Abstract

Intestinal parasitic infections remain a major global public health concern, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of intestinal parasites, identify associated risk factors, and compare diagnostic techniques among school children in both central and rural areas of Shendi locality, Sudan. A school-based cross-sectional study was conducted from January 2021 to April 2024. A total of 1,200 students were selected using a simple random sampling method. Data were collected through direct interviews using a pretested questionnaire. Stool specimens were collected in clean, labeled plastic containers and examined microscopically for eggs, cysts, and trophozoites using three diagnostic techniques: Wet preparation, Formol-ether concentration (FECT), and Flotation (FLO). Data were analyzed using SPSSV22 software. The overall prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections was 35.3% (423/1200; 95% CI: 32.7–38.0), with a mean infection intensity of 12.04 ± 1.9 eggs per gram (EPG), (Estimation of Egg Per Gram (EPG); mean ± standard deviation (SD)). Prevalence was higher in males (38.1%) than females (33.7%) but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.09). Infection decreased significantly with increasing age (p < 0.001); It peaked among children aged 5–7 years (47.0%), then declined to 33.8% at 8–10 years and 27.0% at 11–13 years. Regarding diagnostic performance, FECT tended to show slightly higher fecal egg counts (mean = 7.1 ± 1.2 EPG) compared to FLO (mean = 5.1 ± 0.8 EPG), (where ± represents the standard deviation). Six genera of intestinal parasites were identified: protozoa (Entamoeba coli 11.7%, Entamoeba histolytica 8.8%, Giardia duodenalis 7.3%) and helminths (Enterobius vermicularis 2.6%, Hymenolepis nana 4.7%, Taenia spp. 0.3%). Infection prevalence showed significant variation by residential area, age group, awareness of transmission, handwashing practices, and presence of symptoms (p < 0.05). The study demonstrated a moderate prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among school-aged children in Shendi locality (35.3%), with higher rates among younger children and those residing in rural areas. Six parasite genera were identified. Infection was significantly associated with hygiene behaviors, handwashing practices, and awareness of transmission (p < 0.05). The formol-ether concentration technique showed higher diagnostic sensitivity than flotation. These findings highlight the need for integrated interventions combining deworming, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) improvements, and school-based health education to reduce reinfection and achieve sustainable parasite control in Shendi and similar settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs) remain a significant global health concern, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where they contribute to morbidity, malnutrition, and impaired cognitive development1. Soil-transmitted helminths (STHs), including Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, and hookworms, are among the most prevalent human infections worldwide, affecting over 25% of the global population6,7. Other helminths, such as Strongyloides stercoralis, although less studied, are important contributors to chronic morbidity8. Protozoan parasites, including Giardia intestinalis and Entamoeba histolytica, are leading causes of diarrheal illness globally2,20. These infections are driven by environmental, social, and behavioral factors, including poor sanitation, lack of safe water, poverty, overcrowding, and inadequate hygiene education4,13,23.

Although IPIs are predominantly concentrated in tropical and subtropical regions, globalization, increased travel, and migration have contributed to their emergence in developed countries3. Mass drug administration (MDA) programs using anthelmintics such as albendazole and mebendazole have reduced infection intensity in many endemic areas; however, high prevalence persists due to inadequate improvements in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure9,10,11. Children remain the most vulnerable demographic, particularly in contexts characterized by poor sanitation, malnutrition, and high population density14,15.

In Sudan, IPIs are endemic, yet comprehensive national data remain limited, which constrains evidence-based policy making and effective control planning24,35,36. Local studies report markedly variable prevalence rates, demonstrating substantial geographical heterogeneity. For example, prevalence among children under five in Khartoum is 12.5%25, whereas some localities report rates as high as 87.2% among schoolchildren28. Infection patterns also differ by parasite species and region: Ascaris lumbricoides prevalence ranges from 1.2% in Alhag Yousif29 to 32.5% in Eldhayga30, while hookworm prevalence ranges from 4.2% to 24% across different states31. Among adults, lower yet notable STH prevalence is reported, such as 7.8% in war-affected Southern Kordofan and 3–5% among renal transplant recipients in Khartoum33,34. These data underscore the unequal distribution of intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs) across Sudan and the consequent need for targeted, evidence-based interventions. Despite an increasing number of local studies, a clear knowledge gap persists regarding the epidemiology of IPIs in Shendi Locality, River Nile State - an area with distinct environmental and socio-demographic characteristics yet limited published information. Addressing this gap is essential for developing interventions aligned with national and WHO recommendations. Furthermore, only a few studies in Sudan have simultaneously examined risk factors and compared the performance of commonly used diagnostic techniques within school settings. A thorough understanding of local epidemiology is therefore critical for designing effective public health strategies, optimizing resource allocation, and implementing control measures consistent with WHO guidelines10,11.

This study aims to determine the prevalence of intestinal parasites among schoolchildren in both central and rural areas of Shendi locality in Sudan, identify the factors associated with these infections, and compare the diagnostic methods used. It also seeks to clarify how these infections are distributed among children, highlight key demographic, environmental, and behavioral influences, and and compare the diagnostic performance of three commonly used stool examination techniques; wet preparation, formol-ether concentration, and flotation, to support more effective diagnostic practices in similar settings. Overall, this focused epidemiological investigation provides essential baseline information to guide future prevention and control efforts in Shendi and comparable regions.

Methods

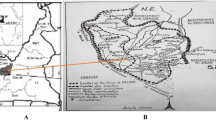

Study area (Shendi locality)

Shendi locality, situated on the east bank of the River Nile, northern Sudan, geo-coordinately between 16 40 52 and 33 25 7 E. located in the north of Khartoum state, and it is bordered to the north by the village of AL-Dika and to the south by the village of Al-Misikitb in the south. The area has semi-arid climatic features with a very short rain period in August, and a mean annual temperature of 40ᵒ C.Shendi locality has a number of rural administrative units, which are the Kaboshia, t district the South Shendi district the North Shendi district, the Al-Basabeer district and Hajer Alasal unit. The South Shendi unit starts from Algilayaa village to Wad Banaga village, in these areas 48 basic schools, of which 9 are boys schools, 9 are girl’s schools, and 30 are mixed schools.

The North Shendi district has number of basic schools, 33 basic schools, of which 10 are for boys and 10 are for girls and 13 are for mixed schools, geographical limits of this north areas start from Alshagalwa village even AL-Dushin village. Most tribes of the population in Shendi locality are AL-Jaaleen, AL-Shaigia, AL-Hassania and AL-Ababda, most of them work in agriculture and trade.

Study design and period

Schools based Cross-sectional study was conducted from January 2021 to April 2024.

Study population

The study population comprised basic-school students (N = 35930 students); from the northern countryside (10498 students), southern countryside (13811 students), and central areas of Shendi Locality (11621).

Sample size determination

The sample size was calculated using the finite population formula, which is appropriate when the total number of individuals (N) is known. This method ensures sufficient precision while preventing unnecessary oversampling. The required sample size was determined using the equation:\(n = \frac{N}{{1 + N \times {d^2}}}\)

Where is the n = required sample size, N = total number of students in the selected schools, d = desired margin of error (precision, set at 0.05 for this study with a 95% confidence level). This formula is derived from Yamane’s widely used method for determining sample size in finite populations58.

Based on school enrollment data, the calculated sample sizes were: Northern countryside: 386 students, Southern countryside: 400 students, Central Shendi: 387 students.

To reduce sampling error, the total sample size was increased to 1,200 students. Participants were selected from 40 schools: 13 schools from the northern and southern districts each, and 14 schools from the central district. Within each school, students from the first, second, and fourth intermediate classes were randomly selected, with 30 students per class.

Inclusion criteria

School Students enrolled in the selected schools whose parents/guardians provided written informed consent, and who were present on the day of data collection.

Exclusion criteria

Students who had received antiparasitic treatment within the previous 6 weeks, those with severe acute illness, or those unable to provide stool samples.

Stool sample collection

Each participant was provided with a clean, pre-labeled plastic container and instructed to submit 2–5 g of fresh stool. Samples were transported to the Research Laboratory at Shendi University in ice-cooled carriers. Whenever possible, samples were examined immediately; those not processed upon arrival were stored at 4 °C and examined within 12–24 h, a timeframe considered acceptable for maintaining parasite morphology.

Laboratory examination of stool

-

Wet Mount Examination: Wet mounts were prepared using physiological saline and Lugol’s iodine for the qualitative detection of protozoan trophozoites, cysts, and helminth eggs. This method was used solely for qualitative assessment.

-

Direct Smear: Approximately 2 mg of stool was emulsified in normal saline on a glass slide and examined under 10× and 40× magnification following standard parasitological procedures.

-

Formol–Ether Concentration Technique (FECT): The concentration procedure followed WHO-recommended protocols. One gram of stool was mixed with 10 mL of 10% formalin, filtered, and combined with 3 mL of ether (ethyl acetate). The mixture was centrifuged at 800 ×g for 2 min, a deliberate modification from the standard 500 ×g to enhance sedimentation efficiency57. The sediment was examined microscopically for ova, cysts, and larvae.

-

Sodium Chloride Flotation Technique: A qualitative flotation method was performed using saturated sodium chloride solution. One gram of stool was homogenized in the flotation medium; a coverslip was applied for 30–45 min before microscopic examination.

Estimation of egg per gram (EPG)

Helminth infection intensity was assessed using a semi-quantitative scoring system adapted from WHO guidelines59. Defined stool quantities (1 g for concentration/flotation procedures and 2 mg for direct smear) were used to categorize relative parasite loads and convert them into approximate EPG ranges.

Quality control

All slides were independently examined by two trained laboratory technicians, with at least two slides prepared per sample. Any discrepancies were resolved through review by a senior parasitologist to ensure diagnostic accuracy.

Questionnaire

A pre-tested questionnaire collected demographic data, assessed exposure to risk factors, and evaluated knowledge and practices regarding intestinal parasites.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSSv22 (IBM) software. Prevalence rates were calculated with 95% confidence intervals. Means and standard deviations were used for continuous variables. Chi-square tests assessed associations, and logistic regression (bivariate and multivariate) identified risk factors. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Sudan Ministry of Health and the Ministry of General Education (ME.SH/Jan, 2021). Written informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians and students. Participation was voluntary, and students could withdraw at any time. Confidentiality and privacy were strictly maintained.

Results

Characteristics of study population

A total of 1,200 stool samples were collected and examined from school-aged children (SAC) residing in three geographical zones of Shendi Locality: the northern countryside, southern countryside, and the city center.

Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs)

Overall, intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs) were detected in 35.3% (423/1200; 95% CI: 32.7–38.0) of the examined children, indicating that more than one-third of the study population harbored one or more intestinal parasites. The difference in infection rates among the three study areas was statistically significant (χ² = 6.41, p < 0.05) (Table 1).

The most frequently detected parasite was Entamoeba coli (11.7%; 95% CI: 9.9–13.5), followed by Entamoeba histolytica (8.8%; 95% CI: 7.1–10.4) and Giardia duodenalis (7.3%; 95% CI: 5.8–8.9). The less common parasites included Hymenolepis nana (4.7%; 95% CI: 3.5–6.0), Enterobius vermicularis (2.6%; 95% CI: 1.7–3.6), and Taenia spp. (0.3%; 95% CI: 0.0–0.6). The overall mean intensity of infection was 12.04 ± 1.9, with the highest mean intensity recorded for Enterobius vermicularis (20.9 ± 7.7) (Table 1).

Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs) by three geographical areas in Shendi

When comparing infection rates across the three geographical areas, a noticeable variation was observed (Table 2). The northern countryside recorded the highest prevalence (38.0%), followed by the southern countryside (37.1%), whereas the city center showed the lowest rate (30.9%). This variation was statistically significant (p < 0.05). Protozoan infections (Entamoeba histolytica and Gardia duodenalis) were more frequent in rural areas, while Entamoeba coli was slightly higher in the city center. Helminthic infections (Enterobius vermicularis and Hymenolepis nana) were also more prevalent in the rural zones.

These findings indicate that children living in rural areas are more vulnerable to intestinal parasitic infections than those in the urban setting. This pattern likely reflects variations in environmental sanitation, hygiene practices, and access to clean water among the study zones.

Risk factors associated with intestinal parasitic infections in Shendi

Sociodemographic and behavioral variables were analyzed to determine factors associated with intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs) among school-aged children (Table 3). Although males (37.6%) showed slightly higher infection rates than females (32.8%), the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.09). Age demonstrated a clear inverse relationship with infection: children aged 7 years were most affected, while infection odds decreased significantly among older age groups (10 and 13 years; p ≤ 0.001). Hygiene-related behaviors showed strong associations with infection risk. Children who washed their hands with water only or did not wash at school were more likely to be infected compared to those using water and soap (p < 0.05). Similarly, inconsistent handwashing after defecation (sometimes) significantly increased the risk (AOR = 1.93; p < 0.001).

Lack of awareness about parasite transmission also correlated with higher infection rates (AOR = 1.54; p = 0.018). Other variables, including vegetable washing, toilet availability, previous infection, and treatment type, showed no significant association with infection.

Performance and comparison of diagnostic techniques

The intensity of intestinal parasitic infections among school-age children in Shendi locality, River Nile State, Sudan, was assessed using a semi-quantitative scoring system adapted from WHO guidelines. Defined stool quantities were used for each diagnostic method: 1 g for concentration/flotation procedures and 2 mg for direct smear, allowing categorization of relative parasite loads and conversion into approximate EPG ranges. This approach provides a standardized estimate of infection intensity rather than exact egg counts. The intensity levels obtained from the three diagnostic techniques, based on this semi-quantitative approach, are summarized in Table 4.

Formol-Ether Concentration Technique (FECT) detected the highest parasite intensity across all species, followed by FLO while WP showed the lowest intensity. Differences among methods were statistically significant (P < 0.001). The values reported are semi-quantitative EPG estimates, derived from standardized stool volumes and WHO-adapted scoring, providing a relative measure of infection intensity rather than exact egg counts. This approach allows comparison of diagnostic sensitivity and relative parasite loads among techniques in low-resource settings.

Discussion

Intestinal parasitic infections continue to represent a major global public health challenge, affecting nearly one-fourth of the world’s population37. Despite the availability of multiple control strategies, progress in reducing the infection burden remains slow in low-resource settings. Structural determinants; including inadequate sanitation, poor hygiene infrastructure, and limited access to safe water sustain transmission cycles. The World Health Organization highlights that reinfection driven by persistent environmental exposure constitutes a significant barrier to achieving long-term and sustainable parasite control37.

In the present study, the overall prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among school-aged children in Shendi locality was 35.3% (423/1200; 95% CI: 32.7–38.0), indicating that more than one-third of the study population harbored one or more intestinal parasites. A statistically significant variation in prevalence was detected across the three geographical areas, with the northern countryside recording the highest infection rate (χ² = 6.41, p < 0.05). Such heterogeneity likely reflects the interplay between environmental exposure risks such as differences in water quality, sanitation levels, and household socioeconomic conditions and host-related vulnerability, all of which may increase susceptibility among children in certain settings.

The observed prevalence is also shaped by the diagnostic performance of the methods employed. Three diagnostic techniques were used: direct wet mount, formol-ether concentration, and salt flotation. The formol-ether concentration technique yielded the highest diagnostic sensitivity, consistent with findings by Amal et al.38 and Knight et al.39, who reported its superior ability to detect a broad spectrum of parasitic stages. However, studies such as that of Hersh Ahmed et al.51 have demonstrated that salt flotation more effectively recovers specific helminth eggs. These methodological differences highlight that discrepancies in prevalence estimates across studies may partly reflect the varying sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic protocols, rather than true epidemiological differences. Therefore, interpreting prevalence figures requires consideration of both biological and methodological sources of variation.

When compared with findings from other regions, the prevalence observed in the present study was lower than those reported from Dagi Primary School40, Delgi in North Gondar41, and Chencha town in Southern Ethiopia42, yet higher than prevalence estimates documented in Arba Minch43 and Debre Birhan44. These inter-regional discrepancies likely arise from a complex interaction of environmental and methodological factors. Variations in climate, soil characteristics, and water availability can influence the survival and transmission of intestinal parasites, while differences in sanitation infrastructure and hygiene practices shape exposure risk. Additionally, inconsistent diagnostic methodologies across studies including variations in sample preservation, number of samples examined, and the sensitivity of detection techniques represent an important source of epidemiological divergence. Taken together, these factors underscore the need to interpret prevalence data within both their ecological and methodological contexts, rather than viewing such comparisons as solely reflective of true epidemiological variation.

The highest infection rates in this study occurred among younger children (7 years), a pattern consistent with observations from Nigeria48. At this developmental stage, children typically engage in more frequent soil contact, exploratory play, and exhibit limited awareness of personal hygiene, all of which increase their likelihood of exposure. The absence of significant gender differences aligns with findings from North Ethiopia49, suggesting that boys and girls in these settings share similar environmental exposures and behavioral patterns. Nevertheless, contrasting evidence from Iran50, where gender disparities were reported illustrates the influence of context-specific cultural practices, gendered responsibilities, and behavioral norms on exposure risk, emphasizing that demographic effects cannot be generalized across diverse populations.

Behavioral and hygiene factors contributed significantly to infection patterns. Handwashing after defecation and consistent use of soap were associated with lower infection rates, underscoring the importance of WASH interventions. Although 99.6% of children reported latrine access, infections persisted, indicating that latrine availability alone is insufficient without proper maintenance, behavior change, and consistent usage. This aligns with reports from Sudan and neighboring regions showing that functional WASH infrastructure is more predictive of infection reduction than latrine presence alone.

Persistent transmission is further influenced by environmental contamination and limited access to clean water. This corresponds with global evidence that reinfection occurs rapidly following deworming in the absence of integrated sanitation improvements47.

The observed prevalence may also reflect the diagnostic sensitivity of the methods used. Three techniques were employed direct wet mount, formol-ether concentration, and salt flotation. The formol-ether concentration method demonstrated the highest sensitivity and diagnostic yield, consistent with the findings of Amal et al.38 and Knight et al.39, who confirmed its reliability for detecting light infections. However, Hersh Ahmed et al.51 reported greater sensitivity for salt flotation due to its ability to separate parasitic elements from debris, though sedimentation techniques such as formol-ether concentration recover a wider range of organisms52. Therefore, differences in diagnostic techniques between studies could partially explain variations in reported prevalence rates.

All infected individuals received appropriate treatment under medical supervision. Albendazole or mebendazole was used for soil-transmitted helminths; praziquantel for Schistosoma mansoni and Taenia spp.; ivermectin or extended albendazole regimens for Strongyloides stercoralis; and metronidazole for Giardia duodenalis and Entamoeba histolytica. While pharmacological treatment remains essential, it should be embedded within comprehensive WASH programs and educational efforts to prevent rapid reinfection. treatment without parallel WASH interventions is unlikely to yield sustainable reductions in prevalence. Public health strategies should therefore integrate deworming with health education and community-level sanitation improvements.

This study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design captures only a single time point, which may not reflect seasonal variations in infection. Second, reliance on a single stool sample per child might underestimate prevalence, especially in light infections. Furthermore, egg quantification using qualitative methods (EPG) may underestimate prevalence, particularly in light infections. Third, behavioral and WASH-related data were self-reported, which could introduce reporting bias. Finally, the limited availability of comparable Sudanese studies restricted the depth of contextual analysis.

To achieve sustainable reductions in intestinal parasitic infections, a multi-pronged approach is required. Strengthening school-based deworming, expanding access to safe water and sanitation, and integrating health education into school curricula are crucial. Intersectoral collaboration and community engagement should be prioritized to break the cycle of transmission and ensure long-term public health gains.

Conclusion

The study demonstrated a moderate prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among school-aged children in Shendi locality (35.3%), with higher rates among younger children and those residing in rural areas. Six parasite genera were identified. Infection was significantly associated with hygiene behaviors, handwashing practices, and awareness of transmission (p < 0.05). The formol-ether concentration technique showed higher diagnostic sensitivity than flotation. These findings highlight the need for integrated interventions combining deworming, WASH improvements, and school-based health education to reduce reinfection and achieve sustainable parasite control in Shendi and similar settings.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author or reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- IPIs:

-

Intestinal parasites infections

- WASH:

-

Water, sanitation, and hygiene

- WHO:

-

World health organization

- MDA:

-

Mass drug administration

- SSA:

-

Sub-saharan africa

- MOH:

-

Ministry of health

- DALYs:

-

Disability-adjusted life years

- DFS:

-

Direct fecal smear

- FET:

-

Formal-ether technique

- KAP:

-

Knowledge, attitude and practice

- GIS:

-

Geographical information systems

- WHA:

-

World health assembly

- IP:

-

Intestinal Parasite

References

Wong, L. W. et al. Human intestinal parasitic infection: a narrative review on global prevalence and epidemiological insights on preventive, therapeutic and diagnostic strategies for future perspectives. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14 (11), 1093–1105 (2020).

Mahmud, R., Lim, Y. A. L. & Amir, A. Medical parasitology. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68795-7

Ahmed, M. Intestinal parasitic infections in 2023. Gastroenterol. Res. 16 (3), 127 (2023).

Fletcher, S. M., Stark, D. & Ellis, J. Prevalence of gastrointestinal pathogens in Sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. public. health Afr. 2(2), (2011).

Sarmiento, J. L. A. Intestinal parasitic infections in adults living with HIV in the department of Cochabamba, Bolivia (2023).

Riaz, M. et al. Prevalence, risk factors, challenges, and the currently available diagnostic tools for the determination of helminths infections in human. Eur. J. Inflamm. 18, 2058739220959915 (2020).

Knox, J. Novel Approaches for Anthelmintic and Nematicide Discovery (Doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto (Canada)). (2024).

Page, W., Judd, J. A. & Bradbury, R. S. The unique life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis and implications for public health action. Trop. Med. Infect. Disease. 3 (2), 53 (2018).

Chege, N. M. Prevalence, Molecular Characterization and Risk Factors Associated With Intestinal Parasites among School Going Children from Informal Settlements of Nakuru Town, Kenya (Doctoral dissertation, Egerton University). (2021).

Mofid, L. S. Maternal postpartum deworming: a novel strategy to reduce infant and maternal morbidity in low-and-middle-income countries (McGill University (Canada), 2016).

Mitra, A. K. & Mawson, A. R. Neglected tropical diseases: epidemiology and global burden. Trop. Med. Infect. Disease. 2 (3), 36 (2017).

OYEBAMIJI, D. A. ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS AND CULTURAL PRACTICES INFLUENCING THE EPIDEMIOLOGY OF SOIL TRANSMITTED HELMINTHS IN IBADAN, NIGERIA (Doctoral dissertation). (2023).

Sartorius, B. et al. Prevalence and intensity of soil-transmitted helminth infections of children in sub-Saharan Africa, 2000–18: a Geospatial analysis. Lancet Global Health. 9 (1), e52–e60 (2021).

Sousa-Figueiredo, J. C. et al. Epidemiology of malaria, schistosomiasis, geohelminths, anemia and malnutrition in the context of a demographic surveillance system in northern Angola. PloS one 7(4), (2012).

Paruch, A. M. Possible scenarios of environmental transport, occurrence and fate of helminth eggs in light weight aggregate wastewater treatment systems. Reviews Environ. Sci. Bio/Technology. 9 (1), 51–58 (2010).

Gyapong, J. O. et al. Integration of control of neglected tropical diseases into health-care systems: challenges and opportunities. Lancet 375 (9709), 160–165 (2010).

Molyneux, D. H., Savioli, L. & Engels, D. Neglected tropical diseases: progress towards addressing the chronic pandemic. Lancet 389 (10066), 312–325 (2017).

AL-kafaji, M. S. A. & Alsaadi, Z. H. Pinworms infection. Jour Med. Resh Health Sci. 5 (8), 2182–2189 (2022).

Khubchandani, I. T. & Bub, D. S. Parasitic infections. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 32 (05), 364–371 (2019).

Beiting, D. P. & John, A. R. O. Parasitic diseases: protozoa 3022–3038 (Yamada’s Textbook of Gastroenterology, 2022).

Trelis, M. et al. Giardia intestinalis and Fructose malabsorption: a frequent association. Nutrients 11 (12), 2973 (2019).

Oyegue-Liabagui, S. L. et al. Molecular prevalence of intestinal parasites infections in children with diarrhea in Franceville, Southeast of Gabon. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 1–11 (2020).

Olaolu, D. T., Akpor, O. B. & Akor, C. O. Pollution indicators and pathogenic microorganisms in wastewater treatment: implication on receiving water bodies. Int. J. Environ. Prot. Policy. 2 (6), 205–212 (2014).

Siddig, E. E. & Ahmed, A. The challenge of triple intestinal parasite infections in immigrants—A call for comprehensive differential diagnosis. Clin. Case Rep., 12(11), e9549. (2024).

Abdel Aziem, A. A. & Gasim, G. I. Intestinal parasitic infections in sudan: A review Article. Sudan. J. Public. Health. 7 (3), 109–112 (2012).

Abdelrahman, A. M. & Khalid, A. M. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among children under five in Khartoum State, Sudan. Sudan. J. Paediatrics. 15 (2), 89–94 (2015).

Hassan, E. A. & Osman, M. E. Intestinal parasitic infections among displaced populations in Eastern Sudan. East. Mediterr. Health J. 20 (9), 560–566 (2014).

Elmubarak, A. K. & Ibrahim, A. M. Prevalence of intestinal helminths among school children in river nile State, Sudan. J. Parasitic Dis. 42 (4), 569–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12639-018-1069-4 (2018).

Ahmed, E. A. A. & Musa, H. A. Intestinal parasitosis among school children in Berber locality, river nile State, Sudan. Sudan. J. Paediatrics. 17 (1), 52–58 (2017).

Elamin, A. A. The prevalence of intestinal parasites in Alhag Yousif area, Khartoum State, Sudan. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 6 (6), 2843–2849. https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2017.606.336 (2017).

Osman, A. M. & Abdalla, M. A. Distribution of intestinal parasites among school children in Eldhayga village, South Darfur, Sudan. J. Med. Med. Sci. 1 (10), 453–455 (2010).

Idris, Y. M. A. Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminths among primary school children in Kosti City, white nile State, Sudan. Int. J. Adv. Res. 7 (2), 712–717. https://doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/8541 (2019).

John, C. & Lado, M. A survey of intestinal helminths among school children in Malakal, upper nile State, South Sudan. South. Sudan. Med. J. 9 (2), 28–31 (2016).

.Suliman, M. A. & Osman, A. A. Intestinal parasites among adults in conflict-affected areas of South Kordofan, Sudan. East Afr. Med. J. 92 (6), 285–289 (2015).

Elhag, K. M. & Abdallah, M. A. Intestinal parasites among renal transplant recipients in Khartoum state. Sudan. Nephrol. Reviews. 5 (1), 18–22. https://doi.org/10.4081/nt.2013.e (2013).

World Health Organization (WHO). Helminth Control in school-age Children: A Guide for Managers of Control Programmes 3rd edn (World Health Organization, 2017).

World Health Organization. Prevention and Control of Intestinal Parasitic Infections (WHO, 2002).

Parija, S. C. Textbook of Medical Parasitology 1st edn (All India Publishers & Distributors, 1999).

Amal, R. Comparison of stool examination methods for intestinal parasites. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 33 (3 Suppl), 927–937 (2003).

Mbanugo, J. I. & Okakpu, K. M. A study on the prevalence of intestinal parasites among children in Anambra State, Nigeria. Nigerian J. Parasitol. 25, 67–72 (2004).

Knight, W. B., Hiatt, R. A., Cline, B. L. & Ritchie, L. S. A modification of the formol-ether concentration technique for increased sensitivity in detecting schistosoma mansoni eggs. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 25 (6), 818–823 (1976).

Alamir, M. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among school children in Dagi primary school, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 23 (2), 123–129 (2013).

Ayalew, A. T. & Debebe, A. Intestinal parasitic infections and associated risk factors among school children in Delgi town, Northwest Ethiopia. Am. J. Health Res. 1 (3), 123–128 (2011).

Abossie, A. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among patients in Chencha town, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 28 (1), 70–76 (2014).

Haftu, D. Prevalence of intestinal parasites and associated factors among primary school children in Arba minch town, Southern Ethiopia. Sci. J. Public. Health. 2 (6), 507–512 (2014).

Zemene, T. Intestinal parasitic infections and associated risk factors among students at Debre Birhan University, Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes. 11, 719. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3866-7 (2018).

Andualem, M. Effect of hand hygiene on parasitic infections among school children in Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 24 (3), 205–212 (2014).

Al-Mohammed, H. I. & Amin, T. T. Prevalence and pattern of intestinal parasitic infections among Saudi Arabian children. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 40 (3), 563–572 (2010).

Tadesse, D. & Beyene, P. Relationship between toilet availability and prevalence of intestinal parasites among school children. Ethiop. Med. J. 47 (3), 213–219 (2009).

Berhanu, E. Risk factors associated with intestinal parasitic infections among children in Ethiopia. East Afr. Med. J. 72 (7), 412–415 (1995).

Wördemann, M. et al. Risk factors for intestinal parasitic infections in children from urban and rural communities in Senegal. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 100 (9), 858–866 (2006).

Dessie, A. Prevalence and associated risk factors of intestinal parasitic infections among children in Glomekeda district, Southern Ethiopia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 79 (Suppl 1), 77 (2019).

Bighom, K. A. Gender differences in intestinal parasite infections in an Iranian population. Iran. J. Public. Health. 26 (1–2), 25–30 (1997).

Ahmad, H. et al. Evaluation of different diagnostic techniques for the detection of intestinal parasites in patients with Gastrointestinal symptoms. Pakistan J. Med. Sci. 31 (4), 920–924 (2015).

Parameshwarappa, K. D., Chandrakanth, C. & Sunil, B. The prevalence of intestinal parasitic infestations and the evaluation of different diagnostic techniques. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 6 (7), 1188–1191 (2012).

Neimeister, T. J. Diagnostic medical parasitology (ASM, 1987).

Knight, R. Modified formol-ether concentration technique for improved detection of schistosoma mansoni eggs. J. Parasitol. Res. 92 (5), 1120–1125 (2006).

Yamane, T. Statistics: An Introductory Analysis 2nd edn. (Harper & Row, 1967).

World Health Organization. WHO guideline on control and elimination of human schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis. World Health Organ. (2020).

Acknowledgements

The cooperation and devotion of the teams in all Schools selected for the study is very much appreciated. Their support and detection should be acknowledgment.

Funding

The research did not receive any fund from any source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SOAI conceptualized this study and data collection, AAEA, YAS, AMOA, and ASMA analysed the data, designed the tables and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. All the authors reviewed, read and approved that the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ministry of Health and Ministry of General Education. All fathers of participants provided written informed consent after being fully informed about the purpose and procedures of the study. Through the school principals, there was enlightenment for teachers, especially the supervisors of the targeted classes. Participation was entirely voluntary, and student were informed of their right to withdraw at any time without penalty or consequence. Confidentiality and privacy were strictly maintained throughout the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval was obtained from ethics committee in Shendi University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Osman, S., Ibrahim, A., Abd, A. et al. Intestinal parasitic infections among school children in Shendi, Sudan (2021–2024): prevalence, risk factors, and diagnostic comparison. Sci Rep 16, 2829 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32653-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32653-z