Abstract

This study investigates the influence of new tunnel construction which traverses above existing shield tunnels on the vertical displacement behavior in complex strata. Through the introduction of state vectors for soil layers, the displacement and stress propagation between different strata are formulated via integral transforms and matrix derivation. The layered characteristics of natural soils are effectively captured, and an extended Mindlin solution applicable to layered ground conditions is established.The existing tunnel is formulated as a Timoshenko beam interacting with a Pasternak foundation. By introducing a reduction factor for segmental joints and soil–tunnel coupling parameters, a governing equation for longitudinal displacement incorporating stiffness degradation is established and numerically solved using the finite difference method.Comparative analyses were conducted against traditional Euler–Bernoulli–Winkler models, with validation was performed using field monitoring data and finite element analysis (FEA) results. Conventional soil–tunnel interaction models based on the Mindlin solution tend to overestimate the vertical displacement of existing tunnels in layered foundations. In contrast, the proposed approach yields predictions with smaller errors. Validation against measured data shows that the proposed method reduces the prediction error for maximum displacement from 0.54 mm (conventional method) to 0.20 mm. Overall, the Timoshenko–Pasternak model, integrated with the elastic layered theory, provides more accurate predictions of existing tunnel deformation in layered strata compared to traditional beam–foundation combination models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increasingly three-dimensional and networked development of urban underground space, the shield tunneling method has become one of the core construction techniques for underground engineering projects such as subways and utility tunnels, due to its high efficiency and minimal disturbance to the ground conditions1,2,3. However, the disturbance of surrounding soils induced by new shield tunnel excavation alters the stress state of the ground around existing tunnels, leading to tunnel bending and dislocation. Such deformations pose potential risks to the long-term safety and serviceability of existing tunnels. Excessive bending or dislocation can threaten structural integrity and may even result in longitudinal differential settlement4,5,6,7, water leakage, and other hazards. Therefore, investigating these engineering problems has substantial practical importance8,9.

At present, research methods for studying the influence of shield tunnel construction on existing tunnels primarily include model tests, numerical simulations, and theoretical analyses. In the area of model testing, Huang et al.10, taking the Shanghai Bund Passage shield tunnel project overcrossing Metro Line 2 as a case study, conducted centrifuge model tests to simulate the processes of shield excavation, ground loss, and grouting, examining the displacement effects of new tunnel construction on existing tunnels and ground surfaces in soft soil regions. Similarly, Vorster et al.11 investigated the influence of tunnel construction in soft ground on the bending moments of buried pipelines through centrifuge model experiments.

In the field of numerical simulation, Wei et al.12 used Midas GTS NX to establish a detailed three-ring segment model of an existing tunnel. By applying circumferential ground pressure calculated using an improved approach, they simulated a shield tunnel undercrossing. Their study analyzed the effects of ground loss rate and tunnel spacing on the surrounding pressure and convergence of the existing tunnel and compared the differences between three-ring and single-ring segment models. Dai et al.13 combined field monitoring and numerical simulation to investigate the deformation impacts of ultra-close undercrossing on existing tunnel structures, such as lining, bottom slab, and side wall. Zhang et al.14 developed a finite element model using FLAC3D to simulate the influence of different grouting pressures on surface displacement. This method effectively represents soil stratification and accurately simulates tunnel–soil interaction under complex construction conditions.

Regarding theoretical analyses, the two-stage simplified method is most commonly adopted15,16,17. This approach first determines the ground response without considering the tunnel structure and then applies this response to the tunnel. However, in these solutions, the ground response is usually obtained from the Mindlin solution, which assumes the soil as a homogeneous elastic medium, thereby neglecting its stratified characteristics. In practical engineering, foundation soils typically exhibit distinct layering, with significant variations in physical and mechanical properties among layers at different depths. Treating them as a homogeneous medium may lead to significant errors. Within the framework of the two-stage method, the Euler–Bernoulli beam combined with a Winkler foundation model (EB–W model) has been widely used to derive analytical solutions for tunnel–soil interaction problems18,19,20,21. However, the Winkler foundation model neglects the continuity of the ground. To overcome this limitation, Huang et al.22 and Ataman23 introduced the Pasternak and Vlasov foundation models, respectively, to account for soil continuity effects. They derived analytical formulas for the vertical displacement of existing tunnels due to an overcrossing shield tunnel using differential equations. However, in their solutions, the shield tunnel was still idealized as an Euler–Bernoulli beam. This beam model only considers longitudinal bending stiffness, and in practice, segmental tunnel linings exhibit joint flexibility, resulting in an overall reduction in stiffness. To better capture the actual mechanical behavior of existing tunnels, this study adopts the tunnel as a Timoshenko24 beam that simultaneously accounts for both bending and shear.

In summary, most existing methods for predicting the longitudinal response of existing tunnels induced by new overcrossing shield tunnel excavation have inherent limitations, especially in addressing soil stratification, tunnel joint flexibility, and soil continuity. To mitigate these drawbacks, the main contributions of this study are threefold: Adopting an extended Mindlin solution derived via the transfer matrix method to accurately characterize ground disturbance in elastic layered strata; Modeling the existing tunnel as a Timoshenko beam on a Pasternak foundation (T–P model), which effectively accounts for both shear deformation and soil continuity; Incorporating a stiffness reduction factor to quantitatively reflect the flexibility of segmental joints. These improvements are intended to develop a more precise and practical analytical tool for preliminary engineering assessments. Based on these innovative insights, the proposed analytical method is validated using field monitoring data and FEA results from an engineering case study. Additionally, a parametric study is conducted to explore the impacts of key parameters on the longitudinal response of the existing tunnel.

Fundamental solution for shield tunneling in a layered ground

In practical engineering, the ground strata are typically stratified, and significant errors often arise when using the classical Mindlin solution. Ai et al.25 referred to the elastic mechanics problem of the stress and displacement fields induced by a concentrated load in layered strata as the ‘extended Mindlin solution’. The extension from the classical homogeneous Mindlin solution to a layered system is achieved by satisfying stress and displacement continuity at each layer interface through the transfer matrix method, coupled with integral transforms. This enables the solution to account for variations in soil mechanical parameters with depth.Based on the elastic layered theory and the transfer matrix method, they derived a practical form of this extended Mindlin solution.

Based on the fundamental assumptions of the elastic layered half-space theory:

-

1.

The ground is composed of n horizontal layers, each considered a homogeneous and isotropic elastic medium.

-

2.

Stresses and displacements are continuous across the interfaces between adjacent layers.

-

3.

Each layer has its own elastic modulus Ei, Poisson’s ratio ui, and thickness Δhi.

-

4.

The external load is applied within the m-th layer (as illustrated in Fig. 1), where the distance from the loading point to the ground surface is hm1.

-

5.

The shield tunneling process is simplified as a concentrated load (Q) acting at a single point.

Ai et al.25 derived the fundamental solution functions for a single-layer foundation subjected to non-axisymmetric loading (Eqs. (1) and (2)); they introduced the intermediate parameters \(\:{u}_{v}\), \(\:{u}_{h}\), \(\:{\tau\:}_{vz}\), and \(\:{\tau\:}_{hz}\) (detailed in Eq. (3)) and expressed the displacements and stresses in series form.

where \(\varvec{\Psi}\)and \({\varvec{T}}\)denote transfer matrices.

By applying the Hankel transform26 to simplify Eqs. (4) and (5), the fundamental equations of elasticity yield the recursive expressions and transfer matrices for the displacement and stress fields in an elastic half-space, as shown in Eqs. (5) and (6).

It is assumed that the soil layer is partitioned by n interfaces during calculation, and the contact conditions of each interface are subjected to Hankel Transform. If a horizontal force Q acts on the m-th interface, the interface contact conditions can be formulated as shown in Eq. (8):

Based on the recursive equations between interfaces, the multi-layer recursive formulas can be deduced, as given in Eqs. (8) and (9):

The results of Eqs. (8) and (9) need to undergo the inverse Hankel Transform to yield the final solution, as expressed in Eq. (10):

Calculation of vertical displacement of existing tunnel based on Pasternak-Timoshenko beam model

Analysis of existing tunnel model

Shield tunnels are constructed from prefabricated segmental rings, and the shear at the joints between adjacent rings cannot be neglected when analyzing their longitudinal response. The conventional Euler–Bernoulli beam model assumes zero shear deformation and therefore considers only bending stiffness, which typically underestimates the resulting deflection. This study adopts the Timoshenko beam theory to more accurately capture the longitudinal internal forces, displacements, and shear stiffness at the segmental joints of shield tunnels. According to the Timoshenko beam theory, the cross-section of the beam remains perpendicular to the neutral axis before deformation but becomes inclined after deformation due to shear effects, as illustrated schematically in Fig. 2.

According to the Timoshenko beam theory, the governing equations for internal forces and deformations can be expressed as:

In this equation, F denotes the shear force, M represents the bending moment,\(w\) is the deflection of the beam’s neutral axis, and \(\theta\) is the shear angle. The equivalent shear and bending stiffnesses of the existing tunnel, denoted by \({G_{{\text{eq}}}}\)and (EI)eq, respectively, are determined following the approach described in27.

In the equation:\({K_{\text{f}}}\)is the rotational stiffness coefficient of the circumferential joint;\({E_{\text{c}}}\)is the elastic modulus of the segment;\(I\) is the moment of inertia of the tunnel cross-section;\(\lambda\)is the joint influence coefficient;\({l_{\text{s}}}\)is the length of the shield tunnel segment;\({l_{\text{f}}}\)is the bolt length;\(\zeta\)is the reduction coefficient of the tunnel’s bending stiffness (typically ranging from 1/5 to 1/7);\(\xi\)is a correction coefficient introduced to account for the actual contact conditions between shield segments (taken as 1 in the following analysis);n denotes the number of longitudinal bolts;\({\kappa _{\text{b}}}\)and\({\kappa _{\text{c}}}\)are the Timoshenko shear coefficients for the bolts and the shield segments, respectively (taken as 0.9 and 0.5);\({G_{\text{b}}}\)and\({G_{\text{c}}}\)are the shear moduli of the bolts and the segments, respectively;

\({A_{\text{b}}}\)and\({A_{\text{c}}}\) represent the cross-sectional areas of the bolts and the segments, respectively.

The relative displacement between segments due to shear, denoted as\(\delta\), is calculated using Eq. (15).

Foundation model analysis

Compared with the Winkler foundation model, the Pasternak foundation model introduces an additional shear layer with shear modulus Gp in addition to the spring layer represented in the Winkler model. This enhancement enables consideration of the interaction between adjacent soil springs, thus improving the accuracy of foundation deformation predictions, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

The governing expression is given as:

In the equation: Wz(x) represents the subgrade reaction; k is the coefficient of subgrade reaction; and wz(x) denotes the vertical displacement of the existing tunnel.

The value of k can be determined according to the method proposed by Liang et al.28.

In the equation:Es is the elastic modulus of the soil at the location of the existing tunnel.

The shear layer stiffness Gp can be determined using the method proposed by Tanahashi et al.29:

In the equation: Hp is the thickness of the shear layer of the Pasternak foundation, which can be assumed to be 2.5 times the diameter of the existing tunnel.

Analysis of the coupled interaction between soil and existing tunnel

A differential element is taken from the existing tunnel for force analysis Fig.4 . By establishing the equilibrium differential equations for this element and performing appropriate simplifications, Eq. (19) can be obtained.

By substituting Eqs. (11), (12) and (17) into Eq. (19), the equilibrium differential equation governing the existing tunnel is obtained:

By solving Eq. (20), the governing equation for the existing tunnel’s vertical displacement wz(x) is obtained:

In the equation:\(\beta ={G_{{\text{eq}}}}+{G_p}D\); and\({\sigma _z}(x)\)represents the additional load induced by the construction of the new tunnel, expressed as:\({\sigma _z}(x)=k{u_z}(x) - {G_\text{p}}\frac{{{\text{d}^2}{u_z}(x)}}{{\text{d}{x^2}}}\).

Solution of the governing equation for the existing tunnel

Equation (20) can be numerically solved using the finite difference method. The existing tunnel is discretized into +5 nodal elements, each with a length of , among which four are virtual elements introduced to handle the boundary conditions, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

According to the finite difference principle, the differential terms in Eq. (20) can be expressed in their finite difference forms as follows:

where \({w_i}\)denotes the vertical displacement of the tunnel at the -th node, and \({\sigma _i}\)represents the additional stress at the -th node.

Assuming both ends of the tunnel are free boundaries, the bending moment and shear force at both ends are taken to be zero:

By simultaneously combining Eqs. (8), (9), (18), and (21), the expressions for the four virtual nodes can be obtained as follows:

For ease of expression, Eqs. (22) and (24) are substituted into Eq. (21) and rearranged into the following matrix form::

Where \({\varvec{w}}\)is the column vector of the vertical displacements of the existing tunnel; \({{\varvec{K}}_1}\),\({{\varvec{K}}_2}\)and\({{\varvec{K}}_3}\) are the coefficient matrices corresponding to the displacement vector\({\varvec{w}}\); and \({{\varvec{F}}_1}\),\({{\varvec{F}}_2}\) and\({{\varvec{F}}_3}\) are the column vectors of additional stresses.

Case study verification and parametric analysis

Case study verification

Case study 1

An analysis was conducted on the “Xin–Ji” interval of Wuhan Metro Line 5, where the new tunnel overcrosses the existing Line 2 tunnel. The new tunnel is entirely located within a silty clay layer, while the existing tunnel lies in a silty fine sand layer, with the two tunnels intersecting vertically. The physical and mechanical parameters of the soil layers in this interval are summarized in Table 1. The axis depth of the new tunnel is 17.5 m, with an external diameter of the segment of 6.20 m and a segment thickness of 0.35 m. During construction, the thrust pressure at the excavation face was set to 465 kPa. The existing tunnel has an axis depth of 29.1 m; the segment lining has an elastic modulus of 3.45 × 104MPa, a density of 2.5 × 103kg/m3, and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.2. Each ring consists of six segments. The connecting bolts have an elastic modulus of 2.06 × 105MPa, a diameter of 30 mm, and a shear modulus of 8.24 × 104MPa.According to the results obtained from Eqs. (13) and (14), the equivalent flexural stiffness of the existing tunnel is calculated as 1.38 × 108kN·m², and the equivalent shear stiffness is 3.39 × 106kN/m.

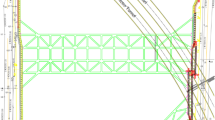

In this study, the finite element software Midas GTS NX was employed to perform the numerical simulations. The soil was modeled using the Mohr–Coulomb constitutive model. To minimize boundary effects, the soil domain was defined with dimensions of 80 m×60 m×50 m. The new tunnel segments, the existing tunnel, and the grouting layer were modeled as isotropic linear elastic materials. The shield shell was represented using two-dimensional elastic plate elements. The established three-dimensional finite element model is shown in Fig. 6.

The tunnel displacements obtained from different calculation methods and field measurements are shown in Fig. 7. All curves are symmetrical about the crossing center and exhibit a bell-shaped distribution, indicating that under orthogonal crossing conditions, the ground disturbance is most pronounced at the crossing center and rapidly attenuates with increasing transverse distance. The maximum heave value predicted by the EB-W model based on the Mindlin solution is 4.17 mm, which is approximately 14.8% higher than the measured value of 3.63 mm, indicating a noticeable overestimation.In contrast, the T-P model, which accounts for shear deformation between segment rings, reduces the soil displacement field through the coupling between the tunnel and the shear layer of the Pasternak foundation, while also considering the modification of displacement transmission in the layered strata. This mechanism effectively suppresses tunnel heave. The maximum heave predicted by the proposed method is 3.83 mm, with a relative error of 4.7% compared to the measured value, representing a 9.4% improvement in prediction accuracy. Furthermore, the shape of the predicted curve agrees well with the monitoring data, confirming the effectiveness of the proposed method.

The results of the numerical simulation also show good agreement with the monitoring values in both trend and spatial distribution of the tunnel heave. However, the maximum simulated heave (3.4 mm) is slightly lower than the measured value by approximately 7%, primarily due to the idealized representation of soil parameters and boundary conditions in the finite element model. In contrast, the theoretical solution generally predicts larger heave values because the equivalent flexural stiffness (EI)eq does not fully capture the actual flexural stiffness. Nevertheless, this conservative estimation can help reduce construction risks.

Overall, the longitudinal displacement curves obtained from both the theoretical analysis and the numerical simulation exhibit consistent shapes, further confirming the validity of the proposed method and the reliability of the calculation results.

Case study 2

During the construction of the section between Xujiahui Station and Shanghai Stadium Station on Shanghai Metro Line 11, the tunnels sequentially underpassed the operational Line 4 beneath Lingling Road. The upbound tunnel was excavated about 120 rings ahead of the downbound tunnel. This study focuses on the influence of the Line 11 upbound excavation on the existing Line 4 tunnel. The site consists of eight soil layers, with detailed parameters listed in Table 2. The Line 4 tunnel has an outer diameter of 6.2 m, an inner diameter of 5.5 m, an elastic modulus of 3.02 × 10⁴ MPa, and a burial depth of 17.12 m. The Line 11 upbound tunnel shares the same dimensions and mechanical properties, with its axis located at a depth of 21.02 m. To validate the proposed method, the computed results are compared with field monitoring data. As shown in Fig. 10, the predicted settlement of the Line 4 downbound tunnel agrees well with the observed values.

As shown in the figure, the distribution of the calculated curves agrees well with that of the field-measurement results. Among them, in the crossing area of Line 11, most calculated values are larger than the measured results. The reason is that the algorithm in this paper does not consider the influence of shield grouting, Fig.8 which will be further taken into consideration in subsequent research.

Analysis of different parameter influences

To further investigate the influence of various factors on the response of adjacent shield tunnels using the proposed method, this study analyzes the effects of different parameters. These parameters include the clear distance between the new and existing tunnels, the horizontal projection angle, and the stratification of the ground on the existing tunnel.

Analysis of the influence of horizontal projection angle

The horizontal projection angles (α) between the new and existing tunnels are set to 30°, 45°, 60°, and 75° for comparison with the orthogonal case (α = 90°). The longitudinal uplift curves of the existing tunnel during the excavation of the new tunnel, corresponding to different α values, are shown in Fig. 9a. The results indicate that as α decreases, the minimum distance between the axes of the two tunnels becomes shorter, thereby enhancing the soil-tunnel interaction. This leads to an increase in uplift magnitude and a broader influence zone.

Figure 9b shows the variation of the maximum uplift with respect to α. Overall, as α increases from a parallel to an orthogonal orientation, the maximum uplift exhibits a decreasing trend, with a cumulative reduction of approximately 1.18 mm (24%). This trend can be divided into three stages: (1) a slow decrease in uplift when α increases from 0° to 15°, (2) a rapid decrease between 15° and 60°, and (3) a gradual slowdown in the rate of decrease from 60° to 90°. A similar trend was also reported by Lin et al.30 based on numerical simulations.

The aforementioned results indicate that when the horizontal projection angle between the new and existing tunnels is less than 60°, the heave deformation of the existing tunnel increases significantly and its influence zone expands. This is primarily because a smaller angle leads to an increased interaction length between the tunnels, resulting in a longer load transfer path and enhanced soil-tunnel interaction.Therefore, when site conditions allow, an orthogonal overcrossing is recommended to enhance the stability of the existing tunnel. In cases where oblique crossing is unavoidable due to practical constraints, maintaining a crossing angle greater than 60° is advisable to mitigate adverse effects on the existing structure.

Analysis of the influence of soil stratification

To investigate the influence of different soil layer configurations on the longitudinal displacement of the tunnel, this section extends the previous engineering case study. By varying the elastic moduli of the soil layers containing the new and existing tunnels, as well as that of the interlayer soil between them, three ground conditions are simulated: a homogeneous layer, and layered strata characterized as “soft-over-hard” and “hard-over-soft.” The elastic moduli of the different strata are listed in Table 3. Figure 10 presents a comparison of the calculated vertical displacements of the existing tunnel under different ground conditions.

Figure 10 compares the longitudinal displacement profiles of the existing tunnel under different stratum configurations. The analysis indicates that the maximum vertical displacement of the tunnel varies significantly with the stratum type: the maximum heave reaches 3.57 mm in the homogeneous ground, 3.25 mm in the upper-soft–lower-hard ground, and 3.01 mm in the hard-over-soft stratum. This difference is primarily attributed to the distribution of ground stiffness. The homogeneous ground exhibits the most pronounced deformation response due to its relatively low overall stiffness. In the hard-over-soft stratum, the tunnel heave is approximately 7.4% smaller than in the soft-over-hard condition, highlighting the significant influence of soil stiffness variation on tunnel deformation and stress response.

In addition, the spatial extent of the displacement also varies among different ground types. The soft-over-hard ground exhibits the smallest deformation influence zone, whereas the hard-over-soft ground shows the widest. This phenomenon arises from differences in stress transfer mechanisms within the ground. In the soft-over-hard stratum, stress is transferred directly through the soft soil to the underlying hard layer, causing stress concentration at the interface due to the abrupt stiffness contrast. Conversely, in the hard-over-soft stratum, the stiff upper layer redistributes the load to the surrounding soil through a “soil arching effect,” thereby reducing the peak stress at the base.

In engineering design, priority should be given to investigating stratum stiffness distribution, and simplifying inhomogeneous foundations as homogeneous models should be avoided. Otherwise, the actual deformation of the tunnel may be underestimated or overestimated, compromising construction design.

Influence of the clear distance between the new and existing tunnels

The minimum vertical clear distance between the new and existing tunnels is a key design parameter for controlling construction risk in overcrossing projects. In this section, only the clear distance is varied, with values set to 0.5D, D, 1.5D, 2D, and 2.5D (where D denotes the tunnel diameter), to investigate the longitudinal displacement profiles, maximum displacements, and bending moment distributions of the existing tunnel under different clear distance conditions.

As shown in Fig. 11(a), the vertical displacement of the existing tunnel near the centerline of the new tunnel increases markedly as the clear distance decreases, whereas the displacements farther from the crossing center gradually diminish. Beyond approximately 17.5 m from the intersection point of the new and existing tunnels, the deformations under different clear distance conditions tend to stabilize and remain small in magnitude. This indicates that the influence of clear distance variation on the existing tunnel is primarily confined to a limited zone around the crossing point.As illustrated in Fig. 11(b), when the clear distance decreases from 2.5D to 0.5D, the maximum heave of the existing tunnel increases by 42%, and the rate of displacement change accelerates with decreasing clear distance. Regarding the bending moment response, as the clear distance increases from 0.5D to 2.5D, the peak bending moment of the existing tunnel decreases by 66%, and the rate of reduction gradually diminishes at larger clear distances.

The results demonstrate that increasing the vertical clear distance can effectively mitigate the deformation and internal force responses of the existing tunnel induced by shield excavation. In engineering practice, appropriately increasing the design clear distance can significantly reduce ground disturbance, thereby mitigating the risk of structural deformation in the existing tunnel and enhancing operational safety.

Conclusion

Based on the extended Mindlin solution and the two‑stage method combined with the T–P model, this paper presents a continuous elastic analysis method for evaluating the longitudinal displacement of existing tunnels caused by shield‑tunnel overcrossing in inhomogeneous strata. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) A comparison of numerical results from Midas GTS NX with field monitoring data shows that the proposed method captures the displacement response of the existing tunnel during overcrossing more accurately than the conventional EB–W theoretical model based on the Mindlin solution. This indicates that the proposed approach can be effectively used for rapid preliminary assessment of shield‑construction impacts in early design stages, thus providing a theoretical basis for optimizing construction schemes.

(2) The elastic layered half‑space model used in this study shows better applicability under complex geological conditions. It overcomes the limitation of traditional homogeneous models, which tend to overestimate stress diffusion because they ignore the stratification of soil stiffness, thereby improving the rationality and accuracy of the results.

(3) Parametric analysis reveals that the horizontal projection angle between the new and existing tunnels has a nonlinear influence on the deformation response of the existing tunnel. A smaller crossing angle increases both the magnitude and the extent of heave deformation. Comparisons under different stratigraphic conditions show that a soft‑over‑stiff stratum tends to cause stress concentration, whereas a stiff‑over‑soft stratum promotes stress diffusion. Furthermore, as the clear distance between the tunnels decreases, the vertical displacement of the existing tunnel induced by overcrossing excavation increases significantly, while this effect weakens with increasing spacing.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Li, X. G. & Yuan, D. J. Response of a double-decked metro tunnel to shield driving of twin closely under-crossing tunnels.. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2011.08.005 (2012).

Liu, T. et al. Better Understanding the failure modes of tunnels excavated in the boulder-cobble mixed strata by distinct element method. Eng. Fail. Anal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2020.104712 (2020).

Liu, T. et al. New construction technology of a shallow tunnel in Boulder-Cobble mixed grounds. Adv. Civil Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5686042 (2020).

Huang, K. et al. Analysis of bearing capacity characteristics and resilience enhancement mechanism in shield tunnel segments based on fracture energy and modulus degradation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 167, 106952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2025.106952 (2026).

Lueprasert, P. et al. Numerical investigation of tunnel deformation due to adjacent loaded pile and pile-soil-tunnel interaction. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 70, 166–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2017.08.006 (2017).

Wu, X. et al. Experimental and numerical investigation of shield tunnel segments reinforced with grouted channel steel under diverse damage scenarios. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 170, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2025.107334 (2026).

Huang, K. et al. Flexural behavior of shield tunnel lining segments reinforced using grouted channel steel: experimental investigation. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 23, e04922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04922 (2025).

Guo, E. D. et al. Deformation analysis of high-speed railway CFG pile composite subgrade during shield tunnel underpassing. Structures 78, 109193 (2025).

Wang, M. & Lai, J. X. Mechanic performance of novel prefabricated inverted arch in natm tunnels: insights from numerical experiment and in-situ Tests inpress (Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology, 2026).

Huang, D. Z. et al. Centrifuge modelling of effects of shield tunnels on existing tunnels in soft clay. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 34(3), 520–527 (2012).

Vorster, A. Estimating the effects of tunneling on existing pipelines. J. Geotechnical. Geoenvironmental. Eng. 131(11), 1399–1410 (2005).

Wei, G. et al. Influence of confining pressure change caused by shield undercrossing on existing shield tunnels. Tunnel Construction,2025,45(4):7 08-718. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2025)131:11(1399).

Dai, Z. B. & Lu, Y. L. Influence of ultra-close undercrossing shield on deformation of existing tunnels. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 47 (10), 2154–2162. https://doi.org/10.11779/CJGE20241225 (2025).

Zhang, M. X. et al. Influence analysis of twin shield tunnels upward crossing on adjacent existing metro tunnels in completely weathered rock. China Civil Eng. J. 52(9), 100–108. https://doi.org/10.15951/j.tmgcxb.2019.09.008 (2019).

Tang, X. W. et al. Study on soil deformation during shield construction. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 29(2), 417–422 (2010).

Liang, R. Z. et al. Analysis of surface deformation and deep soil horizontal displacement caused by shield advancement. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 34(3), 583–593. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2015.03.016 (2015).

Lu, X. F. et al. Analysis of the influence of shield construction on the vertical displacement of overlying pipelines. J. Transp. Sci. Eng. 41(1), 41–50 (2025).

Klar, A. et al. Soil-pipe interaction due to tunnelling: comparison between Winkler and elastic continuum solutions. Géotechnique 55(6), 461–466 (2005).

Xu, Y. J. et al. Upheaval deformation induced by newly-built metro tunnel upcrossing existing tunne. China Railway Science 35(6), 48–54 (2014).

Liang, R. Z. et al. Effects of Above-crossing tunnelling on the existing shield tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 58, 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2016.05.002 (2016).

Molina-Villegas, J. C., Ballesteros Ortega, J. E. & Ruiz Cardona, D. Formulation of the green’s functions stiffness method for Euler–Bernoulli beams on elastic Winkler foundation with semi-rigid connections. Eng. Struct. 266, 114616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.114616 (2022).

Huang, M. H. & Zhou, Z. L. Analysis of explicit analytical solution for tunnel undercrossing existing pipelines in double-parameter foundation. J. Saf. Environ. 23(6), 1852–1858. https://doi.org/10.13637/j.issn.1009-6094.2021.2375 (2023).

ATAMAN M,Szcześniak, W. Influence of inertial Vlasov foundation parameters on the dynamic response of the Bernoulli-Euler beam subjected to A group of moving Forces-Analytical approach. Mater. (Basel). 15 (9), 3249. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15093249 (2022).

Yang, S. et al. Theoretical study on longitudinal deformation of adjacent tunnel subjected to pre-dewatering based on Pasternak-Timoshenko beam model. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 1114987. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.1114987 (2023).

Ai, Z. Y. & Yang, M. Extended Mindlin solution for a horizontal force acting inside a layered foundation. J. Tongji Univ. 28(3), 272–276 (2000).

Yu, L. et al. Discrete Hankel transform (In Chinese with english abstract). Chin. J. Comput. Phys. 1, 90–95 (1998).

Wu, H. N. et al. Longitudinal structural modelling of shield tunnels considering shearing dislocation between segmental rings. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 50, 317–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2015.08.001 (2015).

Liang, R. Z. et al. Analysis of longitudinal deformation of adjacent tunnels caused by foundation pit excavation considering tunnel shear effect. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 36(1), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2015.1585 (2017).

Tanahashi H. Formulas for an infinitely long bernoulli-euler beam on the Pasternak model. Soils Found. 44(5), 109–118 (2004).

Lin, X. T. et al. Deformation behaviors of existing tunnels caused by shield tunneling undercrossing with oblique angle. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 89, 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2019.03.021 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**Kan Huang: ** Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Funding acquisition. **Zhihao Li: ** Visualization, Writing—original draft. **Jinwen Zhang: ** Formal analysis, Investigation. **Ran Chen: ** Project administration. **Kaidi Zhou: ** Visualization. **Bin Huang: ** Methodology. **Ke Xing: ** Formal analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, K., Li, Z., Zhang, J. et al. Analytical solution for deformation of an existing tunnel induced by shield tunnelling overcrossing in complex strata. Sci Rep 16, 3364 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33329-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33329-4