Abstract

Discotic liquid crystals (DLCs) are emerging as versatile functional materials with significant potential for optical and sensing applications. Their photophysical behavior is highly sensitive not only to solvent polarity but also to molecular asymmetry and environmental factors such as viscosity and hydrogen-bonding ability. In this study, we systematically investigated the solvatochromic behavior of four structurally asymmetric DLC derivatives bearing diverse alkyl side chains across a wide range of solvents differing in polarity, viscosity, and hydrogen-bonding strength. Steady-state UV–Vis absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy revealed that solvent polarity alone cannot fully account for the observed spectral variations. Instead, the Kamlet–Abboud–Taft (KAT) model particularly the dipolarity/polarizability parameter provided a more accurate interpretation of solvent effects. Dipole moment calculations further demonstrated that even subtle structural modifications can markedly influence molecular polarity and photophysical responses. To address the dynamic aspects of solute–solvent interactions, we introduce the Solvatoalignment Index (SAI), a composite descriptor that integrates solvent polarity, viscosity, and the solute’s dipole moment. This index effectively predicts solvent-induced spectral shifts and offers a more holistic perspective on solvent–solute interactions in anisotropic systems. Overall, our findings underscore the importance of considering multiple solvent parameters alongside molecular asymmetry for the rational design of next-generation DLC-based materials with tunable optoelectronic properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Discotic liquid crystals (DLCs) constitute an important class of organic semiconductors featuring rigid, planar aromatic cores surrounded by flexible alkyl chains. This molecular architecture enables both long-range orientational order and sufficient molecular mobility, making DLCs highly attractive for applications in chemical sensing, bioelectronics, advanced optical materials, and industrial coatings1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Their ability to transport charge along π–π stacked columnar structures has additionally drawn substantial interest in organic photovoltaics and light-emitting devices8,9,10,11. DLCs typically exhibit two mesophases, columnar and nematic, with approximately 95% adopting columnar phases stabilized by strong π–π interactions, while only about 5% form nematic phases9,10. Polyalkynylbenzene–based DLCs incorporating ethynyl (HC≡C–) groups often allow greater rotational flexibility and therefore preferentially stabilize nematic ordering11,12,13.

Our previous studies, together with related reports on symmetric discotic mesogens14 and heterocyclic derivatives including chalcones15,16, 4H-pyrans17, triazoles18,19,20, triarylmethanes21,22, azo compounds23,24, anthraquinones25,26 and retinoid analogues27,28 have demonstrated that modifying peripheral substituents (e.g., alkyl chain length, electron-donating/withdrawing groups) profoundly alters optical properties. Solvent effects additionally modulate the photophysical behavior of these systems14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. However, traditional solvent polarity descriptors (e.g., dielectric constant, refractive index) often fail to capture the multidimensional nature of solute–solvent interactions. To address these limitations, the Kamlet–Abboud–Taft (KAT) model provides a more nuanced, multiparameter framework based on the Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER)29:

In this model, α, β and π* represent the solvent’s hydrogen-bond acidity30, hydrogen-bond basicity31, and dipolarity/polarizability32, respectively. Their associated regression coefficients quantify the relative contribution of each parameter to the property being studied. Solvatochromism, solvent-dependent shifts in absorption or emission spectra, is commonly used to probe these interactions. However, for DLCs, spectral shifts arise not only from solvent polarity but also from molecular anisotropy, which is strongly coupled to the viscosity-dependent orientational freedom of the chromophore. Classical solvatochromic models, such as KAT and Lippert-Mataga, typically overlook this dynamic reorientation of anisotropic molecules. To address this limitation, we introduce the Solvatoalignment Index (SAI), defined as:

where μ is the molecular dipole moment, π* is the KAT polarity/polarizability parameter, and η is the solvent viscosity. This index reflects the premise that effectiveness of solvent-induced molecular alignment increases with \(\mu\) and π* but decreases with η. A high SAI value therefore indicates an environment in which dipole reorientation is both electronically favorable and mechanically feasible. Unlike traditional solvatochromic formalisms that treat polarity as a static descriptor, SAI incorporates diffusional and frictional contributions that govern the timescale and extent of solvatoalignment.

The use of bulk solvent viscosity (η)33 is consistent with standard solvatochromic approaches that assume dilute solutions and is particularly practical when microviscosity data are unavailable. By bridging electrostatic models with dynamic rotational effects, the SAI framework provides a more realistic descriptor for predicting solvent influences, especially in anisotropic systems where rotational freedom significantly impacts photophysical behavior. The relationship between solvent-induced spectral shifts and SAI can be expressed as:

where ν denotes the spectral parameter (absorption/emission maximum or Stokes shift), A represents the sensitivity of the spectroscopic response to solvatoalignment, and B accounts for background environmental contributions. These empirical fitting constants reflect intrinsic aspect of solute–solvent interactions that are not explicitly captured within the SAI itself. A correlates with the overall magnitude of the solvatochromic response, modulated by μ and \(\pi^{ * }\), while B adjusts for baseline spectral offsets arising from solvent-independent factors. Together A and B calibrate the SAI model to experimental observations and enable a quantitative interpretation of complex, multidimensional solvent effects.

Although the present experiments are conducted in dilute solution, where long-range liquid-crystalline order is absent, discotic molecules preserve the intrinsic anisotropy that governs their mesogenic behavior in bulk. Their extended π-cores, high polarizability, and asymmetric dipole distributions yield distinct–solvent interactions, including alignment tendencies that differ from conventional isotropic chromophores. These molecular-level orientation effects, observable through solution-phase solvatochromism, correspond directly to the mechanisms that control π–π stacking, columnar packing, and optical anisotropy in bulk mesophases. While practical applications of DLCs rely on collective supramolecular organization in bulk, dilute solution studies isolate the intrinsic electronic features, dipole asymmetry, conformational rigidity, and polarity response that predetermine columnar packing and mesophase stability. Such molecular-level characterization is essential for predicting which structural modifications will enhance π-stacking, charge mobility, and optical anisotropy in the condensed phase. Therefore, solution-phase solvatochromism provides a clean spectroscopic window into the inherent energetic landscape of the chromophore prior to self-assembly. In our earlier work on symmetric DLCs14, we explored how solvent polarity influences photophysical behavior. Here, we extend this investigation to asymmetric structures to assess how molecular variation modulates solvatochromism. Asymmetric structures, arising from unequal alkyl substitution or sterically hindered side chains, can significantly influence dipole orientation, packing efficiency, and solvation profiles. In this study, four asymmetric DLC derivatives differing in alkyl chain length were systematically studied across solvents with varying polarity, viscosity, and hydrogen-bonding capacity. Among evaluated LSER models, the KAT model exhibited the strongest correlation with experimental observations, with dipolarity/polarizability emerging as the dominant factor. Incorporation SAI provides a more comprehensive view by integrating dipole-alignment tendencies and solvent viscosity into the interpretive framework. Collectively, these insights deepen our understanding of solvent–solute interactions in anisotropic systems and support the rational design of DLC-based materials with finely tunable optical properties for targeted applications.

Experimental section

Materials

The asymmetric DLCs used in this study were synthesized according to the procedure described in Ref.13, and their molecular structures are presented in Fig. 1. All solvents were purchased from Merck (analytical grade, ≥ 99%) and used without further purification. Their viscosities and spectroscopic polarity parameters, as reported in Refs.29,33, are listed in Table 1.

Measurement of absorption and emission spectra

For the absorption and fluorescence measurements, dilute solutions of each asymmetric DLC were prepared at a concentration of 5 × 10−6 M in all selected solvents. Absorption spectra were recorded using a double-beam Shimadzu UV–2450 Scanning Spectrophotometer, while fluorescence spectra were obtained using a JASCO FP–6200 Spectrofluorometer. All measurements were performed at a controlled temperature of 25 °C, using standard quartz cuvettes with a 1 cm optical path length.

Estimation of dipole moments from spectral shifts

The differences in dipole moments between the ground and excited states of the DLCs were estimated by analyzing their absorption and fluorescence spectra in solvents of varying polarity. This analysis relies on empirical relationships derived from second–order perturbation theory, particularly the formalism developed by Kawski and co-workers34,35,36, which connects solvent-dependent spectral shifts with polarity parameters. The shift in wavenumbers corresponding to electronic transitions is expressed using the following relations:

where:

The influence of solvent polarity is incorporated through functions dependent on the dielectric constant (ε) and refractive index (n) of the medium:

These expressions, originally proposed by Lippert and Mataga and later refined by Bakshiev, assume the solute molecule resides in a spherical cavity with isotropic polarizability. Under the simplifying condition 2α/a3 = 1, the solvent functions reduce to:

In this study, the dipole moment analysis was conducted using the Bakshiev polarity function and therefore Eqs. (8) and (9) were applied within the Bakshiev (BK) model. Assuming that the ground- and excited-state dipole moments (µg and µe) are aligned along the same molecular axis, the difference in dipole moments can be calculated from:

Here h is Planck’s constant, c is the light’s velocity in vacuum, and (a) represents the effective radius of the solvation cavity, typically estimated via computational geometry optimization37. This method provides a quantitative evaluation of intramolecular charge redistribution upon electronic excitation and facilitates comparative analysis of how structural asymmetry and substituent variation influence the dipolar properties of DLCs across solvents with diverse polarity.

Result and discussion

Solvent polarity effects on the spectroscopic behavior of DLCs

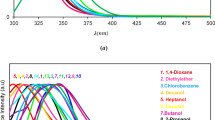

UV–Visible spectroscopy was employed to monitor how changes in solvent polarity influence the electronic transitions of asymmetric DLCs. Owing to the extended π-conjugation of their chromophore cores, the absorption and emission properties of these molecules are highly sensitive to the local solvent environment, particularly through dipolar stabilization and solvatochromic effects. The absorption and emission spectra of four asymmetric DLC samples–(b), (c), (e), and (f)–were recorded in a series of solvents ranging from non-polar to polar at room temperature (Fig. 2). The corresponding spectroscopic data were summarized in Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5. As shown in Fig. 2, increasing the solvent polarity leads to a clear red shift in both the absorption and emission spectral of all four samples. The absorption maxima shift from 342 to 353 nm, while the emission maxima move from 445 to 458 nm. These shifts indicate that polar solvents more effectively stabilize the excited states through dipole–dipole interactions. Nonetheless, the relatively modest magnitude of the shifts suggests that the molecular cores are fairly rigid and that the alkyl chains contribute minimally to solvent-induced spectral changes.

To further investigate the relationship between solvent polarity and spectral response, the maximum absorption wavenumbers were plotted against the dielectric constant (ε) (Fig. 3). Although all samples exhibit bathochromic shifts, the relatively low R2 values imply that ε alone does not adequately account for the observed trends. This indicates that both specific and non-specific solute–solvent interactions are involved. Specific interactions include hydrogen bonding π-π stacking, and dipole–dipole interactions, whereas non-specific interactions generally involve dispersion forces and dielectric stabilization. Fluorescence maxima (Fig. 4) followed a similar pattern, again showing only limited correlation with ε and highlighting the complexity of solvent–solute interactions. Additional insight is provided by Stokes shift data plotted against ε (Fig. 5), as larger Stokes shifts typically correspond to greater dipole reorganization and stronger solvent-induced stabilization of the excited state. Although all samples showed increasing Stokes shift with higher ε, sample (f) exhibited the smallest change. This suggests restricted molecular reorientation or limited excited-state stabilization in polar environments. Such behavior may arise from the S-configuration of sample (f), which imposes a more rigid or spatially constrained dipolar arrangement, reducing its ability to dynamically interact with polar solvents. Moreover, intramolecular steric effects particularly those due to the methyl-substituted phenylacetylene moiety may limit conformational flexibility and hinder dipole reorientation upon excitation. Given the extended π-conjugated surfaces of discotic cores, π–π stacking, ground-state dimer formation and excimer emission are natural considerations. However, at the dilute concentrations employed (5 × 10−6 M), neither the absorption spectra nor fluorescence profiles exhibit signs of aggregation, such as broadened low-energy absorption tails or red-shifted, structureless excimer emission. This confirms that the observed solvatochromic shifts originate primarily from monomeric species. Nevertheless, the inherent stacking tendency of DLCs remains relevant, as the same electronic features that promote excimer formation (extended π-area, dipole asymmetry, and alkyl-chain–induced sterics) also modulate solvatoalignment in solution and ultimately govern columnar stacking in bulk mesophases.

Correlation with multi–parameter solvent polarity scale

To evaluate how solvent characteristics modulate the spectral behavior of asymmetric DLCs, we applied multilinear regression analysis based on the KAT solvatochromic model. This model incorporates three empirical polarity parameters: dipolarity/polarizability (π*), hydrogen-bond donor acidity (α), and hydrogen-bond acceptor basicity (β). These parameters enable us to disentangle specific (hydrogen-bonding) and non-specific (dipolarity/polarizability) solvent–solute interactions. The numerical regression coefficients were converted into percentage contributions, as illustrated in Fig. 6 and summarized in Table 6.

In the absorption spectra, π* and α were the most influential parameters across all samples, with π* consistently dominating. This dominance can be attributed to the high polarizability of the extended π-conjugated system in the discotic core and the anisotropic molecular geometry, both of which enhance dipolar interactions. The contribution of α likely arises from specific hydrogen bonding between solvent molecules and the electron-rich peripheral regions (e.g., alkoxy substituents) in the ground state. The relatively small β contribution suggests that hydrogen-bond accepting interactions play a minor role during absorption.

The negative regression coefficients of π* and α in the absorption spectra indicate that increasing solvent dipolarity/polarizability and acidity lowers the transition energy. This suggests preferential stabilization of the excited state, thereby reducing the energy gap relative to the ground state. In contrast, the positive β coefficient implies that basic solvents increase the transition energy, which can be interpreted as preferential stabilization of the ground state or destabilization of the excited state. This behavior reflects the differing timescales of solvent–solute interactions: the ground state, having more time to undergo structural relaxation, responds more strongly to basicity, whereas the excited state is more effectively stabilized by polar and acidic environments due to its ultrafast character38.

In the fluorescence spectra, π* and α again emerged as the dominant parameters, but their regression coefficients exhibited a reversed pattern compared to absorption. The π* parameter remained negative, indicating that highly dipolarity/polarizability solvents stabilize the excited state and lead to lower emission energies (i.e. red-shifted fluorescence). In contrast, α exhibited a positive coefficient, implying that acidic solvents destabilize the excited state, possibly through hydrogen bonding that restricts structural relaxation or induces electronic repulsion. The β parameter varied considerably across samples. For example, sample (c) showed the highest β contribution, likely due to its relatively short alkyl chains and absence of methyl substituents, which enhances accessibility to hydrogen-bond accepting interactions in the excited state. By comparison, samples (e) and (f), which possess methyl groups near the aromatic core, displayed reduced β values, suggesting steric hindrance to solvent–solute hydrogen bonding. Furthermore, the unique S-configuration of sample (f) alters solvent accessibility and dipole orientation, which may account for its subtle derivations in π* and α contribution compared to its isomer (e).

Finally, analysis of molecular reorientation behavior, as inferred from solvatochromic shifts, revealed π* as the primary contributor, followed by β. This suggests that non-specific dipolar interactions predominantly govern dynamic solvation and molecular relaxation, whereas specific basic interactions (hydrogen-bonding) provide secondary modulations. Polar and acidic solvents were found to suppress reorientation, likely due to stronger stabilization of particular molecular conformations, whereas basic solvents facilitated greater molecular flexibility.

Estimation of ground state and excited state dipole moment.

The dipole moment is a fundamental molecular property that reflects the spatial distribution of electric charge within a molecule. It serves as a key indicator of molecular polarity, influencing solubility, intermolecular interactions, and overall behavior in diverse chemical environments. A comprehensive understanding of dipole moments provides valuable insights into molecular structure and is essential for the rational design of functional materials across various fields, including medicine, optics, and materials science. In this study, the dipole moments in the ground (µg) and excited (µe) states of four asymmetric DLCs were estimated using UV–Vis spectroscopy. First, the solvent polarity functions,\(f(\varepsilon ,n)\) and \(f(\varepsilon ,n) + 2g(n)\) were calculated and reported in Table 1. This analysis was carried out within the framework of the Bakshiev solvatochromic model, which correlates solvent polarity with spectral shifts. Subsequently, plots of \(\tilde{v}_{a} - \tilde{v}_{f}\) versus \(f(\varepsilon ,n)\) and \(\tilde{v}_{a} + \tilde{v}_{f}\) versus \(f(\varepsilon ,n) + 2g(n)\) were constructed for each compounds (see Fig. 7). The slopes obtained from linear regressions (m1 and m2) were then used in Eqs. (12) and (13) to determine the corresponding dipole moments. As shown in Fig. 7, the relatively low R2 values arise from specific interactions present in these systems that are not fully captured by the Bakshiev model. The omission of such interactions reduces the strength of linear correlations and results in lower coefficients of determination. The calculated dipole moments were summarized in Table 7, offering insight into the changes in charge distribution upon excitation and their dependence on molecular structure and the solvent environment.

As presented in Table 7, the dipole moment values vary among the studied liquid crystals depending on structural features and the surrounding medium. Although the four DLCs share similar chemical backbones, differences in stereochemistry, substitution patterns, and alkyl chain length notably influence the magnitude of their dipole moments. The dipole moments of samples (b) and (c) are relatively similar, as are those of samples (d) and (f). In samples (d) and (f), the presence of an additional methyl group on the phenylacetylene moiety increases the electronic asymmetry of the π-system, enhancing charge separation in both ground and excited states and leading to larger dipole moments. Moreover, the S-configuration of the chiral center in sample (f) induces a more directional molecular arrangement, strengthening the net dipole vector compared to its R-configured counterpart (sample d). Similarity, the longer alkyl chains in sample (b) facilitate improved alignment of peripheral electron density and greater conformational ordering in solution, resulting in a higher overall polarity and a larger dipole moment than in sample (c), which contains shorter chains. These structural distinctions illustrate how even subtle changes in molecular geometry and substitution patterns can meaningfully affect charge distribution and the polarity behavior of asymmetric DLCs.

Solvent effects on the spectra via the solvatoalignment index (SAI)

The Solvatoalignment Index (SAI), derived from a combination of solvent physicochemical properties including polarity, viscosity, and hydrogen-bonding ability, serves as an effective tool for assessing solvent-induced spectral variations in discotic molecules. Experimental evaluation of the SAI and its subcomponents, including SAIgr, SAIex, and SAIStokes’ shift, for four asymmetric DLC samples (b), (c), (e), and (f), across a wide range of solvents reveals statistically consistent and chemically interpretable trends (Tables 8, 9, 10, and 11). Viscosity values at 25 °C are reported in mPa s, and the SAI is expressed in Debye mPa −1 s−1.

In nonpolar and low-polarizability solvents such as Cyclohexane, SAI values are minimal. The absence of strong electrostatic fields limits solute–solvent interactions to week van der Waals forces, producing only minor differences between the ground and excited states. Consequently, spectral shifts are negligible and SAI values approach zero. As solvent polarity increases and viscosity decreases, as in Acetone, DMF, and Diethyl ether, SAI increases markedly. These solvents possess strong dipole moments and are capable of stabilizing the excited state more effectively than the ground state. Their low viscosity also enables faster molecular reorientation, further enhancing SAI values. In polar–hydrogen bonding solvents such as 2-Propanol and 1-Butanol, despite the potential for hydrogen bonding, high viscosity restricts molecular mobility, leading to moderated or nonlinear effects on SAI. In long-chain, highly viscous solvents like 1-Heptanol and 1-Decanol, a dual behavior emerges: while hydroxyl groups increase SAI through stronger polarity-driven interactions, high viscosity limits complete structural relaxation following photoexcitation, resulting in milder SAI enhancements. Overall, all studied compounds follow a consistent trend: increasing effective polarity combined with reduced dynamic constraints (lower viscosity) enhances SAI increases, reflecting the intertwined influence of polarity and relaxation dynamics to solute–solvent interactions.

To further elucidate solvent effects, correlations between SAI and key spectral parameters, namely absorption (SAIgr), emission (SAIex), and Stokes shift (SAIStokes’ shift), were examined (Fig. 8). Both absorption and emission wavenumbers systematically decrease with increasing SAI, indicating red shifts arising from preferential excited-state stabilization in high-SAI solvents. In contrast, SAIStokes’ shift correlations exhibit a linear increase across all compounds. This behavior stems from efficient solvent organization in polar, low-viscosity media, which leads to a greater decrease in emission energy relative to absorption. Although the systems exhibit complex interactions, supplementary analyses using the Lippert-Mataga and Reichardt models also reveal relatively low regression values. As noted earlier, no single solvent parameter is expected to fully predict spectral behavior. Nevertheless, the SAI method outperforms both classical approaches by capturing more comprehensive and physically meaningful trends.

These trends confirm SAI as a physically meaningful and predictive empirical index for spectral behavior in anisotropic media. Importantly, integrating viscosity within the SAI framework allows dynamic factors to be assessed, extending beyond what is a predictable using polarity-based model alone. In high-viscosity solvents, limited molecular mobility hinders structural reorganization, reducing excited-state stabilization and thereby lowering both SAI and the magnitude of the Stokes shifts. In contrast, low-viscosity environments enable rapid structural rearrangement, leading to pronounced increases in both parameters. Therefore, SAI reflects not only solvent polarity but also interplay between static and dynamic solvation properties. The observed statistical correlations between SAI and spectral features (absorption, emission, Stokes shift) highlight the index’s accuracy in quantifying solute–solvent interactions in anisotropic systems. As a multidimensional descriptor, SAI offers greater versatility and effectiveness than classical models such as Lippert–Mataga, which focus exclusively on polarity.

The empirical relationship presented in Eq. 2 describes the linear dependence of SAI on spectral characteristics (absorption, emission, and Stokes shift wavenumbers), and can be interpreted in two key aspects:

i) The slope coefficient (A) indicates the spectral sensitivity of each compound to environmental changes. Negative slopes in the absorption and emission equations correspond to red shifts in high-SAI solvents, while the positive slope in the Stokes shift equation reflects increasing energy separation between absorption and emission. Among the samples, sample (c) shows the highest spectral sensitivity in both absorption and emission (A = –86.63, –25.71), indicating a stronger influence of environmental factors on its electronic structure (Table.12). Conversely, Sample (e) exhibits the greatest sensitivity in the Stokes shift (A = 14.05), making it a promising candidate for optical sensing applications. Sample (f) shows a comparatively balanced behavior, while also showing the lowest B value in the Stokes shift equation–suggesting a minimal energy difference between absorption and emission under low-SAI conditions. Sample (b) displays the lowest Stokes shift sensitivity, reflected in its smallest A values.

ii) The intercept B reflects the intrinsic spectral properties of the molecule in the absence of environmental effects and is directly related to its electronic structure and bonding nature of the molecule characteristics. A higher B value in the absorption equation for sample (b) indicates higher ground-state energy under ideal conditions, whereas the lower emission wavenumber of sample (e) suggests greater intrinsic excited-state stability.

The composition and spatial orientation of functional groups exert a pronounced influence on the SAI by modulating the molecular dipole moment, overall polarity, and the nature of solute–solvent interactions. In samples (e) and (f), the presence of methyl substituents on the aromatic core enhances electron-donating capacity and molecular asymmetry, resulting in elevated dipole moments and higher SAI values due to stronger interactions with polar solvents. In contrast, samples (b) and (c) lack aromatic methyl groups, leading to reduced effective polarity and weaker solvent-induced perturbations—reflected in their lower SAI values. Furthermore, the incorporation of oxygen-containing alkyl chains across all samples facilitates dipole–dipole interactions that promote excited-state stabilization. Altogether, these findings underscore the pivotal role of functional group identity and positioning in governing SAI responses, highlighting the index’s sensitivity to both electronic and structural aspects of discotic molecular design. The linear SAI model not only quantitatively captures environmental effects but also distinguishes molecular sensitivity from inherent structural properties of discotic compounds. This analysis provides a robust framework for the rational design of environment-sensitive compounds for spectral sensing, optoelectronics, and excited-state studies.

Although the present study focuses on asymmetric DLCs, the physical basis of SAI, linking solvent polarity, viscosity, and molecular dipole-driven alignment, is not limited to this structural class. Similar polarity-dependent behavior has been reported for symmetric triphenylene-based mesogens14, suggesting that solvatoalignment contributes to spectral responses across different discotic frameworks. Therefore, SAI is conceptually generalizable to symmetric systems and alternative core geometries, although its quantitative sensitivity will depend on molecular dipole magnitude, core polarizability, and the degree of rotational anisotropy characteristic of each DLC family.

For comparison, linear regressions based on the Lippert–Mataga solvent function and the \(E_{T}^{{}} (30)\) polarity scales were performed for all four compounds (Table 13). In all cases, SAI yielded significantly higher R2 values (typically 0.70–0.83) compared with Lippert–Mataga (0.50–0.75) and \(E_{T}^{{}} (30)\)(0.46–0.75). These results confirm that incorporating viscosity-dependent rotational effects and dipole-driven alignment provides a more comprehensive descriptor of solvatochromic behavior, particularly for anisotropic systems such as DLCs. The corresponding solvatochromic plots for both classical models have also been provided in the Supplementary data.

Beyond steady-state spectroscopy, it is worth noting that the parameters embedded in the SAI expression, particularly solvent polarity, polarizability, and viscosity also appear prominently in theoretical models describing excited-state lifetimes. High-SAI solvents, which promote more efficient stabilization of the adiabatic excited state and facilitate faster solute–solvent reorientation, would be expected to suppress nonradiative decay channels, whereas low-SAI or highly viscous environments would favor faster internal conversion. Although time-resolved experiments are outside the scope of the present work, the SAI-based framework therefore offers a predictive foundation for future kinetic studies aimed at elucidating the dynamic relaxation behavior of asymmetric DLCs.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the photophysical behavior of asymmetric DLCs is strongly modulated by the surrounding solvent environment through a combination of specific (e.g., hydrogen bonding) and nonspecific (e.g., polarity, polarizability) interactions. Spectroscopic analyses, including UV–Vis absorption and fluorescence measurements, reveal that solvent dielectric constant alone is insufficient to explain the observed spectral variations. Instead, the Kamlet–Abboud–Taft (KAT) model provides a more nuanced framework, identifying dipolarity/polarizability (π*), hydrogen-bond donor ability (α), and hydrogen-bond acceptor ability (β) as the principal determinants of solute–solvent interactions. Among these parameters, π* consistently emerges as the dominant factor influencing absorption, emission, and Stokes shifts.

Dipole moment estimations for the ground and excited states showed that subtle structural modifications, such as methyl substitution or alkyl chain extension, can significantly impact molecular polarity. Molecules with greater charge asymmetry exhibited higher dipole moments, underscoring the critical role of molecular geometry in tuning optical responses. Furthermore, the introduction of the Solvatoalignment Index (SAI) offers a comprehensive descriptor that integrates key solvent properties, including polarity, viscosity, and hydrogen-bonding capacity. The strong correlations observed between SAI and spectral parameters (absorption, emission, and Stokes shift) validate its predictive capability. High SAI values, associated with high polarity and low viscosity, correspond to greater excited-state stabilization and larger spectral shifts. Overall, these findings highlight the complex interplay between molecular structure and solvent environment in controlling the photophysical behavior of asymmetric DLCs. The combined application of the KAT model and SAI provides a robust framework for understanding and predicting solvent-induced spectral phenomena and paves the way toward rational design of stimuli-responsive liquid-crystalline materials for sensing and optoelectronic applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Khoo, I. C. Liquid crystals: Physical properties and nonlinear optical phenomena Vol. 64 (Wiley, 2007).

Kaafarani, B. R. Discotic liquid crystals for opto-electronic applications. Chem. Mat. 23(3), 378–396 (2011).

Bushby, R.J.; Lozman, O.R., Discotic liquid crystals 25 years on Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science 7, 343–354 (2002).

Sergeyev, S., Pisula, W. & Geerts, Y. H. Discotic liquid crystals: A new generation of organic semiconductors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 36(12), 1902–1929 (2007).

Zhao, J. et al. Advances in biological liquid crystals. Small 15(18), 1900019 (2019).

Bisoyi, H. K. & Kumar, S. Discotic nematic liquid crystals: Science and technology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 264–285 (2010).

Gowda, A., Kumar, M. & Kumar, S. Discotic liquid crystals derived from polycyclic aromatic cores: From the smallest benzene to the utmost graphene cores. Liq. Cryst. 44, 1990–2017 (2017).

Kumar, M., Gowda, A. & Kumar, S. Discotic liquid crystals with graphene: Supramolecular self-assembly to applications. Part. Part. Syst. Charact 34, 1700003 (2017).

Maity, M. et al. Enhancing hole transport and autonomous healing properties of supramolecular columns in unsymmetrical discotics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 16(49), 68041–68051 (2024).

Uttam, R., Kumar, S. & Dhar, R. Magnified charge carrier conduction, permittivity, and mesomorphic properties of columnar structure of a room temperature discotic liquid crystalline material due to the dispersion of low concentration ferroelectric nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. E 1025, 052702 (2020).

Feng, C. et al. Triphenylene 2, 3-dicarboxylic imides as luminescent liquid crystals: Mesomorphism, optical and electronic properties. Dyes Pigm. 139, 87–96 (2017).

Khan, A. A. et al. Homologous binary mixtures and improved hole conduction of self-assembled discotic liquid crystals. Org. Electron. 36, 35–44 (2016).

Varshney, S. K., Prasad, V. & Takezoe, H. Room-temperature discotic cholesteric and nematic phases: influence of 3, 7-dimethyloctane peripheral chain on the molecular self-assembly of radial polyalkynylbenzene. Liq. Crys. 38, 53–60 (2011).

Kian, R. et al. Investigation of the spectroscopic features along with the media polarity effect in some symmetrical disc-shaped liquid crystals. J. Mol. Liq. 309, 113226 (2020).

Kian, R., Zakerhamidi, M. S., Shamkhali, A. N. & Kashani, E. Study of the variation of intra/intermolecular interactions and configuration of a group of Enone anticancer drugs as a result of solvation. J. Mol. Liq. 274, 1–14 (2019).

Kian, R., Zakerhamidi, M. S., Shamkhali, A. N., Kashani, E. & Pesyan, N. N. Investigation of interactional behavior and relative photo-physical properties in a group of bioactive compounds. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. 381, 111873 (2019).

Kian, R., Zakerhamidi, M. S., Shamkhali, A. N., Teimuri-Mofrad, R. & Rahimpour, K. Media and solute–solvent interaction effects on the photo–physical behavior of some drugs of 4H–Pyran derivatives. J. Mol. Liq. 238, 508–517 (2017).

Moayedniya, A., Gilani, A. G., Zakerhamidi, M. S., Dezhampanah, R. & Kian, H. Investigation of the effective interactions of two bioactive compounds in different media. J. Mol. Struct. 1274, 134534 (2023).

Kian, R., Seyed Ahmadian, S. M., Zakerhamidi, M. S., Babaie, G. & Nesari, P. Solvatochromism effects on the photo-physical behavior of two triazole compounds. Z. Phys. Chem. 230, 1561–1574 (2016).

Kian, R., Zakerhamidi, M. S., Seyed Ahmadian, S. M. & Babaie, G. Photo-Physical Response of Two Triazole Compounds Against Solvent Polarity. Z. Phys. Chem. 230, 1575–1589 (2016).

Kian, R., Zakerhamidi, M. S., Kandjani, S. A. & Dadashzadeh, M. The effective interactions of Fuchsine and Pararosaniline as two bioactive compounds in different solvent media: A comparative study. J. Mol. Struct. 1264, 133285 (2022).

Kian, R., Zakerhamidi, M. S., Shamkhali, A. N. & Nesari, P. The interactional behaviors and photo-physical properties of two triarylmethane drugs in solvent media. J. Mol. Liq. 225, 653–661 (2017).

Taheri, B., Zakerhamidi, M. S., Shamkhali, A. N., Kian, R. & Sadeghan, A. A. Solvent polarity effect on photophysical properties of some aromatic azo dyes with focus on tautomeric and toxicity competition. Sci. Rep. 15, 15716 (2025).

Zakerhamidi, M. S., Ahmadian, S. S. & Kian, R. The specific and nonspecific solvatochromic behavior of Sudan dyes in different solvents. Can. J. Chem. 93, 639–647 (2015).

Mehnati, P., Khoshsima, H., Zakerhamidi, M. S., Kian, R. & Sahrai, M. Solution environment effects on the photo-physical behavior of Daunorubicin and Mitoxantrone: Anthraquinone-based drugs. J. Mol. Struct. 1310, 138317 (2024).

Zakerhamidi, M. S., Johari-Ahar, M., Seyed Ahmadian, S. M. & Kian, R. Photo-physical behavior of some antitumor anthracycline in solvent media with different polarity. Spectrochim. Acta A. 130, 257–262 (2014).

Sahrai, H., Kian, R., Shamkhali, A. N., Kheradmand, R. & Zakerhamidi, M. S. Evaluation of solvent effect on the effective interactions of Isotretinoin and Tretinoin: Isomeric forms of vitamin A. Heliyon 10, e25174 (2024).

Kian, R., Seyed Ahmadian, S. M. & Zakerhamidi, M. S. Photo-physical properties of different types of vitamin A in solvent media. J. Mol. Struct. 1080, 8–13 (2015).

Reichardt, C. & Welton, T. Solvents and solvent effects in organic chemistry (Wiley, 2011).

Kamlet, M. J. & Taft, R. W. Linear solvation energy relationships. Part3. Some reinterpretations of solvent effects based on correlations with solvent π* and α values. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 349–356 (1979).

Kamlet, M. J. & Taft, R. W. The solvatochromic comparison method. I. The beta-scale of solvent hydrogen-bond acceptor (HBA) basicities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98, 377–383 (1976).

Abboud, J. L., Kamlet, M. J. & Taft, R. W. Regarding a generalized scale of solvent polarities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99, 8325–8327 (1977).

Riddick, J.A.; Bunger, W.B.; Sakano, T.K. Organic solvents: physical properties and methods of purification .190–205 (1986).

Bilot, L. & Kawski, A. Zur theorie des einflusses von Lösungsmitteln auf die elektronenspektren der moleküle. Z. Naturforsch. 17, 621–627 (1962).

der Kawski, A. Wellenzahl von elecktronenbanden lumineszierenden moleküle. Acta Phys. Polon. 29, 507–518 (1966).

Kawski, A.; Rabek, J.F. Progress in Photochemistry and Photophysics, Boston 1992.

Kabatc, J., Ośmiałowski, B. & Pączkowski, J. The experimental studies on the determination of the ground and excited state dipole moments of some hemicyanine dyes. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 63, 524–531 (2006).

Zakerhamidi, M. S., Nejati, K., Golghasemi Sorkhabi, S. & Saati, M. Substituent and solvent effects on the spectroscopic properties and dipole moments of hydroxyl benzaldehyde azo dye and related Schiff bases. J. Mol. Liq. 180, 225–234 (2013).

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R. Kian-Studied, analyzed and evaluated the data, and wrote and edited the manuscript A. Ranjkesh-Preparation and evaluated of the materials B. Taheri -Data collection S.K.Varshney-Preparation and synthesis of the materials N. Ebrahimpour–Investigated the manuscript M. S. Zakerhamidi-Studied, analyzed and evaluated the data, and wrote and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kian, R., Ranjkesh, A., Taheri, B. et al. Solvatoalignment index and solvent-dependent behavior of asymmetric discotic liquid crystals: effect of polarity and alkyl chain length. Sci Rep 16, 2810 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32720-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32720-5