Abstract

Decreased Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio (ACR) is associated with poor prognosis in a variety of diseases, and little is known about the relationship between ACR and acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between ACR and short-term prognosis in patients with ACLF and to assess the role of ACR as a short-term poor prognosticator in these patients. Our retrospective data were collected from hospitalized ACLF patients. Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) and Kaplan–Meier survival analyses were used to assess the efficacy of prognostic assessment of ACR, and univariate and multivariate logistic regression were used to characterize the relationship between ACR and independent risk factors for short-term mortality, and subgroup analyses were used to obtain further reliable evidence. A total of 240 patients with ACLF were included in the study. The 28-day mortality rate was 25% (60/240). Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis showed that the area under the curve (AUC) for ACR, albumin (ALB) and creatinine (Cr) were 0.797 (95% CI 0.730–0.861, p < 0.001), 0.672 (95% CI 0.601–0.743, P < 0.001), 0.759 (95% CI 0.688–0.829, P < 0.001), and the results of the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis similarly showed that the ACR level was significantly negatively associated with ACLF mortality (P < 0.0001). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that increased ACR was associated with lower mortality in patients (OR 0.10; 95% CI 0.02–0.35, P < 0.001), subgroup analyses led to the same conclusion. Low levels of ACR were significantly associated with patients in ACLF, and this study was the first to characterize the relationship between ACR and 28-day mortality in patients with ACLF, which will help clinicians accurately identify early disease progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic liver diseases (CLD) are the 14th most common cause of death globally, and it encompasses advanced stages of various liver diseases including hepatitis B and C infections, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), alcohol consumption, and autoimmune disorders1,2, which have a significant impact on mortality and disability-adjusted life years1,3. According to the latest reports, a total of 1,472,011 deaths from cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases were reported globally in 2019, this is a 45.32% increase from the 1,012,975 deaths reported in 19904, which undoubtedly places a heavy burden on patients and healthcare systems.and place a heavy burden on patients and healthcare systems. Most patients with CLD remain stable and when acute liver injury occurs on this basis, it progresses to acute decompensation or even organ failure, the latter being defined as acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). ACLF is typically characterized by rapid progression, the need for multi-organ supportive therapy, and short- and intermediate-term mortality rates as high as 50–90%. Patients with ACLF have a 15 times higher 28-day mortality rate compared to patients with other CLD5,6,7.

Hypoalbuminemia has long been recognized as one of the features of CLD caused by a variety of events, such as decreased hepatocyte synthesis, shortened total half-life due to increased catabolism, and increased total plasma volume leading to dilution8, and studies have also demonstrated that albumin levels correlate with the prognosis of ACLF9,10,11. Renal failure in ACLF patients is considered a complex and challenging disease associated with an ominous prognosis. In addition, the kidney is one of the most common extrahepatic organs in patients with ACLF, changes in serum creatinine and urine output are used to define and stage acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients with cirrhosis according to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes AKI criteria, and creatinine is also an independent predictor of mortality in ACLF6,12. In fact, serum albumin levels are also influenced by renal function,as damaged kidneys can secrete albumin13, and the serum albumin to serum creatinine ratio (ACR) is now a new biomarker that may be a better indicator than serum albumin or creatinine alone. However, no study has reported the correlation between ACR and ACLF prognosis. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the association between serum ACR and short-term prognosis of ACLF.

Materials and methods

Study population

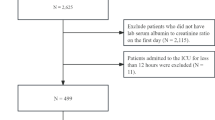

A total of 373 patients with ACLF hospitalized in the Department of Infectious Diseases of Union Hospital of Huazhong University of Science and Technology from May 2020 to August 2022 were collected. ACLFwas defined according to the updated consensus recommendations of the consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver (APASL)7. The inclusion criteria were: age 18–80 years old; meeting the diagnostic criteria for ACLF. The exclusion criteria were missing data; patients with combined hepatocellular carcinoma or other malignant tumors; severe chronic extrahepatic diseases; pregnancy status; undergoing liver transplantation; and loss of follow-up. A total of 294 patients were included in the follow-up after screening by the inclusion criteria, and the 28-day survival of the patients was clarified through follow-up, and finally 240 patients were included in the study. The specific flow chart is as follows (Fig. 1). Each participant provided written informed consent, the research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Union Hospital, Tongji medical college of Huazhong university of science and technology. The study procedures adhered to the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collection

We collected clinical data from the first examination of all enrolled patients, including clinical manifestations and laboratory measurements. Adverse clinical outcome was defined as patient death.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed variables were compared using the Student’s t-test and expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Variables that were not normally distributed were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test and expressed as median interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher exact test and expressed as counts and percentages. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify potential associations between serum ACR and 28-day adverse outcomes. Stepwise regression was used to construct logistic regression models I–IV. Model I was unadjusted. Model II was adjusted for age and sex. Model III was adjusted for model II plus international normalized ratio (INR), Natrium (Na). Model IV was adjusted for model III plus bleeding, cirrhosis, ascites, and infection. DeLong’s test for area under the ROC curve for different indicators. Draw a clinical decision curve analysis (DCA) to analyze the clinical application value of indicators. Survival rates of patients with different serum ACR levels were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.3.0).

Results

Clinical characteristics and adverse outcomes of ACLF patients with different ACR levels

A total of 240 patients were enrolled, of which 202 (84.2%) were males and 38 (15.8%) were females, and 140 (58.3%) patients with cirrhosis, Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection was the main etiology (85%). A total of 60 patients had an unfavorable outcome, with a 28-day mortality rate of 25%. The baseline characteristics of serum ACR quartile subgroups was showed in Table 1, which revealed that quartile 1(Q1, ACR < 0.388), Q2(0.388 ≤ ACR < 0.460), Q3(0.460 ≤ ACR < 0.540), Q4 (ACR ≥ 0.540) mortality rates were 53%,26%,15%,5.1% respectively, suggesting that serum ACR level was significantly negatively correlated with adverse outcome of ACLF (P < 0.001). In addition, the Child–Pugh (CP) scores and End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores, and the incidence of infection and ascites decreased with increasing serum ACR (P < 0.05).

Predictive ability of ACR for adverse outcomes in ACLF patients

In order to evaluate the prognostic value of serum ACR, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and ROC curve analysis were performed. ROC curve analysis of serum ACR, ALB and Cr showed that their areas under the curve (AUC) were 0.797 (95% CI 0.730–0.861, P < 0.001), 0.672 (95% CI 0.601–0.743, P < 0.001), 0.759 (95% CI 0.688–0.829, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A), which suggesting that serum ACR had a good predictive ability for poor prognosis of ACLF and was superior to the predictive ability of ALB and Cr (P < 0.05). In order to predict the short-term prognosis of patients with ACLF, the AUC corresponding to existing models of CP, MELD, and iMELD were 0.774, 0.784, and 0.792 respectively, which were slightly inferior to serum ACR (Fig. 2B), but there is no statistical difference. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that the level of serum ACR was significantly negatively correlated with the mortality rate of ACLF (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3).

Role of ACR as an independent risk factor for adverse outcomes in ACLF patients

We further evaluated the role of serum ACR as an independent risk factor for adverse outcomes in ACLF patients. In model I–IV, we progressively controlled for other risk factors such as age, sex, Na, INR, cirrhosis, ascites, infection, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Using logistic regression analysis, survival was significantly higher in groups Q2, Q3, Q4 than in group Q1 in Models I–II, and remained significantly higher in groups Q3, Q4 than in group Q1 in Models III–IV (Table 2). Furthermore, as the OR decreased with increasing serum ACR.

Analysis of calibration curve and decision curve

In order to further explore the predictive stability and clinical application prospects of serum ACR, we conducted calibration curve and decision curve analysis. It is not difficult to see from the calibration curve that the overall predicted probability of serum ACR is in good agreement with the actual probability (Fig. 4A). By calculating the net benefit (NB) under the risk threshold to obtain the DCA of serum ACR, it can be observed that the NB of serum ACR is basically located above all intervention NB and zero intervention NB (Fig. 4B), so serum ACR has high application value.

Stratified analysis of 28-day adverse outcomes by ACR

To further assess the impact of serum ACR on adverse clinical outcomes, we performed stratified analyses of the interactions between individual-related risk factors and serum ACR, including sex, age (> 50 and ≤ 50 years), TB level (> 12 and ≤ 12 mg/dL), and INR (> 1.5 and ≤ 1.5). However, due to sample size limitations, some subgroups were difficult to reliably analyze because of small numbers of individuals analysis, the results were not presented. Stratified analyses showed that Q4 consistently demonstrated a lower risk of death (Fig. 5). It suggested that a lower serum ACR is associated with an increased risk of 28-day death in patients with ACLF, regardless of baseline level. HBV infection was the predominant etiology in our cohort (85%), so we further investigated the effect of serum ACR levels in patients with HBV-associated ACLF. Logistic regression showed that survival remained significantly higher in the Q4 group than in the Q1 group after full adjustment, and that serum ACR levels were still significantly associated with poor outcomes (Table 3).

Discussion

The global burden caused by CLD should increase the focus on preventing morbidity and mortality in these patients14. Our findings elucidate the impact of serum ACR levels on the characteristics and prognosis of patients with ACLF, suggesting that serum ACR is an independent risk factor for 28-day adverse outcomes.

ALB, produced by the liver and reflects the nutritional status of the patient. It is the most abundant protein in plasma15 and is essential for maintaining the osmotic pressure of plasma colloids16, which is the reson why ALB was initially introduced as a plasma volume expanding agent and has been widely used to increase the circulating blood volume in patients with burns, shock and blood loss. As research progressed, non-permeable functions of albumin were discovered, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, molecular transport, endothelial stabilization and immunomodulation17. ALB also binds multiple inflammatory mediators and regulates the immune response in systemic inflammation and sepsis through Toll-like receptor signaling18, and has been associated with the degree of inflammation, prognosis, and the mortality in a variety of diseases19. According to Shannon et al.20, individuals with low ALB levels usually have a poor prognosis. ALB levels are usually low in critically ill patients with a variety of diseases. This decrease may be attributed to the role of Alb in increasing the production of several anti-inflammatory substances (e.g., lipoxins, hemolysins, and protective proteins) during oxidative stress to promote disease recovery21. This process requires large amounts of albumin. ACLF is the cause of death in most patients with cirrhosis, which is characterized by high levels of systemic inflammation and a high short-term mortality rate, and ALB has been shown to be strongly associated with the prognosis of ACLF16,22.

The occurrence of acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common and serious clinical event that affects the survival of patients with cirrhosis23. According to the diagnostic criteria for ACLF established by the APASL, it has been shown that 22.8% of ACLF patients are diagnosed with AKI on admission24, and the persistence of AKI in patients with ACLF is associated with higher in-hospital mortality25. Systemic inflammation may be a key driver for the development of AKI in ACLF patients26. Increased inflammatory cytokines lead to an increased release of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species, which results in vasodilation of the visceral and intrahepatic vascular beds, dysregulation of the vasoactive mechanisms on one side, and dysfunctional mitochondrial function and/or impairment on the other side, which can result in the development of all complications, including AKI. Systemic inflammation stimulates the kynurenine pathway-mediated tryptophan catabolism, generating bioactive metabolites that simultaneously induce multiorgan dysfunction and foster an immunosuppressive cellular state27. Serum creatinine is a useful biomarker for assessing renal function, and elevated levels correlate with poor prognosis in patients with ACLF, in whom elevated serum creatinine levels may be indicative of impaired renal function, which correlates with high short-term mortality28. ACR combines information from both nutritional and renal function and may provide a more comprehensive prognostic assessment than either indicator alone. This comprehensive assessment helps physicians to more accurately determine a patient’s health status and possible disease progression. Therefore we explored the prognostic relationship between serum ACR and ACLF in this study.

Previous studies had shown that serum ACR was associated with prognosis in a variety of diseases including acute pancreatitis29, heart failure30, and myocardial infarction31. In our study, we found that lower ACR levels were accompanied by higher MELD, MELD-Na, iMELD and CP scores, indicating an increased incidence of adverse clinical outcomes. When the ACR was less than 0.388, the mortality rate is as high as 50%. The ROC analysis with K-M survival analysis also provided support for the better predictive ability of serum ACR for adverse outcomes in ACLF. And the ROC analysis showed that the AUC of ACR was larger than the AUC of ALB and Cr, which also supported that the predictive performance of the combined metrics was better than that of the individual metrics. We then further assessed the impact of serum ACR on adverse clinical outcomes. First, we adjusted for gender, age, INR, Na, infection, ascites, cirrhosis, and bleeding in a multivariate logistic regression model and found that serum ACR remained an independent factor for adverse clinical outcomes in ACLF patients. The same results were obtained in subgroup analyses. In summary, serum ACR is a simple and practical clinical indicator that can be used as an independent predictor of 28-day mortality in ACLF. This may help clinicians to implement more aggressive treatment strategies to reduce the mortality. However, since our study population is dominated by HBV-related ACLF, further research on non-HBV-related ACLF, such as alcohol-related ACLF and MASLD, needs to be expanded. This expansion should include epidemiological studies, investigations into pathophysiological mechanisms, and evaluations of treatment outcomes to achieve a comprehensive understanding.

However, there are some limitations of our study. It is a but-center retrospective study with a limited sample size, and there was a lack of research on the dynamics of serum ACR and its correlation with adverse outcomes, and other potential unmeasured confounding factors (nutritional status, inflammatory markers, previous therapies) are also difficult to obtain for analysis, and potential value of investigating changes in ACR over time as a direction for future research. A large, prospective, multicenter study is needed in the future to confirm these findings.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ACLF:

-

Acute-on-chronic liver failure

- ACR:

-

Albumin to serum creatinine ratio

- APASL:

-

Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver

- AUC:

-

Areas under the curve

- ALT:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- CLD:

-

Chronic liver diseases

- CP:

-

Child–Pugh score

- HE:

-

Hepatic encephalopathy

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- iMELD:

-

Integrated MELD

- K:

-

Potassium

- MASLD:

-

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

- MELD:

-

Model for end-stage liver disease

- Na:

-

Natrium

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curve

- TBIL:

-

Total bilirubin

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

References

Asrani, S. K., Devarbhavi, H., Eaton, J. & Kamath, P. S. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J. Hepatol. 70(1), 151–171 (2019).

Gines, P. et al. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 398(10308), 1359–1376 (2021).

Tsochatzis, E. A., Bosch, J. & Burroughs, A. K. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 383(9930), 1749–1761 (2014).

Wu, X. N. et al. Global burden of liver cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases caused by specific etiologies from 1990 to 2019. BMC Public Health 24(1), 363 (2024).

Bajaj, J. S. et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: Getting ready for prime time?. Hepatology 68(4), 1621–1632 (2018).

Choudhury, A. et al. Liver failure determines the outcome in patients of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF): Comparison of APASL ACLF research consortium (AARC) and CLIF-SOFA models. Hepatol. Int. 11(5), 461–471 (2017).

Sarin, S. K. et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: Consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver (APASL): An update. Hepatol. Int. 13(4), 353–390 (2019).

Bernardi, M. et al. Albumin in decompensated cirrhosis: New concepts and perspectives. Gut 69(6), 1127–1138 (2020).

Zhang, Q., Shi, B. & Wu, L. Characteristics and risk factors of infections in patients with HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure: A retrospective study. PeerJ 10, e13519 (2022).

Xiao, L. et al. The 90-day survival threshold: A pivotal determinant of long-term prognosis in HBV-ACLF patients—Insights from a prospective longitudinal cohort study. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 11(16), e2304381 (2024).

Rui, F. et al. Derivation and validation of prognostic models for predicting survival outcomes in acute-on-chronic liver failure patients. J. Viral Hepat. 28(12), 1719–1728 (2021).

Mikolasevic, I. et al. Clinical profile, natural history, and predictors of mortality in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). Wien Klin. Wochenschr. 127(7–8), 283–289 (2015).

Olawale, O. O. et al. Assessment of renal function status in steady-state sickle cell anaemic children using urine human neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and albumin:creatinine ratio. Med. Princ. Pract. 30(6), 557–562 (2021).

Bajaj, J. S. Defining acute-on-chronic liver failure: Will East and West ever meet?. Gastroenterology 144(7), 1337–1339 (2013).

Rothschild, M. A., Oratz, M. & Schreiber, S. S. Serum albumin. Hepatology 8(2), 385–401 (1988).

Baldassarre, M. et al. Determination of effective albumin in patients with decompensated cirrhosis: Clinical and prognostic implications. Hepatology 74(4), 2058–2073 (2021).

Sun, L. et al. Impaired albumin function: A novel potential indicator for liver function damage?. Ann Med 51(7–8), 333–344 (2019).

Alcaraz-Quiles, J. et al. Oxidized albumin triggers a cytokine storm in leukocytes through P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase: Role in systemic inflammation in decompensated cirrhosis. Hepatology 68(5), 1937–1952 (2018).

Liu, Q. et al. Association between lactate-to-albumin ratio and 28-days all-cause mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis: A retrospective analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Front. Immunol. 13, 1076121 (2022).

Shannon, C. M. et al. Serum albumin and risks of hospitalization and death: Findings from the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 69(10), 2865–2876 (2021).

Das, U. N. Albumin and lipid enriched albumin for the critically ill. J. Assoc. Phys. India 57, 53–59 (2009).

Baldassarre, M. et al. Albumin homodimers in patients with cirrhosis: Clinical and prognostic relevance of a novel identified structural alteration of the molecule. Sci. Rep. 6, 35987 (2016).

Cholongitas, E. et al. RIFLE classification as predictive factor of mortality in patients with cirrhosis admitted to intensive care unit. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 24(10), 1639–1647 (2009).

Jindal, A., Bhadoria, A. S., Maiwall, R. & Sarin, S. K. Evaluation of acute kidney injury and its response to terlipressin in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Liver Int. 36(1), 59–67 (2016).

Maiwall, R. et al. AKI persistence at 48 h predicts mortality in patients with acute on chronic liver failure. Hepatol. Int. 11(6), 529–539 (2017).

Arroyo, V. et al. The systemic inflammation hypothesis: Towards a new paradigm of acute decompensation and multiorgan failure in cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 74(3), 670–685 (2021).

Claria, J. et al. Orchestration of tryptophan-kynurenine pathway, acute decompensation, and acute-on-chronic liver failure in cirrhosis. Hepatology 69(4), 1686–1701 (2019).

Huang, Z. et al. Acute kidney injury in hepatitis B-related acute-on-chronic liver failure without preexisting liver cirrhosis. Hepatol. Int. 9(3), 416–423 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Association between serum creatinine to albumin ratio and short- and long-term all-cause mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis admitted to the intensive care unit: A retrospective analysis based on the MIMIC-IV database. Front Immunol. 15, 1373371 (2024).

Li, S., Xie, X., Zeng, X., Wang, S. & Lan, J. Association between serum albumin to serum creatinine ratio and mortality risk in patients with heart failure. Clin. Transl. Sci. 16(11), 2345–2355 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Prognostic value of serum albumin-to-creatinine ratio in patients with acute myocardial infarction: Results from the retrospective evaluation of acute chest pain study. Medicine (Baltimore) 99(35), e22049 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the donors and patients for participating in this study.

Funding

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81974530) and Hubei Provincial Science and Technology Innovation Talents and Services Special Program (No.2022EHB039), Hubei Provincial Science and Technology Innovation Talents and Services Special Program (No.2023EHA057), Hubei Provincial Science and Technology Innovation Talents and Services Special Program (No.2024EHA053).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design (LZ, SPX), acquisition of data (JX, TTB), analysis and interpretation of data (JX, TTB, JXS), drafting of the manuscript (JX, TTB, JSX), critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (LZ, SPX, JX). All authors have made a significant contribution to this study and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Each participant provided written informed consent, the research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Union Hospital, Tongji medical college of Huazhong university of science and technology.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, J., Bian, T., Su, J. et al. Association between serum albumin to creatinine ratio and mortality risk in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Sci Rep 16, 3640 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33680-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33680-6