Abstract

Embryo developmental rate and morphological grading are strongly associated with implantation potential. However, it remains unclear whether these parameters influence neonatal sex, which may be affected by embryo selection criteria. The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of embryo developmental rate and morphological grading on neonatal sex. This single-center retrospective study included 4278 singleton live births resulting from single embryos transfers, conducted between 2011 and 2024. Binary logistic regression was performed to evaluate the association between embryo developmental rate, morphological grading, and neonate sex. A significantly higher proportion of male live births was observed in blastocyst-stage transfers (55.3%) compared to cleavage-stage transfers (50.9%; P = 0.005). Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that day 5 blastocyst transfers were significantly associated with a higher likelihood of male neonates compared to day 3 embryo transfers (Adjusted odds ratio (aOR), 1.21; 95% confidence intervals (CI), 1.02–1.43; P = 0.027). Furthermore, day 5 blastocysts with expansion stages 4 and 5 showed 2.30-fold and 2.71-fold increased probabilities of male neonates, respectively, compared to expansion stage 3 blastocysts (aOR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.44–3.68; aOR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.54–4.77; P = 0.001). Additionally, TE grades B and C blastocysts demonstrated 39% and 57% reduced probabilities of male neonates, respectively, compared to TE grade A blastocysts in day 5 transfers (aOR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.48–0.79; aOR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.28–0.65; P < 0.001). In conclusion, the blastocyst transfer may influence neonatal sex ratios, particularly in day 5 blastocysts with expansion stages 4–5 and high TE scores.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An estimated 13 million or more babies have been born worldwide through assisted reproductive technology (ART), with this number continues to increase1. This growth underscores the importance of investigating the health outcomes and gender distribution of ART-conceived infants. Concerns regarding ART’s potential impact on the secondary sex ratio (SSR), defined as the proportion of male live births among all live births, have prompted extensive research into SSR patterns among ART-conceived neonates2,3,4.

Human embryonic development progresses from cleavage to the morula stage, ultimately forming a hollow, spherical blastocyst capable of uterine implantation. Embryonic growth rate and morphological parameters serve as critical selection criteria for embryo transfer. Virtually all clinics employ morphological assessment to optimize in vitro fertilization (IVF) success rates, though this approach may have unintended neonatal consequences. Previous research has shown that single blastocyst transfer (BT) involving high-quality inner cell mass (ICM) in frozen cycles is associated with an increased risk of preterm birth5. Additionally, there is a growing trend toward extended embryo culture to day 5 or 6 and BT, however, BT are associated with a higher likelihood of male neonates compared to cleavage-stage embryo transfers6,7.

This phenomenon may be attributed to the faster developmental rate of male embryos, potentially resulting in a greater proportion reaching the blastocyst stage and being selected for transfer8,9,10. Nevertheless, the underlying causes of this gender imbalance remain unclear and may associate with patient-related factors, ART techniques, or embryonic characteristics. The association between BT and sex ratio is also inconsistent across studies, with some reporting no significant link and suggesting potential influence from confounding variables2,11,12,13. Therefore, further investigation on the relationship between embryo developmental rate, morphological parameters, and SSR is needed. This study aimed to evaluate whether the day of transfer, embryos developmental rate, morphological parameters of cleavage-stage embryos, and trophectoderm (TE) and ICM scores of blastocysts are associated with SSR at birth.

Materials and methods

Participants

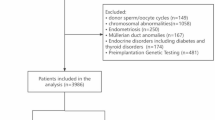

Data for this retrospective analysis of neonatal sex ratios were collected from the Center for Reproductive Medicine between 2011 and 2024. The study included 4278 singletons resulting from fresh / frozen cycles involving the transfer of single embryos. Exclusion criteria were: (1) cycles involving pre-implantation genetic testing (PGT); (2) use of donor gametes (oocytes or sperm).

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the 901st Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of PLA (IRB number: LY2023YGZD06). All methods are conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Demographic characteristics

The study variables included neonatal sex, parental age, maternal body mass index (BMI), infertility type (primary or secondary), ovarian stimulation (OS) protocol (agonist or antagonist), sperm separation method (swim-up or density gradient centrifugation), insemination method (conventional IVF [C-IVF] or intracytoplasmic sperm injection [ICSI]), cycle type (fresh or frozen), stage of embryo transfer (cleavage-stage or blastocyst), embryo developmental rate (for cleavage-stage embryos: number of blastomeres on day 3 at transfer; for blastocyst-stage embryos: expansion stages 3–5 achieved by day 5 or day 6), and morphological parameters. For cleavage-stage embryos, morphological grading was defined as: good (< 10% fragmentation with even symmetry), fair (11–20% fragmentation with moderate asymmetry), and poor (21–50% fragmentation with severe asymmetry). For blastocyst-stage embryos, ICM and TE were graded as A, B, or C based on Gardner’s scoring system14.

The blastocyst expansion stage was defined as follows: 1 = early blastocyst (blastocoel < 50% of the embryo volume); 2 = blastocyst (blastocoel fills 50% of the embryo volume); 3 = full blastocyst (blastocoel > 50% of the embryo volume); 4 = expanded blastocyst (blastocoel larger than the embryo with thinning zona pellucida); 5 = hatching blastocyst (trophectoderm herniating through the zona pellucida); 6 = hatched blastocyst (blastocyst completely escaped from the zona pellucida). The ICM and TE was graded as follows: ICM: A = many tightly packed cells; B = several loosely packed cells; C = very few cells. TE: A = many cells forming a cohesive epithelium; B = several cells organized in a loose epithelium; C = very few large cells. To minimize inter-observer variation in embryo grading, embryos are assessed by at least two trained embryologists.

Ovarian stimulation and fertilization

OS protocols were conducted using either gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist or agonist regimens, as previously described15. Briefly, gonadotropin (Gn) dosing was adjusted during ovarian stimulation based on follicular growth and serum hormone monitoring. Ovulation was triggered with human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) when at least three follicles reached a diameter of ≥ 18 mm. Transvaginal ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval was performed approximately 36 h post-trigger. Fertilization was accomplished via C-IVF or ICSI, based on semen analysis results.

Vitrification and warming

Embryo vitrification and warming were performed using a commercial kit (Kitazato, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, prior to vitrification, blastocysts were subjected to artificial shrinkage via laser-assisted collapse. Embryos were first placed in equilibration solution (ES) for 8–10 min, followed by exposure to vitrification solution (VS) for 1 min. Embryo was then loaded onto a Cryotop device (Kitazato, Japan) and immediately plunged into liquid nitrogen.

For warming, the Cryotop was rapidly transferred from liquid nitrogen into thawing solution (TS) at 37 °C for approximately 1 min. The embryo was subsequently placed in diluent solution (DS) for 3 min at room temperature, followed by two sequential washes in washing solution (WS) for 5 min each. After warming, embryos were cultured in G2-plus medium (Vitrolife, Sweden) before embryo transfer.

Embryo transfer

A single embryo was transferred under abdominal ultrasound guidance using a Wallace catheter. All patients subsequently received luteal phase support with oral dydrogesterone administered at a dosage of 10 mg twice daily.

Outcomes and data variables

The primary outcome was SSR (the proportion of male live births among all live births) following SET. This study exclusively enrolled singleton births, with monozygotic twin pregnancies excluded from analysis.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using Student’s t-test. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages (%, n/N) and analyzed using the Chi-square test. Multivariate binary logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the association between cycle type, embryo developmental rate, morphological grading, and neonate sex. The adjusted model included parental age, maternal BMI, infertility type, sperm separation method, insemination method, cycle type. Adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated as a measure of strength of associations. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Between 2011 and 2024, a total of 4278 singleton live births were included in this study, comprising 2293 male and 1985 female neonates, resulting in a male ratio of 53.6%. Baseline characteristics and sex ratios are presented in Table 1. No significant differences in neonatal sex ratios were observed for parental age, maternal BMI, infertility type, OS protocol, sperm separation method, or insemination technique, etc. However, BT demonstrated a significantly higher SSR compared to cleavage-stage embryo transfers (55.3% [1451/2624] vs. 50.9% [842/1654]; P = 0.005). Additionally, frozen-frozen cycles showed a higher SSR than fresh cycles (54.9% [1406/2562] vs. 51.7% [887/1716]; P = 0.040).

As shown in Table 2, multivariate binary logistic regression was performed to evaluate the association between fresh/frozen cycles, embryo developmental stage (day 3, day 5, and day 6), and SSR. The analysis revealed that day 5 BT was significantly associated with a higher SSR compared to day 3 embryo transfer (aOR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.02–1.43; P = 0.027). However, no significant difference in SSR was observed between frozen and fresh cycles (aOR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.94–1.30; P = 0.246), or between day 6 BT and day 3 embryo transfer (aOR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.79–1.37; P = 0.775).

In fresh cycles, the distribution of embryo transfers was as follows: day 3 (77.9%; 1337/1716), day 5 (21.9%; 376/1716), and day 6 (0.2%; 3/1716). In frozen cycles, the distribution was: day 3 (12.4%; 317/2562), day 5 (74.7%; 1915/2562), and day 6 (12.9%; 330/2562). A statistically significant difference was observed in the distribution of embryo transfers on days 3, 5, and 6 between fresh and frozen cycles (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1).

Compared to the reference 7–9 cells group, < 6, 10–12, or > 13 cell groups did not increase the likelihood of male neonates. Similarly, compared to the reference good morphology group, neither the fair nor poor morphology groups were associated with an increased likelihood of male neonates (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

In day 5 embryo transfers, the SSR varied significantly with developmental rate. Blastocysts with expansion stage 4 (aOR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.44–3.68; P = 0.001) or 5 (aOR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.54–4.77; P = 0.001) showed a higher likelihood of male neonates compared to those with expansion stage 3. Additionally, TE grades B and C blastocysts demonstrated 39% and 57% reduced probabilities of male neonates, respectively, compared to TE grade A blastocysts in day 5 transfers (aOR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.48–0.79; aOR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.28–0.65; P < 0.001). However, no significant association was observed between ICM grades and the neonatal sex (P > 0.05) (Table 4).

In day 6 embryo transfers, adjusted analysis revealed no significant association between expansion stage (3–5), ICM grade (A-C), or TE grade (A-C) and the SSR (P > 0.05) (Table 5).

Discussion

Embryo morphology and developmental rate are well-established critical determinants of successful implantation. However, embryologists and clinicians frequently prioritize morphological grading when selecting embryos, often neglecting the potential influence of developmental rate and morphological characteristics on neonate while focusing on maximizing success rates. In this study, our main findings demonstrate that BT is associated with an increased likelihood of male neonates compared to cleavage-stage embryos transfer, consistent with previous studies16,17. Further, day 5 blastocysts with expansion stages 4 and 5 exhibited 2.30-fold and 2.71-fold increased probabilities of male neonates, respectively, compared to expansion stage 3 blastocysts. Additionally, TE grades B and C blastocysts demonstrated 39% and 57% reduced probabilities of male neonates, respectively, compared to TE grade A blastocysts in day 5 transfers.

The primary limitation of this study is its single-center design, which may restrict the generalizability of findings compared to multicenter studies or national database analyses. The single-center design offers distinct advantages, including reduced confounding factors, standardized embryo grading criteria, and minimal inter- and intra-observer variability, thereby enhancing internal consistency offering comparable results. Furthermore, potential bias from confounders was minimized through adjusted regression models controlling for parental age, maternal BMI, types of ovarian stimulation protocol and infertility, sperm separation method, insemination method, and cycle type. Additionally, this study spanned an extended period, during which significant modifications were implemented to the protocols for cumulus cell denudation and embryo transfer to G1PLUS medium (Vitrolife). Initially, a subset of 3–5 oocytes was denuded at 4 h post-insemination (hpi) to assess fertilization status (confirmed by the presence of two polar bodies) and determine the need for rescue ICSI (threshold: ≥60% of oocytes lacking two polar bodies). Unless rescue ICSI was required, the remaining oocytes were transferred to G1PLUS medium the following day. To minimize oocyte exposure and manipulation, the protocol was revised in 2017: all oocytes are now fully denuded at 4 hpi, uniformly assessed for rescue ICSI eligibility, and fertilized oocytes are transferred immediately to G1PLUS medium.

The sex ratio at birth serves as a crucial indicator of population health and fertility. Over the past four decades, the number of ART-conceived births has increased exponentially, necessitating investigation into whether laboratory techniques or clinical OS protocols influence neonatal sex ratios. Previous studies have reported ART associated sex ratio imbalances. Wang et al. demonstrated that ICSI resulted in a lower proportion of male births compared to IVF (OR = 0.808, 95% CI: 0.681–0.958)18. A large retrospective cohort study of 91,805 embryo transfer cycles revealed that PGT blastocyst transfers were associated with a 2% higher likelihood of male births compared to non-PGT blastocyst transfers (RR = 1.02; 95% CI: 1.01–1.04), and a 5% higher likelihood compared to non-PGT cleavage-stage transfers (RR = 1.05; 95% CI: 1.02–1.07)19. Additional studies have shown that good-quality blastocysts are associated with an increased proportion of male neonates20, embryo culture medium composition influences singleton sex ratios15, and elevated SSR are linked to ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS)21 and OS protocols22. However, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, and these findings remain controversial11,23,24,25.

Earlier reports have suggested BT does not lead to a sex ratio imbalance in resulting offspring and male embryos do not exhibit faster developmental rates than female embryos in culture24. A recent multicenter study also confirmed that blastocysts with expansion stage 6 had a higher rate of male neonates compared to those with expansion stage 4 + 3 (84.4% vs. 54.9%), without analyzing the day of embryo transfer separately26. In the present study, we observed a significant association between the developmental rate of day 5 blastocysts and male embryos, with faster-developing blastocysts more likely to result in male neonates. Specifically, blastocysts with expansion stages 4 and 5 demonstrated 2.30-fold and 2.71-fold increased probabilities of male neonates, respectively, compared to those with expansion stage 3. However, no such associations were observed in day 6 embryos. These findings are partially consistent with a previous multicenter study, which reported that blastocysts with expansion stage 5 were 34% more likely to result in male neonates compared to those with expansion stage 3, while no significant differences were observed for expansion stages 4 and 6. Notably, the study did not analyze day 5 and day 6 blastocysts separately3. One potential explanation for the mechanisms underlying sex ratio bias involves genes located on the X chromosome that regulate glucose uptake, metabolism, and antioxidant enzymes. These genes may lead to differential responses of male and female embryos to in vitro culture conditions. Specifically, total glucose metabolism is twice as high in male embryos compared to female embryos, while the activity of the pentose phosphate pathway is four times higher in female blastocysts than in male blastocysts27,28. The double-dose activity of X chromosome-linked genes regulating glucose metabolism (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) and antioxidant pathways (e.g., hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase) may contribute to differences in energy metabolism and developmental rates between male and female embryos. The lower levels of oxygen radicals in female embryos, resulting from the double dose of hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase, may cause developmental delays, while male embryos, with appropriate levels of oxygen radicals, may reach the blastocyst stage earlier than females27,29.

To optimize success rates, blastocysts with high TE and ICM scores based on the Gardner grading system are prioritized for transfer. However, this practice may contribute to sex ratio imbalances in neonates30. Baatarsuren et al. demonstrated that TE grade influences neonatal sex ratios in single blastocyst transfer cycles, with grade A TE blastocysts showing a 280% higher probability of male births compared to grade C TE blastocysts31. Our results demonstrated that only day 5 blastocysts with TE grade A showed a 39% and 57% higher likelihood of male neonates compared to TE grades B and C, respectively, while ICM grade showed no significant association with neonatal sex. The human blastocyst gives rise to TE as the primary cell type, which forms the placenta. Placentas derived from male fetuses are typically larger than those from female fetuses32 and male and female pre-gastrulation embryos exhibit significant differences in TE lineage differentiation33. Furthermore, female embryos exhibit a higher overall mortality rate during pregnancy compared to male embryos34. TE morphology is also associated with implantation success and pregnancy outcomes, particularly regarding the risk of miscarriage, suggesting that higher TE grades may improve clinical outcomes35. Our results demonstrated no significant association between the developmental rate or morphological grading of day 3 embryos and neonatal sex. We hypothesize that this phenomenon may be attributed to the predominance of maternal gene regulation during early embryonic development or under the control of the maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT)36.

In summary, a notable positive correlation was observed between neonatal sex and both the developmental stage and TE grading of day 5 embryos, with male births being associated with higher scores. As elective single blastocyst transfer is increasingly adopted as the standard approach to mitigate the risks linked to multiple pregnancies, clinicians and embryologists may have inadvertently contributed to the tendency for blastocyst transfers to result in a higher proportion of male neonates.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adamson, G. D. et al. How many infants have been born with the help of assisted reproductive technology? Fertil. Steril. 124, 40–50 (2025).

Marconi, N., Raja, E. A., Bhattacharya, S. & Maheshwari, A. Perinatal outcomes in singleton live births after fresh blastocyst-stage embryo transfer: a retrospective analysis of 67 147 IVF/ICSI cycles. Hum. Reprod. 34, 1716–1725 (2019).

Borgstrom, M. B. et al. Developmental stage and morphology of the competent blastocyst are associated with sex of the child but not with other obstetric outcomes: a multicenter cohort study. Hum. Reprod. 37, 119–128 (2021).

Hu, K. L. et al. Blastocyst quality and perinatal outcomes in women undergoing single blastocyst transfer in frozen cycles. Hum. Reprod. Open. 2021, hoab036 (2021).

Bakkensen, J. B. et al. Association between blastocyst morphology and pregnancy and perinatal outcomes following fresh and cryopreserved embryo transfer. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 36, 2315–2324 (2019).

Shi, W. et al. Comparison of perinatal outcomes following blastocyst and cleavage-stage embryo transfer: analysis of 10 years’ data from a single centre. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 38, 967–978 (2019).

Ugwu, A. O., Makwe, C. C. & Kay, V. Analysis of the factors affecting the male-female sex ratio of babies born through assisted reproductive technology. West. Afr. J. Med. 41, 818–825 (2024).

Ardhani, F., Okamoto, A. & Shimada, M. Glucose-Induced developmental dynamics: Understanding male prevalence in early mouse embryo stages. Reproductive Med. Biology. 24, e12667 (2025).

Du, T. et al. Factors affecting male-to-female ratio at birth in frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles: a large retrospective cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1188433 (2023).

Carrasco, B. et al. Male and female blastocysts: any difference other than the sex? Reprod. Biomed. Online. 45, 851–857 (2022).

Nagata, C. et al. Sex ratio of infants born through in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer: results of a single-institution study and literature review. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 25, 337–340 (2021).

Cai, H., Ren, W., Wang, H. & Shi, J. Sex ratio imbalance following blastocyst transfer is associated with ICSI but not with IVF: an analysis of 14,892 single embryo transfer cycles. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 39, 211–218 (2022).

Wang, S., Chen, L., Fang, J., Jiang, W. & Zhang, N. Comparison of the pregnancy and obstetric outcomes between single cleavage-stage embryo transfer and single blastocyst transfer by time-lapse selection of embryos. Gynecol. Endocrinology: Official J. Int. Soc. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 35, 792–795 (2019).

Gardner, D. K., Lane, M., Stevens, J., Schlenker, T. & Schoolcraft, W. B. Blastocyst score affects implantation and pregnancy outcome: towards a single blastocyst transfer. Fertil. Steril. 73, 1155–1158 (2000).

Zhu, J. et al. Association between etiologic factors in infertile couples and fertilization failure in conventional in vitro fertilization cycles. Andrology 3, 717–722 (2015).

Dean, J. H., Chapman, M. G. & Sullivan, E. A. The effect on human sex ratio at birth by assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedures–an assessment of babies born following single embryo transfers, Australia and New Zealand, 2002–2006. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 117, 1628–1634 (2010).

Maalouf, W. E., Mincheva, M. N., Campbell, B. K. & Hardy, I. C. Effects of assisted reproductive technologies on human sex ratio at birth. Fertil. Steril. 101, 1321–1325 (2014).

Wang, M. et al. Associated factors of secondary sex ratio of offspring in assisted reproductive technology: a cross-sectional study in Jilin Province, China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 20, 666 (2020).

Shaia, K., Truong, T., Pieper, C. & Steiner, A. Pre-implantation genetic testing alters the sex ratio: an analysis of 91,805 embryo transfer cycles. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 37, 1117–1122 (2020).

Jia, N., Hao, H., Zhang, C., Xie, J. & Zhang, S. Blastocyst quality and perinatal outcomes of frozen-thawed single blastocyst transfer cycles. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1010453 (2022).

Jia, Q. et al. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome is associated with a high secondary sex ratio in fresh IVF cycles with cleavage-stage embryo transfer: results for a cohort study. Reproductive Sci. 28, 3341–3351 (2021).

Al-Jaroudi, D., Salim, G. & Baradwan, S. Neonate female to male ratio after assisted reproduction following antagonist and agonist protocols. Medicine 97, e12310 (2018).

Bakkensen, J. B., Speedy, S., Mumm, M. & Boots, C. Sex ratio of offspring is not statistically altered following pre-implantation genetic testing under a specific sex selection policy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 308, 1605–1610 (2023).

Weston, G., Osianlis, T., Catt, J. & Vollenhoven, B. Blastocyst transfer does not cause a sex-ratio imbalance. Fertil. Steril. 92, 1302–1305 (2009).

Kausche, A. et al. Sex ratio and birth weights of infants born as a result of blastocyst transfers compared with early cleavage stage embryo transfers. Fertil. Steril. 76, 688–693 (2001).

Wang, T. et al. Sex ratio shift after frozen single blastocyst transfer in relation to blastocyst morphology parameters. Sci. Rep. 14, 9539 (2024).

Tiffin, G. J., Rieger, D., Betteridge, K. J., Yadav, B. R. & King, W. A. Glucose and glutamine metabolism in pre-attachment cattle embryos in relation to sex and stage of development. J. Reprod. Infertil. 93, 125–132 (1991).

Peippo, J. & Bredbacka, P. Sex-related growth rate differences in mouse preimplantation embryos in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 40, 56–61 (1995).

Gutierrez-Adan, A., Oter, M., Martinez-Madrid, B., Pintado, B. & De La Fuente, J. Differential expression of two genes located on the X chromosome between male and female in vitro-produced bovine embryos at the blastocyst stage. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 55, 146–151 (2000).

Lou, H. et al. Does the sex ratio of singleton births after frozen single blastocyst transfer differ in relation to blastocyst development? Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 18, 72 (2020).

Baatarsuren, M. et al. The trophectoderm could be better predictable parameter than inner cellular mass (ICM) for live birth rate and gender imbalance. Reprod. Biol. 22, 100596 (2022).

Eriksson, J. G., Kajantie, E., Osmond, C., Thornburg, K. & Barker, D. J. Boys live dangerously in the womb. Am. J. Hum. Biology: Official J. Hum. Biology Council. 22, 330–335 (2010).

Lu, Y. et al. Sex differences in human pre-gastrulation embryos. Sci. China Life Sci. 68, 397–415 (2025).

Orzack, S. H. et al. The human sex ratio from conception to birth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E2102–2111 (2015).

Hamidova, A. et al. Investigation of the effects of trophectoderm morphology on obstetric outcomes in fifth day blastocyst transfer in patients undergoing in-vitro-fertilization. J. Turkish German Gynecol. Association. 23, 167–176 (2022).

Vastenhouw, N. L., Cao, W. X. & Lipshitz, H. D. The maternal-to-zygotic transition revisited. Development 146 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge all the work of the staff from Reproductive Medicine Center of the 901st Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of PLA.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the 901st Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of the PLA (grant numbers: 2023YGZD06). The funding source had no role in conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JZ and FN were conducted on the project’s development, data collection, and manuscript preparation and editing. HQY was involved in data management and analysis. CLW, ZYC, KL, and YW collected data and offered paper comments. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the 901st Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of PLA (IRB number: LY2023YGZD06). The ethics committees waived informed consent for this retrospective study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, J., Ni, F., Wang, C. et al. The association of embryo developmental rate and morphological grading with neonatal sex ratio. Sci Rep 16, 3216 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33091-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33091-7