Abstract

In fuzzy rough set models, inner-product correlation serves as an effective evaluation function for feature selection, with its key advantage lying in its ability to characterize the minimum classification error inherent in the model. However, existing inner-product-based methods typically rely only on a subset of samples to approximate this error, making it difficult to fully and accurately capture the discriminative structure across the entire sample space. To address this limitation, this paper proposes a global-sample-oriented inner-product correlation criterion. By constructing a continuous and non-vanishing fuzzy membership structure over the entire universe of discourse, the proposed criterion significantly enhances the theoretical soundness and practical consistency of inner-product-based feature evaluation. Building upon this foundation and leveraging efficient matrix computation techniques, we design a static feature selection algorithm based on the Minimum Classification Error-based Feature Selection (MCEFS) criterion. Furthermore, to meet the demand for efficient updates in dynamic data environments, we develop a block-wise updating mechanism for the fuzzy decision and fuzzy relation matrices. We rigorously derive and prove a block-based incremental update strategy for the fuzzy lower approximation matrix, which effectively eliminates redundant recomputation of fuzzy lower approximations and substantially improves computational efficiency. Based on this strategy, we propose an incremental feature selection algorithm—Block Matrix-based MCEFS (BM-MCEFS). Finally, comprehensive comparative experiments on 12 public benchmark datasets validate the effectiveness and feasibility of the static MCEFS algorithm and clearly demonstrate the superior performance of BM-MCEFS in terms of computational efficiency and numerical stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In today’s data-driven world, high-dimensional datasets are becoming increasingly common, yet traditional learning algorithms often fail to process them effectively. As a result, feature selection methods, which can eliminate redundant information, have garnered widespread attention. By identifying a representative subset of features that retains the essential characteristics of the original data, feature selection simplifies the subsequent data analysis process. Currently, feature selection has become an important research topic in the field of pattern recognition1,2 and machine learning3,4,5, and has been widely used in practice6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. The fuzzy rough set theory proposed by Dubois and Prade15 is an important tool for feature selection using uncertainty in data16,17,18. In recent years, it has attracted the attention of many researchers19,20. Alnoor et al.21 proposed an application method based on Linear Diophantine Fuzzy Rough Sets and Multicriteria Decision-Making Methods, which can effectively identify oil transportation activities. Riaz et al.22 proposed linear Diophantine fuzzy sets (LDFS), which introduce reference parameters to constrain the membership and non-membership degrees, thereby demonstrating greater flexibility and robustness in multi-criteria decision-making. Yang et al.23 proposed a fuzzy rough set method that is aware of noise for feature selection. Ye et al.24 proposed a fuzzy rough set model for multi-attribute decision making for feature selection in multi-label learning. He et al.25 studied the selection of features of incomplete decision information systems based on fuzzy rough sets. Zhang et al.26 redefined the fuzzy rough set model of fuzzy cover based on the fuzzy rough set theory, providing a new thinking direction for the fuzzy rough set theory. Deng et al.27 conducted a theoretical analysis of the fuzzy rough set and proposed a feature selection algorithm that combines the distribution of labels. With the continuous deepening of the research, some researchers select features by constructing a fuzzy rough set feature evaluation function. Wang et al.28 introduced the distance measure into the fuzzy rough set and studied the calculation model of the iterative evaluation function based on variable distance parameters. Zhang et al.29 used information entropy to measure uncertainty for feature selection. Qian et al.30 proposed a label distribution feature selection algorithm based on mutual information. Qiu et al.31 studied the hierarchical feature selection method based on the Hausdorff distance. Sun et al.32 studied the fuzzy rough set online flow evaluation function for feature selection. However, An et al.33 proposed a feature selection method based on a rough relative fuzzy approximation of the maximum positive region by defining a relative fuzzy dependency function to evaluate the importance of features for decision-making. Liang et al.34 proposed a robust feature selection method based on the similarity of the kernel function and the relative classification uncertainty measure by using K nearest neighbor and Bayesian rules to generate an uncertainty measure. Zhang et al.35 enhanced the data fitting ability of fuzzy rough set theory by adopting an adaptive learning mechanism, and thus proposed a feature selection algorithm based on adaptive relative fuzzy rough set. Chen et al.36 conducted research on multi-source data and proposed an algorithm for fusion and feature selection by minimizing entropy to eliminate redundant features.

In general, the aforementioned approaches primarily construct dependency functions by extracting the maximum fuzzy membership degree of each sample with respect to the decision classes–i.e., preserving the maximal fuzzy positive region–to evaluate the importance of feature subsets. However, such methods utilize only the maximum membership value during data analysis and neglect the potentially valuable discriminative information embedded in the non-maximal membership degrees. To address this limitation, Wang et al.37 proposed a feature selection method based on the minimum classification error grounded in Bayesian decision theory, which posits that a smaller overlap between class-conditional probability density curves leads to a lower classification error. Their approach computes inner products between fuzzy membership degrees (excluding samples with zero membership values) to characterize this minimal classification error. Nevertheless, when inner-product correlations are computed solely on the basis of a subset of samples (i.e., partial samples), two critical issues arise. First, fuzzy membership functions derived from partial samples are often discontinuous or exhibit abrupt jumps over the global universe of discourse. This violates the continuity assumption that underlies the “minimal overlap \(\rightarrow\) minimal error” principle in Bayesian analysis, thus compromising its theoretical foundation and significantly degrading the reliability of the classification performance. Second, during feature evaluation, if inner-product correlations are computed from a subset of samples while the fuzzy positive region is estimated using the entire sample set, the two components rely on inconsistent sample bases. Specifically, under a given feature, the number of samples used to compute inner-product correlations may differ from that used to calculate the fuzzy positive region. In such cases, combining the inner-product correlation with the fuzzy positive region to compute the incremental dependency–and subsequently using this metric to assess the importance–lacks both reasonableness and consistency.

To more fully exploit the latent discriminative information inherent in the minimum classification error criterion and enhance the capability of inner-product correlation for feature selection, this paper makes the following contributions: Firstly, a non-zero fuzzy similarity relation function is constructed, and the decision information is fuzzified based on the class center sample strategy; Secondly, a continuous fuzzy membership degree curve is constructed on the universe of discourse based on the fuzzy membership function, and the degree of overlap between the fuzzy membership degree curves of different feature subsets is quantified using the inner product correlation, thereby enhancing the model’s screening ability for features. Finally, drawing on the matrix operation strategy, a matrix generation strategy for fuzzy membership degrees and inner product correlations is proposed to improve the computational efficiency of the algorithm. Based on the above research, this paper designs a feature selection algorithm based on the minimum classification error (Minimum Classification Error-based Feature Selection, MCEFS).

However, as data environments evolve, continuing to use static feature selection methods may result in a large number of redundant computations, thereby reducing the computational efficiency of the algorithm. Incremental feature selection methods, which leverage prior knowledge to select features from dynamically changing data, have thus garnered significant attention from researchers40,41,42,43. Sang et al.44 studied the incremental feature selection method for ordered data with dynamic interval values. Wang et al.45 proposed an incremental fuzzy tolerance rough set method for intuitionistic fuzzy information systems by updating the rough approximation of fuzzy tolerance. Zhang et al.46 proposed a novel incremental feature selection method using sample selection and accelerators based on the discriminative score feature selection framework. Yang et al.47 proposed an incremental feature selection method for interval-valued fuzzy decision information systems by studying two related incremental algorithms for sample insertion and deletion. Zhao et al.48 proposed a two-stage uncertainty measurement and designed an incremental feature selection algorithm capable of handling incomplete stream data. Xu et al.38 proposed a matrix-based incremental feature selection method based on weighted multi-granularity rough sets by minimizing the loss function to obtain the optimal weight vector, effectively improving the efficiency of feature selection algorithms. Zhao et al.39 based on fuzzy rough set theory, proposed a consistency principle to evaluate the significance of the feature, and combined with the principle of representative samples, designed three acceleration algorithms for incremental feature selection.(Table 1 presents a detailed comparison).

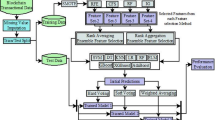

In summary, most existing incremental methods primarily focus on updating strategies for sample relationships when samples change, while paying less attention to updating strategies for fuzzy decisions and the generation of fuzzy rough approximations. To reduce redundant calculations of fuzzy rough approximations and enhance the efficiency of incremental algorithms, this paper has carried out the following work: First, we designed fuzzy relation and fuzzy decision matrices based on a block matrix updating strategy. Second, through an in-depth analysis of the calculation method for fuzzy lower approximations, we developed a block-based updating method for fuzzy lower approximation matrices to reduce redundant calculations of fuzzy approximations. Finally, we proposed an incremental feature selection algorithm based on block matrices (BM-MCEFS) to improve the algorithm’s adaptability to dynamic data environments.

The paper is organized as follows. Section “Preliminaries” introduces the fundamental concepts of fuzzy rough sets and fuzzy decision systems. In Section “A fuzzy rough model based on minimum classification error”, the proposed fuzzy similarity relation is incorporated into fuzzy decision information, based on which an inner-product dependency function is constructed and a corresponding static feature-selection algorithm is designed by matrix operations. Section “Incremental method based on block matrix” presents an incremental feature-selection algorithm that realizes dynamic updates using block-matrix techniques. Experimental datasets and an in-depth analysis of the results are provided in Section “Experimental results and analysis”. Finally, Section “Conclusions” summarizes the paper, discusses its limitations, and outlines directions for future research.

Preliminaries

To facilitate understanding of the subsequent content of this paper, this section provides a brief review of concepts related to fuzzy rough sets that are pertinent to this study.

Definition 1

49 Let the triplet (U, A, D) represent a decision table, in which \(U=\{x_{1},x_{2},...,x_{n}\}\) represents a non-empty finite domain of discourse, \(A=\{a_{1},a_{2},...,a_{m}\}\) is a condition set, \(D=\{d\}\) is a decision set. If A is a mapping to U, \(A{:}U\rightarrow [0,1]\), then A is called a fuzzy set on U, in which A(X) represents the degree of membership of X to A, therefore the fuzzy set in the domain U can be denoted as F(U), that is, \(F(U)=\{A|A{:}U\rightarrow [0,1]\}\).

Definition 2

50 Let U be the domain \(x_{i},x_{j}\in U\). If R represents the fuzzy similarity relation of any sample \(x_{i},x_{j}\) with respect to the conditional feature a, then it satisfies the following properties:

-

(1)

Reflexivity: \(R_{a}(x_{i},x_{i})=1\),

-

(2)

Symmetry: \(R_{a}(x_{i},x_{j})=R_{a}(x_{j},x_{i})\).

If there exists a feature subset \(B\subseteq A\), then the fuzzy similarity relation on B is defined as \(R_{B}=\bigcap _{{a\in B}}R_{a}\), that is, \(R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j})=\bigcap _{a\in B}R_{a}(x_{i},x_{j})\). The fuzzy granularity of the sample \(\left[ x_{i}\right] _{R_{B}}=\frac{R_{B}(x_{i},x_{1})}{x_{1}}+\frac{R_{B}(x_{i},x_{2})}{x_{2}}+...+\frac{R_{B}(x_{i},x_{n})}{x_{n}}\).

Definition 3

51 Let (U, A, D) be a decision table, \(B\subseteq A\), \(x_{i},x_{j}\in U\), if \(P\in F(U)\) is the fuzzy subset, then the fuzzy lower and upper approximations in B are respectively defined as follows:

In which “\({\vee }\)” and “\({\wedge }\)” denote the maximum and minimum operations, respectively. \(\underline{R}_{B}(P)(x_{i})\) represents the degree of certainty that the sample \(x_{i}\) is subordinate to P; \(\overline{R}_{B}(P)(x_{i})\) represents the degree of probability that the sample \(x_{i}\) is subordinate to P; then \((\underline{R}_{B}(P),\overline{R}_{B}(P))\) is called a pair of fuzzy approximation operators of P.

Definition 4

52 Let (U, A, D) be a decision table, where \(B\subseteq A\); decision D be divided into r crisp equivalence classes in the domain U, that is, \(U/D=\{D_{1},D_{2},...,D_{r}\}\). For any sample \(x_{i},x_{j}\in U\), if \(D_{s}(x_{i})= {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 1 & x_{i}\in D_{s} \\ 0 & x_{i}\not \in D_{s} \end{array}\right. }\), then the fuzzy lower and upper approximation can be simplified as:

Definition 5

53 Let (U, A, D) be a decision table, \(B\subseteq A\), \(U/D=\{D_{1},D_{2},...,D_{r}\}\), For any \(x\in U\), its degree of membership in the fuzzy positive region is defined as:

The fuzzy rough dependency of the decision D on the feature subset B is defined as:

In which \(\left| U\right|\) represents the cardinal number U of the domain. The fuzzy dependency function can be interpreted as the ratio of the cardinality of the fuzzy positive region to the total number of samples. In the theory of fuzzy rough sets, it is commonly used to evaluate the significance of a feature subset.

From Equation 6, it is evident that the fuzzy rough dependence can only retain the maximum dependence between the samples and the decisions. The analysis of the area of overlap between decisions, that is, the minimum classification error, is insufficient. Figure 1 depicts the basic process of feature selection based on classical fuzzy rough sets.

A fuzzy rough model based on minimum classification error

In this section, a method for generating fuzzy lower approximation matrices by incorporating matrix operations is proposed. Furthermore, based on the minimum classification error criterion, a novel inner product relevance function is constructed, and a corresponding static feature selection algorithm is designed accordingly. The flow of the static algorithm is shown in Fig. 2.

Definition 6

Let (U, A, D) be a decision table. If \(B\subseteq A\), \(\forall x_{i},x_{j}\in U\), then the fuzzy similarity relation of sample \(x_{i},x_{j}\) is defined as:

in which \(f(a,x_{i})\) represents the value of sample \(x_{i}\) under feature a. From Equation 7, it is apparent that \(R_{B}\) satisfies reflexivity, symmetry, and \(R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j})\ne 0\). Alternatively, letting \(|U|=n\), the fuzzy similarity relation matrix can be expressed as \(M_{{R_{B}}}=(fs_{ij})_{{n\times n}}\), in which \(fs_{ij}=R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j})\).

The advantage of Equation 7 lies first in its strictly positive nature, which ensures that the induced fuzzy lower approximation is continuous over the entire universe of discourse. Second, its wide mapping range (approximately (0,1]) enables relatively high sensitivity to differences in feature values. As evidenced by Table 3 derived from the decision table in Table 2–Equation 7 covers a wider range within (0, 1) than the similarity relation built with the Gaussian kernel. For the fuzzy similarities between sample \(\ x_{1}\) and the remaining samples in Table 2, Equation 7 gives a spread of 0.586 (max 0.722 -min 0.136), whereas the Gaussian kernel yields only 0.451. Equation 7 also discriminates samples better than the Euclidean-distance-based similarity: samples \(\ x_{2}\) and \(\ x_{3}\) are distinct, yet their Euclidean similarities to \(\ x_{8}\) are identical, while Equation 7 produces different values and thus distinguishes them effectively.

Definition 7

Let (U, A, D) be a decision table, \(\ x_{i},x_{j}\in U\), \(B\subseteq A\), \(D_{s}\in U/D\), then the class center sample can be defined as:

by incorporating the class center samples, the corresponding fuzzy decision can be derived from U/D as follows:

in which \(R_{B}(x,CS_{s})\) represents the degree of fuzzy similarity between the sample x and the center sample of the class \(CS_{s}\). For \(\forall x_{i}\in U\), \(FD_{s}= \{FD{(x_1)}, FD{(x_2)}, \ldots , FD{(x_n)}\}\), \(FD_{s}(x_{i})\in (0,1)\), \(\sum _{s=1}^{r}FD_{s}(x_{i})=1\). Let \(|U|=n\), \(|U/D|=r\), the fuzzy decision matrix can be expressed as \(M_{{FD}}=\left( fd_{{is}}\right) _{{n\times r}}\), in which \(fd_{is}=FD_{s}(x_{i})\).

Definition 8

Let (U, A, D) be a decision table, \(B\subseteq A\), \(\ x_{i},x_{j}\in U\). \(FD_{s}\) is the fuzzy decision corresponding to \(D_{s}\), the fuzzy lower and upper approximations are defined as:

From Equation 7, we can see \(R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j})\in (0,1]\) and obtain \(0\le (1-R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j}))<1\). Since \(FD_{s}(x_{i})\in (0,1)\), \(0<\left( 1-R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j}))\vee FD_{s}(x_{j})\right) <1\), \(0<\wedge _{x_{j}\in U}\left( 1-R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j}))\vee FD_{s}(x_{j})\right) <1\), that is, \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)\in (0,1)\). It can be seen that in the domain U, \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)\) generates an uninterrupted fuzzy lower approximation membership curve, as shown in Fig. 3.

According to \(M_{R_{B}}\) and \(M_{FD}\), combined with the matrix operation, the fuzzy lower and upper approximation matrix can be converted into the following:

In which \((1-M_{R_{B}})\) represents the reverse of elements in \(M_{R_{B}}\). Let “\(\odot\)” denote the union set of each element of each row in \((1-M_{R_{B}})\) and each element of the column corresponding to the matrix \(M_{FD}\), then take the intersection of all the union sets, that is, “\(\odot\)” is equivalent to “\(\wedge (\vee )\)”. With the same argument: “\(\otimes\)” represents the operation process “\(\vee (\wedge )\)”. Here we can get \(M_{\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})}=\left( \underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x_{i})\right) _{n\times r}\).

Property 1

Let \(B\subseteq A\), \(B_{1}\subseteq B_{2}\subseteq B\), U/D represents the clear division of decision on the domain, FD represents fuzzy decision corresponding to U/D, then the following formula holds:

(1) If \(D_{s}\in U/D\), then \(\underline{R}_{B}(D_{s})\) ≤\(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})\), \(\overline{R}_{B}(D_{s})\) ≥ \(\overline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})\),

(2) If \(B_{1}\subseteq B_{2}\), then \(\underline{R}_{B_{1}}(FD_{s})\subseteq \underline{R}_{B_{2}}(FD_{s})\), \(\overline{R}_{B_{2}}(FD_{s})\subseteq \overline{R}_{B_{1}}(FD_{s})\).

Proof

(1) If so \(D_{s}\in U/D\), from Equation 3, we can obtain \(\underline{R}_{B}(D_{s})(x)=\underset{x_{j}\in D_{s}}{\operatorname {\operatorname {\wedge }}}\{1-R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j})\}\). FD represents the fuzzy decision corresponding to U/D, and from Equation 10, we can obtain \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x_{i})=\wedge _{x_{j}\in U}\{(1-R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j}))\vee FD_{s}(x_{j})\}\). Therefore, we can get \(1-R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j})\le (1-R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j}))\vee FD_{s}(x_{j})\), thus \(\underline{R}_{B}(D_{s})\le \underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})\). Quod erat demonstrandum.

In the same way, it can be demonstrated that \(\overline{R}_{B}(D_{s})\ge \overline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})\)

(2) From \(B_{1}\subseteq B_{2}\) we have \(R_{B_{1}}\le R_{B_{1}}\), that is, \(1-R_{B_{1}}(x_{i},x_{j})\le 1-R_{B_{2}}(x_{i},x_{j})\), and then we can obtain \((1-R_{B_{1}}(x_{i},x_{j}))\vee FD_{s}(x_{j})\le (1-R_{B_{2}}(x_{i},x_{j}))\vee FD_{s}(x_{j})\). From Equation 10 we have \(\underline{R}_{B_{1}}(FD_{s})\le \underline{R}_{B_{2}}(FD_{s})\), that is, \(\underline{R}_{B_{1}}(FD_{s})\subseteq \underline{R}_{B_{2}}(FD_{s})\). Quod erat demonstrandum.

In the same way, it can be demonstrated that \(\overline{R}_{B_{2}}(FD_{s})\subseteq \overline{R}_{B_{1}}(FD_{s})\). \(\square\)

Clearly, from Property 1, \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})\) satisfies monotonicity, and relative to \(\underline{R}_{B}(D_{s})\), the fuzzy lower approximation \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})\) is expanded.

Definition 9

Let (U, A, D) be a decision table, \(B\subseteq A\), \(x_{i}\in U\), the fuzzy positive region and the fuzzy rough dependence are redefined, respectively, as:

Clearly, combined with Fig. 3, \(Pos_{B}(FD)\) is the solid line part, and the dotted line part represents the overlapping area of the fuzzy lower approximate membership curve, that is, the minimum classification error.

Definition 10

Let (U, A, D) be a decision table, \(B\subseteq A\), \(x\in U\), \(|U/D|=r\), FD be the fuzzy decision corresponding to U/D, the inner product relevance function is then defined as:

in which U is the domain and r is the number of decision categories. Since \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{x})(x)\in (0,1)\), \(0<\omega _{B}(FD)<1\) can be obtained.

Next, this paper will clearly demonstrate the key role that the inner product dependency function plays through a simple and intuitive example.

Example 1

Let \(U=\{x_{1},x_{2},x_{3}\}\), \(B,C\subseteq A\), \(U/D=\{D_{1},D_{2},D_{3}\}=\{\{x_{1}\},\{x_{2}\},\{x_{3}\}\}\). FD represents fuzzy decision corresponding to U/D. If the lower approximation membership degrees of the sample to \(D_1, D_2, D_3\) are \(\underline{R}_{B}({FD_1})\) = \(\frac{0.6}{x_1} + \frac{0.1}{x_2} + \frac{0.2}{x_3}\), \(\underline{R}_{C}(FD_{1})\) = \(\frac{0.6}{x_{1}}+\frac{0.3}{x_{2}}+\frac{0.1}{x_{3}}\); \(\underline{R}_{B}({FD_2})\) = \(\frac{0.3}{x_1} + \frac{0.6}{x_2} + \frac{0.4}{x_3}\), \(\underline{R}_{C}(FD_{2})\) = \(\frac{0.5}{x_{1}}+\frac{0.6}{x_{2}}+\frac{0.1}{x_{3}}\); \(\underline{R}_{B}({FD_3})\) = \(\frac{0.3}{x_1} + \frac{0.4}{x_2} + \frac{0.6}{x_3}\), \(\underline{R}_{C}(FD_{3})\) = \(\frac{0.2}{x_{1}}+\frac{0.3}{x_{2}}+\frac{0.6}{x_{3}}\). Obviously, if only based on the maximal fuzzy positive region \(Pos_{_B}(FD)=\bigcup _{s=1}^{r}\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)\) = \(\frac{0.6}{x_{_1}}+\frac{0.6}{x_{_2}}+\frac{0.6}{x_{_3}}\) and \(Pos_{c}(FD)\) = \(\frac{0.6}{x_{1}}+\frac{0.6}{x_{2}}+\frac{0.6}{x_{3}}\), then according to the fuzzy dependency function \(\gamma _{B}(FD)\) = \(\frac{\sum _{x\in U}Pos_{B}(FD)(x)}{|U|}\), \(\gamma _{_B}(FD)=\gamma _{_C}(FD)\) can be obtained. At this point, it can be observed that the fuzzy dependency function only retains the maximum fuzzy approximation degree of the sample. At this time, it is impossible to distinguish the feature set B and C. If the inner product-dependent function is used, then we can obtain \(\omega _B(FD)=\frac{1}{\mid U\mid ^2 r(r-1)}\sum _{s\ne t}\sum _{x\in U}\underline{R}_B(FD_s)(x)\underline{R}_B(FD_t)(x)=0.0228\), and similarly \(\omega _{C}(FD)=0.0204\). At this point, it can be observed that the classification capabilities of the feature sets B and C are obviously different.

At this point, it is obvious that the method based on inner product functions can effectively enhance the feature recognition ability.

Theorem 1

Let (U, A, D) be a decision table, \(B\subseteq A\), \(M_{\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})}\) = \(\left( \underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)\right) _{{n\times r}}\), if \(M_{SD}\) = \(((M_{\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})})^{\textrm{T}}(M_{\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})}))\), then \(\sum _{s\ne t}\sum _{x\in U}\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{t})\) = \(\sum _{i=1}^{r}\sum _{j=1}^{r}a_{ij}-\sum _{i=1}^{r}a_{ii}\). Where \(a_{ij}\) is an element in the matrix \(M_{SD}\).

Proof

From Definition 8, the transpose matrix of \(M_{\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})}\) is \(\left( M_{\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})}\right) ^{\textrm{T}}\) . Let \(a_{ij}\) be an element in the matrix \(M_{SD}=\left( a_{ij}\right) _{r\times r}\), \(\forall x_{i},x_{j}\in U\), it is evident that \(a_{ij}=\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{t})\), and when \(s=t\), \(a_{ii}=\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{t})\) can be obtained. Therefore, \(\sum _{s\ne t}\sum _{x\in U}\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{t})(x)=\sum _{i=1}^{r}\sum _{j=1}^{r}a_{ij}-\sum _{i=1}^{r}a_{ii}\). Quod erat demonstrandum. \(\square\)

By Theorem 1, the calculation of the inner product dependent function can be transformed into a matrix operation.

Theorem 2

Let (U, A, D) be a decision table. If \(B\subseteq A\), then \(\omega _{B}(FD)\le \omega _{A}(FD)\).

Proof

From \(B\subseteq A\), \(D_{i}\in U/D\), we can get \(R_{A}\le R_{B}\), \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{i})\) ≤ \(\underline{R}_{A}(FD_{i})\). Thus, for \(\forall x\in U\), \(D_{s},D_{t}\in U/D\), we can get \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)\) ≤ \(\underline{R}_{A}(FD_{s})(x)\), \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{t})(x)\) ≤ \(\underline{R}_{A}(FD_{t})(x)\). Therefore, \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{t})(x)\) ≤ \(\underline{R}_{A}(FD_{s})(x)\underline{R}_{A}(FD_{t})(x)\), combined with Equation 16, \(\omega _{B}(FD)\le \omega _{A}(FD)\) can be obtained. Quod erat demonstrandum. \(\square\)

From Theorem 2, the inner product dependence function satisfies the monotonicity requirement on the domain U.

Theorem 3

Let (U, A, D) be a decision table, \(\forall x\in U\), \(B\subseteq A\). If \(\omega _{B}(FD)=\omega _{A}(FD)\), then \(\gamma _{B}(FD)=\gamma _{A}(FD)\).

Proof

For \(\forall x\in U\), since \(B\subseteq A\), \(D_{t},D_{s}\in U/D\), we can get \(R_{A}\le R_{B}\), \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)\le \underline{R}_{A}(FD_{s})(x)\), \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{t})(x)\le \underline{R}_{A}(FD_{t})(x)\). Consequently, \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{t})(x)\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)\) ≤ \(\underline{R}_{A}(FD_{t})(x)\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)\) can be obtained, that is, \(\sum _{s\ne t}\sum _{x\in U}\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{t})(x)\) ≤ \(\sum _{s\ne t}\sum _{x\in U}\underline{R}_{A}(FD_{s})(x)\underline{R}_{A}(FD_{t})(x)\), From Equation 16, \(\omega _{_B}(FD)\le \omega _{A}(FD)\) can be obtained. Therefore, for \(\forall x\in U\), \(D_{s}\in U/D\), \(\omega _{B}(FD_{s})\) = \(\omega _{A}(FD_{s})\) if and only if \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)\) = \(\underline{R}_{A}(FD_{s})(x)\), and since \(Pos(FD)(x)\) = \(\bigcup \underline{R}(FD_{s})(x)\), \(\gamma _{B}(FD)\) = \(\sum _{i=1}^{n}Pos(FD)(x_{i})/|U|\), we can get \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)\) = \(\underline{R}_{A}(FD_{s})(x)\), then \(Pos_{B}(FD)\) = \(Pos_{A}(FD)\) can be obtained, therefore, when \(\omega _{B}(FD)\) = \(\omega _{A}(FD)\), \(\gamma _{B}(FD)\) = \(\gamma _{A}(FD)\). Quod erat demonstrandum. \(\square\)

Remark 1

Theorem 3 does not necessarily hold in the opposite way. Suppose that when \(\gamma _{B}(FD)=\gamma _{A}(FD)\), \(Pos_{B}(FD)(x)=Pos_{A}(FD)(x)\) can be obtained from the fuzzy rough dependence, that is,

clearly, for \(\forall x\in U\), \(Pos_{B}(FD)(x) = Pos_{A}(FD)(x)\) can be obtained with the only need of satisfying:

but it can be known from Theorem 3 that when \(\underline{R}_{B}(FD_{s})(x)=\underline{R}_{A}(FD_{s})(x)\), \(\omega _{B}(FD)=\omega _{A}(FD)\), Therefore, when \(Pos_{B}(FD)=Pos_{A}(FD)\), \(\omega _{B}(FD)=\omega _{A}(FD)\) is not necessarily true.

Fuzzy lower approximation membership curves of feature subsets H and F. In the feature spaces H and F, if the analysis is based only on the maximum fuzzy positive region, the classification performance of the two spaces appears similar. However, when the minimum classification error is also considered, the distinction in classification capability between these two spaces becomes apparent.

It is evident from the above that the relevance of the inner product encompasses the classification information captured by the fuzzy rough dependency. However, the fuzzy rough dependency cannot fully represent the classification information conveyed by the inner product relevance function.

As shown in Fig. 4, the domain U illustrates the superimposed distributions of the fuzzy lower approximation membership curves for feature subsets H and F. When \(Pos_{H}(FD)=Pos_{F}(FD)\), the feature subsets H and F exhibit the same classification ability according to fuzzy rough dependency. However, according to Bayesian Decision Theory, a smaller overlap between membership curves corresponds to a lower classification error rate. Therefore, it can be observed from Fig. 4 that in the feature subset F, the overlap area of the membership curve of the fuzzy lower approximation \(\underline{R}_{F}(FD_{1})\), \(\underline{R}_{F}(FD_{2})\), \(\underline{R}_{F}(FD_{3})\) is obviously larger than that of the membership curve of \(R_{H}(FD_{1})\), \(R_{H}(FD_{2})\), \(R_{H}(FD_{3})\) in the feature subset H. Thus, if \(\forall x_{k}\in U\), E is \(\underline{R}_{H}(FD_{1})(x_{k})\setminus \underline{R}_{F}(FD_{1})(x_{k})\), P is \(\underline{R}_{F}(FD_{2})(x_{k})\), J is \(\underline{R}_{H}(FD_{2})(x_{k})\), then the inner product is \(\underline{R}_{F}(FD_{1})(x_{k})\underline{R}_{F}(FD_{2})(x_{k})>\underline{R}_{H}(FD_{1})(x_{k})\underline{R}_{H}(FD_{2})(x_{k})\). It follows that in the domain U, the relevance of the inner product can reflect the degree of fuzzy lower approximation overlap of different feature spaces, that is, the effect of minimum classification error on the classification of the data. Therefore, although the feature subsets H and F have the same fuzzy positive region, the feature subset H has a greater classification ability than the feature subset F according to Bayesian Decision Theory.

Definition 11

Let (U, A, D) be a decision table, \(B\subseteq A\). If B satisfies the following conditions:

-

(1)

\(\gamma _{B}(FD)=\gamma _{A}(FD)\),

-

(2)

\(\forall a{\in }B,\gamma _{B-\{a\}}(FD){<}\gamma _{B}(FD)\).

Then B is called a reduction of A, that is, B is the smallest feature subset with the same classification ability as A.

If \(a\in A-B\), then the importance of the feature a to B is defined as:

The numerator \(\left( \gamma _{{B\cup {a}}}(FD)-\gamma _{B}(FD)\right)\) represents the increase in fuzzy dependency induced by the addition of the feature a, while the denominator is defined as the square root of the function based on the inner-product \({\omega _{B}(FD)}\). Clearly, the stronger the discriminative power of the feature a, the larger the resulting measure \(\psi\).therefore, the importance measure proposed in this formulation jointly accounts for both the increase in fuzzy dependency and the minimization of the classification error (as reflected by the term of inner-product). Consequently, Equation 17 provides a more accurate and comprehensive assessment of the classification capability of a candidate feature.

Example 2

Let Table 2 be a decision table, in which \(U=\{x_{1},x_{2},...,x_{9}\}\), \(A=\{a_{1},a_{2},...,a_{5}\}\), \(U/D=\{D_{1},D_{2},D_{3}\}=\{\{x_{1},x_{2},x_{3}\},\) \(\{x_{4},x_{5},x_{6}\},\{x_{7},x_{8},x_{9}\}\}\), \(|U|=9\). Then the calculation example is as follows.

-

(1)

From Definition 6, the fuzzy similarity relation matrix \(M_{R_{A}}\) can be obtained as follows:

$$\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0.625 & 0.722 & 0.411 & 0.282 & 0.210 & 0.142 & 0.136 & 0.111 \\ 0.625 & 1 & 0.508 & 0.495 & 0.311 & 0.226 & 0.150 & 0.147 & 0.118 \\ 0.722 & 0.508 & 1 & 0.370 & 0.316 & 0.236 & 0.159 & 0.153 & 0.124 \\ 0.411 & 0.495 & 0.370 & 1 & 0.449 & 0.419 & 0.274 & 0.260 & 0.213 \\ 0.282 & 0.311 & 0.316 & 0.449 & 1 & 0.612 & 0.421 & 0.405 & 0.311 \\ 0.210 & 0.226 & 0.236 & 0.419 & 0.612 & 1 & 0.582 & 0.560 & 0.426 \\ 0.142 & 0.150 & 0.159 & 0.274 & 0.421 & 0.582 & 1 & 0.656 & 0.674 \\ 0.136 & 0.147 & 0.153 & 0.260 & 0.405 & 0.560 & 0.656 & 1 & 0.574 \\ 0.111 & 0.118 & 0.124 & 0.213 & 0.311 & 0.426 & 0.674 & 0.574 & 1 \end{bmatrix}_{9 \times 9}$$ -

(2)

For \(D_{1}\), the degree of intra-class similarity is: \(\sum _{x_{j}\in D_{1}}R_{A}(x_{1},x_{j})\)=1.422, \(\sum _{x_{j}\in D_{1}}R_{A}(x_{2},x_{j})\)=1.416, \(\sum _{x_{j}\in D_{1}}R_{A}(x_{3},x_{j})\)=1.265. Therefore, from Equation 8, we can get \(CS_{1}=x_{1}\), and similarly \(CS_{2}=x_{5}\), \(CS_{3}=x_{7}\). From Equation 9, \(FD_{1}(x_{1})\)=0.702 can be obtained, and similarly, \(FD_{2}(x_{1})\)=0.198, \(FD_{3}(x_{1})\)=0.100. The fuzzy decision matrix \(M_{{FD}}\) is shown as follows:

$$\begin{bmatrix} 0.702 & 0.198 & 0.100 \\ 0.576 & 0.286 & 0.138 \\ 0.603 & 0.264 & 0.133 \\ 0.362 & 0.396 & 0.242 \\ 0.166 & 0.587 & 0.247 \\ 0.150 & 0.436 & 0.388 \\ 0.091 & 0.269 & 0.640 \\ 0.114 & 0.338 & 0.548 \\ 0.101 & 0.284 & 0.615 \end{bmatrix}_{9 \times 3}$$ -

(3)

From Equation 12 and Equation 13, the fuzzy lower approximation matrix \(M_{\underline{R}_{A}(FD)}\) and fuzzy upper approximation matrix \(M_{\overline{R}_{A}(FD)}\) can be obtained as:

$$\begin{aligned} & \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0.375 & 0.278 & 0.589 & 0.718 & 0.790 & 0.858 & 0.864 & 0.889 \\ 0.375 & 0 & 0492 & 0.505 & 0.689 & 0.774 & 0.850 & 0.853 & 0.882 \\ 0.278 & 0.492 & 0 & 0.630 & 0.684 & 0.764 & 0.841 & 0.847 & 0.876 \\ 0.589 & 0.505 & 0.630 & 0 & 0.551 & 0.581 & 0.726 & 0.740 & 0.787 \\ 0.718 & 0.689 & 0.684 & 0.551 & 0 & 0.388 & 0.579 & 0.595 & 0.689 \\ 0.790 & 0.774 & 0.764 & 0.581 & 0.388 & 0 & 0.418 & 0.440 & 0.574 \\ 0.858 & 0.850 & 0.841 & 0.726 & 0.579 & 0.418 & 0 & 0.344 & 0.326 \\ 0.864 & 0.853 & 0.847 & 0.740 & 0.595 & 0.440 & 0.344 & 0 & 0.426 \\ 0.889 & 0.882 & 0.876 & 0.787 & 0.689 & 0.574 & 0.326 & 0.426 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \odot \begin{bmatrix} 0.702 & 0.198 & 0.100 \\ 0.576 & 0.286 & 0.138 \\ 0.603 & 0.264 & 0.133 \\ 0.362 & 0.396 & 0.242 \\ 0.166 & 0.587 & 0.247 \\ 0.150 & 0.436 & 0.388 \\ 0.091 & 0.269 & 0.640 \\ 0.114 & 0.338 & 0.548 \\ 0.101 & 0.284 & 0.615 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.576 & 0.198 & 0.100 \\ 0.505 & 0.286 & 0.138 \\ 0.576 & 0.264 & 0.133 \\ 0.362 & 0.396 & 0.242 \\ 0.166 & 0.436 & 0.247 \\ 0.150 & 0.418 & 0.388 \\ 0.091 & 0.269 & 0.418 \\ 0.114 & 0.338 & 0.440 \\ 0.101 & 0.284 & 0.548 \end{bmatrix}_{9 \times 3} \\ & \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0.625 & 0.722 & 0.411 & 0.282 & 0.210 & 0.142 & 0.136 & 0.111 \\ 0.625 & 1 & 0.508 & 0.495 & 0.311 & 0.226 & 0.150 & 0.147 & 0.118 \\ 0.722 & 0.508 & 1 & 0.370 & 0.316 & 0.236 & 0.159 & 0.153 & 0.124 \\ 0.411 & 0.495 & 0.370 & 1 & 0.449 & 0.419 & 0.274 & 0.260 & 0.213 \\ 0.282 & 0.311 & 0.316 & 0.449 & 1 & 0.612 & 0.421 & 0.405 & 0.311 \\ 0.210 & 0.226 & 0.236 & 0.419 & 0.612 & 1 & 0.582 & 0.560 & 0.426 \\ 0.142 & 0.150 & 0.159 & 0.274 & 0.421 & 0.582 & 1 & 0.656 & 0.674 \\ 0.136 & 0.147 & 0.153 & 0.260 & 0.405 & 0.560 & 0.656 & 1 & 0.574 \\ 0.111 & 0.118 & 0.124 & 0.213 & 0.311 & 0.426 & 0.674 & 0.574 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \otimes \begin{bmatrix} 0.702 & 0.198 & 0.100 \\ 0.576 & 0.286 & 0.138 \\ 0.603 & 0.264 & 0.133 \\ 0.362 & 0.396 & 0.242 \\ 0.166 & 0.587 & 0.247 \\ 0.150 & 0.436 & 0.388 \\ 0.091 & 0.269 & 0.640 \\ 0.114 & 0.338 & 0.548 \\ 0.101 & 0.284 & 0.615 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.702 & 0.396 & 0.247 \\ 0.625 & 0.396 & 0.247 \\ 0.702 & 0.370 & 0.247 \\ 0.495 & 0.449 & 0.415 \\ 0.362 & 0.587 & 0.421 \\ 0.362 & 0.587 & 0.582 \\ 0.274 & 0.436 & 0.640 \\ 0.260 & 0.436 & 0.640 \\ 0.213 & 0.426 & 0.640 \end{bmatrix}_{9 \times 3} \end{aligned}$$The fuzzy positive region and the inner product matrix are:

\(Pos_{A}(FD)=\bigcup _{s=1}^{r}\underline{R}_{A}(FD_{s})=\) \({\begin{bmatrix}0.576&0.505&0.576&0.396&0.436&0.418&0.418&0.440&0.548 \end{bmatrix}}_{\scriptstyle 1 \times 9}^{\scriptstyle T}\) ,

\(M_{SD}=(M_{\underline{R}_{A}(FD)})^{\textrm{T}}(M_{\underline{R}_{A}(FD)})=\) \(\begin{bmatrix} 1.131 & 0.781 & 0.534 \\ 0.781 & 0.980 & 0.877 \\ 0.534 & 0.877 & 0.985 \end{bmatrix}\). Thus, the inner product \(M_{SD}=\sum _{i=1}^{m}\sum _{j=1}^{n}a_{ij}-\sum _{i=1}^{m}a_{ii}\)=4.384 can be obtained.

In terms of the above analysis, this paper designs a feature selection algorithm based on minimum classification error (MCEFS). The pseudo-code of the algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1.

In Algorithm 1, the parameter \(\delta\) is used to terminate the main loop. In fact, the optimal value of \(\delta\) varies for different datasets. Assuming the sample size, the number of features, and the number of decision classes are n, m, and c respectively, the first step initializes the feature selection conditions; the third step constructs the fuzzy similarity relation, with a computational complexity of \(O(m(n^2))\); the fourth step processes the fuzzy decision, with a computational complexity of \(O(nr)\); the fifth step calculates the fuzzy lower approximation, with a computational complexity of \(O((n^2)r)\); based on this, the sixth step of the algorithm calculates the inner product correlation under the candidate features according to the fuzzy lower approximation value, with a computational complexity of \(O(n(r^2))\); the eighth step of the algorithm calculates the fuzzy rough dependency degree respectively and combines the increment of the fuzzy rough dependency degree with the inner product correlation to evaluate the increment of the dependency degree brought by the new feature; the ninth step selects the feature with the highest increment of dependency degree from the candidate features and adds it to the feature subset. The eleventh step judged the increment of the dependency degree brought about by the new feature. When the difference between after and before addition is greater than the preset parameter \(\delta\), the algorithm continues to loop from step 1 to step 9; otherwise, the algorithm terminates and outputs the final result of the selection of features. Therefore, in the process of finding the optimal feature subset, it may need to be evaluated \(O\left( \frac{m + m^2}{2}\right)\) times. Thus, the total complexity of Algorithm 1 is \(O\left( (\frac{m + m^2}{2})+(mn^2)+(nr) \right)\).

Example 3

Let Table 2 (U, A, D) be a decision table, examples of the feature selection process are as follows: Let \(B=\emptyset\), \(\delta =0.03\). After the first traversal, for \(a_{k}\in A-B\), \(\psi (a_{k},B,D)\) is calculated as follows: \(\psi (a_{1},B,D)\)=1.115, \(\psi (a_{2},B,D)\)=1.104, \(\psi (a_{3},B,D)\)=1.079, \(\psi (a_{4},B,D)\)=1.067, \(\psi (a_{5},B,D)\)=1.063; we can get \(B=\{a_{1}\}\). After the second traversal, \(\psi (a_{2},B,D)\)=0.069, \(\psi (a_{3},B,D)\)=0.174, \(\psi (a_{3},B,D)\)=0.168, \(\psi (a_{5},B,D)\)=0.025; we can get \(B=\{a_{1},a_{3}\}\). After the third traversal, \(\psi (a_{2},B,D)\)=0.155, \(\psi (a_{4},B,D)\)=0.120, \(\psi (a_{5},B,D)\)=0.094; we can get \(B=\{a_{1},a_{3},a_{2}\}\). After the forth traversal, \(\psi (a_{4},B,D)\)=0.139, \(\psi (a_{5},B,D)\) =0.106; we can get \(B=\{a_{1},a_{3},a_{2},a_{4}\}\). After the fifth traversal, \(\gamma _{B\cup \{a_{5}\}}-\gamma _{B}<0.03\), the traversal is terminated. Thus, \(B=\{a_{1},a_{3},a_{2},a_{4}\}\).

This section has first introduced a method for generating fuzzy rough approximation matrices with the aid of matrix operations. Subsequently, an inner product relevance function was constructed in the domain and its properties are analyzed. Finally, a static feature selection algorithm is proposed which takes into account the minimum classification error.

Incremental method based on block matrix

To effectively address the challenges of dynamic data environments, this section proposes an incremental feature selection method based on a block matrix framework, developed through an in-depth analysis of fuzzy rough sets. By constructing a block matrix model, the proposed method enables efficient handling of dynamic data and facilitates rapid updating of the results of feature selection. The framework of the incremental method is shown in Fig. 5.

Theorem 4

Let (U, A, D) be a decision table, \(B\subseteq A\), \(|U|=n\), and the new samples \(U^+=\{x_{n+1},x_{n+2},...,x_{n+\overline{n}}\}\), \(U^{add}=U\cup U^{+}\) be the domain after the samples are increased. If the fuzzy similarity relation matrix \(M_{R_{B}}=(fs_{{ij}})_{n\times n}\) is updated to \(M_{R_{B}}^{add}=(\overline{fs}_{ij})_{(n+\overline{n})\times (n+\overline{n})}\), then the update method would be as follows:

Proof

According to the idea of a block matrix, the matrix \(M_{R_{B}}^{add}\) after increasing the sample can be regarded as a matrix composed of four block matrices, that is, \(M_{R_B}^{add}= \begin{bmatrix} M_{n\times n}^A & M_{n\times \overline{n}}^B \\ M_{\overline{n}\times n}^C & M_{\overline{n}\times \overline{n}}^D \end{bmatrix}\). When \(1\le i,j\le n\), the block matrix \(M_{n\times n}^{A}=\left( fs_{{ij}}\right) _{n\times n}\) represents the fuzzy similarity relation matrix before the sample update; the block matrix \(M_{n\times \overline{n}}^{B}\) represents when \(1\le i\), \(1+n\le j\le n+\overline{n}\), \(M_{n\times \overline{n}}^{B}=R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j})\); the block matrix \(M_{\overline{n}\times n}^{C}\) represents when \(j\le n\), \(1+n\le i\le n+\overline{n}\), \(M_{\overline{n}\times n}^{C}=R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j})\); the block matrix \(M_{\overline{n} \times \overline{n}}^{D}\) represents when \(1+n\le i\le n+\overline{n}\), \(1+n\le j\le n+\overline{n}\), \(M_{\overline{n}\times \overline{n}}^{D}=R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j})\). Based on the above analysis, quod erat demonstrandum. \(\square\)

Theorem 5

Let (U, A, D) be a decision table, \(B\subseteq A\), \(|U|=n\), \(U^+=\{x_{n+1},x_{n+2},...,x_{n+\overline{n}}\}\), \(U^{add}=U\cup U^{+}\), \({CS}_{s}\) be the center sample of class \(({D}_{s})\), \(D_{s}\in U^{add}/D\), FD is the fuzzy decision corresponding to U/D, \(x_{i},x_{j}\in D_{s}\), if the fuzzy decision matrix \(M_{{FD}}=(fd_{{is}})_{{n\times r}}\) is updated to \(M_{FD}^{add}=(\overline{fd}_{{is}})_{(n+\overline{n})\times r}\), then the update method would be as follows:

Proof

Let \(D_{s}\in U^{add}/D\), \(x_{i},x_{j}\in D_{s}\), when \(\sum R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j})\le \sum R_{B}(CS_{s},x_{j})\), show that the class center sample \({CS}_{s}\) remains unchanged. Now, the fuzzy decision matrix \(M_{FD}^{add}\) can be regarded as a matrix composed of two block matrices, namely \(M_{FD}^{add}= \begin{bmatrix} M_{n\times r}^{E}&M_{\overline{n}\times r}^{F} \end{bmatrix}^{\textrm{T}}\). When \(1<i<n,s\le r\), the block matrix \(M_{{n\times r}}^{E}=M_{{FD}}\), that is, the original fuzzy decision matrix remains unchanged; when \(n+1<i<n+\overline{n},s\le r\), the block matrix \(M_{\overline{n}\times r}^{F}=FD_{s}(x_{i})\), that is, only the fuzzy decision of the newly added samples needs to be calculated. But when \(\sum R_{B}(x_{i},x_{j})>\sum R_{B}(CS_{s},x_{j})\), it shows that the center sample of the class \({CS}_{s}\) changes, and now \(M_{{FD}}^{add}=FD_{s}(x_{i})\). That is, fuzzy decision-making requires recalculations. Quod erat demonstrandum.

From the above theorem, it can be observed that when the number of samples increases, the update of the fuzzy decision matrix can be described by the block matrix.

Theorem 6

Let \(X\cup Y=U\), \(X\cap Y=\emptyset\), FD be the fuzzy decision corresponding to U/D, for \(\forall x_{i},x_{j}\in U\), the following equation holds.

Proof

\(\square\)

If \(X=U\), \(Y=U^{+}\), \(U^{add}=U\cup U^{+}\), then from Equation 20, the fuzzy approximation of \(U^{add}\) is equivalent to the union of fuzzy approximations of X and Y.

According to the analysis above, if the matrix \(M_{BF}=(1-M_{n\times \overline{n}}^{B})\odot M_{\overline{n}\times r}^{F}\) can be obtained from the block matrix \(M_{n\times \overline{n}}^{B}\) of the matrix \(M_{R_{B}}^{add}\), and the block matrix \(M_{{\overline{n}\times r}}^{F}\) of the matrix \(M_{FD}^{add}\), it is noticeable that the matrix \(M_{BF}\) is the fuzzy lower approximation obtained by the fuzzy relation of the new sample and the fuzzy decision of the new sample. Meanwhile, it is of the same type of \(M_{\underline{R}_{B}(FD)}\).

Theorem 7

Let (U, A, D) be a decision table, \(B\subseteq A\), \(|U|=n\), \({CS}_{s}\) be the center sample of class \(({D}_{s})\), \(U^+=\{x_{n+1},x_{n+2},...,x_{n+\overline{n}}\}\), \(U^{add}=U\cup U^{+}\). If \(M_{{BF}}=(bf_{{is}})_{{n\times r}}\), the fuzzy lower approximation matrix \(M_{\underline{R}_{B}(FD)}=(rd_{{is}})_{n\times r}\) is updated to \(M_{\underline{R}_{B}(FD)}^{add}=\left( \overline{rd}_{{is}}\right) _{(n+\overline{n})\times r}\), then the update method would be as follows:

Proof

Suppose that the class center sample remains, then the fuzzy lower approximation matrix \(M_{\underline{R}_{B}(FD)}^{add}\) after the sample has been increased can be regarded as a matrix composed of two block matrices, that is, \(M_{\underline{R}_{B}(FD)}^{add}= \begin{bmatrix} {M_{n\times r}^{G}}&{M_{\overline{n}\times r}^{H}} \end{bmatrix}^{\textrm{T}}\). Therefore, when \(1<i<n,s\le r\), if \(rd_{{is}}\le bf_{{is}}\), then \(\overline{rd}_{{is}}=rd_{{is}}\), can be obtained by Theorem 6. If \(rd_{{is}}>bf_{{is}}\), \(\overline{rd}_{is}=bf_{is}\) can be obtained, that is, \(M_{n\times r}^{G}=M_{BF}\wedge M_{\underline{R}_{B}(FD)}\). When \(n+1<i<n+\overline{n},s\le r\), \(M_{\overline{n}\times r}^{H}=\left( \left( 1-(M_{\overline{n}\times n}^{C}+M_{\overline{n}\times \overline{n}}^{D})\right) \odot M_{FD}^{add}\right)\). Quod erat demonstrandum. \(\square\)

Clearly, from Theorem 7, when the number of samples increases, if \({CS}_{s}\) remains unchanged, the incremental method of the block matrix can effectively improve the update efficiency of the fuzzy lower approximation matrix. Again, it must be noted that the precondition of the incremental method is that \({CS}_{s}\) remains unchanged.

Example 4

Let Table 4 be a decision table with increasing samples, in which \(U^{+}=\{x_{10},x_{11}\}\), \(U^{add}/D=\{D_{1},D_{2},D_{3}\}=\left\{ \{x_{1},x_{2},x_{3},x_{10}\},\{x_{4},x_{5},x_{6},x_{11}\},\{x_{7},x_{8},x_{9}\}\right\}\). If \({CS}_{s}\) keeps unchanged, the calculation example is as follows:

-

(1)

The fuzzy similarity matrix \(M_{R_A}^{add}= \begin{bmatrix} M_{n\times n}^A & M_{n\times \overline{n}}^B \\ M_{\overline{n}\times n}^C & M_{\overline{n}\times \overline{n}}^D \end{bmatrix}\) and the fuzzy decision matrix \(M_{\underline{R}_{A}(FD)}^{add}= \begin{bmatrix} {M_{n\times r}^{G}}&{M_{\overline{n}\times r}^{H}} \end{bmatrix}^{\textrm{T}}\) are updated as follows:

$$\left[ \begin{array}{ccccccccc|cc} 1 & 0.625 & 0.722 & 0.411 & 0.282 & 0.210 & 0.142 & 0.136 & 0.111 & 0.800 & 0.243 \\ 0.625 & 1 & 0.508 & 0.495 & 0.311 & 0.226 & 0.150 & 0.147 & 0.118 & 0.635 & 0.272 \\ 0.722 & 0.508 & 1 & 0.370 & 0.316 & 0.236 & 0.159 & 0.153 & 0.124 & 0.643 & 0.270 \\ 0.411 & 0.495 & 0.370 & 1 & 0.449 & 0.419 & 0.274 & 0.260 & 0.213 & 0.373 & 0.437 \\ 0.282 & 0.311 & 0.316 & 0.449 & 1 & 0.612 & 0.421 & 0.405 & 0.311 & 0.238 & 0.716 \\ 0.210 & 0.226 & 0.236 & 0.419 & 0.612 & 1 & 0.582 & 0.560 & 0.426 & 0.178 & 0.544 \\ 0.142 & 0.150 & 0.159 & 0.274 & 0.421 & 0.582 & 1 & 0.656 & 0.674 & 0.122 & 0.412 \\ 0.136 & 0.147 & 0.153 & 0.260 & 0.405 & 0.560 & 0.656 & 1 & 0.574 & 0.117 & 0.430 \\ 0.111 & 0.118 & 0.124 & 0.213 & 0.311 & 0.426 & 0.674 & 0.574 & 1 & 0.096 & 0.373 \\ \hline 0.800 & 0.635 & 0.643 & 0.373 & 0.238 & 0.178 & 0.122 & 0.117 & 0.096 & 1 & 0.206 \\ 0.243 & 0.272 & 0.270 & 0.437 & 0.716 & 0.544 & 0.412 & 0.430 & 0.373 & 0.206 & 1 \end{array}\right] _{11 \times 11} ; \begin{bmatrix} 0.702 & 0.198 & 0.100 \\ 0.576 & 0.286 & 0.138 \\ 0.603 & 0.264 & 0.133 \\ 0.362 & 0.396 & 0.242 \\ 0.166 & 0.587 & 0.247 \\ 0.150 & 0.436 & 0.388 \\ 0.091 & 0.269 & 0.640 \\ 0.114 & 0.338 & 0.548 \\ 0.101 & 0.284 & 0.615 \\ \hline 0.690 & 0.205 & 0.105 \\ 0.177 & 0.522 & 0.301 \end{bmatrix}_{11 \times 3} .$$ -

(2)

Next, the fuzzy lower approximation matrix \(M_{\underline{R}_{A}(FD)}^{add}\) is updated. Firstly, \(M_{BF}\) is calculated:

$$(1 - M_{n \times \overline{n}}^{B}) \odot M_{\overline{n} \times r}^{F} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.200 & 0.757 \\ 0.365 & 0.728 \\ 0.357 & 0.730 \\ 0.627 & 0.562 \\ 0.762 & 0.284 \\ 0.822 & 0.456 \\ 0.878 & 0.588 \\ 0.883 & 0.570 \\ 0.904 & 0.627 \end{bmatrix} \odot \begin{bmatrix} 0.690 & 0.205 & 0.105 \\ 0.177 & 0.522 & 0.301 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.690 & 0.205 & 0.200 \\ 0.690 & 0.365 & 0.365 \\ 0.690 & 0.357 & 0.357 \\ 0.562 & 0.562 & 0.562 \\ 0.284 & 0.522 & 0.301 \\ 0.456 & 0.522 & 0.456 \\ 0.588 & 0.588 & 0.588 \\ 0.570 & 0.570 & 0.570 \\ 0.627 & 0.627 & 0.627 \end{bmatrix}_{9 \times 3} .$$ -

(3)

Combined with matrix \(M_{\underline{R}_{A}(FD)}\), block matrix \(M_{n\times r}^{G}=M_{\underline{R}_{A}(FD)}\wedge M_{BF}\). From Equation 20, it could be obtained as the block matrix:

\(M_{\overline{n}\times r}^{H}=\left( \left( 1-(M_{\overline{n}\times n}^{C}+M_{\overline{n}\times \overline{n}}^{D})\right) \odot M_{FD}^{add}\right) =\begin{bmatrix} 0.576 & 0.200 & 0.105 \\ 0.177 & 0.456 & 0.284 \end{bmatrix}\) .

Thus, the updated fuzzy lower approximation matrix \(M_{\underline{R}_{A}(FD)}^{add}\) is:

$$\begin{bmatrix} M_{n \times r}^{G} \\ M_{\overline{n}\times r}^{H} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.576 & 0.198 & 0.100 \\ 0.505 & 0.286 & 0.138 \\ 0.576 & 0.264 & 0.133 \\ 0.362 & 0.396 & 0.242 \\ 0.166 & 0.436 & 0.247 \\ 0.150 & 0.418 & 0.388 \\ 0.091 & 0.269 & 0.418 \\ 0.114 & 0.338 & 0.440 \\ 0.101 & 0.284 & 0.548 \\ \hline 0.576 & 0.200 & 0.105 \\ 0.177 & 0.456 & 0.284 \end{bmatrix}_{11 \times 3} .$$

In light of the examples above, we see clearly that the incremental update of the fuzzy lower approximation matrix can be realized by combining the block matrix. As a result, this paper proposes an incremental feature selection based on the block matrix Algorithm 2 (BM-MCEFS).

In Algorithm 2, the computational complexity of updating the fuzzy relation matrix in Step 4 is \(O(2n\bar{n}+\bar{n}^2)\), that of updating the fuzzy decision matrix in Step 6 is \(O(\bar{n}\times r)\), and the complexity of computing the fuzzy lower approximation matrix in Step 7 is \(O(\bar{n}\times r)\). The calculation of relevance based on the inner-product in Step 12 has complexity \(O((n+\bar{n})\times r^2)\). Since finding the optimal feature subset may require \(O\left( \frac{m + m^2}{2}\right)\) evaluations, the overall complexity of Algorithm 2 is \(O\left( (\frac{m + m^2}{2})+(2n\bar{n}+\bar{n}^2)+2(\bar{n}r)+((n+\bar{n})r^2) \right)\).

It is self-evident that, when the class centers remain stable, it is only necessary to calculate the fuzzy relationships and fuzzy decisions of the newly added samples. This can effectively avoid a large number of redundant calculations and enable the algorithm to achieve optimal performance. Conversely, if the sample centers of the class change frequently, it can be seen from Equation 9 that the fuzzy decisions will also change accordingly, and in this case the algorithm will not be able to achieve the best performance.

Experimental results and analysis

Against three representative methods: the acceleration algorithm based on fuzzy rough set information entropy46 (AFFS), the heuristic algorithm with variable distance parameters based on distance measures28 (FRDM), the fuzzy rough set feature selection method based on relative distance33 (MPRB), Incremental feature selection with fuzzy rough sets for dynamic data sets54 (IRS) and incremental feature selection based on fuzzy rough sets for hierarchical classification55 (ASIRA).

The experimental environment is configured as follows: an Acer A850 equipped with a 12th-generation Intel Core i7-12700 CPU (2.10 GHz) running Windows 11. All algorithms are implemented in Python. The evaluation criteria include four main aspects: algorithm robustness, computation time, reduct size (i.e., number of selected features), and classification accuracy. To reduce experimental error, each data set is tested 10 times and the final results are reported as average values.

A total of 12 datasets, obtained from the UCI Machine Learning Repository , are used in the experiments and summarized in Table 5. Two widely-used classifiers, namely Support Vector Machine (SVM) and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), are employed to evaluate the performance of the feature selection algorithms. Before the experiments, all datasets (see Table 5) were normalized using the following preprocessing formula:

In which \({\overline{f}(a,x)}\) represents the normalized information of sample x under feature a.

Inner product relevance analysis

To analyze the relationship among inner product relevance (IPR), fuzzy rough dependency (FRD), and classification accuracy of the MCEFS algorithm, this paper randomly generates 12 feature subsets from the CB and TME datasets. The IPR, FRD and classification accuracy of each feature subset are calculated using a ten-fold cross-validation on KNN (K=3) and SVM. The results are presented in Tables 6 and 7.

From Tables 6 and 7, it can be observed that the minimum classification error (IPR of the inner product function) is related to the classification ability of the feature subsets. For example, in the CB dataset, the 9th group of feature subsets has the lowest IPR value and achieves the highest classification accuracy on both the KNN and SVM classifiers; conversely, the 10th group has a higher IPR value and correspondingly lower classification accuracy on both classifiers. In addition, the fifth and sixth groups have nearly identical FRD values; however, the sixth group has a smaller IPR and higher classification accuracy, indicating that when FRD remains constant, the minimum classification error can identify features that are more valuable for classification performance. Nevertheless, this conclusion does not hold universally. For example, in the TME dataset, although the fifth group has a relatively low IPR value, its classification accuracy is also low on both classifiers. This discrepancy arises because the minimum classification error captures only the information related to misclassification within the feature subset, which represents just one aspect of the overall classification capability. Therefore, relying solely on the minimum classification error cannot comprehensively reflect the classification performance of a feature subset.

Additionally, in this study, the threshold \(\delta\) was set to 0. Using MCEFS, a series of feature subsets were successfully generated on the four datasets of TME, CB, WQ and SHB. In the SVM and KNN classifiers, based on the feature importance determined by the MCEFS algorithm, features were gradually added from high to low, and at the same time, features were also gradually added according to the unsorted feature sequence in the original data set (RAW) as a control group. The classification accuracy curves that changed with the increase in the number of features were plotted. The experimental results are illustrated in Figs. 6 and 7. The experimental results show that the MCEFS algorithm can significantly improve the classification accuracy of the data. For example, in Fig. 6, when the MCEFS algorithm obtains the highest classification accuracy on the CB dataset, its performance exceeds the highest classification accuracy of RAW; in the SHB dataset, the highest classification accuracy obtained by the MCEFS algorithm on both classifiers exceeds the classification accuracy of RAW. Therefore, it can be concluded that the MCEFS algorithm improves the accuracy of data classification.

To verify the sensitivity of the MCEFS algorithm to the parameter \(\delta\), this study conducted experiments on four randomly selected datasets (CB, HCE, TME, and GL) and validated the results of the selection of features using two classifiers, SVM and 3NN. During the threshold selection process, each dataset was tested multiple times to determine the fluctuation range of its threshold. Subsequently, the classifiers were employed to test the accuracy of the feature selection results, thereby identifying the threshold sensitivity interval for each dataset. Finally, within this sensitivity interval, a uniform step size was set to adjust the threshold and test the changes in reduction length, classification accuracy, and stability. The experimental results are shown in Figs. 8 and 9.

As can be seen in Figs. 8 and 9, as the parameter \(\delta\) increases, the feature subset selected by the MCEFS algorithm gradually decreases in size, and its classification accuracy on the classifiers also exhibits certain fluctuations. However, within a specific range of values \(\delta\), these fluctuations are effectively controlled at a low level. Taking the Glass data set as an example (see Figs. 8 and 9), when \(\delta\) ranges from 0.002 to 0.012, the classification accuracy remains relatively stable despite continuous changes in the parameter. This result indicates that the MCEFS algorithm demonstrates strong robustness during parameter adjustment.

Comparison of static feature selection algorithms

To evaluate the efficiency of feature selection of the MCEFS algorithm, this paper uses KNN and SVM classifiers to assess the optimal classification accuracy achieved by four comparison algorithms in 12 datasets. Based on these results, the optimal subsets of features and their corresponding running times are determined, as summarized in Table 8. Furthermore, the classification accuracy results for the 12 datasets, based on the selected optimal feature subsets, are presented in Fig. 10. In these tables, the values underlined indicate the highest classification accuracy achieved for each dataset.

The results of the experiment in Table 8 demonstrate that all four algorithms successfully achieved dimensionality reduction. Among them, the MCEFS algorithm generally selected fewer features than the other methods on most datasets. However, in the ROE dataset, the number of features selected by MCEFS exceeded that of the other three algorithms.

By comparing the results in Table 8 and Fig. 10, it is evident that the MCEFS algorithm consistently outperformed the others in terms of classification accuracy in both KNN and SVM classifiers. Specifically, of the original 18 features, MCEFS effectively selected only 9, achieving a substantial reduction in dimensionality.

In terms of computational time, the MCEFS algorithm performs comparably to other algorithms. However, for datasets with a large number of features (such as the CB dataset), the runtime of the MCEFS algorithm is relatively longer. This is mainly because the comparison algorithms only calculate the lower approximations of the samples, while MCEFS additionally computes the inner product correlation between the samples, thus increasing the computational time. It should be noted that MCEFS has achieved higher classification accuracy in most datasets. For example, on the SHB dataset, the MCEFS algorithm achieved higher classification accuracy even when selecting the smallest feature subset; on the IR dataset, the MCEFS algorithm significantly outperformed the other two algorithms in terms of accuracy. These results indicate that the method based on the minimum classification error can effectively compensate for some of the shortcomings of fuzzy rough dependency and improve the classification accuracy of the data.

To assess the robustness of the MCEFS algorithm, 10% and 20% label noise was introduced into five selected datasets. Then, a feature selection was performed and the optimal classification accuracy was recorded. The experimental results are presented in Tables 9 and 10. The results show that, compared to the other algorithms, MCEFS consistently achieves higher classification accuracy under both noise levels. This performance advantage is primarily attributed to the incorporation of the minimum classification error criterion into the MCEFS framework.

To further analyze and compare the statistical performance of the four algorithms, the Friedman test56 and the Nemenyi post-hoc test are applied based on the classification accuracy results presented in Fig. 10. These two statistical methods are defined as follows.

Where, n and k respectively represent the number of data sets and the number of algorithms, \(\textrm{R}_{i}\) represent the average ranking order of the algorithm in all algorithms.

Where, \(\alpha\) represents the degree of significance, and \(q_{\alpha }\) is the critical value at a given point.

If the null hypothesis based on the Friedman test is rejected, the Nemenyi post-hoc test is then employed to assess the significance of pairwise differences between algorithms. Specifically, if the difference in average rankings between two algorithms exceeds the critical distance (CD), their performance is considered significantly different. In the corresponding diagram, significant differences are indicated by the absence of connecting lines between algorithms, whereas non-significant differences are shown by horizontal lines connecting them.

Here, \(n=4\), \(k=12\), if \(\alpha = 0.05\), then the critical value56 \(q_\alpha = 2.569\). The Friedman statistics calculated by SVM and KNN are 7.815 and 3.86 respectively, and are greater than the critical value of 2.569. Based on this, in this paper the null hypothesis of the equivalence of the SVM and KNN models is rejected, indicating that there are significant differences between the algorithms. Next, according to Equation 25, we get CD=1.35. Therefore, the CD diagram of four feature selection algorithms under SVM and KNN is shown in Fig. 11. As can be clearly seen from Fig. 11, The Nemenyi test indicates that, under the SVM and KNN classifiers, the MCEFS algorithm is significantly superior to other algorithms, highlighting its competitiveness.

Comparison of feature selection algorithms under sample increase

In order to test the efficiency of the incremental feature selection algorithm after the sample is added, this section randomly divides each data set into two parts, of which 50% of the sample is used as the original data, and the remaining 50% of the sample is used as the test data set. Each time, 10% of the test sample is randomly added, and until it reaches 50% accumulatively, 10% is added each time, up to 5 times. Based on the feature subset corresponding to the optimal classification accuracy selected by the algorithm, and recording the time consumed by each algorithm in selecting these feature subsets, the computational time of different algorithms can be accurately evaluated. The time required for different algorithms to calculate based on 12 datasets is shown in Fig. 12.

For each subgraph in Fig. 12, the abscissa represents the increase in the proportion of the sample, and the ordinate represents the added calculation time of the six algorithms. In Fig. 12, it is evident that in the 12 data sets, with increasing proportion of samples, the calculation time of all algorithms shows an upward trend, but compared to other algorithms, the calculation time duration of the BM-MCEFS algorithm is the least. At the same time, ten-fold cross-validation is used to test the change in the classification accuracy of the data in the KNN and SVM classifiers after adding samples with different ratio columns in 12 data sets. The experimental results are shown in Tables 11 and 12. Among them, ‘RAW’ represents the accuracy of classification under all features. Since the BM-MCEFS algorithm is an incremental algorithm optimized for the MCEFS algorithm, when the added samples are consistent, the classification accuracy error of the data is small. Therefore, in the testing of incremental algorithms, this paper compares the BM-MCEFS algorithm with the AFFS algorithm, the FRDM algorithm, and the MPRB algorithm and the IRS algorithm and the ASIRA algorithm.

It is not difficult to see from Tables 11 and 12 that under the KNN classifier, the average accuracy of the BM-MCEFS algorithm on 12 data sets is better than other algorithms. At the same time, under the SVM classifier, the classification accuracy of the BM-MCEFS algorithm is significantly higher than that of other algorithms. For example, on the HCE dataset in Table 11, the average accuracy of the BM-MCEFS algorithm is 47.10, while the average accuracy of the AFFS algorithm is 44.32, while the FRDM algorithm being 44.36 and the MPRB 44.16.

To evaluate the robustness of the BM-MCEFS algorithm, 10% label noise was introduced into a portion of sequentially added samples in four selected datasets. The feature selection was then performed under these noisy conditions. In the experiment, ”RAW” denotes the classification accuracy using the original feature set, while ”Noised data” refers to the classification accuracy obtained after injecting 10% of label noise into the full feature set. The experimental results are presented in Figs. 13 and 14. As observed, the BM-MCEFS algorithm consistently achieves higher classification accuracy across most noise levels. This performance is primarily attributed to the fact that BM-MCEFS inherits the minimum classification error criterion from the MCEFS algorithm.

To further assess the statistical performance of the five algorithms, a comparative analysis was conducted based on computation time, as shown in Fig. 12, under a condition where 50% of the samples were incrementally added. The resulting Critical Difference (CD) diagram is also provided.

In this analysis, \(n=7\), \(k=12\), if \(\alpha = 0.05\), then the critical value56 \(q_\alpha = 2.949\). The Friedman statistic is 46.64, which exceeds the critical value, leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis of equivalence. This indicates significant differences among the algorithms. According to Equation 25, CD = 2.60. As shown in Fig. 15, the Nemenyi test confirms that the BM-MCEFS algorithm performs significantly better than the others, further highlighting its competitiveness.

Conclusions

Feature selection is an effective approach to high-dimensional data analysis, as it reduces data redundancy while preserving essential discriminative information. Incremental learning further enhances this process by leveraging prior knowledge to efficiently adapt to dynamically evolving data environments. This paper investigates feature selection methods based on fuzzy rough sets and identifies a key limitation of the classical fuzzy positive region: its failure to fully exploit the rich membership information embedded in the fuzzy lower approximation. To address this issue, we propose a novel Minimum Classification Error-based Feature Selection framework (MCEFS). The method constructs continuous membership curves over the universe of discourse and quantifies inter-class separability using inner product correlation, thereby effectively uncovering discriminative information beyond the traditional fuzzy positive region. Moreover, by integrating efficient matrix computation strategies, the generation of the fuzzy lower approximation is significantly accelerated, substantially improving the computational efficiency of static feature selection. Building on this foundation, we further develop an incremental variant–BM-MCEFS–that employs a block matrix mechanism to dynamically update both the fuzzy relation matrix and the fuzzy decision matrix. By reusing and incrementally refining sub-blocks of these matrices, the algorithm avoids full recomputation during data updates, greatly reducing time overhead in dynamic scenarios. Experimental results on 12 benchmark datasets demonstrate that both MCEFS and BM-MCEFS achieve high classification accuracy while offering markedly superior computational efficiency compared to state-of-the-art methods. The proposed algorithms hold significant practical value in real-world applications involving highly dimensional, streaming, or frequently updated, streaming data. For example: In smart urban management57, they can dynamically identify key indicators–such as traffic flow, environmental quality, and land use–to support resilient city planning; in agricultural cooperation systems58, they enable effective selection of environmental and socio-economic features, facilitating multidimensional sustainability assessments that go beyond yield alone; in industrial production optimization59, they support real-time monitoring and feature-driven anomaly detection, thereby improving resource utilization and system stability.These capabilities align closely with the current social demands for sustainable development, digital transformation, and intelligent decision-making.

Nevertheless, the proposed method has certain limitations. Its effectiveness relies on the relative stability of the underlying data distribution, particularly the continuity of class-center sample structures. When class centers undergo abrupt shifts due to concept drift, the incremental update mechanism may lag behind. Additionally, although inner product correlation significantly strengthens feature discriminability, it also introduces additional computational overhead. In future work, we will focus on three main directions: designing block-update strategies that respond to feature-level changes to better capture local dynamics; extending the use of inner product correlation to broader supervised learning tasks, such as multi-label and imbalanced learning; integrating incremental and batch processing mechanisms to enhance robustness against concept drift. Our ultimate goal is to develop a more scalable, adaptive, and interpretable feature selection framework that can be effectively deployed across diverse real-world applications.

Data availability

The datasets supporting this study can be obtained from the corresponding author or downloaded directly from the provided URLs. The basic information of the 12 datasets used in this paper is as follows: Markelle Kelly, Rachel Longjohn, Kolby Nottingham, The UCI Machine Learning Repository (https://archive.ics.uci.edu/). The specific download URLs for each dataset are as follows: MAGIC Gamma Telescope: Available at https://archive.ics.uci.edu/datasets/?search=MAGIC+Gamma+Telescope. Room Occupancy Estimation: Available at https://archive.ics.uci.edu/datasets/?search=Room+Occupancy+Estimation. Shill+Bidding: Available at https://archive.ics.uci.edu/datasets/?search=Shill+Bidding. Wine Quality: Available at https://archive.ics.uci.edu/datasets/?search=Wine+Quality. Iranian Churn: Available at https://archive.ics.uci.edu/datasets/?search=Iranian+Churn. Hepatitis C Virus for Egyptian patients: Available at https://archive.ics.uci.edu//datasets/?search=Hepatitis+C+Virus+for+Egyptian+patients. Turkish Music Emotion: Available at https://archive.ics.uci.edu/datasets/?search=Turkish+Music+Emotion. TUANDROMD: Available at https://archive.ics.uci.edu/datasets/?search=TUANDROMD. Semeion Handwritten Digit: Available at https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset//178/semeion+handwritten+digit. Glass: Available at https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/42/glass+identification. Connectionist Bench: Available at https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/151/connectionist+bench+sonar+mines+vs+rocks. Iris: Available at https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/53/iris.

References

Yin, Z., Liu, L., Chen, J., Zhao, B. & Wang, Y. Locally robust eeg feature selection for individual-independent emotion recognition. Expert Syst. Appl.162, 113768 (2020).

Sheikhpour, R., Saberi-Movahed, F., Jalili, M. & Berahmand, K. Semi-supervised feature selection with concept factorization and robust label learning. Pattern Recognit. 112317 (2025).

Kou, G. et al. Evaluation of feature selection methods for text classification with small datasets using multiple criteria decision-making methods. Appl. Soft Comput.86, 105836 (2020).

Sheikhpour, R., Mohammadi, M., Berahmand, K., Saberi-Movahed, F. & Khosravi, H. Robust semi-supervised multi-label feature selection based on shared subspace and manifold learning. Inf. Sci.699, 121800 (2025).

Fedorka P, Buchuk R, Klymenko M, Saibert F, Petrushyn A. The use of adaptive artificial intelligence (ai) learning models in decision support systems for smart regions. Journal of Research, Innovation and Technologies4, 99–115 (2025).

Nejadshamsi, S., Bentahar, J., Eicker, U., Wang, C. & Jamshidi, F. A geographic-semantic context-aware urban commuting flow prediction model using graph neural network. Expert Syst. Appl.261, 125534 (2025).

Qiu, Y., Bouraima, M., Badi, I., Stević, Ž & Simic, V. A decision-making model for prioritizing low-carbon policies in climate change mitigation. Chall. sustain12, 1–17 (2024).

Chaoui, G., Yaagoubi, R. & Mastere, M. Integrating geospatial technologies and multi-criteria decision analysis for sustainable and resilient urban planning. Chall. Sustain13, 122–134 (2025).

Fedorka, P., Buchuk, R., Klymenko, M., Saibert, F. & Petrushyn, A. The use of adaptive artificial intelligence (ai) learning models in decision support systems for smart regions. Journal of Research, Innovation and Technologies7, 99–115 (2025).

Krause, A. & Köppel, J. A multi-criteria approach for assessing the sustainability of small-scale cooking and sanitation technologies. Challenges in Sustainability6, 1–19 (2018).

Qiu, Y., Bouraima, M., Badi, I., Stević, Ž & Simic, V. A decision-making model for prioritizing low-carbon policies in climate change mitigation. Chall. sustain12, 1–17 (2024).

Chaoui, G., Yaagoubi, R. & Mastere, M. Integrating geospatial technologies and multi-criteria decision analysis for sustainable and resilient urban planning. Challenges in Sustainability13, 122–134 (2025).

Terentieva, K., Karpenko, I., Yarova, T., Shkvyria, O. & Pasko, Y. Technological innovation in digital brand management: Leveraging artificial intelligence and immersive experiences. Journal of Research, Innovation and Technologies4, 201–223 (2025).

Wolf, B. M., Häring, A.-M. & Heß, J. Strategies towards evaluation beyond scientific impact: Pathways not only for agricultural research. Organic Farming1, 3–18 (2015).

Dubois, D. & Prade, H. Rough fuzzy sets and fuzzy rough sets. International Journal of General System17, 191–209 (1990).

Lang, G., Li, Q., Cai, M., Yang, T. & Xiao, Q. Incremental approaches to knowledge reduction based on characteristic matrices. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern.8, 203–222 (2017).

Liang, J., Wang, F., Dang, C. & Qian, Y. A group incremental approach to feature selection applying rough set technique. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng.26, 294–308 (2012).

Sun, L., Zhang, X., Qian, Y., Xu, J. & Zhang, S. Feature selection using neighborhood entropy-based uncertainty measures for gene expression data classification. Inf. Sci.502, 18–41 (2019).

Feng, Y., Hua, Z. & Liu, G. Partial reduction algorithms for fuzzy relation systems. Knowl.-Based Syst.188, 105047 (2020).

Theerens, A. & Cornelis, C. Fuzzy rough sets based on fuzzy quantification. Fuzzy Sets Syst.473, 108704 (2023).

Alnoor, A. et al. Toward a sustainable transportation industry: Oil company benchmarking based on the extension of linear diophantine fuzzy rough sets and multicriteria decision-making methods. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst.31, 449–459 (2022).

Riaz, M. & Hashmi, M. R. Linear diophantine fuzzy set and its applications towards multi-attribute decision-making problems. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems37, 5417–5439 (2019).

Yang, X., Chen, H., Li, T. & Luo, C. A noise-aware fuzzy rough set approach for feature selection. Knowl.-Based Syst.250, 109092 (2022).

Ye, J., Zhan, J. & Xu, Z. A novel multi-attribute decision-making method based on fuzzy rough sets. Computers & Industrial Engineering155, 107136 (2021).

He, J. et al. Attribute reduction in an incomplete categorical decision information system based on fuzzy rough sets. Artif. Intell. Rev.55, 5313–5348 (2022).

Zhang, K. & Dai, J. Redefined fuzzy rough set models in fuzzy covering group approximation spaces. Fuzzy Sets Syst.442, 109–154 (2022).

Deng, Z. et al. Feature selection for label distribution learning based on neighborhood fuzzy rough sets. Appl. Soft Comput.169, 112542 (2025).

Wang, C., Huang, Y., Shao, M. & Fan, X. Fuzzy rough set-based attribute reduction using distance measures. Knowl.-Based Syst.164, 205–212 (2019).

Zhang, X., Mei, C., Chen, D. & Li, J. Feature selection in mixed data: A method using a novel fuzzy rough set-based information entropy. Pattern Recogn.56, 1–15 (2016).

Qian, W., Huang, J., Wang, Y. & Shu, W. Mutual information-based label distribution feature selection for multi-label learning. Knowl.-Based Syst.195, 105684 (2020).

Qiu, Z. & Zhao, H. A fuzzy rough set approach to hierarchical feature selection based on hausdorff distance. Appl. Intell.52, 11089–11102 (2022).

Sun, Y. & Zhu, P. Online group streaming feature selection based on fuzzy neighborhood granular ball rough sets. Expert Syst. Appl.249, 123778 (2024).

An, S. et al. Relative fuzzy rough approximations for feature selection and classification. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics53, 2200–2210 (2023).

Liang, P., Lei, D., Chin, K. & Hu, J. Feature selection based on robust fuzzy rough sets using kernel-based similarity and relative classification uncertainty measures. Knowl.-Based Syst.255, 109795 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Wang, C., Huang, Y., Ding, W. & Qian, Y. Adaptive relative fuzzy rough learning for classification. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst.32, 6267–6276 (2024).

Chen, X., Lai, L. & Luo, M. A novel fusion and feature selection framework for multisource time-series data based on information entropy. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. (2025).

Wang, C., Qian, Y., Ding, W. & Fan, X. Feature selection with fuzzy-rough minimum classification error criterion. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst.30, 2930–2942 (2021).