Abstract

Coal mining activities inevitably disturb the ecosystem and significantly affect the regional carbon pool and carbon storage function. In the context of global efforts to combat climate change and achieve carbon neutrality, accurately assessing the extent of coal mining’s disturbance to regional carbon stocks is particularly important. However, existing research generally fails to fully incorporate the severe surface disturbance caused by mining into land-use change prediction. At the same time, the reclamation of coal mining subsidence land is regarded as an important means to restore ecological functions. However, its potential for carbon storage and restoration, and its contribution to regional carbon neutrality goals, have not been fully discussed. Therefore, this study constructed the PIM-PLUS-InVEST model framework to assess how coal mining and land reclamation affect the carbon storage function of 51 coal mines in Shandong Province. Through quantitative analysis, the following conclusions are drawn: (1) Mining of 51 coal mines in Shandong Province will cause 861,073.81 Mg of carbon storage loss, while reclamation can recover 62.12% of carbon storage loss. (2) The main reason for the decrease in carbon storage is that a large amount of cultivated land area is transformed into water body due to coal mining. (3) The variations in carbon storage disruption caused by mining and reclamation differ significantly across coal mining areas in Shandong Province, with most highly disrupted coal mines concentrated in Jining City. This study provides a quantitative framework for assessing carbon storage and reclamation in coal-mining areas. Specifically, by quantifying the ‘ecological debt’ associated with mining activities, the findings offer a scientific reference for clarifying ecological restoration responsibilities and supporting sustainable land management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coal serves as a cornerstone of global energy supply and a fundamental industrial raw material. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), coal accounted for 26.5% of global primary energy consumption in 20231. However, coal extraction inevitably induces severe environmental disturbances, including surface subsidence and ecosystem degradation. In recent years, a growing body of literature has demonstrated that coal mining significantly compromises the carbon storage and storage capacity of mining areas2,3,4,5. These environmental challenges threaten the ecological security of mining areas and complicate land resource management. Land reclamation, as a critical measure to mitigate the environmental impacts of coal mining, can restore land-use functionality, improve the ecological environment, and enhance carbon storage capacity6,7. Specifically, in the context of China’s carbon neutrality and peak carbon strategy, the carbon storage enhancement potential of land reclamation in mining areas has become a focal area of research8. However, the dramatic land-use changes following mining and reclamation activities have varying impacts on carbon storage across different regions and mining sites9. Therefore, accurately assessing the impact of coal mining on carbon storage and predicting the restoration potential of reclamation measures to restore the carbon storage capacity of mining areas can not only identify high-risk regions for carbon loss but also provide scientific guidance for land reclamation.

The key to achieving the aforementioned assessment objectives lies in selecting an appropriate methodology for quantifying carbon stocks. Currently, a diverse framework for ecosystem carbon sink estimation has been established, primarily encompassing statistics-based IPCC inventory methods10 and empirical observation techniques, such as plot surveys and eddy covariance11. While these ground-based empirical methods offer irreplaceable advantages for revealing local mechanisms and providing high-precision ground-truth validation, their application to large-scale, long-term dynamic monitoring of mining areas is often constrained by high temporal costs, stringent observational requirements, and limitations in spatial extrapolation. In contrast, with advancements in earth observation technologies, ecological process simulations coupled with remote sensing data have become increasingly mainstream. Among these, the InVEST model has emerged as a preferred method for assessing ecosystem carbon storage dynamics12, distinguishing itself from simple productivity estimation tools through its superior capabilities in multi-scenario simulation, spatially explicit visualization, and parameter localization. Extensive literature confirms that incorporating locally calibrated carbon density coefficients enables the InVEST model to sensitively capture perturbations in regional carbon storage driven by land-use transitions. Furthermore, coupling it with land-use simulation models—such as CA-Markov13, CLUE-S14, and GeoSOS-FLUS15—enables robust future predictions. Consequently, this study employs this integrated modeling framework to quantitatively analyze the spatiotemporal evolution of carbon storage driven by coal mining and ecological reclamation, and to conduct predictive analysis.

Although considerable research has focused on the dynamic changes in carbon storage in mining areas16,17,18,19,20, limitations remain in assessing how coal mining and reclamation activities influence carbon storage. Changes in carbon storage in mining areas are influenced by multiple factors, including mining stages, reclamation measures, geological conditions, and policy interventions 3. Existing studies often fail to fully incorporate the severe surface disturbances caused by mining into land-use change predictions. Additionally, most studies focus on single mining sites, lacking systematic analyses of carbon storage dynamics at larger spatial scales. Therefore, it is necessary to integrate multiple models to conduct a comprehensive regional analysis and accurately evaluate the spatiotemporal effects of mining activities and reclamation efforts on carbon stocks.

The Probability Integral Method (PIM) is widely used to predict subsidence from underground coal mining and effectively models strata movement and surface deformation. This method provides a scientific foundation for disaster prevention, mitigation, and reclamation planning21,22,23. In this study, we propose a comprehensive evaluation framework based on the PIM-PLUS-INVEST model to systematically assess how mining activities and reclamation efforts influence carbon storage. This framework integrates PIM for precise prediction of subsidence areas, the PLUS model for dynamic simulation of land-use changes, and the InVEST model for quantitative estimation of changes in carbon storage. Aligning with the critical milestone of China’s ‘Carbon Peaking’ goal and the target completion year of the Special Plan for Comprehensive Governance of Coal Mining Subsidence Land in Shandong Province, this study comprehensively projects the spatiotemporal evolution of carbon storage in active coal mines across Shandong up to 2030 by using this framework, thereby providing a scientific basis for mining area land management and policy formulation.

The main objectives of this study are:

-

1.

To develop a comprehensive evaluation framework for predicting carbon storage dynamics in coal mining areas.

-

2.

To quantify the impacts of coal mining on carbon storage and identify the risks of carbon storage loss in mining areas.

-

3.

To assess the effectiveness of various reclamation measures in restoring carbon storage and provide scientific recommendations for future land reclamation policies in mining areas.

Materials and methods

Study area

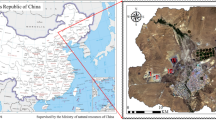

Shandong Province has a long history of coal mining, which has resulted in significant environmental challenges. To date, coal mining activities have resulted in over 1.2 million mu (approximately 80,000 ha) of subsidence-affected land, with an additional 30,000 mu (2000 ha) affected annually. The coal-mining areas of Shandong are predominantly characterized by farmland and are typical of high-water-table coal-agriculture composite zones. These areas face acute conflicts between coal mining, agricultural production, and residential land use. Extensive farmland and residential areas have been converted into water bodies due to ground subsidence caused by coal mining. Figure 1b illustrates the farmland in coal-mining areas prior to disturbance, highlighting the productive agricultural landscape. In contrast, Fig. 1c depicts the transformation of these areas into subsidence zones with water accumulation, showcasing the substantial changes in land-use types caused by mining-induced ground subsidence.

Looking ahead, 51 coal mines in Shandong Province are projected to remain operational by 2030. The majority of these mines are located in plain regions, with 28 mines in Jining City, 10 in Zaozhuang City, 6 in Heze City, and the remaining seven scattered across Dezhou, Tai’an, Wuhu, Jinan, and Yantai. The distribution of these coal mines is shown in Fig. 1a.

Data source

This study used LULC data from the Chinese Academy of Sciences for 2010 and 2020, with a spatial resolution of 30 m. Based on previous research, socio-environmental driving factors were selected to objectively and accurately simulate LULC changes24,25,26. The selected social driving factors include: GDP, population, distance to railways, and distance to roads. The selected natural environmental driving factors include soil texture, elevation, slope, annual precipitation, and annual mean temperature. All driving data were clipped to the administrative boundary of Shandong Province and resampled to 30 m.

The spatial resolution and data sources used to evaluate carbon storage and simulate LULC are presented in Table 1.

The data utilized in this study for coal mining analysis encompasses mining plans, mineral resource planning, and predictive parameters. Local coal mining enterprises supplied these datasets. Although actual mining operations may deviate from original design parameters due to geological variations or engineering adjustments, given that this study focuses on the macroscopic evolution of carbon storage at a regional scale, these localized engineering discrepancies fall within acceptable tolerance levels.

Research method

This study constructed a coupled PIM, PLUS, and InVEST model to evaluate changes in carbon storage and risks of carbon storage loss in 51 coal mines in Shandong Province under mining and land reclamation scenarios from 2010 to 2030. The PIM model was first used to predict the extent of mining-induced subsidence in coal mining areas by 2030 and classify the degree of land damage. Subsequently, the PLUS model simulated land-use changes in Shandong Province by 2030 using socioeconomic and climatic driving data, which were overlaid with land-damage classifications to establish three scenarios: Baseline Scenario, Mining Only Scenario, and Mining with Reclamation Scenario. Finally, the carbon density parameters were adjusted, and the InVEST model was applied to estimate carbon storage for each year under each scenario. The spatial and temporal changes in carbon storage were analyzed, and the carbon storage loss risks in mining areas were identified. The technical workflow is shown in Fig. 2.

Prediction of mining subsidence and definition of land damage severity

This study utilizes the Probability Integration Method (PIM), grounded in stochastic medium theory, to simulate mining-induced subsidence. PIM conceptualizes the mining area as a collection of countless micro-units, where the cumulative subsidence effect on the strata and surface is determined by aggregating the individual contributions of these micro-units27,28,29. The subsidence basin generated by mining for each surface unit is modeled as a normal distribution, reflecting the probability density function.

-

(1)

Expression of the Surface Unit Subsidence Basin:

\(W_{e} \left( x \right)\) represents the subsidence value at a specific point, while r denotes the main influence radius, which depends primarily on the mining depth of the unit and the main influence angle.; x corresponds to the horizontal coordinate of any surface point.

-

(2)

Calculation formula of surface movement and deformation in the whole basin.

Surface subsidence:

Ground tilt:

Surface curvature:

where: r is the main influence radius of any mining level, W is the maximum subsidence value of full mining on the surface, and D is the mining coal seam area; x and y are the relative coordinates of calculation points, considering the offset of in-flection points.

As a mature subsidence prediction model, the PIM has been widely validated across diverse geological conditions in China. Relevant studies demonstrate that PIM predictions are highly consistent with observed subsidence30. Furthermore, it serves as the standard methodology adopted in the formulation of the ‘Plan for Land Reclamation and Ecological Restoration in Mining Areas’. Consequently, this study used the PIM integrated into the MSPS31 software to predict mining-induced subsidence for 2030, based on mining plans, resource allocation data, and key predictive parameters provided by the respective coal mining enterprises.

Based on the underground diving level height of each city in Shandong Province and the relevant provisions of the Code for Comprehensive Land Improvement, the damage degree can be divided into three categories: light, moderate, and severe, as shown in Table 2.

Simulation of land use changes and scenario design using the PLUS model

The PLUS model, a grid-based cellular automata (CA) framework for simulating land use/land cover (LULC) changes at the patch scale, incorporates the Land Expansion Analysis Strategy (LEAS) and employs a CA approach using multi-type random patch seeds (CARS). This integration allows the PLUS model to analyze the driving factors of land expansion in detail and predict the evolution of LULC landscapes at the patch scale. Scholars have widely applied the PLUS model to simulate LULC changes at regional and urban scales, achieving satisfactory results32,33,34.

Given the dispersed distribution of coal mines in Shandong Province and the spatial continuity of socioeconomic driving factors, this study used LULC data from 2010 and 2020 to simulate the province’s LULC patterns in 2030. The LEAS module was used to analyze the impact of nine factors—including climate, population, GDP, and transportation—on LULC expansion, while the CARS module was used to predict LULC patterns in Shandong Province in 2030.

Based on the Code for comprehensive land improvement and the actual conditions of land reclamation in mining areas, three scenarios were designed for this study:

-

1.

Baseline scenario (bs): this scenario assumes no mining activities occur in the future, and the LEAS module solely determines LULC transition patterns.

-

2.

Mining with reclamation scenario (mrs): considering the predominance of farmland in Shandong Province’s mining areas and the need to ensure food security and protect farmers’ interests, this scenario follows a “benefit agriculture when possible” principle. Lightly damaged areas are restored to their original LULC type. In moderately damaged areas, regions outside buildings and water bodies are reclaimed for farmland. Severely damaged areas, due to the difficulty of restoration, are converted into water bodies.

-

3.

Mining only scenario (MOS): in this scenario, lightly damaged areas with minimal surface subsidence are assumed to recover to their original LULC type naturally. Moderately and severely damaged areas due to significant subsidence are converted into water bodies.

Carbon storage calculation based on the InVEST model

The carbon storage module in the InVEST model uses LULC data as the evaluation unit. It estimates carbon storage in terrestrial ecosystems, which primarily includes four basic carbon pools: aboveground biomass (from residual surface vegetation), belowground biomass (from plant roots), soil (organic and inorganic carbon), and dead organic matter (from litter and deadwood)35,36. The module assesses regional ecosystem carbon storage by utilizing LULC information and carbon density data.

where \({ }C_{above}\),\({ }C_{below}\),\({ }C_{soil}\),\({ }C_{dead}\) denote the carbon densities of aboveground biomass, belowground biomass, soil, and dead organic matter, respectively.

Numerous studies have identified a strong linear correlation between carbon density and climatic variables37,38,39. In 2018, Tang40 established a relationship model linking various climatic conditions to soil organic carbon, biomass carbon, and litter carbon, based on 14,371 observed data points. By integrating studies from Alam41 and Zhou42, the carbon density data provided by Fu9 for the Yanzhou mining area were adjusted using correction formulas (Eqs. 6–14). The average temperature and precipitation over the past decade in Shandong Province and the Yanzhou mining area were 13.99 °C and 14.82 °C, and 774.42 mm and 829.40 mm, respectively.

Regression models accounting for temperature (applied when mean annual precipitation exceeds 400 mm):

Regression models accounting for precipitation (applied when mean annual temperature exceeds 10°C):

where C_ST、C_SP are the fitted values of soil carbon density based on mat and map, C_BT、C_BP are the fitted values of biomass carbon density based on mat and map, and C_DT、C_DP are the fitted values of litter carbon density based on mat and map.

Correction coefficient calculation models:

In this context, \(K_{SP}\) and \(K_{ST}\) represent the adjustment factors for soil carbon density, influenced by precipitation and temperature. Similarly, \(K_{BP}\) and \(K_{BT}\) correspond to biomass carbon density, while \(K_{DP}\) and \(K_{DT}\) pertain to litter carbon density. The overall correction coefficients for soil, biomass, and litter carbon densities are represented by \({K}_{S}\), \({K}_{B}\), and \({K}_{D}\), respectively, as shown in Table 3.

Using the correction formulas, the carbon density of various land types in Shandong Province was determined.

Defining carbon storage risk loss in coal mines

To better evaluate how carbon storage responds to coal mining and reclamation, two indices were developed to capture changes in the ability of mining areas to sequester carbon following these activities.

Carbon Storage Loss from Mining (CLM):

Carbon Storage Gain from Reclamation (CGR):

where \(C_{BS}\)、\(C_{MOS}\) and \(C_{MRS}\) represent the carbon storage under the BS, MOS, and MRS scenarios, respectively, and i denotes an individual mining area.

We divide the CLM index into three grades to characterize the impact of coal mining on carbon loss: coal mines with CLM greater than− 5% are defined as “Low Carbon Loss from Mining (Low CLM)”, coal mines with CLM between− 5% and− 10% are defined as “Moderate Carbon Loss from Mining (Moderate CLM)”, and coal mines with CLM less than− 10% are defined as “High Carbon Loss from Mining (High CLM)”.

Similarly, the range of CGR index is also divided into three levels to characterize the effect of reclamation on carbon returns: coal mines with CGR less than 5% are defined as “Low Carbon Gain from Reclamation (Low CGR)”, coal mines with CGR between 5 and 10% are defined as “Moderate Carbon Gain from Reclamation (Moderate CGR)”, and coal mines with CGR greater than 10% are defined as “High Carbon Gain from Reclamation (High CGR)”.

Results

Subsidence prediction results

Using PIM combined with local underground phreatic water-level data, we predicted the extent and severity of land damage from coal mining in 51 coal mines in Shandong Province in 2030, and the results are shown in Fig. 3. In 2030, 51 coal mines in Shandong Province damaged a total of 31,356.62 ha of land, including 16,145.99 ha of light damage, 10,591.58 ha of moderate damage and 4619.05 ha of severe damage. Among them, the most damaged land in Jining coal mine is 18,175.69 ha, accounting for 57.96% of the damaged land in Shandong Province in 2030. Jining City accounts for the most significant proportions of lightly, moderately, and severely damaged land, at 56%, 61%, and 60%, respectively. It is worth noting that in 2030, the severely damaged area in Zaozhuang City was only 39.58 ha, accounting for only 1% of the total severely damaged area. Based on the distribution of damaged land in each city, Jining’s is mainly in the central and southern parts; Zaozhuang City’s is relatively concentrated, all in the southwest; Heze City’s is mainly in the eastern region.

LULC prediction results

Based on the LULC2010 and LULC2020 data (Fig. 5), cultivated land accounted for more than 60% of the total area across the 51 coal mining areas in both 2010 and 2020. However, over the decade, the cultivated land area decreased by 3,041.18 ha. Meanwhile, the waterbody area increased from 27,850.67 ha to 28,656.98 ha, representing approximately a 5% growth. Additionally, the area of built-up land rose from 41,423.07 ha to 43,650.52 ha. Since all 51 coal mining areas are located in regions with high groundwater levels, mining-induced surface subsidence and water accumulation have transformed other land types into waterbodies. The LULC changes observed between 2010 and 2020 clearly reflect this trend.

Using the PIM and PLUS models, we projected the LULC types for the 51 operational coal mines in Shandong Province in 2030 under three scenarios. The first scenario, BS, assumes no future mining activities and that land-use transitions are determined entirely by the LEAS module of the PLUS model. The second scenario, MRS, involves restoring damaged cultivated land for reuse. The third scenario, MOS, assumes no active human intervention for land restoration. The land-use results under these three scenarios are shown in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5.

Under MOS, compared to BS, the waterbody area increased by 12,179.28 ha (a 41% rise), while the cultivated land area decreased by 9,369.94 ha. This highlights the severe threat that mining activities pose to cultivated land resources, jeopardizing the nation’s food security and exacerbating human-land-energy conflicts in mining areas.

Land reclamation under MRS significantly mitigates these conflicts. Compared to BS, the waterbody area decreased by 8,641.32 ha, while the areas of cultivated land and built-up land increased by 6,804.36 ha and 1,836.95 ha, respectively. Reclamation efforts restored 72.12% of the lost cultivated land area, demonstrating the critical role of land reclamation in safeguarding cultivated land resources and ensuring food security.

Carbon storage projections

Between 2010 and 2020, the carbon storage of 51 coal mines in Shandong Province declined from 13,909,094.27 Mg to 13,704,753 Mg. Driven by urban expansion, it is anticipated that by 2030, carbon storage will further decrease to 13,486,451.26 Mg, even under the Baseline Scenario (BS). In the Mining Only (MOS) scenario, carbon storage decreases further to 12,625,377.45 Mg, representing a 6% reduction compared to the BS scenario. This highlights the significant damage that coal mining inflicts on the carbon storage capacity of mining areas. However, under the Reclamation (MRS) scenario, carbon storage increases by 586,529.63 Mg compared to the MOS scenario, re-covering 62.12% of the carbon storage loss. This demonstrates that land reclamation effectively restores carbon storage and enhances storage capacity in mining areas.

Regional analysis reveals notable spatial and temporal variations in carbon storage across coal mines (as shown in Fig. 6). In Jining City, the carbon storage of its 28 coal mines decreased from 6,463,827.21 Mg in 2010 to 6,353,815.72 Mg in 2020 and further to 6,259,029.48 Mg under the BS scenario by 2030. Under the MOS scenario, carbon storage decreased by 454,013.88 Mg compared to the BS scenario, a 7.25% reduction. If reclamation measures are implemented, the MRS scenario increases carbon storage by 313,993.92 Mg compared to the MOS scenario, significantly improving carbon storage. Dongtan coal mine stands out, with mining activities causing a loss of 86,076.18 Mg in carbon storage, while reclamation restores 53,166.96 Mg.

Among the 10 coal mines in Zaozhuang City, Jiangzhuang coal mine experienced a carbon storage loss of 26,891.68 Mg due to mining, with reclamation restoring 24,542.56 Mg. In Heze City, where there are six coal mines, Xinjulong coal mine suffered a loss of 116,341.05 Mg in carbon storage from mining, but reclamation restored 56,320.17 Mg. In other cities, Jiangjia coal mine was the most affected, with mining causing a loss of 18,652.31 Mg in carbon storage, and reclamation recovering 13,363.83 Mg.

These findings underscore that land reclamation is an effective strategy for addressing carbon storage loss caused by coal mining.

We mapped the carbon storage change rates for 2010–2020 and 2020–BS scenarios by city (as shown in Fig. 7), visually presenting the trends in carbon storage changes across different coal mines.

Among the 28 coal mines in Jining City, carbon storage decreased for most mines between 2010 and 2020, except for Xuzhuang, Daizhuangsheng, and Hegang, which experienced slight increases. The most significant declines were observed in Jininger and Xinglong coal mines, with rates of − 8.87% and − 5.95%, respectively. From 2020 to the BS scenario, most coal mines continued to show declining carbon storage, except for Fucun and Gaozhuang, which saw slight increases. Dongtan coal mine recorded the most significant decline, with a change rate of − 3.98%.

In Zaozhuang City, the carbon storage change rates for its 10 coal mines remained within 2% during both time periods. In Heze City, among its six coal mines, only Zhangji showed a slight increase in carbon storage between 2010 and 2020, while others declined, with Guocun mine experiencing the most significant reduction at − 5.11%. Between 2020 and the BS scenario, the Xinjulong mine showed the largest decline of − 3.23%.

Among cities with six coal mines, Sunzhuang exhibited the most significant changes, with a decrease in carbon storage of − 2.79% from 2010 to 2020, followed by a further decline of − 5.76% from 2020 to the BS scenario.

These data highlight apparent spatial and temporal differences in the rates of change in carbon storage across coal mines in different cities.

Carbon loss and gain risk results from mining and reclamation

To better quantify how coal mining and reclamation influence the carbon storage of individual mines, this study introduced the Carbon Loss from Mining (CLM) Index and the Carbon Gain from Reclamation (CGR) Index (see Section "Defining Carbon Storage Risk Loss in Coal Mines"). A smaller CLM indicates a more severe negative impact of coal mining on land carbon storage capacity, while a larger CGR reflects a more significant recovery effect of reclamation on land carbon storage. The spatial variations in CLM and CGR for 51 coal mines across Shandong Province are illustrated by city (see Fig. 8).

In Jining City, 13 coal mines exhibited CLM values below -10%, among which Dongtan, Guozhuang, and Baodian mines had CLM values below − 20% at − 20.86%, − 24.14%, and − 29.25%, respectively. Seven mines showed CGR values above 10%, with Baodian mine having the highest CGR at 21.00%.

In Zaozhuang City, two coal mines had CLM values below -10%: Wangchao (− 14.23%) and Liuzhuang (− 10.20%). Four mines had CGR values above 10%, with the Wangchao mine recording the highest at 16.45%. Notably, Quanshang and Jinda mines had both CLM and CGR values of 0 due to their minimally damaged land naturally reverting to its original state.

In Heze City, only Zhangji and Xinjulong mines had CLM values slightly below -10%, while only Zhangji mine exhibited a CGR greater than 10%.

For coal mines in other cities, CLM values were all above -10%, and CGR values were all below 10%. These results demonstrate significant regional and mine-specific differences in the impacts of mining and reclamation on carbon storage.

To better illustrate how mining and reclamation influence carbon stocks, we classified CLM and CGR (see Defining carbon storage risk loss in coal mines). As shown in Table 4, 17 High CLM coal mines among the 51 coal mines in Shandong Province are located in Jining City, accounting for about 76%. There are 12 coal mines in High CGR, of which seven are located in Jining City, indicating that Jining Coal Mine should pay close attention to investment in future mining and reclamation plans.

Discussion

The impact of coal mining on carbon storage

The results indicate a significant negative impact of coal mining on carbon storage in mining areas. Under the MOS scenario, carbon storage was reduced by 6.38% compared to the BS scenario, confirming that mining activities significantly reduce the land’s carbon storage capacity. This outcome reflects the characteristic shift in LULC toward waterbodies caused by surface subsidence in high groundwater mining areas, with cultivated land suffering the most severe damage. This poses a direct threat to national food security and carbon neutrality goals. Additionally, the CLM values across different regions and mines showed significant variation. For instance, coal mines in Jining City generally exhibited higher CLM values, indicating a positive correlation between the degree of land carbon storage loss and mining intensity. These findings suggest that high-risk mining areas should be prioritized and that differentiated mitigation measures should be implemented.

The recovery effect of land reclamation on carbon storage

The study reveals the critical role of land reclamation in enhancing carbon storage in mining areas. Under the MRS scenario, compared to the MOS scenario, 72.12% of the lost cultivated land was restored, increasing carbon storage by 586,529.63 Mg. This demonstrates that scientific reclamation not only effectively alleviates human-land-energy conflicts in mining areas but also contributes to carbon-neutrality goals. The CGR grading results further indicate that the reclamation effect depends on the degree of damage and the reclamation strategy. For example, Dongtan coal mine in Jining City achieved the highest carbon storage recovery through reclamation, highlighting the significant benefits of precise reclamation measures in areas with high-intensity mining.

Regional differences in Shandong’s coal mining areas

The analysis of CLM and CGR indices revealed substantial differences in carbon storage losses from mining and carbon gains from reclamation across coal mines in different regions. Coal mines in Jining City generally had lower CLM values and higher reclamation potential, indicating that this region should be a priority for future ecological restoration and carbon storage recovery efforts. In contrast, coal mines in Zaozhuang and Heze cities exhibited relatively low CLM values and smaller reclamation carbon gains due to their stronger natural recovery capacities. Notably, in some lightly damaged coal mines in Zaozhuang and Heze, CGR values were close to zero. For these areas, future reclamation efforts should focus on enhancing land ecological functions and carbon storage capacity rather than relying solely on artificial reclamation.

Pathways for carbon asset valorization and sustainable management

According to the ‘Polluter Pays Principle’ established by the OECD43 and the Measures for the Administration of Mine Geological Environment Restoration Fund implemented in China (2017), coal mining enterprises incur substantial reclamation costs through mandatory bonds or dedicated funds, creating significant financial pressure. However, the simulation results of this study confirm that scientific land reclamation measures can significantly enhance carbon storage in mining soils and vegetation. This finding implies that reclaimed land is not merely a financial liability, but can be transformed into valuable ‘carbon sink assets’.

Looking forward, integrating these reclaimed carbon sinks into the carbon trading system offers a transformative solution. By monetizing additional carbon storage through Certified Emission Reduction credits, enterprises can generate economic returns44. This market-based mechanism provides essential funding to offset reclamation costs, effectively creating a virtuous green cycle of ‘coal production—ecological restoration—carbon trading—capital reflux’. Ultimately, this approach fosters a sustainable balance between economic viability, ecological protection, and energy security.

Policy recommendations and regional development

Based on the analysis above, the following policy recommendations are proposed:

-

1.

rioritized focus on coal mines in jining city: given the high levels of carbon storage loss and significant reclamation potential in Jining City’s coal mines, future mining and reclamation plans should prioritize investments in this region to enhance ecological restoration capabilities. Especially in high groundwater areas, precise reclamation measures can effectively restore carbon storage and mitigate the negative impacts of coal mining on land-based carbon storage.

-

2.

Differentiated reclamation strategies for other cities: in regions like Zaozhuang and Heze, where coal mining has a smaller impact on carbon storage and natural recovery capacity is higher, ecological restoration measures should be prioritized. Reclamation strategies should be optimized by considering land type and natural recovery capacity45.

-

3.

Inter-regional collaborative reclamation: for Shandong Province’s overall coal mine reclamation efforts, it is crucial to account for regional differences and develop targeted reclamation measures to maximize the recovery of land carbon storage and ecological functions. Policies should integrate local LULC conditions, resource availability, and climate characteristics to implement region-specific and tiered reclamation plans.

Applicability and limitations

Research on carbon storage in coal mining areas is abundant. Some scholars evaluate carbon storage levels in mining areas through field data collection46,47, but this approach is time-consuming and unsuitable for large-scale assessments. Others use remote sensing data such as NPP48,49, Landsat50,51,52, or LiDAR53,54 to estimate carbon storage. However, these methods only allow for the study of historical and current scenarios, lacking the capability to assess future carbon storage55. In comparison, the methodology proposed in this study is better suited to accurately assess the future distribution of carbon storage at a large scale in mining areas.

Despite employing multi-model coupling to assess the impacts of coal mining and reclamation, this study has some limitations. For instance, the PIM model’s predictions rely heavily on the accuracy of mining plans, which may introduce biases. Additionally, while InVEST was used to evaluate carbon storage, the carbon densities for different LULC types were fixed in the model. Although climate data were used to adjust carbon densities across mining areas, variations within the same land type were not accounted for. Future research should combine actual survey data and sampling data to refine model parameters further. Moreover, exploring the effects of different reclamation approaches, such as vegetation restoration and ecological agriculture, would provide more detailed guidance for land reclamation policies.

Conclusion

This study utilized the PIM-PLUS-InVEST framework to project carbon storage evolution across 51 coal mines in Shandong by 2030. Using CLM and CGR indices, the results confirm that while mining subsidence drives significant carbon loss, scientific reclamation can recover approximately 62% of this storage, effectively reversing the carbon source trend.

Technically, this framework supports differentiated, site-specific management by revealing regional disparities in recovery potential. Critically, by quantifying storage capacity, the study demonstrates the feasibility of transforming reclaimed land into a carbon storage asset, thereby establishing a robust data foundation for future carbon asset accounting.

Future research should integrate field monitoring data to calibrate model parameters, addressing limitations associated with data biases. Additionally, refining dynamic carbon density mechanisms under varying climate scenarios will further enhance the robustness of carbon neutrality strategies in mining areas.

Data availability

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Liu, D. International Energy Agency (IEA) 830–836 (Springer, 2023).

Hu, Z. Q. et al. Farmland damage and its impact on the overlapped areas of cropland and coal resources in the eastern plains of China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 86, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2014.01.002 (2014).

Hu, Z. & Xiao, W. Optimization of concurrent mining and reclamation plans for single coal seam: A case study in northern Anhui China. Environ. Earth Sci. 68, 1247–1254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-012-1822-9 (2013).

Palmer, M. A. et al. Mountaintop mining consequences. Science 327(5962), 148–149 (2010).

Liu, J. et al. Continuous chamber gangue storage for sustainable mining in coal mines : Principles, methods, and environmental benefits. Sustainability 17(15), 16 (2025).

Zhanjun, X., Huping, H. & Shaoliang, Z. Study on the measure of ecological loss based on the net primary productivity in coal mining. Transac. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 28, 232–240 (2012).

Hodačová, D. & Prach, K. Spoil heaps from brown coal mining: Technical reclamation versus spontaneous revegetation. Restor. Ecol. 11, 385–391 (2003).

Yang, B., Bai, Z., Fu, S. & Cao, Y. Division of carbon sink functional areas and path to carbon neutrality in coal mines. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-022-00507-y (2022).

Fu, Y. H. et al. Dynamics of carbon storage driven by land use/land cover transformation in coal mining areas with a high groundwater table: A case study of Yanzhou Coal Mine China. Environ. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.118392 (2024).

Nelson, E. et al. Modeling multiple ecosystem services, biodiversity conservation, commodity production, and tradeoffs at landscape scales. Front. Ecol. Environ. 7, 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1890/080023 (2009).

Baldocchi, D. D. Assessing the eddy covariance technique for evaluating carbon dioxide exchange rates of ecosystems: Past, present and future. Glob. Change Biol. 9(4), 479–492 (2003).

Kohestani, N. et al. Spatiotemporal modeling of the value of carbon sequestration under changing land use/land cover using InVEST model: A case study of Nour-rud Watershed, Northern Iran. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26(6), 14477–14505 (2024).

Sang, L., Zhang, C., Yang, J., Zhu, D. & Yun, W. Simulation of land use spatial pattern of towns and villages based on CA-Markov model. Math. Comput. Model. 54, 938–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcm.2010.11.019 (2011).

Verburg, P. H. et al. Modeling the spatial dynamics of regional land use: The CLUE-S model. Environ. Manag. 30, 391–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-002-2630-x (2002).

Xiao, Y., Huang, M., Xie, G. & Zhen, L. Evaluating the impacts of land use change on ecosystem service values under multiple scenarios in the Hunshandake region of China. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158067 (2022).

Chen, F. et al. Assessing carbon sink capacity in coal mining areas: A case study from Taiyuan City China. Atmosphere https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15070765 (2024).

Yang, G., Su, C., Zhang, H., Zhang, X. & Liu, Y. Tree-level landscape transitions and changes in carbon storage throughout the mine life cycle. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166896 (2023).

Li, G. et al. Innovation for sustainable mining: Integrated planning of underground coal mining and mine reclamation. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131522 (2022).

Liao, Q., Liu, X. & Xiao, M. Ecological restoration and carbon sequestration regulation of mining areas-a case study of Huangshi City. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074175 (2022).

Hou, H., Zhang, S., Ding, Z., Huang, A. & Tian, Y. Spatiotemporal dynamics of carbon storage in terrestrial ecosystem vegetation in the Xuzhou coal mining area China. Environ. Earth Sci. 74, 1657–1669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-015-4171-7 (2015).

Liu, H. et al. A boundary model of terrain reconstruction in a coal-mining subsidence waterlogged area. Environ. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-021-09508-7 (2021).

Zhou, D., Wu, K., Miao, X. & Li, L. Combined prediction model for mining subsidence in coal mining areas covered with thick alluvial soil layer. Bull. Eng. Geol. Env. 77, 283–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-016-0961-8 (2018).

Yang, Z. F. et al. InSAR-based model parameter estimation of probability integral method and its application for predicting mining-induced horizontal and vertical displacements. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 54, 4818–4832. https://doi.org/10.1109/tgrs.2016.2551779 (2016).

Wu, Q., Wang, L., Wang, T., Ruan, Z. & Du, P. Spatial-temporal evolution analysis of multi-scenario land use and carbon storage based on PLUS-InVEST model: A case study in Dalian China. Ecol. Indic. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112448 (2024).

Yu, Y. et al. Carbon storage simulation and analysis in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region based on CA-plus model under dual-carbon background. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk https://doi.org/10.1080/19475705.2023.2173661 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Spatial-temporal evolution and prediction of carbon storage: An integrated framework based on the MOP-PLUS-InVEST model and an applied case study in Hangzhou East China. Land https://doi.org/10.3390/land11122213 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. An efficient and fully refined deformation extraction method for deriving mining-induced subsidence by the joint of probability integral method and SBAS-InSAR. Ieee Transac. Geosci. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.1109/tgrs.2023.3279390 (2023).

Zhu, C. et al. Retrieval and prediction of three-dimensional dis-placements by combining the DInSAR and probability integral method in a mining area. IEEE J. Select. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 13, 1206–1217. https://doi.org/10.1109/jstars.2020.2978288 (2020).

Li, P., Tan, Z. & Yan, L. A shaft pillar mining subsidence calculation using both probability integral method and numerical simulation. Cmes-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 117, 231–249. https://doi.org/10.31614/cmes.2018.02573 (2018).

Yang, Z. et al. An InSAR-based temporal probability integral method and its application for predicting mining-induced dynamic deformations and assessing progressive damage to surface buildings. IEEE J. Select. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sensing 11(2), 472–484 (2018).

Zhao, H. et al. Initial digging depth of deeping-digging and shallow-filling reclamation based on earthwork balance: A case study of collapse in Zhaogu mining area. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 48(06), 1375–1382 (2019).

Hou, Y. & Wu, J. Land-use and habitat quality prediction in the Fen River Basin based on PLUS and InVEST models. Front. Environ. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2024.1386549 (2024).

Han, Z. et al. Dynamic simulation of land use and habitat quality assessment in baiyangdian basin using the SD-PLUS coupled model. Water https://doi.org/10.3390/w16050678 (2024).

Guo, W. et al. A new assessment framework to forecast land use and carbon storage under different SSP-RCP scenarios in China. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169088 (2024).

Cong, W., Sun, X., Guo, H. & Shan, R. Comparison of the SWAT and InVEST models to determine hydrological ecosystem service spatial patterns, priorities and trade-offs in a complex basin. Ecol. Indic. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106089 (2020).

Jacobs, A. D. & Hitch, M. Experimental mineral carbonation : approaches to accelerate CO 2 sequestration in mine waste materials. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 25(4), 321–331 (2011).

Di Marco, M., Watson, J. E. M., Currie, D. J., Possingham, H. P. & Venter, O. The extent and predictability of the biodiversity-carbon correlation. Ecol. Lett. 21, 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12903 (2018).

Dai, L. et al. Effects of climate change on biomass carbon sequestration in old-growth forest ecosystems on Changbai Mountain in Northeast China. For. Ecol. Manage. 300, 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2012.06.046 (2013).

Wang, D.-D. et al. Scale effect of climate and soil texture on soil organic carbon in the uplands of Northeast China. Pedosphere 20, 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1002-0160(10)60042-2 (2010).

Tang, X. et al. Carbon pools in China’s terrestrial ecosystems: New estimates based on an intensive field survey. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 4021–4026. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1700291115 (2018).

Alam, S. A., Starr, M. & Clark, B. J. F. Tree biomass and soil organic carbon densities across the Sudanese woodland savannah: A regional carbon sequestration study. J. Arid Environ. 89, 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2012.10.002 (2013).

Zhou, J. et al. Impacts of ecological restoration projects on the ecosystem carbon storage of inland river basin in arid area China. Ecol. Indic. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106803 (2020).

Koh, N. S., Hahn, T. & Ituarte-Lima, C. Safeguards for enhancing ecological compensation in Sweden. Land Use Policy 64, 186–199 (2017).

Yuan, Y. et al. Low-carbon strategies considering corporate environmental responsibility: Based on carbon trading and carbon reduction technology investment. Sustainability 14(11), 18 (2022).

Amaro, S. L. et al. Multi-criteria decision analysis for evaluating transitional and post-mining options—An innovative perspective from the EIT ReviRIS Project[J]. Sustainability 14(4), 13 (2022).

Xu, Z. et al. Effect of underground coal mining on the regional soil organic carbon pool in farmland in a mining subsidence area. Sustainability https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184961 (2019).

Qu, J.; Zhang, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ieee. Analysis on distribution characteristics of soil carbon pool in mining subsidence wetlands. In Proc. of the 5th International Conference on Measuring Technology and Mechatronics Automation (ICMTMA), Hong Kong, PEOPLES R CHINA, 2013,Jan 16–17, 2013; pp. 266–271.

Ranjan, A. K., Parida, B. R., Dash, J. & Gorai, A. K. Evaluating impacts of opencast stone mining on vegetation primary production and transpiration over rajmahal hills. Sustainability https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108005 (2023).

Huang, Y., Tian, F., Wang, Y., Wang, M. & Hu, Z. Effect of coal mining on vegetation disturbance and associated carbon loss. Environ. Earth Sci. 73, 2329–2342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-014-3584-z (2015).

Singh, N.J.; Ray, L.I.P.; Sanjay, S.; Singh, A.K. Prediction of Soil Organic Carbon in Unscientific Coal Mining Area Using Landsat Auxiliary Data. In Proc. of the International Virtual Conference on Developments and Applications of Geomatics (DEVA), Electr Network, 2024,Aug 29–31, 2022; pp. 427–439.

Myroniuk, V. et al. Tracking Rates Of Forest Disturbance And Associated Carbon Loss In Areas Of Illegal Amber Mining in Ukraine using landsat time series. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12142235 (2020).

Kazar, S. A. & Warner, T. A. Assessment of carbon storage and biomass on minelands reclaimed to grassland environments using Landsat spectral indices. J. Appl. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.Jrs.7.073583 (2013).

Csillik, O. & Asner, G. P. Aboveground carbon emissions from gold mining in the Peruvian amazon. Environ. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab639c (2020).

Czarnogorska, M., Samsonov, S. V. & White, D. J. Airborne and spaceborne remote sensing characterization for aquistore carbon capture and storage site. Can. J. Remote. Sens. 42, 274–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/07038992.2016.1171131 (2016).

Jacobs, A. et al. Mineral carbonation potential ( MCP ) of mine waste material : Derivation of an MCP parameter. Minerals 13(9), 21 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Research on Carbon Reduction and Carbon Sink Enhancement Development Models for Rural Tourism Under the ‘Dual Carbon’ Goals, grant number QJKC-2022070 and the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 52474198)

Funding

This research was funded by Research on Carbon Reduction and Carbon Sink Enhancement Development Models for Rural Tourism Under the ‘Dual Carbon’ Goals, grant number QJKC-2022070 and the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 52474198).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and Y.L.; Methodology, X.W.; Software, Y.G.; Validation, X.W., Y.G. and K.H.; Formal analysis, X.W.; Investigation, Y.G.; Resources, X.W.; Data curation, X.W.; Writ-ing—original draft preparation, X.W.; Writing—review and editing, Y.L. and K.H.; Visualization, X.W.; Supervision, Y.L.; Project administration, Y.L.; Funding acquisition, Y.L. and X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Liang, Y., Geng, Y. et al. Predicting carbon storage changes in coal mining regions: a remote sensing approach based on the PIM-PLUS-INVEST model. Sci Rep 16, 3568 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33572-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33572-9