Abstract

Microplastics (MPs), increasingly common in freshwater ecosystems, pose serious ecological threats to the Formosan landlocked salmon (Oncorhynchus masou formosanus), an endangered salmonid endemic to Taiwan. This study presents the first comprehensive investigation into how seasonal variation and land-use patterns influence MP abundance, composition, and distribution in the salmon’s exclusive habitats within Shei-Pa National Park, Taiwan. Using µ‑FTIR spectroscopy and fluorescence microscopy, we quantified microplastic concentrations and observed higher levels in the dry season (48–93 items/L) than in the wet season (45–72 items/L). Principal component analysis (PCA) further indicated spatial gradients aligned with land‑use contrasts, with higher concentrations associated with intensive agriculture and recreational tourism relative to pristine forest areas. Seasonal variation profoundly influenced MPs’ composition, with synthetic fibers (Rayon and Polyester) predominating in the wet season and common plastic polymers (PET, PE, PP) increasing in the dry season. Smaller-sized MPs (< 25 µm), potentially more hazardous due to their capacity for trophic transfer, were predominant in upstream reaches during critical salmon breeding periods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to their affordability and advances in processing technologies, plastics are extensively utilized in daily human activities and various products such as clothing, food packaging, agricultural nets, fertilizer bags, and fishing nets1,2. However, only approximately 7% of plastic products are recycled3. It is projected that by 2050, global plastic waste generation will reach 12 billion tons, accumulating significantly in landfills and natural environments4. Larger plastic waste typically degrades into microplastics (MPs), broadly defined as plastic fragments smaller than 5 mm, through environmental processes such as biological activity, UV irradiation, mechanical abrasion and temperature fluctuations5. MPs pose substantial risks to aquatic life due to their surface adsorption of toxic hydrophobic organic pollutants, exposing aquatic organisms to chemical contaminants6. Previous research has indicated that MPs accumulate in animal tissues, are difficult to remove, and biomagnify through food chains, thereby becoming a significant environmental concern7,8. Although extensive studies have quantified and described the spatial, depth, and temporal distribution of MPs, the effects of seasonal variations and surrounding land use on MPs remain insufficiently explored9.

MP pollution sources include various anthropogenic activities such as agriculture, residential areas, and industrial processes2,6,10, releasing both macroplastic debris and primary MPs into the environment11. Surface runoff, upstream inflow, sewage discharge, and atmospheric deposition are potential pathways of MPs into freshwater systems from their sources1,12,13. Areas proximal to pollution sources generally exhibit higher plastic concentrations14, suggesting significant associations between land use types adjacent to waterways and MP characteristics in aquatic environments. Additionally, the transport of plastic materials depends on surface water flow dynamics influenced by seasonal changes. Some studies suggest that during the wet season, continuous rainfall accelerates MPs entry into rivers and reservoirs via runoff and atmospheric deposition, whereas reduced precipitation during dry seasons limits this input9. Conversely, other studies have found increased rainfall during wet seasons enhances river flow, rapidly transporting plastics downstream and resulting in lower MP concentrations in freshwater bodies15. Reduced water flow during dry seasons facilitates sedimentation of plastics in rivers and tributaries. These differing findings indicate an incomplete understanding of seasonal variations, essential for effective MP pollution prevention strategies.

Plastic debris undergoes various environmental degradation processes, forming secondary MPs, which, together with primary MPs, pollute ecosystems16,17. Smaller MPs become increasingly prevalent with ongoing degradation and are more easily transported downstream, potentially resulting in size-dependent MP distributions in river systems11. The combined effects of differential transport, continuous degradation, and hydrodynamics during wet and dry seasons drive dynamic variations in MP characteristics along river systems.

Due to its moderate flow velocity and diverse topography18, Creek Qijiawan and its tributaries in Wuling area of Shei-Pa National Park, Taiwan, represent the sole natural habitat of the Formosan landlocked salmon (Oncorhynchus masou formosanus). Although its parent species, Oncorhynchus masou, is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List, the Formosa landlocked salmon is classified as Nationally Endangered in Taiwan’s 2017 Red List19 and Critically Endangered under the 1996 IUCN assessment20. Previous research has shown water quality in this area is closely related to surrounding agricultural and recreational activities21,22, but MPs in stream waters have not yet been investigated. Tey23 observed reduced MP abundance in the salmon’s gastrointestinal tracts yet elevated levels in gill tissues, indicating possible direct MPs uptake from aquatic environments. In addition, this salmon species breeds and hatches in the dry season (autumn and winter) and grows during the wet season (spring and summer). Because salmon eggs and juveniles are generally more sensitive to pollutants than adults, understanding seasonal MP patterns in these streams is critical for evaluating potential ecological risks.

This study investigates seasonal MP patterns in the Qijiawan Creek watershed by integrating MP measurements with long-term water‑quality monitoring data. The specific objectives are to (1) quantify seasonal differences in MP abundance and size distribution among upstream, midstream, and downstream sites; (2) characterize MP polymer types and shapes in relation to surrounding land‑use categories (pristine forest, recreational areas, and agricultural zones); and (3) examine associations between MPs and water‑quality parameters across wet and dry seasons using principal component analysis. The overall aim is to elucidate how rainfall and land‑use patterns jointly influence MP characteristics in an endangered salmon habitat and to provide baseline information that supports future risk assessment and management of microplastic pollution in similar freshwater ecosystems.

Materials and methods

Study area and monitoring station characteristics

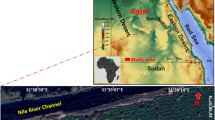

The study area (Fig. 1) is located in the Wuling region of central Taiwan, partly within Shei-Pa National Park. The Formosan landlocked salmon (Oncorhynchus masou formosanus) predominantly inhabits the Creek Qijiawan watershed, and the artificially stocked juveniles have successfully reproduced in the Creek Luoyewei. Considering representative surrounding land uses and upstream–downstream characteristics, seven monitoring stations were established for water quality and MPs analysis: Creek Taoshan West (T), upper Creek Qijiawan (Qu), middle Creek Qijiawan (Qm), lower Creek Qijiawan (Qd), Creek Gaoshan (G), Creek Yousheng (Yi), and Creek Luoyewei (L) (Fig. 1). Surrounding land uses include pristine forest around Creek Taoshan West (T) and Creek Luoyewei (L); recreational and conservation areas around Creek Qijiawan (Qu, Qm); and tourist-related facilities such as visitor centers and ecological education centers near Qd. The area between Qd and Yi experiences frequent tourist traffic, while Creek Yousheng (Yi) is characterized by intensive agricultural activities.

Illustration of the geographic locations of monitoring stations within Shei-Pa National Park, depicting areas of intensive agriculture (green), tourism and transportation hubs (purple) and lodging and camping zones with soil-based wastewater disposal (blue). The photo shows the Formosan landlocked salmon. The map was generated using QGIS v3.40.13 (https://qgis.org/) and Microsoft PowerPoint 2019. Geospatial data were obtained from the Taiwan Government Data Open Platform, including administrative boundaries24 and river networks25 (available at https://data.gov.tw/).

Water sampling and analysis methods

Water sampling and analyses were conducted following standard methods specified by the American Public Health Association (APHA) and the Environmental Protection Agency26. Due to shallow depths of the streams, samples were collected mid-stream at each station, approximately 8–10 cm below the surface. Sampling bottles were rinsed three times with stream water before collection. Immediate on-site measurements of water temperature (APHA Method 2550), dissolved oxygen (APHA Method 4500-O G), pH (EPA 9040C), and conductivity were conducted using portable instruments (HACH sension1, Metrohm 914). Samples were collected quarterly in January, April, July, and October, representing dry (January, October) and wet (April, July) seasons. Triplicate samples were collected, averaged, sealed, preserved at 4 °C, and transported to the laboratory for additional analyses. Turbidity (APHA Method 2130B) was measured with a turbidimeter (WTW TURB350IR). Silicate concentration (EPA Method 6010C) was determined by ICP-OES (Avio 200) at a specific wavelength (251.611 nm). Ion chromatography (DIONEX ICS-1500, APHA Method 4110B) quantified nitrate-nitrogen (NO₃⁻-N), sulfate (SO₄2⁻), and chloride (Cl⁻) using a DIONEX AS20 column. Nitrite-nitrogen (NO₂⁻-N) (APHA Method 4500-NO₂-B), ammonia–nitrogen (NH₄⁺-N) (APHA Method 4500-NH₃), and orthophosphate (PO₄3⁻) (APHA Methods 4500 P A, B, E) were analyzed via spectrophotometry (Perkin Elmer UV/VIS Lambda 16). Total organic carbon (TOC, APHA Method 5310B) was determined using a Shimadzu TOC-L CPH analyzer. Daily precipitation data for the 14 days preceding each sampling date were obtained from the nearby Central Weather Administration (CWA) meteorological station Taoshan. These records were used to characterize antecedent rainfall conditions during the dry- and wet-season sampling events (Table S1). A 14-day antecedent window was chosen as a pragmatic compromise between event‑scale rainfall (1–3 days) and longer‑term seasonal precipitation.

MP sampling and analysis methods

MP samples were collected during dry and wet seasons in 2024, following the same sampling protocols as water samples at 8–10 cm depth using 1 L stainless steel bottles. Samples were triplicated, transported sealed at 4 °C, and filtered in a fume hood. Glass filters (KG-25 ADVANTEC®) with stainless steel mesh (size in 1 cm x 1 cm, with a pore size of 25 µm) were pre-cleaned by sonicating in deionized water and drying in a circulating oven. Samples were shaken ≥ 25 times before filtration27. Post-filtration solids were sonicated in deionized water, dried at 59 °C, and digested with a 1:1 solution of 30% H₂O₂ and 20% KOH28,29,30. After a second filtration using stainless steel mesh, MPs (25 µm–5 mm) were characterized using µ-FTIR spectroscopy (micro-FTIR iN10, Thermo Scientific) equipped with a liquid-nitrogen-cooled linear-array MCT detector. Spectra were acquired in reflection mode over the mid-infrared region, with 16 scans at 8 cm−1 resolution. Each stainless‑steel mesh (1.0 × 1.0 cm, 25 µm pore size) was analyzed by whole‑filter ultra-fast mapping using point‑by‑point acquisition. Accordingly, the entire 1 cm × 1 cm filter area was scanned by stitching together approximately 40,000 sub-images. Spectral processing was performed in OMNIC (Thermo Scientific) for polymer identification with match score ≥ 60%. Shape and size were also assessed based on digital CCD color-resolution images, classifying particles with aspect ratios > 3:1 as fibers and others as fragments28,31,32.

MPs (≥ 0.1 µm) were additionally processed using filtration with 0.1 µm PTFE membranes, sonicated in deionized water, dried at 59 °C, digested with 30% H₂O₂27,32, and re-filtered. Samples were stained with Nile Red dye (10 µg/mL)33 and analyzed using fluorescence microscopy (Revolve microscope) with a 10 × PLAN Fluorite Phase PH1 objective (NA 0.30, WD 10 mm) under 405–500 nm excitation. Digital fluorescent images were quantified using ECHO Pro APP and Image J software27,28,32.

For the size-frequency analysis, the longest dimension of each particle was measured from the digital images. To harmonize the µ‑FTIR and fluorescence microscopy datasets and to emphasize environmentally relevant small microplastics, particles were assigned to five size classes: 5–25, 25–50, 50–100, 100–300, and > 300 µm. The 300 µm threshold was selected because MPs smaller than approximately 300 µm are increasingly recognized as a distinct “small microplastic” fraction that is often numerically dominant yet underrepresented in conventional net-based surveys, and may show enhanced bioavailability and ecological relevance in aquatic systems34,35,36.

QA & QC

Quality assurance/control included field, trip, equipment, and method blanks analyzed using Milli-Q water. All instruments and containers were pre-cleaned by sonication for 30 min (DELTA® DC600H). MP analyses exclusively utilized glass and stainless steel tools, also pre-cleaned by sonication, with blank samples processed similarly to field samples.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0.2.0 and Microsoft Excel 2019. Prior to hypothesis testing, data distributions of MP abundance and water-quality parameters were examined to verify that the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were reasonably satisfied (p > 0.05). Seasonal differences in MP abundance at each monitoring station were evaluated using paired-sample t-tests between dry and wet seasons. Spatial differences among stations were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post‑hoc tests, with statistical significance set at α = 0.05. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on z-score standardized variables (MP abundance and water-quality parameters) using OriginPro 2025 to identify underlying gradients and associations. Components with eigenvalues greater than 2.0 were retained. Fluorescence microscopy images were processed and quantified using ImageJ.

Results and discussion

Different seasonal MP abundance across stations

Figure 2 summarizes the MP abundance measured at the monitoring stations during the dry and wet seasons using µ-FTIR and fluorescence microscopy. Overall, MP levels were higher in the dry season than in the wet season. One-way ANOVA showed that MP abundance differed significantly among stations in both seasons (p < 0.05).

For the dry season, Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test distinguished four station groups (a–d). The highest concentrations were observed at downstream Creek Yousheng (Yi, 93 items/L) and downstream Qijiawan Creek (Qd, 88 items/L), both assigned to group a. The midstream station Qm (73 items/L) and tributary Creek Gaoshan (G, 71 items/L) formed group b, the upstream station Qu (59 items/L) formed group c, Creek Luoyewei (L, 51 items/L) had an intermediate status between groups c and d, and the most upstream station Creek West Taoshan (T, 48 items/L) formed group d. This pattern indicates an upstream-to-downstream increase in MP abundance during the dry season, with clear differences among stations.

For the wet season, a separate one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test likewise identified four statistical groups (a–d) specific to that season. Station Yi (72 items/L) remained in the highest-abundance group a. Station G (64 items/L) overlapped groups a and b; Qu (59 items/L) overlapped groups b and c; L (56 items/L) overlapped groups b, c, and d; Qm (52 items/L) and Qd (47 items/L) were assigned to groups c and d; and T (45 items/L) belonged to group d. Compared with the dry season, these overlapping groupings indicate reduced spatial contrasts along the main stem of Qijiawan Creek in the wet season, with statistically significant differences mainly between the most upstream (T) and downstream (Yi) stations. In Fig. 2, letter codes (a–d) denote Tukey’s HSD groups within each season; identical letters across seasons do not imply the same statistical group but are used to indicate relative differences among stations in that particular season.

Surface runoff, stormwater discharge, and atmospheric deposition are major pathways for MPs entering freshwater systems9. Although abundant rainfall facilitates terrestrial MP entry into freshwater during wet seasons by enhancing surface runoff, increasing stormwater discharge frequency, and promoting atmospheric deposition37, monitoring results from this study indicate higher total MP abundance in the dry season compared to the wet season. Paired-sample t-tests revealed significant differences between dry and wet seasons at stations Qm (p < 0.001, denoted as *** in Fig. 2), Qd (p < 0.05, denoted as * in Fig. 2), and Yi (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2).

MP composition

Figure 3 shows seasonal MP material distributions identified by micro-FTIR analysis. During the dry season, common plastics (PET 16.2%, PE 13.5%, PP 2.7%) comprised 32.4% of the total, while synthetic fibers Rayon (45.9%) and Polyester (10.8%) dominated at 56.7%. In contrast, the wet season featured predominantly synthetic fibers (Polyester 79.2%, Rayon 8.3%) with limited detection of common plastics (PA 8.3%). The dry season exhibited greater plastic diversity, possibly due to lower runoff and accumulation11. Heavy rainfall during the wet season likely facilitated loss or dilution of certain plastics, favoring lighter synthetic fibers carried by runoff38. Overall, synthetic fibers dominated MP pollution in both seasons, indicating significant anthropogenic influence. Previous studies identified PA and Polyester as major MPs in domestic wastewater39, with agriculture and fishing practices also contributing notably to PA, PE, and PET pollution40,41,42,43,44.

Shapes and sizes variation

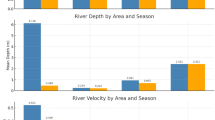

MP size and shape distributions at each station during dry and wet seasons are depicted in Fig. 4. For descriptive purposes, particles were grouped into five size classes based on their longest dimension: 5–25, 25–50, 50–100, 100–300, and > 300 µm. This classification highlights the fraction of “small microplastics” (< 300 µm), which has been shown to dominate particle counts and to warrant particular ecological concern in many aquatic environments34,35,36. The most abundant MPs ranged between 5 µm and 25 µm in both seasons. During the dry season, smaller-sized MPs predominated upstream, likely due to lower water velocities and reduced flushing capacity, facilitating deposition and retention of smaller fragments. Conversely, the abundance of larger MPs increased downstream, potentially reflecting cumulative inputs from anthropogenic sources such as urban runoff, wastewater discharge, and agricultural activities. During the wet season, increased flow velocities and runoff events substantially reduced the abundance of smaller-sized MPs, consistent with previous reports of reduced retention and enhanced transport of MPs under high-flow conditions45,46.

Notably, smaller MPs can translocate from the digestive tract to other animal tissues, predominantly when particle sizes are below 130 µm, particularly particles smaller than 10 µm47. Smaller MPs also exhibit a higher potential for trophic transfer across food webs6,8. Given that the Formosan landlocked salmon spawns and hatches during the dry season, juvenile salmon, which are more vulnerable than adults, may face heightened risks due to the prevalence of smaller-sized MPs during this period.

Fragments predominantly characterized particles smaller than 300 µm, consistent with mechanical fragmentation processes driven by environmental weathering, abrasion, and anthropogenic activities. In contrast, fibers dominated larger MPs (> 300 µm), indicating their origin primarily from textiles degradation and related sources28,39,48. These observed patterns underscore that fragment-shaped MPs are likely a result of breakdown processes of plastic products, whereas fiber-shaped MPs suggest association with clothing or other textile materials. The clear spatial and seasonal differentiation of MP shapes and sizes in this region highlights the influence of hydrological conditions and anthropogenic activity on MP distribution dynamics.

Seasonal variations in water quality at monitoring stations

Besides local geological characteristics, stream water quality can be influenced by rainfall, surrounding land-use patterns, and domestic sewage discharge. In this study, nutrient-related parameters (NO₃⁻-N, NO₂⁻-N, PO₄3⁻ and SO₄2⁻), conductivity, TOC, turbidity, DO, and temperature are interpreted primarily as indicators of anthropogenic inputs and dilution conditions, rather than as direct mechanistic drivers of MP abundance. Based on long-term monitoring data of thirteen water-quality parameters across the study area (Fig. S2), some variables exhibited clear seasonal contrasts between dry and wet periods, whereas others mainly reflected spatial differences associated with adjacent land-use types.

Figure 5 presents a heat map illustrating monthly variations in representative water-quality parameters at the seven monitoring stations. Station Yi consistently showed higher concentrations of nutrient-related parameters (conductivity, NO₃⁻, NO₂⁻, and SO₄2⁻) across all sampling seasons compared to other stations. Our previous research indicated that elevated nutrient concentrations at Station Yi primarily originated from long-term excessive fertilizer application along riverbanks22. Turbidity reached its annual peak at all stations during August (wet season), clearly reflecting soil erosion due to seasonal rainfall runoff. Additionally, phosphate and conductivity levels at downstream stations (Qu, Qm, G, Qd) in the Qijiawan watershed were slightly elevated compared to upstream Stations T, reflecting contamination from domestic sewage (PO₄2⁻) and salts derived from cooking and cleaning activities associated with nearby campsites (Fig. 1).

Figure 5 also illustrates that concentrations of water parameters related to fertilizer and domestic sewage were generally lower in the wet season (August) than in the dry season (January), except for turbidity, which peaked during the wet season at all stations. This pattern indicates that heavy rainfall enhances soil erosion and sediment input, thereby increasing turbidity, while simultaneously diluting nutrient and ion concentrations due to larger water volumes.

Daily precipitation records for the 14 days preceding each sampling date (Table S1) further support this interpretation. Before the dry-season sampling, rainfall was sparse and of low intensity, with a total of 15.5 mm. In contrast, the 14-day period prior to the wet-season sampling experienced 719.5 mm of rainfall, with several high-intensity events including a 546.5 mm day. Such extreme antecedent rainfall is expected to increase stream discharge, alter channel morphology (Fig. S1), and enhance downstream transport and dilution of dissolved and particulate constituents. The combination of elevated turbidity but reduced nutrient concentrations in the wet season is therefore consistent with strong hydrological forcing and provides important context for understanding the lower MP abundances observed during the wet season (Sect. “Different seasonal MP abundance across stations”).

Focusing further on the relationship between specific water quality parameters and surrounding land use, we conducted an ANOVA statistical analysis on the seasonal mean values obtained from the same sampling sites to eliminate seasonal effects; results are summarized in Table 1. Tukey’s HSD comparisons between sites were performed at a significance level of 0.05. Yi site showed the highest concentrations for NO₃⁻-N, NO₂⁻-N, and SO₄2⁻, categorized into group a; these compounds are major components or derivatives of agricultural fertilizers. Conversely, NO₃⁻-N, NO₂⁻-N, and SO₄2⁻concentrations at sites Qu, Qm, and Qd (mainstream of Qijiawan Creek), as well as sites L., T., and G. (upstream and tributaries), fell into groups b, c, or b&c, indicating significantly lower concentrations compared to Yi site. The predominant land-use surrounding these latter sites include camping, tourism, and pristine forest (Fig. 1). Statistical analyses combined with local land-use patterns indicate that NO₃⁻-N, NO₂⁻-N, and SO₄2⁻ concentrations sensitively reflect agricultural fertilizer impacts on stream water quality in the study area. Conductivity measurements, representing total charged chemical constituents in water, classified the agriculturally intensive Yi site into group a, the camping-intensive Qm site into group b, and the pristine forest-surrounded T site into group c. Other sites without clear differences were categorized into group b&c (Table 1). This result suggests that conductivity reflects pollution sources from both agricultural fertilizers and camping wastewater. Notably, phosphate concentrations showed no significant differences among sites at a significant level of p < 0.05, with all sites grouped similarly, suggesting consistent phosphate levels across the study area.

Seasonal variation from principal component analysis (PCA)

PCA was conducted on a subset of water quality variables, including nutrients, conductivity, TOC, turbidity, DO, temperature and MP abundance to examine spatial patterns related to anthropogenic inputs and in-stream conditions. Precipitation was excluded from the PCA due to its spatial uniformity across stations on each sampling date, rendering it irrelevant to spatial variance. Instead, antecedent rainfall was used to interpret seasonal variations in MP abundance (Sects. “Different seasonal MP abundance across stations” and “Seasonal variations in water quality at monitoring stations”). Two factors with eigenvalues greater than 2.0 were identified from the PCA for both wet and dry seasons. Factor loadings of various water parameters concentration and MPs abundance, as well as the average factor scores for each sampling site, are shown in Fig. 6. PCA clearly demonstrated seasonal differences between water parameters and MP concentrations. During the dry season, PCA accounted for 74.0% of total variance (PC1: 57.8%, PC2: 16.2%) (Fig. 6a), whereas in the wet season, PCA explained 67.6% of variance (PC1: 46.6%, PC2: 21.0%) (Fig. 6b). Higher variance explained during the dry season indicated more distinct differentiation of pollution indicators under low-flow conditions.

MPs abundances showed positive loadings on PC1 together with turbidity, conductivity, SiO₂, and TOC, suggesting that higher MP levels co-occurred with sediment resuspension, runoff, and anthropogenic pollution. In addition, DO showed an opposite loading pattern along with this axis, consistent with lower DO in more impacted reaches.

Station Yi consistently exhibited the highest positive loadings on PC1 in both seasons, strongly associated with nutrients (NO₃⁻, PO₄3⁻), TOC, Cl⁻, temperature, and MPs. Intensified agricultural activities around Station Yi likely increased these parameters, reflecting significant impacts from agricultural runoff and fertilizer overuse.

Station Qm and Qd showed moderate associations with turbidity, TOC, conductivity, and MP levels. These patterns may be related to recreational activities such as plastic waste, detergents, food residues, and personal care products from the endangered salmon viewing platform near Qm and the visitor center near Qd. Seasonal difference analyses further supported this, showing significantly higher MP abundance in the dry season at Station Qm (73 items/L dry, 52 items/L wet) and Qd (88 items/L dry, 47 items/L wet) (Fig. 2). Additionally, tourist numbers were considerably higher in the dry season (Fig. 7), further suggesting a combined contribution of agricultural runoff and tourist-generated wastewater to MP pollution in dry seasons, while agricultural activities dominated the wet-season contribution.

Station T and Qu exhibited lower pollution levels overall, reflecting lower anthropogenic disturbances and better water quality. Station G and L showed moderate pollution levels, indicating relatively balanced environmental conditions with no significant seasonal differences.

Implications for seasonal MP risk and management

The results demonstrate pronounced seasonal and spatial variation in MP abundance, composition and size distribution in the Wuling streams. These patterns indicate that both hydrological conditions and human activities shape MP characteristics, and that seasonal timing is an important consideration for future monitoring and management. In this study, potential source contributions are inferred indirectly from associations between MPs, water-quality indicators and surrounding land-use types, rather than from direct source apportionment. For example, higher MP abundance and stronger associations with nutrients, conductivity and TOC at the agriculturally dominated Yi site are consistent with contributions from farming activities, whereas the association of MPs with tourist facilities at Qm and Qd suggests an influence of recreational use. At the same time, atmospheric deposition and legacy plastics transported from outside the catchment are likely to contribute to the MPs observed in the streams and cannot be distinguished with the present data set.

Any management actions motivated by this study should therefore be considered precautionary options aimed at reducing potential future MP inputs, rather than responses to fully quantified and localized sources. During the wet season, when rainfall, runoff and turbidity are high, general measures that reduce plastic use and loss from agricultural landscapes, such as careful handling of plastic mulches and fertilizer bags, improved collection and recycling of agricultural plastics, and good housekeeping practices around farmsteads may help to limit the transport of macroplastics and MPs into the streams. During the dry season, when dilution is reduced and tourist numbers are relatively high, public education and simple behavioural interventions, e.g. discouraging single-use plastics and promoting proper waste collection and the use of environmentally friendly detergents at campsites and visitor facilities may reduce additional MP inputs from recreation. Because MP particles can persist for long periods and may originate from historical or remote sources, such seasonal measures are not expected to produce immediate reductions in MP concentrations, but rather to gradually limit new inputs.

Continued, long-term monitoring of MPs, combined with improved information on atmospheric deposition, stream discharge and flow velocities, will be essential to evaluate the effectiveness of any management strategies and to better distinguish between local and remote contributions to MP loads in endangered salmon habitats.

Conclusion

Seasonal variations in the abundance, composition, and size distribution of MPs were evident in streams supporting the Formosan landlocked salmon in the Wuling region. Higher MP concentrations and a dominance of smaller particles were observed during the dry season, whereas the wet season exhibited lower concentrations and shifts in polymer types and particle shapes. These seasonal patterns, along with spatial differences among monitoring stations, corresponded to surrounding land-use types, ranging from pristine headwaters to areas affected by agriculture and tourism. When considered alongside antecedent rainfall and water quality indicators, the findings suggest that both hydrological dynamics and anthropogenic activities shape MP distribution in this protected mountain catchment. This study provides baseline data on seasonal MP trends in an endangered salmon habitat and underscores the need for ongoing monitoring and future research integrating MP analysis with detailed hydrological and source-tracking approaches to inform long-term management of freshwater microplastic pollution.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tatsii, D. et al. Shape matters: Long-range tansport of microplastic fibers in the atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 671–682. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c08209 (2024).

Wu, C., Xiong, X., Hamidian, A. H., Zhang, Y. & Xu, X. A review on source, occurrence, and impacts of microplastics in freshwater aquaculture systems in China. Water Biol. Secur. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watbs.2022.100040 (2022).

Naderi Kalali, E. et al. A critical review of the current progress of plastic waste recycling technology in structural materials. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 40, 100763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsc.2023.100763 (2023).

Corcoran, P. L., Belontz, S. L., Ryan, K. & Walzak, M. J. Factors controlling the distribution of microplastic particles in benthic sediment of the Thames river, Canada. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 818–825. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b04896 (2020).

Thompson, R. C. et al. Lost at sea: where is all the plastic?. Science 304, 838–838. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1094559 (2004).

Wu, H., Hou, J. & Wang, X. A review of microplastic pollution in aquaculture: Sources, effects, removal strategies and prospects. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 252, 114567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.114567 (2023).

Kumar, M. et al. Current research trends on micro-and nano-plastics as an emerging threat to global environment: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 409, 124967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124967 (2021).

Qaiser, N. et al. Microplastics abundance in abiotic and biotic components along aquatic food chain in two freshwater ecosystems of Pakistan. Chemosphere 313, 137177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.137177 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Understanding the seasonal variation of the microplastics occurrence and source in the water source: upstream of the Huangpu River in Shanghai as an example. Environ. Res. 277, 121616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2025.121616 (2025).

Tian, L., Jinjin, C., Ji, R., Ma, Y. & Yu, X. Microplastics in agricultural soils: sources, effects, and their fate. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coesh.2021.100311 (2022).

Tong, N. X., Khuyen, V. T. K., Thao, N. T. T. & Nguyen, B. T. Unraveling microplastic pollution patterns in sediments of a river system: The combined impacts of seasonal changes and waterway differences. J. Environ. Manage. 371, 123348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.123348 (2024).

Jia, Q. et al. Atmospheric deposition of microplastics in the megalopolis (Shanghai) during rainy season: Characteristics, influence factors, and source. Sci. Total Environ. 847, 157609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157609 (2022).

Niu, J., Gao, B., Wu, W., Peng, W. & Xu, D. Occurrence, stability and source identification of small size microplastics in the Jiayan reservoir ,China. Sci. Total Environ. 807, 150832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150832 (2022).

Ashrafy, A. et al. Microplastics pollution: a brief review of its source and abundance in different aquatic ecosystems. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 9, 100215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hazadv.2022.100215 (2023).

Xia, F., Yao, Q., Zhang, J. & Wang, D. Effects of seasonal variation and resuspension on microplastics in river sediments. Environ. Pollut. 286, 117403 (2021).

Borriello, L. et al. Microplastics, a global issue: human exposure through environmental and dietary sources. Foods 12, 3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12183396 (2023).

Dimassi, S. N. et al. Degradation-fragmentation of marine plastic waste and their environmental implications: A critical review. Arab. J. Chem. 15, 104262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104262 (2022).

Juanes, F., Rand, P. S. & Burridge, C. P. Taiwan salmon or salmon in Taiwan? Celebrating the 100th anniversary of the discovery of Formosa landlocked salmon. Ichthyol. Res. 66, 515–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10228-019-00688-8 (2019).

Yang, C. H., Tseng, T. J., Lin, R. S. & Tzeng, C. S. The Red Lists of Freshwater Fishes of Taiwan. (Endemic Species Research Institute & Forestry Byreau, COA, EY, R.O.C. (Taiwan), 2017).

Kottelat, M. Vol. 2025 (1996).

Kuan, W., Chen, Y., Yeh, C. & Huang, Y. Integrated habitat monitoring of environmental features to site the releasing of cultivated Oncorhynchus masou formosanus. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 344, https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/344/1/012018 (2019).

Kuan, W.-H. & Chen, Y.-L. Land-use type of catchment varying nitrogen cycle in an endangered salmon inhabited stream. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 13, 971–978. https://doi.org/10.30638/eemj.2014.101 (2014).

Tey, C.-Y. Microplastic pollution risk assessment in the food chain of Creek Qijiawan. Master Program thesis, National Chung Hsing University, (2024).

National Land Surveying and Mapping Center, MOI, Taiwan. Boundaries between municipalities and counties (TWD97 latitude and longitude), <https://data.gov.tw/dataset/7442> (2015).

Water Resources Aency, MOEA, Taiwan. Rivers and waterways, <https://data.gov.tw/dataset/25781> (2017).

Rice, E. W., Baird, R. B., Eaton, A. D. & Clesceri, L. S. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. (2012).

Scircle, A., Cizdziel, J. V., Missling, K., Li, L. & Vianello, A. Single-pot method for the collection and preparation of natural water for microplastic analyses: Microplastics in the Mississippi river system during and after historic flooding. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 39, 986–995. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.4698 (2020).

Chen, Y. C. et al. Impact of seasonal changes and environmental conditions on suspended and inhalable microplastics in urban air. Environ. Pollut. 362, 124994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.124994 (2024).

Munno, K., Helm, P. A., Jackson, D. A., Rochman, C. & Sims, A. Impacts of temperature and selected chemical digestion methods on microplastic particles. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 37, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.3935 (2018).

Stock, F., Kochleus, C., Bänsch-Baltruschat, B., Brennholt, N. & Reifferscheid, G. Sampling techniques and preparation methods for microplastic analyses in the aquatic environment—A review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 113, 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2019.01.014 (2019).

Yang, J. et al. Microplastics in different water samples (seawater, freshwater, and wastewater): Methodology approach for characterization using micro-FTIR spectroscopy. Water Res. 232, 119711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2023.119711 (2023).

Zhu, X. et al. Airborne microplastic concentrations in five megacities of northern and southeast China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 12871–12881. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c03618 (2021).

Shruti, V. C., Perez-Guevara, F., Roy, P. D. & Kutralam-Muniasamy, G. Analyzing microplastics with Nile Red: Emerging trends, challenges, and prospects. J. Hazard. Mater. 423, 127171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127171 (2022).

Carbery, M. et al. How small is the big problem? Small microplastics< 300 μm abundant in marine surface waters of the Great Barrier Reef Marine park. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 184, 114179 (2022).

Medina Faull, L. E., Zaliznyak, T. & Taylor, G. T. Assessing diversity, abundance, and mass of microplastics (~ 1–300 μm) in aquatic systems. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 19, 369–384 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Preferential accumulation of small (< 300 μm) microplastics in the sediments of a coastal plain river network in eastern China. Water Res. 144, 393–401 (2018).

Wu, J. et al. Microplastic contamination assessment in water and economic fishes in different trophic guilds from an urban water supply reservoir after flooding. J. Environ. Manage. 299, 113667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113667 (2021).

Wei, L., Yue, Q., Chen, G. & Wang, J. Microplastics in rainwater/stormwater environments: Influencing factors, sources, transport, fate, and removal techniques. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2023.117147 (2023).

Browne, M. A. et al. Accumulation of microplastic on shorelines woldwide: Sources and sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 9175–9179. https://doi.org/10.1021/es201811s (2011).

Kumar, M. et al. Microplastics as pollutants in agricultural soils. Environ Pollut 265, 114980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114980 (2020).

van Schothorst, B., Beriot, N., Huerta Lwanga, E. & Geissen, V. Sources of light density microplastic related to two agricultural practices: The use of compost and plastic mulch. Environments https://doi.org/10.3390/environments8040036 (2021).

Sharma, S., Bhardwaj, A., Thakur, M. & Saini, A. Understanding microplastic pollution of marine ecosystem: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 31, 41402–41445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-28314-1 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. Seasonal variation and risk assessment of microplastics in surface water of the Manas river basin, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 208, 111477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111477 (2021).

Xiong, X., Xie, S., Feng, K. & Wang, Q. Occurrence of microplastics in a pond-river-lake connection water system: How does the aquaculture process affect microplastics in natural water bodies. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131632 (2022).

Dris, R. et al. Microplastic contamination in an urban area: A case study in Greater Paris. Environ. Chem. 12, 592–599. https://doi.org/10.1071/EN14167 (2015).

Horton, A. A., Svendsen, C., Williams, R. J., Spurgeon, D. J. & Lahive, E. Large microplastic particles in sediments of tributaries of the River Thames, UK–Abundance, sources and methods for effective quantification. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 114, 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.09.004 (2017).

Covernton, G. A. et al. Large size (>100-mum) microplastics are not biomagnifying in coastal marine food webs of British Columbia. Canada. Ecol Appl 32, e2654. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2654 (2022).

Cole, M., Lindeque, P., Halsband, C. & Galloway, T. S. Microplastics as contaminants in the marine environment: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 62, 2588–2597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.09.025 (2011).

Funding

The authors are appreciative of the Shei-Pa National Park, Taiwan for supporting this work with Grant No. PG11212-0178.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tsan-Yang Hu: Writing—original draft, Visualization, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Wen-Hui Kuan: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, TY., Kuan, WH. Seasonal rainfall and land-use impacts on microplastic characteristics in an endangered salmon stream. Sci Rep 16, 3590 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33600-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33600-8