Abstract

The increasing threat of dye pollution in water resources underscores the urgent need for sustainable and cost-effective treatment solutions However, a gap remains in identifying efficient and reusable natural materials for dye removal. This study evaluates the potential of natural zeolite as an effective and reusable adsorbent for removing methylene blue dye from aqueous solutions. Natural zeolite was characterized using SEM, FTIR, XRD, and TGA techniques, and its adsorption performance was systematically tested under various conditions, including pH, adsorbent dosage, contact time, temperature, and initial dye concentration. The results revealed a maximum dye removal efficiency of 98.9% under optimized conditions (pH = 7, adsorbent dosage = 0.01 g/L, contact time = 60 min, temperature = 25 °C) and a monolayer adsorption capacity of 24.71 mg/g. The adsorption process conformed to the Langmuir isotherm and followed pseudo-second-order kinetics, indicating monolayer coverage and chemisorption mechanisms. Thermodynamic analysis confirmed the adsorption process was spontaneous and exothermic. Recycling experiments demonstrated the zeolite’s strong reusability, highlighting its potential as an economically viable and environmentally friendly method for wastewater treatment applications. Further research should explore real wastewater applications and scale-up potential to support practical implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid expansion of industrialization and urbanization in recent decades has markedly increased global water demand, resulting in severe contamination of freshwater resources1. Among the various pollutants, synthetic dyes released from textile, leather, cosmetic, and food industries represent a major environmental concern due to their chemically stable aromatic structures and strong resistance to biodegradation, which make them persistent in aquatic environments2,3,4. This critical situation has intensified the need for efficient water treatment technologies, particularly those capable of removing highly stable synthetic dyes from industrial effluents5,6,7.

Methylene blue (MB) is one of the most extensively used cationic dyes owing to its low cost and wide industrial applications; however, its discharge into water bodies poses significant environmental and human health risks. MB reduces light penetration, inhibits photosynthetic activity, and depletes dissolved oxygen, ultimately disrupting aquatic food webs. Chronic exposure has been associated with skin irritation, eye sensitivity, and neurological effects in humans3,4,8. Although conventional treatment methods—such as advanced oxidation processes, membrane filtration, coagulation–flocculation, and microbial degradation—are widely used, these technologies often suffer from high operational costs, intensive energy consumption, incomplete dye removal, and the generation of toxic by-products or sludge2,3,7,9. These limitations are particularly pronounced when dealing with persistent dyes like MB.

In contrast, adsorption has emerged as a cost-effective, simple, and environmentally friendly approach for dye removal, offering high efficiency even at low dye concentrations and minimizing secondary pollution10,11. The performance of this technique, however, depends strongly on the physicochemical characteristics of the adsorbent, including surface area, pore structure, and surface functional groups, which influence adsorption capacity, kinetics, and selectivity12. Recent progress in carbon-based nanomaterials, polymer composites, and bio-derived sorbents has strengthened the role of adsorption as a sustainable purification method, with natural zeolites receiving particular attention due to their high surface area, notable cation-exchange properties, and excellent thermal stability12,13,14.

A wide body of research has investigated the use of zeolites for dye removal. Turp et al.15 reported an 88% removal efficiency for MB using natural zeolite under optimized conditions (pH = 7, 0.5 g/L, 60 min), with adsorption fitting the Langmuir isotherm (R² = 0.993) and pseudo-second-order kinetics (R² = 0.999). Alabbad16 demonstrated the effective removal of DY50 dye by Jordanian zeolite, with adsorption best described by the Freundlich isotherm and pseudo-second-order kinetics. Imessaoudene et al.17 achieved 98.7% removal of Congo Red at pH = 3 and a dosage of 0.1 g/L, also fitting the Freundlich model and pseudo-second-order kinetics. A comprehensive review by Kaci et al.18 on Basic Red 46 highlighted adsorption as the most effective treatment technology and emphasized the widespread use of Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms. Other studies have explored low-cost adsorbents such as sugar scum19, olive-pomace-derived activated carbon20, and lemon verbena leaf waste21, demonstrating the sustainability and efficiency of agricultural by-products in removing dyes and organic pollutants.

Natural zeolite is particularly advantageous for MB removal due to its porous structure and high cation-exchange capacity. Its efficiency, however, is influenced by factors such as particle size, surface area, and contact time; for instance, finer zeolite particle sizes have shown improved performance, achieving up to 32.11% MB removal at low dye concentrations22. Further performance enhancements have been achieved through modification or composite formation. Zeolite–ZnO composites have demonstrated dual activity through adsorption and photocatalysis, achieving up to 98.68% MB degradation under UV irradiation23. Additionally, Alhogbi and Al Balawi24 developed a natural biosorbent composite (Zeo-FPT) using Saudi kaolin-based zeolite and palm tree fibers, achieving 87% removal under optimized conditions and up to 99% removal in water samples. Abd Elmaksod et al.25 further showed that TiO₂ impurities in Saudi kaolin act as active sites for MB photodegradation and remain in the anatase phase after transformation into NaP zeolite, enabling simultaneous adsorption and photocatalysis.

Despite these advancements, most studies have focused on modified or imported zeolites, leaving a significant gap regarding the use of locally available, unmodified Saudi natural zeolites for dye removal. Nizami et al.26 reported the presence of natural zeolite deposits across several regions of Saudi Arabia, especially in the Jabal and Harrat Shamah areas near Jeddah, where mineral types such as mordenite, heulandite/clinoptilolite, analcime, stilbite, thomsonite, natrolite, chabazite, and wairakite were identified. However, their application in dye remediation has received minimal attention, highlighting a critical need for research aimed at utilizing these abundant local resources in sustainable wastewater treatment.

To address this gap, the present study investigates the adsorption performance of natural zeolite sourced from northern Saudi Arabia for the removal of MB from aqueous solutions. Comprehensive characterization (SEM, FTIR, XRD, and TGA) was conducted to evaluate the material’s physicochemical properties, followed by batch adsorption experiments under various operational conditions. Adsorption mechanisms were examined using isotherm, kinetic, and thermodynamic models, and the reusability of the material was assessed through regeneration studies. The novelty of this work lies in demonstrating the feasibility of using locally sourced, unmodified natural zeolite as a practical and sustainable alternative to imported or chemically treated adsorbents for efficient dye removal from wastewater.

Materials and methods

Reagents and chemicals

Natural zeolite, sourced from the north of Saudi Arabia, was prepared by milling and sieving to obtain uniform particle sizes < 125 μm. Methylene blue (MB, C₁₆H₁₈ClN₃S; laboratory stain for microscopy, C.I. No. 52015, India) was used as the model dye. Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%, Scharlau Lab, Spain); sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98%, Polskie Odczynniki Chemiczne, Gliwice, Poland); and acetone (C₃H₆O, 99.5%, Panreac Sintesis, Barcelona, Spain) were utilized for solution preparation and pH adjustment.

Adsorption experiment

The adsorption experiments were conducted using the batch method. A methylene blue stock solution was prepared by dissolving MB powder in distilled water, and then diluted to the desired working concentrations. An accurately weighed amount of zeolite was added to 25 mL of MB solution at a predetermined initial concentration in Erlenmeyer flasks. The solution pH was adjusted using 0.1 M HCl or 0.1 M NaOH solutions, and measured with a calibrated pH meter. The mixtures were shaken in a water bath at 200 rpm and maintained at a constant temperature of 25 °C for 60 min to ensure equilibrium. After adsorption, the zeolite was separated from the aqueous solution by sedimentation (30 min). The residual concentration of MB in solution was measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV-1900i, Shimadzu, Japan) at 663 nm. The adsorption percentage (Eq. 1) and capacity (Eq. 2) were calculated using the following equations:

where Co (mg/L) and Ce (mg/L) are the initial and equilibrium concentrations of MB dye, V (L) is the volume of the solution, and m (g) is the natural zeolite mass. This procedure was repeated under varying conditions of pH, contact time, adsorbent dosage, temperature, and initial dye concentration to determine the optimum operating conditions for MB removal. Desorption was performed to evaluate the regeneration potential and reusability of the zeolite material. Regeneration was carried out using three different solvents—HCl, NaOH, and acetone—to desorb MB molecules and restore active sites.

The desorption efficiency (%desorption) (Eq. 3) for each solvent and the adsorption capacity were calculated using the following equation:

Where %desorption is the desorption percentage, \(\:{C}_{i}\) is the initial MB concentration before desorption (mg/L), and Ce is the MB concentrations after desorption (mg/L).

Characterization of natural zeolite

Functional groups of the natural zeolite were identified using FTIR spectroscopy (Spectrum One, PerkinElmer, USA) over the range of 600–4000 cm⁻¹. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM; JSM-IT300, JEOL, Japan) was utilized to investigate surface morphology. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) was used to determine the crystalline structure and mineralogical phases, and Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area analysis (NOVATouch, Anton Paar, Germany) was conducted to determine surface area, pore size, and pore volume. Thermal stability was assessed using Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA; Pyris 1, PerkinElmer, USA).

Result and discussion

Zeolite characterization

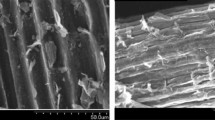

SEM analysis (Fig. 1) showed that the natural zeolite possesses a rough and irregular surface morphology characterized by heterogeneous pores and cavities, which contribute to an increased effective surface area for MB adsorption27. Additionally, the presence of spherical particles on the zeolite surface suggests a high silica content, which further enhances adsorption performance by improving surface area and accessibility to active sites. These observations are in agreement with previous studies6,7.

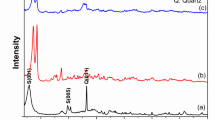

The FTIR spectrum of the zeolite (Fig. 2a) displayed a prominent band at 1025 cm⁻¹, attributed to the stretching vibration of Si–O–Si8. Additional bands at 1643 cm⁻¹ and 1447 cm⁻¹ correspond to the vibration of O–H deformation of adsorbed water and Si–O–Al stretching, respectively, confirming the presence of aluminosilicate linkages. The presence of hydroxyl groups and aluminosilicate linkages suggests potential active sites for cation exchange and electrostatic interactions, which play a key role in MB adsorption28. A peak at 875 cm⁻¹ was assigned to Si–O–Si bridging vibrations within the zeolite framework, further confirming the integrity of the tetrahedral framework. These findings confirm the typical structural features of natural zeolite and are in agreement with previous studies8.

The thermal stability of zeolite was evaluated using TGA analysis (Fig. 2b), which indicates a two-stage weight loss process. The first stage, occurring between 25 °C and 410 °C, showed an approximately 14% weight loss, attributed to the evaporation of physically adsorbed water and loosely bound water molecules7,29. The second stage, observed within the temperature range of 410 °C to 800 °C, accounts for an additional 4.3% weight loss, resulting from the decomposition of hydroxyl groups and the elimination of isolated OH species30. The relatively low mass loss in the second stage indicates good thermal stability, supporting the material’s suitability for regeneration and reuse in adsorption applications.

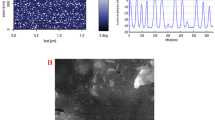

The XRD analysis (Fig. 3) confirmed that natural zeolite possesses a crystalline structure, as evidenced by sharp diffraction peaks corresponding to clinoptilolite as the predominant phase, with minor amounts of mordenite and heulandite. The most intense reflections appear at 2θ ≈ 9.8°, 22.4°, and 26.0°, corresponding to the characteristic diffraction planes of clinoptilolite. Additional peaks at approximately 13.2°, 17.4°, 28–30°, and 45–46° further confirm the presence of the zeolite framework. A peak near 26.6° may indicate minor quartz impurities commonly associated with natural deposits31. Overall, the diffraction pattern demonstrates a well-defined aluminosilicate structure with clinoptilolite as the dominant phase. These findings align with previously reported mineralogical compositions for natural zeolites29,32. The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms (Fig. 4) exhibited a Type IV profile with closed hysteresis loops, indicating mesoporosity with some microporous features14,33. Mesopores enhance dye diffusion and access to active sites, improving adsorption efficiency. However, BET surface area and pore volume were relatively low, typical for raw zeolites with mineral impurities and blocked pores, as reported for unmodified clinoptilolite34. MB adsorption is mainly driven by cation exchange and electrostatic interactions rather than surface area, making isotherm and hysteresis analysis more reliable for assessing mesoporosity and adsorption performance35.

Collectively, the SEM, FTIR, TGA, XRD, and N₂ isotherm results confirm that the natural zeolite possesses a well-defined porous aluminosilicate framework, high thermal stability, and a mesopores texture, all of which make it an excellent candidate for methylene blue adsorption from aqueous solutions.

Adsorption evaluation

Effect of pH

The effect of pH on the adsorption of MB onto zeolite plays a significant role in both the surface charge of the zeolite and the ionization state of MB, thereby influencing adsorption efficiency. Adsorption experiments were conducted at various pH values (3–11) using 0.1 M HCl or 0.1 M NaOH for adjustment. In each experiment, 0.05 g of zeolite was immersed in 25 mL of MB solution with an initial concentration of 10 mg/L. As shown in Fig. 5a, pH did not have a significant effect on MB removal by natural zeolite. The maximum removal efficiency (99.38%) was achieved at pH = 2. When the pH increased from 3 to 11, the removal efficiency remained nearly constant. This suggests that the removal process is not strongly dependent on the protonation state of the zeolite surface.

Zeta potential measurements (Fig. 5b) show that the zeolite surface remains negatively charged across the entire pH range (2.5–11.4), with values varying from about − 10 mV at pH 2 to − 20 mV near pH 6, then becoming slightly less negative at higher pH. This indicates that the point of zero charge (pHpzc) of the zeolite is below 2.5, which contrasts with some literature reports where natural zeolite typically exhibits pHpzc values around 6–736. Such variation can be attributed to differences in zeolite type, origin, and surface modification. Because the surface is negatively charged at all tested pH values, strong electrostatic attraction between MB⁺ and the aluminosilicate framework occurs throughout the pH range, explaining the consistently high removal efficiency (> 99%) from pH 3 to 11. The slight increase in negative charge near pH 6 does not significantly enhance adsorption because the active sites are already saturated. However, the lack of strong pH dependence suggests that adsorption is not governed solely by electrostatic interactions; mechanisms such as cation exchange and π–π interactions likely contribute to the robust performance observed37,38. Incorporating pHpzc analysis provides a clearer interpretation of pH-dependent adsorption behavior and aligns with recent recommendations emphasizing the correlation between surface charge and adsorption efficiency39,40,41.

The pH effect can also be explained using the speciation diagram of MB reported in previous studies42. MB exists as cationic species (MB⁺) or undissociated molecules (MB⁰). At pH > 6.0, MB⁺ dominates, while at pH < 3.0, MB⁰ prevails42. At higher pH (> 5.0), zeolite surfaces become negatively charged, enhancing MB⁺ adsorption via electrostatic attraction. Similar pH effects on cationic dye sorption have been reported42,43 Salazar et al.42 also found MB adsorption on sawdust at pH > pHpzc even with neutral surface charge, suggesting other mechanisms beyond electrostatic forces.

Effect of adsorbent dosage

The influence of the adsorbent dose determines the optimum amount of zeolite needed for effective MB removal. In order to find the ideal dose of zeolite, various amounts (0.01, 0.04, 0.08, 0.12, 0.18 g) were added to 25 mL of 10 mg/L MB at pH = 7. As illustrated in Fig. 6a, the highest removal efficiency of 99.50% was attained at an adsorbent dosage of 0.01 g of natural zeolite. Increasing the adsorbent quantity to 0.05 g resulted in a marginal enhancement, with the efficiency rising to 99.95%. This suggests that the removal efficiency remains relatively constant with further increases in adsorbent dosage13,15. This behavior is attributed to saturation caused by the occupation of active sites and the equilibrium established with the liquid phase. These results suggest that a relatively low zeolite dosage is sufficient to achieve nearly complete MB removal, making the process both cost-effective and efficient.

Effect of contact time

Determining the equilibrium contact time is necessary for the maximum removal of MB while minimizing energy and operational costs. The effect of contact time on the adsorption process was studied by adding 0.01 g of zeolite to 25 mL of 10 mg/L MB solution, and the mixtures were shaken at intervals of 1, 5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min, as illustrated in Fig. 6b. The results showed that MB removal efficiency increased with contact time due to the availability of active sites on the natural zeolite surface. The high initial adsorption does not occur exclusively on the external surface; rapid uptake within seconds is driven by electrostatic interactions and ion exchange, followed by intraparticle diffusion into mesopores until equilibrium is reached. This multi-step mechanism, involving fast surface adsorption and slower internal diffusion, has been widely reported for MB on zeolite44. Approximately 51% of MB was removed within 5 min, demonstrating the rapid adsorption capability of the natural zeolite adsorbent. As the contact time extended to 30 min, the removal efficiency increased, reaching a maximum of 98.40%, after which no significant enhancement occurred due to saturation of active sites16,17. Therefore, 30 min was identified as the optimal equilibrium time for further experiments.

Effect of initial MB concentration and temperature

The impact of initial MB dye concentrations and solution temperature on the adsorption behavior of MB dye using natural zeolite was studied over a concentration range of 2–120 mg/L at different temperatures (25, 35, and 40 °C) under fixed experimental conditions (time = 30 min, pH = 7, and adsorbent dose = 0.01 g), as illustrated in Fig. 6c. The findings indicated that the adsorption capacity of MB increased from 2.26 to 112.5 mg/g as the MB concentration rose from 2.0 to 120 mg/L at 25 °C. This enhancement in adsorption capacity at higher MB concentrations is attributed to the greater driving force for mass transfer from the solution to the natural zeolite surface, which facilitates greater interaction between dye molecules and the zeolite surface17. The effect of varying temperatures (25, 35, and 40 °C) on the adsorption efficiency of MB is also depicted in Fig. 6c. As the temperature increased from 25 to 40 °C, the adsorption capacity of MB dye decreased from 33.85 to 21.43 mg/g at an initial MB concentration of 15 mg/L. These observations indicate that the adsorption process is exothermic17,45,46,47. Comparable findings have been reported, showing similar trends in MB adsorption using zeolites derived from rice husk ash and kaolinite clay48,49.

Adsorption isotherms

To describe the adsorption behavior of MB dye on natural zeolite, two widely used isotherm models, namely, Langmuir (Eq. 4) and Freundlich (Eq. 5), were used. The experimental data and the fitted curves of the nonlinear isotherm models are presented in Table 1; Fig. 7a–c.

where Ce is the equilibrium concentration of MB dye (mg/L), KL denotes the Langmuir constant. The maximum adsorption capacity is given in mg/g. Additionally, KF and n are the Freundlich isotherm constants and adsorption intensity, respectively.

The nonlinear Langmuir model, which describes monolayer adsorption on a uniform surface, exhibited a good fit to the data with an R² value of 0.99307, indicating that the adsorption process of MB dye occurred on the homogeneous surfaces of the natural zeolite at 25 °C, with a maximum monolayer adsorption capacity (qm) of 116.34 mg/g, which is significantly higher than values reported for other zeolites such as NaY (49 mg/g)29, Na-P1 (35.33 mg/g)50, and ZnO–Zeolite composites (41.32 mg/g)51, highlighting the strong affinity of MB for natural zeolite.

The separation factor (RL) values (0.33–0.64) for different initial concentrations were within the range of 0–1, confirming the favorability of the adsorption process. Furthermore, the decrease in KL and KF values with increasing temperature indicates an exothermic nature of the adsorption process, which aligns with previous studies on MB adsorption onto zeolitic materials. This suggests that lower temperatures favor MB uptake, an important consideration for practical applications52.

Although the Freundlich model also provided a reasonable fit (R² ≈ 0.955–0.967), its empirical nature and n values (> 1) indicate favorable adsorption but suggest surface heterogeneity. This implies that while most adsorption occurs on uniform sites, as assumed by the Langmuir model, some heterogeneity exists due to mineral impurities and structural variations in natural zeolite12. Overall, the strong agreement with the Langmuir model, high qm values, and favorable RL factors confirm that MB adsorption on natural zeolite is predominantly a monolayer process governed by electrostatic interactions and ion exchange. These findings are consistent with previous reports on MB adsorption onto natural and modified zeolites12.

Other isotherm models, such as Temkin and Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R), were not considered in this study because the adsorption data exhibited a strong fit to the Langmuir and Freundlich models, which are widely accepted for describing MB adsorption on zeolitic materials. The Temkin model assumes a linear decrease in adsorption heat with coverage, which is more relevant for chemisorption-dominated systems, whereas the D–R model is typically applied to distinguish between physical and chemical adsorption based on mean free energy. Since the experimental results indicated predominantly monolayer adsorption with high correlation to Langmuir (R² = 0.99307) and favorable Freundlich parameters (n > 1), additional models were deemed unnecessary for accurate interpretation. Furthermore, previous studies on MB adsorption onto natural zeolite have also reported Langmuir and Freundlich as the most representative models for similar systems15,53.

Adsorption kinetics

To investigate the adsorption mechanism of MB dye onto natural zeolite, two widely used kinetic models, namely, pseudo-first-order (PFO) (Eq. 6) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) (Eq. 7), were used. The results for these models are illustrated in Fig. 7d and summarized in Table 2.

where qt and qe (mg/g) represent the adsorption capacity at time (min) and at equilibrium, respectively. The rate constants for the PFO and PSO models are denoted as k1 (min− 1) and k2) g mg− 1 min− 1), respectively. The most suitable kinetic model was determined by considering the highest R² value. The PSO model exhibited higher R² (R² = 0.96283) and provided a better fit compared to the PFO model (R² = 0.93155) (Table 2). Based on these findings, the PSO model proved to be the most appropriate for describing MB adsorption onto natural zeolite. This observation was further supported by the close match between the experimental qe,exp (24.71 mg/g) and calculated (qe,cal = 24.12 mg/g) values, indicating that the mechanism involved in MB dye adsorption on natural zeolite is chemisorption. Chemisorption involves valence forces through sharing or exchange of electrons between MB molecules and active sites on the zeolite surface, which aligns with the strong electrostatic interactions and ion-exchange properties of zeolite.

Additional interactions such as π–π stacking between the aromatic structure of MB and electron-rich surface species, along with hydrogen bonding involving surface hydroxyl groups (Si–OH, Al–OH), further enhance adsorption affinity. The presence of mesopores in natural zeolite also supports gradual intraparticle diffusion, explaining the slower adsorption phase after the initial rapid removal. These combined mechanisms have been widely documented in previous studies on MB adsorption onto zeolitic materials, reinforcing the interpretation that MB uptake involves electrostatic interactions, ion exchange, and auxiliary molecular interactions rather than a single dominant pathway12,52,53. Comparable kinetic behavior has been reported for MB adsorption on other zeolitic materials, including 3D-printed natural zeolite and fly ash-derived zeolite, confirming the applicability of the PSO model for systems dominated by chemical interactions rather than simple physical adsorption6,7.

Adsorption thermodynamics

Thermodynamic parameters (ΔG°, ΔH°, ΔS°) were evaluated to understand the effect of temperature on MB adsorption onto natural zeolite (Fig. 8; Table 3). These parameters were calculated using the following equations:

where R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K), T is the absolute temperature (K), and Kc is the equilibrium constant obtained from adsorption data. The slope and intercept of the plot of ln Kc versus 1/T (Fig. 8) were used to determine ΔH° and ΔS°, respectively.

The negative ΔG° values (− 24.85 to − 23.56 kJ/mol) confirm that adsorption is spontaneous and more favorable at lower temperatures. The negative ΔH° (− 44.08 kJ/mol) indicates an exothermic process, which is consistent with reduced adsorption at higher temperatures because increased thermal energy weakens electrostatic interactions and disrupts ion-exchange mechanisms. The positive ΔS° (64.65 J/mol·K) suggests increased randomness at the solid–solution interface during adsorption, likely due to the release of water molecules from zeolite pores and MB hydration shells. This entropy gain offsets energy changes, supporting spontaneity despite temperature variation.

Physically, the exothermic nature of adsorption can be attributed to strong electrostatic attraction between MB⁺ and negatively charged aluminosilicate sites, as well as cation exchange processes. At higher temperatures, these interactions weaken, reducing adsorption capacity. These findings align with previous studies reporting spontaneous and exothermic MB adsorption on zeolite, with entropy changes attributed to structural rearrangements and desolvation effects44,53,54.

Desorption of MB

Over time, natural zeolite becomes saturated with adsorbed MB molecules, leading to a decrease in adsorption efficiency. This highlights the need for, and the importance of, zeolite recycling and regeneration to maintain cost-effectiveness, sustainability, and adsorption efficiency over multiple cycles. After performing adsorption experiments, 0.01 g of zeolite was separated from the solution by filtration and washed with distilled water to remove dye molecules. The zeolite was then treated with 0.1 M HCl, 0.1 M NaOH, and acetone to assess their effectiveness in desorbing the dye and restoring active sites of the zeolite. The effectiveness of HCl (0.1 M), NaOH (0.1 M), and acetone in regenerating zeolite over four cycles is illustrated in Fig. 9. The results of desorption efficiency using NaOH, HCl, and acetone were 93.63%, 85.42%, and 73.93%, respectively, indicating that the best eluent for MB dye is NaOH solution. After four adsorption–desorption cycles, the MB removal efficiency decreased to 86.53%. The decrease in removal efficiency of MB dye could be attributed to the partial loss of adsorbent during the adsorption process. These findings are consistent with previous studies on MB desorption from ZnO–Zeolite composite using 0.1 M NaOH51. Overall, the results demonstrate that natural zeolite can be effectively regenerated and reused, maintaining high adsorption performance over multiple cycles. However, MB desorption depends on the regenerating agent. NaOH creates a negatively charged zeolite surface, causing strong electrostatic repulsion with cationic MB and enabling efficient desorption. HCl protonates surface sites, reducing MB affinity but without strong repulsion, giving moderate efficiency. Acetone disrupts weak interactions but cannot overcome electrostatic forces, resulting in the lowest performance55.

Before reuse, natural zeolite typically exhibits a crystalline structure with open pores, as indicated by XRD and BET analysis. After four regeneration cycles, minor surface roughness and partial pore blockage may occur, particularly with HCl and acetone treatments, while NaOH better preserves structural integrity. Future work should confirm these changes using SEM or BET characterization.

Table 4 presents a comparative evaluation of MB adsorption capacities (qmax) for various zeolite-based adsorbents, including the material developed in this study. The results show a wide range of adsorption capacities, reflecting differences in adsorbent composition, structure, and synthesis methods. The adsorbent developed in this study achieved the highest MB adsorption capacity among zeolite-based materials, reaching 24.71 mg/g, which exceeds previously reported values for natural and modified zeolites (typically 1.5–23.97 mg/g)56,57,58,59,60,61. This improvement highlights the effectiveness of the material design and preparation method, likely due to enhanced surface area, pore accessibility, and the density of active adsorption sites. However, when benchmarked against activated carbon, which commonly exhibits MB adsorption capacities ~ 300 mg/g62,63, the performance of zeolite remains significantly lower. Despite limitations, zeolites offer key advantages for wastewater treatment: they are low cost due to natural abundance, environmentally sustainable with minimal processing energy, and reusable thanks to structural stability and regeneration capability. Their multifunctionality, such as ion exchange for heavy metals and ammonium, supports integrated treatment systems. While activated carbon remains superior in adsorption capacity, zeolite-based adsorbents provide a sustainable and cost-effective alternative for large-scale applications where resource availability and operational costs are critical.

Natural zeolite exhibited a low capacity (1.50 mg/g), influenced by intrinsic factors such as geological origin, mineralogical composition, and surface area56. Sodalite octahydrate showed moderate performance (3.50 mg/g), likely due to limited porosity57, while ZSM-5 zeolite recorded 4.31 mg/g, constrained by its microporous structure58. Chinese natural zeolite achieved 5.15 mg/g, indicating moderate surface activity59. In contrast, fly ash-derived zeolite (12.64 mg/g)60 and Turkish natural zeolite (23.97 mg/g)61 demonstrated higher capacities, attributed to modified surface chemistry and improved mesoporosity. Overall, these findings confirm that engineered zeolite offers superior MB removal and underscore the importance of material design and synthesis in optimizing adsorption performance.

Conclusions

This study highlights the potential of natural zeolite as an efficient, sustainable, and cost-effective adsorbent for MB removal from aqueous solutions. Achieving a removal efficiency of 98.9% under optimized conditions, natural zeolite demonstrates strong adsorption performance supported by structural and chemical stability confirmed through SEM, FTIR, XRD, and TGA analyses. The adsorption process follows the Langmuir isotherm and pseudo-second-order kinetic models, indicating monolayer adsorption with a high maximum capacity of 116.34 mg/g. Thermodynamic analysis confirms the process is spontaneous and exothermic, while regeneration studies reveal excellent reusability, reinforcing its economic and environmental viability. These attributes position natural zeolite as a promising solution for large-scale wastewater treatment, offering a green alternative for industries seeking sustainable water management strategies. Future research should prioritize pilot-scale implementation and real industrial wastewater testing to validate long-term performance and support widespread adoption in sustainable water management.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lin, J. et al. Environmental impacts and remediation of dye-containing wastewater. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 785–803. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-023-00489-8 (2023).

Tripathi, M. et al. Recent strategies for the remediation of textile dyes from wastewater: a systematic review. Toxics 11, 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics11110940 (2023).

Khan, I. et al. Review on methylene blue: its properties, uses, toxicity and photodegradation. Water 14, 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14020242 (2022).

Naushad, M., Sharma, G. & Alothman, Z. A. Photodegradation of toxic dye using gum Arabic-crosslinked-poly (acrylamide)/Ni (OH) 2/FeOOH nanocomposites hydrogel. J. Clean. Prod. 241, 118263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118263 (2019).

Kenawy, R. et al. Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide intercalated and branched polyhydroxystyrene functionalized montmorillonite clay to sequester cationic dyes. J. Environ. Manage. 219, 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.04.121 (2018).

Rakanović, M. et al. Zeolites as adsorbents and photocatalysts for removal of dyes from the aqueous environment. Molecules 27, 6582. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27196582 (2022).

Shindhal, T. et al. A critical review on advances in the practices and perspectives for the treatment of dye industry wastewater. Bioengineered 12, 70–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/21655979.2020.1863034 (2021).

Oladoye, P. O., Ajiboye, T. O., Omotola, E. O. & Oyewola, O. J. Methylene blue dye: toxicity and potential elimination technology from wastewater. Results Eng. 16, 100678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2022.100678 (2022).

Katheresan, V., Kansedo, J. & Lau, S. Y. Efficiency of various recent wastewater dye removal methods: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 6, 4676–4697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2018.06.060 (2018).

Agarwala, R. & Mulky, L. Adsorption of dyes from wastewater: A comprehensive review. ChemBioEng Rev. 10, 326–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2018.06.060 (2023).

Haleem, A., Shafiq, A., Chen, S. Q. & Nazar, M. A comprehensive review on adsorption, photocatalytic and chemical degradation of dyes and nitro-compounds over different kinds of porous and composite materials. Molecules 28, 1081. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28031081 (2023).

Dehmani, Y. et al. Adsorption of various inorganic and organic pollutants by natural and synthetic zeolites: A critical review. Arab. J. Chem. 17, 105474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105474 (2024).

Dosa, M., Grifasi, N., Galletti, C., Fino, D. & Piumetti, M. Natural zeolite clinoptilolite application in wastewater treatment: methylene blue, zinc and cadmium abatement tests and kinetic studies. Materials 15, 8191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15228191 (2022).

de Magalhães, L. F., da Silva, G. R. & Peres, A. E. C. Zeolite application in wastewater treatment. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2022, 4544104. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4544104 (2022).

Turp, S. M., Turp, G. A., Ekinci, N. & Özdemir, S. Enhanced adsorption of methylene blue from textile wastewater by using natural and artificial zeolite. Water Sci. Technol. 82, 513–523. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2020.358 (2020).

Alabbad, E. A. Efficacy assessment of natural zeolite containing wastewater on the adsorption behaviour of direct yellow 50 from; equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamic studies. Arab. J. Chem. 14, 103041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103041 (2021).

Imessaoudene, A. et al. Adsorption performance of zeolite for the removal of congo red dye: factorial design experiments, kinetic, and equilibrium studies. Separations 10, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations10010057 (2023).

Kaci, M. M., Akkari, I., Pazos, M., Atmani, F. & Akkari, H. Recent trends in remediating basic red 46 dye as a persistent pollutant from water bodies using promising adsorbents: a review. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy. 27, 773–788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-024-03026-3 (2025).

Atmani, F. A. et al. Adsorption ability of sugar scum as industrial waste for crystal Violet elimination: experimental and advanced statistical physics modeling. Surf. Interfaces. 54, 105166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2024.105166 (2024).

Ait Merzeg, F. et al. Phenol adsorption onto Olive pomace activated carbon: modelling and optimization. Natsional’nyi Hirnychyi Universytet Naukovyi Visnyk. 2, 125–133. https://doi.org/10.33271/nvngu/2023-2/125 (2023).

Yarik, S. et al. Adsorption of methylene blue by lemon verbena leaf waste: valorization, decontamination and modeling. Environ. Monit. Assess. 197, 768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-025-14223-y (2025).

Amelia, S. & Maryudi, M. Application of natural zeolite in methylene blue wastewater treatment process by adsorption method. Jurnal Bahan Alam Terbarukan. 8, 144–147. https://doi.org/10.15294/jbat.v8i2.22480 (2019).

Nugroho, M. G. et al. Environmentally friendly bifunctional materials based on zno/natural zeolite for methylene blue dye removal in water. Jurnal Kimia Riset. 9, 210–224. https://doi.org/10.20473/jkr.v9i2.65751 (2024).

Alhogbi, B. G. & Al Balawi, G. S. An investigation of a natural biosorbent for removing methylene blue dye from aqueous solution. Molecules 28, 2785. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28062785 (2023).

Abd Elmaksod, I., Kosa, S. A., Alzahrani, H. & Hegazy, E. Z. Simultaneous photodegradation and removal of organic-inorganic pollutants over zeolite prepared from Saudi Arabia Kaolin. Egypt. J. Chem. 62, 2119–2129. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejchem.2019.12026.1758 (2019).

Nizami, A. S. et al. The potential of Saudi Arabian natural zeolites in energy recovery technologies. Energy 108, 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2015.07.030 (2016).

Yardımcı, B. & Kanmaz, N. An effective-green strategy of methylene blue adsorption: sustainable and low-cost waste cinnamon bark biomass enhanced via MnO2. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 110254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.110254 (2023).

Haag, W. O., Lago, R. M. & Weisz, P. B. The active site of acidic aluminosilicate catalysts. Nature 309, 589–591. https://doi.org/10.1038/309589a0 (1984).

Iqbal, M. J. & Ashiq, M. N. Adsorption of dyes from aqueous solutions on activated charcoal. J. Hazard. Mater. 139, 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.06.007 (2007).

El Messaoudi, N. et al. Regeneration and reusability of non-conventional low-cost adsorbents to remove dyes from wastewaters in multiple consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles: a review. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14, 11739–11756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-022-03604-9 (2024).

Deng, L., Xu, Q. & Wu, H. Synthesis of zeolite-like material by hydrothermal and fusion methods using municipal solid waste fly Ash. Procedia Environ. Sci. 31, 662–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2016.02.122 (2016).

Adeyemo, A. A., Adeoye, I. O. & Bello, O. S. Adsorption of dyes using different types of clay: a review. Appl. Water Sci. 7, 543–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-015-0322-y (2017).

Dehghani, M. H. et al. Removal of methylene blue dye from aqueous solutions by a new chitosan/zeolite composite from shrimp waste: kinetic and equilibrium study. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 34, 1699–1707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11814-017-0077-2 (2017).

Grifasi, N., Ziantoni, B., Fino, D. & Piumetti, M. Fundamental properties and sustainable applications of the natural zeolite clinoptilolite. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-33656-5 (2024).

Wang, S. & Peng, Y. Natural zeolites as effective adsorbents in water and wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 156, 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2009.10.029 (2010).

Kragović, M. M., Dakovic, A. S., Milićević, S. Z., Sekulic, Z. T. & Milonjić, S. K. Influence of organic cations sorption on the point of zero charge of natural zeolite. Hemijska Industrija. 63, 325–330. https://doi.org/10.2298/HEMIND0904325K (2009).

Koçak, F. Z., Yakut, ŞM. & Küçükdeveci, N. Natural zeolite doped hydroxyapatite nanoceramics as adsorbents for removal of methylene blue dye. J. Aust Ceram. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41779-025-01291-z (2025).

Bensaid, N. et al. A mechanistic approach to methylene blue adsorption by synthesized and commercial H-beta zeolite. ChemistrySelect 10, e01112. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202501112 (2025).

Neusatz Guilhen, S. et al. Role of point of zero charge in the adsorption of cationic textile dye on standard biochars from aqueous solutions: selection criteria and performance assessment. Recent. Progress Mater. 4, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.21926/rpm.2202010 (2022).

Moheb, M., El-Wakil, A. M. & Awad, F. S. Highly porous activated carbon derived from the Papaya plant (stems and leaves) for superior adsorption of Alizarin red s and methylene blue dyes from wastewater. RSC Adv. 15, 674–687. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4RA07957D (2025).

Mülazımoğlu, E., Yardımcı, B. & Kanmaz, N. Cross-linked Chitosan and iron-based metal-organic framework decoration on waste cellulosic biomass for pharmaceutical pollutant removal. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 196, 106948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2025.106948 (2025).

Salazar-Rabago, J. J., Leyva-Ramos, R., Rivera-Utrilla, J., Ocampo-Perez, R. & Cerino-Cordova, F. J. Biosorption mechanism of methylene blue from aqueous solution onto white pine (Pinus durangensis) sawdust: effect of operating conditions. Sustainable Environ. Res. 27, 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.serj.2016.11.009 (2017).

Pathania, D., Sharma, S. & Singh, P. Removal of methylene blue by adsorption onto activated carbon developed from ficus carica Bast. Arab. J. Chem. 10, 1445–S1451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.04.021 (2017).

Gonçalves dos Santos, M., Paquini, D., Leite Quintela, L., Profeti, P. H. R., Guimarães, D. & L. P., & Insights into kinetics and thermodynamics for adsorption methylene blue using ecofriendly zeolites materials. ACS Omega. 10, 20326–20340. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c11718 (2025). https://pubs.acs.org

AlGburi, H. R., Aziz, H. A., Zwain, H. M. & Noor, A. F. M. Treatment of landfill leachate by heterogeneous catalytic ozonation with granular Faujasite zeolite. Environ. Eng. Sci. 38, 635–644. https://doi.org/10.1089/ees.2020.0233 (2021).

Shirendev, N. et al. A natural zeolite developed with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane and adsorption of Cu (II) from aqueous media. Appl. Sci. 12, 11344. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122211344 (2022).

Wang, Z., Zhang, J., Wang, H. & Han, R. Adsorption of naphthol green B on CPC modified zeolite from solution and secondary adsorption toward methylene blue. Desalin. Water Treat. 244, 325–342. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2021.27941 (2021).

Naikoo, R. A. et al. Polypyrrole and its composites with various cation exchanged forms of zeolite X and their role in sensitive detection of carbon monoxide. RSC Adv. 6, 99202–99210. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RA19708F (2016).

Hayfron, J., Jääskeläinen, S. & Tetteh, S. Synthesis of zeolite from rice husk Ash and kaolinite clay for the removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution. Heliyon 11, e41325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e41325 (2025).

Minceva, M., Fajgar, R., Markovska, L. & Meshko, V. Comparative study of Zn2+, Cd2+, and Pb2 + removal from water solution using natural clinoptilolitic zeolite and commercial granulated activated carbon. Equilibrium of adsorption. Sep. Sci. Tech. 43, 2117–2143. https://doi.org/10.1080/01496390801941174 (2008).

Mansouri, N., Rikhtegar, N., Panahi, H. A., Atabi, F. & Shahraki, B. K. Porosity, characterization and structural properties of natural zeolite-clinoptilolite-as a sorbent. Environ. Prot. Eng. 39, 139–152. https://doi.org/10.5277/EPE130111 (2013).

Hasani, N. et al. Theoretical, Equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamic investigations of methylene blue adsorption onto lignite coal. Molecules 27, 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27061856 (2022).

Aya, H. H., Djamel, N., Samira, A., Otero, M. & Khan, M. A. Optimizing methylene blue adsorption conditions on hydrothermally synthesized NaX zeolite through a full two-level factorial design. RSC adv. 14, 23816–23827. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4RA04483E (2024).

Abbas, M. Removal of methylene blue pollutant from the textile industry by adsorption onto zeolithe: kinetic and thermodynamic study. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 17, 1558925021993692. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558925021993692 (2022).

Coşkun, Y. İ. Investigation of adsorption performances of green walnut hulls for the removal of methylene blue. Desalin. Water Treat. 247, 281–293. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2022.28075 (2022).

Amin, G., Đorđević, D., Konstantinović, S. & Jordanov, I. The removal of the textile basic dye from the water solution by using natural zeolite. Adv. Technol. 6, 67–71. https://doi.org/10.5937/savteh1702067A (2017).

Asefa, M.,, T., Feyisa,, G. &, B. Comparative investigation on two synthesizing methods of zeolites for removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2022 (9378712). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9378712 (2022).

Radoor, S., Karayil, J., Jayakumar, A., Parameswaranpillai, J. & Siengchin, S. Removal of methylene blue dye from aqueous solution using PDADMAC modified ZSM-5 zeolite as a novel adsorbent. J. Polym. Environ. 29, 3185–3198. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-211769/v1 (2021).

Han, R. et al. Study of equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic parameters about methylene blue adsorption onto natural zeolite. Chem. Eng. J. 145, 496–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2008.05.003 (2009).

Woolard, C., Strong, J. & Erasmus, C. Evaluation of the use of modified coal Ash as a potential sorbent for organic waste streams. Appl. Geochem. 17, 1159–1164. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-2927(02)00057-4 (2002).

Alpat, S. K., Özbayrak, Ö., Alpat, Ş. & Akçay, H. The adsorption kinetics and removal of cationic dye, toluidine blue O, from aqueous solution with Turkish zeolite. J. Hazard. Mater. 151, 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.05.071 (2008).

Ibrahim, M., Souleiman, M. & Salloum, A. Methylene blue dye adsorption onto activated carbon developed from calicotome villosa via H3PO4 activation. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 13, 12763–12776. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1RA04672A (2023).

Thang, N. H., Khang, D. S., Hai, T. D., Nga, D. T. & Tuan, P. D. Methylene blue adsorption mechanism of activated carbon synthesised from cashew nut shells. RSC adv. 11, 26563–26570. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1RA04672A (2021).

Acknowledgements

The research team gratefully acknowledges the support of King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST) for providing the laboratory facilities and essential resources for this study. We also extend our sincere appreciation to the technical staff for their invaluable assistance with laboratory analyses.

Funding

This work was funded by KACST.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Alsuhybani: Conceptualization, visualization, supervision, characterization, writing—review and editing; S. Alshehri: Methodology, data curation, writing—original draft preparation; A. Alrehaili: Characterization, writing—review and editing. Alquwaizany: Writing—review and editing; E. Alosime: Writing—review and editing; R. Alaeq: Writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alsuhybani, M., Alshehri, S., Alquwaizany, A. et al. Effective adsorption of methylene blue using natural Saudi zeolite as a low-cost sustainable adsorbent. Sci Rep 16, 211 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33491-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33491-9