Abstract

The use of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in very elderly patients (> 90 years) with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) remains debated due to limited evidence and the presence of multimorbidity. This study evaluated the impact of PCI using data from the Lombardy Health Database (Italy) for AMI patients hospitalized between 2003 and 2018. Among 15,954 patients (median age 92; 71% female; 50% with ST-elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI]), 12% underwent PCI. In-hospital mortality was lower in PCI-treated patients (15% vs. 23%; P < 0.0001). Overall, one-year mortality (56%) and rehospitalization for acute heart failure (AHF) or AMI (19%) were also reduced among PCI patients (37% vs. 58% and 16% vs. 21%, respectively; P < 0.0001). These findings were consistent across both STEMI and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) subgroups and were independent of comorbidities. Adjusted risk analyses and propensity score matching (1,950 patients per group) confirmed these benefits. The use of PCI increased significantly from 4% in 2003 to 22% in 2018, while in-hospital mortality declined from 22 to 19% (from 28 to 15% in the propensity-matched cohort). In conclusion, PCI was associated with significantly lower in-hospital and one-year mortality, as well as reduced rehospitalization rates, in AMI patients older than 90 years, regardless of comorbidities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the treatment of choice for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), serving as the primary revascularization strategy for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and as an urgent invasive approach for those with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)1,2. In both STEMI and NSTEMI patients, PCI has been associated with a substantial reduction in hospital and long-term mortality3,4.

The proportion of older individuals among patients with AMI is steadily rising in parallel with increased life expectancy, leading to a growing evidence that supports the benefits of PCI in these patients5,6. Current guidelines indicate that there is no upper age limit for considering PCI in AMI patients1,2. However, the routine use of PCI in very elderly AMI patients - specifically those over 90 years - remains challenging and controversial7.

These very elderly patients have been systematically excluded from cardiovascular trials, and their representation in clinical registries is low,8,9,10 resulting in limited evidence regarding the benefit of PCI during AMI and after discharge for this age group. Moreover, concerns about side effects associated with PCI, such as bleeding, renal, and vascular complications, along with more complex coronary artery disease, multimorbidity, and the potential for medical futility, further complicate the decision-making process for treating very elderly AMI patients with PCI8,9. In the absence of robust clinical data, observational studies involving large populations continue to provide insights into this unique cohort of AMI patients.

In this study, we analyzed administrative data from Lombardy, the most populated region in Italy with over 10 million inhabitants, to assess the prognostic impact of PCI in patients over 90 years old who were hospitalized with AMI. We also examined whether the rate of PCI use in this very elderly AMI population has increased over the past 15 years and whether this increase has been associated with improvements in overall hospital mortality, 1-year mortality, and 1-year re-hospitalization for acute heart failure (AHF) or AMI.

Results

Patient population and baseline characteristics

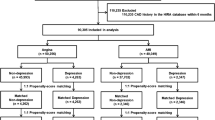

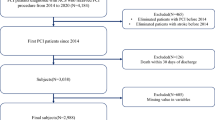

During the study period, 263,578 patients hospitalized with a primary diagnosis of AMI were identified. Of these, 15,954 patients (6%) were over 90-year-old (median age 92 [95% CI 91–94] years; 71% female; 50% STEMI). The patient flow diagram of the study is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. The clinical characteristics, chronic cardiovascular medications used before admission and after hospital discharge, and major in-hospital complications for the overall cohort of AMI patients over 90-year-old, categorized by whether they underwent PCI (yes vs. no) are presented in Table 1.

Patients who underwent PCI were 1,954 (12% of the entire cohort). They were more frequently diagnosed with STEMI, had fewer comorbidities with a lower MCS, and experienced a less complicated in-hospital clinical course. Additionally, discharged patients treated with PCI were more frequently prescribed cardiovascular medications compared to those who did not undergo PCI.

In-Hospital and long-term outcomes

The in-hospital mortality rate for the entire cohort was 22% (29% in STEMI and 15% in NSTEMI patients; P < 0.0001). One-year mortality was 56% (61% in STEMI and 51% in NSTEMI patients; P < 0.0001), while the 1-year re-hospitalization rate for AHF/AMI was 19% (17% in STEMI and 21% in NSTEMI patients; P < 0.0001). The rates of the primary and secondary endpoints in the entire population (Fig. 1), as well as in STEMI and NSTEMI patients considered separately (Fig. 2), were significantly lower in patients who underwent PCI compared to those who received only medical therapy.

(A) Rates of primary and secondary endpoints in STEMI patients, comparing those treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to those who were not. (B) Rates of primary and secondary endpoints in NSTEMI patients, comparing those treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to those who were not. AHF = acute heart failure; AMI = acute myocardial infarction.

Similarly. PCI use was associated with a lower adjusted risk for all the endpoints in the entire AMI population and in both STEMI and NSTEMI patients considered separately, (Fig. 3).

Adjusted risk of the primary and secondary endpoints associated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) use in the overall cohort of patients and in STEMI and NSTEMI patients considered separately. Odds ratios and hazard ratios were adjusted for the variables reported in Table 1, and found to be significantly different between patients treated with and not treated with PCI, including medications taken before index hospitalization for OR and those taken after hospital discharge for HR. AHF = acute heart failure; AMI = acute myocardial infarction; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; OR = odds ratio. *data presented as OR; **data presented as HR.

The Kaplan-Meier curves for 1-year mortality and re-hospitalization for AHF/AMI in patients treated with or without PCI are shown in Fig. 4.

The Kaplan-Meier curves in STEMI and NSTEMI patients considered separately are shown in Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3, respectively.

Sensitivity analysis: propensity score matching

After propensity score matching, the study population included 3,900 AMI patients (1,950 patients in each group). Baseline characteristics of study patients are shown in Supplementary Table 1. After matching, all variables were well-balanced among groups. The in-hospital mortality rate for the entire cohort was 18% (n = 710), with 24% in STEMI and 11% in NSTEMI patients. One-year mortality was 47% (n = 1,821), including 51% in STEMI and 42% in NSTEMI patients, while the 1-year re-hospitalization rate for AHF/AMI was 17% (n = 674), with 15% in STEMI and 20% in NSTEMI patients. The rates and risks of the primary and secondary endpoints in the matched population – comparing patients who underwent PCI with those who received medical therapy - are reported in Supplementary Table 2 for the overall population as well as for STEMI and NSTEMI subgroups. The benefits associated with PCI were confirmed in the matched population (OR 0.67 [95% CI 0.57–0.67] for in-hospital mortality; HR 0.57 [95% CI 0.52–0.63] for 1-year mortality; HR 0.97 [95% CI 0.82–1.16] for 1-year re-hospitalization for AHF/AMI).

Impact of comorbidities on PCI use and outcomes

Figure 5 shows the number of patients who underwent PCI across different MCS categories, along with the associated impact of this treatment on the mortality risk. As the number of comorbidities increased, the proportion of patients treated with PCI gradually decreased, yet the benefit of PCI remained consistent across all endpoints.

Upper panel. Rates of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) across different multisource comorbidity score (MCS) categories in the overall population. Lower panel. Adjusted risk of the in-hospital and 1 year-mortality associated with PCI use in the overall population grouped according to MCS score categories. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; OR = odds ratio.

Temporal trends in PCI use and mortality (2003–2018)

Figure 6 shows the rates of in-hospital mortality and PCI use over the study period (2003–2018).

The use of PCI significantly increased from 4% in 2003 to 22% in 2018, while in-hospital mortality significantly decreased from 22% to 19%. Over the same period, one-year mortality and 1-year re-hospitalization for AHF/AMI decreased from 57% to 50% and from 23% to 12%, respectively (P < 0.0001 for both endpoints). When in-hospital mortality in the matched population was considered, a decrease from 28% in 2003 to 15% in 2018 was observed (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 6). Similarly, one-year mortality and 1-year re-hospitalization for AHF/AMI decreased from 58% to 43% and from 16% to 15%, respectively (P < 0.0001 for both endpoints). The benefits of PCI on in-hospital and one-year mortality were consistently observed throughout the entire study period (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the potential clinical benefits of PCI in AMI patients aged over 90 years using data from the Lombardy Health Database (Italy) covering the period from 2003 to 2018. During this 15-year period, 6% of all AMI hospitalizations involved nonagenarians, 70% of whom were women. Notably, only 12% of these elderly patients underwent PCI, increasing, however, from 4% in 2003 to 22% in 2018. Our findings support an association between PCI use in this age group and lower in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates, as well as a reduced 1-year re-hospitalization for AHF/AMI. These results were consistent across both STEMI and NSTEMI patients and held true regardless of the comorbidity burden, as assessed by the MCS.

Older individuals, typically defined as those over 75 years, represent a substantial proportion of AMI hospitalizations, accounting for 30% of STEMI and over 40% of NSTEMI cases10,11. Notably, these patients have a significantly higher mortality rate, with a case fatality rate two to three times greater than that of younger patients12. Growing evidence from registries, hospital cohorts, and subgroup analyses of randomized trials indicates that PCI offers significant benefits to older AMI patients also10,11,12,13,14,15,16. However, it remains unclear whether these in-hospital and long-term benefits extend to very elderly AMI patients, specifically those over 90 years of age17,18,19,20. Notably, almost 10% of older AMI patients fall into this very old category with a mortality rate twice that of patients aged 75 to 89 years9,13,14,19,21. Despite their growing prevalence and poor outcomes, very old patients have often been excluded from major clinical trials of cardiovascular interventions due to concerns about their higher risk of adverse events and limited life expectancy21,22. Furthermore, prospective studies and registries that examine PCI in older AMI patients have generally considered only small populations and combined very old patients with those aged over 75 or 80 years23,24,25,26,27. To this regard, a recent randomized clinical trial (the British Heart Foundation older patients with non-ST SEgmeNt elevatIOn myocaRdial infarction Randomized Interventional TreAtment [SENIOR-RITA] trial) in patients aged 75 and older found that an invasive treatment approach did not significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular death or non-fatal AMI compared to a conservative approach, over a median follow-up period of 4.1 years28. However, the study only included patients with NSTEMI, and PCI was performed in 47% of patients who underwent coronary angiography. Additionally, the study population had a mean age of 82 years, and very few (n = 113) were aged 90 or older.

To our knowledge, only one large registry has specifically studied patients over 90 years, focusing on PCI trends and in-hospital mortality across years5. This registry included 69,271 nonagenarians undergoing PCI for STEMI, NSTEMI, or stable ischemic heart disease from 2003 to 2014. It found that, while the proportion of PCI among STEMI and NSTEMI patients increased significantly over time, in-hospital mortality increased for STEMI patients and remained unchanged for those with NSTEMI, likely due to worsening baseline risk profiles. Therefore, given the need for more data on which very old AMI patients may derive benefit from PCI, we analyzed a large administrative dataset to assess the outcomes associated with PCI in patients over 90 years old hospitalized with AMI.

Our analysis showed that very old AMI patients have an in-hospital mortality rate of 22%, a 1-year mortality rate of 56%, and a 1-year re-hospitalization for AHF/AMI of nearly 20%. However, those treated with PCI had significantly lower rates of in-hospital and 1-year mortality, regardless of whether they had STEMI or NSTEMI. Specifically, PCI reduced the adjusted risk of in-hospital mortality by 40% and the risk of 1-year mortality by 50%. Additionally, PCI was associated with a 30% lower adjusted risk of 1-year re-hospitalization for AHF/AMI. These benefits were consistent across both STEMI and NSTEMI patients.

Our findings suggest that PCI may offer clinical benefits to very old AMI patients and are broadly consistent with the European Society of Cardiology guidelines, which recommend that advanced age should not exclude STEMI patients from primary PCI and that older NSTEMI patients should receive the same interventional strategy as younger patients1,2,29. Notably, in our study, very old AMI patients who did not undergo PCI during hospitalization had an 80% chance of death or re-hospitalization for AHF/AMI within 1 year.

In this study, we also explored the changes in PCI utilization over time and its impact on mortality and re-hospitalization rates in this unique demographic. We observed a significant increase in PCI use over the 15-year study period, from 4% in 2003 to 22% in 2018, accompanied by a lesser impactful decrease in hospital mortality and 1-year outcomes. The observed modest reduction in mortality, despite the increase in PCI use, may be partly explained by the fact that nearly 80% of AMI patients still did not receive PCI in 2018, potentially missing its benefits. Nonetheless, in the propensity matched population, the beneficial effect of PCI on in-hospital mortality was more apparent. These findings suggest that further increases in PCI use could improve outcomes in this high-risk population.

Although several aspects, such as PCI-related complications, remain to be investigated, our data indicate that age alone should not exclude very old AMI patients from undergoing PCI. In our study, although the absolute incidence of blood transfusion (a surrogate of major bleeding), surgical vascular complications, and the need for dialysis due to acute kidney injury was small, these complications were more common in patients treated with PCI than in those not treated with PCI. Likewise, the presence of multiple comorbidities should not preclude PCI, as our study demonstrated persistent benefits even in patients with the highest MCS. Indeed, while the proportion of patients receiving PCI decreased with increasing comorbidity, the benefits of PCI remained consistent across different levels of comorbidity. This finding may further support that PCI can be beneficial even in the presence of significant comorbidities, challenging the perception that high comorbidity necessarily negates the potential benefits of PCI. Future research should focus on identifying which very old patients might not benefit from PCI rather than setting an arbitrary age limit for its use. Administrative databases are a valuable tool for describing outcomes in large cohorts and reflecting the real-world clinical settings, as they collect data over time in a standardized and cost-effective manner. To our knowledge, our study includes one of the largest cohorts of AMI patients over 90 years old, with follow-up extending one year beyond the index hospitalization. However, certain limitations inherent to retrospective studies based on administrative datasets should be acknowledged. Firstly, administrative data can be subject to systematic biases, as the quality of the data depends on the accuracy of coding. Our analysis relied on the accurate coding of AMI and other conditions, and potential biases may have arisen from underreporting or temporal changes in diagnosis, AMI definitions, and coding practices. In particular, the inability of ICD-9 codes to distinguish between different AMI types according to contemporary definitions - such as type 1 vs. type 2 AMI, or myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA) - must be acknowledged. However, the endpoints considered in our study, particularly in-hospital and 1-year mortality, are less likely to be affected by coding error. Secondly, some specific clinical variables or laboratory tests closely associated with AMI prognosis - such as left ventricular ejection fraction, renal function, extent of coronary artery disease, angiographic and PCI data, completeness of myocardial revascularization, and in-hospital pharmacologic therapy - were not available. Additionally, in very old patients, critical variables such as functional status, cognitive status, and patient preferences were not recorded. We also lacked information on the reasons for not performing PCI in conservatively treated patients, including late presentation, severe comorbidities, or different hospitalization settings. Furthermore, we could not determine how physician experience might have influenced PCI performance or treatment choices in elderly patients.

Moreover, since our study was based on administrative data without clinical event adjudication, we could not distinguish between cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular causes of death - an important issue in nonagenarians. Additionally, while the MCS accurately captures the comorbidity burden based solely on administrative data for the general population, it has not been specifically validated for AMI patients. However, it was developed and tested in a large administrative database from the same geographic area and population as our study. Lastly, our analysis concluded prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which profoundly affected Lombardy by reducing patient hospitalizations and follow-up activities.

Conclusions

This study, based on a large real-world dataset, demonstrated that in patients over 90 years of age hospitalized with AMI, PCI is associated with significantly lower in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates, as well as a reduced rate of 1-year re-hospitalization for AHF/AMI, compared to conservative treatment. These associations were observed in both STEMI and NSTEMI subgroups and across varying levels of comorbidity, findings that support a more inclusive approach to PCI in older populations, while recognizing that individual patient factors must guide decision-making. As PCI use continues to rise, further research and clinical trials are essential to strengthen the generalizability of these findings, optimize treatment strategies and improve outcomes for this increasingly, prevalent, and unique patient population.

Online methods

Data source

The present study utilized linkable administrative health databases from the Lombardy region in Italy, which include a population registry containing demographic data for all residents, along with detailed information on hospital records and drug prescriptions. Data are available for approximately 10 million registered inhabitants of Lombardy, spanning from 2000 to 2019. Access to this data was granted through an agreement between the Centro Cardiologico Monzino, I.R.C.C.S, Milan, Italy, and the Regional Health Ministry of Lombardy. Healthcare in Italy is publicly funded for all residents, regardless of social class or employment status, and each individual is assigned a personal identification number maintained in the National Civil Registration System. All registered residents are assisted by general practitioners and are covered by the National Health System (NHS), which provides comprehensive data on drug prescriptions, diagnoses, and length of observation. The pharmacy prescription database includes the medication name, the anatomic therapeutic chemical classification code (ATC), and the date of dispensation of drugs reimbursed by the NHS. The hospital database contains information on the date of admission, discharge, death, primary diagnosis, and up to five co-existing clinical conditions and procedures performed. Diagnoses are uniformly coded according to the 9th International Code of Diseases (ICD-9-CM) and standardized across all Italian hospitals. These diagnoses are compiled by the hospital specialists directly responsible for the patients and are validated by the hospitals against detailed clinical-instrumental data, as they determine reimbursement from the NHS. A unique identification code allows linkage of all databases. To ensure individual data protection, each identification code was automatically converted into an anonymous code before we received the dataset. In Italy, studies using retrospective anonymous data from administrative databases that do not involve direct access by investigators to identifying information do not require Ethics Committee approval or notification, nor do they require patient informed consent. The requirement for ethical approval for this study was waived by the Centro Cardiologico Monzino ethics committee. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, Centro Cardiologico Monzino IRB waived the need of obtaining informed consent. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Study population

Patients hospitalized due to AMI (either STEMI or NSTEMI) from January 1, 2003 through December 31, 2018, were considered. The ICD-9-CM codes used in this study are provided in Supplementary Table 2. Only cases where the AMI-related ICD-9 code was listed as the primary diagnosis were included. For patients who were transferred between hospitals, the entire episode of care was evaluated. Patients over 90 years of age were included in the final analyses and categorized based on whether or not they underwent PCI during the index hospitalization. Since medical data have been recorded in the Lombardy registry since January 2000, past medical history was available for all patients for at least three years before admission. Considering that in very elderly patients, the decision to undergo PCI is often influenced by the presence of significant comorbidities, we incorporated a multisource comorbidity score (MCS) into the analysis. This score, derived from data commonly used in health system management, has been validated in Italy for predicting both short-term and long-term risks of death and hospitalization30. The MCS include 46 diseases and conditions, with corresponding weights reported in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table 3). The score was categorized by assigning increasing values of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 to aggregate scores of 0–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15–19, and ≥ 20, respectively. Data collection was performed by trained reviewers.

Study outcomes

The primary endpoint of the study was in-hospital mortality. Secondary endpoints included 1-year all-cause mortality and 1-year re-hospitalization for AHF or AMI. Patients were followed from the index admission date until death, migration, or up to the end of the one-year follow-up period.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and were compared between patients treated with PCI and those not treated with PCI using t test for independent samples. Non-normally distributed variables are presented as medians and interquartile ranges and were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical data were analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

The association between in-hospital mortality and PCI was analyzed using a logistic regression model, and the results were reported as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The association between 1-year mortality and 1-year hospital readmission for AHF/AMI was investigated using either Cox regression or Cox regression for competing risk (Fine and Gray model), as appropriate, and Kaplan-Meier curves. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Results were expressed as hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI. The models were adjusted for all variables reported in Table 1 that were found to differ significantly between patients treated with PCI and those not treated with PCI. Subgroup analysis was performed for MCS class, and P-values for trends of in-hospital death and PCI rates were calculated using the ANOVA test.

Propensity score matching was performed to minimize confounding arising from imbalances in baseline covariates. The score was used to match two cohorts: AMI patients who underwent PCI and those who did not. Matching was performed in a 1:1 ratio using all variables listed in Table 1.

All analyses were conducted in the entire population and separately in STEMI and NSTEMI patients. A two-sided P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Regione Lombardia but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Contact to access data: olivia_leoni@regione.lombardia.it.

References

Collet, J. P. et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 42, 1289–1367 (2020).

Ibanez, B. et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 39, 119–177 (2018).

Boersma, E. Primary coronary angioplasty vs. Thrombolysis Group. Does time matter? A pooled analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing primary percutaneous coronary intervention and in-hospital fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction patients. Eur. Heart J. 27, 779–788 (2006).

Fox, K. A. et al. Long-term outcome of a routine versus selective invasive strategy in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55, 2435–2445 (2010).

Goel, K. et al. Temporal trends and outcomes of percutaneous coronary interventions in nonagenarians: A national perspective. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 11, 1872–1882 (2018).

Damluji, A. A. et al. Management of acute coronary syndrome in the older adult population: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 147, e32–e62 (2023).

Lee, P. Y., Alexander, K. P., Hammill, B. G., Pasquali, S. K. & Peterson, E. D. Representation of elderly persons and women in published randomized trials of acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 286, 708–713 (2001).

Tonet, E., Pavasini, R., Biscaglia, S. & Campo, G. Frailty in patients admitted to hospital for acute coronary syndrome: when, how and why? J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 16, 129–137 (2019).

Sawant, A. C. et al. Temporal trends, complications, and predictors of outcomes among nonagenarians undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the veterans affairs clinical Assessment, Reporting, and tracking program. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 10, 1295–1303 (2017).

Bauer, T. et al. Effect of an invasive strategy on in-hospital outcome in elderly patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 28, 2873–2878 (2007).

Savonitto, S. & De Servi, S. Early invasive approach and outcome in elderly patients with NSTEACS: randomized trials, real-world data and guideline recommendations. EuroIntervention 17, 20–21 (2021).

Morici, N. et al. Causes of death in patients ≥ 75 years of age with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol. 112, 1–7 (2013).

Skolnick, A. H. et al. Characteristics, management, and outcomes of 5,557 patients age > 90 years with acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE initiative. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 49, 1790–1797 (2007).

Alexander, K. P. et al. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part I: Non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndromes: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association Council on clinical cardiology: in collaboration with the society of geriatric cardiology. Circulation 115, 2549–2569 (2007).

Salinas, P. et al. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction in nonagenarian patients: results from a Spanish multicentre registry. EuroIntervention 6, 1080–1084 (2011).

Biondi-Zoccai, G. et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in nonagenarians: Pros and cons. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 10, 82–90 (2013).

Rosengren, A. et al. Age, clinical presentation, and outcome of acute coronary syndromes in the Euroheart acute coronary syndrome survey. Eur. Heart J. 27, 789–795 (2006).

Lee, M. S., Zimmer, R., Pessegueiro, A., Jurewitz, D. & Tobis, J. Outcomes of nonagenarians who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 71, 526–530 (2008).

Rasania, S. P. et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention outcomes in very elderly patients. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 10, 1273–1274 (2017).

Mandawat, A., Mandawat, A. & Mandawat, M. K. Percutaneous coronary intervention after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in nonagenarians. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61, 1207–1208 (2013).

Numasawa, Y. et al. Comparison of outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention in elderly patients, including 10,628 nonagenarians. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e011183 (2019).

Morici, N. et al. Management of acute coronary syndromes in older adults. Eur. Heart J. 43, 1542–1553 (2022).

Piegza, J. et al. Myocardial infarction in centenarians: data from the Polish registry of acute coronary syndromes. J. Clin. Med. 9, 3377 (2020).

Sato, K. et al. Temporal trends in geriatric patients with acute myocardial infarction in Japan. J. Cardiol. 75, 465–472 (2020).

Nishihira, K. et al. Impact of frailty on outcomes in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 7, 189–197 (2021).

Ahmed, O. E., Abohamr, S. I. & Abazid, R. M. In-hospital mortality of acute coronary syndrome in elderly patients. Saudi Med. J. 40, 1003–1007 (2019).

Petroni, T. et al. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST elevation myocardial infarction in nonagenarians. Heart 102, 1648–1654 (2016).

Kunadian, V. et al. Invasive treatment strategy for older patients with myocardial infarction. N Engl. J. Med. 391, 1673–1684 (2024).

Komócsi, A. et al. Underuse of coronary intervention and its impact on mortality in elderly patients. Int. J. Cardiol. 214, 485–490 (2016).

Corrao, G. et al. Developing and validating a novel multisource comorbidity score from administrative data. BMJ Open. 7, e019503 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all researchers involved in the EASY-NET network program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M., N.C., F.T, P.A. and G.D. wrote the main manuscipt text and interpretated the results.P.P., C.L. and D.M. prepared figures and tables; A.B., O.L. and S.S. made the statistical analysisAll authors reviewed manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marenzi, G., Cosentino, N., Mele, D. et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in nonagenarians with acute myocardial infarction: a 15-year population-based study. Sci Rep 16, 3624 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33662-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33662-8