Abstract

Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs) are crucial for enhancing efficiency in logistics automation. To address path planning inefficiencies in complex warehouse environments, an improved A-star algorithm is proposed. A three-neighborhood search strategy is introduced, incorporating obstacle detection and dynamic direction adjustment to eliminate redundant node traversal. Additionally, an optimized evaluation function is developed by integrating a predictive cost weighting coefficient based on OPEN list. Comparative simulations on large-scale maps with varying obstacle densities demonstrate the algorithm’s superiority and robustness. Results indicate that compared to Dijkstra and traditional A-star, the proposed method reduces search node traversal by up to 95.9% and 37.6%, respectively, and computation time by 94.8% while maintaining optimal path length. The algorithm exhibits consistent performance advantages across different environmental complexities, validating its scalability and reliability for real-time logistics applications. Furthermore, comparative analysis with state-of-the-art planners (e.g., JPS, Theta*) highlights its practical advantage of balancing high performance with implementation simplicity within the standard A-star framework, ensuring easy integration for real-world AGV systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background and significance

In modern logistics warehouses, the application of Automated Guided Vehicle (AGV)s has become one of the key technologies to improve efficiency and reduce costs. By integrating advanced sensors, algorithms and software systems, these AGVs are able to travel automatically inside the warehouse and perform tasks such as handling, sorting and storage of goods1.AGV can work for a long time without interruption, which significantly improves the operational efficiency of the warehouse. It reduces human error and waiting time compared to traditional manual handling, thus speeding up the flow of goods. Its design allows them to operate flexibly in different warehouse layouts and environments2. As business needs change, it can be easily reprogrammed and deployed to accommodate new workflows without the need for extensive infrastructure modifications. By reducing manual operations, AGVs reduce the risk of workplace accidents. At the same time, they reduce the likelihood of damage and loss of goods by ensuring accurate placement and sorting of goods through precise planning and control techniques3. AGVs can also be adapted to different environmental conditions, whether it is a low temperature refrigerated warehouse or a high temperature storage area, they can operate stably and ensure the safe storage of goods in various environments4.

The application of AGVs in logistics warehouses not only improves operational efficiency and reduces costs, but also enhances the flexibility and safety of warehouse transportation, which is an indispensable part of modern logistics automation5. The development of AGV primarily relies on path planning. Path planning efficiency and trajectory tracking accuracy are key factors in enhancing the overall performance of logistics carts. Path planning efficiency directly determines the system’s response speed and resource utilization efficiency. Efficient path planning algorithms generate optimal routes, significantly reducing energy consumption. Simultaneously, they rely on real-time obstacle avoidance and multi-vehicle coordination mechanisms to effectively prevent system congestion and enhance overall throughput.

Dynamic obstacles in logistics settings necessitate real-time path and motion adjustments, making algorithms crucial for autonomous obstacle avoidance and precise navigation. Without manual remote control, these algorithms sense the environment to plan and track paths in real time, making them suitable for structured settings like warehouses and workshops. Over past decades, numerous path planning algorithms including Dijkstra6,7, A-star8, RRT9,10, DWA11 and APF12 have emerged and gained extensive application across various fields. Owing to its efficient search capability13, A-star is widely adopted for solving path planning problems in static environments. As an extension of Dijkstra’s algorithm, A-star achieves rapid node search through heuristic functions, where different heuristic formulations exert notable impacts on search efficiency. Nevertheless, A-star still exhibits limitations affecting practical search performance: The substantial storage overhead from node records in the OPEN list may compromise real-time vehicle path planning14,15. Consequently, numerous scholars have proposed corresponding enhancement algorithms to address these shortcomings.

In 2020, Shang et al.16introduced key points around obstacles and variable stride strategies, enabling earlier obstacle avoidance and enhancing computational efficiency. That same year, Wu et al.17proposed the bidirectional adaptive A-star, balancing search efficiency and path accuracy through directional search and adaptive strategies. In 2021, Tang et al.18 introduced the Geometric A-star, which effectively resolved jagged and intersecting paths generated by traditional algorithms by filtering nodes using functions. By 2022, optimization approaches shifted toward multi-algorithm fusion. Li et al.19combined A-star and DWA, employing adaptive stride and cubic Bézier curves to optimize path smoothness. Separately, Liu et al.20 integrated A-star with APF. By incorporating safety terms into cost functions or selecting key nodes as gravitational centers, they enhanced path safety and fluidity. In 2023, Zhang et al.21adopted a bidirectional search strategy based on grid-based environment modeling, further reducing the number of nodes traversed by the algorithm. In 2024, improvements focused more on refinement and practicality. Xu et al.22 introduced local map scaling technology, significantly reducing planning time and path length.

To enhance the A-star, a three-neighborhood Search Strategy is adopted, incorporating an obstacle detection mechanism and dynamically adjusting the search direction. It reduces searched nodes and optimizes path length. And a weighting coefficient for estimated costs is added to the evaluation function, thereby improving efficiency. Data experiments demonstrate that, on the same map, the improved A-star achieves faster search speeds, explores fewer nodes, and generates shorter paths compared to the traditional A-star. Validating that the improved algorithms in this paper are more advantageous for path planning and enhancing search efficiency.

Research foundation and design

Research scope and contributions

This research focuses on path planning within static, non-dynamic scenarios. Given the inherent characteristics of logistics warehouse environments—where map layouts are typically fixed and do not change frequently—this study selects such settings as the benchmark for algorithm validation. The navigation task of AGVs within fixed warehouse maps serves as our concrete scenario. This scenario has clear requirements for path optimality and computational efficiency, and its static nature allows us to concentrate on evaluating the core search performance of the algorithm without the need to account for real-time dynamic responses. All experiments are conducted based on predefined simulated grid maps and do not involve dynamic obstacles or deployment in real physical systems, thereby ensuring a pure and fair comparison of the algorithms’ intrinsic computational performance. The evaluation is strictly centered on the following three core algorithmic metrics:

-

1.

Search Complexity: Measured by the number of expanded nodes, reflecting the utilization of the search space.

-

2.

Computational Efficiency: Measured by the execution time required to generate the final path, indicating its potential for real-time application.

-

3.

Solution Optimality: Measured by the final path length, ensuring that the improvements do not sacrifice fundamental optimality.

The scope of this work explicitly excludes the evaluation of system-level engineering metrics, such as dynamic obstacle avoidance, robustness to sensor noise, multi-agent coordination, path smoothness, and physical safety analysis. By confining the assessment to the aforementioned core computational metrics, this research aims to isolate and precisely quantify the contribution of the proposed algorithmic improvements per se, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for their future integration and application as a high-performance foundational planner within more complex systems.

Environment modeling

Constructing a map environment is the basis of path planning and provides the necessary search environment. By constructing a map through 2D graphics, the actual environment in which the AGV is located can be represented as a 2D terrain, thus simplifying its operation space. Common graphical algorithms mainly include grid, topology and visual map, as Table 1. The grid discretizes the external environment into grids of the same size based on a specific resolution, and each grid is represented by a state, including occupied and idle states, to indicate the presence or absence of obstacles at that location. In path planning, algorithm occupies a grid and plans a path consisting of multiple grids by searching for empty grids to avoid obstacles. The topology method divides the robot’s working environment into several small spaces and creates a topological network structure by connecting lines, and the path planning searches in this network to plan a path consisting of topological connecting lines. The visual graph method connects the start position, obstacles various turning points and destinations two by two to form a multilineage path structure. With the help of path planning, the complete path from the start location to the destination can be determined on these line segments.

Path planning in logistics warehouses faces significant challenges across mapping methodologies. The topological approach becomes prohibitively complex with numerous obstacles, degrading search efficiency. The visibility graph method exhibits high path-planning redundancy and low efficiency, rendering it unsuitable for warehouse applications. While grid-based mapping resolution directly impacts obstacle information fidelity—where higher resolution captures more detail but exponentially increases grid nodes and computational load—the A-star algorithm’s requirements and AGV operational scenarios permit a fixed resolution. Critically, a single resolution determination suffices for repeated map construction in identical warehouse environments, eliminating recurring calibration needs.

Given these comparative limitations, the grid method is selected for mapping obstacle distributions and path networks. This technique encodes node states into a matrix-represented grid map, followed by binarization: 0 denotes traversable grids (white), 1 represents obstacles (black). As exemplified in Figure 1, the start and target grids are annotated green and red, respectively. The rasterized environment partitions the warehouse into contiguous grid cells, each acting as a discrete map node. For real-world scaling, a 1 m × 1 m grid resolution is adopted, enabling target searches within this spatially optimized framework.

The improved A-star algorithm: Design and theoretical analysis

Three-neighborhood search strategy

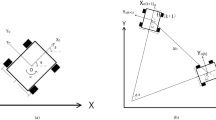

The neighborhood search strategy is critical for pathfinding efficiency. Traditional methods include Four-Neighborhood and Eight-Neighborhood searches:

Four-Neighborhood (Figure 2a) restricts movement to horizontal and vertical directions (up, down, left, right). As shown in Figure 3a, this limitation results in elongated paths, reducing efficiency. Eight-Neighborhood (Figure 2b) allows diagonal movement. While it optimizes path length, it introduces a risk of “cutting corners” through obstacles, as depicted in Figure 3(b). Specifically, if two adjacent nodes are obstacles, the diagonal path between them is also considered impassable.

To address these limitations, this paper proposes a Three-Neighborhood Search Strategy. This method improves upon the eight-Neighborhood approach by incorporating an obstacle detection mechanism:

-

1.

Obstacle Pruning(Figure 4(a) to Figure 4 (b)): If two adjacent nodes in the cardinal directions are obstacles, the diagonal path between them is treated as blocked and excluded from the search.

-

2.

Dynamic Direction(Figure 4(b) to Figure 4 (c)): The search direction is dynamically aligned with the vector connecting the current node to the goal node, thereby selecting the most suitable neighboring nodes as successor nodes for expansion.

As validated in Table 2 and Figure 5, the proposed three-neighborhood strategy significantly enhances performance. Compared to the Four-Neighborhood approach, it reduces path length from 58 m to 46.1127 m. Compared to the Eight-Neighborhood approach, it reduces the search space from 125 nodes to 82 nodes, achieving optimal path length with minimal computational cost.

Dynamically weighted evaluation function

Optimization of the evaluation function fundamentally relies on the selection of an appropriate distance model for the heuristic function. The choice of distance metric plays a decisive role in determining the pathfinding efficiency of A-star and its adaptability to unknown environments23, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Common distance heuristics include Manhattan, Euclidean, and Chebyshev distances, defined as follows:

Manhattan distance:

Euclidean distance:

Chebyshev distance:

To evaluate the impact of these distance models on the A-star, comparative simulations were conducted on a 30×30 grid map. The study focused on assessing search speed and the number of expanded nodes under each heuristic. The experimental results, presented in Figure 7 and Table 3, indicate significant performance differences. The data in Table 3 demonstrates that the Manhattan Distance model drastically reduces the search space, traversing only 125 nodes compared to 814 nodes for both Euclidean and Chebyshev distances. Furthermore, the path generated using Manhattan Distance is shorter (47.1127 m) and exhibits fewer unnecessary turns, aligning more closely with the kinematic constraints of AGVs. Consequently, due to its superior performance in minimizing search redundancy and optimizing path length, Manhattan Distance is selected as the heuristic function for this study Figure 8.

The A-star is widely utilized for optimal path planning due to its high efficiency. Its fundamental procedure involves managing an OPEN list and a CLOSE list. The start node is initialized in the OPEN list with an estimated total cost calculated via the evaluation function expressed in Equation (4):

where F(n) represents the total estimated cost from the start node to the target node via node n; G(n) denotes the actual cost incurred from the starting node to the current node; and H(n) is the heuristic predicted cost from the current node to the target.

The accuracy of H(n) is critical to the planning performance and computational efficiency of the algorithm. Since F(n) is jointly determined by G(n) and H(n), this paper proposes an optimized evaluation function by introducing a dynamic weighting coefficient to H(n). The improved function is defined as:

where \(x\) represents the number of nodes currently in the OPEN list. The parameter \(\alpha\) is set to 0.0005 and is designed to balance exploration and exploitation during the search process. Through preliminary experiments, it was observed that when \(\alpha\) falls within the range \([0.0001, 0.0009]\), the algorithm maintains stable performance across various types of maps, including structured warehouse layouts and more complex general environments. This indicates a degree of robustness to parameter variation. The value \(\alpha =0.0005\) was chosen as a representative value within this stable interval, reflecting the design goal of pursuing consistent and predictable performance improvement, rather than fine-tuning for peak performance in a specific scenario.

To validate the proposed method, it is compared against other improved A-stars from recent literature. Reference22 proposes an evaluation function that incorporates obstacle information:

In Equation (6), r denotes the number of obstacles between the current node and its parent node, and omega is an estimated parameter for obstacle cost. This approach attempts to predict additional path costs caused by obstacles.

Reference24 utilizes an exponential heuristic function:

Simulations were conducted to compare the Traditional A-star (Eq. (4)), the method from Reference22 (Eq. (6)), the method from Reference24 (Eq. (7)), and the Improved A-star proposed in this paper (Eq. (5)). To systematically integrate the proposed three-neighborhood search and the dynamic weighting strategy, the complete computational procedure is detailed in Figure 9. The comparative results are presented in Figure 10.

Comparison of Traditional A-star, Reference 22, Reference 24 and Improved A-star (a) Traditional in 50×50 (b) Reference 22 in 50×50 (c) Reference 24 in 50×50 (d) Improved in 50×50 (e) Traditional in 80×80 (f) Reference 22 in 80×80 (g) Reference 24 in 80×80 (h) Improved in 80×80 (i) Traditional in 100×100 (j) Reference 22 in 100×100 (k) Reference 24 in 100×100 (l) Improved in 100×100.

Algorithm flow and implementation

The complete workflow of the proposed improved A-star algorithm is illustrated in Figure 8, which integrates the three-neighborhood search strategy with the optimized evaluation function. The corresponding pseudocode is provided in Algorithm (see also Figure 8 for a combined visual representation). The core procedural steps are mapped to the pseudocode as follows:

-

1.

Initialization (Lines 1−3): Initialize the OPEN and CLOSE lists, set the g and h costs for the start node, and add it to the OPEN list.

-

2.

Node Selection (Lines 4−6): Select and remove the node n with the minimum f-cost from the OPEN list. If OPEN is empty, the search fails. Move n to the CLOSE list. If n is the goal node, reconstruct and return the path.

-

3.

Neighborhood Expansion (Lines 7−8): Apply the three-neighborhood search strategy (Strategy 1) to generate up to three candidate neighbor nodes aligned with the direction towards the goal. If no such neighbors are found (e.g., in dead ends), the algorithm reverts to the standard eight-neighborhood search as a fallback.

-

4.

Dynamic Weight Calculation (Lines 9−10): Compute the adaptive weight w using the exponential decay function exp(-α · N_total), where N_total is the current total number of explored nodes (|OPEN| + |CLOSE|). This embodies Strategy 2: Dynamic Weighting.

-

5.

Neighbor Evaluation & Update (Lines 11−20): For each valid (non-obstacle, not in CLOSE) neighbor:

-

1.

Calculate its tentative g_new cost (Line 14).

-

2.

Compute its heuristic h_new cost using Manhattan distance (Line 15).

-

3.

Determine its f_new cost using the dynamically weighted heuristic: f_new = g_new + w * h_new (Line 16).

-

4.

If the neighbor is not in the OPEN list or if the new g_new is lower than its previously recorded g cost, update its cost values and parent pointer, and insert it into the OPEN list (Lines 17−18).

-

1.

-

6.

Iteration (Lines 4−20): Repeat steps 2–5 until the goal is found (success) or the OPEN list is exhausted (failure).

This integrated design ensures that the search is both directional (reducing node expansion) and adaptively informed (balancing exploration and exploitation), leading to the significant efficiency gains demonstrated in the experiments.

Complexity analysis

Algorithm complexity analysis provides the theoretical foundation for evaluating the scalability and efficiency of path planning algorithms. This section analyzes the time and space complexity of the proposed improved algorithm and compares it theoretically with the traditional A-star.

The worst-case time complexity of the traditional A-star is \(O({b}^{d})\), where \(b\) is the branching factor (\(b=8\) for eight-neighborhood search) and \(d\) is the length of the shortest path from start to goal (approximately the solution depth). The proposed three-neighborhood search strategy, through directional constraints and obstacle pruning, reduces the effective branching factor from 8 to approximately \({b}^{\rm{^{\prime}}}\approx 3.5\) (an empirical estimate between Four and Eight Neighborhoods). Consequently, the time complexity of the improved algorithm is approximately \(O({b}^{\rm{^{\prime}}d})\). Since \({b}^{\rm{^{\prime}}}<b\), as the problem scale \(d\) increases (i.e., larger map sizes), the relative advantage of our algorithm in terms of the number of searched nodes expands exponentially. This theoretically explains its superior scalability on large-scale maps. This estimate is derived from a statistical analysis of the actual effective moving directions in three-neighborhood searches across different map structures.

The space complexity of the improved algorithm remains the same as traditional A-star, i.e., \(O({b}^{d})\), as it needs to store node information in the OPEN and CLOSE lists. However, due to the significant reduction in the number of actually expanded nodes, the peak memory usage is correspondingly lower. Specifically, storing each node requires a fixed-size data structure, so the total memory consumption is proportional to the number of expanded nodes.

This chapter integrates the three-neighborhood search strategy and dynamically weighted evaluation function, presenting the complete flowchart and pseudocode of the improved A-star, along with a theoretical complexity analysis. The analysis indicates that while the improvements do not alter the order of magnitude of the algorithm’s complexity, they significantly reduce the base \(b\) in the complexity expression by lowering the effective branching factor. This implies that for problems of the same scale, the improved algorithm can obtain the optimal solution with fewer computational resources. This theoretical expectation will be comprehensively verified through the experiments presented in Chapter 4.

Experimental verification and comparative analysis

Performance analysis under different map scales

To quantify the magnitude of performance improvement, the Maximum Decrease Ratio is calculated using Equation (8), which benchmarks the improved algorithm against the traditional A-star across core metrics. As shown in Table 4, on the 50×50 map, the improved algorithm achieves a maximum decrease ratio of 37.5% in searched nodes and 36.7% in computation time. As the map scales to 80×80 and 100×100, these ratios remain stable at 34.5%/34.2% and 37.6%/37.8%, respectively. These values, derived from Equation (8), are consistent and significant, providing statistical evidence that: 1) The efficiency gains from the proposed improvements (three-neighborhood strategy and dynamic weighting) are real and reproducible; 2) These gains are scalable across different problem sizes and do not diminish with the growth of the state space. Visually, Figure 10 corroborates this: the improved algorithm (subfigures d, h, l) exhibits a more focused search area, effectively avoiding the expansive exploration in non-promising directions seen in the traditional A-star (subfigures a, e, i), which directly explains the substantial reduction in expanded nodes.

Robustness analysis under different obstacle densities

This section employs Equation (8) to evaluate the algorithm’s robustness as environmental complexity increases. As detailed in Figure 11 and Table 5, in cluttered environments with obstacle densities of 30%, 40%, and 50%, the improved algorithm achieves maximum decrease ratios in searched nodes of 36.3%, 31.7%, and 33.0%, respectively, compared to the traditional A-star. The corresponding reductions in computation time are 35.1%, 30.3%, and 32.1%. These data, calculated via Equation (8), demonstrate that even with a substantial increase in environmental congestion, the performance advantage of the improved algorithm remains stable, with reductions consistently above 30%. This validates that the obstacle pruning and dynamic direction adjustment in the three-neighborhood search, coupled with the adaptive weighting in the evaluation function, effectively counteract the explosive growth in search space complexity caused by dense obstacles. Notably, at 30% and 40% densities, the improved algorithm finds shorter paths (Table 5), indicating that its optimization strategies not only accelerate the search but also enhance the ability to discover superior solutions in complex environments.

Comparison of Traditional A-star, Reference 22, Reference 24 and Improved A-star in different obstacle densities (a) Traditional in 30% (b) Reference 22 in 30% (c) Reference 24 in 30% (d) Improved in 30% (e) Traditional in 40% (f) Reference 22 in 40% (g) Reference 24 in 40% (h) Improved in 40% (i) Traditional in 50% (j) Reference 22 in 50% (k) Reference 24 in 50% (l) Improved in 50%.

Comprehensive comparison with various classical algorithms

To comprehensively position the performance of the improved algorithm, this section compares it against a range of classical algorithms, including uninformed searches (Dijkstra, BFS), greedy search (Best-First), and other A-star variants (e.g., Bidirectional A-star), as comprehensively compared in Figure 12. The quantification of performance improvement here employs Equation (9), which benchmarks the improved algorithm against any other algorithm to calculate its relative advantage. The data in Table 6, interpreted through Equation (9), reveals a difference of orders of magnitude: compared to Dijkstra and BFS algorithms, the improved algorithm achieves maximum decrease ratios exceeding 94% in both searched nodes and computation time. Even compared to the traditional A-star, the maximum decrease ratios reach 37.6% for nodes and 37.8% for time (consistent with Table 4 and aligned with the calculation principle of Equation (8)). When compared to optimized variants like Bidirectional A-star, it still maintains a nearly 5-fold speed advantage. The results calculated by Equation (9) unequivocally demonstrate that the proposed improvements are not only highly effective within the A-star family but also exhibit overwhelming efficiency advantages over classical "brute-force" and simple heuristic searches, all while strictly maintaining the same optimal path length as Dijkstra and the traditional A-star.

Comparative analysis with advanced algorithms: JPS and theta-star

The comparison with JPS and Theta-star (Table 7, Figure 13) reveals fundamental differences in design philosophy and performance trade-offs among algorithms. JPS achieves exceptional search efficiency in uniform grid worlds (162 nodes, 21.27 s) through its unique jump-point pruning strategy. Theta-star bypasses grid discretization constraints via line-of-sight checks and any-angle movement, finding a geometrically shorter path (146.04 m) but at a substantial computational cost (1653 nodes, 233.03 s). The improved A-star proposed herein finds a clear position: operating within the standard A-star framework, it achieves search efficiency approaching that of JPS (286 nodes vs. 162 nodes, 41.97 s vs. 21.27 s) and the same grid-optimal path length as JPS (152.89 m), while avoiding JPS’s specialized data structures. Compared to Theta-star, it trades a negligible increase in path length (152.89 m vs. 146.04 m, an increase of 4.7%) for a more than 5-fold improvement in computation speed (41.97 s vs. 233.03 s). The key conclusion from this comparative analysis is that the proposed algorithm is a highly practical engineering compromise. It does not pursue the limit of any single metric but achieves an excellent balance among efficiency, optimality, implementation complexity, and system compatibility, making it an ideal candidate for efficient and low-cost upgrades within existing AGV systems where A-star is already widely adopted.

This chapter provides a comprehensive validation of the proposed improved A-star algorithm through a series of systematic simulation experiments. The results demonstrate that the algorithm exhibits significant advantages in terms of efficiency, optimality, and robustness. Specifically, on maps of varying scales (from 50×50 to 100×100), the algorithm stably reduces the number of searched nodes and computation time by approximately 30%−38% while maintaining optimal or even superior path lengths, proving its excellent scalability. In complex environments with different obstacle densities (30% to 50%), its performance advantages remain stable, verifying its strong environmental robustness. Compared to classical algorithms such as Dijkstra and BFS, the improved algorithm achieves an order-of-magnitude improvement in efficiency (with reduction rates exceeding 94% in both nodes and time). The comparison with advanced algorithms like JPS and Theta-star further clarifies its position: operating within the standard A-star framework, it achieves an optimal engineering balance between search efficiency approaching JPS and path quality rivaling Theta-star, combining high efficiency, optimality, low implementation complexity, and good compatibility. These results provide a solid experimental foundation for the practical application of this algorithm in large-scale, complex static warehouse environments.

Conclusions

This work addresses the efficiency challenges of AGV path planning in large-scale warehouse environments by proposing an improved A-star algorithm. The key contributions and findings are as follows:

-

1.

Neighborhood Optimization: A three-neighborhood search strategy is proposed. By pruning invalid diagonal moves through obstacle detection and dynamically aligning the search direction with the target vector, redundant node expansion is significantly minimized.

-

2.

Evaluation Function Optimization: The evaluation function is improved by introducing a dynamic weighting coefficient based on the size of the OPEN list. This design dynamically balances heuristic guidance and exact cost calculation throughout the planning process, thereby harmonizing search speed with path optimality.

-

3.

Comprehensive Performance Validation and Theoretical Analysis: Extensive simulation experiments and theoretical complexity analysis were conducted on grid maps of various scales (up to 100×100) and under different obstacle densities (30%, 40%, 50%). The results show that while maintaining optimal or even shorter path lengths, the improved algorithm reduces the number of searched nodes by up to 37.6% and the computation time by up to 37.8% compared to the traditional A-star. Compared to brute-force search algorithms like Dijkstra, the reduction rates reach 95.9% in nodes and 94.8% in time. Theoretical analysis indicates the improvement enhances efficiency by reducing the effective branching factor. The algorithm demonstrates strong robustness in cluttered environments, maintaining stable efficiency advantages as map size increases (scalability) and obstacle density rises (robustness). Comparative analysis with advanced algorithms such as JPS and Theta* further confirms that the proposed method achieves significant efficiency improvements within the standard A-star framework, while striking a good balance among implementation complexity, compatibility, and overall performance.

In summary, the improved A-star algorithm presented in this paper provides an efficient, robust, and readily integrable solution for AGV path planning in complex static environments, supporting the further development of intelligent logistics systems.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Štaffenová, K., Rakyta, M. & Biňasová, V. The use of automated guided vehicles in the internal logistics of the production company. Transp. Res. Procedia 74, 458–464 (2023).

Wang, C. & Mao, J. Summary of AGV Path Planning. In 2019 3rd International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering (EITCE) 332–335 https://doi.org/10.1109/EITCE47263.2019.9094825 (2019).

Sun, Y., Fang, M. & Su, Y. AGV path planning based on improved Dijkstra algorithm. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1746, 012052 (2021).

Moshayedi, A. J., Li, J. & Liao, L. AGV (automated guided vehicle) robot: Mission and obstacles in design and performance. J. Simul. (2019).

Xiong, C., Wang, C., Zhou, S. & Song, X. Dynamic rolling scheduling model for multi-AGVs in automated container terminals based on spatio-temporal position information. Ocean Coast. Manag. 258, 107349 (2024).

Alshammrei, S., Boubaker, S. & Kolsi, L. Improved Dijkstra algorithm for mobile robot path planning and obstacle avoidance. Comput. Mater. Contin. 72, 5939–5954 (2022).

Implementation of Dijkstra’s Algorithm to Determine the Shortest Route in a City. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. Telecommun. Eng. https://doi.org/10.30596/jcositte.v2i1.6503https://doi.org/10.30596/jcositte.v2i1.6503 (2021).

Hao Ge et al. Improved A* algorithm for path planning of spherical robot considering energy consumption. 23, 7115–7115 (2023).

Huang, G. & Ma, Q. Research on path planning algorithm of autonomous vehicles based on improved RRT algorithm. Int. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. Res. 20, 170–180 (2022).

Gan, Y. et al. Research on robot motion planning based on RRT algorithm with nonholonomic constraints. Neural. Process. Lett. 53, 3011–3029 (2021).

Jin, M. & Wang, H. Robot path planning by integrating improved A* algorithm and DWA algorithm. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2492, 012017 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. AAPF*: a safer autonomous vehicle path planning algorithm based on the improved A* algorithm and APF algorithm. Clust. Comput. 27, 11393–11406 (2024).

Fransen, K. & van Eekelen, J. Efficient path planning for automated guided vehicles using A* (Astar) algorithm incorporating turning costs in search heuristic. Int. J. Prod. Res. 61, 707–725 (2023).

Candra, A., Budiman, M. A. & Hartanto, K. Dijkstra’s and A-star in finding the shortest path: A Tutorial. In 2020 International Conference on Data Science, Artificial Intelligence, and Business Analytics (DATABIA) 28–32 https://doi.org/10.1109/DATABIA50434.2020.9190342 (2020).

Ju, C., Luo, Q. & Yan, X. Path Planning using an improved A-star algorithm. In 2020 11th International Conference on Prognostics and System Health Management (PHM-2020 Jinan) 23–26 https://doi.org/10.1109/PHM-Jinan48558.2020.00012 (2020).

Erke, S. et al. An improved A-Star based path planning algorithm for autonomous land vehicles. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 17, 1729881420962263 (2020).

Wu, X., Xu, L., Zhen, R. & Wu, X. Bi-directional adaptive A* algorithm toward optimal path planning for large-scale UAV under multi-constraints. IEEE Access 8, 85431–85440 (2020).

Tang, G., Tang, C., Claramunt, C., Hu, X. & Zhou, P. Geometric A-Star algorithm: An improved A-star algorithm for AGV path planning in a port environment. IEEE Access 9, 59196–59210 (2021).

Li, Yonggang et al. A mobile robot path planning algorithm based on improved A* algorithm and dynamic window approach. IEEE Access 10, 57736–57747 (2022).

Lisang, L. et al. Research on path-planning algorithm integrating optimization A-Star algorithm and artificial potential field method. Electronic 11, 3660–3660 (2022).

Zhang, H., Tao, Y. & Zhu, W. Global Path planning of unmanned surface vehicle based on improved A-star algorithm. Sensor 23, (2023).

Xu, B. Precise path planning and trajectory tracking based on improved A-star algorithm. Meas. Control 00202940241228725 (2024).

Foead, D., Ghifari, A., Kusuma, M. B., Hanafiah, N. & Gunawan, E. A Systematic Literature Review of A* Pathfinding. Proced. Comput. Sci. 179, 507–514 (2021).

Zhang, J., Wu, J., Shen, X. & Li, Y. Autonomous land vehicle path planning algorithm based on improved heuristic function of A-Star. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 18, 17298814211042730 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Sichuan Provincial Regional Innovation Cooperation Project, grant number 2024YFHZ0209; the Sichuan Provincial Regional Innovation Cooperation Project, grant number 2023YFQ0092; Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan, grant number 2023NSFSC0368.

Funding

Sichuan Provincial Regional Innovation Cooperation Project, 2024YFHZ0209, 2023YFQ0092, Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan, 2023NSFSC0368

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G., X.T. and K.D.; methodology, Y.G., H.Y. and T.H.; software, B.Z. and H.Y.; validation, X.T. and B.Z.; formal analysis, Y.G., B.Z. and X.T.; investigation, Y.G., T.H. and J.D.; resources, Y.G. and J.D.; data curation, X.T., T.H. and J.D.; writing—original draft, X.T., Y.G., and B.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.G., X.T., and L.H.; visualization, X.T. and K.D.; supervision, Y.G. and L.H.; project administration, X.T., K.D. and B.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.G., L.H. and B.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Y., Tong, X., Huang, L. et al. Research on AGV based on improved A-star algorithm. Sci Rep 16, 3629 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33653-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33653-9