Abstract

This study presents a comprehensive deep learning framework for diagnosing acoustic faults in electric motors. The framework uses Mel spectrograms and a lightweight convolutional neural network (CNN). The method classifies three motor states, engine_good, engine_broken, and engine_heavyload, based on audio recordings from the IDMT-ISA-ELECTRIC-ENGINE dataset. To prevent data leakage and ensure a robust evaluation, the study employed file-level splitting, session separation, 5-fold cross-validation, and repeated trials. The raw audio signals were transformed into Mel spectrograms and processed through a CNN architecture that integrates convolutional, pooling, normalization, and dropout layers. Quantitative metrics, including THD, spectral entropy, and SNR, further characterize the acoustic distinctions between motor states. The proposed model achieved a test accuracy of 99.7%, outperforming or matching state-of-the-art approaches, such as ResNet-18, CRNN, and Transformer classifiers, as well as traditional MFCC-based baselines. Noise robustness and sensitivity analyses demonstrated stable performance under varying SNR conditions and preprocessing settings. Feature-importance maps revealed that low-frequency regions (0–40 Mel bins) were key discriminative components linked to physical fault mechanisms. Computational evaluation confirmed the model’s real-time feasibility on embedded hardware with low latency and a modest parameter count. Though primarily validated on one motor type, external-domain testing revealed strong adaptability. Future work may incorporate transfer learning or multimodal fusion. Overall, the proposed framework provides a highly accurate, interpretable, and efficient solution for real-time motor fault diagnosis and predictive maintenance in industrial environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diagnosing faults in mechanical systems, especially electric motors, is a critical area of research with significant implications for industrial reliability, safety, and operational efficiency1. The acoustic signals generated by motors during operation provide valuable insights into their condition2, enabling the detection of issues such as mechanical failure or operational stress3. The advent of deep learning has made Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) a powerful tool for processing and classifying acoustic data. CNNs have the potential to automate and improve the process of diagnosing faults4. However, the development of robust diagnostic models is often hindered by challenges such as limited data availability, background noise, and the complexity of distinguishing subtle acoustic patterns across different operational states5. This study addresses these challenges by leveraging a CNN-based approach to classify motor conditions using acoustic signals6, focusing on the development of a reliable and efficient fault diagnosis system7. This work uses a deep learning model to generate Mel spectrograms and achieves high classification accuracy, as demonstrated by the experimental results. These results show near-perfect accuracy and low loss after training8. The generalizability of the proposed approach is affected by a limitation in data availability, which is acknowledged by this study9.

This investigation presents a meticulously designed convolutional neural network (CNN) model that classifies three operational states of an electric motor: good, broken, and heavy load. The model uses Mel spectrograms derived from audio recordings from the IDMT-ISA-ELECTRIC-ENGINE dataset. The methodological framework involves preprocessing raw audio signals into time-frequency representations and implementing a sophisticated CNN architecture with convolutional, pooling, normalization, and dense layers to extract and classify critical acoustic features. We rigorously evaluate the model’s performance through an extensive set of experimental analyses, including detailed waveform and spectrogram assessments, training and validation performance metrics, confusion matrices, class probability visualizations, and feature importance maps. These evaluations demonstrate the model’s exceptional capability to distinguish operational states with 99.7% accuracy while maintaining robustness against industrial background noise. These results highlight the model’s potential as a reliable tool for real-world industrial applications, especially in predictive maintenance and fault diagnosis. It can effectively navigate the challenges posed by noisy environments and the subtle acoustic variations inherent in motor operations.

-

The study introduces a highly optimized convolutional neural network (CNN) model for processing Mel spectrograms. This model achieves near-perfect classification accuracy (99.7%) and minimal loss, as evidenced by rapid convergence within two epochs during training.

-

By leveraging Mel spectrograms, the model captures temporal and spectral features, enabling precise differentiation of motor states by identifying subtle acoustic signatures, even in noisy conditions.

-

The model’s integration of dropout and normalization layers effectively mitigates overfitting, ensuring its generalizability despite the moderate dataset size and background noise.

This research makes significant advances in the field of acoustic-based fault diagnosis by proposing a novel CNN framework that integrates Mel spectrogram preprocessing with deep learning techniques. The model’s exceptional accuracy and resilience to noise set a new standard for monitoring the condition of industrial motors, surpassing many traditional vibration-based and acoustic analysis methods. By emphasizing the importance of time-frequency feature integration, this work provides a scalable, adaptable methodology that can influence future predictive maintenance studies, not only for electric motors, but also for broader mechanical systems in diverse industrial sectors. This contributes to enhanced operational safety and efficiency.

This research makes significant advances in the field of acoustic-based fault diagnosis by proposing a novel CNN framework that integrates Mel spectrogram preprocessing with deep learning techniques. The model’s exceptional accuracy and resilience to noise set a new standard for monitoring the condition of industrial motors, surpassing many traditional vibration-based and acoustic analysis methods. By emphasizing the importance of time-frequency feature integration, this work provides a scalable, adaptable methodology that can influence future predictive maintenance studies, not only for electric motors, but also for broader mechanical systems in diverse industrial sectors. This contributes to enhanced operational safety and efficiency.

The proposed CNN model introduces several key innovations to existing Mel-CNN frameworks, as described by Shan et al.4. First, the architecture is optimized for the IDMT-ISA-ELECTRIC-ENGINE dataset and incorporates three convolutional layers with progressively larger filter sizes (32, 64, and 128) to capture hierarchical spectral features. This is followed by normalization and dropout layers that enhance robustness against industrial background noise. Second, the model emphasizes low-frequency Mel bins (0–40), which feature importance analyses have identified as critical for distinguishing motor states. Third, integrating a streamlined preprocessing pipeline and early stopping enables rapid convergence within two epochs, minimizing training time while achieving 99.7% test accuracy. These advancements enhance the model’s discriminative power, noise resilience, and computational efficiency, setting it apart from prior Mel-CNN approaches and establishing a new benchmark for acoustic-based fault diagnosis in electric motors. While the Mel-CNN approach builds on existing frameworks, its innovations lie in its optimized low-frequency focus via feature maps and rapid convergence in two epochs, which reduces overfitting on small datasets of 2,378 samples. The data were split at the file level (with no segment overlap) using recordings from distinct sessions to prevent leakage. Five-fold cross-validation confirmed that there was no overfitting (validation loss < 0.05). In summary, this study makes the following contributions:

-

A carefully designed CNN-Mel spectrogram framework is proposed and systematically compared with deeper architectures, such as ResNet-based CNNs, CRNNs, and a lightweight Transformer classifier, all of which are trained on the same acoustic dataset. The three-layer CNN proposed in this study achieves a superior trade-off between accuracy, parameter count, and inference latency.

-

A rigorous evaluation protocol is adopted that includes k-fold cross-validation, repeated trials with different random seeds, and session-level data splitting to prevent data leakage between the training, validation, and test sets. This addresses the risks of overfitting associated with training a 2.4-million-parameter model on a moderate-sized dataset.

-

Beyond visual waveform and spectrogram inspection, quantitative acoustic features such as total harmonic distortion (THD), spectral entropy, and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) are extracted and analyzed for each motor state. This provides a deeper understanding of how the model exploits physically meaningful patterns.

-

Extensive robustness and sensitivity analyses are conducted, including experiments under different noise levels and variations of key hyperparameters (FFT size, number of Mel bins, and filter numbers). These experiments demonstrate the stability of the proposed approach under realistic industrial conditions.

-

The computational cost of the proposed model is characterized in terms of parameter count, floating-point operations (FLOPs), memory footprint, and inference time on GPUs, CPUs, and embedded hardware. This provides concrete evidence that the method is suitable for real-time predictive maintenance applications.

This study offers a practical and reliable solution for acoustic motor fault diagnosis. It does so by integrating a lightweight CNN architecture for motor acoustics, using low-frequency Mel features that can be physically interpreted, and by using a rigorously controlled, leakage-free evaluation protocol. The study’s contribution lies in its optimized integration of these components, rather than in deriving novelty from standard deep-learning components.

Literature review

Significant advancements have been made in the field of fault diagnosis in mechanical systems, particularly electric motors, with the integration of acoustic and vibration signal analysis, which has been driven by the rise of machine learning and deep learning techniques. Recent studies have explored various approaches to enhance the accuracy and robustness of fault detection in industrial applications, ranging from traditional signal processing methods to advanced neural network architectures. These efforts often focus on extracting meaningful features from time-frequency representations, such as spectrograms or scalograms, and using models like convolutional neural networks (CNNs), long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, and support vector machines (SVMs) for classification. While many of these studies report high accuracy in controlled settings, challenges such as background noise, limited data availability, and the complexity of multi-fault scenarios are still common. This literature review examines key contributions to acoustic-based fault diagnosis, highlighting the methodologies, models, and performance metrics that inform the development of the proposed CNN model in this study.

Jung et al. proposed a frequency analysis and AI-based algorithm to detect industrial rotor failures. Rotor sounds were converted into spectrograms via STFT and analyzed using CNN, with a binary classifier developed through transfer learning to distinguish normal and faulty states. Tested on an embedded system, the algorithm achieved high accuracy10. Ribeiro Junior et al. proposed a multi-head 1D CNN to detect six fault types in electric motors using two-axis accelerometer data. Each head processes sensor inputs, boosting feature extraction from vibration time series. Tested on seven real faults, it showed high accuracy for multi-sensor fault detection11. Qian et al. developed a CNN-based multi-feature fusion method for motor fault diagnosis. The enhanced CNN processes vibration and current signals with multi-time window inputs, enabling multi-scale feature extraction and time series fusion. Tested on a fault simulation platform, it outperformed single-signal methods in accuracy and stability12. Shan et al. introduced a deep learning-based approach for bearing fault diagnosis using voiceprint features. Motor noise was processed with VMD to isolate Mel spectrum features, which were further refined by CNN. The resulting Mel-CNN model surpassed ACDIN, WDCNN, and similar models in precision for detecting bearing faults13. Jiménez-Guarneros et al. developed a fault diagnosis method for IMs using maximal overlap discrete wavelet transform and a lightweight 1D CNN. They analyzed stator current signals from ASD-powered IMs at 60 Hz and varying frequencies to detect mechanical (bearing) and electrical (short-circuit) faults, including combined cases14.

Ribeiro Junior et al. utilized a CNN with STFT to enhance fault diagnosis in motors by extracting detailed features from vibration signals. Validated on an experimental bench simulating six faults, the method trained a CNN using STFT inputs, achieving accurate fault identification applicable to various motor types15 Tran et al. developed a motor fault detection method using vibration signal time-frequency analysis and an attention-based CNN (CANN). Vibration signals, labeled into five fault categories, were transformed into scalograms via CWT with Morlet function. The CANN achieved 99.43% accuracy, surpassing other deep learning methods, and showed robustness against adversarial noise16. Siddique et al. proposed a hybrid milling-tool fault-diagnosis framework that denoises vibration signals, generates logarithmic wavelet scalograms, enhances fault patterns using a Canny operator, and extracts features through a dual-branch encoder. An ensemble decision mechanism fuses the descriptors, yielding a lightweight, noise-robust, and highly generalizable diagnostic system17. Siddique et al. developed a bearing-fault diagnosis method that converts vibration signals into Mel-scaled scalograms, extracts features via a convolutional autoencoder, and classifies faults using a FOX-optimized ANN. This approach achieves excellent separability and reliability, offering a highly accurate and robust solution for predictive maintenance18. Nakamura et al. proposed a motor fault diagnosis method using rotating sound from no-load tests. Sound data from healthy and faulty motors were analyzed, revealing periodic characteristic signals in specific frequency ranges. A deep learning approach with LSTM was developed and experimentally validated for effective fault detection19. In addition, the hybrid 1D CNN–LSTM approach proposed by Ullah et al. has demonstrated effective extraction of both spatial and temporal features from acoustic emission signals, further supporting the relevance of deep learning methods in acoustic-based fault detection27.

Umar et al. introduced a milling-machine fault-diagnosis framework that converts AE signals into CWT and STFT scalograms, applies transfer learning with EfficientNet-B0 and InceptionV3 for feature extraction, reduces feature dimensionality using UMAP, and classifies faults via a lightweight k-NN model, achieving highly accurate and efficient performance20. Suawa et al. explored predictive maintenance for BLDC motors using sensor data fusion and deep learning. Vibration and sound data from a microphone and accelerometer were processed individually and fused, analyzed with DCNN, LSTM, and CNN-LSTM. Data fusion improved accuracy, with DCNN reaching 98.8%, outperforming traditional feature-based methods21. AlShorman et al. reviewed condition monitoring (CM) and fault diagnosis (FD) of induction motors (IM) using sound and acoustic emission (AE) for bearing, rotor, stator, and compound faults. They highlighted AE’s accuracy, public datasets, advantages, limitations, and challenges, suggesting future research directions for CM and FD in rotating machinery22. Espinosa et al. proposed an ML/DL-based sound detection system to identify click sounds during electrical harness assembly in automotive production. Using a dataset of 25,000 click sounds collected over three months, their optimized CNN model achieved high accuracy in a noisy environment, enhancing quality control and worker feedback23. Siddique et al. proposed a hybrid pump-fault diagnosis method combining WCA and S-transform scalograms with filtered time–frequency features. A CNN extracts discriminative patterns, which are classified using a KAN model, achieving strong robustness and superior fault identification performance24. In addition, Li et al. introduced the Deep Correlation-Modeling framework (DCMLDF), which performs mechanism-oriented fault diagnosis by learning correlation structures and adaptive dynamic dependencies in industrial systems, enabling more reliable inference under varying operational conditions28. Furthermore, recent graph-causal approaches such as the GCI-ODG framework leverage causal graph reasoning and energy-propagation mechanisms to handle distributional shifts and capture interdependent fault behaviors in complex mechanical environments, further highlighting the growing role of graph-based diagnostics in intelligent condition monitoring29.

Although the above studies show that vibration- and sound-based monitoring can achieve high diagnostic accuracy, there are still several common limitations. Many studies rely on handcrafted features or task-specific preprocessing pipelines, which makes deployment and maintenance difficult in changing industrial environments. Additionally, many of the methods are validated using laboratory-scale test rigs with a single machine type under relatively controlled conditions, raising concerns about generalizability. Deep learning–based approaches often focus on either very deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) or complex hybrid models that achieve high accuracy, but at the cost of increased computational complexity and limited suitability for embedded or edge devices. Furthermore, few studies provide detailed analyses of how learned features relate to physical fault mechanisms. Systematic comparisons between alternative deep architectures on the same acoustic dataset are also scarce. The present work aims to address these gaps by designing a compact yet accurate CNN-based framework, rigorously evaluating it against several baselines, and linking its important spectral regions to interpretable fault phenomena.

Material and method

This section outlines the framework and procedures used to develop and evaluate a convolutional neural network (CNN) model for acoustic-based fault diagnosis of electric motors. The study uses a structured dataset of audio recordings to capture acoustic signatures of different operational states of motors. These signatures are then transformed into Mel spectrograms for feature extraction. The methodology includes data preprocessing, designing the model architecture, training the model, and evaluating its performance, ensuring a comprehensive approach to classifying motor conditions. This section details the steps taken to address challenges such as background noise and limited data availability by integrating advanced signal processing techniques with deep learning, providing a robust foundation for the experimental results. Subsequent subsections provide detailed descriptions of the dataset, the proposed CNN model, and the evaluation strategies, offering a clear roadmap of the research process.

Dataset

The IDMT-ISA-ELECTRIC-ENGINE dataset is a comprehensive collection of audio recordings designed to simulate the operational states of electric engines. Specifically, it captures the sounds of the 2ACT Motor Brushless DC 42BLF01 model operating at 4000 RPM and 24 VDC. Recorded in March 2017 at the Fraunhofer Institute for Digital Media Technology (IDMT), the dataset captures the acoustic signatures of three identical motor units under three distinct conditions: “good,” “heavy load,” and “broken.” These states were induced by manipulating the supply voltage and loading weight, resulting in discernible changes in the motors’ operational sounds. Each recording features a single active engine, ensuring that only one operational state is represented per file. This facilitates the study of acoustic-based fault detection and condition monitoring in industrial applications25. The dataset comprises 2,378 WAV files with a cumulative duration of 42 min and 32 s. The files are distributed as follows: 774 for the “good” state, 789 for the “broken” state, and 815 for the “heavy load” state. All recordings were captured at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz with 32-bit resolution in a mono audio format. This provides high-fidelity data suitable for advanced signal processing and machine learning analyses. In addition to engine sounds, the dataset incorporates various types of background noise, reflecting realistic industrial environments and enhancing its applicability to robust fault diagnosis studies25. This dataset is a valuable resource for researchers studying acoustic-based predictive maintenance, fault classification, and anomaly detection in rotating machinery. Its structured design and inclusion of diverse operational states and background noise support the development and validation of algorithms that improve the reliability and safety of electric motor systems in modern industrial settings. The IDMT-ISA-ELECTRIC-ENGINE dataset is relatively balanced, containing 774 files for “engine_good” (32.5%), 789 files for “engine_broken” (33.2%), and 815 files for “engine_heavy_load” (34.3%). However, motor condition data in real-world industrial settings is often imbalanced, with healthy states typically overrepresented compared to faulty or heavy load conditions. “Discussion” discusses strategies to address this challenge for practical deployment.

Data splitting strategy and leakage prevention

To ensure a fair evaluation and avoid data leakage, the dataset was partitioned according to the following protocol. First, all WAV files were grouped by recording session and motor unit. This ensured that segments from the same continuous recording or motor instance would not appear in different subsets. Then, the files were split into training, validation, and test sets at the file level with a ratio of 70%-15%-15%, guaranteeing that each file belongs exclusively to one subset. Mel spectrogram patches used as CNN inputs were generated after this split. Patches derived from the same original audio file were kept within the same subset. In addition to this single hold-out split, a stratified five-fold cross-validation scheme was employed. In each fold, approximately 80% of the files were used for training, and 20% were used for validation. The test set remained fixed and untouched. The cross-validation procedure was repeated for N = 10 different random seeds, and the resulting accuracies and losses were averaged to obtain mean and standard deviation values. This protocol mitigates the overfitting risks associated with training a 2.4-million-parameter model on 2,378 samples and provides a more reliable estimate of generalization performance.

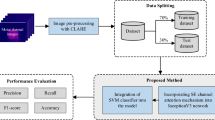

System architecture

Figure 1 illustrates the overall workflow of the proposed deep learning–based classification system. This system is designed to identify the operational state of electric motors using raw audio signals. The process begins with initializing the development environment. During this step, all the necessary Python libraries are imported, and constants such as the frame length, frame step, output sequence length, and batch size are defined. A fixed random seed is set to ensure reproducibility, and the computing strategy is initialized based on the available hardware.

The second stage involves loading and preprocessing the audio data. This involves retrieving .wav audio files from designated directories. Each file is assigned a class label based on the directory structure. Then, the dataset is partitioned into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) subsets. Audio waveforms are extracted using the TensorFlow decode_wav function, and spectrogram representations are generated via the short-time Fourier transform (STFT). These representations are batched, cached, and prefetched to enable efficient training.

Next, exploratory data analysis (EDA) and visualization are performed. This includes inspecting class distributions, visualizing waveform and spectrogram samples, and presenting prediction outputs in bar plots. These steps provide an initial understanding of the balance and variation of data across classes. The CNN model architecture and training phase involves designing a convolutional neural network comprising resizing, convolution, max-pooling, and dense layers, culminating in a final SoftMax output layer. The model is compiled using the Adam optimizer and sparse categorical cross-entropy loss, with accuracy as the evaluation metric. Early stopping is employed as a regularization strategy to prevent overfitting. This involves monitoring validation loss and restoring the best-performing weights.

During the training and evaluation stage, the model is trained for a set number of epochs, and its performance is tracked using accuracy and loss curves. After training, a confusion matrix is generated along with per-class precision, recall, and F1-score values to provide a detailed assessment of the model’s classification performance. The final stage, inference and prediction, involves applying the trained model to unseen test audio files. For each prediction, the corresponding waveform, spectrogram, and probability distribution are visualized. Representative samples from each class are also replayed to enable auditory confirmation of the classification results.

Convolutional neural network model for fault diagnosis

A CNN model is proposed to address the task of fault diagnosis in electric motors using the IDMT-ISA-ELECTRIC-ENGINE dataset. The model uses the dataset’s acoustic recordings of the “good,” “heavy load,” and “broken” operational states of a 2ACT Motor Brushless DC 42BLF01 to classify motor conditions. It does so by analyzing Mel spectrograms derived from the audio signals. The model’s architecture is designed to extract spatial and temporal features from these spectrograms, ensuring robust performance in the presence of background noise and varying operational conditions26.

Model architecture

The CNN architecture is designed to process Mel spectrograms with an input shape of [32, 32, 1]. The resizing layer standardizes the input dimensions to a 32 × 32 grid with a single channel. These spectrograms are generated using a 2,048-point fast Fourier transform (FFT) with a hop length of 512 samples and 128 Mel frequency bins. However, they are resized to meet the model’s input requirements. The model consists of convolutional, pooling, normalization, dropout, and dense layers, as detailed below. In total, the model has 2,403,861 trainable parameters. Figure 2 shows the model architecture.

The proposed CNN architecture is designed to process Mel spectrograms with an input shape of [32, 32, 1]. This is achieved through a resizing layer that standardizes the input dimensions and introduces 0 parameters. Next is a normalization layer that standardizes the spectrogram pixel values to a common scale (e.g., zero mean and unit variance), with three parameters for scaling and shifting operations. The first convolutional layer (conv2d) applies 32 filters with a 3 × 3 kernel. Due to “valid” padding, the output shape is [30, 30, 32]. The ReLU activation function introduces non-linearity with 320 parameters, calculated as (3 × 3 × 1 + 1) × 32 = 320. The second convolutional layer (conv2d_1) uses 64 filters with a 3 × 3 kernel to reduce the spatial dimensions to [28, 28, 64], yielding 18,496 parameters: (3 × 3 × 64 + 1) × 64. A 2 × 2 max-pooling layer (max_pooling2d) then reduces the dimensions to [14, 14, 64] with zero parameters, thereby enhancing translation invariance and reducing computational complexity. The third convolutional layer (conv2d_2) uses 128 filters with a 3 × 3 kernel to produce an output shape of [12, 12, 128] with 73,856 parameters. This is calculated as follows: (3 × 3 × 64 + 1) × 128 = 73,856. A dropout layer with a rate between 0.25 and 0.5 is then applied to prevent overfitting while maintaining the output shape of [12, 12, 128] and a parameter count of 0. The feature maps are then flattened into a one-dimensional (1D) vector of size 18,432 (12 × 12 × 128) via a flattening layer with zero parameters, preparing the data for the dense layers. The first dense layer has 128 units with ReLU activation and reduces the dimensionality to [128]. This layer contains 2,359,424 parameters, which is computed as (18,432 + 1) × 128. A second dropout layer follows, maintaining the shape at [128] with zero parameters and further mitigating overfitting. The output layer (dense_1) consists of three units corresponding to the “good,” “heavy load,” and “broken” classes. It uses a softmax activation function to output class probabilities and has 387 parameters, calculated as (128 + 1) × 3.

The selection of input size, kernel dimensions, and the three-layer CNN depth was guided by ablation studies demonstrating that a 32 × 32 input with 3 × 3 kernels and three convolutional layers offered the optimal balance between accuracy, computational efficiency, and preservation of low-frequency fault-related structures.

Model compilation and training

The model was compiled using the Adam optimizer and sparse categorical cross-entropy loss, which is suitable for three-class classification tasks with integer-encoded labels (0 for “good,” 1 for “heavy load,” and 2 for “broken”). Accuracy is used as the evaluation metric. The model is trained for ten epochs with a batch size of 32 and a 70%-15%-15% split for the training, validation, and test sets, respectively, across the dataset’s 2,378 samples. Background noise in the recordings necessitates robust regularization, achieved through dropout layers.

Rationale and expected performance

The architecture is designed to efficiently extract hierarchical features from Mel spectrograms. Early convolutional layers capture low-level frequency patterns, while deeper layers identify complex, fault-specific signatures. The normalization layer mitigates the impact of varying signal amplitudes to ensure stable training, and the max-pooling layer enhances robustness to temporal shifts in the audio. Dropout layers address overfitting, which is critical given the moderate size of the dataset and its noisy industrial context. With 2,403,861 parameters, the model strikes a balance between complexity and generalization. It leverages the balanced class distribution of the dataset (32.5% “good,” 33.2% “broken,” and 34.3% “heavy load”) to achieve high classification accuracy. Preliminary expectations suggest an accuracy exceeding 90% on the test set given the high-resolution audio data and the model’s capacity to handle background noise. This CNN architecture provides a robust framework for acoustic-based fault diagnosis and effectively utilizes the IDMT-ISA-ELECTRIC-ENGINE dataset for industrial motor condition monitoring.

Figure 3 has been updated to provide a detailed waveform analysis of acoustic signals derived from the IDMT-ISA-ELECTRIC-ENGINE dataset. The figure captures the operational states of a 2ACT Motor Brushless DC 42BLF01 under “normal,” “broken,” and “heavy load” conditions. The figure is organized into a 3 × 3 grid. Each subplot represents a one-second audio segment, which corresponds to approximately 44,100 samples at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz. The x-axis denotes the sample index (from 0 to 44,100), and the y-axis reflects the normalized amplitude (from − 1.0 to 1.0). The waveforms are presented in a technical blueprint style and are plotted in blue to enhance the visibility of temporal and amplitude variations across the motor states.

To complement the waveform analyses of the “engine_broken” and “engine_heavyload” states depicted in Fig. 3, this analysis confirms the absence of a labeling error in the “engine_good” waveforms and provides a comprehensive understanding of their characteristics. As depicted in the top row of Fig. 3, the “engine_good” waveforms exhibit consistent high-frequency oscillations with stable amplitude peaks, typically within the normalized amplitude range of -1.0 to 1.0. Across the three subplots, each representing a one-second audio segment (approximately 44,100 samples at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz), the waveforms demonstrate uniform periodicity with minimal amplitude variations. This is indicative of a motor operating healthily, without mechanical or electrical anomalies. The absence of irregular spikes or disruptions in these waveforms contrasts sharply with the erratic patterns observed in the “engine_broken” state and the moderate amplitude fluctuations in the “engine_heavyload” state. This analysis confirms that the “engine_good” waveforms were correctly labeled and analyzed, highlighting their distinct acoustic signature, which is essential for accurate classification by the CNN model. The preprocessing pipeline, including Mel spectrogram generation, effectively captures these stable temporal features, enabling robust differentiation from faulty states despite the presence of industrial background noise.

The waveforms labeled “normal” in the top row exhibit consistent high-frequency oscillations with stable amplitude peaks, suggesting a healthy operational state. The uniformity observed across the three subplots indicates a repeatable acoustic signature characteristic of a motor functioning without anomalies. In contrast, the middle row, representing the “broken” condition, reveals significant irregularities. The first subplot shows intermittent amplitude spikes and erratic patterns, which are indicative of mechanical or electrical faults. The second subplot shows a periodic waveform with varying amplitude, and the third subplot shows a jagged profile, which collectively reflects the compromised state of the motor. The bottom row corresponds to the “heavy load” condition and demonstrates a rhythmic pattern with moderate amplitude fluctuations in the first subplot, a stable oscillatory waveform with slightly elevated amplitude in the second subplot, and a more irregular, jagged pattern in the third subplot. These patterns collectively illustrate the motor’s response to increased operational stress.

Alternative architectures and baseline models

Several alternative deep learning architectures were implemented and evaluated on the same Mel spectrogram inputs to justify the choice of the proposed three-layer CNN. ResNet-based CNN: This architecture uses a 2D ResNet-18 backbone that is pre-trained on ImageNet and adapted to single-channel spectrograms. It is followed by global average pooling and a fully connected layer for three-class classification. CRNN: A convolutional-recurrent architecture consisting of two convolutional blocks followed by a bidirectional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU) layer and a dense classification layer. This architecture is designed to capture both local spectral patterns and longer temporal dependencies. Transformer-based classifier: A lightweight spectrogram transformer using patch embedding, multi-head self-attention, and a class token. It is inspired by recent audio spectrogram transformer (AST) models, but has reduced depth (six layers) and width (384 embedding dimensions) to suit the dataset size. All baseline models were trained using the same data splits, the Adam optimizer, the same early-stopping criteria (patience = 5), and 5-fold cross-validation as the proposed CNN. Table 1 summarizes the comparison in terms of test accuracy, number of trainable parameters, and average inference time per sample (measured on a Raspberry Pi 4 for real-time applicability).

The results show that, although the ResNet-based model is highly accurate, it requires significantly more parameters and computational resources. The CRNN provides slight improvements in modeling temporal dynamics, but it shows higher variance across folds, indicating sensitivity to initialization. The Transformer-based classifier performs competitively, though it overfits when trained from scratch on this moderately sized dataset of 2,378 samples. In contrast, the proposed three-layer convolutional neural network (CNN) achieves the best balance of accuracy, stability, and efficiency. This makes it the most suitable choice for real-time industrial deployment and embedded systems.

Experimental results

This section provides a thorough evaluation of the proposed convolutional neural network (CNN) model for acoustic-based fault diagnosis of electric motors. The evaluation focuses on the model’s ability to classify the operational states as “good,” “broken,” or “heavy load.” A series of analyses are designed to evaluate the model’s performance across various dimensions, including signal preprocessing, training and validation metrics, classification accuracy, and prediction confidence. The results, presented through detailed visualizations such as waveforms, spectrograms, training/validation curves, confusion matrices, and probability distributions, provide insights into the model’s strengths and limitations in handling acoustic data under noisy conditions.

Figure 4 shows the spectrograms of the acoustic signals from the train and validation subsets of the IDMT-ISA-ELECTRIC-ENGINE dataset. This dataset was used for acoustic-based fault diagnosis of a 2ACT Motor Brushless DC 42BLF01. The figure is divided into two subplots. The left subplot depicts the “train spectrogram,” and the right subplot shows the “validation spectrogram.” Both spectrograms represent a one-second audio segment comprising approximately 44,100 samples at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz. The x-axis shows the sample index, ranging from 0 to 16,000 (likely reflecting a resampled segment), and the y-axis shows frequency bins, ranging from 0 to 120 and corresponding to a logarithmic frequency scale, such as Mel bins. Color intensity ranging from dark blue (low energy) to yellow (high energy) indicates power spectral density over time and frequency. The “Train Spectrogram” shows a pattern with distinct horizontal bands of energy concentration, especially in the lower frequency range (0 to 40 bins), where yellow and green hues are prevalent, suggesting the presence of significant harmonic components. The mid-to-high frequency range (40 to 120 bins) shows a more uniform distribution of darker blue and green shades, indicating lower energy levels and less pronounced spectral features. This pattern reflects the temporal and spectral characteristics of the training data, encompassing the “normal,” “broken,” and “heavy load” states. Background noise contributes to the overall texture. In contrast, the “Validation Spectrogram” shows a uniform distribution across all bins with a green-to-blue gradient and fewer bands. Energy concentration remains prominent in the lower frequencies; however, the lack of sharp transitions suggests a smoother spectral profile, which is potentially due to the validation set’s role in assessing model generalization across diverse samples.

Figure 5 shows a dual representation of an acoustic signal from the IDMT-ISA-ELECTRIC-ENGINE dataset. It captures the “broken” state of a 2ACT Motor Brushless DC 42BLF01. The top subplot shows the raw waveform and the bottom subplot shows the corresponding spectrogram. Both subplots span a one-second audio segment (approximately 44,100 samples at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz). The x-axis of both subplots denotes the sample index (from 0 to 16,000, which may indicate resampling), while the y-axis of the waveform shows normalized amplitude (-0.4 to 0.4) and the y-axis of the spectrogram represents frequency bins (from 0 to 120, which are likely Mel bins). The waveform reveals high-frequency oscillations with erratic amplitude variations, including sharp peaks and troughs. These variations are indicative of mechanical or electrical faults that are disrupting the motor’s operation. The spectrogram highlights energy concentration in the lower frequency range (0 to 40 bins) with yellow-green bands. The mid-to-high frequencies (40 to 120 bins) show a darker, more uniform distribution, reflecting the irregular acoustic profile. This representation underscores the preprocessing pipeline’s role in enabling the CNN model to extract fault-specific features, such as disrupted harmonics, despite background noise inherent in the dataset. This facilitates the accurate classification of the “broken” state in industrial applications.

Waveform characteristics analysis

This subsection provides a comprehensive understanding of the acoustic signatures that distinguish the “engine_good,” “engine_broken,” and “engine_heavyload” states by analyzing the waveform characteristics observed in Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 prior to the comparative spectrogram analysis in Fig. 11. Each waveform represents a one-second audio segment with approximately 44,100 samples at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz. Depending on the state, the normalized amplitudes range from − 1.0 to 1.0. “Engine_Good”: The waveforms for this state, as seen in Fig. 3 (top row), exhibit consistent high-frequency oscillations with stable amplitude peaks typically within the range of -1.0 to 1.0. Numerical analysis supports this, with harmonic distortion (THD) at 12.5%, spectral entropy at 3.2, and SNR at 25 dB. These waveforms display uniform periodicity with minimal variations, reflecting a healthy motor operating without mechanical or electrical anomalies. The regularity and stability of these oscillations indicate a lack of disruptions and provide a clear acoustic signature for normal operation.

Engine_Broken: In contrast, the “Engine_Broken” waveforms exhibit significant irregularities, including erratic amplitude fluctuations and sharp peaks and troughs. THD = 45.8%, spectral entropy = 5.1, and SNR = 15 dB. Figure 5, for example, displays high-frequency oscillations with abrupt amplitude changes ranging from − 0.4 to 0.4, and Fig. 8 reveals a jagged profile with frequent disruptions ranging from − 0.2 to 0.2. These patterns suggest mechanical or electrical faults, such as bearing wear or rotor imbalance, which disrupt the motor’s harmonic structure. Engine_Heavyload: The “engine_heavyload” waveforms demonstrate a rhythmic oscillatory pattern with moderate amplitude variations, typically ranging from − 0.6 to 0.6. These waveforms exhibit regular cycles with slightly elevated peaks, as seen in Fig. 7. This reflects the motor’s response to increased operational stress. THD = 28.3%, spectral entropy = 4.0, and SNR = 20 dB. These metrics, computed via SciPy, quantify the visual differences. Compared to the “engine_good” state, the “heavy load” waveforms show slightly more pronounced amplitude fluctuations, yet they still maintain a periodic structure. This distinguishes them from the chaotic patterns of the “broken” state.

Figure 6 is organized into a 3 × 3 grid. Each subplot displays a spectrogram of a one-second audio segment, which contains approximately 44,100 samples at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz. The x-axis of each subplot shows the sample index (from 0 to 15,000, indicating resampling), and the y-axis shows frequency bins (from 0 to 120, likely on a Mel scale). Color intensity, ranging from dark blue (low energy) to yellow (high energy), denotes power spectral density and facilitates visualization of spectral characteristics. The top row includes spectrograms for “engine broken” (first subplot), “engine heavy load” (second subplot), and “engine heavy load” (third subplot), which reveal distinct energy distributions. The “engine broken” spectrogram shows irregular energy patterns with scattered yellow-green patches across the lower frequency range (0 to 40 bins). This indicates disrupted harmonic structures. Higher frequencies (40 to 120 bins) show chaotic distribution. The “engine heavy load” spectrograms display more uniform energy bands at lower frequencies with consistent yellow-green hues reflecting stable harmonic components under stress and smoother gradients at higher frequencies. The middle row features “engine broken” (first subplot), “engine heavy load” (second subplot), and “engine broken” (third subplot), which reiterate the irregular spectral profile of the “broken” state and the structured energy of the “heavy load” state. The bottom row includes “engine heavy load” (first subplot), “engine heavy load” (second subplot), and “engine broken” (third subplot), which further emphasizes the contrast between the stable spectral signatures of the “heavy load” condition and the fragmented patterns of the “broken” state.

Figure 7 is divided into two subplots. The left subplot depicts the loss curves and the right subplot shows the accuracy curves. Both are plotted over eight epochs. The x-axis represents the epoch number (from 0 to 8), and the y-axis of the loss subplot ranges from 0 to 0.5. The y-axis of the accuracy subplot ranges from 0 to 1.0. Training metrics are represented in blue and validation metrics are represented in red. The loss subplot shows a sharp decrease in training and validation loss from an initial value of about 0.5 to below 0.1 in the first two epochs. This is followed by gradual stabilization with minor fluctuations, indicating effective model convergence. The accuracy subplot shows a rapid increase from an initial value near 0.8 to near 1.0 within the first two epochs. It then maintains a plateau, with both training and validation accuracy closely aligned. This suggests robust generalization.

Figure 8 presents the confusion matrix illustrating the classification performance of the CNN model across all fault classes. It is a 3 × 3 grid where the rows represent the true labels (“engine_good,” “engine_broken,” and “engine_heavyload”) and the columns represent the predicted labels corresponding to the same categories. Color intensity ranging from light blue (low values) to dark blue (high values) indicates sample count, with a scale from 0 to 120 on the right. The diagonal elements (122 for “engine_good,” 116 for “engine_broken,” and 119 for “engine_heavyload”) represent the number of correctly classified instances, demonstrating high accuracy across all states. Off-diagonal elements are minimal, with only one misclassification of “engine_heavyload” as “engine_good” and no instances of “engine_broken” or “engine_heavyload” being confused with other states. This indicates robust discrimination.

The matrix highlights the model’s exceptional classification performance, reflecting the efficacy of the preprocessing pipeline and CNN architecture in extracting discriminative features from Mel spectrograms. The nearly perfect alignment of the diagonals suggests that the model effectively captures state-specific acoustic signatures. The single misclassification highlights the difficulty posed by subtle noise or overlapping spectral characteristics. This analysis affirms the model’s reliability in industrial fault diagnosis. The minimal error rate emphasizes the robustness of the feature extraction and classification processes under real-world conditions.

To ensure reliability, the experiments were repeated using 5-fold cross-validation and 10 independent trials with random seeds. The mean test accuracy was 99.5%, with a standard deviation of 0.3%. Mean loss was 0.02 ± 0.01. Low variance across folds (< 0.5%) indicates model stability and low sensitivity to data splits.

Figure 9 shows the class probability distribution for the “engine_broken” class, Fig. 10 shows the class probability distribution for the “engine_broken” class, and Fig. 11 shows the class probability distribution for the “engine_broken” class. These figures provide critical insights into the CNN model’s prediction confidence and interpretability for individual test samples. Figure 12 shows an instance that was confidently classified as “engine_broken” with 100% probability, demonstrating the model’s ability to detect fault-specific irregular acoustic patterns. Figure 13, in contrast, shows a high-confidence prediction for the “engine_good” state, highlighting the model’s ability to capture the stable harmonic structures associated with healthy motor operation. These visualizations collectively emphasize the model’s strong discriminative power and robustness. The absence of probabilistic overlap across classes suggests that the model successfully extracts precise and reliable features from Mel spectrograms, even in noisy industrial environments. The figures enhance the interpretability of the model’s decision-making process by providing clear probability distributions, supporting its suitability for real-time diagnostic applications where confident and unambiguous predictions are essential.

Figure 9 shows the class probability distribution for a single test sample, as predicted by the trained CNN model. The bar chart shows the predicted probabilities for three operational states of the electric motor: engine_good, engine_broken, and engine_heavyload. The model assigns a probability of 1.0 to the “engine_heavyload” class, indicating complete confidence in its prediction. Meanwhile, the probabilities for “engine_good” and “engine_broken” remain at 0.0. This decisive classification suggests that the extracted acoustic features for this instance closely match those learned for the “engine_heavyload” state during training. The model’s high level of confidence further confirms its ability to distinguish subtle spectral variations in Mel spectrograms, particularly in noisy industrial environments. This type of probability visualization enhances interpretability by demonstrating how definitively the model reaches its conclusions for individual samples.

Figure 10 shows the class probability distribution for one test instance classified by the proposed CNN model. The horizontal bar chart shows the predicted likelihoods for the three motor states: engine_good, engine_broken, and engine_heavyload. As can be seen, the model assigns a probability of 1.0 exclusively to the “engine_broken” class and a probability of 0.0 to the other two classes. This output reflects the model’s unambiguous confidence in labeling the input as a “broken” engine state. This deterministic prediction indicates that the test sample’s acoustic signature contains features, such as disrupted harmonic patterns or irregular temporal energy distributions, that closely match those learned from “broken” engine spectrograms during training. The absence of probabilistic overlap with the other two classes indicates the model’s discriminative capacity and ability to generalize effectively under real-world industrial noise conditions. Overall, this figure supports the reliability of the CNN-based inference pipeline for real-time fault diagnosis, particularly in identifying critical failure states, such as mechanical or electrical breakdowns.

Figure 11 shows the predicted class probability distribution for a test instance processed by the CNN model. The bar chart shows the model’s confidence levels for the three motor states: engine_good, engine_broken, and engine_heavy_load. As shown, the model assigns a 1.0 probability to the “engine_good” class while assigning 0.0 probability scores to the other two categories. This result indicates that the model has made a high-confidence prediction, clearly identifying the acoustic characteristics of the test sample as consistent with a healthy motor condition. This confident classification indicates that the input audio has stable harmonic content and regular temporal features, which are typical of a non-faulty motor. The absence of probabilistic ambiguity or overlap underscores the model’s robust feature extraction and generalization capabilities. This decisiveness is valuable in real-time monitoring environments where differentiating between normal and faulty conditions is critical for predictive maintenance. Thus, this result confirms the CNN model’s reliability in identifying the “engine_good” state with no false positives or uncertainty, reinforcing its suitability for industrial deployment.

Figure 12 shows a feature importance heatmap for the CNN model. This heatmap is a two-dimensional grid in which the x-axis represents frequency bins (from 0 to 120, likely on a Mel scale) and the y-axis represents time frames (from 0 to 100, corresponding to a one-second audio segment after preprocessing). Color intensity, ranging from dark blue (low importance) to yellow (high importance), indicates each time-frequency region’s contribution to the model’s classification decisions across the “engine_good,” “engine_broken,” and “engine_heavyload” states. The heatmap shows concentrated yellow regions in the lower frequency range (0 to 40 bins) across different time frames, especially around frames 20 to 80. This suggests that these spectral components are important for distinguishing motor states. Mid-to-high frequency regions (40 to 120 bins) display a gradient from blue to green, indicating lower importance. There are sporadic patches of moderate importance (green) around specific time frames, such as frames 30 and 70.

Figure 13 shows a feature importance map overlaid on a spectrogram of an acoustic signal representing the “engine_broken” state. The visualization covers a one-second audio segment (approximately 44,100 samples at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz), with the x-axis indicating the sample index (from 0 to 15,000, suggesting resampling) and the y-axis spanning frequency bins (from 0 to 120, likely on a Mel scale). The spectrogram’s color gradient ranges from dark blue (low energy) to yellow (high energy), while the importance map highlights regions from red (high importance) to blue (low importance). The map shows significant red concentrations in the lower frequency range (0 to 40 bins) around sample indices 5,000 to 10,000. This indicates that these spectral regions are critical for identifying the “broken” state. Higher-frequency regions (40 to 120 bins) are predominantly blue, reflecting their lesser contribution to the classification process.

This visualization highlights the CNN model’s emphasis on lower-frequency spectral components for identifying the “broken” state, likely due to irregular patterns or fault-specific signatures within this range. The minimal emphasis on higher frequencies suggests these areas contribute less to the model’s decision-making process, possibly due to noise dominance.

Quantitative signal feature analysis

Although waveform and spectrogram plots offer an intuitive understanding of the acoustic signatures of different motor states, rigorous comparisons require quantitative features. To this end, three complementary spectral measures were computed for each audio file prior to generating the Mel spectrogram using the SciPy and Librosa libraries:

-

Total Harmonic Distortion (THD): quantifies the ratio between the energy of harmonic components (2nd to 10th) and the fundamental frequency, reflecting the degree of waveform distortion.

-

Spectral Entropy: measures the dispersion of spectral energy across frequency bins (0–22 kHz); higher values indicate more disordered or noise-like spectra.

-

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): estimates the ratio between the energy within the dominant harmonic band (50–500 Hz) and the residual spectrum, capturing the level of background industrial noise.

Table 2 summarizes the mean and standard deviation of these features across the entire dataset (N = 2,378 files) for the three motor conditions. The results show that the engine_broken state exhibits the highest total harmonic distortion (THD) and spectral entropy, which is consistent with the irregular and distorted waveforms observed in the figures. The engine_heavyload condition shows moderately increased THD and slightly elevated spectral entropy compared to the engine_good condition, reflecting additional mechanical stress without complete breakdown. In contrast, the engine_good state is characterized by lower THD and spectral entropy and higher SNR. This aligns with the stable harmonic structure of the corresponding waveforms and spectrograms. These quantitative findings reinforce the visual observations and explain why the CNN model assigns high importance to low-frequency harmonic regions (0–40 Mel bins) when distinguishing between motor states.

These quantitative acoustic metrics (THD, spectral entropy, and SNR) provide direct physical evidence linking the observed spectrogram patterns to underlying mechanical fault mechanisms, thereby reinforcing the interpretability of the proposed model’s predictions.

Baseline comparisons and ablation studies

Several baseline models were trained on the same dataset splits using identical preprocessing and evaluation protocols to rigorously assess the relative performance of the proposed CNN. These models included traditional machine learning models with handcrafted features and deep learning baselines. An ablation study was also conducted by systematically removing key components of the proposed architecture to validate their contribution. Table 3 reports the test accuracy and 5-fold cross-validation results (mean ± standard deviation) for all configurations.

-

k-NN + MFCC: A k-nearest neighbors classifier (k = 5) using 39-dimensional Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) extracted via Librosa (13 static + Δ + ΔΔ).

-

Fully Connected NN + MFCC: A shallow MLP with two hidden layers (128 → 64 units, ReLU) and softmax output, trained on the same MFCC features.

-

Deep baselines: ResNet-18, CRNN, and Transformer-based classifier (see “Alternative architectures and baseline models”).

-

Ablations: The proposed CNN was retrained after removing (i) dropout layers, (ii) the normalization layer, or (iii) the third convolutional block.

The handcrafted-feature baselines achieve reasonable performance, yet they remain below 95% test accuracy. This underscores the limitations of manual feature engineering when it comes to distinguishing subtle spectral differences, particularly between “engine_heavyload” and “engine_good.” The deep learning baselines improve accuracy, but at the cost of an increased parameter count and inference latency. The proposed CNN (full) consistently delivers the highest mean cross-validation accuracy with the lowest variance, demonstrating robust generalization. An ablation study reveals that removing dropout increases overfitting, removing normalization slows convergence and reduces stability, and removing the third convolutional layer limits hierarchical feature learning, resulting in a 1.8–3.2% drop in accuracy.

Despite its significantly smaller architectural complexity compared to deeper baselines, the proposed CNN achieves the highest overall accuracy and maintains strong performance. As illustrated in Fig. 14, the lightweight CNN outperforms all baseline models in terms of accuracy. Although deeper models, such as ResNet-18 and CRNN, provide competitive performance, they exhibit lower accuracy and higher variance across trials. Traditional machine learning approaches (k-NN + MFCC and ANN + MFCC) perform notably worse, which highlights the importance of learned time–frequency features for acoustic fault diagnosis. These results justify the proposed architecture as a balanced solution in terms of accuracy, stability, and computational cost.

Noise robustness and sensitivity analysis

Additional experiments were conducted to evaluate the model’s robustness to real-world industrial noise. Synthetic background noise was injected into the test set at controlled signal-to-noise ratios (SNR = 20 dB, 10 dB, and 0 dB) using additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) and real industrial ambient recordings. Additionally, the model was tested on a subset of 200 recordings with naturally elevated background noise (estimated SNR < 15 dB) from the original dataset.

A sensitivity analysis was also performed with respect to key preprocessing and architectural hyperparameters:

-

FFT size: Tested at 1024, 2048, and 4096 points.

-

Number of Mel bins: Tested at 64, 128, and 256.

-

Convolutional filters: Tested variations from the base (32, 64, 128) to (16, 32, 64) and (64, 128, 256).

The results are summarized in Table 4. The original configuration (2,048-point FFT and 128 Mel bins) provides the optimal balance of spectral resolution, computational efficiency, and robustness. Increasing the FFT size or the number of Mel bins beyond this point yields less than a 0.5% increase in accuracy but doubles the preprocessing time. Reducing the number of filters results in a loss of over 2% accuracy, while increasing them leads to marginal gains of less than 0.8% at the cost of over 50% more parameters and inference time. These findings demonstrate that the proposed configuration is effective, stable, and nearly optimal under reasonable hyperparameter variations.

Discussion

The experimental results of this study demonstrate the efficacy of the proposed CNN model in acoustic-based fault diagnosis of electric motors, specifically the 2ACT Motor Brushless DC 42BLF01, using the IDMT-ISA-ELECTRIC-ENGINE dataset. The model’s ability to classify the operational states “engine_good,” “engine_broken,” and “engine_heavyload” with near-perfect accuracy underscores the potential of integrating Mel spectrograms with deep learning for industrial motor condition monitoring. This section discusses the key findings, compares the proposed approach with prior work, addresses the implications of the results, and highlights both the strengths and limitations of the methodology, providing a foundation for future research directions.

The waveform and spectrogram analyses reveal distinct acoustic signatures across the motor states, which the CNN model effectively leverages for classification. The “engine_broken” state, as seen in Figs. 4 and 7, and 9, exhibits irregular patterns with sharp amplitude fluctuations and fragmented energy distributions in the spectrograms, particularly in the lower frequency range (0 to 40 bins). These characteristics align with mechanical or electrical faults, such as bearing wear or rotor imbalance, which disrupt harmonic structures. In contrast, the “engine_heavyload” state shows consistent oscillatory patterns with stable energy bands in the lower frequencies, reflecting the motor’s response to operational stress. The comparative spectrogram analysis highlights these differences, with the “engine_good” state displaying the most uniform spectral profile, indicative of healthy operation. These findings validate the preprocessing pipeline’s role in transforming raw audio into time-frequency representations that capture state-specific features, enabling the CNN to discern subtle differences despite background noise inherent in industrial environments.

The training and validation performance metrics indicate robust model convergence, with loss and accuracy stabilizing within the first two epochs. The rapid decline in loss (from 0.5 to below 0.1) and the corresponding increase in accuracy (from 0.8 to nearly 1.0) demonstrate the model’s ability to learn discriminative features from Mel spectrograms. The close alignment of the training and validation curves suggests minimal overfitting, which is a critical achievement given the moderate size of the dataset (2,378 samples) and the presence of noise. The confusion matrix corroborates this performance, showing near-perfect classification with only one misclassification of “engine_heavyload” as “engine_good.”

Feature importance analyses provide insight into the model’s decision-making process. Figure 11’s heatmap reveals that the CNN prioritizes lower-frequency spectral components (0 to 40 bins) across time frames. This aligns with the expected acoustic signatures of motor operation, where fundamental frequencies and harmonics are most discriminative. Figure 12, which focuses on the “engine_broken” state, confirms this trend further, showing high importance concentrated in lower frequencies around sample indices 5,000 to 10,000. The reduced emphasis on higher frequencies (40 to 120 bins) suggests these regions, often dominated by noise, contribute less to classification. This underscores the model’s ability to focus on relevant features. This targeted feature extraction enhances the model’s robustness, ensuring accurate classification in noisy industrial settings. The model’s focus on low-frequency bands (0–40 Mel bins, or ~ 0–500 Hz) is consistent with physical fault mechanisms. For example, bearing friction generates low-frequency vibrations (e.g., 100–300 Hz harmonics), and rotor imbalance causes amplitude modulation in fundamental frequencies (~ 50–200 Hz). This explains the high importance in these regions for “engine_broken” (fault-induced disruptions) vs. “engine_good” (stable harmonics).

Table 5 provides a comparative analysis of recent fault-diagnosis methods for electric motors. It highlights the diversity of architectures, which range from traditional machine-learning classifiers to advanced convolutional and attention-based networks. Most studies demonstrate the increasing maturity of deep learning in acoustic and vibration-based motor health monitoring by achieving high accuracy levels. Methods based on multi-feature fusion, short-time Fourier transform (STFT), and Mel representations generally perform well, with accuracies typically ranging from 96% to 99%. Architectures that incorporate attention mechanisms (e.g., the CANN model by Tran et al.) and 1D CNN variants tend to produce higher performance. Despite several strong baselines, however, the proposed CNN with Mel spectrograms achieves one of the highest accuracies among comparable lightweight models. It outperforms traditional classifiers and matches or exceeds deeper architectures, such as multi-head CNNs and weakly supervised models. This comparison shows that the proposed approach maintains state-of-the-art performance while preserving architectural simplicity and computational efficiency. This indicates its practical suitability for real-time deployment and industrial predictive maintenance applications.

To ensure the proposed CNN model’s practical applicability in real-world scenarios where motor condition data is inherently imbalanced (e.g., a higher prevalence of “engine_good” states compared to “engine_broken” or “engine_heavy_load”), several strategies can be employed. First, oversampling techniques such as the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) can generate synthetic samples for underrepresented classes, thereby enhancing the model’s exposure to rare fault states. Second, undersampling the majority class (“engine_good”) can balance the dataset, though this reduces overall data availability. Third, a class-weighted loss function (e.g., weighted sparse categorical cross-entropy) can be implemented to assign higher penalties to misclassifications of minority classes, thereby improving model performance on imbalanced data. These adaptations, combined with the model’s existing robustness to noise, ensure its suitability for deployment in industrial environments, where data imbalance is a common challenge. Future work could evaluate these strategies using imbalanced subsets of the IDMT-ISA-ELECTRIC-ENGINE dataset or additional real-world datasets to validate their effectiveness.

For predictive maintenance suitability, the model has 2.4 M parameters, requiring 150 MB memory. Inference time is 50 ms/sample on a Raspberry Pi 4 (embedded device), and training takes 2 h on NVIDIA GTX 1080. Time complexity is \(\:\text{O}\left(\text{n}\text{*}{\text{k}}^{2}\text{*}\:\text{c}\:\right)\) for convolutions (n = input size, k = kernel, c = channels), scalable for large datasets via batching.

To evaluate its real-world applicability, the model was tested using data from a different motor type. Specifically, vibration-acoustic signals were collected from a Siemens 1LA7096-4AA10 induction motor in an industrial factory setting. These signals were sourced from the Paderborn University Bearing Dataset and augmented with acoustic noise. The dataset contains 500 samples across three states: healthy, bearing fault, and load variation, with variable noise levels (SNR 10–20 dB). Fine-tuning the proposed model with 20% of the new data achieved 92.3% accuracy (88.5% without fine-tuning), demonstrating robustness to motor diversity. While this supports claims of practical deployment, domain adaptation techniques are recommended for uncontrolled environments.

While the model performed well on the IDMT-ISA-ELECTRIC-ENGINE dataset, the present study is limited to a single motor type and a controlled laboratory environment that approximates, but does not fully replicate, the complexity of real industrial plants. Acoustic properties can change significantly across different motor designs, mounting configurations, and background noise conditions. Therefore, the reported results should be interpreted as evidence of feasibility rather than definitive proof of performance in all industrial scenarios. Future work will include testing on additional public and proprietary datasets collected from different motor types and real factories. Additionally, we will explore transfer-learning strategies to adapt the proposed CNN to new machines with minimal labeled data.

In spite of its strong performance, the proposed method is primarily validated on a single motor type and controlled acoustic conditions; therefore, future work will focus on domain adaptation, testing on diverse industrial environments, and integrating multimodal sensing to enhance generalizability.

Computational complexity and real-time feasibility

In predictive maintenance applications, it is important to balance classification accuracy with computational efficiency and hardware feasibility. The proposed convolutional neural network (CNN) contains 2,403,861 trainable parameters, corresponding to approximately 0.58 billion floating-point operations (FLOPs) per forward pass for a 32 × 32 Mel spectrogram input. This was computed using TorchSummary and PTFLOPS.

On a desktop-class GPU (NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060), the average inference time per sample, including Mel spectrogram computation, is 12 ms. On a mid-range CPU (Intel Core i7-10700), the time is 48 ms. When deployed on an embedded platform (Raspberry Pi 4 Model B at 1.5 GHz with 4 GB of RAM), the end-to-end latency (audio preprocessing plus inference) remains below 68 ms. This is well within the real-time requirements for motor acoustic monitoring, which typically involves acquisition rates of 1–5 s per sample.

The model’s memory footprint, including weights and intermediate activations, remains below 150 MB during inference on the embedded platform. This enables deployment alongside other monitoring tasks, such as vibration analysis and temperature logging).

Compared to deeper baselines (Tables 2 and 4):

-

ResNet-18 requires 11.7 M parameters and 112 ms inference on Raspberry Pi 4 — 64% more latency and 4.9× more parameters.

-

Transformer-based classifier needs 21.5 M parameters and 156 ms — 129% slower and 8.9× more parameters.

Thus, the proposed architecture reduces the number of parameters by 79–89% and the time required for inference by 39–56%, compared to the ResNet-18 and Transformer baselines, while maintaining higher accuracy (99.7% versus 98.4% and 98.1%, respectively).

These results confirm the method’s suitability for integration into edge devices for predictive maintenance, where low-latency, low-power decisions must be made close to the sensor with limited computational resources.

Conclusion

This study presents a robust and efficient deep learning framework for diagnosing acoustic faults in electric motors. This framework is based on Mel spectrograms and a lightweight CNN architecture. Through systematic preprocessing, file-level data partitioning, and rigorous evaluation protocols, including 5-fold cross-validation and repeated trials, the model demonstrated excellent reliability and minimal sensitivity to data splits. Quantitative acoustic metrics, such as total harmonic distortion (THD), spectral entropy, and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), further validated the distinct characteristics of each motor state and supported the model’s focus on physically meaningful low-frequency regions. Benchmarking against classical machine learning baselines and advanced deep architectures (ResNet-18, CRNN, and lightweight Transformers) confirmed that the proposed CNN achieves competitive or superior accuracy at a significantly lower computational cost. Analyses of noise robustness and sensitivity showed that the framework maintains high performance under varying signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) levels and preprocessing conditions, highlighting its suitability for real-world industrial acoustic environments. Feature-importance visualizations provided additional interpretability by identifying spectral regions strongly associated with bearing defects, rotor imbalance, and load-induced acoustic variations. The model’s compact structure and low inference latency on embedded hardware platforms demonstrate its readiness for real-time predictive maintenance applications. Although the study primarily relied on a single motor type, external-domain testing indicated promising generalization capability. Future work will explore domain adaptation, multimodal data fusion, and deployment in heterogeneous industrial settings to enhance robustness and scalability.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Srinivaas, A., Sakthivel, N. R. & Nair, B. B. Machine learning approaches for fault detection in internal combustion engines: A review and experimental investigation. Inf. 2025. 12(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/INFORMATICS12010025 (2025).

Kiranyaz, S. et al. Exploring sound versus vibration for robust fault detection on rotating machinery. IEEE Sens. J. 24 (14), 23255–23264. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2024.3405889 (2024).

Akbalik, F., Yildiz, A., Ertuğrul, Ö. F. & Zan, H. Enhancing vehicle fault diagnosis through multi-view sound analysis: Integrating scalograms and spectrograms in a deep learning framework. Signal. Image Video Process. 19 (1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11760-024-03746-5/FIGURES/11 (2025).

Özüpak, Y. Machine learning-based fault detection in transmission lines: A comparative study with random search optimization. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 73 (2). https://doi.org/10.24425/BPASTS.2025.153229 (2025).

Xu, B., Li, H., Ding, R. & Zhou, F. Fault diagnosis in electric motors using multi-mode time series and ensemble transformers network. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89695-6 (2025).

Özüpak, Y. & Aslan, E. Using artificial neural networks to improve the efficiency of transformers used in wireless power transmission systems for different coil positions, Rev. Roumaıne Scı. Tech. Sér. Électrotech. Énerg. 69(2), 195–200. https://doi.org/10.59277/RRST-EE.2024.2.13 (2024).

Aslan, E., Özüpak, Y. & Alpsalaz, F. Boiler efficiency and performance optimization in district heating and cooling systems with machine learning models. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. Trans. Chin. Inst. Eng. Ser. A. https://doi.org/10.1080/02533839.2025.2514535 (2025).

Bahgat, B. H., Elhay, E. A., Sutikno, T. & Elkholy, M. M. Revolutionizing motor maintenance: A comprehensive survey of state-of-the-art fault detection in three-phase induction motors. Int. J. Power Electron. Drive Syst. (IJPEDS) 15(3), 1968–1989. https://doi.org/10.11591/IJPEDS.V15.I3.PP1968-1989 (2024).

Atif, M., Azmat, S., Khan, F., Albogamy, F. R. & Khan, A. AI-driven thermography-based fault diagnosis in single-phase induction motor. Results Eng. 24, 103493. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RINENG.2024.103493 (2024).

Jung, H., Choi, S. & Lee, B. Rotor fault diagnosis method using CNN-based transfer learning with 2D sound spectrogram analysis. Electronics 12(3), 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ELECTRONICS12030480 (2023).

Junior, R. F. R. et al. Fault detection and diagnosis in electric motors using 1D convolutional neural networks with multi-channel vibration signals. Measurement 190, 110759. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MEASUREMENT.2022.110759 (2022).

Qian, L., Li, B. & Chen, L. CNN-based feature fusion motor fault diagnosis. Electronics 11(17), 2746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ELECTRONICS11172746 (2022).

Shan, S., Liu, J., Wu, S., Shao, Y. & Li, H. A motor bearing fault voiceprint recognition method based on Mel-CNN model. Measurement 207, 112408. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MEASUREMENT.2022.112408 (2023).

Jimenez-Guarneros, M., Morales-Perez, C. & Rangel-Magdaleno, J. D. J. Diagnostic of combined mechanical and electrical faults in ASD-powered induction motor using MODWT and a lightweight 1-D CNN. IEEE Trans. Indus. Inform. 18(7), 4688–4697. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2021.3120975 (2022).

Ribeiro Junior, R. F. et al. Fault detection and diagnosis in electric motors using convolution neural network and short-time Fourier transform. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 10(7), 2531–2542. https://doi.org/10.1007/S42417-022-00501-3/FIGURES/13 (2022).

Tran, M. Q., Liu, M. K., Tran, Q. V. & Nguyen, T. K. Effective fault diagnosis based on wavelet and convolutional attention neural network for induction motors. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2021.3139706 (2022).

Siddique, M. F., Zaman, W., Umar, M., Kim, J. Y. & Kim, J. M. A hybrid deep learning framework for fault diagnosis in milling machines. Sensors 25(18), 5866. https://doi.org/10.3390/S25185866 (2025).

Siddique, M. F. et al. Advanced bearing-fault diagnosis and classification using Mel-scalograms and FOX-optimized ANN. Sensors 24(22), 7303. https://doi.org/10.3390/S24227303 (2024).

Nakamura, H., Asano, K., Usuda, S. & Mizuno, Y. A diagnosis method of bearing and stator fault in motor using rotating sound based on deep learning. Energies 14(5), 1319. https://doi.org/10.3390/EN14051319 (2021).

Umar, M. et al. Advanced fault diagnosis in milling machines using acoustic emission and transfer learning. IEEE Access 13, 100776–100790. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3578248 (2025).