Abstract

Genotype-guided warfarin dosing has shown improved anticoagulation outcomes in individuals of European and Asian ancestry. However, its usefulness in specific subgroups remains uncertain. This open-label, non-inferiority randomized trial (NCT00700895) was conducted across three academic hospitals in Southeast Asia to assess the utility of genotype-guided warfarin dosing in Asian patients, focusing on specific potentially high-risk subgroups. We enrolled 322 newly initiated warfarin patients. The primary endpoint was the number of dose adjustments within the first 14 days of treatment, with a non-inferiority margin of 0.5. Clinical follow-up lasted 90 days. Among 322 randomized patients, 269 (mean age 58.7 years, 59.9% males) were evaluated for the primary endpoint. The pharmacogenetic algorithm significantly reduced dose titrations during the initial 14 days compared to the traditional dosing algorithm, without compromising safety. This benefit was consistent in those with atrial fibrillation (N = 101, mean difference -1.63, 95% CI -2.16 to -1.10), non-atrial fibrillation indications (N = 165, mean difference -0.88, 95% CI -1.26 to -0.49), stroke-only indications (N = 19, mean difference -1.60, 95% CI -2.83 to -0.37), history of acute myocardial infarction (N = 20), congestive heart failure (N = 34), hypertension (N = 152), diabetes mellitus (N = 95), and across races (Chinese, N = 163; Malay, Indian and Others, N = 104), sexes (female, N = 161 and male, N = 108), and age groups (< 65 years, N = 168 and ≥ 65 years, N = 101). However, no significant reduction was observed in patients with a history of stroke. There were no differences in minor or major bleeding complications, recurrent venous thromboembolism, or out-of-range INR measurements across most subgroups. Healthcare providers may consider using pharmacogenetic algorithms to individualize initial warfarin dosages in specific high risk Asian subpopulations.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00700895 (19/06/2008).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The administration of warfarin has traditionally relied on an empirical dose initiation protocol, which remains prevalent in current practice1. However, most patients initiated on warfarin struggle to maintain a long-term stable international normalized ratio (INR)2. This challenge is in part due to inter-individual variability in dose response, influenced by polymorphisms in cytochrome P450 2C9 (CYP2C9) and vitamin K epoxide reductase complex 1 (VKORC1)3. Hence, genotype-guided dosing algorithms that account for genetic polymorphisms such as the VKORC1 H1/H1 haplotype and the CYP2C9*3 allele have been investigated, and shown to provide benefits over traditional dosing strategies4,5,6,7.

Syn et al., 20181 was the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the use of a warfarin pharmacogenetic algorithm in an ethnogeographically diverse Asian population. The study demonstrated a significant reduction in the number of dose titrations during the initial 14 days and over the first three months of treatment when compared to the traditional dosing algorithm in the overall population.1 However, the percentage of patients achieving stable INR, the median time to stable INR, and the percentage of time spent in the therapeutic range (PTTR) did not differ significantly.1 There was no compromise on safety outcomes. These findings were largely consistent with other subsequent Asian studies.8,9

Despite these advances, evidence regarding the efficacy of the pharmacogenetic algorithm within various patient groups remains limited. Patients such as with congestive heart failure (CHF), a history of stroke, or older adults who have reduced mobility could derive greater benefit from genotype-guided dosing. Determining whether the pharmacogenetic algorithm’s efficacy is consistent within these potentially high risk subgroups may inform targeted implementation of pharmacogenetic strategies in clinical practice.

To address this gap, the present study aims to assess whether the efficacy of the warfarin pharmacogenetic algorithm observed in Syn et al., 2018 persists in potentially high risk groups, using trial data in which subgroup analyses had not previously been conducted. These findings may help guide genotype-guided dosing into clinical workflows for populations most likely to benefit, thereby supporting more personalized care and optimizing therapeutic outcomes.

Methods

Study design

This analysis includes individual patient data from the completed open-label, non-inferiority, RCT by Syn et al., 2018 (Identifier: NCT00700895 [19/06/2008]).1 The study protocol (PG01/11/06) was approved by the Domain Specific Review Board of the National Healthcare Group. It was conducted in three large tertiary hospitals in Southeast Asia – National University Hospital, Singapore; University of Malaya Medical Centre, Malaysia; Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore. Patients had to have a new indication of long-term anticoagulation with warfarin and no medical conditions contraindicating its use. Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to either genotype-guided dosing of warfarin or the traditional dosing approach. All patients were initiated on low-molecular weight heparin at randomization, prior to the availability of genotyping results. Those allocated to the genotype-guided dosing arm received warfarin doses determined by a pharmacogenetic algorithm for three consecutive days. This algorithm is a function of age, weight, the presence of the CYP2C9*3 allele, and VKORC1 genotype. Conversely, participants in the standard dosing arm were managed using the protocol employed by the National University Hospital Anticoagulation Clinic. This regimen consisted of orally-administered warfarin 5 mg on days 1 and 2, followed by 3 mg on day 3. For patient aged > 75 years, the dose on day 2 was reduced to 4 mg. INR checks during the first 14 days – specifically day 6, between days 7 to 9, and between days 12 and 14 were mandatory. These measurements provided the baseline for subsequent warfarin dose titrations and/or decisions to stop low-molecular weight heparin treatment. Patients were followed up to day 90 following initiation of warfarin.

The primary outcome was the number of dose titrations performed up to day 14. All outcomes were assessed only in patients who completed at least 14 days of genotype-guided or traditional dosing therapy, in a modified intention-to-treat principle without imputation. Secondary outcomes included (1) median time to stable INR, defined as the number of days from warfarin initiation to attaining therapeutic INR (≥ 1.9 and ≤ 3.1) for the latter of two consecutive measurements that are at least 7 days apart; (2) PTTR, which was estimated using the linear interpolation method of Rosendaal et al., 199310; (3) incidence of dose adjustments throughout the follow-up period; (4) frequency of INR measurements during follow-up; proportion of patients who had an incidence of (5) minor bleeding episode, (6) major bleeding episode, (7) recurrent venous thromboembolism, (8) any measured INR value ≤ 1.9 or (9) any measured INR value ≥ 3.1 throughout the entire duration of follow-up. Full details of the trial have been previously published by Syn et al., 2018.1

Statistical analysis

The trial was powered to establish non-inferiority of genotype-guided warfarin dosing strategy over traditional clinical warfarin dosing strategy using the primary outcome of the number of dose titrations within the first 14 days. Non-inferiority would be established if the upper limit of the 90% confidence interval (CI) for the mean difference between treatment groups did not exceed the pre-defined non-inferiority margin of 0.5. If non-inferiority was demonstrated, a two-tailed t test with an alpha value of 0.05 was conducted to test for superiority.

Analysis of secondary outcomes were tests of superiority of genotype-guided dosing against traditional dosing, with significance defined as two-tailed nominal P < 0.05. The median time to stable INR was evaluated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and difference was evaluated via the log-rank test. PTTR was compared using two-sample t tests. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were estimated with mixed effects Poisson regression models to compare the incidence of dose adjustments and frequency of INR measurements throughout the entire duration of follow-up. The model adjusted for possible intra-subject correlation of count data measured at 1, 2, and 3 months, and accounted for reduced follow-up duration amongst patients who withdrew or discontinued the trial before day 90 via an exposure variable in the Poisson regression for the number of days on trial. In addition, we calculated predicted incidences of dose adjustments and INR measurements using Stata’s post-estimation command. Relative risks (RRs), P values provided by Fisher’s exact test, and 95% CIs derived from exact binomial distributions were used to evaluate the differences in the proportion of patients who experienced minor bleeding, major bleeding, recurrent venous thromboembolism, and at least one incidence of any measured INR value ≤ 1.9 or ≥ 3.1 between the two arms. The number needed to treat (NNT) was derived from the RRs by calculating the reciprocal of the absolute risk reduction. This was only performed for outcomes/subgroups in which the RRs were significant. Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome and all secondary outcomes are performed in a similar manner to the original paper. Exploratory analyses regarding the percentage of time spent within a therapeutic range instead defined as (INR ≥ 2.0 and INR ≤ 3.0), and the proportion of patients with an incidence of any measured INR value ≤ 2.0 and ≥ 3.0 are performed. The results of the subgroup analysis are summarized in forest plots.

The subgroups are defined as indication for initiation of warfarin therapy due to atrial fibrillation (AF), non-AF indications including stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, left ventricular thrombus, and stroke-only indications. Seven subgroups are defined by patients’ medical history of stroke, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), CHF, hypertension (HTN), and diabetes mellitus (DM). 74% of Chinese individuals carry the high warfarin sensitivity VKORC1 H1/H1 haplotype, which broadly indicates the need for a lower dosage of warfarin for Chinese individuals in comparison to Malay (42%) and Indian (7%) individuals11. In contrast, a larger proportion of Indian individuals (18%) carry the poor warfarin metabolizer CYP2C9*3 allele, over Chinese (7%) and Malay (9%) individuals11, that loosely indicates the need for a reduced warfarin dosage for Indian individuals, to prevent INR from going above the therapeutic range. It is thus evident that differences in race, even within the selected Asian population, influences outcomes of warfarin therapy. Hence, subgroup analysis of racial groups, grouped as Chinese only, Malay, Indian and others – whilst in consideration of sample size, is also performed. In addition, it may be useful to examine sex subgroups, as western studies have reported a significantly shorter PTTR in women than men12. As individuals above the age of 65 years are perceived to be at greatest risk of warfarin-related bleeding events13, subgroups of patients < 65 years old and ≥ 65 years old were also evaluated. Statistical analyses were performed in Stata version 16.0 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX, USA), and Review Manager (RevMan) Version 5.414 was used to pool the results according to subgroup.

Results

Between May 2007 and July 2016, a total of 334 patients were screened for eligibility. Of these, 322 met the inclusion criteria and were subsequently randomised, with 159 allocated to the genotype-guided dosing arm and 163 assigned to the traditional dosing arm. The baseline characteristics per arm are presented in Table 11. Both arms exhibited no significant difference in baseline characteristics and genotypic distributions. 12 patients originally in the genotype-guided arm were switched to the traditional dosing arm as genotype results were not available by day 5. 133 genotype-guided dosing and 136 traditional dosing patients were included in the final modified intention-to-treat analysis, the remainder of which were excluded as they discontinued the study or were lost to follow-up before 14 days. The median duration of warfarin therapy was comparable between the two arms – 90.0 days in the genotype-guided dosing group (interquartile range 83.8 to 90.0 days) and 90.0 days in the traditional dosing group (interquartile range 77.0 to 90.0 days). There was also no evidence of difference (P > 0.05) in the time spent on warfarin therapy across all subgroups.

Primary outcome

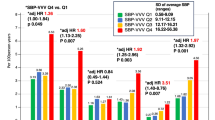

The average number of dose titrations performed up to day 14 was significantly lower in the genotype-guided dosing arm as compared to the traditional dosing arm across the majority of patient subgroups – AF indication, non-AF indications, stroke-only indication, history of AMI, history of CHF, history of HTN, history of DM, Chinese, Malay, Indian and other races, male, female, < 65 years old, and ≥ 65 years old (Fig. 1). However, the difference was not significant in the subgroup of patients with a history of stroke. With regards to the IRRs evaluating the incidence of dose titrations up to day 14, genotype-guided dosing similarly showed superiority across most subgroups, except for those with a history of stroke and CHF (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S1). The average number of dose titrations per arm in each subgroup was also summarized in Table 2.

Secondary outcomes

The median time to stable INR per subgroup is summarized in Table 3. The 75th percentile for median time to stable INR could not be derived for some subgroups, because less than 75% of patients had achieved stable INR, and thus were reported as NA. In absolute terms, a greater percentage of patients from the genotype-guided dosing arm achieved stable INR as compared to the traditional dosing arm in the AF indication, stroke indication, history of AMI, history of HTN, history of DM, female, and ≥ 65 years old subgroups. In contrast, a greater percentage of patients that achieved stable INR in the traditional dosing arm came from the non-AF indication, history of stroke, history of CHF, Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Others, Male, and < 65 years old subgroups. However, the hazard ratios for attaining stable INR (Fig. 2), was not statistically different between dosing arms across all subgroups.

The mean difference in the percentage of time in the pre-specified therapeutic range (INR 1.9 to 3.1) between the genotype-guided dosing arm and the traditional dosing arm only reached statistical significance in the subgroup of patients with a history of stroke (MD -27.67%, 95% CI -44.78% to -10.57%, p = 0.003). It was the only subgroup that favored the traditional dosing algorithm (Fig. 3A). However, there was no evidence of difference between the two dosing groups in this subgroup once the designated therapeutic range was modified to INR 2.0 to 3.0 (MD -14.26%, 95% CI -35.66% to 7.14%, p = 0.180). In this exploratory analysis, the genotype-guided dosing algorithm was significantly associated with a greater PTTR in the subgroups of patients with warfarin indication due to stroke alone, history of AMI and history of HTN, but not for the remaining subgroups (Fig. 3B).

The incidence of dose adjustments was significantly decreased with the genotype-guided dosing arm versus the traditional dosing arm over the first three months of treatment across majority of subgroups, after adjusting for within-individual correlations in repeated measurements and differences in between-individual exposure duration using a log-linear mixed effects Poisson model. The reduction did not reach statistical significance in the subgroup of patients initiated on warfarin due to stroke alone and in the subgroup of patients with a history of stroke (Fig. 4A). In addition, the incidence of INR measurements over the first three months of treatment was significantly reduced by genotype-guided dosing only in the AF indication subgroup and the female subgroup (Fig. 4B).

The incidence of minor bleeding (Supplementary Figure S2), major bleeding (Supplementary Figure S3), recurrent venous thromboembolism (Supplementary Figure S4) were not statistically different (P > 0.05) between the genotype-guided and traditional dosing arms for all subgroups. In addition, the incidence of any measured INR value below 1.9 (Supplementary Figure S5) did not differ significantly between dosing arms for most subgroups. However, among patients with a history of diabetes, an INR value of < 1.9 was recorded at least once in all 46 patients in the genotype-guided dosing arm versus 45/49 patients in the traditional dosing arm. Hence, genotype-guided dosing may be associated with an increased risk of INR being < 1.9 (RR 1.09, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.19, p = 0.047). The NNT for one additional diabetic patient to have at least one incidence of INR < 1.9 is 12.25. Conversely, differences in the incidence of INR values above 3.1 were not significant across all subgroups (Supplementary Figure S6). Exploratory analysis showed no significant difference in the proportion of patients with at least one recorded INR < 2.0 and > 3.0 between dosing arms for most subgroups (Supplementary Figure S7 and S8 respectively). The only exception was in the Malay, Indian and other races subgroup, where the incidence of at least on measured INR > 3.0 occurred in 31/49 patients in the genotype-guided arm compared to 21/55 patients in the traditional dosing arm. This subgroup of patients demonstrated a significantly greater risk of INR being > 3.0 (RR 1.66, 95% CI 1.11 to 2.47, p = 0.013). The NNT for one additional patient whose race was either Malay, Indian or others to have at least one recorded INR > 3.0 is 3.99.

The predictive performance of the pharmacogenetic maintenance dose model was also evaluated (Supplementary Table S1). The predicted daily maintenance dosages correlated positively with actual documented stable dosages in the non-AF indication, stroke indication, history of AMI , history of CHF, male, and less than 65 years old subgroups, thereby indicating a respectable level of predictive accuracy with a positive forecast bias. However, the model did not correlate as well within the subgroups of AF indication, history of stroke, history of HTN, history of DM, Chinese, Malay, Indian, and others, Female, and the more than or equal to 65 years old subgroup. Hence, predictive accuracy of the pharmacogenetic maintenance dose model may be reduced in these subgroups.

Discussion

In this subgroup analysis of 322 Asian patients newly indicated for warfarin, we found that the pharmacogenetic dosing algorithm outperformed traditional dosing protocols in most subgroups concerning the number of dose titrations required within the first 14 days and the first three months of treatment. Notably, there was a significant increase in the PTTR with genotype-guided dosing in patients with stroke-only indication, history of AMI, and history of HTN. A key confounder to consider when interpreting these results is the differing frequencies of dose adjustments and INR monitoring in the two dosing arms. It underscores the benefit of the genotype-guided strategy, which achieved higher PTTR with fewer dose titrations and INR measurements in the aforementioned subgroups. The median time to stable INR and the percentage of patients who achieved stable INR were similar between the two dosing arms, showing no statistical significance in the HRs of attaining stable INR. In addition, there was no significant difference in the incidence of safety outcomes. The extent of positive correlation and predictive accuracy of the model varied when applied to the different subgroups. Given the pharmacogenetic dosing algorithm’s superiority in the primary outcome and its comparability in secondary outcomes to traditional dosing in most patient subgroups, genotype-guided dosing appears to be beneficial for a broad range of patient types in the Asian population.

Our findings are consistent with prior Asian studies8,9, which demonstrate a shorter median time to stable INR, fewer dose adjustments and no difference in the incidence of safety outcomes with genotype-guided dosing when compared to traditional dosing of warfarin. Of note, these studies also highlighted a significant improvement in PTTR with genotype-guided dosing in their population of Chinese patients8,9. However, the present study did not observe this significant increase in the Chinese-only subgroup, although a positive trend can be noted. It may be important to consider that the relatively small sample sizes in our subgroups may exert influence over the results, allowing potential trends to emerge without reaching statistical significance.

The benefit of genotype-guided dosing is particularly noteworthy in specific subgroups, especially patients with an indication for warfarin due to AF. Adequate anticoagulation is important in this subgroup, as inadequate levels significantly elevate the risk of left atrial thrombi, and subsequent thromboembolic events15. Given that the genotype-guided dosing enabled more patients to achieve stable INR with fewer INR measurements and dose adjustments, it is likely to be highly beneficial for patients with AF. This emphasizes the importance of considering genotype-guided dosing in contexts where maintaining stable anticoagulation is critical. On the other hand, patients with a history of AMI are often put on concurrent antiplatelet therapy based on 2016 guidelines from American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA)16. A synergistic effect with anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy likely carries an increased hemorrhagic risk17. Therefore, the importance of maintaining within the therapeutic range of warfarin is even more significant. The pharmacogenetic algorithm’s ability to enhance time in PTTR and increase the likelihood of achieving stable INR underscores its value for patients with a history of AMI. It is also useful to consider the use of genotype-guided dosing in patients with a history of CHF18, or are above or equal to the age of 6519, who often suffer from mobility issues, which alludes to potential challenges in attending the scheduled warfarin titration appointments. Hence, given the genotype-guided strategy’s correlation with reduced dose adjustments through the first 14 days and entire follow-up duration in these specific subgroups, it is likely to be of added value to these patient types.

A notable exception that begs further consideration with regards to the use of genotype-guided dosing algorithm would be patients with a history of stroke. First, the difference in the number of dose adjustments over the first 2 weeks and throughout the follow-up period was not significant unlike other subgroups. Second, the HRs of attaining stable INR was decreased with the genotype-guided dosing algorithm, although not statistically significant. Third, the genotype-guided dosing algorithm was associated with a shorter percentage of time spent in both therapeutic ranges – INR 1.9 to 3.1 (P < 0.05) and INR 2.0 to 3.0 (P > 0.05). In addition, there was no observed difference in the frequency of INR measurements, and the incidence of safety outcomes over the duration of follow-up. The analysis also indicates that the genotype-guided dosing algorithm may be unable to accurately predict the maintenance dose requirements. Hence, given the lack of a generally consistent benefit across all study outcomes, the genotype-guided dosing algorithm may not confer an advantage over the traditional dosing algorithm in individuals with a history of stroke. It may be useful, however, to consider the potential influence of external factors on these results. Patients commonly receive multiple medications20 following stroke, which could interact unpredictably with warfarin, thereby affecting its anticoagulant efficacy21. Moreover, nutritional deficiencies observed post-stroke22,23, and metabolic alterations both locally in the liver and systemically24,25, could complicate warfarin metabolism. Further study is therefore required to ascertain the utility of genotype-guided dosing in patients with a history of stroke.

Of note, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have become the predominant oral anticoagulant in many settings, with a decline in the use of warfarin. DOACs offer practical advantages, including fixed dosing and fewer follow-up requirements, and have demonstrated improved efficacy and safety outcomes in conditions like AF26. However, warfarin still remains the preferred anticoagulant in certain situations – including patients with mechanical heart valves, antiphospholipid syndrome, severe renal impairment, or in patients with high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding27. The persistent clinical relevance of warfarin thus underscores the continued importance of strategies to optimize its use, such pharmacogenetic dosing algorithms, even in the era of DOACs. In addition, some studies have reported that genotype-guided warfarin dosing may be cost-effective in patients with AF28,29. These costs are likely to continue to fall. Hence, broader implementation of genotype-guided dosing has the potential to further improve the safety and practicality of warfarin usage, and may help maintain its role as a viable alternative to DOACs in the future.

This study has several limitations. First, the total sample size was modest (N = 322), and further subdivision into subgroups reduces overall statistical power. In addition, the study was underpowered to perform formal subgroup interaction testing. However, given that subgroup effect estimates were directionally consistent and their confidence intervals demonstrated substantial overlap, the likelihood that these limitations materially affected the overall interpretation is low. Second, multiplicity adjustments were not applied in the subgroup analyses. Although such corrections can mitigate the risk of type 1 error inflation, they may be overly conservative in smaller exploratory studies and obscure potentially meaningful clinical signals. Accordingly, our findings need to be considered within one’s own clinical practice and in the context of individual patient characteristics. Notably, the subgroup analyses were intended to be hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory. Future research are needed to evaluate these potential effect modifiers more definitively. Third, CYP4F2 polymorphisms have also been implicated in warfarin dose variability30. This variant was not incorporated into the pharmacogenetic algorithm used in the present study. Hence, subsequent work should therefore evaluate whether inclusion of CYP4F2 may enhance dose prediction, either in addition to or in comparison with CYP2C9.

Conclusion

In this subgroup analysis of a randomized, non-inferiority clinical trial that included 322 Asian adults, genotype-guided dosing was associated with a decrease in the number of dose titrations within the first 14 days compared to traditional dosing across several high risk patient subgroups. These findings suggest that a pharmacogenetic algorithm may help optimize warfarin dosing in potentially high risk patient groups for whom improved dosing precision is likely to be clinically meaningful.

Data availability

The dataset used and/or analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- CYP2C9:

-

Cytochrome P450 2C9

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- DOAC:

-

Direct oral anticoagulant

- HTN:

-

Hypertension

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- IRR:

-

Incidence rate ratio

- NNT:

-

Number needed to treat

- PTTR:

-

Percentage of time spent in therapeutic range

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- RMSE:

-

Root mean-squared error

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- VKORC1:

-

Vitamin K epoxide reductase complex 1

References

Syn, N. L. et al. Genotype-guided versus traditional clinical dosing of warfarin in patients of Asian ancestry: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 16, 104 (2018).

Pokorney, S. D. et al. Stability of International Normalized Ratios in Patients Taking Long-term Warfarin Therapy. JAMA 316, 661–663 (2016).

Johnson, J. A. & Cavallari, L. H. Warfarin pharmacogenetics. Trends. Cardiovasc. Med 25, 33–41 (2015).

Anderson, J. L. et al. A randomized and clinical effectiveness trial comparing two pharmacogenetic algorithms and standard care for individualizing warfarin dosing (CoumaGen-II). Circulation 125, 1997–2005 (2012).

Pirmohamed, M. et al. A randomized trial of genotype-guided dosing of warfarin. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 2294–2303 (2013).

Kimmel, S. E. et al. A Pharmacogenetic versus a Clinical Algorithm for Warfarin Dosing. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 2283–2293 (2013).

Gage, B. F. et al. Effect of Genotype-Guided Warfarin Dosing on Clinical Events and Anticoagulation Control Among Patients Undergoing Hip or Knee Arthroplasty: The GIFT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 318, 1115–1124 (2017).

Guo, C. et al. Genotype-Guided Dosing of Warfarin in Chinese Adults: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Circ. Genom. Precis Med 13, e002602 (2020).

Zhu, Y., Xu, C. & Liu, J. Randomized controlled trial of genotype-guided warfarin anticoagulation in Chinese elderly patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 45, 1466–1473 (2020).

Rosendaal, F. R., Cannegieter, S. C., van der Meer, F. J. & Briët, E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb. Haemost. 69, 236–239 (1993).

Lee, S. C. et al. Interethnic variability of warfarin maintenance requirement is explained by VKORC1 genotype in an Asian population. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 79, 197–205 (2006).

Lee, K. K. et al. Sex Differences in Oral Anticoagulation Therapy in Patients Hospitalized With Atrial Fibrillation: A Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, e027211 (2023).

Choudhry, N. K. et al. Impact of adverse events on prescribing warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: matched pair analysis. BMJ 332, 141–145 (2006).

Collaboration, T. C. Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020).

Lurie, A. et al. Prevalence of Left Atrial Thrombus in Anticoagulated Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 77, 2875–2886 (2021).

Kamran, H. et al. Oral Antiplatelet Therapy After Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Review. JAMA 325, 1545–1555 (2021).

Eikelboom, J. W. & Hirsh, J. Combined antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy: clinical benefits and risks. J. Thromb. Haemost. 5(Suppl 1), 255–263 (2007).

van den Berg-Emons, H., Bussmann, J., Balk, A., Keijzer-Oster, D. & Stam, H. Level of activities associated with mobility during everyday life in patients with chronic congestive heart failure as measured with an “activity monitor”. Phys. Ther. 81, 1502–1511 (2001).

Walsh, K., Roberts, J. & Bennett, G. Mobility in old age. Gerodontology 16, 69–74 (1999).

Cadel, L. et al. Medication self-management interventions for persons with stroke: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 18, e0285483 (2023).

Stöllberger, C., Schneider, B. & Finsterer, J. Drug-drug interactions with direct oral anticoagulants for the prevention of ischemic stroke and embolism in atrial fibrillation: a narrative review of adverse events. Expert. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 16, 313–328 (2023).

Huppertz, V. et al. Impaired Nutritional Condition After Stroke From the Hyperacute to the Chronic Phase: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurol. 12, 780080 (2021).

Krishnaswamy, K. Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics in Malnutrition. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 3, 216–240 (1978).

Wesley, U. V., Bhute, V. J., Hatcher, J. F., Palecek, S. P. & Dempsey, R. J. Local and systemic metabolic alterations in brain, plasma, and liver of rats in response to aging and ischemic stroke, as detected by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Neurochem. Int. 127, 113–124 (2019).

Petersson, J. N. et al. Unraveling Metabolic Changes following Stroke: Insights from a Urinary Metabolomics Analysis. Metabolites 14, 145 (2024).

Carnicelli, A. P. et al. Direct Oral Anticoagulants Versus Warfarin in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Patient-Level Network Meta-Analyses of Randomized Clinical Trials With Interaction Testing by Age and Sex. Circulation 145, 242–255 (2022).

Wadsworth, D. et al. A review of indications and comorbidities in which warfarin may be the preferred oral anticoagulant. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 46, 560–570 (2021).

Verhoef, T. I. et al. Cost-effectiveness of pharmacogenetic-guided dosing of warfarin in the United Kingdom and Sweden. Pharmacogenomics J. 16, 478–484 (2016).

Patrick, A. R., Avorn, J. & Choudhry, N. K. Cost-Effectiveness of Genotype-Guided Warfarin Dosing for Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2, 429–436 (2009).

Sun, X., Yu, W. Y., Ma, W. L., Huang, L. H. & Yang, G. P. Impact of the CYP4F2 gene polymorphisms on the warfarin maintenance dose: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed. Rep. 4, 498–506 (2016).

Funding

The original investigator-initiated trial was funded by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council (NMRC/CSA/021/2010 and NMRC/CSA/0048/2013). The Surveillance and Pharmacogenomics Initiative for Adverse Drug Reactions (SAPhIRE) program is supported by a Strategic Position Funds Grant (SPF2014/001) from the Biomedical Research Council of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR). The research was also supported by the National Research Foundation Singapore and the Singapore Ministry of Education under their Research Centres of Excellence Initiative.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HJW, YNT, YHT, NLS, ALW, HLT, RS, SCL, BCG and CHS wrote the manuscript. HJW, YNT, YHT, NLS, ALW, HLT, RS, SCL, BCG and CHS designed the research. HJW, YNT, YHT, NLS, ALW, HLT, RS, SCL, BCG and CHS performed the research. HJW, YNT, YHT and NLS analyzed the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics review committee at the Domain Specific Review Board of the National Healthcare Group approved the protocol (PG01/11/06). The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and patients provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. All serious adverse events were reported to the Domain Specific Review Board and the Medical Clinical Research Committee, Ministry of Health in accordance with published guidelines. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT00700895 [19/06/2008]).

Consent for publication

Obtained as part of informed consent taking during the original study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, H., Teo, Y., Teo, Y. et al. Subgroup analysis of genotype guided vs traditional warfarin dosing in Asian patients from an open label randomized trial. Sci Rep 16, 3670 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33831-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33831-9