Abstract

This study evaluates an integrated bioaugmentation–biostimulation strategy for carbofuran remediation using Ochrobactrum intermedium formulated as water-dispersible granules (WDGs) in combination with biogas slurry (BGS). In minimal salt medium, O. intermedium degraded 92.2% of 100 mg L⁻¹ carbofuran within 120 h (k = 0.69 day⁻¹; t₁/₂ = 1 day). GC–MS identified carbofuran-7-phenol and monoethyl phthalate as key intermediates. The WDGs retained > 80% viability and ~ 94% degradation efficiency after six months at 30 °C. In aqueous systems, BGS enhanced WDG activity, enabling 99% degradation within 120 h. In soil microcosms, WDGs + BGS (T5) achieved 92.4% degradation in 30 days (t₁/₂ = 8.04 days), outperforming WDGs alone (61%, t₁/₂ = 21.7 days), BGS alone (42%, t₁/₂ = 38.5 days), and control (26%). The combined treatment also improved microbial persistence, soil nutrients, and tomato growth, with no phytotoxic effects. Overall, coupling microbial formulations with organic amendments provides a robust and sustainable solution for remediating carbofuran-contaminated soils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The swift rise of industrial activities and the rapid spread of urban areas in recent years have alarmingly led to the surge of hazardous environmental pollutants, often identified as xenobiotics1,2. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency identifies critical pollutants which span multiple chemical categories, including halogenated aliphatics, various aromatic derivatives, agricultural pesticides, plasticizers, and other toxic organics such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)3. Among these, chemical pesticides are extensively used across agricultural systems not only for controlling insect pests, weeds, and pathogens but also for promoting crop productivity and yield. While pesticides play an important role in crop protection, their use also carries significant drawbacks, as they can contaminate natural resources and exert harmful effects on both terrestrial and aquatic organisms. Their functional group categorizes chemical pesticides into pyrethroids, organophosphates, organochlorines, and carbamates. The carbamates are ester derivatives of carbamic acid, widely used as insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, and nematicides. This class of pesticide inhibits acetylcholinesterase, which can cause convulsions, tremors, and death4,5. Carbofuran, chemically identified as 2,3-dihydro-2,2-dimethylbenzofuran-7-yl methylcarbamate (C₁₂H₁₅NO₃), is an N-methyl carbamate pesticide commonly used to control a wide range of pests and nematodes across agricultural, horticultural, and forestry systems. Its toxicity stems from the inhibition of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE), causing abnormal accumulation of acetylcholine at neural junctions, which disrupts nerve signaling and can lead to symptoms such as tremors, convulsions, and potentially fatal outcomes6. The toxic impacts of carbofuran at the contaminated sites make these sites unfit for use until complete cleanup and necessitate remediation to control the movement of the compound in groundwater. Remediation is urgently required for these contaminated sites.

A wide range of remediation strategies has been documented for sites contaminated with carbofuran, encompassing physical, chemical, and biological approaches that can be employed under both in-situ and ex-situ conditions. In recent years, biological methods have gained prominence as sustainable tools for detoxifying environments impacted by xenobiotic compounds. A multitude of microorganisms possessing the capability to degrade environmental contaminants has been recognized, either through their utilization as direct sources of carbon or nitrogen, or by facilitating their transformation via co-metabolic mechanisms. Bacterial strains like Pseudomonas sp., Novosphingobium sp., Paracoccus sp., Sphingomonas paucimobilis, Chrysobacterium joostei, etc., have been used for carbofuran degradation in soils6,7,8,9,10,11.

Microbial degradation does not always work efficiently in real environments because several physical and biological factors can limit microbial activity. Changes in temperature, pollutant concentration, soil pH, moisture and redox conditions can directly affect how well microbes grow and how active their enzymes are. Moreover, the introduced degraders often compete with native microorganisms or may be suppressed by predators such as protozoa, which reduces their survival and overall degradation performance12,13,14.

Microbial formulations provide a microhabitat for potent microbial strains, shielding them from harsh conditions and competing species, thereby aiding faster adaptation at contaminated sites15. Research on employing immobilized or formulated microbial cells for the remediation of carbofuran-contaminated environments remains limited. Nevertheless, some reports have demonstrated the application of carrier-based formulations—such as those prepared with wheat straw, sodium alginate, or corn cob—for delivering bacterial inoculants to sites polluted with carbofuran16,17,18. Nevertheless, it remains essential to design improved microbial formulations that offer greater stability during storage and ease of use during field application.

During bioremediation, the persistence and multiplication of introduced microorganisms—whether naturally present or artificially improved—are largely dependent on their ability to metabolize pollutants as sources of carbon or nitrogen20. In this regard, biostimulants serve an important function by furnishing efficient bacterial strains with supplementary resources such as nutrient elements, organic carbon inputs, and compounds that can act as electron donors or acceptors, thereby providing the energy required for sustaining growth after application21,22,23. Several studies have utilized organic substrates, such as rice straw, molasses, sludge from renewable energy processes, and bio mixtures (comprising lignocellulosic substrates and humic components), to stimulate bacterial activity and enhance the removal of carbofuran19,24,25.

The primary aim of the present research is to examine the capacity of a Gram-negative aerobic bacterium, O. intermedium, to metabolize carbofuran within both soil matrices and aqueous environments. O intermedium is a naturally occurring, soil- and rhizosphere-associated alphaproteobacterium that has repeatedly been isolated from agricultural soils and plant roots and characterized as a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium (PGPR). For example, strain SA148, isolated from desert soils in Saudi Arabia, was genomically and phenotypically characterized as a PGPR capable of enhancing plant performance under arid conditions without any reported phytotoxicity or ecosystem disruption27. Similarly, deliberate inoculation of O. intermedium strains into soil has been shown to stimulate growth of wheat and lentil, including under metal stress, and to increase biomass and yield parameters relative to uninoculated controls27. These reports indicate that O. intermedium is both ecologically compatible and agriculturally beneficial, supporting its selection as a safe bioaugmentation candidate for carbofuran remediation. The strain was subsequently transformed into several formulations, checked for shelf life during a defined storage period, and enhanced carbofuran degradation using biogas slurry as a biostimulant in soil, with an examination of its effect on plant growth and soil quality.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Carbofuran (> 99% purity) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich, Germany (CAS no. 1563-66−2). Microbial growth media, including Nutrient Broth and Agar, were purchased from Himedia, India. All other reagent-grade chemicals and HPLC-grade solvents were purchased from Merck, KGaA, Germany.

Composition of minimal salt media (MSM) for Carbofuran degradation

The carbofuran degrading microbial strains were cultivated in carbon deficient minimal salt media (MSM) described by Peng et al.10, comprised of K2HPO4–1.5 g L–1; KH2PO4–0.5 g L‒1; NaCl – 1.0 g L–1; NH4NO3–1.0 g L–1, MgSO4.7H2O – 0.2 g L–1; carbofuran as a carbon source at different concentrations (50 to 400 mg L–1).

Isolation of carbofuran-degrading bacterial strains

Soil samples intended for isolating carbofuran-degrading microorganisms were obtained from an agricultural site in Jatola village, Farukhnagar, Haryana (28.3808434 °N, 76.8169465 °E), which had a documented history of carbofuran usage. Following collection, the composite samples were carried to the laboratory in an ice-cooled container and subsequently preserved at − 20 °C until further processing28,29.

The potential carbofuran degraders were isolated via the enrichment culture technique described in10 in a carbon-limiting MSM. Briefly, bacterial strains in a 1 g composite soil sample were sequentially enriched with increasing concentrations of carbofuran (50–400 mg L–1) and incubated at 120 rpm and 30 ˚C for 120 h. The pure bacterial colonies were isolated from each enrichment culture using the spread plate method on solidified MSM containing 100 mg L–1 carbofuran. The pure, isolated colonies were maintained on carbofuran (100 mg L–1) spiked MSM as agar slants and glycerol stocks and stored at − 20 ˚C for further use.

Biochemical and molecular characterization of carbofuran-degrading bacteria

The biochemical characterization of isolated bacterial strains was performed using the Hi25™ Enterobacteriaceae Identification Kit (HiMedia, India). Phylogenetic characterization of the bacterial isolates was performed using 16 S rRNA gene sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted following the procedure of Gomes et al.30, with minor adjustments as required. The obtained 16 S rRNA sequence was then analyzed through BLAST searches against reference databases to determine its closest taxonomic affiliations. Evolutionary relationships were further assessed by generating a phylogenetic tree, which was constructed based on calculated genetic distances using the neighbour-joining method.

Carbofuran degradation by O. intermedium in aqueous media

Degradation experiments in the aqueous phase were carried out using MSM supplemented with carbofuran at a concentration of 100 mg L⁻¹. To prepare the setup, a sterile stock solution of carbofuran was introduced into 50 mL of autoclaved MSM contained in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks, thereby achieving the desired final concentration. Each flask was inoculated with actively growing bacterial cultures and maintained under incubation at 30 ± 2 °C with shaking at 120 rpm for a period of five days. Abiotic controls were maintained as uninoculated MSM II to compare the effects of carbofuran, thereby removing the potential influence of strains. Periodic sampling was conducted every 24 h for up to five days to estimate microbial growth, residual carbofuran, and intermediate metabolites.

The degradation kinetics for carbofuran removal from aqueous media were estimated via a first-order kinetics model.

Design of water-dispersible granular formulations for enhanced bioremediation of Carbofuran

Microbial cultures were freshly propagated in nutrient medium from preserved mother stocks, reaching a final density of approximately 10¹¹ CFU mL⁻¹. The biomass was collected by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in 0.85% (w/v) NaCl solution, after which the suspension was standardized to about 10⁹ CFU mL⁻¹ for use in formulation. Preparation of the WDG formulation was carried out through the wet granulation technique, as outlined by Chumthong et al.32, employing a formulation composition like that recommended by Khan et al.20. A 100 g batch of WDG formulation was prepared using talcum powder (90 g) as the inert carrier or diluent, sodium naphthalene sulfonate (2 g) as the wetting agent, alginic acid (5 g) serving as the dispersant, and soy flour (3 g) functioning both as a nutritional additive and binding material. Prior to mixing, all components excluding the microbial culture were sterilized and subsequently blended thoroughly using a laboratory mixer (Remi, India). The bacterial cell suspension (40 mL) with an initial cell load of ~ 109 CFU mL−¹ was then added to the powder mix and mixed thoroughly by hand until the texture became smooth and sticky. Granules were produced by first preparing a dough-like mixture, from which noodle-shaped strands were manually extruded and subsequently air-dried under laminar airflow conditions overnight. The air-dried noodles were shaken in a container until they broke down into 1–2 mm granules. The developed granular formulation was stored at 30 ˚C for viability assessment. In line with the recommendations of the Collaborative International Pesticides Analytical Council³³, the stability of the microbial WDG formulation was examined.

Shelf-life assessment and Carbofuran degrading efficiency of microbial WDG formulation

The stability of the microbial WDG formulation was assessed by monitoring cellular viability over a six-month storage period at a controlled temperature of 30 ± 2 °C. To quantify the microorganisms, 1 g of the formulation was dispersed in 10 mL of sterile distilled water and subjected to serial tenfold dilutions. From each dilution, 100 µL aliquots were evenly spread onto nutrient agar plates, which were then incubated at 30 ± 2 °C for 48 h. The number of viable microorganisms was counted and expressed as colony-forming units (CFU) per gram of formulation (CFU g⁻¹), based on dry weight.

The effectiveness of the WDG formulation in breaking down carbofuran was systematically evaluated over a six-month storage period at a controlled temperature of 30 ± 2 °C. In tests involving the aqueous phase, a volume of 100 mL of sterile MSM, supplemented with carbofuran at a concentration of 100 mg L⁻¹, was transferred into Erlenmeyer flasks (250 mL), which were subsequently inoculated with one gram of the formulation. The flasks were incubated at 30 ± 2 °C on an orbital shaker set to 120 rpm for 10 days. For the soil microcosm experiments, 20 g of autoclaved soil, treated with carbofuran at 100 mg kg⁻¹, was thoroughly mixed in Erlenmeyer flasks and combined with one gram of the WDG formulation. All experiments were carried out in triplicate to confirm reproducibility. Sampling was performed every 24 h, and residual carbofuran levels were determined using HPLC. The same procedure was repeated at the end of every 30 days of storage, up to 180 days.

Evaluation of organic amendments for biostimulation of Carbofuran degraders

Different organic amendments, namely wheat straw, biogas slurry, and sucrose, were evaluated as potential biostimulants to enhance the efficiency of carbofuran degradation. Wheat straw and biogas slurry were processed by drying in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h, then finely milled and passed through a 5 mm mesh before application. The obtained amendments were autoclaved at 15 psi, 121 ˚C for 20 min. 100 ml of sterilized MSM spiked with carbofuran was taken in a 250 ml Erlenmeyer flask and inoculated with 1 g of the formulation. Wheat straw, biogas slurry, and sucrose were added at 0.5% w/v to the MSM for carbofuran degradation. Incubation was carried out in an orbital shaker at 120 rpm and 30 ± 2 °C for 10 days. Sampling was performed every 24 h, and residual carbofuran levels were estimated using HPLC. The chemical characteristics of the wheat straw and biogas slurry, including total carbon, nitrogen, and C: N ratio, are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Impact of combined microbial formulation and biostimulants on Carbofuran degradation and soil–plant health

In-planta assay

The efficacy of the integrated bioremediation approach was assessed through an in-planta assay, focusing on soil health and biomass of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum var. Pusa Ruby) in carbofuran-stressed soil. The study was conducted in a net house under natural environmental conditions at Gramodaya Parisar, IIT Delhi (28°32’30"N 77°11’23"E)) from December 2020 to March 2021. The top layer of bulk soil was unearthed from Gramodaya Parisar, IIT Delhi, and sieved to obtain uniform-sized particles. The soil mix was prepared by thoroughly mixing soil and farmyard manure in a ratio of 3:1. Earthen pots with 25 cm diameter and depth, were filled with 5 kg of soil mix and spiked with carbofuran @ 100 mg kg‒1 soil. Twenty-one-day-old seedlings grown in nursery trays were carefully uprooted and transferred to pots containing a soil mix, with one seedling per pot. The earthen pots were kept at 4–5 cm distance from ground using bricks and stones. A different set of treatments was similar to that of soil microcosm studies for carbofuran degradation, except that the soil mix was used instead of bulk soil in all treatments. Treatments for in planta assay were as follows: T1: soil mix; T2: soil mix + carbofuran (@ 100 mg kg‒1); T3: soil mix + carbofuran + BGS; T4: soil mix + carbofuran + WDG; T5: soil mix + carbofuran + WDG + BGS. Soil was amended with biogas slurry at 0.5% (w/w) to act as a biostimulant, followed by inoculation of the pots with WDGs (~ 10⁸ CFU g⁻¹ soil). The pots were maintained in a net house to minimize pest infestation, and any emerging weeds were manually removed. The pots were watered every three days. Ten replicates for each treatment were maintained during the experiment.

Assessment of soil health through Physico-chemical parameters

Baseline soil physicochemical properties were recorded prior to treatment application, and composite soil samples collected sixty days post-sowing were analyzed for changes in elemental composition using ICP-MS at IIT Delhi. Total organic carbon (TOC), total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN), and residual carbofuran concentrations were quantified following standard protocols33. All baseline and post-treatment soil characteristics are provided in Supplementary Table 2a and 2b.

Determination of plant growth parameters

The tomato plants (Lycopersicum esculentum var. Pusa Ruby) were harvested 60 days after sowing, and various plant growth parameters, including shoot length, root length, fresh weight, and chlorophyll content, were recorded. Leaf chlorophyll content (Chlorophyll a and Chlorophyll b) was measured as per the standard protocol34.

Analytical techniques

Carbofuran residues and their metabolites were extracted from aqueous and soil samples following the procedures of Peng et al.10 and Yang et al.35. Analyses were performed using HPLC and GC-MS. HPLC separation was carried out on a C18 reversed-phase column (100 mm × 4.6 mm) with a mobile phase of acetonitrile and water (60:40, v/v), flow rate 0.25 mL min⁻¹, injection volume 10 µL, and detection at 270 nm; the chromatographic run was completed in 10 min with a limit of detection of 1 µg L⁻¹. GC-MS profiling was conducted on a Shimadzu QP-2010 Plus system using helium as the carrier gas (split 10:1) with oven temperatures programmed from 60 °C (2 min) to 300 °C at 10 °C min⁻¹, held for 5 min. Samples were prepared by centrifugation, followed by liquid–liquid extraction with dichloromethane, concentration, and re-dissolution in methanol prior to analysis.

Statistical analysis

All experimental data were analyzed statistically through analysis of variance (ANOVA) employing SPSS (Windows, version 16.0), with treatment variations assessed using the Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) test at a significance criterion of P ≤ 0.05, and findings expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) derived from replicates.

Results and discussion

Isolation and characterization of carbofuran-degrading microbial strains

An increase in carbofuran concentration during enrichment cultures resulted in a reduction of microbial colonies. The bacterium CBF 6, sourced from cultivated soil, was examined for its potential to degrade carbofuran when provided as the single carbon source in MSM. The data about the biochemical characterization of bacterial isolate CBF 6 are presented in Supplementary Table 3. Gram staining confirmed the strain CBF 6 as a rod-shaped Gram-negative bacterium.

The 16 S rRNA gene sequencing and evolutionary analysis were performed at Dr. KPC Life Sciences Pvt. Ltd. in India. The phylogenetic tree of strain CBF 6 is provided in supplementary Fig. 1. The 16 S rRNA sequences from strain CBF 6 showed the highest homology to that of O. intermedium strain R16 (Accession no. MN749900.1). O. intermedium is a naturally occurring, soil- and rhizosphere-associated alphaproteobacterium that has repeatedly been isolated from agricultural soils and plant roots and characterized as a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium (PGPR). For example, strain SA148, isolated from desert soils in Saudi Arabia, was genomically and phenotypically characterized as a PGPR capable of enhancing plant performance under arid conditions without any reported phytotoxicity or ecosystem disruption²⁸. Similarly, deliberate inoculation of O. intermedium strains into soil has been shown to stimulate growth of wheat and lentil, including under metal stress, and to increase biomass and yield parameters relative to uninoculated controls²⁹. These reports indicate that O. intermedium is both ecologically compatible and agriculturally beneficial, supporting its selection as a safe bioaugmentation candidate for carbofuran remediation.

The aqueous phase degradation study for carbofuran was conducted at an initial carbofuran concentration of 100 mg L-1 in MSM. The results on carbofuran degradation by O. intermedium and bacterial growth are depicted in Fig. 1. O. intermedium utilized carbofuran as the sole carbon source, showing active growth up to 96 h (OD₆₀₀ = 0.48), after which the culture entered the stationary phase (Fig. 1). The residual carbofuran levels estimated via HPLC determined the carbofuran degrading efficiency of O. intermedium. The strain O. intermedium degraded 92.2% of carbofuran from the media within 120 h of incubation. The carbofuran concentration decreased rapidly until 96 h, at which 89% of the overall 92% carbofuran degradation had occurred, followed by just 3% degradation up to 120 h.

The carbofuran degradation rate by O. intermedium was found to parallel the microbial cell load observed in the culture flasks. The higher microbial cell counts were recorded with O. intermedium, showing cell viability counts in the range of ~ 109 CFU mL‒1 at 96 h, after which the strain attained the stationary phase. Several studies have documented microbial degradation of carbofuran. For example, Patowary et al.⁹ reported that Pseudomonas aeruginosa S07 degraded 89% of carbofuran in MSM having initial carbofuran concentration of 150 mgL− 1 within 120 h. Within a swift 12-hour incubation, the Bacillus sp. strain DT1 accomplished the complete removal of 60 mL− 1 carbofuran from aqueous environments. Many microbial strains with the capability to degrade carbofuran have been identified. Sphingomonas paucimobilis and P. aeruginosa, for instance, were isolated from pesticide-contaminated potato soils8. Paracoccus sp. YM3, isolated from contaminated sludge, degraded 78% of carbofuran within 3 days, which increased to 88% with sucrose supplementation10. More recently, P. aeruginosa S07 was shown to degrade 89% of carbofuran (150 mg L⁻¹) in 120 h7.

The proliferation and metabolic efficacies of bacterial strains are typically influenced by variables such as growth substrates, classification, bioavailability, and concentration of pollutants, as well as the presence of cofactors and the release of toxic metabolites36. Thus, greater metabolic activity could be easily achieved by providing optimized growth conditions for potential microbial strains. O. intermedium, in the present study, showed highly efficient carbofuran removal potential over several bacterial strains reported in the literature, as more than 90% of the initial 100 mg L‒¹ carbofuran was degraded within 120 h of incubation, with a half-life of 1 day.

Carbofuran degradation kinetics in the aqueous phase by O. intermedium were examined using an integrated rate law model. The linear fit of ln(C) versus time confirmed a degradation rate constant of 0.69 day⁻¹ for carbofuran. This corresponds to an estimated half-life of about 1 day in MSM cultures inoculated with O. intermedium. A Pseudomonas stutzeri PS21 strain efficiently degraded carbofuran in both rotatory and static incubation, with a sharp decline in half-life to 1.01–3.06 days from the regular 30–60 days (in soil and water)⁸. In Plangklang and Reungsang’S study, the carbofuran degrading potential of Burkholderia sp. PCL3 was assessed at different carbofuran concentrations (5 ‒ 200 mg L− 1). Free cells of strain PCL3 degraded carbofuran in MSM with a calculated half-life of 4.9 days and a degradation rate constant of 0.08 day⁻¹. The strain O. intermedium used in the present study was a more efficient carbofuran degrader, as higher carbofuran removal rates resulted in lower carbofuran half-life, which were achieved in the aqueous phase carbofuran degradation studies. Reports indicate that some strains, such as Novosphingobium FND-3, degrade carbofuran more rapidly. Peng et al.10 examined this strain in MSM with 100 mg L⁻¹ carbofuran under different cultivation conditions and found an average degradation rate of 28.6 mg L⁻¹ h⁻¹, which was substantially faster than that of O. intermedium used in the present study.

Elucidation of the Carbofuran degradation pathway

The carbofuran degradation intermediate metabolites were extracted from 48-hour-old aqueous microcosms treated with O. intermedium and analyzed via GC-MS. The mass spectrum of metabolites from aqueous extract is depicted in Fig. 2. The metabolite carbofuran-7-phenol, with a molecular weight of 164 Da, was recorded at 11.4 min R.T., contributing 6% to the total area (Fig. 2).

In the present study, the major intermediate metabolite was 1,2-benzene carboxylic acid, monoethyl ester, with a molecular mass of 194 Da, detected at 15.2 RT. The formation of this ester might have originated from the sequential transformation of carbofuran-7-phenol (Fig. 3). Previous research has documented analogous metabolites generated during carbofuran degradation. Yan et al.¹¹ discovered that carbofuran was the only carbon source that supported the growth of Novosphingobium sp. FND-3 and the bacteria break it down, resulting in the synthesis of various intermediate chemicals observed via GC-MS analysis. Peaks reflective of carbofuran and its derivative, carbofuran-7-phenol, were identified at retention intervals of 9.36 and 6.39 min, respectively. According to Nguyen et al.38, the degradation of carbofuran by the bacterial strain Sphingomonas sp. KN 65.2, in both its wild-type and mutant forms, resulted in the formation of several intermediate compounds. In the mutant strain, hydrolysis of the carbamate group produced carbofuran-7-phenol as the primary byproduct. Further oxidation of this metabolite caused cleavage of the furan ring, forming 3-(2-hydroxy-2-methylpropyl) benzene-1,2-diol. Thus, based on the intermediate metabolites, a degradation pathway, as depicted in supplementary Fig. 2, was proposed for carbofuran degradation by O. intermedium.

Shelf-life assessment and degradation efficacy of Water-dispersible granular formulation

Storage stability of water-dispersible granules (WDG) was evaluated at 30 °C for six months (Fig. 3). For the first two months, cell numbers remained steady at 8.2–8 log10 CFU g‒1 (1.6 × 10⁸ to 1 × 10⁸ CFU g-1) (P ≤ 0.05), after which a gradual decline was observed. By the end of the study, nearly 80% of the original viability was maintained.

The biological activity or viability of microbial products must remain functional throughout the application and storage period, or shelf life, which varies from several months to several years39,40. Formulated microbial strains face survival challenges during storage and at contaminated sites due to factors like moisture, temperature, and contaminant levels. These stresses often limit their effectiveness in field applications41,42,43. In aqueous phase degradation studies, the carbofuran degrading potential of WDGs remained significantly at par till 3 months with 96% carbofuran degradation. A slight reduction (6%) in carbofuran degrading efficiency was recorded at the end of the storage period (Fig. 3).

The carbofuran-degrading potential of WDGs was observed in accordance with the viable cell counts present in the formulation over the storage period. WDGs contained the maximum cell viability (3.56 ± 0.21 × 108 CFU g‒1 formulation), which remained significantly (P ≤ 0.05) similar till six months. In a similar study by Umar Mustapha et al.48, the effect of immobilized Enterobacter sp. was compared with that of free cell extracts from the same strain. Immobilized cells showed a significant enhancement in carbofuran degradation compared to free cells. Enterobacter sp. entrapped into gellan gum degraded 50 mg L− 1 carbofuran within 9 h, while free cells took 12 h for the same. Bacillus sp. strain DT1 has also been shown to efficiently degrade carbofuran, achieving up to 97.5% removal when immobilized on rice straw, highlighting the effectiveness of immobilized-cell systems for enhancing pesticide biodegradation⁴⁶. Furthermore, other studies indicate that immobilizing white-rot fungi on carriers such as corn stover or wheat straw can achieve carbofuran degradation rates of up to 69.83% within five days under optimal temperature and acidic conditions, surpassing the degradation efficacy of un-immobilized microbial cells⁴⁷. This enhanced degradation efficiency is often attributed to the protective microenvironment provided by immobilization, which can shield microbial cells from harsh environmental conditions and improve their longevity and metabolic activity. Such controlled immobilization technology offers a promising avenue for sustained remediation efforts in pesticide-contaminated environments, enhancing both the persistence and efficacy of biodegrading microorganisms46. The implementation of such microbial formulations in real-world scenarios has been shown to improve the adsorption of contaminants and the water-holding capacity of soil, further aiding in degradation⁴⁹.

Selection of organic amendments for stimulating Carbofuran degraders

We studied the effect of exogenous carbon sources (wheat straw, biogas slurry, and sucrose) on carbofuran degradation with WDGs in MSM (Fig. 4). Although O. intermedium was a rapid carbofuran degrader, an additional energy source was screened to enhance microbial activity that might be affected during application in unfavorable conditions. The bacterial metabolic activity was not significantly enhanced when wheat straw was added as an energy source. Sucrose was a simple carbon source that significantly improved microbial activity, resulting in complete carbofuran removal within 96 h of incubation. A similar carbofuran removal potential was observed with biogas slurry as a biostimulant. A 99.8% carbofuran degradation was recorded within 120 h with the co-application of WDGs of O. intermedium and biogas slurry as a biostimulant.

Carbofuran degradation over 120 h by O. intermedium WDG formulations supplemented with different organic amendments. Treatments included sucrose, wheat straw, and biogas slurry, with WDG alone as control. Error bars represent standard deviations (n = 3). Different letters on bars denote statistically significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 (DMRT).

The O. intermedium strain exhibited compatibility with biogas slurry, which is notably enriched with various essential nutrients and bioactive compounds as indicated by Waqas et al.49. Tiwari et al.50 have also observed higher microbial activity and biomass in soil amended with biogas slurry. Thus, biogas slurry, an efficient and readily available nutrient source, was selected to stimulate microbial activity in soil microcosm experiments.

Impact of combined microbial formulation and biostimulants on Carbofuran degradation and soil–plant health

Soil microcosm setup for Carbofuran biodegradation

The degradation of carbofuran and the microbial growth of O. intermedium were studied in soil microcosms augmented with WDGs and stimulated with biogas slurry. The soil microcosms cotreated with WDGs and biogas slurry (T5) exhibited higher carbofuran degradation (92.4%) in the soil compared to T3 and T4, which showed only 42% and 61% carbofuran removal after 30 days of treatment. The unaugmented and unstimulated control microcosms (T2) showed steady carbofuran removal from soil and recorded only 26% degradation after 30 days (Fig. 5a). The strain Pichia anomala HQ-C-01 enhanced carbofuran breakdown, achieving degradation rates of 73.2% in sterilized soil and 85.1% in non-sterilized soil³⁷. Waste-derived inputs such as biosludge, composted materials, and agricultural processing residues are commonly used to enrich soil because they are economical and enhance nutrient turnover⁵³. Trametes versicolor, a medicinal mushroom, attained 55.1% degradation of carbofuran utilizing rice husk as a nutrient source within 34 days (t₁/₂ = 29.9 days), producing 3-hydroxycarbofuran as a metabolite52.

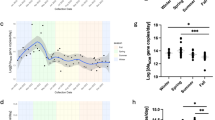

(a) Residual carbofuran levels in soil over 30 days under different treatments; 5 (b) Temporal growth pattern of O. intermedium in carbofuran-amended soil during 30 days of incubation. T1 ‒ Bulk soil; T2 ‒ Bulk soil + carbofuran; T3 ‒ Bulk soil + carbofuran + BGS; T4 ‒ Bulk soil + carbofuran + WDG; T5 ‒ Bulk soil + carbofuran + WDG + biogas slurry. The legend depicts the sampling period with an interval of 10 days. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 5). Different letters on bars denote statistically significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 (DMRT). (c) Microcosm-based kinetic analysis of carbofuran degradation by O. intermedium.

The carbofuran degradation recorded the viable cell counts (Fig. 5b). Microcosms supplemented with biogas slurry (T3) exhibited greater bacterial populations, reaching 6.2 × 10⁷ CFU g⁻¹, compared to the treatment receiving only carbofuran (3.2 × 10⁵ CFU g⁻¹ of soil) by the 10th day after inoculation.

The highest bacterial populations were observed in microcosms receiving both biogas slurry and WDGs (T5), reaching 3.5 × 10⁹ CFU g⁻¹ soil on day 10 and slightly declining to 3.6 × 10⁷ CFU g⁻¹ soil by day 20. Microcosms treated with carbofuran alone (T1) maintained much lower counts, recording 3.9 × 10³ CFU g⁻¹ soil after 30 days. In contrast, control microcosms without amendments or carbofuran showed relatively stable populations ranging from 1.2 × 10⁵ to 4.5 × 10⁵ CFU g⁻¹ soil over the course of the experiment.

The degradation data from soil microcosms were analyzed using first-order kinetics, as shown in Fig. 5c. It illustrates that carbofuran degraded most rapidly in T5, with a calculated first-order rate constant of 0.086 day⁻¹ and a corresponding half-life of 8.04 days. Slower degradation was observed in microcosms containing only biogas slurry (T3) or WDGs (T4), which showed half-lives of 38.5 and 21.7 days, respectively. The higher CBF degradation rates in microcosms inoculated with WDGs are attributed to the carbofuran-degrading O. intermedium cells entrapped in WDGs. Several studies have documented that adding organic substrates can enhance microbial activity at contaminated sites53,54,55. Biogas slurry, a byproduct of anaerobic digestion, contains readily available significant levels of macro (N, P, K) and micronutrients and can be used as a supplement to modify nutritional element ratios and promote microbial community activity17.

Research on biogas slurry for carbofuran-contaminated soil remediation is scarce. In their study, Pimmata et al.25 explored the roles of bioaugmentation and biostimulation in enhancing soil carbofuran degradation. The Burkholderia cepacia PCL3 strain alone reduced carbofuran’s half-life to 3.6 days, yielding a degradation rate of 0.19 day⁻¹.The carbofuran removal efficiency of strain PCL 3 was enhanced by adding sludge from the hydrogen energy plant and mixed microbial culture, which degraded the carbofuran with a rate constant of 0.32 day‒1 and a half-life of 2.2 days. The carbofuran-removing potential of biostimulated strain PCL3 was significantly greater than that of O. intermedium used in the present study. However, with PCL3, a mixed bacterial culture was also applied, which might have resulted in enhanced carbofuran degradation. In a similar survey of Raimondo et al.56, the effect of sugarcane filter cake biostimulation on lindane removal in soil augmented with Streptomyces sp. was investigated. A 36% lindane removal was observed in the unaugmented and unstimulated soil. The lindane removal efficiency reached 80% in silt loam soil enhanced with a blend of Streptomyces species and fortified with sugarcane filter cake.

Plant biomass yield

The impact of the combined bioremediation strategy on tomato plant growth was evaluated in-planta over a period of 60 days. The results on the impact of BGS and WDG formulation on plant growth in carbofuran-contaminated soil are presented in Table 1. We recorded the maximum average shoot height (118 cm) in the pots treated with both WDGs and biogas slurry (T5), which was significantly comparable (P ≤ 0.05) to control treatment T1 (115 cm) and higher than treatment with either BGS (T3, 104 cm) and WDGs (T4, 94 cm). A similar trend was also observed with the root length, shoot length, and chlorophyll content.

As shown in Table 1, root lengths in the control treatment (T1), which lacked carbofuran, were comparable to those in T5. This suggests that the combined bioremediation approach does not negatively affect plant growth while effectively removing carbofuran residues from the soil.

Carbofuran is a systemic insecticide/nematicide that has been reported to enhance plant productivity in nematode-infested soils. However, at concentrations higher than the recommended dose (i.e., 1 kg active ingredient per hectare), carbofuran has shown phytotoxic effects on several crops, including tomatoes⁵⁹, ⁶⁰. Throughout the 60-day experiment, untreated soil (T2) maintained relatively high carbofuran levels, ranging from 95 to 70 mg kg⁻¹. Thus, phytotoxic effects were observed in tomato plants in the same soil. However, in treated soils (T3, T4, and T5), the carbofuran levels were significantly reduced, and better plant growth was observed; the most significant improvement was noted in treatment T5.

The biogas slurry enhanced the soil microbial activity and acted as a fertilizer by providing essential nutrients for plant growth. Biogas slurry, enriched with nutrients and bioactive compounds, is widely recognized as an effective organic manure⁶¹. Applying biogas slurry diluted with two parts waters under greenhouse conditions increased tomato yield by 2.74% compared to the control, as reported by Liu et al.⁶². In the present investigation, the primary objective of biogas slurry application was not as a nutrient source but rather to stimulate the metabolic activity of O. intermedium for enhanced degradation of residual carbofuran in soil. Accordingly, a lower concentration (0.5% w/w) of biogas slurry was employed. Nevertheless, applying higher concentrations of biogas slurry in carbofuran-contaminated soils holds promise for simultaneously promoting soil bioremediation, improving soil fertility, enhancing crop productivity, and facilitating sustainable organic waste utilization.

The soil mix used for the in-planta assay received farmyard manure in a 3:1 ratio and thus showed an increased level of nutrients compared to bulk soil. All treatments observed total organic carbon values within the standard 0.4–0.7% range. However, the soil amended with biogas slurry (0.5% w/w) (T3, T5) showed a higher organic carbon content (0.65 ‒ 0.68%) than unstimulated soil T1, T2, T4 (0.58 ‒ 0.6%). A comparable pattern was noted for total Kjeldahl nitrogen, with biostimulation treatments (T3 and T5) yielding significantly higher values (P ≤ 0.05) than the control. Treatments T3 and T5 recorded a slight increase in nutrient content (P, K, Mg, Ca, B, Mo, Na, Mn, Fe, Zn) compared to unstimulated treatments. BGS has been reported to have the potential to enhance soil fertility by improving soil nutrient composition, texture, and microbial community dynamics61,62. All the treatments inoculated with WDGs (T4 & T5) did not significantly improve the nutrient levels. Still, they showed a minor increase in Mg content (T4 ‒ 3292.7 ± 17 mg kg‒1, T5 ‒ 3422.2 ± 11.8 mg kg‒1) over unaugmented treatments as WDGs contained talcum powder as a primary ingredient (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2–90% w/w). However, soils treated with BGS (T3 and T5) contained slightly higher micronutrient levels than T2 and T4 and were statistically comparable (P ≤ 0.05) to the control (T1). Application of BGS improved soil nutrient status supported plant growth, and enhanced carbofuran degradation by O. intermedium.

Conclusions

This study investigated the aqueous phase degradation of carbofuran using O. intermedium isolated from a contaminated site. The bacterium achieved 92% degradation of 100 mg L⁻¹ carbofuran in MSM, corresponding to k = 0.69 day⁻¹ (t₁/₂ = 1 day). GC-MS analysis detected carbofuran-7-phenol and the monoethyl ester of 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid as major metabolites, indicating the likely degradation pathway. The proposed carbofuran degradation pathway is based on detected metabolites and literature evidence; however, further studies, including enzyme or transcriptomic analyses, could be explored to further back the results. Among tested formulations, water-dispersible granules (WDGs) showed the highest stability, retaining ~ 94% activity after 6 months at 30 °C, and 85% efficiency in soil microcosms. Powder and bead formulations showed > 50% decline in activity within 6 months. Biogas slurry-stimulated WDGs achieved 95% degradation in soil within 30 days. The integrated bioaugmentation and biostimulation approach enhanced carbofuran removal while supporting tomato growth and soil health.

Treatments | shoot length | Root length | Fresh Weight | Chlorophyll A | Chlorophyll B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

T1 | 115.84a | 27.16a | 91.48a | 3.24 | 1.188a |

T2 | 86.92b | 15.62b | 55.44b | 1.476b | 0.558b |

T3 | 104.14c | 20.06c | 64.86c | 2.822c | 1.586c |

T4 | 94.06d | 17.06d | 75.96d | 2.504d | 1.428d |

T5 | 118.8a | 25.94a | 88.32a | 3.124a | 1.29a |

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Ataikiru, T. L. A. & Ajuzieogu, C. A. Enhanced bioremediation of pesticides contaminated soil using organic (compost) and inorganic (NPK) fertilizers. Heliyon 9, e00000 (2023).

Balume, I. K., Keya, O., Karanja, N. K. & Woomer, P. L. Shelf-life of legume inoculants in different carrier materials available in East Africa. Afr. Crop Sci. J. 23, 379–385 (2015).

Bano, N. & Musarrat, J. Characterization of a novel carbofuran-degrading Pseudomonas sp. with plant-growth promotion and biocontrol potential. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 231, 13–17 (2004).

Castellanos Rozo, J., Sánchez Nieves, J., Uribe Vélez, D. & Moreno Chacón, L. Melgarejo Muñoz, L. M. Characterization of carbofuran-degrading bacteria from pesticide-treated potato soils. Revista Facultad Nac. De Agronomía Medellín. 66, 6899–6908 (2013).

Chumthong, A., Kanjanamaneesathian, M., Pengnoo, A. & Wiwattanapatapee, R. Water-soluble Bacillus megaterium granules for biological control of rice sheath blight. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24, 2499 (2008).

Dinka, D. D. Environmental xenobiotics and their impacts. J. Environ. Pollution Hum. Health. 6, 77–88 (2018).

Dobrat, W., Martijn, A. C. I. P. A. C. & Handbook, F. Physico-chemical Methods for Technical and Formulated Pesticides.

Duc, H. D. Enhancement of carbofuran degradation using immobilized Bacillus sp. strain DT1. Environ. Eng. Res. 27,1−23 (2022).

Faisal, M. & Hasnain, S. Growth stimulatory effects of ochrobactrum intermedium and Bacillus cereus on vigna radiata. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 43, 461–466 (2006).

Gomes, L. H., Duarte, K. M. R., Andrino, F. G. & Tavares, F. C. A. Simple DNA isolation method for Xanthomonas spp. Scientia Agricola. 57, 553–555 (2000).

Islam, M. R., Rahman, S. M. E., Rahman, M. M., Oh, D. H. & Ra, C. S. Effect of biogas slurry on maize fodder yield and quality. Turkish J. Agric. Forestry. 34, 91–99 (2010).

Jones, J. B. Laboratory Guide for Soil Testing and Plant Analysis , 2001

Kadakol, J. C., Kamanavalli, C. M. & Shouche, Y. Biodegradation of Carbofuran phenol by free and immobilized Klebsiella pneumoniae. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 27, 25–29 (2011).

Kalantary, R. R. et al. Biostimulation efficiency in phenanthrene-contaminated soil. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 12, 1–9 (2014).

Kalsi, A., Celin, S. M., Bhanot, P., Sahai, S. & Sharma, J. G. Eggshell-based bioformulation for remediation of RDX-contaminated soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 401, 123346 (2021).

Kalsi, A., Celin, S. M. & Sharma, J. G. Aerobic biodegradation of RDX by Janibacter Cremeus. Biotechnol. Lett. 42, 2299–2307 (2020).

Kaushik, P., Mishra, A., Malik, A. & Sharma, S. Production and shelf stability of fungal granules for environmental use. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 100, 70–78 (2015).

Khan, M. A. et al. Improved RDX remediation using dispersible Pelomonas aquatica granules. Environ. Technol. Innov. 00, 100594 (2020).

Khan, M. A. et al. Review on explosive-contaminated soil bioremediation advances. Chemosphere 294, 133641 (2022).

Lamichhane, K. M., Babcock, R. W. Jr., Turnbull, S. J. & Schenck, S. Molasses-assisted remediation of explosive-contaminated soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 243, 334–339 (2012).

Lafi, F. F. et al. Genome sequence of ochrobactrum intermedium SA148. Genome Announcements. 5, e01707–e01716 (2017).

Li, Z., Wang, X., Ni, Z., Bao, J. & Zhang, H. In-situ remediation of carbofuran-contaminated soil using immobilized white-rot fungi. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 29, 1237–1246 (2019).

Liu, X. R., Jiang, W. J., Yu, H. J. & Ning, X. J. Effect of diluted biogas slurry on tomato growth in greenhouse. Acta Hort. 927, 295–300 (2012).

Liu, W. K., Du, L. F. & Yang, Q. C. Biogas slurry amino acids reduce nitrate accumulation in lettuce. Acta Agriculturae Scand. Sect. B Soil. Plant. Sci. 58, 1–5 (2008).

Luka, Y., Highina, B. K. & Zubairu, A. Bioremediation as a solution to pollution. Am. J. Eng. Res. 7, 101–109 (2018).

M’rassi, A. G. et al. Isolation and characterization of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 15332–15346 (2015).

Majumdar, K. & Singh, N. Effect of soil amendments on Metribuzin behavior. Chemosphere 66, 630–637 (2007).

Mali, H. et al. Organophosphate pesticide toxicity and remediation: a review. J. Environ. Sci. 127, 234–250 (2023).

Muter, O. Current trends in bioaugmentation tools for bioremediation: a critical review of advances and gaps. Microorganisms 11, 710 (2023).

Nguyen, T. P. O., De Mot, R. & Springael, D. Genome sequence of carbofuran-mineralizing Novosphingobium sp. KN65.2. Genome Announcements. 3, e00764–e00715 (2015).

Patowary, R., Jain, P., Malakar, C. & Devi, A. Biodegradation of Carbofuran by Pseudomonas aeruginosa S07: biosurfactant production, plant growth promotion and metal tolerance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 115185–115198 (2023).

Pathak, V. M. et al. Effects of pesticides on environment, health and bioremediation strategies: a comprehensive review. Front. Microbiol. 13, 962619 (2022).

Peng, X. et al. Biodegradation of insecticide Carbofuran by paracoccus sp. YM3. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part. B. 43, 588–594 (2008).

Pimmata, P., Reungsang, A. & Plangklang, P. Comparative bioremediation of carbofuran-contaminated soil by natural attenuation, bioaugmentation and biostimulation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 85, 196–204 (2013).

Plangklang, P. & Reungsang, A. Bioaugmentation of Carbofuran degradation by burkholderia Cepacia PCL3 in bioslurry sequencing batch reactor. Process Biochem. 45, 230–238 (2010).

Plangklang, P. & Reungsang, A. Isolation and characterization of carbofuran-degrading burkholderia sp. PCL3 from phytoremediated soil. Chem. Ecol. 28, 253–266 (2012).

Plangklang, P. & Reungsang, A. Biodegradation of Carbofuran in sequencing batch reactor supplemented with immobilized burkholderia Cepacia on corncob. Chem. Ecol. 29, 44–57 (2013).

Porra, R. J., Thompson, W. A. & Kriedemann, P. E. Determination of chlorophylls a and b using precise extinction coefficients. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta - Bioenergetics. 975, 384–394 (1989).

Raimondo, E. E. et al. Enhanced Lindane biodegradation in soil by microbial bioaugmentation and biostimulation with sugarcane filter cake. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 190, 110143 (2020).

Rani, L. et al. Chemical pesticides and human/environmental risks: a comprehensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 283, 124657 (2021).

Rodríguez, A. et al. Omics approaches to pesticide biodegradation. Curr. Microbiol. 77, 545–563 (2020).

Rouachdia, R., Trea, F., Tichati, L. & Ouali, K. Toxicity response of Gambusia affinis to Carbofuran. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 21, 00000 (2023).

Ruiz-Hidalgo, K. et al. Carbofuran degradation by trametes versicolor using rice husk as lignocellulosic biomixture. Process Biochem. 49, 2266–2271 (2014).

Sayara, T., Borràs, E., Caminal, G., Sarrà, M. & Sánchez, A. Bioaugmentation and biostimulation in compost-based remediation of PAH-contaminated soil. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 65, 859–865 (2011).

Shahid, M. et al. Toxicity assessment of carbamate pesticides using microbial and plant assays. Chemosphere 278, 130372 (2021).

Sharma, A., Sharma, S., Sabir, N., El-Sheikh, M. A. & Alyemeni, M. Karanja cake and biogas slurry substrate influence on nematicidal potential of purpureocillium lilacinum. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 33, 101399 (2021).

Singh, D. P., Chhonkar, P. K. & Dwivedi, D. S. Manual on Soil, Plant and Water Analysis.

Singh, R. P. & Varshney, G. Influence of Carbofuran and organic amendments on nutrient availability and tomato growth. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 44, 2571–2586 (2013).

Soghandi, B. & Salimi, F. Rapeseed meal, soybean meal and NPK fertilizer as biostimulants for diesel-contaminated soil remediation. Soil. Sediment. Contam. 00, 1–21 (2023).

Tiwari, V. N., Tiwari, K. N. & Upadhyay, R. M. Effect of residue and biogas slurry incorporation on wheat yield and soil fertility. J. Indian Soc. Soil Sci. 48, 515–520 (2000).

Torres-Farradá, G. et al. White-rot fungi as tools for xenobiotic bioremediation: a review. J. Fungi. 10, 167 (2024).

Tyagi, M., da Fonseca, M. M. R. & de Carvalho, C. C. C. R. Bioaugmentation and biostimulation strategies for improving bioremediation efficiency. Biodegradation 22, 231–241 (2011).

Umar Mustapha, M., Halimoon, N. & Johari, W. Abd Shukor, M. Enhanced Carbofuran degradation using immobilized and free Enterobacter sp. cells. Molecules 25, 2771 (2020).

Vale, A. & Lotti, M. Organophosphate and carbamate insecticide toxicity. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 131, 149–168.

Wanaratna, P., Christodoulatos, C. & Sidhoum, M. Kinetics of RDX degradation by zero-valent iron. J. Hazard. Mater. 136, 68–74 (2006).

Wang, X., Li, Z., Yao, M., Bao, J. & Zhang, H. Plant-microorganism assisted degradation of Carbofuran in contaminated soil. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 84, 52–52 (2019).

Wang, X., Liu, L., Yao, M., Zhang, H. & Bao, J. Carbofuran removal by immobilized laccase in soil. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 26, 1305–1314 (2017).

Waqas, M. et al. Combined effect of Biochar and endophytes improves nutrient uptake in soybean. J. Zhejiang Univ. - Sci. B. 18, 109–124 (2017).

Xu, C., Cui, D., Lv, X., Zhong, G. & Liu, J. Biofilm-driven Carbofuran degradation by Pseudomonas stutzeri. Environ. Res. 229, 115894 (2023).

Yadav, S. et al. Water-dispersible granules of Microbacterium esteraromaticum enhance RDX remediation. J. Environ. Manage. 264, 110446 (2020).

Yan, Q. X. et al. Isolation and characterization of carbofuran-degrading Novosphingobium sp. FND-3. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 271, 207–213 (2007).

Yang, L. et al. Biodegradation of Carbofuran by Pichia anomala HQ-C-01 and application to soil remediation. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 47, 917–926 (2011).

Yu, F. B., Luo, X. P., Song, C. F., Zhang, M. X. & Shan, S. D. Biogas slurry improves soil fertility and tomato quality. Acta Agriculturae Scand. Sect. B Soil. Plant. Sci. 60, 262–268 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the guidance and support received from the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi and Amity University during the course of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.K: Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draftA.S.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing-Review & EditingS.S.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisitionG.R.: Writing-Review & Editing, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M.A., Sharma, A., Sharma, S. et al. Integrated microbial–organic strategy for carbofuran remediation: water-dispersible ochrobactrum granules with biogas slurry. Sci Rep 16, 3429 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33356-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33356-1