Abstract

In the realm of electromagnetic field simulation and in solving current density-related issues, traditional numerical methods are often hindered by inefficiencies and limited adaptability. This study introduces a physics-informed neural network (PINN) model predicated on current density, addressing the shortcomings of conventional Poisson equation solvers and enhancing computational efficacy and flexibility. By harnessing the synergies between physical-mathematical insights and deep learning, we have constructed a neural network model imbued with a priori knowledge of physics and mathematics, thereby facilitating an efficient resolution of the Poisson’s equation. The model is evaluated in two distinct scenarios: simulating electromagnetic pulses generated by laser-target interactions and calculating the electric field for field-circuit coupling integration. The empirical results indicate that the PINN-based solution methodology not only achieves a remarkable acceleration in computation speed but also maintains commendable accuracy, and the relative error is less than 1.4%, while bolstering adaptability to variations in current density. This research not only presents a novel and potent tool for addressing electromagnetic field simulation and current density challenges but also underscores the broad applicative potential of PINN in the domains of electromagnetic field simulation and potential forecasting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The core of computational electromagnetic algorithms lies in the accurately solving of the Poisson’s equation under various excitations and boundary conditions. Typical methods include the finite difference method1, finite element method2, and discontinuous Galerkin method3,4. Although these approaches are generally mature and effective in many scenarios, their computational efficiency and accuracy remain limited when confronted with the curse of dimensionality5 and high-dimensional parameters6. Moreover, previously obtained solutions cannot be reused when solving new problems.

With the rapid development of big data technology, deep learning has been successfully applied to high-dimensional problems in various fields such as electromagnetic fields7, thermal fields8, and stress fields9. The different neural networks models for solving dynamical problems arising in different fields such as weather/natural calamities forecasting, damage detection10.Deep learning establishes the mapping between input parameters and field solutions by leveraging deep neural networks (DNNs) or convolutional neural networks (CNNs)11. Data-driven approaches can solve partial differential equations (PDEs) without resorting to physical equations. Specifically, neural networks are used as operator approximators to solve parameterized PDEs, learning the direct mapping from PDE parameters to solutions using large amounts of labeled data. For instance, The Deep Operator Network12, Fourier Neural Operator13, and their variants14 have demonstrated outstanding performance in applications such as multiphysics prediction15 and numerical simulations of porous media16. However, current operator learning methods primarily focus on single-domain problems.

The principle of Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs)17 is to transform the process of solving partial differential equations into an optimization problem over neural network weights, enabling the neural network to satisfy various excitations and boundary conditions18, understand physical phenomena, and approximate physical systems19. PINNs have been widely applied in numerous scientific and engineering domains. Examples include achieving continuous, high-resolution, and accurate solutions of flow fields over coffee cups20, solving both forward and inverse problems for the Burgers equation21, approximating the displacement of an object in mass-spring-damper systems22, implementing accurate inertial-based navigation for mobile robots23, modeling intricate boundary conditions and nonlinear water diffusion characteristics20, and inferring unknown turbulent electric fields and potential distributions21.

Deep learning methods for solving Poisson’s Equation equation have also been utilized to accelerate electrostatic simulations. For example, CNNs have been employed to analyze flexibility under complex distributions of excitation sources and dielectric constants22, PINNs embedding the Poisson equation have been used to address magnetostatic problems23, DNNs have been constructed for plasma-coupled systems24, and applications of the Poisson equation in dynamic scenarios have been explored25. However, as highlighted in the literature26,27,28, the generalization abi\({\nabla ^2}\phi = - \frac{\rho }{{{\varepsilon _0}}}\)li\(\phi\)\({\nabla ^2}\)ty of the aforementioned deep learning methods is limited because the field source parameters are not included as inputs. Therefore, these approaches cannot be directly applied to different sources, and retraining is required when the source changes.

In this paper, building upon PINN25 and extending the application in22, we propose a macroscopic model based on current sources. The network takes as input data the location of excitation sources, and outputs the potential distribution within the computational domain. The loss function consists of data loss, physics loss, and field loss, among others. This approach addresses the poor adaptability of traditional Poisson equation solvers and the need for retraining in deep learning methods when the field source changes. Consequently, it improves computational efficiency but also enhances adaptability to variations in current density.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Sect. 2 describes the detailed design of the current-density-based PINN model, including network architecture construction and loss function design. Section 3 presents numerical experiment results, including performance evaluation and comparative analysis in different application scenarios. Section 4 discusses the advantages, limitations, and future research directions of the method, and concludes with a summary of the main contributions of the paper.

Finite difference methods for poisson’s equation

Poisson’s equation in physics mainly describes phenomena such as electric potential and temperature distributions, revealing the relationship between the source term and the field strength, which he can write as in (1):

Here: is the Laplace operator, is the scalar field to be solved for, ρ is the source term, ε0 is the dielectric constant.

Setting up a network in 3D space, defining points (i, j,k).The discretized center difference is obtained for each of the three directions29, the discrete form of Eq. (1)can be written as in (2),(3):

Where, \(\Delta x,\Delta y,\Delta z\) are the grid spacings in the x, y, and z directions, respectively, and \(i,j,k\) denote the corresponding discrete grid indices in those directions.

Here, Eqs. (4) and (5) define the unknown vector and the source-term vector, respectively.

We define matrix A as a three-dimensional(3D) Poisson’s equation matrix, as in (6). It is a sparse block matrix with a structure similar to the 3D Laplace operator, whose elements have values at the positions on the diagonal and adjacent diagonals, and the rest of the positions are 0. This sparse matrix can be expressed as:

Among them, each A corresponds to a two-dimensional sparse matrix, which is similar to the following, as in (7).

Similarly, we solve it using the Gauss-Seidel iterative method30; as in (8).

Where, b denotes the source-term vector; the iteration employs a step-by-step update scheme.

In the process of solving the 3D Poisson’s equation we find that defining different coordinate systems, the form of Poisson’s equation is not the same, in this paper we use the form of spherical coordinate system by (9).

Where,, \(r,\theta ,\varphi\) denote the radial coordinate, polar angle, and azimuthal angle, respectively.

The distribution and flow characteristics of the current are characterized using the scatter of the current density based on the current density in three dimensions, as in (10).

The current density is used to derive the properties of the electric field and thus predict the electric field distribution. The Poisson’s equation for the current density integrated incorporated is given in (11).

Physical neural network models

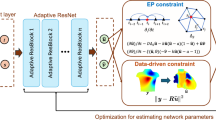

Based on the above mathematical model of Poisson’s equation, we develop a deep neural network that leverages the physical information of current density to solve Poisson’s equation. The framework is shown in Fig. 1, which contains three modules: (1) deep neural network, (2) automatic differentiation with PDE residuals, and (3) loss function.

Deep neural network

In Fig. 1, the deep neural network module consists of an input layer, a hidden layer, an output layer that uses the activation function Tanh to capture nonlinear features. The input layer receives the current density as the input features, the hidden layer extracts the information layer by layer via learned weights and nonlinear activation function such as Tanh, and the output layer finally generates the solution of Poisson’s equation. The Tanh activation is zero-centered and outputs values in (− 1, 1), which helps stabilize neuron outputs and reduce numerical instability. In practice, since the Tanh function resembles a linear function when the input is near 0 and is centered at 0, it often performs better than a function such as Sigmoid in applications.

The network depth and width were chosen to capture the complexity of the input data; specifically, we used three hidden layers with 50 neurons per layer. During training, the network learns the mapping between inputs and outputs through a backpropagation algorithm. The network weights were adjusted using the Adam optimization algorithm or SGD + Nesterov momentum with the aim of minimizing the loss function and improving the predictive power of the model. We trained for 50 epochs, with a mini-batch size of 500, an initial learning rate of 0.02, and a learning-rate decay of 0.007, and we updated the network parameters using the built-in Adam optimizer. In order to ensure the model’s ability to generalize, the data preprocessing and enhancement strategies are also an important part of the network design. The performance of the model on different datasets was evaluated by dividing the training, validation and test sets. In addition, regularization techniques such as L2 regularization or Dropout were introduced to prevent overfitting. Deep neural networks provide a powerful data-driven approach to solve Poisson’s equation through hierarchical information processing.

Automatic differentiation and PDE residuals

Automatic differentiation(AD) is an important tool in deep learning to compute gradients efficiently. With the chain rule, automatic differentiation can accurately solve the partial derivatives of each parameter, significantly speeding up the training process. For solving Poisson’s equation, we need to optimize the network parameters by a gradient descent algorithm to minimize the loss function. For the 3D Poisson’s electric field, the predicted potential components in x, y, and z dimensions are automatically differentiated.

Since the current density is a vector, the scattering of the current density needs to be considered, and the scattering is also calculated using the AD. In the experiment we predict the electric field based on the current density as a breakthrough point, so the AD of the current density is crucial. Residual connections allow information to propagate across layers in the network, helping to mitigate the problem of vanishing gradients. By constructing shortcut paths, residual networks allow for deeper models without causing performance degradation. This is especially critical for capturing complex physical phenomena and multi-scale features. To evaluate the difference between the network output and the actual physical equations, the residuals can be defined as in (12).

The residual R(x) indicates whether the left and right sides of Poisson’s equation are equal at the point x. If R(x) = 0, this means that Poisson’s equation is satisfied at that point. Conversely, if R(x) ≠ 0, this means that the solution at that point does not satisfy the equation. During training, we minimize the mean squared residual so that R(x) approaches zero by tuning the network parameters. This is achieved by tuning the parameters of the neural network. According to Poisson’s equation residual formula, the component-wise residuals in the three spatial dimensions are given in (13).

Loss function

The loss function is the core of training deep neural networks and directly affects the performance of the model. In our Poisson’s equation solution, the loss function is usually designed to include both data loss and physical loss components. The data loss is used to measure the difference between the network output and the true value, while the physical loss quantifies the degree of compliance between the model solution and the physical laws that Poisson’s equation needs to satisfy.

In this study, the design of the loss function is centered around the properties of Poisson’s equation, and the mean square error MSE is usually chosen as the main loss indicator., In order to conform to the physical information loss of the experimental scenario, Poisson’s equation constraint loss is used as a soft constraint for this neural network, and Poisson’s equation constraints involved are (14), (15).

where ϕi is the true potential value, \({\mathop \phi \limits^{ \wedge } _i}\)is the predicted potential value, and n is the number of samples, \({\nabla ^2}{\mathop \phi \limits^{ \wedge } _i}\)is the Laplace operator for the predicted potential, ρi is the charge density, and ε0 is the dielectric constant in vacuum.

An electric-field constraint is also incorporated into the loss function, as in (16).

Where \({\mathop E\limits^{ \wedge } _{x,i}} {\mathop E\limits^{ \wedge } _{y,i}}{\mathop E\limits^{ \wedge } _{z,i}}\)are the predicted values in the x, y, and z dimensions, respectively, and \({E_{x,i}} {E_{y,i}} {E_{z,i}}\)are the true values in the X, Y, and Z dimensions.

Based on the different weight shares of numerical and physical losses, the total loss is found to be (17).

In this work, we adopt a hybrid loss strategy combining data-driven supervision and physics-based constraints. This design accelerates convergence and improves predictive accuracy, particularly in complex electromagnetic scenarios where purely physics-driven PINN training may converge slowly or yield suboptimal solutions.

To train the PINN model, the corresponding algorithm is as follows. The flowchart of the algorithm for the PINN model is shown in Fig. 2.

-

(1)

Specify the engineering scenario and collect relevant parameters.

-

(2)

Generate multi-scenario current density samples.

-

(3)

Obtain electromagnetic field samples in a vacuum environment via FDM or other numerical solvers.

-

(4)

Split the sample data into training, validation, and test sets, and normalize the data.

-

(5)

Determine the model’s inputs, outputs, and stopping threshold T for training.

-

(6)

Design a hybrid loss function combining data loss (MSE), physics loss (PDE residuals), and field constraint losses.

-

(7)

Train the PINN model using suitable hyperparameters and the hybrid loss function as the optimization objective.

-

(8)

Evaluate the accuracy and generalization capability of the PINN model using the validation and test sets.

-

(9)

If the mean relative error is below the specified threshold T, training is complete; otherwise, adjust the model’s hyperparameters and repeat step 7.

-

(10)

Test the final PINN model and compare its performance with traditional methods such as FDM.

Results and analysis

When analyzing the model, it is important to consider the effect of boundary conditions on the scene. Here we used the Dirichlet boundary conditions to prevent the occurrence of current overflow boundary caused by the experimental error on the model training, to limit the boundary of the region of the current change, and to reduce the error at the same time to improve the accuracy and efficiency of the training.

Model validation

Here we use the two-dimensional FDM to solve Poisson’s equation. Poisson’s equation can be transformed into a discrete form by approximating the differential operator with the finite difference format. This is converted into a system of algebraic equations by replacing the derivatives or partial derivatives with the difference quotient to form a matrix of Poisson’s equations. We solve the resulting linear system with an iterative method that converges rapidly, which makes it superior to traditional methods in terms of time efficiency.

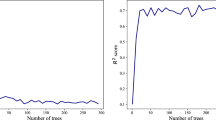

Figure 3 shows the performance of the PINN model. In order to further verify the robustness of the model, we also conducted several sets of experiments, including different network architectures, training data volumes, and hyperparameter settings. The results show that PINN can stably output high-precision solutions with errors of less than 0.3% in a wide range of cases. This not only proves the effectiveness of PINN as an emerging numerical solver for physics problems, but also demonstrates its potential for solving Poisson’s equation with current density.

In summary, the feasibility and effectiveness of PINN in solving Poisson’s equation is verified by comparing the finite-difference solution with the results of PINN.

Model application and simulation

In numerical tests, we solve the two-dimensional square-domain static and dynamic electric-field problems by applying the Dirichlet boundary conditions to truncate the computational domain without loss of generality. In the 2D model, the region is divided into 50 × 50 grid cells with a grid size of about 0.2 m × 0.2 m. By solving the electric field problem within this 50 × 50 grid, the relative permittivity is assumed to be the relative permittivity in vacuum: 8.854 × 10− 12 F/m.

In the static electric field, Poisson’s equation is solved conventionally, with the addition of PINN for training, and the input array is sized for a current density of 100 × 100 (2D). The size of the output array is a 50 × 50 electric-field map, and the reference model is compared with the PINN model to compute the relative error; in the dynamic electric-field, due to the limitation of Poisson’s equation in time, we can only discretize the time, the input array is in addition to the size of the current density of 100 × 100 (2D), and a new temporal array of 50 × 50 is introduced. The output array has a field strength of size 50 × 50 and a corresponding time array. The current change and electric field change for the whole time are predicted for the next time step and then analyzed for error. To verify the accuracy, several scenarios are created for solving in order to analyze the application of its solution method on various fields.

In the 2D simulations, we modeled four different scenarios to validate the applicability of this model, and due to the transient nature of the current propagation, the characteristic times are on the order of nanoseconds (ns):

Simulation of electromagnetic pulse generated by laser-target interaction

In the calculation of electromagnetic pulse (EMP) generation due to laser-target interactions, several challenges arise from the inherent complexity of the physical processes involved. These include accurately modeling nonlinear effects and plasma dynamics, characterizing the propagation and radiation of electromagnetic waves, and addressing the need for high-precision numerical simulations. Additionally, the computational demands are significant due to the large-scale simulations required to capture the full range of physical phenomena. These challenges make precise and efficient modeling of EMP generation a highly complex task. Figure 4 (a), (b) show the discrete and predicted solutions by EMP generation from laser-target interactions.

Figure 4(c) shows the computational performance of the PINN model in calculating the laser-target excitation. We establish a square region containing a target mask in the middle for simulating a planar target; the relative permittivity is the relative permittivity in vacuum; when the laser is incident, there is a current excitation and spreads over time; and because this scene is a dynamic electric field, the prediction is made using a temporal discretization.

Field-circuit coupling integrated electric-field calculation

In the process of field-circuit coupling integrated electric field calculation, several challenges arise due to the strong coupling between the electric field and particle trajectories, which can lead to numerical instability. Additionally, field-circuit coupling simulations often require long time-scale analyses, resulting in significant computational demands. The problem also involves the coupling of multiple spatial and temporal scales, from microscopic particle motion to the macroscopic distribution of the electromagnetic field, necessitating careful handling of scale transitions. To address these challenges, we evaluate the stability and efficiency of the PINN model using three field–circuit coupling scenarios.

Normal current transfer simulation

Figure 5 (a), (b) shows the discrete and predicted solutions by the same phase field and the half-phase difference sinusoidal field. Figure 5 (c) shows the computational performance of the PINN model in calculating the electric field generated by the normal current transfer. We use a square domain; the current propagates along the diagonal path y = x. The current is simulated to be transferred by a wire, and the change in electric field is predicted to vary with time.

Parallel current transfer simulation

Figure 5 (d), (e) shows the discrete and predicted solutions by the in-phase parallel phase-excited tangent field and the half phase difference parallel phase-cutting tangent field. Figure 5(f) shows the computational performance of the PINN model in calculating the electric field generated by the parallel currents. We construct a model similar to the normal current-transfer case but with multiple parallel currents to test whether current interactions significantly affect prediction accuracy and to verify the reliability of the training process.

Simulation of vortex electric field model

Figure 5(g), (h) shows the discrete and predicted solutions by the vortex electric field. Figure 5(i) shows discrete and predicted solutions by the computational performance of the PINN model in calculating the vortex electric field. In order to further explore the application of the model in electromagnetic field theory, we established a vortex electric field model formed by induced currents, which is also common in daily life, and firstly constructed a circular area with radius 1, defined the magnetic permeability as vacuum permeability, described the current density through polar coordinates, randomly selected the initial phase of the current, and selected several different values of angular velocity to analyze the effect of different changes in velocity on the predictions, which are 10, 50, 100, 200, and 300 for these cases, while the total time as well as the time step is kept constant.

The input of the combined network consists of two 50 × 50 arrays—a coordinate matrix and a current-density matrix—and the output is a 50 × 50 array representing the potential distribution in the target domain. In each scenario, we generate 1000 samples, of which 800 are used for training and 200 for testing. In total, the training dataset contains 3200 (800 × 4) samples, while the test dataset contains 800 (200 × 4) samples. minimized by the Adam optimizer. An NVIDIA GeForce RTX4050Laptop GPU card was used as the computing platform. The initial learning rate is 0.02 and the learning rate decays to 0.007. For quantitative evaluation, we compute the average relative error between the predicted potentials of the PINN and the computed potentials of the FDM. The relative error in the subdomain can be defined as in (18).

where i, j denotes the single cell indexes of the different grids. The error maps of the above four scenes are obtained by the sub-domains corresponding to the corresponding positions in the grid.

In Fig. 6, most of the errors are concentrated between 0.02 and 0.08, and the error distribution is close to the normal distribution, with an average error of about 0.05. This shows that the model has a good prediction effect on the test set, and the error of most samples is low. For intuitive explanation, we plot the histogram of the average relative error on a linear scale of all samples in the testing data set, as shown in Fig. 7.

Four results from scenario 1 to 4 were randomly selected from the test dataset. We observed that the difference between the predicted potential of PINN and the calculated potential of FDM is very small, and the average error is less than 0.15%. In the 2D simulations, we consider four possible cases, including a large number of different current density distributions with different shapes and values. For 10,000 models, FDM requires 102.21 s, while the PINN model only takes 0.18 s to compute the two-dimensional potential field. The results show that PINN achieves accuracy comparable to classical methods), especially when dealing with complex geometric and nonlinear problems, PINN exhibits greater flexibility and adaptability. In addition, PINN is able to optimize gradually and converge quickly during the training process, which makes it more time-efficient than the classical methods.

To further verify the robustness of the proposed PINN model and examine the influence of random initialization, we conducted supplementary experiments using four different random seeds (0, 42, 123, and 587).The training data preparation, network architecture, and optimization parameters were kept identical to the main experiments, with only the random seed controlling the initialization and data shuffling changed. Evaluation was performed across the four distinct scenarios described, using the same average relative error metric as in (18).

As shown in Table 1, the average relative error across all seeds and scenarios remains below 0.16%, with standard deviations less than 0.01%. The convergence curves for all seeds exhibit similar trends, and the final solutions are visually indistinguishable from those obtained in the main experiments.

These findings indicate that the proposed PINN model is insensitive to random initialization, and the conclusions presented in this work are not dependent on a specific seed choice.

Conclusion and discussion

In this investigation, we introduce a PINN model predicated on current density for addressing the solution of Poisson’s equation. The model is evaluated in two scenarios: simulating electromagnetic pulses generated by laser-target interactions and calculating the electric field for field-circuit coupling integration. Our findings demonstrate the model’s capability to achieve accelerated computational performance and enhanced generalization, aligning with the methodological rigor required for advanced computational electromagnetism. By meticulously constructing and training the PINN, we have successfully forecasted the potential fields within the domain of interest, with an average relative error below 1.4% in 2D scenarios. This accuracy rivals that of traditional FDM solvers, yet with a significantly reduced computational time, thereby underscoring the potential of PINNs in providing reliable simulations with considerable efficiency.

The implications of our study extend beyond the computational domain, suggesting a novel avenue for solving complex physical phenomena, such as those encountered in electromagnetism. Our work not only advances the frontier of computational electromagnetism but also paves the way for future research aimed at leveraging PINNs to solve Maxwell’s equations. This represents a significant step forward in the quest for high-fidelity, efficient computational tools in the field of computational physics.

It should be noted that while recent methods such as Symplectic Neural Networks (SNN) and Deep Operator Networks (DeepONet) have advanced physics-based modeling, they are mainly suited for conservative dynamical systems or require large datasets for operator learning. Their applicability to complex engineering electromagnetic problems, such as field-line coupling under electromagnetic pulses, remains limited. Due to the lack of a unified experimental platform for these scenarios, we provide an indirect comparison based on theoretical analysis and literature review.

As summarized in Table 2, PINNs can directly embed physical constraints and exhibit strong generalization for complex boundaries and multi-source environments, making them particularly suitable for the electromagnetic pulse and field-line coupling problems studied here.

In conclusion, the present study has engineered a PINN model that not only meets but exceeds the current benchmarks for solving Poisson’s equation. The model’s superior performance and adaptability highlight the potential for PINNs to revolutionize the simulation of electromagnetic fields and current density problems. As we look to the future, the exploration of this technique’s applicability to more complex equations, such as Maxwell’s equations, remains a promising avenue of research.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Teixeira, F., Sarris, L. & Zhang, C. Y. Finite-difference time-domain methods. Nat. Rev. 3(1).75 (2023).

Yee, K. S. Numerical solution of initial boundary value problems involving maxwell’s equations in isotropic media. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 14 (3), 302–307 (1966).

Shen, J., Tang, T. & Wang, L. L. Spectral Methods: algorithms, Analysis and Applications (Springer Science & Business Media, 2011).

Gopalakrishnan, J. Kan,G.A multilevel discontinuous Galerkin method. Numer. Math. 95 (3), 527–550 (2003).

Ern, A. & Guermond, J. L. Discontinuous Galerkin methods for friedrichs’ systems. I. General theory. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 44 (2), 753–778 (2006).

Dosopoulos, S. & Lee, J. F. Interior penalty discontinuous Galerkin finite element method for the time-dependent first order maxwell’s equations. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 58 (12), 4085–4090 (2010).

Y, Che, Q., Yang., Y. & Li Data-driven deep convolutional neural networks for electromagnetic field Estimation of Transformers. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 34 (8), 1–5 (2024).

Liu, Y., Gao, Y. & Liu, G. Fast calculation of flow-thermal coupling in oil‐immersed transformer windings based on u‐net neural network. AIP Adv. 13(3), 1–14 (2023).

A N,Maria Antony, Narisetti., N. & Gladilin, E. FDM data driven U-Net as a 2D Laplace PINN solver. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 9116 (2023).

Sahoo, A. K. & Chakraverty, S. Machine intelligence in dynamical systems:\A state-of‐art review. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. : Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 12 (4), e1461 (2022).

Chakraverty, S., Sahoo, A. K. & Mohapatra, D. Artificial Neural Networks and Type-2 Fuzzy Set (Elements of Soft Computing and Its Applications. Elsevier, 2025).

Lu, L., Jin, P. & Pang, G. Learning nonlinear operators via deeponet based on the universal approximation theorem of operators. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3(3), 218–229 (2021).

Lam, R., Sanchez-Gonzalez, A. & Willson, M. Learning skillful medium-range global weather forecasting. Sci 382 (6677), 1416–1421 (2023).

Guibas, J. & Mardani, M. & Li, Z. Efficient token mixing for Transformers via adaptive fourier neural operators. in ICLR, Vol. 4047. 1–15 (2021).

Cai, S., Wang, Z. & Lu, L. DeepM&Mnet: inferring the electroconvection multiphysics fields based on operator approximation by neural networks. J. Comput. Phys. 436, 110296 (2021).

Wen, G., Li, Z. & Azizzadenesheli, K. U. FNO—An enhanced fourier neural operator-based deep-learning model for multiphase flow. Adv. Water Res. 163, 104180 (2022).

Karniadakis, G. E., Kevrekidis, I. G. & Lu, L. Physics-informed machine learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3 (6), 422–440 (2021).

Jagtap, A. D., Kawaguchi, K. & Em Karniadakis, G. Locally adaptive activation functions with slope recovery for deep and physics-informed neural networks. Proc. R Soc. A. 476 (2239), 20200334 (2020).

Chinnappan, C. C. Integrating data-driven and physics-based approaches for robust wind power prediction: A comprehensive ML-PINN-Simulink framework. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 1–29 (2025).

Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P. & Karniadakis, G. E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 378, 686–707 (2019).

Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P. & Karniadakis, G. E. physics informed deep learning (Part I): data-driven solutions of nonlinear partial differential equations.preprint, arXiv: 1711.105611 (2017).

Sahoo, A. K., Kumar, S. & Chakraverty, S. An unsupervised scientific machine learning algorithm for approximating displacement of object in mass-spring-damper systems. IEEE Access. 12, 147753–147761 (2024).

Sahoo, A. K., Klein, I. & MoRPI-PINN A Physics-informed framework for mobile robot pure inertial navigation. ArXiv Preprint arXiv :250718206 (2025).

Li, Y., Sun, Q. & Fu, Y. Solving the Richards infiltration equation by coupling physics-informed neural networks with Hydrus-1D. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 18649 (2025).

Mathews, A., Hughes, J. & Francisquez, M. Uncovering edge plasma dynamics via deep learning of partial observations. Bull. Am. Phys. Soc. TO10. 007(2020). (2020).

Liu, J., Sun, Y. & Eldeniz, C. Image reconstruction using deep priors learned without groundtruth. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal. Process. 14 (6), 1088–1099 (2020).

Shan, T., Tang, W. & Dang, X. Study on a fast solver for poisson’s equation based on deep learning technique. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 68 (9), 6725–6733 (2020).

Baldan, M., Di Barba, P. & Lowther, D. A. Physics-informed neural networks for inverse electromagnetic problems. IEEE Trans. Magn. 59 (5), 1–5 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Fu, H. & Qin, Y. Physics-informed deep neural network for inhomogeneous magnetized plasma parameter inversion. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 21 (4), 828–832 (2023).

Liu, T. R., Aldakheel, F. & Aliabadi, M. H. Virtual element method for phase field modeling of dynamic fracture. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 411, 116050 (2023).

David, M. & Méhats, F. Symplectic learning for hamiltonian neural networks. J. Comput. Phys. 494, 112495 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Major Scientific and Technological Projects of Universities in Hebei Province (241130467 A).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization was conducted by Zhiwei Gao and Cheng-An Sun. Zhiwei Gao and Cheng-An Sun. developed the methodology.Formal analysis was performed by Zhiwei Gao, Cheng-An Sun, Zibin Ma, Zhijie Liu, Li Zhao and Qingmin Wang.The original manuscript was drafted by Cheng-An Sun. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Z., Sun, CA., Ma, Z. et al. Fast electromagnetic field simulation using a current-density- based physics-informed neural network. Sci Rep 16, 3168 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33166-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33166-5