Abstract

The global rise of colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) is a critical health threat, particularly in the Middle East. The pmrB c.235T > A (p.Leu79Ile) mutation is frequently observed in clinical isolates, but its comprehensive characterization is lacking. In this multicenter study, 465 clinical A. baumannii isolates were collected from Iran (n = 378) and Iraq (n = 87) between January 2023 and June 2024. Colistin susceptibility was determined by broth microdilution, and the pmrCAB operon was sequenced. The structural impact of p.Leu79Ile was assessed via 200-ns molecular dynamics simulations. Functional consequences were evaluated using lipid A profiling, biofilm assays, serum resistance, and a murine pneumonia model. Phylogeographic analysis and a LASSO-regularized logistic regression model for 30-day mortality prediction were performed. Colistin resistance was detected in 47.8% of isolates, with 94.2% of resistant isolates harboring pmrCAB mutations; c.235T > A was predominant (76.8%). Simulations indicated that Leu79Ile stabilizes the active conformation of PmrB (ΔΔG = -3.8 kcal/mol), increasing the root mean square deviation (RMSD; 4.7 Å vs. 2.3 Å) and altering protein dynamics. This correlated with a 1.93-fold increase in pEtN-modified lipid A and a strong inverse correlation with colistin MIC (ρ = -0.89). Mutant isolates exhibited enhanced biofilm formation (2.3-fold), serum survival (47.6% increase), and murine mortality (70% vs. 30%). Phylogenetics identified a dominant ST848-bla ~ OXA-23~^+^ clone emerging around 2016 (95% HPD: 2015–2017), with evidence of Iran-Iraq cross-border transmission. The mortality prediction model (predictors: age > 65, CCI > 3, ventilation, shock, c.235T > A, ST848) achieved an AUC = 0.87 in validation. This study suggests the pmrB c.235T > A mutation confers a dual phenotype of colistin resistance and hypervirulence, driven by structural stabilization of PmrB within an expanding regional clone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acinetobacter baumannii, particularly carbapenem-resistant strains (CRAB), poses a severe threat in healthcare settings worldwide1,2. With limited treatment options, polymyxins like colistin have become last-resort therapies3. However, the increasing prevalence of colistin-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB) is leading to untreatable infections and high mortality4,5.

Chromosomal colistin resistance in A. baumannii primarily involves modification of lipid A, the membrane anchor of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The addition of phosphoethanolamine (pEtN) neutralizes lipid A’s negative charge, reducing colistin binding6. This process is regulated by the PmrA/PmrB two-component system. Environmental signals trigger PmrB autophosphorylation, leading to PmrA activation and subsequent upregulation of pmrC, the gene encoding the pEtN transferase7,8.

Clinically, mutations in pmrB can lock the kinase in a constitutively active state, prompting pEtN modification and resistance without external stimuli9. While many pmrB mutations have been reported, their structural, functional, and clinical impacts are often unclear. The c.235T > A (p.Leu79Ile) substitution has been observed in global surveillance10, but a comprehensive analysis linking its molecular mechanism to virulence and patient outcomes is lacking.

This knowledge gap is critical in the Middle East, a hotspot for CRAB emergence11,12,13. Iran and Iraq report some of the world’s highest CRAB burdens14,15,16, yet detailed molecular studies from this region are scarce17. We hypothesized that the pmrB c.235T > A mutation structurally stabilizes the active state of PmrB, leading to constitutive lipid A modification, which simultaneously drives colistin resistance and enhances virulence.

To test this, we conducted an integrated analysis of pmrB c.235T > A in a large cohort from Iran and Iraq. Our objectives were to: (1) determine the prevalence and evolutionary history of the mutation; (2) decipher how p.Leu79Ile alters PmrB structure; (3) quantify its impact on lipid A modification and virulence traits; and (4) develop a predictive model for 30-day mortality.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval and clinical isolate procurement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tehran Medical Sciences, Islamic Azad University (IR.IAU.TMS.REC.1401.025). A total of 465 non-duplicate A. baumannii isolates were collected retrospectively from tertiary-care hospitals in Iran (n = 378) and Baghdad, Iraq (n = 87) between January 2023 and June 2024. Only isolates from healthcare-associated infections (onset ≥ 48 h post-admission) were included. All patient identifiers were removed, and the IRB waived the need for informed consent due to the retrospective, anonymized nature of the study. All procedures complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Species identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

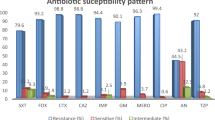

Isolates were identified using MALDI-TOF MS (Bruker Daltonics) and confirmed by PCR for bla ~ OXA-51-like~. Colistin MICs were determined by broth microdilution per EUCAST v11.0 (resistance: MIC ≥ 4 µg/mL). MICs for other agents were generated using VITEK 2 Compact (bioMérieux). Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) classification followed international criteria18, defined as resistance to at least one agent in all but two or fewer antimicrobial categories. The tested categories included aminoglycosides, beta-lactams/beta-lactamase inhibitors, carbapenems, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and tetracyclines.

Genomic DNA extraction, amplification, and mutation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted with the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen). The full pmrCAB operon was PCR-amplified and Sanger sequenced (Applied Biosystems ABI 3730xl). Variants were identified by alignment to the A. baumannii ATCC 17,978 reference genome using Geneious Prime v2023.1.1.

Structural modeling and molecular dynamics simulations

The structural impact of p.Leu79Ile was evaluated using molecular dynamics simulations of the PmrB sensor domain (PDB: 6 × 5Z). The mutation was introduced in silico with PyMOL. Systems were solvated, neutralized, and energy-minimized. After equilibration, three independent 200-ns production runs were performed using GROMACS 2023.3 with the CHARMM36m force field. Analyses included RMSD, RMSF, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and Free Energy Landscape (FEL). The free energy difference (ΔΔG) was calculated using the MMPBSA.py module in AmberTools22.

Lipid A extraction and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

Lipid A was extracted from logarithmic-phase cultures using a modified protocol19. Negative-ion MALDI-TOF MS was performed on a Bruker ultrafleXtreme system (m/z 1000–2000). The pEtN modification ratio was calculated as (intensity of pEtN-modified peaks) / (sum intensity of all lipid A species).

Functional virulence profiling

Biofilm formation was quantified via crystal violet staining in 96-well plates. Serum resistance was assessed by incubating ~ 1 × 10⁶ CFU in 50% normal human serum for 3 h. For in vivo virulence, BALB/c mice (n = 6 per group) were intranasally infected with 1 × 10⁸ CFU under isoflurane anesthesia. Survival was monitored for 72 h, and lung bacterial loads were quantified at 24 h. At the end of the 72-hour observation period, all surviving mice were humanely euthanized. Euthanasia was performed by chemical means using an overdose of inhaled isoflurane (5% in oxygen), followed by cervical dislocation as a secondary method to ensure death. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tehran Medical Sciences, Islamic Azad University (IAU.TMS.AEC.1401.007) and followed ARRIVE guidelines.

Multilocus typing and bayesian phylogeography

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) used the Pasteur Institute scheme. Core-genome MLST (cgMLST) was performed on 45 representative isolates sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000. Phylogenetic inference was performed in BEAST2 v2.6.7 under a strict molecular clock model, a Bayesian Skyline population model, and an HKY substitution model. The MCMC chain was run for 100 million generations. The maximum clade credibility tree was generated with FigTree v1.4.4.

Statistical framework and predictive modeling

Statistical analyses used R v4.2.1. Categorical and continuous variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test and Mann-Whitney U/t-test, respectively. Correlations used Spearman’s ρ. A clinical prediction model for 30-day mortality was built using LASSO-regularized logistic regression (`glmnet` package) with 10-fold cross-validation. Model performance was assessed by AUC, Hosmer-Lemeshow test, and Decision Curve Analysis.

Data availability

Data are available under NCBI BioProject PRJNA1327134. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Results

High prevalence of colistin resistance and dominance of the PmrB c.235T > A mutation

Among 465 isolates, colistin resistance was observed in 47.8% (181/465). The MIC₅₀ and MIC₉₀ for resistant isolates were 8 µg/mL and 16 µg/mL, respectively. Of the resistant isolates, 98.9% (179/181) were classified as XDR. Sequencing revealed that 94.2% (171/181) of resistant isolates had at least one pmrCAB mutation. The pmrB c.235T > A (p.Leu79Ile) substitution was the most prevalent (76.8%, 131/171). Other recurrent mutations included G249A, C269T, and T229C. A majority (72.5%) of c.235T > A isolates had concurrent pmrCAB variants. In the Iraqi subset (n = 87), the colistin resistance rate was 46.0% (40/87), with 85.0% (34/40) of resistant Iraqi isolates harboring pmrCAB mutations (Fig.1).

Structural remodeling and stabilization of the active state by the c.235T > A mutation

Molecular dynamics simulations showed that the Leu79Ile substitution induced significant conformational changes. The mutant exhibited higher RMSD (4.7 Å) than the wild-type (2.3 Å), indicating increased flexibility. PCA revealed altered dynamics in dimerization and histidine kinase subdomains. Free energy landscape analysis indicated stabilization of the active kinase state in the mutant, with a net stability gain of ΔΔG = -3.8 kcal/mol (Fig. 2).

Lipid A remodeling directly correlates with resistance phenotype

MALDI-TOF MS showed a significant increase in pEtN-modified lipid A in mutant isolates (0.87 ± 0.09) compared to wild-type (0.45 ± 0.12; p < 0.001), a 93.3% increase. A strong inverse correlation existed between pEtN modification and colistin MIC (ρ = -0.89, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

The c.235T > A mutation confers a hypervirulent phenotype

Mutant isolates displayed enhanced virulence. Biofilm formation was 2.3-fold higher (OD₅₇₀: 1.87 ± 0.32 vs. 0.81 ± 0.21; p = 0.002). Serum survival increased by 47.6% (p < 0.001). In the murine model, infection with mutant isolates led to higher mortality (70% vs. 30% at 72 h; p = 0.008) and a 1.6-log₁₀ increase in lung bacterial burden at 24 h (p < 0.001). These findings indicate that the mutation enhances immune evasion and pathogenicity in vivo (Fig. 4).

Emergence and regional spread of a High-Risk ST848 lineage

MLST and cgMLST identified ST848, carrying blaOXA−23, as the dominant lineage among colistin-resistant isolates (81.3%). Bayesian phylogeographic analysis of 45 ST848 genomes (25 from Iran, 20 from Iraq) estimated this clone emerged around 2016 (95% HPD: 2015–2017) with an effective reproductive number (R ~ e~) of 1.8 (95% HPD: 1.5–2.2). The phylogenetic tree revealed intermingling of Iranian and Iraqi isolates, indicating cross-border transmission (Fig. 5).

Development of a high-performance clinical prediction model

A LASSO-regularized logistic regression model for 30-day mortality was developed. From 15 candidate variables, six predictors were retained: age > 65, Charlson Comorbidity Index > 3, mechanical ventilation, septic shock, pmrB c.235T > A mutation, and ST848 lineage. The model showed excellent discrimination in the training cohort (AUC = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.83–0.94) and the validation cohort (AUC = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.80–0.93) (Fig. 6A, B). Calibration was good (Hosmer-Lemeshow p = 0.42) (Fig. 6C), and decision curve analysis indicated clinical utility across a range of probability thresholds (Fig. 7).

Time-Calibrated Phylogeographic Tree of ST848 Colistin-Resistant A. baumannii Isolates from Iran and Iraq. Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction of 45 representative ST848 A. baumannii isolates (25 Iran, 20 Iraq) harboring the pmrB c.235T > A mutation. The maximum clade credibility tree was generated using BEAST2 under a strict molecular clock and Bayesian skyline model. Branch lengths are time-scaled (x-axis). A time scale bar is included. Node labels indicate posterior probabilities. The analysis suggests a common ancestor arising circa 2016, followed by clonal expansion with evidence of Iran-Iraq cross-transmission.

Clinical Performance of a Mortality Prediction Model in Colistin-Resistant A. baumannii Infections. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves of the logistic regression model in the (A) training and (B) validation cohorts. (C) Calibration plot comparing predicted versus observed 30-day mortality.

Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) of the 30-day Mortality Prediction Model. The DCA evaluates the clinical utility of the prediction model across a range of threshold probabilities. The net benefit of using the model (solid line) is compared against the strategies of assuming all patients die (dashed line) or all patients survive (dotted line). The model shows a positive net benefit across a wide range of thresholds, supporting its potential clinical applicability.

Discussion

This study provides a multi-faceted analysis of the pmrB c.235T > A mutation in CRAB. Our findings suggest this mutation acts as a molecular switch that concurrently promotes colistin resistance and hypervirulence. The integration of computational, phenotypic, and epidemiological data moves beyond correlation to propose a causal pathway from a single nucleotide change to a high-risk clinical phenotype.

Our molecular dynamics simulations offer a plausible structural mechanism, indicating that the Leu79Ile substitution stabilizes the active conformation of PmrB. This in silico prediction provides a biophysical rationale for the constitutive activation of the PmrAB pathway, though direct biochemical validation with purified proteins is needed for confirmation. The subsequent 93.3% increase in pEtN-modified lipid A provides functional evidence linking the mutation to the resistance phenotype, consistent with the known role of lipid A modification6,720]. Interestingly, our results contrast with a recent report from Turkey that found a high rate (84.2%) of colistin susceptibility in Acinetobacter isolates [21, 22], highlighting significant regional variation in resistance patterns and underscoring the importance of local surveillance [23].

A key finding is the concurrent enhancement of virulence traits—biofilm formation, serum resistance, and lethality in a murine pneumonia model—associated with the c.235T > A mutation. This challenges the traditional view of a fitness cost associated with resistance mutations24,25. Similar to observations by Islam et al.26, we found no evidence of fitness attenuation. Instead, our data suggest a pathoadaptive advantage, potentially mediated by the broad regulatory role of the PmrA regulon on genes involved in membrane integrity and stress response27,28. The convergence of resistance and virulence in this clone presents a serious challenge for infection control [32,33].

Phylogeographic analysis revealed that this high-risk mutation is embedded within the rapidly expanding ST848 clone. The evidence of cross-border transmission between Iran and Iraq calls for coordinated regional surveillance efforts. The high discriminatory power of our clinical prediction model, which incorporates both clinical and microbiological predictors including the specific pmrB mutation, demonstrates the potential for genomics to improve patient risk stratification. Incorporating pmrB mutation screening into molecular diagnostic panels could enable earlier identification of patients at highest risk of poor outcomes, guiding more aggressive or tailored therapeutic strategies [34,35,36].

Limitations

This study has limitations. Its observational nature prevents definitive causal inference, and unmeasured confounders may influence outcomes. The phenotypic effects of Leu79Ile may be confounded by other pmrCAB mutations present in most isolates. The MD simulations, while insightful, are computational predictions that require biochemical validation. The geographic focus on Iran and Iraq limits the generalizability of the ST848 lineage’s global relevance. Finally, the murine model may not fully recapitulate human CRAB infection.

Conclusion and future directions

In summary, the pmrB c.235T > A mutation is linked to a dual phenotype of colistin resistance and hypervirulence in A. baumannii, facilitated by the structural stabilization of PmrB and its subsequent effects on lipid A and virulence pathways. Its association with the expanding ST848 clone underscores a significant public health threat in the Middle East. Future work should focus on: (1) generating isogenic mutants to definitively attribute the phenotype to the Leu79Ile change; (2) biochemical validation of PmrB autophosphorylation kinetics; and (3) expanding surveillance to determine the global prevalence of ST848. Our findings advocate for integrating specific resistance mutation data into diagnostic and prognostic tools to combat CRAB infections effectively.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI BioProject repository, accession number PRJNA1327134 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1327134). This includes whole-genome Illumina sequencing data for 45 representative ST848 isolates and Sanger sequencing data for the complete pmrCAB operon in 465 isolates. Additional metadata (e.g., isolate source, MICs, MLST/cgMLST, resistance mutations) are also available. The genome submission ID is SUB15626632; this identifier can be used by reviewers to access the data during peer review via the NCBI Submission Portal. All other supporting datasets, including lipid A mass spectrometry profiles, phenotypic assays, and analysis scripts, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Russo, A. & Serapide, F. The multifaceted landscape of healthcare-associated infections caused by carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii. Microorganisms 13 (4), 829 (2025).

Jiang, Y. et al. Carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii: A challenge in the intensive care unit. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1045206 (2022).

Yang, S., Wang, H., Zhao, D., Zhang, S. & Hu, C. Polymyxins: Recent advances and challenges. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1424765 (2024).

Gajic, I. et al. A comprehensive overview of antibacterial agents for combating Multidrug-Resistant bacteria: the current landscape, development, future opportunities, and challenges. Antibiotics 14 (3), 221 (2025).

Cogliati Dezza, F. et al. Risk factors for carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) bloodstream infections and related mortality in critically ill patients with CRAB colonization. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 5 (4), dlad096 (2023).

Chamoun, S. et al. Colistin dependence in extensively Drug-Resistant acinetobacter baumannii strain is associated with IS Ajo2 and IS Aba13 insertions and multiple cellular responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (2), 576 (2021).

Bhagirath, A. Y. et al. Two component regulatory systems and antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (7), 1781 (2019).

Halder, G. et al. Emergence of concurrently transmissible mcr-9 and carbapenemase genes in bloodborne colistin-resistant Enterobacter cloacae complex isolated from ICU patients in Kolkata, India. Microbiol. Spectr. 13 (3), e01542–e01524 (2025).

Chen, H. D. & Groisman, E. A. The biology of the PmrA/PmrB two-component system: the major regulator of lipopolysaccharide modifications. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 67, 83–112 (2013).

Butters, A. et al. PmrB Y358N, E123D amino acid substitutions are not associated with colistin resistance but with phylogeny in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 12 (10), e00532–e00524 (2024).

Hamidian, M. & Nigro, S. J. Emergence, molecular mechanisms and global spread of carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii. Microb. Genomics. 5 (10), e000306 (2019).

Al-Rashed, N. et al. Prevalence of carbapenemases in carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii isolates from the Kingdom of Bahrain. Antibiotics 12 (7), 1198 (2023).

Wajid Odhafa, M. et al. The context of Bla OXA – 23 gene in Iraqi carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii isolates belonging to global clone 1 and global clone 2. BMC Res. Notes. 17 (1), 300 (2024).

Kanaan, M. H. & Khashan, H. T. Molecular typing, virulence traits and risk factors of pandrug-resistant acinetobacter baumannii spread in intensive care unit centers of Baghdad City. Iraq Reviews Res. Med. Microbiol. 33 (1), 51–55 (2022).

Douraghi, M. et al. Accumulation of antibiotic resistance genes in carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii isolates belonging to lineage 2, global clone 1, from outbreaks in 2012–2013 at a Tehran burns hospital. Msphere 5 (2), 10–128 (2020).

Saki, M., Amin, M., Savari, M., Hashemzadeh, M. & Seyedian, S. S. Beta-lactamase determinants and molecular typing of carbapenem-resistant classic and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates from Southwest of Iran. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1029686 (2022).

Gupta, N., Angadi, K. & Jadhav, S. Molecular characterization of carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii with special reference to carbapenemases: A systematic review. Infect. Drug Resist. 31, 7631–7650 (2022 Dec).

Magiorakos, A. P. et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18 (3), 268–281 (2012).

El Hamidi, A., Tirsoaga, A., Novikov, A., Hussein, A. & Caroff, M. Microextraction of bacterial lipid A: Easy and rapid method for mass spectrometric characterization. J. Lipid Res. 46 (8), 1773–1778 (2005).

Shahab, M. et al. Investigating the role of PmrB mutation on colistin antibiotics drug resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 281, 136414 (2024).

Day, W. A. Jr, Fernández, R. E. & Maurelli, A. T. Pathoadaptive mutations that enhance virulence: Genetic organization of the CadA regions of Shigella spp. Infect. Immun. 69 (12), 7471–7480 (2001).

Ali, L. et al. A mechanistic Understanding of the effect of Staphylococcus aureus VraS histidine kinase single-point mutation on antibiotic resistance. Microbiol. Spectr. 13 (5), e00095–e00025 (2025).

Servetas, S. L., Whitmire, J. M. & Merrell, D. S. Generation of isogenic mutant strains of Helicobacter pylori. InHelicobacter Pylori 2021 Mar 26 (pp. 107–122). New York, NY: Springer US.

Melnyk, A. H., Wong, A. & Kassen, R. The fitness costs of antibiotic resistance mutations. Evol. Appl. 8 (3), 273–283 (2015).

Vogwill, T. & MacLean, R. C. The genetic basis of the fitness costs of antimicrobial resistance: A meta-analysis approach. Evol. Appl. 8 (3), 284–295 (2015).

Islam, M. M., Jung, D. E., Shin, W. S. & Oh, M. H. Colistin resistance mechanism and management strategies of colistin-resistant acinetobacter baumannii infections. Pathogens 13 (12), 1049 (2024).

Froelich, J. M., Tran, K. & Wall, D. A PmrA constitutive mutant sensitizes Escherichia coli to deoxycholic acid. J. Bacteriol. 188 (3), 1180–1183 (2006).

Tamayo, R., Ryan, S. S., McCoy, A. J. & Gunn, J. S. Identification and genetic characterization of PmrA-regulated genes and genes involved in polymyxin B resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 70 (12), 6770–6778 (2002).

Xu, Z. et al. Impact of PmrA on cronobacter Sakazakii planktonic and biofilm cells: A comprehensive transcriptomic study. Food Microbiol. 98, 103785 (2021).

Bollen, C., Louwagie, E., Verstraeten, N., Michiels, J. & Ruelens, P. Environmental, mechanistic and evolutionary landscape of antibiotic persistence. EMBO Rep. 24 (8), e57309 (2023).

Lee, H., Hsu, F. F., Turk, J. & Groisman, E. A. The PmrA-regulated PmrC gene mediates phosphoethanolamine modification of lipid A and polymyxin resistance in Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 186 (13), 4124–4133 (2004).

Phan, M. D. et al. Modifications in the PmrB gene are the primary mechanism for the development of chromosomally encoded resistance to polymyxins in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 (10), 2729–2736 (2017).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB): An urgent public health threat in United States healthcare facilities [Internet]. CDC; 2021 [cited 2023 May 19]. arpsp. cdc. gov/ story/ cra- urgent- public-health- threat.

Huang, X. et al. Global trends of antimicrobial resistance and virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae from different host sources. Commun. Med. 5 (1), 383 (2025).

Kapel, N., Caballero, J. D. & MacLean, R. C. Localized PmrB hypermutation drives the evolution of colistin heteroresistance. Cell. Rep. ;39(10). (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Risk prediction of 30-day mortality after stroke using machine learning: A nationwide registry-based cohort study. BMC Neurol. 22 (1), 195 (2022).

Tozluyurt, A. Molecular typing of reduced susceptibility of acinetobacter calcoaceticus–baumannii complex to chlorhexidine in Turkey by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Med. Microbiol. 73 (8), 001882 (2024).

Funding

This study was funded by the Faculty of Medicine, Tehran Medical Sciences, Islamic Azad University, [Grant Number IAUTM-14021012]

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions: K, A; Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing. K. B, P.J, K. K, H. H: Investigation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization, Project Administration (under supervision).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bazyar, K., Jamali, P., Kalantar, K. et al. Mechanistic and clinical insights into a PmrB mutation driving colistin resistance and virulence in Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci Rep 16, 4348 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33812-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33812-y