Abstract

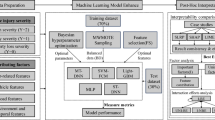

Urban road traffic safety is facing severe challenges, with limited police resources leading to a large number of traffic accidents failing to receive timely response and rescue. The key to alleviating this contradiction lies in optimizing the utilization efficiency of police resources. This study investigates the police resource dynamic dispatching problem for traffic accident response under uncertainties in accident occurrence time, location, and police handling duration. A dynamic assignment optimization model for traffic police is constructed, and a quantile-based Status Evaluation Strategy (SE) for police dispatching is proposed to solve the model, which leverages historical accident handling duration quantiles to assess police status. Empirical analysis is conducted using accident data from Yinzhou District, Ningbo (January-July 2024; 151 days, 13,793 accidents). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test is employed to compare the proposed strategy with traditional Greedy Idle Immediate Response Strategy (IR) and Time-Window-based Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search Response Strategy (ALNS). Results show that the Status Evaluation Strategy using the 90th percentile handling duration (SE90) performs best, significantly reducing accident handling delay (SE90-IR: z= − 5.254, p < 0.001, r = 0.428; SE90-ALNS: z= − 3.394, p < 0.001, r = 0.276), and exhibits better performance stability compared to the same strategy using the 75th percentile handling duration (SE75). Further analysis of delay components reveals that SE90 outperforms others by better balancing the conflict between dispatching decision delay and total travel time of police. This study provides theoretical foundations and technical frameworks for developing intelligent dynamic police resource allocation systems in urban traffic accident response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid urbanization in China has led to a surge in motor vehicle ownership, while road traffic accidents continue to rise sharply1. This has exacerbated the structural contradiction between insufficient traffic police resources at the grassroots level2 and their fragmented spatial distribution3. Limited police resources struggle to respond promptly to sudden traffic accidents, resulting in widespread response delays. This not only prolongs traffic congestion at accident scenes but also significantly elevates the risk of secondary collisions4. Although accident rapid handling procedures5,6 have improved efficiency in handling minor accidents through streamlined workflows, a substantial number of complex cases still require on-site police intervention, such as those involving casualties, liability disputes, or hit-and-run scenarios. Mandatory procedures such as on-site investigations, evidence collection, and traffic management for such accidents introduce significant uncertainty in handling duration. Against this backdrop, traditional static planning and idle-response police assignment models are increasingly incompatible with China’s dense, high-traffic urban road networks. There is an urgent need to optimize resource allocation through task status evaluation assignment mechanisms, thereby resolving the fundamental conflict between insufficient police resources and response timeliness.

The key to police dispatching for traffic accident response lies in the reasonable matching of police officers to accidents, along with optimized decision-making on accident handling sequence. Existing research primarily revolves around two paradigms: police allocation models emphasizing resource planning7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, and police dispatching models focusing on accident response15,16,17.

The core of police allocation paradigm emphasizing resource planning is police quantity optimization or patrol route planning. A typical approach in this paradigm involves developing models using queueing theory to explore police resource optimization: To address road traffic emergency police allocation needs, MIAO et al. established a multi-dimensional M/M/C/M queueing model7 to calculate the minimum required emergency police force; HU et al. proposed a police resource optimization method based on queueing theory under road grid management8 to alleviate the conflict between limited police resources and delayed accident response; LI et al. developed an optimized model for urban police allocation by integrating multivariate fitting with M/M/S queuing theory9, and rigorously validated it through case studies. ADLER et al. designed a location allocation model based on linear programming10 to study traffic police task assignment and route planning; LI et al. constructed a traffic police patrol model on signal-controlled road networks11 to achieve full network coverage with minimal patrol time; HU et al. proposed a patrol route planning model minimizing total traffic police dispatch distance12. However, these studies predominantly rely on historical data, exhibiting static characteristics that struggle to adapt to dynamic, time-varying accident response demands. TÜRKAN et al. introduced machine learning algorithms to predict accident locations, timings, and durations for optimizing patrol point configurations13, reducing response times, carbon emissions, and disposal costs, and thus enhanced dynamic performance to a certain extent compared to the aforementioned methods. Overall, police allocation models predominantly adopt macro-level planning or static distribution approaches. Even when incorporating accident prediction mechanisms, their outcomes are unsuitable for direct application in dynamic, time-varying accident response scenarios. This limitation arises from two key factors: a) specific accidents are inherently unpredictable to a certain degree due to sporadic and stochastic inducing factors that disrupt their temporal, spatial, and severity patterns; b) all predictive models contain inherent errors14, and directly deploying these imprecise predictions to guide dynamic police assignment, without resilient design buffers, will inevitably result in assignment failures.

The core of police dispatching paradigm focuses on accident response lies in accident-police matching mechanisms and accident handling sequence optimization. DUNNETT et al. developed an accident response optimization framework integrating route planning and optimal officer dispatch by synthesizing critical factors15 including fastest response time, real-time traffic dynamics, driver qualifications, officer availability, and service fulfillment rates. ZHOU et al. proposed a dual-objective dynamic traffic accident response planning model addressing minimum resource allocation and minimal accident handling delay under the time-window mechanism16, solved through an ALNS algorithm under both real-time dynamic resolution and global static resolution. However, constrained by the solving mechanism of optimization problems, that particularly the inability to acquire global feedback during real-time iterations, existing studies either limit decision-making to available idle officer, or adopt semi-dynamic strategies with fixed time-window optimization cycles, resulting in constrained global optimization scope. CHEN et al.17 addressed the overlooked patrol coordination complexities in traditional research, such as multi-officer patrol synchronization and unpredictable patrol routes, by developing a heuristic-Bayesian hybrid real-time strategy for collaborative patrol route decision-making. While this approach establishes a paradigm for global optimization in dynamic decision-making, its probabilistic evaluation methodology remains overly complex for practical implementation. Furthermore, existing models require validation in long-term, large-scale accident response scenarios to ensure operational stability.

This study investigates the police resource dynamic dispatching problem for traffic accident response under uncertainties in accident occurrence time, location, and police handling duration. A dynamic assignment optimization model for traffic police is constructed, and a quantile-based Status Evaluation Strategy (SE) for police dispatching is proposed to solve the model, which leverages historical accident handling duration quantiles to assess police status. Empirical analysis is conducted using accident data from Yinzhou District, Ningbo (January-July 2024; 151 days, 13,793 accidents). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test18,19 is employed to compare the proposed strategy with traditional Greedy Idle Immediate Response Strategy (IR) and ZHOU et al.‘s Time-Window-based Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search Response Strategy (ALNS)16. Results unequivocally demonstrates the SE’s remarkable overall superiority in reducing accident handling delay. This study provides theoretical foundations and technical frameworks for developing intelligent dynamic police resource allocation systems in urban traffic accident response.

Problem analysis and modeling

Problem description

This study investigates the police resource dynamic dispatching problem for traffic accident response under uncertainties: after a traffic accident occurs, involved parties remotely report basic information of the accident (such as occurrence time, location, severity, type, etc.) to the traffic accident handling center. The center then assigns an appropriate traffic police officer to the scene to handle the accident, aiming to minimize the average daily accident handling delay, based on a comprehensive assessment of officers’ real-time position, work status, and estimated arrival time. In this global dynamic dispatching problem, the occurrence time and location of an accident are unknown before it happens, and its actual handling duration remains unknown until an officer completes its handling.

Model construction

-

(1)

Accident Parameter Model.

Assume that upon the occurrence of the accident k, the traffic accident handling center immediately receives its basic information: a) occurrence time, denoted as tkO; b) location, denoted as pk, described by longitude and latitude coordinates; c) severity, denoted as Sk, categorized into three levels: property damage, injury, fatality; d) type, denoted as Tk, categorized into: unilateral motor vehicle accident (MV), unilateral non- motor vehicle accident (NMV), NMV vs. NMV conflict, NMV vs. pedestrian conflict, MV vs. MV conflict, MV vs. NMV conflict, MV vs. pedestrian conflict. Thus, the accident k is described as Ck={tkO, pk, Tk, Sk}.

The actual handling time for the accident k is denoted as tk, defined as the time difference between its responsible officer’s arrival time to the scene and the time handling completed. The expected handling time for accident k is denoted as \(\bar{t}_{k}\), obtained from historical records of accidents with the same type or severity using certain quantile statistics, and the expected handling time corresponding to the d% quantile is denoted as \(\bar{t}_{k}\left(d\right)\), e.g., \(\bar{t}_{k}\left(50\right)\) for the 50% quantile expected handling time.

-

(2)

Police Dispatching Calculation Model.

Traffic police officers start their daily tasks at their respective substations. Assume that the position of the officer i at time t is denoted as pit. Clearly, pi0=P0, where P0 is the location (longitude, latitude) of the substation that officer i belonged. The time the officer i arrives at the location of the accident k and begins handling is denoted as tkiS. And the time he complete handling is denoted as tkiE. The actual handling time of accident k is:

If the officer i is handling the accident k at time t, then pit=pk. If the officer i is not immediately assigned a new task after completing the accident k, he will remain at the scene of accident k to monitor traffic flow16,20.

The status of officer i at time t is denoted as xi(t). If officer i is handling an accident or has been assigned to handle accident k at time t, then xi(t) = 1; otherwise, xi(t) = 0. The feasibility of assigning officer i to accident k at time t is denoted as xki(t). If the dispatch is feasible, xki(t) = 1; otherwise, xki(t) = 0.

Furthermore, since dispatching is based on estimated officer status, a parameter that represents potential feasibility of dispatching \(\tilde{x}_{{ki}} \left( t \right)\) is introduced: if dispatching officer i to accident k is potentially feasible, that despite officer i is handling an accident so that preventing immediate be dispatched, but it is estimated that he can arrive before accident k’s handling deadline, \(\tilde{x}_{{ki}} \left( t \right) =1\); otherwise, \(\tilde{x}_{{ki}} \left( t \right) =0\). The relationship between xki(t), \(\tilde{x}_{{ki}} \left( t \right)\), and xi(t) is constrained:

The actual dispatch decision for accident k to officer i is denoted as xki. If the decision at time t assigns officer i to accident k, then xki=1; otherwise, xki=0. xki and xki(t) are constrained:

Each accident k is assigned to exactly one officer:

The solution core of the global dynamic police dispatching problem is to determine xki optimally. The dispatching decision delay of accident k, denoted as wkd, is defined as the time difference between the accident occurrence time tkO and the time its responsible officer is assigned:

The actual handling delay of accident k, denoted as wk, is defined as the time difference between the accident occurrence time tkO and the time its responsible officer actually arrives at the scene tkiS:

Clearly, a constraint relationship exists between wkd and wk:

Where \(\:{t}_{R({p}_{it},{p}_{k})}^{i}\) represents the travel time for the responsible officer to reach the new accident from his current location, calculated as following:

Where R(a,b) is the shortest route from point a to b in a road network; L(r) is the length of route r. vT(r) is the average vehicle speed on route r during time period T corresponding to time t.

-

(3)

Dispatching Optimization Objective.

The optimization objective is to minimize the average daily accident handling delay:

Task status evaluation strategy

The critical aspect of the task status evaluation strategy (SE) lies in evaluating the potential dispatching feasibility of officer through an expected accident handling duration. Subsequently, a comparative analysis is conducted between dispatching feasibility and optimization metrics to finalize the dispatch decision. Detailed implementation is described as follows:

Assume accident k occurred at time t. Analyze the dispatching feasibility xki(t) and the potential dispatching feasibility \({\tilde {x}_{ki}}(t)\) for officer i to handle accident k.

a) Idle Officer: If officer i is idle at time t, thus xi(t) = 0. His expected arrival time at accident k is:

If\(\:{t}_{ki}^{e}\left(t\right)\le\:{t}_{k}^{O}+{P}_{k}\), which means that officer i can arrive before the allowed latest handling deadline for accident k. Where Pk denotes the maximum permissible handling delay for accidents, which is determined by the police department based on the accident severity level. And then set \(\tilde{x}_{{ki}} \left( t \right) =1\). According to Eq. 4, xki(t)=1, meaning dispatching officer i to handle accident k is feasible.

b) Officer Handling accident m (within expected handling duration): If officer i is handling accident m at time t, and \(t \le t_{m}^{O} + \bar{t}_{m}\), which means that the officer is still within the expected handling duration of accident m, then xi(t)=1. Calculate the expected time tie(t) that officer i will complete handling accident m, and tkie(t) that his expected arrival time at accident k:

If\(\:{t}_{ki}^{e}\left(t\right)\le\:{t}_{k}^{O}+{P}_{k}\), which means that officer i can arrive before the allowed latest handling deadline for accident k. And then set\(\tilde{x}_{{ki}} \left( t \right) =1\). According to Eq. 4, xki(t)=0, meaning the potential dispatching officer i to handle accident k is feasible.

c) Officer Handling accident m (beyond expected handling duration): If officer i is handling accident m at time t, and \(\:t>{t}_{m}^{O}+ \bar{t}_{m}\), which means that the officer exceeds the expected handling duration of accident m, then xi(t)=1. Calculate the latest allowed completing handling deadline tmiL:

If t < tmiL, which means that officer i may complete handling accident m before tmiL, and then set \(\tilde{x}_{{ki}} \left( t \right) =1\). According to Eq. 4, xki(t)=0. Define \(\:{t}_{ki}^{e}\left(t\right)=\infty\:\) for this case.

At time t, the assignment for accident k selects from all potentially feasible officers:

If xkb(t) = 1, assign officer b to handle accident k, and set xkb=1. Else if xkb(t) = 0, postpone the dispatch decision for accident k until time t + 1.

In special scenarios where multiple pending accidents at time t exhibit overlapping potential feasible sets, a priority-weighted Hungarian optimal dispatching algorithm will be employed to resolve conflicts and determine optimal dispatch.

Results and discussion

To evaluate the performance of SE, this study conducts experimental validation using road traffic accident data from Yinzhou District, Ningbo from January to July 2024. Comparative analyses are performed against two benchmark strategies: a) traditional Greedy Idle Immediate Response strategy (IR), and b) Time-Window-based Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search Response Strategy (ALNS)16. IR operates as follows: upon accident reported, the accident handling center immediately assigns the nearest available officer to the accident scene based on proximity principles. If no available officers exist at the time, the accident is queued until officer become available. For concurrent accidents and multiple available officers, a priority-weighted Hungarian optimal dispatching algorithm will be employed to resolve the allocation.

Specifically, data from January-February 2024 were utilized as training samples for SE to calibrate accident expected handling duration. Based on common statistical percentiles, the 75th and 90th percentile handling duration for accidents of equivalent severity levels were assigned as preset thresholds, generating two strategies: SE75 and SE90. Subsequent methodological comparison and evaluation were conducted using data from March-July 2024. Statistical records indicate that Yinzhou District, Ningbo recorded 13,793 traffic accidents from January to July 2024: 1,322 cases (1,196 property damage, 125 injury, 1 fatality) in January-February, and 12,471 cases (average 83 daily) in March-July (10,721 property damage, 1,747 injury, 3 fatalities). Spatial accident distribution and daily accident frequency patterns are illustrated in Fig. 1, which was generated by MapInfo software, overlaying accidents onto a road network base map licensed from OpenStreetMap (https://openstreetmap.org). In addition, the data structure of accident records is shown in Table 1.

Results

SE75, SE90, IR, and ALNS were applied to solve daily accidents response from March to July 2024. The obtained results are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Overall, SE strategies outperform both IR and ALNS. Specifically:

Compared to IR, SE75 reduced total handling delay by 6,097.0 min (40.4 min/day on average, a 6.2% reduction); compared to ALNS, it also reduced total handling delay by 185.0 min (1.2 min/day on average, a 0.2% reduction).

Compared to IR, SE90 reduced total handling delay by 6,389.0 min (42.3 min/day on average, a 6.5% reduction); compared to ALNS, it also reduced total delay time by 477.0 min (3.2 min/day on average, a 0.5% reduction).

Further detailed comparisons over 151 days reveal:

SE75 vs. IR: SE75 outperformed IR on 77 days (with smaller daily handling delay), with a maximum delay difference percentage of 26.4% (30-April, 246 accidents) and an average of 10.8%. It underperformed on 54 days (with larger daily handling delay), with a maximum difference of 8.4% (3-June, 67 accidents) and an average of 2.0%. Results were tied on 20 days.

SE75 vs. ALNS: SE75 outperformed ALNS on 89 days, with a maximum difference of 10.9% (28-April, 61 accidents) and an average of 2.9%. It underperformed on 52 days, with a maximum difference of 14.4% (25-March, 117 accidents) and an average of 3.4%. Results were tied on 10 days.

SE90 vs. IR: SE90 outperformed IR on 77 days, with a maximum difference of 25.9% (30-April) and an average of 11.1%. It underperformed on 38 days, with a maximum difference of 12.1% (5-April, 65 accidents) and an average of 2.1%. Results were tied on 36 days.

SE90 vs. ALNS: SE90 outperformed ALNS on 91 days, with a maximum difference of 19.8% (17-May, 97 accidents) and an average of 3.7%. It underperformed on 48 days, with a maximum difference of 11.9% (4-July, 85 accidents) and an average of 3.8%. Results were tied on 12 days.

To conduct a granular comparison of the four strategies, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed on paired schemes, followed by Bonferroni correction21,22. Results are presented in Table 2.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test demonstrated that SE90 achieved the best overall performance. Compared to IR, SE90 significantly and substantially reduced the median daily accident handling delay (z=-5.254, p < 0.001, p‘<0.006, r = 0.428). Even when solely evaluating outcome superiority without considering effect magnitude, SE90 remained significantly better than IR (z= − 3.544, p < 0.001). Comparable significant improvements were also observed in SE90 vs. ALNS comparisons.

Although SE75 also outperformed IR and ALNS statistically, its performance stability was inferior to SE90 based on the sign test results vs. IR (z= − 1.922, p = 0.055). ALNS exhibited no significant advantage over IR (z= − 1.424, p = 0.155, r = 0.116). These findings suggest that SE90 significantly reduces median accident handling delay compared to IR and ALNS strategies across most operational scenarios, demonstrating superior performance.

Equation 5–7 show that accident handling delay comprises two components: dispatching decision delay and total travel time of police. This study further analyzed the practical performance and operational characteristics of SE strategies through these two dimensions.

The dispatching decision delay

The emergence of dispatching decision delay fundamentally stems from insufficient police resource availability or spatial imbalance, resulting in no idle officers available for dispatch at the accident location. However, the dispatching decision delay performance varies significantly across strategies. Taking the 15th traffic accident occurred at 07:13 (433rd minute) on 11-March as a case study, this section examines the dynamic decision-making processes of SE75 and IR, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Accident #15 occurs at 433rd minute. An idle officer (#1) is near the site; and his travel time will be 20 min.

When IR strategy was implemented, the responsible officer is Officer #1, and w15d = 0.

When SE75 strategy was implemented, there were three potentially dispatching feasible officers: Officer #1 (idle status), Officer #2 (busy status), and Officer #3 (busy status). Among them, Officer #1 was expected to arrive at 453rd minute (estimated travel time: 20 min), then \(\:{t}_{\text{15,1}}^{e}\left(433\right)=453\); Officer #2 was expected to arrive at 452nd minute (estimated travel time: 8 min): \(\:{t}_{\text{15,2}}^{e}\left(433\right)=452\), \(\:{t}_{2}^{e}\left(433\right)=443\); Officer #3 was expected to arrive at 460th minute (estimated travel time: 11 min): \(\:{t}_{\text{15,3}}^{e}\left(433\right)=460\), \(\:{t}_{3}^{e}\left(433\right)=449\). Clearly, no dispatch decision was made at 433rd minute, so w15d(433)=1. Similarly, no dispatch decision was made until 442nd minute: \(\:{t}_{\text{15,2}}^{e}\left(t\right)=452\), \(\:{t}_{\text{15,3}}^{e}\left(t\right)=460\), \(\:{t}_{\text{15,1}}^{e}\left(t\right)=453+(t-433)\), w15d(t)=t-432. At 443rd minute, Officer #2 failed to complete his task as expected, while Officer #3 completed his task ahead of schedule: \(\:{t}_{\text{15,2}}^{e}\left(443\right)=\infty\:\), \(\:{t}_{\text{15,3}}^{e}\left(443\right)=454\), \(\:{t}_{\text{15,1}}^{e}\left(443\right)=463\). At 442nd minute, SE75 ultimately decided Officer #3 as the responsible officer for accident #15, with w15d=11.

It can be seen that for accident #15, the total handling delay under SE75 is 22 min (including 11 min of dispatching decision delay and 11 min of its responsible officer travel time), while under IR, it is 20 min. Furthermore, if Officer #3 had not completed his task ahead of schedule at 443rd minute, the total handling delay of accident #15 under SE75 would be longer. It indicates that SE strategy cannot be effective in positively reducing accident handling delay in all scenarios. If certain accidents fail to be completed handling as expected, they may increase an additional dispatching decision delay to subsequent accidents, thereby potentially increasing total handling delay of subsequent accidents. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test results demonstrating the performance of the four strategies in dispatching decision delay are detailed in Table 3.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test demonstrated that all pairwise comparisons between strategies achieved statistical significance (p‘<0.006), and this finding further corroborated by sign test results (p < 0.001). These results consistently indicate fundamental differences in dispatching decision delay across strategies.

Median comparison of dispatching decision delay revealed a clear performance hierarchy: IR exhibited optimal performance (0.0 min), followed by SE90 (5.0 min), SE75 (10.0 min), while ALNS showed the longest delays (14.0 min).

IR’s superiority stems from its dispatching mechanism, which immediately dispatches available officers upon accident reported, entirely eliminating additional decision delay risks caused by failed completion of prior accidents. SE90 demonstrated significant advantages over SE75 (z= − 6.131, p < 0.001, r = 0.499), primarily due to: a) longer estimated handling duration can effectively reducing uncertainty-induced delays; b) longer estimated handling duration inclines the decision to dispatch an idle officer, when this idle officer exist at the decision time, rather than delaying to search for a more optimal candidate. ALNS’s inferior performance compared to IR/SE75/SE90 highlights inherent limitations of time-window-based decision-making in high-dynamic dispatch scenarios. Its intrinsic framework delay becomes particularly detrimental in rapid-response demand.

The travel time of the responsible police officer

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test results demonstrating the performance of the four strategies in the travel time of responsible officers are detailed in Table 4.

The results indicate that ALNS, SE75, and SE90 exhibit optimal performance in the travel time, with comparable optimization effects, while IR demonstrates the poorest performance. Contrary to the daily total accident handling delay revealed in Table 2, both the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and the sign test confirm that IR is significantly inferior to SE75, SE90, and ALNS in terms of the travel time (p < 0.001). This contrasts sharply with the dispatching decision delay comparison in Table 3, suggesting that although IR selects the locally optimal officer at decision time, it fails to achieve global optimization by potentially dispatching distant officers, thereby increasing the travel time to prioritize rapid response. ALNS shows marginal advantages over SE75 and SE90 in the travel time (vs. SE75: z= − 0.313, p = 0.754, r = 0.025; vs. SE90: z= − 2.080, p = 0.038, r = 0.169), indicating that after the introduction of time-window-based mechanisms, the large neighborhood adaptive search plays a constructive role in dispatching officers to nearby accident locations, yet its performance stability remains suboptimal. SE75 exhibits marginally better performance than SE90 in the travel time (z= − 1.380, p = 0.168, r = 0.112), though the difference is not statistically significant. This outcome stems from the decision-making mechanism of SE: longer estimated handling duration inclines the decision to dispatch an idle officer, when this idle officer exist at the decision time, rather than delaying to search for other more optimal candidates, thereby increasing the travel time.

Conclusions

This study investigates the police resource dynamic dispatching problem for traffic accident response under uncertainties in accident occurrence time, location, and police handling duration. A dynamic assignment optimization model for traffic police is constructed, and a quantile-based Status Evaluation Strategy (SE) for police dispatching is proposed to solve the model, which leverages historical accident handling duration quantiles to assess police status. Empirical analysis is conducted using accident data from Yinzhou District, Ningbo (January-July 2024). Results demonstrate that, compared with the traditional Greedy Idle Immediate Response Strategy (IR) and the Time-Window-based Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search Response Strategy (ALNS), SE significantly improves police resource utilization rates while reducing overall accident handling delay, thereby exhibiting strong practical value and technical superiority. Detailed breakdown analysis of delay components further reveals:

-

a.

In terms of dispatching decision delay, SE inferior performance compared to IR, due to the risk of additional decision delay caused by failure to complete handling accidents within estimated time, yet outperforms ALNS.

-

b.

Regarding travel time, SE significantly outperforms IR, while exhibiting no statistically significant disadvantage against ALNS. This indicates that SE effectively identifies and dispatches potentially available officers near accident locations.

-

c.

Employing the 90th percentile handling duration to evaluate police status represents the optimal choice for SE, effectively balancing the conflict between reducing dispatching decision delay and travel time, thereby achieving the best performance in minimizing overall accident handling delays.

Future work will focus on two directions:

-

a.

Enhancing police dispatch strategies through deeper integration of regional accident intensity patterns with resource distribution configurations.

-

b.

Incorporating enriched decision-making mechanisms (e.g., task preemption and flexible police resource allocation) to improve the strategy’s performance under high density accident scenarios.

Data availability

The accident record data supporting the findings of this study are available from the Ningbo Municipal Public Security Bureau - Traffic Police Division, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and so are not publicly available. The data are, however, available from the author Minjie Zhang (zhangmj@nbut.edu.cn) upon reasonable request.

References

National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook 2024 [DB/OL]. [2025-06-27]. (2024). https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2024/indexch.htm

Wang, T. A Study on the problems of and solutions to the public travel service of Chengdu in the background of intelligent transportation (University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, 2022).

Wang, Q. Research on auxiliary police team management under the background of current police reform - taking the public security bureau of G County, D City as an Example (Shandong University, 2022).

Ye, Z. & Zhou, Y. A coverage model for optimizing traffic Police deployment in emergency traffic incident management. Police Technol. 01, 90–94 (2021).

Luo, H. A study on the rapid handling and fast claims settlement mechanism for minor road traffic accidents in Guangxi. Economic Res. Ref. (11), 91–93. https://doi.org/10.16110/j.cnki.issn2095-3151.2017.11.020 (2017).

Xu, W. Research on Emergency Management of Highway Traffic Accidents in Yunnan ProvinceYunnan Minzu University, (2023). https://doi.org/10.27457/d.cnki.gymzc.2023. 000061.

Miao, M., Cao, Y., Li, Q. & Zhang, J. Path and method of scientific allocation for road traffic emergency Police resources under the background of big data. J. People’s Public. Secur. Univ. China (Science Technology). 28 (4), 39–46 (2022).

Hu, Z., Zhou, J., Guo, X. & Ma, C. Allocation of traffic Police resources based on queuing theory. China Saf. Sci. J. 34 (7), 178–185. 10.16265/j. cnki.issn1003-3033.2024.07 (2024).

Li, Y., Yang, Y., Song, Y. & Li, N. Analysis of Police force allocation in a City based on multiple fitting and multi-station queuing theory. J. Math. Pract. Theory. 54 (8), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.20266/j.math.2024.08.018 (2024).

Adler, N., Hakkert, A., Kornbluth, J., Raviv, T. & Sher, M. Location-allocation models for traffic Police patrol vehicles on an interurban network. Ann. Oper. Res. 221 (1), 9–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-012-1275-2 (2014).

Li, Z., Zhao, N. & Tan, J. Research on traffic Police patrol model considering the impact of traffic signals [J]. Transp. Syst. Eng. Inform. 15 (4), 118–122. https://doi.org/10.16097/j.cnki.1009-6744.2015.04.018 (2015).

Hu, Z., Chen, Y., Zheng, X. & Wu, H. Collaborative patrol path planning method for air-ground heterogeneous robot systems. Control Theory Appl. 39 (1), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.7641/CTA.2021.00918 (2022).

Türkan, Y. & Ulu, M. A hybrid approach to traffic incident management: machine learning-based prediction and patrol optimization. IEEE Access. 13, 43455–43472. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3544765 (2025).

Zhou, Y. et al. An integrated approach for addressing data imbalance in predicting fatality of helicopter accident. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 267(Part B). 111921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2025.111921 (2026).

Dunnett, S., Leigh, J. & Jackson, L. Optimising Police dispatch for incident response in real time. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 70 (2), 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/01605682.2018.1434401 (2019).

Zhou, J., Zhang, M. & Ding, H. An ALNS-based approach for the traffic-police-routine-patrol-vehicle assignment problem in resource allocation analysis of traffic crashes. Traffic Inj. Prev. 25 (5), 688–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/1538 (2024).

Chen, H., Cheng, T. & Wise, S. Developing an online cooperative Police patrol routing strategy. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 62, 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2016.10.013 (2017).

Broadbent, D. et al. Cognitive load, working memory capacity and driving performance: A preliminary fNIRS and eye tracking study. Transp. Res. Part. F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 92, 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2022.11.013 (2023).

Kalair, K. & Connaughton, C. Anomaly detection and classification in traffic flow data from fluctuations in the flow-density relationship. Transp. Res. Part. C: Emerg. Technol. 127, 103178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2021.103 (2021).

Mukhopadhyay, A. et al. A review of incident Prediction, resource Allocation, and dispatch models for emergency management. Accid. Anal. Prev. 165, 106501. https://doi.org/10.1 016/j.aap.2021.106501 (2022).

Andersson, J., Warner, H., Henriksson, P., Andrén, P. & Stave, C. The proportions of severe and less severe bicycle crashes and how to avoid them. Transp. Res. Part. F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 106, 169–178. https://doi.org/10.101 6/j.trf.2024.07.027 (2024).

Seupke, S., Segar, S. & Baumann, M. Development of a mental model questionnaire framework: a systematic approach to measuring mental models in automated driving. Transp. Res. Part. F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 114, 686–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2025.06.024 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Basic Public Welfare Research Project of Zhejiang Province (Project No. LGF20F030004), “14th Five-Year Plan” Undergraduate and Postgraduate Teaching Reform Project of Zhejiang Province (Project No. JGCG2024460), Ningbo Natural Science Foundation (Project No. 2023J028).

Funding

This study was supported by Basic Public Welfare Research Project of Zhejiang Province (Project No. LGF20F030004), “14th Five-Year Plan” Undergraduate and Postgraduate Teaching Reform Project of Zhejiang Province (Project No. JGCG2024460), Ningbo Natural Science Foundation (Project No. 2023J028).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-original draft & editing, Supervision. Z.J.: Conceptualization, Writing-review. D.S.: Investigation, Writing-review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M., Zhou, J. & Dong, S. Task status evaluation strategy for dynamic traffic police dispatching in accident response. Sci Rep 16, 3506 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33234-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33234-w