyond bridging species in oral biofilm ecology. Front. Oral Health. 2, 774115 (2021).

Hoare, A. et al. A cross-species interaction with a symbiotic commensal enables cell-density-dependent growth and in vivo virulence of an oral pathogen. ISME J. 15(5), 1490–1504 (2021).

Zhou, P., Li, X., Huang, I. H. & Qi, F. Veillonella catalase protects the growth of Fusobacterium nucleatum in microaerophilic and Streptococcus gordonii-Resident environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83, 19 (2017).

Kumar, P., Kumaresan, M., Biswas, R. & Saxena, S. K. Veillonella atypica causing retropharyngeal abscess: A rare case presentation. Anaerobe 81, 102712 (2023).

Antezack, A., Etchecopar-Etchart, D., La Scola, B. & Monnet-Corti, V. New putative periodontopathogens and periodontal health-associated species: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Periodontal Res. 58(5), 893–906 (2023).

Lemos, J. A. et al. The biology of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol. Spectr. ;7(1), 10–1128 (2019).

Fakhruddin, K. S., Samaranayake, L. P., Hamoudi, R. A., Ngo, H. C. & Egusa, H. Diversity of site-specific microbes of occlusal and proximal lesions in severe-early childhood caries (S-ECC). J. Oral Microbiol. 14(1), 2037832 (2022).

Kazor, C. E. et al. Diversity of bacterial populations on the tongue Dorsa of patients with halitosis and healthy patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41(2), 558–563 (2003).

Persson, S., Edlund, M. B., Claesson, R. & Carlsson, J. The formation of hydrogen sulfide and methyl mercaptan by oral bacteria. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 5(4), 195–201 (1990).

Mager, D. L. et al. The salivary microbiota as a diagnostic indicator of oral cancer: A descriptive, non-randomized study of cancer-free and oral squamous cell carcinoma subjects. J. Transl Med. 3, 27 (2005).

Sato, N. et al. The relationship between cigarette smoking and the tongue microbiome in an East Asian population. J. Oral Microbiol. 12(1), 1742527 (2020).

Suzuki, N., Nakano, Y., Yoneda, M., Hirofuji, T. & Hanioka, T. The effects of cigarette smoking on the salivary and tongue microbiome. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 8(1), 449–456 (2022).

Thomas, A. M. et al. Alcohol and tobacco consumption affects bacterial richness in oral cavity mucosa biofilms. BMC Microbiol. 14, 250 (2014).

Jia, Y. J. et al. Association between oral microbiota and cigarette smoking in the Chinese population. Front. Cell. Infect. Mi 11, 658203 (2021).

Sanz-Martin, I. et al. Exploring the microbiome of healthy and diseased peri-implant sites using illumina sequencing. J. Clin. Periodontol. 44(12), 1274–1284 (2017).

Belibasakis, G. N. & Manoil, D. Microbial community-driven etiopathogenesis of peri-implantitis. J. Dent. Res. 100(1), 21–28 (2021).

Apatzidou, D. A. The role of cigarette smoking in periodontal disease and treatment outcomes of dental implant therapy. Periodontol 2000. 90(1), 45–61 (2022).

Craig, S. J. C. et al. Child weight gain trajectories linked to oral microbiota composition. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 14030 (2018).

Francavilla, R. et al. Salivary microbiota and metabolome associated with celiac disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80(11), 3416–3425 (2014).

Chen, B. et al. Oral microbiota dysbiosis and its association with Henoch-Schonlein purpura in children. Int. Immunopharmacol. 65, 295–302 (2018).

Acknowledgements

For the organisational support at the schools, we acknowledge the contributions of Beate Günther, Philipp Tups, Katharina Kalinowski, Rita Wonik-Schmidt, Brigitte Naber and Frank Weinberg. We are also grateful to all study participants at the schools, including the staff, teachers and students for their support of the TRAC-19 Study and as well as all study personal for their contributions in gathering data and samples.For the logistical support, the authors would like to thank Maxine Swallow and Dr. Thorsten Saenger. Rainer Schreeb, Dr. Hoda Radmanesh, Rebecca Hiß, Sarah Wielgosz, Johanna Klodt and Marlena A. Rumohr provided excellent technical support. Thanks to Dr. Claudia Davenport for proofreading the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was financed by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—SFB/TRR-298-SIIRI—Project-ID 426335750 and the Ministry of Science and Culture of Lower Saxony in the framework of TRAC-19 (Grant number: 14-76103-184). WB and IY are funded by the “Federal and State Program Promoting Female Professors”, Grant No. 01FP19068J. IY is additionally supported by the program “Women Professors for Lower Saxony”, Reference No. 22-76251-99 P4/20. None of the funding agencies had a role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PSD Data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. WB Data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. AW Conceptualization, project administration, writing—review and editing. PCP Conceptualization, project administration, supervision, writing—review and editing. MP Conceptualization, project administration, writing—review and editing. NS Resources, writing—review and editing. FT Data curation, writing—review and editing. AM Conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources, writing—review and editing. BMWS Conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing. HL Conceptualization, writing—review and editing. SH Conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing. NK Project administration, resources, writing—review and editing. TI Conceptualization, writing—review and editing. HB Conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing. CB Conceptualization, writing—review and editing. IY Data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software, supervision, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. MS Conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hannover Medical School (Ethical Vote No. 9085_BO_S_2020) and complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participation in the study was voluntary and required the written consent of the participants and the legal guardians of minors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schaefer-Dreyer, P., Behrens, W., Winkel, A. et al. Effects of cigarette smoking on the oral microbiome in adolescents. Sci Rep 16, 1348 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32650-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32650-2