Abstract

The scope of time series anomaly detection is increasingly shifting from univariate to multivariate contexts, as a growing number of real-world problems can no longer be adequately addressed by analyzing individual variables in isolation. Consequently, multivariate time series anomaly detection is not only in high demand but also presents significant challenges. However, existing methods struggle with a dual challenge: capturing subtle, fine-grained frequency features, and effectively modeling complex inter-channel dependencies. Current channel-handling strategies are often either too restrictive, like Channel-Independent (CI) methods that ignore valuable correlations, or susceptible to noise, like Channel-Dependent (CD) methods that indiscriminately integrate all relationships. To address these challenges, we propose the Frequency Filtering Time Series Transformer (FreFilterTST), a novel framework that uniquely combines frequency-domain inpainting with adaptive Frequency-Amplitude filtering. Specifically, FreFilterTST first reconstructs the input sequence from spectral patches to establish a rich representation of normative patterns. Subsequently, a Transformer-based Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture acts as an adaptive filter, dynamically identifying and preserving the most critical Frequency-Amplitude dependencies while pruning irrelevant or noisy ones. This can allow our model to overcome the inherent trade-offs of conventional CI and CD approaches. Our Extensive experiments on six benchmark public datasets demonstrate that FreFilterTST achieves an excellent performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The proliferation of multi-sensor systems in fields such as cyber-physical monitoring has led to an abundance of multivariate time series data, fundamentally altering the data analysis landscape1. This data’s defining characteristic-a complex web of inter-variable dependencies-simultaneously offers the rich relational information needed for nuanced pattern recognition while posing the central analytical challenge of disentangling meaningful correlations from spurious noise1,2. While this conundrum permeates all facets of time series analysis, its implications are particularly acute in Multivariate Time Series Anomaly Detection (MTSAD). The objective here is to identify rare deviations from an intricate normative baseline, a task of critical importance. The imperative for high-fidelity detection is underscored by its application in diverse fields, including credit card fraud detection3, human activity recognition4, urban monitoring5, and medical diagnosis6, communications technology7 where misclassification can have significant consequences.

Time-series data is characterized by its autocorrelation, where observations at different points in time are correlated. A fundamental task in analyzing such data is to decompose it into its constituent components, typically trend, seasonality, and random noise8. In the context of anomaly detection, classical approaches categorize anomalies into three main types. Point anomalies (or global anomalies) are individual data points that are outliers relative to the entire dataset, either due to extreme values or an unusual combination of features. Contextual anomalies are instances that are abnormal only within their local neighborhood. Finally, collective anomalies refer to a sequence of data points that is anomalous as a group, even if individual points are not9. While this taxonomy is foundational, distinguishing these types, especially complex pattern anomalies (e.g., anomalous subsequences, seasonalities, or trends), in the time domain remains a significant challenge.

Identify and highlight the anomalies within the time-domain data in red. Subsequently, apply a Fourier Transform to convert the time series into the frequency domain. Partition the resulting frequency-domain data into five distinct frequency bands. The objective is to then analyze these bands separately to determine how different types of time-domain anomalies manifest as deviations within specific frequency bands. For clear visualization, the frequency bands that are identified as anomalous will be filled with red.

To better detect such complex patterns, shifting the analysis to the frequency domain is a promising direction. The Fourier Transform10, for instance, provides a powerful mechanism for this, as it can reveal underlying periodicities and structures often obscured in the time domain. Our key observation, illustrated in Fig. 1, is that different anomaly types manifest their impact in distinct spectral regions. Specifically, we partitioned the spectrum into five geometrically spaced bands and found that seasonality anomalies predominantly affect the mid-frequency range; subsequence anomalies impact the low- and high-frequency ranges; and trend anomalies influence the low- to mid-frequency range, often accompanied by a reduction in the spectral peak. This discovery suggests that a frequency-band-specific analysis could be highly effective.

This chart visually demonstrates how different types of anomalies in a time series exhibit unique signatures in both the time and frequency domains. In the top time-domain plot, we can clearly see a normal periodic signal contrasted with an anomalous signal that contains distinct issues: a sudden spike, a missing seasonal peak, and a segment of high-frequency oscillation. The bottom frequency-domain plot reveals how these anomalies appear after a Fourier Transform. Notably, the spike and the high-frequency oscillation introduce significant energy across the high-frequency spectrum (highlighted in red), creating a stark contrast with the normal signal, whose energy is neatly concentrated at a few low-frequency peaks.

However, a naive, coarse-grained spectral analysis is insufficient. When such an approach is used, we find that information indicative of anomalies tends to concentrate in the low- to mid-frequency bands, risking the oversight of critical high-frequency anomalies (as shown by comparing the coarse spectrum in Fig. 1 to the fine-grained one in Fig. 2). This issue is further compounded by the fact that different anomalous behaviors are intricately interwoven even within a single channel, leading to interference in the detection results11. This necessitates a more sophisticated approach that goes beyond simple spectral analysis and delves into the complex“Frequency-Amplitude relationships”of the frequency-domain data, motivating the core design of our proposed method.

This figure uses heatmaps to intuitively visualize three core relationship patterns among channels (which can be thought of as different sensors or variables) in multivariate time series data. The“Channel Independence”plot on the left shows a scenario where there is almost no correlation between any of the channels (dark colors), except for each channel’s perfect correlation with itself (the bright diagonal). The“Channel Dependence”plot in the middle represents the opposite extreme, where all channels are strongly correlated with each other, making the entire map bright yellow-green. Finally, the“Channel Clustering”plot on the right reveals a more complex and common structure: the channels form distinct clusters where channels within a group are highly correlated (bright squares), but the groups themselves are independent of one another (dark areas).

A central challenge in multivariate time series anomaly detection lies in modeling the complex inter-channel dependencies. Previous research has extensively explored various channel-handling strategies, which can be broadly categorized into three families (Fig. 3). CI approaches treat each channel in isolation, disregarding their interactions12. In stark contrast, CD methods assume a fully connected graph of dependencies, modeling all channels jointly13. Occupying a middle ground, Channel-Clustering (CC) techniques first group similar channels and then apply distinct models to each cluster14. However, each of these strategies grapples with a fundamental trade-off. The CI approach, while robust to noise, pays the high price of ignoring valuable cross-channel information, which severely hampers its modeling capacity and generalization to new channel configurations15. Conversely, the all-encompassing CD strategy is highly susceptible to contamination from noisy or spurious correlations, compromising its robustness16. Even the hybrid CC approach falls short, as its static, pre-defined clustering is too rigid to capture dynamic inter-cluster relationships, limiting its flexibility and general applicability17. Ultimately, these methods are constrained by a rigid, pre-determined assumption about the channel correlation structure, highlighting the need for a more adaptive and data-driven approach.

To address the inherent limitations of conventional approaches, we introduce the Frequency Filtering Time Series Transformer (FreFilterTST), a framework engineered with a sophisticated pipeline for fine-grained spectral analysis. To counteract the coarse-grained nature of traditional frequency analysis that often misses critical details, our core innovation, termed“Frequency Patching”, segments the full spectrum into localized fragments. Theoretically, this patching mechanism can be proven to enforce spectral locality by design and contain the influence of noise within local patches, thereby mitigating interference across the spectrum (a formal analysis is provided in Supplementary Information). This enables the model to capture subtle, high-frequency anomalies by processing rich embeddings derived from both real and imaginary components. This representation serves as the input to our central FreFilter module, which is specifically designed to transcend the rigid, assumption-laden nature of traditional CI, CD, and CC approaches. It leverages a MoE architecture governed by a dynamic router, a paradigm proven effective in complex tasks like federated video anomaly detection for fusing expert knowledge18. Instead of adhering to a static assumption of full channel dependence or independence, this router adaptively prunes spurious or redundant spectral dependencies in real-time. This dynamic filtering mechanism compels the model to focus only on the most salient frequency-amplitude relationships. By modeling these filtered dependencies, FreFilterTST robustly discovers latent inter-channel correlations within specific spectral bands, achieving a superior balance between modeling capacity and noise resilience that is inaccessible to coarser or more rigid methods.

The main contributions can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

We propose FreFilterTST, a novel anomaly detection framework based on time-frequency reconstruction. This framework enhances the saliency of anomalous features by transforming time series into the frequency domain. Furthermore, it leverages a frequency patch reconstruction method to mitigate the impact of noise from the temporal context.

-

2.

By integrating a channel-expert filter using a MoE architecture with a cross-channel attention mechanism, FreFilterTST adaptively selects and models the most critical Frequency-Amplitude dependencies across channels, enabling precise localization and characterization of anomalies.

-

3.

Extensive experimental evaluations on six widely-used benchmark datasets demonstrate that FreFilterTST achieves superior performance compared to state-of-the-art anomaly detection frameworks.

Related work

Anomaly detection is a broad and active field of research with diverse applications across various data modalities. While our work focuses on unsupervised anomaly detection in multivariate time series, significant progress has also been made in other areas, such as weakly-supervised video anomaly detection where methods leverage semantic consistency to identify abnormal events19. In the following, we will review the literature most relevant to our specific task.

Multivariate time series anomaly detection

A foundational premise in anomaly detection is that normal data exhibits consistent, predictable patterns, while anomalies deviate from this norm; consequently, prevailing techniques aim to learn a model of normative behavior and use prediction or reconstruction errors as an anomaly score. Historically, this field was dominated by classical machine learning methods8, which, despite their utility, often struggled to capture the complex, non-linear dependencies inherent in high-dimensional time series. This limitation spurred a paradigm shift towards deep learning20, which offers powerful tools for modeling such intricate relationships. Prominent deep learning approaches include graph-based models like the Graph Deviation Network (GDN)21, which learns an explicit inter-variable topology, and Transformer-based methods22, which capture long-range dependencies through self-attention.Recent efforts have further sophisticated these architectures,Recent advancements have further pushed the state-of-the-art, with models like CAT-GNN23 integrating graph neural networks for explicit structural modeling, and DSFormer24 employing a dual-stream architecture to decouple dependencies, both achieving strong performance on benchmark datasets. Beyond these architectures, researchers are also exploring methods grounded in dynamical systems theory. For instance, approaches based on Koopman theory, such as COLLAR25, have shown significant promise for high-dimensional multivariate time series prediction by learning a linearized latent representation of the complex dynamics.However, even these state-of-the-art models are not without their own trade-offs. Graph-based methods often rely on a static dependency structure, while the all-to-all attention in standard Transformers can be susceptible to noise from irrelevant channels. A critical, unresolved challenge, therefore, is to develop a framework that can adaptively and dynamically discern salient dependencies, a gap our current work aims to address.

Frequency-domain approaches

The prospect of revealing subtle anomalies obscured in the time domain, such as those within periodic or oscillatory patterns, has made frequency-domain analysis a promising direction for enhancing detection performance. This inspired some of the first attempts to integrate both domains for MTSAD, most notably the Time-Frequency Analysis method (TFAD)26, which, however, was critically hampered by challenges in aligning time-frequency granularity. A more recent breakthrough, the Dual-TF method27, made substantial progress on this alignment issue, yet its effectiveness remains constrained by its reliance on a generic Transformer backbone rather than a purpose-built architecture. More fundamentally, both TFAD and Dual-TF are constrained by deeper, shared limitations. First, their frequency modeling approach is inherently biased towards low-frequency components, leading to the systematic neglect of critical high-frequency information where transient anomalies often reside. Second, their exploration and utilization of the complex web of inter-channel correlations remain insufficient. Ultimately, these unresolved issues highlight a clear and significant gap in the existing literature: the need for a unified framework that can perform both fine-grained, full-spectrum analysis and adaptive, robust modeling of inter-channel dependencies, a challenge our work is expressly designed to address.

Inter-channel dependency modeling

A central challenge in multivariate time series anomaly detection lies in effectively modeling the complex inter-channel dependencies. This challenge of characterizing dynamic, and often noisy, relationships between entities is not unique to time series analysis. It shares conceptual parallels with challenges in other fields, such as wireless communications, where researchers develop sophisticated fading models to characterize the time-varying nature of communication channels amidst interference and noise28. This cross-domain parallel underscores the fundamental importance of developing adaptive and robust methods to learn inter-variable structures from data. Existing approaches span a spectrum of strategies, each with inherent limitations. At one end, CI methods, employed by prominent works like DiffiTSF1 and PatchTST11, process each channel in isolation. While this design offers a degree of robustness, it comes at the significant cost of disregarding valuable cross-channel interactions, thereby limiting model capacity and generalization to unseen channel configurations. Quantitatively, this approach has a low computational complexity, scaling linearly with the number of channels O(N), but it fundamentally ignores all \(N(N-1)/2\) potential cross-channel relationships. At the other extreme, CD approaches attempt to capture the full scope of these interactions. For instance, MSCRED29 reconstructs correlation matrices using a Conv-LSTM, while the innovative iTransformer13 inverts the roles of time and variables to model global dependencies. However, by indiscriminately integrating all relationships, these methods become highly susceptible to contamination from noisy or spurious correlations, which ultimately compromises their robustness. This provides maximum modeling capacity but incurs a significant computational cost, typically scaling quadratically with the number of channels \(O(N^{2})\) due to all-to-all attention mechanisms or correlation matrix computations. Hybrid strategies like CC30 offer a compromise by forming static groups, yet this rigid, pre-defined partitioning is incapable of capturing dynamically evolving interactions. This reduces complexity from \(O(N^{2})\) to a sum over smaller clusters (\(\Sigma O\left( k_{i}^{2}\right)\), where \(k_{i}\) is the size of cluster i), balancing modeling capacity and efficiency. In essence, the entire spectrum of existing methods is constrained by a rigid, pre-determined assumption about the channel correlation structure-be it complete independence, full dependency, or static grouping and always make Complicating calculations. Therefore, developing a dependency modeling approach that can adaptively discern and leverage the most salient inter-channel relationships, while pruning redundant ones, remains a significant and open challenge.

Methods

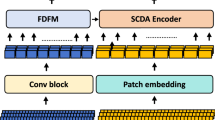

In the task of MTSAD, the input multivariate time series is formally defined as:\(X=\left\{ x^{1},x^{2},...,x^{T}\right\} \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times T}\), where T represents the total length of the time series and N is the number of channels. Our primary objective is to learn a model in an unsupervised setting that can effectively capture anomalous patterns of behavior within the data.The complete architecture of this framework is depicted in Fig. 4.

The RevIN (Reversible Instance Normalization) layer31 is first employed to mitigate the distribution shift between the training and testing sets, which often arises from varying statistical properties in time series data. This, in turn, enhances the model’s generalization performance during the reconstruction of test data.Next, we transform the time series into the frequency domain. Specifically, this is achieved using the efficient Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithm9, which decomposes the series into a sum of orthogonal sinusoidal signals. Following this transformation, a patching layer is applied to enable fine-grained modeling of the spectrum. The entire frequency sequence of length T is partitioned into n non-overlapping patches, each of length p, such that \(T=p\times n\). Throughout this process, we retain both the real part \(P^{R}\)and the imaginary part \(P^{I}\)of the FFT-transformed signal. This is crucial for preserving the complete information of the original signal, as these two components respectively encode its magnitude and phase. The precise formulation is given in Equations (1) and (2).

where \(P^{R(n)}\) and \(P^{I(n)}\) represent the \(\underline{n}\) patches of the real and imaginary components, \(P^{R}\) and \(P^{I}\), respectively. \(P^{R(n)}\in \mathbb {R}^{N \times p},P^{I(n)}\in \mathbb {R}^{N \times p}\).

After concatenating the real and imaginary parts, each resulting patch \(P^{n}\) has a dimension of \(\mathbb {R}^{N \times 2p}\). This sequence of patches, \(\left\{ P^{1}, P^{2}, ..., P^{n}\right\}\), is then fed into a projection layer. This layer, composed of a linear transformation followed by a GELU activation function, maps the patches from their raw frequency representation into a higher-dimensional embedding space. The output is a sequence of projected features \(P^{*} = \left\{ (P^{*})^{1}, (P^{*})^{2},..., (P^{*})^{n}\right\}\), where each patch embedding \((P^{*})^{n}\) has a dimension of \(\mathbb {R}^{N \times d}\). While these embeddings provide a rich, fine-grained representation of the spectrum, they also present a critical challenge: how to effectively model the intricate and often noisy web of inter-channel dependencies that exists within each localized spectral band. A naive all-to-all attention mechanism would be susceptible to spurious correlations, undermining the very goal of fine-grained analysis.

To tackle this challenge, we introduce our core FreFilter module. the sequence of patch embeddings \(P^{*}\) is fed into this core module. This module is designed to dynamically model inter-channel correlations by employing a novel MoE mechanism:

This module dynamically models the inter-channel correlations within each fine-grained band. The output for the n patch is a tensor \(F((P^{*})^{n})\in \mathbb {R}^{N \times d}\), which we denote as \(O = \left\{ O^{1}, O^{2}, ..., O^{n}\right\}\) and where N is the number of channels and d is the hidden dimension of the attention mechanism. The FreFilter module processes the entire sequence of frequency patches in parallel.

Subsequently, the refined embeddings O are passed to the Time-Frequency Reconstruction (TFR) module. The purpose of this module is to reconstruct the spectral components and, subsequently, the time-domain signal:

Here, \(X^{'}\) represents the reconstruction in the time domain, while \(P^{'R}\)and \(P^{'I}\) are the corresponding reconstructions in the frequency domain. The overall processing pipeline of our method is illustrated in Fig. 5.

FreFilter

The Frequency Filter (FreFilter) module is the core of our model, designed to dynamically learn and prune inter-channel dependencies in the frequency domain. It consists of two main components: a FCF and a CT. The FCF module first generates a sparse, structured attention mask, which then guides the attention computation within the CT module to focus on the most salient channel correlations.

The FCF module operates in a two-stage process to generate the final attention mask: (1) Graph Construction and Initial Pruning, and (2) MoE-based Dynamic Sparsification.

First, we model the relationships between channels as a graph. We construct a dense adjacency matrix, Adj, by computing the inner product similarity between the high-dimensional embeddings \(P^{*}\)of all channel pairs.

To distill the essential dependency structure from the dense adjacency matrix, Adj, we employ a two-stage sparsification strategy.

where \(\odot\) is the Hadamard product, and TopK(Adj, k) is a binary mask retaining only the k largest values per row in Adj. The parameter k controls the initial sparsity. In the TopK(Adj, k) mask, for each row, only the entries corresponding to the k largest values are set to 1, while all others are set to 0. The parameter k is typically determined by\(k = \lfloor \alpha \cdot N\rfloor\), where \(\alpha \in (0, 1]\) is a hyperparameter controlling the sparsity of the graph

In parallel, we generate a dynamic graph,using a MoE mechanism. This process begins by defining a set of pre-defined expert masks, \(\left\{ M_{e}\right\}\) for e=1...E, where each \(M_{e} \in \left\{ 0,1\right\} ^{N \times N}\) represents a fundamental connectivity pattern.

To dynamically combine these patterns, we introduce our concepts of Relational Amplitude and Relational Frequency to guide a gating network \(g^{\theta }\)(see Algorithm 1 in the Appendix for a detailed procedure). These meta-properties are derived not from the raw signal, but from the structural topology of the static graph \(Adj_{k}\). We frame them within the context of information flow dynamics:

Relational Amplitude quantifies a channel’s capacity as an information source or sink within the network. A channel with high Relational Amplitude (proxied by its high aggregate connectivity strength) is a“loudspeaker”in the system, capable of broadcasting information widely or receiving from many sources. Its influence is isotropic, spreading in all directions.

Relational Frequency quantifies the nature of the information a channel processes. We draw an analogy from physics: low-frequency signals tend to represent stable, slowly-changing base components, while high-frequency signals represent rapid, detailed fluctuations. Here, a channel with a stable, predictable connection profile (low standard deviation of connection strengths) is considered to be processing“low-frequency”structural information-its own fundamental, internal dynamics. Conversely, an erratic connection profile (high standard deviation) suggests it is processing “high-frequency”structural information-reacting to complex, specific interactions with a select few neighbors.

The gating network \(g^{\theta }\) takes a 2-dimensional feature vector (sum, stddev) for each channel and outputs routing weights \(G \in \mathbb {R}^{(B \times N \times E)}\) after a noisy gating function. Let \(v_{gate}\) be the tensor of shape (B, N,2) containing these features:

The element \(G^{(b,i,e)}= 1\)indicates that for the i-th node in the b sample, the e-th expert is activated; otherwise, \(G^{(b,i,e)} = 0\).

Next, the dynamic attention mask, which we denote as M, is generated. This is achieved by taking a weighted sum of the pre-defined, fixed expert masks \({M_{e}}\). The gating output \(G^{(b,i,e)}\) serves as the weight for each expert mask, calculated based on the source node i’s profile. This creates a dynamic graph where the connectivity from each node is influenced by its identified structural role:

For our model with E=2 experts, the expert masks \(\left\{ M_{A}, M_{F}\right\}\) are designed to be the canonical graph representations corresponding to these two modes of information flow. They are not meant to capture all possible dependency patterns, but to represent the two fundamental extremes of information processing:

Amplitude Expert Mask \((M_{A})\): This is a fully-connected graph. This structure is the natural and only representation of perfectly isotropic information flow. It embodies the principle that a channel acting as a pure information source/sink (maximum Relational Amplitude) should have an unimpeded, non-preferential pathway to all other nodes.

Frequency Expert Mask\((M_{F})\): This is an identity matrix. This structure is the canonical representation of a system focused purely on“frequency”internal information. It models a channel that is perfectly stable and decoupled from external high-frequency fluctuations, focusing exclusively on its own intrinsic dynamics.

Our central hypothesis is that any complex inter-channel dependency can be effectively approximated as a linear combination of these two extreme, orthogonal modes of information processing. The gating network \(g^{\theta }\) does not simply choose between two patterns; it learns a continuous, channel-specific weight G that determines how much a channel behaves like a“broadcaster”versus a “self-regulator”in any given context. By mixing these two canonical masks, our model can construct a vast and nuanced space of dynamic graphs, effectively capturing the rich spectrum of dependencies from two simple, interpretable primitives. This design choice favors principled decomposition over empirical pattern-matching.

Then it will ouput an attention mask, denoted as \(A_{mask}\), which is designed to guide the subsequent CT module. This mask is computed by the element-wise product of the KNN-filtered adjacency matrix and the dynamic sparse attention mask M, augmented with self-connections (represented by an identity matrix, I).

The final outputs of the FCF module are twofold: (1) a highly sparse and structured attention mask, denoted as \(A_{mask}\), and (2) a regularization loss, termed \(L_{moe}\). This mask is subsequently passed to the downstream CT module, where it is directly applied to modulate the self-attention computation. The role and formulation of \(L_{moe}\) will be elaborated in the upcoming section on the loss function.

The CT is the second component of our FreFilter module. Its primary objective is to model the frequency-channel correlations, with its attention mechanism being strictly guided by the sparse mask generated by the FCF. Unlike standard self-attention which operates over the time dimension, our CT employs a cross-channel attention mechanism that operates along the channel dimension (N) of the input feature maps.

Each layer in the CT module is composed of two main sub-layers: a masked multi-head cross-channel attention mechanism, and a position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN).

The attention mechanism receives two inputs: the sequence of frequency patch embeddings \(P^{*}\) (with shape B, N, d) and the attention mask \(A_{mask}\)(with shape B, N, N) from the FCF.

First, the input \(P^{*}\) is linearly projected into Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) matrices using learnable weight matrices \(W^{Q}, W^{K}, W^{V} \in \mathbb {R}^{(d \times d)}\). These are then split into H attention heads.

The attention scores are then computed by taking the scaled dot-product of Q and K. Note that this operation is performed across the channel dimension (N), resulting in an attention map of shape (B, H, N, N):

where \(d_{k} = d / H\) is the dimension of each attention head.

The key innovation lies in the application of the \(A_{mask}\). We use it to modulate the raw attention scores before the Softmax activation, effectively pruning connections with a value of 0 in the mask by setting their scores to negative infinity:

Here, \(\odot\) is the Hadamard product, 1 is an all-ones matrix, and C is a large positive number (practically, the maximum machine float value).This operation ensures that for any connection where the value in the \(A_{mask}\) is 0, the corresponding attention score becomes a large negative value. Consequently, in the subsequent Softmax computation, the attention weight for this connection approaches zero, effectively pruning it from the graph.

Finally, the attention weights \(\alpha\) are computed and used to aggregate the V matrices. The outputs of all heads are concatenated and passed through a final linear projection \(W^{O}\).

Following the attention sub-layer, the output O is passed through a position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN). Each layer in our Channel Transformer applies residual connections and Layer Normalization (LayerNorm) around each of the two sub-layers:

The final output of the entire multi-layered Channel Transformer is a refined frequency-domain feature representation, which is then passed to the downstream reconstruction module.

Spectrum reconstruction

The final stage of our model is the TFR module, which aims to reconstruct the original time-domain signal from the refined frequency-domain features. The discrepancy between the original and reconstructed signals then serves as the basis for our reconstruction loss. The TFR module takes the final feature representation \(O^{final}\)(with shape B, N, d) from the Channel Transformer as input. It consists of two main parts: a projection head and an Inverse FFT (iFFT) layer.

First, the sequence of patch embeddings in \(O^{final}\) is flattened along the patch dimension (B which is \(batch_{size} \times n\)). Then a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) acts as a projection head. This MLP maps the high-dimensional features back to the required frequency-domain representation,predicting the real and imaginary components for all patches. The output of the MLP is reshaped to form the reconstructed real and imaginary spectra,\(P^{'R }\)and \(P^{'I}\), both with the original spectral shape.

The reconstruction loss serves as the primary driving force for training our model. Its objective is to minimize the discrepancy between the original input time series, X, and its reconstructed counterpart,\(X^{'}\), which is obtained by passing the input through the entire pipeline (i.e., FFT, encoder, decoder, and iFFT). We employ the Mean Squared Error (MSE) to quantify this discrepancy, which is formulated as follows:

Loss function

To effectively train the model, we have designed a composite loss function, \(L_{total}\), that balances reconstruction fidelity with regularization of the MoE module. The overall optimization objective is a weighted sum of two key components: the reconstruction loss \(L_{rec}\)and the MoE regularization loss \(L_{moe}\).

where \(\lambda _{moe}\)is a hyperparameter that controls the strength of the MoE regularization. Having detailed \(L_{rec}\) in the previous section, we now focus on \(L_{moe}\).

The MoE loss \(L_{moe}\) itself consists of two terms, designed to promote balanced and non-deterministic expert utilization: an importance loss \(L_{imp}\) and a dynamic entropy loss \(L_{dyn}\).

o prevent model degradation, where the gating network consistently favors a small subset of experts, we introduce an importance loss, \(L_{imp}\)32, to encourage a balanced load across all experts. The load Le for an expert e is the total number of times it is selected by the gating network across all B patches and L channels in the batch. Based on our binary gating output \(G \in \left\{ 0, 1\right\} ^{(B \times L \times E)}\), the load is calculated as:

The importance loss then quantifies the imbalance of these loads using the squared Coefficient of Variation (\(CV^{2}\)):

where L = [\(L_{1}, L_{2}, ..., L_{e}\)], Var(\(\cdot\)) and Mean(\(\cdot\)) compute the variance and mean respectively, and \(\Phi\)is a small constant for numerical stability.

To encourage exploration during training and prevent the gating network from converging prematurely to a deterministic state, we apply an entropy regularization loss, \(L_{dyn}\)33. This loss is applied to the probability distribution output by the gating network \(g^{\theta }\) just before the NoisyTopGating function. Let \(p^{(b,i,e)}\) be the probability vector over the \(\underline{E}\) experts for the i channel in the b patch. The loss is the negative entropy of this distribution, averaged over the batch:

This loss encourages the probability distributions to be smoother, preventing the gating decisions from becoming overly peaked. \(L_{dyn}\) in Equation (21) is a hyperparameter balancing the two MoE loss terms.

Anomaly score

The core principle of anomaly detection within our framework is to quantify the degree of abnormality for a given input data point.The FreFilterTST model leverages its ability to learn the patterns of normal data to identify anomalies. It achieves this by evaluating the reconstruction fidelity of new, incoming data points. Our scoring mechanism performs a comprehensive evaluation in both the time and frequency domains. This dual-domain approach enables the model to capture a more diverse range of anomaly patterns that might be subtle or invisible in a single domain.

Our final anomaly score is a weighted sum of the time-domain score and the frequency-domain score, balanced by a hyperparameter, \(\lambda\).

\(S_{temp}\) and \(S_{freq}\) are the reconstruction scores computed in the time domain and the frequency domain, respectively.

Time-Domain Score (\(S_{temp}\)). This score is designed to measure the direct discrepancy between the input and its reconstruction in the time domain. It is particularly sensitive to anomalies that manifest as abrupt changes in amplitude or distortions in signal shape. We compute Stemp as the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the original time series X and its reconstruction \(X^{'}\), averaged across the channel dimension.

Frequency-Domain Score (\(S_{freq}\)). To detect anomalies that are subtle in the time domain but manifest as significant deviations in periodicity or frequency components, we introduce the frequency-domain score. A typical example of such anomalies includes minor yet periodic high-frequency vibrations in industrial equipment, which are often overlooked by time-domain analysis alone.This process involves transforming both the original signal X and its reconstruction \(X^{'}\) into the frequency domain using the FFT. The objective is to then compare their respective spectral properties. To this end, we quantify the frequency-domain discrepancy by calculating the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) between their amplitude spectra.

A(f) and \(\widehat{A}(f)\) are the amplitudes of the original and reconstructed signals at frequency f, respectively.

Experiments

In this section, we conduct extensive experiments on six real-world datasets to comprehensively evaluate the performance of FreFilterTST. We provide a thorough overview of our experimental setup below. Our model is implemented using PyTorch and trained on a single NVIDIA RTX 4070 Ti SUPER GPU.

Baselines

We compare our proposed model, FreFilterTST, against a comprehensive set of 10 baseline methods, which include several recent and state-of-the-art (SOTA) models.Our baselines feature a range of state-of-the-art models, including the most recent ones from 2024 such as ModernTCN34 and DualTF27. We also compare against prominent models from 2023, namely DCdetector35, TimesNet36, PatchTST15, the linear models DLinear and NLinear37, TFAD26, and a standard AutoEncoder (AE)38. To provide a broader context, our comparison also incorporates classical non-learning techniques like Isolation Forest (IF)39, Principal Component Analysis (PCA)40, and Histogram-based Outlier Score (HBOS)41.

Datasets

We evaluate our model on six widely-recognized benchmark datasets for multivariate time series anomaly detection. These datasets span a diverse range of real-world application domains, including human mobility, Martian rover monitoring, urban traffic patterns, credit card fraud detection, and server monitoring.

Calit2: This dataset originates from a monitoring system at the main entrance of a building on the University of California, Irvine (UCI) campus. It captures two primary data streams: the flow of people entering and leaving the building. The data was collected over a span of more than 15 weeks and is aggregated into 30-minute intervals, resulting in 48 time steps per day.

MSL: This dataset consists of telemetry data collected from the Curiosity rover of the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission. The data provides a rich record of real-time status parameters from various subsystems and instruments aboard the rover. These parameters include, but are not limited to, temperature readings, power consumption levels, pressure levels, voltage values, and valve states (open/closed).

NYC: This dataset documents the operational data of taxi services in New York City. In the machine learning community, it is a popular benchmark for time series modeling, as it reflects the passenger demand (i.e., the number of rides) over specified time intervals. Specifically, the version used in our study records the number of taxi rides aggregated in 30-minute bins.

GECCO: Based on the 2017 GECCO industrial challenge an updated more advanced problem is provided. This year’s industrial partner again is TFW, which provides the real-world dataset used in this challenge. The goal of the GECCO 2018 Industrial Challenge is to develop an event detector to accurately predict any kinds of changes in a time series of drinking water composition data.

SEU: The SEU gearbox dataset, gathered from a Drivetrain Dynamics Simulator (DDS), was collected under two distinct operating conditions: 20Hz-0V and 30Hz-2V (speed-load). The dataset covers five conditions: one healthy state and four types of gear faults, which are chipped tooth, missing tooth, root crack, and wear. For each fault category, there are 1,000 training samples, and the test set is identical in size to the training set.

PSM: This dataset comprises multivariate time series data collected from the server clusters of a large internet company. It consists of performance metrics from multiple independent servers, which are also referred to as“entities”or“machines.”The core task associated with this dataset is unsupervised anomaly detection: the goal is to automatically identify patterns indicative of application failures, hardware issues, or service anomalies from a vast amount of normal server operational metrics. Consequently, the PSM dataset is widely used to evaluate anomaly detection algorithms capable of simultaneously processing multiple entities.

Main results

Our extensive experiments, summarized in Table 1, unequivocally demonstrate the superiority of FreFilterTST over all 10 baselines across six public datasets. The evaluation, conducted using Affiliation-based F1-Score (Aff-F1) and AUC-ROC, reveals a consistent and significant performance advantage. In terms of AUC-ROC, FreFilterTST achieves the highest scores on all datasets, validating its inherent capability to assign higher anomaly scores to true anomalies than to normal instances. FreFilterTST’s performance on the GECCO benchmark (0.966) gives it a decisive edge over strong competitors like ModernTCN (0.952) and PatchTST (0.957). This lead holds even on more difficult datasets such as MSL and PSM; while the margins are tighter, the model’s consistent first-place ranking underscores the fundamental soundness of its design. The model’s true strength, however, is most clearly demonstrated by the Aff-f1 metric on the NYC dataset. Here, its score of 0.994 creates a massive gap with the runner-up, DLinear (0.828). Such a disparity is not just a numerical victory; it points to a critical capability: a proficiency in identifying subtle, complex anomalies without being misled by normal background noise. This resolves a common pitfall where many other models falter, achieving a practical balance between precision and recall that competitors struggle to match. While its advantage over traditional methods like Isolation Forest is overwhelming, the clear and consistent performance gains against contemporary SOTA models like DualTF and DLinear ultimately validate the effectiveness of our innovations in model architecture, feature extraction, and loss function design.

These results collectively validate the advanced design philosophy and the practical effectiveness of the FreFilterTST model. It establishes a new state-of-the-art solution for the field of time series anomaly detection that is not only superior in performance but also robust and reliable.

Illustration of the static clustering baseline inspired by the Channel-Clustering Model (CCM). This approach represents an advanced static pruning strategy where a fixed dependency mask is learned. Instead of relying on a pre-defined metric, a Learnable Similarity Module is trained end-to-end to partition channels into optimal, fixed groups (e.g., Cluster 1, Cluster 2). The resulting Mask Matrix, which reflects this static partitioning, is then applied without modification throughout the entire anomaly detection process.

Ablation studies

We conduct a series of ablation studies on the Calit2, MSL, and GECCO datasets to verify the efficacy of the key components in our proposed FreFilterTST model. Our central innovation lies in a MoE architecture that dynamically models frequency-amplitude dependencies between channels. To evaluate this design, we compare FreFilterTST against five variants: 1) a model with only Expert A (w/o Expert F), 2) a model with only Expert F (w/o Expert A), 3) the model without \(L_{moe}\), 4) the model without \(L_{rec}\), and 5) a model,which our dynamic MoE module is replaced. by a static channel clustering mechanism inspired by recent advancements30. This baseline learns an optimal, fixed channel grouping for the task, and its static dependency structure is illustrated in Fig. 6.

Performance is evaluated using Aff-f and A-R metrics, where higher is better. The results, summarized in Table 2, highlight the competitive performance of FreFilterTST. Notably, on the GECCO dataset, FreFilterTST outperforms CC in terms of Aff-f (0.912 and 0.907) and achieves a nearly identical A-R score (0.966 and 0.970). On the remaining datasets, our model consistently ranks as the second-best, significantly surpassing both single-expert variants. This confirms that our MoE architecture effectively captures complex inter-channel dependencies, delivering performance on par with the more complex Channel-Clustering approach.

While the CC variant demonstrates strong performance, its practical application can be hindered by its inherent complexity and computational overhead. To further highlight the advantages of our FreFilterTST model, we conduct a comparative analysis of model efficiency against the best-performing CC variant. This comparison, detailed in Table 3, focuses on two key metrics: the total number of parameters and the computational cost.

FreFilterTST demonstrates profound efficiency, operating at a scale that is orders of magnitude smaller than its competitors without compromising performance. With a parameter count of just 2.8M to 7.24M, it is vastly more compact than models like CC, which require parameters in the hundreds of millions. This architectural economy translates directly into a minimal computational footprint. On the MSL dataset, a forward pass demands a mere 1.89 GFLOPs, starkly contrasting with the 46.78 GFLOPs required by the CC model. The advantage is even more pronounced on GECCO, where FreFilterTST’s computational cost (0.12 GFLOPs) is less than a tenth of CC’s (1.94 GFLOPs). This combination of a compact parameter space and low computational overhead establishes FreFilterTST not merely as an effective model, but as a highly practical solution poised for real-world deployment where resource constraints are a primary concern.

Furthermore, the ablation study on our two loss components reveals that our loss function design effectively contributes to the model’s overall performance.

Hyperparameter sensitivity

To comprehensively assess the robustness and stability of our proposed FreFilterTST model, we conduct a sensitivity analysis on two key hyperparameters: the Patch Size and the Batch Size. This analysis aims to investigate how the model’s performance varies under different hyperparameter settings, thereby providing reliable guidance for parameter tuning in practical applications and deployment. The experiments were performed on the Calit2, NYC, and GECCO datasets, with performance measured by Aff-f1 and AUC-ROC. The results are illustrated in Fig. 7.

This figure systematically illustrates the model’s performance sensitivity to two key hyperparameters, Batch Size and Patch Size, using a 2x2 grid of charts. Each row represents a hyperparameter (top row for Batch Size, bottom row for Patch Size), and each column represents a different performance metric (left column for ’a–ff’, right column for ’a-r’).

The model’s sensitivity to Patch Size varies across datasets. On GECCO, it demonstrates remarkable robustness, with both AUC-ROC and Aff-f1 scores showing negligible changes, suggesting a strong capability to handle diverse temporal scales. Similarly, performance on Calit2 is highly stable and largely insensitive to this parameter. In contrast, the NYC dataset exhibits some sensitivity, especially for the Aff-f1 metric. Performance peaks at a Patch Size of 16, dips at 32, and then recovers. This suggests that certain patch sizes may better align with the specific temporal structures within the NYC data. However, even at its lowest point (Patch Size=32), the Aff-f1 score remains high at approximately 0.77.

The model’s sensitivity to Batch Size largely mirrors its reaction to Patch Size. On both GECCO and Calit2, the model is highly robust to changes in Batch Size. For GECCO, performance is remarkably flat. For Calit2, while the Aff-f1 score degrades slightly with larger batch sizes, the overall performance remains stable and at a high level. The NYC dataset again proves to be more sensitive; the Aff-f1 score drops notably at a Batch Size of 32 and peaks at 64. This highlights the importance of proper Batch Size selection for this specific dataset. Nevertheless, excellent performance is still attainable with a well-chosen Batch Size, such as 16 or 64.

Visualization analyze

In Fig 8, we provides a detailed visualization of anomaly scores for five distinct types of anomalies-point (Global, Contextual) and subsequence (Seasonal, Trend, Shapelet) - using canonical samples. It clearly deconstructs the scoring mechanism of the method by separately displaying the time-domain anomaly score (green) and the frequency-domain score (orange). The visualization reveals that point anomalies are primarily captured by the time score, whereas subsequence anomalies, such as seasonal and trend variations, are more sensitively identified by the frequency score. Ultimately, these components are fused into a robust final score (blue) that accurately aligns with the ground truth anomalies (pink shaded areas) in all scenarios. This effectively demonstrates the method’s strength in leveraging both time and frequency perspectives for comprehensive and accurate anomaly detection.

Case study of a false negative on the Calit2 dataset. The top panel shows the raw sensor data, representing human traffic. The middle and bottom panels display the corresponding time-domain and frequency-domain anomaly scores from our model. The period around 2005-08-01, characterized by unusually low traffic, is a clear collective anomaly. While the scores show a noticeable dip, they do not rise to a level that would typically trigger an alert.

While Fig. 8 demonstrates the model’s proficiency in detecting various types of positive anomalies, a comprehensive evaluation also requires an analysis of its limitations, particularly in handling false negatives. To this end, we present a case study from the Calit2 dataset in Fig. 9, which reveals a challenging scenario for our model.The raw data in the top panel of Fig. 9 represents human traffic flow, exhibiting strong daily and weekly periodicities. Around the date 2005-08-01, the traffic drops to near-zero levels for an extended period, which constitutes a significant collective anomaly-an unusual absence of the expected signal. As shown in the middle and bottom panels, both the time-domain and frequency-domain scores react to this event, exhibiting a sharp dip. This dip correctly indicates a deviation from the learned normative patterns.However, a key limitation is revealed here: our reconstruction-based scoring mechanism primarily flags anomalies by a high reconstruction error. In this“absence-of-signal”scenario, reconstructing a near-zero signal is relatively easy for the model, resulting in a low reconstruction error and thus a low anomaly score. While the pronounced dip is visually apparent to a human observer, it does not translate into a high peak that would cross a typical anomaly threshold. This highlights a limitation of our current framework in robustly identifying anomalies characterized by the unexpected absence of patterns, a common challenge for many reconstruction-based methods. Future work could explore incorporating predictive components or alternative scoring functions to better address such collective negative anomalies.

To further deconstruct our model’s dual-domain detection mechanism, particularly its claimed ability to capture high-frequency anomalies, we conducted a controlled experiment on a semi-synthetic dataset. As illustrated in Fig. 10. The bottom panel shows that the time-domain score almost exclusively captures the large-amplitude Spike, while the frequency-domain score is uniquely sensitive to the High-Frequency Burst, an anomaly nearly invisible in the time domain. This experiment provides unequivocal evidence that our fine-grained frequency analysis via“Frequency Patching”is essential for identifying spectrally distinct anomalies, showcasing the critical synergy between the two scoring domains.

In Fig. 11 illustrates the dependency structures learned by our model on the frequency-domain representations of three datasets, revealing its powerful capability to capture diverse spectral characteristics. After applying a Fourier Transform to the time-series data, the model operates on the amplitudes of the resulting spectral components. For the Calit2 dataset, the model learns a complex inter-frequency coupling pattern, evidenced by significant off-diagonal dependencies. This indicates that activities of different periodicities are not independent but are strongly linked through harmonic relationships or modulation effects, which aligns with the real-world phenomenon where long-term patterns influence short-term behaviors. In contrast, for the NYC dataset, the model learns an extremely sparse diagonal structure, implying that its spectral components are highly decoupled. The dominant frequencies operate independently without mutual interference, reflecting the highly stable and predictable nature of its periodicities. The GECCO dataset presents an intermediate case with a broader diagonal, suggesting that dependencies are concentrated among adjacent frequency components, likely due to spectral energy leakage caused by non-stationary periodicities in the data. In summary, these results compellingly demonstrate that our model can go beyond temporal dependencies to operate effectively in the frequency domain, adaptively modeling complex spectral relationships ranging from highly coupled to fully decoupled.

In conclusion, the visualization results provide compelling evidence for the effectiveness of our proposed model. The model demonstrates a robust ability not only to accurately learn the complex, cyclical patterns of normal behavior in the time series but also to detect anomalous events in a timely manner with both high recall and high precision. The strong correlation between the anomaly score curve and the ground-truth labels, coupled with the inherent interpretability of the scores, further validates our approach.While some minor anomalies were missed, this is primarily an issue of threshold setting rather than a fundamental flaw in the model’s discriminative power. This limitation can be addressed by optimizing the threshold or by introducing a dynamic thresholding strategy, which constitutes a promising direction for our future research.

Analysis of expert utilization

To evaluate the practical behavior of our MoE mechanism and demonstrate its ability to achieve a balanced load, we analyzed the expert utilization post-training. We collected the gating weights assigned to the \(M_{A}\) and the \(M_{F}\) on three distinct datasets, with the results visualized in Fig. 12.

(a) In Calit2, the model heavily favors the Frequency Expert (0.72 utilization). This indicates that the dataset is dominated by strong, independent periodic patterns, where the model correctly learns to prioritize self-regulation and filter out potentially noisy cross-channel interactions. (b) In GeCCO, the experts are utilized in a highly balanced manner (0.442 for Amplitude and 0.558 for Frequency). This suggests a complex dataset with a mix of local spectral patterns and global events, where our model dynamically switches between both communication modes. (c) In NYC, the model shows a preference for the Amplitude Expert (0.552 utilization). This implies that inter-channel correlations are more prevalent in this dataset, and the model adaptively shifts its strategy to favor global information sharing.

Collectively, these findings provide powerful evidence that our MoE mechanism is functioning as intended. It successfully avoids expert collapse and, more importantly, implements a sophisticated, adaptive strategy that dynamically balances the trade-off between modeling capacity and noise resilience based on the learned characteristics of the input data.

Conclusion and future work

The experimental results presented in this study demonstrate that our model effectively mitigates the issues of over-attending to irrelevant channels and coarse-grained modeling, which are prevalent in traditional dependency modeling approaches. We have introduced FreFilterTST, a novel multivariate time series anomaly detection model built upon the Transformer architecture. This model is specifically designed to address the inherent noise in time series data by adaptively learning to select the most salient frequency-amplitude channel dependencies, while simultaneously modeling the locations of anomalies. Through its core innovations-Frequency Patch Reconstruction and a fine-grained, adaptive partitioning strategy-FreFilterTST refines previous coarse-grained channel modeling methods. Our extensive evaluations confirm that FreFilterTST outperforms existing excellent performance models on multiple public benchmark datasets. The primary contribution of this research is to show that the proposed strategies can significantly reduce attentional noise and enhance detection robustness, thereby laying a solid foundation for subsequent research. We hope these findings will contribute to a broader range of fields and inspire future work on hybrid methodologies.

Furthermore, our analyses of computational efficiency (Table 3) and hyperparameter sensitivity (Fig. 7) collectively underscore the strong practical scalability of FreFilterTST. The model’s lightweight architecture, combined with its stable performance across various parameter settings, establishes it not only as a high-performing but also as a robust and efficient solution ready for real-world deployment.

While FreFilterTST has demonstrated exceptional performance in multivariate time series anomaly detection, a complete analysis requires acknowledging its limitations and outlining future research trajectories. Specifically, our analysis identified a limitation in detecting anomalies characterized by signal absence due to its reconstruction-based nature. Future work could incorporate predictive mechanisms to better handle such scenarios. Beyond this, its generalization capabilities in univariate detection and mixed tasks remain to be further explored. We identify two broader challenges that constitute key avenues for future work.

Limitations and future research directions

Robustness to Non-Stationary Spectral Dynamics: The current framework’s reliance on the FFT assumes a degree of spectral stationarity within each analysis window. This can obscure transient, localized frequency events prevalent in systems with changing operational modes. To address this, a promising extension involves integrating multi-resolution analysis via Wavelet Transforms. This would enable the model to learn dependency structures that are specific not only to frequency bands but also to precise time intervals, enhancing robustness against complex domain shifts.

Scalability to Ultra-High-Dimensional Systems (N > 1000): While efficient, our MoE approach faces an computational bottleneck during the initial graph construction for systems with thousands of channels. Future work could overcome this by replacing the exact neighbor search with approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) algorithms to achieve sub-quadratic complexity. Alternatively, a hierarchical modeling strategy could group channels into super-nodes, applying FreFilterTST first within and then between clusters, thus decomposing the problem into more tractable parts.

Extending the MoE framework and enhancing interpretability

Another promising avenue for future research lies in extending the MoE framework beyond the current two-expert design. While scaling to E > 2 experts could theoretically enhance the model’s capacity to represent more complex dependency patterns, it also introduces significant challenges and potential failure modes that warrant careful investigation. Our analysis suggests that the primary obstacle is not merely technical but conceptual: designing additional expert masks that are both semantically meaningful and functionally orthogonal to the existing Amplitude and Frequency experts is a non-trivial task. A naive addition of experts could lead to functional redundancy, where multiple experts learn overlapping or highly correlated patterns, adding computational overhead without a proportional gain in performance. Furthermore, with a larger pool of experts, the model faces an increased risk of expert collapse-a failure mode where the gating network learns a degenerate strategy of routing all inputs to a single, overly general expert.

To this end, future research should focus on exploring principled approaches for designing and integrating a larger set of experts. This includes investigating methods for automatically discovering fundamental communication patterns from data, rather than relying on predefined masks, and developing more sophisticated regularization techniques to ensure balanced and diverse expert utilization. A thorough study of these potential failure modes is essential to enhance the reproducibility and successful extension of our adaptive filtering methodology. Finally, the“black-box”nature of models like FreFilterTST can limit their adoption in high-stakes scenarios. Therefore, a crucial future direction is to build an interpretability framework on top of FreFilterTST, integrating visualization techniques (such as attention map analysis) with established methods (like SHAP analysis) to enhance the model’s transparency.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are publicly available in the following repositories: The Calit2 Building People Counts dataset, available in the Calit2 repository: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/156/calit2+building+people+counts The Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) REMS data, available in the Planetary Data System (PDS): https://pds-atmospheres.nmsu.edu/data_and_services/atmospheres_data/Mars/Mars.html The NYC Taxi Trip data, available from NYC OpenData: https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Transportation/Taxi/mch6-rqy4/about_data The GECCO 2019 Industrial Challenge dataset, available from the TH Köln website: https://www.th-koeln.de/informatik-und-ingenieurwissenschaften/gecco-challenge-2019_63244.php The Southeast University (SEU) Gear Fault dataset, available on Figshare: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Gear_Fault_Data/6127874/1 The pooled server Metrics (PSM) dataset, available on GitHub: https://github.com/eBay/RANSynCoders/tree/main/data.

References

Yang, S. et al. DiffTST: Diff transformer for multivariate time series forecast. IEEE Access 13, 73671–73679. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3563070 (2025).

Huang, Y. et al. FreqWave-TranDuD: A multivariate time series anomaly detection method based on wavelet and Fourier transforms. IEEE Access 13, 68384–68397. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3557571 (2025).

Akour, I., Mohamed, N. & Salloum, S. Hybrid CNN-LSTM with attention mechanism for robust credit card fraud detection. IEEE Access 13, 114056–114068. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3583253 (2025).

Peng, C. et al. Real-time human action anomaly detection through two-stream spatial-temporal networks. IEEE Access 13, 66774–66786. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3560703 (2025).

Djuric, N., Kljajic, D., Pasquino, N., Otasevic, V. & Djuric, S. A framework for RF-EMF time series analysis through multi-scale time averaging. IEEE Access 13, 84811–84825. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3569304 (2025).

Tian, C. & Zhang, F. Self-supervised ECG anomaly detection based on time-frequency specific waveform mask feature fusion. IEEE Access 13, 97585–97596. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3572484 (2025).

Xu, G., Zhang, Q., Song, Z. & Ai, B. Relay-assisted deep space optical communication system over coronal fading channels. IEEE Transactions on Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 59, 8297–8312. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAES.2023.3301463 (2023).

Breunig, M. M., Kriegel, H.-P., Ng, R. T. & Sander, J. LOF: Identifying density-based local outliers. In Proceedings of the 2000 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Vol. 29. 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1145/342009.335388 (ACM, 2000).

Lai, K.-H. et al. Revisiting time series outlier detection: Definitions and benchmarks. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 34 (eds Ranzato, M. et al.) 24889–24900 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2021).

Brigham, E. O. & Morrow, R. E. The fast Fourier transform. IEEE Spectrum 4, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSPEC.1967.5217220 (1967).

Wang, H. et al. FreDF: Learning to forecast in the frequency domain. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2025).

Nie, Y., Nguyen, N. H., Sinthong, P. & Kalagnanam, J. A time series is worth 64 words: Long-term forecasting with transformers. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. iTransformer: Inverted transformers are effective for time series forecasting. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2024).

Qiu, X. et al. DUET: Dual Clustering Enhanced Multivariate Time Series Forecasting. in Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD '25), Vol. 1. 1185–1196. https://doi.org/10.1145/3690624.3709325.

Qiu, X. et al. A comprehensive survey of deep learning for multivariate time series forecasting: A channel strategy perspective 2502. 10721 (2025).

Han, L., Ye, H.-J. & Zhan, D.-C. The capacity and robustness trade-off: Revisiting the channel independent strategy for multivariate time series forecasting. IEEE Transactions on Knowl. Data Eng. 36, 7129–7142. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2024.3359642 (2024).

Yu, Y., Jing, G., Hong, J., Rodríguez-Piñeiro, J. & Yin, X. A novel wireless channel clustering algorithm based on robust mean-shift. IEEE Transactions on Wirel. Commun. 24, 5213–5226. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2025.3546457 (2025).

Su, Y., Li, J., An, S., Xing, M. & Feng, Z. Federated weakly-supervised video anomaly detection with mixture of local-to-global experts. Inf. Fusion 123, 103256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103256 (2025).

Su, Y., Tan, Y., An, S., Xing, M. & Feng, Z. Semantic-driven dual consistency learning for weakly supervised video anomaly detection. Pattern Recognit. 157, 110898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2024.110898 (2025).

Liu, Q. & Paparrizos, J. The elephant in the room: Towards a reliable time-series anomaly detection benchmark. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 37. 108231–108261 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2024).

Deng, A. & Hooi, B. Graph neural network-based anomaly detection in multivariate time series. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 35, 4027–4035. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v35i5.16534 (2021) (AAAI Press).

Xu, J., Wu, H., Wang, J. & Long, M. Anomaly Transformer: Time series anomaly detection with association discrepancy. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2022).

Duan, Y. et al. CaT-GNN: Enhancing credit card fraud detection via causal temporal graph neural networks (2024). 2402.14708.

Ju, Z. et al. DSFormer: Dynamic size attention with enhanced long-range dependency modeling for artery/vein classification. Knowledge-Based Syst. 329, 114359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2025.114359 (2025).

Peng, Q., An, S., Nie, S. & Su, Y. COLLAR: Combating low-rank temporal latent representation for high-dimensional multivariate time series prediction using dynamic Koopman regularization. J. Big Data 12, 258. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-025-01299-z (2025).

Zhang, C., Zhou, T., Wen, Q. & Sun, L. TFAD: A decomposition time series anomaly detection architecture with time-frequency analysis. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management (CIKM '22) 2497–2507. https://doi.org/10.1145/3511808.3557470 (ACM, 2022).

Nam, Y. et al. Breaking the time-frequency granularity discrepancy in time-series anomaly detection. In Proceedings of The Web Conference 4204–4215, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1145/3589334.3645677 (2024) (ACM).

Wang, H. et al. The \(\lambda\)-\(\kappa\)-\(\mu\) fading distribution. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 23, 4398–4402. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2024.3449112 (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. A deep neural network for unsupervised anomaly detection and diagnosis in multivariate time series data. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 33, 1409–1416. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33011409 (2019) (AAAI Press).

Chen, J., Lenssen, J. E., Feng, A., Hu, W., Fey, M., Tassiulas, L., Leskovec, J. & Ying, R. From similarity to superiority: Channel clustering for time series forecasting. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 37. 130635–130663. https://doi.org/10.52202/079017-4152 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2024).

Kim, T. et al. Reversible instance normalization for accurate time-series forecasting against distribution shift. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2021).

Huang, Q. et al. Harder Task Needs More Experts: Dynamic Routing in MoE Models. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Vol. 1: Long Papers, 12883–12895. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.acl-long.696 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024).

Shazeer, N. et al. Outrageously large neural networks: The sparsely-gated mixture-of-experts layer. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2017).

Luo, D. & Wang, X. ModernTCN: A modern pure convolution structure for general time series analysis. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2024).

Yang, Y., Zhang, C., Zhou, T., Wen, Q. & Sun, L. DCDetector: Dual-attention contrastive representation learning for time series anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 3033–3045. https://doi.org/10.1145/3580305.3599295 (ACM, 2023).

Wu, H. et al. TimesNet: Temporal 2D-variation modeling for general time series analysis. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2023).

Zeng, A., Chen, M., Zhang, L. & Xu, Q. Are transformers effective for time series forecasting?. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 37, 11121–11128. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v37i9.26273 (2023) (AAAI Press).

Sakurada, M. & Yairi, T. Anomaly detection using autoencoders with nonlinear dimensionality reduction. in Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Machine Learning for Sensory Data Analysis (MLSDA '14) 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1145/2689746.2689747 (ACM, 2014).

Liu, F. T., Ting, K. M. & Zhou, Z.-H. Isolation forest. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining 413–422. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDM.2008.17 (IEEE, 2008).

Shyu, M.-L., Chen, S.-C., Sarinnapakorn, K. & Chang, L. A novel anomaly detection scheme based on principal component classifier. In Proceedings of the IEEE Foundations and New Directions of Data Mining Workshop 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDMW.2003.1260971 (IEEE Computer Society, Melbourne, FL, USA, 2003).

Goldstein, M. & Dengel, A. Histogram-based outlier score (HBOS): A fast unsupervised anomaly detection algorithm. In KI 2012: German Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Poster and Demo Track 59–63 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Key R&D Special Project 2022B02038, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Key R& D Special Project 2022B03031, the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Key R&D Special Project 2023B01025-2, the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 202408120008.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Key R&D Special Project 2022B02038, in part by the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Key R& D Special Project 2022B03031, and in part by the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Key R&D Special Project 2023B01025-2, also in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 202408120008.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. analyzed and improved the model, conducted experiments, and wrote the manuscript test. J.J.Z. provided guidance on research methods and writing. M.Y.Z. provided writing advice.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Zhang, J.J. & Zhang, M.Y. FreFilterTST: a dynamic channel graph sparsification approach to multivariate time series anomaly detection with frequency-domain restoration. Sci Rep 16, 3289 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33186-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33186-1