Abstract

The eastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is renowned for its deep gorges and significant tectonic activities, which makes it a region prone to the formation of natural dams. However, there are limited studies focusing on the stable natural dams in this area. To elucidate the distribution of stable natural dams and the factors contributing to their long-term stability, we established an inventory of stable dams with the aid of remote sensing mapping and detailed field investigations. The findings indicated that there are at least 348 stable natural dams within the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, comprising 294 current natural dams and 54 paleo natural dams. The origins of these stable natural dams included rock avalanches (36.5%), rock slides (7.7%), rock falls (23%), and moraine (32.8%). We summarized six types of stable dam geomorphometry. The origin types contributing to the formation of stable landslide dams include rock avalanches, landslides, and glacial moraine damming events. This leads to the formation of dam structures categorized as follows: inverse grading from high-speed long-runout landslides, slipped or seated pseudo-bedrock structures from short-runout landslides, boulder-dominated architectures from proximal avalanche river-blocking events, and soil-rock matrices resulting from damming by interbedded soft-hard rock sequences or heterogeneous deposits. The structural configuration of the dam plays a critical role in ensuring the long-term stability of landslide dams.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the Indian Plate continues to collide with the Eurasian Plate, the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau has emerged as the highest plateau in the word1,2. This tectonic activity has contributed to the eastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau becoming a globally recognized area characterized by deep gorges. During the ongoing uplift of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, the slopes slowly deform, and the rock gradually deteriorates, especially along the eastern margin. As a result of the combined effects of earthquakes, rainfall, and glaciation, fractured rock masses lead to landslides and other mass movements that can obstruct river flows, ultimately resulting in the formation of natural dams. In addition, numerous moraine resulting from the global warming has also contributed to the blocking of rivers to form dammed lakes in the eastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. These dammed lakes are particularly susceptible to the formation of deep valleys and the catastrophic flooding, which poses significant risks to downstream areas.

Historically, numerous natural dam failures have been documented on the eastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. For example, the 1786 Ms 7.75 Moxi earthquake triggered the Mogangling landslide, which blocked the Dadu River. This dam subsequently failed after ten days, resulting in more than 100,000 fatalities downstream3,4. This event may represent the highest recorded casualty count associated with a natural dam breach. Similarly, the 1933 Ms 7.5 Diexi earthquake caused three natural dams to form, which blocked the Minjiang River; one of these dams failed after 45 days, resulting in a minimum of 2,500 deaths downstream4,5,6. The notorious Tangjiashan dam, formed during the 2008 Ms 8.0 Wenchuan earthquake, threatened the lives of millions in Mianyang city7,8,9. Furthermore, statistical analyses from various scholars indicate that natural dams typically have a short lifespan, with most existing for less than one year10,11,12,13. However, some natural dams on the eastern margin of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau have existed for extended periods. They not only avoid catastrophic floods but also positively influence fluvial geomorphology and ecological environment. For example, three natural dams have existed for more than 1,000 years in the Shenxi Gully, which is located on the tributary of the Minjiang River and near the Yingxiu-Beichuan fault. The longevity of these dams has resulted in the formation of a knickpoint in the river profile, which effectively protects the upstream slope from continuous erosion14. Consequently, no geological disasters occurred upstream of these natural dams during the 2008 Ms 8.0 earthquake14. A similar phenomenon was also observed upstream of Dahaizi dam in Diexi town during the Wenchuan earthquake6. The Mahu dam has existed for at least 4,200 years in Leibo County, which regulates the local microclimate required to increase the yields of vegetables and fruits15,16. Additionally, the Mahu dam serves as a summer resort that attracts tens of thousands of tourists annually.

Following the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, which triggered numerous unstable natural dams, research has increasingly focused on the failures of these natural dams on the eastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau17,18,19,20,21. However, due to the long-term stability of certain natural dams, there has been limited investigation into their characteristics22,23,24,25. Currently, management measures for natural dams in this area often prioritize their rapid removal through manual excavation and blasting. Nonetheless, not all dams pose a risk of catastrophic flooding. Given the numerous benefits associated with stabilizing natural dams, some studies advocate for their preservation26,27. Thus, it is imperative to clarify the distribution of stable natural dams and the reason behind their long-term stability.

The eastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is characterized by intense tectonic activity, mega-earthquake, deeply incised valley, and extensive glacial deposits, which creates favorable conditions for the formation of the numerous stable natural dams. A comprehensive understanding of the spatial distribution, reason, and fundamental conditions for the formation of long-term natural dams in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau will be beneficial for future natural dam management. This study aimed to reveal the distribution of long-term natural dams and their associated characteristics on the eastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau through remote sensing interpretation and long-term field investigations.

Regional geological background

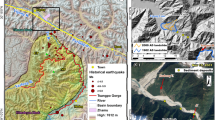

The study area is located at the eastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and covers an area of 54.76 × 104 km2 (Fig. 1a). Seven major rivers traverse the study area from west to east, including the Yarlung Zangbo River, Nujiang River, Langcang River, Jinsha River, Yalong River, Dadu River, and Minjiang River (Fig. 1a). The depths of these river valleys typically exceed 400 m and exhibit distinct deep valley features28,29,30. The rock mass along the riverbank has been undergoing continuous deterioration due to intense tectonic activity, frequent seismic events, and long-term weathering31,32. The overall topography of the study area exhibits a pattern of higher elevations in the north and west and lower elevations in the south and east. Specifically, the central and western regions of the study area exceed 3,500 m in elevation, while the eastern region predominantly lies below this threshold (Fig. 1b).

Location and topographic features of the study area. (A) – Location and major rivers in the study area; (B) – Detailed topographic features of the study area. This map was created using ArcGIS 10.3 (URL: https://desktop.arcgis.com).

As the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau continues to rise, the study area has gained recognition as a globally significant tectonically active region33,34. According to Deng’s35 classification of tectonic subblocks within the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, the study area encompasses four subblocks: Lhasa, Qiangtang, Baryan Har, and Chuan-Dian (Fig. 2A). Additionally, the area intersects at least 35 fault zones (Fig. 2B), including notable active fault zones such as the Yarlung Zangbo fault zone (F35), Jiali fault zone (F33), Nujiang fault (F31), Lancangjiang fault zone (F30, sinistral strike-slip: 5.1 mm/yr), Jinshajiang fault zone (F28, stike-slip: 5 mm/yr), Batang fault zone (F26, stike-slip: 2–4 mm/yr), Ganzi-Litang fault zone (F17, sinistral strike-slip: 5.4–14 mm/yr), Xianshuihe fault zone (F8, sinistral strike-slip: 7.9–10 mm/yr), and Longmenshan fault zone (F1 − 3, thrust and dextral strike-slip: 0.14–1 mm/yr and 1.67–8 mm/yr, respectively).

Regional geological background of the study area. (A) – Regional tectonic units and seismic belt features; (B) – Regional active fault zone features; (C) – Historical earthquake and peak ground accelerations features. S1 - Himalayan seismic belt; S2 - Kangding-Ganzi seismic belt; S3 - Wudu-Mabian seismic belt. F1 – Guanxian-Anxian fault zone; F2 – Yingxiu-Beichuan fault zone; F3 – Maowen fault zone; F4 – Minjiang fault zone; F5 – Xueshan fault zone; F6 – Huya fault zone; F7 – Ganluo-Zhuohe fault zone; F8 – Xianshuihe fault zone; F9 – Xiaojinhe fault zone; F10 – Maerkang fault zone; F11 – Sahde fault zone; F12 – Yunongxi fault zone; F13 – Mula fault zone; F14 – Cazhong fault zone; F15 – Litang-Dewu fault zone; F16 – Litang-Yidun fault zone; F17 – Ganzi-Litang fault zone; F18 – Zengke-Shuoqu fault zone; F19 – Dege-Xiangcheng fault zone; F20 – Maisu fault zone; F21 – Ganzi-Yunshu fault zone; F22 – Zaga-Chuma fault zone; F23 – Qingshuihe fault zone; F24 – Niqu fault zone; F25 – Yuke fault zone; F26 – Batang fault zone; F27 Dingquhe fault zone; F28 – Jinshajiang fault zone; F29 – Xiongsong-Suwalong fault zone; F30 – Langcangjiang fault zone; F31 – Nujiang fault; F32 – Baqing-Leiwuqi fault zone; F33 – Jiali-Chayu fault zone; F34 – Magnon fault zone; F35 – Yarlung Zangbo fault zone; The regional tectonic units are from Deng35; the historical earthquake data is from the China Earthquake Network Center (http://news.ceic.ac.cn/) and the PGA is from the GB18306-201536. This map was created using ArcGIS 10.3 (URL: https://desktop.arcgis.com).

The study area is characterized by three seismic belts: the Himalayan seismic belt (S1), Kangding-Ganzi seismic belt (S2), and Wudu-Mabian seismic belt (S3, Fig, 2 A). The activity of these fault zones has resulted in a series of earthquakes within the area (Fig. 2C). For instance, the activity of the Longmenshan fault zone triggered the 2008 Wenchuan Ms 8.0 earthquake, which led to the formation of at least 828 natural dams in the study area18. Historical records indicated that at least 13 strong earthquakes with magnitude exceeding 7.0 occurred in the study area (Fig. 2C). The peak ground accelerations (PGA) also exhibit high intensity, and their values are often not less than 0.15 g (Fig. 2C).

Methodology

Scholarly perspectives on the existence and longevity of stable natural dams vary37,38,39. This study adopted the Kroup’s definition of stable natural dams40, which categorized those that have existed for more than 10 years as stable and long-term. The focus of this study encompassed both current and paleo natural dams. To accurately identify long-term natural dams within the study area, we employed a methodology that integrates detailed remote sensing interpretation with long-term field investigation.

Recognition of the existing stable natural dams

A defining characteristic of long-term natural dams is the persistence of a lake surface. Compared with traditional manual visual remote sensing interpretation, remote sensing analysis of water surfaces significantly reduces the workload. A previous study constructed a comprehensive global surface water mapping database spanning 32 years at a 30-meter resolution by using three million Landsat satellite images41. This study utilized JavaScript code in Google Earth Engine (GEE) to access the interpretation results from the database. The water surfaces present for more than 10 years (2010 to 2020) in the study area were marked in yellow (Fig. 3A). It is important to note that not all yellow-marked surfaces correspond to long-term natural dams, and most of them are natural lakes and rivers. Hence, to ascertain whether the yellow-marked surfaces represent long-term natural dams, high-resolution remote sensing data from Google Earth was employed for verification42,43. Ultimately, a surface water formed by the damming of a river by rock avalanche, landslide, or moraine deposits was classified as a long-term natural dam (Fig. 3B and C, and 3D).

Long-term natural dam mapping in study area. A – Spatial distribution of impossible current long-term natural dam; B, C and D – Example of the typical natural dam; E – Fluvial geomorphology features of the paleo long-term natural dams; F and G – Lacustrine deposit features of the paleo long-term natural dams. This map was generated using Google Earth (URL: https://www.google.com/intl/zh-cn/earth/index.html).

Recognition of the paleo stable natural dams

Paleo stable natural dams, which have existed for hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of years, can leave significant traces on fluvial geomorphology and upstream areas. Firstly, potential paleo stable natural dams were identified using high-precision remote sensing from Google Earth. If a natural dam has existed for a long time, the head scarp of the paleo natural dam typically exhibits a circular chair shape in the geomorphology. Fluvial geomorphology often shows river channels that are squeezed and narrowed, with accumulation platform preserved on both sides of the river channels (Fig. 3E). Secondly, a field investigation was conducted in the study area for several years. If a paleo natural dam has existed for an extended period, lacustrine deposits should be preserved upstream (Fig. 3F and G). Field investigations were conducted in the study area over several years.

Results

Spatial distribution of long-term stable natural dams

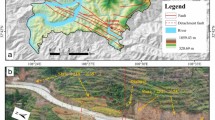

The results of the remote sensing interpretation and detailed field investigations indicated that there are at least 348 stable natural dams in the inventory (Fig. 4A and B). Among them, 54 were classified as paleo stable natural dams that historically blocked rivers and developed deep lacustrine deposits behind them. Currently, 294 long-term natural dams are still obstructing rivers.

The spatial distribution of stable natural dams revealed a pronounced non-uniformity across basins (Fig. 4B). More than 76.1% of long-term natural dams are concentrated in eight basins: Yalung Zangbo River (89 natural dams, 25.6%), Minjiang River (43 natural dams, 12.4%), Jinsha River (38 natural dams, 10.9%), Nujiang River (37 natural dams, 10.6%), Dadu River (30 natural dams, 8.6%), and Yalong River (28 natural dams, 8%). Among these, the current and paleo stable natural dams distributed along the Yarlong Zangbo River and the Minjiang river are the most prevalent, totaling 86 and 20, respectively.

Gaussian kernel density estimation of existing long-term natural dams indicated the presence of eight concentration zones (see zones Ⅰ-Ⅷ in Fig. 4C). A total of 135 long-term natural dams are concentrated in these zones, which account for 38.7% of the total. Zones Ⅰ-Ⅷ are located in the Bailong River section, Minjiang River section, Dadu River section, Jinsha River section, Yalung Zangbo River section, and Niyang River section. Notably, four zones are primarily located in the Minjiang River (Ⅱ and Ⅲ) and the Yalung Zangbo River (Ⅵ and Ⅶ).

Spatial distributions of existing long-term natural dams in the study area. A – Basic spatial distribution characteristics; B – Statistical results of long-term natural dams divided by basin; C – Non-uniform spatial distribution and concentration zones of long-term natural dams. 1 – Bailong River; 2 – Fujiang River; 3 – Tuojiang River; 4 – Minjiang River; 5 – Tsing Yi River; 6 – Dadu River; 7 – Yalong River; 8 – Jinsha River; 9 – Langcang River; 10 – Nujiang River; 11 – Chayu River; 12 – Niyang River; 13 – Irrawaddy River; 14 – Parlung Zangbo River; 15 – Yigong Zangbo River; 16 – Yalung Zangbo River. This map was created using ArcGIS 10.3 (URL: https://desktop.arcgis.com).

Origins of stable natural dams

Based on detailed field investigations and the landslide classification by Cruden and Varnes44 and Hungr et al.45, there were three main types of landslide that blocked rivers to form stable natural dams in the study area. The origins of stable natural dams included rock avalanches (RA, Fig. 5A), rock slides (RS, Fig. 5B), and rock falls (RF, Fig. 5C). In addition, due to the impact of global warming, it is common for moraine at higher altitudes in the study area to block river channels, thereby forming stable natural dams (MD Fig. 5D). The proportions of rock avalanches and moraine that blocked rivers to form stable natural dams were the highest, at 36.5% and 32.8%, respectively (Fig. 5E). The contributions of rock falls and rock slides were comparatively lower, at 23% and 7.7%, respectively (Fig. 5E).

In the case of rock avalanches forming stable natural dams, large rock masses disintegrated during earthquakes, which resulted in fragmented rocks that can travel considerable distances and ultimately block rivers. Rock slides that form stable natural dams usually have relatively intact rock structures and are caused by strong seismic activity. Rock avalanches feature long travel distances, while rock slides are characterized by shorter travel distances. The significant freeze-thaw cycles at high altitudes in the study area often damage the integrity of the slope. The intense seismic activity can lead to the disintegration of the slope, resulting in rock falls that contribute to the formation of stable natural dams. Typically, the dam bodies formed by rock falls mainly consist of giant boulders. Furthermore, glaciers at higher altitudes can erode rock masses within the channels during their movement, which easily leads to the accumulation of debris that forms stable moraine-natural dams.

Typical origin types of stable natural dams in the study area. A – Rock avalanche; B – Rock slide; C – Rock fall; D – Moraine dam. This map was generated using Google Earth (URL: https://www.google.com/intl/zh-cn/earth/index.html).

Geomorphic classification of the stable natural dam

The interaction between fragmented rock runout and local topography allows deposits to form dam bodies capable of holding back water above the ‘normal’ river level39. The morphological classifications of dam bodies, which are established based on the relationship between the shape and size of the dam body and the dimensions of the blocked valley, are widely accepted10,39. Costa and Schuster10 first proposed a geomorphic classification of dam bodies based on a statistical analysis of 225 worldwide case studies. The geomorphic classification of dam bodies forming the natural dams in the study was summarized accordingly.

This paper proposes a geomorphic classification comprising six types of dam bodies that form stable natural dams in the study area (i.e., types Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, Ⅳ, Ⅴ, and Ⅵ) (Table 1). The geomorphic classifications of Type I, II, III, and IV are consistent with those proposed by Costa and Schuster10. Types V and VI are proposed in this study. Unlike Costa and Schuster’s10 classification, which focused solely on landslide dams, our classification also included moraine dams. Detailed information on the geomorphic classifications of stable dam bodies is provided in Table 1.

Structural characteristic of stable natural dams

Through field investigations, geophysical interpretation, and comprehensive analysis, the structural types of stable landslide dams in the study area can be categorized into four types: (1) Reverse grading structure formed by far-source (high-position) high-speed landslides damming rivers (Fig. 6A1); (2) Sliding or seated pseudo-bedrock structure formed by short-travel landslides (Fig. 6B1); (3) Earth-rock mixture structure formed by river blockage from interbedded hard and soft rock masses or deposits (Fig. 6C1); (4) Giant boulder structure formed by near-source collapse damming rivers (Fig. 6D1).

Structural characteristics of stable landslide dams in the study area. (A1) – Schematic diagram of a landslide dam with inverse grading; (A2, A3) – A typical landslide dam exhibiting inverse grading and its characteristic features; (B1) – Schematic diagram of a landslide dam with a pseudobedrock structure; (B2, B3) – A typical landslide dam with a pseudo-bedrock structure and its characteristic features; (C1) – Schematic diagram of a boulder-dominated landslide dam; (C2, C3) – A typical boulder-dominated landslide dam and its characteristic features; (D1) – Schematic diagram of a landslide dam with a soil-rock mixture structure; (D2, D3) – A typical landslide dam with an SRM structure and its characteristic features.

The stable landslide dam with an inverse grading structure is typically characterized by a distinct vertical heterogeneity of the particle size distribution, meaning that the dam structure exhibits a coarser upper part and a finer lower part in the vertical profile (Figs. 6A2 and A3). Numerous stable landslide dams exhibiting such inverse grading have been identified within the study area. Representative examples include the Wenxian Tian landslide dam, the Batang Conaxueco landslide dam, the Diexi Baishihai quartz sandstone interbedded with slate landslide dam, and the Changhaizi stable landslide dam.

The pseudo-bedrock structure in stable landslide dams is typically characterized by the preservation of large, relatively intact rock blocks that retain the original stratigraphic sequence of the source slope (Figs. 6B2 and B3). This structure typically forms when the landslide’s shear outlet is located at a low elevation, and the slope structure is predominantly dip-slope. During the short-distance movement, the confined space of the narrow valley restricts the disintegration of the sliding mass. As a result, large segments of the rock mass remain comparatively intact and rapidly block the river, forming the dam. Consequently, landslide dams formed by low-elevation (proximal) landslides often exhibit a pseudobedrock structure that closely resembles the original stratigraphic and structural configuration of the source slope.

Stable boulder-dominated landslide dams are characterized by a dam body composed of numerous extremely large rock blocks. This structure typically originates from slopes exhibiting well-developed joint systems, such as transverse slopes (where joint sets intersect the slope face at a high angle) or obsequent slopes (where the dip direction of bedding planes opposes the slope direction). Under seismic activity or gravitational forces, the intensely jointed rock mass undergoes detachment, disintegrating into isolated boulders and large blocks that ultimately obstruct the river channel, forming the landslide dam (Figs. 6C2 and C3). According to the classification of dam structures proposed by Casagli and Ermini46, the boulder-dominated structure falls under the clast-supported type, wherein the large rock blocks are in mutual contact, forming a stable framework with high porosity and permeability.

Furthermore, stable landslide dams with a soil-rock mixture structure are also developed within the study area. Their formation can be attributed to two primary mechanisms: (1) The first mechanism involves blocks of hard rock plowing into and incorporating loose colluvial or slope-wash deposits along their path. Due to the spatial constraints of the river valley, the landslide did not evolve into a high-speed, long-runout event. Consequently, the hard rock blocks became entrained within a large volume of loose fine-grained material, collectively blocking the river and forming the dam; (2) The second mechanism occurs when the landslide is composed of interbedded hard and soft rocks. During movement, the less competent layers are readily crushed into fine particles. These fines, mixed with more resistant rock blocks, can also effectively block the river, resulting in a stable dam of soil-rock mixture structure. According to the classification of dam material structures by Casagli and Ermini46, the structure corresponds to a matrix-supported type. In this type, the rock blocks are not in mutual contact but are instead suspended within and supported by the finer-grained matrix (Figs. 6D2 and D3). Matrix-supported dams generally exhibit lower stability compared to their clast-supported counterparts due to the controlling influence of the weaker matrix on the overall shear strength.

Discussion

The reasons for the long-term stability of natural dams

Numerous studies have indicated that the internal structure of a landslide dam plays a decisive role in its stability47,48. Therefore, this paper selects typical cases of stable landslide dams from the study area, specifically those exhibiting inverse grading, pseudobedrock, and boulder-dominated structures, to preliminarily explore the mechanisms underlying their stability from a structural perspective. While these selected cases of stable landslide dams exhibit individual differences, they are not isolated phenomena. Rather, for those sharing the same dam structure type, commonalities exist in their stabilizing mechanisms.

Particularly, landslide dams with a soil-rock mixture structure are generally more prone to failure. Nevertheless, some stable dams of this type persist in the study area, primarily due to their exceptionally large volume and the relatively small catchment area upstream—fundamental conditions that contribute to their prolonged stability. It is important to note that the structure itself contributes minimally to the overall stability of these dams. Therefore, this type of dam structure is not analyzed further in this study.

Inverse grading structures

The Conaxue Co landslide dam is a representative example of a stable dam with an inverse grading structure within the study area. It is located in Batang County, Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, with geographic coordinates of E99°31′56.6″, N30°11′54.6″ (Fig. 7A). Under the influence of intense seismic activity, the slope rock mass—composed of Late Yanshanian granite on both banks—underwent failure and initiated a high-speed, long-runout movement. The resulting disintegrated materials from both sides converged within the Kangrilongba Valley. Ultimately, obstructing the river and forming the Conaxue Co landslide dam (Fig. 7B). Field investigations reveal that the deposit of the Conaxue Co dam exhibits a distinct inverse grading structure. The surface layer of the dam is predominantly composed of extremely large boulders, while the lower portion consists mainly of crushed rock, angular gravel, and fine-grained sandy soil (Fig. 7C).

Similar to numerous high-speed long-runout landslides, the blocky deposit of the Conaxue Co landslide dam underwent vibrational sorting and compaction during its movement. This process resulted in a highly dense, fine-grained layer at the base of the dam, which exhibits low permeability and acts as a relatively impermeable aquitard. This layer prevents the Conaxue Co lake from drying up during dry seasons by minimizing water seepage. Meanwhile, the large boulders distributed across the upper part of the dam and within the spillway significantly alter the flow patterns when overtopping occurs. As water flows over these boulders, it generates intense turbulence and exerts substantial drag forces on the channel bed. However, the abundant large boulders distributed across the spillway bed possess high erosion resistance, effectively mitigating scour of the underlying fine-grained materials and thus providing protection to the basal layer of the dam (Fig. 7D).

Furthermore, a step-pool system formed by long-term fluvial transport of large boulders was identified within the spillway (Fig. 7E). This system consists of a series of alternating steep and gentle slopes connected with plunge pools, creating a cascading morphology. It has been extensively documented that such systems exhibit exceptionally high flow resistance, effectively dissipating stream energy and thereby mitigating erosion in the spillway channel49,50. In the case of the Conaxue Co landslide dam, energy dissipation within the step-pool system primarily occurs through two mechanisms: step-related dissipation and pool-related dissipation. Step-related dissipation mainly involves two processes: skin friction and hydraulic jumps downstream of the steps. As water from the Conaxue Co lake flows over the steps, it interacts with the large boulders in the spillway, generating substantial frictional and form drag that dissipates energy. Subsequently, the flow is aerated and deflected at the step edges, forming hydraulic jumps and generating vortices that further dissipate energy (Fig. 8A). Unlike the large jumps in pools, these are relatively small-scale hydraulic jumps occurring on the step surfaces. Pool-related dissipation comprises three sequential mechanisms: first, energy is dissipated through hydraulic jumps in the main flow zone of the pool; second, significant kinetic energy is converted into turbulent energy at the interface between the main flow and the surrounding water; finally, large-scale vortices formed along both sides of the main flow zone transfer energy to smaller-scale turbulent eddies, further enhancing energy dissipation (Fig. 8B). As a result, the stream energy is significantly attenuated after passing through the step-pool system, contributing to the long-term stability of the Conaxue Co landslide dam.

Energy dissipation mechanisms of the step-pool system in the spillway of the Conaxue Co landslide dam. A – Schematic diagram of step-related energy dissipation; B – Schematic diagram of pool-related energy dissipation. (1) – Skin friction and form drag; (2) –hydraulic jumps; (3) –Main flow zone of hydraulic jump; (4) – Interface region; (5) – Large-scale vortex region.

To quantitatively calculate the energy dissipation rate of the step-pool system formed by the Conaxue Co dam, we employed the energy dissipation rate formula derived from experiments and field data by Lenzi51 and Wang et al.52 The specific calculation formula is as follows:

where η is the energy dissipation rate of the step-pool system, hc is the critical water depth (m), Hs is the step height (m), Q is the flow rate (m3/s), W is the river width (m), and g is the gravitational acceleration (m/s2).

Field investigations revealed that flow rate of the river through dam is 1.5 m3/s, the step height is 1.5 m, and the average width of the spillway is 20 m. Based on this data, we calculated that the energy dissipation rate of the step-pool system in the spillway of the Conaxue Co dam is 0.68, indicating that 68% of the river’s energy is dissipated by the step-pool system. This high energy dissipation rate underscored the crucial role of the step-pool system in maintaining dam stability.

Pseudo-bedrock structures

The Xiaohaizi dam serves as a representative case of rock slide dam, which is located in Maoxian County, Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, with the geographical coordinates of E103 °40 ′48.54 ″, N32 °2 ′27.88 ″. This stable natural dam was formed by the 1933 Diexi Ms 7.5 earthquake, which caused extensive damage to the Triassic metamorphic sandstone intercalated slate (T2z) in the area (Figs. 9A and B).

Detailed field investigation, combined with existing drilling data, revealed that the structure of Xiaohaizi dam is a layered pseudo-bedrock. The dam is primarily composed of metamorphic sandstone intercalated with slate of the Triassic Zhuwo Formation (T2z, Fig. 10B). Due to the thick paleo natural dam sedimentary layer covering the dam’s surface, the layered pseudo-bedrock structure is only visible in the Jiaochang area near the Minjiang River. The pseudo-bedrock exposed on one side of the field has an incidence of 85°∠26°, with a reverse slope (Fig. 9C and D).

Regional setting and structure characteristics of the Xiaohaizi dam. A – Regional setting; B – Profile of the dam; C, D – The pseudo-bedrock structure of the dam. 1 – Local scarp; 2 – Dam deposits; 3 –Pseudo-bedrock; 4 - Metamorphic sandstone interbedded rock of Triassic Zhuwo Formation; 5 – Water line of the paleo natural dam; 6 – Original surface (inferred).

This study analyzed the role of the pseudo-bedrock structure during the stable existence period of the landslide dam using the evolution of the Xiaohaizi paleo natural dam from its formation to its current state as an example.

Following the strong earthquake, the slopes along the layer in the Diexi Paleo Town experienced short-distance movement and blocked the Minjiang River. As upstream water continued to flow into the natural dam, the lake water overflowed the dam top and formed a spillway at a relatively low-lying location for discharge (Fig. 10A). The Xiaohaizi dam’s layered pseudo-bedrock structure provided resistance to river erosion comparable to that of bedrock. The extensive thick lacustrine sedimentary layers on the Jiaochang Terrace and upstream are direct evidence of the river’s slow erosion of the “pseudo-bedrock” structure of the dam body. The paleo dam has existed for approximately 15,000 years26. The horizontal stratification of the lacustrine phase indicated that the natural dam was situated in a static water environment at that time (Fig. 11). Over time, the river eroded through the layered pseudo-bedrock of the dam body, resulting in the formation of a deep gorges geomorphology (Fig. 10B). Subsequently, the 1933 Diexi Ms 7.5 earthquake revived the paleo dam deposits in the Jiaochang area to block the Minjiang River once more. However, due to the existence of a layered pseudo-bedrock structure within the dam, the Xiaohaizi dam has remained intact for over 90 years (Fig. 10C). Therefore, the existence of the pseudo-bedrock structure of the Xiaohaizi dam significantly slows down the river’s downcutting, which allows the river water to flow over the dam’s top without causing overflow damage to the dam.

Schematic diagram of the role of the pseudo-bedrock structure in the evolution of the Diexi dam. A – The paleo dam that has existed for 15,000 years; B – The stage when the river cuts through the paleo dam; C – The 1933 Diexi Ms 7.5 earthquake revived the paleo dam to block the river, and the river cuts through the pseudo-bedrock structure layer of the dam again.

Boulder-dominated structures

The Mugecuo dam represents a typical case of a rock fall dam, located in Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, with geographical coordinates of E101 °51 ′52.7 ″, N30 °9 ′12.1 ″. The Mugecuo dam was formed by the rock fall of medium-coarse granite slope rock mass on the right bank of the river, which was mainly formed in the late Yanshannian period (\(\:{{\upgamma\:}{\upbeta\:}}_{5}^{3}\)), under the influence of a strong earthquake (Fig. 12A). The landslide deposits on the left bank of the river contribute to channel obstruction, which allows the river water to flow out through the lower elevations of rock fall deposits (Fig. 12B). A detailed field investigation of the Mugecuo landslide dam revealed that during dam formation, the rock mass fell from the source area, collided with the slope, and disintegrated into numerous huge boulders that subsequently blocked the river to form a giant-grained dam (Fig. 12C and D).

Detailed field investigation and comprehensive analysis indicated that the giant-grained structure formed by the rock fall of hard rock plays a crucial role in the long-term preservation of the dam. Unlike the inverse grading structure of rock avalanche dam, which primarily feature huge rocks at the top, the giant-grained structure dam is entirely composed of huge boulders. On the one hand, these huge boulders significantly dissipate the energy of the river water. The flame-like trace left on the surfaces of the boulders scattered throughout the spillway of the Mugecuo dam provide strong evidence of their energy-absorbing capabilities (Fig. 12E). On the other hand, the composition of the Mugecuo dam consists of particle support formed by boulders, with large gaps between them. In the early stage of the formation of the Mugecuo dam, the large gaps in the dam body allowed river water to flow through the dam body more easily from the upstream, thus reducing the likelihood of overflow. This characteristic mitigated the risk of overflow due to poor drainage of the dam, while the existence of huge boulders minimized the potential for seepage damage, thus providing favorable conditions for the long-term stability of the Mugecuo dam. In summary, the giant-grained structure is vital for the stability of the dam body formed by rock falls.

Soil-rock mixture structure

The Rcuogencuo dam exemplifies a typical moraine dam, which is also located in Batang County, Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, with geographical coordinates of E99 ° 44 ′ 24.98 ″ and N30 ° 09 ′ 26.47 ″. The formation of the Ruogencuo dam resulted from the movement of moraine deposits form higher altitude areas to lower altitude areas that blocked the river channel (Fig. 13A).

During the movement of glaciers, the rock mass within the channel underwent erosion and abrasion, leading to the formation of the Ruogencuo dam. Consequently, the structure of the dam is characterized by a soil-stone structure (Figs. 13B, C, and D). Compared with the aforementioned three types of dam structures, the stability of the soil-stone structure of the Ruogencuo dam is the weakest. In the early stage of the formation of the moraine dam, the poor permeability of the soil-stone structure could lead to river overtopping at the relatively low-lying position on the dam surface. As the river water continued to erode the dam, fine soil particles within the dam were washed away, while the boulders of stone particles were left in the spillway (Figs. 13B and C). These huge boulders that fill the spillway provided significant resistance to river erosion, thus maintaining the stability of the moraine dam.

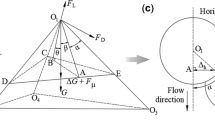

When river flow reaches a certain velocity, large particles within the dam may also be activated. To quantitatively explore the relationship between river flow velocity and rock particle size, a rock particle located on the surface of the moraine dam was selected for force analysis. As depicted in Fig. 14, the force diagram confirmed that the particle is subjected to four forces: frictional resistance (Fr), seepage force (Fp), drag force (Fd), and effective stress (Fg)53.

The expressions for Fd, Fp Fw and Fr are as follows:

where Cd is the thrust coefficient; ρw is the density of water (g/cm3); ub is the river flow velocity (m/s); d is the diameter of the rock particle; g is the gravitational acceleration (m/s2); i is the hydraulic gradient; e is the porosity; ρs is the particle density; Φ is the internal friction angle (°); β is the slope of the downstream slope of the dam (°); α is the angle between the seepage force and the horizontal direction (°).

Using the principle of static equilibrium, the force analysis of the particles yields the following results:

Substituting Eqs. (8)-(11) into Eq. 12 yields the relationship between river velocity and rock particle size:

It can be concluded from the formula that, for identified geometric characteristics of the moraine dam, the erosion of specific particles depends on the river flow rate. The higher the river flow rate, the larger the particle size of dam body that can be activated.

Limitations and perspectives

This paper elucidated the reasons for the long-term stability of natural dams on the eastern edge of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau from the perspective of dam structure through field investigation and comprehensive analyses. However, current research predominantly examined dam stability from a macroscopic viewpoint and lacked methodologies such as flume experiments and fluid-solid coupling numerical simulation to analyze the stability of long-term natural dams formed by various origins from a mesoscopic perspective. Addressing this gap is an objective for future research. In addition, the age of paleo-landslide dams also requires further investigation in future studies.

Conclusions

The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is a region prone to stable natural dams, yet there remains insufficient understanding of their stability. This paper established an inventory of stable natural dams on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and clarified the reasons for the long-term stability of natural dams of different origins types from the perspective of dam structure. The following conclusions can be drawn.

(1) A total of 348 stable natural dams were identified in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, which could be classified into two types: current (294) and paleo (54) stable natural dams. The spatial distribution of stable natural dams exhibits a pronounced non-uniformity across different basins. The Yalung Zangbo River (89, 25.6%) contained more stable natural dams than other basins.

(2) The origins of stable natural dams included rock avalanches (36.5%), rock slides (7.7%) rock falls (23%), and moraine (32.8%). The varying origins influenced the internal structure of the dam, while the dam structures formed by rock avalanches, rock slides, rock falls, and moraine included inverse grading, pseudo-bedrock, giant-grained, and soil-stone in sequence.

(3) Six geomorphometric classifications for the stable natural dams in the study area were proposed (i.e., type Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, Ⅳ, Ⅴ, and Ⅵ). The morphological parameters of natural dams include dam volume, catchment area, dam height, and dam height. As dam volume and catchment area increased, the number of stable natural dams decreased. Conversely, the number of natural dams first increased and then decreased with increasing dam width and height.

(4) The internal structural characteristics play a crucial role in the stability of natural dams. For dams formed by rock avalanches, huge boulders exhibit a strong anti-erosion capability that can protect the underlying fine particle layer and mitigate the river erosion. The steep-pool system developed in the spillway also significantly dissipates the energy of the river. For dams formed by rock slides, the pseudo-bedrock structure provides resistance to river erosion comparable to that of bedrock. For dams formed by rock falls, the giant-grained structure dam, which is entirely composed of huge boulders, effectively dissipates the energy of the river and reduces the risk of seepage damage. For moraine dams, the boulders left in the spillway offer considerable resistance to river erosion.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, J. & Li, H. Genetic mechanism and disasters features of complicated structural rock mass along the rapidly uplift section at the upstream of Jinsha river. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed. 46, 1153–1167 (2016).

Zhan, J. W. et al. Mass movements along a rapidly uplifting river valley: an example from the upper Jinsha River, Southeast margin of the Tibetan plateau. Environ. Earth Sci. 77, 1–18 (2018).

Dai, F. C., Chack, F., Lee, J. H., Deng & Tham, L. G. The 1786 earthquake-triggered landslide dam and subsequent dam-break flood on the Dadu River, southwestern China’ Geomorphology, 65, 205 –221. (2005).

Zhao, B. et al. The Mogangling giant landslide triggered by the 1786 Moxi M 7.75 earthquake, China. Nat. Hazards. 106, 459–485 (2021).

Dai, L. X., Fan, X. M., John, D., Jansen & Xu, Q. Landslides and fluvial response to landsliding induced by the 1933 Diexi earthquake, Minjiang River, Eastern Tibetan plateau. Landslides 18, 3011–3025 (2021).

Song, L. et al. Insights into the long-term stability of landslide dams on the Eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau, China–A case study of the Diexi area. J. Mt. Sci. 20, 1674–1694 (2023).

Chen, X. Q., Peng, C., Yong, L. & Wan, Y. Z. Emergency response to the Tangjiashan landslide-dammed lake resulting from the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake, China, Landslides, 8, 91–98. (2011).

Cui, P., Chao Dan, Zhuang, J. Q., Yong You, Chen, X. Q. & Kevin, M. S. Landslide-dammed lake at Tangjiashan, Sichuan province, China (triggered by the Wenchuan Earthquake, May 12, 2008): risk assessment, mitigation strategy, and lessons learned. Environ. Earth Sci. 65, 1055–1065 (2012).

Yin, Y. P., FW & Sun, P. Landslide hazards triggered by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, Sichuan, China, Landslides, 6, 139 – 152. (2009).

Costa, J. E. & Robert, L. S. The formation and failure of natural dams. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 100, 1054–1068 (1988).

Korup & Oliver Recent research on landslide dams - a literature review with special attention to new Zealand. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 26 (2), 206–235 (2002).

Peng, M. & Zhang, L. M. Breaching parameters of landslide dams, Landslides, 9, 13–31. (2012).

Weidinger, J. T. ‘Stability and life span of landslide dams in the Himalayas (India, Nepal) and the Qin Ling Mountains (China).’ in, Natural and artificial rockslide dams (Springer). (2010).

Wang, Z. Y., Cui, P., Yu, G. A. & Zhang, K. Stability of landslide dams and development of knickpoints. Environ. Earth Sci. 65, 1067–1080 (2012).

Cui, Y. L., Deng, J. H. & Xu, C. Volume estimation and stage division of the Mahu landslide in Sichuan Province, China, Nat. Hazards, 93, 941–955. (2018).

Wang, Y. S. & Lu, Y. The colluvial landslide accumulation and its environmental effects in Huanglang, Leibo. J. Mt. Sci. 18, 44–47 (2000).

Fan, X. M. Understanding the causes and effects of earthquake-induced landslide dams. (2013).

Fan, X. M., Cees, J., van Westen, Xu, Q., Tolga Gorum & Dai, F. C. Analysis of landslide dams induced by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. J. Asian Earth Sci. 57, 25–37 (2012).

Zhang, Z. et al. Source characteristics and dynamics of the October 2018 Baige landslide revealed by broadband seismograms, Landslides, 16, 777–785. (2019).

Tian, S. F. et al. New insights into the occurrence of the Baige landslide along the Jinsha river in Tibet. Landslides 17, 1207–1216 (2020).

Zhang, Y. G. et al. Application of an enhanced BP neural network model with water cycle algorithm on landslide prediction. Stoch. Env. Res. Risk Assess. 35, 1273–1291 (2021).

Song, L. et al. Distribution and Stabilization Mechanisms of Stable Landslide Dams, Sustainability, 16, 3646. (2024).

Li, H. & Zhang, Y. Analysis of the controlling factors of landslide damming and dam failure: an analysis based on literature review and the study on the meridional river system of Eastern of Tibetan plateau. Quaternary Sci. 35 (1), 71–87 (2015). (In Chinese).

Rouhi, J., Delchiaro, M., Della Seta, M. & Martino, S. New insights on the emplacement kinematics of the Seymareh landslide (Zagros Mts., Iran) through a novel Spatial statistical approach. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 869391 (2022).

Rouhi, J., Delchiaro, M., Della Seta, M. & Martino, S. Emplacement Kinematics of the Seymareh rock-avalanche Debris (Iran) Inferred by Field and Remote Surveying (Italian Journal of Engineering Geology and Environment, 2019).

Wang, L. S., Wang, X. Q. & Xu, X. N. Significances of studying the Diexi paleo-dammed lake at the upstream of Mingjiang River, Sichuan, China. Quaternary Sci. 32 (5), 998–1010 (2012). (In Chinese).

Wang, Z., Cui, P. & Liu, H. Management of quake lakes and triggered mass movements in Wenchuan earthquake. SHUILIXUEBAO, 41 (7). (2010). (In Chinese).

Korup, Oliver, D. R. David R Montgomery & Kenneth Hewitt. Glacier and landslide feedbacks to topographic relief in the Himalayan syntaxes, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 5317-5322. (2010).

Ouimet, W. B., Kelin, X., Whipple, Leigh, H., Royden, Z. & Sun,. The influence of large landslides on river incision in a transient landscape: Eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau (Sichuan, China). Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 119, 1462–1476 (2007).

Zhao, B., Su, L. J., Wang, Y. S., Li, W. L. & Wang, L. J. Insights into some large-scale landslides in southeastern margin of Qinghai-Tibet plateau. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 15, 1960–1985 (2023).

Densmore, Alexander, L., Yong Li, M. A., Ellis & Rongjun Zhou Active tectonics and erosional unloading at the Eastern margin of the Tibetan plateau. J. Mt. Sci. 2, 146–154 (2005).

Zhao, B. & Su, L. J. Complex Spatial and Size Distributions of Landslides in the Yarlung Tsangpo River (YTR) Basin (Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, 2024).

Li, Y. L. et al. Propagation of the deformation and growth of the Tibetan–Himalayan orogen: A review. Earth Sci. Rev. 143, 36–61 (2015).

Yin, A. & Mark Harrison, T. Geologic evolution of the Himalayan-Tibetan orogen, Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 28, 211–280. (2000).

Deng, Q. D., Chen, S. P., Ma, J. & Du, P. Seismic activities and earthquake potential in the Tibetan plateau. Chin. J. Geophys. 57, 678–697 (2014).

Gb18306. ‘China Seismic Ground Motion Parameter Zonation Map of China’, Seismological Bureau, China (2015). (2015).

Ermini, L. & Nicola Casagli Prediction of the behaviour of landslide dams using a Geomorphological dimensionless index. Earth Surf. Processes Landforms: J. Br. Geomorphological Res. Group. 28, 31–47 (2003).

Stefanelli, C., Tacconi, S., Segoni, N., Casagli & Filippo Catani. Geomorphic indexing of landslide dams evolution, Engineering Geology, 208, 1–10. (2016).

Fan, X. M. et al. Stuart Dunning, and Lucia Capra. 2020. ‘The formation and impact of landslide dams–State of the art’. Earth Sci. Rev., 203: 103116 .

Korup, O. Geomorphometric Characteristics of New Zealand Landslide Dams (Engineering Geology, 2004).

Pekel, J. F., Cottam, A., Gorelick, N. & Alan, S. B. High-resolution mapping of global surface water and its long-term changes. Nature 540, 418–422 (2016).

Cui, Y. L., Yang, W. H., Xu, C. & Wu, S. Distribution of ancient landslides and landslide hazard assessment in the Western Himalayan syntaxis area. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1135018 (2023).

Cui, Y. L. et al. ‘Spatial distribution law of landslides and landslide susceptibility assessment in the Eastern Himalayan Syntaxis Region’. Q. J. Eng. Geol.Hydrogeol. qjegh2023–qjegh2144. (2024).

Varnes, D. C. D. and CM David. ‘Landslides: investigation and mitigation Chap. 3-landslide types and processes’. Transp. Res. Board. Special Rep., 247. (1996).

Hungr, O. & Leroueil, S. and Luciano Picarelli. The Varnes classification of landslide types, an update, Landslides, 11, 167 – 194. (2014).

Casagli, N. & Leonardo Ermini Geomorphic analysis of landslide dams in the Northern apennine. Transactions-Japanese Geomorphological Union. 20, 219–249 (1999).

Cruden, D. M., Keegan, T. R. & Thomson, S. The landslide dam on the saddle river near Rycroft, Alberta. Can. Geotech. J. 30, 1003–1015 (1993).

Canuti, P., Casagli, N. & Ermini, L. ‘Inventory and analysis of landslide dams in the Northern Apennine as a model for induced flood hazard forecasting.’ in, Managing Hydro-geological Disasters in a Vulnerable Environment (CNR-GNDCI & UNESCO International Hydrological Programme). (1998).

Wang, Z. Y., Melching, C. S., Duan, X. & Guo-an, Y. Ecological and hydraulic studies of step-pool systems. J. Hydraul. Eng. 135, 705–717 (2009).

Xu, J. & Wang, Z. Y. Formation and mechanism of step-pool system. SHUILIXUEBAO 35 (10), 0048–0055 (2004).

Lenzi, M. A. Stream bed stabilization using boulder check dams that mimic step-pool morphology features in Northern Italy, Geomorphology, 45, 243 –260. (2002).

Wang, Z. Y., Melching, C. S., Duan, X. H. & Yu, G. A. Ecological and hydraulic studies of step-pool systems. J. Hydraul. Eng. 135 (9), 705–717 (2009). (In Chinese).

Yan, L., Lu, Y. J. & Yee-meng, C. Incipient motion of cohesionless sediments on riverbanks with ground water injection. Int. J. Sedim. Res. 27, 111–119 (2012).

Acknowledgements

S.L. discloses support for the research of this work from the Key Laboratory of Xinjiang Coal Resources Green Mining, Ministry of Education, Xinjiang Institute of Engineering, Urumqi 830023, China (Grant No. KLXGY-Z2513), Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region “Tianchi Talent” Introduction Program (Grant No. 2025XGYTCYC07), Doctoral Research Initiation Fund of Xinjiang Institute of Engineering (Grant No. 2025XGYBQJ08) and the Third Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Program (Grant No. 2022xjkk1305). M.L.Q. discloses support for the research of this work from the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52464015). C. Z. G. discloses support for the research of this work from Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Xinjiang (Grant No. XJEDU2024J126).

Funding

This research is supported by the the Key Laboratory of Xinjiang Coal Resources Green Mining, Ministry of Education, Xinjiang Institute of Engineering, Urumqi 830023, China (Grant No. KLXGY-Z2513); Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52464015); Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Xinjiang (Grant No. XJEDU2024J126); Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region “Tianchi Talent” Introduction Program (Grant No. 2025XGYTCYC07); and Doctoral Research Initiation Fund of Xinjiang Institute of Engineering (Grant No. 2025XGYBQJ08); the Third Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Program (Grant No. 2022xjkk1305).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. conducted the field investigation, drafted the manuscript, and provided funding; M.L.Q. contributed to funding and provided critical feedback on the paper; C.Z.G. supported the study financially and offered revisions to the manuscript; W.Y.S. designed the field research and reviewed the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, L., Ma, L., Chang, Z. et al. Distribution patterns and formation mechanisms of stable landslide dams in the Qinghai-Tibet plateau: a preliminary study. Sci Rep 16, 5399 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33618-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33618-y