Abstract

The rational selection of laser wire-stripping parameters is essential for achieving high processing quality and efficiency. This study investigates 8-AWG aviation cables insulated with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and employs a 405 nm diode laser to determine the optimal stripping conditions. A thermo-mechanically coupled finite-element model was established in COMSOL by integrating an interface-tracking scheme, an appropriate volumetric heat-source model, and realistic boundary conditions. Using a single-factor methodology, the effects of laser power, scanning speed, and processing time on stripping quality were systematically examined. The results indicate that increasing laser power significantly enhances stripping efficiency but simultaneously causes wider kerfs, larger heat-affected zones (HAZ), and greater thermal-expansion displacement. Higher scanning speeds effectively reduce kerf width, although potentially at the expense of processing efficiency, while moderate extensions of processing time lead to limited increases in cutting depth. By optimizing the combined parameters, stripping efficiency can be improved without compromising quality. Furthermore, a three-factor, three-level orthogonal experiment was conducted. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that laser power is the dominant factor affecting kerf depth and width, HAZ size, and thermal-expansion displacement. Through multi-objective optimization based on a binary satisfaction criterion, together with an energy-efficiency evaluation to quantify cutting performance, the optimal parameter set for PTFE insulation stripping of 8-AWG cables was determined to be a laser power of 0.9 W, a scanning speed of 3 r/s, and a processing time of 8 s. Finally, quantitative comparisons between simulation and experimental results under three identical parameter sets confirmed the model’s predictive accuracy, providing a solid theoretical and practical foundation for high-quality, high-efficiency laser stripping of PTFE insulation on large-diameter aviation cables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the aerospace industry, the processing quality of cable harnesses directly affects aircraft stability and safety. Among the various manufacturing steps, wire stripping is a critical process that requires extremely high precision and process control. At present, wire stripping is still largely performed manually. Due to the diversity of cable types and their complex structures (e.g., shielding layers, varying core strand counts), process inconsistency remains common, hindering technological advancement. Traditional stripping methods—including mechanical, thermal, and chemical techniques—are associated with limitations such as low efficiency, risk of core damage, thermal deformation of insulation layers, and chemical residue contamination1. These drawbacks make them unsuitable for high-reliability applications such as aerospace.

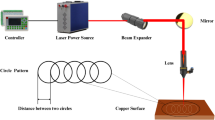

Laser wire stripping technology has emerged as a promising alternative. This method leverages the high energy density of laser beams to rapidly heat and vaporize insulating materials2,3, thereby removing the insulation layer. During processing, the laser rotates around the cable, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Compared with conventional methods, laser stripping offers distinct advantages, including non-contact operation, high precision, and excellent repeatability. As a result, it is increasingly adopted in high-end manufacturing and is gradually replacing traditional stripping techniques.

During laser stripping, the temperature distribution within the insulation layer determines the kerf depth and width, while also inducing a heat-affected zone (HAZ) and thermal expansion effects4. An excessively large HAZ directly degrades stripping quality and cable reliability, leading to reduced mechanical performance and shortened service life5. Moreover, steep temperature gradients can generate substantial thermal stress and deformation, thereby compromising the geometric accuracy and structural integrity of the kerf. According to the SAE-AIR6894 standard6, kerf width and HAZ are considered key indicators for assessing laser stripping quality.

Previous research on laser stripping has mainly examined processing mechanisms7,8,9,10,11,12, stripping techniques13,14,15,16, and parameter optimization. For example, Brannon H and Tam C et al.17 investigated polyurethane insulation stripping using KrF excimer and CO2 lasers, respectively. Their results showed that ultraviolet excimer lasers achieved cleaner cuts with uniform cross-sections, whereas infrared CO₂ lasers performed poorly due to polyurethane’s low absorption coefficient in that wavelength range. This highlighted the critical role of the material’s absorption coefficient in determining stripping quality and the importance of selecting a laser wavelength with strong material absorption.

Similarly, Lee J and Dhital D et al.18 studied cladding stripping in specialty optical fibers. They demonstrated that pulsed lasers can induce photochemical bond breaking in polymers, while continuous-wave lasers primarily remove hardened polymer cladding through photothermal mechanisms. Their findings indicated that combining low pulse energy with continuous-wave lasers enables effective cladding removal without damaging the fiber core. Marimuthu S and Kamara M et al.19 developed a finite element model to simulate laser stripping of thermal barrier coatings, predicting temperature distribution and ablation depth under different laser powers and scanning speeds. Experimental validation using nanosecond pulsed lasers showed strong agreement with the simulations. Their study confirmed that removal rates increase with higher laser power and decrease with faster scanning speed, underscoring the predictive value of finite element modeling in laser-material interactions.

Other researchers have explored aviation-related applications. Yang Guilin et al.20 investigated simultaneous stripping of insulation and shielding layers using YAG lasers. Through orthogonal experiments, they quantified the influence of parameters such as average power, scanning speed, frequency, and pulse width, and identified the optimal combination for improved stripping performance. Tang Hao, Zhang Qin et al.21,22 conducted experiments on polyimide-insulated wires, showing that laser power, stripping speed, and number of passes are critical factors affecting quality. Their work also confirmed the effectiveness of orthogonal experimental design in determining optimal process conditions.

Despite these advances, existing studies largely focus on kerf width, kerf depth, and HAZ formation in thin-gauge aviation cables (≤ 10 AWG). Investigations into thermo-mechanical coupling effects—specifically thermal stress distribution and thermal expansion—remain limited. Moreover, research on large-diameter aviation cables (≥ 6 AWG), which present unique challenges in insulation processing, is still scarce. Therefore, it is essential to analyze thermo-mechanical coupling mechanisms in large-diameter PTFE-insulated cables and to establish a comprehensive quality evaluation framework encompassing kerf geometry, HAZ, and thermal expansion effects.

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), synthesized from tetrafluoroethylene monomers23, is widely used as an insulation material in aviation cables owing to its excellent electrical insulation, high-temperature resistance, corrosion resistance, and aging stability. This study focuses specifically on the laser stripping of PTFE insulation.

To address current limitations, a thermo-mechanical coupling model was established on the COMSOL simulation platform to analyze the temperature field, kerf morphology, and stress distribution during stripping. Single-factor analysis was used to evaluate the effects of key processing parameters on stripping quality. In addition, a three-factor orthogonal experimental design—integrating multi-objective optimization and energy-efficiency quantification—was employed to determine the optimal parameter combination, providing theoretical and practical guidance for improving the efficiency and quality of PTFE insulation stripping in aviation harnesses.

Multiphysics coupling model

When the laser irradiates the surface of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), the material temperature rises progressively. PTFE undergoes an abrupt phase transition near 600 K, where it transforms from a semi-crystalline solid into an amorphous gel-like state24. When the temperature further increases to approximately 350–400 °C (623–673 K), pyrolysis begins, during which the polymer decomposes into gaseous products without forming either a char layer or a molten phase.

Geometric model

Considering the axial symmetry of the wire, a two-dimensional axisymmetric geometric model was established to reduce computational cost while maintaining accuracy, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The z-axis was defined as the axis of symmetry. The overall model dimensions are 1 mm × 0.8 mm. In the figure, the blue double-dashed line denotes the target material region (1 mm × 0.5 mm), where convective and radiative heat losses occur. The yellow solid line represents the air region, with dimensions of 1 mm × 0.3 mm. The red dashed line indicates the laser-irradiated region, measuring 0.5 mm × 0.8 mm.

The mesh configuration is illustrated in Fig. 2. In the laser interaction zone, a free quadrilateral mesh was applied with a maximum element size of 0.005 mm and a maximum growth rate of 1.1. The remaining domains were discretized using free triangular elements with a maximum element size of 0.05 mm and a maximum growth rate of 1.25. The final mesh consisted of 9,685 degrees of freedom, providing sufficient resolution for accurate simulation of heat transfer and thermo-mechanical coupling effects.

Interface tracking

The laser wire stripping process involves the evolution of two distinct interfaces: solid–gel and gel–gas. Owing to the differences in their underlying physical mechanisms, each interface requires a dedicated tracking approach.

To model the gelation or solidification process, while simultaneously accounting for convection and diffusion during the solid–gel phase transition, the enthalpy–porosity method is adopted25. This method effectively captures the phase transition dynamics by representing the coexistence region as a porous medium–like system, thereby enabling a realistic description of gradual transformations between solid and gel states:

Enthalpy-porosity method

When the thermophysical properties (e.g., density, thermal conductivity) of the solid phase (solid matrix) and the gel phase (quasi-liquid transition state) differ only slightly across the solid–gel interface, a coexistence region forms in which the phase transition occurs gradually, exhibiting a smooth transition behavior. To accurately describe this process, an appropriate model is required. Building on the classical binary mixture model for solid–liquid mushy zones proposed by Bennon et al.26, the solid–gel coexistence region is represented as a porous medium–like system. In this framework, the gel phase is treated analogously to pores, while phase-change units are used to simulate the porous structure. The progress of the phase transition is quantitatively characterized by the gel phase volume fraction (porosity), which provides an effective means of capturing the gradual transition behavior within the solid–gel coexistence zone.

In the equation,,\(c_{m}\),\(k_{m}\) and \(\mu_{m}\) denote the density, specific heat capacity, thermal conductivity, and dynamic viscosity of the materials in the coexistence zone, respectively;\(\rho_{s}\),\(c_{s}\),\({\text{k}}_{{\text{s}}}\) and \(\mu_{s}\) represent the density, specific heat capacity, thermal conductivity, and dynamic viscosity of the solid-phase material; while \({\uprho }_{{\text{l}}}\), \(c_{l}\),\({\text{k}}_{{\text{l}}}\), and \(\mu_{l}\) correspond to the density, specific heat capacity, thermal conductivity, and dynamic viscosity of the gel-phase material.

The volume fraction of the gel phase \({\text{g}}_{{\text{l}}}\) exhibits a piecewise linear transition behavior with temperature. The temperature dependence of the solid-gel phase transition can be expressed as:

In the equation, \(T\) represents the current temperature, while \({\text{T}}_{{\text{s}}}\) and \({\text{T}}_{{\text{l}}}\) denote the solidus and gelation temperatures of the material, respectively.

In the solid–gel coexistence zone, the evolution of a phase transition unit can be described as a process from “solid-phase velocity decay → loss of porosity (complete solidification)”. Within a solidifying unit, the solid-phase velocity gradually decreases to zero, corresponding to the disappearance of porosity. This momentum dissipation is primarily governed by Darcy friction. Based on the source term in the momentum equation, the momentum dissipation can be modeled using the Carman–Kozeny equation, which characterizes the behavior of the porous medium as follows:

In the equation, \(ug\) corresponds to the gelation velocity of the material, and \(K_{C}\) denotes the Darcy resistance coefficient27, which is formulated as a function of the gel phase volume fraction:

In the equation, \({\text{g}}_{{\text{l}}}\) denotes the gel–phase volume fraction, where \({\text{g}}_{{\text{l}}}\) = 1 corresponds to a pure gel phase with zero flow resistance, and \({\text{g}}_{{\text{l}}}\) = 0 represents a pure solid phase with maximum resistance. The constants A and B are empirical parameters associated with the characteristics of the phase coexistence region. The value of A primarily depends on factors such as the type of phase transition, the intensity of convection, and the specific operating conditions. In generally, A ranges from 103 to 101528. For typical metallic metals, an A value between 104 to 108 is considered appropriate when simulating molten pool flow behavior. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), as a non-isothermal phase-change material, exhibits a broad mushy zone, high viscosity, weak convection, and low thermal conductivity29. To satisfy the corresponding sink threshold, the value of A is typically 2–4 orders of magnitude higher than that used for metals30. However an excessively large A may induce numerical instability; therefore, a moderate value of 5 × 1010 is adopted in this study. To avoid singularities caused by a zero denominator, the constant B is defined as a small positive constant of 10⁻5 in this study31.

The solid-gel phase transition (gelation or solidification) involves absorption or release of latent heat, which must be incorporated into the energy conservation equation. To account for the effect of latent heat on the temperature field, the equivalent heat capacity method32 is employed. The equivalent heat capacity \(C_{p}\) is defined as:

In the equation, \(L_{hm}\) represents the latent heat absorbed or released during the solid-gel phase transition,\({\text{T}}_{{\text{m}}} = \frac{{{\text{T}}_{{\text{s}}} + {\text{T}}_{{\text{l}}} }}{2}\) denotes the phase transition temperature line (mean phase change temperature), and \({\Delta }T_{m}\) indicates the temperature range over which the gelation or solidification occurs.

The conservation of mass, momentum, and energy can be uniformly expressed for all three phase regions as follows:

Mass Conservation:

Momentum Conservation:

Energy Conservation:

In the equation, \({\text{u}}\) corresponds to the velocity vector, \({\uprho }\) to the density, \(C_{p}\) to the specific heat capacity,\({\upmu }\) to the dynamic viscosity, P to the pressure, I to the identity tensor, \(\beta\) to the thermal expansion coefficient, \({\text{g}}\) to the gravitational acceleration vector, and \({\text{k}}\) to the thermal conductivity.

Level set method

During laser processing, once the kerf begins to form, the gaseous products generated by pyrolysis interact with the gel phase, giving rise to a gas–gel interface. At this interface, the gel transitions directly into the gaseous state, accompanied by abrupt variations in thermophysical properties, steep temperature gradients, and significant velocity discontinuities. Surface tension, Marangoni forces, and recoil pressure are prone to sudden fluctuations, while mass transfer due to phase change also occurs across the interface.

The Level Set method is employed to track this moving interface. By incorporating appropriate source terms into the governing equations, the method effectively accounts for velocity discontinuities, abrupt force variations, and mass transfer at the interface.

Within the computational domain, an implicit scalar function φ is defined to capture the motion of the gas–gel interface. The gas region is assigned φ = 1, while the gel phase, solid phase, and solid–gel coexistence region are assigned φ = 0, The gas–gel interface is represented by φ = 0.5, The evolution of the interface is governed by the following convection–diffusion transport equation:33

In the equation, \(u_{c}\) denotes the velocity of the kerf interface, \(\gamma\) represents the initial value of the level set function, and \(\varepsilon\) indicates the thickness of the boundary layer.

The interface normal vector \(n\) and curvature K can be defined in term of the Level Set function φ as follows:

The computational domain includes the gas, gel, and solid phases. To ensure that the governing equations are valid throughout the entire domain, the material properties are smoothly interpolated in both space and time using the Level Set function \(\phi\), which can be expressed as:

When accounting for phase changes such as vaporization, the constant-pressure specific heat capacity \(C_{p}\) must be adjusted to include the effect of latent heat of vaporization:

In the equation, \({\Delta }T_{v}\) denotes the temperature range over which vaporization occurs. When the surface temperature of the material exceeds a critical threshold, vaporization takes at the interface. The abrupt transition from the gel to the gas phase leads induces a velocity discontinuity and mass transfer. Let \(u_{l}\) represent the velocity of the gel, \(u_{v}\) the velocity of the gas, and \(u_{int}\) the velocity of the gel-gas interface. These three velocities are distinct and satisfy the following relationship:34

In the equation, \(\alpha\) is a constant and \(m\) represents the pyrolysis rate35, which can be expressed respectively as follows:

In the equation, \(\beta\) is the condensation coefficient, \(M\) denotes the molecular mass of the material,\(k_{b}\) represents the Boltzmann constant, \(P_{0}\) is the standard atmospheric pressure, and \(\rho_{v}\)、 \(\rho_{l}\) indicate the densities of the material in the gaseous and gel states, respectively.

To restrict vaporization exclusively to the gel-gas interface, a Dirac delta function36, \(\delta \left( \phi \right)\) is introduced:

By simultaneously solving Eqs. (23), (25), and (27), the velocity gradient at the interface is obtained as follows:

To account for the deformation of the phase interface induced by evaporation, the level-set function needs to be modified by incorporating an evaporation-induced velocity term37. Accordingly, the governing equation is modified as follows:

Gel-gas interfacial forces

Following laser-induced vaporization, a gel-gas interface is established between the gel and gaseous phases. This interface is subjected to multiple physicochemical forces, including recoil pressure, surface tension, and Marangoni forces, all of which must be incorporated into the momentum conservation equation through appropriate mathematical modeling.

Recoil Pressure: The gaseous phase is modeled as an ideal gas, obeying the ideal gas law:

In the equation, \(P\) denotes the pressure and \(R\) represents the universal gas constant.

During intense material vaporization, recoil pressure is generated at the gel-gas interface, leading to interface depression, bending, and ultimately kerf formation. The magnitude of the recoil pressure is characterized using a saturated vapor pressure model38, it can be expressed as follows:

By employing the Dirac delta function \(\delta \left( \phi \right)\), the recoil pressure can be transformed into a volumetric force term and incorporated as a source term in the momentum equation, which can be expressed as follows:

Surface Tension: Surface tension arises from the imbalance of intermolecular forces within the thin surface layer of the gel phase. Assuming that its magnitude varies linearly with temperature39, it can be expressed as follows:

In the equation, \(\sigma_{m}\) represents the surface tension at the reference temperature, and A denotes the temperature coefficient.

Introducing the Continuum Surface Force (CSF) model proposed by J.U. Brackbill40, the surface tension is incorporated into the momentum equation as a source term by relating the pressure difference to the interface curvature. According to the Laplace law, the pressure difference across the interface between two media can be expressed as follows:

In the equation, \(p_{l}\) and \(p_{v}\) denote the pressures on the gel and gas sides of the interface, respectively; \(R_{1}\) and \(R_{2}\) represent the principal radii of curvature; and \(\sigma\) is the surface tension coefficient.

The surface curvature \(K\) is modified to \(K = R_{1}^{ - 1} + R_{2}^{ - 1}\), which is computed from the local gradient along the surface normal direction.

By employing the Dirac delta function \(\delta \left( \phi \right)\), the surface tension is transformed into a volumetric force and incorporated as a source term in the momentum equation:

Marangoni Force: A gradient in surface tension coefficient induced by temperature variation gives rise to the Marangoni force, which can be expressed as:

By employing the Dirac delta function \(\delta \left( \phi \right)\), the Marangoni force is transformed into a volumetric force and incorporated as a source term in the momentum equation:

By accounting for the effects of recoil pressure, surface tension, and the Marangoni force, the momentum conservation equation is modified as follows:

Heat source model

In the laser wire stripping process, a Gaussian heat source is employed to represent the spatial distribution of laser energy, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

The spatial energy distribution of the Gaussian heat source follows a Gaussian profile, which can be expressed as follows:

In the equation, \(\alpha\) represents the material’s absorptivity to the laser, \(p_{0}\) denotes the laser power, The laser beam radius \(r\) at a defocusing distance \(z\) is expressed as \({\text{r}} = r_{0} \sqrt {1 + \left( {\frac{z}{{z_{R} }}} \right)^{2} }\), where \(r_{0}\) is the focal spot radius. The Rayleigh length \(z_{R}\) is defined as \(z_{R} = \frac{{\pi r_{0}^{2} }}{{\lambda M^{2} }}\), where \(M^{2}\) is the beam product parameter, characterizing the beam quality and indicating the deviation of the actual beam from an ideal Gaussian beam. The parameter \(\lambda\) denotes the laser wavelength, and z is the defocusing distance.

During the thermophysical process involving multiphase transitions, heat loss occurs exclusively at the gas-gel interface. By incorporating the Dirac delta function \(\delta \left( \phi \right)\) from the Level Set method, the heat source is confined to the vicinity of the gas-gel interface. The modified heat source model can be expressed as follows:

To simulate the temporal profile of the laser irradiation, a piecewise function is defined as follows:

In the equation,\(t{\text{x}}\) represents the time at which the laser irradiates a specific point on the cross-section, \(t_{{{\text{total}}}}\) denotes the total processing time, and \(t_{{{\text{total}}}}\) is the repetition period.

During laser irradiation, the material undergoes pyrolysis, generating gaseous products. Oscillations at the gel–gas interface result in heat losses via vaporization, convection, and radiation. To account for these effects, the energy conservation equation must be modified. The heat loss term is expressed as follows:

In the equation, \(m\) represents the vaporization mass flux, \(L_{v}\) denotes the latent heat of vaporization,\(h_{c}\) is the convective heat transfer coefficient,\(\varepsilon_{b}\) is the surface emissivity of the material, \(\sigma_{s}\) is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant, and \(T_{s}\) is the ambient temperature. The modified energy conservation equation is expressed as follows:

Thermo-viscoelastic model

PTFE undergoes direct pyrolysis without boiling upon absorbing laser energy. Furthermore, according to the findings of P. N. Grakovich et al., the surface layer of PTFE forms a high-viscosity melt under laser irradiation, where viscous flow dominates the deformation behavior, and no deformation or failure induced by shear stress has been observed41. Therefore, the following assumptions are made in this study:

-

1)

The material is regarded as continuous and isotropic. A simplified two-dimensional model is employed, and the shear modulus is neglected.

-

2)

Material properties vary piecewise with temperature.

-

3)

The influence of stress variations on the temperature field is neglected.

-

4)

The gaseous products generated from pyrolysis are assumed to be stress-free.

-

5)

The material transitions directly to the gaseous state once the pyrolysis temperature is reached.

Since Hooke’s law is not applicable to PTFE, the Kelvin viscoelastic model is introduced. The displacement components are defined as u (x, y, t) in the x-direction and v (x, y, t) in the y-direction.

The thermal strain is defined as:

The relation between displacement and thermal strain is expressed as:

The stress–strain relationship is expressed as:

Relaxation time:

In the equation, \(\eta \left( T \right)\) denotes the temperature-dependent viscosity, and \(E\left( T \right)\) represents the temperature-dependent Young’s modulus.

To account for the abrupt changes in material properties before and after pyrolysis, temperature-dependent parameters are defined using piecewise functions:

Coefficient of thermal expansion:

Young’s modulus:

Viscosity:

Initial conditions, boundary conditions and physical properties

The initial conditions of the model are set as follows:

The boundary conditions of the model are set as follows:

The left, right, and bottom boundaries of the material are subject to:

The left and right boundaries are defined as outlets for the gaseous phase:

Convective and radiative heat losses occur on the upper surface of the target material:

The specific initial and boundary conditions are illustrated in Fig. 4.

In previous similar thermal simulation studies, it has been a common practice to assume that the thermophysical properties of materials are independent of temperature. This assumption not only significantly enhances numerical stability and computational efficiency but also exerts no notable adverse effect on the accuracy of the results42,43. Therefore, this assumption is adopted in this study. The material properties are shown in Table 1.

Analysis of simulation results

A study conducted by Changchun University of Science and Technology demonstrated that processing parameters such as laser power, scanning speed, and the processing time significantly affect the removal quality during practical laser wire stripping44. Furthermore, the research indicated that polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) exhibits high absorption at a 405 nm laser wavelength45, whereas the metallic core of aerospace power cables shows high reflectivity at the same wavelength. This contrast in optical properties provides a fundamental basis for the precise control of insulation removal.

Building upon these findings, the present study employs a 405 nm semiconductor laser as the processing light source and focuses on examining the effects of key parameters—laser power, scanning speed, and the number of scans—on the stripping quality of PTFE insulation. Based on the existing research, it is observed that when PTFE is heated above 473K (200 °C), regardless of whether it is in a crystalline or quenched state, its heat capacity–temperature curve exhibits a pronounced upward deviation, a phenomenon attributed to “pre-melting.” In this temperature regime, the amplitude of molecular chain vibration and rotation increases, the internal crystalline structure becomes loosened, and the surface morphology undergoes noticeable changes due to intensified molecular motion46. To quantitatively evaluate the thermal effects and geometric characteristics during the laser removal process, based on the thermophysical properties of PTFE, characteristic temperature intervals are defined as follows: the region where the insulation temperature ranges from 473 to 688 K is designated as the heat-affected zone (HAZ), within which the material experiences thermal influence without undergoing pyrolysis; temperatures exceeding 688 K correspond to the material removal zone, where PTFE primarily undergoes pyrolysis and vaporization47.

Using a numerical temperature field model, characteristic parameters such as the initial HAZ extent, kerf width, and kerf depth can be extracted. Considering the thermal expansion induced by thermal stresses under laser irradiation, the actual geometric parameters of the kerf (width and depth) after stripping are further quantified using the volume fraction method. Finally, by comparing kerf characteristics predicted by the temperature field model with the actual parameters measured via the volume fraction method, the influence of thermal expansion on removal morphology is quantitatively assessed.

Simulation analysis of processing parameters based on the single-factor method

Laser power

Laser power is a critical factor affecting the outcome of the laser wire stripping process. In this simulation, based on prior practical experience, the laser scanning speed was fixed at 3 r/s and the processing time at 10 s. Laser power values of 0.6 W, 0.7 W, 0.8 W, 0.9 W, and 1.0 W were investigated. The resulting temperature fields, volume fractions, and stress fields under different power conditions are illustrated Figs. 5a–e, 6a–e, and 7a–e, respectively. Corresponding data on the heat-affected zone (HAZ), kerf width, kerf depth, and thermal expansion displacement are presented in Fig. 8, The stress value data are shown in Fig. 9.

As shown in Figs. 8 and 9, all five metrics—HAZ, cutting width, cutting depth, thermal expansion displacement, and stress—exhibit a monotonic increase with increasing laser power.

It is noteworthy that, due to the low elastic modulus and high toughness of PTFE, even under elevated local von Mises stress, the material mainly shows increased thermal expansion and slight localized warping rather than brittle cracking. Therefore, laser power should be selected to balance cutting efficiency with controlled thermal stress and minimal cut deformation, ensuring both processing quality and efficiency.

Scanning speed

Based on the preceding analysis of laser power, the laser power was fixed at 0.8 W with a processing time of 10 s, while the scanning speed was varied at 1 r/s, 2 r/s, 3 r/s, 4 r/s, and 5 r/s. The resulting temperature fields, volume fractions, and stress fields for each scanning speed are illustrated in Figs. 10a–e, 11a–e, and 12a–e, respectively. Corresponding data on the heat-affected zone (HAZ), kerf width, kerf depth, and thermal expansion displacement are summarized in Fig. 13, The stress value data are shown in Fig. 14.

As shown in Figs. 13 and 14, both the kerf width, thermal expansion displacement, and maximum von Mises stress all decrease with increasing scanning speed, indicating reduced thermal stress accumulation at higher speeds.

Processing time

The processing time was varied at 4 s, 6 s, 8 s, 10 s, and 12 s. The resulting temperature fields, volume fractions, and stress fields under each processing time condition are illustrated in Figs. 15a–e, 16a–e and 17a–e, respectively. Corresponding data on the heat-affected zone (HAZ), kerf width, kerf depth, and thermal expansion displacement are presented in Fig. 18, The stress value data are shown in Fig. 19.

As shown in Figs. 18 and 19, at shorter processing times (4 s, 6 s, and 8 s), the adiabatic layer remains only partially ablated. Meanwhile, both the heat-affected zone (HAZ) and the maximum von Mises equivalent stress increase gradually with processing time. Nevertheless, compared with the pronounced stress variations caused by changes in laser power, this increase is relatively moderate.

Orthogonal experimental design

Based on the single-factor finite element simulations conducted for each processing parameter, it was observed that laser power and scanning speed exert significant influence on the kerf width and heat-affected zone (HAZ) width of the insulation layer. Rational selection of these parameters can simultaneously ensure both stripping quality and processing efficiency.

Accordingly, in the orthogonal experimental design for laser stripping of PTFE insulation on aviation cables, three levels were selected for each parameter according to their influence on stripping quality and efficiency: Laser power: 0.7 W, 0.8 W, 0.9 W, Scanning speed: 2 r/s, 3 r/s, 4 r/s, Processing time: 8 s, 10 s, 12 s. This constitutes a three-factor, three-level experimental setup, arranged using an L9(34) orthogonal array to define nine distinct parameter combinations for testing.

The experiment employed an AWG-8 cable supplied by Chengfei Company, selected primarily based on two key considerations.

-

1)

This cable specification represents one of the most widely used large-diameter types in aerospace wiring harness assembly operations. Its conductor diameter and current-carrying capacity precisely align with the technical requirements of aircraft wiring integration, ensuring that the experimental results closely reflect real-world aerospace electrical installation conditions. This alignment enhances the engineering relevance and practical applicability of the research findings.

-

2)

The cable’s insulation material is explicitly identified as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). This material exhibits exceptional thermal stability and reliable electrical insulation performance, effectively eliminating potential experimental variability arising from uncertain insulation properties. Consequently, it provides a consistent and controllable material baseline for subsequent testing stages, including evaluations of electrical and environmental performance.

The Table 2 presents the parameters of the test cable.

Upon completion of the experiments, the kerf morphology of the insulation layer for each group was examined under a microscope. Using the dimension measurement module of the dedicated image acquisition software Galaxy paired with an industrial camera, precise measurements of kerf width, kerf depth, HAZ width, and thermal expansion displacement of the PTFE insulation were obtained for each parameter set.

The laser wire-stripping effects under different parameter combinations for Groups 1–4 are shown in Fig. 20, and those for Groups 5–9 are shown in Fig. 21. During microscopic measurements, kerf-depth data were acquired at the cable edge, as shown in Figs. 20 and 21. When the insulation is fully penetrated, the inner conductor becomes exposed. In Figs 20 and 21, W represents the kerf width, L denotes the width of the heat-affected zone, and D indicates the kerf depth. The measurement results are presented in Table 3.

0presents the results of the three-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the experimental data. The sum of squares (SS) quantifies the contribution of each factor to the total variation observed in the response variable. The degrees of freedom (df) provide the basis for variance estimation. The F-value denotes the ratio of the variance associated with each factor to the residual variance, where a higher F-value indicates a stronger influence of that factor on the response variable. The p-value is employed to assess statistical significance, thereby reflecting the reliability of the results. The partial eta squared (Partial η2) quantifies the proportion of total variance in the response variable explained by each factor, offering a measure of their relative explanatory power.

0presents the influence weights of the evaluation indices for each factor, calculated using the normalized sum of squares (SS) method derived from the ANOVA results.

Comprehensive analysis integrating the single-factor simulation results and the orthogonal experimental findings indicates that the kerf morphology during laser stripping of PTFE insulation is governed by a thermo-mechanical coupling mechanism influenced by laser power, scanning speed, and processing time. Laser power acts as the most sensitive primary effect factor; its increase enhances the energy flux density and transient temperature rise, extends the thermal diffusion length, and steepens the temperature gradient. These effects collectively generate peak von Mises equivalent stresses along the kerf edges and within the heat-affected zone (HAZ), inducing localized warping and geometric deviation due to constrained thermal expansion. In contrast, increasing the scanning speed shortens the dwell time, thereby reducing energy accumulation and peak temperature. This leads to an overall decrease in stress and thermal displacement, improving edge regularity. However, excessively high scanning speeds result in insufficient energy per pulse, hindering full penetration and limiting kerf depth development. The processing time reflects temporal energy accumulation effects, contributing to kerf depth with a significance lower than that of power but higher than that of speed; after full penetration is achieved, its incremental influence on morphology and stress becomes progressively weaker.

These results demonstrate that the combined characteristics of kerf width, depth, and HAZ morphology are directly governed by the distribution of thermally induced strain and the topology of von Mises stress driven by temperature gradients. Therefore, parameter optimization should not focus solely on increasing laser power. Instead, it should be conducted within a synergistic framework of power–speed–time coordination, where penetration and dimensional accuracy serve as constraints. By controlling excessive stress and HAZ expansion induced by high power, while appropriately increasing scanning speed and moderately extending processing time, a comprehensive optimization can be achieved that balances efficiency, stress control, and morphological stability.

Based on the above analysis, the influence of each processing parameter on kerf quality can be intuitively interpreted as follows:

-

1)

Kerf width: Laser power > Scanning speed > Processing time

-

2)

Kerf depth: Laser power > Processing time > Scanning speed

-

3)

Heat-affected zone (HAZ) width: Laser power > Scanning speed > Processing time

-

4)

Thermal expansion displacement: Laser power > Scanning speed > Processing time

To determine the optimal processing parameters for the 8 AWG cable, this study conducted a multi-objective optimization analysis based on experimental data. According to the specifications of the 8 AWG cable, a cutting depth of 500 µm was established as the qualification threshold, while the evaluation was carried out within the constraint limits specified by the SAE AS6894 standard. The following processing criteria were defined:

-

1)

The kerf depth shall be no less than 500 µm;

-

2)

The kerf width shall be no greater than 150 µm;

-

3)

The width of the heat-affected zone (HAZ) shall be no greater than 150 µm;

-

4)

The thermal expansion displacement shall not exceed 50 µm.

A multi-criteria evaluation system was established using the satisfaction analysis method, in which binary satisfaction functions were defined for each processing indicator.

The data from 0are substituted into Formulas (56), (57), (58), and (59), resulting in a total of five groups with a score of 4, specifically the 4th, 5th, 7th, 8th, and 9th groups.

In the five groups that meet the criteria, to obtain the optimal cutting efficiency parameters, this study quantifies the cutting efficiency by analyzing time efficiency in terms of laser energy utilization efficiency and effective volume removal rate. The analysis is conducted using the following formulas:

In the equations, \(\eta_{E}\) represents the laser energy utilization efficiency, \(\eta_{t}\) denotes the time efficiency,\(W_{K} ,D_{K} ,C_{l} ,P_{L} ,t_{l}\) represent the groove width, groove depth, cable outer diameter circumference, laser power, and processing time, respectively.

Substituting the five sets of qualified parameters into Formula (60) yields the results shown in 0.

Based on a comprehensive evaluation of time and energy efficiency, Group 8—laser power 0.9 W, scan rate 3 r·s⁻1, and processing time 8 s—was determined to be the optimal process configuration for laser stripping of AWG 8 aviation cables.

It should be noted that, in the present numerical simulations, the stress generated by gases produced during pyrolysis of the polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) insulation layer—and the associated normal pressure imposed on the target surface—has not yet been considered. In future work, we propose to extend the current thermo–mechanical coupling model by introducing a transient pressure field of pyrolysis/vaporization products within the kerf porosity and coupling this field with the solid-mechanics analysis in a multiphysics framework. Such an enhancement would enable a more accurate description of material flow in the kerf region and of the formation mechanism of the recondensed layer. This, in turn, would help elucidate how the expansion of pyrolysis gases governs the redeposition behavior of locally molten material, thereby offering more actionable guidance for optimizing laser stripping parameters and for practical manufacturing. (Tables 4, 5 and 6)

Quantitative comparative analysis of key simulation and experimental results

In both the single-factor simulation analysis and the orthogonal experimental design, three parameter combinations share identical conditions, specifically: laser power of 0.7 W, scanning speed of 3 r/s, and processing time of 10 s (as shown in Fig. 22); laser power of 0.8 W, scanning speed of 2 r/s, and processing time of 10 s (as shown in Fig. 23); and laser power of 0.8 W, scanning speed of 3 r/s, and processing time of 12 s (as shown in Fig. 24) Table 7 presents a comparison between the simulated and experimental data under identical parameter conditions.

Through quantitative comparison and range analysis, certain discrepancies were identified, primarily manifested as higher simulated values. The possible reason for this deviation lies in the experimental processing, where it is difficult to maintain constant ambient temperature and airflow. Nevertheless, the overall trends of the relative influence of each factor on the kerf characteristics remain consistent. This consistency further validates the accuracy of the established laser insulation layer stripping model and confirms the reliability of the orthogonal experimental results.

Conclusion

This study combined thermomechanical coupled finite element simulations and orthogonal experiments to optimize laser stripping parameters for PTFE insulation on large-diameter aerospace cables. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

1)

A thermo-mechanical coupling finite element model was developed on the COMSOL platform for laser stripping of PTFE insulation on large-diameter aerospace cables. By incorporating the enthalpy-porosity method and the level set method, the precise tracking of solid-to-gel and gel-to-gas interface evolution was achieved. Coupled with a Gaussian heat source model and a thermoviscoelastic constitutive equation, this model effectively describes the laser energy transfer, material phase change, and mechanical response processes. It provides a reliable numerical simulation tool for subsequent parameter analysis and optimization.

-

2)

The single-factor simulation analysis clarified the impact of key processing parameters on the stripping quality. Increasing the laser power significantly improves the stripping efficiency, but it also results in a wider cut seam, an expanded heat-affected zone, and increased thermal displacement. Increasing the scanning speed effectively reduces the cut seam width, but may lower processing efficiency due to insufficient energy input. A moderate increase in processing time can enhance the cutting depth; however, beyond a certain threshold, its effect on the stripping morphology and stress becomes less pronounced. These findings provide clear guidance for the optimization of parameter combinations.

-

3)

A three-factor, three-level orthogonal experiment was conducted using 8 AWG PTFE-insulated aerospace cables as the research object. The comprehensive analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that laser power plays a dominant role in the cut seam depth, cut seam width, heat-affected zone width, and thermal displacement. It is identified as the core parameter for controlling stripping quality.

-

4)

Through multi-objective optimization and energy efficiency analysis, it was determined that the optimal laser stripping parameters for the 8 AWG PTFE-insulated aerospace cable are a laser power of 0.9 W, scanning speed of 3 r/s, and processing time of 8 s. This parameter combination ensures efficient stripping while maintaining high processing quality.

-

5)

A quantitative comparison was made between the simulation and experimental results under three sets of identical parameter conditions. The consistency between the two was found to be good in key indicators such as cut seam morphology, heat-affected zone extent, and thermal displacement, validating the accuracy of the developed thermo-mechanical coupling model. The research findings provide both theoretical foundation and practical engineering reference for high-quality and high-efficiency laser stripping of large-diameter aerospace cable PTFE insulation.

Data availability

The datasets of related experiments and simulations involved in this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Fan, H. J. Review of cable insulation stripping technology patents. Sci. Technol. Innov. 33, 168–169. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-1328.2018.33.104 (2018).

DiNenno, P. J. SFPE handbook of fire protection engineering. 2–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2565-0 (2002).

Biswas, S., Pramanik, D., Roy, N., Biswas, R. & Kuar, A. S. An experimental investigation of micro-channels on transparent material using Nd: YAG laser transmission technique. Opt. Laser Technol. 175, 110671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2024.110671 (2024).

Park, J. W., Oh, S. C., Lee, H. P., Kim, H. T. & Yoo, K. O. Kinetic analysis of thermal decomposition of polymer using a dynamic model. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 17(5), 489–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02707154 (2000).

Li, M., Gan, G., Zhang, Y. & Yang, X. Thermal damage of CFRP laminate in fiber laser cutting process and its impact on the mechanical behavior and strain distribution. Arch. Civil Mech. Eng. 19(4), 1511–1522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acme.2019.08.005 (2019).

SAE International. Laser wire stripping tools, general understanding, SAE paper AIR6894, 9–11, https://doi.org/10.4271/air6894. (2016).

Brannon, J. H., Tam, A. C. & Kurth, R. H. Pulsed laser stripping of polyurethane-coated wires: A comparison of KrF and CO2 lasers. J. Appl. Phys. 70(7), 3881–3886. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.349195 (1991).

Brannon, J. & Snyder, C. Pulsed 532 nm laser wire stripping: Removal of dye-doped polyurethane insulation. Appl. Phys. A 59(1), 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00348423 (1994).

Barnier, F., Dyer, P. E., Monk, P., Snelling, H. V. & Rourke, H. Fibre optic jacket removal by pulsed laser ablation. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 33(7), 757. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/33/7/301 (2000).

Guerrero-Vaca, G. et al. Stripping of PFA fluoropolymer coatings using a Nd: YAG laser (Q-Switch) and an Yb fiber laser (CW). Polymers 11(11), 1738. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11111738 (2019).

Lee, J. R., Dhital, D. & Yoon, D. J. Investigation of cladding and coating stripping methods for specialty optical fibers. Opt Lasers Eng. 49, 324–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlaseng.2010.10.008 (2010).

Martyniuk, J. UV laser-assisted wire stripping and micro-machining. Lasers Tools Manuf. 2062, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.167593 (1994).

Iceland, W. F. Design and development of equipment for laser wire stripping. Ind. Appl. High Power Laser Technol. 86, 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.954963 (1976).

Wang, J., & Liu, X. The application of hand-held laser wire stripper in the field of aerospace. In International Symposium on Optoelectronic Technology and Application 2014: Laser Materials Processing; and Micro/Nano Technologies, 9295, 194–197. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2073339. (2014).

Liu, W. B., Yang, G. L., & Wang, M. D. Design and process parameters research of single-laser stripping platform based on automatic double-position flipping mechanism. In 3rd Annual International Conference on Mechanics and Mechanical Engineering ,291–297. Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/mme-16.2017.40. (2016).

Lizotte, T. E., Dagher, J. & Ohar, O. Laser beam shaping for UV laser-based micromachining of micro-gauge dielectric coated wire. Laser Beam Shap. XVIII 10744, 186–195. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2323001 (2018).

Peng, R. X., Zhou, C. M. & Zhu, H. H. Experimental research on removing optical fiber coatings using a TEA CO2 laser. Laser Technol. 29, 670–672. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-3806.2005.06.034 (2005).

Lee, J. R., Dhital, D. & Yoon, D. J. Investigation of cladding and coating stripping methods for specialty optical fibers. Opt. Lasers Eng. 49(3), 324–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlaseng.2010.10.008 (2011).

Marimuthu, S., Kamara, A. M., Sezer, H. K., Li, L. & Ng, G. K. L. Numerical investigation on laser stripping of thermal barrier coating. Computational Mater. Sci. 88, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2014.02.022 (2014).

Yang, G. L. et al. Process optimization study of laser-controlled stripping of fine wires [in Chinese]. Applied Laser 36(01), 84–89. https://doi.org/10.14128/j.cnki.al.20163601.084S (2016).

Tang, H. Study on stripping process of polyimide wires [in Chinese]. Mech. Elect. Components 39(01), 33–35. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6133.2019.01.008 (2019).

Zhang, Q. et al. Study on laser stripping process of polyimide-insulated wires [in Chinese]. Elect. Process Technol. 40(02), 116–119. https://doi.org/10.14176/j.issn.1001-3474.2019.02.015 (2019).

Li, P. et al. Study on process parameters of low-power semiconductor laser stripping PTFE insulating layer of aviation wire. J Phys.: Conf. Series 2395, 012025. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2395/1/012025 (2022).

Zhang, D. X., Zhang, R., He, Z., Wu, J. J. & Zhang, F. Numerical investigation on laser ablation characteristics of PTFE in advanced propulsion systems. Appl. Mech. Mater. 229(727–731), 2012. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.229-231.727 (2012).

Bennon, W. D. & Incropera, F. P. A continuum model for momentum heat and species transport in binary solid-liquid phase change systems—I Model formulation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 30(10), 2161–2170. https://doi.org/10.1016/0017-9310(87)90094-9 (1987).

Voller, V. R. & Prakash, C. A fixed grid numerical modelling methodology for convection-diffusion mushy region phase-change problems. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 30(8), 1709–1719. https://doi.org/10.1016/0017-9310(87)90317-6 (1987).

Zhou, J., Tsai, H. L. & Lehnhoff, T. F. Investigation of transport phenomena and defect formation in pulsed laser keyhole welding of zinc-coated steels[J]. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 18(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/39/24/036 (2006).

Ebrahimi, A., Kleijn, C. R. & Richardson, I. M. Sensitivity of numerical predictions to the permeability coefficient in simulations of melting and solidification using the enthalpy-porosity method. Energies 12(22), 4360. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12224360 (2019).

Lau, S. F., Suzuki, H. & Wunderlich, B. The thermodynamic properties of polytetrafluoroethylene. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Phys. Ed. 22(3), 379–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.1984.180220305 (1984).

Rocha, T. T. M., Trevizoli, P. V. & de Oliveira, R. N. The role of the phase-change material properties, porosity constant, and their combination for melting problems using the enthalpy-porosity scheme. Thermal Sci. Eng. Progress 46, 102198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsep.2023.102198 (2023).

Chen, D. Numerical simulation of high energy density welding pool behavior based on the Level-Set method [Master’s thesis, Chongqing University of Technology]. [in Chinese]. 23–24. https://doi.org/10.27753/d.cnki.gcqgx.2023.001933. (2023).

Zhou, J., Tsai, H. L. & Lehnhoff, T. F. Investigation of transport phenomena and defect formation in pulsed laser keyhole welding of zinc-coated steels. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 39(24), 5338. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/39/24/036 (2006).

Shi, R. Simulation study on the dynamic formation processes of keyhole and molten pool based on the Level-Set method [Master’s thesis, Hunan University]. [in Chinese]. 20–24. https://doi.org/10.7666/d.Y2356289. (2013).

Son, G. & Dhir, V. K. A level set method for analysis of film boiling on an immersed solid surface. Numer. Heat Transf., Part B: Fundamentals 52(2), 153–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/10407790701347720 (2007).

Oliveira, V. & Vilar, R. Finite element simulation of pulsed laser ablation of titanium carbide. Appl. Surf. Sci. 253(19), 7810–7814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2007.02.101 (2007).

Ye, H. Simulation and experimental study on laser machining of dense micro-hole arrays in large-scale stainless steel plates. [Master’s thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology]. [in Chinese]. 15–16. https://doi.org/10.27061/d.cnki.ghgdu.2019.003464. (2019).

Sun, Y. & Beckermann, C. Diffuse interface modeling of two-phase flows based on averaging: mass and momentum equations. Phys. D: Nonlinear Phen. 198(3–4), 281–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physd.2004.09.003 (2004).

Sharma, S., Mandal, V., Ramakrishna, S. A. & Ramkumar, J. Numerical simulation of melt hydrodynamics induced hole blockage in Quasi-CW fiber laser micro-drilling of TiAl6V4. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 262, 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2018.06.038 (2018).

Du, H., Hu, L., Liu, J. & Hu, X. A study on the metal flow in full penetration laser beam welding for titanium alloy. Comput. Mater. Sci. 29(4), 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2003.11.002 (2004).

Brackbill, J. U., Kothe, D. B. & Zemach, C. A continuum method for modeling surface tension. J. Comput. Phys. 100(2), 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9991(92)90240-Y (1992).

Grakovich, P. N. et al. Laser ablation of polytetrafluoroethylene. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 79(3), 626–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2018.06.038 (2009).

Kaplan, A. A model of deep penetration laser welding based on calculation of the keyhole profile. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 27(9), 1994. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/27/9/002 (1805).

Semak, V. & Matsunawa, A. The role of recoil pressure in energy balance during laser materials processing. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 30(18), 2541. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/30/18/008 (1997).

Li, P. et al. Study on the optimal process parameters for stripping the X-ETFE insulation layer of aviation wires by a small semiconductor laser. Adv. Mech. Eng. 14(9), 16878132221127592. https://doi.org/10.1177/16878132221127592 (2022).

Zhou, P. M. Research on laser processing technology of aviation harness terminals [Master’s thesis, Changchun University of Science and Technology] [in Chinese]. 16–19. https://doi.org/10.26977/d.cnki.gccgc.2021.000819. (2021).

Douglas, T. B. & Harman, A. W. Relative enthalpy of polytetrafluoroethylene from 0 to 440 C. J. Res. National Bureau Standards Sect. A Phys. Chem. 69(2), 149. https://doi.org/10.6028/jres.069a.017 (1965).

Dhanumalayan, E. & Joshi, G. M. Performance properties and applications of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)—a review. Adv. Composit. Hybrid Mater. 1(2), 247–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-018-0023-8 (2018).

Funding

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to High-end Aviation Equipment Technology Innovation Center (Sichuan) Co., Ltd. and Chengdu Aircraft Industrial (Group) Co., Ltd. for their valuable process and technical guidance, and to financial support from the Science and Technology Development Program of Jilin Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.L. conducted experiments and completed the writing of the manuscript; S.W. carried out simulation analysis; P.G. 、E.T. and C.T. participated in the discussion of experimental and simulation data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, P., Wang, S., Gao, P. et al. Investigation of laser stripping process parameters for insulation layers of large diameter aviation cables based on thermodynamic coupling. Sci Rep 16, 3928 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33882-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33882-y