Abstract

This study developed a simple and label-free fluorescent probe for deferiprone quantification in exhaled breath condensate (EBC) samples. For that, UiO-66, synthesized in a one-step process with the solvothermal method, along with ferric ions, provided a selective system for deferiprone detection. Deferiprone formed a complex with ferric ions, and the resulting complex quenched the fluorescence intensity of UiO-66 through an inner filter effect process. The probe demonstrated good sensitivity, with a detection limit of 0.005 mg.L− 1 and a linear range of 0.016-1.0 mg.L− 1, and performed reliably in the analysis of deferiprone in EBC samples of the patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deferiprone is an orally administered iron chelator indicated for the treatment of transfusional iron overload. Regulatory authorities have expanded the drug’s approval beyond its initial sanction as an alternative for thalassemia and hemochromatosis patients intolerant to standard therapy1. It is now approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a first-line agent for managing iron overload in both pediatric and adult populations with sickle cell disease or other transfusion-dependent anemias2. Despite its therapeutic efficacy, the clinical use of deferiprone is constrained by a well-documented spectrum of adverse reactions such as agranulocytosis, musculoskeletal disorders like arthropathy, and prevalent gastrointestinal disturbances. Hepatobiliary events, including transient transaminitis, abnormal liver function, and hepatic fibrosis have also been observed3. Additional reported complications comprise zinc deficiency and immunological abnormalities, a notable example being fatal systemic lupus erythematosus4.

While the concentration of deferiprone in biological samples has been determined using a range of techniques-from fundamental methods like spectrofluorimetry5,6,7,8, spectrophotometry9,10, and colorimetry to more sophisticated instrumental analyses such as electrochemical sensing11, LC-MS12, capillary electrophoresis12 and RP–HPLC-UV13,14-the pursuit of a faster, more reliable, and simpler analytical method is ongoing. Among the available options, optical sensing is favored for its operational simplicity but is frequently limited by low sensitivity and selectivity for specific analyte monitoring. To overcome these drawbacks, the integration of nanomaterials as advanced probes has gained significant traction, offering a pathway to improved sensor capabilities15. Nanoparticles are ultrafine particles, > 100 nm, whose unique optical, magnetic, and catalytic properties stem from their high surface area and quantum effects. This makes them powerful tools in various fields of sensing16,17, medicine18,19, and industry20.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are an emerging class of crystalline porous materials, synthesized from metal-containing nodes connected by organic bridging ligands. As a relatively new class of materials, they have attracted significant interest due to their unique structural and chemical properties. These properties include precise pore size, customizable composition and structure, adjustable dimensions, tunable functionality, high loading capacity, and enhanced biocompatibility, making them highly attractive for various applications21. UiO-66, a prominent member of the University of Oslo (UiO) family of MOFs, is a three-dimensional network composed of zirconium (Zr4+) clusters coordinated with terephthalic acid linkers22. A key advantage of UiO-66 over traditional porous materials is its exceptional accessibility for functionalization and post-synthetic modification23. This tunability is facilitated by the high oxophilicity of the Zr4+ metal nodes, which provide up to 12 coordination points for linkers, forming a stable cuboctahedral crystal structure24. The framework exhibits exceptional chemical stability, primarily attributed to the strength of the Zr–O bonds and the high coordination number of Zr4+25. These properties, high specific surface area, remarkable stability, and versatile tenability, underpin the widespread scientific and applicative reputation of UiO-66. Consequently, it has been widely applied in diverse fields including chemical catalysis, photocatalysis, separation, sensing, drug delivery, supercapacitors, and gas storage24.

Herein, UiO-66 MOF was synthesized and used for the development a label-free probe for determination of deferiprone as the model analyte. The measurements were performed in exhaled breath condensate (EBC) as a non-invasive biological sample. EBC is the water vapor contained in breath and very small droplets of lung lining fluid, which are condensed typically by using a cooling or condensing collection device26,27. The optimized and validated probe was subsequently evaluated for its capacity to quantify deferiprone in EBC collected from patients undergoing deferiprone therapy.

Experimental section

Materials

Deferiprone (mass fraction purity of 99.7%) from Arastoo Pharmaceutical Co. (Tehran, Iran), iron (III) chloride hexahydrate (99.0 102.0%), were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). For the synthesis of UiO-66, zirconium chloride (ZrCl4, ≥ 99.5%), terephthalic acid, acetic acid (≥ 99.5%), and N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). For buffer preparation, sodium dihydrogen phosphate dihydrate (NaH2PO4.2H2O) was used and the pH was adjusted to different pHs using sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and hydrochloric acid (HCl), both obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Ultrapure deionized water was obtained from Shahid Ghazi Pharmaceutical Co. (Tabriz, Iran) for dilution.

Instruments

Fluorescence spectra were measured using a Jasco Corp. FP-750 spectrofluorometer (Japan) equipped with a xenon lamp source, with both excitation and emission bandwidths were set to 10 nm and a 1 mL standard quartz cell was used for all measurements. UV-vis absorption spectra of the prepared solutions were recorded on a Shimadzu model UV-1800 spectrophotometer (Japan) using a micro quartz cell. The morphology and size distribution of the synthesized nanoparticles were determined using a Philips CM30 transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Netherlands). The pH adjustments were carried out with a Metrohm 744 digital pH meter (Switzerland). UiO-66 synthesis was conducted in an Initiator 8 EXP oven (Biotage Corp.). The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area was analyzed using the BEL-SORP MINI II (Japan) via the N2 adsorption method.

Synthesis of UiO-66

UiO-66 was synthesized following a previously reported method28. The reagents used were terephthalic acid and ZrCl4. To prepare the nanoparticle, first, 26.6 mg of terephthalic acid was dissolved separately in 5 mL of DMF, and 40.8 mg of ZrCl4 was dissolved in another 5 mL of DMF at room temperature. Then, 0.5 mL of acetic acid was added to the mixture. The resulting solution was transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 120 °C for 24 h without stirring. Crystallization occurred under static conditions. After this treatment, the UiO-66 product was isolated by centrifugation and washed multiple times with DMF and methanol. Finally, the obtained solid was dried overnight under vacuum at 60 °C for further use in experiments.

EBC sampling and preparation

To collect EBC samples, a home-made exhalation collection device based on a cooling trap system was used29. The setup cools the exhaled breath down to − 20 °C and condenses it with admissible efficiency. The EBC samples were collected from healthy and patient volunteers for 10 min. No further processing was necessary before analysis. All sample donors were aware of the purposes of the project and signed a written consent form confirmed by the Ethical Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (IR.TBZMED.REC.1403.279).

The method optimization and validation were performed using deferiprone-spiked EBC samples from healthy individuals. However, the final measurement of deferiprone was conducted in patient samples to evaluate the method’s real-world applicability. This approach was taken because the matrix composition of EBC can differ significantly between healthy and diseased states. To ensure accurate quantification in these authentic patient matrices, the standard addition method was employed for all measurements.

General procedure

Briefly, 10 µL of 0.1 mol L− 1 phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was mixed with 100 µL of EBC in a microtube. To this mixture, 25 µL of the UiO-66 MOF fluorescent probe (1000 mg L− 1) and 5 µL iron III (1000 mg L− 1) were added. Deionized water was then used to bring the total volume to 0.4 mL. Following a 5-minute incubation period at room temperature, the fluorescence intensity was recorded (λex = 285 nm, λem = 410 nm). The response, defined as ΔF (the difference between the intensity in the presence (F) and absence (F0) of deferiprone) was used for quantification. The entire procedure was replicated three times under consistent conditions.

Results and discussions

Characterization of synthesized UiO-66 MOF

TEM was utilized to characterize the particle size and morphology of the synthesized UiO-66 MOF. As can be seen in Fig. 1A, UiO-66 nanoparticles were polyhedral with an average particle size of less than 200 nm. The phase purity and crystallinity of the MOF were confirmed by XRD. The pattern exhibited distinct peaks at 2θ ≈ 7°, 8°and 25.5° corresponding to the (111), (002) and (006) lattice planes of UiO-6630, confirming its successful formation (Fig. 1B). Further evidence for the successful synthesis of UiO-66 was obtained from FT-IR spectroscopy (Fig. 1C). The FT-IR spectrum of pristine UiO-66 showed key bands at 1565 and 1393 cm− 1, which were characteristic of the carboxylate groups in the synthesized framework. This confirms the formation of UiO-66. Another peak at 1600 cm− 1 was associated with the aromatic carbon ring of the organic linker.

The surface area of UiO-66 was also characterized by N₂ adsorption-desorption analysis at 77 K (Fig. 1D). The resulting Type I isotherm, which showed no hysteresis, is indicative of a microporous material. From this data, the BET surface area was calculated to be 1208 m² g⁻¹.

It should be noted that the practical application of the UiO-66 MOF probe is limited by its poor storage stability, a common issue with nanomaterials due to their high surface area and tendency to aggregate. Our stability studies, however, revealed that the synthesized probe maintained a stable signal intensity for approximately 30 days, after which a gradual decrease was observed (Fig. 2).

Deferiprone detection mechanism

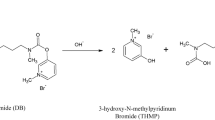

The photoluminescence property of the synthesized UiO-66 was characterized by a maximum emission intensity at 410 nm under 285 nm excitation (Fig. 3A(I)). Introduction of ferric ions into the system resulted in a mild quenching by weakly interacting with the MOF framework (Fig. 3A(II)). Further investigation revealed that deferiprone amplified this quenching effect. When introduced to the MOF-based system, deferiprone induced significant fluorescence quenching proportional to its concentration (0.016–1.0 mg.L− 1) (Fig. 3A(IV)). This significant response contrasted with the weak signal change observed from direct interaction between deferiprone and the UiO-66 (Fig. 3A(III)). It should be noted that zeta potential UiO-66 before (12.9 mV) and after addition of ferric-deferiprone complex (12.6 mV) showed a little changes, indicating no significant electrostatic interaction or close surface binding has occurred. Since Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) requires the donor and acceptor to be within ~ 10 nm, the lack of any driving force for proximity (like charge attraction) or evidence of direct association makes a FRET-based mechanism highly unlikely. In this case, the observed fluorescence quenching/signal change was likely due to other quenching mechanism. The absorption maximum of deferiprone at 279 nm is close to the excitation of UiO-66 (Fig. 3B(I)). This overlap causes a slight decrease. However, in the presence of ferric ions, the absorption maximum shifts to higher wavelengths (283 nm, Fig. 3B(II)), which further increased the spectral overlap and significantly enhanced this quenching effect. This enhanced quenching analogoued to previously reported systems for other pharmaceutical chelators5,31.

The mentioned fluorescence quenching of UiO-66 (excitation λmax = 285 nm, Fig. 3C) upon introduction of the ferric-deferiprone complex (absorption λmax = 283 nm) was predominantly attributable to an inner filter effect (IFE). This fact arise from the significant spectral overlap between the excitation band of probe and the absorption spectrum of the ferric-deferiprone complex. The complex competitively attenuated the photon flux of the incident radiation at 285 nm, thereby reducing the effective excitation intensity incident upon the UiO-66 particles. This attenuation resulted in a corresponding decrease in the population of the MOF’s excited state and a consequent reduction in its emitted fluorescence intensity. A schematic representation of the response of a UiO-66/ferric ion system to deferiprone was given in Scheme 1.

Optimization studies

The main parameters affecting of the reaction between UiO-66/ ferric ion system and deferiprone were optimized to enable its measuring in EBC. Based on preliminary experiments, the fluorescent intensity depended on four factors: pH, UiO-66 MOF and ferric ion concentration, and incubation time. The optimization was performed using a deferiprone concentration of 0.3 mg.L− 1. Selecting a suitable pH could effectively enhance the probe performance. Herein, the effect of pH on fluorescence intensity was investigated across a range of 3.0 to 9.0 (Fig. 4A). The highest change in fluorescence (ΔF) was observed at pH 7.0, which was identified as the optimum condition. This optimum can be attributed to the fact that it was the best pH for the formation of the deferiprone-ferric ion complex32 which act as a key factor for the IFE mechanism.

In the following, different concentrations of UiO-66 MOF in the range of 62.5–250 mg L− 1 were tested to determine the optimal amount of UiO-66 MOF during the process design. As can be seen in Fig. 4B, the analytical response increased with increasing UiO-66 concentration (up to 156.25 mg L− 1) and then decreased due to nanoparticle self-quenching at high concentrations. Effect of ferric ions concentrations on the fluorescence intensity was also studied in the different concentrations from 12.5 to 187.5 mg L− 1. Based on the results (Fig. 4C), the ΔF increased with increasing concentrations of ferric ions and 31.25 mg L− 1 showed proper fluorescence quenching with acceptable precision. A plateau state was observed at higher concentrations due to saturation of binding sites for the IFE mechanism.

The time required for the reaction between deferiprone molecules and the UiO-66 MOF/ferric ion system to reach equilibrium was defined as the incubation time. This parameter was investigated over a range of time intervals, from immediate measurement up to 20 min (Fig. 4D). The fluorescence response of the probe reached its maximum after 5 min, which was consequently selected as the optimal incubation time for all subsequent experiments.

Figures of merit

To evaluate the response of the UiO-66/ferric ion system toward deferiprone, the concentration-dependent behavior of the method was studied under optimal conditions. Increasing level in deferiprone concentration led to a significant decrease in fluorescence intensity of probe at around 410 nm (Fig. 5). Based on the results, there was a respectable linear relationship between the fluorescence intensity and deferiprone concentration in the range of 0.016-1.0 mg.L− 1. The equation of this linear ΔF = 274.57 CDEF +53.122 (R² =0.9918), where CDEF represented the concentration of deferiprone in mg.L− 1, ΔF indicated the difference of the fluorescence intensity in the absence and presence of deferiprone. The limit of detection (LOD) was calculated based on 3Sb/m (Sb: blank’s standard deviation; m: calibration slope). It was found to be 0.005 mg.L− 1.

To evaluate precision, the method was tested with multiple replicates on the same day and over different days. The relative standard deviation (RSD%) for five analyses of a 0.3 mg.L− 1 sample was 4.2% for intra-day and 7.8% for inter-day measurements. Notably, the inter-day RSD was nearly double the intra-day RSD, potentially due to the day-to-day instability of the UiO-66 MOF, such as structural degradation or adsorption of moisture, which could alter its fluorescent properties over time.

Table 1 compared the analytical performance of the proposed method with existing techniques for detecting deferiprone. It should be noted that while several methods such as LC/MS, HPLC-UV, and capillary electrophoresis offer wide linear ranges or low LODs, they often involve complex instrumentation, lengthy sample preparation, and consume the expensive and environmentally hazardous organic solvents throughout the analytical process. Additionally, while electrochemical methods can offer excellent sensitivity, they often suffer from lower reproducibility due to electrode fouling and surface passivation, which limits their reliability for routine analysis. In contrast, spectrofluorimetric methods—particularly those using nanomaterials like carbon dots, MIL-101/agarose, and graphene quantum dots —provide simpler, more adaptable platforms for analysis, and with the current UiO-66/Fe³⁺ system exhibiting a competitive LOD (0.005 mg.L− 1) and a wide linear range (0.016–1.0 mg.L− 1). However, within the category of fluorometric methods, “Off-On” sensing mechanism, as employed in this work, offers superior selectivity over conventional “Turn-Off” approaches (e.g., MIL-101/agarose nanocomposite hydrogel based system6. Furthermore, although Fe- quantum dots based systems5,7 are renowned for their high biocompatibility and aqueous dispersibility, our MOF-based system provides a more structured and porous scaffold. This architecture is crucial for enhancing selectivity, as the uniform pores of UiO-66 can provide size-exclusion effects, potentially blocking larger interferents present in complex biological matrices. Moreover, the well-defined crystalline structure of UiO-66 allows for more precise engineering of the binding sites and a more predictable interaction with the Fe³⁺/deferiprone complex, which likely contributes to the acceptable sensitivity (lower LOD) in this work compared to the quantum dots based probes.

Interference study

The response of UiO-66/ferric ion system toward deferiprone in the presence of some potential co-administered/over-the-counter drugs and some coexisting inorganic ions/organic compounds in EBC was also studied for evaluating the method selectivity. The probe response was recorded at a concentration of 0.3 mg.L− 1 for deferiprone and all interfering substances. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the probe has acceptable selectivity for deferiprone, with no observable interference from the majority of compounds tested. Notable exception was mefenamic acid, which significantly altered the signal, implying that their co-presence could lead to inaccurate deferiprone quantification. It should be noted that mefenamic acid acts as a chelating agent for transition metals such as Cu2+, Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions33. So, for applications where this interference is present, using sample purification or extraction steps is recommended to enhance analytical accuracy.

Real samples analysis

The proposed UiO-66/ferric ion system was utilized to quantify deferiprone in the EBC of six patients receiving this medication. The results were summarized in Table 2. As can be seen, the concentration of deferiprone in real samples was in the range of 0.062–0.118 mg.L− 1. To evaluate the method’s accuracy, a recovery test was performed alongside the deferiprone determination. Recovery percentages ranged from 97.0 to 106.0%, demonstrating the method’s reliability for analyzing real samples. For additional validation, samples 1 and 4 were subjected to HPLC-UV analysis, yielding a deferiprone concentration of 0.0618 ± 0.007 and 0.0812 ± 0.010 mg.L⁻¹. Comparison with the results from the herein validated method (0.062 ± 0.007 and 0.081 ± 0.009 mg.L⁻¹) via a two-tailed paired t-test revealed no statistically significant difference at the 95% confidence level. This agreement supports the promise of the proposed method for accurate measurement of deferiprone in relevant biological matrices.

Conclusion

In the current work, a simple fluorescent probe was designed based on the UiO-66 MOF/ferric ion system for the determination of deferiprone in EBC samples. The increasing levels of deferiprone showed a significant decrease in fluorescent intensity of the proposed probe. The method revealed a linear response toward deferiprone in the range of 0.016-1.0 mg.L− 1 with LOD of 0.005 mg.L− 1 and acceptable selectivity. The validated method was successfully employed for the determination of deferiprone in the EBC samples of patients receiving this medication, with recovery in the range of 97.0% to 106%.

Data availability

Data supporting this study are included within the article.

References

Kwiatkowski, J. L. et al. Deferiprone vs deferoxamine for transfusional iron overload in SCD and other anemias: a randomized, open-label noninferiority study. Blood Adv. 6 (4), 1243–1254 (2022).

Ferriprox® (deferiprone) Tablets. Prescribing Information (United States Food and Drug Administration, 2011).

Gray, J. P. & Ray, S. D. Side effects of metals and metal antagonists. In Side Effects of Drugs Annual 217–225 (Elsevier, 2023).

Barman Balfour, J. A. & Foster, R. H. Deferiprone: a review of its clinical potential in iron overload in β-thalassaemia major and other transfusion-dependent diseases. Drugs 58 (3), 553–578 (1999).

Kaviani, R. et al. Developing an analytical method based on graphene quantum Dots for quantification of deferiprone in plasma. J. Fluoresc. 30 (3), 591–600 (2020).

Moharami, R. et al. Design and development of metal-organic framework-based nanocomposite hydrogels for quantification of deferiprone in exhaled breath condensate. BMC Chem. 18 (1), 176 (2024).

Sefid-Sefidehkhan, Y. et al. Utilizing Fe (III)-doped carbon quantum Dots as a nanoprobe for deferiprone determination in exhaled breath condensate. Chem. Pap. 77 (3), 1445–1453 (2022).

Mohamadian, E. et al. Analysis of deferiprone in exhaled breath condensate using silver nanoparticle-enhanced terbium fluorescence. Anal. Methods. 9 (38), 5640–5645 (2017).

Padma, A. D. K. T., Pallavi, A., Snehith, B. & Kumar, M. P. A validated Uv spectroscopic assay method development for the Estimation of deferiprone in bulk and its formulation world. J. Pharm. Res. 8, 1 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. A ratiometric fluorometric and colorimetric probe for the beta-thalassemia drug deferiprone based on the use of gold nanoclusters and carbon Dots. Mikrochim Acta. 185 (9), 442 (2018).

Łuczak, T. Development of a new voltammetric sensor by using a hybrid material consisting of gold nanoparticles and S-organic compounds for detection of deferiprone-anti-thalassemia and anti HIV-1 drug. Measurement 126, 242–251 (2018).

Asmari, M. et al. Analytical approaches for the determination of deferiprone and its iron (III) complex: investigation of binding affinity based on liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-ESI/MS) and capillary electrophoresis-frontal analysis (CE/FA). Microchem. J. 154, 1 (2020).

Sachin, N. & Kothawade, V. V. P. Development and validation of an rp-hplc method for deferiprone Estimation in pharmaceutical dosage form. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 16, 1 (2023).

Fares, M. Y. et al. Quality by design approach for green HPLC method development for simultaneous analysis of two thalassemia drugs in biological fluid with Pharmacokinetic study. RSC Adv. 12 (22), 13896–13916 (2022).

Khalid, K. et al. Advanced in developmental organic and inorganic nanomaterial: a review. Bioengineered 11 (1), 328–355 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Molybdenum disulfide quantum Dots for rapid fluorescence detection of glutathione and ascorbic acid. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 326, 125189 (2025).

Zhong, Y. et al. Rapid and ratiometric fluorescent detection of hypochlorite by glutathione functionalized molybdenum disulfide quantum Dots. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 295, 122649 (2023).

Zhong, Y. et al. Glutathione-responsive oxidative stress nanoamplifier boosts sonodynamic/chemodynamic synergistic antibacterial therapy. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1, 139393 (2025).

Shao, K. et al. MoS2 QDs-decorated mesoporous polydopamine nanoparticle as a GSH responsive peroxidase-like nanozyme for effective antibacterial therapy. Chem. Eng. J. 165645 (2025).

Stark, W. J. et al. Industrial applications of nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44 (16), 5793–5805 (2015).

Zou, D. & Liu, D. Understanding the modifications and applications of highly stable porous frameworks via UiO-66. Mater. Today Chem. 12, 139–165 (2019).

Chen, L. et al. University of Oslo-66: A versatile Zr-Based MOF for water purification through adsorption and photocatalysis. Processes 13 (4), 1 (2025).

Rego, R. M., Kurkuri, M. D. & Kigga, M. Corrigendum to ‘A comprehensive review on water remediation using UiO-66 MOFs and their derivatives’. Chemosphere 302, 134845 (2023).

Kadhom, M. et al. A review on UiO-66 applications in membrane-based water treatment processes. J. Water Process. Eng. 51, 103402 (2023).

Wu, M. et al. Research progress of UiO-66-based electrochemical biosensors. Front. Chem. 10, 842894 (2022).

Rahimpour, E. et al. Non-volatile compounds in exhaled breath condensate: review of methodological aspects. Anal. Bioanal Chem. 410 (25), 6411–6440 (2018).

Ghanem, E. Nanosensors for exhaled breath condensate: explored models, analytes, and prospects. J. Nanotheranostics. 6 (2), 1 (2025).

Karimzadeh, Z. et al. A sensitive determination of morphine in plasma using AuNPs@ UiO-66/PVA hydrogel as an advanced optical scaffold. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1227, 340252 (2022).

Jouyban, A. et al. Breath sampling setup. Iran. Patent. 81363, 1 (2013).

Wu, R. et al. Highly dispersed Au nanoparticles immobilized on Zr-based metal–organic frameworks as heterostructured catalyst for CO oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A. 1 (45), 14294–14299 (2013).

Durán, G. M. et al. Analysis of penicillamine using Cu-modified graphene quantum Dots synthesized from uric acid as single precursor. J. Pharm. Anal. 7 (5), 324–331 (2017).

Pragourpun, K. Development of Sequential Injection Analysis for Spectrophotometric Determination of Iron Using Deferiprone as Reagent (Mahasarakham University, 2012).

Topacli, A. & Ide, S. Molecular structures of metal complexes with mefenamic acid. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 21 (5), 975–982 (1999).

Acknowledgements

We would like to appreciate of the cooperation of Clinical Research Development Unit, Imam Reza General Hospital, Tabriz, Iran in conducting this research.

Funding

This work was supported by Research Affairs of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, under grant number 74398.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nima Sheikh Abdollahzadeh Mamaghani: Investigation, Acquisition of data, Drafting the article, Zahra Karimzadeh : Acquisition of data, Drafting the article, Maryam Khoubnasabjafari: Analysis and interpretation of data, Resources, Vahid Jouyban-Gharamaleki : Analysis and interpretation of data, Resources, Elaheh Rahimpour : Supervision, Final approval of the version to be submitted, Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. Abolghasem Jouyban ; Supervision, The conception and design of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All the methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations according to the Declaration of Helsinki 1975, as revised in 2008. The method and the study were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. All sample donors or participants filled out and signed the informed consent form for the project with ethical code IR.TBZMED.REC.1403.279 confirmed by the ethics committee at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheikh Abdollahzadeh Mamaghani, N., Karimzadeh, Z., Khoubnasabjafari, M. et al. A label-free fluorescent probe for deferiprone quantification in exhaled breath condensate utilizing UiO-66 MOF/ferric ions system. Sci Rep 16, 3512 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33395-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33395-8