Abstract

This study seeks to optimize and evaluate the wear behavior of glass fiber–reinforced epoxy (G-E) nanocomposites incorporating organomodified montmorillonite (oMMT) nanoclay through a rigorous statistical modeling framework. Nanocomposites were prepared with different grades of oMMT (NC-I, NC-II, NC-III, NC-IV) and compared with neat G-E + NC-00 and unmodified NC-V composites. Structural characterization through XRD confirmed enhanced interlayer spacing (up to 5.04 nm for E + NC-III), indicating successful intercalation/exfoliation, while FTIR spectra verified the incorporation of epoxy chains within organoclay galleries. Dry-sliding wear behaviour was evaluated on a pin-on-disc tribometer as per ASTM G99-17 standards, with applied load (8.18–41.82 N), sliding velocity (0.25–2.44 m/s), and sliding distance (318–2177 m) as process variables. Among all tested systems, the G-E + NC-III nanocomposite consistently exhibited the lowest specific wear rate (9.54–40.29 × 10− 6 mm3/Nm), outperforming the neat matrix (10.11–43.33 × 10− 6 mm3/Nm) across all loading and velocity conditions. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and Central Composite Design (CCD) were employed to reduce experimental runs and evaluate parameter interactions. ANOVA revealed that applied load was the dominant factor influencing wear, contributing 68.73% in G-E + NC-00 and 69.03% in G-E + NC-III composites, followed by sliding velocity (≈ 7%) and quadratic effects of AL2 and SV2 (≈ 12%). Regression models developed for both systems demonstrated excellent correlation with experimental data (R2 = 96.4% for G-E + NC-00 and 95.65% for G-E + NC-III), with prediction errors ranging between 4.1% and 11.9%. Overall, the incorporation of oMMT nanoclay, particularly NC-III, significantly enhanced interfacial adhesion, promoted uniform dispersion, and reduced wear loss under varying tribological conditions. The statistical analysis confirms Response Surface Methodology (RSM) as a robust and effective approach for predicting wear performance and identifying optimal processing parameters. The optimized formulation (G-E + NC-III) exhibits strong potential for use in high-wear engineering domains such as automotive body panels, aerospace components, and structural assemblies, where the combination of lightweight construction and enhanced durability is critical.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wear is still a major challenge in many engineering applications especially for the aerospace, automotive and chemical industries when component’s service life and operation performance are affected by material lose under tribological conditions. To overcome these challenges, polymer composites have become the alternative solutions to conventional metallic systems in gears, cams, brakes, seals and bushing applications. The increasing popularity of these materials is due to the possibility of modifying properties by careful choice of reinforcement fibers and fillers to functional requirements in each application1. Materials in tribological systems are mainly controlled by coefficient of friction, wear rate and load carrying capacity. As a result, understanding the nature of wear and friction processes that occur in polymer-based composites has become critically important as new engineering applications place more demanding needs on materials such as higher load-carrying capacity, extended operation at elevated temperature and harsher operational conditions2. As compared to metals and ceramics, polymers present multiple inherent benefits such as lower density, better corrosion resistance, ease of processing, and a very good strength-weight ratio thus qualifying as light weight structure and tribological component candidates. However, their poor wear properties and thermal stability lead to modification with the addition of fibre and nanofillers3. In this context, the fiber and organomodified nanoclay reinforced polymer-based nanocomposites led to synergistic or superimposing enhancement in mechanical properties, dimensional stability, and wear resistance. These improvements result from the load transfer between the phases, an enhanced interfacial adhesion and a homogeneous distribution of fillers in the matrix and cast these hybrid material systems as potential candidates for advanced engineering applications4.

The degree of property improvement attained in PMC depends largely on the type of matrix, fibers, fillers and fabrication techniques utilized. Among the matrix materials available, epoxy resins have been widely used owing to their promising mechanical, thermal, chemical and tribological properties as well as their relative low cost and easy availability5,6. In addition, glass fibers are widely considered as reinforcing members for epoxy composites due to their good interfacial bonding strength with the matrix. Furthermore, the glass fibers bring high specific strength and high stiffness, excellent processibility and economic viability compared with the other fiber reinforcements. Epoxy resin has become one of the most widespread matrix materials in the development of advanced composites based on the excellent properties of high intensity, strong adhesive performance, electrical insulating capacity, minimal shrinkage, low cost, and easy processing. These properties have facilitated their wide use in the automotive, aerospace, and rail transportation sectors for tribological purposes7,8. Nevertheless, the intrinsic brittleness, low thermal stability, low toughness, and poor fatigue, properties as well as the high resistance to wear limit the applications under various harsh conditions. In order to overcome these limitations, reinforcement with fibers and fillers is extensively applied to improve the mechanical and tribological performance of epoxy-based composites9.

Epoxy composites reinforced with glass fibers are extensively used in structural and automotive applications; however, their performance is often limited by low elastic modulus, inadequate fiber–matrix adhesion, and susceptibility to abrasion arising from interfacial imperfections10. Recent advances indicate that using nanoscale fillers in polymer composite offers a promising strategy to overcome these challenges, as nanofillers can serve as second reinforcement and can significantly enhance the mechanical, thermal and wear properties to a large extent with little increment of weight. These kinds of nanocomposites are obtaining increased attention for high-quality applications as those in space, marine, automotive, construction and sporting sectors11. The addition of fibers into epoxy matrices provides a significant improvement to the mechanical performance of composites, while glass fibers are the most used reinforcement, due to their high strength-to-weight ratio and low cost8. The fiber reinforced polymer composites are generally stronger than the unfilled systems typically 1–4 times; nevertheless, poor interfacial adhesion between the fiber and the matrix usually results in debonding and degradation of the properties. In addition, their insufficient thermal stability, wear and oxidation resistance render them unsuitable for tribological service. To obtain some desirable tribological properties and meanwhile remaining lightweight, nanometre-sized fillers are proved to be a capable way to improve wear resistance, thermal stability, and the overall tribological performance12.

Nanoclays among other types of nanofillers are preferred due to its expansive layer silicate structure, high aspect ratio (100–1500) and capacity to intercalate organic modifiers within their galleries. Their integration with glass fiber epoxy nanocomposites enhances the mechanical, thermal, electrical and barrier properties in comparison to regular composites as well13. Montmorillonite (MMT) nanoclay, among others, is extensively researched due to its availability, high specific surface area, low cost and epoxy compatibility provided that the surface hydroxyl groups are modified. However, uniform dispersion and attention to the aspect ratio are still challenging during processing because the extent of intercalation and exfoliation depends highly on the surface chemistry, the clay loading, and the organic modifier14. Various inorganic particulates, fibers, clays, and polymer particles have been used as fillers in the case of polymeric nanocomposites and layered silicate clays are of certain interest in that they have been reported to be effective in improving the properties of material. Among them, MMT nanoclay is the most widely studied one due to its abundant availability, high aspect ratio aspect, large interfacial area, easy surface modification as well as high compatibility as an epoxy reinforcement filler10,15. The quality of dispersion, particle size, loading and interfacial adhesion, as well as processing conditions, have significant effects on both the friction and wear properties of these composites. According to the degree of clay dispersion, polymer nanocomposites can be classified as micro composites, intercalated nanocomposites, and exfoliated nanocomposites, and the individual morphology presents the different amounts to tribological improvements16.

Hence surface modification of MMT is necessary to obtain a uniform dispersion and desirable morphologies in the polymer matrix. The organic modification of alkylammonium ions has widely been used to expand the interlayer space, to allow penetration of polymer chains and to promote intercalation or exfoliation16. It has been reported previously that low clay loadings (~ 1% wt%) is able to induce exfoliated or intercalated structures, enhancing its thermal, structural, and morphological properties. Similarly, modifications with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) and other quaternary alkylammonium ion, modifiers match to give a better exfoliated morphologies than primary alkylammonium modifiers in the epoxy–MMT nanocomposite, which gives better compatibility and performance17. Surface modification and optimised filler loading have great effects on the nanostructure of clay–polymer nanocomposites, and the excessive content of nanoclay generally results in agglomeration and wicked dispersion18. It has been well documented that the best wear performance was achieved at low filler loadings and the optimal wear results have been reported at 1–3 wt% clay content19. At an optimum nanoparticle loading of approximately 2 wt%, the nanoscale platelets effectively stabilize the transfer film on the counterface through strong interfacial bonding, thereby minimizing wear. However, at higher concentrations, particle agglomeration can weaken interfacial adhesion and degrade the composite’s tribological performance. Pristine montmorillonite (MMT) clays are difficult to disperse due to the hydrophilic characteristic and lack of organic matrix affinity, which necessitates pre-conditioning in the form of organoclays20. MMT is converted to an organophilic-type by ion-exchange reaction in the presence of cationic surfactants for burring and its better performance in epoxy matrices. Enhanced wear resistance and reduced friction were recorded for sonicated organoclay-filled epoxy nanocomposites as compared to the unmodified clay systems as reported in many of the studies, even at very low concentration filled systems21. Enhanced interfacial adhesion, fibre–matrix wettability and the formation of thin and consistent transfer films are the key mechanisms behind such improvements. These results suggest that organomodified MMT is a good secondary reinforcement for the preparation of epoxy nanocomposites with excellent tribological properties.

Recently, the organic modifiers based on alkylammoniums have been extensively used to modify the interlayers of clay to ensure the compatibility of clays and the polymer matrices22. This surface modification not only increases the basal space of clays, thereby promoting the intercalation polymer chains but also serves as a compatibilizer between the hydrophilic silicates and the hydrophobic polymers23. Therefore, the fabrication of polymer nanocomposites with controlled surface functionalities and uniform particle size distribution has become very important for improving the properties. A number of researches showed that organoclay-filled epoxy nanocomposites show superior tribological performance than the unmodified system, particularly, at low filler contents (≈ 1–2 wt%), to maintain uniform dispersion, so as to have a better interfacial adhesion, a stable transfer film, and a low coefficient-of-friction (COF) with minimal wear24. Glass fiber–reinforced epoxy (G-E) composites are widely utilized due to their high specific strength, stiffness, and processability. However, their inherent brittleness, poor wear resistance, and limited thermal stability restrict performance under demanding tribological conditions. Incorporation of nanofillers such as organomodified montmorillonite (oMMT) has been shown to improve mechanical, thermal, and tribological performance, primarily through enhanced interfacial adhesion, uniform dispersion, and transfer film formation during sliding. Literature studies indicate that oMMT nanoclays, even at low loadings (1–3 wt%), significantly reduce specific wear rate and friction coefficient by reinforcing the epoxy matrix at the nanoscale and stabilizing the fiber–matrix interface25.

The reviewed studies collectively illustrate that statistical and computational optimization methods such as Taguchi design, Response Surface Methodology (RSM), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), and hybrid modeling have been successfully employed to tailor the wear behavior of glass fiber/epoxy nanocomposites reinforced with nanoclays and nanoparticles, as summarized in Table 1. Traditionally, most investigations relied on conventional single-factor experimental methods, which limited their ability to capture interaction effects among multiple process parameters such as applied load, sliding velocity, and sliding distance. This gap highlights the necessity of Design of Experiments (DOE) as a more systematic approach to study composite behavior. The objectives of this investigation focus on examining the influence of organomodified nanoclay (oMMT) on the wear behavior of glass fiber–reinforced epoxy nanocomposites, with particular attention to nanoclay morphology, dispersion quality, and interfacial compatibility. The study further aims at developing and validating a statistical predictive model for specific wear rate using Response Surface Methodology (RSM), enabling a comprehensive assessment of the main and interaction effects of applied load, sliding velocity, and sliding distance. In addition, the research emphasizes optimizing the tribological performance of G-E/oMMT nanocomposites through integrated experimental evaluation and RSM-based multi-parameter analysis, ultimately identifying the most effective nanoclay formulation for enhanced wear resistance. The motivation for employing glass fiber–reinforced epoxy as the polymer matrix due to its favorable strength-to-weight ratio and widespread use in structural applications, and for incorporating organomodified nanoclay based on its proven ability to enhance interfacial bonding, dispersion stability, and wear resistance.

Novelty of the present study

In this work, a novel experimental tribological test and statistical modeling are combined to develop glass fiber–epoxy polymer nanocomposites with improved wear resistance. Apart from the traditional ‘one-factor-at-a-time’ approach, Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is used to investigate and optimize the interactions of applied load, sliding velocity, and sliding distance on specific wear rate of composites simultaneously. An import methodology of this work consists of introducing organo-modified nanoclay (2 wt%) particle as a reinforcing filler to wear improvement. The systematic comparison of nanoclay-modified neat epoxy (G-E + NC-00) and unmodified nanoclay-composite (G-E + NC-V), and organoclay-reinforced materials (G-E + NC-I to IV) sheds new light on the impact of nanoclay surface modification and dispersion abilities on tribological response.

This study’s novelty stems from its dual contribution:

-

Research development – A study on nanoclay morphology and interfacial compatibility effects in suppression of wear at low filler loading.

-

Methodological development – Application of RSM for multi parameter optimization that allows the effective probing of the dominant parameters and their interactions while minimizing experimental effort.

This work, by combining morphological reinforcement and data-driven statistical optimization, demonstrates a comprehensive and scalable approach for the design of high-performance polymer nanocomposites with improved wear resistance.

Materials and methodology

Materials

A medium-viscosity epoxy resin (LAPOX L-12; density: 1.2 g/cm3; elastic modulus: 3200 MPa) and its corresponding hardener (K-6) were procured from Atul Ltd., Gujarat, India. The Physical and Mechanical properties of EP L-12 and plain-woven glass fibre are illustrated in the Table 2. The resin-to-hardener ratio was maintained at 100:10 by weight, as recommended in the supplier’s technical datasheet as presented in Table 3A plain-woven bidirectional epoxy/glass fabric (7-mil) was employed as the primary reinforcement and supplied by Suntech Fiber Pvt. Ltd., Bengaluru, India. Organomodified montmorillonite (oMMT) nanoclays with different basal spacings (Shelsite series: NC-I, 1.92 nm; NC-II, 3.15 nm; NC-III, 1.85 nm; NC-IV, 2.36 nm) and unmodified Na⁺-MMT (NC-V, 1.17 nm) were obtained from Nanoshel LLC, Wilmington, DE, USA. The organ modification of the clays was based on alkylammonium salts, namely: 2MBHT (dimethyl benzyl hydrogenated tallow, quaternary ammonium), 2M2HT (dimethyl di-hydrogenated tallow, quaternary ammonium), and MT2EtOH (methyl tallow bis-2-hydroxyethyl, quaternary ammonium). All materials were used as received without further purification.

Composite fabrication

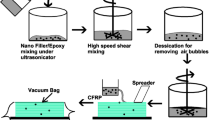

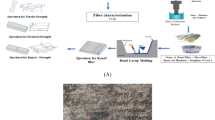

Figure 1 demonstrates the fabrication process for nanoclay-reinforced glass fiber–epoxy nanocomposites. Organoclay was first dried in an oven at 70 °C for 4 h to remove moisture. Epoxy resin was preheated to 80 °C to reduce viscosity prior to mixing. A known quantity of nanoclay was initially dispersed in the resin using a mechanical stirrer (10–20 min) and subsequently subjected to magnetic stirring for 2 h at 1200 rpm and 60 °C. The mixture was then ultrasonicated for 20–30 min to ensure homogeneous dispersion, followed by an additional 2 h of magnetic stirring. Entrapped air was removed through vacuum degassing, after which the mixture was cooled for 10 min. The curing agent was then added in a stoichiometric ratio (10:1 v/v resin-to-hardener) at ambient temperature and blended for 5 min using a mechanical stirrer. A final vacuum degassing step was performed before fabrication40,41. The composites were prepared by the hand lay-up technique. The resin–nanoclay–hardener mixture was uniformly applied onto plain-woven bidirectional glass fabric layers, stacked sequentially to form an 18-ply laminate. The lay-up was covered with a matt-finished fabric, pressed between release-coated steel plates, and subjected to initial curing in a hydraulic hot press at 100 °C for 1 h. post-curing was performed under ambient conditions for 24 h, as presented in Fig. 2. The cured laminates (300 × 300 × 3 mm3) were cut into wear test specimens (10 × 10 × 3 mm3) using a diamond-tipped cutter as presented in Fig. 3. Neat glass–epoxy composite (G-E + NC-00) and five nanoclay-filled glass–epoxy nanocomposites (G-E + NC-I, G-E + NC-II, G-E + NC-III, G-E + NC-IV, and G-E + NC-V) were fabricated following this procedure, with variation only in the type of nanoclay employed.

Testing

Micro-hardness

The Vickers microhardness (Hv) tests were performed at room temperature using an MV1-PC microhardness tester equipped with a diamond square pyramid indenter and an integrated video port for imaging. All measurements were carried out in compliance with ASTM E384-17 standards. Prior to testing, the specimen surfaces were polished sequentially with 800-grit SiC emery paper and buffed to achieve a mirror finish, followed by acetone cleaning to eliminate contaminants. An applied load of 100 g was maintained for a dwell time of 15 s per indentation. For statistical reliability, five indentations were made at five distinct locations on each specimen, and the average value was reported as the representative hardness.

Material characterization techniques

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra of samples were recorded by Vector-22 on a Perkin Elmer 1600 FTIR (MA, USA). The disc of 13 mm in diameter and 1 mm thick under vacuum containing 0.0010 g of E + NC (gel coat) sample and 0.3 g of fine grade K Br powder was scanned with 64 scans and averaged at wave number range from 400 to 4000 cm− 1 with a nominal resolution of 4 cm− 1. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis: XRD patterns were analysed to explore morphological structures formed in the nanocomposites. The diffraction angle 2θ was scanned from 10° to 60° on a X Pert PRO diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (wavelength λ = 0.1541 nm) at 45 kV and 40 mA at scanning rate 2° min− 1.

Dry-sliding wear test

The dry sliding wear behavior of the composites as depicted in Fig. 4 was evaluated using a pin-on-disc test apparatus in accordance with ASTM G99-19 standards, and the experimental procedure has been reported elsewhere30. All wear tests at each RSM–CCD design point was performed in triplicate (n = 3), with center-point trials repeated five times to ensure repeatability, minimize experimental variability, and establish statistical confidence in the results. The process parameters and their corresponding levels employed for all composite specimens are summarized in Table 4. The SWR values were derived based on the measured volume loss, applied load, and sliding distance, following standard tribological evaluation procedures as illustrated in the Eq. (1)26.

where, Δv, volume loss in mm3, L, applied load in N and D, sliding distance in m.

Statistical modelling and experimental design

The wear behavior of the developed composites was analyzed using the Response Surface Methodology (RSM), a statistical tool that enables the development of mathematical models for predicting composite responses based on independent variables and their interactions. RSM significantly reduces the number of experimental trials required for evaluating multiple parameters, making it less laborious and time-consuming compared to conventional approaches. In the present study, a rotatable Central Composite Design (CCD) was employed to construct the response surface39. The design consisted of 20 experimental runs, including 8 factorial points, 6 axial points, and 6 centre points, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The experimental plan for three process variables (A, B, and C), each at five coded levels (− 1.682, − 1, 0, + 1, and + 1.682), is presented in Table 5.

The wear behavior of the composites was modeled using a second-order polynomial regression equation to study the parametric influence of the process variables. This mathematical model established the relationship between experimental and predicted results, with the specific wear rate (WS) considered as the response variable. The independent variables were applied load (AL, A1), sliding velocity (SV, B2), and sliding distance (SD, C3). The coefficients a11, a22, and a33 represent the quadratic terms of the independent variables, while a12, a13, and a23 denote the interaction effects among them, as expressed in Eq. (2)36.

To evaluate the statistical significance of the model, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed. ANOVA partitions the total variance into components attributed to different sources and determines which design parameters significantly affect the response. The F-value, calculated at probability levels of 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, was used as the basis for establishing significance. The experimental plan was designed using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with a Central Composite Design (CCD), which is widely recognized for its efficiency in reducing experimental effort while capturing the effects of multiple variables and their interactions28. Coded levels of the process parameters were transformed into natural levels using standard transformation Eqs30,39. , as shown in Eq. (3) and Eq. (4). This design enabled systematic evaluation of the dry sliding wear behavior under the selected parameter combinations.

Results and discussion

XRD analysis

The structural characteristics of the epoxy–nanoclay (E + NC) nanocomposites were examined using X-ray diffraction (XRD) to evaluate the influence of nanoclay addition on the interlayer spacing and dispersion within the epoxy matrix. Table 6 compares the d-spacing values of the as-received organoclays with those of the synthesized nanocomposites. The pure epoxy resin exhibits a broad amorphous halo centered at 2θ ≈ 21.85°, typical of the disordered molecular arrangement in polymer matrices. The corresponding diffraction patterns of the prepared E + NC nanocomposites. In contrast, all E + NC nanocomposites displayed broad diffraction peaks between 18.9° and 19.7°, confirming a characteristic amorphous halo associated with the polymer matrix. The noticeable shift of these peaks toward lower 2θ values compared with neat epoxy signifies an increase in interlayer spacing (d-spacing), arising from the intercalation of epoxy chains into the clay galleries. Such peak displacement is consistent with previous literature42, validating the expansion of intralamellar spacing due to polymer–clay interaction. The sequence of d-spacing values for the as-received organoclays followed NC-II > NC-IV > NC-I > NC-III > NC-V; however, after dispersion in the epoxy matrix, the order changed to E + NC-III > E + NC-IV > E + NC-II > E + NC-I > E + NC-V. This inversion demonstrates the successful penetration of epoxy chains into the silicate layers, with E + NC-III exhibiting the greatest d-spacing, attributed to strong interfacial compatibility between the MT2EtOH modifier and the epoxy network as illustrated in the Fig. 6.

Furthermore, the absence of sharp diffraction peaks in the 5°–10° region indicates the delamination of clay stacks and formation of intercalated to partially exfoliated morphologies. The E + NC-III system (2θ = 18.95°) displayed the most pronounced shift and reduced peak intensity, confirming its superior exfoliation and homogeneous dispersion. Comparatively, E + NC-IV (19.31°) and E + NC-V (19.56°) exhibited slightly higher 2θ values, implying limited gallery expansion and partial intercalation, while E + NC-I and E + NC-II revealed moderate structural rearrangement. Variations in peak intensity across the composites reflect differences in crystallite alignment and the degree of nanoclay dispersion. Lower peak intensity correlates with enhanced exfoliation and improved polymer–clay interaction, which in turn contribute to better load transfer and mechanical integrity. These observations are consistent with earlier findings by Nagarjuna Reddy Paluvai and Smita Mohanty (2016)20 and Hiremath32, who also reported that the extent of intercalation strongly depends on the organic modifier type. Overall, the XRD results confirm that E + NC-III achieved a predominantly exfoliated structure, while other formulations remained intercalated findings that align with their superior mechanical and tribological performance43,44.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The FTIR spectra of the prepared E + NC nanocomposites (Fig. 7) exhibited characteristic absorption bands corresponding to epoxy and organoclay functional groups. A broad peak at ~ 2925 cm− 1 was assigned to C–H stretching vibrations of both aromatic and aliphatic groups. The bands observed at 1606 cm− 1 and 1506 cm− 1 correspond to C = C stretching and C–C aromatic vibrations, respectively. Peaks in the region of 1230–1295 cm− 1 and 1360–1385 cm− 1 were attributed to the deformation of –CH3 in C–(CH3)2 and C–H vibrations of –CH2/–CH3 groups. The absorption band at 1031 cm− 1 arises from C–O–C stretching in ethers, while the peak at 826 cm− 1 corresponds to C–O–C stretching in the oxirane ring45. The deformation of the epoxy bond was evident at 914 cm− 1, and the band at 767 cm− 1 was assigned to CH2 rocking vibrations. The presence of these characteristic peaks confirms the retention of epoxy functionalities in the nanocomposites and indicates that epoxy chains were successfully intercalated into the organoclay galleries. These findings are consistent with earlier reports, further validating the formation of intercalated/exfoliated structures within the E + NC systems46.

Micro-hardness

Microhardness indentation profiles captured on the surfaces of glass fiber–reinforced epoxy nanocomposites incorporating different nanoclay formulations is presented in the Fig. 8. An overall improvement in hardness was observed for all organoclay-filled composites compared to the neat system, with the maximum increase recorded for G–E + NC-III (24%), followed by G–E + NC-IV (15%), G–E + NC-II (10%), and G–E + NC-I (6%) are depicted in Fig. 9. The enhancement can be attributed to the intrinsic hardness of the nanoclay, which, upon indentation, distributes the applied compressive load more effectively across the glass fibers and fillers. The nanoclay platelets fill the gaps between the fibers and the epoxy matrix, forming a denser structure that resists penetration. Additionally, the formation of intercalated/exfoliated nanoclay–epoxy networks further restrict indentation, as nanoclays possess higher surface hardness due to their ceramic nature11. A distinct variation was noted between the highest and lowest hardness values: G–E + NC-III exhibited the greatest improvement, whereas G–E + NC-V showed a ~ 2% decrease compared to the neat specimen. This difference is attributed to the better dispersion and exfoliation achieved with organomodified nanoclay in G–E + NC-III, in contrast to the poor dispersion and tactoid formation in G–E + NC-V. Intermediate increases in hardness for G–E + NC-I, II, and IV are likely influenced by the lower basal spacing of their respective nanoclays and the type of organic modifier used, which limited reinforcement efficiency relative to G–E + NC-III. The increase in hardness can also be partially explained by strain-hardening phenomena, as multiple indentations during testing may have introduced localized plastic deformation, thereby raising hardness values. Similar findings have been reported by10, where incorporation of organomodified montmorillonite (Cloisite 30B) up to 3 wt% enhanced micro-hardness, followed by a decrease at higher clay loadings. These results confirm that the addition of organomodified nanoclays significantly improves the micro-hardness of glass fiber–epoxy composites, with optimum performance achieved at low clay concentrations47.

Dry-sliding wear performance of G-E + NC nanocomposites

The wear behavior of polymer nanocomposites is governed by key tribological parameters, namely the applied load, sliding velocity, and sliding distance.

Effect of applied load

The influence of applied load (10–50 N) on the specific wear rate of G–E + NC nanocomposites is presented in Fig. 10. All composites exhibited an increasing specific wear rate with rising load, a trend consistent with typical load-dependent frictional behavior. However, the magnitude of wear varied markedly among systems, highlighting the reinforcing effect of organoclay modification. The G–E + NC-III composites consistently demonstrated the lowest specific wear rates across all load conditions 0.8 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm at 10 N and 1.62 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm at 50 N compared with 2.6 × 10− 5 to 6.36 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm for the neat G–E + NC-00 matrix, representing a substantial reduction of approximately 70–75% in wear loss at higher loads. This superior performance is attributed to the uniform dispersion and exfoliation of MT2EtOH-modified nanoclay, which enhanced interfacial adhesion and facilitated efficient load transfer between the epoxy matrix and glass fibers. Moderate reductions were also observed for G–E + NC-II (50% lower wear) and G–E + NC-IV (60%), while G–E + NC-I exhibited modest improvement. In contrast, the unmodified clay composite G–E + NC-V showed the highest specific wear rate (8.36 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm at 50 N), reflecting poor interfacial bonding and clay agglomeration. These results confirm that organomodified nanoclay reinforcement, particularly NC-III, markedly improves the load bearing and wear-resistant characteristics of G–E epoxy nanocomposites. During initial sliding, induced stresses in the G–E + NC-00 matrix cause microdamage and weak interfacial adhesion, leading to matrix detachment and debris formation. Increasing load intensifies frictional heat, promoting ductility loss, microcracking, and brittle fracture, resulting in laminate-type debris separation from the fiber surface. Similar, observations have been reported in previous studies (Shivamurthy et al.,48.

SEM analysis of worn surfaces

The wear mechanisms of the G–E + NC composites were examined by analyzing the fractured surface morphologies using SEM under varying applied loads at a constant sliding velocity (1.5 m/s) and sliding distance (1500 m). At lower loads, the G–E + NC-00 composite exhibited localized stress-induced rupture of the epoxy matrix, resulting in small, fragmented debris on the fiber surfaces (Fig. 11a). Limited epoxy removal and reduced fiber exposure were observed under these conditions, correlating with lower specific wear rates. As the applied load increased, elevated frictional heat at the counter surface caused extensive fragmentation of the epoxy matrix, leading to larger material removal and greater exposure of glass fibers (Fig. 11b). Direct fiber–counterface interaction promoted fiber damage and detachment, thereby accelerating material loss and increasing the specific wear rate. Similar observations have been reported by Basavarajappa et al.49. In contrast, the G–E + NC-V composite displayed the highest specific wear rate among all systems tested. This was attributed to poor dispersion of unmodified clay, which retained tactoid-like aggregate structures (Fig. 11c). These agglomerates weakened fiber–matrix adhesion and facilitated the formation of a loose debris layer comprising fragmented epoxy on the composite surface. Such microstructural features significantly reduced interfacial bonding, thereby promoting higher wear losses50.

At applied loads beyond 30 N, the G–E + NC-V nanocomposite exhibited a sharp increase in specific wear rate, attributed to the removal of tactoid aggregates from the loosened composite structure. This behavior was manifested by deeper grooves on the worn surface (Fig. 11d), accompanied by extensive fiber exposure and breakage. With further increases in load, progressive material removal occurred, leading to poor tribological performance of the composite. In contrast, the G–E + NC-I, G–E + NC-II, and G–E + NC-IV nanocomposites showed a distinct transition in wear behavior. Beyond 30 N, the increasing trend in specific wear rate shifted towards a slight reduction, and the overall values remained lower than those of both G–E + NC-00 and G–E + NC-V. Similar to earlier findings, nanoclay particles played an active role as fillers in improving wear resistance28,37. However, incomplete dispersion and random orientation of some nanoplates reduced the effective aspect ratio and diminished their load-bearing capacity, thereby limiting their ability to support load transfer from the matrix to the fibers. This resulted in larger matrix fragmentation, as observed in G–E + NC-I (Fig. 12a, b), and consequently a higher specific wear rate compared to G–E + NC-II and G–E + NC-IV.

The G–E + NC-II nanocomposite initially exhibited reduced wear due to the development of a protective transfer film at the counterface, which served as an effective barrier against large-scale epoxy fragmentation (Fig. 12c). This contributed to fewer wear debris and lower fiber damage in the early stages of sliding. However, with increasing load (> 20 N), the transfer film became unstable and discontinuous, transforming fine debris into larger fragments and creating deeper grooves between fiber surfaces (Fig. 12d). This instability led to a higher specific wear rate than that observed for G–E + NC-III. Similarly, G–E + NC-IV demonstrated relatively low specific wear rates during the initial sliding period, facilitated by the formation of a transfer film that restricted epoxy fragmentation. Aggregated debris in the form of patch-like structures was observed (Fig. 12e). At higher loads, the transfer film ruptured due to increased frictional heating, fragmenting into smaller particles that were subsequently removed from the tribosurface, exposing the fibers (Fig. 12f). Eventually, the specific wear rate of G–E + NC-IV approached a steady value, which remained lower than that of G–E + NC-I and G–E + NC-II nanocomposites51.

Among all the tested composites, the G–E + NC-III nanocomposite exhibited the lowest specific wear rate. Although its specific wear rate initially increased with applied load up to the mid-range, a highly significant improvement was consistently observed compared to the other composites. This superior performance can be attributed to the uniform dispersion of NC-III organoclay within the epoxy matrix, which enhanced the effective aspect ratio of the clay platelets and improved stress transfer. At lower loads, asperities on the composite surface first engaged with the counterface, creating localized contact points and increasing friction (Fig. 13a). With further loading, these asperities underwent plastic deformation, increasing the real contact area and generating fine wear debris. The progressive smoothing of asperities produced shallower wear tracks, reducing surface roughness. At higher loads, however, the combined epoxy–organoclay phase resisted large-scale fragmentation due to the improved interfacial adhesion between the matrix, organoclay, and fibers. The increased aspect ratio of the NC-III platelets promoted the formation of a thin, uniform transfer film on the sliding surface (Fig. 13b), thereby stabilizing the wear process. As a result, the specific wear rate of G–E + NC-III decreased markedly beyond 40 N and approached a constant value, confirming the formation of a persistent transfer layer33,52. These findings demonstrate that the incorporation of NC-III organoclay significantly enhances wear resistance in glass fiber–reinforced epoxy composites across all tested load conditions.

Effect of sliding velocity

Figure 14 illustrates the variation in specific wear rate as a function of sliding velocity (0.5–2.5 m/s) at a constant applied load of 30 N and sliding distance of 1500 m. The specific wear rate increased progressively with sliding velocity for all composites, though the magnitude of increase varied depending on the nanoclay modification. For the neat G–E + NC-00 composite, the specific wear rate rose from 2.95 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm at 0.5 m/s to 6.50 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm at 2.5 m/s, representing a 120% increase due to intensified frictional thrust, localized vibrations, and repeated impact loading at the sliding interface. These effects accelerated matrix–fiber debonding and micro-fracture, thereby elevating the wear rate53,54. In contrast, the organoclay-reinforced composites demonstrated markedly reduced wear, indicating the beneficial influence of nanoclay dispersion and interfacial strengthening. Among all tested systems, the G–E + NC-III nanocomposite exhibited the lowest specific wear rates of 0.85 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm at 0.5 m/s and 2.20 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm at 2.5 m/s corresponding an overall 66% redution in wear compared with the unfilled neat matrix. Even at an intermediate velocity of 1.5 m/s, G–E + NC-III maintained a significantly lower wear rate (1.55 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm) relative to the unfilled composite (4.65 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm). Although all composites followed an increasing wear trend with sliding velocity, G–E + NC-00 and G–E + NC-V displayed a near-linear relationship and higher specific wear rates, whereas organoclay-reinforced systems exhibited significantly improved wear resistance. Among them, G–E + NC-III consistently maintained the lowest specific wear rate across all test conditions, confirming the beneficial role of nanoclay in enhancing interfacial strength and the formation of a stable transfer film, which collectively resist frictional degradation and ensure superior tribological durability under dynamic sliding conditions.

SEM analysis of worn surfaces at different sliding velocities

The fractured surface morphologies of the G–E + NC composites were examined by SEM under varying sliding velocities at a constant applied load (30 N) and sliding distance (1500 m). In polymer matrix composites, surface temperature plays a critical role in governing wear behavior. For the G–E + NC-00 composite, higher specific wear rates at low sliding velocities were primarily associated with thermal softening, as polymers exhibit poor thermal conductivity55. At these conditions, only a thin softened epoxy layer formed on the fiber surface, resulting in relatively low wear intensity. However, with increasing sliding velocity, the surface temperature rose significantly, leading to the development of a thicker softened epoxy layer at the interface (Fig. 15a). This layer weakened fiber–matrix adhesion at the subsurface, promoting degradation wear and crack propagation. Prolonged sliding caused detachment of the softened layer from the fiber surface, triggering matrix loss through a fatigue delamination mechanism26,56. Consequently, extensive fiber exposure and large-scale fiber rupture were observed, leading to high specific wear rates (Fig. 15b).

Among all tested composites, the G–E + NC-V nanocomposite consistently exhibited the highest specific wear rate across sliding velocities. This behavior is attributed to the poor dispersion of unmodified clay, which promoted particle–particle interactions rather than particle–epoxy bonding. The resulting tactoid structures created weak interfacial adhesion and acted as stress concentrators, thereby accelerating wear. Similar findings have been reported by Jawahar et al.57, who demonstrated that the incorporation of organoclays enhances wear resistance, whereas unmodified nanoclays reduce it. In this study, the presence of NC-V tactoids led to severe surface damage characterized by matrix detachment, fiber exposure, and crack propagation. At elevated sliding velocities, SEM observations revealed extensive matrix removal and exposure of long glass fibers, often fractured or peeled off at the surface (Fig. 15c). Pulverized fibers, thinned and worn fiber fragments, surface cavities left after fiber pull-out, and heavily damaged regions were evident in the micrographs (Fig. 15d). These features further confirm that weak interfacial bonding in unmodified clay composites accelerates wear progression under dynamic sliding conditions58.

For G–E + NC-I, G–E + NC-II, and G–E + NC-IV nanocomposites, the specific wear rate increased almost linearly with sliding velocity up to 2.0 m/s, after which the rate of increase diminished (Fig. 16). This behavior reflects the strong influence of transfer film formation on the wear characteristics of polymer composites sliding against metallic counterface. A reduction in specific wear rate is generally associated with the formation of a stable transfer film, which minimizes direct adhesion and protects the composite surface50. In G–E + NC-I, a thick but non-uniform transfer film developed during sliding. At low velocities, the poor film quality combined with severe ploughing by counterface asperities resulted in fiber breakage and significant material removal (Fig. 16a). With increasing velocity, the transfer film became discontinuous (Fig. 16b), leading to unstable protection of the surface and, consequently, the highest specific wear rate among the organoclay composites tested. The G–E + NC-II nanocomposite formed a moderately thick transfer film that covered a larger surface area, thereby reducing asperity-induced ploughing and minimizing fiber breakage (Fig. 16c). As sliding progressed, however, the film was partially damaged, exposing fibers and generating fine epoxy debris clusters on the surface (Fig. 16d). This led to a moderate rise in specific wear rate, though still lower than that of G–E + NC-I. In G–E + NC-IV, a comparatively thin but more uniform transfer film was observed, which effectively resisted asperity ploughing and limited fiber damage (Fig. 16e). Consequently, the specific wear rate remained lower than that of G–E + NC-I and G–E + NC-II. At higher velocities, however, shear forces acting on the tribosurface caused deformation of asperities and projection of nanoclay particles from the transfer film. This led to localized fiber breakage and wear debris generation (Fig. 16f), resulting in a slight increase in specific wear rate, though still less severe than in the other organoclay nanocomposites28,29.

The G–E + NC-III nanocomposite exhibited the highest wear resistance among all tested systems, which can be attributed to its microstructure consisting of finely dispersed organoclay platelets. The incorporation of NC-III organoclay enhanced interfacial adhesion by acting as a crack arrester and facilitating effective load transfer. At low sliding velocities, the released organoclay smeared onto the wear surface and formed a thin, uniform protective film, limiting fiber exposure and fragmentation (Fig. 17a). This transfer layer was primarily responsible for the improved wear resistance, consistent with earlier findings that organomodified montmorillonite (oMMT) significantly enhances epoxy nanocomposite wear resistance at low filler loadings (Rashmi et al., 2011)59. At higher sliding velocities, repeated contact and increased friction raised the counterface temperature. Although some fiber exposure was evident, the organoclay released during initial sliding redistributed across the surface, forming an even thinner and more uniform transfer layer embedding the fibers (Fig. 17b). This protective film effectively shielded the fibers from direct contact, resulting in smoother wear tracks and significant wear reduction. Any wear loss observed was primarily due to localized fiber hatching induced by shear forces. These results confirm that organoclay acts as a secondary reinforcement within the epoxy matrix, providing enhanced resistance to sliding wear and maintaining low specific wear rates even under elevated velocity conditions.

Effect of sliding distance

Figure 18 depicts the variation in specific wear rate with sliding distance (500–2500 m) under a constant applied load of 30 N and sliding velocity of 1.5 m/s. At the initial stage of sliding (500 m), all composites exhibited relatively low specific wear rates due to limited real contact between the composite and the counterface. As sliding progressed, the specific wear rate gradually increased; however, the rate of increase was less pronounced compared to the variations observed with applied load and sliding velocity. Quantitatively, the unfilled G–E + NC-00 composite showed the highest specific wear rate, rising from 2.99 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm at 500 m to 4.91 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm at 2500 m. In contrast, the organoclay-reinforced composites displayed markedly improved wear resistance. Among them, G–E + NC-III recorded the lowest specific wear rate only 1.03 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm at 500 m and 1.52 × 10− 5 mm3/Nm at 2500 m representing nearly a 69% reduction in wear compared with the unfilled system. Nonetheless, at 2500 m sliding distance, other organoclay-modified systems except G–E + NC-V demonstrated reduced wear compared to the neat composite. The most notable improvement was achieved by G–E + NC-IV, showing a 38.5% reduction in wear rate relative to G–E + NC-00, followed by G–E + NC-II (26.9%) and G–E + NC-I (17.5%). In contrast, G–E + NC-V experienced a 4.7% increase, likely due to excessive clay agglomeration or poor interfacial bonding. The wear performance evaluation revealed a direct decrease in the specific wear rate with increasing hardness. The G–E + NC-III nanocomposite which exhibited the highest hardness enhancement, and registered the lowest specific wear rate, outperforming both the neat matrix and other organoclay variants. This relationship in turn confirms that the higher hardness provides better protection against plastic deformation, micro-cutting, and asperity-inducing damages while sliding47. The uniformly distributed organoclay platelets act as rigid load carriers in the epoxy matrix, which disperse stress effectively and prevent the initiation and propagation of subsurface cracks. Hence, the composites with superior hardness characteristics can dissipate less frictional energy to matrix deformation and exhibit significantly lower material loss per unit load and sliding distance, which confirms that the G–E + NC-III system possesses an excellent mechanical–tribological synergy.

In the case of the G–E + NC-00 composite, direct contact between the counterface and the epoxy matrix promotes simultaneous shearing and ploughing of the surface. These actions pulverize the epoxy into fine wear debris that accumulates on the fibre surface (Fig. 19a). With increasing sliding distance, progressive removal of this pulverized matrix exposes long glass fibres, leading to the formation of deeper grooves. Such behaviour reflects the weak interfacial integrity of the neat epoxy composite, where interfacial shear stresses dominate the wear process. Consequently, individual fibres come into direct contact with the counterface, causing fibre rupture and accelerated wear (Fig. 19b). Notably, the absence of a stable transfer film on the counter surface further exacerbates material loss, resulting in a higher specific wear rate for the neat epoxy system. For the G–E + NC-V nanocomposite, at lower sliding distances, the presence of unmodified clay particles comparable in size to segments of the surrounding polymer chains facilitates the development of a loosely adhered, non-uniform tribofilm on the counterface2 (Fig. 19c). However, this film lacks structural stability and is easily disrupted as sliding progresses. At higher distances, poor interfacial adhesion between unmodified clays and the epoxy matrix leads to detachment of clay particles from the tribofilm, extensive fibre exposure, and eventual fibre breakage. These mechanisms increase friction and significantly raise the specific wear rate. Surface observations further confirm severe defects, including dug-out sections, voids, and matrix–fibre debonding (Fig. 19d), indicating poor load-bearing capacity and weak structural integrity of the G–E + NC-V system25,39.

At the initial stage, sliding distance exhibited minimal influence on the specific wear rate of the G–E + NC-I, G–E + NC-II, and G–E + NC-IV nanocomposites. With increasing sliding distance, the specific wear rate of these composites rose steadily up to approximately 2000 m, beyond which it remained relatively stable. In the case of the G–E + NC-I nanocomposite, the shearing of organoclays during the early wear run led to the generation of wear debris, which progressively detached from the fibre surface (Fig. 20a). This mechanism contributed to the observed increase in specific wear rate. Beyond this stage, the specific wear rate stabilized, with only marginal increments in debris separation distance. As a result, shallow groove-like structures were formed, while fibre breakage and fibre exposure remained negligible even at extended distances (Fig. 20b). For the G–E + NC-II nanocomposite, the worn surface at lower sliding distances consisted primarily of a deformed epoxy matrix intermixed with segmented matrix fragments, organoclay particles, and wear powder originating from the metallic counterface. This combination led to the formation of a thick, mechanically weakened transfer film (Fig. 20c), which initially suppressed wear and resulted in a lower specific wear rate compared with G–E + NC-I. Minor dug-out sections and limited fibre exposure were also observed at this stage60. However, as sliding distance increased, progressive detachment of the transfer film constituents created deeper grooves, resulting in extensive fibre exposure and breakage (Fig. 20d). Consequently, the specific wear rate of G–E + NC-II increased significantly at longer sliding distances. In contrast, the G–E + NC-IV nanocomposite developed a thin, stable transfer film that remained intact over the wear tracks (Fig. 20e). This film cushioned the counterface, suppressed severe matrix damage, and limited the occurrence of dug-out sections during the initial stages of sliding. Nevertheless, at higher sliding distances, fragmented epoxy, detached organoclay particles, and metallic wear debris acted as third-body abrasives, leading to progressive abrasion of the counterface (Fig. 20f). Despite this, complete fibre exposure was not observed, and the wear resistance of G–E + NC-IV remained superior to that of G–E + NC-I and G–E + NC-II. Overall, the wear behaviour of G–E + NC-IV was strongly governed by the stability of the transfer film and the composition of the wear debris44.

In contrast to the other tested composites, the G–E + NC-III nanocomposite exhibited a significantly lower specific wear rate during the initial sliding stages (Fig. 21). This behaviour indicates that the presence of organomodified clays enhanced the shear strength of the epoxy matrix, thereby suppressing large-scale matrix degradation during the early wear process. Microstructural observations (Fig. 21a) revealed that organoclay platelets were uniformly embedded within the matrix and at the fibre–matrix interface, effectively impeding fibre exposure and reducing the severity of wear. At intermediate sliding distances, increased specimen–counterface interaction resulted in a mild rise in frictional forces, leading to the formation of small-scale wear debris and limited fibre exposure. However, the overall increase in specific wear rate remained modest compared with other composites, highlighting the superior wear resistance imparted by organoclay reinforcement.

At higher sliding distances, organoclay particles were progressively released from the fibre surface and deposited onto the tribosurface. These particles underwent shearing under counterface asperities and subsequently smeared across the sliding interface, facilitating the development of a thin, uniform, and stable transfer film (Fig. 21b). Once established, this transfer film covered a larger area of the tribosurface, creating a smoother sliding surface and shifting the frictional interaction predominantly between transfer film layers rather than direct composite–counterface contact. This mechanism effectively suppressed fibre exposure, minimized surface defects, and stabilized the wear response. As a result, the specific wear rate of the G–E + NC-III nanocomposite became nearly insensitive to further increases in sliding distance beyond 1500 m37.

The superior wear resistance of G–E + NC-III can also be attributed to its higher hardness relative to other nanocomposites. This improvement is linked to the intrinsic hardness of NC-III organoclay and its uniform dispersion within the epoxy matrix, which restricts epoxy segmental motion under indentation and contributes to enhanced tribological performance. Conversely, the lower hardness of the G–E + NC-V nanocomposite is associated with poor dispersion and clay agglomeration, limiting its strengthening effect and wear resistance. These findings are consistent with previous reports that hardness plays a crucial role in wear resistance and friction reduction in polymer nanocomposites. Overall, NC-III organoclay proved to be the most effective reinforcement in improving the wear performance of the studied systems, owing to its uniform dispersion, stable transfer film formation, and significant contribution to matrix hardness.

Statistical analysis

Fitting the model/ANOVA results

To evaluate the statistical significance of the selected process parameters on the dry sliding wear behaviour of G–E + NC composites, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed using the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) approach61. The analysis was carried out at significance levels of 1% and 10%, corresponding to confidence levels of 99% and 90%, respectively. The percentage contribution (Pc) of each parameter to the total variation was calculated to determine its relative influence on the wear response. A factor was considered statistically significant when the calculated F-test value exceeded the corresponding F-table value. Table 7 summarizes the ANOVA results for the G–E + NC-00 composite. It is evident that Applied Load (AL) is the dominant factor, contributing approximately 68.73% to the variation in specific wear rate, followed by Sliding Velocity (SV) at 6.94%. Among the quadratic terms, ALAL (4.82%) and SVSV (12.65%) also exhibited considerable influence on the wear response. Conversely, Sliding Distance (SD) and its interactions (SDSD, ALSD) were found to be statistically insignificant, suggesting that their contribution to the wear mechanism is negligible. The pooled error in this model was around 6.86%, and the adjusted R² value of 93.17% confirmed the adequacy and reliability of the model. These results clearly establish Applied Load as the most influential parameter in determining the wear behaviour of the G–E + NC-00 composite.

Similarly, Table 8 presents the ANOVA results for the G–E + NC-III nanocomposite. Here again, Applied Load emerged as the dominant factor, contributing 69.03%, followed by Sliding Velocity (6.52%). The quadratic terms ALAL (12.05%) and SVSV (4.13%) also played a significant role, while SD and its associated interactions were statistically insignificant and could be disregarded. The pooled error for this model was 8.27%, and the adjusted R² of 91.73% indicated good model fit. Thus, for G–E + NC-III, as with the G–E + NC-00 system, Applied Load remained the governing parameter influencing the specific wear rate, while Sliding Velocity had only a secondary effect. Overall, the ANOVA results demonstrate that wear in both neat epoxy (G–E + NC-00) and organoclay-filled epoxy (G–E + NC-III) composites is primarily governed by the applied load, whereas sliding distance plays an insignificant role in the studied parameter range. This highlights the strong dependence of composite wear behaviour on mechanical loading conditions rather than extended sliding duration39.

Multiple linear regression analysis

To further validate the experimental results, multiple linear regression (MLR) analysis was performed using the statistical software MINITAB 19 (trial version). This analysis established the correlation between the process variables Applied Load (AL), Sliding Velocity (SV), and Sliding Distance (SD) and the specific wear rate (WS) of the prepared composites. The regression equations thus derived provide empirical relationships describing the functional dependence of WS on the selected process parameters. For the G–E + NC-00 composite, the regression model (Eq. 5) yielded a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.964, which exceeds the threshold value of 0.8 generally accepted for strong model reliability. This high correlation confirms the adequacy of the developed model in predicting the wear response. Similarly, for the G–E + NC-III nanocomposite, a multi-linear polynomial regression model (Eq. 6) was developed. The corresponding R² value was found to be 0.9565, again well above 0.8, demonstrating that the model accurately represents the functional relationship between the process variables and specific wear rate for this nanocomposite system. Using these regression models (Eqs. 5 and 6), the predicted specific wear rate values for each experimental trial in the design matrix were calculated and compared against the experimental results. These predictions, summarized in Table 9, show close agreement with the measured data, thereby validating the robustness of the regression approach in capturing the wear behaviour of both neat epoxy (G–E + NC-00) and organoclay-reinforced (G–E + NC-III) nanocomposites.

.

The calculated values of specific wear rate obtained from the regression models were compared with the corresponding experimental results for the G–E + NC-00 and G–E + NC-III composites, as illustrated in Fig. 22a and b. The comparison clearly demonstrates that the regression-predicted values exhibit a trend closely matching the experimental observations, thereby confirming the reliability and predictive capability of the developed models in capturing the wear behaviour of the studied composites. The scatter diagrams illustrating the response of specific wear rate at different variable levels for the prepared composites are presented in Fig. 23a and b. It is evident that the experimental responses of all composites are in close agreement with the values predicted by the RSM model, with deviations confined within ± 7%. This close correlation reaffirms that the developed wear model is statistically significant and capable of reliably predicting the wear behaviour of the investigated composites36. The developed wear model was further validated by calculating the residual values for each experimental run, defined as the difference between the measured and predicted specific wear rate. The residual plots, presented in Fig. 24a and b, reveal that the data points are evenly distributed on both the positive and negative sides of the response axis, indicating the absence of systematic bias and confirming the adequacy of the model. Such uniform distribution demonstrates that the regression model reliably captures the wear behaviour of the composites. Comparable findings have also been reported in earlier studies62.

The minor variations observed in the results (Figs. 22, 23 and 24) can be attributed to experimental irregularities such as machine vibrations, environmental fluctuations, and human handling errors. Despite these inconsistencies, the experimental values were retained for further prediction and analysis. Overall, the developed multiple linear regression models for the G-E + NC-00 composite (Eq. 5) and G-E + NC-III nanocomposite (Eq. 6) demonstrated stability and reliability, confirming their suitability for accurately predicting the specific wear rate.

Experimental validation and verification of the RSM framework

To validate the accuracy of the predictive model, confirmation experiments were performed using a specific combination of factors and levels within the predefined variable ranges. The experimental conditions and their corresponding values are summarized in Table 10. For verification, an additional set of tests was conducted, and the results were compared with the predicted values obtained from the regression models (Eq. 5 and Eq. 6). The percentage error between experimental and calculated results was determined using Eq. 7, and the data are presented in Table 11. Analysis of the results reveals that the error for the G-E + NC-00 composite ranges between 4.13 and 11.36%, while for the G-E + NC-III nanocomposite it lies between 4.24 and 11.94%. These error margins fall within an acceptable range, thereby confirming that the developed regression models provide reliable predictions. Thus, the models present a feasible and effective approach for evaluating the dry sliding wear behavior of the tested composite systems30,41.

3D response surface analysis

The 3D response surface plots (Fig. 25a–f) illustrate the influence of the independent variables such as applied load, sliding velocity, and sliding distance on the specific wear rate of the G-E + NC-00 and G-E + NC-III composites. These plots provide a comprehensive visualization of the interactive effects of the process parameters.

Applied load and sliding velocity interaction

For the G-E + NC-00 composite (Fig. 25a), the specific wear rate remained relatively low at lower levels of load and velocity but increased substantially at higher values (35 N and 2 m/s). This behavior can be attributed to stress-induced surface damage and brittle matrix fracture caused by excessive frictional heat, leading to laminate-type wear debris (Fig. 26a)48. In contrast, the G-E + NC-III nanocomposite (Fig. 25b) showed reduced wear at low to moderate loads and velocities, with only marginal differences compared to the neat composite. This improvement is associated with the uniform dispersion of organoclay, which enhances the aspect ratio and strengthens the matrix–fiber interface. Initially, asperities on the nanocomposite surface engaged with the counterface, increasing localized friction. At higher loads, asperities underwent plastic deformation and removal, leaving a smoother surface with shallow wear marks (Fig. 26b).

Applied load and sliding distance interaction

As shown in Fig. 25c, the G-E + NC-00 composite exhibited lower wear at shorter sliding distances and low loads, primarily due to reduced matrix–counterface contact and limited shear ploughing. However, at higher loads and sliding distances (35 N, 1800 m), severe fiber exposure and matrix removal resulted in deeper grooves and poor transfer film formation, leading to accelerated wear (Fig. 26c). In contrast, the G-E + NC-III nanocomposite (Fig. 25d) benefited from the formation of a transfer film during the initial sliding stages, which acted as a protective layer. With increasing sliding distance, mild rises in wear were observed due to small-scale debris formation and limited fiber exposure63. At higher loads, however, frictional heating destabilized the transfer film, producing patch-like structures on the tribosurface and increasing the specific wear rate (Fig. 26d).

Sliding velocity and sliding distance interaction

The interaction of velocity and distance for the G-E + NC-00 composite (Fig. 25e) indicated moderate wear at lower values, followed by a temporary decrease at intermediate levels. This stage was characterized by a cooperative effect of residual epoxy and intact fibers resisting the sliding stresses. At higher velocities and distances, frictional heating fragmented the epoxy, exposing and ultimately fracturing the glass fibers, thereby generating significant wear debris (Fig. 26e)64. Conversely, the G-E + NC-III nanocomposite (Fig. 25f) initially experienced moderate wear due to small aggregates of poorly dispersed clays reducing fiber–matrix adhesion. With increasing velocity, wear decreased owing to the formation of a thin, uniform transfer film that effectively embedded the fibers. However, at prolonged sliding distances and higher velocities, shearing of the tribosurface caused organoclay particles to project out, exposing fibers to damage and leading to localized wear debris and fiber fragmentation (Fig. 26f).

Overall observations

Across all response plots, the G-E + NC-III nanocomposite consistently demonstrated superior wear resistance compared to the neat composite. The enhancement is primarily attributed to the uniform dispersion of organoclay, which improves load transfer, facilitates stable transfer film formation, and reduces extensive fiber exposure. Importantly, the magnitude of specific wear rate increase with sliding distance was less pronounced compared to variations in applied load and velocity, confirming that applied load exerts the dominant influence, followed by sliding velocity and then sliding distance. These trends are in strong agreement with the results obtained from conventional wear studies of both composites.

Conclusions

-

1.

The incorporation of organomodified montmorillonite (oMMT) nanoclays in glass fiber–epoxy composites significantly enhanced wear resistance compared to neat epoxy (G–E + NC-00) and unmodified nanoclay (G–E + NC-V) systems. oMMTs acted as effective secondary reinforcements by improving interfacial adhesion, restricting matrix fragmentation, and enabling uniform stress transfer.

-

2.

XRD and FTIR analyses confirmed intercalation and partial exfoliation of epoxy chains within organoclay galleries, with G–E + NC-III exhibiting the highest basal spacing (5.04 nm), indicating superior structural compatibility and interfacial bonding in the nanocomposite.

-

3.

The G–E + NC-III composite exhibited a 24% hardness enhancement compared to the base composite (18.64 HV → 23.12 HV), confirming superior organoclay dispersion and strong interfacial bonding, thereby improving mechanical integrity and wear resistance of the nanocomposite system.

-

4.

The tribological evaluation revealed that specific wear rate increased with applied load, sliding velocity, and distance for all G–E + NC composites; however, organoclay reinforcement markedly mitigated this effect. Among all variants, G–E + NC-III consistently exhibited superior wear resistance, showing reductions of approximately 70–75% under high load, 66% at maximum sliding velocity, and 69% over sliding distance compared with the neat matrix. Further, at high sliding actions, G–E + NC-I, II, and IV exhibited thicker, unstable, and inconsistent films. These results confirm that uniformly dispersed organoclay platelets in G–E + NC-III significantly enhance interfacial strength, load-bearing capacity, and mechanical–tribological synergy.

-

5.

SEM analysis revealed that the dominant wear mechanisms involved debris formation, fiber fracture, matrix tearing, and transfer film evolution, all governed by sliding velocity, distance, and interfacial bonding. Organoclay incorporation promoted stable, uniform tribo-films that minimized fiber exposure and matrix degradation. Among all systems, G–E + NC-III exhibited outstanding wear resistance and interfacial integrity, demonstrating superior hardness and durable tribological stability under dynamic sliding conditions.

-

6.

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with Central Composite Design (CCD) successfully revealed that applied load was the most dominant factor influencing the specific wear rate of both G–E + NC-00 and G–E + NC-III composites, contributing 68.73% and 69.03%, respectively, followed by sliding velocity while sliding distance was statistically insignificant. Regression models exhibited strong correlations with experimental data (R2 = 96.4% for G–E + NC-00; 95.65% for G–E + NC-III) and minimal prediction errors ± 7%, confirming RSM’s accuracy and reliability for predicting and optimizing wear behavior.

-

7.

The study establishes NC-III organoclay as the most effective reinforcement for achieving superior hardness, optimized transfer film stability, and minimized wear loss. The integrated framework of morphological tailoring and statistical optimization provides both mechanistic insights and predictive tools for designing next-generation, wear-resistant polymer nanocomposites. These findings hold strong potential for applications in aerospace, automotive, marine, and structural engineering sectors requiring high-performance materials under demanding tribological conditions.

-

8.

The current investigation is limited to dry, short-term wear testing of the NC-III organomodified nanoclay composite; environmental factors such as humidity, elevated temperature, and cyclic loading which can markedly influence interfacial adhesion, matrix softening, and transfer film stability were not examined. Future research should therefore explore multi-scale modeling approaches, environmental conditioning effects, and long-term degradation behavior to more accurately predict performance under realistic service conditions.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Dash, S., Satpathy, M. P., Routara, B. C., Pati, P. R. & Gantayat, S. Enhancing mechanical and tribological performance of hybrid composites: an experimental study utilizing response surface methodology and firefly algorithm. Polym. Compos. 45, 15924–15940. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.28880 (2024).

Sahu, S. K. & Sreekanth, P. S. R. Evaluation of tensile properties of spherical shaped SiC inclusions inside recycled HDPE matrix using FEM based representative volume element approach. Heliyon 9, e14034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14034 (2023).

Sahu, S. K. & Sreekanth, P. S. R. Artificial neural network for prediction of mechanical properties of HDPE based nanodiamond nanocomposite. Polym. Korea. 46, 614–620. https://doi.org/10.7317/pk.2022.46.5.614 (2022).

Gowrishankar, M. C., Shettar, M., Somdee, P., Rangaswamy, N. & Chate, G. R. A review on mechanical, water-soaking, thermal, and wear properties of nanoclay-polyester nanocomposites. Discov. Mater. 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43939-025-00304-9 (2025).

Awasthi, T., Bharti, M. S., Agrawal, A. & Gupta, G. Experimental study of physical, mechanical and tribological behaviour of polyester/kota stone dust composite. Eng. Res. Express. 6, 045571. https://doi.org/10.1088/2631-8695/ad9b6e (2024).

El-meniawi, M. A. H., Mahmoud, K. R. & Megahed, M. Positron annihilation spectroscopy and mechanical properties studies for epoxy matrices reinforced with different nanoparticles. J. Polym. Res. 23, 181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10965-016-1074-6 (2016).

Dholi, A., Yadav, S., Agrawal, A. & Gupta, G. Development of epoxy/red stone dust composites and their characterization for light duty structural and automotive applications. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 39, 1737–1756. https://doi.org/10.1080/01694243.2025.2464879 (2025).

Mohan, T. P. & Kanny, K. Tribological studies of nanoclay filled epoxy hybrid laminates. Tribol. Trans. 60, 681–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402004.2016.1204039 (2017).

Xu, Z., Kong, W., Zhou, M. & Peng, M. Effect of surface modification of montmorillonite on the properties of rigid polyurethane foam composites. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 28, 615–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10118-010-9111-0 (2010).

Sharma, B., Mahajan, S., Chhibber, R. & Mehta, R. Glass fiber reinforced Polymer-Clay nanocomposites: Processing, structure and hygrothermal effects on mechanical properties. Procedia Chem. 4, 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proche.2012.06.006 (2012).

Megahed, A. A. E. W. & Megahed, M. Fabrication and characterization of functionally graded nanoclay/glass fiber/epoxy hybrid nanocomposite laminates. Iran. Polym. J. 26, 673–680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13726-017-0552-y (2017).

Mahesh, K. V. et al. The influence of montmorillonite on mechanical, thermal and fire retardation properties of vinylester/glass composites. J. Compos. Mater. 47, 2163–2178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021998312454902 (2013).

Nazir, M. S. et al. Characteristic Properties of Nanoclays and Characterization of Nanoparticulates and Nanocomposites 35–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1953-1_2 (2016).

Wang, M., Fan, X., Thitsartarn, W. & He, C. Rheological and mechanical properties of epoxy/clay nanocomposites with enhanced tensile and fracture toughnesses. Polym. (Guildf). 58, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2014.12.042 (2015).

Pati, P. R. Prediction and wear performance of red brick dust filled glass–epoxy composites using neural networks. Int. J. Plast. Technol. 23, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12588-019-09257-0 (2019).

Mohamed, Y. S., El-Gamal, H. & Zaghloul, M. M. Y. Micro-hardness behavior of fiber reinforced thermosetting composites embedded with cellulose nanocrystals. Alexandria Eng. J. 57, 4113–4119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2018.10.012 (2018).

Mrah, L. & Meghabar, R. Dispersion and improvement of organoclays in nanocomposites based on poly(propylene oxide). J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 35, 1889–1902. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892705720939172 (2022).

Rafiq, A. & Merah, N. Nanoclay enhancement of flexural properties and water uptake resistance of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy composites at different temperatures. J. Compos. Mater. 53, 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021998318781220 (2019).

Yi, H., Hu, M., Yao, D., Lin, H. & Zheng, B. Tribological and thermomechanical properties of epoxy-matrix nanocomposites containing montmorillonite nanoclay intercalated with polybutadiene-based quaternary ammonium salt. Plast., Rubber Compos. 49, 389–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/14658011.2020.1776921 (2020).

Reddy Paluvai, N., Mohanty, S. & Nayak, S. K. Effect of cloisite 30B clay and Sisal fiber on dynamic mechanical and fracture behavior of unsaturated polyester toughened epoxy network. Polym. Compos. 37, 2832–2846. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.23480 (2016).

Mohammed, A. S., Ali, A. & bin, Nesar, M. Evaluation of tribological properties of organoclay reinforced UHMWPE nanocomposites. J. Tribol. 139. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4033188 (2017).

Dorigato, A., Morandi, S. & Pegoretti, A. Effect of nanoclay addition on the fiber/matrix adhesion in epoxy/glass composites. J. Compos. Mater. 46, 1439–1451. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021998311420311 (2012).

Dos Santos, E. P., Fook, M. V. L., Malta, O. M. L., De Lima Silva, S. M. & Leite, I. F. Role of surfactants in the properties of Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate)/Purified clay nanocomposites. Materials 11, 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11081397 (2018).

Ozsoy, I., Mimaroglu, A. & Unal, H. Influence of micro- and nanofiller contents on friction and wear behavior of epoxy composites. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 24, 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1515/secm-2014-0262 (2017).

Moosa, M. H. et al. Structural and tribological characterization of carbon and glass fabrics reinforced epoxy for bushing applications safety. Polym. (Basel) 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15092064 (2023).

Murugan, A. et al. Optimization of tribo-mechanical properties of kenaf/jute-SiC hybrid composites using integrated grey-fuzzy approach. Sci. Rep. 15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11340-z (2025).

Ibrahim, M. A., Çamur, H., Savaş, M. A. & Abba, S. I. Optimization and prediction of tribological behaviour of filled polytetrafluoroethylene composites using Taguchi Deng and hybrid support vector regression models. Sci. Rep. 12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14629-5 (2022).

Shettar, M., Bhat, A. & Katagi, N. N. Estimation of mass loss under wear test of nanoclay-epoxy nanocomposite using response surface methodology and artificial neural networks. Sci. Rep. 15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05263-y (2025).

Shettar, M., Kowshik, C. S. S., Manjunath, M. & Hiremath, P. Experimental investigation on mechanical and wear properties of nanoclay-epoxy composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9, 9108–9116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.06.058 (2020).