Abstract

Urban green spaces are vital carbon sinks and play a central role in low-carbon city development. However, traditional evaluations often focus on outcome indicators such as green space area and greening rate, neglecting the governance performance within the construction process. To bridge this gap, we introduce a five-process PDCOA (Plan–Do–Check–Outcome–Act) framework, applying Python-based web scraping and automated text mining to conduct an integrated assessment of 296 prefecture-level cities in China. Our results reveal a national average score of 44.10, with scores ranging from 10.42 to 92.81 (Beijing). Significant regional disparities emerge, with East China (mean score: 50.08) leading the nation, while regions like Southern China (38.25) lag considerably. The process evaluation uncovers a systemic imbalance: while cities perform relatively well in the P (59.81) and D (57.60) processes, they falter in the C (38.94), A (36.10) and O (31.21) processes. This study demonstrates that effective governance, not resource endowment, determines success in low-carbon green space development. It underscores the urgent need to shift from outcome-only metrics to process-driven continuous improvement, prioritizing adaptive feedback mechanisms and differentiated spatial strategies to strengthen urban green space governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The climate crisis driven by massive carbon emissions has become a critical threat to global environmental sustainability and public health1,2. Cities, as hubs of energy consumption and economic activity, account for nearly 75% of global carbon emissions3,4. Rising temperatures further intensify the urban heat island effect, aggravating imbalances in surface carbon cycles1,5. Building low-carbon cities is therefore a key pathway to mitigating climate risks and advancing sustainable development6. A measurable, diagnosable, and feedback-enabled assessment framework is essential for implementing effective low-carbon strategies7.

Reducing emissions and enhancing carbon sinks are two core strategies for low-carbon city development8. Urban green spaces are particularly important, as they serve as efficient carbon sinks9. Through plant photosynthesis, green spaces absorb atmospheric CO₂ and store it in vegetation and soil, thereby lowering urban carbon concentrations10. Different types of green spaces vary in their carbon sequestration potential, but their high plant diversity often results in greater above-ground carbon density compared with natural forests11,12. In addition, urban green spaces can mitigate heat island effects, reduce energy demand, and indirectly lower emissions13,14. Expanding the scale and distribution of urban greenery is thus widely regarded as an effective means to strengthen urban carbon sinks15,16. Consequently, enhancing the role of urban green spaces in carbon sequestration has been recognized as a cornerstone of global sustainable urban development17,18,19.

In China, urban areas account for about 90% of total carbon emissions20. Guided by the national “dual carbon” goals, central and local governments have introduced policies to expand urban green space development21,22. This growth reflects both environmental goals23, and the reality that local governments often use green spaces to drive real estate development and urban expansion24,25. Despite this progress, research on urban green space carbon sink development faces two major shortcomings.

The first shortcoming is its outcome-oriented perspective and neglect of processes. Most studies rely on green coverage rates26 or total green space area27,28 as core indicators. For example, in Dhaka, Bangladesh, green space is limited (~ 2%) and concentrated in central thanas such as Ramna, leaving outer, densely populated districts largely underserved29. Martin, et al.30 reported that about 80% of 96 C40 cities achieved the benchmark of 30% green coverage, while Schumacher31 found significant variation in green space proportions (2%–18%) across 30 medium-sized European cities. In China, Li, et al.32 found that Nanjing ranked highest in green coverage among 58 major cities, with higher greening levels concentrated in eastern and southern regions. Xu, et al.21 similarly identified spatial clustering of green space in northeastern China, the Shandong Peninsula, the Yangtze River Delta, the Pearl River Delta, and Chongqing. While ethnic differences are not a primary driver of spatial heterogeneity, factors such as economic development, income, natural endowments, and land supply significantly shape green space distribution21,27,33,34. These studies deepen the understanding of spatial differences and agglomeration patterns in green space development. However, as Yu and Zhang35 and Khanna, et al.36 emphasized, outcome-only evaluations fail to capture the governance challenges and monitoring gaps in the development process. This limitation is not unique to China. In international policy evaluation, the “implementation gap” is widely acknowledged, where policy success depends less on stated objectives than on the effectiveness of governance processes37,38,39.

Effective low-carbon city development requires a process-oriented management approach. Shen, et al.40 advocate applying life cycle assessment principles to coordinate activities throughout the development process. The life cycle perspective not only emphasizes quantifiable results but also addresses all stages of construction, thereby supporting the design of carbon reduction strategies41. Urban green space development is similarly an incremental process that requires attention to both outcomes and processes. Yet, few studies have examined how process management can be systematically integrated with outcome indicators to evaluate urban low-carbon green space development.

The second shortcoming concerns sample size and methodology. The Plan–Do–Check–Act (PDCA) cycle from quality management theory42 has been used to assess carbon management processes43,44. Shen, et al.40 expanded the framework by adding “Outcome,” forming the five-process PDCOA model, which outlines how urban low-carbon development can be achieved through continuous management processes. Recent studies have applied this model to evaluate low-carbon development in a limited sample of 36 cities, most of them large and high-level administrative centers40,45,46. However, these studies relied primarily on qualitative indicators, with data collected and scored manually—a process that is time-intensive, error-prone, and susceptible to subjectivity. By contrast, advances in technologies such as web scraping allow for automated, large-scale data collection, while text mining enables systematic scoring, greatly improving both efficiency and accuracy.

To address these gaps, this study makes theoretical, methodological, and empirical contributions. First, it constructs a PDCOA-based, full-process indicator system for evaluating low-carbon urban green space development, integrating life cycle management concepts into the framework. Second, it applies Python-based web scraping and text mining algorithms to automatically extract government bulletins, plans, and news reports from 296 prefecture-level cities, while integrating statistical yearbook data to achieve objective indicator quantification and reduce subjectivity. Finally, by covering the national scale, the study fills gaps in knowledge of process performance in central and western regions and in small- and medium-sized cities, while also identifying common weaknesses and regional differences. The research objectives are to: (1) build a PDCOA-based indicator system and automated evaluation model tailored to China’s context; and (2) quantify performance across the five processes and reveal spatial differentiation patterns. Overall, the study promotes a shift in urban green space development from “meeting standards” toward “closed-loop improvement,” providing policy and planning references for advancing low-carbon urban development.

Materials and methods

Study area

This study aims to comprehensively diagnose the level of low-carbon construction of green spaces in Chinese cities at or above the prefecture level. We selected all cities at or above the prefecture level (297 in total) from China’s seventh population census as sample cities. However, due to substantial missing data from Sansha City, we ultimately chose 296 cities, excluding Sansha City, as the sample cities.

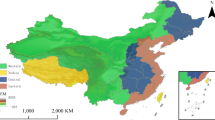

For regional analysis, we adopted the division proposed by Xie, et al.47, which categorizes China into seven regions according to geographic location and economic development: Northeast China, North China, Northwest China, East China, Southwest China, South China, and Central China. Xizang is excluded from this division. The regional distribution of sample cities is shown in Fig. 1.

Regional division of the country. Based on the standard map service website of the Ministry of Natural Resources (http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn) and the boundary of the base map has not been modified.

System of indicators

The PDCOA framework applied in this study extends the classical Plan–Do–Check–Act (PDCA) cycle developed by Deming48. Widely used as a standard for continuous improvement in fields ranging from industrial manufacturing to environmental governance, the framework has been shown to effectively guide systematic management49,50. In this study, we refer to the indicator systems of Shen, et al.40 and Liao, et al.45 to construct an evaluation indicator matrix based on the five-process framework of PDCOA, as shown in Fig. 2. The matrix is structured on three levels and five processes, forming multiple assessment cells. Each assessment cell includes several evaluation indicators, and each evaluation indicator contains several executive indicators, creating a hierarchical structure for the indicator system.

Finally, each executive indicator specifies scoring rules designed to quantify actual performance. The assessment indicators, executive indicators, and scoring rules were determined with reference to a review of previous literature and policy40,46. The assessment indicators and executive indicators are presented in Table 1.

The executive indicators for the five processes were designed according to the formation mechanisms of urban green space carbon sinks: (1) P: In line with China’s 14th Five-Year Plan for urban green space system planning, the carbon sink potential of a city depends on the forward-looking layout of green space area, vegetation quality, and management standards. Therefore, the indicator “planning to enhance green space carbon sequestration capacity” covers three dimensions: protection or expansion of green space area; optimization of vegetation types and community structures; improvement of disaster prevention and maintenance management. Together, these dimensions evaluate the capacity of planning to guide subsequent carbon sequestration outcomes. (2) D: Even a well-designed plan requires effective mechanisms and resources to be translated into actual carbon sinks. The indicator “guarantees for enhancing carbon sequestration capacity” assesses institutional stability and the intensity of financial, technical, and human resource investments, thereby measuring the city’s ability to realize planning objectives. (3) C: The supervision process determines the responsiveness and corrective capacity of closed-loop governance. The indicator “inspection content for monitoring carbon sequestration enhancement” evaluates four areas: regulatory completeness, dedicated funds, professional staffing, and technical conditions, in order to measure the adequacy of monitoring systems for identifying and correcting deviations. (4) O: Carbon sink outcomes are reflected by the indicator “green space carbon sequestration capacity,” which includes three quantitative variables: the built-up area green space ratio, per capita green space area, and per capita park green space area. These variables balance overall scale effects with equity at the individual level. (5) A༚Continuous improvement is crucial to sustaining carbon sink performance. The indicator “measures and plans to improve carbon sequestration capacity” examines three aspects: the development of improvement initiatives, the implementation of incentive mechanisms, and accountability systems. These dimensions measure whether cities can transform monitoring results into drivers of the next planning and implementation cycle.

To ensure applicability, policy documents and relevant datasets from 36 major Chinese cities were reviewed, allowing targeted refinements and adjustments to the indicators. Each executive indicator was scored on a 0–100 scale, including both quantitative and qualitative variables. Scoring rules for qualitative indicators consisted of multiple sub-points with explicit criteria. For example, the executive indicator “Planning for the protection and enhancement of green areas” included detailed scoring points, bases, and rules (Table 2).

A multi-stage approach was employed to ensure the validity of the indicator system. First, the initial framework was constructed strictly in accordance with the PDCOA model from existing studies40,45,46 and relevant national and local policy documents, such as the National Land Greening Planning Outline (2022–2030) and the Urban Greening Management Measures. Second, the draft indicator system was reviewed by five PhDs specializing in urban planning and environmental management. Based on their feedback, two rounds of revisions improved comprehensiveness, relevance, and operability by removing redundant items and refining wording. Finally, through a preliminary analysis of policy texts from 36 cities, the applicability and data availability of all indicators were verified. Through these steps, we ensured that the indicator system accurately and comprehensively reflects the level of low-carbon green space development in Chinese cities.

Data collection

The executive indicators for processes P, D, C, and A are all qualitative variables. Their data sources are mainly documents from the official websites of the sample city governments, including regulations, administrative documents, planning documents, summary reports, and news reports.

For the Planning (P) process, data came from 14th Five-Year Plan documents related to urban green space, such as the Hangzhou Municipal Ecological Environment Protection “14th Five-Year Plan” (2021–2025). These documents were retrieved manually.

For the D, C, and A processes, data were collected using Python-based web scraping (Fig. 3). We developed a framework in Python 3.11, combining Selenium 4.18 and BeautifulSoup 4.12, and deployed it in an Ubuntu 22.04 environment. The crawler simulated manual browsing of the first 20 pages of search results on the official websites of 296 municipal governments (.gov.cn, .gov, and official WeChat accounts). Data collection was completed in August 2023. The crawler searched for keywords related to green space and carbon sinks (e.g., “green space,” “green space system,” “park green space,” “landscape greening,” “green space carbon sink,” “green space maintenance,” “green space management”). The initial keyword set (K₀), combined with the initial scoring system (S₀), generated the first text set (T₀). The process then iterated in a human–machine collaborative mode (“crawler–expert–crawler”), where experts refined the keyword set (Ki₊₁) and scoring system (Si) based on the matching degree (R) between Ti and Si. Iterations stopped when R reached a stable threshold. After 25 iterations, more than 102,000 valid files (11 GB) were collected from approximately 1.54 million webpages. Data cleaning excluded duplicates (similarity ≥ 0.95), irrelevant content, and pages with fewer than 100 characters of main text. A total of 102,115 documents were retained. To verify reliability, 10% of the sample was randomly selected for cross-checking by two researchers. Additionally, the consistency coefficient was κ = 0.87, significantly higher than the benchmark of 0.75, confirming the clarity, objectivity, and reproducibility of the scoring criteria. All qualitative variables were then automatically scored and validated using Python according to the established rules.

For the O process, all executive indicators were quantitative. Data were drawn from the China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook 2021 and the China City Statistical Yearbook 2021.

Calculation model

The low-carbon construction level of urban green spaces is determined by the performance values of the five processes. The formula for calculating the low-carbon construction level is based on the methods of Shen, et al.40 and Liao, et al.45.

At the process level, the value of the low-carbon construction level of urban green space(\(\:{\text{V}}_{{\text{s}}_{\text{i}}}\))is calculated using Eq. (1):

Where \(\:{\text{V}}_{{\text{s}}_{\text{i}}}\) is the score value of indicator i in process s, and n is the number of indicators in process s, which varies across different processes.

At the indicator level, the low-carbon construction level(\(\:{\text{V}}_{{\text{s}}_{\text{i}}}\))is calculated using Eq. (2):

Where \(\:{\text{V}}_{{\text{s}}_{\text{i}-\text{j}}}\)is the value of the score variable\(\:\:\text{j}\) within indicator \(\:\text{i}\) in process \(\:\text{s}\), and \(\:\text{m}\) is the number of score variables\(\:\:\text{j}\). The number of score variables \(\:\text{m}\) may vary between indicators.

At the executive indicator level, which includes both quantitative and qualitative attributes, we use a percentage system for the score variables of quantitative attributes, standardizing them from 0 to 100 points. Since all executive indicators are positive variables, all score variables are standardized as follows (3):

Where \(\:{\text{x}}_{\text{j}}\) is the value of score variable \(\:\text{j}\);\(\:{\text{x}}_{\text{h}}\) is the maximum value of score variable \(\:\text{j}\) (the optimal value); and \(\:{\text{x}}_{\text{l}}\) is the minimum value of score variable \(\:\text{j}\) (the worst value).

Additionally, since processes P and O are influenced by the characteristics of urban endowment, cities with rich vegetation resources and favorable natural conditions have a natural advantage in green space construction. To avoid a one-size-fits-all approach in city evaluation, we use a correction coefficient (α) to mitigate the impact of these characteristic conditions on the calculated values of processes P and O45. We adopt “annual precipitation” as the objective characteristic indicator (k) to represent the difficulty of building green space under these conditions. Research indicates that precipitation generally promotes vegetation growth51,52 and enhances carbon sink levels53. This indicator is negative; the higher the value, the less challenging it is to build green space and implement low-carbon construction. Thus, it should have a correction coefficient less than 1. The correction coefficient is calculated using Eq. (4):

Where \(\:{{\upalpha\:}}_{\:}\)is the correction coefficient for city \(\:\text{j}\), \(\:{\text{k}}_{\text{j}}\)is the value of the objective characteristic index for city \(\:\text{j}\). \(\:\text{M}\text{e}\text{d}\text{i}\text{a}\text{n}\left(\text{L}\text{n}{\text{k}}_{\text{j}}\right)\) denotes the median of the logarithmic values of the characteristic indicators for city\(\:\:\text{j}\).

Furthermore, the performance of low-carbon construction of urban green spaces in China is divided into four tiers using the Quartile method, which is an effective classification method54,55. This method divides the data into four tiers using five quartiles, providing a clear classification of the results.

Results

Performance of cities

The average level of low-carbon construction in urban green spaces across China was 44.10 (SD = 13.11). As shown in Supplementary Material–Table S1, the cities with the highest overall scores were Beijing (92.81), Jiayuguan (82.50), Nanjing (78.58), Hangzhou (76.06), and Hohhot (74.12).

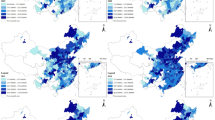

Spatial analysis revealed significant regional disparities (Fig. 4). Overall, eastern cities scored higher, while western cities scored lower. In the eastern regions (e.g., Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta, and Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei), scores were generally high with strong spatial clustering, forming distinct “high-value zones.” The central region (e.g., Hubei, Hunan, Anhui) ranked at an intermediate level. Although some provincial capitals and core cities formed localized high-value clusters, their performance was slightly below that of the eastern region. By contrast, the western and northeastern regions exhibited generally lower scores. Northwestern and southwestern areas were dominated by “low-value clusters,” indicating persistent regional imbalances.

Spatial distribution pattern of low-carbon construction level of urban green spaces in China. Based on the standard map service website of the Ministry of Natural Resources (http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn) and the boundary of the base map has not been modified.

Performance also varied across the five processes. The top-scoring cities were as follows: (1) P: Rizhao, Tianjin, Zhoukou, Huanggang, Chengdu. (2) D: Beijing, Jinhua, Hangzhou, Suqian, Ningbo. (3) C: Beijing, Fuxin, Jinhua, Nanjing, Linyi. (4) O: Beijing, Jiayuguan, Wuhai, Karamay, Shizuishan. (5) A: Beijing, Jingmen, Wuhan, Weihai, Maanshan.

As shown in Table 3, scores ranged from 92.81 to 10.42, highlighting substantial disparities among cities. Most cities fell into the second and third tiers. Spatial visualization (Fig. 5) further illustrates these patterns. First-tier cities were geographically scattered. Second-tier cities were mainly located in eastern China and along the Yangtze River Basin. Third-tier cities were concentrated in northeastern and central China, while fourth-tier cities were primarily located in border areas in the north, west, and south.

Spatial distribution of the level of low-carbon construction in urban green spaces. Based on the standard map service website of the Ministry of Natural Resources (http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn) and the boundary of the base map has not been modified.

Performance of regions

Regional analysis (Fig. 6) indicated significant score differences (F = 5.22, p < 0.001). East China achieved the highest mean score (50.08), followed by North China (45.58) and Northwest China (45.38). In contrast, Southern China (38.25) and Northeast China (40.30) had the lowest mean scores.

Across the five processes: (1) P: Regional differences were not significant (F = 0.52, p = 0.791). Southwest (62.69) and Central (62.35) China had relatively high means, while Northeast (58.01) had the lowest. Overall variation was limited. (2) D: Regional differences were significant (F = 7.23, p < 0.001). East China (66.95) outperformed all other regions, while Southern (44.61) and Northeast China (46.62) scored lower. (3) C: Significant regional variation was observed (F = 6.64, p < 0.001). East China (49.92) achieved the highest mean, while Southern (25.69) and Northeast China (30.26) scored considerably lower. (4) O: Regional differences were now found to be significant (F = 4.27, p < 0.001). East China (34.92) scored highest, while Central (22.19) and Southwest China (24.19) scored lowest. (5) A: Regional differences were significant (F = 6.26, p < 0.001). East China (46.69) ranked highest, whereas Southern (22.89) and Northeast China (30.83) were notably lower.

In summary, significant regional disparities existed in the overall scores and in the D, C, O, and A processes, while only the P process showed no significant differences. East China consistently achieved higher performance, whereas Southern and Northeast China scored lowest across multiple processes.

Table 4 further illustrates the tier distribution across regions. First-tier cities were concentrated in North (2), Northwest (1), and East (2) China, with no presence in other regions, indicating that high-performing cities are concentrated in economically developed areas. Second-tier cities were more widespread, with the largest share in East China (35), followed by Northwest (12), North (8), and Southwest (8). Southern (4), Central (6), and Northeast (7) had fewer. Third-tier cities were distributed across all regions, with East (35) and Central (32) having the largest shares, followed by Southern (23) and Northeast (20). Fourth-tier cities were concentrated in Southern China (11), with fewer than 7 in any other region.

Performance of processes

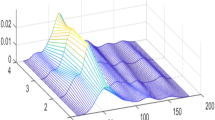

In this study, the scores for the five processes in each sample city were calculated, as detailed in the Supplementary Material-Table S2. According to the table, the sample cities perform best in the P process with a mean value of 59.81, followed by the D (57.60), C (38.94), A (36.10), and O (31.21) processes. The C process has the highest standard deviation (22.74), indicating wide variation in scores among different cities. Conversely, the P process has the lowest standard deviation (16.41), showing that the sample cities’ scores in the P process are more concentrated. The distribution of scores for each process is shown in Fig. 7. This figure reveals that the scores of the sample cities in the P and D processes are mostly distributed in the middle to high ranges. In contrast, the scores in the C, O, and A processes are more concentrated in the middle to low ranges.

Discussion

Spatial differentiation in the level of low-carbon construction of urban green spaces

This study found significant spatial heterogeneity in the low-carbon construction of urban green spaces. Unlike previous research that primarily emphasized outcome-oriented indicators such as the quantity and quality of green spaces21,56,57, this study employed a PDCOA-based comprehensive evaluation framework. The results revealed that the level of low-carbon construction is shaped not only by outcomes but also by governance processes, including Plan, Do, Check, Outcome and Act. This provides a new mechanistic perspective for understanding spatial differentiation.

First, cities with higher administrative levels and stronger governance capacity showed clear advantages. For example, Beijing, as the capital of China, ranked first nationwide. Its performance reflected not only superior resource allocation but also a mature governance system. In recent years, Beijing has issued a series of policy documents addressing green space planning, investment, and management, such as the Beijing High-Quality Development Action Plan for Landscape and Greening (2021–2025) and the Opinions on Investment Standards for Urban Green Space Maintenance and Management in Beijing. More importantly, the Guiding Opinions on Implementing the ‘Dual Carbon’ Goals in the Landscape and Greening Industry of Beijing during the 14th Five-Year Plan Period explicitly targeted carbon sinks. Regular administrative meetings organized by the Beijing Municipal Bureau of Landscape and Forestry ensured effective supervision, inspection, and feedback. Through high standards at the P and D stages, strict supervision (C process), and systematic feedback (A process), Beijing successfully translated planning intentions into practice. This comprehensive governance capacity explains why Beijing excelled in both outcomes (O) and processes. According to center–periphery theory58, cities with higher administrative status assume greater urban functions and leverage their institutional advantages to formulate detailed policies, thereby increasing efficiency. Greening policies in turn facilitated the expansion of urban parks and green spaces59.

Second, the overall “east high–west low” pattern identified in this study partially corresponded to the coastal and riverine “T-shaped” distribution proposed by Xu, et al.21. However, our findings diverged from Yang, et al.56 who reported higher green space quality in western and northeastern regions. Their results reflected an evaluation framework that incorporated building density, which favors cities with lower population densities. In contrast, the PDCOA framework emphasizes that sustainable green space carbon sink development is achieved through systematic governance measures. As a result, eastern cities—despite high population density and limited land resources, which reduced their per capita outcome scores—still ranked highest overall. Their strength lay in robust policy enforcement (D process), stronger supervision and inspection (C process), and more active feedback mechanisms (A process). This highlighted the compensatory role of proactive governance in overcoming natural or demographic constraints.

Previous studies often emphasized economic development as the primary driver of urban green space construction60. A key finding of this study, however, is that economic resources and natural endowments are not decisive. Instead, comprehensive and high-quality process governance is the foundation of superior performance. The results revealed two distinct development models: Endowment-dependent and governance-driven.

Endowment-dependent cities achieved high outcome scores but lacked systematic process management. Karamay in Northwest China exemplifies this pattern. Its low population density resulted in high per capita green space area, yielding an outcome score of 86.09, ranked fourth nationally. However, its process scores—P (43.44), D (40), C (11), and A (16.67)—were all below the national average, leading to a total score of 46.52, only in the third tier. Similarly, Dongguan in South China, despite ranking 24th in national GDP in 2022 and achieving an outcome score of 76.26 (11th nationally), scored below 30 in the D, C, and A processes. Weak process management dragged its total score down to 42.69, also in the third tier. These two cases serve as a cautionary tale: reliance on natural or economic advantages alone is insufficient. Without rigorous planning, strong implementation, and effective supervision and feedback, cities risk poor overall performance despite resource advantages.

By contrast, Hangzhou represents a governance-driven city. Although its outcome score (O process = 59.63) was not particularly high—likely due to land scarcity in densely populated areas—its total score reached 76.06, ranking fourth nationally. The city’s success stemmed from systematic top-level planning and refined management. Hangzhou has issued multiple policy documents, including the Green Space Management Regulations, the Carbon Peaking Three-Year Action Plan (2023–2025), the Urban Green Space Comprehensive Evaluation Measures, and the Urban Public Green Space Maintenance Fund Management Measures. These policies established a long-term green space maintenance system. This case illustrates that cities can achieve high overall performance even when result-based indicators are constrained, provided they sustain strong process governance. This finding aligns with international cases such as Singapore, which overcame environmental and spatial limitations through long-term political commitment and robust governance processes, transforming itself into a “city in nature”61,62.

The comparison between governance-driven and endowment-dependent cities demonstrates that the “human factor” of governance processes outweighs innate resource endowments. Urban success in green and low-carbon development ultimately depends less on what a city possesses than on what it does and how it governs. This provides an important insight for cities with weaker economic or environmental foundations: by establishing a complete PDCOA governance cycle, they can also achieve transformative progress in low-carbon urban green space development.

Process differences in the level of low-carbon construction of urban green spaces

As shown in "Performance of processes", the performance of urban green space low-carbon construction across the five PDCOA processes was highly uneven. The P and D processes achieved relatively high average scores, while the C, O, and A processes scored much lower. This “front-loaded, back-light” pattern highlights systemic governance shortcomings in China’s urban green space management. Such front-loaded governance—prioritizing planning and construction while neglecting monitoring and feedback—is a common challenge in global public policy. Research in Australia and the UK, for instance, has identified a persistent “evaluation gap,” where post-project monitoring and adaptive management are under-resourced and deprioritized once construction is complete63,64.

The relatively strong performance in the P and D processes largely reflected top-down policy drivers. Under the national strategies of the “dual carbon” goals and “ecological civilization construction,” many cities issued planning documents (e.g., Urban Greening Regulations) and allocated resources accordingly46. This reflects a “task-oriented” or “project-driven” governance tendency, in which the emphasis lies in producing plans and implementing projects.

In contrast, the consistently low scores in the C, O, and A processes revealed the absence of closed-loop governance. Several institutional, technical, and resource-related barriers contributed to these weaknesses: (1) C process: This process recorded both low scores and high variability, suggesting widespread inadequacy and inconsistency. Three factors stand out. First, institutional deficiencies: the absence of standardized, quantifiable monitoring criteria for carbon sink performance and the lack of cross-departmental supervision mechanisms often reduced inspections to formalities. Second, technical challenges: dynamic monitoring of vegetation and soil carbon requires specialized expertise and equipment, which many small- and medium-sized cities lack. Third, resource constraints: fiscal and human resources for long-term monitoring and maintenance were insufficient compared with the heavy investment in initial construction. For example, in the lowest-scoring cities, government websites contained almost no reports on green space inspections or evaluations, directly reflecting managerial neglect. (2) O process: The relatively low scores indicated that substantial inputs did not translate into expected results. Weaknesses in the C and A processes contributed to problems not being corrected in time. Moreover, outcomes were constrained by structural factors, including natural endowments, stage of urban development, and land availability. Densely built metropolises, despite large investments, struggled to match indicators such as per capita green space with less dense cities endowed with greater ecological resources. This finding is consistent with studies showing that the stages of urbanization influence green space quality56. (3) A process: This process consistently received the lowest scores, underscoring the lack of motivation for performance improvement. The causes include weak accountability mechanisms—since green space outcomes are rarely linked to official performance evaluations—limited incentive systems for innovation, and entrenched path dependence. Many local governments preferred launching new rounds of P and D rather than refining strategies based on prior C or O. This led to a cycle where “plans accumulate, but results stagnate.”

In sum, the governance imbalance reflects an overemphasis on tasks and projects rather than outcomes and learning. Addressing these deficiencies requires a transition from a task-driven to a performance-driven model, supported by standardized monitoring, strong accountability, and effective incentives.

Policy implications

Based on the findings above—particularly the persistent weaknesses in the C, O, and A processes and the variation across city types—this study proposes several targeted policy recommendations.

(1) Establish standardized closed-loop governance mechanisms. At the national level, technical guidelines for monitoring and evaluating urban green space carbon sinks should be issued. These should define core indicators (e.g., vegetation carbon density, soil organic carbon content, and site accessibility), specify recommended monitoring technologies (e.g., combining remote sensing with ground surveys), and set minimum monitoring frequencies (e.g., annual assessments). Cities should be encouraged to form interdepartmental inspection task forces (involving landscape, environment, planning, and finance departments) and allocate dedicated budgets for long-term monitoring. This would ensure professional independence and continuity. (2) Strengthen incentives and accountability in the A process. PDCOA-based performance evaluations of green space construction should be integrated into local government performance appraisal systems. Linking the C and A process scores to the evaluation of senior officials would create binding accountability. In addition, establishing an innovation incentive fund for urban greening could reward cities that adopt advanced technologies or management practices to improve efficiency and outcomes. (3) Implement differentiated spatial development and resource allocation strategies. For cities with low O process scores: Cities with poor natural endowments but relatively strong P and D performance (e.g., arid western cities) should focus on enhancing the quality of existing green spaces rather than expanding their quantity. Measures could include promoting drought-resistant vegetation and optimizing plant community structures to maximize carbon sequestration efficiency per unit area. Old industrial cities in transition should be supported through “brownfield greening” subsidies, encouraging the conversion of abandoned industrial land into ecological parks. Cities with weak C and A processes (mainly in central-western and northeastern regions) should receive targeted assistance. High-performing eastern cities such as Beijing and Hangzhou could transfer expertise, standards, and talent, while regional financial and technical support would help build effective monitoring and feedback systems. (4) Revitalize underutilized urban spaces and enhance multifunctionality. Cities should systematically identify “residual urban spaces”—such as underpasses, abandoned railway lines, rooftops, and idle plots in older neighborhoods—and incorporate them into “micro-green space” development plans. Governments can encourage community groups, enterprises, and residents to participate by providing design guidance, simplifying approval processes, and offering small subsidies. Accumulated small-scale greening efforts can enhance ecological connectivity and overall green coverage.

In conclusion, advancing low-carbon urban green space development requires a governance transformation. Building a complete PDCOA-based closed-loop system, improving accountability, and tailoring strategies to local conditions will allow cities to shift from “results on paper” to sustainable performance improvements in practice.

Limitations of the study

There are several limitations to this study. First, the data for the O-process in this study only considered the size of urban green space and ignored the quality of green space construction, such as tree cover, vegetation species, canopy cover, accessibility, and trail density. Second, while many studies have analyzed urban green spaces from the perspective of carbon sinks1,65,66, it is important to acknowledge that urban green spaces can also be carbon sources14. Third, the data used to evaluate the qualitative indicators are mainly based on governmental official documents and statistical survey data. These sources are not always highly transparent in terms of data disclosure and accessibility, which may result in diagnostic errors compared to the real situation.

Conclusion

This study is the first to integrate the PDCOA five-process management framework with automated text mining to systematically evaluate the low-carbon construction of urban green spaces in 296 prefecture-level cities in China. By combining both process and outcome dimensions, the analysis provides a comprehensive diagnosis of the current status, shortcomings, and future directions of green space development.

The findings show that the average national score is only 44.10, revealing substantial room for improvement and significant disparities across cities. A small number of leaders, including Beijing (92.81) and Hangzhou (76.06), performed exceptionally well, while most cities lagged behind. Regionally, an “east-high, west-low” pattern emerged, with eastern coastal areas and the Yangtze River Delta forming high-value clusters. Across the PDCOA stages, a clear imbalance was observed: P (59.81) and D (57.60) scored relatively high, while C (38.94), A (36.10), and O (31.21) scored considerably lower, with outcomes ranking the weakest.

The core conclusion is that superior performance in green space low-carbon development depends less on economic capacity or natural endowments than on effective process governance. Cities with resource advantages but weak governance (e.g., Dongguan, Karamay) performed poorly, while others (e.g., Hangzhou) compensated for inherent limitations through robust process management. This demonstrates the critical need to move beyond a “results-oriented” model toward one centered on “process management.” Establishing a closed governance loop—incorporating standardized monitoring, strict accountability, and effective incentives—is essential for improving performance and ensuring sustainable outcomes.

The primary contribution of this study lies in validating a process-oriented diagnostic framework that shifts the evaluation of urban green spaces from static results to dynamic governance processes. Only by strengthening all stages of the PDCOA cycle can cities improve efficiency, maximize carbon sink potential, and advance sustainable, low-carbon urban development.

Looking forward, several directions warrant further exploration. First, the evaluation system can be refined to better capture quality dimensions of green space, such as tree canopy cover and biodiversity, particularly in the O stage. Second, future studies could adopt a life cycle assessment (LCA) perspective to consider carbon sink and carbon source effects across construction, maintenance, and disposal phases. Third, as more diverse data sources become available, integrating remote sensing imagery, crowdsourced data, and social media information could supplement official records and enhance both the accuracy and timeliness of assessments.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Zhao, D., Cai, J., Xu, Y., Liu, Y. & Yao, M. Carbon sinks in urban public green spaces under carbon neutrality: A bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 86, 128037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2023.128037 (2023).

Liu, Z., Deng, Z., Davis, S. J. & Ciais, P. Global carbon emissions in 2023. Nat. Reviews Earth Environ. 5, 253–254. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-024-00532-2 (2024).

Seto, K. C. et al. Human settlements, infrastructure, and spatial planning. (2014).

Cohen, B. & Urbanization City growth, and the new united nations development agenda. Cornerstone 3, 4–7 (2015).

Liu, C. et al. Decoupling the effect of climate and land-use changes on carbon sequestration of vegetation in mideast Hunan Province, China. Forests 12, 1573. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12111573 (2021).

Yang, L. & Li, Y. Low-carbon City in China. Sustainable Cities Soc. 9, 62–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2013.03.001 (2013).

Huang, Z., Fan, H. & Shen, L. Case-based reasoning for selection of the best practices in low-carbon City development. Front. Eng. Manage. 6, 416–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42524-019-0036-1 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Quantitative structure and Spatial pattern optimization of urban green space from the perspective of carbon balance: A case study in Beijing, China. Ecol. Indic. 148, 110034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110034 (2023).

Singkran, N. Carbon sink capacity of public parks and carbon sequestration efficiency improvements in a dense urban landscape. Environ. Monit. Assess. 194 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-022-10432-x (2022).

Dong, X. & He, B. J. A standardized assessment framework for green roof decarbonization: A review of embodied carbon, carbon sequestration, bioenergy supply, and operational carbon scenarios. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 182 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.113376 (2023).

Zhang, M., Chen, K., Liu, H. & Yi, Y. Analysing carbon density in urban parks by considering the management of different functional parks: A case study in Beijing. Ecol. Indic. 166, 112411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112411 (2024).

Velasco, E., Roth, M., Norford, L. & Molina, L. T. Does urban vegetation enhance carbon sequestration? Landsc. Urban Plann. 148, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.12.003 (2016).

Liu, H. et al. Sensing-based park cooling performance observation and assessment: A review. Build. Environ. 245 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110915 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Is urban green space a carbon sink or source? - A case study of China based on LCA method. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 94 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2022.106766 (2022).

Fan, W., Huang, S., Yu, Y., Xu, Y. & Cheng, S. Decomposition and decoupling analysis of carbon footprint pressure in China’s cities. J. Clean. Prod. 372 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133792 (2022).

Nowak, D. J., Greenfield, E. J., Hoehn, R. E. & Lapoint, E. Carbon storage and sequestration by trees in urban and community areas of the united States. Environ. Pollut.. 178, 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2013.03.019 (2013).

Rodriguez Mendez, Q., Fuss, S., Lück, S. & Creutzig, F. Assessing global urban CO2 removal. Nat. Cities. 1, 413–423. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-024-00069-x (2024).

Nero, B. F. Urban green spaces enhance carbon sequestration and conserve biodiversity in cities of the Global South. (2017).

Wang, H., Feng, Y. & Ai, L. Progress of carbon sequestration in urban green space based on bibliometric analysis. Front. Environ. Sci. 11 https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1196803 (2023).

Li, Y. The development path options and policy proposals of Low-carbon economic in China. Urban Stud. 2, 1–16 (2010).

Xu, Z., Zhang, Z. & Li, C. Exploring urban green spaces in china: Spatial patterns, driving factors and policy implications. Land. Use Policy. 89 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104249 (2019).

Kuang, W. & Dou, Y. Investigating the patterns and dynamics of urban green space in china’s 70 major cities using satellite remote sensing. Remote Sens. 12 (2020).

Zhou, Q. et al. China’s green space system planning: Development, experiences, and characteristics. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 60 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127017 (2021).

Wu, J., Wang, M., Li, W., Peng, J. & Huang, L. Impact of urban green space on residential housing prices: case study in Shenzhen. J. Urban. Plan. Dev. 141 https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000241 (2015).

Zhao, S. et al. Ecological consequences of rapid urban expansion: Shanghai, China. Front. Ecol. Environ. 4, 341–346 (2006). 10.1890/1540-9295(2006)004[0341:ECORUE]2.0.CO;2.

Hu, A. et al. Harnessing multiple data sources and emerging technologies for comprehensive urban green space evaluation. Cities 143, 104562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104562 (2023).

Lu, Y., Chen, R., Chen, B. & Wu, J. Inclusive green environment for all? An investigation of Spatial access equity of urban green space and associated socioeconomic drivers in China. Landsc. Urban Plann. 241 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104926 (2024).

Song, H. & Wang, M. Integrating ecosystem services: a new indicator for evaluating net carbon sink efficiency of urban green spaces and its influencing factors. Ecol. Indic. 178, 113901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2025.113901 (2025).

Khan, M. W., Hossain, M. S. & Alam, M. GIS-based analysis to identify the distribution and accessibility of urban green space in Dhaka metropolitan City, Bangladesh. J. Geographic Inform. Syst. 15, 35–52 (2023).

Martin, G. K. et al. Tracking progress toward urban nature targets using landcover and vegetation indices: A global study for the 96 C40 cities. GeoHealth 8 (e2023GH000996). https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GH000996 (2024).

Schumacher, U. Analysis options for urban green spaces based on unified urban masks: selected results for European cities. Land 13 (2024).

Li, X., Ma, X., Hu, Z. & Li, S. Investigation of urban green space equity at the City level and relevant strategies for improving the provisioning in China. Land. Use Policy. 101 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105144 (2021).

Zhang, J. Inequalities in the quality and proximity of green space exposure are more pronounced than in quantity aspect: evidence from a rapidly urbanizing Chinese City. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 79 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127811 (2023).

Liu, W., Li, H., Xu, H., Zhang, X. & Xie, Y. Spatiotemporal distribution and driving factors of regional green spaces during rapid urbanization in Nanjing metropolitan area, China. Ecol. Indic. 148 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110058 (2023).

Yu, Y. & Zhang, N. Low-carbon City pilot and carbon emission efficiency: Quasi-experimental evidence from China. Energy Econ. 96, 105125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105125 (2021).

Khanna, N., Fridley, D. & Hong, L. China’s pilot low-carbon City initiative: A comparative assessment of National goals and local plans. Sustainable Cities Soc. 12, 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2014.03.005 (2014).

Fransen, T. et al. Taking stock of the implementation gap in climate policy. Nat. Clim. Change. 13, 752–755. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01755-9 (2023).

Odenweller, A. & Ueckerdt, F. The green hydrogen ambition and implementation gap. Nat. Energy. 10, 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-024-01684-7 (2025).

Hogwood, B. & Gunn, L. In Policy Process 217–225 (Routledge, 2014).

Shen, L. et al. Dual perspective diagnosis on low carbon city performance. J. Green. Building. 18, 167–184. https://doi.org/10.3992/jgb.18.3.167 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Combining life cycle assessment and Building information modelling to account for carbon emission of Building demolition waste: A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 172, 3154–3166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.087 (2018).

Deming, W. E. & Cambridge, T. J. M. I. o. MA. Out of crisis, centre for advanced engineering study. 367–388 (1986).

Bekaroo, G., Bokhoree, C., Ramsamy, P. & Moedeen, W. Investigating personal carbon emissions of employees of higher education institutions: insights from Mauritius. J. Clean. Prod. 209, 581–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.10.238 (2019).

Nsafon, B. E. K. et al. Integrating multi-criteria analysis with PDCA cycle for sustainable energy planning in africa: application to hybrid mini-grid system in Cameroon. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 37 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2020.100628 (2020).

Liao, S. et al. Correction factor for mitigating the ‘One-Size-Fits-All’ phenomenon in assessing Low-Carbon City performance. Land 13 (2024).

Shen, L. B. H. Low Carbon City Performance in China (2022) (Science, 2023).

Xie, P. et al. Study on the measurement of interprovincial carbon emission performance, regional gaps, and Spatial convergence in China. Energy 317, 134597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2025.134597 (2025).

Moen, R. & Norman, C. (Citeseer, (2006).

Isniah, S., Purba, H. H. & Debora, F. Plan do check action (PDCA) method: literature review and research issues. Jurnal Sistem dan. Manajemen Industri. 4, 72–81 (2020).

Trippner-Hrabi, J., Chądzyński, J. & Kam, A. Unveiling the significance of the PDCA Deming cycle. Ethics Innov. Public. Administration 299 (2024).

Jiang, Y. & Yuan, T. The effects of precipitation change on urban meadows in different design models and substrates. Sci. Rep. 13 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44974-y (2023).

Holdrege, M. C., Beard, K. H. & Kulmatiski, A. Woody plant growth increases with precipitation intensity in a cold semiarid system. Ecology 102, e03212. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3212 (2021).

Sun, Y. et al. Precipitation controls on carbon sinks in an artificial green space in the Taklimakan desert. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 41, 2300–2312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-024-3367-8 (2024).

He, H., Shen, L., Du, X. & Liu, Y. Analysis of Temporal and Spatial evolution of tourism resource carrying capacity performance in China. Ecol. Indic. 147, 109951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.109951 (2023).

Shen, L., Du, X., Cheng, G., Shi, F. & Wang, Y. Temporal-spatial evolution analysis on low carbon City performance in the context of China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 90 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106626 (2021).

Yang, Z., Fang, C., Mu, X., Li, G. & Xu, G. Urban green space quality in china: quality measurement, Spatial heterogeneity pattern and influencing factor. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 66 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127381 (2021).

Huang, Y. et al. Spatial patterns of urban green space and its actual utilization status in China based on big data analysis. Big Earth Data. 5, 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/20964471.2021.1939990 (2021).

Gopinathan, S. & Altbach, P. G. (Taylor & Francis, 2005).

Zhou, X. & Wang, Y. C. Spatial–temporal dynamics of urban green space in response to rapid urbanization and greening policies. Landsc. Urban Plann. 100, 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.12.013 (2011).

Huang, Y. et al. Spatial patterns and inequity of urban green space supply in China. Ecol. Indic. 132 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.108275 (2021).

Zingoni de Baro, M. E. In Regenerating Cities: Reviving Places and Planet (ed Maria Elena Zingoni de Baro) 163–206Springer International Publishing, (2022).

Tan, P. Y., Wang, J. & Sia, A. Perspectives on five decades of the urban greening of Singapore. Cities 32, 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.02.001 (2013).

Jacobson, C., Carter, R. W., Thomsen, D. C. & Smith, T. F. Monitoring and evaluation for adaptive coastal management. Ocean. Coast Manage. 89, 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.12.008 (2014).

Alexander, M. in Management Planning for Nature Conservation: A Theoretical Basis & Practical Guide (ed Mike Alexander) 69–92Springer Netherlands, (2013).

Wang, H., Feng, Y. & Ai, L. Progress of carbon sequestration in urban green space based on bibliometric analysis. Front. Environ. Sci. 11 https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1196803 (2023).

Chen, L., Wang, Y., Zhu, E., Wu, H. & Feng, D. Carbon storage Estimation and strategy optimization under low carbon objectives for urban attached green spaces. Sci. Total Environ. 923 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171507 (2024).

Funding

This work was financially supported by Natural Science Foundation of China under a grant no. 42307594 and no.42407638.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yang Guo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review and Editing, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. Yuanjing Zhang: Writing—Review and Editing.Xiangrui Xu: Resources, Methodology, Writing—Review and Editing. Peng Zhan: Writing—Original Draft Preparation. Zeyu Cao: Visualization. Yu Bai: Writing—Review and Editing. Linshen Jiao: Writing—Review and Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Y., Zhang, Y., Xu, X. et al. Evaluating low-carbon construction of urban green spaces in China through a process management perspective. Sci Rep 16, 3552 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33575-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33575-6