Abstract

Resonant-type piezoelectric vibration energy harvesters (pVEHs) can achieve high energy conversion efficiency and output power density by using resonance phenomena with external vibrations at constant frequencies. However, this approach is less effective for the random vibrations commonly encountered in real-world environments, thus limiting its practical applications. This study employs impulsive forces and a two-degree-of-freedom system with a dynamic magnifier (DM) to enhance the output power of a nonresonant microelectromechanical systems-based pVEH (MEMS-pVEH). Lead-free BiFeO3 (BFO) was selected as the piezoelectric thin film due to its considerable figure of merit in energy conversion applications. We investigated the electromechanical properties of the BFO-based MEMS-pVEH using DM under various impulsive force durations. The results revealed that incorporating a DM increased the output energy of the MEMS-pVEH from 0.17 nJ/G2 to 3.97 nJ/G2 (where G represents gravitational acceleration) for a 23.8-fold enhancement. The findings demonstrate that the output energy of conventional MEMS-pVEH structures using lead-free piezoelectric BFO film can be significantly amplified with the integration of a simple DM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of the Internet of Things (IoT) has improved services in various sectors, including healthcare, agriculture, and smart cities1,2. However, a key challenge is maintaining a reliable power supply for IoT devices, particularly those deployed in remote or inaccessible locations. Traditional batteries struggle to meet long-term IoT demands due to their limited lifespan and maintenance requirements. However, recent advances in low-power sensors and wireless communication modules have increased the viability of harvesting ambient energy for powering IoT devices. In particular, these technologies convert ambient energy from environmental sources, such as thermal gradients, solar radiation, and mechanical vibrations, into electrical power3,4,5.

To date, harvesting vibration energy has emerged as a particularly promising method among the various energy harvesting approaches that have been introduced. This method converts mechanical vibrations, one of the most abundant energy sources in the environment (including those generated by human activities), into electrical energy. Several methods exist for converting mechanical energy into electrical energy, including the electrostatic effect, triboelectric effect, and electromagnetic induction. However, the piezoelectric effect is distinguished by its linearity and simple conversion principle6. With micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS), piezoelectric vibration energy harvesters (pVEHs) can be miniaturized for an improved mechanical quality factor (\({Q}_{m}\)), thus enhancing their output power. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that MEMS-pVEHs using Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 (PZT) and BiFeO3 (BFO) films exhibit output power levels exceeding 90% and 80%, respectively, of the theoretical maximum under resonant conditions7,8.

Conventional resonant-type MEMS-pVEHs typically have high resonance frequencies and narrow frequency bandwidths, resulting in challenges in terms of harvesting energy from the low-frequency broadband and random vibrations most commonly found in the environment9,10,11. Various structural and methodological approaches have been developed to address this problem. A common strategy is to expand the operational frequency bandwidth of the harvester by introducing mechanical nonlinearities, such as in multistable12,13,14,15 and multimodal models16,17,18,19. However, the frequency bandwidth of pVEHs in the MEMS scale remains relatively high compared to typical environmental vibrations, which are generally below 100 Hz20. Moreover, broadening the frequency bandwidth leads to a lower \({Q}_{m}\), which in turn, decreases the output power of the harvester.

Another approach focuses on tuning the harvester’s natural frequency to match the external vibration frequency. This can be achieved with autonomous resonance-tuning techniques, such as using a movable proof mass, applying magnetic forces to adjust the MEMS-pVEH stiffness or employing electrical circuits to modify the resonance frequency21,22,23. While doing so can improve the energy conversion efficiency of the harvester, they are most effective with continuous vibrations, such as those from machinery, where external vibrations persist long enough to enable proper tuning. By contrast, this approach has limited effectiveness with nonstationary vibrations, such as those arising from human motion, which are the predominant vibration sources in many practical scenarios. Frequency upconversion transforms low-frequency vibrations into higher frequency via contact and noncontact mechanical forces24,25,26,27. This method effectively converts low-frequency periodic excitations and time-varying excitations (e.g., human movements) into higher-frequency vibrations that match the operating characteristics of MEMS-pVEHs, which typically have high resonance frequencies and high \({Q}_{m}\). However, to date, no study has addressed the challenge of efficiently harvesting energy from short-duration impulsive events.

To address this gap, in this study, we use impulsive forces as the excitation source, resulting in MEMS-pVEHs whose output energy exhibits minimal dependence on the harvester’s resonant frequency when excited by an impulsive force. In addition, the ratio of the output to the theoretical maximum exceeds 50% as the duration of the impulsive force decreases28. Impulsive inputs inherently contain broadband spectral components, thus enabling the efficient excitation of high \({Q}_{m}\) MEMS-pVEH without requiring bandwidth broadening or resonance tuning, as broadband frequency content naturally overlaps with the device’s resonance. Hence, impulsive forces are particularly suitable for harvesting nonstationary vibrations using high \({Q}_{m}\) MEMS-pVEHs that are not covered by conventional broadbanding or resonance tuning techniques.

Furthermore, we considered a two-degree-of-freedom system (2DOFpVEH) using a dynamic magnifier (DM)29,30,31. A DM serves as an amplitude amplifier and a frequency upconversion structure, thereby enabling MEMS-pVEHs to resonate with the vibration of the DM after being excited by the external impulsive force. This approach can further enhance the output power of an MEMS-pVEH from impulsive force. Additionally, in the proposed system, the device’s electronic components (e.g., capacitors, resistors, and sensors) can be integrated into the DM as part of the proof mass. This not only maximizes space efficiency but also enhances mechanical amplification by increasing the proof mass of the DM, thus improving the output power at the same time. This combined impulsive force and DM-based approach represents a fundamentally different strategy from previously reported strategies, thereby enabling high-efficiency energy extraction from transient, nonstationary vibration sources using a high \({Q}_{m}\) MEMS-pVEH.

Among piezoelectric materials, PZT is the most widely studied thin-film material due to its high piezoelectric coefficient, which makes it an attractive option for piezoelectric MEMS applications, such as actuators. In a previous work, we reported that the output energy of a PZT-based MEMS-pVEH can be enhanced to 19 nJ/G2 (where G is gravitational acceleration, G = 9.8 m/s2) by using a 2DOF system, which is 90 times higher than that of the conventional 1DOF-MEMS-pVEH32. However, PZT-based piezoelectric materials exhibit a high dielectric constant33,34,35. This poses a challenge in improving the figure of merit (FOM) for MEMS-pVEHs, because the FOM is inversely proportional to the dielectric constant, making PZT less suitable for practical energy harvesting applications36. Notably, within the same cantilever structure of the MEMS-pVEH, we observed that the \({Q}_{m}\) with BFO film is two times higher than that with PZT, which makes BFO thin film a highly attractive candidate for harvester applications7,8. Therefore, in the present study, we propose the use of BFO thin films, which are a promising candidate for MEMS-pVEH applications, due to their large spontaneous polarization (~ 100 μC/cm2) and low dielectric constant (~ 100), both contributing to a high electromechanical coupling factor and significant output energy37.

In this study, we designed and optimized the DM for a 2DOF system through theoretical and experimental validation to maximize the output energy from impulsive forces. Our results demonstrate that the implementation of impulsive force and DM provides an effective strategy for harvesting nonstationary vibration sources of the high \({Q}_{m}\) MEMS-pVEHs. This approach highlights the potential of BFO-based MEMS-pVEHs as eco-friendly, self-powered energy sources for portable, wearable, and implantable electronic devices.

Numerical study

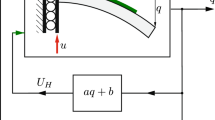

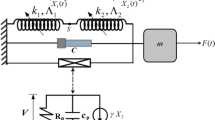

To design and optimize the 2DOF-pVEH system for harvesting impulsive forces, the dependence of electromechanical properties on the structural properties of DMs and MEMS-pVEHs was investigated in a theoretical simulation. Figure 1 illustrates the dynamic model and schematic of the 2DOF-pVEH, in which the MEMS-pVEH is placed above the DM. This model was used for calculations38.

The governing equations for the mechanical domain of the 2DOF-pVEH are as follows:

where \(D\) is the mechanical damping coefficient equivalent to \(m\omega /Q\), and \(\omega\) is the natural angular frequency, calculated as \((k/m)\) 1/2, where \(k\) is the spring constant and \(m\) is the mass. The equation for the electrical domain is given by:

where \(\theta\) is the electromechanical coupling factor. This is determined by the formula \(\theta =K\sqrt{{{C}_{p}k}_{pVEH}}\), where \({C}_{p}\) is the capacitance of the piezoelectric film and \({R}_{l}\) is the load resistance. The calculation parameters for the investigation are summarized in Table 1, in which most parameters are derived from the characteristics of the fabricated MEMS-pVEH with the BFO film.

The theoretically simulated dynamic behaviors of the 2DOF-pVEH are illustrated in Fig. 2. The duration of the impulsive force is set to 2 ms (Fig. 2a), while the output waveforms of the 2DOF-pVEH (where \({Q}_{DM}\) is 20 and \({f}_{DM}\) ranges from 143, 153, and 173 Hz) are shown in Figs. 2b–d. When an impulsive force is applied, the DM first responds with a damped harmonic motion, and its vibration subsequently excites the MEMS-pVEH. As illustrated in Figs. 2b–d, the output voltage gradually increases after the impulsive force as vibration energy is transferred to the DM and then to the MEMS-pVEH. Then, the output voltage gradually decreases as the vibration energy is transferred back from the MEMS-pVEH to the DM.

The results reveal that the output power significantly increases when \({f}_{DM}\) approaches \({f}_{pVEH}\), as resonance occurs between the DM and the MEMS-pVEH. The output waveforms under different \({f}_{DM}\) when \({Q}_{DM}\) is set to 200 are illustrated in Figs. 2e–g. The amplitude of the output voltage does not significantly change at \({f}_{DM}\) values of 143 and 173 Hz (off-resonant frequencies) compared to the case with low \({Q}_{DM}\). However, a substantial increase in output voltage occurs under resonance conditions at \({f}_{DM}\) = 153 Hz. At high \({Q}_{DM}\) values, the output voltage exhibits a beat phenomenon. Although the natural frequencies of the DM and MEMS-pVEH are matched, the coupling oscillation effect causes their resonance frequencies to shift slightly in opposite directions, in which one shifts to a lower frequency, while the other shifts to a higher frequency. This discrepancy in frequencies between \({f}_{DM}\) and \({f}_{pVEH}\) leads to the observed beat phenomenon in the coupled 2DOF-pVEH system.

In addition, the duration of the beat in the output voltage does not correlate with \({Q}_{DM}\); instead, it is inversely proportional to \(|{f}_{DM}-{f}_{pVEH}|\), as illustrated in Fig. 3a. The beat frequency ranges from 2.5 Hz to 20 Hz, which aligns with the frequency range associated with human motion and most low-frequency vibrations in the environment. The output power generated during the initial beat is illustrated in Fig. 3b, in which the output power is shown to significantly increase as \(|{f}_{DM}-{f}_{pVEH}|\) approaches zero. This finding suggests that the output energy of the 2DOF-pVEH can be maximized by increasing \({Q}_{DM}\) and tuning \({f}_{DM}\) close to \({f}_{pVEH}\).

The output energy produced by an impulsive force was calculated when \({f}_{DM}={f}_{pVEH}=153 \text{Hz}\) and then plotted as a function of \({Q}_{DM}\) and \({Q}_{pVEH}\) in Fig. 3c. The output energy is determined by integrating the output voltage over 2 s from the moment the impulsive force is applied and continues until the output voltage falls below 0.1% of the maximum output voltage. This phenomenon is expressed in the following equation:

The results demonstrate that the output energy increases with an increase in \({Q}_{DM}\), reaching a saturation point for fixed \({Q}_{pVEH}\). Hence, the output energy of the 2DOF-pVEH from an impulsive force can be enhanced by increasing the quality factor of the MEMS-pVEH and the DM. Specifically, for a \({Q}_{pVEH}\) of 700, the \({Q}_{DM}\) must be greater than 400 to achieve 30 nJ of energy, which is 1000 times greater than that of the 1DOF-pVEH (0.03 nJ).

Experimental results and discussion

Characterisation of MEMS-pVEH

To fabricate MEMS-pVEH, a (100)-oriented BFO film was deposited on a silicon-on-insulator (SOI) substrate using the RF magnetron sputtering method39. Then, the cantilever structure was fabricated using a conventional MEMS process; the details of the procedure are described elsewhere8. The MEMS-pVEH cantilever has a width of 1000 μm, a length of 6000 μm, and a thickness of 20 μm, incorporating a 450 nm-thick BFO film. The weight of the silicon-proof mass is approximately 3.0 mg (Fig. 4a).

(a) Photograph of the MEMS-pVEH. (b) Output voltage as a function of vibration frequency under the short, open-circuit condition. (c) Output voltage as a function of vibration frequency under inputs of 0.02, 0.05, 0.07, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.7 m/s2. (d) Output power dependence of the input vibration amplitude.

The frequency dependence of the output voltage was measured by applying sinusoidal acceleration with an amplitude of 0.1 m/s2. The response output voltage under short- and open-circuit conditions, using 330 Ω and 10 MΩ resistors, respectively, is shown in Fig. 4b. As can be seen, the resonance frequency shifts to a higher value under open-circuit conditions due to the increased stiffness of the piezoelectric material40. The generalized piezoelectric coupling factor \({K}^{2}\) is determined using the following Eq. 39:

where \(\omega\) is the angular frequency determined by \(2\pi f\), with \({f}_{0}\) and \({f}_{1}\) representing the resonance frequencies of the MEMS-pVEH under open- and short-circuit conditions, respectively. With the resonance frequencies presented in Fig. 4b, the \({K}^{2}\) value of the sample was calculated to be 0.1%. Additionally, \({Q}_{m}\) was determined to be 766 using the half-bandwidth method applied to the short-circuit resonance frequency curve. Consequently, the product \({K}^{2}Q\) of the sample is 0.76, implying that we expected the output of the MEMS-pVEH to be 80% of its theoretical maximum41.

Next, the output characteristics of the MEMS-pVEH under various vibration amplitudes were investigated. An optimum (impedance-matched) load resistance of 100 kΩ was used for output characterization. The resulting resonance curves under impedance-matching conditions with input vibrations of 0.02, 0.05, 0.07, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.7 m/s2 (RMS) are shown in Fig. 4c. As can be seen, symmetric curves appear up to 0.4 m/s2, indicating linear electromechanical properties. Conversely, at higher input accelerations of 0.6 m/s2 and 0.7 m/s2, the curves tilt slightly toward a higher frequency, indicating hardening nonlinear effects in the MEMS-pVEH. The output power dependence on the input vibration amplitude is shown in Fig. 4d. The output power increased linearly with the square of the vibration amplitude, thus demonstrating overall good linearity.

Fabrication and characterization of 2DOF-pVEH

Based on the theoretical optimization results, the DM was designed to have a vibration mode perpendicular to the MEMS-pVEH with a resonance frequency matching that of the MEMS-pVEH. The dimensions of the DM were determined using finite element analysis (harmonic analysis with parametric sweeps) via FEMtet (version 2024.02, Murata Software Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; https://www.muratasoftware.com/en/). To achieve high \({{\varvec{Q}}}_{{\varvec{D}}{\varvec{M}}}\), the DM was designed without any joint components and then fabricated from a stainless-steel plate with low internal friction to minimize energy losses. With fixed boundary conditions at the bottom pads, we performed parametric sweeps of the length, width, and thickness, extracting the first bending mode frequency for each configuration (Figure S1). We also targeted \({{\varvec{f}}}_{{\varvec{D}}{\varvec{M}}}\) ≈ 153 Hz (matching \({{\varvec{f}}}_{{\varvec{p}}{\varvec{V}}{\varvec{E}}{\varvec{H}}}\)). Then, the U-shaped DM was fabricated by bending a stainless-steel plate with a curve radius of 5 mm. The DM had the following dimensions: thickness of 0.5 mm, width of 10 mm, and length of 12 mm. After placing the MEMS-pVEH on the DM, the electromechanical properties of the 2DOF-pVEH were characterized under sinusoidal conditions. The resulting resonance curves of the 2DOF-pVEH are shown in Fig. 5. The resonance frequency of the DM was found to be 158 Hz using laser displacement measurement, and \({{\varvec{Q}}}_{{\varvec{D}}{\varvec{M}}}\) was calculated as 405. Furthermore, the MEMS-pVEH exhibits a resonance frequency of 153.5 Hz, resulting in a \(|{{\varvec{f}}}_{{\varvec{D}}{\varvec{M}}}-{{\varvec{f}}}_{{\varvec{p}}{\varvec{V}}{\varvec{E}}{\varvec{H}}}|\) of 4.5 Hz.

As shown in Fig. 5, under the same sinusoidal vibration, the 2DOF configuration produces a 10.7-fold increase in voltage compared with the 1DOF MEMS-pVEH, corresponding to a 114-fold enhancement in output power, while maintaining a narrow half-power bandwidth of approximately 0.3 Hz. Nevertheless, the theoretical results showed that it is critical to minimize \(|{{\varvec{f}}}_{{\varvec{D}}{\varvec{M}}}-{{\varvec{f}}}_{{\varvec{p}}{\varvec{V}}{\varvec{E}}{\varvec{H}}}|\) to enhance the output energy of the harvester for impulsive force. To test this prediction, we attempted frequency tuning by adding 2 g of mass to the tip of the DM. However, this intervention caused an unexpected and drastic \({{\varvec{Q}}}_{{\varvec{D}}{\varvec{M}}}\) reduction from 405 to approximately 26, as evidenced by the comparison of experimental waveforms with theoretical predictions (Figures S2 and S3 in Supporting Information). This severe degradation suggests that the added mass may have excited secondary vibrational modes or introduced additional damping mechanisms that are not included in the simple lumped-parameter model.

Electromechanical properties of 2DOF-pVEH under impulsive force

The electromechanical properties of the 2DOF-pVEH were also investigated under impulsive forces with durations ranging from 2 to 6 ms. Figure 6 illustrates an example of the experimental results for an input impulsive force with a duration of 2 ms, along with the corresponding output voltage waveforms of the 2DOF-pVEH before and after frequency tuning (Figures 6a, b, d, and e). The output voltage waveforms of the 1DOF MEMS-pVEH are presented in Figure 6c.

As shown in the figure, in the conventional MEMS-pVEH, the output voltage rises promptly to its maximum value and gradually decays, thus exhibiting simple harmonic oscillation. In contrast, the 2DOF-pVEH exhibited coupled oscillation resulting from the interaction between the MEMS-pVEH and the DM. In particular, the output waveform of the 2DOF-pVEH displayed clear beat oscillation, which can be attributed to the superposition of two resonance modes (\({f}_{DM}\),\({f}_{pVEH}\)) simultaneously excited by the impulsive force. The beat duration of the output voltage was approximately 0.2 s, consistent with the theoretical calculations.

The normalized output energy as a function of impulse duration is depicted in Fig. 7. The maximum output energy \({E}_{max}\) of the conventional BFO-based MEMS-pVEH was 0.17 nJ/G2. With a high \({Q}_{DM}\), \({E}_{max}\) increased to 3.97 nJ/G2, corresponding to a 23.8-fold enhancement. The output energy demonstrated minimal dependence on impulse duration, regardless of the high-quality factor of both the MEMS-pVEH and the additional DM. Furthermore, the impulse duration at which the maximum output energy occurs is indirectly influenced by the resonance frequency of the MEMS-pVEH and the DM, as reflected in the broad curve shape.

A comparison with previously reported 2DOF systems is summarized in Table 2. Most prior studies enhanced performance by broadening the operational bandwidth using auxiliary components, such as additional springs, magnets, or mechanical stoppers. These designs achieved bandwidths of 3–7 Hz but relied on continuous and low-frequency periodic vibrations to function effectively. In contrast, our design prioritizes achieving a high \({Q}_{DM}\) rather than widening the bandwidth. This fundamental difference in design philosophy yields significantly higher power enhancement (114 × for untuned, 12.7 × for tuned (Figure S2)) under sinusoidal vibration but narrower bandwidth (0.3 Hz vs. 3–7 Hz ). However, this is not a limitation for impulsive forces containing broadband frequency content. Our theoretical analysis (Fig. 3) demonstrates that with identical DM properties, a 2 ms impulsive input can increase the harvested energy from 0.03 nJ (1DOF) to 30 nJ (2DOF), corresponding to a theoretical enhancement of approximately 1000-fold. Although the experimental enhancement observed in this work is just 23.8-fold, it is still significantly higher than that reported in previous 2DOF harvesters. Therefore, our results confirm that a high-Q narrow-bandwidth design is advantageous for harvesting impulsive forces, as nonstationary and intermittent vibration sources are common in wearable and human motion applications.

From a material perspective, the BFO-based 2DOF-pVEH proposed in this study is still lower than the PZT-based approach reported previously32, which is due to the much lower electromechanical coupling factor in the current study (PZT: \({K}^{2}=0.6\%\) vs. BFO: \({K}^{2}=0.1\%\)). Furthermore, our previous work established that MEMS-pVEHs require \({K}^{2}Q\ge\) 10 to achieve over 90% of the theoretical maximum output. Hence, the \({K}^{2}Q\) values are 1.9 for PZT and only 0.8 for BFO, indicating that both materials still fall short in terms of reaching the target of \({K}^{2}Q\ge\) 10. Despite its lower coupling factor, BFO offers a notable advantage wherein its mechanical quality factor is approximately twice that of PZT in the same cantilever structure7,8. This makes BFO a highly attractive candidate for impulsive-force and frequency-upconversion harvesting schemes in which high Q is essential for maximizing output energy. Looking forward, further improvements in BFO thin films could substantially enhance the performance of 2DOF-pVEHs under impulsive force. Approaches such as increasing the piezoelectric coefficient \({e}_{31,f}\) through epitaxial orientation control, strain engineering, or targeted doping, can raise \({K}^{2}\) and enable BFO to approach the \({K}^{2}Q\ge\) 10 while maintaining the environmental benefits of a lead-free material system.

Overall, the present study demonstrates that combining a high-Q BFO film with a DM is a promising strategy for harvesting energy under impulsive excitation. This work also provides a promising framework for the future development of high-performance, lead-free MEMS energy harvesters.

Conclusion

This study presented the electromechanical properties of a BFO-based MEMS-pVEH under nonresonant conditions, specifically with impulsive forces. The MEMS-pVEH with a 450 nm-thick BFO film grown on Si substrates demonstrated good linearity and exhibited a resonance frequency of 153.5 Hz. In the 2DOF-pVEH, the DM accumulated mechanical energy and amplified the vibration amplitude of the MEMS-pVEH. These results indicate that maximizing the output power of the 2DOF-pVEH requires maintaining a high \({{\varvec{Q}}}_{{\varvec{D}}{\varvec{M}}}\) and ensuring that its resonance frequency is aligned with that of the MEMS-pVEH.

Under impulsive forces, beat oscillations in the output voltage response were observed in the theoretical and experimental analyses. These oscillations were attributed to the coupling effect between the MEMS-pVEH and the DM. However, this coupling diminished as the \({Q}_{DM}\) decreased, thus increasing the damping of the DM and ultimately limiting the efficient energy transfer from the input impulsive force to the MEMS-pVEH. Notably, the output energy of the BFO-based MEMS-pVEH can be enhanced 23.8-fold by incorporating a simple, high \({Q}_{DM}\) dynamic magnifier.

Experiment methods

The electromechanical properties of the MEMS-pVEH were characterized by applying sinusoidal vibrations using a shaker (IMV, PET-1). The applied acceleration was measured with an accelerometer (710-D, EMIC Corp.), and the output voltage across the load resistance was recorded using a lock-in amplifier (LI5640, NF Corp.). The displacement of the oscillator was also measured by a laser displacement sensor (LKH020, Keyence) connected to the lock-in amplifier.

An impulsive force was applied in a manner perpendicular to the harvester using a vibration generator. This was accomplished using a single unipolar sinusoidal signal produced by a function generator (Hewlett Packard 3120A) and amplified by a bipolar amplifier (KEPCO). Then, the waveforms of the input impulsive force and the output voltage of the MEMS-pVEH were simultaneously measured using an oscilloscope (DS5624A, IWATSU), after which the output voltage was measured across an impedance-matched load resistance of 100 kΩ. Furthermore, the input impulsive forces were controlled to obtain an amplitude of approximately 1 G.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ystgaard, K. F. et al. Review of the theory, principles, and design requirements of human-centric internet of things (IoT). J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 14, 2827–2859 (2023).

Ali, A., Iqbal, S. & Chen, X. Recent advances in piezoelectric wearable energy harvesting based on human motion: Materials, design, and applications. Energy Strateg. Rev. 53, 101422 (2024).

Calautit, K., Nasir, D. S. N. M. & Hughes, B. R. Low power energy harvesting systems: State of the art and future challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 147, 111230 (2021).

Xu, C., Song, Y., Han, M. & Zhang, H. Portable and wearable self-powered systems based on emerging energy harvesting technology. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 7, 25 (2021).

Sanislav, T., Mois, G. D., Zeadally, S. & Folea, S. C. Energy harvesting techniques for Internet of Things (IoT). IEEE Access 9, 39530–39549 (2021).

Liang, H., Hao, G. & Olszewski, O. Z. A review on vibration-based piezoelectric energy harvesting from the aspect of compliant mechanisms. Sensors Actuators A Phys. 331, 112743 (2021).

Aramaki, M. et al. Investigation of mechanical nonlinear effect in piezoelectric MEMS vibration energy harvesters. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 57, 11UD03 (2018).

Aramaki, M., Yoshimura, T., Murakami, S., Satoh, K. & Fujimura, N. Demonstration of high-performance piezoelectric MEMS vibration energy harvester using BiFeO3 film with improved electromechanical coupling factor. Sensors Actuators A Phys. 291, 167–173 (2019).

Feng, H. et al. Multimodal MEMS vibration energy harvester with cascaded flexible and silicon beams for ultralow frequency response. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 9, 33 (2023).

Hossain, M. I., Zahid, M. S., Chowdhury, M. A., Maruf Hossain, M. M. & Hossain, N. MEMS-based energy harvesting devices for low-power applications – a review. Res. Eng. 19, 101264 (2023).

Hao, Y. & Helo, P. The role of wearable devices in meeting the needs of cloud manufacturing: A case study. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 45, 168–179 (2017).

Deng, H. et al. Poly-stable energy harvesting based on synergetic multistable vibration. Commun. Phys. 2, 21 (2019).

Fu, H., Jiang, J., Hu, S., Rao, J. & Theodossiades, S. A multi-stable ultra-low frequency energy harvester using a nonlinear pendulum and piezoelectric transduction for self-powered sensing. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 189, 110034 (2023).

Qian, F., Hajj, M. R. & Zuo, L. Bio-inspired bi-stable piezoelectric harvester for broadband vibration energy harvesting. Energy Convers. Manag. 222, 113174 (2020).

Yan, Y. et al. Design and investigation of a quad-stable piezoelectric vibration energy harvester by using geometric nonlinearity of springs. J. Sound Vib. 547, 117484 (2023).

Zhang, B. et al. Modeling and analysis of a three-degree-of-freedom piezoelectric vibration energy harvester for broadening bandwidth. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 176, 109169 (2022).

Noh, J., Nguyen, M. S., Kim, P. & Yoon, Y.-J. Harmonic balance analysis of magnetically coupled two-degree-of-freedom bistable energy harvesters. Sci. Rep. 12, 6221 (2022).

Elgamal, M. A., Elgamal, H. & Kouritem, S. A. Optimized multi-frequency nonlinear broadband piezoelectric energy harvester designs. Sci. Rep. 14, 11401 (2024).

Fan, Y., Zhang, Y., Niu, M. Q. & Chen, L. Q. An internal resonance piezoelectric energy harvester based on geometrical nonlinearities. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 211, 111176 (2024).

Kim, S.-G., Priya, S. & Kanno, I. Piezoelectric MEMS for energy harvesting. MRS Bull. 37, 1039–1050 (2012).

Ghanbari, M., Rezazadeh, G. & Moloudpour-Tolkani, V. A wide-bandwidth MEMS energy harvester based on a novel voltage-sliding stiffness tunability. Appl. Math. Model. 125, 16–34 (2024).

Lee, D. et al. Autonomous resonance-tuning mechanism for environmental adaptive energy harvesting. Adv. Sci. 10, 2205179 (2023).

Shin, Y.-H. et al. Automatic resonance tuning mechanism for ultra-wide bandwidth mechanical energy harvesting. Nano Energy 77, 104986 (2020).

Aceti, P. et al. Optimization of an impact-based frequency upconverted piezoelectric vibration energy harvester for wearable devices. Sensors 23, 1391 (2023).

Nastro, A. et al. Wearable ball-impact piezoelectric multi-converters for low-frequency energy harvesting from human motion. Sensors 22, 772 (2022).

Abedini, A., Onsorynezhad, S. & Wang, F. Periodic solutions of an impact-driven frequency up-conversion piezoelectric harvester. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 29, 1–16 (2019).

Luo, A. et al. Vibration energy harvester with double frequency-up conversion mechanism for self-powered sensing system in smart city. Nano Energy 105, 108030 (2023).

Aphayvong, S., Yoshimura, T., Murakami, S., Kanda, K. & Fujimura, N. Investigation of efficient piezoelectric energy harvesting from impulsive force. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 59, SPPD4 (2020).

Aldraihem, O. & Baz, A. Energy harvester with a dynamic magnifier. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 22, 521–530 (2011).

Arafa, M., Akl, W., Aladwani, A., Aldraihem, O. & Baz, A. Experimental implementation of a cantilevered piezoelectric energy harvester with a dynamic magnifier. Proc. SPIE 7977, 79770Q (2011).

Tang, L. & Wang, J. Modeling and analysis of cantilever piezoelectric energy harvester with a new-type dynamic magnifier. Acta Mech. 229, 4643–4662 (2018).

Aphayvong, S., Murakami, S., Kanda, K., Fujimura, N. & Yoshimura, T. Enhanced performance on piezoelectric MEMS vibration energy harvester by dynamic magnifier under impulsive force. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 172902 (2022).

Yeager, C. B., Ehara, Y., Oshima, N., Funakubo, H. & Trolier-McKinstry, S. Dependence of e31 f on polar axis texture for tetragonal Pb (Zrx,Ti1−x)O3 thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 116, 104907 (2014).

Wan, X. et al. Enhanced piezoelectric properties of (110)-oriented PbZr1−xTixO3 epitaxial thin films on silicon substrates at shifted morphotropic phase boundary. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 092902 (2014).

Kanno, I. Piezoelectric MEMS: Ferroelectric thin films for MEMS applications. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 57, 040101 (2018).

Dubois, M.-A. & Muralt, P. Measurement of the effective transverse piezoelectric coefficient e31,f of AlN and Pb(Zrx,Ti1-x)O3 thin films. Sensors Actuators A Phys. 77, 106–112 (1999).

Murakami, S. at al. Development of Piezoelectric MEMS Vibration Energy Harvester Using (100) Oriented BiFeO3 Ferroelectric Film. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 476, 012007 (2013).

Xiao, H., Wang, X. & John, S. A multi-degree of freedom piezoelectric vibration energy harvester with piezoelectric elements inserted between two nearby oscillators. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 68–69, 138–154 (2016).

Roundy, S. & Wright, P. K. A piezoelectric vibration based generator for wireless electronics. Smart Mater. Struct. 13, 1131–1142 (2004).

Aramaki, M., Kariya, K., Yoshimura, T., Murakami, S., Fujimura, N. Thickness dependence of piezoelectric properties of BiFeO3 films fabricated using rf magnetron sputtering system. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 55, 10TA16 (2016).

Yoshimura, T. Microenergy harvesting using BiFeO3 films. In Nanoscale Ferroelectric-Multiferroic Materials for Energy Harvesting Applications (ed. Yoshimura, T.) (Elsevier, 2019).

Aramaki, M., Yoshimura, T., Murakami, S., Kanda, K. & Fujimura, N. Electromechanical characteristics of piezoelectric vibration energy harvester with 2-degree-of-freedom system. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 133902 (2019).

Wu, H., Tang, L., Yang, Y. & Soh, C. K. A compact 2 degree-of-freedom energy harvester with cut-out cantilever beam. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 51, 040211 (2012).

Suresh, K., Shankar, K. & Sujatha, C. A novel passive mechanism to improve power output in 2DOF piezoelectric vibration energy harvester. Smart Mater. Struct. 28, 115016 (2019).

He, Q. et al. A novel two-degree-of-freedom nonlinear piezoelectric energy harvester with a stopper for broadband low-frequency vibration. AIP Adv. 13, 085014 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (JST CREST; Grant No. JPMJCR20Q2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sengsavang Aphayvong: formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft. Shuichi Murakami: investigation, resources, writing—review \& editing. Norifumi Fujimura: resource, supervision, wwriting—review \& editing. Takeshi Yoshimura: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing-original draft, writing—review \& editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aphayvong, S., Murakami, S., Fujimura, N. et al. Piezoelectric MEMS vibration energy harvester using BiFeO3 film and dynamic magnifier for impulsive forces. Sci Rep 16, 3443 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33429-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33429-1