Abstract

This study reports the synthesis and doping of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) with metalated porphyrins-nickel [Ni-t(OH)4-Por] (M1-Por), zinc [Zn-t(OH)4-Por] (M2-Por), and manganese [Mn-t(OH)4-Por] (M3-Por) to develop reduced graphene oxide–porphyrin nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por). These nanocomposites were thoroughly characterized using UV–Vis, FT-IR, 1H NMR, PXRD, and SEM techniques, and their remarkable antimicrobial activity was further supported by insilico molecular docking studies. The antimicrobial efficacy of the metalloporphyrins (M1-Por, M2-Por, and M3-Por) and their hybrids (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por) was assessed against various bacterial strains (Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Enterococcus faecium gram-positive strains, Klebsiella pneumonia, and Escherichia coli gram-negative strains) and fungal strains (Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans). Among the metalloporphyrin complexes, (M3-Por) exhibited the highest activity, attributed to the redox-active Mn(II) center and its strong binding affinity (− 10.54 kcal/mol) through multiple hydrogen bonds. Hybrid nanocomposites demonstrated superior bioactivity, with (rGO-M3-Por) achieving the lowest binding energy (− 14.39 kcal/mol) and extensive hydrogen bonding with ARG24 and ARG27. Molecular docking and dynamics simulations with S. aureus nucleoside diphosphate kinase revealed stable interactions involving hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking, and hydrophobic contacts. Furthermore, insilico ADMET studies indicated good drug-likeness, non-toxicity, and potential for safe oral administration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rise of antibiotic-resistant infectious diseases has become a major public health concern, making treatments increasingly challenging. With resistance escalating at an alarming rate, developing effective antimicrobial agents and control strategies is more crucial than ever1,2. While many studies focus on developing alternatives to combat antibiotic resistance, their effectiveness varies and does not always match that of traditional antibiotics. Recently, our research team has explored the biological field, utilizing porphyrin compounds to limit the spread of harmful microbes. Given their potential, developing porphyrin-based antibacterial materials presents a promising strategy for inhibiting microbial growth3,4. Porphyrins and metalloporphyrin compounds have gained significant attention due to their structural diversity and versatile applications, including gas storage, chemical sensing, heterogeneous catalysis, and antimicrobial properties5,6,7,8. Recent advancements in porphyrin chemistry have further expanded their utility in photodynamic therapy, optoelectronic devices, and solar energy storage. Notably, invitro studies have demonstrated their effectiveness against yeasts and viruses, reinforcing their potential as antimicrobial agents9. As antibiotic-resistant bacteria continue to pose serious health risks, the development of new antibacterial complexes becomes increasingly urgent10,11,12,13. Antibacterial materials play a crucial role in combating infections caused by various pathogenic bacteria, including Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, Streptococcus mutans, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Vibrio harveyi, and Enterococcus faecalis. These bacterial species are major contributors to severe infections, necessitating the use of diverse antibacterial agents such as metal ions, metal oxides, antibiotics, and antimicrobial peptides14. While metals and metal oxides exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, that also demonstrate toxicity toward certain mammalian cells15,16,17. Similarly, antimicrobial peptides, though potent, have been associated with cytotoxic effects and high production costs18.

To address these limitations, porphyrin and metalloporphyrin nanomaterials have emerged as promising antimicrobial agents due to their ability to catalyze peroxidase and oxidase reactions, leading to effective microbial inhibition through photon absorption and reactive oxygen species generation19,20. The structural versatility of porphyrins allows them to mimic biological active sites such as hemoproteins (e.g., hemoglobin, myoglobin, cytochrome P-450), thereby supporting applications in energy conversion, catalysis, optoelectronics, biosensors, and electronic devices. Furthermore, meso-tetra arylmetalloporphyrins serve as key building blocks for microporous crystalline solids, further enhancing their functional potential21. Despite their promising antimicrobial properties, metalloporphyrin systems face challenges such as porphyrin aggregation in physiological media due to the presence of salts22. To overcome these issues and enhance antibacterial efficacy, various nanofillers-including carbon nanomaterials, resins, and magnetic nanoparticles-have been incorporated into porphyrin macrocycles23,24. Among these, graphene oxide (GO) has emerged as a particularly effective nanofiller due to its high specific surface area, excellent physicochemical properties, and abundant oxygen-containing functional groups (epoxy, hydroxyl, and carboxyl). The integration of porphyrin derivatives with GO results in hybrid nanocomposites that combine the exceptional properties of both materials25, significantly enhancing their antimicrobial potential. Over years of research, GO has been explored as a therapeutic agent for antimicrobial and wound healing applications26,27. Graphene-based nanomaterials exhibit remarkable antibacterial activity, largely due to their ability to encapsulate antibiotics within their nanoscale dimensions28, thereby enhancing antibiotic efficacy and combating resistance29,30. As carriers and delivery agents, GO nanomaterials can penetrate bacterial cell membranes and target intracellular sites, ultimately disrupting microbial metabolism by causing leakage of cellular components31,32. Hybrid nanocomposites, such as amino-functionalized metalloporphyrin-anchored GO, have demonstrated the ability to inhibit S. aureus growth33. Similarly, porphyrin-fullerene C60 polymeric films have shown antibacterial activity against both S. aureus and E. coli34. Additionally, metal-decorated, porphyrin-functionalized graphene, synthesized through an eco-friendly method, has demonstrated excellent biocompatibility and strong antibacterial activity, attributed to optimized covalent and non-covalent interactions35. Recent studies on zinc porphyrin complexes with –COOH groups have shown superior antimicrobial activity, with docking and molecular dynamics simulations confirming their stable binding with S. aureus kinase and pharmacokinetics analysis supporting their drug-likeness and safety36.

In this study, we report the synthesis of the free-base porphyrin, 5,10,15,20-meso-tetrakis(4-(hydroxy)phenyl)porphyrin (Por), and its subsequent metalation with three different divalent metal ions-Ni(II), Zn(II), and Mn(II), resulting in the formation of metalloporphyrin complexes: Ni(II) porphyrin (M1-Por), Zn(II) porphyrin (M2-Por), and Mn(II) porphyrin (M3-Por), respectively. To further enhance their functional properties, these metalloporphyrins were covalently anchored onto reduced graphene oxide (rGO) via ester linkages, forming hybrid nanocomposites rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por respectively. The formation of ester bonds was confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy, and the successful synthesis of the porphyrin ligands and their metalated counterparts was validated by a combination of analytical techniques, including 1HNMR, UV–Visible spectroscopy, FTIR spectroscopy, powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), and field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM). These characterization results demonstrated that the structural integrity of both porphyrins and rGO was preserved in the hybrid materials, supporting their potential for multifunctional applications. The antimicrobial potential of these metalloporphyrin complexes (M1-Por, M2-Por, and M3-Por), and porphyrin-based nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por) was further explored through both experimental and computational approaches. To complement these experiments, molecular docking studies were performed to evaluate the binding affinity and interaction modes of the synthesized metalloporphyrin nanocomposites with the nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK) receptor of S. aureus (PDB ID: 3Q89), a key enzyme involved in nucleotide metabolism and a promising target for antibacterial drug design. The docking simulations also provided insights into the stability of the ligand-receptor complexes under insilico physiological conditions. Altogether, these findings underscore the successful integration of porphyrin chemistry with nanomaterial design, highlighting the promising role of metalloporphyrin-graphene oxide hybrids as advanced antimicrobial agents for potential biomedical applications.

Experimental section

Chemicals

Analytical-grade chemicals were employed for the synthesis of free-base porphyrin ligands, metalated porphyrin complexes, and their corresponding metalloporphyrin-anchored graphene oxide nanocomposites. The solvents and other required chemicals, such as propionic acid, pyrrole, and 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde, required to synthesize metal-free porphyrin ligands were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and deployed without additional purification. Graphite flakes, potassium permanganate (KMnO4), manganese acetate, nickel acetate, and zinc acetate had been purchased from Alfa Aesar, whereas Loba supplied the N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF). Additional reagents and solvents, notably hydrogen peroxide, triethylamine (Et3N), methanol, and sulfuric acid, were purchased from Himedia Chemical Reagent Company.

Synthesis of free-base 5,10,15,20-meso-tetrakis(p-hydroxyphenyl)porphyrin (Por)

The target porphyrin molecule was synthesized according to a literature-reported method37. Briefly, 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (3.03 g, 20 mmol) and pyrrole (1.38 mL, 20 mmol) were added to 50 mL of refluxing propionic acid in a 250 mL round-bottom flask. The mixture was maintained at reflux (80 °C) for 30 min and then allowed to cool to room temperature. Subsequently, 20 mL of methanol was added, and the reaction mixture was further refluxed for 2–3 h. The reaction progress was monitored using thin-layer chromatography (TLC), and the crude product was purified by column chromatography using a methanol/chloroform (1:9) solvent system on basic alumina. The resulting dark purple product was collected, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to yield the purified porphyrin. The successful synthesis of porphyrin was confirmed by 1H NMR and UV–Visible absorption spectroscopy (Fig. 1a).

Yield: 18%; Rf = 0.60; UV–Vis. (DMF, λmax (nm)): 423 (Soret-band), 518, 559, 606, 657 (Q-band); FTIR (KBr, νmax, cm−1): 3506 ν(N–H), 3258 ν(O–H), 2919 ν(C–H), 1604 ν(C = C), 1519 ν(C = N), 1485 ν(C–N), 1170 ν(O–C); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): 10.00 (para, s, 4H(d), ArOH), 8.89 (s, 8H(a), β-pyrrole), 8.02 (ortho, d, 8H(b), ArH), 7.22 (meta, d, 8H(c), ArH), − 2.86 (s, 2H(e), N–H).

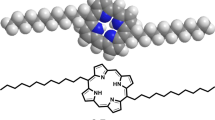

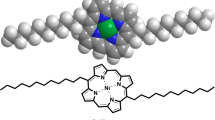

Synthesis of metallated-5,10,15,20-meso-tetrakis(p-hydroxyphenyl)porphyrin (M-Por)

The synthesized porphyrin ligand (Por) was metalated with nickel, zinc, and manganese ions respectively using their respective acetate salts. In a typical procedure, the free-base porphyrin ligand (Por) (0.3 g) and nickel acetate (0.6 g) were dissolved in 30 mL of methanol in a round-bottom flask. The reaction mixture was stirred continuously at 40–50 °C for 4 h to yield the nickel porphyrin complex [Ni–t(OH)4–Por] (M1-Por)38. The same protocol was followed for the preparation of zinc and manganese porphyrin complexes, [Zn–t(OH)4–Por] (M2-Por) and [Mn–t(OH)4–Por] (M3-Por), respectively, with the exception that the zinc complex was formed by stirring even at room temperature. The progress of metalation was monitored by UV–Vis and 1H NMR spectroscopy. After completion, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator, and the resulting metalloporphyrin complexes were isolated as precipitates, washed thoroughly, and dried. The overall synthetic route for the synthesis of porphyrin ligand and its corresponding metalloporphyrin complexes was outlined as (Fig. 1b).

[Ni-t(OH)4-Por] (M1-Por): Yield: 40%; Rf = 0.56; UV–Vis. (DMF, λmax (nm)): 420 (Soret-band), 531 (Q-band); FTIR (νmax, cm−1): 3253 ν(O–H), 2923 ν(C–H), 1653 ν(C=C), 1581 ν(C=N), 1504 ν(C–N), 1218 ν(C–O), 607ν(Ni–N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): 9.92 (para, s, 4H(d), ArOH), 8.86 (s, 8H(a), β-pyrrole), 7.79 (ortho, d, 8H(b), ArH), 7.14(meta, d, 8H(c), ArH).

[Zn-t(OH)4-Por] (M2-Por): Yield: 48%; Rf = 0.54; UV–Vis. (DMF, λmax (nm)): 426 (Soret-band), 562, 602 (Q-bands); FTIR (νmax, cm−1): 3305 ν(O–H), 2921 ν(C–H), 1659 ν(C=C), 1559 ν(C=N), 1509 ν(C–N), 1245 ν(C–O), 608 ν(Zn-N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): 9.82 (para, s, 4H(d), ArOH), 8.76 (s, 8H(a), β-pyrrole), 7.90–7.88 (ortho, d, 8H(b), ArH), 7.13–7.11(meta, d, 8H(c), ArH).

[Mn-t(OH)4-Por] (M3-Por): Yield: 45%; Rf = 0.58; UV–Vis. (DMF, λmax (nm)): 470 (Soret-band), 566, 604 (Q-bands); FTIR (νmax, cm−1): 3428 ν(O–H), 2917 ν(C–H), 1610 ν(C=C), 1520 ν(C=N), 1260 ν(C–N), 1101 ν(C–O), 546 ν(Mn-N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): 9.83 (para, s, 4H(d), ArOH), 7.44–7.42 (s, 8H(a), β-pyrrole), 7.05–7.04 (ortho, d, 8H(b), ArH), 7.26 (meta, d, 8H(c), ArH).

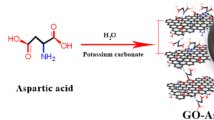

Synthesis of graphene oxide (GO)

The graphene oxide (GO) was synthesized from graphite flakes using well-established hummer’s method39. In the method, about 1 g of graphite flakes dissolved in conc. H2SO4 and H3PO4 in the 9:1 ratio was agitated for two hours in an ice bath using magnetic stirrer. During stirring, 8 g of KMnO4 was gradually added, resulting in an insignificant exotherm (35–40 °C), turning the brown color solution to purple color. Following that, the mixture was transferred to a water bath that was kept at approximately 35 °C and agitated the same for more than an hour until it became a thick paste. To this paste, 70 mL of deionized water was added, and the reaction temperature was raised to 95 °C. The oxidation process was halted by adding 12 mL of 30% solution of H2O2 and then filtered using the vacuum filtration. After then, the resultant liquid was periodically rinsed with deionized water until the pH was brought down to about 6. The resulting precipitates were dried at 45 °C in an oven following the drying lead to the formation of graphene oxide (GO) (Fig. 2a).

GO: Yield: 61%; UV–Vis (λmax, nm, DMF): 264 nm and 315 nm.

Synthesis of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) from graphene oxide (GO)

About 100 mg of graphene oxide was dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water taken in a 250 mL round bottom flask was swirled on a magnetic stirrer for 2–3 h. After the stipulated time, 10 mL of 50% solution of hydrazine-hydrate was incrementally added to the reaction mixture and the reaction mixture was sonicated for 30 min. After sonication, the mixture was refluxed for 4 h at 100 °C, followed by filtration, the resulting solution was thoroughly sterilized with anhydrous THF and dried under vacuum for an extended period40 till dryness (Fig. 2b).

rGO: Yield: 54%; UV–Vis (λmax, nm, DMF): 274 nm.

Synthesis of metalloporphyrin functionalized reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por)

The synthesized porphyrin complexes (M1-Por, M2-Por, and M3-Por) were successfully anchored onto reduced graphene oxide (rGO) to obtain the corresponding porphyrin-functionalized reduced graphene oxide hybrid nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por). For the synthesis of rGO-M1-Por, 0.09 g of nickel porphyrin (M1-Por) and 0.045 g of reduced graphene oxide (rGO)were added to a round-bottom flask containing a solvent mixture of 16 mL dimethylformamide (DMF) and 4 mL triethylamine41,42. The reaction mixture was heated at 70 °C for 72 h under inert atmosphere. After completion of the reaction, the flasks were removed from the heating source and left to cool overnight at room temperature. To the reaction mixture, 25 mL of diethyl ether was added, undergoing centrifugation at 9000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant, containing residual nickel porphyrin, was discarded, leaving behind black precipitates of the hybrid nanocomposites. These precipitates were thoroughly washed and dried for further investigation of their intrinsic properties. A similar procedure was followed for the synthesis of zinc and manganese porphyrin-functionalized reduced graphene oxide hybrid nanocomposites (rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por). The synthetic route for porphyrin-functionalized reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por) is illustrated in Fig. 3.

rGO-M1-Por: Yield: 48%; UV–Vis (λmax, nm, DMF): rGO band 274 nm, 429 (B band), 532 (Q band).

rGO-M2-Por: Yield: 52%; UV–Vis (λmax, nm, DMF): rGO band 274 nm, 421 (B band), 563, 605 (Q bands).

rGO-M3-Por: Yield: 51%; UV–Vis (λmax, nm, DMF): rGO band 275 nm, 472 (B band), 575,615 (Q bands).

Characterization techniques

Numerous sophisticated analytical techniques were implemented to characterize the resulting free-base porphyrin ligands, metalated porphyrin complexes (zinc, nickel, and manganese), and their corresponding nanocomposites. Utilizing TMS serving as the internal reference and DMSO-d6 as the solvent, the 1H NMR spectra of the free-base porphyrins and metalloporphyrin complexes were recorded on a JEOL ECX500 MHz spectrometer operating at 500 MHz. Their photophysical characteristics, such as UV–Visible spectra, were examined using a Spectroquant UV/VIS spectrophotometer (Model Prove 300), which has a spectral range of 250–750 nm. In an effort to recognize functional groups and molecular interactions, FTIR analysis was additionally performed out using a Perkin Elmer Spectrum 400 FTIR spectrophotometer, scanning in the 400–4000 cm−1 range. Employing the Field Emission Scanning Microscope-(FESEM)-2 (SOC), FE-SEM micrographs of the nanocomposites were captured. These techniques gave comprehensive details pertaining to the optical and structural characteristics of the synthesized compounds and their nanocomposites.

Biological evaluation

Antimicrobial activity

Using the agar-well diffusion method, the antimicrobial activity of the synthesized metal(II)-5,10,15,20-meso-tetrakis(4-hydroxyphenyl)porphyrins (M1-Por, M2-Por, and M3-Por) and their corresponding hybrid nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por) were assessed against a variety of bacterial and fungal strains, which involves Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus, Enterococcus, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumonia, Pseudomonas, and Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans, respectively.

Antibacterial activity (Kirby Bauer Method)

The agar well diffusion method is extensively employed for evaluating synthetic drugs’ or plant extracts’ antibacterial properties. The first step involved subculturing the bacterial isolates that had been kept on nutritional agar (NA) slants on NA plates and incubating them for 24 h at 37 °C. Following the agar well diffusion procedure, bacterial colonies were retrieved from the plates, suspended in 5 mL of nutrient broth, and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C to establish the bacterial inoculum. After then, using sterile cotton swabs, the 100 µl of culture was evenly distributed throughout the surface of sterile Mueller–Hinton agar plates and a sterile cork-borer was applied to puncture wells that exceeded 5 mm in diameter. The wells were filled with 40 µl of different samples of specified concentrations, negative control (DMSO) and gentamycin disc as a standard antibiotic was used. The plates then left at room temperature allowed to diffuse and incubated at 35 °C for 24 h for measuring the zone of inhibition43,44.

Antifungal activity (Agar-well diffusion method)

The antifungal properties of the reported samples have been evaluated employing the Aaar well diffusion approach. Initially, the fungal strains were incubated on a slant of Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA), subcultured on an SDA plate, and incubated for three days at 37 °C. A fungal inoculum has been produced through eliminating fungal spores from the three-day-old culture and immersing them in five milliliters of SD broth with 0.05 g/L chloramphenicol (to prevent bacterial growth and development). By applying sterile swabs, the test organisms were thoroughly injected onto the solidified SDA plate’s surface and with the help of a sterile cork-borer, holes with a diameter of 5 mm were made subsequent inoculation. As a reference medication, fluconazole 0.5 µg/µl was employed, and 40 µl of various samples with the specified quantities were added to the wells. The negative control used in the procedure was DMSO. After being allowed to diffuse for an hour at room temperature, the plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C and the zone of inhibition was assessed45,46.

Molecular docking studies

The binding interaction, mode, and affinity of the synthesized metal(II) porphyrin complexes and their corresponding nanocomposites with the S. aureus nucleoside diphosphate kinase receptor (PDB ID: 3Q89) were examined employing a molecular docking study utilizing the Auto-Dock (ADT) software version 1.5.7 (https://autodock.scripps.edu/). The first step entails preparing and minimizing the energy of the three-dimensional structures of the synthesized metal-based complexes using ChemDraw 2D and 3D software; ChemDraw 2D and Chem3D, PerkinElmer Informatics (https://informatics.perkinelmer.com/sites/chemoffice). The target protein, the S. aureus nucleoside diphosphate kinase receptor, was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/) and the water molecules, co-crystallized ligands, along with the heteroatoms were then eliminated from the recovered receptor to clean it. After that, polar hydrogens were added, and Chimera software, Version 1.19 (https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera) was used for allocating the appropriate charges and the subsequent complexes were docked onto the active site using the docking software AutoDock. Molecular docking Auto-Dock parameters were set to comply with previously published protocols47. Using the DISCOVERY Studio Visualizer software suite, Version 2021 (https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download) the docked compounds intermolecular hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions were creatively depicted in three dimensions48.

Results and discussion

UV–Visible spectroscopy

Th UV–Vis spectra of GO, rGO, the free-base porphyrin (Por), and metalloporphyrin complexes (M1–Por, M2–Por, and M3–Por) were recorded before and after the synthesis of nanocomposite. Generally, the electronic absorption spectra of porphyrins exhibit characteristic π–π* electronic transitions, including a strong Soret band (S0 → S2 transition) in the 410–440 nm region and the four weaker Q-bands (S0 → S1 transitions) in the 500 nm 700 nm region49,50. The free-base porphyrin (Por) displayed a Soret band at 421 nm and Q-bands at 518 nm, 556 nm, 595 nm, and 654 nm. Upon metalation, spectral changes were observed due to the increase in molecular symmetry from D2h (free-base porphyrin) to D4h (metalated porphyrins)51. The four Q-bands were reduced to two52,53, with a small shift in the Soret position depending on the coordinated metal. The observed absorption maxima for metallated porphyrin i.e., Soret band at 419 nm, 426 nm and 470 nm for MI-Por, M2-Por and M3-Por respectively. Accordingly, the Q-bands were emerged at 530 nm for M1-Por, at 560 nm, 602 nm for M2-Por, and at 564 nm 604 nm for M3-Por respectively54.

The graphene oxide (GO) exhibited an absorption maximum at 264 nm and a shoulder peak at 315 nm, attributed to the π–π* transition of aromatic C=C and the n–π* transition of C=O bonds, respectively55,56. Upon reduction, the rGO spectrum showed a red shift in the Soret absorption band to 274 nm, while the shoulder near 315 nm disappeared, consistent with the partial removal of oxygenated groups and restoration of sp2 carbon domains (Fig. 4a). After functionalization with metalloporphyrins, the nanocomposites rGO–M1–Por, rGO–M2–Por, and rGO–M3–Por displayed small bathochromic shifts of approximately 2–3 nm in both Soret band and Q-band positions relative to their corresponding metalloporphyrins. Further, the observed electronic absorption of Soret band at 429 nm, 421 nm and 472 nm for rGO–M1–Por, rGO–M2–Por and rGO–M3–Por whereas of Q-bands at 532 nm, 563, 605 nm and 575, 615 nm for rGO–M1–Por, rGO–M2–Por, and rGO–M3–Por respectively57, reveals that these minor red shifts suggests the possible π–π stacking interactions or electronic coupling between the porphyrin rings and the rGO surface (Fig. 4b–d). Additionally, a weak absorption near 274 nm, corresponding to the n–π* transition of C=O groups, was retained in the nanocomposites, indicating the presence of residual oxygen functionalities suggesting the partial reduction of graphene oxide.

FTIR spectroscopy

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to identify the functionalities like oxygen-containing functional groups present in GO, rGO, the free-base porphyrin, metalloporphyrin complexes, and their corresponding rGO-based nanocomposites. The FTIR spectra of graphene oxide (GO) displays characteristic absorption bands at 3322 cm−1 attributed to the stretching vibration of hydroxyl (–OH) groups, 1718 cm−1 (C=O stretching of carboxyl groups), 1620 cm−1 (C=C skeletal vibrations from sp2 domains), 1153 cm−1 (C–OH stretching), and 1036 cm−1 (C–O stretching)58. Upon reduction to rGO, notable spectral changes were observed resulting in the O–H stretching band at 3322 cm−1 and the C–OH band at 1153 cm−1, suggesting the removal of hydroxyl functionalities. The C=O stretching band persisted near 1718 cm−1, indicating the presence of residual carbonyl or carboxylic groups. Meanwhile, a band appearing near 1576 cm−1 is attributed to the restored sp2 carbon framework, consistent with partial graphitization after reduction59 (Fig. 5a). These spectral features collectively suggest that, although oxygen-containing groups were largely reduced, some residual carboxyl and epoxy functionalities remained in the rGO structure.

FTIR spectra of (a) free-base porphyrin (Por), (b) Graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO), (c) rGO, manganese porphyrin (M1-Por), and its hybrid nanocomposite (rGO-M1-Por), (d) rGO, manganese porphyrin (M2-Por), and its hybrid nanocomposite (rGO-M2-Por) and (e) rGO, manganese porphyrin (M3-Por), and its hybrid nanocomposite (rGO-M3-Por).

The FTIR spectrum of the free-base porphyrin (Por) shows a distinct N–H stretching vibration at 3496 cm−1, characteristic of the porphyrinic core. After metalation with Ni(II), Zn(II), and Mn(II) ions, this N–H band disappeared in the corresponding metalloporphyrin spectra (M1–Por, M2–Por, and M3–Por), indicating replacement of the N–H bonds by metal–nitrogen coordination. Additionally, weak absorption bands appearing between 400 and 600 cm−1 are assigned to M–N stretching vibrations, supporting successful metal incorporation into the porphyrin macrocycle (Fig. 5b). FTIR spectra of the rGO, metalloporphyrin, and rGO-metalloporphyrin nanocomposites show characteristic bands of both rGO and the porphyrin components. The C=C and C=O stretching vibrations observed at approximately 1576 cm−1 and 1718 cm−1, respectively, indicate that the sp2 carbon framework is retained, while the presence of carbonyl absorption suggests the existence of residual carboxylic groups. Also, the additional weak bands were appeared near 1730 cm−1 (rGO–M1–Por), 1726 cm−1 (rGO–M2–Por), and 1722 cm−1 (rGO–M3–Por) (Fig. 5c–e). These features may correspond to carbonyl stretching vibrations from residual oxygenated species or possible interfacial interactions between rGO and the metalloporphyrin complexes. These findings cumulatively corroborate that the porphyrin/rGO and metalloporphyrin/rGO nanocomposites were successfully fabricated60.

1HNMR spectroscopy

The 1HNMR spectra of 5, 10, 15, and 20-meso-tetrakis(4-hydroxyphenyl)porphyrin (Por) and its metalated derivatives (M1-Por, M2-Por, and M3-Por) reveal substantial data pertaining to the structural modifications triggered by metal coordination. The existence of inner-core imino (–NH) protons in the free-base porphyrin (Por) is verified by a distinctive singlet at about − 2.86 ppm. In the vicinity of 8.01 ppm to 8.03 ppm and 7.22 ppm to 7.23 ppm, respectively, the phenylic ortho (Hb) and meta (Hc) protons resonate as doublets, whereas the β-pyrrolic protons (Ha) appear as a singlet at 8.89 ppm. Additionally, the para-hydroxy protons (Hd) of the phenyl rings are observed at 10.00 ppm (Fig. 6a). Following metalation, the imino proton signal in all three complexes (M1-Por, M2-Por, and M3-Por) vanishes, indicating that the metal ion was successfully coordinated to the porphyrin core by substituting N–M bonds for the N–H protons. In furtherance of eliminating the NH signal, metal insertion induces the pyrrolic and phenyl protons’ chemical shifts to shift significantly upfield, specifically for the pyrrolic protons because of their close proximity to the metal center61.

In metalloporphyrin complex, M1-Por, the pyrrolic protons (Ha) shift slightly upfield to 8.86 ppm, while the phenylic ortho (Hb) and meta (Hc) protons shift to 7.18 ppm–7.16 ppm and 7.94 ppm–7.92 ppm, respectively. The para-hydroxy proton (Hd) appears at 9.92 ppm (Fig. 6b). In M2-Por, the shifts are more pronounced, with (Ha) resonating at 8.76 ppm, (Hb) at 7.13 ppm–7.11 ppm, and (Hc) at 7.90 ppm–7.88 ppm, while (Hd) shifts to 9.82 ppm (Fig. 6c). The most significant changes are observed in M3-Por, where (Ha) shows a considerable upfield shift to 7.44 ppm–7.42 ppm, and the phenylic protons (Hb) and (Hc) resonate at 7.05 ppm–7.04 ppm and 7.26 ppm, respectively, with (Hd) appearing at 9.83 ppm (Fig. 6d)62. These spectral changes clearly reflect the electronic effects of metal coordination on the porphyrin macrocycle, influencing the shielding and deshielding of nearby protons.

Powder x-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis

The structure and phase purity of metalated porphyrins (M1-Por, M2-Por, and M3-Por), graphene powder, graphene oxide (GO), reduced graphene oxide (rGO), and their corresponding porphyrin-functionalized reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites (rGO-M1-, rGO-M2, and rGO-M3-Por) were meticulously investigated using powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD). As is typical of highly ordered graphitic structures, the PXRD pattern of graphene powder reveals a prominent and sharp diffraction peak at 2θ = 26.60°, which corresponds to the (002) plane, with an interlayer spacing of d = 3.32 Å. The crystalline structure is broken by the insertion of oxygen-containing functional groups following oxidation to produce graphene oxide. This disruption results in a slight shift of the diffraction peak and a broadening of the pattern, indicating decreased crystallinity. In particular, GO shows an enlarged interlayer spacing of d = 8.03 Å, which is consistent with the presence of oxygenated groups intercalated between graphene layers, and a peak at 2θ = 11.02°, attributed to the (001) plane. Furthermore, a number of broad, less intense peaks at 2θ = 23.18°, 39.80°, 40.39°, and 46.14°, further reinforce the increased amorphous character and less structural order. As illustrated by the PXRD pattern of rGO, demonstrating a sharper and intense peak at 2θ = 24.78°, corresponding to a reduced interlayer spacing of d = 3.008 Å and (002) plane, reduction of GO to rGO reinstates some of the graphitic ordering through the elimination of oxygen functions. This modifications justifies the sp2-conjugated carbon network’s successful partial restoration and the corresponding increase in crystallinity (Fig. 7a)63.

Further functionalization of rGO with metalloporphyrins (M1-Por, M2-Por, M3-Por) to form hybrid nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, rGO-M3-Por) leads to significant changes in the diffraction patterns. The PXRD spectra of these nanocomposites not only retain the characteristic peak of rGO but also exhibit additional distinct peaks corresponding to the incorporated porphyrin complexes. Notably, sharp peaks emerge near 2θ ≈ 40°, specifically at 39.16° for rGO-M1-Por, 39.01° for rGO-M2-Por, and 41.01° for rGO-M3-Por, indicative of enhanced crystallinity as shown in Fig. 7b–d. Due to the strong π–π stacking interactions between the porphyrins’ aromatic rings and the graphene sheets, these intense reflections demonstrate that porphyrins are successfully integrating into the rGO matrix. The synthesis of well-ordered, thermodynamically stable hybrid nanostructures is facilitated by these interactions64. The variation in interlayer spacing across the different samples was calculated using Bragg’s law:

which shows a consistent decrease with increasing 2θ values. This trend reflects a progressive structural densification and strong interfacial interactions between the rGO framework and metalloporphyrin molecules. Collectively, the PXRD data confirm the successful synthesis and structural integrity of the rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por nanocomposites, showcasing their hybrid crystalline nature and potential for enhanced physicochemical properties43.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

The reduced graphene oxide (rGO) and its metalloporphyrin-functionalized nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por) have been investigated for surface morphology and structural features utilizing Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM). This analysis provided essential insights into particle size distribution, surface features, and morphological uniformity of the synthesized materials. The FE-SEM image of pristine rGO reveals a relatively smooth yet wrinkled surface, with out-of-plane deformations and a characteristic flaky, scale-like, layered texture. These silk-like ripples and wrinkles are typical of 2D graphene-based materials and result from the partial restoration of the sp2 carbon framework during the reduction of graphene oxide. Such crumpled and flexible layers are advantageous as they inhibit restacking and increase surface area, thereby offering a suitable platform for further functionalization. The observed morphology is consistent with previous literature reports, confirming the successful exfoliation and reduction of GO into rGO65 (Fig. 8a).

In contrast, the FE-SEM images of the metalloporphyrin/rGO nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por), exhibit significant morphological changes upon functionalization. The rGO sheets are visibly decorated with particle-like features corresponding to the metalloporphyrin complexes. The nanocomposite rGO-M1-Por demonstrates a uniform distribution of sharp-edged, plate-like crystalline structures anchored on the rGO surface. These well-defined features suggest strong π–π stacking or coordination interactions between the porphyrin rings and the graphene sheets, contributing to the enhanced crystallinity and ordered domains. Such morphology is in agreement with previously reported Zn–porphyrin/graphene hybrid systems, where regular crystalline structures were formed due to effective immobilization of porphyrins onto graphene66 (Fig. 8b). Also, the SEM image of rGO-M2-Por, which reveals a more disordered and rougher morphology. The image shows dense, irregular aggregates that obscure the underlying rGO sheets, indicating either a high degree of metalloporphyrin loading or encapsulation. The amorphous and compact appearance of the composite suggests strong interfacial interactions between the metal complex and rGO, leading to significant aggregation and a departure from the typical planar structure of rGO (Fig. 8c). In contrast, corresponding to nanocomposite rGO-M3-Por, exhibits a heterogeneous and granular surface morphology. The image reveals a mixture of clustered, granular particles and fragmented sheet-like remnants. This structure suggests partial wrapping or embedding of metalloporphyrin aggregates within the rGO layers, indicating a distinct interaction mode or coordination environment compared to rGO-M1-Por and rGO-M2-Por. The morphology also implies a lower degree of crystallinity or a more amorphous nature of the metalloporphyrin complex used in rGO-M3-Por67 (Fig. 8d). Overall, the progressive morphological evolution from rGO to the rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por nanocomposites confirms successful functionalization with metalloporphyrin complexes. Each nanocomposite demonstrates a unique dispersion pattern and structural integration, depending on the nature and coordination chemistry of the incorporated metal center. These observations underscore the tunability and versatility of rGO-based hybrid materials, highlighting their potential for applications in catalysis, sensing, and antimicrobial systems.

Biological studies

Invitro antibacterial and antifungal activities

The metallated porphyrins (M1-Por, M2-Por, and M3-Por) and their respective hybrid nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por) were tested for their invitro antimicrobial activity against bacterial strains namely Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Enterococcus faecium, (Gram-positive), Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, (Gram-negative) bacterial strains and Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans fungal strains respectively Table 1. The experimental results indicated that among the synthesized metal(II) porphyrin complexes, the M3-Por complex demonstrates the highest antimicrobial activity, especially against both gram-positive and fungal strains, due to variable coordination geometry and redox properties of Mn(II) that augment its biological interactions68. The M2-Por complex exhibits potent antibacterial properties, particularly against gram-negative Escherichia coli, possibly attributable to the d10 electronic configuration of Zn(II), that enhances membrane penetration and enzyme inhibition69. The M1-Por exhibits moderate activity, potentially constrained by its square planar shape, which may hinder biological accessibility70. The hybrid nanocomposites rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por, exhibit greater bioactivity relative to their parent complexes, with rGO-M3-Por distinguished by its exceptional antibacterial and antifungal properties, presumably attributable to its expanded surface area, enhanced solubility, and improved cellular absorption. These findings underscore the essential importance of metal centre selection and nanocomposite integration in modulating the antibacterial efficacy of porphyrin-based systems71.

The enhanced antimicrobial mechanism of rGO–porphyrin nanocomposites may be explained by the synergistic interplay between reduced graphene oxide and metalloporphyrins. The conductive π-conjugated network of rGO facilitates efficient electron transfer and stabilizes charge-separated states, thereby enhancing reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation through redox cycling of the metal centers. Concurrently, strong π–π stacking and hydrophobic interactions promote close association of the nanocomposites with microbial membranes, increasing local concentration and contact efficiency. The large surface area of rGO further amplifies adsorption and catalytic sites, leading to elevated oxidative stress, membrane disruption, and superior antimicrobial performance against both bacterial and fungal pathogens.

Molecular docking studies

Recent breakthroughs in molecular docking studies have markedly expedited drug design and discovery by facilitating accurate predictions of ligand-target interactions at the atomic level72,73. Docking has transitioned from a mere screening tool to an essential element of rational drug design, incorporating molecular dynamics, pharmacophore modelling, and AI-driven algorithms for improved precision. Recent results encompass the discovery of new inhibitors for emerging infectious diseases, the repurposing of FDA-approved medications, and the structure-based refinement of lead compounds aimed at kinases, proteases, and viral proteins74,75,76,77. Moreover, hybrid methodologies that integrate docking with machine learning have enhanced the efficacy of virtual screening, hence decreasing the time and expenses associated with drug discovery. These achievements establish molecular docking as a crucial method in the development of more effective, selective, and safer medicinal medicines in oncology, neurology, infectious illnesses, and other fields.

The synthesized metallated-5,10,15,20-meso-tetrakis(4-hydroxyphenyl)porphyrins (M1-Por, M2-Por, M3-Por) and their respective hybrid nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, rGO-M3-Por) were docked with S. aureus nucleoside diphosphate kinase receptor (PDB ID: 3Q89) to study the binding modes and affinity of the complexes with the receptor molecule. The molecular docking results depicted in (Tables 2 and 3), along with the visual representations in Fig. 9, furnish substantial evidence regarding the binding efficacy of the synthesized metal(II) porphyrin complexes (M1-Por, M2-Por, M3-Por) and their hybrid nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, rGO-M3-Por) with S. aureus nucleoside diphosphate kinase (PDB ID: 3Q89). Among the synthesized metal complexes, M3-Por demonstrated the most advantageous estimated free binding energy (− 10.54 kcal/mol), validated by its extensive hydrogen bonding network with critical residues including ARG15, ARG27, GLU20, and ASN16, exhibiting bond lengths between 1.64 and 2.36 Å, signifying robust and stable interactions. M1-Por and M2-Por exhibited marginally elevated binding energies (− 8.84 and − 8.88 kcal/mol, respectively), characterized by a reduced number of hydrogen bonds and diminished residue diversity. The hybrid nanocomposites exhibited significantly higher binding affinities, especially rGO-M3-Por, which displayed the lowest binding energy (− 14.39 kcal/mol), signifying a synergistic effect of the nanocomposite structure in facilitating stronger receptor contacts. The rGO-M3-Por nanocomposite established many hydrogen bonds with ARG24 and ARG27, exhibiting minimal bond distances, as low as 1.20 Å, indicative of elevated binding specificity and stability. The 3D docked further validate these interactions, demonstrating profound embedding of the drugs within the active sites of receptor molecule, especially for M3-Por and rGO-M3-Por, which correspond with their enhanced in vitro antimicrobial profiles (Fig. 9). The results indicate that the selection of metal centres and the construction of nanocomposites are essential for improving the bio-interaction potential of porphyrin-based therapies.

Overall, the experimental and molecular docking results consistently validated each other, indicating a robust link between the observed antibacterial activity and the predicted binding affinities of the produced complexes. This agreement affirms that robust and persistent molecular contacts are essential for improved biological activity, substantiating the synergistic application of experimental assays and computational docking as an effective strategy in drug design and discovery.

Conclusion

In the present investigation, graphene oxide was first prepared using Hummer’s method, followed by reduction to synthesized reduced graphene oxide (rGO). The resulting rGO was subsequently functionalized with synthesized metalloporphyrin complexes (M1-Por, M2-Por, and M3-Por) to obtain metalloporphyrin-functionalized rGO nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, and rGO-M3-Por). The free-base porphyrin ligand, its corresponding metalated complexes, and the resulting nanocomposites were thoroughly characterized using a range of spectroscopic and analytical techniques, including 1H NMR, UV–Vis, FTIR, PXRD, and FE-SEM. Photophysical studies revealed a durable interactive affinity between the metalloporphyrin complexes and the rGO, indicating strong non-covalent interactions that likely contribute to the structural and functional integrity of the nanocomposites. These materials were then evaluated for their antimicrobial efficacy against a panel of bacterial strains-Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Enterococcus faecium (Gram-positive), and Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Gram-negative)-as well as fungal strains such as Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans. Notably, among the nanocomposites, rGO-M3-Por demonstrated the highest antimicrobial activity, outperforming rGO-M1-Por and rGO-M2-Por, while among the metal complexes, M3-Por was the most active, followed by M2-Por and M1-Por. This enhanced performance of rGO-M3-Por and M3-Por is attributed to the variable coordination geometry and redox-active properties of Mn(II), which may promote stronger biological interactions. Moreover, it was observed that increased substitution on the porphyrin ring improved the biological activity of the nanocomposites, indicating a structure–activity relationship. Molecular docking studies further supported these findings, revealing that the hybrid nanocomposites (rGO-M1-Por, rGO-M2-Por, rGO-M3-Por) exhibited significantly higher binding affinities with microbial target proteins compared to the metalloporphyrin complexes (M1-Por, M2-Por, M3-Por). Among them, rGO-M3-Por showed the strongest binding affinity (− 14.39 kcal/mol), which correlates well with its enhanced antimicrobial performance. The docking analyses also revealed that the nanocomposites formed a higher number and more stable hydrogen bonds with active site residues, suggesting better stability and stronger molecular recognition. These enhanced interactions are likely facilitated by the increased surface area and the synergistic π–π stacking and electrostatic interactions provided by the rGO platform. Taken together, the biological and computational results strongly support that nanocomposite formation significantly enhances antimicrobial potential, with rGO-M3-Por emerging as a particularly promising candidate due to its superior binding affinity and biological activity.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

References

Hutchings, M. I., Truman, A. W. & Wilkinson, B. Antibiotics: Past, present and future. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 51, 72–80 (2019).

Gillespie, S. H. Antibiotic resistance in the absence of selective pressure. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 17, 171–176 (2001).

Amiri, N. et al. Two novel magnesium(II) meso-tetraphenylporphyrin coordination complexes: syntheses, structure elucidation, spectroscopy, photophysical properties and antibacterial activity. J. Solid State Chem. 258, 477–484 (2018).

Ezzayani, K. et al. Coordination polymer with magnesium porphyrin: synthesis, structure, photophysical properties and antibacterial activity. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 514, 119960 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Nanoporous porphyrin polymers for gas storage and separation. Macromolecules 45, 7413–7419 (2012).

Lvova, L. et al. SWCNTs modified with porphyrins for chemical sensing applications. Procedia Eng. 5, 1043–1046 (2010).

Fidalgo-Marijuan, A. et al. Heterogeneous catalysis by μ-O-[FeTCPP]₂ dimers: unusual superhyperfine EPR structure. Dalton Trans. 44, 213–222 (2015).

Fields, K. B. et al. Cobalt carbaporphyrin-catalyzed cyclopropanation. Chem. Commun. 47, 749–751 (2011).

Sautour, M. et al. Acid-functionalized porphyrins with antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria, yeasts and fungi. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 109, 117810 (2024).

Vzorov, A. N., Dixon, D. W., Trommel, J. S., Marzilli, L. G. & Compans, R. W. Inactivation of HIV-1 by porphyrins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 3917–3925 (2002).

Carré, V. et al. Fungicidal meso-arylglycosylporphyrins: influence of sugar substituents on yeast photo-damage. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 48, 57–62 (1999).

Dizaj, S. M., Lotfipour, F., Barzegar-Jalali, M., Zarrintan, M. H. & Adibkia, K. Antimicrobial activity of metals and metal oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 44, 278–284 (2014).

Gold, K., Slay, B., Knackstedt, M. & Gaharwar, A. K. Antimicrobial activity of metal and metal-oxide nanoparticles. Adv. Ther. 1, 1700033 (2018).

Dizaj, S. M., Lotfipour, F., Barzegar-Jalali, M., Zarrintan, M. H. & Adibkia, K. Antimicrobial activity of metals and metal oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 44, 278–284 (2014).

Ebbensgaard, A. et al. Comparative antimicrobial activity of peptides against pathogenic bacteria. PLoS ONE 10, e0144611 (2015).

Moritz, M. & Geszke-Moritz, M. Advances in synthesis, immobilization and applications of antibacterial nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 228, 596–613 (2013).

Hibbing, M. E., Fuqua, C., Parsek, M. R. & Peterson, S. B. Bacterial competition in the microbial jungle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 15–25 (2010).

Frei, A., Verderosa, A. D., Elliott, A. G., Zuegg, J. & Blaskovich, M. A. Metals to combat antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Rev. Chem. 7, 202–224 (2023).

Stojiljkovic, I., Evavold, B. D. & Kumar, V. Antimicrobial properties of porphyrins. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs. 10, 309–320 (2001).

Yamano, K. & Kojima, W. Molecular functions of autophagy adaptors in ubiquitin-driven mitophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1865, 129972 (2021).

Ezzayani, K. et al. Magnesium(II) porphyrin complex: synthesis, biological evaluation and docking. J. Mol. Struct. 1287, 135702 (2023).

Monteiro, A. R., Neves, M. G. P. & Trindade, T. Graphene oxide functionalized with porphyrins: synthetic routes and bio-applications. ChemPlusChem 85, 1857–1880 (2020).

Bi, C. et al. Ag+-decorated PCN-222@graphene oxide–chitosan foam adsorbent for U(VI) recovery with antibacterial activity. Sep. Purif. Technol. 281, 119900 (2022).

Hu, Y. et al. Antioxidant activity of Inonotus obliquus polysaccharide and protection against chronic pancreatitis in mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 87, 348–356 (2016).

Fu, X. et al. Graphene oxide as a nanofiller for polymer composites. Surf. Interfaces. 37, 102747 (2023).

Xu, C., Han, A., Virgil, S. C. & Reisman, S. E. Chemical synthesis of (+)-ryanodine and (+)-20-deoxyspiganthine. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 278–282 (2017).

Khan, M. S., Abdelhamid, H. N. & Wu, H. F. NIR laser-mediated surface activation of graphene oxide nanoflakes for antibacterial, antifungal and wound-healing treatment. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 127, 281–291 (2015).

Mamun, M. M., Sorinolu, A. J., Munir, M. & Vejerano, E. P. Nanoantibiotics: functions and properties at the nanoscale to combat antibiotic resistance. Front. Chem. 9, 687660 (2021).

Xu, Y., Li, H., Li, X. & Liu, W. What happens when nanoparticles encounter bacterial antibiotic resistance?. Sci. Total Environ. 876, 162856 (2023).

Ghulam, A. N. et al. Graphene oxide materials: applications and toxicity on living organisms and environment. J. Funct. Biomater. 13, 77 (2022).

Palmieri, V. et al. Contradictory effects of graphene oxide against human pathogens. Nanotechnology 28, 152001 (2017).

Yasmeen, R., Singhaal, R., Bajju, G. D. & Sheikh, H. N. Tin porphyrin–graphene oxide hybrid composites as catalysts for 4-nitrophenol reduction. J. Chem. Sci. 134, 111 (2022).

Marcano, D. C. et al. Improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS Nano 4, 4806–4814 (2010).

Rayati, S., Rezaie, S. & Nejabat, F. Mn(III)-porphyrin/graphene oxide nanocomposite for aerobic hydrocarbon oxidation. C. R. Chim. 21, 696–703 (2018).

Sah, U., Sharma, K., Chaudhri, N., Sankar, M. & Gopinath, P. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy with SWCNT–porphyrin conjugates. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 162, 108–117 (2018).

Díez-Pascual, A. M. Antibacterial and antiviral applications of carbon-based polymeric nanocomposites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 10511 (2021).

Venkatramaiah, N. & Venkatesan, R. Optical and luminescence investigations of hydroxy-substituted porphyrins in borate glasses. Solid State Sci. 13, 616–624 (2011).

Kundan, S., Bajju, G. D., Gupta, D. & Roy, T. K. Axially ligated Zn(II) porphyrin complexes: Spectroscopic, computational and antibacterial studies. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 64, 1379–1395 (2019).

Saravanan, M. et al. Antibacterial and biocompatible porphyrin–metal decorated reduced graphene oxide. Surf. Interfaces. 46, 103932 (2024).

Alam, S. N., Sharma, N. & Kumar, L. Synthesis of graphene oxide by modified Hummers’ method and thermal reduction to rGO. Graphene. 6, 1 (2017).

Yasmeen, R., Ahmed, S., Bhat, A. R., Bajju, G. D. & Sheikh, H. N. Antimicrobial nanocomposites from graphene oxide functionalized with zinc porphyrin complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 569, 122155 (2024).

Tene, T. et al. Mercury adsorption on oxidized graphenes. Nanomaterials. 12, 3025 (2022).

Yasmeen, R., Ahmed, S., Bhat, A. R., Bajju, G. D. & Sheikh, H. N. Antimicrobial nanocomposites from graphene oxide functionalized with zinc porphyrin complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 569, 122155 (2024).

Meshram, P. et al. Isatin-based Schiff bases: synthesis, antibacterial activity, docking and pharmacokinetics. J. Mol. Struct. 1322, 140508 (2025).

Kumar, A. et al. Schiff-based Cu(II), Zn(II) and Pd(II) complexes: antimicrobial, DNA-binding and docking studies. J. Mol. Struct. 1315, 138695 (2024).

Gour, P. B. et al. Benzo[d]oxazole-2-thio and oxazolo[4,5-b]pyridine-2-thio derivatives: design, docking, pharmacokinetics and pharmacophore insights. J. Mol. Struct. 1333, 141705 (2025).

Bharathi, S., Mahendiran, D., Ahmed, S. & Rahiman, A. K. Silver(I), nickel(II) and copper(II) thiosemicarbazone–ibuprofen complexes: antiproliferative and docking studies. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 79, 127211 (2023).

Ahmed, S., Mahendiran, D., Bhat, A. R. & Rahiman, A. K. Nickel(II) and copper(II) thiosemicarbazone–pefloxacin complexes: antiproliferative, docking and pharmacokinetics studies. Chem. Biodivers. 20, e202300702 (2023).

Raveena, Singh, M. P., Sengar, M. & Kumari, P. Synthesis of graphene oxide/porphyrin nanocomposite for photocatalytic degradation of crystal violet dye. Chem. Select. 8, e202203272 (2023).

Zheng, W., Shan, N., Yu, L. & Wang, X. UV–visible, fluorescence and EPR properties of porphyrins and metalloporphyrins. Dyes Pigm. 77, 153–159 (2008).

Dechan, P. & Bajju, G. D. Preparations of core H2O-bound 5,10,15,20-tetrakis-4-chlorophenyl porphyrin, P1, and O-methylation of phenol and its p-substituted analogues. ACS Omega 5, 17775–17786 (2020).

Dechan, P., Bajju, G. D., Sood, P. & Dar, U. A. Synthesis and single crystal structure of a new polymorph of 5,10,15,20-tetrakis-(4-chlorophenyl) porphyrin, H2TTPCl4: Spectroscopic investigation of aggregation of H2TTPCl4. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 666, 79–93 (2018).

Huang, X., Nakanishi, K. & Berova, N. Porphyrins and metalloporphyrins: versatile circular dichroic reporter groups for structural studies. Chirality 12, 237–255 (2000).

George, R. C., Torimiro, N., Daramola, O. B. & Olajide, A. A. Zinc, tin and silver porphyrins (TPP, TCPP, TMPP, THPP, TPPS, TMPyP) as photosensitizers in antibacterial photodynamic therapy for chronic wounds: a screening study. Ethiop. J. Sci. Technol. 15, 187–207 (2022).

Taniguchi, M., Wu, Z., Sterling, C. D. & Lindsey, J. S. Digitization of print-based absorption and fluorescence spectra-extracting clarity from clutter. Proc. SPIE. 12398, 23–42 (2023).

Wolf, M. et al. Panchromatic light funneling through the synergy in hexabenzocoronene–(metallo)porphyrin–fullerene assemblies to realize the separation of charges. Chem. Sci. 11, 7123–7132 (2020).

Johra, F. T. & Jung, W. G. Effect of pH on the synthesis and characteristics of RGO–CdS nanocomposites. Appl. Surf. Sci. 317, 1015–1021 (2014).

Singhaal, R., Tashi, L., Devi, S. & Sheikh, H. N. Hybrid photoluminescent material from lanthanide fluoride and graphene oxide with strong luminescence intensity as a chemical sensor for mercury ions. New J. Chem. 46, 6528–6538 (2022).

Kumari, R., Sahai, A. & Goswami, N. Effect of nitrogen doping on structural and optical properties of ZnO nanoparticles. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 25, 300–309 (2015).

Rayati, S., Rezaie, S. & Nejabat, F. Mn(III)-porphyrin/graphene oxide nanocomposite as an efficient catalyst for the aerobic oxidation of hydrocarbons. C. R. Chim. 21, 696–703 (2018).

Rostami, M., Rafiee, L., Hassanzadeh, F., Dadrass, A. R. & Khodarahmi, G. A. Synthesis of some new porphyrins and their metalloderivatives as potential sensitizers in photodynamic therapy. Res. Pharm. Sci. 10, 504–513 (2015).

El-Khalafy, S. H., Hassanein, M. T., Alaskary, M. M. & Salahuddin, N. A. Synthesis and characterization of Co(II) porphyrin complex supported on chitosan/graphene oxide nanocomposite for efficient green oxidation and removal of Acid Orange 7 dye. Sci. Rep. 14, 17073 (2024).

Faiz, M. A., Azurahanim, C. C., Raba’ah, S. A. & Ruzniza, M. Z. Low cost and green approach in the reduction of graphene oxide using palm oil leaves extract for potential in industrial applications. Results Phys. 16, 102954 (2020).

Bhagat, M., Rajput, S., Arya, S., Khan, S. & Lehana, P. Biological and electrical properties of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles. Bull. Mater. Sci. 38, 1253–1258 (2015).

Zvyagina, A. I. et al. Layer-by-layer assembly of porphyrin-based metal–organic frameworks on solids decorated with graphene oxide. New J. Chem. 41, 948–957 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Hybrid of MoS2 and reduced graphene oxide: A lightweight and broadband electromagnetic wave absorber. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 7, 26226–26234 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. A sensitive porphyrin/reduced graphene oxide electrode for simultaneous detection of guanine and adenine. J. Solid State Electrochem. 20, 2055–2062 (2016).

Christianson, D. W. Structural chemistry and biology of manganese metalloenzymes. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 67, 217–252 (1997).

Zhao, Q., Huang, C. & Li, F. Phosphorescent heavy-metal complexes for bioimaging. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 2508–2524 (2011).

Kargar, H., Ardakani, A. A., Tahir, M. N., Ashfaq, M. & Munawar, K. S. Synthesis, spectral characterization, crystal structure determination and antimicrobial activity of Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes with the Schiff base ligand derived from 3,5-dibromosalicylaldehyde. J. Mol. Struct. 1229, 129842 (2021).

Naseem, T. & Waseem, M. A comprehensive review on the role of some important nanocomposites for antimicrobial and wastewater applications. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19, 2221–2246 (2022).

Sundaram, B. & Ahmed, S. Molecular docking: a computational approach streamlining drug design. In Mol. Model. Docking Tech. Drug Discov. Des. 371–400 (2025).

Akter, N. et al. Acylated glucopyranosides: FTIR, NMR, FMO, MEP, molecular docking, dynamics simulation, ADMET and antimicrobial activity against bacterial and fungal pathogens. Chem. Phys. Impact. 9, 100700 (2024).

Kumar, N., Sarma, H. & Sastry, G. N. Repurposing of approved drug molecules for viral infectious diseases: A molecular modelling approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 40, 8056–8072 (2022).

Maji, S., Badavath, V.N. & Ganguly, S. Drug repurposing and computational drug discovery for viral infections and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). In Drug Repurposing Comput. Drug Discov. 59–76 (2023).

Moshiri, J. et al. A targeted computational screen of the SWEETLEAD database reveals FDA-approved compounds with anti-dengue viral activity. MBio 11(6), 10–1128 (2020).

Winkler, D. A. Computational repurposing of drugs for viral diseases and current and future pandemics. J. Math. Chem. 62, 2844–2879 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We are obliged to the University of Hyderabad for the SEM analysis, IIT Mandi for the 1HNMR, and Central University of Jammu for the FT-IR, UV-visible, and powder-XRD analysis. Further, We are thankful to the grant received from the PURSE-2023 (Promotion of University Research and Scientific Excellence) project for the assistance and resources provided were pivotal in the successful completion of this research.

Funding

We are thankful to the grant received from the PURSE-2023 (Promotion of University Research and Scientific Excellence) project for the assistance and resources provided were pivotal in the successful completion of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shivani Manhas: Writing the first draft of the manuscript. Simridhi Khajuria: Collection of content of the manuscript for the first draft. Monika Verma: Analysis of some studies like IHNMR Spectroscopy and FTIR Spectroscopy Sumeer Ahmed: Analysis of Antimicrobial studies Ajmal. R. Bhat: Analysis of Antimicrobial studies Vijay Jagdish Upadhye: Molecular Docking Studies Dr. Sujata Kundan: Experimental procedure, Analysis of physico-chemical studies like UV/VIS spectrophotometer, Powder X-ray diffraction analysis (PXRD), Scanning electron Microscopy (SEM), Writing the Antimicrobial studies, and Molecular docking studies data and Finalize the final draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Manhas, S., Khajuria, S., Verma, M. et al. Graphene oxide functionalized metalloporphyrins as advanced antimicrobial nanomaterials with integrated synthesis, characterization and molecular docking evaluations. Sci Rep 16, 3455 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33484-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33484-8