Abstract

Coral reefs provide essential ecosystem services and livelihoods, particularly for small island nations like the Maldives. However, they are increasingly threatened by climate change and coastal modification. In 2022, the Greater Malé Connectivity Project (GMCP) commenced in North Malé Atoll, involving large-scale land reclamation and marine construction that affected adjacent coral reefs. As a mitigation measure, coral colonies were relocated to the reef surrounding Villimalé Island. Over two years of monitoring, relocated corals showed encouraging performance despite challenging environmental conditions. Overall survival reached 66%, with larger colonies outperforming smaller fragments and Pocillopora generally exhibiting higher growth and thermal resistance than Acropora. Growth rates declined with rising sea surface temperature, and mortality was primarily associated with tissue-loss responses rather than predation or ectosymbiotic colonisation. Health trajectories differed among coral types: Acropora fragments were more prone to bleaching, whereas Pocillopora colonies maintained tissue integrity but experienced chronic degradation. Despite these biological interactions and health challenges, many corals acclimatised to the urban reef environment, underscoring that coral relocation, when combined with species selection and size consideration, can serve as a viable short-term conservation tool in highly impacted systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although coral reefs cover approximately 284,000 km² globally, only 0.1% of the Earth’s surface, they are among the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet, hosting nearly a quarter of all known marine species1,2. These ecosystems provide essential services by supporting marine biodiversity3,4, offering coastal protection, and sustaining human livelihoods5,6. Beyond their ecological roles, coral reefs hold significant economic value through the goods and services they supply7. Despite their importance, coral reefs have faced increasing threats over recent decades due to the synergistic effects of global and local anthropogenic stressors8,9. Among the most destructive human-induced impacts are overfishing10, overtourism11, waste generation12, and particularly coastal modification9,13,14. These pressures raise serious concerns about reefs’ long-term resilience and their capacity to support biodiversity, fisheries, and coastal defence15. One of the most pressing global stressors is climate change, which has led to the intensification of marine heatwaves and an increase in the frequency and severity of mass coral bleaching events16,17. These events, often linked to large-scale climatic phenomena such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO)18,19, have resulted in widespread coral mortality20,21. In parallel, many small island nations face intense local stressors due to rapid development. In countries with limited land availability, extensive land reclamation has been employed to support urban expansion8,22,23,24. A central activity in reclamation projects is dredging, where a slurry of seabed material is extracted and discharged into shallow areas. Coarser sediments settle quickly near the site, while finer particles remain suspended, often travelling several kilometres depending on oceanographic conditions25,26. These suspended sediments degrade water quality by increasing turbidity and generating sediment plumes that reduce light penetration. For coral reefs, the primary consequences are reduced photosynthetic efficiency, since corals rely on symbiotic dinoflagellates for energy27,28, and smothering due to sediment deposition. Corals attempt to shed sediments using mucus and ciliary action29, but when deposition exceeds their capacity, tissue smothering and partial mortality can occur13. In addition to direct sediment stress, dredging can alter local hydrodynamics, resuspend nutrients and contaminants, and hinder coral recruitment and larval settlement, ultimately compromising reef resilience30,31,32,33. The Republic of Maldives, a low-lying island nation formed from carbonate reef-building processes34,35, is particularly vulnerable to these stressors. The country’s economy and survival are closely tied to coral reef health, which supports tourism, fisheries, and natural coastal protection36. Yet, global warming37, rising sea levels38, and intensive coastal modification, especially land reclamation, are putting reefs and land stability at serious risk9.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in North Malé Atoll, where rapid urban development has transformed the landscape. The largest ongoing initiative is the Greater Malé Connectivity Project (GMCP), launched in August 2022 and funded by the Government of India, with AFCONS Infrastructure as the main contractor. This initiative, the largest infrastructure project in Maldivian history, involves the construction of the 6.7 km Thilamalé Bridge connecting Malé, Villimalé, Gulhifalhu, and Thilafushi39. While the GMCP aims to enhance regional connectivity, it has also caused considerable environmental concern. Extensive dredging and coastal modifications are required, and several bridge pillars are being installed directly onto coral reefs, resulting in irreversible habitat loss. Construction-related accidents have also caused additional damage to nearby reefs. In August 2022, a self-elevating platform operated by AFCONS ran aground on the southern reef of Villimalé, causing four large craters. The Maldivian Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) imposed a fine of MVR 69 million (USD 4.5 million), which AFCONS has appealed40. With nearly half of the Maldivian population residing in the Greater Malé Area (Maldives Bureau of Statistics), human pressure has further degraded water quality41, exacerbating stress on coral ecosystems and reducing their resilience20. Coral reefs are highly susceptible to tissue loss and progressive mortality from factors such as predation and diseases. Predators like the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) and the gastropod Drupella spp. can devastate coral cover during outbreaks42,43,44, which are often triggered by nutrient enrichment or predator depletion45,46,47. Corallivorous fishes and coral scrapers (e.g. Chaetodontidae and Scaridae) also contribute to local tissue loss48,49. Coral-associated invertebrates, including vermetid gastropods (Dendropoma spp.), polychaetes (Spirobranchus spp.), and hermit crabs (Paguritta spp.), commonly inhabit the surface or skeleton of coral colonies. These taxa are considered coral ectosymbionts, organisms living externally on corals, with interactions ranging from commensal to deleterious. For instance, Dendropoma spp. can reduce coral growth and survival by up to 80% through mucus-net interference and sediment trapping50. Spirobranchus worms may cause localised tissue irritation or lesions around their tube openings51. Conversely, Paguritta hermit crabs, which feed on suspended particles via antennal filtering, are often reported to have neutral or even beneficial effects by increasing water circulation near coral surfaces52. Coral diseases are also a major cause of mortality, often linked to declining water quality and environmental change53,54. Diagnosing coral disease is complex, as many field-observed lesions are ambiguous, and the causes of tissue loss may be unclear without laboratory analyses55,56. For example, in the Caribbean, the causative agent of Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD) remains unknown57,58, while in the Indo-Pacific, diseases such as white syndromes have multifactorial origins59,60,61. To date, SCTLD has not been reported in the Maldives, though coral diseases of other types (e.g., skeletal-eroding band, white syndromes) have been documented54,62.

In this challenging context, coral relocation and active restoration have emerged as key mitigation strategies to preserve coral biodiversity and cover. Coral relocation involves transferring coral colonies from construction zones to safer locations63. While not mandatory for all projects in the Maldives, it is increasingly used as a biodiversity offset tool64. For the GMCP, coral relocation was mandatory. AFCONS Infrastructure partnered with the local NGO Save the Beach Maldives to transplant colonies from directly impacted reef areas to a recipient site, contributing to a broader restoration initiative in an anthropised environment65. Active coral restoration, which involves transplanting corals from healthy donor reefs to sites with reduced coral cover or structural complexity, is recognised as a key approach to enhance coral recruitment and accelerate recovery66,67,68. Despite this, restoration efforts across local islands in the Maldives remain limited68. In this study, corals were relocated from reefs facing imminent physical destruction to a nearby reef that, while ecologically degraded, offered stable conditions and minimal construction disturbance. Only recently, in October 2024, Save the Beach Maldives launched the first nationwide coral restoration initiative with the endorsement of the Maldivian government.

In this context, the present study aims to assess (i) the health state of the relocated corals over a two-year period (April 2022–March 2024), and (ii) the influence of key biological factors, sea surface temperature, tissue loss, predation, and colonisation of ectosymbionts, on both coral survival and growth.

Materials and methods

Study area and field activities

The Maldives is an archipelago of 26 natural atolls with approximately 1,200 small, low-lying coral islands stretching from north to south over an area of 90,000 km² in the Indian Ocean. Coastal and marine ecosystems dominate the Maldivian environment, with over 99% of the national territory covered by the ocean39. This study was conducted in Villimalé Island (4°10’23.79” N, 73°29’7.29” E) (Fig. 1), the fifth administrative district of Malé and part of the Greater Malé Area. Villimalé is known for its eco-conscious development and for retaining the last three natural beaches within this highly urbanised region65. Despite its eco-conscious initiatives, Villimalé lies within the Greater Malé Area, the most densely populated and developed region of the country. The reef systems surrounding Malé, Villimalé, Gulhifalhu and Thilafushi are subject to chronic anthropogenic pressures, including domestic wastewater discharge, harbour dredging, and land reclamation, which elevate nutrient and sediment loads in nearshore waters69,70,71,72. These cumulative influences have been linked to reduced water quality, macroalgal proliferation, and increased turbidity, posing persistent challenges for coral reef health in these urban reef settings. The relocated corals were transplanted to the north-west side of Villimalé, where a coral restoration project was initiated in 2014 by the local NGO Save the Beach Maldives73. This site was selected based on long-term local knowledge from the NGO, which has been monitoring and maintaining coral frames in Villimalé since 2014. Environmental conditions at the site are consistent with those of other nearby urban reefs, and its close proximity to the community enables regular monitoring and maintenance. The dredging sites selected for coral collection are located on the southern sides of Ghulifalhu and Thilafushi islands, situated approximately 4 km and 3 km, respectively, from the restoration site (Fig. 1). After preliminary monitoring, these sites were selected based on their high coral cover (> 40%) and the imminent threat posed by large-scale construction associated with the Thilamalé Bridge. The relocation followed the “Guideline for Coral Transplantation, Suitability Criteria for Recipient Sites” (Environmental Protection Agency, Republic of Maldives), which included key parameters such as water quality, water condition, substrate availability, connectivity between reefs, and proximity to the donor site74. The relocation took place in April 2022 and it lasted six days, aiming to mitigate the destructive effects of dredging and preserve coral abundance and diversity within the Greater Malé Area. Approximately 1000 corals were relocated during the operation, including both intact colonies and fragments derived from larger colonies. Most corals were attached to metal frames at the restoration site, whereas the larger (> 30 cm), massive colonies were directly positioned on the surrounding reef substrate. A team of trained divers carefully detached colonies from the base of the coral using hammers and cement chisels, minimising the number of strikes to preserve colony branches and tissue integrity. The corals were then placed into metal steel crates (1.5 m × 1.7 m). These crates were lifted to the surface by inflating underwater barrels and subsequently towed by a traditional diving boat (dhoani) to the relocation site in Villimalé. The corals were kept submerged throughout all stages of transport to minimise thermal and handling stress. Upon arrival, the crates were submerged, and the corals were attached to restoration frames using cable ties (Fig. 2). Each frame measured 1 m × 1 m and was constructed from steel rebars, double-coated with coarse sand and resin to prevent rust and provide a textured surface for coral attachment and natural recruitment65,75. The relocation and attachment procedures followed established coral transplantation practices described in64 and consistent with widely adopted reef restoration methodologies76,77. The hexagonal design of the frames enabled the construction of two sturdy beehive-shaped structures, each consisting of 50 frames, one placed on the reef flat at a depth of 1.5–2.2 m, and the other on the reef edge at approximately 3–5 m. A total of 915 corals were attached to the frames. Some colonies broke into 5–10 cm branches during detachment or transport, while others were relocated intact. Most intact colonies were small to medium in size, generally not exceeding 30–40 cm in maximum diameter. All viable fragments were used to maximise the number of corals transplanted and to reduce material loss. No artificial control or maintenance of environmental parameters (e.g., temperature, salinity, or light) was applied during the study. Both donor and recipient reefs are located within the same channel system of the Greater Malé Area and are exposed to similar monsoonal wind regimes, current patterns, and urban reef water-quality conditions, resulting in broadly comparable environmental settings.

This study focuses on 20 frames located on the reef flat, comprising a total of 213 evaluated corals. These 20 frames were selected as a representative subset of the restoration site to ensure consistent temporal monitoring and allow detailed photo-based analyses of individual coral performance. The remaining frames were not included due to time and logistical constraints associated with image acquisition and data processing, but were subject to routine maintenance and visual inspection during field visits.

Field activities included weekly site maintenance, such as removing algal and ascidian overgrowth using brushes, extracting diseased corals to prevent further spread, and checking the stability of corals on the frames, replacing cable ties when necessary. Monitoring was conducted monthly during the first year and bimonthly in the second year.

Study area showing A the location of the Maldives in the Indian Ocean, B North Malé Atoll within the central Maldives, C the Greater Malé Area, including Malé, Villimalé, Gulhifalhu, and Thilafushi, D donor sites on the southern sides of Thilafushi and Gulhifalhu (hammer and chisel icons) and the recipient site on Villimalé (coral icon), and E a detailed outline of Villimalé Island showing the restoration area.

Steps involved in the coral relocation process: a coral colonies are carefully removed from the donor site using hammer and chisel; b collected corals are placed in crates; c barrels are inflated to lift the crates to the surface; d floating crates are tied together; e crates are towed to the recipient site; f corals are attached to pre-positioned hexagonal frames; g, h examples of frames fully stocked with relocated coral colonies.

Data collection and analysis

A total of 213 corals belonging to the genera Acropora and Pocillopora were monitored over a two-year period, from May 2022 to April 2024. To enable balanced analyses, corals were categorised into four groups based on genus and size. The Acropora_fragment group (n = 59) included 30 fragments of Acropora digitifera, 16 of A. gemmifera, 9 of A. monticulosa, 3 of A. samoensis, and 1 of A. cytherea. The Acropora_colony group (n = 53) comprised 25 colonies of A. digitifera, 6 of A. gemmifera, 5 of A. anthocercis, 5 of A. hyacinthus, 3 of A. loripes, 3 of A. nasuta, 2 of A. tenuis, and 1 of A. samoensis. The Pocillopora_fragment group (n = 52) included 30 fragments of Pocillopora meandrina and 22 of P. verrucosa, while the Pocillopora_colony group (n = 49) included 34 colonies of P. meandrina, 10 of P. verrucosa, and 5 of P. eydouxi. Fragments were defined as broken branches resulting from detachment or transport, whereas colonies referred to intact coral colonies before relocation. These categories were therefore based on morphology rather than a specific size threshold. Each coral was photographed monthly during the first year and bimonthly during the second year using an Olympus TG-6 camera, yielding 9,807 images. A metric ruler was included in the frame as a scale reference, and photographs were taken perpendicular to the frame surface at a consistent distance of ~ 50 cm to standardise perspective and scaling accuracy78. Colony size was measured retrospectively from photographs in ImageJ software, recording the maximum linear diameter (i.e., the longest straight-line distance across the colony outline in overhead view). For fragments, this measurement represents linear extension along the largest axis. This one-dimensional metric is a recognised proxy for colony expansion and correlates with overall growth79,80. In addition to size measurements, each coral was assessed from the images by noting the presence or absence of three health-impairment indicators: tissue loss (a-f, Fig. 3), presence of ectosymbionts (g-i, Fig. 3) and predation (l-n, Fig. 3). Each biological factor was recorded monthly using a binary scale (0 = absent, 1 = present). The category “tissue loss” encompassed all cases of progressive coral tissue degradation where the specific cause could not be determined from field images, but which were consistent with signs of disease, microbial infection, or other pathological conditions (e-g, Fig. 3). In addition, coral colouration (including paling and bleaching) was recorded separately as part of the health-state assessment. Monthly coral growth rate (Gr) was calculated as the difference in coral size between two successive time points (T1 and T2), divided by the time between measurements (Gr = (S₂ − S₁)/Δtime), where S₁ and S₂ are coral size measurements (e.g., maximum linear extension) at times T₁ and T₂, respectively. Δtime was expressed in months, corresponding to one-month intervals during the first year and two-month intervals during the second year. Each growth rate was associated with its corresponding standard error (± SE). To assess the influence of sea surface temperature (SST) fluctuations on coral growth and mortality, daily SST data from April 2022 to April 2024 were obtained from the Maldives Meteorological Centre79 and averaged for each month (± SE). Monthly SST values therefore represent the mean of all daily temperature measurements recorded within each month. The SST data originate from the Maldives Meteorological Service’s central monitoring station at Malé/Hulhulé, which records in-situ sea surface temperature for the central Maldives region and is located close to the study site. To account for biological response time, SST in month t was compared with coral growth in month t + 1.

To assess the influence of environmental and biological factors on coral growth and survival, different mixed-effects models accounting for the repeated measures design were used. To evaluate the relationship between SST and coral growth rate, a linear mixed-effects model was applied, with SST and coral type (Acropora_fragment, Acropora_colony, Pocillopora_fragment, and Pocillopora_colony) as fixed effects, and individual coral identity (Coral ID) as a random effect to account for repeated measurements and individual variability81,82. Acropora colonies were included as the reference level for “Coral Type,” allowing direct comparison of growth rates among the four coral groups.

To examine the impact of biological influences (tissue loss, ectosymbionts and predation) on coral growth, were applied a set of linear mixed-effects models, with the presence or absence of each influence (binary) as fixed effects and ‘coral ID’ as a random effect. These models focused on differences in intercept, estimating how the presence of each biological factor means coral growth compared to unaffected individuals. No major bleaching events occurred during the monitoring period, except for a localised event observed in the final month of surveys. Because this episode took place at the end of data collection, it was not included as a categorical variable in the models. However, SST was incorporated as a continuous covariate to capture thermal influences on coral growth. Coral mortality was analysed using Cox proportional hazards models with random effects, evaluating the influence of the biological factors (tissue loss, ectosymbionts and predation) on mortality risk over time83. Each factor was included as a fixed effect, with coral identity (Coral ID) treated as a random effect to account for repeated measures. For the survival analysis, corals that died during the study period were coded as events (1), whereas corals that remained alive at the final survey were treated as right-censored observations (0). No individuals were lost to follow-up. Survival was quantified as the proportion of corals that remained alive at the end of the two-year monitoring period. Comparisons with surrounding natural colonies were not conducted, as the recipient reef was largely lacking Acropora and had only sparse Pocillopora colonies, precluding a meaningful control group. In addition to the statistical modelling, several visualisations were produced to summarise temporal patterns in coral condition. A line chart was used to display monthly coral growth rate alongside SST trends, while bar charts illustrated the temporal patterns of tissue loss, ectosymbiont colonisation, and predation across the monitoring period.

Coral health state was assessed independently from the biological influences, based solely on the visual condition of living tissue and pigmentation. A stacked-area chart illustrates changes in health state over time, using four categories based on the proportion of living tissue remaining and the degree of colouration: (1) 100% living tissue, (2) > 50% living tissue, (3) ≤ 50% living tissue, and (4) pale/bleached65,78. This classification allowed a qualitative assessment of coral vitality and bleaching progression throughout the monitoring period.

Examples of biological factors observed on relocated corals: a–c progressive tissue loss; d–f black patches on Pocillopora colonies, likely associated with bacterial infection and algal proliferation; g presence of the vermetid snail Dendropoma maximum; h colonisation by the hermit crab Paguritta spp.; i presence of the Christmas tree worm Spirobranchus spp.; l predation by the gastropod Drupella spp.; and m, n visible bite marks caused by parrotfish (Scaridae).

Results

Survival and growth rate

After two years, 66% of the relocated corals survived. Pocillopora fragments and both Acropora and Pocillopora colonies showed similarly high survival rates of 71%, 70%, and 72%, respectively, while Acropora fragments had the lowest survival rate at 46%. Acropora fragments (n = 59) also exhibited the lowest average monthly growth rate (0.30 ± 0.02 SE cm/month), whereas Pocillopora colonies (n = 49) had the highest (0.55 ± 0.06 SE cm/month). Acropora colonies (n = 54) and Pocillopora fragments (n = 55) displayed comparable growth rates of 0.47 ± 0.04 cm/month. Growth was assessed using maximum linear extension as a proxy for overall colony expansion. This metric captures net outward growth but does not account for localised partial mortality within colonies. These summary values reflect empirical means (± SE) from the raw data and are provided to describe overall patterns.

Health state

Figure 4 illustrates the health state of corals over the two-year monitoring period, defined by four categories describing the proportion of living tissue and the degree of pigmentation. Acropora fragments exhibited frequent paling and bleaching events; despite these fluctuations, the “100% living tissue” category remained dominant throughout the monitoring period, except in April 2024, when bleaching became the most prevalent condition. Pocillopora fragments showed a progressive decline in health during the second year, culminating in April 2024, where the most frequent conditions were “> 50% living tissue” and “Pale/bleached.” Acropora colonies generally maintained good health until April 2024, when the proportion of bleached colonies noticeably increased. Pocillopora colonies appeared to be the most resistant to the bleaching event in April 2024, although other biological influences contributed to reduced health, as the “> 50% living tissue” category became as frequent as “100% living tissue” in the final month. Visual observations indicated that the loss of living tissue was often associated with dark patches of microbial or algal colonisation on recently exposed skeleton (d-f, Fig. 3). However, no laboratory analyses were undertaken to confirm the aetiology of these lesions.

Environmental and biological drivers of coral growth and survival

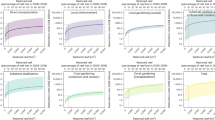

A linear mixed-effects model was fitted to examine the effects of Sea Surface Temperature (SST) and coral type on coral growth rate, while accounting for repeated measurements of individual corals over time. Figure 5 illustrates the growth rates of the coral types (i.e. Acropora fragments and colonies, and Pocillopora fragments and colonies) along with SST over the monitoring period. To model individual variability, a random intercept model was used with random slopes for SST nested within each unique coral (coral ID). The analysis revealed significant effects of both SST and coral type on coral growth (Table 1). Specifically, SST had a significant negative effect on coral growth (Estimate = − 0.097, SE = 0.018, t = − 5.33, p < 0.001), with each 1 °C increase in SST (from the lower range of the dataset, 28.1 °C) corresponding to a decrease of 0.10 cm/month in growth rate. Among coral types, Acropora fragments grew significantly slower than Acropora colonies (Estimate = − 0.216, SE = 0.034, t = − 6.43, p < 0.001), showing a mean reduction of 0.22 cm/month. In contrast, Pocillopora colonies exhibited significantly faster growth than Acropora colonies (Estimate = 0.083, SE = 0.035, t = 2.37, p = 0.018), corresponding to an increase of 0.08 cm/month. Pocillopora fragments displayed a slight, non-significant decline in growth compared to Pocillopora colonies (Estimate = − 0.060, SE = 0.034, t = − 1.80, p = 0.072), indicating only a weak trend toward slower growth. Both colonies and fragments were measured using maximum linear extension along the largest axis, ensuring methodological consistency across coral types.

To further assess how biological factors influenced coral growth, a second linear mixed-effects model was fitted with ectosymbionts, predation, and tissue loss as fixed effects, and coral ID as a random effect (Table 2). Temporal trajectories of tissue loss, ectosymbionts, and predation across the monitoring period are shown in Fig. 6; frequencies slightly varied over time, but did not display a consistent monotonic trend across coral types. Ectosymbiont colonisation significantly reduced coral growth (Estimate = − 0.089, SE = 0.031, t = − 2.88, p = 0.004), with ectosymbiont-colonised corals exhibiting a mean monthly reduction in growth of 0.089 cm compared to non-colonised individuals. This effect was assessed using binary presence/absence records collected at each monitoring interval. In contrast, tissue loss (Estimate = 0.019, SE = 0.027, p = 0.49) and predation (Estimate = − 0.014, SE = 0.044, p = 0.76) showed no significant effect on growth.

A Cox proportional hazards mixed-effects model was then applied to evaluate the influence of environmental and biological factors on coral survival (Table 3). The results revealed several key drivers of coral mortality. Higher SST significantly increased the mortality rate (hazard ratio = 0.44, SE = 0.24, z = − 3.49, p < 0.001), highlighting the dominant role of thermal stress. The presence of tissue loss significantly elevated mortality risk (hazard ratio = 1.59, SE = 0.18, z = 2.57, p = 0.010). In contrast, ectosymbiont colonisation (hazard ratio = 1.35, p = 0.36) and predation (hazard ratio = 1.01, p = 0.98) did not have significant effects. Coral size emerged as an important protective factor: larger individuals had a significantly lower risk of mortality (hazard ratio = 0.82, SE = 0.03, z = − 5.72, p < 0.001). Here, size refers to the numeric maximum linear extension (cm) measured for each individual coral. While some trends in survival among coral types were observed, for instance, Acropora fragments appeared to survive better than colonies (hazard ratio = 0.35, p = 0.12), these differences were not statistically significant, possibly due to high individual variability and limited mortality events.

To test whether the effect of these factors (SST, ectosymbionts, tissue loss, and predation) on mortality risk depended on coral size, interaction terms between size and each factor were included in a follow-up Cox mixed-effects model (Table 4). This analysis revealed a significant interaction between size and predation: predation had a stronger effect on larger corals (hazard ratio = 1.14, SE = 0.046, z = 2.90, p = 0.0037). However, this result should be interpreted cautiously due to challenges in recognising predation marks on smaller fragments, which may be eaten fully in a single predation event. Interactions between size and SST (p = 0.75), ectosymbiont colonisation (p = 0.92), and tissue loss (p = 0.13) were not statistically significant, indicating that the mortality risks from these biological factors were not size-dependent.

Frequency (%) of corals exhibiting different health states across the two-year monitoring period. The categories include 100% living tissue (blue), > 50% living tissue (pink), ≤ 50% living tissue (yellow), and pale/bleached (grey). The data is presented for Acropora fragments, Pocillopora fragments, Acropora colonies, and Pocillopora colonies. The empty months represent missing data.

Average monthly growth trends (cm/month) for Acropora fragments (green), Acropora colonies (pink), Pocillopora fragments (red), and Pocillopora colonies (purple), along with sea surface temperature averages (dashed black line). Error bars represent ± SE. Dashed segments in the growth lines indicate months with missing data.

Cumulative stacked chart showing the temporal trends in the percentage frequency (%) of biological factors: tissue loss (grey), ectosymbionts (orange), and predation (purple), in Acropora fragments, Pocillopora fragments, Acropora colonies, and Pocillopora colonies. The empty months represent missing data.

Discussion

In the Maldives, coral relocation is increasingly used as a mitigation strategy in response to the rapid pace of coastal modification. While this approach offers a way to preserve coral biodiversity and support reef functioning, its success remains highly context-dependent84. Scientific best practices recommend aligning the scale of relocation with the scale of degradation85,86, but in many real-world scenarios, practical limitations restrict what is feasible. For the Thilamalé Link project, the intervention was modest in scale, constrained by a limited budget and a tight timeline: surveys and relocation had to be completed within two weeks, with 100 1 × 1 m frames deployed, and long-term monitoring was left solely to the local NGO Save the Beach Maldives73, without external funding.

Villimalé Island was selected as the relocation site due to its environmental conditions closely matching those of the donor sites, including exposure to poor water quality and significant anthropogenic pressure from nearby urban centres such as Malé and Thilafushi87,88. This ecological similarity, combined with its proximity, logistical practicality, and the presence of a successful ongoing coral restoration project led by Save the Beach Maldives65, made Villimalé a strategic choice. Importantly, Villimalé offered an opportunity to strengthen restoration efforts through direct community engagement. Members of Save the Beach Maldives and local volunteers collaborated throughout the relocation process, assisting in the attachment of corals to the restoration frames. Among the participants were members of the Muhyiddin School scout group, who joined the field team during the attachment phase. Having been active on the island for more than a decade, Save the Beach Maldives has trained many community members in coral restoration practices; this initiative brought them together once again to contribute to the rehabilitation of their house reef. Nearly half of the Maldivian population resides in the Greater Malé Area89, and using Villimalé as a visible and accessible restoration hub supports education, outreach, and long-term stewardship, critical components of conservation success.

After two years, the survival of the 213 relocated corals was relatively high (66%, Fig. 7), especially given the challenging context. Although this is slightly below the 70–90% survival range often reported in the literature90,91, it exceeds the 60% threshold used to define acceptable outcomes in similar projects91. While the scale of the intervention was smaller than that of large-scale restoration initiatives involving thousands of colonies (e.g.90, it aligns with other targeted efforts such as the Hayman Island relocation in the Great Barrier Reef91.

This pilot phase represents the initial step of a broader coral restoration programme aimed at rehabilitating the Villimalé west reef through multiple methodologies. Although small-scale trials such as this may limit the generality of conclusions, they provide a valuable proof of concept that can guide larger implementations. The approach used in this study is easily replicable and scalable, as it relies on locally available and low-cost materials (approximately 40 USD per frame, including both materials and labour for assembling the hexagons). However, upscaling is constrained not only by funding for additional frames and the availability of donor colonies or corals of opportunity, but also by logistical costs such as hiring boats to reach distant donor reefs. Furthermore, site selection remains a key determinant of success, as frame-based restoration should preferably target areas dominated by rubble substrates rather than sandy or steep bottoms. Thus, while this protocol can be extended to other islands, its transferability ultimately depends on local geomorphological conditions and resource availability. In sites with different environmental or morphological settings, alternative techniques such as metal meshes, plugs, or coral clips could be considered.

Coral health outcomes varied by genus and by the influencing biological factor. Acropora colonies generally remained in good condition but proved highly sensitive to elevated SSTs. During the marine heatwave recorded in March-April 2024, when SSTs reached 29.98 ± 0.02 °C and persisted for the entire month of April, Acropora bleached heavily, particularly in the shallows where they had been transplanted.

This pattern accords with regional observations from the 2016 mass-bleaching in the central Maldives, where tabular and branching Acropora suffered near-complete loss at shallow depths while massive Porites and some Pocillopora fared comparatively better, albeit with partial damage and reduced size classes92,93. A study of bleaching severity in Maldivian reefs further found that species identity and shallow depth strongly predicted high bleaching incidence, with up to 83% of colonies affected at 3–5 m in susceptible genera94. Together, these findings support the management implication that, when possible, Acropora should be placed slightly deeper (~ 6–7 m) to reduce thermal exposure, acknowledging potential trade-offs with light and growth95. By contrast, Pocillopora was more resistant to bleaching but exhibited chronic tissue loss over time without major acute bleaching, indicating a slower, cumulative decline pathway rather than immediate collapse. The coexistence of acute (bleaching) and chronic (tissue loss, bacterial infections, or sediment stress) mechanisms is rarely documented in the restoration literature and therefore provides additional insight into genus-specific responses.

These outcomes underscore the challenges of relocating corals into suboptimal environments, even when donor and recipient sites are environmentally similar. Nevertheless, the diversity of stress responses observed among coral genera reinforces the value of including a mix of species in relocation efforts. A more taxonomically diverse assemblage can buffer against specific disturbances and promote greater ecological stability96. Larger fragments and colonies exhibited greater survival, confirming prior findings that colony size is a key determinant of post-transplantation success90,95. While many large-scale restoration projects favour small (5–10 cm) fragments for scalability, our results support using larger fragments (≥ 15 cm) when feasible, particularly in ecologically degraded or high-stress environments. Tissue loss emerged as the most important predictor of mortality across all coral types, far outweighing the effects of predation or ectosymbiont colonisation. Although it was not always possible to determine the specific cause of tissue loss, the cumulative stress of relocation, combined with chronic environmental pressures, likely played a role in increasing coral susceptibility to disease61. Chronic local stressors such as sedimentation, reduced water quality, and nutrient enrichment, common in highly anthropised reefs, can exacerbate coral disease prevalence and tissue necrosis97. These local disturbances lower light penetration, promote microbial proliferation, and compromise coral immunity, thereby magnifying the effects of physiological stress and relocation on colony health98,99.

Growth rates declined sharply following the thermal anomaly in March-April 2024, especially among Acropora fragments. SST anomalies appear to impact not only survival but also recovery potential, slowing growth and delaying the re-establishment of healthy tissue. Because growth was assessed using maximum linear extension, the metric reflects overall colony expansion rather than changes in living tissue area. As such, localised partial mortality within colonies may not be fully captured, which could influence the interpretation of short-term growth responses during stress events. Ectosymbionts, although not a strong predictor of mortality, were associated with reduced growth in both genera, particularly among corals colonised by the vermetid worm Dendropoma maximum. These mucus-net-producing gastropods can inhibit feeding and energy acquisition100 and were observed primarily on Pocillopora. Other common ectosymbionts included Paguritta spp. and Spirobranchus spp., though their impact on coral health appeared minimal or null. The potential role of D. maximum as a reef health indicator101 warrants further investigation in the region. Overall, Pocillopora exhibited faster linear growth than Acropora, suggesting greater short-term resilience under chronic stress. However, faster growth does not necessarily equate to sustained recovery, especially in the face of repeated disturbances. The dominance of these fast-growing genera in the donor sites reflects their natural prevalence in Maldivian reefs93. While both remain highly sensitive to thermal stress, they are also known for their capacity for rapid post-bleaching regrowth, particularly when local conditions are favourable84. Their ecological importance lies in their key role in maintaining reef structural complexity and habitat provision. Although direct measurements of water quality (e.g., sedimentation, turbidity, nutrient concentrations) were not undertaken in this study, the surrounding reef systems of the Greater Malé Area are documented to experience elevated sedimentation (e.g., around the Gulhifalhu reclamation site) and regular discharge of untreated or partially treated domestic effluent into nearshore waters71,72. These chronic pressure sources likely compound the stress from thermal anomalies and other acute disturbances, creating cumulative effects that hinder coral recovery and resilience. In such contexts, maximising genetic and taxonomic diversity and mitigating local stressors, such as coastal modification or nutrient loading, could help enhance resilience and recovery potential in the face of inevitable climate-driven events.

In the context of the Maldives’ expanding coastal infrastructure, coral relocation is likely to remain a common practice. Yet, its success will depend not just on techniques but on thoughtful site selection, species choice, adequate monitoring, and integration with broader reef management strategies. When possible, and depending on reclamation schedules, relocation activities should be planned outside the typical bleaching alert season. Conducting transplantation around August-September could provide sufficient time for relocated corals to acclimate, heal, and strengthen before the onset of peak thermal stress. Despite being implemented in a heavily altered environment, this relocation effort demonstrates that with targeted planning and long-term commitment, even small-scale interventions can support coral survival and growth. As discussed above, the method’s relatively low material and labour costs make its replication economically feasible, offering a practical foundation for scaling up coral restoration where funding and logistical challenges are effectively managed. Ensuring the continued protection of relocated colonies and investing in the science and practice of coral relocation will be crucial in maintaining reef resilience in an era of rapid change.

Temporal progression of three relocated coral frames, each photographed at three time points: May 2022 (a, d, g), September 2023 (b, e, h), and April 2024 (c, f, i). Rows correspond to individual frames (Frame 1: a–c; Frame 2: d–f; Frame 3: g–i). Early signs of bleaching can be observed in the final column (c, f, i), captured during the last monitoring survey.

Data availability

Data are available on request to the corresponding author due to restrictions and ownership of the NGO Save the Beach Maldives.

References

Spalding, M. D., Ravilious, C. & Green, E. P. World Atlas of Coral Reefs (University of California Press, 2001).

Beger, M. & Possingham, H. Environmental factors that influence the distribution of coral reef fishes: modeling occurrence data for broad-scale conservation and management. Mar. Ecol. Prog Ser. 361, 1–13 (2008).

Roberts, C. M. et al. Marine biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science 295, 1280–1284 (2002).

Hoeksema, B. W. & van der Meij, S. E. T. Editorial: corals, reefs and marine biodiversity. Mar. Biodivers. 43, 1–6 (2013).

Ferrario, F. et al. The effectiveness of coral reefs for coastal hazard risk reduction and adaptation. Nat. Commun. 5, 3794 (2014).

Cinner, J. Coral reef livelihoods. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 7, 65–71 (2014).

Cesar, H. S. J. Coral reefs: their functions, threats and economic value (2005).

Nepote, E. et al. Pattern and intensity of human impact on coral reefs depend on depth along the reef profile and on the descriptor adopted. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 178, 86–91 (2016).

Pancrazi, I., Ahmed, H., Cerrano, C. & Montefalcone, M. Synergic effect of global thermal anomalies and local dredging activities on coral reefs of the Maldives. Mar. Pollut Bull. 160, 111585 (2020).

Valentine, J. F. & Heck, K. L. Perspective review of the impacts of overfishing on coral reef food web linkages. Coral Reefs. 24, 209–213 (2005).

Taiminen, S. The negative impacts of overtourism on tourism destination from environmental and socio-cultural perspectives. Unpublished thesis (2018).

Akhtar, R. et al. Impact of plastic waste on the coral reefs: an overview. In Impact of Plastic Waste on the Marine Biota, 239–256 (2022).

Jones, R. et al. Assessing the impacts of sediments from dredging on corals. Mar. Pollut Bull. 102, 9–29 (2016).

Miller, M. W. et al. Detecting sedimentation impacts to coral reefs resulting from dredging the Port of Miami, Florida USA. PeerJ 4, e2711 (2016).

Moberg, F. & Folke, C. Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecol. Econ. 29, 215–233 (1999).

Montefalcone, M., Morri, C. & Bianchi, C. N. Influence of local pressures on Maldivian coral reef resilience following repeated bleaching events, and recovery perspectives. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 587 (2020).

Mellin, C. et al. Cumulative risk of future bleaching for the world’s coral reefs. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn9660 (2024).

Glynn, P. W. D’Croz, L. Experimental evidence for high temperature stress as the cause of El Niño-coincident coral mortality. Coral Reefs. 8, 181–191 (1990).

Dijkstra, H. A. The ENSO phenomenon: theory and mechanisms. Adv. Geosci. 6, 3–15 (2006).

Montefalcone, M., Morri, C. & Bianchi, C. N. Long-term change in bioconstruction potential of Maldivian coral reefs following extreme climate anomalies. Glob Chang. Biol. 24, 5629–5641 (2018).

Claar, D. C. et al. Global patterns and impacts of El Niño events on coral reefs: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 13, e0190957 (2018).

Bertaud, A. A rare case of land scarcity: the issue of urban land in the Maldives. Mimeo (accessed 11 Jan 2010). http://alainbertaud.com/wpcontent/uploads/2013/06/AB_Maldives_Land.pdf (2002).

Heery, E. C. et al. Urban coral reefs: degradation and resilience of hard coral assemblages in coastal cities of East and Southeast Asia. Mar. Pollut Bull. 135, 654–681 (2018).

Bisaro, A., de Bel, M., Hinkel, J., Kok, S. & Bouwer, L. M. Leveraging public adaptation finance through urban land reclamation: cases from Germany, the Netherlands and the Maldives. Clim. Change. 160, 671–689 (2020).

Kim, N. H. et al. Effects of seasonal variations on sediment-plume streaks from dredging operations. Mar. Pollut Bull. 129, 26–34 (2018).

de Wit, L., Talmon, A. M. & Rhee, C. V. 3D CFD simulation of trailing Suction hopper dredger plume mixing: a parameter study of near field conditions influencing the suspended sediment source flux. Mar. Pollut Bull. 88, 47–61 (2014).

Freudenthal, H. D. Symbiodinium gen. nov. And symbiodinium microadriaticum sp. nov., a zooxanthella: taxonomy, life cycle, And morphology. J. Protozool. 9, 45–52 (1962).

Lesser, M. P. Experimental biology of coral reef ecosystems. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 300, 217–252 (2004).

Marshall, S. M. & Orr, A. P. Sedimentation on low Isles reef and its relation to coral growth. Sci. Rep. Great Barrier Reef. Exped. 1, 94–133 (1931).

Erftemeijer, P. L., Riegl, B., Hoeksema, B. W. & Todd, P. A. Environmental impacts of dredging and other sediment disturbances on corals: a review. Mar. Pollut Bull. 64, 1737–1765 (2012).

Todd, P. A. Morphological plasticity in scleractinian corals. Biol. Rev. 83, 315–337 (2008).

Rogers, C. S. Responses of coral reefs and reef organisms to sedimentation. Mar. Ecol. Prog Ser. 62, 185–202 (1990).

Jones, R., Fisher, R., Stark, C. & Ridd, P. Temporal patterns in seawater quality from dredging in tropical environments. PLoS ONE. 10, e0137112 (2015).

Morgan, K. M. & Kench, P. S. Reef to Island sediment connections on a Maldivian carbonate platform: using benthic ecology and biosedimentary depositional facies to examine Island-building potential. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 41, 1815–1825 (2016).

Dhunya, A., Huang, Q. & Aslam, A. Coastal habitats of maldives: Status, trends, threats, and potential conservation strategies. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 8, 47–62 (2017).

Giampiccoli, A., Muhsin, B. A. & Mtapuri, O. Community-based tourism in the case of the Maldives. Geoj. Tour Geosites. 29, 428–439 (2020).

The World Bank IBRD-IDA. Maldives-Wetland Conservation and Coral Reef Monitoring for Adaptation to Climate Change Project (accessed 12 Apr 2025). https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documentsreports/documentdetail/568581468050704853.

Wadey, M., Brown, S., Nicholls, R. J. & Haigh, I. Coastal flooding in the maldives: an assessment of historic events and their implications. Nat. Hazards. 89, 131–159 (2017).

Atoll Times. Thilamale bridge crane collapses (accessed 25 Jun 2025). https://atolltimes.mv/post/news/1422.

The Press. AFCONS bridge platform crashes on Villimale reef, EPA investigates. (accessed 28 May 2025). https://en.thepress.mv/15117.

Munavvar, R. Apr. Tragedy of the Maldives. Of Fleeting Paradise, Enduring World Power and a Great Sense of Responsibility. The Edition, Climate Change. (accessed 12 Apr. 2025). https://edition.mv/comic_of_the_day/12528.

Pratchett, M. S. et al. Thirty years of research on crown-of-thorns starfish (1986–2016): scientific advances and emerging opportunities. Diversity 9, 41 (2017).

Lei, X. et al. Spatial variability In the abundance and prey selection of the corallivorous snail drupella spp. In southeastern Hainan Island, China. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 990113 (2022).

Motti, C. A., Cummins, S. F. & Hall, M. R. A review of the giant triton (Charonia tritonis), from exploitation to coral reef protector?. Diversity 14, 961 (2022).

Bessey, C. et al. Outbreak densities of the coral predator drupella and in situ Acropora growth rates on Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia. Coral Reefs. 37, 985–993 (2018).

Galli, P., Montano, S., Seveso, D. & Maggioni, D. Coral reef biodiversity of the Maldives. In Atoll Maldives: Nissol. Geogr. 196 (2021).

Uthicke, S., Pratchett, M. S., Bronstein, O., Alvarado, J. J. & Wörheide, G. The crown-of-thorns seastar species complex: knowledge on the biology and ecology of five corallivorous Acanthaster species. Mar. Biol. 171, 32 (2024).

Gregson, M. A., Pratchett, M. S., Berumen, M. L. & Goodman, B. A. Relationships between butterflyfish (Chaetodontidae) feeding rates and coral consumption on the great barrier reef. Coral Reefs. 27, 583–591 (2008).

El Rahimi, S. A., Hendra, E., Isdianto, A. & Luthfi, O. M. Feeding preference of herbivorous fish: family Scaridae. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 869, 012004 (2021).

Shima, J. S., Osenberg, C. W. & Stier, A. C. The vermetid gastropod Dendropoma maximum reduces coral growth and survival. Biol. Lett. 6, 815–818 (2010).

Hoeksema, B. W., Wels, D., van der Schoot, R. J. & ten Hove, H. A. Coral injuries caused by Spirobranchus opercula with and without epibiotic turf algae at Curaçao. Mar. Biol. 166, 60 (2019).

Patton, W. K. Distribution and ecology of animals associated with branching corals (Acropora spp.) from the great barrier Reef, Australia. Bull. Mar. Sci. 55, 193–211 (1994).

Miller, A. W. & Richardson, L. L. Emerging coral diseases: A temperature-driven process? Mar. Ecol. 36, 278–291 (2014).

Montano, S., Strona, G., Seveso, D., Maggioni, D. & Galli, P. Widespread occurrence of coral diseases in the central Maldives. Mar. Freshw. Res. 67, 1253–1262 (2015).

Cervino, J. et al. The Vibrio core group induces yellow band disease in Caribbean and Indo-Pacific reef-building corals. J. Appl. Microbiol. 105, 1658–1671 (2008).

Work, T. M. & Aeby, G. S. Pathology of tissue loss (white syndrome) in Acropora sp. corals from the central Pacific. J. Invertebr Pathol. 107, 127–131 (2011).

Aeby, G. S. et al. Pathogenesis of a tissue loss disease affecting multiple species of corals along the Florida reef tract. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 678 (2019).

Papke, E. et al. Stony coral tissue loss disease: a review of emergence, impacts, etiology, diagnostics, and intervention. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1321271 (2024).

Ainsworth, T., Kvennefors, E., Blackall, L., Fine, M. & Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Disease and cell death in white syndrome of Acroporid corals on the great barrier reef. Mar. Biol. 151, 19–29 (2007).

Sussman, M., Willis, B. L., Victor, S. & Bourne, D. G. Coral pathogens identified for white syndrome (WS) epizootics in the Indo-Pacific. PLoS ONE. 3, e2393 (2008).

Rodríguez-Villalobos, J. C., Work, T. M., Calderon-Aguilera, L. E., Reyes-Bonilla, H. & Hernández, L. Explained and unexplained tissue loss in corals from the tropical Eastern Pacific. Dis. Aquat. Org. 116, 121–131 (2015).

Montano, S., Strona, G., Seveso, D. & Galli, P. First report of coral diseases in the Republic of Maldives. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 101 (2), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.3354/dao02515 (2012).

ter Hofstede, T., Finney, C., Miller, A., van Koningsveld, M. & Smolders, T. Monitoring and evaluation of coral transplantation to mitigate the impact of dredging works. In Proc. 13th Int. Coral Reef Symp., 330–341 (2016).

Environmental Protection Agency. Republic of Maldives. The guideline for coral transplantation–suitability criteria for recipient sites. https://en.epa.gov.mv/

Pancrazi, I., Feairheller, K., Ahmed, H., Di Napoli, C. & Montefalcone, M. Active coral restoration to preserve the biodiversity of a highly impacted reef in the Maldives. Diversity 15, 14 (2023).

Jaap, W. C. Coral reef restoration. Ecol. Eng. 15, 345–364 (2000).

Bowden-Kerby, A. Aug. Coral transplantation and restocking to accelerate the recovery of coral reef habitats and fisheries resources within no-take marine protected areas. In ITMEMS, AquaDocs.org: Manila, Philippines. (accessed 12 Aug. 2023). https://aquadocs.org/handle/1834/849 (2003).

Dehnert, I., Galli, P. & Montano, S. Ecological impacts of coral gardening outplanting in the Maldives. Restor. Ecol. 31, e13783 (2022).

CDE Consulting. Sedimentation rate monitoring report: Gulhifalhu Port Development Project (Phase I). Ministry of National Planning, Housing and Infrastructure, Republic of Maldives. (2021). https://www.gulhifalhu.mv/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Sedimentation-Report-20.pdf

United Nations Maldives. UN expert: Maldives stuck between a rock and a hard place on climate change and development. UN Maldives Newsroom, April 2024. https://maldives.un.org/en/267078-un-expert-maldives-stuck-between-rock-and-hard-place-climate-change-issue

Painter, S. C. et al. Anthropogenic nitrogen pollution threats and challenges to the health of South Asian coral reefs. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1187804 (2023).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Sewage and wastewater: Consequences for the environment of coral reefs and related ecosystems. In The State of the Marine Environment: Regional Assessments. (1998). https://www.fao.org/4/x5627e/x5627e0a.htm

Save the Beach Maldives. (accessed 25 June 2025). https://www.savethebeachmaldives.org.

Environmental Protection Agency. Republic of Maldives. (accessed 25 June 2025). https://en.epa.gov.mv.

Williams, S. L. et al. Large-scale coral reef rehabilitation after blast fishing in Indonesia. Restor. Ecol. 27, 447–456 (2019).

Edwards, A. J. & Gomez, E. D. Reef restoration concepts & guidelines: making sensible management choices in the face of uncertainty. Coral Reef Targeted Research & Capacity Building for Management Programme (2007).

Boström-Einarsson, L. et al. Coral restoration – A systematic review of current methods, successes, failures and future directions. PLoS ONE. 15, e0226631 (2020).

Dehnert, I. et al. Exploring the performance of mid-water lagoon nurseries for coral restoration in the Maldives. Restor. Ecol. 30, e13600 (2021).

Million, W. C., O’Donnell, S., Bartels, E. & Kenkel, C. D. Colony-level 3D photogrammetry reveals that total linear extension and initial growth do not scale with complex morphological growth in the branching coral, acropora cervicornis. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 646475 (2021).

Maldives Meteorological Service. (accessed 25 May 2025). https://www.meteorology.gov.mv/.

Gelman, A. & Hill, J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Zuur, A. F., Ieno, E. N., Walker, N. J., Saveliev, A. A. & Smith, G. M. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R (Springer, 2009).

Therneau, T. M. coxme: Mixed Effects Cox Models. R package version 2.2–18 (2023). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=coxme

Seraphim, M., Collins, E. & Burt, J. A. Coral relocation in the Arabian gulf: Benefits, risks and best-practices recommendations for practitioners and decision-makers. Abu Dhabi Ports Group (2024).

Doyle, M. W. & Yates, A. J. Stream ecosystem service markets under no-net-loss regulation. Ecol. Econ. 69, 820–827 (2010).

Schulp, C. J., Van Teeffelen, A. J., Tucker, G. & Verburg, P. H. A quantitative assessment of policy options for no net loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services in the European union. Land. Use Policy. 57, 151–163 (2016).

Majeedha, M. State of the Environment 2016. Ministry of Environment, Climate Change and Technology, Republic of Maldives (accessed 12 Aug 2023). https://www.environment.gov.mv/v2/en/download/4270 (2017).

Peterson, C. Assessment of solid waste management practices and its vulnerability to climate risks in Maldives tourism sector. Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture, Malé, Republic of Maldives (2013). https://archive.tourism.gov.mv/downloads/tap/2014/Solid_Waste.pdf

Maldives Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of National Planning Housing & Infrastructure. May (accessed 24 May 2025). https://statisticsmaldives.gov.mv/census-in-2022/.

Kotb, M. M. Coral translocation and farming as mitigation and conservation measures for coastal development in the red sea: Aqaba case study, Jordan. Environ. Earth Sci. 75, 5304 (2016).

Smith, A. K. et al. Effectiveness of coral (Bilbunna) relocation as a mitigation strategy for pipeline construction at Hayman Island, great barrier reef. Ecol. Manag Restor. 25, 21–31 (2024).

Ball, E. E., Hayward, D. C., Bridge, T. C. & Miller, D. J. Acropora: the most-studied coral genus. In Handbook of Marine Model Organisms in Experimental Biology 173–193 (CRC, 2021).

Pisapia, C., Burn, D. & Pratchett, M. S. Changes in the population and community structure of corals during recent disturbances (February 2016–October 2017) on Maldivian coral reefs. Sci. Rep. 9, 8402 (2019).

Muir, P. R., Marshall, P. A., Abdulla, A. & Aguirre, J. D. Species identity and depth predict bleaching severity in reef-building corals: shall the deep inherit the reef?. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 284(1864), 20171551 (2017).

Migliaccio, O. Optimizing coral farming: A comparative analysis of nursery designs for acropora aspera, acropora muricata, and Montipora digitata in Anantara Lagoon, Maldives. Int. J. Mar. Sci. 14, 295–305 (2024).

Drury, C. & Lirman, D. Making biodiversity work for coral reef restoration. Biodiversity 18, 23–25 (2017).

Montano, S., Giorgi, A., Monti, M., Seveso, D. & Galli, P. Spatial variability in distribution and prevalence of skeletal eroding band and brown band disease in Faafu Atoll, Maldives. Biodivers. Conserv. 25, 1625–1636 (2016).

Vega Thurber, R. L. et al. Chronic nutrient enrichment increases prevalence and severity of coral disease and bleaching. Glob Change Biol. 20, 544–554 (2014).

Bourne, D. G., Morrow, K. M. & Webster, N. S. Insights into the coral microbiome: underpinning the health and resilience of reef ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 70, 317–340 (2016).

Zvuloni, A., Armoza-Zvuloni, R. & Loya, Y. Structural deformation of branching corals associated with the vermetid gastropod Dendropoma maxima. Mar. Ecol. Prog Ser. 363, 103–108 (2008).

Scaps, P. & Denis, V. Can organisms associated with live scleractinian corals be used as indicators of coral reef status? Atoll Res. Bull (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Maldivian NGO Save the Beach Maldives for its invaluable support throughout this research, which enabled the continuity of the study over two years. We are especially grateful to all participants involved in the field activities, whose efforts in coral relocation, site maintenance, and voluntary data collection were fundamental to the success of this project. We also extend our sincere thanks to Afcons Infrastructure Limited for permitting the coral relocation prior to the commencement of their operations and for their interest and support in our work.

Funding

Coral relocation activities were funded by Afcons Infrastructure Limited. The restoration project was partially supported by the GHOST NETS project (Ministry of Environment and Energy Security, PNRR Mission 2, ISPRA, Italy).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, I.P. and D.T.; methodology, I.P. and H.A.; software, M.M. and I.P.; validation, M.M., I.P. and H.A.; formal analysis, I.P., D.T., V.A.; investigation, I.P., H.A; resources, H.A., I.P. and M.M.; data curation, I.P., D.T. and V.A.; writing—original draft preparation, I.P. and D.T.; writing—review and editing, M.M., I.P. and V.A.; visualization, I.P. and D.T.; supervision, M.M. and I.P.; project administration, I.P. and H.A.; funding acquisition, H.A. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pancrazi, I., Tritini, D., Ahmed, H. et al. Coral relocation supports survival and growth in an urban reef of the Maldives. Sci Rep 15, 45153 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33671-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33671-7