Abstract

Addressing the issues of manual intervention, low efficiency, and high error rates in the changeover operations of reconfigurable production lines, this paper proposes an automatic changeover task planning framework for reconfigurable production lines based on Large Language Model(LLM). Utilizing this framework, the instructions input by the user can be interpreted, and the changeover robot can be controlled to automatically complete the changeover of the production line.The framework is primarily composed of five essential components: knowledge graph, high-level task planner, low-level task planner, changeover robot, and reconfigurable production line. The knowledge graph is utilized to depict the attributes and interrelationships of products, processes, tool & fixture tool & fixture resources, and programs of the reconfigurable production line.The semantic instructions input by the user are interpreted by the high-level task planner, which then decomposes the task into changeover subtasks, matches robot skills to each subtask, and generates a sequence of skills. With the low-level task planner, the sequence of skills is translated into executable code for the changeover robot, which controls the robot to complete the automatic changeover task. A low-code industrial software is designed to implement skill-based modular programming, and the four-layer control architecture including the physical, control, skill, and application layers has been implemented. The changeover robot was designed and fabricated. Through single-robot task planning experiment and actual production line changeover task planning experiment, the correctness of the proposed changeover task planning framework is demonstrated, automatic changeover of the production line can be realized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growing trend of multi-variety and small-batch production, along with increasing product customization demands, new challenges are presented to conventional manufacturing1. Through reconfigurable flexible production line, multiple products can be produced on the same line by switching tools and fixtures2. However, most reconfigurable production lines require manual involvement for changeover, relying on human experience and resulting in low efficiency. Manual changeover also increases the risk of errors due to the high similarity of tools&fixtures across different products3. To avoid these issues, extensive validation and production ramp-up are needed after changeover, leading to significant time wastage4,5. Production line changeover task planning refers to the process of integrating the natural language description of the changeover with the production line knowledge graph to generate executable program sequences for the changeover robot6. This process utilizes the semantic understanding and high-level task planning capabilities of LLM models to interpret human natural language instructions and decompose tasks7. By integrating LLM with the knowledge graph, skill-based control language sequences for robots can be generated8,9. Once this program is downloaded into the controller software, it can direct the physical changeover robot to complete the entire production line changeover task, achieving fully automatic changeover of the reconfigurable production line.

Task planning is typically divided into two levels in current research: high-level task planning and low-level task planning10. Through high-level task planning, abstract tasks are broken down into a sequence of consecutive subtasks. Planning methods differ based on the task source. For tasks described in natural language, large language models are typically used for semantic understanding and task decomposition. The use of LLMs in manufacturing task planning represents a key advancement in automation and artificial intelligence, promising to accelerate the development of the manufacturing industry11. LLMs have been shown to plan long sequences of robotic tasks and hold great potential for precise task planning in industrial settings combined with knowledge graphs. Traditional manufacturing task planning will be completely transformed by integrating LLMs into industrial systems, reducing physical labor and boosting manufacturing efficiency12,13,14. Industrial production line changeover requires a knowledge-driven approach to intelligently generate subtask sequences that meet industrial standards. Therefore, storing industrial domain knowledge in knowledge graph as prior knowledge for LLM reasoning, the reasoning speed and accuracy of task planning by LLM can be greatly improved. The purpose of low-level task planning is to translate skills into executable programs. In industrial manufacturing, the process from skills to executable programs can be directly translated through relational mapping. In traditional production lines, these translations require manual input and program editing, with operators needing a high level of expertise15. However, to achieve automatic reasoning and program generation, knowledge graphs can be combined to assist the translation process. In summary, developing a universal LLM-based automatic changeover task planning framework for production lines is extremely urgent, and the decision-making methods for both high-level and low-level changeover task planning needs to be integrated for the framework. The framework should be capable of inferring changeover task plans that meet industrial demands and automatically completing production line changeover.

An LLM-based automatic changeover task planning framework for production lines is proposed in this paper which is composed of five parts: knowledge graph, high-level task planner, low-level task planner, changeover robot, and reconfigurable production line. The production line’s prior knowledge in four aspects: products, processes, tool & fixture resources, and skill-extracted programs for changeover robots are stored in the knowledge graph. The relationships among these four elements are also preserved. The matching of tool & fixture resources to their usage locations serves as prior knowledge for LLM task reasoning, significantly improving reasoning efficiency and accuracy. The different products can be produced through reconfigurable production line changeover and the line mainly includes production units, a central tool & fixture library, and a control system. The changeover robot is specially designed for production line changeover tasks and consists of a mobile base, a robotic arm, an end effector, and a camera. It can move between the production line and the central tool & fixture library, locate and grasp tool & fixture through visual guidance, and quickly replace them according to task instructions. The proposed task planning framework integrates the production line knowledge graph to plan tasks for changeover robots. Semantic instructions are interpreted and tasks are broken down by the high-level planner while low-level planner translates skills into low-level control instructions. By this way automatic generation of changeover programs is achieved and enabling the changeover robot to automatically complete production line changeover. The feasibility of the planning framework is demonstrated through experiments on single-robot task planning and actual production line changeover task planning. Additionally, a production line changeover software was developed based on the task planning framework.

Machine learning-based methods

The goal of task planning is to break down high-level tasks into operations that the system can execute. As a key method for converting complex tasks into specific program instructions, it enables the efficient execution of abstract tasks. Current task planning is generally divided into two levels: high-level task planning and low-level task planning. High-level task planning focuses on abstract instructions. It decomposes overall tasks and generates intermediate goals, involving task relevance, resource planning, and multi-condition constraints. It can be categorized into three types based on task origin: geometric-model input, perception-decision tasks, and user-specified tasks. Geometric-model input involves task planning based on the input of the geometric model of the product to be produced. It typically requires special processing of the part’s 3D model to obtain model parameters. The detailed physical dimensions, material, and component splitting of the part can be obtained, and the parameters include the production process and constraint relationships of each component. These parameters are used as inputs for task planning, enabling the automatic generation of task sequences for product production and allowing for the acquisition of relatively accurate subtasks16,17,18. However, this method demands operators possess 3D-model expertise, has a high usage threshold, and is unsuitable for production-line changeover tasks with numerous fixtures and tools. It is more often used in precision production task planning. Perception-decision tasks are characterized by automatically generating task planning using essential information perceived from the environment (e.g., objects to grasp and spatial poses). In the latest research, vision has been incorporated into task planning as an environmental sensor, enabling robots to autonomously plan and predict tasks based on environmental changes19,20,21,22,23. Such methods endow robots with human-like environmental perception, generally applying to vision-based task planning. In this study, vision-based guidance is used for tool & fixture positioning and grasping on the changeover robot. User-specified tasks are typically assigned through direct user-system interaction, via interfaces or direct command inputs. Task planning through machine learning is a current hot research topic. In 2021, Li J proposed a method that combines classical planning with motion planning. In high-level task planning, complex tasks are decomposed into multiple simple tasks by robots, which are then organized through logical inference to achieve the goal. In motion planning, the interaction between robots and objects is simulated using Dynamic Motion Primitives, enhancing the adaptability of robotic manipulation skills24. In 2020, Qureshi A H proposed a neural network based motion planning method, MPNet. By combining deep learning and traditional motion planning methods, it offers an efficient and versatile motion planning solution25. Sung et al.26introduced data-driven learning techniques, including model-based and model-free meta-evaluation. These techniques are suitable for various environmental distributions and are independent of specific choices of any temporal motion planners. To address issues of crowding and dynamic planning in the working environment of mobile robots, researchers focused on deep reinforcement learning, achieving long-term planning for mobile robots in complex environments. Li et al. proposed a motion planning method that integrates deep reinforcement learning with the artificial potential field approach, offering a novel solution for complex tasks involving 7-DOF robotic arms. This method enhances path planning efficiency and safety, demonstrating applicability in complex dynamic environments27. In 2023, Liu G et al. integrated reinforcement learning with traditional sampling algorithms to effectively address the challenges of nonprehensile manipulation in complex environments. This approach significantly improved the success rate of robotic operations in cluttered environments and achieved zero-shot transfer from simulation to reality. This research also offers new thoughts for future robotic autonomous operation in complex tasks, especially in scenarios requiring the coordination of multiple manipulation skills28. In 2022, Mayr M et al. integrated reinforcement learning, planning, and knowledge to improve task execution flexibility and efficiency. This method also enables robotic autonomy in complex industrial settings29. In 2025, the global path failure caused by dynamic human interventions in long-sequence robotic assembly is addressed by first hierarchically decomposing the assembly task via Petri-Nets, then estimating a human–robot contribution matrix in real time through vision and force sensing, and finally replanning the trajectory by receding-horizon optimization and quadratic programming30. A two-level task-motion planning framework is proposed, in which an optimal relocation sequence is dynamically generated at the upper level by object-weighted reinforcement learning (Q-Tree), and collision-free paths are planned at the lower level to enable efficient planning31. Machine learning based methods, though effective in task planning, require extensive scenario data for training and have limited generalization, often restricted to specific settings. However, more flexible task-planning framework in automatic production line changeover is needed. These framework must adapt to different lines and hardware while strictly adhering to industrial norms.

LLM based methods

The application of LLM in industrial scenarios has achieved certain progress and has been proven to possess immense potential in task planning, data processing, and human-computer interaction. As the technology further matures, LLM is expected to play a more crucial role in industrial automation and intelligent manufacturing. Through LLM, low-code and natural conversational interfaces are provided in industrial scenarios, breaking the limitations of traditional industrial software’s complex graphical user interfaces. By integrating LLM’s knowledge integration capabilities with industrial expertise and planning, and combining them with industrial knowledge graphs, hallucination phenomena can be significantly reduced, and more accurate task planning can be achieved. By incorporating LLM into industrial knowledge systems and utilizing its knowledge processing capabilities, industrial manufacturing processes are thoroughly transformed. New intelligent manufacturing paradigms are defined, reducing physical labor and significantly improving production efficiency. In 2024, Chen Y et al. presented Autotamp, the potential of LLMs in task and motion planning has been shown, especially in translating natural language into formal task representations. By integrating autoregressive re-prompting, this method not only enhanced task success rates but also offered a novel solution for automated complex task planning32. LLMs can be utilized in industrial production and manufacturing scenarios, demonstrating potential in task and motion planning. However, the high accuracy requirements for task planning outcomes in industrial settings necessitate further optimization. To address this issue, Xia et al. combined LLMs with domain knowledge in manufacturing, offering novel solutions for applications such as information retrieval, intelligent operations, and maintenance in the manufacturing sector. By employing error-assisted fine-tuning and a closed-loop refinement framework, the adaptability of LLMs to specific domains is significantly enhanced, laying the foundation for the future application of LLMs in real-world manufacturing scenarios33. In 2023, Ruiz et al. proposed industrial question-answering models (QA Models), which can help workers quickly obtain the information they need through natural language processing techniques, thereby enabling more efficient task guidance and decision support34. Tasks in manufacturing scenarios that are complex, have long dependencies, and are subject to multiple constraints can be planned using LLMs, which have been proven to possess the capability for high-level task planning. In 2023, Song et al. proposed Llm-planner, which aims to utilize the power of LLMs to enable few-shot planning, thereby quickly adapting to new tasks and environments. A hierarchical planning model is adopted by Llm-planner, including a high-level planner that using LLM to generate high-level plan by decomposing tasks into a series of subgoals (e.g., “navigate to the dining table and pick up the cup”) and a low-level planner that mapping each subgoal to specific actions in the current environment35. Currently, many scholars are combining real-time scene feedback from vision with large language models for robot task planning. In 2023, Huang W et al. proposed VoxPoser, a framework that combines large language models (LLMs) and vision-language models (VLMs) to create composable 3D value maps for zero-shot trajectory planning in robotic manipulation tasks36. The robots to perform tasks in complex environments is guided by mapping natural language instructions to operational targets and constraints in three-dimensional space. In 2024, Huang W et al. proposed Relational Keypoint Constraints (ReKep), a vision-and-language-model-based robotic manipulation framework designed to optimize complex robot-environment interactions through relational keypoint constraints37. The manipulation tasks as constraint functions in spatial and temporal dimensions are represented, employing a hierarchical optimization program to address robot action and perception-action loops in real time. In 2025, Patel S et al. proposed a robotic manipulation method combining the Iterative Keypoint Reward (IKER) generated by visual-language models. This approach, featuring a real-to-sim-to-real loop, enables flexible multi-step task planning and execution38. Flexible multi-step task planning and execution are enabled through a real-to-simulation-to-real loop. A “perception-reasoning-execution” closed-loop framework is proposed, in which natural-language instructions and visual observations are fused by multimodal GPT-4 V to enable task decomposition, object detection, and motion planning39. An end-to-end “language-vision-grasp” framework is proposed, in which textual descriptions of “graspable parts” are first generated by GPT-4 from natural-language prompts, the corresponding regions are zero-shot localized in RGB-D images by OWL-ViT, and semantic grasping is finally executed by the robotic arm40.

Methods combining knowledge graph and LLM

In industrial manufacturing task planning, ensuring task feasibility and accuracy is crucial. Large models must incorporate industrial knowledge systems to generate compliant tasks. Combining knowledge graphs with large models can address the hallucination problem. Through large models, standardized and industrially compliant tasks can be inferred. The production line’s knowledge graph stores information such as products, processes, fixtures, robot skills, and control programs, as well as standards for auto-program generation. Through these information cues, the current production line’s characteristics and resource situation can be learned by LLM, especially the central fixture library related to changeover and the fixture-product correspondence. Despite LLM’s strong generalization ability, task plans cannot be generated without knowledge-graph-based specific production line information. Thus integrating knowledge graphs with LLMs is a current research hotspot in industrial settings.

In 2024, Liu et al. proposed an efficient long-term robotic task planning method combining LLMs and scene graphs, addressing the issue of LLMs generating infeasible plans due to hallucination or lack of domain information41. In 2025, Feng Y et al. proposed a knowledge graph-based thinking (KGT) framework to enhance LLMs’ accuracy in biomedical question answering. LLMs integrated with knowledge graphs by KGT, using graph-pattern reasoning and subgraph retrieval to reduce factual errors in LLMs’ outputs. Experiments show LLMs’ performance in biomedical QA is significantly improved, especially in drug repurposing and predicting drug resistance42. In 2024, Liu H et al. proposed the Knowledge Graph-Enhanced Large Language Models via Path Selection (KELP) framework. The LLMs’ factual inaccuracies in output generation is addressed by extracting, encoding, and selecting refined paths to incorporate latent useful knowledge from knowledge graphs into LLMs’ context, thereby improving the accuracy of generated content43. In 2025, A “perception-mapping-planning” pipeline is proposed, in which a semantic 3D scene graph is first constructed and then fed into SayNav-LLM, through which a sub-goal sequence and an executable path are generated via zero-shot prompting44. In 2024, Shu D et al. proposed a new framework called KG-LLM for multi-hop link prediction in knowledge graphs using LLMs. Knowledge graphs are transformed into natural language prompts, enabling LLMs to better understand and learn the underlying representations of entities and their relationships within knowledge graphs45.

While these studies have integrated knowledge graphs with LLMs to achieve initial results, they focus on generalized frameworks and QA systems, lacking direct task planning capabilities for industrial manufacturing. Task planning for industrial settings must generate compliant plans and programs based on actual production resources, especially considering the stability and accuracy of equipment-operation programs. Thus, automated programs need to be checked and confirmed before being deployed on real equipment to ensure regulatory compliance.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: The Method section mainly explains the overall framework of task planning based on knowledge graphs. The Application chapter mainly introduces the specific implementation methods of each module and the experimental results of production line changeover. The Conclusion Section concludes the study with a summary.

Methods

Overview

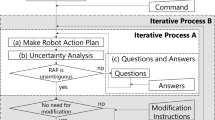

The production line changeover task planning framework based on large language models consists of five modules: knowledge graphs, a high-level task planner, changeover robots, a low-level task planner, and a reconfigurable production line, as shown in Fig. 1. The LLM-Tasks-Subtasks-Skills format is adopted by core architecture. This framework enables the effective translation from human high-level semantics to specific changeover programs, supports new product introduction, and effectively realizes fully automatic production line changeover. The human continuous semantic instructions can be adapted by this framework. For example, when a user inputs “produce 10 product A, then 20 product B”, it combines with the knowledge graph to first reconfigure the production line for product A based on the current line status and starts counting. Once production of the 10 A products are completed, the system automatically reconfigures to produce B products and starts counting. Customer orders can be directly issued to the production line reconfiguration system as high-level semantic instructions. The line reconfiguration and on-demand production can be automatically completed by this system.

The production line’s specific information and knowledge are preserved in the knowledge graph, which serves as an effective reference for the entire changeover task planning and LLM reasoning, making it the most crucial part of the changeover system. To adapt to variations in production line hardware and products, a knowledge graph is proposed. It includes four types of knowledge: product, process, resources, and programs, along with their interrelationships in changeover tasks. The information such as the geometric characteristics and codes of production products are stored in knowledge graph. The process description outlines the product manufacturing process, covering the work units and their attributes, as well as the tools&fixtures needed for each operation. Information on production line work units, tool & fixture libraries, fixtures, and changeover robots is stored in the resource module. Given the prior knowledge, if product information is known, the product’s process, production units, and required tools&fixtures can be obtained through knowledge reasoning. The basic knowledge required for LLM-based changeover task decomposition and skill generation can be obtained through this approach. The mapping between the changeover robot’s skills and the lower-level physical control layer is stored in the program module. The inferred changeover skill sequence can be transformed into executable programs for the changeover robot.

To address small-batch and multi-variety production demands and solve the problem of frequent changeover on the production line, production lines must achieve fully automatic changeover with different resources for each product. As shown in the high-level task planner in Fig. 1, LLM is introduced to understand instructions and combine with knowledge graphs for task splitting and skill matching. First, knowledge related to user instructions is extracted from the production line knowledge graph, then the user instructions and the knowledge paths are encoded. Knowledge paths highly relevant to the problem are obtained through a knowledge path selection method based on latent semantics and are inputted into the LLM together with the user’s instructions. Based on the prompt, a changeover subtask sequence is generated by LLM. Each subtask is then transformed into a skill combination for the changeover robot, drawing on the skills stored in the knowledge graph. For instance, if the user inputs the instruction “Please help me replace tool1 with tool2”, the first subtask generated by the LLM is: “Return tool1 to its storage location”, the second subtask is: “Retrieve tool2 and place it at the production line position”.

The received skill sequence is converted into an executable program for the changeover robot by the low-level task planner. Based on the characteristics of the changeover robot’s operations, its main skills include: Pick and place, Photograph and locate, Navigate to position, and Scan and confirm. A skill-based robotic control architecture is proposed, which is composed of the physical layer, control layer, skill layer, and application layer. The robot’s skills and parameters are translated into actions at the control layer, which directly control the physical layer’s devices to execute the skill movements via action commands. Through this architecture, the skill sequences planned by the high-level task planner can be automatically converted into control programs for physical devices, enabling adaptive generation of reconfigurable production line changeover programs.

Knowledge graph

The knowledge graph of reconfigurable production lines consists of four parts: products, processes, resources, and programs. The relationships between these parts and all information needed for line changeover are stored in knowledge graph. As the knowledge base for the entire changeover task planning process, the knowledge graph is utilized in LLM task decomposition, LLM skill matching, and executable program generation. The knowledge ontology of the constructed knowledge graph is shown in Fig. 2.

The production target of a reconfigurable production line is the product. The knowledge graph mainly includes subtask allocation, components, and production features. The production processes and the types of tools&fixtures needed can be inferred from the production characteristics. The detailed product manufacturing process is preserved by the process, including operations and steps. An operation consists of multiple steps, which include start step, operational step, and end step. Information on production units, their sequence, and the tools&fixtures used in each unit is obtained through the characteristics of operations and work steps. This enables the creation of a list of production resources needed for the product. Resources describe the production units, quick-change positions, tools&fixtures, their positions, and libraries of the reconfigurable production line. They include basic information of all production units, quick-change positions and attributes of each unit, central tool & fixture library details, attributes of each storage position, corresponding tool & fixture information, and basic information of all tools&fixtures on the line and their correspondence to production units. Resource information provides prior knowledge for changeover, enabling the acquisition of tool & fixture positions and storage locations. It offers positioning and photography point information for changeover robots. Programs mainly consist of the changeover robot’s skills and the control codes mapping these skills to the physical layer. The changeover robot’s skills mainly consist of Pick and place, Navigate to position, Photograph and locate, and Scan and confirm, corresponding to its robotic arm, AGV base, vision camera, and scanner. Each skill has executable control codes that directly command the physical devices to accurately perform tasks.

The knowledge graph of the reconfigurable production line is denoted as KG, defined as G = {E, R, F}, where E represents the set of entities, R represents the set of relations, and F is defined as the set of knowledge triplets; F = {(h, r, t)| h, t∈E, r∈R}, h and t represent entities, serving as the head entity and tail entity, respectively, while r denotes the relationship between them. The pre-trained LLM is defined as LM, and the user’s input command is defined as C, the set of all entities in C is defined as Ec. Planning the production line changeover task involves finding the most suitable knowledge path in the knowledge graph Ec based on the user’s instruction C to prompt the LM. The task planning and matches tasks for the changeover robot based on this prompt are generated by LM.

High-level task planner

The high-level task planner uses LLM to comprehend user instructions, decomposes tasks based on knowledge graph prompts, and converts subtasks into combinations of changeover robot skills using skill descriptions from the knowledge graph. First, according to the user’s input instructions, valuable knowledge paths are sought in the knowledge graph. These paths must have a latent semantic association with the input instruction C. They can serve as contextual prompts to enhance the accuracy and stability of the LLM generation process. For each entity in, extract knowledge paths related to the entity from the knowledge graph, as shown in formula 1.

As shown in Formula 1, one-hop and two-hop knowledge paths are extracted for each entity in instruction C. This ensures that the extracted knowledge paths contain sufficient information related to the user’s instruction, serving as input for subsequent encoding. The input instruction with the extracted knowledge paths are compared by encoding. The extracted paths are refined to help the LLM provide more precise reasoning for instruction C. Specifically, the user instruction C and the extracted knowledge paths are encoded by a latent semantic encoder. This encoding allows for the quantification of the usefulness of each knowledge path. To adapt to the pretrained encoding standards of the encoder, the extracted knowledge paths related to user instructions are transformed into path sentences. The transformation rules are based on the number of triplets in the knowledge paths. The specific transformation rules are as follows: If a knowledge path contains only one triplet (h, r, t), the path sentence is defined as S′ = “h r t”; If a knowledge path contains two triplets, (h1, r1, t1) and (h2, r2, t2), the path sentence is written as \(S^{\prime} =\) “\(h_{1} r_{1} t_{1} ,h_{2} r_{2} t_{2}\)”. An encoder is applied to encode user instruction C and knowledge path \(S^{\prime}\), resulting in hC and hS respectively, as shown in formula 2.

Encoded results hc and hS can be used to select knowledge paths close to user commands via semantic similarity and analyze the potential semantic links between them quantitatively. After encoding the user instructions and relevant knowledge paths, the next step is to find the most suitable knowledge path for LLM reasoning based on semantic similarity. Cosine distance is used to quantify the distance between knowledge paths and user semantic instructions. The inflexibility in path selection is addressed by this approach. By adjusting hyper-parameter values in the rules, the diversity and number of selected paths are controlled. The specific approach involves including all paths of entities in\(\:{\:E}_{c}\) and representing them as a set:\(P_{c} = \bigcup\nolimits_{{e \in E_{c} }} {P_{e} }\). By following the above reasoning process, it can be observed that \(\:{P}_{C}\) contains numerous repeated knowledge triples. Thus, it is necessary to eliminate paths with duplicate triples to facilitate the final selection. First, \(\:{\:P}_{C}\) is decomposed into different subsets based on whether the paths contain the same specific triples. The collection of paths sharing the same specific triple (h, r, t) is defined as follows: \(P_{c} (h,r,t) = \left\{ {\left. S \right|(h \to r \to t) \subset S,S \in P_{q} } \right\}\); The specific computation process is shown in formula 3.

The above formula needs to satisfy both conditions\(\left| {P_{C}^{\prime } (h,r,t)} \right| = W_{1}\)and\(P_{C}^{\prime } (h,r,t) \subset P_{C} (h,r,t)\). The size of the knowledge path subset is controlled by W1. Adjusting the W parameter can flexibly control the number of selected knowledge paths. This prevents selecting multi-hop paths with the same triple and avoids redundant context prompts. \(P_{C}^{\prime } (h,r,t)\) is a subset of \(P_{C} (h,r,t)\),representing the top W1-scoring knowledge paths with specific triples. To further constrain redundancy in the prompt information, another restriction rule is developed, as shown in formula 4.

The above formula needs to satisfy \(\left| {\psi ^{\prime}} \right| \le {\text{W}}_{2}\); \({\psi ^{\prime}}\)denotes the collection of top-scoring subsets of triples that are shared. By calculation, the triple subset most relevant to the question can be selected, and the size of \({\psi ^{\prime}}\)is constrained by W2. The aggregated knowledge paths of \({\psi ^{\prime}}\)can be represented as:

By controlling the size of \({\psi ^{\prime}}\), irrelevant knowledge paths can be effectively reduced. This ensures the extracted paths are strongly related to the instruction, without redundant context, providing a factual basis for subsequent LLM reasoning. As shown in Fig. 3, the user’s instruction is “Please help me replace tool1 with tool2”. Many knowledge paths related to the tool1 and tool2 entities can be obtained from the production line knowledge graph. Through Encoder and path selection, the four triples most relevant to the user’s instruction can be selected as the context prompt for LLM, providing highly relevant factual basis for LLM to generate subtasks. These triples include the current positions of tool1 and tool2, as well as their storage locations in the tool library.

As shown in Fig. 3, the reasoning of the large model is divided into two phases. The first phase is to filter out strongly related knowledge paths based on user instructions and generate a sub-task sequence. The second phase is to generate a plan function for the changeover robot based on skills API, according to the prompt and the sub-task sequence. Taking the user instruction “Please help me replace tool1 with tool2” as an example, the LLM generates sub-task 1: “Grab Tool 1 from P1 and place it to the tool library” and sub-task 2: “Grab tool 2 from the tool library and place it to P1” based on the positions of tool1 and tool2. Since the tasks in the LLM fine-tuning phase are divided into subtasks based on single entities, the LLM-generated subtasks are also distinguished by tool1 and tool2. Then, the LLM combines these subtasks with the changeover robot’s skills API to generate the plan function, which is described as follows: Navigate to position(p), based on the input coordinates p, the robot can be navigated to the target point P, which is used to control the movement of the robot chassis; Photograph and locate(pose), it indicates that the robotic arm can move the camera to the pose position. The position can call the photo position attribute of the navigation point P to obtain P.photoposition, take photos of the object, and locate the object’s position. The returned data type is pose = {“translation”: [x, y, z], “quaternion”: [w, x, y, z]}༛Pick and place(pose), it indicates that the robotic arm’s end-effector moves to the pose position to grasp the object and then places it at another position. The prompt “You are now a module for generating skill codes for the changeover robot, the APIs of changeover robot can be directly called. Please implement only the code plan() function in Python based on the API. “Only output the code and do not need to output any other descriptions” is used to restrict and standardize the output of LLM, ensuring it only includes calls to the changeover robot API functions. As shown in the figure, the entire skill-based plan function for changeover can be correctly generated by LLM. After translation, the script calls the underlying control code, enabling precise control of the changeover robot. This allows the robot to automatically complete tasks based on user instructions.

Low-level task planner

The low-level task planner receives the skill sequence from the high-level task planner, translates the skills into code executable by the tool-changing robot, and controls the robot to complete the automatic changeover task. Like a human cerebellum, the low-level task planner directly interfaces with physical-layer devices, enabling precise control and task execution of actual equipment based on instructions.

Skill extraction

Skills are abstracted based on the characteristics of the execution device. Skills are often encapsulated by multiple low-level control commands in a specific order. Skill extraction for changeover robots enables controlling their AGV chassis, robotic arm, vision camera, and end effector. The changeover robot comprises four main skill types: Navigate to position, Photograph and locate, Pick and place, Scan and confirm. Navigate to position is used to control the AGV chassis of the changeover robot. The chassis, equipped with a LiDAR, navigates and positions using SLAM technology, allowing it to reach any location on the pre-scanned map based on input coordinates. The changeover robot can move between different production stations and the central tool & fixture library by using this skill, enabling adaptive obstacle avoidance during movement. Using the “Photograph and locate” skill, the robot’s visual photography and positioning are enabled. Since the camera is mounted at the end of the robotic arm (eye-in-hand), the arm must first move to the shooting position with the camera. Object recognition and grasping position calculation are achieved through images captured by a 3D camera, which ultimately provides the actual grasping points and posture of the object. This skill enables the changeover robot to perceive its environment, allowing it to visually identify the category and position of objects to be grasped. The results of hand-eye calibration are used to transform visual coordinates into the robotic arm coordinate system, enabling precise object grasping with the robotic arm. The Pick and place skill enables the control of the robotic arm to perform grasping and placing actions, and also allows for the control of the robotic arm’s end effector opening and closing to achieve object grasping and placement. RFID recognition and confirmation are achieved using the Scan and confirm skill. The tool & fixture of the reconfigurable production line are equipped with RFID modules, and an RFID reader is installed at the end of the robotic arm to read the ID numbers of the currently grasped tool & fixture. These ID numbers are compared with those in the user’s instructions to ensure the accuracy of the grasped tools.

After the design of skill extraction is completed, underlying control commands must be implemented for each skill. The specific correspondence between skills and lower-level control codes is shown in Table 1. The table provides a detailed list of the underlying control commands invoked by the four commonly used skills of the changeover robot. These control commands are basic instructions that can directly control physical devices. The rightmost column explains some commands: P represents the navigation point of the AGV’s target point. pi and pj are predefined positions for robotic arm movement, specified in skill inputs. height1 and height2 are fixed height thresholds for grasping and placing, ensuring the accuracy of these actions.

Design of the control architecture

To achieve precise control of the changeover robot’s physical modules, a four-layer skill-based control architecture is designed, as shown in Fig. 4. The architecture mainly consists of four layers: physical layer, control layer, skill layer, and application layer. The physical layer comprises collaborative robotic arms, cameras, AGVs, end effectors, and RFID readers, which are actual physical devices. The control layer communicates with physical devices and controls them using basic commands. The skill layer extracts and encapsulates the changeover robot’s skills, each consisting of multiple low-level control commands. The application layer enables user interaction by providing a manual programming interface to directly call skill modules for editing the changeover robot’s task sequence. Additionally, it allows the automatic changeover framework proposed in this paper to generate and execute task workflows based on the user’s semantic instructions. Through this four-layer control architecture, automated task planning and precise control of the changeover robot are achieved, establishing a skill-based robotic control method that provides the necessary foundation for LLM task generation. The robot controller is in the control layer, linked to the chassis, arm, and camera via Ethernet, and to the RFID reader via serial port. It hosts integrated control software with basic device commands. These commands are encapsulated into skill modules, enabling drag-and-drop task flow editing with parameter settings on the software interface.

Application

Using a product assembly line as the experimental subject, an industrial software platform has been established. The changeover robot was designed and fabricated, with a detailed introduction of its structure and principles. The training of LLM is implemented, and the practical application process of the changeover task planning framework is demonstrated. The changeover robot is applied in both single-machine and production-line scenarios to validate the effectiveness of the proposed automatic changeover task planning framework. An application software based on the four-layer control architecture has been developed for the automatic changeover planning framework. This software significantly reduces the complexity of changeover task programming and offers a visualized task process. A human-machine interaction interface is provided, which allows for autonomous programming based on skill modules, and enables setting parameters and querying the operational status of equipment.

Industrial software platform

To implement the control architecture, an industrial software platform for industrial production lines and equipment control has been designed. The software implements the four-layer control architecture and the skill encapsulation of the changeover robot. First, the changeover robot’s robotic arm, camera, and AGV are connected to the controller via Ethernet. The RFID reader is connected to the controller via a serial port. The IO is connected to the controller through a remote IO module, and the end effector gripper is also controlled via IO. The software has implemented four skill modules of the changeover robot: Navigate to position, Photograph and locate, Pick and place, and Scan and confirm. The effectiveness of each skill is verified through manual programming. Industrial software provides a custom process function, which can read local python files for operator combinations and parameter settings. It can read skill-based plan functions auto-generated by LLM and convert them into executable processes, thereby enabling the control of changeover robots. The plan function for the task “Please help me replace tool1 with tool2” is retrieved, and the generated operator process is shown in Fig. 5.

Users can manually drag operators from the step library for programming or automatically load Python files to generate program flows. After automatically generating the execution process, the input and output of each operator module are checked by the software. This approach allows for seamless parameter interaction between operators and? ensures smooth and correct task execution. During program execution, each operator monitored by the software in real-time using a finite state machine to control execution. The execution status and frequency of each operator recorded by the state list.

Design of changeover robot

The changeover robot, serving as the actuator for automatic changeover tasks, executes the skill sequence planned by the high-level task planner. The changeover robot is composed of a movable chassis, a six-axis collaborative robotic arm, a RFID scanner, a 3D industrial camera, an end effector, and a control cabinet, as shown in the Fig. 6.

The end effector is installed at the end of the sixth axis of the robotic arm. The collaborative robotic arm mainly performs grasping and placing operations. The precise grasping and placing of objects are achieved based on the coordinates from visual localization, and the robotic arm has an effective payload of 10 kg. A pneumatic cylinder mechanism is used by end effector, and the gripper features a locating pin design. This ensures secondary positioning accuracy during the grasping and placing of tools and fixtures. The point clouds of objects are captured by the 3D camera via photography which is based on a binocular structured light system. Object recognition and localization are performed using point cloud registration algorithms. The object’s 6D pose relative to the camera coordinate system is calculated through visual localization. Using the hand-eye calibration results, this coordinate is transformed into a 6D pose relative to the robotic arm’s base coordinate system, enabling precise object grasping with the robotic arm. The measured grasping accuracy is less than ± 0.2 mm. Two LiDARs are mounted diagonally at 45 degrees on the AGV chassis for mapping and navigation. During the deployment of the changeover robot, LiDAR is used to scan and map the surrounding environment of the production line. Important sites, such as the changeover station and central fixture library station, are marked on the map. During the operation of the changeover robot, SLAM technology is employed for navigation, allowing it to navigate to any site on the map, with the measured navigation and positioning accuracy being less than ± 5 mm. By means of a dual-LiDAR design, 360-degree all-round obstacle avoidance of the AGV is realized. When encountering obstacles, the AGV can automatically bypass them, thus ensuring the safety and stability during its operation. The controller is mounted in the control cabinet, and the camera, manipulator, and AGV chassis are connected to it. Real-time control is realized via low-level control commands. Through the above-mentioned design, the changeover robot can be precisely navigated to any point around the production line via the AGV chassis. Object recognition and positioning are achieved through camera-captured images. Finally, grasping and placement operations are executed by the manipulator. The functional requirements for production line changeover of the changeover robot are met, and it can completely replace manual labor to automatically carry out changeover tasks.

LLM fine-tuning

In this section, detailed settings of fine-tuning of LLM and the changeover task planning framework are introduced. “gpt-3.5-turbo-0613” is employed as the LLM for the changeover task framework. It is an enhanced version of the GPT-3 series. During the construction of the task-framework training dataset, the tasks are categorized according to the number of skills they involve and relevant data is built accordingly. 5000 task data entries involving two transformation robot skills are constructed, such as grasping tool1. 8000 task data entries involving more than two changeover robot skills are constructed, such as “Please help me replace tool1 with tool2”. The data also contains instructions for production switching, such as “Please help me switch to the production of product B “. For knowledge graph path selection, the DistilBert pre-trained model is chosen as the Encoder, which contains 66 million parameters. These parameters are used to encode knowledge paths to determine whether they potentially semantically correlate with the input instructions. AdamW is used as the optimizer, with the learning rate set to 2 × 10 − 6. According to the structure of the transformation task knowledge graph and the characteristics of task planning, the covering rules are set with W1 = W2 = 4. During the training phase, cross-entropy is utilized as the loss function L. The loss is calculated by measuring the discrepancy between the probabilities of the model-predicted tokens and those of the actual tokens in the expected output sequence. In the equation below, n denotes the length of the expected output sequence, x represents the input instruction, and yi stands for the i-th token in the expected output sequence. We trained LLM model for 50 epochs on an A100 GPU.

Task planning experiment for changeover robot

Experiments on single-vehicle task planning are conducted after the design of the changeover robot to verify its performance and the effectiveness of the task-planning framework. Experimental settings are as shown in Fig. 7. A tape measure, screwdriver, and hammer are used as grasping objects, each having a designated storage location. The console simulates the placement positions of tools on the production line. By inputting voice commands like “Please take out the tape measure, put back the screwdriver, and take out the hammer”, the planning framework can break down the commands, automatically generate motion instructions for the changeover robot, and control it to accurately pick and place materials. The knowledge graph stores the storage locations of each tool, their visual templates and photo-taking positions, and the simulated placement positions of each tool on the control platform. The software uses the low-code industrial software designed in the chapter on Industrial software platform. It includes the skill encapsulation of the changeover robot and can translate skills into control commands for lower-level devices. As shown in Fig. 8, experiments on picking up and placing down the tape measure, screwdriver and hammer in different orders are presented. The experimental results show that the changeover tasks can be accurately decomposed by changeover task planning framework. It also demonstrates that the changeover robot can generate skill-based robot control programs according to the sub-tasks generated by the framework, thereby achieving precise robot control. Experiments demonstrate that skill-based robot control programs for the changeover robot can be generated based on sub-task sequences from the high-level task planner, and precise robot control can be achieved.

As shown in Table 2, experiments on the success rate of task planning for the changeover robot are carried out. Single-entity commands, dual-entity commands, and multiple-entity commands refer to the number of entities included in the transformation commands. For example, a single-entity command can only contain one entity such as a tape measure, screwdriver, or hammer. One hundred transformation task plans are carried out for each command type, and the results are shown in Table 2. The success rates of single-entity and dual-entity commands are both 100%, while multi-entity commands have one placement failure. The failure case is analyzed. The sub-task decomposition and skill adaptation are correct. The visual template of the “Photograph and locate” skill fails to match the tape measure, causing a failure in its visual location. The tape measure template is recalibrated, and a mechanism is added to take two more photos if visual capture fails. No further visual capture failures have occurred. The experimental results in the table show that the proposed changeover task planning framework can decompose changeover commands and match skills. Combined with industrial control software, it can accurately generate work programs for the changeover robot.

Production line changeover task planning experiment

The changeover robot is applied to the actual production line, and the changeover task framework is verified with actual changeover tasks from the production line. The designed reconfigurable production line can perform flexible assembly of workpieces. It comprises 10 assembly units. Each unit is equipped with a quickly changeable tool hardware interface and a secondary positioning table. By transforming the production line, it supports the production of 11 kinds of products. Line-side logistics are used to transport materials between units. After each workstation completes its assembly task, materials move forward one unit to continue with the next assembly process. The production line consists of assembly units, a central tool & fixture library, and a changeover robot, with its specific structure shown in Fig. 8.

Changeover of the production line is carried out by the changeover robot based on the operator’s commands, thereby achieving automatic changeover of the production line without human involvement. The changeover task planning framework is experimentally verified on the production line. Using the methodin the chapter on knowledge graph, knowledge graphs for 11 kinds of products are built by incorporating their assembly SOP, production process, and tooling resource. The central tool & fixture library structure, changeover positions, correspondences between tool & fixture, and correspondences of production line changeover positions are entered into the knowledge graph in advance. As shown in Fig. 9, experiments are conducted on randomly selected products from the 11 types for production changeover.

As shown in Fig. 9, the changeover robot can automatically reconfigure the production line based on the operator’s instructions and enable unattended production of different products. Over three months, the production line operated stably with 81 successful changeover operations. The changeover task planning framework based on LLM is proven feasible. The automatically generate programs for the changeover robot and automatic production line changeover are achieved.

Conclusion

Aiming at the problems of manual participation, low efficiency, and frequent errors in product changeover of reconfigurable production lines, a framework for changeover task planning based on LMM is proposed. The main contributions are as follows:

A changeover task planning framework based on LLM is proposed. It consists of five key modules: knowledge graph, high-level task planner, low-level task planner, changegover robot, and reconfigurable production line. The knowledge graph stores product, process, resource, and center tool & fixture library information related to changeover tasks. The high-level task planner uses fine-tuned LLM to understand operator commands, decompose changeover commands into sub-tasks, and generate skill sequences based on the changeover robot’s skills. The skill sequences are translated into executable programs for the transforming robot by low-level task planner.

A low-code industrial software for users is developed, achieving the four-layer control architecture. A skill-based modular programming software is created. It can read the python skill sequences generated by the high-level task planner and convert skills into control commands for lower-level physical devices. Skill addition and editing are supported, and changeover commands can be issued via the software interface. This software conveniently enables automatic generation of changeover programs.

The changeover robot was designed and constructed. Experiments on its task planning verified the effectiveness of the task-planning framework. The changeover robot consists of an AGV chassis, collaborative manipulator, 3D camera, end-effector, and control cabinet. Experiments on its tasks have verified the effectiveness of its functions and demonstrated that the skill-based control architecture can automatically generate programs for the changeover robot. The changeover task planning experiments have verified the effectiveness of the changeover robot’s functions and demonstrated that the skill-based control architecture can achieve automatic program generation for the transforming robot.

The effectiveness of the proposed framework for changeover task planning based on LLM is verified by the production line changeover experiment. Compared to manually coding changeover programs, the time required for task planning and programming is significantly reduced by the proposed automatic changeover task planning framework. A novel approach for changeover in reconfigurable production lines is proposed, which resolves human-induced errors in manual changeover. Through the utilization of this framework, the operational efficiency of the production line has been enhanced, while costs have been reduced, and efficiency has been improved.

Data availability

All data, models, and code generated or used during the study are available from the corresponding author uponreasonable request.

References

Yelles-Chaouche, A. R. et al. Optimizing modular equipment in the design of multi-product reconfigurable production lines[J]. Comput. Ind. Eng. 192, 110226 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Smart reconfigurable manufacturing: literature analysis[J]. Procedia CIRP. 121, 43–48 (2024).

Osman, M. S. A computational optimization method for scheduling resource-constraint sequence-dependent changeovers on multi-machine production lines[J]. Expert Syst. Appl. 168, 114265 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Architecture Design of Flexible Production Line Control System for Reconfigurable Operations and Maintenance[C]//2024 3rd International Conference on Cloud Computing, Big Data Application and Software Engineering (CBASE). IEEE, : 880–883. (2024).

Vieira, M. et al. A two-level optimisation-simulation method for production planning and scheduling: the industrial case of a human–robot collaborative assembly line[J]. Int. J. Prod. Res. 60 (9), 2942–2962 (2022).

Feng, B., Wang, Z. & Dai, X. Task planning for Dual-Arm robot empowered by large Language Model[C]//2024 China automation Congress (CAC). IEEE, : 3896–3901. (2024).

Kau, A. et al. Combining knowledge graphs and large Language models[J]. (2024). arxiv preprint arxiv:2407.06564.

Liang, X. et al. A survey of LLM-augmented knowledge graph construction and application in complex product design[J]. Procedia CIRP. 128, 870–875 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. An LLM supported approach to ontology and knowledge graph construction[C]//2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM). IEEE, : 5240–5246. (2024).

Xu, Z. et al. Reconfigurable flexible assembly model and implementation for cross-category products. J. Manuf. Syst. 77, 154–169 (2024).

Waseem, M. et al. Pretrained LLMs as Real-Time controllers for robot operated serial production Line[J]. (2025). arxiv preprint arxiv:2503.03889.

Xia, Y. et al. Towards autonomous system: flexible modular production system enhanced with large language model agents[C]//2023 IEEE 28th International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA). IEEE, : 1–8. (2023).

Zhou, Z. et al. Isr-llm: Iterative self-refined large language model for long-horizon sequential task planning[C]//2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, : 2081–2088. (2024).

Kannan, S. S., Venkatesh, V. L. N. & Min, B. C. Smart-llm: Smart multi-agent robot task planning using large language models[C]//2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, : 12140–12147. (2024).

Epureanu, B. I. et al. An agile production network enabled by reconfigurable manufacturing systems[J]. CIRP Ann. 70 (1), 403–406 (2021).

Michniewicz, J. & Reinhart, G. Cyber-Physical-Robotics –Modelling of modular robot cells for automated planning and execution of assembly tasks. Mechatronics 34, 170–180 (2016).

LIU Daxin, W. K., Zhenyu, L. I. U., jiatong, X. U. & TAN Jianrong. Research on digital twin modeling method for robotic assembly cell based on data fusion and knowledge reasoning. J. Mech. Eng. 60, 36–50 (2024).

Lee, R. K. J., Zheng, H. & Lu, Y. Human-Robot shared assembly taxonomy: A step toward seamless human-robot knowledge transfer. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 86, 102686 (2024).

Mei, A., Zhu, G-N., Zhang, H. & Gan, Z. ReplanVLM: replanning robotic tasks with visual Language models. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 9, 10201–10208 (2024).

Mikita, H., Azuma, H., Kakiuchi, Y., Okada, K. & Inaba, M. Humanoids. Interactive symbol generation of task planning for daily assistive robot. 2012 12th IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots 2012:698–703. (2012).

Gu, Q. et al. ConceptGraphs: Open-Vocabulary 3D Scene Graphs for Perception and Planning. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA)2024:5021-8.

Xie, Z., Zhang, Q., Jiang, Z. & Liu, H. Robot learning from demonstration for path planning: A review. Sci. China Technological Sci. 63, 1325–1334 (2020).

Fang, B. et al. Survey of imitation learning for robotic manipulation. Int. J. Intell. Rob. Appl. 3, 362–369 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Integrated Classical Planning and Motion Planning for Complex Robot Tasks[C]//Intelligent Robotics and Applications: 14th International Conference, ICIRA 2021, Yantai, China, October 22–25, 2021, Proceedings, Part II 14. Springer International Publishing, : 70–78. (2021).

Qureshi, A. H. et al. Motion planning networks: bridging the gap between learning-based and classical motion planners[J]. IEEE Trans. Robot. 37 (1), 48–66 (2020).

Sung, Y., Kaelbling, L. P. & Lozano-Pérez, T. Learning when to quit: meta-reasoning for motion planning[C]//2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, : 4692–4699. (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Constrained motion planning of 7-DOF space manipulator via deep reinforcement learning combined with artificial potential field[J]. Aerospace 9 (3), 163 (2022).

Liu, G. et al. Synergistic task and motion planning with reinforcement learning-based non-prehensile actions[J]. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 8 (5), 2764–2771 (2023).

Mayr, M. et al. Skill-based multi-objective reinforcement learning of industrial robot tasks with planning and knowledge integration[C]//2022 IEEE international conference on robotics and biomimetics (ROBIO). IEEE, : 1995–2002. (2022).

Ma, W. et al. Human-aware Reactive Task Planning of Sequential Robotic Manipulation Tasks[J] (IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 2025).

Golluccio, G. et al. Objects relocation in clutter with robot manipulators via tree-based q-learning algorithm: analysis and experiments[J]. J. Intell. Robotic Syst. 106 (2), 44 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Autotamp: Autoregressive task and motion planning with llms as translators and checkers[C]//2024 IEEE International conference on robotics and automation (ICRA). IEEE, : 6695–6702. (2024).

Xia, L. et al. Leveraging error-assisted fine-tuning large Language models for manufacturing excellence[J]. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 88, 102728 (2024).

Ruiz, E., Torres, M. I. & del Pozo, A. Question answering models for human–machine interaction in the manufacturing industry[J]. Comput. Ind. 151, 103988 (2023).

Song, C. H. et al. Llm-planner: Few-shot grounded planning for embodied agents with large language models[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. : 2998–3009. (2023).

Huang, W. et al. Voxposer: composable 3d value maps for robotic manipulation with Language models[J]. (2023). arxiv preprint arxiv:2307.05973.

Huang, W. et al. Rekep: Spatio-temporal reasoning of relational keypoint constraints for robotic manipulation[J]. (2024). arxiv preprint arxiv:2409.01652.

Patel, S. et al. A Real-to-Sim-to-Real approach to robotic manipulation with VLM-Generated iterative keypoint Rewards[J]. (2025). arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.08643.

Wang, J. et al. Large Language models for robotics: Opportunities, challenges, and perspectives[J]. J. Autom. Intell. 4 (1), 52–64 (2025).

Mirjalili, R. et al. Langrasp: Using large language models for semantic object grasping, 2024[J]. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.05239

Liu, Y. et al. Delta: decomposed efficient long-term robot task planning using large Language models[J]. (2024). arxiv preprint arxiv:2404.03275.

Feng, Y. et al. Knowledge graph–based thought: a knowledge graph–enhanced LLM framework for pan-cancer question answering[J]. GigaScience 14, giae082 (2025).

Liu, H. et al. Knowledge Graph-Enhanced Large Language Models via Path Selection[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.13862, (2024).

Shan, T. et al. Graph2nav: 3d object-relation graph generation to robot navigation[J]. (2025). arxiv preprint arxiv:2504.16782.

Shu, D. et al. Knowledge graph large Language model (KG-LLM) for link prediction[J]. (2024). arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.07311.

Funding

Funding was provided by Shaanxi Qinchuangyuan “Scientists + Engineers” Team Construction Project, Grant No. 2025QCY-KXJ-048.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Y.; methodology, L.Y. and J.H.; sofware, J.H.; validation, J.H. and H.Q.; formal analysis, J.H. and H.Q.; investigation, L.Y. and J.H.; resources, L.Y. and J.H.; data curation, J.H. and H.Q.; writing—original draf preparation, J.H. and H.Q.; writing—review and editing, L.Y. and J.H.; visualization, H.Q.; supervision, L.Y.; project administration, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, J., Yan, L. & Qiang, H. A framework for reconfigurable production line changeover task planning based on large language model. Sci Rep 16, 2884 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32657-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32657-9