Abstract

Bacterial bioerosion is a key taphonomic process affecting bone remains in diverse environments. This study presents the anthropological and taphonomic study of two clandestine lime graves from the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) with two individuals in each burial. These individuals were buried with lime, often used to make bodies disappear in clandestine graves. There is also a popular belief that lime prevents bacterial growth during decomposition and prevent infectious diseases, but we observed that lime does not cause bodies to disappear or mummified, but it dehydrates bone tissue and it did not inhibit the proliferation of microorganism (fungi and bacteria). We reinforced the use of non-invasive techniques in the histotaphonomic study of the ribs of these victims of the Spanish Civil War because not all the cross-sections prepared for SEM analysis consistently revealed microbial attack. However, the bioerosion could be observed along the entire ribs using microCT. Therefore, the shape, distribution and concentration areas of bioerosion were contrasted with both low-vacuum SEM and microCT images. The type and location of bioerosion observed in the ribs of these victims supports endogenous origin of bacteria, which modified bones despite the presence of lime. Bacterial bioerosion is, consequently, a key taphonomic process and potential invaluable forensic criterion of post mortem condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lime burials have been recognised since the Bronze Age and in the Egyptian, Greek, Roman and Medieval periods. However, the purpose of lime burials remains a subject of debate. Some authors considered that lime accelerated decomposition, while others observed that lime was rather used to preserve bodies1,2,3. Although experimental research has examined the impact of lime in controlled settings2, its role in bacterial bioerosion within real burial contexts remains unclear. Lime has been found in different contexts including burials of victims of natural disasters (e.g., tsunamis), infectious diseases (Middle Age Black Death) or even as a method to mummify bodies. Limes is also extensively used in clandestine burials (e.g., the two World Wars and the Spanish Civil War)2,4,5,6,7,8, as observed in the case we are studying here.

Lime (pH = 12–14) could appear in different forms such as limestone (CaCO3), quicklime (CaO) or hydrated lime (Ca(OH)2), and all of them are related to each other in the lime cycle2. Various experimental studies in the field or in the laboratory were carried out by Schotsmans et al.2,9,10 in order to understand the effects of lime on corpses. The results of these studies conclude that lime could retard the rate of decomposition in a burial environment. More recent studies in Taphos-m archaeological and anthropological experimental facilities in Spain confirmed that after five years buried bodies were skeletonized, independently of being buried with or without lime11. Therefore, once the lime was inactive the decomposition process continues to skeletonization stage7,12. Taphos-m confirm that lime did not dehydrated corpses, however, microscopic analysis of pig carcasses buried with lime confirms that it desiccates the cortical surface of the bones. In fact, the result of this dehydration process was observed as deep cracks on the cortical surface of the bones. Therefore, the lime in the burial did not desiccate the body but it did cause bone dehydration that we can observe as cracking11.

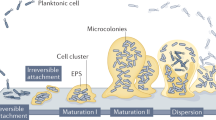

Bioerosion is the most common alteration observed in bone histology, including fossil remains. Microbial bioerosion was systematized and described by Hackett13 and according to that, there are four types of bioerosion modifications or micro-foci of destruction (MFD): Wedl tunnelling caused by fungi, and three forms (linear longitudinal, budded and lamellate) of non-Wedl tunnelling produced by bacteria13,14. Linear longitudinal and budded MFDs (surrounding the Haversian channels) represent the 85% of bacterial attack15,16. The most historically controversial issue is the origin of these bacteria: either they are from body’s gut bacteria (endogenous origin)16,17 or from the deposit site (exogenous origin)18. Most of the investigations of bioerosion were focused on clarifying this topic, while there is an increasing recognition that both endogenous and exogenous bacteria modify bones19,20,21. The endogenous bacterial attack occurs during the decomposition process while the exogenous bacterial attack both during and after decomposition of soft tissues18. The decomposition process starts very soon from inside the body, and during the short anaerobic phase of the gut putrefaction, an environment is created for the proliferation of endogenous gastrointestinal bacteria, such as Staphylococcus, Escherichia coli, Bacteroides and Clostridium22. The rapid transmigration of these bacteria into the body via the vascular network, Haversian and Volkmann canals17 is favoured by the increased physical permeability of decaying biological barriers (e.g., intestine walls, endothelia, cell membranes) and deterioration of the immune system. Because of that, endogenous bacterial attack is usually described around the Haversian canals used to gain access throughout the bone17,20. Bones close to the abdominal area (e.g., floating ribs) are usually more altered because they are near to the intestines where the bacterial putrefaction starts23. Bioerosion caused by gut microbiota indicates that the body was exposed to putrefaction16,24. Bacteria from the deposit site (soil or water) also cause decomposition of the body from the outside to inside16 and may enter the Haversian system through nutritional foramens or cortical fissures (from outside)20. The external bacteria are inhibited in particular circumstances, such as extreme temperatures, rapid desiccation/mummification of the soft tissues, or in absence of endogenous bacteria (e.g., infants)7,23. There are also differences in bacterial proportion in relation to the depth of the burial and, consequently, availability of oxygen and access of entomofauna25. Although, it is not clear if bacteria were inhibited in presence of lime during a long period of time.

Unlike the medical-legal histological studies which focuses on diagnosis of the death establishing the cause, mechanisms and manner of death, anthropological and archaeological reports focus on identifying and distinguishing between human and nonhuman bones26 estimating the age of the individual at death27 or diagnosing injuries or pathological features on bones28,29,30. Nowadays, the histotaphonomic studies need a complete study to distinguish ante mortem and post mortem history of the individuals, that is, combining analyses on the cortical surface and the histological cross sections of bones with the archaeological and anthropological data31,32. These combined studies will help us to understand, for example, why in warm areas the bodies were skeletonized with wet putrid matter, why unbroken bones cannot be identified genetically or why two bodies buried in the same deposit site were in different cadaveric states (i.e.,12,33,34). In this sense, combining the results of the anthropological and taphonomic study will allow us to better understand the post-depositional processes in lime burials.

The present paper includes an integrated anthropological and taphonomic study of two clandestine lime burials from the Spanish Civil War. This situation made us to emphasize the use of non-invasive techniques to study these four victims. This case is particularly relevant to the objectives of this study because in war situations bodies are often buried immediately after death in the ground (without coffins) and covered with lime. By combining traditional osteological assessments with non-invasive imaging techniques (SEM) and micro-computerized tomography (microCT), this study provides novel insights into bacterial bioerosion and post mortem modifications related to lime burials which might be of special relevance in past and modern conflict burials. This research aims to clarify bioerosion activity and the role of lime in bone-diagenetic processes, bridging forensic, taphonomic and archaeological perspectives.

Results of taphonomic observations

The two double graves exhumed were irregular in size, less than 1 m deep and 4.5 m from each other. Two of the victims were buried in the same direction, with individual 1 (RAF01) slightly on top of individual 2 (RAF02). The right side of individual 1 was in contact with the sediment and lime, and their left side was in contact with the right side of individual 2, who was lying on their left side on the ground (Fig. 1a). The other two victims were buried one (individual 3, RAF03) on top of the other (individual 4, RAF04) in opposite directions. Individual 3 was on his right side in contact with the sediment and a large amount of lime, and his left side in contact with individual 4, who was completely underneath individual 3 (Fig. 1b). These four victims were buried with lime covering the bodies, in fact, remains of lime (cast) were recovered. Some lime casts were preserved covering and shaping some anatomical regions (Fig. 1c). Moreover, textile printing was also obtained from the internal part of some lime casts (Fig. 1d) and several personal items belonging to the individuals were also recovered near the skeletons: buttons, clothing fragments, a pen, shoe soles and some metal objects.

The ribs from both sides of the four victims were macro and microscopically analysed, both on surface and histologically. The results will be presented separately.

Bone cortical surface optical microscope analyses

Different modifications were observed on the cortical surface of the ribs (Fig. 2): white and yellow particles produced by fungal colonies, insect puparia remain (entomofauna), branched and linear root marks, parallel linear brush marks, deep cracks by the permanent exposure to lime (signs of dehydration), flaked and cracked cortical surface with different colour patterns, black mineral stains from the soil and a reddish-brown coloration (signs of oxidation of any metal). Moreover, ribs RAF01i, RAF02i and RAF03i present signs of recent fragmentation.

Taphonomic modifications in the cortical surface of ribs: (a) fungal colonies in rib RAF01d, (b) rib RAF01i with insect puparia remains and black stains from some mineral of the soil (*), (c) root linear marks in rib RAF03d, (d) parallel linear marks in RAF01i produced during the cleaning of the bones (inside the box) with brush and some black stains of the soil (*), (e) RAF01i also with deep cracks by the alkaline environment of the burial with lime and black stains from the soil (*), (f) flaking surface in rib RAF02i, (g) flaking and cracking in RAF03d and (h) red-brown stain due to the oxidation of metals in rib RAF04i. Images captures by the binocular light microscope camera.

The SEM analysis of the bone surface showed an intense bacterial attack mainly underneath the outer cortical lamellae (Fig. 3a). This intense attack could be distinguished in the inspection of the bone surface through the cracks and flaking of the cortical surface. In addition, the SEM analysis allowed us to distinguish grooves and perforations larger than those produced by bacteria (Fig. 3b) which could likely correspond to the characteristic Wedl tunnels (measured in Fig. 3c) that were proposed to be produced by fungi. This is potentially consistent with the presence of fungi on the bone surface observed with the optical microscope (Fig. 2a).

Images of the bone cortical surface: (a) higher intensity of bacterial attack (white arrow) could be observed at the interior of the outer cortical lamellae, here observed through a flaked area of the cortical surface of the bone (broken line); (b) view of the outer cortical bone surface showing large and longer tunnelling than those caused by bacteria (which potential agent could be fungi) and perforations when fungi penetrate perpendicularly to the cortical; and (c) measurement of the larger tunnelling and detail of the perforations (perpendicular tunnelling) note the background is covered by dispersed bacteria tunnelling. Images captured by SEM camera.

Cut-section histological SEM analyses

The histological cut sections of the ribs in the ventral and dorsal edges showed atypical granular white modifications were observed with the naked eye (Fig. 4a-c). The SEM analysis of the cross sections confirmed that these whitish and granular texture were caused by bacteria (Fig. 4b-d). In fact, the Oxford Histological Index (hereinafter referred to as OHI) results provided a grade between 0 (less than 5% of the intact bone) to 2 (less than 33% of intact bone) in most samples (Table 1), compatible with widespread bacterial attack (hereinafter referred to as BAI). However, RAF01d and RAF02i were well preserved and no bacterial bioerosion was observed in the cut sections at the SEM (OHI = 5, > 95% intact bone).

Different modifications by bacterial attack distinguished in the same sample. Microscopical focal destruction (MFD) hyper-mineralised rims (Fig. 5a) involve microperforations and microtunnelling, which are different views of the bacteria trajectories that conform the bacterial colonies. Bacterial modifications cover entirely the compact bone from the edge of the bone to the cancellous bone tissue which trabeculae are also affected (Fig. 5b). When the bacterial attack is very intense, lacunae surrounding the Havers canals are destroyed, bacteria may break the wall of the Havers canals (Fig. 5c) and they disperse through the Haversian system across the bone. The overlapping of specific colonies around Haversian canals (Fig. 5d) indicate different bacterial generations affecting these bones. Moreover, the bone tissue broke after the bacterial attack due to the colonies appeared broke (Table 1, GHI and CRI = 3 and 4). Microcracks had different sizes, and most of them broke down bacterial colonies and Haversian canals (Fig. 5e).

Details of the bacterial attack: (a) modifications caused by bacteria in the form of tubes (*) and dots and comas (**); (b) both compact and cancellous bone were modified; (c) the Haversian canals were also changed and removing; (d) different bacterial generations could be distinguish due to the overlapping of the colonies (white arrow); and (e) after bacterial attack samples broke (white arrows). Abbreviature: H: Haversian canal. Images captures by SEM camera.

Histological MicroCT analyses

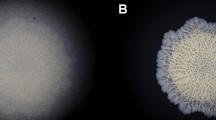

Although no signs of bacterial attack were observed in the histological section of the ribs RAF01d and RAF02i (OHI = 5), modifications compatible with bacterial attack (OHI = 3) could be identified in compact and trabecular bones analysing the complete ribs with microCT (Fig. 6). Table 1 shows this improved identification of areas affected by bacteria when analysed with microCT, which scans the entire sample (OHI microCT), compared to those analysed in histological sections (OHI SEM). Therefore, all the ribs analysed, that is, all the individuals, presented bacterial bioerosion. The 3D model also allowed us to identify the distribution of bacteria modifications as thin canals or tubes along the ribs, demonstrating their connection to the Haversian canals at different levels.

Images of microtomography of RAF01d and RAF02i (a-b) were dark zones compatible with modified areas (white arrow) could be identified, and details of the 3D models (c-d) were the Haversian canals and bacterial canals could be differentiated (black arrows). Images captured by software. Abbreviature: H: Haversian canal.

Discussion

Lime is an element that has been used in burials from war conflicts, such as the one presented here. Lime is an element that has been used in burials from war conflicts, such as the one presented here. Previous studies have confirmed that lime can slow the initial stages of decomposition, but bodies become skeletonized over time2,7,9,10,12. The four bodies studied here confirmed this statement, because all of them were skeletonized after been buried with lime for more than 80 years. However, lime causes desiccation of bone tissue, which can be observed as deep cracks on the cortical surface of the bones, as we previously described in an experimental work11. Unfortunately, histological cracks caused by lime dehydration cannot be distinguished in microCT images to evaluate dryness in the sample as a whole. By analysing the bones microscopically, it was possible to determine which bones were buried with lime. Therefore, it is possible to identify the burial practices through histotaphonomic analysis31,32. Nevertheless, the effects of lime in bone histology are not yet well understood, and we did not know if lime affects or not to bacterial bioerosion.

Both graves had abundant remains of lime and lime casts covering and around the skeletons as described in other exhumation of the Spanish Civil War burials and in some experiments with lime7,9,10,11. The lime cast was formed during the active stage of the decomposition and it adheres to the soft tissues of the body. During the emphysematous phase of the decomposition, the body and the lime cover increased their volume forming the lime cast2. Once this phase is over, the body deflates and reduces in size. The upper part of the lime cast breaks off and falls onto the cadaveric remains, as we also observed previously11,12 in the Taphos-m experimental project. At this point lime loses its effect and the decomposition process continues to skeletonization. In fact, here we described two double simultaneous primary burials from the Spanish Civil War where four bodies were buried with lime. After a long period of burial (80 years) they were skeletonized. Therefore, this work confirmed the observations made in experimental works2,11,12 and in real burials with lime from the Spanish Civil War with lime2.

The two graves here studied correspond to burial of four males between 25 and 39 years old. The gold dental prostheses that RAF02 and RAF03 individuals may suggest high-cost treatments. These dental treatments were not carried out in Spain in this epoch and most probably could correspond to dental work and treatments carried out abroad35. The two separate graves suggest that they were not killed at the same time, although possibly not much time elapsed between the two events. The skeletons were articulated, most likely due to the small size of the graves and the need to fit the bodies into them. Further, clothing and the lime cast maintained the skeletal elements jointed in these strict positions without any skeletal displacement, corroborating what was previously described in other human burials36.

The taphonomic modifications observed on the cortical surface of the bones were all related to a burial context lime (bone coloration, root marks, flaking, cracking, attached soil spots), to the decomposition process (bone coloration and texture, remains of entomofauna and fungal colonies, flaking, cracking and fragmentation) and with the processing of the cadaveric remains after the exhumation [i.e., 2,7,11–12,33–34]. These modifications, location of the graves and the arrangement of the skeletons of the four individuals indicate the same pattern of death and burial7,37, and confirm that the bodies have decomposed in situ (primary burials). Moreover, the results of the preservation index (63.6% see methods) indicate the absence of some bones (e.g., cranium or lower extremities). These bones were possibly removed during previous building works. It is common to find incomplete skeletons in burials in construction areas because some bones haven been previously removed35.

The fungal colonies observed on the cortical surface of RAF01d (Fig. 2) only affect the outer cortical bone as it was observed at the SEM inspection of the bone surface, absent in the cross section (Fig. 3). These tunnels have the size of most hyphae diameters (1.2 to 18 μm)31, much larger than bacteria tunnelling (0.6 to 1.2 μm)23 observed in the background of Fig. 3c.

Despite of all these taphonomic modifications on the cortical surface of the ribs (Fig. 2), their overall macroscopic appearance was good. However, at the microscopic level, the taphonomic indexes (specially OHI and BAI) showed high levels of bacterial bioerosion (Table 1; Fig. 5). The OHI values varied depending on whether the bones were analysed with SEM or microCT. In general, all bone sections showed low OHI values, related to bacterial bioerosion, except for two samples (RAF01d and RAF02i) that showed good preservation of bone tissue (Table 1). This was striking because all four bodies had been buried under the same conditions. Therefore, we decided to analyse these two ribs with microCT and reported OHI values of 3, more similar with the values of the rest of the ribs (Table 1). The presence of bacterial modifications in the histology supports the idea that lime does not inhibit the decomposition of the bodies because the bacteria have already decomposed the soft tissues. These differences in bacterial intensity may respond to the different seasonal time period of burial when these bodies were killed and buried. More experimental work is needed to confirm this temporal/seasonal differences between graves and, therefore, between deaths.

The position of the bodies in the graves had effect on the bacterial damage. Ribs of RAF01 and RAF02 in contact with soil (i.e., left rib of RAF02 and right rib in RAF01, see drawings of Table 1) showed lower intensity of bacterial attack, whilst the highest intensity of bacterial attack occurs in ribs between the bodies (i.e., right rib of RAF02 and left rib in RAF01, see drawings of Table 1). Bacteria intensity and organization observed in the contact areas between corpses suggest, therefore, that these bacteria were endogenous or at least, soil bacteria were unlikely to have acted in this grave. RAF03 and RAF04 (in supine position) have both the highest extreme intensity of bioerosion (OHI = 0–1, see drawings of Table 1). More comparative studies of multiple graves with lime are needed to confirm this.

We have associated the cracking pattern in bone histology with the dehydration of bone tissue during decomposition (moisture changes)11,38 or it could have been caused by the histological processing of the samples in the laboratory20. The changes in moisture of the bones during decomposition, also affects bacterial activity. In fact, overlapping colonies have been observed (Fig. 5d, white arrows), indicating different bacterial generations20,38.

Most of the studies about bone bioerosion are based on optical microscopy, SEM and CT13,16,18,23,31,32,38,39. The inclusion of microCT analysis in this study represents a significant methodological advance in the study of the graves from the Spanish Civil War. This is a non-destructive method4 and several authors have optimized this technique15,24,40,41 applied to bone diagenesis. The identification of bacterial attack using the microCT images is based on the lower density of bioerosion, which appears as grey areas on slides24,40,41. However, the dispersion and organization of MDFs in the Haversian system is currently only visible in histological sections under a microscope (optical or electron). Better identification of bioerosion using microCT will be possible with technical improvements (nanoCT) and by applying artificial intelligence when there are more cases to refine the results.

When we make histological sections, we arbitrarily choose an area to cut, and the results presented here demonstrate that examining only one bone section does not reflect the reality of post-depositional processes. That is, if we had not performed microCT on those ribs, we would have deduced erroneously that there was no bioerosion in one grave and there was in the second one. However, the microCT results confirm the presence of bacterial bioerosion in another area of the bone that we had not cut. We demonstrate the importance of analysing the bones in their entirety and not conclude only with the information obtained from bone sections. This agrees with other authors who confirmed the importance of using both techniques to obtain histotaphonomic information24,31,32,33. In this case, it was not possible to perform multiple rib sections because the bones, once identified, will be returned to the family. Therefore, we considered microCT analysis more useful for obtaining reliable results. Likewise, Trenchant40 concluded that the intra-skeletal variation was limited, so, we may assume that the ribs here analysed can be considered representative of each individual. We believe that in the near future, histotaphonomic studies should be conducted exclusively with microCT or nanoCT. Currently, there are studies that confirm the objectivity and reliability of histotaphonomic analyses using microCT [i.e., 15,24,40–41], and we will continue to improve these techniques and apply them to more real cases as the one presented here, demonstrating the importance and usefulness of taphonomic studies with advanced technology for resolution forensic cases.

Finally, the presence of lower bioerosion intensity on the ribs in contact with sediment and higher (maximum) intensity on the ribs in contact with another body, with MFDs surrounding the Haversian canals, suggests that the bioerosion observed in these individuals has an endogenous origin caused by the gut bacterial biome16,17,20.

The combination of osteological and taphonomic results presented here confirms the importance and necessity of conducting multidisciplinary studies to contextualize death31,32. In this case, the combination of different techniques (optical microscopy, SEM, and microCT) has been relevant to understand the effect of lime in these two graves from the Spanish Civil War.

Conclusions

The combination of anthropological and taphonomic studies provides a better understanding of human burials from the Spanish Civil War. Despite of the small sample size, we could conclude that the lime did not conserve the bodies but it maintains the anatomical connection of the skeletons, keeping the bones in their original burial positions without displacement, and it causes bone dehydration. The presence of lime in the burials did not stop the bacterial activity during decomposition because we saw bacterial modifications in bone histology. Further research and experiments need to be done to increase the sample size, but these results about the intensity and dispersion of bacterial damage on bone histology suggest that the microbial origin fits with an endogenous origin. Methodological advances in taphonomy made possible to increase the analyses of microbial activity in bones using microCT. The complete scan of the ribs using a non-destructive method allowed us to confirm that all ribs were altered by bacterial bioerosion. These findings underscore the complex role of lime in burial environments and highlight the value of integrating advanced imaging techniques in forensic and archaeological investigations.

Materials and methods

Historical context of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) was a major conflict in Spain between the Republicans (communists, socialists, and anarchists who wanted to maintain the Republic) and the Nationalists (led by General Franco to abolish the Republic). The war began on July 18th with a military rebellion against the democratically elected government. The war was marked by significant mass executions, bombings of civilian areas and widespread repression. The Nationalist won the war, and General Franco established a dictatorial government that lasted until his death in 1975. It is estimated that there are around 2,500 to 3,000 mass graves from the Spanish Civil War and ulterior executions by Franco throughout the country42. Different associations, organizations and companies work to locate, exhume and identify the remains buried in these graves frequently with lime, providing the families of the victims with the opportunity to recover and offer them a dignified burial7,37. In addition, the study of these burials offers valuable archaeological, historical and taphonomic data, serving as a retrospective study.

Excavation, the site and human remains

In 2019 during the construction of luxury buildings in a residential area (X426186.5/Y4583711.8/Z133.72) of the city of Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain) appeared human remains which part of one of the skeletons exposed by the machinery. These bone remains were exhumed following a rescue excavation that discovered four individuals buried in lime in two separate graves and they apparently corresponding to the context of the Civil War. The sediment was dark brown with a clayey matrix, loose consistency, abundant organic matter, some small pieces of coal, snails and elements of terrestrial fauna.

The excavation and exhumation of the cadaveric remains were carried out by a team of archaeologists and anthropologists led by de General Direction of Democratic Memory from the Catalonia Government (Pla de fosses de la Generalitat de Catalunya). After that, the remains were transferred to the Palaeoanthropology and Paleopathology laboratory of the Archaeological Museum of Catalonia (MAC) where the anthropological study was carried out. It consisted on the estimation of the biological profile (sex and age), the description of the pathological or traumatic traits and dental condition. The results of this study have been previously published35 and the information is included in the present work (Table 2). All the skeletons were adults males and different bone pathologies associated with metabolic (i.e., orbital cribra), degenerative disorders (i.e., dissymmetry of the lower extremities), congenital (Klippel-Feil syndrome) or dental disorders and infections (porosity and fistulas) were observed in the skeletons. It should be noted that RAF02 had a remodelled Colles’ fracture of the left radius and RAF04 presented an ossificant myositis in the right femur (45.50 × 14 mm). Individuals had lost several teeth during their life and presented some caries, although individuals RAF02 and RAF03 wore gold prostheses. The four individuals also showed peri mortem fractures in the skull, mandible and teeth, compatible with the shot of a firearm projectile. These lesions would correspond to the manner of death of all of them. Moreover, genetic studies are been conducted at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB).

Macroscopic taphonomic analysis

The description of the cadaveric state was based on the classification by Nociarová33 and the Bradford score1. The spatial distribution of the skeleton was evaluated as articulated, disarticulated or displaced36. The completeness of the body was estimated with the preservation index (PI)43. The coloration of bones was described according to the Munsell Soil Colour Charts44 and the taphonomic alterations on the cortical surface and histology were identified and described using the Atlas of Taphonomic Identifications20. The results of this analysis are also included in the present work (Table 3).

The first grave contained the cadaveric remains of individual RAF02 buried on the left side with legs bent and RAF01 above the previous one and in the same anatomical position (Fig. 1a). The individuals of the second grave, RAF03 and RAF04, were in supine position and placed one on top of the other in the opposite way (Fig. 1b). Therefore, all of them were strictly articulated, maintaining forced positions. The cadaveric remains were completely skeletonized, although, individual RAF02 still preserved some remains of soft tissues attached to the bones. Bradford scores were > 90%, with heavy changes compatibles with bodies in advanced decomposition process. The four skeletons were incomplete, especially, the individual RAF03 which had only the superior part of the body (IP3 = 63.6%). The lack of these skeletal elements was probably caused by the bulldozer in a previous excavation. Most bones were between brownish yellow (10YR 6/6) and dark yellowish brown (10YR 4/6). Orange or green spots were also observed on the bone surfaces. In general, bones were fragmented, and the cortical surface was flaking and cracking.

Bone sampling

Specifically for this paper, two ribs (10th or 11th ) were selected from each individual from each side (left and right, n = 8 samples) to perform a detailed macroscopic taphonomic analysis and the taphonomic examination of the bone microstructure. Ribs were selected as bone samples because they are close to the abdomen, where the decomposition of the body begins. The analyses were performed at the Laboratory of Environmental Analysis and Taphonomy (LeaT), housed at the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (MNCN-CSIC, Madrid, Spain), with the authorization of the Catalonia Government. Ribs were labelled with the code of the individual and “d” for right ribs or “i” for left ribs. The cortical surface of these ribs was formerly studied using a magnifying lamp (5x-8x) and a more exhaustive analysis was also performed using a binocular light microscope motorized in Z (Leica M205A, 8x to 100x magnification) and images were recorded with a high-resolution digital camera (Leica DFC450). After the optical microscopic study, ribs were sectioned using a mechanical diamond saw for histological preparation and the bone surface was polished with silicon carbide abrasive papers, finishing with 1 μm and 0.3 μm alumina on a polishing cloth at low velocity (using water as a lubricant). The histological preparation was performed at the Laboratory of Palaeontology (Universidad Complutense de Madrid) in collaboration with LeaT.

SEM analysis

The histotaphonomic analyses included the use of a low-vacuum scanning electron microscope (SEM FEI-INSPECT) to analyse the cortical surface and bone histology of the samples, and a microCT (NIKON XT H 160) to analyse the microstructure of the complete bones (ribs RAF01d and RAF02i). All these pieces of equipment are housed at the Laboratory of Non-Destructive Techniques of the MNCN-CSIC.

Observations at SEM were made at different magnifications (40x-1600x), under backscattered mode (BSED) and secondary electron (SE/LFD) detectors. Based on SEM images, the histotaphonomic study aims the evaluation of the integrity of the histological structures using Oxford Histological Index (OHI, see45 for details and terminology) and General Histological Index (GHI, see32,46 for details and terminology). OHI records the taphonomic alterations caused by microorganisms on a scale of 0 (no original features recognisable, except Haversian canals) to 5 (very well preserved, similar to recent/fresh bone), while GHI measures all taphonomic modifications on bones including alterations caused by non-biological taphonomic agents, such as cracking (also in a scale of 0 to 5)32,45,46. Moreover, regarding the different scoring indices (scale of 0–5) developed by Brönnimann et al.31, bacterial attack (BAI), Wedl tunnelling (WT), cyanobacterial attack (CAI) and cracking (CRI) were also included in the present study.

MicroCT analyses

The microCT system obtained image resolutions ranging from 6.19 μm to 64.21 μm (isotropic voxel size). The equipment has fixed detectors, and the object rotates along the vertical axis. The strong curvature of the ribs caused the scanned area to move away from and towards the detectors with each rotation. This made it impossible to acquire a single three-dimensional X-R image in a scan with a good resolution. Thus, it was necessary to scan the whole of the human ribs in two or three scanning shots at a tomography resolution of approximately 5 μm.

Data availability

The data sets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Schotsmans, E. M. J. et al. Effects of hydrated lime and quicklime on the decay of buried human remains using pig cadavers as human body analogues. Forensic Sci. Int. 217, 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.09.025 (2012).

Schotsmans, E. M. J. The effects of the lime on the decomposition of buried human remains: a field and laboratory-based study for forensic and archaeological application [PhD dissertation] University of Bradford (2013).

Van Strydonck, M. et al. The protohistoric ‘quicklime burials’ from the Balearic islands: cremation or in humation. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 25, 392–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.2307 (2013).

Booth, T. J., Chamberlain, A. T. & Pearson, M. P. Mummification in bronze age Britain. Antiquity 89, 1155–1173. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2015.111 (2015).

Congram, D. A clandestine burial in Costa rica: prospection and excavation. J. Forensic Sci. 53, 793–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2008.00765.x (2008).

De Ville, C. Epidemics caused by dead bodies: a disaster myth that does not want to die. Pan Am. J. Public. Health. 15, 297–299 (2004).

Schotsmans, E. M. J. et al. Analysing and interpreting lime burials from the Spanish civil war (1936–1939): a case study from La Carcavilla cemetery. J. Forensic Sci. 62, 498–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13276 (2016).

Schotsmans, E. M. J. & van de Voorde, W. Concealing the crime: the effects of chemicals on human tissues. In Taphonomy of Human Remains: Forensic Analysis of the Dead and the Depositional Environment (eds. Schotsmans, E. et al.) 335–351 (Wiley, 2017).

Schotsmans, E. M. J., Denton, J., Fletcher, J. N., Janaway, R. C. & Wilson, A. S. Short-term effects of hydrated lime and quicklime on the decay of human remains using pig cadavers as human body analogues: laboratory experiments. Forensic Sci. Int. 238, 142e1–14142 (2014).

Schotsmans, E. M. J., Fletcher, J. N., Denton, J., Janaway, R. C. & Wilson, A. S. Long-term effects of hydrated lime and quicklime on the decay of human remains using pig cadavers as human body analogues: field experiments. Forensic Sci. Int. 238, 141e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.12.046 (2014).

Gutiérrez, A., Nociarová, D., Malgosa, A. & Fernández-Jalvo, Y. What does lime tell Us about cadaveric remains? Hist. Biol. 37, 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2297911 (2023).

Gutiérrez, A. Estudio de los efectos tafonómicos observados en los restos cadavéricos de Sus scrofa domestica [PhD dissertation] (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (2021). http://hdl.handle.net/10803/673327.

Hackett, C. J. Microscopical focal destruction (tunnels) in exhumed human bones. Med. Sci. Law. 21, 243–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/002580248102100403 (1981).

Wedl, C. Uber einen Im Zahnbein und Knochen Keimenden Pilz. Akademi Der Wissenschafen Wien Fitzungsberichte Naturwissenschaftliche Klasse ABI Mineralogi Biologi Erdkunde 50, 171–193 (1864).

Mandl, K. et al. Substantiating MicroCT for diagnosing bioerosion in archaeological bone using a new virtual histological index (VHI). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 14, 104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-022-01563-w (2022).

White, L. & Booth, T. J. The origin of bacteria responsible for bioerosion to the internal bone microstructure: results from experimentally-deposited pig carcasses. Forensic Sci. Int. 239, 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.03.024 (2014).

Bell, L. S., Skinner, M. F. & Jones, S. J. The speed of post mortem change to the human skeleton and its taphonomic significance. Forensic Sci. Int. 82, 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/0379-0738(96)01984-6 (1996).

Turner-Walker, G., Gutiérrez, A., Armentano, N. & Hsu, C. Q. Bacterial bioerosion of bones is a post-skeletonisation phenomenon and appears contingent on soil burial. Quaternary Int. 660, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2022.12.009 (2022).

Booth, T. J., Bricking, A. & Madgwick, R. Comment on bacterial bioerosion of bones is a post-skeletonisation phenomenon and appears contingent on soil burial. Quaternary Int. 702, 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2024.02.005 (2024).

Fernández-Jalvo, Y. & Andrews, P. Atlas of Taphonomic Identifications: 1001 + Images of Fossil and Recent Mammal Bone Modification (Springer, 2016).

Madgwick, R. & Bricking, A. Exploring mortuary practices: histotaphonomic analysis of the human remains and associated fauna (in press). In In the Shadow of Segsbury: Archaeological Investigations on the H380 Childrey Warren Pipeline 2018-19 (eds. Guarino, P. & Barclay, A.) 96–102 (CA Monograph. Cotswold Archaeology Cirencester, 2023).

Ioan, B. et al. The chemistry decomposition in human corpses. Rev. Chim. 68, 1450–1454. https://doi.org/10.37358/RC.17.6.5672 (2017).

Jans, M. M. E., Nielsen-Marsh, C. M., Smith, C. I., Collins, M. J. & Kars, H. Characterisation of microbial attack on archaeological bone. J. Archaeol. Sci. 31, 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2003.07.007 (2004).

Booth, T. J., Redfern, R. C. & Gowland, R. L. Immaculate conceptions: micro-CT analysis of diagenesis in Romano-British infant skeletons. J. Archaeol. Sci. 74, 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.08.007 (2016).

Emmons, A. L. et al. Postmortem skeletal microbial community composition and function in buried human remains. Systems 7, 256 (2022).

Mulhern, D. M. & Ubelaker, D. H. Differences in osteon banding between human and nonhuman bone. J. Forensic Sci. 46, 220–222 (2001).

Gocha, T. P., Robling, A. G. & Stout, S. D. Histomorphometry of human cortical bone. In Biological Anthropology of the Human Skeleton (eds. Katzenberg, M. A. &Grauer, A. L.) 145–187 (Wiley, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119151647.ch5.

O’Brien, R. C., Appleton, A. J. & Forbes, S. L. Comparison of taphonomic progression due to the necrophagic activity of geographically disparate scavenging guilds. Can. Soc. Forensic Sci. J. 50, 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/00085030.2017.1260894 (2017).

Schwab, N., Galtés, I., Winter-Buchwalder, M., Ortega-Sánchez, M. & Jordana, X. Osteonal microcracking pattern: a potential vitality marker in human bone trauma. Biology 12, 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology12030399 (2023).

Winter–Buchwalder, M. et al. Microcracking pattern in fractured bones: new approach for distinguishing between peri– and postmortem fractures. Int. J. Legal Med. 138, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-022-02875-1 (2022).

Brönnimann, D. et al. Contextualising the dead–Combining geoarchaeology and osteo-anthropology in a new multi-focus approach in bone histotaphonomy. J. Archaeo Sci. 98, 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2018.08.005 (2018).

Hollund, H. I. et al. What happened here? Bone histology as a tool in decoding the postmortem histories of archaeological bone from Castricum, the Netherlands. Int. J. Osteoarchaeo. 22, 537–548. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.1273 (2012).

Nociarová, D. Taphonomic and anthropological analysis of unclaimed human remains from cemetery context in Barcelona [PhD dissertation] (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 2016). https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/393919#page=1.

Nociarová, D., Adserias, M. J., Armentano, N., Galtés, I. & Malgosa, A. Exhumaciones de Los Restos Humanos no reclamados Como Modelo tafonómico. Rev. Española Med. Lega. 2, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reml.2014.08.003 (2014).

Armentano, N., Galtés, I., Medina, E. & Subirà, M. A. Fosses del carrer Ràfols (Sarrià, Barcelona). Estudi Antropològic i Forense (2020).

Nociarová, D. et al. Joint disassociation pattern from a taphonomical and anthropological point of view. Hist. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2230579 (2023).

Serrulla, F. Estudio antropológico de los desaparecidos de la Guerra Civil y el franquismo en fosas comunes de España: una propuesta metodológica para su excavación y análisis [PhD dissertation]Universidad de Santiago de Compostela (2013).

Pfretzschner, H. U. Microcracks and fossilization of Haversian bone. Neues Jahrbuch Geol. Paläontol.—Abhandlungen 216, 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1127/njgpa/216/2000/413 (2000).

Martin-Champetier, A. et al. Optimizing CT scan paramaeters for dry archaological bones: a qualitative study as a first step towards standardizing CT acquisition protocols. Int. J. Osteoarch. 35, e3390. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.3390 (2025).

Trenchat, L. et al. Assessing histotaphonomy: a pilot study using image analysis for quantitative scoring of bone diagenesis. Int. J. Osteoarch. 35, e3404. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.3404 (2025).

Duffet-Carlson, K. S. et al. B. 3D visualization of bioerosión in archaeological bone. J. Archaeo Sci. 145, 105646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2022.105646 (2022).

Congram, D., Flavel, A. & Maeyama, K. Ignorance is not bliss: evidence of human rights violations from civil war Spain. Ann. Anthropol. Pract. 38, 43–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/napa.12041 (2014).

Safont, S., Alesan, A. & Malgosa, A. Memòria de l’excavaciò Realitzada a La Tomba Del Carrer Nou, 12 (Sant Bartomeu Del Grau, Osona) (1999). https://calaix.gencat.cat/handle/10687/8455?show=full.

Munsell Soil Colour Charts. Macbeth Division of Kollinorgen Instruments Corporation (New Windsor, 1994).

Hedges, R. M., Millard, A. R. & Pike, A. W. G. Measurements and relationships of diagenetic alteration of bone from three archaeological sites. J. Archaeol. Sci. 22, 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1995.0022 (1995).

Millard, A. R. The deterioration of bone. In Handbook of Archaeological Sciences (eds. Brothwell, D. R. & Pollard, A. M.) 637–647 (Wiley, 2001).

Acknowledgements

This study has been possible thanks to the commitment and funding of Direcció General de Memòria Democràtica, Departament de Justícia of Generalitat de Catalunya and the archaeology private company ATICS in charge of carrying out the intervention. We are grateful to Dr. Paloma Sevilla and Esther Navarro (Laboratory of Palaeontology of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid) for their disposition and support on bone sample processing, and Laura Tormo, Marta Furió, Ana Bravo and Cristina Paradela (Laboratory of Non-Destructive Techniques of the MNCN-CSIC) for their professional work, time spent on the study of samples, patience and helpful advice. We are also grateful to Esther Medina archaeologist for the pictures in Table 1.

Funding

Aida Gutiérrez, Margarita Salas Grant, Next GenerationEU, Ministerio de Universidades I1979-2AS375 (I1979) (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales-CSIC). Iván Rey-Rodríguez, Axudas de apoio á etapa de formación posdoutoral grant (ED481B-2023-040), from the Consellería de Cultura, Educación, Formación Profesional e Universidades (Xunta de Galicia). Yolanda Fernández-Jalvo, PID2021-126933NB-I00 of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

***Aida Gutiérrez: *** conception and design of the work, analysis of data, interpretation of data, drafting the work, reviewing the work, final approval or the version to be published.***Iván Rey-Rodríguez: *** conception and design of the work, analysis of data, interpretation of data, reviewing the work, final approval or the version to be published.***Alba Macho-Callejo: *** analysis of data, reviewing the work, final approval or the version to be published.***Núria Armentano: *** sample management, reviewing the work, final approval or the version to be published.***Yolanda Fernández-Jalvo: *** analysis of data, interpretation of data, drafting the work, reviewing the work, final approval or the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the General Directorate of Democratic Memory (Catalonia Government) and all techniques used here are in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulation of Catalonian law of Democratic Memory (Pla de fosses de la Generalitat de Catalunya). The protocols from MNCN-CSIC were also approved and the informed consent was obtained from the Catalonia Government to carried out these analysis and project. The Catalan Government gave permission to analyse the ribs (the least valuable skeletal element to identify the victim, but the closest to the intestinal tract) of these four individuals and cut them if necessary.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gutiérrez, A., Rey-Rodríguez, I., Macho-Callejo, A. et al. Non-invasive image study of bone bioerosion in Spanish Civil War lime graves. Sci Rep 16, 2795 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32729-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32729-w