Abstract

Patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing hemodialysis are at an increased risk of cardiovascular complications due to volume overload. Lung ultrasound (LUS) has emerged as a non-invasive tool to assess extravascular lung water (EVLW) and manage fluid excess. This study aimed to validate LUS in a relatively asymptomatic day-care dialysis population and to correlate it with clinical parameters, ECHO/IVC metrics. This prospective pre-post intervention study was conducted in a dialysis unit, enrolling 93 eligible hemodialysis patients. The fluid status of all patients was evaluated by clinical examination, lung ultrasound, inferior vena cava (IVC) indices, and echocardiography pre and post-dialysis. The mean age was 48.20 ± 13.81 years with male predominance (n = 66,71%). Only 28 patients (30%) had NYHA class III dyspnea. Edema and lung crackles were observed in 5 (5.4%) and 8 patients (8.6%), respectively. The Mean Lung USG B lines pre- and post -dialysis were 3.527 ± 4.636 and 0.484 ± 1.419, respectively. Pre-HD lung USG B-lines showed significant correlations with edema (p = 0.05) and echocardiographic parameters, such as E/E’ ratio (r = 0.35, p = 0.001), E velocity (r = 0.21, p = 0.04), and pulmonary pressure (r = 0.33, p = 0.001). A moderately positive correlation was also found between the maximum diameter of the IVC pre-dialysis and lung USG B-lines (P < 0.001). Lung USG is a promising technique for estimating EVLW in patients on dialysis. Significant correlations between pre-dialysis lung USG B-lines and echocardiographic measures of cardiac function, IVC maximum diameter and edema suggest a link between cardiac performance and volume status. This could complement clinical skills in determining dry weight.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is approximately 10%, accounting for more than 850 million individuals1. According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) studies, CKD is a major cause of worldwide mortality2. Volume overload is quite common in patients with CKD, especially end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Excess volume increases blood pressure and cardiac preload, leading to LV hypertrophy and congestive cardiac failure. Thus, it has been associated with increased cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality3. Rigorous volume control measures can potentially improve patients’ health and reduce mortality rates. However, accurate determination of the volume status of patients with end-stage kidney failure remains challenging. In fact, it still represents the “holy grail” of practicing renal physicians. Clinical evaluation of volume status has been conventionally led by history and physical examination, including grade of dyspnea, assessment of blood pressure (BP), jugular venous pressure measurement, presence of pedal edema, and lung crackles4. However, clinical evaluation has failed to accurately detect overhydration and interstitial edema in patients with ESRD5. The combination of isotope dilutional analysis and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry is probably the best method for ascertaining volume, fat, lean soft, and bone tissue mass composition in patients on hemodialysis(HD). However, their routine application is doubtful because of the exuberant cost and invasive nature of these methods. Several other diagnostic methods have been developed, including echocardiography and bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), which provide valid estimates of total tissue fluid content6,7. Of late, Point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS) has emerged as a useful volume assessment tool. Lung ultrasound (LUS) is an easy, radiation free, non-invasive procedure that can detect pulmonary congestion and aid in dry weight determination8. By assessing lung B-lines and inferior vena cava (IVC) parameters, one can have objective evidence for volume status9. Here, we aim to validate LUS in a relatively asymptomatic patients undergoing hemodialysis and tend to correlate it with echocardiographic and IVC metrics. The objectives of this study were to: (1) to determine the prevalence of lung congestion in ambulatory patients with ESRD undergoing day care hemodialysis using LUS. (2) To study the relationship between clinical signs and symptoms of volume overload (NYHA class of breathlessness, edema, and lung crackles) with POCUS (lung B lines with IVC collapsibility index) and echocardiographic parameters of cardiac performance (pre-HD).

Methodology

A single-centre prospective pre-post intervention study was conducted in full accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision) in the dialysis unit of Shree Krishna Hospital, Karamsad, which is a tertiary care teaching institute in western India. Second-year trainee doctor pursuing MD in internal medicine performed lung ultrasound and IVC collapsibility index of all patients pre and post-hemodialysis. She received two weeks of training under an intensivist who is a certified critical care bedside ultrasound expert. She performed 50 bedside ultrasounds of the lung examination under intensivist’s guidance in the critical care unit prior to this study. The USG images captured by her were stored in the machine which was later reviewed by her mentor-intensivist. 2-D Echocardiography and color Doppler were performed by a senior echocardiography technician pre and post-dialysis. We included all adult ambulatory patients with ESRD who were receiving regular day-care hemodialysis for > 3 months. Exclusion criteria were 1. Patients with ESRD who were breathless due to causes other than volume overload.2. Patients with primary lung pathology, such as ILD, lung fibrosis/collapse, persistent pleurisy, and pneumonectomy, even if they were on regular hemodialysis.3. Patients who skipped hemodialysis sessions during the previous 3 months or had any cardiac events, infective episodes, access complications, or hospitalization in the previous 3 months.

Study protocol: The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Bhaikaka University, Anand. Demographic data, clinical symptoms (dyspnea grading and pedal edema), blood pressure, presence or absence of lung crackles, and blood investigations of all participants were collected after written informed consent by the dialysis nurse. All patients underwent a LUS for B-lines using a low- to medium-frequency (3.5–5.0 MHz) curvilinear probe in different areas of both lung fields (28 sites) while in a supine position by a trainee doctor pre- and post-dialysis. This was done using Phillips Clearvue 350 ultrasound machine in a quiet examination room with controlled air temperature – 25°C. Curvilinear probe was placed vertically from the second to the fifth intercostal space on right hemithorax and from the second to fourth intercostal space on left hemithorax along parasternal, mid clavicular, anterior axillary and mid axillary lines (16 sites on right hemithorax and 12 sites on left hemithorax). The 28 sites were chosen because they provide a quantitative approach. Bed-side 2D echocardiography and color Doppler of all patients were performed in the left lateral position using a Philips Epiq 7c machine. LA volume, LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), early left ventricular filling velocity (E), LV filling pressure (E/E’), pulmonary pressure and LVEF were measured pre- and post -dialysis. LA volume was calculated in the apical two- and four-chamber views. The parasternal short and long axis along the apical view were used to measure the LV end diastolic volume. LV filling velocity(E) and late A wave were measured using pulsed-wave doppler in 4 chamber apical view. E/E’ was calculated using tissue Doppler. Pulmonary artery pressure was analysed in the parasternal long axis, short axis, and apical 4 chamber view using continuous wave (CW) Doppler. The LVEF was calculated using the biplane Simpson method. IVC diameter(inspiratory/expiratory) pre- and post-dialysis was also measured to assess intravascular volume using a phased array probe (2–8 MHz). IVC evaluation was performed in the subcostal view within 1.5 cm from the IVC -right atrial junction, just distal to the hepatic vein confluence. The B mode was used for the identification of the IVC, and later, M mode was applied. The IVC collapsibility index was calculated according to the following formula: collapsibility index = IVC max-IVC min/IVC max. Trainee doctor who performed POCUS were unaware of the patients’ clinical parameters and echocardiography indices. Similarly, the echocardiography technician was unaware of LUS findings (Fig. 1).

Statistical methods and analysis

The collected data were transformed into variables, coded, and entered in Microsoft Excel. Data were analysed and statistically evaluated using the SPSS-PC-25 version.

The normal distribution of different parameters was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and differences between the means of two groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Qualitative data were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and statistical differences between the proportions were tested using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to determine the correlation between the different quantitative parameters. p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. ANOVA test was applied after dividing patients into three groups based on LUS B scores. A binary logistic regression was conducted to identify the factors associated with a higher number of B-lines in patients undergoing dialysis. A backward stepwise likelihood ratio method was applied to evaluate the predictive value of demographic and clinical variables.

Ethical compliance

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional ethics committee of Bhaikaka university with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Result

Table 1 unveils the baseline demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of all the participants(n = 93). The mean age was 48.20 ± 13.81 years with male predominance (n = 66, 71.0%). The most common BMI range is overweight and obese category i.e. 23 and above (41 subjects, 44.1%). Tobacco Chewing was the most prevalent addiction type (27 subjects, 29.0%). Most participants reported no addiction (n = 56, 60.2%). We found hypertension (n = 30, 32.3%) and Diabetes (n = 26, 28.0%) as most common etiology of chronic kidney disease in our cohort. A significant portion of subjects falls under chronic kidney disease of undetermined etiology (n = 20, 21.5%) and the rest are classified as “others” (n = 17, 18.3%) which includes polycystic kidney disease, hereditary nephritis, obstructive uropathy, chronic glomerulonephritis, lupus nephritis and chronic allograft nephropathy. The prevalence rates of various comorbidities in our cohort were as follows: Diabetes Mellitus (DM) in 28 subjects (30.10%), hypertension (HTN) in 78 subjects (83.9%), and ischemic heart disease (IHD) in seven subjects (7.5%). Presence of hypertension was universal phenomenon. Nearly 84% of the participants had hypertension. A large number of patients (n = 68,73.1%) were on hemodialysis thrice a week. Similarly, 86% of the patients had AVF as vascular access and 80% had adequate dialysis clearance (Table 1). Only 28 patients (30%) had NYHA class III dyspnea, while 50 patients (54%) had NYHA class II dyspnea. Other clinical parameters of excess volume, such as edema and lung crackles, were observed in five (5.4%) and eight patients (8.6%), respectively. The Mean Lung USG B lines pre-HD and post HD were 3.527 ± 4.636 and 0.484 ± 1.419, respectively. The mean Lung USG B lines pre-HD were 4.64 ± 4.38 for the twice weekly group and 3.12 ± 4.68 for the thrice weekly group. However, this difference was not statistically significant (p value = 0.07) (Table 2).

Of the 28 patients with NYHA class III dyspnea, 14 had no B line, 13 had B lines 1–14 and only 1 had B lines > 14. In contrast, out of the 50 patients with NYHA class II dyspnoea,22 patients had an O B line,26 patients had B lines 1–14 and 2 had B lines > 14. (p = 0.41). All five patients with edema had B lines 1–14 while 44 out of 88 patients without edema had B lines 1–14. The mean Lung USG B lines were 3.40 ± 4.69 for individuals without oedema and 5.80 ± 2.77 for those with oedema (p-0.05). Among the eight patients with lung crepitations,3 patients had 0 B lines and five had B lines 1–14. Similarly,44 patients out of 85 patients with no adventitious respiratory sounds had B lines 1–14 and 3 patients had B lines > 14. The Mean Lung USG B lines pre -HD were 3.25 ± 3.53 and 3.55 ± 4.74, respectively, in these two groups. (p value of 0.89), respectively. We did not find a statistically significant difference in pre-HD lung B lines between patients with dialysis vintage of less than or more than 1 year. In addition, there was no difference when we compared patients with kt/v urea less than or greater than 1.2. Mean Lung USG B lines were 3.58 ± 4.80 and 3.0 ± 2.26 for patients with IVC collapsibility index less than 50% and more than 50% respectively although it was not significant (p-0.70) (Table 2). The correlation analysis between ultrafiltration (litres) and Lung USG B lines in the study cohort suggests a weak positive correlation (correlation coefficient r = 0.08). The correlation analysis between the IVC maximum diameter pre-HD and Lung USG B lines pre- HD (r-0.45) indicates a moderate positive correlation (Table 3).

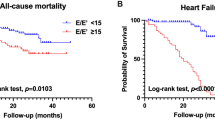

The correlation between early LV filling velocity (E) and pre-HD Lung USG B line was positive (r-0.21).LV filling pressure E/E’ also correlated positively with Lung B lines (r-0.35). Moreover, there was a moderately positive correlation between pulmonary pressure and B-lines (r-0.33). see Fig. 2. (a), (b), (c), (d). We did not find a significant correlation between left atrial volume, left ventricle end-diastolic volume, ejection fraction, and pre -HD lung B lines.

When 3 groups of patients (based on LUS B lines) were compared after applying ANOVA and post hoc analysis, we found statistically significant p value for Pre-HD IVC diameter, E/E’ and pulmonary pressure (Table 4). Binary logistic regression analysis with backward LR method to predict odds of B lines category (< = 7, > 7) taking Age, Gender, BMI, Dialysis vintage, IVC diameter PreHD, E/E’ Pre-HD, PP PreHD, and Urea Pre-HD as predictors suggested significant association of IVC diameter and pulmonary pressure (before dialysis) with LUS B-lines (Table 5).

Discussion

It has been proven that ultrasound of the lung can improve the diagnosis of volume excess by detecting extravascular lung water (EVLW)10. But how useful this information is if the patient is asymptomatic? Our study sought to compare the physical findings of EVLW, 28 site LUS and echocardiographic parameters of cardiac performance before dialysis. The development of alveolar edema depends on two factors.1. left ventricular function, 2. lung permeability. Hypertension, arterial stiffness, excess volume, and increased preload are the major drivers of adverse ventricular remodelling and induce systolic and diastolic dysfunction in patients with end-stage renal disease. This leads to high LV end-diastolic pressure and left atrial pressure. This, in turn, results in retrograde transmission of high pressure into the pulmonary circulation, which leads to the shifting of fluid into the interstitium and alveoli, resulting in alveolar edema. This manifests as dyspnea clinical symptoms, which, if severe, may steer to hospitalization. The second factor, lung permeability, may be associated with lung congestion, even in the absence of excess fluid due to systemic inflammation and uremia in patients with kidney diseases11.

Detecting and monitoring EVLW in these patients is a challenging and difficult task. As mentioned earlier, clinical examinations are less sensitive and specific for early detection. Over the last few years, there has been growing interest in utilizing the LUS for detecting pulmonary congestion. The rationale behind its use is that water accumulation in the lung interstitium thickens the interlobular septa. This thickening produces a reverberation of the ultrasound beam and produces bundles that spread from the probe to the edge of the screen, often referred to as ring-down artifacts. (Fig. 3) These bundles are the true ultrasound equivalent of B-lines found in chest X-rays, and their simple count provides an estimate of pulmonary congestion. The number of B lines is strongly associated with various echocardiographic parameters, including left atrial volume, LV end diastolic volume, pulmonary artery pressure, E/E’ ratio, and ejection fraction. This association continues to be true pre- and post-hemodialysis. This implies that these associations are largely independent of excess fluid at single point in time. It is actually chronic volume excess which causes structural changes to myocardium over period of time. Moreover, increased B-lines are associated with increased mortality and cardiovascular complications, independent of other risk factors11.

In a study conducted by Mohammad Walaa H et al., the mean B line score was 10.32 ± 6.22 in hemodialysis patients which is much higher than our mean B line of 3.527 ± 4.636. However, in that study, the mean interdialytic weight gain was 3.57 ± 0.75 kg which is significantly higher than that in our group (2.41 ± 1.21)12. A recently published randomized controlled LUST trial failed to prove the usefulness of crackles and peripheral edema in detecting pulmonary congestion that was found by LUS13. We also did not find a significant correlation between B-lines and crackles, although we found a borderline significant correlation between edema and B-lines. Aileen Kharat et al. reviewed 28 articles and found a relatively high correlation between dyspnea NYHA grade and lung ultrasound (correlation coefficient of.57), mainly because of one prospective Egyptian study12,14. We did not achieve a significant correlation between dyspnea grade and LUS-B lines. Saleh Kaysi et al. examined IVC dynamics in 18 hemodialysis patients but could not prove its correlation with LUS-B lines15. However, we found a significant correlation between the pre-HD maximum IVC diameter and LUS-B score. In a study by Saad et al., multiple regression analysis suggested a significant association between the B-line score and diastolic function E/E’ (OR = 0.893, 95% CI), but not with LVEF (OR 1.009, 95% CI)16. We also found a strong correlation between LUS-B score and early LV filling velocity-E, LV filling pressure -E/E’, and pulmonary pressure, but not with EF, LA volume, and LV EDV. These observations demonstrate that LV function and pulmonary congestion are interlinked. Larger intervention randomized trials such as LUST did not show differences in all-cause mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or decompensated HF despite lung ultrasound-guided treatment in the active group of high-risk HD patients compared to the control group13. However, there were reduction in LV filling pressures (E/E’, p = 0.03), and LA volume (p = 0.05) in the active group at 8 weeks. It should be noted that participants in the LUST trial had a high CV risk profile. In our cohort, the incidence of ischemic heart disease was only 7.5%. However, not all patients underwent mandatory cardiac evaluation. These results indicate that lung USG may detect congestion very early, even before the appearance of symptoms. However, patients on three times a week hemodialysis may have fewer B lines, as seen in our study. Treatment based on the Lung B score in asymptomatic hemodialysis patients would lead to any meaningful outcome or not is not clear, as per the current available evidence. However, it is certain that lung ultrasound-based treatment strategies can reduce lung congestion, improve cardiac chamber dimensions and LV diastolic function. These may have favourable effects on hard points in the long run.

Limitation

The lung ultrasound technique has some inherent limitations. It is difficult to differentiate dry B lines (fibrotic thickening) from wet B lines (excess lung water).

We did not test the interobserver agreement which is a crucial measure of data quality as well as reliability and also important to nullify observer bias. We also did not check intraprobe reproducibility in our study. 28 site scanning approach is time-consuming and labour-intensive; hence, it is impractical to perform in routine clinical settings, and we did not take BIA (bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) to estimate the hydration status; rather, we used IVC indices. The former may provide a more objective and precise estimate of the overhydration as compared to later. Hypoalbuminemia and malnutrition may lead to excess lung water. We did not have data of serum albumin or the nutritional status of all participants. We also did not consider the residual kidney function of all participants, which is an important factor when studying volume excess in dialysis patients. This was a single-center study. A multicenter randomized controlled trial with a large sample size would be more appropriate for addressing all unanswered questions.

Conclusion

Lung ultrasound is a safe and promising bedside technique. There was a borderline strong correlation between the clinical parameters of edema and the lung USG B score. However, other clinical parameters like grade of dyspnoea and lung crackles were not correlated with B line score. IVC maximum diameter pre-HD and Echocardiography parameters such as early LV filling velocity E, LV diastolic function indicated by E/E’, and pulmonary pressure moderately correlated with pre-HD lung USG-B lines. Lung ultrasound may be a useful adjunctive tool in evaluating volume status in HD patients, warranting further study in multicentre trials.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available because individual privacy could be compromised. However, they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Jager, K. J. et al. A single number for advocacy and communication-worldwide more than 850 million individuals have kidney diseases. Kidney Int. 96 (5), 1048–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2019.07.012 (2019).

Rhee, C. M., Kovesdy, C. P. & Epidemiology Spotlight on CKD deaths—increasing mortality worldwide. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 11 (4), 199–200. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2015.25 (2015).

Onofriescu, M. et al. Overhydration, cardiac function and survival in Hemodialysis patients. PLoS One. 10 (8), e0135691. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135691 (2015).

Torino, C. et al. The agreement between auscultation and lung ultrasound in Hemodialysis patients: the LUST study. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 11 (11), 2005–2011. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.03890416 (2016).

Damy, T. et al. Does the physical examination still have a role in patients with suspected heart failure? Eur. J. Heart Fail. 13 (12), 1340–1348. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfr128 (2011).

Loutradis, C., Sarafidis, P. A., Ferro, C. J. & Zoccali, C. Volume overload in hemodialysis: diagnosis, cardiovascular consequences, and management. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 36 (12), 2182–2193. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfaa182 (2021).

Davies, S. J. & Davenport, A. The role of bioimpedance and biomarkers in helping to aid clinical decision-making of volume assessments in Dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 86 (3), 489–496. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2014.207 (2014).

Hassanzadeh Rad, A. & Badeli, H. Point-of-Care ultrasonography: is it time nephrologists were equipped with the 21th century’s stethoscope? Iran. J. Kidney Dis. 11 (4), 259–262 (2017).

Loutradis, C. et al. Lung Ultrasound-Guided dry weight assessment and echocardiographic measures in hypertensive Hemodialysis patients: A randomized controlled study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 75 (1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.07.025 (2020).

Rajpal, M., Talwar, V., Krishna, B. & Mustafi, S. M. Assessment of extravascular lung water using lung ultrasound in critically ill patients admitted to intensive care unit. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 28 (2), 165–169. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10071-24635 (2024).

Zoccali, C. Lung ultrasound in the management of fluid volume in Dialysis patients: potential usefulness. Semin Dial. 30 (1), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/sdi.12559 (2017).

Mohammad, W. H., Elden, A. B. & Abdelghany, M. F. Chest ultrasound as a new tool for assessment of volume status in Hemodialysis patients. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 31 (4), 805–813. https://doi.org/10.4103/1319-2442.292314 (2020).

Zoccali, C. et al. A randomized multicenter trial on a lung ultrasound-guided treatment strategy in patients on chronic Hemodialysis with high cardiovascular risk. Kidney Int. 100 (6), 1325–1333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2021.07.024 (2021).

Kharat, A. et al. Volume status assessment by lung ultrasound in End-Stage kidney disease: A systematic review. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 10, 20543581231217853. https://doi.org/10.1177/20543581231217853 (2023).

Kaysi, S., Pacha, B., Mesquita, M., Collart, F. & Nortier, J. Pulmonary congestion and systemic congestion in hemodialysis: dynamics and correlations. Front. Nephrol. 4, 1336863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneph.2024.1336863 (2024).

Saad, M. M. et al. Relevance of B-Lines on lung ultrasound in volume overload and pulmonary congestion: clinical correlations and outcomes in patients on Hemodialysis. Cardiorenal Med. 8 (2), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1159/000476000 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We will like to extend our gratitude to Mr. Naresh Fumakiya -senior echocardiography technician for performing echocardiography of all participants and dialysis nurses for helping us to carry out study in dialysis unit.

Funding

The study was self-funded by principal investigators, Dr. Maulin Shah and Dr. Reema Patel. Ultrasound machines of the university hospital were used.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

1, Dr. Maulin K Shah-study concept, design, data analysis, manuscript writing, critical revision of manuscript2. Dr. Reema D Patel-acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data3.Dr. Rachit J Patel-acquisition of data, drafting and critical revision of manuscript4.Dr. Jyoti G Mannari- study concept, critical revision of manuscript5.Dr. Mitesh Makwana- critical revision of manuscript6.Dr. Vivek Kute- critical revision of manuscript7.Jaishree Ganjiwale-critical revision in statistics analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, M.K., Patel, R.D., Patel, R.J. et al. Correlation between lung ultrasound B lines and clinical as well as echocardiographic parameters in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Sci Rep 16, 3284 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32769-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32769-2