Abstract

Understanding long-term land-use changes and their ecological consequences is essential for managing fragile artificial oasis systems in arid regions. This study analyzes annual land-use/land-cover (LULC) dynamics in the Alar Reclamation Area (northwestern China) from 1990 to 2019 using multi-temporal Landsat imagery, maximum NDVI composites, and a supervised SVM classifier. We produced annual LULC maps, quantified area changes and transition matrices, computed landscape pattern metrics (e.g., patch density, edge density), detected abrupt change points, and evaluated ecological risk using a landscape disturbance–vulnerability framework. Socioeconomic and climatic drivers (population, agricultural production value, cotton price, temperature and precipitation) were integrated to explain observed transformations and used in CA–Markov scenario simulations. Key findings: (1) cultivated land, orchards and construction land expanded substantially (net increases of 1147.2 km², 674.2 km² and 36.5 km², respectively), largely at the expense of unused land and natural vegetation; (2) a structural turning point occurred around 2005, associated with policy and market drivers; (3) landscape fragmentation increased, and ecological risk concentrated in reclamation belts adjacent to the Tarim River; (4) scenario simulations show that high-intensity development would markedly raise ecological risk, whereas conservation-oriented management can mitigate risk. The study identifies trade-offs between agricultural development and ecosystem stability, highlights salt-crust degradation and increased erosion as key ecological concerns, and provides spatially explicit evidence to inform land-use planning. Limitations include reliance on medium-resolution imagery and limited in-situ measurements; we therefore recommend future integration of higher-resolution imagery and process-based erosion monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Land-use and land-cover (LULC) change is a dominant driver of terrestrial environmental dynamics and is of particular concern in arid and semi-arid regions where ecosystem resilience is inherently low1. In such water-limited systems, modest expansions of irrigated agriculture or alterations in land management can produce large effects on hydrology, soil stability, dust emission, and biodiversity. Artificial oases created by irrigation and reclamation therefore represent socio-ecological mosaics in which human management and biophysical constraints interact closely2.

Land use change3 is a major driver of ecological transformation in arid regions and plays a key role in global environmental change. Remote sensing provides an efficient approach to monitor land cover and vegetation dynamics over large spatial scales4, enabling quantitative analysis of these changes.

Remote sensing and landscape metrics have become standard tools for monitoring LULC dynamics and assessing their ecological consequences5. Recent technical advances6—continuous Landsat archives, improved surface reflectance products, robust cloud masking, compositing strategies7 (e.g., maximum NDVI composites), and machine-learning classifiers8 (SVM, RF, deep learning)—have made it feasible to reconstruct annual land-cover time series over multi-decadal periods and to analyze both compositional and configurational changes. Parallel methodological progress in landscape ecology and ecological risk assessment allows integration of spatial metrics with vulnerability and disturbance indices to evaluate potential ecological impacts of land-use change9.

Despite these advances, important research gaps remain for artificial oasis systems in northern Xinjiang and similar arid regions. Many published studies10 focus on single time snapshots or a limited number of multi-year comparisons, which can obscure the timing of internal category transitions and key inflection points. Few studies11 explicitly combine annual LULC reconstruction, landscape pattern metrics, abrupt change detection, socio-economic driver attribution, and scenario-based simulation within a single integrated framework tailored to oasis reclamation settings. Moreover, ecological issues that are specific to arid soils12—most notably the formation and degradation of surface salt crusts and their role in sediment stability—are often under-emphasized in broader LULC studies.

To address these gaps, this study reconstructs annual LULC maps (1990–2019) for the Alar Reclamation Area using harmonized Landsat composites and an SVM classifier, quantifies area and structural transitions with transition matrices and landscape metrics, detects abrupt change points, and investigates driving factors (climatic and socioeconomic). We further apply CA–Markov scenario simulations to examine potential future ecological risk trajectories under alternative development pathways. By combining continuous time-series mapping with landscape-centric ecological risk assessment and scenario simulation, the study advances both methodological integration and applied relevance for land management in artificial oasis systems.

Artificial oasis zones in northwestern China typify these challenges. These regions have experienced extended periods of reclamation and agricultural intensification driven by socio-economic incentives, market fluctuations13 (e.g., cash crop prices), and infrastructure investment. Simultaneously, the fragile surface conditions—characterized in many places by salt crusts and loose sediments—make the landscape vulnerable to wind erosion and desertification when protective surface features are disturbed. Despite this, the combined examination of continuous LULC dynamics, landscape pattern change, abrupt transition detection, and integrated driver analysis remains limited for many oasis reclamation areas.

Recent empirical work demonstrates that vegetation indices14 (e.g., NDVI) in arid regions respond strongly to precipitation variability during the growing season, while temperature and water-availability controls modulate phenology and productivity. Studies using long-term satellite records in arid basins have documented both greening associated with irrigation expansion and browning related to drought or land degradation, illustrating that LULC and climate drivers often act together. Methodologically, multi-temporal composites combined with machine-learning classifiers and landscape metrics enable detection of subtle transitions and fragmentation processes that have direct ecological implications. Building on these developments, our study synthesizes multi-year remote sensing, landscape ecology, and driver analysis to isolate how policy-driven reclamation and climatic variability jointly shape vegetation and landscape stability in an artificial oasis context.

This study addresses these gaps by providing a systematic, multi-faceted assessment of land use dynamics and ecological implications in a typical artificial oasis in northwestern China over the period 1990–2019. Specifically, we implement a harmonized workflow that includes (1) annual land-cover mapping using multi-temporal Landsat composites and a SVM classifier calibrated with high-resolution imagery and Orchard land observations; (2) landscape-pattern analysis capturing both composition and configuration metrics (e.g., patch density, mean patch size, edge density) to quantify structural change; (3) detection of abrupt transitions and inflection points in temporal trajectories to separate periods of incremental change from policy- or market-driven reorganizations; and (4) multi-source driver analysis integrating meteorological records, socio-economic time series (population, agricultural production value, cotton prices), and spatial explanatory variables through CA–Markov modeling and contribution assessment.

The contributions of this work are threefold. First, by producing an annual LULC time series over three decades, we isolate temporal pathways and turning points that are not evident from conventional snapshot studies. Second, by coupling pattern metrics with change detection and scenario-based CA–Markov simulation, we link historical trajectories to plausible future pathways and examine their ecological consequences spatially. Third, by explicitly addressing the ecological implications of land change—most notably the degradation of salt crusts and enhanced soil erosion risk—we provide actionable insight for land-use planning and ecological protection in oasis environments. The study thereby advances methodological integration (classification → landscape metrics → driver attribution → scenario simulation) and yields policy-relevant evidence about the trade-offs between agricultural development and ecological security in arid reclamation systems.

This study addresses the identified gaps by pursuing four specific objectives:

-

1.

To produce an annual, harmonized LULC time series (1990–2019) for the Alar Reclamation Area using MVC NDVI composites and an SVM classifier, validated by Gaofen-2 imagery and Orchard land observations.

-

2.

To quantify LULC composition and configuration changes using area statistics, transition matrices, and landscape metrics (patch density, mean patch size, edge density) and to identify spatial hotspots of change.

-

3.

To detect abrupt change points and temporal inflection in land-use trajectories and to link these to socioeconomic and climatic covariates.

-

4.

To assess landscape ecological risk by integrating landscape disturbance metrics with vulnerability indicators and to simulate future risk under alternative CA–Markov scenarios.

These objectives combine continuous annual mapping, structural landscape analysis, driver attribution, and scenario simulation—an integrated approach that is infrequently applied in artificial oasis settings.

By integrating annual time-series mapping, landscape pattern analysis, driver attribution and scenario simulation, the study contributes methodologically to remote-sensing-based ecological risk assessment. Practically, the spatially explicit results identify areas of highest ecological vulnerability (e.g., salt-crust degradation zones and highly fragmented patches), providing evidence to guide land-use zoning, erosion control, and water management policies in artificial oasis systems.

Materials and methods

Study area

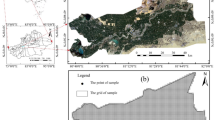

Alar Reclamation Area is located in Aksu Prefecture, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, at the intersection and transition zone of the Taklamakan Desert and the Tianshan Mountains. Its geographical coordinates are 80° 30′~81° 58′ E, 40° 22′~40° 57′ N (Fig. 1), with a total area of 4105.92km2. The Alar Reclamation Area, located in Aksu Prefecture, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, is characterized by a unique desert oasis ecosystem. This area lies at the intersection of the Taklamakan Desert and the Tianshan Mountains, with a total area of 4105.92 km². The region experiences harsh climatic conditions, with extreme temperatures, low precipitation, and high evaporation rates. The landscape is dominated by vast cotton plantations, but land use changes over the past decades, particularly in agriculture and urban expansion, have significantly impacted the environment, leading to issues such as salt crust destruction, soil erosion, and biodiversity loss. This study investigates these transformations in depth, offering insights into their ecological and socio-economic consequences. The Alar Reclamation Area has a relatively flat terrain and variable weather, often experiencing disasters such as sandstorms, dust, and frost. It experiences low precipitation and high evaporation throughout the year; The ecosystem belongs to the desert oasis type, and the soil surface often has a layer of salt crust to prevent soil moisture evaporation; The planting structure in the reclamation area is single, with a large area of cotton planted.

The Alar Reclamation Area is a representative artificial oasis on the edge of the Taklamakan Desert that has experienced large-scale irrigation and reclamation since the late 20th century. Its location, irrigation practices, and economic reliance on cotton make it suitable for studying how agricultural expansion interacts with fragile desert surface processes. The period 1990–2019 was selected for three reasons: (1) a continuous and consistent Landsat surface reflectance archive is available from 1990 onward, enabling annual mapping; (2) the period includes distinct policy and market phases (early reclamation, rapid expansion in the 1990 s, policy-driven intensification around 2004–2006) that allow detection of abrupt structural changes; and (3) a 30-year span provides sufficient temporal depth to quantify long-term trends and to perform scenario-based simulation grounded in historical transition dynamics.

Remote sensing data sources and processing

Remote sensing data were obtained from the USGS Earth Explorer website (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/), covering the Alar Reclamation Area from 1990 to 2019 (orbital number 146/32, spatial resolution 30 m). Only images with cloud coverage below 40% were selected, totaling 259 scenes. The cloud coverage and annual number of images for each image are shown in Fig. 2. From Fig. 2, it can be seen that the cloud coverage of each image is mostly below 10%. Due to the continuous updates of the Landsat series sensors, this article selected Landsat 5 from 1990 to 1998, Landsat 7 from 1999 to 2012, and Landsat 8 from 2013 to 2019 to avoid errors caused by multi-sensor synthesis, and there are at least 3 images per year.

To improve the accuracy of land use classification, several factors were considered, including elevation, slope, aspect, distance from highways, railways, and water systems. These factors contribute to the model’s ability to distinguish between land use types by reflecting the environmental characteristics of the study area. The elevation data, for example, provides insights into the terrain’s influence on vegetation growth, while slope and aspect data help in understanding how these factors affect water runoff and soil erosion. These parameters were carefully selected for their relevance to land use classification accuracy, and their influence was quantified in subsequent analyses.

Landsat TM/ETM+/OLI surface reflectance products (LEDAPS for Landsat 5 and LaSRC for Landsat 8) were downloaded from USGS EarthExplorer. Initial scene selection excluded scenes with reported cloud cover > 40% to reduce processing load; subsequent per-pixel QA band filtering (QA_PIXEL/QA_STATUS) and cloud/shadow masks were applied to remove contaminated pixels. After QA masking, we required at least three valid scene observations per year and per target month where possible; if fewer observations existed in a calendar month, we extended the compositing window to adjacent months within the growing season to ensure representative coverage. For each year, we computed monthly NDVI and used a Maximum Value Composite (MVC) of NDVI across months to generate an annual MVC image that emphasizes peak-greenness and reduces residual cloud/shadow noise. Radiometric normalization and cross-sensor harmonization were implemented following established methods to minimize systematic sensor differences. All images were geometrically registered to a common projection and resampled to 30 m resolution.

In order to further improve the accuracy of land use classification, all images are preprocessed one by one, including radiometric calibration, atmospheric correction, registration, cropping and other operations, and the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) of each scene image is extracted.

Synthesize the maximum NDVI values of images from each month each year to obtain the scenario with the most comprehensive vegetation coverage year by year. Improve classification accuracy from the perspective of data sources. The synthesis process of related images is shown in Fig. 3. From the comparison of local magnification before and after image synthesis, it can be seen that the vegetation coverage of the image after combining the maximum NDVI values is higher, which is conducive to interpretation and classification.

Although the study period spans 1990–2019, we constructed an annual LULC time series by synthesizing all available Landsat scenes per year (259 scenes total across the study period; at least 3 valid observations per year were required). Monthly NDVI composites were produced and then aggregated into annual maximum NDVI composites to improve phenological comparability and cloud removal. This annualized approach provides sufficient temporal resolution to capture both gradual vegetation trends and abrupt changes (e.g., policy-driven inflection points such as the 2005 breakpoint identified in our analysis), contrary to analyses that rely on a small number of snapshot years.

Land use classification method

Referring to the statistical yearbook of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (1990–2019) on the land use area of the First Division and the existing land use classification system in Xinjiang15, combined with the characteristics of land use types in the Alar Reclamation Area, the land use types in the study area are divided into six categories. The surface features, image features, and Orchard land photographs of each land use type are shown in Table 1.

Taking 2019 as an example, based on the classification system and interpretation criteria of the Alar Reclamation Area, classification samples of various land use types were established (Fig. 4), with a total of 1,024,951 classification pixels. Based on various classification samples, supplemented by collected relevant statistical data, high-resolution images, and Orchard land investigations, the SVM classification method in supervised classification is used for land use classification, and appropriate post-processing (such as small patch removal, filtering, clustering, etc.) is performed on the classified images to ensure an overall classification accuracy of over 90% and a Kappa coefficient of over 0.9.

In this study, the SVM method was chosen for land use classification due to its ability to handle high-dimensional data and its effectiveness in distinguishing land use classes. The kernel type used was a radial basis function (RBF), and the tuning parameters (C = 1, γ = 0.1) were selected based on cross-validation. Although newer methods like Random Forest or deep neural networks may offer improvements, SVM remains a robust option for the scale and temporal scope of this study, providing a balance between classification accuracy and computational efficiency. However, future research could consider experimenting with advanced classification techniques such as Random Forest or deep learning models to compare performance.

Analysis methods for land use change

Analyze the land use changes in the Alar Reclamation Area from three aspects: area changes, type transformations, and spatial dynamic changes of various land use types. Based on the spatial analysis function of ArcGIS, analyze the classified images of the starting and ending years of each time period, and create transition matrices and spatial dynamic distribution maps of changes in various land use types.

Classification accuracy was evaluated using independent validation samples and confusion matrices. In addition to Overall Accuracy (OA) and Kappa, we calculated user’s and producer’s accuracies for each class and the quantity disagreement/allocation disagreement metrics to separate quantity vs. spatial allocation errors (Bi et al.16). Main sources of classification error include: (1) spectral confusion between bare/unused land and construction land during dry seasons; (2) seasonal phenological variation and crop rotation leading to temporal misclassification; (3) mixed pixels along narrow Orchard land boundaries; and (4) limited sample density for some rare classes. To mitigate these errors we synthesized maximum NDVI composites, incorporated topographic and proximity predictors (elevation, slope, distance to water/roads), and used Gaofen-2 imagery and Orchard land photos for sample verification in 2019. Nevertheless, these error sources contribute to uncertainty in both area estimates and derived landscape metrics; we therefore focus interpretation on consistent spatial patterns and relative changes.

We report Kappa together with OA and class-level user’s/producer’s accuracies because Kappa provides a standardized measure of agreement adjusted for chance and remains widely used in LULC studies, facilitating comparison with previous work. However, because Kappa can be sensitive to class prevalence, we also report quantity disagreement and allocation disagreement to more fully describe the nature of classification errors.

Collection and processing of land use change analysis data

To improve the accuracy of land use classification, elevation, slope, aspect, distance from highways, railways, roads, and water systems, temperature, precipitation, population, etc. are selected GDP The land use change analysis was carried out on 15 influencing factors including the whole society’s fixed assets investment, the primary industry, the gross agricultural product and the cotton price.

Elevation data were obtained from the International Science Data Mirror website of the Computer Network Information Center at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The elevation data was resampled in ArcGIS to obtain slope and aspect information, and the distance from each grid to highways, railways, roads, and water systems was obtained using the near tool; The temperature and precipitation data were obtained from the China Meteorological Science Data Sharing Network, and the spatial distribution of temperature and precipitation was obtained through inverse distance weight (IDW) heavy space interpolation; Population GDP The fixed assets investment, primary industry, gross agricultural product and cotton price of the whole society were obtained from the Statistical Yearbook of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (1990–2019), and the statistical data with Alar reclamation area as the basic statistical unit were distributed to grid units using the multi factor weight distribution method.

Results

Land use changes in Alar reclamation area

Land use area changes

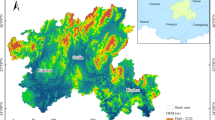

From 1990 to 2019, the areas of cultivated land, garden land, water bodies, and construction land in the Alar Reclamation Area increased continuously, with total net increases of 1147.19 km², 674.19 km², 107.58 km², and 36.54 km², respectively (Figs. 5 and 6a). In contrast, forest and Natural Natural Grassland and unused land decreased by 33.67 km² and 1931.83 km², respectively. The annual average change rate was highest during 1990–1995 (Fig. 6b), indicating the most rapid land use change in the early reclamation period. Spatially, expansion of cultivated and garden lands mainly occurred along the Tarim River, whereas peripheral areas exhibited relatively minor changes, reflecting the influence of water availability and irrigation infrastructure. These trends highlight the combined effects of agricultural development and human-induced land reclamation on landscape structure.

Landscape metrics indicate an increase in fragmentation: patch density (PD) and edge density (ED) of cultivated land increased by 23% and 34%, respectively, over the study period. This suggests that formerly continuous unused land was subdivided and converted into multiple smaller land parcels. These metrics quantitatively illustrate the ecological implications of human land management.

We computed patch density (PD), mean patch size (MPS), and edge density (ED) for each land-use class annually. Over 1990–2019 PD and ED for cultivated land increased by 23% and 34% respectively, indicating heightened fragmentation of formerly continuous unused land. Correlation analysis between annual maximum NDVI and seasonal precipitation anomalies shows a statistically significant positive relationship (r = 0.46, p < 0.01) during the main growing season, whereas correlation with mean growing-season temperature is weaker (r = 0.23, p < 0.05). Spatially, areas with increasing NDVI coincide with irrigated reclamation belts, whereas NDVI decline occurs in peripheral areas subject to crust disturbance and wind erosion. These spatial statistics provide quantitative support that both climatic variability (precipitation) and anthropogenic reclamation shape vegetation dynamics.

Our correlation and spatial overlay analysis indicate that annual MVC NDVI exhibits the strongest positive responses to growing-season precipitation anomalies, consistent with water limitation in arid systems. Temperature influence was secondary and sometimes non-linear: warm conditions increased NDVI only when soil moisture was adequate. Additionally, irrigation intensification masks climatic water stress locally—producing greening signals in irrigated Orchard lands even during drier years—while peripheral non-irrigated areas exhibit NDVI declines. These patterns reflect the coupled influence of climate and human water management and are consistent with recent remote-sensing studies in arid basins.

Land use distribution in 1990–2019 derived from Landsat TM images using SVM classification. Colors represent different land cover types as described in Table 1.

Land use type conversion

The transformation of land use types is summarized in Table 2. Cultivated land gained 1516.19 km² through conversion from unused land, while losing 368.99 km² to other uses, resulting in a net increase of 1147.19 km². Forest and Natural Natural Grassland decreased by 39.63 km², mostly converted into arable land. The expansion of water bodies primarily occurred via conversion from unused land, and construction land increased mainly by converting arable land. Unused land decreased by 1934.48 km² due to conversion into cultivated and garden land.

We further incorporated the persistence of land use categories, accounting for areas remaining in the same category across multiple years. This allowed a more accurate representation of land use transitions, highlighting areas of stable agriculture versus highly dynamic zones subject to policy-driven reclamation.

The characteristics of changes in land use types vary in different time periods (Fig. 7). From 1990 to 2000, except for unused land, the net change in area of all land use types increased; From 2000 to 2010, the net changes in forest, Natural Natural Grassland, orchard, and unused land area all decreased, with values of −14.37 km², −272.63 km², and − 536.23 km², respectively; From 2010 to 2019, the net change in forest, Natural Natural Grassland, water bodies, and unused land area decreased; From 1990 to 2019, the net changes in cultivated land, garden land, and unused land were the most significant, at 1147.19 km ², 674.19 km ², and − 1931.84 km ², respectively.

Spatial dynamics analysis

We first analyze land use change between 1990 and 2000, followed by changes during 2000–2010 to highlight temporal dynamics. Spatial analysis (Fig. 8) reveals that land reclamation from 1990 to 2000 was concentrated in the central region, while 2000–2010 saw substantial mutual transformation between cultivated land, forests, Natural Natural Grasslands, and gardens along the Tarim River. From 2010 to 2019, new cultivation of unused land was mostly in the northeast and southeast. NDVI trends correlate with these spatial patterns: irrigated areas exhibited increasing vegetation greenness, whereas peripheral regions affected by crust formation and wind erosion showed declining NDVI. Correlation analysis between NDVI and seasonal precipitation revealed a significant positive relationship (r = 0.46, p < 0.01), while temperature effects were weaker (r = 0.23, p < 0.05), suggesting that precipitation is the dominant climatic driver of vegetation changes.

The dynamic changes of land use in Alar Reclamation area in different time periods. (A) Cropland, (B) Orchard Land, (C) Construction land, (D) Waterbody, (E) Bare land, (F) Grassland. A in the figure represents Farmland; B stands for Forest and Grass Land; C is Orchard land; D is the water body; E Construction land; F stands for Unused Land.

Accuracy assessment

The simulated 2010 land use map closely matches observed conditions (Fig. 9), with minor discrepancies in construction and garden land due to new urban planning policies. Overall accuracy (OA) was 89.82%, and the Kappa coefficient was 0.85. To enhance assessment rigor, quantity disagreement and allocation disagreement metrics were also applied17, providing a detailed breakdown of misclassification types and highlighting spatial allocation errors. This comprehensive accuracy evaluation confirms the reliability of land use change detection.

While the overall accuracy (OA) of the classification for the Alar Reclamation Area in 2010 was 89.82% with a Kappa coefficient of 0.85, it is important to acknowledge that the Kappa coefficient may not fully capture the nuances of land use change accuracy. Therefore, to improve the objectivity of the accuracy assessment, we employed the quantity disagreement and allocation disagreement metrics as described by Zhou, et al.18. These metrics provide a more detailed breakdown of misclassification types, offering insight into both the quantity of misclassification and the spatial allocation errors, which is crucial for understanding the accuracy of land use change detection.

By establishing a confusion matrix, further accuracy evaluation was conducted on the results of the 2010 simulation (Table 3). From Table 3, it can be seen that the deviation in simulation accuracy is mainly due to the impact of the 2005 urban planning policy on the construction of new industrial parks, resulting in an increase in construction land area and lower accuracy of garden and construction land. However, overall, the classification accuracy (OA/%) of Alar Reclamation Area is 89.82%, with a Kappa coefficient of 0.85, indicating that the accuracy of the simulated land use change results in this study is reliable.

Discussion

Overview of major LULC dynamics and temporal characteristics

Our analysis reveals a consistent expansion of cultivated land, orchards, water bodies and construction land between 1990 and 2019, with concomitant decreases in forests, Natural Natural Grasslands and unused land19. Two temporal features deserve emphasis. First, the trajectory is not monotonic: early-stage rapid growth (e.g., 1990–1995) reflects initial reclamation efforts and agricultural consolidation, whereas the pronounced structural shift detected around 2005 indicates a policy- and market-driven reorganization of land systems—consistent with intensified irrigation investment and rising returns to cash crops. Second, spatially the most intensive changes are concentrated along the river corridor and within reclamation belts, demonstrating strong hydrological control over feasible land conversion and the tendency of development to cluster where water access and infrastructure exist.

Several studies20 in Central Asia and Xinjiang report analogous trends of irrigated expansion and associated vegetation greening in oasis corridors; however, they also warn of concomitant ecological costs such as soil salinization and fragmentation. Our findings echo this pattern: while cultivated areas increased and NDVI locally rose in irrigated belts, fragmentation and salt-crust loss produced degradation and NDVI decline in adjacent areas. Compared to studies21 limited to snapshot analyses, our annual time-series reveals both the timing of initial rapid reclamation (1990–1995) and the later structural shift in ~ 2005—linking these to market and policy drivers more precisely than prior work. This integrated view strengthens inference about causality because we combine temporal breakpoint detection with driver time series and scenario projection.

Comparing composition (area changes) and configuration (patch metrics) reveals that ecological risk is driven not only by the amount of land converted but also by how conversion alters landscape structure. For example, increases in patch density and edge density in formerly contiguous unused lands indicate fragmentation processes that tend to reduce habitat connectivity and increase exposure of fine sediments to wind erosion. These structural changes frequently precede observable declines in ecosystem function and hence constitute early warning signals for escalating ecological risk.

The highest annual land use change rate occurred during 1990–1995, while the major cumulative turning point was observed in 2005, corresponding to regional agricultural policy changes. This abrupt change in 2005 was driven by the implementation of the Western Development Strategy and associated agricultural subsidies that promoted cotton cultivation and irrigation development.

Mechanisms linking socio-economic drivers to landscape outcomes

Quantitative driver analysis (CA–Markov contribution and correlation analysis) indicates that population growth, agricultural production value, and cotton price volatility are primary proximal drivers of land expansion22. This reflects a plausible causal chain: higher market incentives (cotton prices) and improved profitability induce conversion of marginal lands into cropland; population pressures and mechanization lower the transaction costs of reclamation and thereby increase conversion rates. Moreover, state-level policies and infrastructure projects amplify these market signals by lowering barriers to land development. Importantly, the timing of the 2005 breakpoint aligns with observed policy and market changes in the region (agricultural promotion, irrigation projects, and enhanced access to agricultural machinery), suggesting that external drivers can precipitate structural regime shifts when combined with favorable local conditions.

These socio-economic drivers interact with environmental constraints. The location of expansion—predominantly along the Tarim River corridor—underscores that water availability constrains feasible land conversion; hence, driver effects are contingent upon hydrological accessibility. This spatial heterogeneity matters for intervention design: restricting conversion in high-risk hydrologically sensitive zones yields disproportionate ecological benefits compared to uniform policy measures.

Salt crust degradation, soil erosion, and downstream ecological implications

A particularly salient ecological consequence emerging from our land-use analysis is the degradation of surface salt crusts. In the natural desert environment, salt crusts stabilize loose sediments, reduce surface evaporation, and suppress particulate emissions. Intensive tillage, irrigation-induced salinization cycles, and mechanical disturbance from reclamation disrupt crust integrity, exposing fine sediments to wind forces and increasing potential dust emission and soil loss. Our spatial overlay of expanded cultivation and high erosion-susceptibility zones shows a strong spatial concurrence, implying a mechanistic link between reclamation-driven disturbance and increased erosion risk.

The broader consequences are manifold. Increased dust emission can reduce air quality and transport salts and particulates that further degrade distant ecosystems. Loss of topsoil reduces the long-term productivity of newly reclaimed lands, creating a perverse outcome where short-term gains in cultivable area lead to long-term declines in sustainability. These dynamics emphasize the need for preventive measures—such as conservation tillage, protective vegetation strips, and the preservation of crusted surfaces in high-risk areas—rather than post-hoc remediation.

Scenario outcomes and policy relevance

Scenario simulations illuminate the range of plausible futures under alternative development paradigms23. The high-intensity development scenario projects substantial expansion in high-risk areas and accelerated fragmentation, whereas the conservation-oriented scenario demonstrates how targeted land-use controls and ecological protection can stabilize and in some locations reduce ecological risk. Importantly, the marginal benefits of conservation measures are spatially uneven: restricting conversion in key erosion-prone or hydrologically sensitive patches yields outsized improvements in landscape stability.

For policy, three implications follow directly. First, spatially differentiated regulation—that prioritizes protection of high-risk patches and enforces buffer zones along sensitive corridors—can achieve ecological gains while allowing productive use elsewhere. Second, market-based instruments (e.g., compensation for conservation, water pricing aligned with ecological objectives) could help realign incentives causing deleterious conversion. Third, integration of ecological considerations into agricultural extension (promotion of less-disturbing cropping systems, reduced tillage, salinity management) is essential to prevent crust loss and sustain productivity.

Methodological considerations and uncertainties

While the study combines multiple strands of evidence, several limitations affect interpretation24. First, Landsat-based classification at 30 m resolution is subject to mixed-pixel issues, especially where narrow Orchard land boundaries or linear features (ditches, Orchard land margins) exist. Second, the Maximum Value Composite NDVI and SVM classification approach improve temporal consistency and class separability, but do not fully resolve spectral confusion among certain classes25 (e.g., bare soil vs. built surfaces in dry seasons). Third, the CA–Markov model captures transition probabilities and neighborhood effects but assumes stationarity in transition mechanisms; therefore, abrupt future policy shifts could produce outcomes not captured by historical transition parameters. Fourth, direct Orchard land-based measures of salt crust integrity and erosion rates are limited in this study; integrating in-situ erosion and soil structural measurements would strengthen causal inference.

To gauge robustness, we assessed classification accuracy with confusion matrices, examined landscape metric sensitivity to classification uncertainty, and checked scenario sensitivity to alternative parameterizations. These checks suggest qualitative robustness of key conclusions (direction and spatial pattern of risk increase), although precise quantitative magnitudes of area change and risk indices may vary with finer-resolution data and alternative weighting schemes.

Several limitations affect the study results. (1) Classification uncertainty: despite high overall accuracy, medium spatial resolution (30 m) produces mixed-pixel effects in narrow Orchard lands and along linear features. (2) Sensor harmonization: while radiometric normalization was applied, subtle cross-sensor differences may remain. (3) Limited Orchard land validation: Orchard land survey points and GF-2 validation imagery were used for 2019, but extensive ground truth data across all years are not available. (4) CA–Markov assumptions: scenario simulations assume transition rules inferred from historical dynamics; abrupt future policy shifts or climate extremes could produce divergent outcomes. (5) Ecological risk weighting: the ERI depends on chosen landscape metrics and weights; alternative weightings may change absolute ERI values though spatial patterns proved qualitatively robust in sensitivity checks. We discuss these uncertainties when interpreting results.

In particular, single-sensor reliance (Landsat series) and limited ground-truth samples restrict direct generalization; we therefore recommend future studies incorporate Sentinel-2, GF-series, or UAV surveys for higher spatial fidelity and expanded Orchard land validation to reduce classification uncertainty.

Remote sensing provides powerful long-term coverage but has constraints. At 30 m resolution, narrow Orchard lands and linear irrigation channels may be aggregated into mixed pixels, reducing class separability. The MVC approach reduces cloud noise and stabilizes phenological representation but cannot correct for within-year crop rotation, fallow cycles or disease episodes that alter reflectance. Atmospheric correction and cross-sensor harmonization mitigate but do not fully remove systematic biases. We therefore interpret NDVI trends with these caveats in mind and use complementary metrics (landscape fragmentation, Orchard land verification) to strengthen inference.

Rather than simply describing area changes, we interpret these results mechanistically: rising cotton prices and policy incentives increased reclamation of unused land, which produced new agricultural patches that fragment contiguous surface crusts; fragmentation enhanced wind exposure and crust breakdown, accelerating soil erosion and reducing long-term fertility. Management implications include prioritizing crust protection, controlling expansion in high-erosion zones, and promoting conservation agriculture practices (e.g., reduced tillage, vegetative wind breaks) to maintain productivity.

Practical applications

The spatial ERI maps and hotspot analyses can inform (1) ecological zoning and targeted erosion control (prioritize high-ERI patches), (2) land-use planning to limit reclamation in hydrologically sensitive corridors, (3) water allocation strategies that consider ecological consequences of irrigation expansion, and (4) decision support for policy testing—using scenario simulations to evaluate trade-offs between production and ecological protection.

Directions for future research

Future work should pursue three priorities. (1) Higher-resolution multi-sensor fusion (e.g., combining Sentinel-2, GF-series, and UAV imagery) could improve mapping of small Orchard lands, Orchard land margins, and crusted surfaces. (2) Process-based modeling that couples hydrology, soil-surface physics, and land-management practices would better quantify erosion trajectories and feedbacks between irrigation, salinity, and productivity. (3) Policy-experiment and social-ecological studies examining farmer decision-making under price, subsidy and water governance regimes would improve modeling of future land-use trajectories and the design of effective interventions.

Conclusion

This study has reconstructed annual LULC dynamics in the Alar Reclamation Area (1990–2019) and linked those dynamics to landscape structure, ecological risk, and driving forces. Key conclusions are:

-

1.

Land-use change patterns. Cultivated land, orchard land and construction land expanded substantially, primarily converting unused land and partially replacing natural vegetation.

-

2.

Landscape structure and ecological risk. Fragmentation increased (higher patch density and edge density) and ecological risk concentrated in reclamation belts; salt-crust degradation and increased soil erosion are major ecological concerns.

-

3.

Drivers and turning points. A structural turning point was detected near 2005, driven predominantly by socio-economic factors (population growth, agricultural production value, cotton prices) amplified by policy and irrigation infrastructure. Climatic variation (precipitation) modulates vegetation response but irrigation alters local sensitivities.

-

4.

Management implications. Conservation-oriented land-use control and targeted erosion protection measures can substantially reduce ecological risk compared to unregulated high-intensity development.

Limitations and future work. Results are subject to classification and model uncertainties (30 m resolution, limited historical ground truth). Future research should incorporate higher resolution imagery (Sentinel-2, GF), process-based erosion models, and expanded field monitoring to refine risk assessment and to inform adaptive management.

Overall, the integrated time-series, landscape, and scenario approach provides spatially explicit evidence to support sustainable land-use planning in artificial oasis systems.

Data availability

The datasets used or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Huang, J. & Wang, Y. Ventilation potential simulation based on multiple scenarios of land-use changes catering for urban planning goals in the metropolitan area. Journal Clean. production (Dec 10) 483, 144301 (2024).

Joloro, H., Tilaki, G. A. D., Memarian, H. & Kooch, Y. Spatial–temporal assessment of land use changes and forest restoration on carbon sequestration using the invest model in central alborz, iran. Modeling Earth Syst. Environment https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-025-02452-6 (2025).

Sajida, N., Yang, C., Ahsan, W. A. & Wang, Z. Integrating land use changes, biomass dynamics, and water quality for wetland restoration: a case study of Chaohu lake Shibalianwei wetland, China. J. Geoscience Environ. Prot. 13 (4), 27 (2025).

Fu, M., Jiao, L. & Su, J. Urban land system change: Spatial heterogeneity and driving factors of land use intensity in wuhan, China. Habitat Int. 159 (2025).

Ning, J., Li, P., He, X., Ren, X. & Li, F. Impacts of land use changes on the spatiotemporal evolution of groundwater quality in the yinchuan area, china, based on long-term monitoring data. Phys. Chem. Earth 136, 103722 (2024).

Duran-Bautista, E. H., Yalanda-Sepulveda, K., Martínez-Trivio, K. & Gamboa, J. Land-use changes impact responses of termite functional and taxonomic diversity in the colombian amazon. Biotropica https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.13366 (2024).

Fu, Y. et al. Distinct assembly patterns of soil antibiotic resistome revealed by land-use changes over 30 years. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58 (23), 11 (2024).

Bai, Y., Zhou, Y. & Feng, Q. Land use change and climatic-topographic factors drive Spatial heterogeneity of soil pH in karst watersheds of Southwest China. Catena 26, 1109540–1109540 (2025).

Kabisch, N., Selsam, P., Kirsten, T., Lausch, A. & Bumberger, J. A multi-sensor and multi-temporal remote sensing approach to detect land cover change dynamics in heterogeneous urban landscapes. Ecol. Ind. 99, 273–282 (2019).

Shen, S., Yue, P. & Fan, C. Quantitative assessment of land use dynamic variation using remote sensing data and landscape pattern in the Yangtze river delta, China. Sustainable Comput. 23 (Sep.), 111–119 (2019).

Ge, L. et al. Uncovering interactive impacts of climate extremes and land use change on soil erosion using a coupled RUSLE-OPGD framework. Catena 261, 109507–109507 (2025).

Zhao, L. et al. Land use/cover changes in the oriental migratory locust area of china: implications for ecological control and monitoring of locust area. Agriculture Ecosyst. & Environment 303, 107110 (2020).

Yao, R. et al. A novel grid-based technique for quantifying groundwater quality under land use/land cover changes to support improved groundwater management. J. Hydrol. 662 (PC), 133955–133955 (2025).

Wang, X. et al. Linking land use change, ecosystem services and human well-being: a case study of the Manas river basin of xinjiang, China. Ecosyst. Serv. 27, 113–123 (2017).

Pinto, B. R. et al. Changes in land use and buffaloes trampling effects on soil health in environmentally vulnerable areas of an Atlantic forest biome in Southern São Paulo State, Brazil. Geoderma Reg. 43, e01011–e01011 (2025).

Bi, Y. et al. The response of non-point source pollution to land use changes based on the SWAT and PLUS models in an agricultural river basin of Yangtze River, China. J. Hydrol. 663 (PB), 134331–134331 (2025).

Matsa, M., Mupepi, O., Musasa, T. & Defe, R. A gis and remote sensing aided assessment of land use/cover changes in resettlement areas; a case of ward 32 of mazowe district, zimbabwe. J. Environ. Management 276, 111312 (2020).

Zhou, J. et al. Transitions in slope runoff generation mechanisms induced by land use change in the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 261, 109517–261109517 (2025).

MAASHI, M. Forecasting land use changes in crop classification and drought using remote sensing. J. Arid Land. 17 (05), 575–589 (2025).

Changnon, S. A. & Demissie, M. Detection of changes in streamflow and floods resulting from climate fluctuations and land use-drainage changes. Clim. Change. 32 (4), 411–421 (1996).

Romero, H., Ihl, M., Rivera, A., Zalazar, P. & Azocar, P. Rapid urban growth, land-use changes and air pollution in santiago, Chile. Atmos. Environ. 33 (24–25), 4039–4047 (1999).

Wang, R. et al. A flood susceptibility prediction method for climate change scenarios driven by coupled land simulation and Spatiotemporal dual Convolution synergy. J. Hydrol. 664 (PA), 134366–134366 (2026).

Zhang, H., Zhou, Q., Yang, J. & Xiang, H. Change and driving factors of eco-environmental quality in Beijing green belts: from the perspective of nature-based solutions. Ecol. Ind. 166 (000), 12 (2024).

Gang, S., Kong, X., Jia, T., Lv, M. & Li, L. Analysis of the Spatiotemporal evolution and driving factors of land use change in Jinan springs area of the Northern karst region, China from 1986 to 2022. Discover Appl. Sci. 7 (4), 1–22 (2025).

Hu, B. et al. Driving factors of rural land-use change from a multi-scale perspective: a case study of the loess plateau in china. Land (2012). 14(3) (2025).

Funding

This study was supported by Scientific Research Project of Xichang University, titled “Land Use Change and Ecological Risk Assessment in Northwestern China Based on Remote Sensing Technology,” and the Project of Xichang University (No. LGLZ202301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**Qi Song: ** Writing—original draft and Writing—review & editing. **Lina Li: ** Conceptualization and Methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, Q., Li, L. Spatio-temporal land-use dynamics and landscape ecological risk assessment in an artificial oasis, Northwestern China. Sci Rep 16, 2836 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32741-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32741-0