Abstract

Curated electronic health records offer valuable insights into real-world outcomes for patients with advanced tumors. We described real-world treatment effectiveness among patients with HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer (mBC) and metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC) using ConcertAI Patient360™ Breast Cancer dataset. Patients initiating therapies selected based on literature review and data availability in the metastatic setting between January 1, 2016, and November 30, 2021, were included. Real-world response rate (rwRR), progression-free survival (rwPFS), overall survival (rwOS), time-to-next treatment (rwTTNT), and time-to-discontinuation (rwTTD) were assessed. Three HR+/HER2- mBC cohorts included 292 patients treated with palbociclib + fulvestrant, 274 patients treated with fulvestrant monotherapy, and 381 patients treated with paclitaxel-based therapy; the mTNBC cohort included 247 chemotherapy-treated patients. Median rwOS in three HR+/HER2- cohorts ranged from 15.6 to 32.3 months and was 13 months in mTNBC; median rwPFS ranged from 5.6 to 8.6 months, and 4.4 months, respectively. The alignment between several real-world and clinical trial endpoints is encouraging and supports the utility of real-world data in contextualizing outcomes, though interpretation may be influenced by data completeness and variability in clinical documentation. These insights are particularly relevant for populations with persistent unmet clinical needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One in eight women will receive a diagnosis of breast cancer in their lifetime, making it the most common malignancy among females1. Molecular biomarkers play a key role in determining disease course and guiding targeted therapy development. Approximately 80% of breast cancer cases are human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2-, defined IHC0, 1+, 2+/ISH-), meaning that they do not overexpress HER2 protein and can be further classified based on hormone receptor status2,3. Approximately 60–70% of HER2- tumors are classified as hormone receptor-positive (HR+), characterized by expression of estrogen receptors (ER) and/or progesterone receptors (PR). The remaining HER2- tumors, approximately 15% of all invasive cancers, are triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), lacking ER, PR, and HER2 and characterized by aggressive tumor biology and relatively poor prognosis4,5.

HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer (mBC) first-line therapy is generally a combination therapy of a cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor (CDK4/6i) and endocrine therapy6. Despite some improvements in outcomes, most patients eventually develop resistance, highlighting substantial unmet need7,8.

Historically, metastatic TNBC (mTNBC) has limited treatment options, partly due to the lack of responding molecular targets, with chemotherapy being the main option. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase inhibitors (PARPi), and antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) that were approved after 2021 increased available therapies; however, overall survival (OS) remains low, underscoring high unmet need in this population.

Real-world studies evaluating the safety and effectiveness of therapies in the broader population treated in routine clinical practice are becoming increasingly important. The 21st Century Cures Act in 2016 in the United States (US) accelerated efforts to use real-world data to complement clinical trials9. Several initiatives have been launched to enhance the use of real-world. These initiatives, such as DUPLICATE and CARE, aim to develop methodologies and generate evidence that supports the use of real-world data to emulate randomized controlled trials10,11. In oncology, the Friends of Cancer Research (FOCR) Real-World Data Collaboration has been particularly influential12,13,14. The first two pilot projects by FOCR (Real-World Data Collaboration Pilot 1.0 and Pilot 2.0) assessed the consistency of real-world endpoints with estimates generated in clinical trials in a population of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) using multiple administrative claims and electronic health records (EHR) datasets12,13. The projects found that real-world endpoints, including real-world progression-free survival (rwPFS), real-world overall survival (rwOS), real-world time to next treatment (rwTTNT), real-world time to discontinuation (rwTTD), and real-world response rate (rwRR), can be consistently operationalized across multiple data sources and show alignment with clinical trial outcomes.

However, this framework has not been applied to breast cancer, a heterogeneous disease with multiple subtypes and treatment pathways15. Recently, a report published by Multidisciplinary Think Tank (TRIUMPH) called for clinically-relevant, patient-informed real-world evidence (RWE) studies in breast cancer, emphasizing the need for tailored endpoints and advocating for further dissemination of RWE results and building consensus16. To conduct this type of research, access to multi-modal data sources that provide longitudinal patient histories and granular clinical and sociodemographic information is essential. ConcertAI Patient360 offers a unique opportunity to meet these needs, enabling large-scale evidence generation. Additionally, the initial FOCR Real-World Data Collaboration Pilot 1.0 incorporated a range of real-world data sources but did not include ConcertAI’s Patient360 dataset, representing a gap among commonly used oncology data sources for evaluating consistency with clinical trial results.

Several real-world analyses have reported outcomes in HER2- metastatic breast cancer; however, these studies often examine isolated therapies or selected cohorts and may not apply a harmonized methodological approach17,18,19,20,21. The goal of this study was to describe demographics, clinical characteristics, and real-world treatment effectiveness across multiple therapies recently evaluated in global clinical trials in HER2- mBC subtypes using an oncology-specific EHR dataset by applying similar methodological considerations as the FOCR studies.

Methods

This study was reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for cohort studies22. It involved secondary research on previously collected, de-identified data with no traceability to the patient’s identification. Given these considerations, the approval and informed consent were waived by WCG Connexus (Western Institutional Review Board (W)-Copernicus Group (CG). All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Study population

A targeted literature review was conducted to identify recently published clinical trials in patients with previously treated HER2- mBC. The treatment regimens used to define the study cohorts were based on experimental and comparator arms from these trials. Regimens were selected based on their clinical relevance (i.e., approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and included in treatment guidelines for the subtypes of interest at the time of the study) and the availability of a sufficient sample size within the ConcertAI Patient360™ Breast Cancer dataset at the time of the study. The literature review used PubMed and included publications with a publication date after 2016, for clinical trials focusing on patients with previously treated HR+/HER2- mBC or mTNBC; the literature review is available as supplemental materials (Supplemental Table 1).

This study, using U.S.-based EHR data, focused on patients with HR+/HER2- mBC or mTNBC, and included four distinct patient cohorts. The treatment regimens of interest were derived from PALOMA-3 (NCT01942135)23 and PASO (NCT01320111)24 trials for HR+/HER2- mBC and the ASCENT (NCT02574455)25 trial for mTNBC. The regimens selected to create the four cohorts were: 1) HR+/HER2- palbociclib + fulvestrant combination therapy (PALOMA-3 experimental arm), 2) HR+/HER2- fulvestrant monotherapy (PALOMA-3 active comparator arm), 3) HR+/HER2- paclitaxel-based therapy (PASO active comparator arm), and 4) TNBC chemotherapy (ASCENT active comparator arm). ASCENT and PASO experimental arm treatments did not have an adequate sample size in the dataset at the time of study and were therefore not included among the treatments of interest.

To be included in one of the four treatment cohorts, patients were required to have a diagnosis of mBC and at least two separate clinical encounters between January 1, 2016 and November 30, 2022. Patients were required to initiate the treatment of interest at least one year before the end of data cut off (November 30, 2021) to allow for the potential of one year of follow-up; patients were not required to have any minimum amount of follow-up. Patients were excluded if they had a previous diagnosis for a non-breast primary cancer (except for non-melanoma skin cancer). The index date was the start of the line of therapy containing the regimen of interest for each treatment-based cohort. For all cohorts, HR status was determined using ER and PR biomarker results between the metastatic diagnosis date and the index date; HER2 status was also defined using the same time period.

Patients treated with palbociclib + fulvestrant combination therapy, fulvestrant monotherapy, or any paclitaxel-based therapy for metastatic disease were required to have HR+/HER2- mBC. All patients in the HR+/HER2- cohorts were required to have at least one but at most six prior lines of therapy in the metastatic setting before starting one of the treatment regimens. Treatment lines of interest for this study were selected based on clinical relevance and sample size within the data. Patients were excluded from the HR+/HER2- cohorts if they received prior treatment in the metastatic setting for HER2+ disease.

TNBC patients treated with the most common regimens in the database (eribulin, vinorelbine, capecitabine, gemcitabine, albumin-bound paclitaxel, or paclitaxel) in the metastatic setting were included in the mTNBC cohort. All patients in the mTNBC treatment-based cohort were required to have at least one but at most three prior lines of therapy in the metastatic setting. Patients with evidence of treatment in the metastatic setting for HR+ or HER2+ disease were excluded from the mTNBC cohort.

Data source

This study utilized US-based EHR data from the ConcertAI Patient360™ Breast Cancer database. The ConcertAI Patient360™ Breast Cancer data includes medical history, treatment details, and key clinical outcomes, augmented with manual review and collection from unstructured records and enriched using artificial intelligence (AI) technology to provide a holistic view of each patient’s health journey. AI includes natural language processing (NLP) text extraction from unstructured documents, rules-based and machine-learning models associated with line of therapy analysis, and quality checks. At the time of study (May 2023), the dataset included 53,027 patients with breast cancer from hundreds of oncology practices across the US that are primarily community-based centers (approximately 30% of patients received care in academic centers). Variables necessary to supplement known gaps in oncology-specific structured EHR data, such as clinical/pathological staging, exposure to oral anti-cancer medications, and tumor response, among others, are abstracted from unstructured documents via trained abstractors reviewing records. Race and ethnicity information is abstracted from the EHR at point of care which includes a mix of patient self-report and provider-reported race/ethnicity. Lines of therapy are derived by the data vendor as regimens categorized into chemotherapy, targeted therapy, hormone/endocrine, and immunotherapy based on abstracted unstructured data as well as structured data from EHRs. Date of death is collected from EHR, digital obituaries, burial records, administrative claims, and government sources. Sources of death information are aggregated and prioritized to create a comprehensive, patient-level, all-source composite mortality endpoint26. Additional information on the data can be found at: https://www.concertai.com/patient360.

Study measurements

The baseline characteristics for this study were selected based on clinical relevance, and availability within the data source. The initial assessment period for the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score was defined as 30 days prior to the index date. In addition, a 90-day ECOG window prior to the index date was evaluated to account for inconsistent reporting, but only one value was used in the analysis. The endpoints for this study included rwOS, rwPFS, rwRR, rwTTNT, and rwTTD. rwRR was defined as the proportion of patients with a best overall response of real-world complete response (rwCR) or partial response (rwPR) occurring ≥ 14 days after index treatment initiation. RECIST criteria were not applied due to differences in response capture in real-world settings. rwOS was measured from the index treatment start to death. rwPFS was measured from index treatment start to real-world progression (rwP) or death, with events occurring ≥ 14 days after treatment initiation. rwTTNT was measured from the index treatment start to initiation of a subsequent line of therapy, or death. rwTTD was measured from the index treatment start to treatment discontinuation or death. Complete endpoint definitions and censoring criteria can be found in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

The primary aim of the study was to explore patients’ characteristics and outcomes in real world population. Data was summarized using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were reported as mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range; for categorical variables, counts and percentages were provided. Kaplan–Meier method was used to report the median survival time for the time-to-event endpoints (rwOS, rwPFS, rwTTNT, rwTTD). The percentage of patients was calculated for rwRR. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were presented for all endpoints. All analyses were conducted using Aetion Substantiate and R version 4.3.127.

Results

Patients

Within the US-based EHR dataset used for this study, 6867 patients had a diagnosis of mBC between January 1, 2016, and November 30, 2021, including 1306 with mTNBC and 3761 with HR+/HER2- disease. Among patients with mTNBC, 488 received two to three prior lines of therapy, and among those with HR+/HER2- disease, 1064 received two to six prior lines of therapy. After applying the other inclusion and exclusion criteria, this study included 292 patients in the HR+/HER2- palbociclib + fulvestrant combination therapy cohort, 274 patients in the HR+/HER2- fulvestrant monotherapy cohort, 381 patients in the HR+/HER2- paclitaxel-based therapy cohort, and 247 patients in the mTNBC chemotherapy cohort.

HR+/HER2- mBC cohorts

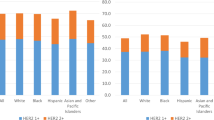

As described in Table 2, the median patient age ranged from 58 years (paclitaxel-based therapy cohort) to 68 years (fulvestrant monotherapy cohort). The HR + /HER2- treatment cohorts included 74.5–83.6% of patients with reported race as “White”. In the 30 days prior to the index date (date of start of treatment of interest, following at least one but at most six prior lines of therapy in the metastatic setting) ECOG status was documented for between 77.0% (fulvestrant monotherapy cohort) and 82.4% (paclitaxel-based cohort) of patients. Expanding the assessment window to 90 days prior to index increased ECOG capture to between 79.6% (fulvestrant monotherapy cohort) and 86.4% (paclitaxel-based cohort). As the 90-day window slightly increased ECOG capture, results are reported using this timeframe. Across all cohorts, the majority of patients had an ECOG score < 2 (63.1–70.8%).

Nearly half or more than half of patients across the three HR+/HER2- cohorts were second line, i.e., experienced only one prior line of therapy, (62.0% of the palbociclib + fulvestrant cohort; 54.7% of the fulvestrant monotherapy cohort, and 49.1% of the paclitaxel-based cohort). Most patients had at least one prior endocrine-based line of therapy in the metastatic setting (72.4–90.5%). A majority of patients in the HR+/HER2- cohorts had bone metastasis (62.2–73.7%). Visceral metastasis (metastasis to the brain, liver, and/or lung) was recorded in 38.4% of the palbociclib + fulvestrant cohort, 36.1% of the fulvestrant monotherapy cohort, and 47.0% of the paclitaxel-based cohort.

mTNBC cohort

The median age was 68 years, and most patients included were peri- or post-menopausal (66.0%). More than a quarter (28.3%) of patients were identified as “Black or African American,” while 66.8% were reported as “White”. Among patients with a reported BRCA status (n = 161, 60.7%), 86.1% of patients were BRCA-wild-type (137/150, Supplemental Table 2). The majority of patients had an ECOG score of 0 or 1 (80.1%) in the 90 days prior to the index date.

Most patients received prior treatment with chemotherapy (96.0%) and had only one prior line in the metastatic setting (85.8%). The most common chemotherapy among the treatments of interest received within the index line (line of therapy following at least one but at most three prior lines of therapy in the metastatic setting) was paclitaxel (37.2%) followed by capecitabine (26.3%), gemcitabine (17.4%), eribulin (18.6%), and vinorelbine (2.0%). Visceral metastasis was recorded in 55.5% of the mTNBC cohort.

Outcomes

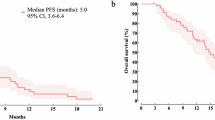

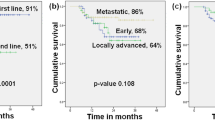

Among patients in this study with HR+/HER2- mBC, median rwOS was 32.3 months (95% CI 25.7–39.7) in the palbociclib + fulvestrant combination therapy cohort, 23.8 months (95% CI 20.7–26.6) in the fulvestrant monotherapy cohort, and 15.6 months (95% CI 12.9–17.6) in the paclitaxel-based therapy cohort (Table 3). The median rwPFS was 8.6 (95% CI 6.6–10.5) months in the palbociclib + fulvestrant combination therapy cohort, 6.4 (95% CI 4.9–8.2) months in the fulvestrant monotherapy cohort, and 5.6 (95% CI 4.9–7.1) months in the paclitaxel-based therapy cohort. In the mTNBC chemotherapy cohort, median rwOS and rwPFS were 13.0 (95% CI 10.6–16.8) months and 4.4 (95% CI 3.4–5.1) months, respectively.

Among the HR+/HER2- treatment cohorts, median rwTTNT ranged from 3.5 (95% CI 3.2–3.8) months (paclitaxel-based therapy cohort) to 7.5 (95% CI 5.9–9.5) months (palbociclib + fulvestrant combination therapy cohort), while median rwTTD ranged from 2.5 (95% CI 2.3–2.6) months (paclitaxel-based therapy cohort) to 5.9 (95% CI 4.6–7.4) months (palbociclib + fulvestrant combination therapy cohort). In the mTNBC chemotherapy cohort, median rwTTNT was 4.2 (95% CI 3.6–5.2) months and median rwTTD was 2.3 (95% CI 2.0–2.8) months.

Tumor response was highly not documented for between 28.1 and 41.5% of patients in the HR+/HER2- cohorts, and 30.4% of patients in the mTNBC cohort. The rwRR varied across HR+/HER2- treatment-based cohorts, ranging from 13.9% (fulvestrant monotherapy) to 27.0% (paclitaxel-based therapy) and was 30.0% in the mTNBC chemotherapy cohort.

Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into real-world effectiveness in patients with HR+/HER2- mBC and mTNBC who received regimens recently evaluated in clinical trials, using the US-based ConcertAI Patient360™ Breast Cancer database. It also explored the feasibility of this database to contextualize trial findings and inform future research.

The findings from this study emphasize the importance of integrating RWE into treatment decision-making, particularly for patients underrepresented in clinical trials. The inclusion of individuals with ECOG scores ≥ 2 and broader treatment histories captures the diversity of real-world oncology populations. Alignment with published real-world literature supports the external validity of these regimens and demonstrates the feasibility of using this large-scale EHR data to contextualize trial findings, identify unmet need, and inform future research. Such insights can guide clinicians in tailoring therapies and refining clinical guidelines to better reflect real-world practice.

Overall, the clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients in the real-world cohorts in this study were similar to patients in clinical trials that were used to identify the treatment regimens of interest (PALOMA-323 and PASO24, ASCENT25). The real-world cohorts included comparable ages, ECOG scores, and postmenopausal statuses. While a majority (> 60% of the patients across all cohorts) of the patients were in the ECOG 0–1 category, inclusion of patients with poor performance (i.e., ECOG ≥ 2) status may contribute to lower survival outcomes.

In the case of the PALOMA-3 trial, real-world outcomes were generally consistent with the trial results, though numerically lower. For palbociclib + fulvestrant, rwOS was 32.3 months (95% CI 25.7–39.7) and rwPFS was 8.6 months (95% CI 6.6–10.5), while the trial reported OS of 34.8 months (95% CI 28.8–39.9) and PFS of 9.2 months (95% CI 7.5–NE). Fulvestrant monotherapy showed rwOS of 23.8 months (95% CI 20.7–26.6) and rwPFS of 6.4 months (95% CI 4.9–8.2), with trial estimates at 28.0 months (95% CI 23.5–33.8) for OS and 3.8 months (95% CI 3.5–5.5) for PFS. While the same regimens were used in the real-world cohort and the trial, differences in dosing patterns, adherence, and monitoring frequency may have contributed to slightly lower rwOS and rwPFS.

When compared to the PASO trial lower rwOS was observed in the real-world cohort (15.6 months [95% CI 12.9–17.6]) compared with trial (20.7 months [95% CI 16.4–26.7]). PFS was similar (5.6 [95%CI 95% CI 4.9–7.1] vs 6.6 [95% CI 95% CI 5.1–9.0] months), suggesting comparable disease control despite differing regimens and eligibility criteria. Key differences in the PASO trial population and the real-world paclitaxel-based cohort were observed in both tumor subtype and treatment regimen. The PASO trial included participants with either HR+/HER2- or TNBC, but the real-world cohort used in this study was restricted to HR+/HER2- patients. In addition, PASO participants received paclitaxel monotherapy while the real-world data cohort included patients treated with both monotherapy (64.3%) and combination (35.7%) paclitaxel therapy, reflecting broader clinical practice.

Differences in treatment history and line of therapy likely explain the longer rwOS (13.0 [95% CI 10.6–16.8] months) observed in this study vs OS of TPC in ASCENT (6.7 [95% CI 5.8–7.7] months). A similar trend was noted for PFS with rwPFS of 4.4 [95% CI 3.4–5.1] months compared to PFS of 1.7 [95% CI 1.5–2.6] months in ASCENT TPC. The real-world mTNBC chemotherapy cohort differed from the ASCENT TPC arm in several clinically relevant ways. The real-world mTNBC cohort included patients treated with paclitaxel, which is a commonly used agent, especially in the earlier lines of therapy. However, this therapy was not part of the ASCENT TPC arm, due to the trial’s requirement of prior taxane treatment as an eligibility criterion. Moreover, 85.8% of the real-world patients had only one prior line of therapy compared to the ASCENT TPC, which was limited to patients with at least two prior lines of therapy with at least one in the metastatic setting, representing a more heavily pretreated population. These findings highlight the importance of considering treatment exposure when interpreting real-world data alongside clinical trial results.

Objective response rates (ORR) and rwRR varied across regimens and subtypes, reflecting differences in how tumor response is assessed in routine practice, where evaluations rely on clinician judgment rather than standardized RECIST criteria28. Consistent with other real-world estimates14,17, tumor response data were moderately to highly incomplete, limiting comparability with trial-based ORR estimates. An Italian multicenter study reported an rwRR of 34.6% for palbociclib plus endocrine therapy, consistent with our HR+/HER2- cohort29. This alignment with published literature, coupled with differences from trial outcomes, highlights that tumor-response measurement may vary substantially outside controlled settings30. Given differences in assessment practices and data completeness, interpretation of rwRR should acknowledge that bias may be a factor in interpretations of these results.

Our findings are consistent with other real-world studies of mBC treated with similar therapies. For example, a US single-institution study reported rwPFS of 5 months (95% CI 4.4–5.9) among a fulvestrant-only population and 10 months (95% CI 8.4–11.8) among a fulvestrant + palbociclib population, which is similar to our findings within these populations31. A recent Danish EHR-based analysis of mTNBC patients reported a median rwOS of 14.2 months for recurrent cases and 8.3 months for de novo metastatic cases, comparable to our mTNBC chemotherapy cohort32. Furthermore, the rwPFS ranged from 4.9 months in first-line to 2.1 months in third-line therapy is consistent with our cohort’s rwPFS estimates, also consistent with our study. Additionally, rwTTD and rwTTNT for paclitaxel-based therapy aligned with a 2018 US community oncology study (median rwTTD 2.8 months; rwTTNT 5.3 months)33.

Collectively, these findings indicate that real-world outcomes for HR+/HER2- mBC and mTNBC treated with regimens evaluated in clinical trials are largely consistent with trial results, though variations reflect differences in patient populations, treatment settings, and assessment methods. The inclusion of patients with broader ECOG scores and treatment histories reflects the heterogeneity of real-world practice, reinforcing the importance of RWE as a complement to randomized data. Future research should further explore line-specific analyses and include comparisons with more recent trials such as ASCENT (experimental arm), TROPICS-02, TROPION-02, and DESTINY-Breast studies to strengthen context and relevance25,34,35,36.

While our study did not formally compare characteristics and outcomes between patients in clinical trials and those in the real-world setting, we found that for several cohorts, when patients’ clinical and demographic characteristics, disease subtype, and treatment regimens were aligned, real-world endpoints were largely consistent with clinical trial results. However, for some cohorts, significant differences in clinical and demographic characteristics, as well as treatment regimens between the patients in the clinical trials and those treated in routine clinical practice, led to real-world endpoints varying from trial outcomes. These findings should be considered in context given the descriptive nature of the analysis.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The analysis was based on U.S.-based real-world data, which may not reflect the geographic diversity of patients enrolled in global clinical trials. For instance, PALOMA-3, PASO, and ASCENT recruited patients across multiple countries, where treatment practices, biomarker testing guidelines, and prognoses may differ significantly. These differences limit the generalizability of findings derived from a US-only dataset.

Treatment regimen selection in real-world settings may also be influenced by variations in clinical practice, access to therapies, and adherence to guidelines. Unlike clinical trials real-world populations are more heterogeneous, often including older patients with comorbidities and poorer prognoses, potentially impacting outcomes. Additionally, the absence of randomization and standardized visit schedules introduces potential bias and variability in outcome definitions.

Real-world data are also subject to missing or incomplete clinical information, such as BRCA or PD-L1 status, and the proportion of patients with available BRCA and PD-L1 testing found in this study is similar to other real-world studies37,38. As such, no formal adjustment for missing data, such as BRCA and PD-L1 testing, was undertaken, given that testing reflected real-world practices and was not assessed routinely during the study period. Similarly, real-world data lack standardized response assessments like RECIST v1.1. Data gaps may occur if patients transition to care settings outside the contributing data network. These factors collectively limit the comparability of real-world outcomes to those observed in clinical trials.

A key strength of this study is its use of an oncology-specific EHR dataset to evaluate real-world treatment effectiveness across multiple therapies in HER2-negative mBC subtypes. Unlike prior studies restricted to narrower patient populations or fewer treatment types, this analysis offers a more comprehensive view of clinical characteristics and outcomes. By applying a consistent methodology aligned with previous research on real-world data, the study enhances comparability and contributes evidence to the growing literature on the utility of EHRs in oncology research.

In conclusion, this study provides robust evidence on evaluating outcomes in patients with mBC treated in routine clinical practices. The consistency between some of the real-world data endpoints and trial endpoints is encouraging and supports the utility of real-world data to contextualize clinical trial findings. Continued advances in real-world data infrastructure, coupled with the integration of genomic and biomarker information, will further refine the understanding of treatment sequencing and resistance mechanisms. As analytic methods evolve, advanced modeling and predictive approaches will enhance the ability to inform clinical decision-making and improve patient outcomes in real-world oncology practice.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from ConcertAI, LLC but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data may however be available from ConcertAI, LLC upon reasonable request (https://www.concertai.com/contact-us/).

References

Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2024–2025. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/2024/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2024.pdf (2024).

Allison, K. H. et al. Estrogen and progesterone receptor testing in breast cancer: ASCO/CAP guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 1346–1366 (2020).

Howlader, N. et al. US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Instit. 106, dju055 (2014).

Anders, C. K., Zagar, T. M. & Carey, L. A. The management of early-stage and metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 27, 737–749 (2013).

Plasilova, M. L. et al. Features of triple-negative breast cancer: Analysis of 38,813 cases from the national cancer database. Medicine 95, e4614 (2016).

Amaro, C. P., Batra, A. & Lupichuk, S. First-line treatment with a cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor plus an aromatase inhibitor for metastatic breast cancer in Alberta. Curr. Oncol. 28, 2270–2280 (2021).

Sobhani, N. et al. Updates on the CDK4/6 inhibitory strategy and combinations in breast cancer. Cells 8, 321 (2019).

Roberts, P. J., Kumarasamy, V., Witkiewicz, A. K. & Knudsen, E. S. Chemotherapy and CDK4/6 inhibitors: Unexpected bedfellows. Mol. Cancer Ther. 19, 1575–1588 (2020).

21st Century Cures Act. (2016).

Merola, D. et al. The Aetion coalition to advance real-world evidence through randomized controlled trial emulation initiative: Oncology. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 113, 1217–1222 (2023).

Franklin, J. M. et al. Emulating randomized clinical trials with nonrandomized real-world evidence studies: First results from the RCT DUPLICATE initiative. Circulation 143, 1002–1013 (2021).

Stewart, M. et al. An exploratory analysis of real-world end points for assessing outcomes among immunotherapy-treated patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. JCO Clin. Cancer Inf. 1–15 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1200/CCI.18.00155.

Rivera, D. R. et al. The friends of cancer research real-world data collaboration pilot 2.0: Methodological recommendations from oncology case studies. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 111, 283–292 (2022).

McKelvey, B. A. et al. Evaluation of real-world tumor response derived from electronic health record data sources: A feasibility analysis in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy. JCO Clin. Cancer Inf. 8, e2400091. https://doi.org/10.1200/CCI.24.00091 (2024).

Xiong, X. et al. Breast cancer: Pathogenesis and treatments. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 10, 49 (2025).

Khozin, S. et al. Real-world evidence acceptability and use in breast cancer treatment decision-making in the United States: Call-to-action from a multidisciplinary think tank. Adv. Ther. 42, 2973–2987 (2025).

Cuyun Carter, G. et al. Real-world treatment patterns and outcomes of abemaciclib for the treatment of HR+, HER2- metastatic breast cancer. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 37, 1179–1187 (2021).

Patt, D. et al. Real-world treatment patterns and outcomes of palbociclib plus an aromatase inhibitor for metastatic breast cancer: Flatiron database analysis. Clin. Breast Cancer 22, 601–610 (2022).

Rugo, H. S. et al. Comparative overall survival of CDK4/6 inhibitors plus an aromatase inhibitor in HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer in the US real-world setting. ESMO Open 10, 104103 (2025).

Luhn, P. et al. Comparative effectiveness of first-line nab-paclitaxel versus paclitaxel monotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 8, 1173–1185 (2019).

Alaklabi, S. et al. Real-world clinical outcomes with sacituzumab govitecan in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. JCO Oncol. Pract. 21, 620–628 (2025).

von Elm, E. et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 335, 806–808 (2007).

Turner, N. C. et al. Overall survival with palbociclib and fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 1926–1936 (2018).

Decker, T. et al. A randomized phase II study of paclitaxel alone versus paclitaxel plus sorafenib in second- and third-line treatment of patients with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (PASO). BMC Cancer 17, 499 (2017).

Bardia, A. et al. Sacituzumab govitecan in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1529–1541 (2021).

Slipski, L., Dub, B., Yu, Y., Walker, M. & Natanzon, Y. RWD23 addition of open administrative claims significantly improves capture of mortality in electronic health record (EHR)—Focused real-world data (RWD). Value Health 27, S576 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Transparency and reproducibility of observational cohort studies using large healthcare databases. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 99, 325–332 (2016).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 11). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–247 (2009).

Palumbo, R. et al. Patterns of treatment and outcome of palbociclib plus endocrine therapy in hormone receptor-positive/HER2 receptor-negative metastatic breast cancer: A real-world multicentre Italian study. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 13, 1758835920987651 (2021).

Huang Bartlett, C. et al. Concordance of real-world versus conventional progression-free survival from a phase 3 trial of endocrine therapy as first-line treatment for metastatic breast cancer. PLoS ONE 15, e0227256 (2020).

Ha, M. J. et al. Palbociclib plus endocrine therapy significantly enhances overall survival of HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer patients compared to endocrine therapy alone in the second-line setting: A large institutional study. Int. J. Cancer 150, 2025–2037 (2022).

Celik, A. et al. Real-world survival and treatment regimens across first- to third-line treatment for advanced triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Basic Clin. Res. 17, 11782234231203292 (2023).

Mahtani, R. L. et al. Comparative effectiveness of early-line nab-paclitaxel vs. paclitaxel in patients with metastatic breast cancer: A US community-based real-world analysis. Cancer Manag. Res. 10, 249–256 (2018).

Dent, R. A. et al. TROPION-Breast02: Datopotamab deruxtecan for locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Future Oncol. 19, 2349–2359 (2023).

Modi, S. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2- low advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 9–20 (2022).

Rugo, H. S. et al. Overall survival with sacituzumab govitecan in hormone receptor-positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer (TROPiCS-02): A randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 402, 1423–1433 (2023).

Tolaney, S. M. et al. Understanding first-line treatment patterns and survival outcomes across sociodemographic groups of women with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer in the United States: A real-world study. ESMO Open 10, 105841 (2025).

Yadav, S. et al. Real-world germline BRCA testing, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor utilization, and survival outcomes in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol. 9, e2400814 (2025).

Funding

This study was supported by Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NS, PP, HL, YN, AT, and NF contributed to interpreting the data, conception, design, drafts, and main manuscript text. PA, DSG, PK, and LN contributed to interpreting the data, drafts, and main manuscript text. PP and HL contributed to the analysis of the data. All authors had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

N Sadetsky, L Nguyen, and A Taylor are full-time employees of Gilead Pharmaceuticals who, in the course of this employment, have received stock options exercisable for, and other stock awards of, ordinary shares of Gilead Pharmaceuticals, plc. P Prince is a full-time employee of Aetion, Inc. and holds stock options in Aetion. H Latimer is a prior employee of Aetion Inc. Y Natanzon is a full-time employee of ConcertAI, and holds stock options in ConcertAI. P Advaani receives from Gilead, Agendia, Astra Zeneca-DSI, Caris Life Sciences, Seagen/Pfizer, Atossa Therapeutics, Modulation Therapeutics, Biovica International, Loxo Lilly, Sermonix, Menarini Stemline, Elephas, and Puma, serves on the advisory board for Epic Sciences, Biovica International, Astra Zeneca, DSI, Hesian Labs, Elephas, Belay diagnostics, Merck, Astrin and Biosciences, and consults for GE Healthcare, AstraZeneca, MJH Lifesciences, Menarini Stemline, Iksuda Therapeutics, Breathe Biomedical, Guardant Health, and DSI. D. Smith-Gaziani is grant funded by Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation. N. Freemantle has received funding for consulting from Gilead, Sanofi Aventis, ALK Abello, Orion, Argenx. P. Kaufman has stock and other ownership interests from Amgen and Johnson&Johnson, has received honoraria from Lilly, Eisai, AstraZeneca, Sermonix Pharmaceuticals, and Genentech/Roche, has consulted for Polyphor, Genentech/Roche, Eisai, Lilly, Pfizer, Merck, AstraZeneca, Seagen, Sermonix Pharmaceuticals, and Gilead, and has received research funding from Eisai, Polyphor, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Zymeworks, and Sermonix Pharmaceuticals.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sadetsky, N., Prince, P., Latimer, H. et al. Exploration of real-world outcomes in patients with previously treated HR+/HER2- and triple negative metastatic breast cancer. Sci Rep 16, 3613 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33530-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33530-5