Abstract

Mango (Mangifera indica L.) is a globally significant tropical fruit crop, widely cultivated across South and Southeast Asia, with Pakistan recognized as a major center of production and varietal diversity. However, the genetic potential of mango in Pakistan remains underutilized due to limited morphological characterization of its diverse germplasm. This study assessed the morphological diversity of 89 Mangifera indica L. genotypes at the Mango Research Station (MRS), Shujabad, Pakistan. The germplasm included indigenous varieties, hybrids, and exotic genotypes originated from diverse eco-geographical regions. A total of 43 qualitative and 14 quantitative traits related to tree, leaf, inflorescence, fruit, and stone were recorded and analyzed. The Shannon–Weaver diversity index indicated high variability in traits such as canopy shape, young leaf color, fruit shape, blush color (ripe and unripe), and stone fiber texture. Quantitative traits including fruit weight, stone weight, tree height, and trunk diameter exhibited high diversity with a coefficient of variation exceeding 35%. Significant differences were observed among genotypes for all the quantitative traits. Some of the promising genotypes were identified for commercial cultivation and breeding initiatives. Correlation analysis helped to identify associations among key traits, facilitating the selection of superior germplasm for breeding. Principal component analysis revealed four principal components for quantitative traits and seventeen for qualitative traits, each with eigenvalues greater than 1, contributed over 75% of the total variation. Cluster analysis grouped genotypes into five clusters based on quantitative traits and six clusters based on qualitative traits, reflecting both geographical origin and morphological similarities. This study highlights the rich phenotypic diversity of a large collection of mango germplasm in Pakistan and provides valuable insights for its conservation, genetic improvement, and sustainable utilization in future mango breeding programs in the region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mango (Mangifera indica L. 2n = 2x = 40), a juicy drupe from the family Anacardiaceae and regarded as the “king of fruits” in many cultures. It is the most attractive and economically important evergreen fruit tree cultivated in more than 90 countries of the tropical and sub-tropical regions of the globe particularly in Asia1,2. The domestication of mango started in the Indo-Burmese and Southeast Asia regions 4000 years ago, and mango began spreading to other parts of the world in the fourteenth century3,4,5. Mango is considered the most popular fruit consumed, containing rich nutritional compounds such as carbohydrates, lipids, and fatty acids, proteins, organic acids, vitamins, minerals, and bioactive compounds. Apart from its consumption as a fruit, it is also used in traditional medicine to treat several common diseases6,7. Mango accounts for the fifth-largest fruit production in the world after banana, apple, orange, and grape and provides an average yield of about 9 tons per hectare1. Mango production at global level has increased since 2010, reaching 47.13 million tons in 20208,9.

Mango is the national fruit of Pakistan, with production volumes reaching 1.72 million tons (MT) from an area of 168.6 thousand hectares, making it the second most produced and valuable fruit in the country, following citrus production10. It is valued for its vibrant colors, enticing aroma, soothing taste, and high nutritional value11,12. Pakistan is the world’s fifth largest producer of mango just after India, China, Thailand and Indonesia and represents 4.5% of the global production of mangoes13. Among the four provinces of Pakistan, the Southern Punjab and Sindh regions of Pakistan have ideal soil and climatic conditions for mango cultivation and together contribute the largest share of the country’s mango production. While mangoes are grown in other regions as well, these two remain the primary production zones14. Around 250 mango varieties have been reported in Pakistan with commercially produced varieties including Chaunsa, Dusehri, Anwar Ratole, Fajri, Sindhri and Langra15,16. Sindhri, Sufaid Chaunsa and Samar Bahisht Chuansa mango varieties are currently being exported to the United States, European Union, Middle East and Southeast Asia17,18.

Mango has been reported to have extensive diversity in its genotypes due to alloploidy, outbreeding, and phenotypic variation arising from varied agro-climatic conditions in different mango-growing regions5,19,20. Mango is a typical open-pollinated fruit tree, and many of its varieties have originated through hybridization, seedling selection, and natural mutations. However, the pedigree and genetic relationships among these varieties remain poorly documented, with limited information on their exact parentage and domestication history21,22,23. In Pakistan, several mango genotypes with a high breeding potential are now endangered due to a combination of biotic and abiotic stresses, poor orchard management, limited cultivar identification, fruit fly infestation and a narrow range of commercial cultivars. These challenges pose a significant threat to mango genotypes, resulting in lower yields and export volumes24,25. Therefore, the systematic collection, identification, and characterization of germplasm resources are essential steps toward evaluating population diversity. This will facilitate the identification of promising genotypes that can contribute to the development of more resilient and productive mango cultivars through breeding programs26,27,28.

The most critical step in any breeding program is the screening and identification of superior genotypes. Genetic diversity plays a pivotal role in the success of breeding efforts; therefore, recognizing and quantifying this diversity along with understanding its nature and magnitude is essential. The initial step in characterizing genetic resources and integrating them into the production system involves morphological assessments, which provide valuable insights into phenotypic diversity29. Evaluating the extent of genetic diversity using both qualitative and quantitative morphological traits helps in exploiting the existing variation among mango genotypes. Consequently, assessing phenotypic diversity and estimating the heritability of key traits are vital for identifying potential parental materials and selecting high-yielding genotypes26,30. Although the evaluation of morphological traits can be labor-intensive and time-consuming, these descriptors offer a simple, direct, rapid, and cost-effective means of assessing genetic variation, making them valuable tools for large-scale screening in mango breeding programs.

Numerous studies have been conducted on the morphological characterization of wild and cultivated mango genotypes in different parts of the world1,19,31,32. However, mango germplasm in Pakistan has not been subjected to intensive breeding efforts, primarily due to the limited availability of phenotypic and genetic diversity data. To date, only a few cultivars have been evaluated for morphological variation, and no study has comprehensively assessed a large germplasm set under uniform conditions. To the best of our knowledge, no published work has provided a detailed qualitative and quantitative morphological characterization of the extensive mango collection maintained at the Mango Research Station (MRS), Shujabad, Pakistan. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to characterize mango genotypes based on key morphological traits to assess the extent of phenotypic variability and identify traits with the highest diversity. The findings of this study provide a valuable foundation for mango improvement programs in Pakistan by identifying promising genotypes with desirable phenotypic traits. Furthermore, the research will contribute to the future breeding programs, conservation efforts, and the sustainable development of mango production in the region.

Materials and methods

Description of study site

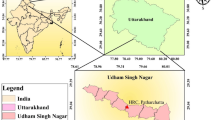

The study was conducted at the Mango Research Station (MRS), Shujabad, Pakistan, during two consecutive mango growing seasons in 2022 and 2023. MRS Shujabad, established in 1972–73 by the Government of Punjab, maintains a diverse collection of mango germplasm from various eco-geographical regions of the globe (Fig. 1). Shujabad (30.2°N lat, 71.5°E long) is located 45 km south of Multan at an elevation of 122 m above sea level. The average annual temperature is approximately 25.5 °C. June tends to be the hottest month, with average highs reaching 46 °C, while January is the coldest, with average lows around 4.5 °C. The normal annual precipitation measures approximately 186 mm, with the majority occurring during the monsoon season (July to September). The soil at the experimental site is predominantly sandy loam, slightly acidic, with a pH around 6.0. Standard horticultural practices, including fertilizer application, spraying, irrigation, and other cultural practices were performed at regular intervals each year to maintain orchard health and productivity.

Plant material

The plant materials evaluated in this study were composed of 89 Mangifera indica L. genotypes, accompanied by their respective passport details as presented in Table 1. The germplasm panel consisted of commercially important cultivars, landraces, hybrids and exotic genotypes, composed of both monoembryonic and polyembryonic types. Genotypes were selected to capture maximum morphological diversity and were evaluated under uniform conditions. The data were collected from five fully matured and healthy trees that were free of pests and disease symptoms, had straight, circular stems of large diameter, and well-spread horizontal branches for each genotype. For quantitative traits, three replicates were recorded from each tree for all genotypes, and the mean values were used for further analysis.

Traits evaluation

A total of 57 morphological traits (grouped into two categories, i.e. qualitative and quantitative) were evaluated across 89 mango (M. indica L.) genotypes in this study. The data for both sets of traits was collected as per the previous reports of mango descriptors provided by International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI 2008) and Federal Seed Certification and Registration Department (FSC&RD), Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Livestock, Government of Pakistan Islamabad (http://www.federalseed.gov.pk/). Some of the additional fruit related descriptors were recorded in accordance with the Queensland Department of Primary Industries protocols (personal communication). For qualitative traits, data was recorded from five plants per genotype using scoring-based observations, whereas quantitative traits were measured on five plants per genotype, with five samples (trees/leaves/inflorescence/fruits/stones) per plant, and the average value was calculated for analysis. The data gathered were organized in a matrix for subsequent analysis with Microsoft Excel 2010 software (https://www.microsoft.com).

Qualitative characterization

This characterization was based on a total of 43 traits of tree, leaf, inflorescence, fruit and stone of M. indica L. germplasm. For qualitative traits, the surveys were based on direct observations, with a pre-defined scale for each trait (Supplementary Table S1). Plant architectural traits were visually evaluated in the field. Leaf traits were measured from fully expanded, healthy, undamaged and well developed (mature) leaves. Leaf color was also observed during the field evaluation. Inflorescence trait was evaluated during the flowering season (January to march). Phenotypic data on fruits were collected at horticultural maturity and ripe fruit stages (Supplementary Table S1).

Quantitative characterization

Fourteen quantitative traits were measured using standard protocols and instruments, covering tree, inflorescence, leaf, fruit, and stone characteristics. Tree-related measurements were recorded using a measuring tape to ensure accuracy. Inflorescence and leaves traits were determined through direct measurement using a digital caliper to maintain precision. Fruit and stone related traits were also recorded using digital calipers and precision balances. A comprehensive table (Supplementary Table S1) provides detailed information on the trait names, codes, units of measurement, and the scales used for assessment.

Statistical nalysis

Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) was employed for the initial data organization and to create bar graphs for the visualization of the qualitative traits across the 89 mango genotypes. To examine the distribution of quantitative traits, histograms were constructed using IBM statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) statistics (version 21.0). A series of univariate and multivariate analysis for qualitative and quantitative data was performed using R Studio (version 4.4.2)33. The summary function was used to obtain descriptive statistics34, while analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out using the aov function to compare means across different groups of genotypes for each quantitative trait. For the Shannon-Weaver diversity index (H′) calculation for qualitative traits, the “vegan” package35 was utilized in R. The formula R uses to calculate the Shannon-Weaver Diversity Index is:

H′=−∑(pi⋅ln(pi))36.

-

pi is the proportion of individuals in the i-th category of the trait (i.e., the relative frequency of each trait category within the genotypes).

-

ln(pi) is the natural logarithm of pi.

According to Eticha et al.37 the Shannon-Weaver diversity index (H’) was categorized into three levels: low diversity (0.10 ≤ H’ ≤ 0.40), intermediate diversity (0.40 < H’ c ≤ 0.60), and high diversity (H’ > 0.60).Pearson correlation analysis was carried out using the cor function in R to examine the strength and direction of the linear relationships between morphological traits38. A significance threshold of 0.05 was applied to assess the correlations. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed in R using the prcomp function to reduce the dimensionality of the data and to identify patterns and relationships between the mango genotypes based on their phenotypic traits39. The R packages “ggplot2”, “Factoextra”, and “FactomineR”, were used to create the PCA-biplot40,41. Hierarchical clustering of genotypes based on the similarity of their phenotypic traits was performed using the hclust function in R42. The results were visualized using dendrograms to better understand the relationships among the genotypes.

Results

Morphological diversity of Mango genotypes

This study was based on 57 morphological traits including 43 qualitative and 14 quantitative. Some of the morphological traits recoded for tree, leaf and inflorescence along with variation in blush color, fruit shape and size have been presented in Fig. 2.

Morphological variability in some of the traits of tree, leaf, inflorescence and fruits. Tree shapes (a) circular (b) semi-circular (c) oblong (d) broadly pyramidal (e) pyramidal. Young leaf color (f) light green (g) brownish green (h) crimson red (i) yellowish green (j) light brown (k) dark brown. Leaf shapes (l) elliptic (m) ovate (n) oblong. Flower and inflorescence shapes (o) mango panicle (p) conical (q) pyramidal (r) broadly pyramidal. Ripened mango fruit shapes and blush color (s) local genotypes (t) hybrid genotypes (u) exotic polyembryonic (v) exotic genotypes.

Characterization based on qualitative traits

Qualitative traits from tree, leaf, inflorescence, fruit and stone were evaluated based on percentage frequency and Shannon weaver diversity index (H’) for each trait (Table 2). Four morphological tree architecture traits were recorded. Three sub-characters were observed as main branch attitude, 44 genotypes showed a spreading habit, followed by 42 genotypes with erect characteristics and only 3 genotypes with a drooping habit (Supplementary Fig. S1). Five canopy shape types such as circular, semi-circular, oblong, pyramidal and broadly pyramidal were observed in this study. Of which 33.7% genotypes had oblong canopy shape, followed by broadly pyramidal (28.1%), pyramidal (18.0%), circular (12.4%) and semi-circular (7.9%) (Table 2). Four branching patterns were recorded (Supplementary Fig. S1). Among 89 genotypes, 46 genotypes showed a basal type of branching pattern (51.7%), 25 genotypes showed an intermediate branching pattern (28.1%), and 5 genotypes showed a top branching pattern (5.6%). Foliage density varied from sparse to medium to dense. Dense foliage density was found to be dominated among the genotypes (57.3%) followed by medium (38.2%) and sparse (4.5%) (Table 2).

A high-level diversity was observed in eleven leaf qualitative characters among 89 genotypes (Supplementary Fig. S2). Three types of leaf shapes such as elliptic, ovate, and oblong were recorded in this study (Fig. 1). More than half of the genotypes (51.7%) had an elliptic shape while rest of the genotypes had ovate (31.5%) and oblong (16.9%) leaf shape (Table 2). Wide range of variability was observed in the young leaf color. Six different colors of young leaves were recorded (Fig. 1). The largest number of genotypes showed light green (52 genotypes) followed by light brown (16 genotypes), brownish green (8 genotypes), dark brown (5 genotypes), yellowish green (4 genotypes) and crimson red (4 genotypes) color (Supplementary Fig. S2). Mature leaf color was only characterized into two types such as dark green and light green. Green color predominated, comprising 56.2%, over dark green. Three types of leaf tip shapes were identified in the evaluated germplasm, where attenuate (50.6%), acute (29.2%), and acuminate (20.2%) leaf tip shapes constituted the significant variations. Most of the genotypes (53) showed acute leaf base shape followed by obtuse (35) and rounded (1). Leaf curvature of midrib was absent in most of the genotypes as of 70.8% while present in remaining genotypes (29.2%). Leaf shape in cross section was straight in 63 genotypes while the rest had concave shape in cross section. The leaf attitude was characterized as horizontal (56.2%) and drooping (43.8%). The leaf fragrance was present in 83 genotypes and absent in the remaining 6 genotypes. Leaf margin was entire in more than half of the genotypes (74.2%), while the rest (25.8%) had wavy types of leaf margin. Leaf relief of upper surface was smooth in 33 genotypes and raised in 56 genotypes.

A wide variation was observed in five inflorescence characters among different genotypes (Supplementary Fig. S3). Three distinct inflorescence shapes were identified in the evaluated germplasm, with conical being the most dominated (53.9%), followed by pyramidal (31.5%), and broadly pyramidal (14.6%) shapes, which contributed to the significant variation observed (Table 2). In terms of rachis and branch color, 40 genotypes displayed Pinkish green color, while the remaining genotypes exhibited a variety of colors: purple (18 genotypes), green (16 genotypes), Light pink (9 genotypes) and yellowish green (6 genotypes) (Supplementary Fig. S3). Regarding flower density, intermediate (55.1%), dense (28.1%) and sparse (16.9%) types were recorded among the studied mango germplasm (Table 2). Significant diversity in petal color was observed, with five distinct types identified i.e. Yellow, Yellow with white patches and Yellow with pink patches, which accounted for 25.8%, 28.1%, and 21.3% of the total variation. The remaining genotypes exhibited either Pink with white patches or pink contributing 4.5% and 20.2% of the total variation (Table 2). Pubescence on main axis was also recorded as absent (66.3%), mild (33.7%) and no genotype showed strong pubescence (Table 2).

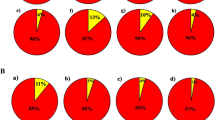

Fruit traits were divided into morphological and sensory quality traits (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S4 and S5). In the present study, a wide variation was observed in fruit shapes among the genotypes. Thirty-seven had ovate round and thirty had ovate elongate fruit shapes. Ovate shape was observed in eleven genotypes. There were nine genotypes with elongate and two genotypes showed round fruits among the fruit shapes. Prominent beak shape was observed in eight genotypes followed by very slight (24), and slight (28) beak shape. Rest of the 21 genotypes had medium beak shape and it was absent in eight genotypes. Stem end shape was characterized as sunken (3.4%), slightly depressed (16.9%), leveled (32.6%), slightly raised (44.9%), and pointed (2.2%). Density of lenticels on skin varied among the genotypes. It was classified into three groups: sparse, medium and dense. Among the genotypes, 44 had medium density of lenticels on skin, 26 genotypes had dense lenticels on the fruit skin while remaining 19 had sparse density of lenticels (Table 2). Size of lenticels was observed as small in 42 genotypes, medium in 33 genotypes and large in 14 genotypes. Fruit skin texture was smooth in most of the genotypes (51) and rough in 38 genotypes. Variation was observed among the genotypes in terms of fruit stalk cavity. Among them, 47.2% exhibited no fruit stalk cavity, 38.2% had a shallow cavity, and 14.6% displayed a medium fruit stalk cavity. Fruit neck and its prominence were classified as absent in 30 genotypes, weak in 27 genotypes, medium in 29 genotypes and strong in only 3 genotypes. Five main types of mature fruit shoulder: rounded upward, rounded outward, rounded downward, sloping downward and falling abruptly were recorded from the exp. Thirty-seven genotypes showed rounded upward fruit shoulder whereas thirty-one showed rounded outward. Rest of the eight genotypes had rounded downward fruit shoulder and nine genotypes had sloping downward fruit shoulder. Only four genotypes had falling abruptly fruit shoulder (Supplementary Fig. S4). Groove in left shoulder of the fruit was absent in most of the genotypes (80.9%), while the rest (19.1%) had groove in their left shoulder. Fruit sinus was present in 59 genotypes and absent in the remaining 30 genotypes. Results of sensory fruit quality assessment were summarized in Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S5. Among the 9 blush colors of unripen fruits observed, most of the genotypes (59.6%) showed no blush color at the unripen stage, 15.7% of genotypes had yellow blush color while pinkish red and purple blush colors were shown by 6 genotypes each. Orange and red blush color were shown by 5 and 3 genotypes respectively and only 2 genotypes showed pink blush color. Two blush colors, bronze and burgundy were not found in any of the genotypes. The blush color for ripened fruits was also recorded. Among seven evaluated blush colors, 34 genotypes had no blush color, 21 genotypes showed yellow blush color, orange blush color was shown by 11 genotypes, pinkish red and red were shown by 10 and 8 genotypes respectively and only 5 genotypes showed burgundy blush color. Pink blush color was not shown by any genotypes. The intensity of blush color in ripened fruits was also recorded in six different categories: very strong (3.4%), strong (7.9%), medium (24.7%), low (20.2%), very low (6.7%), and no blush (37.1%) in Table 2. Fruit fiber quality varied among genotypes. It was classified into five groups: very low, low, medium, high, very high. Among the genotypes, 45 had low fruit fiber quality, which was 50.6% of the total variation (Table 1). Medium fruit fiber quality was observed in 28 genotypes (31.5%). High fruit fiber quality was also recorded in 7 genotypes (7.9%). Only 2 genotypes (2.2% of total) showed very high fruit fiber quality. Fuit fiber strength was evaluated as very weak (10.1%), weak (43.8%), medium (41.6%), strong (4.5%), and very strong (no genotypes). Variation was observed among the genotypes for flesh firmness of fruit. 46.1% of genotypes had firm flesh followed by medium flesh firmness (31.5%), whereas 19.1% of genotypes had soft flesh. Only 2.2% and 1.1% of the genotypes had very firm and very soft flesh respectively (Table 2). Most of genotypes (45) showed yellow fruit flesh color, while 32 genotypes produced orange flesh color and 8 showed orange yellow color. The remainder of the four genotypes showed dark orange and light yellow fruit flesh color. Fruit juiciness was grouped into five different categories: medium (19 genotypes), juicy (35 genotypes), medium to juicy (33 genotypes), medium to dry (1 genotype) and dry (1 genotypes) as shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.

Variation among four stone characters was also observed among the 89 genotypes (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S6). There were three types of stone shapes such as reniform, oblong and ellipsoid were recorded. Most dominant seed shape was oblong (82%) followed by ellipsoid (13.5%) and reniform (4.5%) (Table 2). Pattern of venation on stone was characterized as parallel and forked. Sixty-four genotypes had forked venation, while the rest had parallel type of venation of the stone. Fiber texture on the stone surface varied from fine (44.9% of the genotypes), to coarse (32.6% of the genotypes) and medium (22.5% of the genotypes). Stone fiber density was medium in most genotypes (48.3%), followed by sparse (30.3%) and dense (21.3%) (Table 2).

Characterization based on quantitative traits

The evaluated mango germplasm exhibited substantial variability in quantitative morphological traits. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed significant differences (p < 0.05) as evident from the mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variations (CV) among the genotypes for all the studied quantitative traits (Table 3; Fig. 3). The mean values for all the quantitative traits were presented in Supplementary Table S2. The coefficient of variation (CV%) ranged from 14.6% to 49.3%. The traits such as trunk diameter (49.3%) and fruit weight (44.3%) had high CV values, the trait stone length (30.7%) had a medium CV value, and the rest of the traits showed lower CV values. The least coefficient of variation (14.5%) was observed in stone width. Significant variations were found among mango genotypes for tree height and trunk diameter. Tree height ranged from 1088.39 cm to 269.44 cm with an average of 573.35 cm. The highest tree height recorded in Saroli and the lowest in Palmer genotypes. The highest trunk diameter was recorded in Chaunsa (Rampuri), and the lowest was in Palmer (Table 3). The leaf length ranged from 29.77 cm to 10.47 cm with an average of 19.27 cm, SD was 3.70, and CV was 19.2%. The highest leaf length was recorded in Xoai Cat Hoa Loc, and the lowest in Shah Pasand. The leaf width was also measured ranging from 7.97 cm (Badia Muna Syed) to 2.53 cm (Bangan palli) with an average of 5.06 cm, SD was 1.17, and CV was 22.8% (Table 3). Highest petiole length (5.33 cm) was observed in Spring fells and lowest was 1.13 cm in Bangan palli. Panicle length and width were also recorded in all genotypes, and the mean value was 27.65 cm and 16.06 cm, respectively. Four different fruit quantitative traits such as fruit length, width, thickness and weight were also recorded and fruit weight showed highest CV values with significant variation. The average fruit length was 10.61 cm, ranging from 18.27 cm to 6.07 cm, SD was 2.44, the average fruit width was 7.01 cm, ranging from 11.43 cm to 4.47 cm. The highest fruit width and thickness were recorded in R2E2, while the lowest fruit length, thickness and weight was observed in Sapa. Rupee variety showed the maximum fruit weight and fruit length while Sapa showed the lowest among all genotypes (Table 3). Three seed quantitative traits showed significant differences (Fig. 3). The average stone length was 7.34 cm with CV 30.8% and stone width was 3.37 cm with CV 14.6% (Table 3). The lowest stone length was recorded in Sobe de ting and Langra, while the highest was observed in Maha-165 and Pope genotypes, respectively. While considering stone weight, the mean was found to be 39.81 g with the range of 81.80 g to 15.43 g, SD was 14.38, and CV was 36.1%. The lowest stone weight was found in Sapa, and the highest was observed in Sufaid Chaunsa (Table 3).

Identification of promising genotypes with desirable traits

Based on the characterization of qualitative and quantitative traits, A subset of key fruit traits i.e. fruit blush color, blush intensity, fruit weight, fruit flesh color, flesh firmness, juiciness and fruit fiber quantity were used to assess genotype performance and elite genotypes were identified possessing desirable fruit traits. These key traits selected were based on consumer preference and breeding objectives. Table 4 summarizes all the desirable traits and the genotypes selected for their superior performance across these traits.

Correlation analysis

Bivariate correlation analysis of qualitative descriptors

The correlation analysis revealed several positive and negative relationships among 43 qualitative traits. A heat map showing the correlation among traits is presented in Fig. 4A and the complete set of r values for all trait pairs are shown in Supplementary Table S3 in which statistically significant correlations (p ≤ 0.05) are bolded, and the positively correlated r values are highlighted with green and negatively correlated are highlighted with yellow color. The results indicate that branching pattern was strongly correlated with canopy shape (r = 0.31). Leaf base shape was positively associated with leaf shape (r = 0.3), and leaf attitude towards main branch was correlated with Leaf shape in cross section (r = 0.33). Size of lenticels was strongly correlated with density of lenticels on the skin (r = 0.34), and fruit neck and prominence of neck showed a strong relationship with stem end shape (r = 0.51) and beak shape (r = 0.32). Groove in left shoulder was strongly correlated with stem end shape (r = 0.38). Blush color ripe showed a strong relationship with blush color unripe (r = 0.48) and Blush intensity ripe showed the strongest relationship among all with blush color ripe (r = 0.82). Flesh fiber strength is strongly associated with flesh fiber quantity (r = 56). Fiber texture is positively linked to blush color ripe (r = 0.3), while fiber density was strongly linked with fiber texture (r = 0.41). In addition to the strong correlations discussed above, several moderate but statistically significant positive associations (r ≥ 0.21 and p ≤ 0.05) were also observed among qualitative traits presented in detail in Supplementary Table S3 and highlighted in green. On the other hand, negative correlations (highlighted with yellow in Table S3) were also observed between several traits. These include canopy shape correlating with main branch attitude (r = − 0.44), foliage density correlating with branching pattern (r = − 0.36), and young leaf color correlating with branching pattern (r = − 0.32). Leaf base shape showed a negative correlation with main branch attitude (r = − 0.36). Leaf attitude towards main branch was negatively correlated with leaf curvature of midrib (r = − 0.33). Color of petals was negatively associated with branching pattern (r = − 0.31), fruit shape had negative correlations with flower density (r = − 34). Fruit stalk cavity showed negative relationships with stem end shape (r = − 0.36), mature fruit shoulder was negatively correlated with Inflorescence shape (r = − 0.31). Fruit Sinus had a negative relationship with beak shape (r = − 0.47), Fruit stalk cavity (r = − 0.44) and fruit neck and prominence of neck (r = − 0.31). Flesh firmness was negatively associated with flesh fiber strength (r = − 0.42) and stone shape had negative correlations with fruit sinus (r = − 33). Rest of the moderate but statistically significant negative associations (r ≥ − 0.21 and p ≤ 0.05) were also observed among qualitative traits presented in detail in Supplementary Table S3 and highlighted in yellow.

Pearson Coefficient Correlation (Bivariate correlation) of the traits among 89 mango genotypes. A: Heat map for 43 qualitative traits. B: Heat map for 14 quantitative traits. Green indicates a positive relationship, while red indicates a negative relationship. Size of the circle represents the degree of the correlation and circle with * indicates the r values which are significant at p ≤ 0.05. For the correlation (r-values and statistical significance (p-values) values for each bivariate relationship please refer to supplementary information (Supplementary Table S3 and S4).

Bivariate correlation analysis between quantitative descriptors

This bivariate correlation analysis revealed several relationships between the 14 quantitative traits (Fig. 4B). The full set of r values for all trait pairs is presented in Supplementary Table S4. A strong positive correlation was observed between tree height and tree diameter (r = 0.82). Additionally, several strong positive and significant correlations were identified, including those between leaf width and leaf length (r = 0.80), petiole length with leaf length (r = 0.4), and leaf width (r = 0.34). Panicle width length was positively associated with panicle length (r = 0.55), while fruit width was strongly associated with fruit length (r = 0.62). Fruit thickness was positively correlated with fruit length (r = 0.55), and fruit width (r = 0.91). Fruit weight showed positive relationship with leaf length (r = 0.3), fruit length (r = 0.78), fruit width (r = 0.78), and fruit thickness (r = 0.72). Stone length is strongly associated with fruit length (r = 0.82), fruit width (r = 0.43), fruit thickness (r = 0.34) and fruit weight (r = 0.65). Stone width is positively correlated with fruit length (r = 0.51), fruit width (r = 0.56), fruit thickness (r = 0.49) fruit weight (r = 0.5) and stone length (r = 0.53). Lastly, stone weight was associated with several other traits such as fruit length (r = 0.68), fruit width (r = 0.69), fruit thickness (r = 0.62) fruit weight (r = 0.88), stone length (r = 0.63) and stone width (r = 0.55). On the contrary, two negative yet significant correlations were observed i.e. stone length with tree height (r = − 23) and trunk diameter (r = − 23). All the remaining moderate yet significant (r ≥ 0.21 and p ≤ 0.05) associations were presented in supplementary Table S4 highlighted with green.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed for both qualitative and quantitative morphological traits to discover the distinct factors/components strongly impacting the comprehensive indicators.

PCA analysis of the qualitative morphological traits

Principle component analysis (PCA) of qualitative traits yielded 43 principal components (PCs), with the first 17 PCs explaining a substantial portion of the total variance and had eigenvalues greater than one. The eigen vector value for each trait, eigen values, contribution rate to variability, and cumulative contribution rate are presented in Supplementary Table S5. The first principal component (PC1) accounted for 8.0% of the total variance, followed by PC2 (7.2%), and PC3 (6.7%). Together, the first 17 PCs explained 75.4% cumulative variance, indicating that these components capture most of the essential variation within the dataset. The eigenvalues for Principal Components (PCs) 1 to 17 ranged from 1.86 to 1.02. The variance explained by first ten principal components were illustrated in the scree plot (Fig. 5A) The PCA biplot for PC1 and PC2 based on traits revealed distinct clustering patterns among the genotypes, suggesting variation in traits (Fig. 5B). The color gradient (cos² values) indicated the quality of representation of each trait on the factorial plane, with darker tones signifying stronger contributions. Several traits, including blush color ripe, blush color unripe, blush intensity ripe and color of rachis and branches and were positioned furthest from the origin, indicating a strong influence on PC1 and PC2. On the other hand, traits like pubescence on main axis, fruit shape, and fruit skin texture showed moderate to weak contributions, as indicated by their proximity to the origin and lighter cos² values. The additional supporting PCA results, and group distribution patterns (genotype by trait biplot) for qualitative traits were shown in Supplementary Fig. S7.

Principal component analysis of 43 qualitative traits (A) Proportion of variance (%) of top 10 principal components (PCs) and (B) PCA biplot of first two Principal Components (PCs) showing contributions of qualitative traits (MBA: Main branch attitude, CS: Canopy shape, BP: Branching pattern, FoD: Foliage density, LS: Leaf shape, YLC: Young leaf color, MLC: Mature leaf color, LTC: Leaf tip shape, LBS: Leaf base shape, LCM: Leaf curvature of midrib, LSCS: Leaf shape in cross section LA: Leaf attitude towards main branch, LF: Leaf fragrance, LM: Leaf margins, LR: Leaf relief of upper surface, IS: Inflorescence shape, CRB: Color of rachis and branches, FD: Flower density, PC: Color of petals, PMA: Pubescence on main axis, FS: Fruit shape, BS: Beak shape, SES: Stem end shape, DLS: Density of lenticels on skin, LeS: Size of lenticels, FST: Fruit skin texture, FSC: Fruit stalk cavity, FPN: Fruit neck and prominence of neck, MFS: Mature fruit shoulder, GLS: groove in left shoulder, FSi: Fruit sinus, BCU: Blush color unripe, BCR: Blush color ripe, BIR: Blush intensity ripe, FFQ: Flesh fibre quantity, FFS: Flesh fibre strength, FF: Flesh firmness, FFC: Fruit Flesh color, FJ: Fruit juiciness, SS: Stone shape, VP: Pattern of venation, FiT: Fiber texture, FiD: Fiber density).

PCA analysis of the quantitative morphological traits

The results of PCA showed that only the first four principal components (PC1, PC2, PC3, and PC4) significantly contributed 75.3% of the total variation and had eigenvalues > 1 in quantitative morphological traits across all mango genotypes (Fig. 6A and Supplementary Table S6). PC1 accounted for the highest variance (36.7%), followed by PC2, PC3, and PC4, which explained 16.4%, 13.5%, 8.7% of the total quantitative morphological variation, respectively (Fig. 6A). The information for the first four components was presented in Supplementary Table S6. PCA of quantitative traits revealed that fruit length, fruit width, fruit thickness, fruit weight, seed length, seed width and seed weight had strongly loadings on the PC1, with values ranging from 0.3 to 0.4. This suggests that PC1 is primarily associated with fruit and stone traits. This component was positively contributed by all variables except tree height, trunk diameter and petiole length (Supplementary Table S6). PC2 was positively contributed by tree height, trunk diameter, leaf length, leaf width, petiole length, panicle length and panicle width as the higher loading factors (0.21–0.43) but negatively loaded to fruit and stone traits indicating that PC2 as the main contributing factor for tree, inflorescence and leaf traits. Overall, PC1 and PC2 constituted 36.7% and 16.4% respectively of the total quantitative morphological variations. The PCA-biplot was created using the first two PCs, which together accounted for 53.1% of the total variability (Fig. 6B). The additional supporting PCA results, and group distribution patterns (genotype by trait biplot) for quantitative traits were shown in Supplementary Fig. S8.

Principal component analysis of 14 quantitative traits (A) Proportion of variance (%) of top 10 principal components (PCs) and (B) PCA biplot of first two Principal Components (PCs) showing contributions of quantitative traits (TH: tree height, TD: trunk diameter, LL: leaf length, LW: leaf width, PeL: petiole length, PL: panicle length, PW: panicle width, FL: fruit length, FW: Fruit width, FT: Fruit thickness, FWe: fruit weight, SL: Stone length, SW: stone width, SWe: stone weight).

Agglomerative hierarchical clustering (AHC) analysis

The 89 mango varieties were classified hierarchically based on their qualitative traits. These traits clustered genotypes into six clusters namely I, I, II, III, IV, V and VI with similar characteristics. Each cluster was represented by a specific color to differentiate them from one another (Fig. 7). Cluster I and II contained 7 and 6 genotypes respectively, containing lowest number of genotypes. Cluster III had 16 genotypes. All these three clusters comprised mostly of exotic genotypes. Cluster IV had the largest number of genotypes mostly from the local germplasm. Cluster V and VI were comprised of 15 and 12 genotypes representing most of the exotic germplasm. Hybrid genotypes were clustered in II, IV and V clusters based on qualitative traits.

The 89 genotypes were distributed across five clusters, each representing genotypes with similar quantitative morphological traits (Fig. 8). Cluster mean values for all five clusters of 14 quantitative characters were presented in Supplementary Table S8. The cluster I comprised of 11 genotypes, characterized by moderate tree height (478.30 cm) and trunk diameter (91.10 cm). The genotypes in this cluster also showed lowest leaf length (15.81 cm), leaf width (4.17 cm), petiole length (2.13 cm), panicle length (25.64 cm) and panicle width (14 cm). With 18 genotypes, Cluster II displayed the highest tree height (833.8 cm). Despite its strong vegetative growth, the genotypes in this cluster had relatively lower fruit weight (218.21 g). The cluster III, consisting of 19 genotypes, exhibited the highest fruit weight (492.95 g) and fruit length (13.11 cm), as well as the largest stone length (9.55 cm) and highest stone weight (58.67 g). Cluster IV, the largest group with 23 genotypes, exhibited substantial tree height (680 cm) and highest trunk diameter (165.87 cm). The genotypes in this cluster also showed a balanced combination of vegetative and reproductive traits, with relatively high fruit weight (322.07 g). The last cluster V, with 18 genotypes, displayed the lowest tree height (450.9 cm) and lowest fruit thickness (5.28 cm) among all clusters. Although the genotypes in this cluster exhibited smaller tree sizes, they displayed moderate fruit traits.

Discussion

Germplasm assessment and screening for desirable traits are well-established breeding strategies for the effective management and utilization of plant genetic resources43. Morphological traits have long been employed as key indicators for assessing genetic variability and establishing genetic linkages among plant genotypes44,45. These traits are relatively easy to observe and distinguish, require minimal expertise, and are supported by standardized descriptor lists available for many crop species. Morphological diversity has been successfully assessed in many plants such as Pomegranate29, Country Bean44, Pea46, Fig47, Sorghum48, Lentil49, Pumpkin50, Tomato51, Pistachio tree52 and Apple53.

As Pakistan is among the largest producers and exporters of mango and possesses rich mango diversity, the lack of comprehensive morphological characterization limits the effective utilization and conservation of this valuable germplasm. Since farmers and growers are limited to cultivating only a few popular mango genotypes, a large portion of the existing genetic diversity remains underutilized. Considering this, it is highly important to identify novel, improved, and high-yielding mango varieties that could be commercialized and popularized widely among farmers and growers in Pakistan to boost their economy. The variability observed among 89 mango varieties for 43 qualitative traits provides valuable insights likely reflect the distinct genetic makeup of individual accessions, despite being cultivated under relatively similar environmental conditions. Among the tree architecture characters, a high level of diversity was observed in canopy shape which may be attributed due to difference in genotype, propagation methods, planting density, and prevailing agro-climatic conditions54. Interestingly, Toili et al.55 observed that 70% of mango accessions in Kenya exhibited a semi-circular crown with predominantly spreading growth habits. In contrast, Rajan et al.56 found significant variation in canopy structure among 26 Indian mango cultivars, supporting our findings. Collectively, these studies indicate that crown shape is influenced by both the composition of the genotypic collection and their geographic origin. Hence, mango tree diversity supports the potential use of these characteristics for varietal characterization in mango germplasm57. Among the evaluated morphological leaf descriptors young leaf color as well as leaf base shape were found to be most variable phenotypically. Mango displays distinctive growth patterns with intermittent flushes, each marked by a variety of leaf colors at emergence, and these growth cycles can occur several times throughout the year54. As a result, young leaves of different mango varieties display unique colors, which can serve as a reliable trait marker for identifying and assessing different cultivars58. These colors may vary from crimson red to brownish in nature. The leaf colors changes from green to deep green as it matures, and may emit a mild, strong or no fragrance59. According to Bally et al.60, mango leaves exhibit considerable morphological variation, commonly displaying oblong shapes with tip forms ranging from rounded to acuminate. Such differences in leaf characteristics may arise due to genotypic variation, environmental conditions, cultivation practices, and the developmental stage of the plant. Although inflorescence-related qualitative traits exhibited high Shannon–Weaver diversity index (H′) values, none showed sufficient discriminatory power to serve as standalone varietal markers. The uniform distribution of variability across traits prevented clear genotype-specific differentiation. This aligns with previous studies, which also reported limited discriminatory value of floral traits in mango diversity assessments1,61. In the present investigation, among the fruit morphological traits, the highest diversity was observed in fruit shapes followed by beak shape and mature fruit shoulder. The prominent fruit shape observed in most of the genotypes was ovate round. Previously, Jena et al.32 noted a considerable variation in fruit shape represented by five classes i.e. roundish, obovoid, elliptic, oblong and ovoid and they identified 30 out of 58 genotypes possessing roundish shape. However, Shamili et al.62 reported only 2 forms of fruit shapes such as elongated and oblong among Iranian genotypes. Fruit traits have consistently demonstrated strong discriminating power in mango germplasm characterization. According to Gálvez-López et al.63 and Rajwana et al.25, externally visible characteristics such as fruit peel color, size, and shape are particularly effective in distinguishing genotypes. Fruit sensory quality traits also exhibited wide diversity among the genotypes evaluated. These traits are highly valuable not only for germplasm differentiation but also for market preferences, as they directly influence consumer acceptability, post-harvest value, and commercial success of mango cultivars64,65. A notable diversity was observed in the blush color in ripe and unripe fruits and its intensity among the germplasm under study. In this study, some of the genotypes showed different blush colors including orange, yellow, pinkish/red, pink, red and burgundy in unripe and ripe fruits. These blush colors were more dominant in the exotic germplasm compared to the local germplasm. Previously, Singh et al.66 reported a range of fruit colors among mango genotypes varying from attractive yellow with red blush on the shoulders to fully colored, yellowish, deep chrome and greenish. They proposed to utilize these colorful genotypes as donor for developing colored mango hybrids and suggested that skin color of mango fruit is considered as genotype dependent trait. Similarly, Jena et al.32 identified 11 phenotypic classes for fruit skin color and majority of genotypes showed yellow ripe fruits skin color which is consistent with our results. Fruits generally have a dark green background that becomes light green to yellow in color as they ripe54. Red blush develops in some fruits at fruit set which likely persist towards ripening stage. The red blush in mango skin is also genotype dependent due to a pigment known as anthocyanin60,67. Apart from blush color, fruit flesh color is also a valuable marker for identifying mango genotypes. The results showed that most of the genotypes showed yellow and orange flesh color. These results align with the findings of Khadivi et al.19 and Aziz et al.68. Dark orange flesh of mango fruits preferred not only for domestic use, but also for processing industry32. The greater variability in peel color and fruit flesh (pulp) color reflects the high heterozygous nature of the genotypes. Among the stone qualitative traits, high diversity was observed in fiber density and texture. Most of the genotypes showed fine fiber texture and medium fiber density. Khadivi et al.19 reported that quantity of fiber on the stone was intermediate in most of the genotypes. Among quantitative traits trunk diameter showed the highest coefficient of variation (CV%) compared to tree height, which supports the varietal characterization based on mango tree diversity57. Fruit weight showed the second highest CV% among all other traits. In line with these findings, the present study confirms that fruit traits exhibit greater variability compared to other morphological traits, making them key descriptors for distinguishing mango accessions. Kulkarni et al.69 observed extensive diversity in an Indian mango collection comprising over 300 accessions, primarily based on fruit size. Gitahi et al.70 assessed the diversity of 36 local mango accessions from Kenya using both morphological and molecular markers and found high morphological diversity based on fruit traits. Ahmed and Mohamed71 studied the diversity of 30 mango cultivars in Sudan using fruit descriptors and reported high intraspecific diversity within the population. Their findings highlighted significant variability in fruit morphometric traits (such as size, weight, and circumference), fruit shape characteristics (including apex shape and shoulder slope) and fruit quality attributes (such as pulp fiber content). In line with these findings, the present study confirms that fruit traits exhibit greater variability compared to other morphological traits, making them key descriptors for distinguishing mango accessions.

To identify elite genotypes for breeding and consumer preference, selected fruit traits were prioritized based on their desirability and relevance to market standards72. Fruit blush color is one of the most critical consumer preference traits influencing marketability and visual appeal73. In this study most of the exotic varieties had medium to strong blush colors which enhance the fruit’s aesthetic value and often indicate anthocyanin accumulation, which may be associated with antioxidant properties. Fruit size is an important character and medium-sized fruits (250–350 g) are ideal for commercial cultivation as they offer a balance between consumer preference and orchard productivity74. In the current study, most of the genotypes from local germplasm had idea fruit size. Orange-colored pulp, indicative of high carotenoid content and nutritional value, was prominently observed in majority of the local genotypes. Fruit firmness, essential for transport and postharvest shelf life75. In our study, genotypes showing moderate firmness are ideal for export and longer shelf-life. The high juiciness with low fiber quantity is a desirable feature determining the suitability of a variety for processed products as well for fresh consumption76. In this context, varieties with high juice content are considered more suitable for manufacturing products of commercial relevance.

Correlation analysis provides meaningful insights into the genetic relationships among traits and helps in understanding how one trait may directly or indirectly influence another. In the present study, both qualitative and quantitative traits were examined, revealing significant positive and negative correlations. Among the qualitative traits, branching pattern was positively correlated with canopy shape. This positive association suggests that the plant’s branching pattern could be a key factor in determining the overall canopy shape77. Similarly, leaf base shape showed a positive association with leaf shape, and leaf attitude towards the main branch was significantly related to leaf shape in cross section, suggesting potential co-inheritance or shared developmental pathways among foliar traits. This is in consistent with the findings that qualitative traits in plants are often governed by a small number of major genes, which can lead to observable correlations between morphologically related traits78. Fruit-related features showed particularly strong correlations, especially between blush color ripe and blush color unripe and blush intensity ripe and blush color ripe. This suggests consistency in pigment biosynthesis pathways throughout the fruit ripening process, likely governed by shared regulatory genes79. Notably, fruit neck characteristics, such as prominence of neck, were strongly correlated with stem end shape, and beak shape, supporting the hypothesis that fruit-end morphology may be developmentally coordinated80. Furthermore, flesh fiber strength was strongly associated with flesh fiber quantity, implying that texture-related traits may be governed by shared physiological or genetic mechanisms. These traits not only affect eating quality but also postharvest shelf life and processing suitability, highlighting their relevance in breeding programs targeting improved sensory and industrial traits81. Some positive correlations among the fruit quantitative traits including fruit length, fruit width, fruit weight, stone length, stone width and stone weight, confirming that heavier fruits possessed higher amount of pulp content and elongated fruits are likely to possess proportionally larger stones. This finding aligns with previous studies by Singh et al.66, Narvariya et al.82.

PCA proved to be an effective tool for reducing the complexity of morphological trait data by transforming a large number of correlated variables into a smaller set of uncorrelated principal components, while preserving most of the original variability83,84. In this study, PCA captured the key traits contributing to phenotypic variation among the 89 mango genotypes. It provides breeders with measurable insights into the germplasm collection, helping to identify traits that show greater potential and can serve as promising candidates for future breeding efforts85. The PCA analysis of 43 qualitative traits revealed that first 17 PCs had eigenvalues greater than 1 and together explained 75.4% of the cumulative variance. This suggests a broad and complex distribution of variability across multiple morphological traits, with no single trait or small group of traits accounting for a disproportionate share of diversity. Although the first two components contributed noticeably to the observed variation, the contribution was evenly distributed across many traits. This pattern reflects the polygenic nature of qualitative phenotypic traits in mango. The PCA biplot for PC1 and PC2 displayed loose clustering patterns, indicating some structure but no sharp delineation of groups. Traits like blush color (ripe and unripe), blush intensity, and color of rachis and branches had high cos² values and were located farthest from the origin, suggesting they contributed most strongly to the variation captured in PC1 and PC2 for qualitative traits. The PCA of quantitative traits identified four principal components with eigenvalues greater than 1. PC1 primarily represents fruit and stone traits, as it showed strong positive loadings for fruit length, width, thickness, weight, and stone length, width, and weight. This suggests that fruit size and stone characteristics are the major drivers of phenotypic variability among the studied genotypes. PC2 showed strong positive loadings for tree height, trunk diameter, leaf length and width, petiole length, and panicle size, but negative loadings for most fruit traits. This implies PC2 is associated more with vegetative and inflorescence morphology rather than reproductive traits. The identification of traits with high loadings on the PCs can guide future research directions, particularly in exploring the genetic basis of these traits86.

Agglomerative hierarchical clustering (AHC) analysis employed Ward’s method using Euclidean distance to assess the genetic diversity and group 89 genotypes into distinct clusters. Clustering enables the grouping of accessions based on their similarities or dissimilarities87,88. The mango germplasm studied was grouped into five main clusters based on quantitative and six clusters based on qualitative traits. Clusters IV from qualitative as well as quantitative traits contained more varieties, while some had fewer genotypes. This distribution suggests that clusters with fewer genotypes may have a higher degree of variability or unique trait combinations compared to the larger clusters84. Even though morphological characterization is very relevant to appraise the diversity in a collection, most of the characters are influenced by environmental conditions, and the number of descriptors are not always enough to reveal the full extent of the variability1. As such, grouping of accessions based on morphological traits may yield clusters of individuals that are morphologically different from each other in regard to major traits of interest89. Notably, the clustering patterns observed in this study differ from earlier reports, as this is the first comprehensive clustering analysis involving both Pakistani and exotic mango genotypes. The dendrogram also revealed meaningful biological groupings, such as distinct clustering of local and exotic germplasm and grouping of genotypes is based on shared characteristics. These results underscore the potential of morphological clustering for preliminary classification and identification of promising parental lines. The current findings thus offer a valuable foundation for selecting genetically divergent and agronomically desirable genotypes from different clusters to enhance variability in mango improvement programs.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of morphological diversity among 89 mango genotypes collected from Pakistan. Several traits, including canopy shape, young leaf color, fruit shape, blush color, fruit flesh color, fruit weight and size exhibited notable variation reflecting genetic and environmental influences. Correlation analysis identified significant relationships and PCA highlighted fruit and seed characters as key traits contributing to variation, while dendrogram analysis classified the varieties into different clusters, offering insights into genetic similarity. This study also highlights the elite genotypes possessing multiple desirable fruit traits, including high pulp content, attractive blush and flesh color, medium firmness, high juiciness, and low fiber quantity. These are considered as promising genotypes for both table consumption and industrial use. Despite this rich diversity, our findings emphasize that a significant proportion of both exotic and local mango germplasm remains underutilized in breeding programs. This is largely due to limited characterization and lack of accessible information, resulting in a narrow genetic base being used by growers and farmers. The identification and promotion of such promising genotypes is, therefore, a crucial step toward broadening the genetic base of mango cultivation in Pakistan. The phenotypic insights from this study form a vital foundation for future molecular-level characterization, including genetic marker-based diversity and association studies. A combined morphological and molecular approach will enhance the precision of genotype selection and accelerate the development of improved mango cultivars through marker-assisted breeding.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the paper or supplementary information.

References

Zhang, C. et al. Diversity of a large collection of natural populations of Mango (Mangifera indica Linn.) revealed by agro-morphological and quality traits. Diversity 12, 27 (2020).

Kumar, S. et al. Genetic diversity among local Mango (Mangifera indica L.) germplasm using morphological, biochemical and Chloroplast DNA barcodes analyses. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49, 3491–3501 (2022).

Sawangchote, P., Grote, P. J. & Dilcher, D. L. Tertiary leaf fossils of mangifera (Anacardiaceae) from Li Basin, Thailand as examples of the utility of leaf marginal venation characters. Am. J. Bot. 96, 2048–2061 (2009).

Hu, H. et al. Genome-wide identification, characterization and expression analysis of Mango (Mangifera indica l.) chalcone synthase (CHS) genes in response to light. Horticulturae 8, 968 (2022).

Akin-Idowu, P. E. et al. Diversity of Mango (Mangifera indica L.) cultivars based on physicochemical, nutritional, antioxidant, and phytochemical traits in South West Nigeria. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 20, S352–S376 (2020).

Maldonado-Celis, M. E. et al. Chemical composition of Mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit: nutritional and phytochemical compounds. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1073 (2019).

Huang, C. Y. et al. Free radical-scavenging, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial activities of water and ethanol extracts prepared from compressional-puffing pretreated Mango (Mangifera indica L.) peels. J. Food Qual. 2018, 1–13 (2018).

Roy, D. K. & Abedin, M. Z. Potentiality of biodiesel and bioethanol production from feedstock in bangladesh: A review. Heliyon 8, e11213 (2022).

García-Mahecha, M. et al. Bioactive compounds in extracts from the agro-industrial waste of Mango. Molecules 28, 458 (2023).

Grewal, A. G. et al. Agricultural Sci. J. 6, 59–72 (2024).

Badar, H., Ariyawardana, A. & Collins, R. Dynamics of Mango value chains in Pakistan. Pak J. Agric. Sci. 56, 523–530 (2019).

Murtaza, M. R., Mehmood, T., Ahmad, A. & Mughal, U. A. With and without intercropping economic evaluation of Mango fruits: evidence from Southern Punjab, Pakistan. Sarhad J. Agric. 36, 192–197 (2020).

Zahid, G., Aka Kaçar, Y., Shimira, F., Iftikhar, S. & Nadeem, M. A. Recent progress in omics and biotechnological approaches for improved Mango cultivars in Pakistan. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 69, 2047–2065 (2022).

Shah, M. H. et al. A Review: Fruit production industry of Pakistan trends, issues and way forward. Pakistan J. Agricultural Research 35, 523-532 (2022).

Riaz, R., Khan, A. S., Ziaf, K. & Naseer Cheema, H. M. Genetic diversity of wild and cultivated mango genotypes of Pakistan using SSR markers. Pakistan J. Agricultural Sciences 55, 83-93 (2018).

Zahoor, S., Anwar, F., Qadir, R., Soufan, W. & Sakran, M. Physicochemical attributes and antioxidant potential of kernel oils from selected Mango varieties. ACS Omega. 8, 22613–22622 (2023).

Memon, N. A. Pakistan to export 100,000 tonnes of mangoes this season. Pakistan Food J. (PFJ). 4, 24–27 (2015).

Nafees, M., Ahmad, S., Anwar, R., Ahmad, I. & Hussnain, R. R. Improved horticultural practices against leaf wilting, root rot and nutrient uptake in mango (Mangifera indica L.) Pakistan J. Agricultural Sciences 50, 393-398 (2013).

Khadivi, A., Mirheidari, F., Saeidifar, A. & Moradi, Y. Identification of the promising Mango (Mangifera indica L.) genotypes based on morphological and Pomological characters. Food Science Nutrition. 10, 3638–3650 (2022).

Krishna, H. & Singh, S. K. Biotechnological advances in Mango (Mangifera indica L.) and their future implication in crop improvement—a review. Biotechnol. Adv. 25, 223–243 (2007).

Akinyemi, S. O. In Achieving Sustainable Cultivation of Tropical Fruits 471–488 (Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, 2019).

Zhou, L. et al. Evaluation of the genetic diversity of Mango (Mangifera indica L.) seedling germplasm resources and their potential parents with start codon targeted (SCoT) markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 67, 41–58 (2020).

Sankaran, M., Dinesh, M. R. & Ravishankar, K. V. Classical genetics and breeding. In: Kole, C. (eds) The mango genome. Compendium of Plant Genomes. Springer, Cham. 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47829-2_7 (2021).

Rao, N. S., Shivashankara, K. S. & Laxman, R. H. Abiotic Stress Physiology of Horticultural Crops Vol. 311 (Springer, 2016).

Rajwana, I. A. et al. Morphological and biochemical markers for varietal characterization and quality assessment of potential Indigenous Mango (Mangifera indica) germplasm. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 13, 151–158 (2011).

Kebede, G., Worku, W., Feyissa, F. & Jifar, H. Agro-morphological traits-based genetic diversity assessment on oat (Avena sativa L.) genotypes in the central highlands of Ethiopia. All Life. 16, 2236313 (2023).

Jena, R. C. & Chand, P. K. DNA marker-based auditing of genetic diversity and population structuring of Indian Mango (Mangifera indica L.) elites. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 69, 1595–1626 (2022).

Khan, M. H. et al. Morpho-Biochemical characterization of Kalazeera (Bunium persicum Boiss. Fedts) germplasm grown in global temperate ecologies. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 30, 103633 (2023).

Khadivi, A. & Arab, M. Identification of the superior genotypes of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) using morphological and fruit characters. Food Science Nutrition. 9, 4578–4588 (2021).

Shariatipour, N., Heidari, B., Shams, Z. & Richards, C. Assessing the potential of native ecotypes of Poa pratensis L. for forage yield and phytochemical compositions under water deficit conditions. Sci. Rep. 12, 1121 (2022).

Esan, V. I. et al. Genetic variability and Morpho-Agronomic characterization of some Mango (Mangifera indica L.) cultivars and varieties in Nigeria. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 24, 256–272 (2024).

Jena, R. C., Agarwal, K. & Chand, P. K. Fruit and leaf diversity of selected Indian mangoes (Mangifera indica L). Sci. Hort. 282, 109941 (2021).

Team, R. C. RA language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical. Computing at (2020). https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1370298755636824325

Comtois, D., Comtois, M. D. & Package ‘summarytools’. at (2016). http://cran.opencpu.org/web/packages/summarytools/summarytools.pdf

Oksanen, J. Vegan: community ecology package. http://vegan. r-forge. r-project. org/ at (2010). https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1570291225091856896

Shannon, C. E. The mathematical theory of communication by CE Shannon and W. Bell Syst. Techn –1948 –J. 27, 3–4 (1949).

Eticha, F., Bekele, E., Belay, G. & Börner, A. Phenotypic diversity in tetraploid wheats collected from Bale and Wello regions of Ethiopia. Plant. Genetic Resour. 3, 35–43 (2005).

Wei, T. et al. Package ‘corrplot’. Statistician 56, e24 (2017).

Braga, A. C. et al. in In Computational Science and its Applications – ICCSA 2018. Vol. 10961, 366–381 (eds Gervasi, O.) (Springer International Publishing, 2018).

Kassambara, A. Factoextra: extract and visualize the results of multivariate data analyses. R Package Version 1, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra (2016).

Lê, S., Josse, J. & Husson, F. FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 25, 1–18 (2008).

Maechler, M. et al. cluster: Cluster analysis basics and extensions. R package version 1.14.4. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cluster (2013).

Nietsche, S. et al. Variability in reproductive traits in Jatropha Curcas L. accessions during early developmental stages under warm subtropical conditions. GCB Bioenergy. 7, 122–134 (2015).

Khatun, R., Uddin, M. I., Uddin, M. M., Howlader, M. T. H. & Haque, M. S. Analysis of qualitative and quantitative morphological traits related to yield in country bean (Lablab purpureus L. sweet) genotypes. Heliyon 8, (2022).

Rai, N., Singh, K., Chandra Rai, P., Prakash Rai, A., Singh, M. & V. & Genetic diversity in Indian bean (Lablab purpureus) germplasm based on morphological traits and RAPD markers. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 81, 801 (2011).

Azam, M. G. et al. Phenotypic diversity in qualitative and quantitative traits for selection of high yield potential field pea genotypes. Sci. Rep. 14, 18561 (2024).

Khadivi, A., Anjam, R. & Anjam, K. Morphological and Pomological characterization of edible Fig (Ficus carica L.) to select the superior trees. Sci. Hort. 238, 66–74 (2018).

Naoura, G. et al. Assessment of agro-morphological variability of dry-season sorghum cultivars in Chad as novel sources of drought tolerance. Sci. Rep. 9, 19581 (2019).

Tripathi, K. et al. Agro-morphological characterization of lentil germplasm of Indian National genebank and development of a core set for efficient utilization in lentil improvement programs. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 751429 (2022).

Ezin, V., Gbemenou, U. H. & Ahanchede, A. Characterization of cultivated pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duchesne) landraces for genotypic variance, heritability and agro-morphological traits. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 29, 3661–3674 (2022).

Salim, M. M. R., Rashid, M. H., Hossain, M. M. & Zakaria, M. Morphological characterization of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) genotypes. J. Saudi Soc. Agricultural Sci. 19, 233–240 (2020).

Ennouri, K. et al. Analysis of variability in pistacia Vera L. fruit genotypes based on morphological attributes and biometric techniques. Acta Physiol. Plant. 42, 1–9 (2020).

Mir, J. I. et al. Diversity evaluation of fruit quality of Apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) germplasm through cluster and principal component analysis. Ind. J. Plant. Physiol. 22, 221–226 (2017).

Khan, A. S., Ali, S. & Khan, I. A. Morphological and molecular characterization and evaluation of Mango germplasm: an overview. Sci. Hort. 194, 353–366 (2015).

Toili, M. E. M., Rimberia, F. K., Nyende, A. B. & Sila, D. Morphological diversity of Mango germplasm from the upper athi river region of Eastern kenya: an analysis based on non-fruit descriptors. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 16, 10913–10935 (2016).

Rajan, S., Kumar, R. & Negi, S. S. Variation in canopy characteristics of Mango (Mangifera indica L.) cultivars from diverse eco-geographical regions. J. Appl. Hort. 3, 95–97 (2001).

Human, C. F. Production areas. The Cultivation of Mango. ARC-Institute for Tropical and Subtropical Crops 9–15 (2008).

Ibrahim, M. A study of the distinguishing vegetative, floral and fruit characteristics of Punjab Mangoes. (1952).

Fivaz, J. Botanical aspects. In: de Villiers, E.A., Joubert,P.H. (Eds.), The Cultivation of Mango. ARC Institute forTropical and Subtropical Crops, Florida, USA, 9–20 (2008).

Bally, I. S. E. Mangifera indica (mango). Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry . 1–25 (2006).

Krishnapillai, N. & Wijeratnam, R. W. Morphometric analysis of Mango varieties in Sri Lanka. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 10, 784–792 (2016).

Shamili, M., Fatahi, R. & Hormaza, J. I. Characterization and evaluation of genetic diversity of Iranian Mango (Mangifera indica L., Anacardiaceae) genotypes using microsatellites. Sci. Hort. 148, 230–234 (2012).

Gálvez-López, D., Salvador-Figueroa, M. & Adriano-Anaya, M. L. Mayek-Pérez, N. Morphological characterization of native mangos from Chiapas, Mexico. Subtropical Plant. Sci. 62, 18–26 (2010).

de Botton Campbell, C. & Bernard, R. Mangos in the United States: A year long supply. in Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society 107, 333–333 (1994).

De Mori, G. & Cipriani, G. Marker-assisted selection in breeding for fruit trait improvement: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 8984 (2023).

Singh, N. P., Jerath, N., Singh, G. & Gill, P. P. Physico-chemical characterization of unexploited Mango diversity in sub-mountane zone of Northern India. Indian J. Plant. Genetic Resour. 25, 261–269 (2012).

Lizada, M. C. Postharvest physiology of the mango-A review. in III International Mango Symposium 291 437–453 at (1989). https://www.actahort.org/books/291/291_50.htm

Abdul Aziz, N. A., Wong, L. M., Bhat, R. & Cheng, L. H. Evaluation of processed green and ripe Mango Peel and pulp flours (Mangifera indica var. Chokanan) in terms of chemical composition, antioxidant compounds and functional properties. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 92, 557–563 (2012).

Kulkarni, M. M. et al. Mango fruit size diversity found in Konkan. Adv. Agricultural Res. Technol. J. 3, 43–46 (2019).

Gitahi, R., Kasili, R., Kyallo, M. & Kehlenbeck, K. Diversity of threatened local Mango landraces on smallholder farms in Eastern Kenya. Forests Trees Livelihoods. 25, 239–254 (2016).

Ahmed, T. H. M. & Mohamed, Z. M. A. Diversity of Mango (Mangifera indica L.) cultivars in Shendi area: morphological fruit characterization. Int. J. Res. Agricultural Sci. 2, 2348–3997 (2015).

Ladaniya, M. S. Commercial fresh citrus cultivars and producing countries. Citrus Fruit: Biology, Technology and Evaluation. Academic Press, San Diego 13–65 (2008).

Dar, J. A. et al. Peel colour in Apple (Malus× domestica Borkh.): an economic quality parameter in fruit market. Sci. Hort. 244, 50–60 (2019).

Yahia, E. H. M. Postharvest handling of mango. ATUT/RONCO technical staff, Egypt. Accessed 4, (1999). (2000).

Ahmad, M. S. & Siddiqui, M. W. in Postharvest quality assurance of fruits: practical approaches for developing countries 7–32 (Springer, 2015).

Barrett, D. M., Beaulieu, J. C. & Shewfelt, R. Color, flavor, texture, and nutritional quality of fresh-cut fruits and vegetables: desirable levels, instrumental and sensory measurement, and the effects of processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 50, 369–389 (2010).

Sreekanta, S. et al. Variation in shoot architecture traits and their relationship to canopy coverage and light interception in soybean (Glycine max). BMC Plant Biol. 24, 194 (2024).

Maemunah, M., Samudin, S. & Mustakim, M. Morphological characteristics of superior purple and local red corns. Agroland Agric. Sci. J. (eJ). 9, 29–35 (2022).

Kapoor, L., Simkin, A. J., Priya Doss, G., Siva, R. & C. & Fruit ripening: dynamics and integrated analysis of carotenoids and anthocyanins. BMC Plant Biol. 22, 27 (2022).

Goldman, I. L. et al. Form and contour: breeding and genetics of organ shape from wild relatives to modern vegetable crops. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1257707 (2023).

Hayat, U. et al. An overview on post-harvest technological advances and ripening techniques for increasing Peach fruit quality and shelf life. Horticulturae 10, 4 (2023).

Narvariya, S. S. Classification of different varieties and new accessions of mango (Mangifera indica L.) based on qualitative traits and assessment of genetic diversity. PhD thesis, Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Pantnagar (Uttarakhand) (2016).

Christina, G. R., Thirumurugan, T., Jeyaprakash, P. & Rajanbabu, V. Principal component analysis of yield and yield related traits in rice (Oryza sativa L.) landraces. Electron. J. Plant. Breed. 12, 907–911 (2021).

Kumar, S. S. et al. Genetic diversity and agro-morphological characterization of cassava varieties provides insight for breeding and crop improvement. Sci. Rep. 15, 17498 (2025).

Guei, R. G., Sanni, K. A., Abamu, F. J. & Fawole, I. Genetic diversity of rice (Oryza sativa L). Agronomie Africaine. 5, 17–28 (2005).

Aschard, H. et al. Maximizing the power of principal-component analysis of correlated phenotypes in genome-wide association studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 94, 662–676 (2014).

Rashid, M. et al. Genetic variability assessment of worldwide spinach accessions by agro-morphological traits. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 14, 1637–1650 (2020).

White, J. W. et al. Field-based phenomics for plant genetics research. Field Crops Res. 133, 101–112 (2012).

Prohens, J., Blanca, J. M. & Nuez, F. Morphological and molecular variation in a collection of eggplants from a secondary center of diversity: Implications for conservation and breeding. at https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/ (2005). https://doi.org/10.5555/20053061165%3E

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Mango Research Station (MRS), Shujabad, for providing access to mango germplasm. We also thank the Queensland laboratory for sharing additional descriptors used in morphological characterization. Special thanks to Lahore College for Women University (LCWU) for providing laboratory facilities essential for conducting this research.

Funding

The authors report no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Z.A. conceptualized the study, designed the methodology, collected and analyzed the data, and prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. H.M. supervised the research, managed the overall project, and contributed to manuscript revision. A.A. provided additional descriptors for morphological characterization and contributed to manuscript editing. M.A. contributed to statistical analysis and interpretation of results J.I. provided field guidance and support in germplasm collection. R.H. critically reviewed the manuscript and contributed to final corrections. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ansari, W.Z., Mukhtar, H., Ali, A. et al. Evaluation of mango (Mangifera indica L.) germplasm for phenotypic diversity and breeding potential in Pakistan. Sci Rep 16, 3693 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33793-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published: