Abstract

Tuta absoluta is a significant invasive pest, severely impacting the global tomato industry. Prolonged application of chemical insecticides has led to varying degrees of resistance in T. absoluta populations. Additionally, chemical insecticides are causing serious threats to the environment. Aiming to develop a novel bioinsecticide based on Origanum vulgare essential oil (OVE) against T. absoluta, we carried out its nanostructured lipid carrier formulation (OVE-NLC). The obtained OVE-NLC had spherical particles approximately 94.26 nm in size with a uniform size distribution of less than 0.3 and a zeta potential of − 18.75 mV. The formulated NLC also had encapsulation efficiency up to 96% and was stable at 25 °C for 3 months. The FTIR results indicated no significant chemical interaction between EO and NLC components. OVE-NLC demonstrated significant toxicity towards T. absoluta larvae and a remarkable oviposition deterrence for females. The nanoformulation also negatively affected the population growth parameters of T. absoluta, significantly reducing its fecundity by approximately 70% and 42% in contact and topical assays, respectively. Additionally, OVE-NLC had no lethal effects on the generalist predator Macrolophus pygmaeus and pollinator bee Bombus terrestris as non-target organisms. Results suggested that OVE-NLC could be successfully used as a potential tool for tomato integrated pest management programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tomato, Solanum lycopersicum L., is the second most produced and consumed vegetable species worldwide, following the potato. This vegetable contains mainly health-promoting nutrients for the human diet. The global production rate of tomatoes has been constantly growing for over five decades. In 2023, the yearly worldwide tomato production on five million hectares totaled 190 million tons1,2. Although tomato production is typically performed in open fields, its cultivation in greenhouses is growing. In greenhouses, pollination does not occur naturally, and cultured bumblebees and artificial and hormonal pollination assist this process3. Bombus terrestris L. (Hymenoptera: Apidae) is one of the most commercially reared species used for crop pollination worldwide. This species has easier breeding and can form larger colonies than other bumblebees. Although there is a high demand for the use of B. terrestris, the extensive use of insecticides may negatively affect its growth and pollination activity4.

Many pests, including insects, acari, fungi, and bacteria, attack tomatoes in greenhouse and open-field production. The tomato leaf miner, Tuta absoluta Meyrick (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae), is the most serious insect pest of solanaceous plants with a preference for tomato. Larvae mine and feed on leaves and all parts of host plants, resulting in a considerable reduction of up to 100% in all tomato production systems1,5,6. Integrated management strategies against T. absoluta aim to keep damage to tomatoes below the economic threshold. Biological control is a key component of such programs7. Biological control of T. absoluta is mostly addressed using omnivorous predatory mirids. Macrolophus pygmaeus Rambur, 1839 (Hemiptera: Miridae) is a main biocontrol agent against T. absoluta, whiteflies, aphids, spider mites, and thrips8,9 that successfully mass-rear for commercial purposes. However, it should be noted that biological control agents are not fast-acting, and using them as a single strategy is often more costly than other pest control techniques10.

While the application of synthetic insecticides seems to be the most commonly used strategy against this invasive pest worldwide, this form of control is unsustainable and causes potential environmental and human health concerns1. Moreover, chemical insecticides cause unwanted side effects on the beneficial species, including predators and parasitoids11,12. Therefore, novel eco-friendly alternatives for controlling T. absoluta are urgently needed. In this regard, botanical insecticides generally receive considerable attention as safe products, and their use plays a crucial role in integrated pest management (IPM) programs13.

Among botanical insecticides, plant essential oils (EOs) represent an interesting challenge for the development of new bio-insecticides. These biodegradable compounds have low human and mammalian toxicity, exert their action via multiple target sites, and affect the physiological, biochemical, and metabolic processes of insects14. Origanum vulgare L. (family Lamiaceae), also called oregano, has a widespread distribution and high ecological adaptability across diverse geographical regions15. The published literature indicates that its EO possesses a wide range of antifungal, antiviral, antibacterial, antioxidant, and insecticidal activities16. However, some intrinsic properties of EOs, such as high volatility, poor solubility in water, oxidation sensitivity, and phytotoxicity, make their use and development problematic under real operating conditions14. Encapsulation of EOs in nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) can solve these problems and represent a new and sustainable alternative to chemical insecticides17. NLCs not only reduce the concentration of EO at which it causes potential efficacy due to their small size and high surface reactive area but also improve the physical and colloidal stability of the formulations and their resistance to ultraviolet light, evaporation, and oxidation18,19.

Considering the above-mentioned advantages of EOs as bio-insecticides and the promising results observed for EO encapsulation in NLCs in different industries, the present study, for the first time, investigates the insecticidal and oviposition deterrent properties of pure O. vulgare EO and its NLC formulation against T. absoluta as well as their side effects on M. pygmaeus and B. terrestris as non-target organisms. While more research is needed, our results will provide an important contribution to optimizing the use of these bio-insecticides within the framework of T. absoluta IPM strategies.

Materials and methods

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines for the use of animals in research. There were no licence or permit requirements for the experiments presented in this paper.

Insect rearing

The population of T. absoluta was established using immature stages collected from untreated tomato fields in West Azarbaijan Province, Urmia, Iran. The pest was reared for several generations in mesh net cages (60 × 30 × 30 cm) containing tomato plants. The cages were maintained in a greenhouse of the Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran, at 28 ± 2 °C, 60 ± 5% relative humidity, and 16:8 h (light: dark) photoperiod.

The original culture of M. pygmaeus was obtained from a mass production company (Farmerz, Lorestan, Iran) and placed in rearing cages containing potted tomato plants and Ephestia kuehniella Zeller (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) eggs, as a reference diet at greenhouse conditions. Additionally, to supplement the diet of predatory mirid bugs, droplets of honey solution (50% in water) were placed on the tomato plant leaflets every week8.

Commercial B. terrestris hives were supplied from a mass production company (Farmerz, Lorestan, Iran) and stored in the dark at 23 ± 2 °C and 65 ± 5% relative humidity. During their stores, 50% sucrose solution was used for each hive. Pollen was supplied as an essential protein source for larval development every 2 days4.

Extraction and chemical characterization of Origanum vulgare essential oil.

All procedures involving plant material were carried out in accordance with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and regulations, including the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The EO was extracted from the aerial parts of O. vulgare collected in the city of Urmia, Iran (37°35ʹ N, 45°05ʹ E). Dr. Mozhgan Larti formally identified the plant material. A voucher specimen of this species (11073) was deposited at the Herbarium of Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization (AREEO), West Azerbaijan, Urmia, Iran. Essential oil was extracted from 500 g of dried gathered specimens in 500 mL of distilled water by hydro-distillation for three hours using a Clevenger-type apparatus. The extracted EO without water was stored at 4 °C ± 1 in airtight dark vials until use.

The chemical composition of O. vulgare EO was determined using a gas chromatography (GC Agilent, 7890 USA) coupled with a capillary column (BP-5 MS, length of 30 m, inner diameter of 0.25 mm, thin-film of 0.25 μm) and a mass selective detector (Agilent 5975 A, USA). The initial oven temperature was kept at 80 °C, for 3 min, then programmed to reach 180 °C at the rate of 8 °C min− 1. The sample was maintained at this temperature for 10 min. Helium, with a flow rate of 1 mL/min, was used as the carrier gas. All mass spectra were recorded in the electron impact ionization at 70 eV and were scanned in the range of 40–500 m/z. The constituents of EO were identified by comparing their mass spectra with those described in the instrument libraries and with published spectra6.

Chemicals

Glycerol distearate (Precirol® ATO5) was obtained from Gattefossé, (Saint-Priest, Cedex, France). Poloxamer® 407 and Caprylic/capric triglyceride (Miglyol® 812) were obtained from Sigma Alderich (Chemie GmbH, Germany) and Sasal, (Hamburg, Germany), respectively. The commercial formulation of indoxacarb (Indoxacarb®, 15% SC) and neem (Neem Azal® 1% EC) positive controls were obtained from Arya Shimi and Zist Bani Paya (Tehran, Iran), respectively.

Origanum vulgare EO-NLC preparation

O. vulgare EO-NLC (OVE-NLC) was made by dissolving 200 mg O. vulgare EO in 200 mg liquid lipid (Miglyol) in a hot water bath and adding it to 1.8 g of melted solid lipid (Precirol). Meanwhile, about 25 mL of aqueous surfactant solution containing 1.5 g of Poloxamer was made separately. It was then added dropwise to the melted lipid phase and homogenized for 15 min at 20,000 rpm using a high-shear homogenizer (Silent Crusher M, Heidolph, Nuremberg, Germany). Following the same stirring rate, the hot formulation was allowed to cool down at room temperature, and OVE-NLC was finally produced. A control formulation without O. vulgare EO (control NLC) was also prepared using the same method20,21.

Origanum vulgare EO-NLC analysis

Characterization and physical stability

The mean diameter size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential of OVE-NLC and control NLC were determined at 24 h after NLC production by dynamic light scattering (DLS) method at 25 °C using a Nano ZetaSizer system (Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK) in three replications. Moreover, the physical stability of these formulations was measured at room temperature (20 ± 5 °C) for 3 months.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

In order to identify the possible interactions that can occur during the synthesis of nanoparticles, the freeze-dried control NLC and OVE-NLC were mixed with potassium bromide (KBr) and pressed with a hydraulic press instrument to prepare pellets. FTIR spectra (Shimadzu, Japan) of samples were measured in the wave number region of 4000–00/cm22.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The morphological analysis was carried out for control NLC and OVE-NLC (shape and surface characteristics) using an SEM (SEM, KYKY-EM3200, Beijing, China). The samples were prepared with deionized water and placed on a slide until dry at room temperature. The dried samples were then coated with a thin layer of gold, and the particle morphology was imaged at 26 kV22.

Encapsulation efficacy

To determine the encapsulation efficiency, 0.5 ml of OVE-NLC was mixed with 3.5 ml of ethanol and stirred for 15 min. Then the sample was transferred to an Amicon ultrafilter tube and centrifuged for 5 min at 5000 rpm. The absorbance of the filtered sample was recorded using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Ultrospec 2000, Scinteck; UK) at λmax = 272 nm. Finally, the encapsulation efficiency percentage (EE %) was calculated by Eq. (1)23.

where C1 is the amount of not encapsulated EO (free EO) (mg) and C2 demonstrates the total EO (mg) added to the nanostructured lipid carrier.

Insecticidal assay

To assess the toxicity of O. vulgare EO and its NLC formulation (OVE-NLC), two distinct experiments were carried out to simulate the field-realistic scenarios.

Topical toxicity

Using a stock solution of 50 mg/mL, five concentrations for each test compound were prepared by serially diluting them in ethanol. For evaluating contact toxicity of compounds, 1 µL of appropriate concentrations (determined from preliminary bioassays to obtain mortality in the range of 20–80%) of OVE and OVE-NLC was applied onto the mesonotum of T. absoluta second instar larvae (one-day-old) using a microsyringe. After application, larvae were individually kept in plastic Petri dishes (6 cm diameter) containing tomato leaflets. The negative control consisted of a control NLC formulation and a distilled water-ethanol mixture (95:5 v/v). The insecticide activity of indoxacarb (at the highest application rate recommended for tomato crops, 12.5 g/hL) and neem (at the recommended dose of 300 cc/100L) was also evaluated and used as the positive controls. Each treatment consisted of 100 replications with a second instar larvae for each replicate. The Petri dishes were placed in greenhouse conditions. The mortality was counted after 72 h of treatment24. To determine the sublethal effects, 200 s instar larvae of tomato leafminer were exposed to LC50 values of OVE and OVE-NLC. After 24 h, 65 live larvae were randomly controlled every 24 h, and observations (developmental duration and survivorship of different biological stages) were recorded until adults emerged. The results obtained for all treatments were compared with those of positive and negative controls.

Contact toxicity

To determine the contact toxicity of tested compounds against T. absoluta, prepared tomato leaves were dipped in appropriate concentrations of OVE and OVE-NLC for 20 s after which leaves were left to air dry. Indoxacarb and neem were used as positive controls at their recommended dose and control NLC formulation and a distilled water-ethanol mixture (95:5 v/v) were used as negative controls. Treated leaves were placed separately in a plastic Petri dish (6 cm diameter) containing a wet piece of filter paper. Then, 20 s instar larvae of T. absoluta (< one day old) were randomly selected and transferred into each leaf disc. The treatment for each concentration was replicated 5 times. After exposure to treatments for 72 h, mortality rates were measured25. The above-described methodology was also used in determining the sublethal effects of OVE and OVE-NLC in comparison with positive and negative controls.

Effect on fecundity

The effect of OVE and OVE-NLC at their LC50/LD50 concentrations was investigated on the fecundity of female T. absoluta, as well. For this experiment, after the adults emerged from the aforementioned experiments (sublethal toxicity via topical and contact assays), 20 newly emerged pairs of each treatment were picked randomly, and each pair was transferred to a mating plastic cage (14 × 11 × 5 cm) provided with 10% honey solution to lay eggs on tomato leaves. The number of eggs laid per female was recorded daily until the death of the females.

Ovideterrence test

The repellent activity of OVE and OVE-NLC at their LC50 and LC90 concentrations obtained from the contact toxicity bioassay for T. absoluta was evaluated in the two-choice assays. For this experiment, newly emerging adults of T. absoluta were placed in a screened cage to mate 24 h before the experiment. Treated tomato leaves were air-dried and placed in a cage (40 × 40 × 40 cm) containing 20 adults to lay eggs. After 72 h, adults were removed, and the number of eggs laid on each tomato leaf was recorded. Five replicates were performed for each two-choice assay18. Distilled water-ethanol mixture and NLC sample prepared without OVE loading were used as negative controls, and commercial neem extract as positive control.

Non-target effect assay

Macrolophus pygmaeus

Topical toxicity

Coetaneous 24 h old adults of M. pygmaeus were topically exposed to 1 µL of positive (neem and indoxacarb) and negative (NLC sample prepared without OVE loading and a distilled water-ethanol mixture) controls or the OVE and OVE-NLC solutions at their LD50 concentrations obtained from the topical toxicity assay for T. absoluta. Adults were first anesthetized with CO2 gas and then received the treatment on their backs with the aid of microsyringe. Five replicates of 20 insects were used for each treatment. Treated insects were put individually into plastic Petri dishes (6 cm diameter) with a ventilated lid and a tomato leaflet. E. kuehniella eggs as factitious prey were added to the Petri dishes. Bioassays were conducted under greenhouse conditions, and mortality was assessed 72 h after exposure24.

Contact toxicity

Briefly, tomato leaves were dipped in the OVE and OVE-NLC solutions at their LC50 concentrations obtained from the contact toxicity bioassay for T. absoluta for 20s. Indoxacarb and neem were used as positive controls. The negative controls consisted of an NLC sample prepared without OVE loading and a distilled water-ethanol mixture. The leaves were air-dried and then placed individually in plastic Petri dishes, with their petioles in contact with moist cotton. Then, 20 M. pygmaeus adults (one-day-old) were transferred to each Petri dish. Mortality assessments were carried out 72 h after exposure. All treatments were replicated 5 times, with 20 predatory bugs per replication26.

Bombus terrestris

Topical toxicity

The healthy bees were collected from the hive in the darkness and were briefly immobilized in a 1 L flask by exposure to CO2 (2–5 s). Red light was used only when necessary for handling or picking up workers. Subsequently, the anesthetized workers were immediately treated with 1 µL of each compound at their LD50 concentration obtained from topical toxicity bioassay for T. absoluta. Indoxacarb and neem were used as the recommended concentrations as positive controls. NLC sample prepared without OVE loading and a distilled water-ethanol mixture were served as negative controls. The treated bees were transferred individually to a transparent plastic round box (9 cm diameter, 5 cm height) with a ventilated lid. A feeder (Eppendorf®, containing sugar/water syrup 50% v/v) with a hole at the end was added to each box. Fresh thawed pollen was also used as a supplementary food source. The boxes were maintained in greenhouse conditions. For each treatment, 10 bees were tested in three replications. The mortality of the bees was measured 72 h after exposure4.

Contact toxicity

Residual contact toxicity of OVE and OVE-NLC on B. terrestris was studied according to the method reported by Besard et al.27 with slight modifications. Tomato leaves were dipped into the bio-insecticide solutions at their LC50 concentrations obtained from contact toxicity bioassay for T. absoluta. Positive and negative controls were similar to the aforementioned assay. Treated leaves were allowed to air dry and put individually into plastic box. Then, for each treatment, 10 workers were transferred into the boxes in three replications. The mortality of bees was measured after 72 h.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were run with the SPSS software package version. 16. The One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student’s t-test with Tukey’s post hoc test were used for comparison among different treatment groups. The life table parameters of T. absoluta were statistically analyzed using TWOSEX-MS Chart software28 and age-stage two-sex life table theory29,30. The variance and standard errors were estimated via 100,000 bootstrap replicates31. All treatment variations were compared using a paired bootstrap test at a 5% significance level based on the confidence interval of differences.

Results

Chemical characterization of Origanum vulgare EO

The GC-MS analysis identifies 16 components of O. vulgare EO representing 100% of the total oil content (Table 1). The major components of the EO were carvacrol (58.10%), thymol (19.64%), m-Cymol (6.84%), gamma.-Terpinene (6.45%), and alpha.-Terpinene (1.44%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

OVE-NLC characterization

Optimized OVE-NLC formulation showed a monomodal and homogeneous size distribution with the mean particle size of 94.26 ± 0.02 nm (Fig. 2). The PDI value was 0.218 ± 0.0008 which confirmed that the system had a low grade of polydispersity. Also, zeta potential of optimized OVE-NLC showed a negative superficial charge (− 18.75 ± 0.04 mV), suggesting favorable physical stability. The average encapsulation efficiency of this formulation was 96.71 ± 0.20%. All of the measurements were performed in triplicate. According to SEM, the control NLC and OVE-NLC nanoparticles had spherical shapes in the size range of 58–79 nm and 75–90 nm, respectively (Fig. 2).

FTIR spectra of control NLC suggested that the absorption peak at 2919 cm− 1 (C–H stretching, alkanes group), 1739 cm− 1 (C=O stretching esterified carboxylic acid), and 1470 cm− 1 (–CH2 bending vibrations). The peak at 1113 indicates the C–O band vibration. FTIR spectroscopy confirmed the incorporation of O. vulgare EO in NLC components and the formation of physical interactions among them without new chemical bonds created (Fig. 2).

Physical properties of (a) control NLC and (b) Origanum vulgare essential oil-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier (OVE-NLC): (ai and bi) particle size, (aii and bii) zeta potential distributions profile, (aiii and biii) scanning electron microscope (SEM) micrograph, and (c) FTIR spectra of OVE-NLC and control NLC.

The physical stability of control NLC and OVE-NLC was followed by measuring the change of size and zeta potential values after their storage for up to 3 months at 20 °C. As shown in Fig. 3, the average particle size of both samples showed a slight variance. For instance, the average particle sizes of control NLC and OVE-NLC obtained after 3 months of storage were increased respectively by only 10 and 30 nm compared to day 1. The PDI ranged from 0.218 to 0.242 and 0.176 to 0.184 for OVE-NLC and control NLC, respectively. Moreover, the PDI and zeta potential values stayed almost constant, indicating a narrow size distribution of particles during storage time, confirming that these types of NLC formulations remain stable for at least 3 months.

Insecticidal assay

Contact toxicity

The findings of this assay demonstrated that OVE and OVE-NLC had contact toxicity against second instar larvae of T. absoluta. The 72 h LC50 value of OVE-NLC was found to be lower than those determined for OVE (Table 3). As shown in Fig. 4, the test materials were toxic to T. absoluta in a dose-dependent manner.

Mean percentage of mortality ± SE of Tuta absoluta second instar larvae in contact bioassays testing different concentrations (used for calculating LC50) of Origanum vulgare pure essential oil (OVE) and OVE-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier (OVE-NLC) in comparison with control groups. Mean followed by the same letters within each column are not significant (One-way ANOVA, Tukeỷs test, P < 0.05).

Topical toxicity

In topical toxicity trials, the toxicity of OVE-NLC with LD50 of 3.36 µg/larvae (Table 4) was significantly greater than that of OVE with LD50 of 8.39 µg/larvae (95% CLs did not overlap at LD50). As shown in Fig. 5, the test materials were toxic to T. absoluta in a dose-dependent manner.

Mean percentage of mortality ± SE of Tuta absoluta second instar larvae in contact bioassays testing different concentrations (used for calculating LD50) of Origanum vulgare pure essential oil (OVE) and OVE-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier (OVE-NLC) in comparison with control groups. Mean followed by the same letters within each column are not significant (One-way ANOVA, Tukeỷs test, P < 0.05).

Female Tuta absoluta fecundity after the treatment with OVE and OVE-NLC at their LC50 concentrations in topical and contact trials

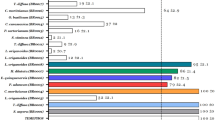

As shown in Fig. 6, OVE-NLC had the highest fecundity-reducing effect and significantly decreased female fecundity by approximately 70% and 42% in contact and topical assays, respectively, in comparison with positive (neem and indoxacarb) and negative (water + ethanol and control NLC) controls.

Fecundity of Tuta absoluta when second instar nymphs treated with LC50/ LD50 concentrations of Origanum vulgare pure essential oil (OVE) and OVE-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier (OVE-NLC) in comparison with positive (neem and indoxacarb) and negative (distilled water + ethanol and control NLC) controls. (a) contact assay, (b) topical assay. Bar heads with different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (One-way ANOVA, Tukeỷs test, P < 0.05).

Population growth parameters

LC50/LD50 values of OVE-NLC severely affected the population intrinsic rate of increase (r) and finite growth rate (λ). The obtained net reproductive rate (R0) and gross reproductive rate (GRR) demonstrated that OVE and OVE-NLC treatments reduced T. absoluta female population. The median generation time (T) for the control NLC was significantly shorter than that of OVE and OVE-NLC treatments and the positive controls (Table 5).

Ovideterrence effect

In two-choice experiments, there were no differences in the number of eggs laid on tomato leaves treated by control NLC and water + ethanol (Fig. 7a), therefore control NLC was used as negative control for other assays. Additionally, significant differences were observed between the number of eggs laid on treated tomato leaves by OVE and OVE-NLC. Females laid 1.7 to 3 times more eggs on treated leaves by OVE LC50 and OVE LC90, respectively (Fig. 7b). Adults of T. absoluta preferred treated leaves by control NLC regardless of the treatments and concentrations of OVE and OVE-NLC used (Fig. 7c, d). The LC90 of OVE-NLC reduced the number of eggs laid by approximately 80% compared to the negative control (control NLC) and did not differ statistically from neem as the positive control (Fig. 7d).

Number of Tuta absoluta eggs laid on tomato leaves in ovideterrence two-choice assays testing Origanum vulgare pure essential oil (OVE) and OVE-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier (OVE-NLC) in comparison with positive (neem) and negative (distilled water + ethanol and control NLC) controls. (a) controls, (b) OVE vs. OVE-NLC, (c) OVE vs. controls, (d) OVE-NLC vs. controls. *Significant; ns, not significant (t-test, P < 0.05).

Non-target effect assay

Seventy-two hours after the application of OVE and OVE-NLC in the LD50/LC50 and LD90/LC90 for T. absoluta, the predator (M. pygmaeus) and the pollinator (B. terrestris) mortality rates were evaluated.

Significant differences were observed among the treatments for predatory bug mortality (Fig. 8). The lowest mortality of M. pygmaeus was observed in treatments with OVE-NLC, resulting in mortality rates of 10–25% in the contact trial and 10–20% in the topical trial. In the topical assay, compared with the other treatments, OVE at LC50/LD50 and LC90/LD90 concentrations was more toxic to M. pygmaeus adults. In contrast, in the contact assay, indoxacarb resulted in the most significant reduction in predatory survival.

Mean of adult mortality of Macrolophus pygmaeus 72 h after application of Origanum vulgare pure essential oil (OVE) and OVE-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier (OVE-NLC) at their LC50/LD50 or LC90/LD90 estimated for Tuta absoluta in comparison with positive (neem and indoxacarb) and negative (distilled water + ethanol and control NLC) controls. (a) contact assay, (b) topical assay. Mean followed by the same letters within each column are not significant (One-way ANOVA, Tukeỷs test, P < 0.05).

When exposing the pollinator bee to OVE and OVE-NLC at their LD50/LC50 and LD90/LC90 concentrations for T. absoluta in contact and topical assays, both the OVE-NLC LC50/LD50 and OVE-NLC LC90/LD90 had a significantly lower impact on B. terrestris mortality than positive controls and OVE (Fig. 9). In detail, this nanoformulation of O. vulgare EO highlighted higher non-target toxicity than the pure form of it (OVE).

As shown in Fig. 9, the two insecticides neem and indoxacarb differently affected bee pollinator mortality. In both application methods, indoxacarb was the most toxic (with a mortality rate of 80% and 58% in the contact and topical assays, respectively). Conversely, neem had a low impact on bee mortality rates (ranging from 15 to 35%). Compared with other treatments, in both tested concentrations, OVE was more toxic to B. terrestris and caused the second-highest mortality effects on the bee pollinator (mortality rates ranging from 35 to 52%, in both tested methods).

Mean of adult mortality of Bombus terrestris 72 after application of Origanum vulgare pure essential oil (OVE) and OVE-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier (OVE-NLC) at their LC50/LD50 or LC90/LD90 estimated for Tuta absoluta in comparison with positive (neem and indoxacarb) and negative (distilled water + ethanol and control NLC) controls. (a) contact assay, (b) topical assay. Mean followed by the same letters within each column are not significant (One-way ANOVA, Tukeỷs test, P < 0.05).

Discussion

The present study showed that O. vulgare EO collected from Urmia, Iran, consisted of carvacrol as a major component. The findings align with Xie et al.32 and de Souza et al.33, who reported that the EO of Chinese and Brazilian oregano had the same major compound with different content levels. In contrast, O. vulgare EO collected from India had thymol as the main compound, followed by γ-terpinene and linalool34. These differences are considerably caused by a mixture of environmental (weather/soil/ nutrition/climate) and genetic factors, which can influence the biosynthesis of EO components. According to earlier findings on the composition of the O. vulgare EO from different parts of the world, this plant species has a wide variety of phytomolecule polymorphs and chemotypes. However, the cymyl-type is the most common and economically important chemotype for O. vulgare EO, which is characterized by carvacrol or thymol as the main component35.

The zeta potential is an important indicator used for the electrostatic stability of nanoparticles, where values greater than + 30 mV or less than − 30 mV indicate good storage stability of the nanoparticles in dispersion36. Also, the PDI value is another important parameter reflecting the nanoparticle size distribution and homogeneity. The PDI value range from 0.1 to 0.25 indicates a homogeneous particle size distribution37. In the current study, the obtained values of zeta potential and PDI confirmed the stability and homogeneity of particles in the produced OVE-NLC formulation.

The ratio of solid lipid compared to liquid lipid has a significant effect on NLCs particle size and stability38. A study conducted by Pezeshki et al.39 evaluated the effect of different solid-to-liquid lipid concentrations (2:1, 4:1, and 10:1) on stability and particle size of NLC formulations and demonstrated that the use of a solid lipid-to-liquid oil ratio of 10 to 1, compared to other ratios led to a narrower particle size distribution and stable system, which is what happened in the current study. Additionally, consistent with our results, previous studies reported that NLCs with an optimal concentration of Poloxamer (5% w/v) and a Mygliol: EO ratio of 50:50 or higher are strongly stable and free from aggregation17,40.

FTIR analysis revealed that the OVE-NLC spectrum was similar to that of the corresponding control NLC formulation, with the same absorption band profile. These results were consistent with some previous findings such as cinnamon and red sacaca essential oils loaded NLC system22,41.

The present study demonstrated for the first time the potential lethal and sublethal activities of O. vulgare EO and its nanostructured lipid carrier formulation against T. absoluta. These compounds also showed an oviposition deterrence effect against this invasive tomato pest. These findings can be very useful, considering that T. absoluta has a high tendency to develop resistance to conventional insecticides1. The insecticidal activity of O. vulgare EO has already been proven for different insect pests belonging to the orders Coleoptera, Lepidoptera, Hemiptera, Isoptera, and Diptera42. The insecticidal activity of O. vulgare EO in the present study may initially be related to its constituents. As the main monoterpenoid compounds in oregano EO studied herein, carvacrol and thymol demonstrated insecticidal activity against different field crop insect pests43. Therefore, carvacrol and thymol might be responsible for the toxicity of Oregano EO against T. absoluta.

In addition to the insecticidal effect, we observed lower rates of oviposition on leaves treated with OVE and OVE-NLC in two choice assays. These results may be related to the ovipositional deterrent effects of O. vulgare EO against adults of T. absoluta, which preferred to oviposit on untreated leaves. Reduction in oviposition can represent a significant reduction in the T. absoluta population and, therefore, can be a useful approach to avoid increasing pest population on tomato plants in greenhouse and field conditions. The effect of oviposition deterrence can also be related to the carvacrol and thymol as major components of O. vulgare EO. As an example, these compounds had a substantial oviposition deterrent effect against Frankliniella occidentalis Pergande on plum blossoms44.

The masking effect of some Lamiaceae plant species EOs on volatile tomato chemicals is recognized as a probable reason responsible for the oviposition deterrence displayed by these plants, which prevents T. absoluta females from identifying the presence of tomatoes45. A literature survey revealed that some studies on the oviposition deterrence of T. absoluta have been conducted using laurel, Spanish oregano, basil, and garlic EOs in tunnels/field/greenhouse45,46. An oviposition repellence caused by nanoformulation of Allium sativum L. EO against T. absoluta has also been reported by Ricupero et al.47.

According to previous studies, encapsulating different EOs in NLCs increases their stability as well as improves their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial activities48,49. Consistent with our results, Radwan et al.45 reported that compared to the essential oils alone, the biological evaluation of NLC-encapsulated fennel essential oil showed potential results on both larvicidal and adulticidal effects against Culex pipiens L.

Moreover, a significant reduction in fecundity was observed in T. absoluta females that emerged from second instar larvae exposed to LC50 or LD50 of OVE and OVE-NLC, indicating that these bioinsecticides can reduce offspring and the population size of subsequent generations of T. absoluta. As determined in previous studies, poor nutrition before adult emergence and antifeedant activity of essential oils affected female fecundity51,52. Exposure to sublethal concentrations of insecticides can have intergenerational and transgenerational effects on tested insects. Here, OVE and OVE-NLC negatively impacted the T. absoluta F1 population (r, λ, and R0). This indicated that OVE and OVE-NLC significantly inhibited the reproduction and propagation ability of the progeny population53. de Figueiredo et al.24 reported that key population parameters of T. absoluta were decreased significantly after treatment with LC50 of Cinnamomum spp. essential oil. According to earlier funding, sublethal effects on biological and population parameters of the target insects are related to the type of insecticides and insect pest species53.

Numerous scientific studies have been published in recent years that demonstrate chemical insecticides’ detrimental effects on human and environmental health. Therefore, bio-insecticides are becoming more popular, and their use for managing dangerous arthropods has been increasing4. In the current study, besides the direct topical toxicity, the residual contact application method was also investigated, considering that non-target organisms may come into contact with the bio-insecticides residues during their foraging behaviors. According to our results, among the products tested, OVE-NLC stood out with its low lethal effects for two non-target organisms in both contact and topical methods. These results can be attributed to the effect of NLC formulation of O. vulgare EO, which is known to be crucial in enhancing the stability and the gradual release of the EO therefore influencing its toxicity22.

Our results are in partial accordance with Arno and Gabarra54, who found that seven days after applying the indoxacarb and azadirachtin against M. pygmaeus via the contact method, the mortality rates were 51% and 5%, respectively. On the contrary, Martinou et al.26 results showed that indoxacarb killed 30% of M. pygmaeus in the contact application.

In another study, Stanley et al.55 found that the application of indoxacarb on honey bees resulted in a lethality of 50% in the residual contact application and 86% in the topical application, at 48 h after treatment. These results are close to those obtained in the current study.

As regards the low non-target effects for neem, it is stated that the low solubility of this insecticide and comparatively lower insecticidal effectiveness compared to the deterrence effect at the same dose are the important limitations of using it in field applications56. In this context, our results for the toxicity and oviposition deterrent effect of OVE-NLC against P. absolute, as well as its negligible effects on tested non-target organisms, can be promising. However, before drawing final conclusions on this O. vulgare EO nanoformulation for its inclusion into T. absoluta IPM strategies, further research on OVE-NLC toxicity on different life stages of pollinator bee and mirid predator and its sublethal impacts under different environmental conditions are needed47,57.

Conclusions

The considerable lethal and sublethal effects of OVE-NLC against T. absoluta and the absence of toxic effects towards the generalist predator M. pygmaeus and the pollinator bee B. terrestris suggest that the application of OVE-NLC could be a viable option for managing T. absoluta populations even in the presence of the adult predators and pollinators. The obtained optimal physical characterizations for OVE-NLC nanoformulation, allowing good stability over 3 months, is another positive result. However, the lethal effects of this nanoformulation of O. vulgare EO on larval stages of M. pygmaeus and B. terrestris and its sublethal effects should also be investigated in future research under greenhouse and open field production areas to contribute to the elimination of many doubts on EO-loaded NLCs by considering the results obtained in the present study.

Data availability

All data supporting this study’s findings are included in the article.

References

Koller, J. et al. A parasitoid Wasp allied with an entomopathogenic virus to control Tuta absoluta. Crop Prot. 179, 106617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2024.106617 (2024).

Bello, A. S. et al. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) yield response to drip irrigation and nitrogen application rates in open-field cultivation in arid environments. Sci. Hortic. 334, 113298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113298 (2024).

Toni, H. C., Djossa, B. A., Ayenan, M. A. T. & Teka, O. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) pollinators and their effect on fruit set and quality. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 96 (1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14620316.2020.1773937 (2021).

Demirozer, O., Uzun, A. & Gosterit, A. Lethal and sublethal effects of different biopesticides on Bombus terrestris (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Apidologie 53 (2), 24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-022-00933-6 (2022).

Kumar, A. et al. Rapid detection of the invasive tomato leaf miner, Phthorimaea absoluta using simple template LAMP assay. Sci. Rep. 15, 573. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84288-1 (2025).

Soleymanzadeh, A., Valizadegan, O., Saber, M. & Hamishehkar, H. Toxicity of Foeniculum vulgare essential oil, its main component and nanoformulation against Phthorimaea absoluta and the generalist predator Macrolophus Pygmaeus. Sci. Rep. 15, 16706. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01193-x (2025).

Konan, K. A. J. et al. Combination of generalist predators, Nesidiocoris tenuis and Macrolophus pygmaeus, with a companion plant, Sesamum indicum: what benefit for biological control of Tuta absoluta? Plos One. 16, 0257925. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257925 (2021).

Borges, I. et al. Prey consumption and conversion efficiency in females of two feral populations of Macrolophus pygmaeus, a biocontrol agent of Tuta absoluta. Phytoparasitica 52, 31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12600-024-01130-0 (2024).

Mohammadi, R., Valizadegan, O. & Soleymanzadeh, A. Lethal and sublethal effects of matrine (Rui agro®) on the tomato leaf miner, Tuta absoluta and the predatory bug macrolophus Pygmaeus. J. App Res. Plant. Prot. 14 (2), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.22034/arpp.2022.15200 (2025).

Mesri, H., Valizadegan, O. & Soleymanzade, A. Laboratory assessment of some chemical insecticides toxicity on Brevicoryne brassicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae) and their selectivity for its predator, Hippodamia variegata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Iran. J. Plant. Prot. Sci. 54 (1), 165–186. https://doi.org/10.22059/IJPPS.2023.360644.1007032 (2023).

Soleymanzade, A., Valizadegan, O. & Askari Saryazdi, G. Biochemical mechanisms and cross resistance patterns of Chlorpyrifos resistance in a laboratory-selected strain of Diamondback Moth, Plutella Xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 21 (7), 1859–1870 (2019a).

Soleymanzade, A., Khorrami, F. & Forouzan, M. Insecticide toxicity, synergism and resistance in Plutella Xylostella (Lepidoptera: plutellidae. Acta Phytopathol. Entomol. Hung. 54 (1), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1556/038.54.2019.013 (2019b).

Tortorici, S. et al. Nanostructured lipid carriers of essential oils as potential tools for the sustainable control of insect pests. Ind. Crops Prod. 181, 114766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.114766 (2022).

Modafferi, A. et al. Bioactivity of Allium sativum essential oil-based nano-emulsion against Planococcus citri and its predator Cryptolaemus Montrouzieri. Ind. Crops Prod. 208, 117837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117837 (2024).

Angellotti, G., Riccucci, C., Di Carlo, G., Pagliaro, M. & Ciriminna, R. Towards sustainable pest management of broad scope: sol-gel microencapsulation of Origanum vulgare essential oil. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 112 (1), 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10971-024-06512-8 (2024).

Werdin González, J. O., Gutiérrez, M. M., Murray, A. P. & Ferrero, A. A. Composition and biological activity of essential oils from labiatae against Nezara viridula (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) soybean pest. Pest Manag Sci. 67 (8), 948–955. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2138 (2011).

Múnera-Echeverri, A., Múnera-Echeverri, J. L. & Segura-Sánchez, F. Bio-pesticidal potential of nanostructured lipid carriers loaded with thyme and Rosemary essential oils against common ornamental flower pests. Colloids Interfaces. 8 (5), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids8050055 (2024).

Tortorici, S. et al. Toxicity and repellent activity of a Carlina oxide nanoemulsion toward the South American tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta. J. Pest Sci. 98, 309–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-024-01785-y (2025).

Sivalingam, S. et al. Encapsulation of essential oil to prepare environment friendly nanobio-fungicide against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici: an experimental and molecular dynamics approach. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem Eng. Asp. 681, 132681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2023.132681 (2024).

Piran, P., Kafil, H. S., Ghanbarzadeh, S., Safdari, R. & Hamishehkar, H. Formulation of menthol-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers to enhance its antimicrobial activity for food preservation. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 7 (2), 261. https://doi.org/10.15171/apb.2017.031 (2017).

Khezri, K., Farahpour, M. R. & Mounesi Rad, S. Efficacy of Mentha pulegium essential oil encapsulated into nanostructured lipid carriers as an in vitro antibacterial and infected wound healing agent. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem Eng. Asp. 589, 124414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.124414 (2020).

Bashiri, S., Ghanbarzadeh, B., Ayaseh, A., Dehghannya, J. & Ehsani, A. Preparation and characterization of chitosan-coated nanostructured lipid carriers (CH-NLC) containing cinnamon essential oil for enriching milk and anti-oxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 119, 108836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108836 (2020).

Khosh Manzar, M., Pirouzifard, M. K., Hamishehkar, H. & Pirsa, S. Cocoa butter and cocoa butter substitute as a lipid carrier of Cuminum cyminum L. essential oil; physicochemical properties, physical stability and controlled release study. J. Mol. Liq. 319, 114303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113638 (2020).

de Figueiredo, K. G. et al. Toxicity of cinnamomum spp. Essential oil to Tuta absoluta and to predatory Mirid. J. Pest Sci. 97 (3), 1569–1585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-023-01719-0 (2024).

Piri, A. et al. Toxicity and physiological effects of Ajwain (Carum copticum, Apiaceae) essential oil and its major constituents against Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Chemosphere 256, 127103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127103 (2020).

Martinou, A. F., Seraphides, N. & Stavrinides, M. C. Lethal and behavioral effects of pesticides on the insect predator Macrolophus Pygmaeus. Chemosphere 96, 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.10.024 (2014).

Besard, L., Mommaerts, V., Abdu-Alla, G. & Smagghe, G. Lethal and sublethal side‐effect assessment supports a more benign profile of Spinetoram compared with spinosad in the bumblebee Bombus terrestris. Pest Manag Sci. 67 (5), 541–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2093 (2011).

Chi, H. TWOSEX-MSChart: a computer program for the age-stage, two-sex life table analysis. Accessed on 25 May (2005). (2005).

Chi, H. & Liu, H. Two new methods for the study of insect population ecology. Bull. Inst. Zool. Acad. Sin. 24 (2), 225–240 (1985).

Chi, H. Life-table analysis incorporating both sexes and variable development rates among individuals. Environ. Entomol. 17, 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/17.1.26 (1988).

Effron, B., Tibshirani, R. J. & Probability An introduction to the bootstrap. ChapmanHall/CRC, Monographs on Statistics and Applied New York. (1993).

Xie, Y., Huang, Q., Rao, Y., Hong, L. & Zhang, D. Efficacy of Origanum vulgare essential oil and carvacrol against the housefly, musca domestica L. (Diptera: Muscidae). Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 26, 23824–23831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05671-4 (2019).

De Souza, G. T. et al. Effects of the essential oil from Origanum vulgare L. on survival of pathogenic bacteria and starter lactic acid bacteria in semihard cheese broth and slurry. J. Food Prot. 79 (2), 246–252. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-15-172 (2016).

Goyal, S., Tewari, G., Pandey, H. K. & Kumari, A. Exploration of productivity, chemical composition, and antioxidant potential of Origanum vulgare L. grown at different geographical locations of Western himalaya. India J Chem. 1, 6683300. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6683300 (2021).

Khan, M. et al. The composition of the essential oil and aqueous distillate of Origanum vulgare L. growing in Saudi Arabia and evaluation of their antibacterial activity. Arab. J. Chem. 11 (8), 1189–1200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2018.02.008 (2018).

Moazeni, M. et al. Lesson from nature: Zataria multiflora nanostructured lipid carrier topical gel formulation against Candida-associated onychomycosis, a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Med. Drug Discov. 22, 100187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medidd.2024.100187 (2024).

Hoseini, B. et al. Application of ensemble machine learning approach to assess the factors affecting size and polydispersity index of liposomal nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 18012. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43689-4 (2023).

Apostolou, M., Assi, S., Fatokun, A. A. & Khan, I. The effects of solid and liquid lipids on the physicochemical properties of nanostructured lipid carriers. J. Pharm. Sci. 110 (8), 2859–2872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xphs.2021.04.012 (2021).

Pezeshki, A. et al. Nanostructured lipid carriers as a favorable delivery system for β-carotene. Food Biosci. 27, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2018.11.004 (2019).

Fitriani, E. W., Avanti, C., Rosana, Y. & Surini, S. Development of nanostructured lipid carrier containing tea tree oil: physicochemical properties and stability. J. Pharm. Pharmacog Res. 11 (3), 391–400. https://doi.org/10.56499/jppres23.1581_11.3.391 (2023).

Chura, S. S. D. et al. Red Sacaca essential oil-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers optimized by factorial design: cytotoxicity and cellular reactive oxygen species levels. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1176629. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1176629 (2023).

Jbilou, R., Matteo, R., Bakrim, A., Bouayad, N. & Rharrabe, K. Potential use of Origanum vulgare in agricultural pest management control: a systematic review. J. Plant. Dis. Prot. 131 (2), 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41348-023-00839-0 (2024). hHadley Centre for Climate, Met Officettp:.

Abdelgaleil, S. A. M., Gad, H. A., Ramadan, G. R. M., El-Bakry, A. M. & El-Sabrout, A. Monoterpenes for management of field crop insect Hadley centre for Climate, Met officepests. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 25 (4), 769–784 (2023).

Allsopp, E., Prinsloo, G. J., Smart, L. E. & Dewhirst, S. Y. Methyl salicylate, thymol and carvacrol as oviposition deterrents for Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) on Plum blossoms. Arthropod Plant. Interac. 8, 421–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11829-014-9323-2 (2014).

Yarou, B. B. et al. Oviposition deterrent activity of Basil plants and their essentials oils against Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 25, 29880–29888. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-9795-6 (2017).

Lo Pinto, M., Vella, L. & Agrò, A. Oviposition deterrence and repellent activities of selected essential oils against Tuta absoluta meyrick (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae): laboratory and greenhouse investigations. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 42 (5), 3455–3464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42690-022-00867-7 (2022).

Ricupero, M. et al. Bioactivity and physico-chemistry of Garlic essential oil nanoemulsion in tomato. Entomol. Gen. 42, 921–930. https://doi.org/10.1127/entomologia/2022/1553 (2022).

Carbone, C. et al. Mediterranean essential oils as precious matrix components and active ingredients of lipid nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 548 (1), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.06.064 (2018).

Ghodrati, M., Farahpour, M. R. & Hamishehkar, H. Encapsulation of peppermint essential oil in nanostructured lipid carriers: In-vitro antibacterial activity and accelerative effect on infected wound healing. Coll. Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 564, 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.12.043 (2019).

Radwan, I. T., Baz, M. M., Khater, H. & Selim, A. M. Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) for biologically active green tea and fennel natural oils delivery: Larvicidal and adulticidal activities against Culex pipiens. Molecules. 27(6), 1939. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27061939 (2022).

Goane, L. et al. Antibiotic treatment reduces fecundity and nutrient content in females of Anastrepha fraterculus (Diptera: Tephritidae) in a diet dependent way. J. Insect Physiol. 139, 104396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2022.104396 (2022).

Ouabou, M. et al. Insecticidal, antifeedant, and repellent effect of Lavandula mairei var. Antiatlantica essential oil and its major component carvacrol against Sitophilus oryzae. J. Stored Prod. Res. 107, 102338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2024.102338 (2024).

Ding, W. et al. Lethal and sublethal effects of Afidopyropen and Flonicamid on life parameters and physiological responses of the tobacco whitefly, bemisia tabaci MEAM1. Agronomy 14 (8), 1774. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14081774 (2024).

Arnó, J. & Gabarra, R. Side effects of selected insecticides on the Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) predators Macrolophus Pygmaeus and Nesidiocoris tenuis (Hemiptera: Miridae). J. Pest. Sci.. 84, 513–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-011-0384-z (2011).

Stanley, J., Sah, K., Jain, S. K., Bhatt, J. C. & Sushil, S. N. Evaluation of pesticide toxicity at their field recommended doses to honeybees, apis Cerana and A. mellifera through laboratory, semi-field and field studies. Chemosphere 119, 668–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.07.039 (2015).

Jeon, H. & Tak, J. H. Gustatory habituation to essential oil induces reduced feeding deterrence and neuronal desensitization in Spodoptera Litura. J. Pest Sci. 98, 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-024-01794-x (2024).

Abbes, K. et al. Combined non-target effects of insecticide and high temperature on the parasitoid Bracon nigricans. PloS One. 10 (9), 0138411. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138411 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Deputy of Research and Technology of Urmia University, Urmia, Iran (Number: 10/1352) is acknowledged.

Funding

This study was funded by Urmia University, Iran (Number: 10/1352).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS, OV, and HH conceived and designed the experiments. AS collected data and carried out the bioassays. AS and OV analyzed the data. AS wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and OV and HH revised and improved it. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soleymanzadeh, A., Valizadegan, O. & Hamishehkar, H. Nanostructured lipid carrier of oregano essential oil for controlling Tuta absoluta with minimal impact on beneficial organisms. Sci Rep 16, 3538 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33492-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33492-8