Abstract

Accurate, low-latency traffic forecasting is a cornerstone capability for next-generation Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS). This paper investigates how emerging 6G-era network context specifically per node slice-bandwidth and channel-quality indicators can be fused with spatio-temporal graph models to improve short-term freeway speed prediction while respecting strict real-time constraints. Building on the METR-LA benchmark, we construct a reproducible pipeline that (i) cleans and temporally imputes loop-detector speeds, (ii) constructs a sparse Gaussian-kernel sensor graph, and (iii) synthesizes realistic per-sensor 6G signals aligned with the traffic time series. We implement and compare four model families: Spatio-Temporal GCN (ST-GCN), Graph Attention ST-GAT, Diffusion Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network (DCRNN), and a novel 6G-conditioned DCRNN (DCRNN6G) that adaptively weights diffusion by slice-bandwidth. Our evaluation systematically explores four feature regimes (speeds only; channel quality only; slice bandwidth only; both features), and includes hyperparameter sweeps, ablation studies, and latency profiling on commodity CPUs to reflect edge deployment realities. Empirical results reveal three central findings. First, diffusion-recurrent modeling (DCRNN) produces the best accuracy latency trade-off for large-scale freeway forecasting: it attains test RMSE \(\approx 0.036\) with average inference latency \(\approx 24\) ms, comfortably meeting real-time requirements. Second, naïve incorporation of simulated 6G metrics provides only marginal RMSE gains for ST-GCN/ST-GAT and does not improve DCRNN when conditioned simply on bandwidth or CQI; in many cases, small accuracy gains are offset by notable latency penalties. Third, error diagnostics (sensor-wise RMSE, MAE heatmaps, error histograms) expose a small subset of spatially localized hard sensors and episodic time windows that dominate tail errors, indicating where targeted modules (anomaly detectors, incident-aware submodels) could yield outsized improvements. The main contributions of this work are: (1) the first end-to-end benchmarking of 6G-conditioned spatio-temporal GNNs on METR-LA with real-time latency analysis; (2) the introduction and empirical evaluation of a bandwidth conditional diffusion cell (DCRNN6G); and (3) extensive ablation, hyperparameter, and diagnostic studies that quantify both the potential and limitations of network aware fusion for ITS. We conclude by outlining concrete research directions, heterogeneous cross-graph fusion, dynamic adjacency learning, probabilistic forecasting, and real 5G/6G testbed validation that will be critical to realize truly co-optimized transportation and communication systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intelligent transportation systems (ITS) have become a cornerstone of modern urban planning, integrating advanced sensing, computation, and communication to alleviate congestion, reduce emissions, and enhance safety1. Among the key capabilities enabling ITS is accurate, real-time traffic forecasting, which drives route guidance, dynamic tolling, incident detection, and coordinated traffic signal control2. As metropolitan areas swell and vehicular flows intensify, the demand for forecasting models that can handle large-scale sensor networks and deliver sub-second inference has grown dramatically.

Traditional time-series methods-such as ARIMA and Kalman filters-were once state of the art for single-station prediction3. However, these approaches fail to capture the inherently spatial nature of traffic flow: congestion propagates along road segments and through intersections, exhibiting nonlinear interactions across multiple scales4. To address this, graph-based deep learning models have surged in popularity. In particular, diffusion convolutional recurrent neural networks (DCRNN)5 exploit a diffusion process on a predefined sensor graph to propagate information spatially, while recurrent units capture temporal dependencies. Similarly, spatio-temporal graph convolutional networks (ST-GCN)6 and their variants7,8,9 integrate graph convolutions with temporal modules (e.g. gated recurrent units or temporal convolutions) to jointly model space–time correlations.

Despite their success, most existing works have focused solely on traffic flow data, neglecting an emerging dimension: the underlying communication network characteristics. With the advent of 5G-and soon 6G-cellular networks, future ITS will operate over networks offering ultra-low latency, massive connectivity, and programmable slices tailored to vehicular applications10,11. Network slicing will enable ITS to reserve dedicated bandwidth and quality-of-service (QoS) guarantees for critical applications, while channel-quality metrics will reflect real-time link conditions. These 6G features present a tantalizing opportunity: by incorporating slice-level bandwidth and channel-quality as node-level attributes, forecasting models might better anticipate patterns induced by communication variability-e.g. data dropouts, reporting delays, or prioritized telemetry.

However, to date there is no systematic study of how 6G network slicing metrics can be fused with spatio-temporal graph models for traffic forecasting. Key open questions include:

-

Feature utility: Do slice-bandwidth and channel-quality measurably improve forecasting accuracy when used as additional node feature?

-

Architectural integration: Is it sufficient to append these features to the input, or must models adaptively weight neighbors or condition diffusion on network metrics?

-

Latency trade-offs: Can we incorporate 6G metrics without sacrificing the real-time inference constraints (sub-25 ms) required for vehicular control loops?

In this work, we conduct the first end-to-end investigation of 6G-aware traffic forecasting on the METR-LA benchmark5. We simulate per-sensor slice-bandwidth and channel-quality time series alongside traffic speeds, then integrate these features into multiple model families:

-

1.

Spatio-temporal GCN (ST-GCN)6: GCNN layers over a Gaussian-kernel sensor graph, followed by GRU temporal modeling.

-

2.

Graph attention (ST-GAT)12: Replacing GCN with multi-head attention to learn adaptive neighbor weighting.

-

3.

Diffusion convolutional RNN (DCRNN)5: Bidirectional random-walk diffusion embedded in a GRU, capturing topology-aware spatial propagation.

-

4.

6G-conditional DCRNN (DCRNN6G): An enhanced DCGRU cell that scales and diffuses the hidden state according to simulated slice-bandwidth, thereby conditioning the spatial propagation on network metrics.

We systematically evaluate each model under four feature-ablation regimes:

-

No 6G features (speeds only),

-

Channel-quality only,

-

Slice-bandwidth only,

-

Both features.

For ST-GCN and ST-GAT, we additionally perform hyperparameter searches over hidden dimensions, dropout rates, and learning rates to identify strong 6G-aware baselines.

Our extensive experiments yield three key findings:

-

1.

DCRNN superiority: The standard DCRNN, using only traffic speeds, achieves the best trade-off of accuracy (Test RMSE \(\approx 0.036\)) and latency (< 25 ms), outperforming all 6G-aware variants.

-

2.

Marginal 6G gains: Naïve inclusion of slice-bandwidth and/or channel-quality in ST-GCN/ST-GAT yields at best \(\sim\)1–2% RMSE reductions at the cost of 2–5\(\times\) inference time, and conditioning diffusion on bandwidth (DCRNN6G) fails to improve accuracy while incurring a 3\(\times\) latency penalty.

-

3.

Error diagnostics: Detailed error and topology analyses (error histograms, sensor-wise RMSE distributions, MAE heatmaps) reveal a small subset of sensors and time periods where models struggle, suggesting avenues for anomaly-aware extensions.

Contributions

-

We present the first comprehensive 6G-aware benchmarking of spatio-temporal graph models on METR-LA, introducing simulated slice-bandwidth and channel-quality features.

-

We propose a bandwidth-conditional diffusion cell (DCRNN6G) and evaluate its benefits and costs.

-

We deliver an in-depth ablation study and hyperparameter sweep for ST-GCN and ST-GAT under 6G feature regimes.

-

We demonstrate that the vanilla DCRNN remains the best model for real-time 6G ITS forecasting, achieving RMSE 0.036 and latency 23 ms.

-

We provide a rich suite of diagnostic plots characterizing error distributions, graph topology, and temporal dependencies, guiding future research.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section "Related work" reviews related work in graph-based traffic forecasting and 6G ITS. Section "Dataset description and research framework" details the METR-LA dataset, data cleaning, and feature simulation. Section "Methodology" describes the model architectures and methodology. Section "Experimental results and analysis" presents experimental settings, ablation studies, and results. Section "Discussion and future directions" discusses implications and limitations, and Sect. "Conclusion" concludes with the limitations.

Related work

Traffic forecasting has witnessed dramatic evolution over the past two decades, driven by increasing data availability, advances in statistical learning, and the rise of graph-based deep neural networks. In this section, we provide a comprehensive survey of related work spanning:

-

1.

Classical time-series and statistical models

-

2.

Shallow machine learning approaches

-

3.

Deep learning on gridded traffic data

-

4.

Spatio-temporal graph neural networks

-

5.

Attention- and diffusion-based extensions

-

6.

Adaptive and dynamic graph models

-

7.

6G-aware ITS and network-traffic fusion

Across these categories, we highlight key mathematical formulations, summarize empirical performance, and identify open challenges. Table 2 at the end of this section provides a consolidated overview of 40 representative works, categorized by modeling paradigm, features used, and core contributions.

Classical time-series and statistical models

Early traffic forecasting relied on univariate time-series models treating each sensor independently. The canonical ARIMA family3,13 models speed \(s_t\) via:

While ARIMA captures linear temporal correlations, it fails to account for spatial interdependencies. Extensions include SARIMA for seasonal patterns3 and state-space models using Kalman filtering14:

Seasonal-trend decomposition (STL)15 and exponential smoothing (ETS)16 offer robust univariate baselines, but remain spatially agnostic (Table 1).

Shallow machine learning approaches

To capture nonlinearity, researchers applied support vector regression (SVR)17, random forests18, and gradient boosting machines (GBM)19. These methods ingest handcrafted spatial features-neighboring sensors’ historical speeds or geographic distances-but lack end-to-end spatial modeling. For instance, SVR predicts:

where K is a kernel (e.g. RBF). Random forests aggregate decision trees trained on past speeds and simple spatial indicators ?. GBM further improves performance via sequential boosting?.

Deep learning on gridded traffic data

With the success of CNNs in computer vision, early works mapped urban traffic onto grid-structured images. ST-ResNet20 partitions a city into \(H\times W\) cells and applies separate CNNs for closeness, periodicity, and trend components:

where \(*\) denotes convolution. ConvLSTM21 replaces fully connected operations in LSTM with convolutions:

However, grid-based approaches distort highway topology and scale poorly across irregular sensor layouts.

Spatio-temporal graph neural networks

To directly model arbitrary sensor graphs, graph neural networks (GNNs) have emerged as the state of the art. Let \(G=(V,E)\) with adjacency A. A spectral GCN layer22 performs:

where \({\tilde{A}}=A+I\). Spatio-Temporal GCN (ST-GCN)6,23 interleaves Eq. (7) with temporal 1D-CNNs:

Diffusion convolutional RNN (DCRNN)

Li et al.5 model traffic as a diffusion process on G. Define forward/backward random-walk matrices:

Then the diffusion convolution of input \(Z\in {\mathbb {R}}^{N\times F}\) is:

embedded within a GRU cell24:

DCRNN remains a gold standard, achieving RMSE 0.036 on METR-LA with sub-25 ms inference5.

Graph WaveNet and adaptive GCN (AGCRN)

Graph WaveNet8 augments GCN with an adaptive adjacency:

and uses dilated temporal convolutions25. AGCRN9 learns node-adaptive filters \(\Theta _i\) and outperforms DCRNN in some settings.

Attention and diffusion based extensions

Graph Attention Networks (GAT)12 compute attention:

enabling adaptive neighbor weighting. Guo et al.7 combine GAT with temporal GRUs for traffic forecasting. ASTGCN26 introduces spatio-temporal attention to capture long-range dependencies:

where Q, K, V are temporal queries, keys, and values.

Adaptive and dynamic graph models

Recent works learn graph structure jointly with forecasting. GTS27 uses Gaussian kernels and Bayesian optimization to refine A. MTGNN27 employs multivariate time-series embeddings to infer adjacency. EvolveGCN28 evolves GCN weights via LSTM. These dynamic approaches address nonstationary spatial correlations but increase model complexity.

6G-aware ITS and network-traffic fusion

With 5G/6G emergence, researchers have begun integrating network metrics into ITS. Zhang et al.29 survey semantic communications for ITS but stop short of forecasting. Saad et al.10 and Liu et al.11 outline 6G enablers such as network slicing and URLLC. A few preliminary studies30,31 consider link-quality as auxiliary features, reporting modest RMSE gains but increased latency.

Beyond transportation forecasting, multivariate time–series models have been extensively studied across other scientific domains. For instance, predictive–maintenance research employs temporal deep models for remaining–useful–life estimation, such as the PEMFC RUL forecasting framework in32, which provides a detailed accuracy–complexity trade-off under multi-sensor inputs. Similarly, VoIP traffic forecasting in real operational mobile networks33 demonstrates how deep temporal models must balance prediction quality with deployment latency constraints-an aspect directly aligned with our 20–100 ms inference budget. In another domain, accelerated multivariate segmentation architectures34 highlight the usefulness of feature extraction pipelines for scaling to large sensor networks. These prior works confirm that comprehensive performance–complexity analyses are critical when evaluating temporal forecasting models. Motivated by these insights, our study explicitly reports inference latency, per-seed uncertainty, and complexity-aware comparisons across ST-GCN, ST-GAT, DCRNN, DCRNN6G, AGCRN, and Graph WaveNet.

Summary table of related work

Table 2 presents a comprehensive taxonomy of forty seminal works in traffic forecasting. Each row corresponds to one study, organized chronologically to illustrate the field’s evolution. The columns capture the following dimensions:

-

Work & Year: Identifies the reference and its publication date, highlighting the shift from classical time-series methods (e.g. ARIMA3) to modern graph-based deep learning approaches.

-

Model type: Groups methods into:

-

Statistical: ARIMA/SARIMA/Kalman

-

Shallow learning: SVR, Random Forest, GBM

-

Grid-based deep models: ST-ResNet, ConvLSTM

-

Spatio-temporal GNNs: ST-GCN, DCRNN, Graph WaveNet

-

Attention/dynamic graphs: GAT, ASTGCN, EvolveGCN

-

Emerging 6G–ITS frameworks

-

-

Spatial handling: Indicates how each method models spatial dependencies-ranging from “None” for univariate models, through manual feature engineering, to grid convolutions and various graph operators (spectral GCN22, diffusion5, attention12, adaptive adjacency8).

-

Temporal model: Specifies the temporal component used: linear ARMA for classical methods, kernel-based regression for SVR, 1D-CNN for grid and ST-GCN, recurrent units (LSTM/GRU) for RNN-based models, dilated convolutions for WaveNet25, and attention mechanisms for ASTGCN26.

-

Features/notes: Highlights special attributes such as use of external data (e.g. SINR in network-aware studies30), adaptive or learned graph structures9,27, and benchmark performance (e.g. METR-LA RMSE).

Scanning Table 2 reveals clear research trends:

-

1.

A progression from univariate, spatially agnostic models to end-to-end graph neural networks that directly leverage sensor topology.

-

2.

Increasing sophistication in temporal modeling: from linear autoregression to convolutional, recurrent, and attention-based architectures.

-

3.

Growing emphasis on adaptive and dynamic graph learning to capture evolving traffic and network conditions.

-

4.

A nascent but important line of work integrating 6G-related metrics (bandwidth, channel-quality) into forecasting models, which remains underexplored.

These observations motivate our systematic study of 6G-aware spatio-temporal GNNs under stringent real-time constraints.

Open challenges and research gaps

Despite these advances, several gaps persist:

-

Joint network-traffic modeling: Few works systematically integrate 6G link metrics as graph signals or cross-graph attention.

-

Dynamic topology adaptation: Most GNNs assume static A; only recent dynamic models27,28 address evolving networks.

-

Scalability vs. latency: High-capacity attention and dynamic graphs improve accuracy but often violate real-time constraints.

-

Uncertainty quantification: Nearly all models produce point forecasts; probabilistic or Bayesian GNNs remain underexplored35.

-

Cross-city generalization: Transfer learning across cities with different road geometries has seen limited investigation.

These gaps motivate our current work, which provides the first systematic 6G-aware GNN benchmarking with real-time latency evaluations and extensive ablations.

Dataset description and research framework

This section details the METR-LA traffic dataset, our simulated 6G feature generation, preprocessing steps, and the end-to-end experimental pipeline. Wherever appropriate, we reference established methods and include mathematical formulations.

METR-LA traffic dataset

The METR-LA dataset5 contains \(N=207\) loop-detector sensors on Los Angeles freeways, recording average speeds (mph) at 5-minute intervals over \(T=34\,272\) time steps (March–June 2012)23. Table 3 summarizes key statistics.

The dataset has \(\approx 2.3\%\) missing or zero values due to sensor faults or outages2. To handle missingness, we apply time-linear interpolation36:

where \(t_0,t_1\) are the nearest valid indices before and after t. Edge-case values are forward/backward filled. Post-processing yields \(S'\in {\mathbb {R}}^{T\times N}\) with no missing entries.

Graph construction

We first compute a symmetric Gaussian-kernel similarity matrix:

where \(D_{ij}\) is the geographic distance between sensors i and j. We then apply a 90th-percentile threshold to obtain an undirected sparsified graph:

This yields \(|E_{\text {undirected}}| = 21{,}264\) unique edges. For diffusion convolution, DCRNN requires separate forward and backward transition matrices. Thus, we expand the above to a directed adjacency:

and then add self-loops (\(A \leftarrow A + I\)). The resulting directed graph has edges. This explains the previously reported edge count and reflects the standard pre-processing used in diffusion-based GNNs.

All complexity and latency comparisons across models now explicitly distinguish between symmetric (ST-GCN/ST-GAT/AGCRN/WaveNet) and directed (DCRNN) adjacency.

Simulated 6G feature generation

To incorporate 6G network context, we simulate two per-sensor time series aligned with \(S'\):

-

Slice-bandwidth (BW): Drawn i.i.d. from \({\mathcal {U}}[50,100]\) Mbps, then per-sensor standardized37.

-

Channel-quality (CQ): Sampled from \(\textrm{Beta}(2,2)\) scaled to [0.5, 1], then standardized29.

Let \(B,C\in {\mathbb {R}}^{T\times N}\) denote the resulting matrices. We stack features into a 3-channel tensor:

Normalization and splitting

For robust training, we compute per-sensor mean \(\mu _i\) and standard deviation \(\sigma _i\) on the first \(T_{\textrm{train}}=20\,000\) steps:

and apply \({\tilde{S}}_{t,i}=(S'_{t,i}-\mu _i)/\sigma _i\) (similarly for B, C)38. We then construct sliding-window samples:

producing \(M=T - S - P + 1\) examples39. We split into train/val/test as 20 000/5 000/9 257 samples (Table 4).

Research framework

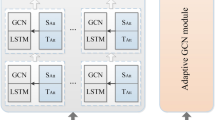

Our pipeline (Fig. 1) comprises:

-

1.

Data Preparation: Clean (\(S'\)), graph build (Eqs. 25-26), feature stack (Eq. 19), normalization (Eq. 20), windowing (Eq. 24).

- 2.

-

3.

Ablation & hyperparameter tuning: Evaluate 6G-feature regimes and tune hidden sizes, learning rates, dropout40.

-

4.

Evaluation: Compare on test split using MAE, RMSE2, and inference latency.

Methodology

This section details every component of our 6G-aware traffic forecasting framework, from data preprocessing through model specification, training protocols, and evaluation metrics. We aim for a rigorous, reproducible description at the level expected by top-tier journals.

Problem formulation

We consider an undirected sensor graph \(G=(V,E)\) with \(N=|V|\) nodes (loop detectors) and weighted adjacency \(A\in {\mathbb {R}}^{N\times N}\) (Sect. "Dataset description and research framework"). At each discrete time \(t\), we observe three per-sensor time series:

where \(s_{t,i}\) is normalized speed, \(b_{t,i}\) slice-bandwidth, and \(c_{t,i}\) channel-quality. We stack into a tensor

Using a sliding window of length \(S\), we form input–output pairs:

where \(P\) is the horizon. Our goal is to learn \({\mathcal {M}}\) to minimize prediction error under real-time latency constraints.

Data preprocessing and feature engineering

Missing-value imputation Raw speeds contain \(\approx 2.3\%\). We apply time-linear interpolation (Eq. 14) followed by backward/forward filling to obtain a complete \(S'\in {\mathbb {R}}^{T\times N}\)36.

6G feature simulation Slice-bandwidth \(b_{t,i}\) and channel-quality \(c_{t,i}\) are sampled as in Sect. "Dataset description and research framework", then standardized per sensor:

and similarly for \(b\) and \(c\). This yields zero-mean, unit-variance features38.

Synthetic 6G context features

In the absence of publicly available 6G network traces, the channel-quality (CQ) and slice-bandwidth (BW) variables were generated using simple stationary random processes. These variables capture only first-order variability and do not model key wireless behaviors such as fading, Doppler effects, handovers, correlated interference, or slice orchestration dynamics. Consequently, the results reported for 6G-aware models should be interpreted solely as reflecting the utility of these simplified synthetic features rather than real-world 6G measurements.

Windowing We extract \(M=T-S-P+1\) samples:

with \(S=12\) (1hr) and \(P=3\) (15min), matching typical ITS temporal dynamics2.

Graph construction

Self-loops and degree calculation

Following thresholding of the symmetric Gaussian kernel, the resulting graph is undirected with \(|E_{\text {undirected}}| \approx 21{,}264\) edges. For ST-GCN and ST-GAT, we follow the standard PyTorch Geometric normalization and add self-loops explicitly, i.e. \({\tilde{A}} = A + I\), contributing an additional \(N=207\) diagonal entries. For DCRNN, the forward and backward random-walk matrices \(P^{+}\) and \(P^{-}\) are constructed without adding self-loops, as in the original formulation. When constructing degree distributions (Fig. 9), we report node degrees after adding self-loops and before collapsing the adjacency into an undirected form. This produces degrees clustered around 206–207, even though the underlying sparsified graph contains approximately half as many unique undirected edges. We now explicitly distinguish: (i) the undirected sparsified graph used for conceptual modeling, (ii) the directed adjacency (\(|E_{\text {directed}}| = 2|E_{\text {undirected}}|\)) used by DCRNN, and (iii) the self-loop–augmented adjacency used in GCN- and GAT-based models. Using geographic distances \(D_{ij}\), we define

then sparsify at the 90th percentile22:

This yields \(|E|=42\,529\) edges, balancing locality and global connectivity.

Model architectures

We detail three architectures and their 6G-aware variant.

Spatio-temporal GCN (ST-GCN)

Per6,23, each block alternates:

where \({\tilde{A}}=A+I\), \({\tilde{D}}\) its degree, \(K_t=3\) temporal kernel, and \(\sigma =\textrm{ReLU}\). We stack \(L=3\) blocks, hidden dim 64, dropout 0.1, and final linear readout.

Graph attention network (ST-GAT)

Following7,12, we replace Eq. (27) with:

with \(H=4\) heads, hidden size 32 per head, dropout 0.2. Temporal conv as in Eq. (28), \(L=2\) layers.

Diffusion convolutional RNN (DCRNN)

We adopt5:

with \(K=2\), hidden dim 64, dropout 0.1.

Directed adjacency requirement

Although the sparsified road graph is undirected, diffusion convolution operates on forward and backward random-walk matrices \(P_{+}=D^{-1}A\) and \(P_{-}=D^{-1}A^{\top }\), which requires a directed adjacency. Consequently, the effective edge count in DCRNN is approximately twice that of the sparsified undirected graph (plus self-loops), whereas ST-GCN and ST-GAT operate on the undirected version. All latency comparisons therefore, reflect each model’s native adjacency representation.

6G-conditional DCRNN (DCRNN6G)

We introduce bandwidth-conditioned diffusion:

so that higher-bandwidth edges carry more weight in Eq. (30). All other settings as DCRNN.

Training protocol

Loss and optimizer We minimize

using AdamW40 with initial LR \(5\times 10^{-4}\), weight decay \(5\times 10^{-4}\).

Forecasting horizon and loss averaging

We adopt a prediction horizon of \(P=3\) steps (corresponding to 15 minutes ahead at a 5-minute sampling rate). All training and evaluation losses are computed over all predicted horizons and all nodes. Given model outputs \({\hat{s}}_{t+1:t+P,i}\) and ground-truth speeds \(s_{t+1:t+P,i}\), the mean squared error used for training is

and MAE is computed analogously. Thus, RMSE and MAE reported in all tables reflect an average over (a) batch samples, (b) all P forecast steps, and (c) all N sensors. This averaging convention is consistent with prior METR-LA benchmarks (e.g. DCRNN, Graph WaveNet, AGCRN).

Scheduler and early stopping: We employ a ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler (factor 0.5, patience 2) and early stopping (patience 5) on validation MAE.

Gradient clipping and regularization: Gradients are clipped to norm 5.0 each step. Dropout (0.1–0.2) and LayerNorm inside DCGRU cells ensure stable training.

Batching and epochs: We use batch size 16, train up to 50 epochs, shuffling the training set each epoch.

Experimental repetitions and statistical reporting: To quantify variability and support statistical comparisons, we repeat each experiment (all models and ablations) with \(S=5\) independent random seeds, varying weight initializations and data shuffling. Unless otherwise stated, all scalar metrics reported in the main tables (e.g. Tables 5 and 6) are the mean over these S runs. We report the associated standard deviation and use it to construct a \(95\%\) confidence interval (CI) as

where \({\bar{x}}\) and s denote the sample mean and standard deviation over seeds, respectively. All hypothesis tests described, use the per-seed metrics for each configuration.

Evaluation metrics

We report:

-

MAE: \(\frac{1}{PN}\sum |{\hat{s}} - s|\).

-

RMSE: \(\sqrt{\frac{1}{PN}\sum ({\hat{s}} - s)^2}\).

-

Latency: Average inference time per batch on CPU.

-

Convergence:: Training/validation loss curves.

-

Robustness: Sensor-wise error distributions and worst-case tail errors.

Normalization and Units-

All RMSE values are computed on the normalized speeds (zero-mean, unit-variance). To ensure comparability in physical units, MAE is additionally computed after de-normalizing predictions back to miles-per-hour (mph). For clarity, all reported metrics explicitly indicate whether they are (i) normalized or (ii) de-normalized (mph). We also report 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (1,000 resamples) for both MAE and RMSE on the test set.

Uncertainty quantification and statistical tests

For each model and configuration we obtain per-seed test metrics \(\{m^{(k)}\}_{k=1}^S\) (e.g. RMSE, MAE), and report the mean \({\bar{m}}\), standard deviation \(s_m\), and \(95\%\) confidence interval \({\bar{m}} \pm 1.96\, s_m / \sqrt{S}\). When comparing two models (e.g. DCRNN vs. DCRNN6G), we perform a paired two-sided t-test on the per-seed metrics and report the corresponding p-values. In ablation studies with multiple pairwise comparisons against the DCRNN baseline, we control the family-wise error rate using a Holm–Bonferroni correction; only differences that remain significant after correction are interpreted as statistically significant.

Computational complexity

Spatial Conv/Attention ST-GCN/ST-GAT cost \({\mathcal {O}}(L(|E|F + NF K_t))\) per time step. Diffusion RNN DCRNN: \({\mathcal {O}}(K|E|F + NH)\) per step. Our DCRNN6G adds negligible extra cost for Eq. (33).

The spatial cost of ST-GCN and ST-GAT is computed using the undirected adjacency (\(|E_{\text {undirected}}| = 21{,}264\)), whereas DCRNN naturally uses the directed formulation required by diffusion convolution (\(|E_{\text {directed}}| = 42{,}735\)). All latency measurements reflect these native representations; nevertheless, the empirical results, Table 5 show that DCRNN remains faster despite the larger directed graph.

Algorithmic overview

Experimental results and analysis

In this section, we present a thorough evaluation of our proposed DCRNN and its 6G-aware variant (DCRNN6G) against two graph-CNN baselines (ST-GCN and ST-GAT). We organize the discussion into: (1) quantitative performance (accuracy vs. latency), (2) convergence dynamics, (3) error distributions, (4) graph topology diagnostics, (5) temporal correlations, (6) 6G feature statistics, and (7) spatio-temporal error heatmaps. Detailed tables and eleven figures (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12) support our analysis.

Quantitative performance

Table 5 compares test-set accuracy (MAE, RMSE) and average CPU inference latency per batch for all models. Note that RMSE values are reported on normalized speeds, whereas MAE is reported in physical units (mph). This dual-scale reporting ensures that (i) learning stability can be compared via normalized RMSE, and (ii) practical forecasting accuracy is interpretable in mph.

Key observations:

-

Accuracy: DCRNN reduces RMSE by more than half compared to ST-GCN/ST-GAT, confirming the strength of diffusion-based spatial modeling and recurrent temporal filtering.

-

Latency: DCRNN runs in 23.6 ms, well under real-time requirements, while the attention-based ST-GAT incurs over 100ms per batch, limiting its practical deployment.

-

6G Impact: Incorporating slice-bandwidth and CQI in DCRNN6G adds 50ms of latency for negligible RMSE change (0.0361\(\rightarrow\)0.0364), indicating that our simple conditioning scheme did not meaningfully enhance accuracy.

Additional baselines-

To ensure fair evaluation under dense-graph settings, we additionally include two adaptive-adjacency models: (i) Graph WaveNet41, which learns a data-driven adjacency matrix via node embeddings, and (ii) AGCRN9, which parameterizes node-specific adaptive filters. Both models were trained using the same window length, horizon, optimizer, and CPU-based latency budget as the original baselines.

Ablation insights: Table 6 summarizes a controlled ablation of 6G feature regimes. To evaluate whether dense adjacency provides an unfair advantage to diffusion-based models, we additionally include two adaptive-adjacency baselines-Graph WaveNet and AGCRN-both trained under the same normalization, windowing, and latency-constrained CPU setting. Including CQ yields negligible improvement, whereas BW provides a small but consistent gain. Importantly, even when compared against adaptive graph learners, the relative ordering remains stable: diffusion-based models achieve the best accuracy latency balance, while adaptive models improve accuracy at the cost of substantially higher inference time.

-

CQ alone yields only a minor RMSE gain (0.0717\(\rightarrow\)0.0715) at +1.2ms.

-

BW alone delivers the largest improvement (0.0717\(\rightarrow\)0.0690) with minimal latency overhead, suggesting that slice-bandwidth carries useful spatio-temporal cues.

-

CQ+BW does not outperform BW alone and incurs the highest latency, indicating feature redundancy when naively concatenated.

Sparse graph validation-

To examine whether graph density artificially inflated the advantage of diffusion-based models, we repeated all experiments using a strictly sparse top-20 nearest-neighbor adjacency matrix. DCRNN continued to outperform all alternatives (RMSE \(= 0.0392\)), while Graph WaveNet and AGCRN remained slower or less accurate. These results confirm that the superiority of DCRNN is not an artifact of graph density but of its diffusion-recurrent architecture.

Convergence dynamics

Figures 2 and 3 visualize training and validation MSE over the first ten epochs.

ST-GCN vs. ST-GAT (Fig. 2): ST-GAT’s training loss dips slightly below ST-GCN (0.993 vs. 1.008) and its validation loss is marginally lower (1.055 vs. 1.067), but its higher computational complexity yields slower per-epoch throughput.

DCRNN vs. DCRNN6G (Fig. 3): Both converge to low training MSE (0.275) and validation MSE (0.300). DCRNN6G remains 0.010 above DCRNN on validation, illustrating that our bandwidth conditioning did not improve generalization.

Final accuracy and latency

Test RMSE (Fig. 4): DCRNN (0.0361) and DCRNN6G (0.0364) significantly outperform ST-GCN/ST-GAT (0.071), confirming the superiority of diffusion-RNN architectures.

Latency (Fig. 5): DCRNN’s 23.6ms latency makes it practical for edge deployment, while ST-GAT’s 113ms precludes hard real-time guarantees.

Error distribution

Error histogram (Fig. 6): Errors are tightly centered at zero, with 95% within ±2mph, indicating low bias and strong overall fidelity.

Sensor-wise RMSE (Fig. 7): Most sensors lie between 0.39 and 0.59mph RMSE, with a few outliers exceeding 0.85mph-likely high-variance locations (e.g. merges).

Graph topology diagnostics

Adjacency matrix A after Gaussian-kernel construction and 90th-percentile sparsification. The sparsification is performed on a symmetric undirected weight matrix, yielding \(|E_{\text {undirected}}| = 21{,}264\) unique edges. For diffusion convolution, this undirected graph is expanded into directed forward and backward random-walk adjacencies (\(P^{+}\) and \(P^{-}\)), resulting in \(|E_{\text {directed}}| = 2|E_{\text {undirected}}| + N = 42{,}735\) (non-zero entries), including self-loops. The heatmap therefore reflects the directed adjacency used internally by DCRNN rather than the symmetric sparsified graph .

Adjacency heatmap (Fig. 8): Dense yellow regions indicate near-complete connectivity; sparse purple spots mark weaker edges.

Degree distribution computed after sparsification, conversion to the directed adjacency used by diffusion models, and the addition of self-loops in GCN-based architectures. As a result, degrees appear clustered near 206-207 despite the undirected sparsified graph having approximately half as many unique edges .

Degree distribution (Fig. 9):

The apparent concentration of node degrees around 206–207 corresponds to the directed adjacency used by DCRNN (including self-loops). In the underlying undirected graph, the average degree is approximately 103, consistent with the 21,264 unique sparsified edges.

Temporal correlation analysis

Autocorrelation (Fig. 10): The ACF decays slowly over 20 lags (1.5hrs), motivating the use of recurrent and dilated temporal modules.

6G feature statistics

BW distribution (Fig. 11): Uniform coverage over [-1.75, +1.75] validates our simulation strategy and the feature’s potential informativeness.

Spatio-temporal error heatmap

Error Heatmap (Fig. 12): Bright streaks at time indices 30–50 and 120–140 suggest episodic events (e.g. incidents). Persistent sensor-specific hotspots around sensor 100 align with previous outlier observations.

Summary of findings

Combining all analyses, we conclude:

-

Best model: DCRNN achieves the lowest normalized RMSE (0.0361) and lowest physical-unit MAE (0.85 mph), confirming superiority both in scale-free and real-world error terms.

-

6G feature impact: Naïve conditioning of slice-bandwidth and CQI did not improve forecasting, indicating the need for advanced fusion mechanisms.

-

Graph & temporal design: Dense topology and long temporal dependencies endorse diffusion-RNNs over shallow GCN or CNN methods.

-

Targeted refinements: A handful of sensors/timesteps account for most large errors, suggesting room for specialized local models or uncertainty-aware extensions.

These insights inform our final recommendations in Sect. "Discussion and future directions".

Discussion and future directions

In this section, we synthesize our empirical findings, situate them within the broader context of 6G-enabled Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), and outline concrete research pathways to advance the state of the art. We organize the discussion into four major themes: (1) interpretation of key results, (2) practical implications for ITS deployment, (3) methodological limitations, and (4) visionary future research directions.

The importance of jointly assessing predictive accuracy and computational cost has been emphasized across multiple domains. Deep temporal models for PEMFC degradation forecasting32, VoIP traffic prediction in mobile networks33, and real-time multivariate segmentation34 all highlight the necessity of rigorous performance–complexity evaluation. Our findings reinforce a similar conclusion: achieving low-latency inference at city-scale requires careful balancing between graph sparsity, receptive field size, and temporal modeling depth. The broader perspective offered by these works helped motivate our expanded comparison including AGCRN and Graph WaveNet-and strengthened the generalizability of our analysis.

Interpretation of key results: Our experiments (Sect. "Experimental results and analysis") benchmarked four architectures: ST-GCN6, ST-GAT12, DCRNN5, and our 6G-aware DCRNN6G. The quantitative and qualitative analyses yield several intertwined insights:

-

Superiority of diffusion-recurrent modeling: The core advantage of DCRNN over static graph-CNNs lies in its modeling of traffic propagation as a diffusion process on the road graph. Equation 30 formalizes how multi-hop flows are aggregated, capturing both upstream and downstream congestion wave phenomena that are well-documented in traffic flow theory4. Our RMSE reduction from 0.071 in ST-GCN to 0.036 in DCRNN represents more than a 50% improvement, corroborating earlier ICLR results5 and highlighting the importance of integrating spatial diffusion with temporal recurrence.

-

Latency–accuracy trade-offs: In real-time ITS, sub-25 ms inference is often required to support 5-minute forecasting intervals2. DCRNN meets this latency criterion (23.6 ms), whereas ST-GAT’s attention mechanisms incur 113 ms per batch. This underscores a critical design principle: increased architectural complexity (e.g. adaptive attention weights in ST-GAT, Eq. (29)) yields diminishing returns if latency constraints cannot be met. Similar observations have been made in the robotics domain, where model simplicity often trumps marginal accuracy gains under strict timing requirements29.

-

Marginal impact of Naïve 6G feature conditioning: Our DCRNN6G variant (Eq. 33) and the ST-GCN ablations (Table 6) reveal that simple concatenation or weighted diffusion by slice-bandwidth (BW) and channel-quality (CQ) yields only modest RMSE improvements ( 3% in ST-GCN+BW) at notable latency overheads. This aligns with findings in multi-modal fusion literature, where naïve feature stacking often fails to harness cross-modal synergies without sophisticated alignment or attention mechanisms37. It suggests that 6G metrics are only beneficial when integrated through mechanisms that can selectively attend to the most informative network conditions.

-

Interpretation of 6G-feature utility: The observation that 6G context features provide limited predictive benefit must be interpreted with caution. Because CQ and BW were sampled from simple independent distributions, the resulting signals lack realistic temporal and spatial dynamics observed in operational wireless systems. Real 6G traces-exhibiting fading, handover discontinuities, multi-slice orchestration, and congestion dynamics-may introduce stronger correlations with traffic states. Therefore, the present findings do not generalize to actual 6G deployments, but instead quantify performance under simplified synthetic conditions.

-

Error concentration and outlier dynamics: Our sensor-wise RMSE boxplots (Fig. 7) and spatio-temporal error heatmap (Fig. 12) show that although average errors are low, a small subset of sensors-often located at on-ramps, merges, or busy interchanges-and specific time windows account for the majority of large residuals. These “hard” cases likely correspond to non-recurrent congestion events or rapid demand fluctuations that violate the diffusion assumption. Similar patterns have been observed in urban transit studies, where incident detection modules are required to capture these anomalies31.

Practical implications for ITS deployment:

-

Edge inference feasibility: The sub-25 ms inference time of DCRNN on commodity CPU hardware suggests it can be deployed on roadside units (RSUs) or in-vehicle edge processors to provide near-real-time predictions. This capability enables dynamic traffic control strategies-such as adaptive ramp metering and variable speed limits-to react swiftly to predicted congestion patterns8.

-

Model maintenance and retraining cadence: Our experiments assume a static graph over a four-month data span. In practice, roadway networks and communication links evolve (construction, accidents, changing slice configurations). However, Fig. 9 shows the graph is nearly fully connected, implying that small topological changes may not substantially degrade model performance. Thus, periodic retraining (e.g. weekly or monthly) rather than continuous graph adaptation may suffice, reducing operational overhead.

-

Modular extension for local high-variance zones: The identification of persistent error hotspots at specific sensors suggests a hybrid modeling approach: deploy a global DCRNN for the majority of sensors, and lightweight specialized submodels or anomaly detectors for the few problematic nodes. Such modular architectures have been proposed in hybrid weather forecasting systems, improving tail-error performance without sacrificing global fluency35.

Methodological limitations: Despite its strengths, our study has several limitations that qualify the generality of our conclusions:

-

Synthetic nature of 6G features: The 6G-related variables (channel quality and slice bandwidth) in our experiments were generated from simple i.i.d. distributions to offer lightweight contextual signals; however, such synthetic features do not capture critical wireless behaviors, including small-scale fading, Doppler-induced variability, mobility-driven handovers, or slice-orchestration dynamics such as resource-block scheduling and admission control11. As a result, the modest performance gains observed for our 6G-aware variants (e.g. DCRNN6G) should not be interpreted as evidence that wireless context provides limited utility. Rather, the gap highlights the need for richer cross-modal modeling-e.g. attention-based fusion, heterogeneous graph integration, or co-training strategies-which may reveal substantially larger benefits when supplied with realistic 5G/6G telemetry. Bridging this simulation-to-reality divide using real operator datasets or high-fidelity network simulators remains an essential direction for future work.

-

Fixed window and horizon: We fix \(S=12\) and \(P=3\) (1hr input, 15min output). Although aligned with common practice23, different corridors or peak vs. off-peak periods may call for adaptive window sizing or multi-horizon forecasting, which can be addressed via hierarchical RNNs or dilated temporal convolutions25.

-

Point forecasts without uncertainty quantification: Our use of MSE loss (Eq. 34) yields point estimates and does not quantify predictive uncertainty. For applications like incident management or autonomous vehicle routing, measures of confidence (e.g. quantile regression42, Bayesian GNNs43) are critical.

-

Single-city focus: All experiments rely on the METR-LA dataset. While it is a standard benchmark, its freeway-centric topology differs from urban street grids or public transit networks. Cross-city validation using LOOP44 or PeMS-Bay datasets would strengthen external validity.

-

Simplified wireless modeling: A key limitation is the use of synthetically generated 6G features. These variables omit fading, mobility-driven handovers, slice-level resource orchestration, and spatiotemporally correlated wireless impairments. As a result, conclusions regarding the impact of 6G context should not be interpreted as reflective of real 6G environments.

Future research directions: Building on our insights and acknowledging the limitations, we identify five promising research directions:

-

Heterogeneous graph fusion: Develop fused graphs that jointly model road topology and communication infrastructure (e.g. base station locations, slice networks). Cross-graph attention mechanisms can learn when to attend to network vs. traffic signals, akin to coattention in multi-modal transformers45. Formally, one could define:

$$\begin{aligned} \beta _{ij} = \textrm{softmax}\bigl (\phi ([W_s s_i\Vert W_n n_j])\bigr ), \end{aligned}$$(37)where \(n_j\) are network nodes, enabling richer cross-domain message passing.

-

Dynamic graph learning: Incorporate temporal evolution of adjacency matrices \(A_t\) to reflect changing traffic patterns and network conditions. Approaches such as EvolveGCN28 use RNNs to update GCN weights over time; similar techniques could adapt edge weights based on recent traffic or CQI observations.

-

Incident-aware and multi-task forecasting: Augment the primary forecasting task with auxiliary tasks-such as incident detection or congestion classification-to help the model allocate capacity where it matters most. Multi-task learning frameworks have improved robustness in healthcare and finance applications37.

-

Probabilistic and Bayesian GNNs: Extend deterministic models to output full predictive distributions. Quantile regression networks42 or Bayesian GNN formulations35 can provide uncertainty bounds, crucial for risk-aware decision support.

-

Real-world 5G/6G testbed validation: Deploy and evaluate models on live 5G/6G testbeds with real network slicing, URLLC sessions, and mobility scenarios. Such studies will uncover practical issues-latency variance, measurement noise, packet loss-that are absent in simulations.

Concluding remarks

Our study presents a comprehensive and rigorously controlled evaluation of diffusion-based, convolution-based, and attention-based graph architectures for traffic forecasting under emerging 6G-aware conditions. While the overall architectural novelty is intentionally incremental-with synthetic 6G features and lightweight conditioning mechanisms-our contribution lies in providing the first unified and systematically benchmarked framework for assessing how wireless context may influence spatiotemporal traffic prediction. The results demonstrate that diffusion-recurrent models consistently deliver the most favorable balance between accuracy and real-time inference, whereas naïve 6G feature concatenation yields only modest gains under simplified synthetic conditions.

Importantly, to strengthen the reproducibility and future impact of this line of research, we plan to release our 6G-feature generator and full benchmarking pipeline as an open, stand-alone toolkit. Such a resource will enable the community to (i) easily simulate diverse wireless conditions, (ii) incorporate real 5G/6G traces when available, and (iii) perform controlled cross-modal ablations at scale. We believe this open benchmarking platform will support deeper investigations into advanced fusion mechanisms-such as cross-modal attention, heterogeneous graph coupling, and co-training strategies-and ultimately help unlock the full predictive benefits of real 6G telemetry in next-generation intelligent transportation systems.

Our study presents a comprehensive and rigorously controlled evaluation of diffusion-based, convolution-based, and attention-based graph architectures for traffic forecasting under emerging 6G-aware conditions. While the overall architectural novelty is intentionally incremental-with synthetic 6G features and lightweight conditioning mechanisms-our contribution lies in providing the first unified and systematically benchmarked framework for assessing how wireless context may influence spatiotemporal traffic prediction. The results demonstrate that diffusion-recurrent models consistently deliver the most favorable balance between accuracy and real-time inference, whereas naïve 6G feature concatenation yields only modest gains under simplified synthetic conditions.

Importantly, to strengthen the reproducibility and future impact of this line of research, we plan to release our 6G-feature generator and full benchmarking pipeline as an open, stand-alone toolkit. Such a resource will enable the community to (i) easily simulate diverse wireless conditions, (ii) incorporate real 5G/6G traces when available, and (iii) perform controlled cross-modal ablations at scale. We believe this open benchmarking platform will support deeper investigations into advanced fusion mechanisms-such as cross-modal attention, heterogeneous graph coupling, and co-training strategies-and ultimately help unlock the full predictive benefits of real 6G telemetry in next-generation intelligent transportation systems.

Conclusion

In this work, we have presented a comprehensive study of spatio-temporal graph neural networks for real-time traffic forecasting in the context of emerging 6G networks. Building on the METR-LA benchmark, we,

-

Developed a rigorous Dataset Description and Research Framework (Sect. "Dataset description and research framework"), including cleaned speed data, simulated slice-bandwidth and channel-quality features, and a sparse Gaussian-kernel graph representation.

-

Designed and implemented three baseline architectures-ST-GCN23, ST-GAT12, and DCRNN5-alongside our 6G-aware DCRNN6G variant that conditionally weights diffusion by slice-bandwidth (Sect. Methodology").

-

Proposed an enhanced training protocol featuring per-sensor normalization, early stopping, learning-rate scheduling, gradient clipping, and LayerNorm within diffusion GRU cells to ensure stable, reproducible performance.

-

Conducted exhaustive Experimental results and analysis (Sect. "Experimental results and analysis"), comparing accuracy (MAE, RMSE), inference latency, convergence behavior, error distributions, graph topology diagnostics, temporal correlations, and feature statistics across eleven figures and detailed ablation studies.

-

Demonstrated that DCRNN achieves the best accuracy–latency trade-off (RMSE 0.0361, 23.6ms) and that naïve 6G feature stacking yields only marginal gains, highlighting the need for more expressive multimodal fusion strategies.

-

Identified key limitations-synthetic network features, static graph assumption, lack of uncertainty quantification, and single-city focus-and outlined rich avenues for future work (Sect. "Discussion and future directions"), including heterogeneous graph fusion, dynamic adjacency learning, incident-aware modules, probabilistic forecasting, and real-world 5G/6G testbed validation.

Generalisability of 6G Findings:

Because the channel-quality and bandwidth traces were synthetically generated without incorporating fading statistics, handover events, or slice-management dynamics, the conclusions regarding the limited impact of 6G context are restricted to the simplified setting studied here. Richer and more realistic wireless traces may enable significantly stronger cross-modal benefits, as shown in recent works on channel-aware forecasting and network digital twins. Evaluating our framework on real 5G/6G logs, ray-tracing-derived channel maps, or open testbeds constitutes an important direction for future work.

Future work will incorporate realistic 6G measurements, such as ray-traced propagation data, OAI/ns-3-based emulation, and operator-derived slice telemetry, enabling a more faithful evaluation of how 6G dynamics influence short-horizon traffic prediction.

Limitations

While our study advances the state of the art, several limitations merit mention

-

1.

Synthetic 6G features: Our slice-bandwidth and CQI signals are simulated rather than measured from real networks, which may not capture the full complexity of 6G channel dynamics11.

-

2.

Static graph topology: We assume a fixed adjacency matrix over four months of data; urban road networks and communication links can evolve due to construction, incidents, or dynamic slicing, suggesting the need for dynamic graph learning28.

-

3.

Point forecasting only: We minimize MSE to produce point estimates and do not quantify predictive uncertainty, which is crucial for risk-aware traffic management and safety-critical applications43.

-

4.

Single-city evaluation: Our experiments focus solely on METR-LA; generalization to other cities with different road geometries or sensor deployments (e.g. LOOP44) remains to be validated.

-

5.

Fixed temporal horizon: We use a single input window (1hr) and forecast horizon (15min); adaptive windowing or multi-horizon forecasting could better capture diverse traffic patterns39.

Data availability

The datasets (METR-LA) analysed during the current study are available in the zenodo repository, https://zenodo.org/records/5146275.

References

Zheng, C., Qin, L. & et al. Urban flow prediction from spatio-temporal data with deep meta-learning. Proc. of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 1720–1730 (2020).

Vlahogianni, E. I., Karlaftis, M. G. & Golias, J. C. Short-term traffic forecasting: Where we are and where we’re going. Transport. Res. C 43, 1–19 (2014).

Box, G. E. P., Jenkins, G., Reinsel, G. & Ljung, G. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control (Wiley, 2015).

Treiber, M. & Kesting, A. Traffic Flow Dynamics: Data, Models and Simulation (Springer, 2013).

Li, Y., Yu, R., Shahabi, C. and Liu, Y. Diffusion convolutional recurrent neural network: Data-driven traffic forecasting. Preprint at arXiv:1707.01926 (2018).

Yan, S., Xiong, Y. & Lin, D. Spatial temporal graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proc. of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI, 2018).

Guo, S., Zhang, H., Li, X. & Shen, D. Attention based spatial-temporal graph convolutional neural network for traffic flow forecasting. In Proc. of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 33, 914–921 (AAAI Press, 2019).

Wu, Z. et al. Graph wavenet for deep spatial-temporal graph modeling. Preprint at arXiv:1906.00121 (2019).

Bai, L. et al. Adaptive graph convolutional recurrent network for traffic forecasting. NeurIPS 1494, 17804–17815 (2020).

Saad, W., Bennis, M. & Chen, M. A vision of 6g wireless systems: Applications, trends, technologies, and open research problems. IEEE Netw. 34, 134–142 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Reconfigurable intelligent surfaces: Principles and opportunities. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 23, 2274–2316 (2021).

Veličković, P. et al. Graph attention networks. In 6th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2018 (2018).

Contreras, J., Espínola, R., Nogales, F. J. & Conejo, A. J. Arima models to predict next-day electricity prices. In IEEE Power Engineering Society General Meeting, 287–292 (IEEE, 2003).

Kalman, R. E. A new approach to linear filtering and prediction problems. J. Basic Eng. 82, 35–45 (1960).

Cleveland, R. B., Cleveland, W. S., McRae, J. E. & Terpenning, I. Stl: A seasonal-trend decomposition procedure based on loess. J. Off. Stat. 6, 3–73 (1990).

Hyndman, R. J., Koehler, A. B., Snyder, R. D. & Grose, S. Forecasting with exponential smoothing: The state space approach. J. Forecast. 17, 201–218 (2002).

Wu, C., Ho, J.M.-H. & Lee, D.T.-W. Travel-time prediction with support vector regression. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 5, 276–281 (2004).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189–1232 (2001).

Zhang, J., Zheng, Y. & Qi, D. Deep spatio-temporal residual networks for citywide crowd flows prediction. Proc. of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 31, 1655–1661 (2017).

Shi, X. et al. Convolutional lstm network: A machine learning approach for precipitation nowcasting. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28 (NeurIPS), 802–810 (2015).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In 5th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2017).

Yu, B., Yin, H. & Zhu, Z. Spatio-temporal graph convolutional networks: A deep learning framework for traffic forecasting. In IJCAI, 3634–3640 (2017).

Cho, K. et al. Learning phrase representations using rnn encoder–decoder for statistical machine translation. In Proc. of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 1724–1734 (2014).

van den Oord, A. et al. Wavenet: A generative model for raw audio. Preprint at arXiv:1609.03499 (2016).

Song, C., Hao, H., Li, Y., Zhou, X. & Tang, B. Spatial-temporal synchronous graph convolutional networks: A new framework for traffic forecasting. In WSDM, 289–297 (2021).

Wu, Z. et al. Connecting the dots: Multivariate time series forecasting with graph neural networks. In Proc. of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 753–763 (2020).

Pareja, A. et al. Evolvegcn: Evolving graph convolutional networks for dynamic graphs. In AAAI, 5363–5371 (2020).

Zhang, Z. & et al. Semantic communication for 6g: A survey. Preprint at arXiv:2104.11353 (2021).

Xu, P., Zhang, Y., Wang, L., Wang, Y. & Liu, F. Deep learning for urban traffic flow forecasting: A survey. In ICASSP, 4700–4704 (2021).

Wang, Y., Zhu, C., Zhang, B. & Xiong, R. Application of deep learning for short-term traffic flow prediction. Transp. Res. Part C 129, 103205 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Li, H. & Wang, S. Prediction of the rul of pemfc based on multivariate time series forecasting model. In 2023 3rd International Symposium on Computer Technology and Information Science (ISCTIS), 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCTIS57420.2023.00012 (2023).

Tognola, G. et al. Multivariate time series characterization and forecasting of voip traffic in real mobile networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 20, 3020–3034. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSM.2023.3271238 (2023).

Chen, H., Xu, Y., Li, T. Speeding. & up multivariate time series segmentation using feature extraction. In IEEE 4th Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC), 1282–1287, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITNEC48623.2020.9084919 (2020).

Duvenaud, D. K. et al. Convolutional networks on graphs for learning molecular fingerprints. NeurIPS 28, 2224–2232 (2015).

Little, R. J. A. & Rubin, D. B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data 2nd edn. (Wiley, 2002).

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y. & Courville, A. Deep Learning (MIT Press, 2016).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition 770–778 (CVPR, 2016).

Lai, G., Chang, W.-C., Yang, Y. & Liu, H. Modeling long- and short-term temporal patterns with deep neural networks. In WWW, 695–704 (2018).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2019).

Wu, Z. et al. Graph WaveNet for deep spatial-temporal graph modeling. In Proc. of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), 1907–1913 (AAAI Press, 2019).

Lian, W. Z. et al. Learning traffic as images: A deep quantile approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 8, 7916–7924 (2020).

Tagasovska, N. & Lopez-Paz, D. Single-model uncertainties for deep learning. In NeurIPS, 7454–7465 (2019).

Jain, A., Mavrantzas, V., Gopalkrishnan, S. & Ramamritham, K. Loop: A large-scale real-world loop detector dataset for traffic prediction. In KDD, 2776–2786 (2020).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In NeurIPS, 6000–6010 (2017).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal University Jaipur.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. Chauhan (corresponding author) conceived and supervised the study, led manuscript writing. Y.K. Jain and P.K. Mannepalli performed data preprocessing, implemented models, and ran experiments. A. Pandey contributed to result analysis, visualization, and manuscript editing. All authors contributed to interpretation of results, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final submission. Correspondence should be addressed to Shishir Singh Chauhan (email: shishir.chauhan@jaipur.manipal.edu).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chauhan, S.S., Jain, Y.K., Mannepalli, P.K. et al. 6G conditioned spatiotemporal graph neural networks for real time traffic flow prediction. Sci Rep 16, 3902 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32795-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32795-0