Abstract

Intracellular accumulation of alpha-synuclein amyloids is a main pathological hallmark in a subgroup of human neurodegenerative diseases called synucleinopathies. Cell death of energy-deprived dopaminergic neurons causes decreased dopamine levels, which underly many of the neurological symptoms in the most prevalent synucleinopathy, Parkinson’s disease. Amyloid-mediated toxicity can proceed via gain-of-function through diverse pathways. In this work, we report that alpha-synuclein amyloids can degrade adenosine triphosphate in a catalytic fashion, producing adenosine diphosphate and adenosine monophosphate. Upon prolonged incubation, all adenosine triphosphate is irreversibly consumed. Furthermore, these amyloids can also degrade all other ribonucleotides with different efficiencies, including guanosine, cytidine, and uridine triphosphates. Our findings uncover a previously unknown gain-of-function for alpha-synuclein amyloids, which may have far reaching implications for ATP and nucleotide metabolism during neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

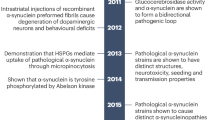

Accumulation of abnormally folded proteins as intermolecular aggregates called amyloids is a main feature underlying most neurodegenerative diseases1,2. Amyloids are highly ordered and stable aggregates that can propagate and accumulate in tissues3. Common structural features include the formation of oligomers and fibrils that share a core and stabilizing beta sheet. Synucleinopathies are neurodegenerative and chronic diseases affecting the human nervous system4. They share a common pathological feature characterized by progressive accumulation and aggregation of an intracellular protein called alpha synuclein (a-Syn)4,5. Parkinson’s disease (PD) is by far the most common synucleinopathy6. PD is characterized by progressive loss of motor function leading to rigidity and involuntary tremors, followed by non-motor neurological symptoms such as dementia7,8. The most affected brain tissue area is the substantia nigra, a midbrain zone loaded with dopaminergic neurons that fill the basal ganglia with the necessary levels of dopamine for proper control of voluntary motor9. Progressive death of these neurons leads to the onset of PD motor symptoms. As with most neurodegenerative disorders, to date there is no cure available for PD and other synucleinopathies.

In synucleinopathies, a-Syn accumulates as intracellular amyloid deposits. In PD and several other synucleinopathies, these deposits evolve into characteristic clumps called Lewy bodies10. Diverse evidence supports a direct association between pathology and a-Syn amyloids11,12. However, this association is complex and thus actively studied. Since a-Syn does not have an essential physiological function, the current evidence indicates that aggregated a-Syn species are per se toxic and underly the pathologies13,14. This gain-of-function can proceed through fibrillary or oligomeric states. For instance, a-Syn oligomers are highly toxic in cultured neuronal cells15,16. They can also easily spread and trigger synaptic impairment17. Intracerebral injection of a-Syn amyloid fibrils induces parkinsonism-like symptoms in rodent animal models18,19. At the cellular level, a-Syn amyloids can partially disrupt the mitochondrial membrane or interacts with respiratory protein, producing oxidative stress leading to cell death20,21,22,23. In fact, mitochondrial dysfunction is a well-known hallmark of PD in cellular and animal models, and in human postmortem tissue24.

Amyloids with catalytic activity can be assembled with rationally designed small peptides, which may lead to future nanomaterials25,26. Diverse activities have been reported in the literature, most of which are of hydrolytic nature such as hydrolysis of ester and phosphoanhydride bonds, whereas others include oxidation, retro-aldol condensation, etc. The amyloid state provides a catalytic surface onto which substrates can bind and be converted to products by action of catalytic groups repeated in ordered fashion along the fibers. However, this novel feature is not restricted to synthetic non-pathological amyloids27. b-amyloid is an extracellular peptide released by abnormal proteolytic cleavage that accumulates as amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease28. In vitro-produced b-amyloid fibrils can catalyze the hydrolysis and oxidation of several brain hormones and neurotransmitters29. Interestingly, amyloid fibrils assembled with recombinant a-Syn can catalyze the hydrolysis of phosphate and acetate from synthetic nitrophenyl compounds30. Moreover, these amyloids can modify the natural ratios of several intracellular metabolites in crude cell extracts, though no catalytic nor evidence of direct interaction was reported31. The same amyloids were recently shown to bind DNA and induce chemical damage32. These novel findings suggest that amyloid-mediated catalysis may have unforeseen and potentially key roles in pathology.

In this work, we explored whether a-Syn amyloids can directly catalyze the chemical modification of relevant metabolites. We previously showed that amyloids assembled with synthetic small peptides containing acidic residues can catalyze the hydrolysis of nucleotides, including adenosine triphosphate (ATP)33,34. a-Syn has a highly acidic 45-residues C-terminus preceded by a hydrophobic amyloid-prone middle region that can interact with nucleotides, including ATP. Thus, we tested whether purified recombinant a-Syn assembled into amyloids can chemically modify ATP and other nucleotides.

Results

a-Syn amyloids degrade ATP in a time-dependent manner

Purified a-Syn was seeded with previously assembled a-Syn amyloids to speed up aggregation. Upon incubation, the seeded amyloids were washed twice to remove monomers and potential contaminants. These isolated amyloids exhibited the characteristic Thioflavin-T fluorescence signal, with maximum emission centered around 488 nm, and classical amyloid fibril morphology by TEM analysis (supplementary figure S1). The isolated amyloids were then tested for activity. Initial trials showed phosphate release upon incubation of amyloids with ATP in a Tris-buffer saline solution (TBS, see Materials and Methods). To explore whether this activity is specifically in the amyloid fraction, we tested a separate experiment in which seeded α-Syn was centrifuged and the activity measured in the soluble and pellet fraction (supplementary figure S2). The activity was mostly contained in the pelleted fraction. Moreover, unseeded, and thus monomeric α-Syn supplemented with ATP did not produce activity.

The products of the catalytic reactions analyzed by HPLC following incubation of α-Syn with ATP for 24 h were ADP, AMP, and an unknown product (Fig. 1A). To study the time dependence of the hydrolytic activity, α-Syn was incubated with ATP at five different time points (Fig. 1B and C). At 2 h, ADP and AMP had similar but low concentration levels whereas the unknown product was barely detectable. ADP and AMP reached maximum values at around 6 h whereas the unknown product peaked at 48 h. AMP maximum concentration at 6 h was around three times higher than that of ADP. At 24 h, ADP was already undetectable whereas AMP started decreasing until reaching one ninth of unknown product concentration at 48 h. The results agree with the estimated concentrations of hydrolyzed ATP (Fig. 1D). At 2 h, ATP had already reached around 20% degradation. At 6 h around 90% of ATP was degraded, which increased to 98% at 24 h and to 99% at 48 h.

ATP degradation by a-Syn amyloids. (a) Products released from reactions run in triplicate for 24 h at 37 °C supplemented with 200 µM ATP in presence (straight dark blue line) or absence (dotted black line) of isolated a-Syn amyloids were analyzed by HPLC. Nucleotide absorbance (260 nm) was plotted as a function of the retention time with the indicated ATP degradation products. (b) The same reactions as in (a) and controls were run at 0 h, 24 h and 48 h and analyzed by HPLC in the same fashion. (c and d). Time evolution of the reaction products as analyzed by HPLC elution profiles (c) and total hydrolyzed ATP concentration (d) are plotted at different time points (0 h, 2 h, 6 h, 24 h and 72 h). Concentrations were estimated by the area of each peak. U.P. is unknown product.

ATP at physiological concentrations and AMP are substrates of a-Syn amyloids

ATP is present at very high concentrations in the cytoplasm of most cells. In neurons, ATP typically reaches cytoplasmic concentrations around 2 mM35. Therefore, we incubated isolated a-Syn amyloids with 2 mM ATP and analyzed the products by HPLC (Fig. 2A). At 24 h, ATP degradation reached around 15%, with ADP and AMP having the highest levels (Fig. 2B). ADP reached a concentration 2.5 times greater than AMP whereas the unknown product concentration remained detectable but very low. A 72-h long reaction produced an ATP degradation of around 57%, with ADP again peaking, followed by AMP and the unknown product. We also explored whether ATP degradation by a-Syn amyloids can occur at acidic pH, mimicking the environment of several intracellular organelles, such as lysosomes. Indeed, there is significant evidence for a connection between PD and lysosomal dysfunction, in which a-Syn amyloids appear to accumulate and spread36,37. The results show that a-Syn amyloids hydrolyze ATP at pH 4.0 in a similar fashion as pH 7.0 (supplementary figure S3).

Degradation of ATP at physiological concentration and AMP by a-Syn amyloids. (a) HPLC elution profile of the products released from reactions run in triplicate for 24 h at 37 °C supplemented with 2 mM ATP in presence (straight dark blue line) or absence (dotted black line) of isolated a-Syn amyloids. (b) The same reaction in (a) was plotted along a 72 h-long reaction as product concentrations transformed to percentage by the area of each peak. (c) Elution profile of the catalytic degradation of AMP (200 µM) by isolated a-Syn amyloids for 24 h at 37 °C. The inset shows the amount of hydrolyzed ATP quantified from the peak areas. U.P. is unknown product.

Since AMP is the minimal nucleotide form derived from ATP, we hypothesized that the unknown product was being released by a different chemical reaction than hydrolysis of the phosphoanhydride bonds of ATP or ADP. Thus, we explored whether the unknown product can be directly released from AMP. Upon a 24-h incubation with Syn amyloids, the unknown product was clearly detected by HPLC whereas in absence of a-Syn amyloids the substrate remained intact (Fig. 2C). Hydrolyzed AMP reached around 60% and the unknown product had the same mobility and spectral property than the one found in the previous experiments. The spectral properties of this unknown product obtained during the chromatographic runs indicated a peak absorbance around 250 nm, which suggests the presence of nucleotide derivatives. To further explore this, we did some modifications to the mobile phase and tested different nucleotide analytical standards. We found that the unknown product appears to be a combination of inosine monophosphate and inosine, though we also detected small amounts of adenosine in several cases.

Since ATP degradation proceeded exclusively in the presence of a-Syn amyloids, it is likely that the degradation products are released in a catalytic fashion33. Thus, we analyzed whether degradation followed a catalytic enzyme-like behavior. Upon mixing a-Syn amyloids with ATP at different concentrations in the linear range (2 h), we observed that ATP degradation followed a classical substrate saturation curve (Fig. 3). The fitted value for KM was around 200 µM (the concentration we used in most of the previous experiments) (Table 1).

Substrate saturation curve of ATP degradation by a-Syn amyloids. Isolated a-Syn amyloids were incubated in TBS with different ATP concentrations in triplicate for 2 h at 37 °C. The products were analyzed by HPLC, and the areas of all ATP degradation products were counted as total product concentration. The data was fitted through nonlinear fit using a Michaelis-Menten model.

a-Syn amyloids can degrade other nucleotides

We explored whether a-Syn amyloids can degrade other ribonucleotides, specifically guanosine triphosphate (GTP), cytidine triphosphate (CTP) and uridine triphosphate (UTP). We incubated isolated a-Syn amyloids with each ribonucleotide in separate tubes and analyzed the products by HPLC (Fig. 4A and B). The results showed that a-Syn amyloids can effectively degrade all the ribonucleotides albeit with different efficiencies. All three nucleoside triphosphates were degraded to nucleoside di- and monophosphates (Fig. 4A). As with ATP, we also observed the formation of a third hydrolytic product of unknown nature. Compared to ATP, GTP was the second most effectively degraded ribonucleotide, followed by CTP and UTP. ATP, GTP and CTP showed minor accumulation of nucleoside diphosphate, and the dominating species was the unknown product. For UTP, the reaction appear less efficient since uridine diphosphate is the main product, followed by uridine monophosphate and an unknown species. GTP and CTP reached almost full depletion (> 90%) whereas UTP remained at around 75% (Fig. 4B). We also tested whether other physiologically relevant nucleotides can be degraded by a-Syn amyloids, such as deoxyadenosine triphosphate (dATP) as the deoxyribonucleotide ATP counterpart, and a cyclic derivative of AMP (3’−5’ cAMP), a second messenger essential in signal transduction. A 48-h incubation of a-Syn amyloids and dATP led to almost full degradation (92%) of the nucleotide, releasing dAMP as the main species followed by an unknown product (Fig. 4C). As observed with ATP degradation, dADP was below the detection level. On the other hand, a-Syn amyloids were unable to degrade 3’−5’ cAMP, which remained virtually unaltered upon 48-h incubation (data not shown).

Degradation by a-Syn amyloids of other nucleotides. (a) Concentrations (expressed as percentage) of all degradation products determined by HPLC from reactions run in triplicate for 24 h at 37 °C supplemented with 200 µM of different nucleotides (ATP, GTP, CTP or UTP) in presence (straight dark blue line) or absence (dotted black line) of isolated a-Syn. (b) Hydrolyzed amount of each ribonucleotide expressed as percentage. (c) Concentrations of degradation products from a reaction containing isolated a-Syn amyloids supplemented with 200 µM dATP for 24 h at 37 °C. The inset shows the hydrolyzed dATP expressed as percentage. U.P. is unknown product.

Discussion

Our results evidence a novel gain-of-function for a-Syn amyloids that can have direct implications in pathological ATP metabolism. The degradation releases all hydrolytic nucleoside phosphate derivatives. ATP is rapidly degraded, and the remaining species are progressively degraded into subsequent products. The degradation is clearly catalytic and enzyme-like with substrate saturation. Although the present data is insufficient to determine a mechanistic pathway, the results provide strong evidence for a sequential degradation ATP -> ADP -> AMP -> unknown product, as these products accumulate orderly in time. This is further supported by the degradation acting directly over AMP and apparently yielding the same unknown product. Although we initially suspected this product to be adenosine, produced by hydrolysis of the remaining phosphate of AMP, its HPLC mobility and spectral properties indicated the presence of additional nucleotide derivatives. By using different nucleotides as analytical standards, we showed that this product appears to be mainly a combination of IMP and inosine, with adenosine showing up in several experiments. This suggests that a-Syn amyloids may effectively remove the remaining phosphate group, which is indicative of a phosphatase activity as previously reported30. However, our current data does not allow to discern whether the conversion proceeds as AMP→IMP→inosine or AMP→adenosine→inosine. In either case, these preliminary results imply that a-Syn amyloids may also catalyze adenosine deamination, which is a one-step hydrolytic reaction. Interestingly, among the enzymes that catalyze this reaction are AMP and adenosine deaminases, which have zinc ions coordinated to several histidine in the active site, reminiscent of the first and most studied type of catalytic amyloids38,39,40. We are currently studying these reactions and the corresponding products in greater detail.

We showed that ATP was degraded even at high and physiological concentrations. This is intriguing since ATP is currently recognized as a biological hydrotrope, meaning it can avoid protein aggregation by increasing the solubility of different proteins, including those prone to form amyloids41. However, recent findings demonstrated that the hydrotropic effects on a-Syn are complex, with a biphasic behavior in which low ATP concentrations reduce the aggregation lag-phase whereas high concentrations reduce the aggregation plateau42. The latter occurs only at very high and non-physiological ATP concentrations (> 10 mM), which can explain why a-Syn amyloids such as Lewy bodies can form and endure in the cytoplasm, especially in neurons in which ATP is around 2 mM. In fact, 2 mM ATP accelerates a-Syn aggregation without modifying the plateau. Our kinetic data show that at 2 mM, the activity of a-Syn amyloids is well in the saturated region, implying the amyloids are virtually at full catalytic operating capacity. We also found that a-Syn amyloids can degrade ATP at an acidic pH compatible with that of lysosomes. This is interesting since this organelle is not only an accumulation site for a-Syn amyloids but also contains abundant ATP37,43.

The association of a-Syn and ATP goes beyond hydrotropic effects44. ATP naturally binds in vitro to a-Syn monomers through electrostatic and nonpolar interactions, and since ATP is abundant in cells, such interactions may be ubiquitous and frequent in the cytoplasm42. In fact, we found in preliminary experiments that several nucleotides co-purify with a-Syn, which are effectively removed in the washing steps. It is thus plausible that ATP may not only colocalize with a-Syn amyloids inside cells but also accelerate and stabilize their formation at physiological concentrations, while promoting its own degradation.

There is abundant literature reporting impaired bioenergetics in neurodegenerative diseases, including PD44,45,46. Energy-demanding synapses and cytoplasmatic ATP levels are reduced early in PD, preceding neuronal death47. Dopaminergic neurons are particularly sensible to ATP levels due to constant dopamine production and release, two highly ATP-consuming processes48,49. Energy-impairment is partially associated to mitochondrial dysfunction in PD. a-Syn amyloids can bind and disrupt mitochondrial membranes and impair respiratory ATP production while increase ROS20,21,22,23. However, energy deprivation can also be linked to cytoplasmatic factors. Activation of phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (the first ATP-producing enzyme in glycolysis) by terazosin has shown significant protection against neurodegeneration and cell death in cellular and animal models of PD, and in several clinical studies50,51. Indeed, terazosin was recently reported to effectively boost ATP levels, suppressing metabolic stress in dopaminergic neurons, and acting as a leverage of metabolic impairments in PD52.

All this evidence points that optimal ATP levels are crucial in PD. Mitochondrial and cytoplasmatic ATP metabolism are evidently interconnected and thus diverse PD-associated metabolic dysfunctions are inescapably complementary. Future studies on the cellular implications of ATP degradation by a-Syn amyloids may shed new light on metabolic disfunction in PD. Overall, our results may underly a previously unrecognized pathogenic mechanism that could redefine ATP metabolism in PD and other synucleinopathies, paving the way for future targeted therapeutic interventions.

Materials and methods

Reagents

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Merck as highly pure salts, including all the nucleotides used in the study (ATP, ADP, AMP, IMP, adenosine, inosine, dAMP and cAMP), buffers and reagents for the catalysis and HPLC experiments.

Protein expression and purification

Recombinant α−Syn was expressed in E. coli (DE3) cells, which were grown at 37 °C under agitation in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin and induced with IPTG at O.D. around 0.6. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 14,000 x g and were suspended in a solution containing 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8 and 750 mM NaCl. The suspension was boiled for 20 min and centrifuged at 18,000 x g for 30 min and the pellet discarded. The supernatant was dialyzed against 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8 and 50 mM NaCl overnight (dialysis membrane of 3500 MWCO), and then loaded on a 5 mL HiTrap Q HP column (Cytiva) and eluted with a linear gradient (50–500 mM NaCl). The protein-containing fractions were collected, pooled together, and dialyzed against a solution with 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8 and 25 mM NaCl. Upon dialysis, the sample was centrifuged at 20,000 x g for 30 min and the soluble fraction was syringe-filtered (0.22 µM). The protein was concentrated using a 10,000 MWCO Amicon centrifugation filter (Milipore). Purity was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and the protein was separated in single-use aliquots and kept frozen at −40 °C.Final protein concentration was estimated using a standard BCA protocol (Pierce).

In vitro a-Syn aggregation

Amyloid formation was induced by addition of diluted premade a-Syn amyloids (seeds) to a-Syn monomers. The seeds were prepared by incubating freshly thawed a-Syn monomers at 250 µM in TBS buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4 and 150 m NaCl) for 8 days at 37 °C with continuous agitation. Upon completion, the seeds solution was stored frozen at −40 °C. The formation of a-Syn amyloids for the catalytic reactions was produced by mixing freshly thawed a-Syn seeds with monomer a-Syn, yielding a final concentration of 250 µM in TBS solution. The reaction was incubated for 5 days at 37 °C with continuous agitation. To separate amyloids from monomers and potential contaminants, the resulting a-Syn amyloids were washed by centrifugation for 30 min at 31,000 x g, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet resuspended in TBS solution. This washing step was repeated, and the final pellet (isolated a-Syn amyloids) was resuspended in TBS or solution for catalytic reaction.

TEM analysis and Thioflavin-T assay

Samples containing isolated a-Syn amyloids were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and Thioflavin-T assay. For Thioflavin-T assay, isolated a-Syn amyloids in TBS were supplemented with 25 µM ThT and the reaction was analyzed in triplicate by emission fluorescence in a plate reader (Tecan M200 Pro Infinity) with excitation set at 435 nm. For TEM analysis, 10 µL of isolated a-Syn amyloids in TBS were deposited for 5 min on previously ultraviolet light-activated carbon grids. The grids were then soaked in milli-Q water and negative stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 2 min, followed by a final soaking step. The grids were analyzed in a Talos F200 G2 (ThermoFisher Scientific) transmission electron microscope, loaded with a Ceta 16 M CMOS camera (16 bit) and the images were acquired and processed with a Velox imaging software.

ATP degradation assay

Isolated a-Syn amyloids from a seeded reaction containing a-Syn (200 µM) were suspended in TBS solution supplemented with different concentrations of ATP or other nucleotides. Control reactions lacking a-Syn were treated and run in parallel. The samples were incubated at 37 °C for different times (specified in the corresponding figures) under continuous agitation. The reaction products were analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or with a colorimetric kit for phosphate determination. For HPLC, the samples were syringe-filtered through a 0.22 µM filter and analyzed by HPLC (Agilent Infinity 1220 system loaded with diode-array detector) using an ion-pair reverse chromatography, as reported previously. Briefly, filtered samples (20 µL) were automatically loaded on a C18 column (Supelcosil LC-18-DB from Supelco) previously equilibrated with a mobile phase containing 50 mM K2HPO4, 20 mM glacial acetic acid and 3–7% (V/V) acetonitrile and followed at 260 nm (2 mL/min). Commercial nucleotides were used as standards under the same conditions to determine elution times, which remained stable throughout all the experiments. Product concentrations were determined using the in-house software by estimating the area under the curve of all the peaks and weighted by the total nucleotide concentration. For the colorimetric assay, the total phosphate content was estimated by using a commercial kit based on the malaquite-green assay and following the kit instructions (Enzo). The samples were spectrophotometrically analyzed in a plate reader set at 620 nm. All the results were analyzed and plotted using Prism Software (Graphpad).

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information.

References

Chiti, F. & Dobson, C. M. Protein misfolding, amyloid formation, and human disease: a summary of progress over the last decade. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86, 27–68 (2017).

Chun Ke, P. et al. Half a century of amyloids: past, present and future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 5473–5509 (2020).

Riek, R. The three-dimensional structures of amyloids. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 9, a023572 (2017).

Galvin, J. E., Lee, V. M. Y. & Trojanowski, J. Q. Synucleinopathies: clinical and pathological implications. Arch. Neurol. 58, 186–190 (2001).

Soto, C. et al. Toward a biological definition of neuronal and glial synucleinopathies. Nat. Med. 31, 396–408 (2025).

Farrer, M. J. Genetics of Parkinson disease: paradigm shifts and future prospects. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7, 306–318 (2006).

Xia, R. & Mao, Z. H. Progression of motor symptoms in parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Bull. 28, 39–48 (2012).

Pfeiffer, R. F. Non-motor symptoms in parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 22, S119–S122 (2016).

Ramesh, S., Arachchige, A. S. P. M., Ramesh, S. & Arachchige, A. S. P. M. Depletion of dopamine in parkinson’s disease and relevant therapeutic options: A review of the literature. AIMSN 10, 200–231 (2023).

Spillantini, M. G. et al. α-Synuclein in lewy bodies. Nature 388, 839–840 (1997).

Flagmeier, P. et al. Mutations associated with Familial parkinson’s disease alter the initiation and amplification steps of α-synuclein aggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 113, 10328–10333 (2016).

Marvian, A. T., Koss, D. J., Aliakbari, F., Morshedi, D. & Outeiro, T. F. In vitro models of synucleinopathies: informing on molecular mechanisms and protective strategies. J. Neurochem. 150, 535–565 (2019).

Stefanis, L. α-Synuclein in parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Med. 2, a009399 (2012).

Eriksen, J. L., Dawson, T. M., Dickson, D. W. & Petrucelli, L. Caught in the act: α-synuclein is the culprit in parkinson’s disease. Neuron 40, 453–456 (2003).

Killinger, B. A., Melki, R., Brundin, P. & Kordower, J. H. Endogenous alpha-synuclein monomers, oligomers and resulting pathology: let’s talk about the lipids in the room. Npj Parkinsons Dis. 5, 1–8 (2019).

Fusco, G. et al. Structural basis of membrane disruption and cellular toxicity by α-synuclein oligomers. Science 358, 1440–1443 (2017).

Diógenes, M. J. et al. Extracellular alpha-synuclein oligomers modulate synaptic transmission and impair LTP via NMDA-receptor activation. J. Neurosci. 32, 11750–11762 (2012).

Paumier, K. L. et al. Intrastriatal injection of pre-formed mouse α-synuclein fibrils into rats triggers α-synuclein pathology and bilateral nigrostriatal degeneration. Neurobiol. Dis. 82, 185–199 (2015).

Luk, K. C. et al. Intracerebral inoculation of pathological α-synuclein initiates a rapidly progressive neurodegenerative α-synucleinopathy in mice. J. Exp. Med. 209, 975–986 (2012).

Dryanovski, D. I. et al. Calcium entry and α-synuclein inclusions elevate dendritic mitochondrial oxidant stress in dopaminergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 33, 10154–10164 (2013).

Devi, L., Raghavendran, V., Prabhu, B. M., Avadhani, N. G. & Anandatheerthavarada, H. K. Mitochondrial import and accumulation of α-synuclein impair complex I in human dopaminergic neuronal cultures and Parkinson disease brain *. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 9089–9100 (2008).

Faustini, G. et al. Mitochondria and ?-Synuclein: friends or foes in the pathogenesis of parkinson’s disease? Genes 8, 377 (2017).

Ludtmann, M. H. R. et al. α-synuclein oligomers interact with ATP synthase and open the permeability transition pore in parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun. 9, 2293 (2018).

Pickrell, A. M. & Youle, R. J. The roles of PINK1, Parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in parkinson’s disease. Neuron 85, 257–273 (2015).

Diaz-Espinoza, R. Catalytically active amyloids as future bionanomaterials. Nanomaterials 12, 3802 (2022).

Marshall, L. R. & Korendovych, I. V. Catalytic amyloids: is misfolding folding? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 64, 145–153 (2021).

Arad, E. & Jelinek, R. Catalytic amyloids. Trends in Chemistry (2022).

Hardy, J. A. & Higgins, G. A. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 256, 184–185 (1992).

Arad, E., Baruch Leshem, A. & Rapaport, H. Jelinek, R. β-Amyloid fibrils catalyze neurotransmitter degradation. Chem. Catal. 1, 908–922 (2021).

Amyloid Fibers of. α-synuclein catalyze chemical reactions | ACS chemical neuroscience. https://pubs-acs-org.ezproxy.usach.cl/doi/https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.2c00799

Horvath, I., Mohamed, K. A., Kumar, R. & Wittung-Stafshede, P. Amyloids of α-synuclein promote chemical transformations of neuronal cell metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 12849 (2023).

Horvath, I. et al. Biological amyloids chemically damage DNA. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 16, 355–364 (2025).

Castillo-Caceres, C. et al. Functional characterization of the ATPase-like activity displayed by a catalytic amyloid. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-General Subj. 1865, 129729 (2021).

Monasterio, O., Nova, E. & Diaz-Espinoza, R. Development of a novel catalytic amyloid displaying a metal-dependent ATPase-like activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 482, 1194–1200 (2017).

Fukuda, J., Fujita, Y. & Ohsawa, K. ATP content in isolated mammalian nerve cells assayed by a modified luciferin-luciferase method. J. Neurosci. Methods. 8, 295–302 (1983).

Dai, L. et al. Lysosomal dysfunction in α-synuclein pathology: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 81, 1–19 (2024).

Xie, Y. X. et al. Lysosomal exocytosis releases pathogenic α-synuclein species from neurons in synucleinopathy models. Nat. Commun. 13, 4918 (2022).

Antonioli, L. et al. Adenosine deaminase in the modulation of immune system and its potential as a novel target for treatment of inflammatory disorders. Curr. Drug Targets. 13, 842–862 (2012).

Kaur, G. et al. Structural basis for the substrate specificity of helix pomatia AMP deaminase and a chimeric ADGF adenosine deaminase. Journal Biol. Chemistry 301, 1–11. (2025).

Rufo, C. M. et al. Short peptides self-assemble to produce catalytic amyloids. Nat. Chem. 6, 303–309 (2014).

Patel, A. et al. ATP as a biological hydrotrope. Science 356, 753–756 (2017).

Kamski-Hennekam, E. R., Huang, J., Ahmed, R. & Melacini, G. Toward a molecular mechanism for the interaction of ATP with alpha-synuclein. Chem. Sci. 14, 9933–9942 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Regulated ATP release from astrocytes through lysosome exocytosis. Nat. Cell. Biol. 9, 945–953 (2007).

Watanabe, H. et al. Brain network and energy imbalance in parkinson’s disease: linking ATP reduction and α-synuclein pathology. Front Mol. Neurosci 17, 1–11. (2025).

Strope, T. A., Birky, C. J. & Wilkins, H. M. The role of bioenergetics in neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 9212 (2022).

Saxena, U. Bioenergetics failure in neurodegenerative diseases: back to the future. Expert Opin. Therapeutic Targets 16, 351–354. (2012).

Shields, L. Y., Mendelsohn, B. A. & Nakamura, K. Measuring ATP in Axons with FRET. in Techniques to Investigate Mitochondrial Function in Neurons 115–131Humana Press, New York, NY, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6890-9_6

Rangaraju, V., Calloway, N. & Ryan, T. A. Activity-driven local ATP synthesis is required for synaptic function. Cell 156, 825–835 (2014).

Flores-Ponce, X. & Velasco, I. Dopaminergic neuron metabolism: relevance for Understanding parkinson’s disease. Metabolomics 20, 1–14 (2024).

Naeem, U. et al. Glycolysis: the next big breakthrough in parkinson’s disease. Neurotox. Res. 40, 1707–1717 (2022).

Cai, R. et al. Enhancing Glycolysis attenuates parkinson’s disease progression in models and clinical databases. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 4539–4549 (2019).

Kokotos, A. C. et al. Phosphoglycerate kinase is a central leverage point in parkinson’s disease–driven neuronal metabolic deficits. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn6016 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Victor Castro-Fernandez at Universidad de Chile for providing equipment used in some of the experiments.

Funding

This research was funded by Chilean research grants ANID FONDECYT 1211821 and ANID FONDECYT 13220108.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.CC. and R.DE. conceived the idea. C.CC. and E.N. performed the experiments. C.CC. and R.DE. analyzed the data. R.DE. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Castillo-Cáceres, C., Nova, E. & Diaz-Espinoza, R. Alpha-synuclein amyloids catalyze the degradation of ATP and other nucleotides. Sci Rep 16, 2921 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32888-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32888-w