Abstract

The Glucan Synthase-like 5 (GSL05) gene in potato is homologous to the Arabidopsis GSL05 that has a role in defense-related callose deposition. The role of GSL05-mediated callose deposition in potato roots during root-knot nematode Meloidogyne hapla infection was investigated. Silencing GSL05 in potato resulted in reduced elicitor-induced callose deposition in roots. When StGSL05 knockdown plants were inoculated with nematodes, more second-stage juveniles (J2s) successfully penetrated the roots and formed galls, suggesting a weakened callose-based physical barrier against nematode invasion and supporting the hypothesis that StGSL05 contributes to basal defense. Despite the increased nematode penetration and gall formation, the StGSL05 knockdown plants did not exhibit more egg masses or total number of eggs. This suggested that while more nematodes penetrated, fewer progressed to reproductive maturity. Microscopic analysis revealed morphologically different feeding sites in the knockdown plants, indicating that disrupted callose deposition may impair feeding cell function, which is critical for nematode parasitism. These findings underscore the dual role of callose: while it provides early defense against nematode invasion, its disruption can also interfere with the feeding cell morphology. It highlights a nuanced role for callose in early defense and its potential for enhancing crop resistance to root-knot nematodes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Root-knot nematodes (RKNs) are plant parasitic nematodes that cause $100 billion in worldwide crop losses annually1. The temperate RKN Meloidogyne hapla is an important pest on potato2. Meloidogyne hapla infections reduce the number of tubers, and they can also cause a bumpy appearance to the tuber flesh, significantly reducing its market value3. The infections of below-ground plant tissue start when nematode eggs hatch in the soil as J2s. The J2s invade the roots and establish their feeding sites called giant cells, which occur inside hyperplastically swollen root galls. The feeding site typically contains 6–10 giant cells, which exhibit extreme hypertrophy. Their cell walls become thickened, and they have increased numbers of cell wall ingrowths that enhance the cell wall surface area for short distance transport of water and solutes. These cell wall ingrowths are formed at giant cell walls facing xylem vessels4,5. Because giant cells are the sole source of food for RKNs, the failure to establish functional and efficient giant cells means that the RKNs will die, or will be impeded in development, or their fecundity will be significantly hindered due to the lack of sufficient amount of nutrients. As a result, giant cells are an Achilles heel for RKNs; altering the formation of the giant cells could reduce nematode infestations6. Considering that there is no genetic resistance to RKNs in commercially available potato cultivars in the United States, exploring giant cell formation offers an avenue towards engineering RKN resistance in potato.

During plant infection, the RKNs secrete molecules called effectors that help the nematodes bypass plant defenses and establish successful feeding sites7. Previous work in Arabidopsis indicates that some effectors can suppress the host basal immune responses. These basal host defenses, also known as Pathogen Associated Molecular Pattern (PAMP)-triggered immunity (PTI), are elicited by conserved pathogen molecules (i.e., the PAMPs), such as the RKN secreted ascaroside #18 8. Ascaroside #18 and other nematode related PAMPs trigger a cascade of defense responses that include an accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), the deposition of callose near the infection site, and activation of defense gene expression9. Interestingly, ectopic expression of the M. hapla effector Mh265 caused the plants to become more susceptible to nematode infection and suppressed elicitor-induced callose deposition10. The result suggested that the callose deposition response during PTI may have a significant role in plant-nematode interactions.

Callose is a β-(1,3)-D-glucan with roles in growth, development and defense11. During pathogen attack, callose is deposited between the plasma membrane and cell wall. The callose synthase gene in Arabidopsis that has a primary role in pathogen-induced callose deposition is called glucan-synthase like 5 [AtGSL05, also known as POWDERY MILDEW RESISTANT 4 (PMR4) callose synthase]12,13. Callose deposits can help strengthen the cell wall at the sites of infection or damage, thereby enhancing the plant’s defense mechanisms13,14. Loss-of-function Arabidopsis mutants of GSL05 are unable to synthesize callose at the sites of pathogen invasion; the lack of callose compromises the plant’s response to pathogen attack. However, the gsl05 mutant exhibits increased resistance to the powdery mildew pathogen Erysiphe cichoracearum, which is attributed to the accumulation of salicylic acid (SA)13. StGSL05 is also known as Powdery mildew resistant 4 (StPMR4) and Callose synthase 12 (StCalS12). Interestingly, a knockout in the potato homolog of GSL05 resulted in enhanced resistance to foliar pathogen, Phytophthora infestans, suggesting that this potato gene is involved in pathogen susceptibility15.

Given that M. hapla secretes at least one effector that inhibits PAMP-induced callose deposition and considering the significant threat this nematode poses to potato crops, we aimed to explore the relationship between callose deposition and nematode parasitism.

Results

Inhibiting Callose synthase activity enhanced nematode galling

Previous work with the effector Mh265 indicated that the nematodes are suppressing callose deposition to facilitate infections10. Because the callose synthase inhibitor 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DDG) was previously shown to suppress callose deposition in potato16, we used 2-DGG to block callose synthase activity and draw a link between callose deposition and nematode infection in potatoes. After watering the four-week-old potato plants with a solution of 1 mM 2-DDG each day for four days, the plants were inoculated with freshly hatched M. hapla J2s. At 21 days post inoculation (dpi), the 2-DDG treated potatoes showed no significant differences in fresh shoot weights as compared to the control (Fig. 1A) and a slight increase in fresh root weight (Fig. 1B). There were on average twice the number of galls per plant (Figure S1) and galls per gram root tissue in the 2-DDG treated plants compared to the control (Fig. 1C). The 2-DDG solution had no effects on J2 viability (Figure S2), indicating that the effects of 2-DDG were specifically on the plant roots.

Chemical inhibition of callose synthases enhances roots galling. Three-week-old cv. Desiree potato plants were watered with 1 mM 2-DDG or water for four days and then inoculated with M. hapla J2s. Fresh root and shoot weights as well as root galling were assessed at 21 dpi. (A) Average fresh shoot weight. (B) Average fresh root weight. (C) Average number of galls per g of fresh root. Data represents > 10 replicates. Experiment repeated twice with similar results. Bars represent mean +/- standard deviation (SD) (Mann-Whitney U test; ns, non-significant, **p-value ≤ 0.005).

Silencing StGSL05 results in reduced Callose deposits in potato roots

Because AtGSL05 is the major Arabidopsis callose synthase involved in PAMP-induced callose deposition12,13, we focused on its previously identified homolog in potato StGSL05 (Sotub07g019600). The StGSL05 gene is 5.3 kb long with no introns, and the encoded protein has 74.2% amino acid identity to AtGSL05. Previous work in Arabidopsis showed that the bacterial flagellin peptide Flg22 can enhance the expression of AtGSL05, which is followed by increased callose accumulation17. To test if a bacterial elicitor can induce StGLS05 expression in potato, FlgII-28 was used to trigger PTI. FlgII-28 is a stronger defense elicitor in potato compared to Flg2218. Potato leaves and roots infiltrated with FlgII-28 showed enhanced callose deposition (Fig. 2 and Figure S3).

Characterization of the StGSL05 knockdown plants. (A) Plants from two independent lines (RNAi: GSL05-1 and RNAi: GSL05-2) exhibited lower basal StGSL05 expression levels in the roots compared to the untransformed wildtype potato cv Desiree (WT). Data represents mean relative transcript abundance from 8–10 biological replicates +/- SD (Welch’s t test; *p-value ≤ 0.05, **p-value ≤ 0.01). (B) Representative photos of Aniline Blue stained roots of wildtype and StGSL05 knockdown lines showing a decrease in the FlgII-28-induced callose deposition. Scale bars = 100 μm. Experiment was repeated twice with similar results. (C) Quantification of callose deposits in the roots of wildtype and StGSL05 knockdown lines. N = 25–42. Experiment repeated twice with similar results.

To study the effects of knocking down StGSL05 in potato, two RNAi silencing lines (RNAi: GSL05-1 and RNAi: GSL05-2) were generated using the RKN-susceptible potato cv. Desiree. The two lines are independent transformants of cv. Desiree plants that express a RNAi construct designed to target and silence StGSL5. The baseline expression levels of StGSL05 in the roots of both knockdown lines were lower than in those of the wild-type cv. Desiree plants (Fig. 2A). StGSL3, StGSL4, and StGSL10 were also expressed in roots, but there was no difference in expression in these genes in the StGSL5 knockdown lines compared to the control (Figure S4). In comparison to cv. Desiree plants, the RNAi: StGSL05-1 plants and the RNAi: StGSL05-2 plants showed a 21-fold and 11-fold reduction in the number of callose deposits, respectively, in the roots in response to a FlgII-28 treatment (Fig. 2B and C). Altogether, the data show that the StGSL05 knockdown plants are reduced in GSL05 expression and elicitor-induced callose deposition. Interestingly, the plants of both RNAi lines were significantly smaller than the control cv Desiree plants (Figure S5). This finding is consistent with previously published reports in potato19, tomato20,21, and Arabidopsis22 in which silencing or knocking down GSL05 leads to smaller plants.

Silencing StGSL05 impacts overall nematode susceptibility

To determine if callose deposition plays an essential role in nematode penetration and gall formation, we infected the StGSL05 knockdown plants (RNAi: GSL05-1 and RNAi: GSL05-2) and the wild-type potato with M. hapla J2s. To consider the possibility that smaller root systems in StGSL05 knockdown plants provide fewer penetration sites for M. hapla, we normalized our infection data relative to fresh root weights. At 7 dpi, the nematodes invaded the roots indicating successful root penetration, but galls were not fully formed yet. In the roots of the RNAi lines, there were approximately 3-fold more J2s per root (Figure S6) and per gram of root tissue, compared to the control (Fig. 3A). At 14 dpi, the root galls become clearly visible. In the StGSL05 knockdown plants (RNAi: GSL05-1 and RNAi: GSL05-2), there were approximately 4 and 9-fold more galls, respectively, in the two silenced lines, and thus, significantly more galls in total (Figure S6) and galls per gram of root compared to the control (Fig. 3B).

The StGSL05 knockdown plants have more initial infections, but not all the initial infections lead to egg masses (A) Nematode penetration was measured in cv. Desiree potato (WT) and knockdown plants RNAi: GSL05-1 and RNAi: GSL05-2. Graph shows mean number of J2s per gram of fresh root tissue +/-SD at 7 dpi (Mann-Whitney U test, ****p-value ≤ 0.0001). (B) Mean number of galls per gram of fresh root tissue at 14 dpi +/-SD (Mann-Whitney U test, ****p-value ≤ 0.0001). (C) Mean number of egg masses per gram of fresh root tissue at 25 dpi +/-SD. (D) Mean number of total eggs per gram of fresh root tissue at 30 dpi +/-SD. Data represents > 10 replicates each; all assays were repeated twice.

Since both the silenced lines showed significantly more galls as compared to the control, we hypothesized that the plants would also have more egg masses and total eggs per gram of root. In the wildtype potato, the females of M. hapla have completed their lifecycle and have generated egg masses at 25 dpi. Thus, the number of egg masses per gram of root was assessed at 25 dpi. In addition, eggs were extracted from both the wildtype and StGSL05 knockdown plants and total number of eggs were counted at 30 dpi, a timepoint when egg masses were filled with eggs. There was no significant difference in the number of egg masses or the total numbers of eggs per plant (Figure S7) and per gram of root between RNAi: GSL05-1 and RNAi: GSL05-2 and the control (Fig. 3C and D). The data suggest that although more J2s could initially penetrate the roots and establish root galls, not all of them were able to develop into egg-laying females.

Silencing of StGSL05 impacts giant cell structure

The data suggest that more J2s initially invade the roots of RNAi: GSL05 plants in comparison to the wild-type control, but only some of them were able to develop into egg-laying females (Fig. 3). Thus, we hypothesized that the giant cells induced in the roots of GSL05-silenced plants could develop abnormally, which prevented the juveniles from completing their life cycle into mature females. To investigate this issue, the galls were collected at 14 dpi and processed for serial semi-thin sectioning for microscopic examinations. At the regions next to the nematodes’ heads, the widest diameters of giant cells were measured (as shown by red lines on Fig. 4A-C). The average diameters of giant cells induced in the GSL05-silencing lines were significantly smaller as compared to those of the giant cells induced in the wild-type roots (Fig. 4D and Figure S8).

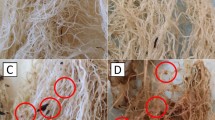

Light microscopy images of cross sections of giant cells induced in roots of control cv. Desiree (A), RNAi: StGSL05-1 (B), and RNAi: StGSL05-2 (C) lines. Red lines depict examples of randomly measured widest diameters of giant cells. Asterisks indicate giant cells and arrows point to nuclei. Three-week-old potato plants were inoculated with M. hapla J2s. Galls were collected on 14 dpi and after embedding in resin and sectioning stained with Toluidine Blue. (D) Statistical comparison of the widest diameters of giant cells induced in control and RNAi-silenced plants. N = 10 (t-test, error bars represent +/-SD, *p-value ≤ 0.01). Abbreviations: N: nematode; Ph: phloem; X: xylem. Scale bars = 20 μm.

Comparisons of serial sections indicated that in all genotypes the feeding sites were composed of 4–6 giant cells surrounding the anterior part of the nematode body (Fig. 4A-C). Giant cells were located in the vascular cylinder with direct contact to proliferating secondary phloem and xylem elements. Each giant cell seemed to contain only one extremely strongly hypertrophied and strongly amoeboid nucleus with several nucleoli and tend to localize close to the nematode’s head region. The stainability of nucleoplasm in giant cells induced in cv. Desiree and silenced line RNAi: GSL05-1 was similar. However, in some giant cells induced in line RNAi: GSL05-2, the nucleus seemed to be collapsed and formed elongated protrusion with the nucleoplasm strongly stained with Toluidine Blue (Fig. 4A and B, versus C). Similarly, the cytoplasm of giant cells induced in wild type plants contained numerous very small vacuoles (Figs. 4A and 5A) in regions remote from the nucleus. The vacuoles were larger in giant cells induced in silenced line RNAi: GSL05-1 plants, but the appearance of the cytoplasm was not structurally changed (Figs. 4B and 5B). In contrast the giant cells induced in RNAi: GSL05-2 plants, the cytoplasm was frequently collapsed and retracted from the cell walls. They also contained numerous large vacuoles of irregular shapes (Figs. 4C and 5C).

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of 14 dpi giant cells induced in roots of wild type cv. Desiree (A, D, G, J, and M), and RNAi: GSL05-1 (B, E, H, K, and N) and RNAi: GSL05-2 (C, F, I, L, and O) plants infected with M. hapla. (A–C) Overview of giant cell cytoplasm with nucleus and nucleoli. (D–F) Ultrastructural details of nucleus and neighboring cytoplasm. Asterisks indicate heterochromatin clumps. (G–I) Plasmodesmata (arrows) in the outer cell wall of giant cells facing sieve tube members. (J–L) Plasmodesmata (arrows) in thin parts of cell wall between giant cells. (M–O) Plasmodesmata (arrows) between sieve tube members and companion cells, and sieve pores (arrow heads) in sieve plates between sieve tube members. CC: companion cell; CW: cell wall; GC: giant cell; M: mitochondrion; No: nucleolus; Nu: nucleus; Pl: plastid; SE: sieve tube member; V: vacuole. Scale bars = 5 μm (A–C), and 2 μm (D–O).

The ultrastructural organization of protoplasts was similar in giant cells induced in wild-type cv. Desiree and RNAi: GSL05-1 plants (Fig. 5A, D, and B, E). The cytoplasm was uniformly electron dense and two distinct regions in giant cell protoplast could be discriminated. The cytoplasm adjacent to the nucleus contained numerous plastids and mitochondria with only a few vacuoles, whereas the cytoplasm relatively distant from the nuclei contained numerous small vacuoles and much fewer plastids and mitochondria. The ultrastructure of the plastids and mitochondria was similar in both lines (Fig. 5D and E). The plastids frequently contained starch grains. Many of them had constrictions, indicating the process of their division, especially in giant cells induced in the roots of the cv. Desiree control (Fig. 5A and D). Mitochondria were usually round or ring-shaped on cross sections (Fig. 5D and E). The nuclei were strongly hypertrophied and irregular in outlines (Fig. 5A and B). The nucleoplasm was electron dense and contained numerous heterochromatin granules, which appeared more numerously in giant cells induced in wild type plants (Fig. 5A) than in giant cells induced in silenced RNAi: GSL05-1 plants (Fig. 5B). Except for a limited number of plastids containing starch grains and higher numbers of large vacuoles in giant cells induced in RNAi: GSL05-1, no other ultrastructural differences could be recognized in comparison to giant cells induced in wild type cv. Desiree roots. In the case of giant cells induced in RNAi: GSL05-2 roots, three different types of protoplast ultrastructure were observed: (i) the protoplasts were strongly osmiophilic and highly vacuolated with organelles not being recognizable, indicating their degradation (Fig. 5L); (ii) the ultrastructure of some others resembled that of the giant cells induced in RNAi: GSL05-1 roots, with high numbers of large vacuoles but structurally well-preserved cytoplasm and organelles; (iii) the remains contained granular cytoplasm with numerous large vacuoles and few relatively electron translucent plastids and mitochondria that were hard to discriminate in the cytoplasm, indicating that they were apparently about to be degraded (Fig. 5C and F). However, in all types of giant cell protoplast organization, the nuclei were shrunk and collapsed (Fig. 5C and F). They contained large regions of uniformly electron transparent nucleoplasm, large heterochromatin clumps instead of dispersed small heterochromatin grains, and small nucleoli. These features indicate degradation or at least decreased effectiveness of giant cells induced in RNAi: GSL05-2 roots.

On the basis of microscopic examination, it becomes apparent that the lower number of egg-lying females on the roots of both GSL05-silenced plant may be caused by lower effectiveness of induced giant cells, namely higher volume of giant cells occupied by vacuoles and in parallel lower volume of cytoplasm or premature degradation of giant cells in the line RNAi: GSL05-2.

As there is a debate concerning the pathways of nutrients loading into the giant cells (apoplastic vs. symplasmic), we have paid special attention to the analyses of the plasmodesmata structure and localization in giant cells induced in RNAi-silenced GSL05 plants. In all three genotypes, there were only a few plasmodesmata found in the outer cell walls of giant cells at the regions facing sieve tubes (Fig. 5G-I). They were apparently opened and not occluded by callose depositions in all three genotypes. In other regions, facing to the xylem vessels or parenchymatic cells, the outer giant cell walls were strongly thickened and covered by extensive systems of cell wall ingrowths. Numerous plasmodesmata were present on the thin parts of cell walls between neighboring giant cells (Fig. 5J-L). They remained always open and were not covered by callose depositions even in walls between giant cells induced in roots of the RNAi: GSL05-2 plants containing degraded cytoplasm (Fig. 5L). Callose was also deposited on sieve pores present in sieve plates between the sieve tube members that are the main long-distance transport pathway of nutrients in the phloem. Also in this case, there was no difference in the abundance of callose deposits on sieve pores and plasmodesmata between sieve tubes and their companion cells in the phloem elements differentiated around giant cells induced in the roots of cv. Desiree and both RNAi: GSL05-silenced plants (Fig. 5M-O).

Discussion

Recent studies suggest that GSL05 functions as a susceptibility gene in several plant-pathogen interactions19,20,23. As a result, GSL05 has been suggested as a good target for manipulation, either by gene editing or gene knockdown to develop foliar pathogen resistance in different crops. Here we have investigated the link between callose deposition by GSL05 in potato and M. hapla infections to determine if StGSL05 is a susceptibility gene for nematodes.

Although nematodes are among the most economically significant plant pathogens, affecting a wide range of crops and causing substantial yield losses worldwide, there are only a few studies investigating the role of callose deposition in host-nematode interactions. Previously, callose deposition during beet cyst nematode feeding site development was studied in Arabidopsis24, but the effects of the gsl05 mutant on M. incognita development was not tested. In Arabidopsis, M. incognita did not induce callose deposition in the giant cells or along the plasmodesmata connecting giant cells24. The lack of significant callose deposition in the feeding cells suggests that M. incognita, and RKNs in general, may have evolved mechanisms to bypass or suppress callose-mediated defense24. In line with this argument, several effectors from different species of RKNs (e.g., Mo237, Mh265, MgGPP, MiCE108, Msp40 and MiCRT) suppress defense-related callose deposition responses, indicating that suppressing callose would be important for the RKNs to make successful infections10,25,26,27,28,29,30.

Our genetic and chemical approaches to manipulate callose deposition indicated that the nematodes could more easily penetrate the potato roots, resulting in more nematodes inside the roots early after plant inoculation. The data led to the hypothesis that StGSL05 has a role in basal defense-related callose deposition to control nematode penetration and migration in host roots. Our data show that potatoes knocked down in StGSL05 expression had significantly fewer elicitor induced callose deposits in the roots. This result indicates that, like the situation in Arabidopsis12, the potato GSL05 plays a major role in defense-related callose deposition. The StGSL05 knockdown lines also were smaller than the wildtype control, a phenomenon previously described for the Arabidopsis gsl05 mutant. The reduced size of the Atgsl05 plants has been attributed to constitutively higher SA levels due to GSL05’s role in negatively regulating SA-associated defense pathways12,13. The absence of elevated PR1 expression in untreated RNAi: StGSL05 plants compared to the wild type indicates that the SA signaling pathway is not activated in the potato knockdown lines (Figure S9).

We hypothesized that defense-related callose may help thicken the cell wall, enhancing the physical barrier against RKNs like M. hapla11. Previous work in rice (Oryza sativa cv. ‘Nipponbare’) showed that mutants that exhibited enhanced root callose deposition were more resistant to the rice root-knot nematode M. graminicola, whereas genotypes that had decreased callose deposition levels were more susceptible31. Treating potatoes with 2-DDG prior to nematode inoculation resulted in plants that were more susceptible to infections. 2-DDG is a callose synthase inhibitor and shown to affect callose deposition in a variety of plants (tomato, soybean, barley)32, but we cannot rule out possible pleiotropic effects on the plant make it more susceptible to nematodes. Nevertheless, the data is consistent with the genetic data in which StGSL05 was silenced. Our data on potatoes silenced in StGSL05 showed that more J2s were able to penetrate the roots, suggesting that the roots were more susceptible to nematode penetration and migration.

Interestingly, while more J2s were found in the roots of the RNAi: StGSL05 lines, these plants did not exhibit an increase in the number of egg masses or total eggs per gram of root. Although more juveniles successfully penetrated the roots, not all developed into egg-laying females. This suggests that while root penetration was facilitated in the RNAi: StGSL05 lines, the development of functional feeding sites, which is essential for M. hapla feeding and molting, was likely disrupted. To investigate this further, an ultrastructural examination of the giant cells was performed. The giant cells in silenced lines appeared smaller and contained large vacuoles. The effectiveness of the induced giant cells to provide nutrition to the nematodes may have been compromised in the RNAi: StGSL05 lines.

Giant cell functionality may rely on functional plasmodesmata that enable symplastic transport of solutes either between giant cells or between giant cells and sieve elements24. Callose plays a crucial role in regulating this transport by altering the size exclusion limit of plasmodesmata23. In Arabidopsis, the mutant AtBG_ppap (β-1,3-glucanase putative plasmodesmal-associated protein) showed enhanced callose deposition around plasmodesmata33. Following cyst nematode infection, the mutant displayed significantly reduced syncytium expansion, suggesting that tight regulation of callose deposition in plasmodesmata is essential for proper syncytial development24. In rice, symplasmic connections have been observed between phloem and M. graminicola-induced giant cells34. Increased callose deposition at the plasmodesmata was shown to impair the ability of giant cells to import sucrose from the phloem, thereby reducing giant cell formation34. However, our analysis of callose deposition in the plasmodesmata of giant cells in wild-type cv. Desiree, RNAi: GSL05-1, and RNAi: GSL05-2 plants revealed no significant differences in callose density. This finding indicates that that the observed difference in giant cell morphology is not attributable to callose changes in the plasmodesmata.

Callose also plays an important role in enhancing cell wall flexibility35. In fra mutant plants, which lack callose in their cell walls, giant cells are extremely fragile due to reduced elasticity. Surprisingly, these plants exhibit increased susceptibility to root-knot nematode (M. incognita) infection36. However, the role of callose in this infection phenotype is complex. The fra plants compensate for their lack of cell wall elasticity by increasing the levels of methyl-esterified homogalacturonans and arabinans, which help maintain flexibility in the absence of callose36. While findings from fra plants may not directly clarify callose’s role in giant cell development, we cannot rule out the possibility that callose contributes to giant cell wall elasticity. This remains relevant to understanding the observed morphological defects in the giant cells in our study. Further investigation is needed to clarify the specific role of callose in giant cell structure and function.

Methods

Plant materials

The surface-sterilized internodes of Solanum tuberosum (cv. Desiree) were placed on Murashige and Skoog media with 10% [w/v] sucrose and were incubated in a growth chamber (23 °C, 12 h:12 h light: dark cycle) for 3–4 weeks. Three- to four-week-old plantlets were transferred to cone-tainers (8 in x 1.5 in) filled with sand and incubated in another growth chamber at 23 °C, 14 h:10 h light: dark cycle. Plants were fertilized twice a week with 200 ppm of Pete’s professional fertilizer (20:10:20) (Scous) made with tap water. After three weeks of recovery in the chamber, the plants were used for callose inhibition and nematode infestation assays. Authors complied with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

Nematode assays

Meloidogyne hapla (VW9, provided by V. Williamson, UC Davis) was used in all experiments. To collect nematode eggs, roots from infected tomato (Solanum lycopersicum cv. Rutgers) were agitated in 10% [v/v] commercial bleach (5.25% sodium hypochlorite) for 5 min. The eggs were collected on a 25 μm mesh sieve and surface sterilized by incubating in 10% [v/v] bleach for 5 min followed by three washes with sterile H2O. After the last wash, the eggs were pelleted by a final centrifugation (4,000 rpm for 5 min) and re-suspended in 50 ml water with 1% [w/v] SDS and 2% [w/v] Plant Preservative Mixture (Plant Cell Technology)37.

Potato nematode infection assays were performed in cone-tainers with sand. For the J2 penetration assay, plants were inoculated with 750 freshly hatched J2s and harvested at 7 dpi. Fresh shoot and root weights were recorded, and roots were incubated in 10% [v/v] bleach for 5 min with intermittent swirling. J2s were stained with 0.1% [w/v] Acid Fuchsin and counted under a stereo microscope. For the nematode gall assay, plants were inoculated with 1000 M. hapla eggs and harvested at 14 dpi. In the egg mass assay, plants were inoculated with 1000 M. hapla eggs and roots were harvested after 25 dpi. Roots were stained with 0.05% [w/v] Phloxine B solution for 3–5 min. For the total egg count assay, plants were inoculated with 1000 M. hapla eggs and harvested at 30 dpi when egg masses had fully matured. Eggs were extracted using 10% [v/v] bleach and collected through a 25 μm sieve. The J2, gall, and egg counts were performed using a Zeiss Stereo Discovery V8 microscope. All assays were repeated twice with > 10 replicates per trial. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software.

Callose inhibition assay

Three weeks after plantlets were transferred from tissue culture jars to “cone-tainers” of sand, the plants were drenched for four consecutive days with 20 ml of either 1 mM 2-DDG (2-deoxy D-Glucose) (prepared from 500mM stock dissolved in DMSO) or 0.2% v/v DMSO in water (control). On day five, plants were inoculated with approximately 960–1000 M. hapla J2s and subsequently watered daily with tap water and fertilized twice a week. At 21 dpi, the plants were removed from the cone-tainers, and the sand was washed away from the roots. The roots were weighed, and galls in each root system were counted. The nematode infection assays were repeated twice with > 10 replicates in each trial. For testing nematode viability in 2-DDG, freshly hatched J2s (~ 130) were placed in a 12-well plate in either 1 mM 2-DDG or 0.2% v/v DMSO control solution. Non-moving J2s were considered dead. The number of dead J2s were counted every day for 10 days.

Gene silencing in potato

A 321 bp StGSL05 fragment was amplified from cv. Desiree genomic DNA. The PCR product was cloned into pDONR207 using BP clonase II (ThermoFisher Scientific). The BP reaction was performed using 150 ng pDONR207, 3.5 µl of the attB PCR product using the GSL5 specific primers (Supplemental Table 1) and 1 µl BP Clonase II enzyme mix in 8 µl total water. The reaction was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. 1 µl of the Proteinase K solution was added to each sample and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. The products were introduced into E. coli DH5α competent cells by heat shock. In brief, the cells were thawed on ice for 5 min. Then 1 µl of the BP Clonase II reaction was added to the thawed cells and incubated on ice for 5 min. The cells were placed at 42 °C for 90 s and then quickly placed on ice for 2 min. 500 ml Luria-Bertani (LB) media was added to the cells. The bacteria were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with gentle shaking. Then 100 µl of the bacteria were spread on a LB plate with the appropriate antibiotics for 24 h at 37 °C. Individual colonies were isolated from the plates and grown in 10 ml LB with the appropriate antibiotics. The plasmid was isolated from the E. coli by plasmid isolation kit (Zymo Research), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The StGSL05 fragment was subsequently cloned from pDONR207 into the silencing vector pK7FWIWG2 (II) Red Root using LR clonase II (ThermoFisher Scientific). 150 ng of the entry vector was mixed with 150 ng pK7FWIWG2 (II) Red Root in a total volume of 4 µl. Then 1 µl LR Clonase II was added to the mix and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. 1 µL of the Proteinase K solution was added to each sample and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. The LR reaction was then transformed into E. coli DH5α competent cells by heat shock. The cells were grown overnight at 37 °C. Individual colonies were isolated from the plates and grown in 10 ml LB with the appropriate antibiotics. The plasmid was isolated from the E. coli by plasmid isolation kit (Zymo Research), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The construct was then transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404 (Goldbio) by heat shock. Four-week-old Desiree potato internodal pieces were transformed following the previously described potato transformation protocol of Chronis et al., 2014 38. Transformants were confirmed by PCR amplification of the StGSL05 insert.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from potato roots (cv. Desiree) using the Mini Plant RNA isolation kit (Zymogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA (~ 5 µg) was treated with DNase I (1 U/µl, Thermo Scientific) and DNA-free RNA was used as a template for cDNA synthesis using Oligo(dT)13 in a reaction with Reverse Transcriptase (Protoscript II; 200 U/µl, New England Biolabs) in a total volume of 20 µl. The cDNA was diluted 1:10 with H2O and qRT-PCR was performed with GSL05 primer pair19. qRT-PCRs were prepared using 1X PowerTrack SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 0.5 µl of 10 µM primers, 2 µl of diluted cDNA and PCR-grade water to a final volume of 10 µl. After an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 90 s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 56 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 40 s were ran on a CFX96 detection system (Biorad). Using the Ct values, qRT-PCR data was analyzed according to the 2–ΔΔCT method39. Each reaction was performed in triplicate and the results represent the mean of at least six independent biological replicates. Transcript levels were normalized for each sample with the gene ELF-1α, which has been previously identified as a stable housekeeping gene40. Primers are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Callose staining in potato roots

For callose staining in potato roots, three-week-old tissue culture plants were soaked in 1 mM aqueous solution of FlgII-28 or in water (as the control) for 48 h and roots were collected for callose staining. For staining, roots were incubated overnight in ethanol: acetic acid (v/v; 3:1) solution at room temperature. The roots were then rehydrated with 70% [v/v] and 50% [v/v] ethanol incubations for 2-h each, followed by an overnight incubation in water. The roots were first washed three times with water, followed by a 1h incubation at 37 °C in a 10% [w/v] NaOH solution. Afterward, the roots were again washed four times with water (5 min each), followed by 30 min incubation in 150 mM phosphate buffer. Callose deposits were stained with a 1% [w/v] Aniline Blue solution (prepared in 67 mM phosphate buffer) for 1 h. Callose deposits were observed using a Leica DMI3000B microscope (Leica Microsystems) with a DAPI filter Images were captured using a Leica DFC450C camera (Leica Microsystems). The roots were digitally photographed, and callose deposition in the photographed areas was quantified with ImageJ41,42. In brief, images were opened in ImageJ as 8-bit grayscale (B&W) JPEG files. A threshold value of ≥ 40 was applied to highlight callose deposits, which appeared as green fluorescent signals. To quantify the callose, the Analyze Particles function was used to count the number of fluorescent deposits. Statistical analyses and graphical representations were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software.

Nematode gall microscopy

For microscopy, 3-week-old wildtype and RNAi: GSL05-1 and RNAi: GSL05-2 plants grown in sand cone-tainers were inoculated with 1000 M. hapla J2s. Root tissue was collected at 14 dpi. After gently washing the roots in tap water, galls were dissected and collected under a stereo microscope. Collected galls were fixed overnight at 4 °C in 2% [w/v] paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer43 and rinsed three times in 0.1 M phosphate buffer the following day. Galls were then postfixed overnight at 4 °C in 1% Osmium tetroxide(diluted in 1 N phosphate buffer)44, followed by three washes with distilled water. Subsequently, galls were dehydrated through a series of ethanol washes (30%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90% [v/v], and two washes in 100% absolute ethanol for 10 min each). The dehydrated galls were then washed twice in propylene oxide (10 min each) and infiltrated with Spurr’s low viscosity epoxy resin45. Samples were incubated overnight at room temperature in a series of epoxy resin: propylene oxide mixtures (1:2, 1:1, 2:1 [v/v]), followed by three overnight incubations in pure Spurr’s resin. The resin blocks were polymerized at 70 °C overnight. Samples were sectioned using a Leica RM2165 microtome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and stained with 1% [w/v] Toluidine Blue dissolved in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.9). Stained sections were examined using an Olympus AX70 “Provis” light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an Olympus DP90 digital camera.

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), ultra-thin sections were obtained from selected regions of galls using a Leica Ultracut E ultramicrotome. The sections were counterstained with saturated solutions of uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined under an FEI 268D “Morgagni” (FEI Corp., Hillsboro, USA) transmission electron microscope equipped with an SIS-Olympus “Morada” (Olympus) digital camera. The obtained images were cropped, resized, and adjusted for brightness and contrast using Adobe Photoshop software.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Nicol, J. et al. Genomics and molecular genetics of plant-nematode interactions in Current Nematode Threats To World Agriculture (eds Jones, J., Gheysen, G. & Fenoll) C) 21–43 (Springer, (2011).

Gorny, A. M., Hay, F. S. & Pethybridge, S. J. Response of potato cultivars to the Northern root-knot nematode, meloidogyne hapla, under field conditions in new York State, USA. Nematology 23, 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685411-bja10050 (2020).

Vovlas, N., Mifsud, D., Landa, B. B. & Castillo, P. Pathogenicity of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne Javanica on potato. Plant. Pathol. 54, 657–664. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3059.2005.01244.x (2005).

Escobar, C., Barcala, M., Cabrera, J. & Fenoll, C. Chapter One - Overview of Root-Knot Nematodes and Giant Cells in Advances in Botanical Research Vol. 73 (eds Escobar, C. & Fenoll, C.) 1–32Academic Press, (2015).

Wieczorek, K. in Advances in Botanical Research Vol. 73 (eds Carolina Escobar & Carmen Fenoll) 61–90Academic Press, (2015).

Favery, B., Quentin, M., Jaubert-Possamai, S. & Abad, P. Gall-forming root-knot nematodes hijack key plant cellular functions to induce multinucleate and hypertrophied feeding cells. J. Insect Physiol. 84, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2015.07.013 (2016).

Vieira, P. & Gleason, C. Plant-parasitic nematode effectors - insights into their diversity and new tools for their identification. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 50, 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2019.02.007 (2019).

Manosalva, P. et al. Conserved nematode signalling molecules elicit plant defenses and pathogen resistance. Nat. Commun. 6, 7795. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8795 (2015).

Boller, T. & He, S. Y. Innate immunity in plants: an arms race between pattern recognition receptors in plants and effectors in microbial pathogens. Science 324, 742–744. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1171647 (2009).

Gleason, C. et al. Identification of two Meloidogyne hapla genes and an investigation of their roles in the plant-nematode interaction. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 30, 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1094/mpmi-06-16-0107-r (2017).

Li, N. et al. The multifarious role of Callose and Callose synthase in plant development and environment interactions. Front. Plant. Sci. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1183402 (2023).

Jacobs, A. K. et al. An Arabidopsis Callose synthase, GSL5, is required for wound and papillary Callose formation. Plant. Cell. 15, 2503–2513. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.016097 (2003).

Nishimura, M. T. et al. Loss of a Callose synthase results in Salicylic acid-dependent disease resistance. Science 301, 969–972. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1086716 (2003).

Ellinger, D. et al. Elevated early Callose deposition results in complete penetration resistance to powdery mildew in Arabidopsis. Plant. Physiol. 161, 1433–1444. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.112.211011 (2013).

Li, R. et al. CRISPR/Cas9-based knock-out of the PMR4 gene reduces susceptibility to late blight in two tomato cultivars. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314542 (2022).

Chowdhury, R. N. et al. HCPro suppression of Callose deposition contributes to strain-specific resistance against potato virus Y. Phytopathology 110, 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1094/phyto-07-19-0229-fi (2020).

Luna, E. et al. Callose deposition: a multifaceted plant defense response. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 24, 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1094/mpmi-07-10-0149 (2011).

Moroz, N. & Tanaka, K. FlgII-28 is a major flagellin-derived defense elicitor in potato. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 33, 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1094/mpmi-06-19-0164-r (2020).

Sun, K. et al. Silencing of six susceptibility genes results in potato late blight resistance. Transgenic Res. 25, 731–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11248-016-9964-2 (2016).

Huibers, R. P. et al. Powdery mildew resistance in tomato by impairment of SlPMR4 and SlDMR1. PLoS One. 8, e67467. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067467 (2013).

Santillán Martínez, M. I. et al. CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of the tomato susceptibility gene PMR4 for resistance against powdery mildew. BMC Plant. Biol. 20, 284. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-020-02497-y (2020).

Leslie, M. E., Rogers, S. W. & Heese, A. Increased Callose deposition in plants lacking DYNAMIN-RELATED PROTEIN 2B is dependent upon POWDERY MILDEW RESISTANT 4. Plant. Signal. Behav. 11, e1244594. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2016.1244594 (2016).

Liu, J., Zhang, L. & Yan, D. Plasmodesmata-involved battle against pathogens and potential strategies for strengthening hosts. Front. Plant. Scie. 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.644870 (2021).

Hofmann, J., Youssef-Banora, M., de Almeida-Engler, J. & Grundler, F. M. The role of Callose deposition along plasmodesmata in nematode feeding sites. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 23, 549–557. https://doi.org/10.1094/mpmi-23-5-0549 (2010).

Chen, J. et al. A novel Meloidogyne graminicola effector, MgMO237, interacts with multiple host defence-related proteins to manipulate plant basal immunity and promote parasitism. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 19, 1942–1955. https://doi.org/10.1111/mpp.12671 (2018).

Chen, J. et al. A novel Meloidogyne graminicola effector, MgGPP, is secreted into host cells and undergoes glycosylation in concert with proteolysis to suppress plant defenses and promote parasitism. PLOS Pathog. 13, e1006301. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006301 (2017).

Jagdale, S., Rao, U. & Giri, A. P. Effectors of root-knot nematodes: an arsenal for successful parasitism. Front. Plant. Sci. 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.800030 (2021).

Jaouannet, M. et al. The root-knot nematode calreticulin Mi-CRT is a key effector in plant defense suppression. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 26, 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1094/mpmi-05-12-0130-r (2013).

Joshi, I. et al. Conferring root-knot nematode resistance via host-delivered RNAi-mediated Silencing of four Mi-msp genes in Arabidopsis. Plant. Sci. 298, 110592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110592 (2020).

Yu, J. et al. A root-knot nematode effector targets the Arabidopsis cysteine protease RD21A for degradation to suppress plant defense and promote parasitism. Plant. J. 118, 1500–1515. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.16692 (2024).

Huang, Q. et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of the susceptibility gene OsHPP04 in rice confers enhanced resistance to rice root-knot nematode. Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 1134653. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1134653 (2023).

Wang, Y., Li, X., Fan, B., Zhu, C. & Chen, Z. Regulation and function of defense-related Callose deposition in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. Online. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22052393 (2021).

Levy, A., Erlanger, M., Rosenthal, M. & Epel, B. L. A plasmodesmata-associated beta-1,3-glucanase in Arabidopsis. Plant. J. 49, 669–682. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02986.x (2007).

Xu, L. H. et al. Plasmodesmata play pivotal role in sucrose supply to Meloidogyne graminicola-caused giant cells in rice. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 22, 539–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/mpp.13042 (2021).

Abou-Saleh, R. H. et al. Interactions between Callose and cellulose revealed through the analysis of biopolymer mixtures. Nat. Commun. 9, 4538. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06820-y (2018).

Meidani, C., Ntalli, N. G., Giannoutsou, E. & Adamakis, I. S. Cell wall modifications in giant cells induced by the plant parasitic nematode Meloidogyne incognita in wild-type (Col-0) and the fra2 Arabidopsis Thaliana Katanin mutant. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20215465 (2019).

Gleason, C. A., Liu, Q. L. & Williamson, V. M. Silencing a candidate nematode effector gene corresponding to the tomato resistance gene Mi-1 leads to acquisition of virulence. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 21, 576–585. https://doi.org/10.1094/MPMI-21-5-0576 (2008).

Chronis, D. et al. Potato transformation. BIO-PROTOCOL 4 https://doi.org/10.21769/BioProtoc.1017 (2014).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408, (2001). https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Nicot, N., Hausman, J. F., Hoffmann, L. & Evers, D. Housekeeping gene selection for real-time RT-PCR normalization in potato during biotic and abiotic stress. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 2907–2914. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/eri285 (2005).

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH image to imageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 671–675. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2089 (2012).

Mason, K. N., Ekanayake, G. & Heese, A. Staining and automated image quantification of Callose in Arabidopsis cotyledons and leaves. Methods Cell. Biol. 160, 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.mcb.2020.05.005 (2020).

Karnovsky, M. A. Formaldehyde-glutaraldehyde fixative of high osmolality for use in electron microscopy. J Cell. Biol 27 (1964).

Claude, A. Studies on cells: Morphology, chemical constitution, and distribution of biochemical functions. Harvey Lect. 43, 121–164 (1948).

Spurr, A. R. A low-viscosity epoxy resin embedding medium for electron microscopy. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 26, 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5320(69)90033-1 (1969).

Acknowledgements

Justyna Frankowska-Łukawska, SGGW Warsaw, for excellent ultramicrotomy work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB and HP: data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results. MS: microscopy, image analysis, and interpretation of results. CG: supervision, writing, review & editing, project administration. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bali, S., Sobczak, M., Peng, H. et al. Solanum tuberosum glucan synthase-like 05 is involved in root-knot nematode Meloidogyne hapla parasitism. Sci Rep 16, 3632 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33647-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33647-7