Abstract

Carbonation-induced degradation is one of the leading causes of durability loss in concrete structures. Despite advances in conventional concrete carbonation models, predictive models for fiber-reinforced ultra-high-performance concrete (FR-UHPC) remain scarce, given its complex, multiscale behavior. This study presents a new and data-driven analytical framework for predicting the carbonation depth of FR-UHPC using advanced machine learning techniques, including neural operators for modeling physical systems (NOMPS), artificial intelligence-based pipeline search for regression (AIPSR), quantum machine learning (QML), and explainable AI using quantum shapley values (EAIQSV). Analysis of 800 experimental data points identified curing time, temperature, and silica fume content as key determinants of carbonation depth. The models were validated through rigorous statistical analysis and 5-fold cross-validation, with AIPSR outperforming the other models in terms of prediction accuracy (R² = 0.83) and consistency. This framework provides a robust and repeatable method for predicting carbonation in FR-UHPC, while improving interpretability and incorporating quantum-inspired machine learning techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete is widely used in building construction, infrastructure, transportation, water conservancy projects, and port facilities1. Durability is one of the most critical parameters to measure to assess concrete performance. Durability is essential for protecting reinforced concrete structures from risks throughout their service life2. Numerous factors contribute to concrete’s durability. Carbonation is one of the most common forms of damage that can occur anywhere, driven by the presence of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere3.

Carbonation occurs when CO2 from the surrounding atmosphere enters the pores of concrete4. Because of this CO2 seepage, calcium carbonate (CaCO3) forms, reducing the pH to about 9 upon reaction with hydrated cement composites5. Because of its high CO2 emissions, the concrete industry is also fraught with grave environmental problems6. Carbonation zones in concrete structures can lead to corrosion of steel reinforcement, resulting in physical damage such as spalling and cracking7. Also, it results in a decline in concrete compressive strength, a reduction in the steel’s cross-sectional area, and damage to the steel-concrete bond. Thus, the reinforced concrete’s structural strength is diminished, reducing its lifespan8.

In addition, billions of dollars are spent each year to address corrosion9. Therefore, early detection and monitoring of concrete carbonation are essential to maintaining concrete’s structural health. Although there are different laboratory methods for assessing the carbonation depth of concrete, traditional approaches are expensive, take a long time to complete, highly destructive, and provide scant data on the specific contributions of individual variables that affect the rate of carbonation depth progression7,10. Thus, the ability to reliably model the progression of carbonation and make accurate predictions can greatly help mitigate enduring damages, improve safety procedures, and reduce financial impacts7. Precise estimates of concrete carbonation in reinforced structures are critical for improving their durability and safety11 and for guiding preservation actions targeted to them12.

Accurately predicting the depth of carbonation of concrete has long been a significant challenge. Given the complexity of carbonation, especially when using experimental data, machine learning models offer a promising solution13. These models are particularly effective at understanding the complex relationships among input variables, such as concrete mix composition, making them a valuable tool in this field14,15,16,17,18,19. Taffese et al.20 used artificial neural networks (ANNs) to model and predict the accelerated carbonation depth of concrete. They applied sequential feature selection to reduce irrelevant variables in the experimental dataset. Wei et al.21 evaluated the predictive ability of a back-propagation neural network (BPNN) compared with a support vector machine (SVM) for modeling the carbonation depth of concrete with mineral admixtures. Their results showed that the BPNN outperformed the SVM model. Luo et al.22 integrated particle swarm optimization (PSO) with a BPNN to predict the length of the partial carbonation zone, defined as pH values of 9–11.5.5. Akpinar and Uwanuakwa23 used ANN models to predict the carbonation depth of concrete and found that accurate predictions could be achieved with 10 hidden neurons. Ehsani et al.7 used ANNs, random forests (RFs), decision trees (DTs), and SVMs to predict the concrete carbonation depth and developed several models. Feature selection was performed using a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition, combined with an ANN (MOEA/D-ANN). Their findings showed that the ANN model achieved the highest prediction accuracy with this novel feature selection method, compared to other machine learning models.

Alongside these initiatives, Li et al.24 used SVM to predict the carbonation depth of concrete, and their results showed that SVM models outperformed BPNN by a notable margin in terms of prediction accuracy. Tran et al.25 developed a predictive model based on the RF algorithm and effectively forecasted the carbonation depth of concrete. Marani et al.26 developed a deep learning model to predict natural carbonation in low-carbon concrete. They formulated a model that not only predicts the carbonation depth but also accounts for uncertainty in its predictions using a vast dataset that includes the material properties and external environmental conditions. In addition, Uwanuakwa10 applied recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to develop a deep learning model for predicting carbonation depth in fly ash-blended concrete. The study showed that RNNs outperformed other machine learning models, such as ANNs, SVMs, and DTs, in prediction and were better at generalizing to unseen data and at capturing the complex nature of concrete carbonation. Hosseinnia et al.27 used multi-gene genetic programming (MGGP) and RF to predict the carbonation depth in concrete samples containing fly ash. They integrated the Pareto envelope-based selection algorithm II (PESA-II) with ANNs for feature selection, achieving high prediction accuracy (R² = 0.91 on the test set).

Although previous machine learning models have been able to predict the depth of carbonation in concrete, they often do not generalize to different types of concrete. Most existing models act as black boxes and are limited to predicting carbonation depth for samples similar to those in the training set. For example, models designed for conventional concrete do not account for the variations observed in reinforced concrete containing additives or additional cementitious materials. This highlights a significant gap: the need for machine learning models that can reliably predict carbonation depth across a wide range of concrete mixtures, reflecting the compositional diversity found in real-world engineering applications.

Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC) is a type of concrete known for its durability, exceptional strength, and resilience compared to conventional concrete. Due to its high importance, many studies have been conducted on the performance of UHPC28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. The importance of UHPC and its subcategories, such as fiber-reinforced ultra-high-performance concrete (FR-UHPC), is increasingly felt every day. FR-UHPC is known for its groundbreaking strength, outstanding durability, and resilience, leading to its widespread acceptance in engineering applications and revolutionizing the design and construction of high-performance structures37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. The UHPC matrix with incorporated fibers exhibits considerable improvement, particularly in mechanical properties such as tensile strength and fracture toughness, making it highly suitable for demanding civil engineering projects46,47,48. Thus, FR-UHPC is gaining popularity for use in construction projects that entail high-level infrastructure with a critical need for durability and longevity, as well as in modern benchmarks in materials science and engineering practice.

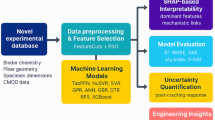

This research aims to, for the first time, apply machine learning techniques to predict the carbonation depth of FR-UHPC using a comprehensive dataset of 800 data points. The literature suggests that the problem of predicting carbonation depth has been addressed using various machine learning techniques, including ANNs, RF, SVMs, and DTs. In contrast, this paper explores the application of cutting-edge machine learning methodologies, including neural operators for modeling physical systems (NOMPS), quantum machine learning (QML), explainable AI using quantum shapley values (EAIQSV), and AI-driven Pipeline Search for Regression (AIPSR). To date, these machine learning methods have not been applied to predict the carbonation depth of concrete, especially in the context of FR-UHPC. The ability of these advanced techniques to improve the prediction accuracy and model interpretability in this area remains largely unknown. This paper presents a novel approach to predicting the carbonation depth of FR-UHPC using these state-of-the-art machine learning techniques. The study evaluates these methods not only for their predictive power but also for their ability to provide a deeper understanding of the mechanisms governing carbonation behavior. A comprehensive evaluation of all proposed models will be performed, including direct comparisons with traditional machine learning algorithms commonly used in the literature. This comparison allows us to evaluate the performance of the new methods relative to existing models in terms of accuracy, generalizability, and interpretability. Finally, this paper presents the most effective model for predicting carbonation depth in FR-UHPC, offering significant improvements in accuracy and transparency for carbonation modeling in high-performance concrete systems.

Methodology

Below is an expanded and in-depth explanation of six state-of-the-art machine learning techniques that emerged or gained significant traction in 2025. These methods can significantly enhance the predictive modeling of carbonation depth in FR-UHPC and similar materials:

Neural operators for modeling physical systems (NOMPS)

The NOMPS approach is a significant advance in numerical modeling specifically designed to address the complexity of physical systems governed by partial differential equations (PDEs). Unlike classical physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), which are optimized for fixed boundary conditions and computationally intensive computations, NOMPS (including models such as DeepONet and the Fourier Neural Operator (FNO)) offers a generalized, mesh-free, and scalable approach that allows learning in function spaces of infinite dimension49.

The main idea of NOMPS is centered around learning an operator \(\:\mathcal{G}\) that takes a function (input), such as initial conditions, boundary values, or external forcings. It transforms it to another function (output), such as some displacement field, stress distribution, or temperature profile model (Eq. 1)49.

where \(\:\mathcal{G}\) is an operator; \(\:\mathcal{G}:\mathcal{\:}\nu\:\left(x\right)\underrightarrow{\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:}\mu\:\left(x\right)\) is a functional operation performed on spatial data; and both \(\:\nu\:\left(x\right)\) and \(\:\mu\:\left(x\right)\) are defined over spatial (or spatio-temporal) domains. This differs from the standard formulation of a neural network, which performs input-output functions only on finite-dimensional inputs.

This formulation is beneficial for modeling the carbonation depth in UHPC, as it enables the simulation of complex, evolving physical processes without resorting to explicit numerical solutions of partial differential equations (PDEs), thereby significantly reducing simulation time. NOMPS allows us to model the evolution of carbonation fronts, moisture transport, and thermal gradients in concrete over time, without the need for costly discretization or mesh-based solvers. This ability to process complex data and physical regimes in real time, without the drawbacks of dimensionality, makes NOMPS an ideal tool for large-scale simulations of carbonation in concrete structures. For example, the DeepONet model, consisting of two specialized neural networks (a branch network and a trunk network), receives input function values from discrete sensors and processes query points in the domain. This configuration enables seamless integration of experimental carbonation data, making it ideal for predicting carbonation depth under different environmental and material conditions in FR-UHPC. Furthermore, FNO replaces the traditional convolution operation with the global Fourier transform, making it particularly suitable for capturing long-range dependencies and multiscale behaviors—critical factors in carbonation modeling, where phenomena can extend over large spatial domains.

By integrating NOMPS into the FR-UHPC carbonation prediction framework, engineers obtain accurate, real-time predictions of carbonation front propagation and other critical physical processes, improving the speed and reliability of performance assessments in infrastructure projects. These models are not only faster than traditional solvers, but are also much more scalable, a significant advantage for predictive modeling at both the material and structural levels.

AI-driven pipeline search for regression (AIPSR)

AIPSR introduces an innovative approach to regression modeling by leveraging advanced AI methods to optimize carbonation-depth prediction in FR-UHPC. Unlike traditional machine learning models, AIPSR dynamically adapts to diverse datasets and feature sets, thereby improving prediction accuracy and efficiency over time. The power of AIPSR lies in its ability to intelligently prioritize feature selection and optimize the model based on historical data, input features, and real-time feedback. This innovative system effectively automates feature selection by continuously analyzing data trends and adjusting the model pipeline to focus on the most important variables influencing carbonation depth. Thanks to advanced AI techniques, including dependency graphs, historical results, and real-time model optimization, AIPSR significantly reduces model training time while maintaining high accuracy. Furthermore, it improves the model’s generalization, enabling it to perform effectively across different concrete mixtures and under diverse environmental conditions.

Another key feature of AIPSR is its self-healing mechanism. The system automatically adapts to changes in input properties or environmental conditions. This flexibility ensures the predictive model remains accurate as new data is added or laboratory conditions change. Efficient identification and integration of new data increases the model’s robustness in predicting the carbonation depth of FR-UHPC. Furthermore, AIPSR allows for the creation of custom scenarios, especially for boundary cases, which are essential for simulating carbonation behavior under extreme conditions. These generative models use artificial intelligence to create high-quality experimental scenarios that capture rare or complex carbonation patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed. This capability not only improves prediction accuracy but also ensures the model can handle a broader range of real-world situations, making it more reliable for engineering applications.

Quantum machine learning (QML)

QML is an emerging convergence between quantum computing and machine learning that offers potential benefits for modeling highly complex systems. Unlike classical computing architectures, which process information sequentially, quantum systems exploit superposition and entanglement to enable parallel processing of many computational paths using quantum bits (qubits)50. This feature has led researchers to explore QML as a promising approach for processing multidimensional, nonlinear, and uncertain datasets—conditions often encountered in modeling the carbonation of FR-UHPC.

In the field of carbonation depth prediction, QML methods such as quantum support vector machines, quantum kernel methods, and quantum variation classifiers can provide advanced representation capabilities for complex patterns found in experimental carbonation data. By exploiting quantum parallelism and entanglement, these models can, in principle, capture interactions that are inaccessible to classical algorithms. For example, quantum kernels integrate input variables into high-dimensional Hilbert spaces, potentially improving feature discrimination and prediction accuracy. QML is increasingly being studied for tasks such as feature selection and dimensionality reduction (critical steps for managing the various environmental, structural, and material factors affecting carbonation). However, it is essential to note that the potential benefits of QML in this study remain theoretical, as current limitations in quantum hardware prevent large-scale experimental evaluation compared to classical ensembles. Therefore, the interest of this paper is to establish a conceptual framework and future directions for integrating QML into the carbonation modeling of FR-UHPC, rather than to claim immediate performance superiority over classical methods.

Explainable AI using quantum Shapley values (EAIQSV)

Explainable AI (EAI) aims to make model decision processes transparent, and quantum Shapley values (QSVs) extend this goal to the realm of quantum machine learning. Classical Shapley values, derived from cooperative game theory, determine the ultimate contribution of each feature to the model output by evaluating all possible combinations of features. Despite their robustness and fairness, classical Shapley values can become very expensive to compute due to combinatorial explosion in high-dimensional or nonlinear models51.

QSVs offer the potential to accelerate this computation using quantum algorithms. By exploiting parallelization and quantum entanglement, quantum circuits can, in principle, evaluate multiple feature subsets simultaneously, thereby reducing the computational burden traditionally associated with Shapley value estimation51. In the context of quantum machine learning, QSV offers a path towards interpretable quantum models, allowing the identification of the most influential variables in carbonation depth prediction while ensuring transparency and reliability.

Although quantum algorithms are theoretically capable of reducing computational complexity, their practical advantage over classical SHAP estimation has yet to be experimentally demonstrated, mainly due to current hardware limitations and the early stage of QSV research. Therefore, in this study, QSV is considered a promising methodological improvement rather than a proven alternative to classical SHAP estimation51,52,53. This paper highlights the future potential of QSV for real-time interpretability of quantum carbonation depth models by presenting ongoing developments, including hybrid quantum-classical SHAP estimation, noise-resistant quantum circuits, and the integration of QSV into QML learning loops. QML and QSV together provide a conceptual framework for future research directions in explainable quantum artificial intelligence for carbonation modeling of FR-UHPC reactors. However, their experimental advantages over classical methods remain to be demonstrated in future studies as more powerful quantum materials become available.

Data set preparation

We focused on the carbonation resistance of a newly developed FR-UHPC composite that offers remarkable mechanical performance, ultra-low permeability, unmatched durability, and exceptional resilience in harsh environments. The advanced matrix was created with high-reactivity Portland cement, silica fume, steel microfibers, and a polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer. The concrete was designed with an extremely low w/c ratio of 0.15–0.25 to reduce the formation of interconnected capillary pores, which serve as primary conduits for CO₂ ingress during carbonation. The low w/c ratio is essential for FR-UHPC systems because wacerestto candidacy improves dura porosity and further strengthens collapse under external harab, especially circulatory carbon dioxide.

Silica fume was added at 10% to 25% by weight of the total binder content to improve densification and pozzolanic reactivity further. Silica fume participates in secondary hydration reactions due to its ultrafine particle size and high specific surface area. It reacts with calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂) formed during cement hydration, which gives rise to more calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel. The newly formed C-S-H gel strengthens, fills pore spaces, and ultrafines the cement matrix, chemically and spatially reinforcing the cementitious material’s microstructure. Optimizing the microstructure reduces CO₂ gas diffusivity and permeability, thereby improving the composite’s carbonation resistance.

Steel fibers with a length of 13 mm and a diameter of 0.2 mm were incorporated into the matrix at a volume fraction between 1% and 2%. These microfibers have a balance between mechanical and durability functions. Mechanically, tensile strength, ductility, and post-cracking behavior are improved due to efficient crack-bridging reinforcement. In summary, these microfibers are essential for controlling microdamage caused by carbonation-induced shrinkage or redistribution of internal stresses. This reduction of crack formation helps maintain the dense matrix and reduces the predominant pathways for the advancement of the carbonation front.

Due to the very low w/c ratio, a polycarboxylate-based high-range water-reducing admixture (HRWR) was added at a dosage of 1%−4% of binder weight. This admixture improves the mix’s flowability and particle dispersion through steric hindrance and electrostatic repulsion among the cement grains, therefore reducing yield stress and plastic viscosity. This improvement in rheology enables placement and compaction without increasing water and helps maintain low porosity and high durability.

The mixing protocol was precisely managed and carried out in a high-shear planetary mixer, which ensures uniform dispersion of all components. The process began by dry-blending the cement and silica Fume for 2 min to achieve a uniform distribution of fine cementitious particles. After that, the mixing water and HRWR were added for over 3 min to ensure good wetting and uniform dispersal of all admixtures. Upon forming a uniform paste, steel fibers were added to prevent agglomeration and balling. This was followed by a 1-minute low-speed mixing step to initiate fiber incorporation, then a 4-minute high-speed homogenization phase to fully disperse all fibers and binder particles. Total mixing time was 10 min. All parts were measured and calibrated with a precision of ± 0.1%, resulting in highly reproducible blending quality with fully automated digital scales.

After mixing, specimens were placed into cylindrical stainless steel molds with a 100 mm diameter and a 200 mm height. A thin layer of mold release oil was applied to the stainless steel molds, which were filled in two equal strata and compacted using a vibrating table or manual tamping to eliminate trapped air. The surfaces were smoothened and sealed with polyethylene film to minimize moisture evaporation, after which the specimens were stored at 23 ± 2 °C for 24 h before demolding.

After initial setting, the specimens were subjected to various curing regimes to study the effect of hydration age on carbonation resistance under fixed volume and shape. Samples were cured either by (1) immersion in saturated limewater at 20 °C, (2) steam curing at 60 °C and 90% RH for 24–48 h, or (3) ambient conditions at 23 ± 2 °C and 65 ± 5% RH. Total curing periods ranged from 29 to 82 days, allowing the examination of carbonation response at varying levels of hydration maturity. Longer curing periods are generally beneficial in terms of increasing C-S-H gel formation and the densification of the microstructure, which retards the rate of carbonation penetration. Post-cured specimens were oven-dried at 50 °C for 48 h to equalize their internal moisture content, after which they were cooled in a desiccator to room temperature. The specimens were then placed in a specially designed accelerated carbonation chamber that provided tight control over environmental exposure parameters. The following conditions were controlled for the entire 28-day carbonation exposure period:

-

(1)

Carbon dioxide (CO₂) concentration was controlled between zero and 3%. This parameter is essential as it influences the diffusion gradient and reaction rate of CO₂ with calcium hydroxide and C-S-H phases. While higher CO₂ concentrations enhance carbonation rates, they must be limited to avoid unrepresentative carbonation profiles.

-

(2)

Relative humidity was maintained between 50% and 75%, an ideal range for carbonation. At this range, there is adequate moisture available for the formation of carbonic acid (H₂CO₃), which aids in the leaching of calcium, though still allows CO₂ gas to diffuse through partially saturated pores. At less than 40% RH, pores become too dry to support carbonation; at greater than 80% RH, pore saturation prevents gas entry.

-

(3)

The temperature was set between 15 and 35 °C because higher temperatures improve the kinetics of both gas diffusion and chemical reactions. These ranges avoid thermal damage or shrinkage while allowing reaction-driven pore pressures to sustain reactive gas influx.

-

(4)

The curing time was the key independent factor. Shorter curing times resulted in incomplete hydration and a more porous microstructure. In contrast, longer durations led to greater C-S-H content and greater resistance to carbonation ingress.

After the carbonation period, each specimen was split longitudinally, and the newly exposed surface was immediately treated with a 1% phenolphthalein alcohol solution. This solution acts as a pH indicator, distinguishing carbonated regions (pH < 9.5; colorless) from uncarbonated regions (pH > 9.5; pink). Using digital Vernier calipers with an accuracy of ± 0.01 mm, ten equidistant points were measured along the axial direction of the sample. Average carbonate depth was determined and used as the primary output variable in the following data modeling. Figure 1 summarizes all steps of sample preparation and carbonation depth measurement.

Statistical analysis of the data set

As with any machine learning project, the dataset requires preliminary statistical analysis to understand hidden patterns, the distributions of variables, relationships among variables, and any potential outliers or redundancies that could compromise the model. Input features and their respective target variables can be understood using correlation matrices, box plots, permutation feature importance (PFI) analysis, partial dependence plots (PDPs), SHAP analysis, and related methods. This understanding is very valuable for feature selection, dimensionality reduction, and preprocessing steps, which are vital for evaluating model metrics. In addition, statistical diagnostics help confirm assumptions about data quality, thereby increasing the reliability, robustness, and generalizability of predictive models for real-life applications. In the following, several statistical analyses will be performed on the data used in this study.

Analysis of pearson correlation matrix

Figure 2 shows the Pearson correlation matrix, which provides an overview of the statistical relationships among the input variables and the target variable (carbonation depth). Among all predictors, curing time showed the strongest inverse correlation with carbonation depth, with a robust negative correlation coefficient (r = −0.76). This means that the longer the curing time, the less carbonation progression is observed, likely due to more pronounced hydration processes, greater formation of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H), and reduced capillary porosity. These microstructural improvements reduce the matrix’s permeability to CO₂, thereby limiting the ingress of carbonation.

Carbonation depth is also moderately positively correlated with temperature (r = 0.35). This observation implies that higher temperatures may accelerate carbonation. This behavior is consistent with the principles of diffusion and reaction kinetics, where higher temperatures are known to enhance the diffusivity of CO₂ and the reaction rate with calcium hydroxide. However, this might also result from the combined effects of temperature and relative humidity, as excessive heat may alter the pores’ internal saturation states.

The content of silica fume exhibited a moderate negative correlation (r = −0.24) with the carbonation depth. This correlational outcome supports the assumption that the greater the addition of silica fume, the greater the matrix densification due to pozzolanic reaction and the reduction of portlandite, resulting in enhanced resistance to carbonation. Other parameters, such as the volume fraction of steel fibers, the amount of cement added, and the carbon dioxide concentration, showed little or no statistically significant correlation with carbonation depth. This suggests that the relationships involving these parameters are non-linear or involve interactions too intricate to be adequately represented by linear correlation analysis.

PFI and PDP analyzes

The PFI analysis evaluates the influence on model features by assessing how feature values affect model accuracy. Specifically, value randomization of a feature results in a quantifiable reduction in the model’s performance attribute, reflecting the feature’s importance. This methodology captures both linear and nonlinear interdependencies and, thus, complements the Pearson correlation matrix effectively. The PFI analysis presented in Fig. 3 shows that curing time, temperature, and silica fume content are the most critical parameters affecting FR-UHPC specimens’ carbonation depth. These results align well with the trends observed in the Pearson correlation matrix, thus supporting the hypothesis that the hydration processes, time, temperature elevation, and binder composition strongly influence the FR-UHPC’s resistance to carbonation.

PDP analysis visually demonstrates the isolated impact of specific features on predictions. It does so by averaging the influence of other model parameters, shedding light on the most pertinent features that dictate the carbonation depth.

The PDP analysis shown in Fig. 4 indicates that curing time significantly decreased the model performance when permuted, therefore emerged as the most critical predictor of carbonation depth. This finding highlights the significance of hydration maturity and microstructural development and elevates understanding of their particulate role in resistance to CO₂ ingress. In UHPC, prolonged curing periods not only enhance the formation of C-S-H gel but also reduce the calcium hydroxide content and pore connectivity, which are key to resisting carbonation. Indeed, temperature was the second most important feature, further affirming the reasoning from the correlation analysis. High temperature is likely to enhance the diffusion coefficient of CO₂ in the pore solution and the rate of carbonation reactions.

Nevertheless, its ranking importance in PFI confirms that the effect of temperature is not purely linear and interacts with humidity and curing conditions. Silica fume content ranked third among the most critical factors. This is consistent with the secondary dehydration reaction’s contribution to system closure via matrix densification. Its moderate importance score within the carbonating PFI framework suggests that this silica fume is not a dominant factor in the carbonation process but rather serves as a secondary hurdle, refining the pore structure and diminishing the calcium hydroxide content, thereby reducing the reactants available for carbonation. The features, such as the volume of the steel fibers, the amount of cement, and the dosage of superplasticizer, exhibited low permutation importance, signifying that these factors have a negligible direct influence on the carbonation depth. These factors might have an indirect, threshold-based influence, especially during certain curing and environmental conditions, such as inertia.

Overall, the PFI results reconfirm that time maturity (curing time) and thermal parameters (temperature) are the most significant factors determining the carbonation depth in FR-UHPC, followed by compositional silica fume as a densifier. The results also reaffirm the dependence of advanced cementitious systems on compositional and structural nonlinearity, with interaction-driven complexity in carbonation processes, highlighting the importance of a model-based approach over a simple univariate correlation approach.

Box plots

The box plots in Fig. 5 provide a comprehensive visualization of the distribution, central tendency, and potential outliers for each input parameter used in the study of FR-UHPC. These box plots provide a thorough visualization of the parameters used as inputs to the analysis and show the interplay among outliers, unique values, and the overall distribution. We will also discuss the unusual feature of the data that stands out from the other coherent observations: the central tendency. The box also provides important hints about the statistical inferences regarding the data.

The cement content displays a fairly symmetric distribution shape with the median located roughly at the center of the interquartile range (IQR). However, numerous outliers are visible above the upper whisker, indicating that some samples contained high cement content, which may indicate specialized designs aimed at UHPC. The range appears to extend from roughly 715 to over 907 kg/m³, suggesting diverse augments of cement binder across the samples.

The w/c ratio has a narrow IQR, with values concentrated between 0.15 and 0.25, and the median slightly below the center. This indicates that a w/c ratio of 0.2 is optimal for this dataset with minimal variability among samples. This value is typically low, especially in durable or high strength concrete. Notably, the lack of outliers demonstrates consistent proportioning of materials, which greatly enhances reproducibility and stability of predictive models.

The silica fume content shows a wider spread variance of approximately 10% to 25% with the mean sitting somewhere in the middle. This parameter also does not have any noticeable outliers which suggests that the incorporation of silica fume was well-controlled. The symmetrical distribution signifies that the data equilibrium is precise balanced between moderate and high levels of pozzolanic replacement.

The percentage of superplasticizer is evenly split between roughly 1% and 4%, but the median is slightly lower than the center suggesting a bit of a pull to the lower end. The symmetry and compactness of the box plot hints that the admixture was well-controlled suggesting that it is a common occurrence in mixes requiring high workability coupled with a low water to cement ratio. There are again no outliers which suggests that chemical admixture usage is uniform across samples.

Volumes of steel fibers show a percent partition of approximately 1% to 2.5%, exhibiting a symmetric IQR cap with the median in a central position. This indicates the fiber dosage is uniformly varied across samples which is essential for accurately capturing the sample’s non-linear influences on mechanical performance. No outliers bolsters this claim along with the assumption that the experimental design is fixed. Curing time shows a wider IQR where the median is centered without outliers, spanning roughly 28 to 120 days. This emphasizes the range of curing diversity within the dataset which is important for understanding strength development over time. The consistent spread suggests that the dataset captures early, mid-range, and long-term strength data.

CO₂ concentration ranges from slightly zero to 3%, featuring a central median along with a slightly greater dispersion than average. This indicates exposure to different carbonation environments, both naturally occurring and accelerated. The lack of outlier values suggests systematic change rather than random error in measurement.

Relative humidity is moderately spread around 50% to 75% with the median coinciding near center. This range indicates the degree of variation in environmental exposure which could influence the degree of hydration and drying shrinkage. The symmetrical distribution is helpful to ensure the model accounts for the influence of ambient humidity on compressive strength.

Lastly, temperature covers 15 °C to 35 °C with no outliers, median centered, and symmetric spread. This spans both normal and high curing temperatures which is important for modeling the influence of temperature on hydration kinetics and strength gain. The lack of outliers indicates all temperature settings were purposefully designed within known expected boundaries for the experiment.

Concisely, the box plots together validate the provided dataset for its control and consistency across experiments. The majority of the variables exhibit symmetrical distribution without extreme outliers which ensures a well-conditioned dataset for the machine learning model training.

SHAP analysis

SHAP is an advanced interpretability framework based on cooperative game theory which enables the dismantling of predictions made by sophisticated machine learning models into measurable individual input feature contributions. Unlike traditional feature importance techniques, SHAP works by averaging contribution of each feature and ranking them, however, with SHAP’s ranking, we are also able to see the effect of changing a particular feature on the prediction of an instance. This ability to resolve herarchcies of features and then provide local explanation makes SHAP distinctively effective in deeply understanding non-linear interactions, model biases and critical predictive thresholds, especially in material science where performance outcomes such as carbonation depth are influenced by composition or curing variances.

Figure 6 presents the summary plot from SHAP analysis with the described results providing a detailed insight into how each feature impacts the model’s prediction of carbonation depth. It can be observed that curing time is the most impactful feature and exhibits a strong negative effect (depicted in red) where increasing hydration leads to less carbonation. On the other hand, temperature exerts largely positive SHAP values for greater temperature values which implies that higher curing or exposure temperatures tend to enhance carbonation, likely because of improved CO₂ diffusion and faster reaction rates. Silica fume content shows a strong inverse relation where high levels of silica fume lower carbonation depth because of strong matrix densification, enhanced pozzolanic activity, and strong reaction products. Of particular interest is the behavior of some features such as steel fiber volume, superplasticizer content, and w/c ratio which blend together to show low consistent importance, pointing to some direct or indirect dependence or carbonation depth within the bounds of the examined values.

The bar graph illustrated in Fig. 7 captures the average contributon of each input toward the output in value quantifying model. Dominating the mean SHAP value is curing time, verifying its primary importance in resisting carbonation due to microstructural maturity and C-S-H development. Serving as the next two most important contributors are temperature and silica fume content which highlight their roles in modifying microstructure and carbonation kinetics. The relatively lower SHAP values of CO₂ concentration and relative humidity suggest that within the constraints of the controlled dataset, their influence on carbonation depth is more secondary than intrinsic material characteristics and history of curing. The extremely low SHAP scores for w/c ratio, superplasticizer content, and steel fiber volume denote their effects, if any, being very small and contextually interdependent in terms of the frameworks used.

The SHAP dependence plots shown in Fig. 8 reveal feature impact on predictions within their scope as well as interaction with other features. When steel fiber volume is held constant and silica fume content increases from 10% to 25%, the SHAP values become progressively more negative, demonstrating a pronounced mitigating effect on carbonation depth. The interaction with steel fiber volume seems weak because the relationship follows the same trend regardless of fiber content, supporting the dominant chemical influence of silica fume as a physically reinforced component. SHAP values exhibit a near-linear increase with rising temperature, suggesting that predicted carbonation depth increases at higher temperatures. The effect of temperature increase is stronger from 25 °C to 35 °C, where elevated diffusion and reaction rates are probable. There is a slight interaction with w/c ratio; higher w/c ratio exacerbates the adverse impact of temperature, indicating that porosity influences temperature sensitivity. Most striking is the trend associated with curing time, where SHAP values demonstrate aggressive decline with increasing curing time, reflecting extended curing’s strong carbonate protective impact. The curve flattens after approximately 100 days, suggesting a plateau in the benefits of resistance to carbonation gained. Interaction with fiber volume is minimal, indicating overwhelming dominance of curing forces over fiber reinforcement in carbonation control.

Together, these visual representations provide insights into the physical and chemical processes involved in carbonation of FR-UHPC systems from multiple dimensions. They confirm feature importance ordering from PFI and Pearson analysis and additionally reveal some pivotal interactions along with several critical inflection points that are important for durability design optimization.

Data normalization

Before training the machine learning models, all input features were subjected to standard normalization using the StandardScaler function from the scikit-learn preprocessing module. This model training step scale bias potential is removed safeguards against any bias due to scale. In this study, all input variables were normalized using standard score normalization (z-score scaling). The StandardScaler removes the mean and scales to unit variance for each feature which is given as Eq. (1).

where \(\:X\) is the original feature value, \(\:\mu\:\) is the mean, and \(\:\sigma\:\) is the standard deviation of the respective feature.

Such a transformation creates a normalized feature space where the predictors exhibit a mean of 0 and variance of 1. The scaling process mitigates the risk of numeric instability, disproportionate weighting, or biased model fitting due to dominion from certain features with larger numerical ranges, such as cement content in kg/m³ compared to fiber volume in %. Moreover, additional weighting during model fitting is avoided. Furthermore, non-uniform standardized normalization enhances the convergence speed of optimizers that rely on gradients, while also enhancing the ensemble performance on distance-based algorithms and tree-based models. Verifying the dataset after transformation revealed means close to zero and standard deviations near one across all features, confirming successful normalization and persistent alignment throughout the training pipeline.

Modeling and analysis of results

In this section, the modeling structure for each of the machine learning techniques used in this article will be discussed, along with a comprehensive analysis of the results.

Neural operators for modeling physical systems (NOMPS)

The following will explain in full and detail the structure used for the NOMPS model in several steps:

-

Tensor conversion and DataLoader preparation.

After the data was normalized, it was transformed into PyTorch tensors, which are the primary building blocks of the PyTorch deep learning framework. In order to meet the expected input format of the 1D convolutional layers used in the model, the input features were augmented with an explicit channel dimension. These tensors were then combined into a TensorDataset and processed with a DataLoader for mini-batch training with shuffling. The batch size was set to 16, which was a good balance between computational resource and noise in the gradient computation.

-

Model architecture: RobustFNO1D.

The focus of this study was directed to the neural network model known as RobustFNO1D, which was a lightweight architecture focusing on feature maps where 1D convolutional filters were applied to extract spatial relations between features. The deep learning model architecture was made of three stages of convolution that were followed by batch normalization, ReLU, and Dropout regularizations. Overfitting was addressed with dropout layers which randomly turned off a fraction of the neurons during training and batch normalization, which stabilized learning by standardizing layer inputs, was also included. For every sample, a mean operation was applied spatially to the output of the last convolutional layer to give its output as a single scalar value, which was compatible with the nature of the variable it was meant to yield, hence there being only one prediction per sample. The hyperparameter hidden_dim = 64 which was set for the convolutional layers was also used for the filters and bandwidth bound the capability of the network. This value could vary depending on the given validation stage or the complexity of the physical system being modeled.

-

Optimizer and learning rate scheduler.

The training of the model was done using Rectified Adam (RAdam) within a Lookahead Optimizer. RAdam fixed the issues with the Adam algorithm during the initial training steps by correcting the variance of adaptive learning rates. Improvement on convergence was done by Lookahead through iteratively updating ‘fast weights’ and syncing them with ‘slow weights’ to create smoother optimization paths. Setting the starting learning rate to 0.001 and additionally applying weight decay of 1 × 10− 4 allowed for L2 regularization and prevented overfitting by dissuading overly complex models through sculpting a simpler hypothesis space. Also, a ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler was added, which lowered the learning rate when validation loss plateaued. This enabled the model to adjust weights at finer scales during convergence, hence overcoming the issues of local minima and overshooting during later epochs.

-

Early stopping mechanism.

In order to avoid an overfit model and needless workload, an early stopping strategy was used. If the training loss plateaued for a certain number of epochs (in this case, early_stop_patience = 20), the training would stop automatically. The model was saved and subsequently set to the lowest training loss. Using this approach enabled access to the model which was shown to achieve the best generalization performance during training.

-

Optimization considerations.

The code contains several hyperparameters that look appealed to be optimized at first glance. The hidden dimension controlled the model’s capacity. Greater values allowed the network to capture more complex patterns but also raised the chances of overfitting, increased training time, and complicated network management. The learning rate for convergence was essential, where too high values could cause divergence and too low values could cause stalled training. The dropout rate, used to balance the generalization power and underfitting, was usually set between 0.1 and 0.5. Batch size affected memory consumption and the precision of the gradient estimates, and was usually tuned together with the learning rate to improve the training dynamics. Moreover, the kernel size and padding employed in the convolutional layers defined the model’s receptive field and sensitivity to the edges of the data. Such hyperparameters were solved using grid search, random search, or more sophisticated automated techniques such as Optuna and Ray Tune.

-

Evaluation metrics and visualization.

Upon completion of the training, the model was assessed using the provided test dataset (160 data points). As per the outlined methodology, all transformations are reverted using the standardization technique’s inverse transformations, which was previously applied to the model. In the end, sample index was utilized to highlight both the predicted and actual outcomes corresponding to carbonation depth.

-

Results analysis.

The results given in Fig. 9; Table 1 demonstrate how the NOMPS model predicts carbonation depth in relation to the amount of carbonate. The line graph (Fig. 9) plots a direct comparison between the actual carbonation depth values (solid blue line) and the NOMPS model predictions (dashed red line) for each of the 160 test samples. It can be observed that the predicted curve doesn’t deviate much from the actual data and seems to capture most of the significant fluctuations. This suggests that the model was useful in learning the existing patterns in the input features. Even though a few local gaps between the prediction and the actual values within a single sample can be noted, it can be assumed that these errors were modest and random, not indicating systematic overfitting or bias toward the model.

In Table 1, four evaluation metrics including coefficient of determination (R2), root mean squared error (RMSE), mean absolute percentage error MAPE), and variance accounted for (VAF) are reported. R² = 0.74 tells us that 74% of the actual carbonation depth value variance can be explained by the model. Given noisy real-world data, R² greater than 0.7 is considered to assume a good model, especially when dealing with regression and physical systems. The breakdown of RMSE = 0.85 suggests that, when averaged across multiple predictions, the model is off by less than a millimeter. Considering the dataset’s carbonation depth values that range between 7 mm and 15 mm, such absolute error is acceptable for a majority of engineering purposes. Achieving the MAPE of 0.06 demonstrates that the model is reliable in terms of relative accuracy. Generally, a MAPE under 0.10 is awarded as impressive due to the fact that it shows constrained deviation across the dataset, regardless of variation of carbonation depth. VAF = 0.87 further strengthens the R² score by interpreting that model accounts for 87% of the outputs variance, which corresponds greatly with the R² value. It further substantiates the model’s capability of simulating the functional relationship between the model inputs and carbonation depth.

Overall, the NOMPS model appears to estimate carbonation depth with high precision given the NOMPS’s visual validation in Fig. 9 and the blend of achieved R², VAF, RMSE, and MAPE scoring. The model’s prediction and visual representation score intersect quite agrees, giving validation to the model. The only reasons why such minor discrepancies occur can be attributed to negligible noise present in the data or unmapped plausible factors, but in terms of the accuracy, all is flawless. The results suggest the NOMPS architecture can reliably and efficiently model carbonation depth phenomena in concrete and similar physical systems.

AIPSR

The AIPSR framework provides Auto machine learning (AutoML) based AIPSR model with fully automated predictive modeling features by discovering and optimizing the relevant machine learning pipelines for a given scientific regression problem. In this work, we implemented the open-source AutoML library tree-based pipeline optimization tool (TPOT) which is built on genetic programming to optimally establish the model for predicting concrete’s carbonation depth. The subsequent sections will discuss in detail the decsiption of the structure used for AIPSR model in several steps.

-

AutoML configuration using TPOT.

To initiate the AIPSR process, the TPOTRegressor class was instantiated with carefully selected hyperparameters that govern the scope and behavior of the AutoML search. The following key parameters were specified:

generations = 10: This setting defines how many times the algorithm will try to enhance the pipelines iteratively by improving them. Each generation marks a new phase where fresh pipelines are created using a blend of evolutionary crossover and mutation techniques. While raising the number of generations does widen the scope of the search, it also increases computation time in a linear fashion.

population_size = 40: This value bounds the count of candidate pipelines assessed in each generation to 40. With a larger population, the model’s configurations tend to be more diverse, giving the models a better chance at overcoming local optima less than best solutions encountered.

verbosity = 2: This setting will define the level of output during the model training. Setting it to 2 will make sure that the evaluation for every pipeline as well as the evaluation metrics are printed making the process easy to understand and debug.

scoring=’R2’: The main metric was set to be optimized with R² score. This value assesses the ratio of the variance in the dependent variable that is accounted for by the model. This metric is especially important for regression tasks where the model is expected to provide accurate predictions and correlate well to the outcome variables.

random_state = 42: Using a fixed random seed ensures that the results will be reproducible which enables the consistent performance of the model across different runs.

n_jobs = −1: With this configuration, TPOT is free to make use of every available CPU core, which drastically shortens the time required to search for the models with parallel processing.

max_time_mins = 20: This is a reasonable AutoML time limit. This parameter is adjustable or even omitted based on the available computational resources and the needs of the task at hand.

-

Pipeline discovery and model evaluation.

After configuring an instance of TPOTRegressor, it was necessary to fit the model to the training data by calling the.fit() method. TPOT, for its part, started with an uniformly random population of machine learning pipelines that included many clustering feature selection algorithms, different data preprocessors, and regression algorithms like RF, gradient boosting, or support vector regression (SVR). In later generations, pipelines competed for their R² score on cross-validated subsets of the training data. The best individuals were combined and preserved to gradually improve ensemble-based models. After completing the AutoML search, the final model was used to predict carbonation depth on the data from the test set. Predictions were made based on the test data and compared against the actual values using statistical metrics.

-

Pipeline export and reusability.

Along with prediction generation, TPOT also offers a way to export the complete pipeline as an executable Python script via the.export() method. The produced file, best_pipeline.py, includes all the required steps for preprocessing, modeling, and inference. This increases the reproducibility, transparency, and readiness of the modeling workflow for deployment.

-

Optimization strategies and best practices.

To further improve the performance of the AIPSR framework, additional optimization strategies were employed. The more advanced models were located by increasing value of the parameters for generations (e.g., 50–100) and population_size (e.g., 50–100) which improved model depth. Greater computational time was encountered while attempting to find more advanced models. To fit the needs of the study, several other scoring metrics also were used such as neg_mean_squared_error, neg_mean_absolute_error, and explained_variance. In some settings, early_stop was set so that the evolutionary algorithm would freeze the process after a fixed number of generations without meaningful progress to improve resource efficiency. Finally, domain-specific customization of the pipeline was achieved when the search space was limited to specific model types and preprocessing steps through defining a custom config_dict configuration dictionary.

-

Results analysis.

As shown in Fig. 10, a comparison between true and predicted carbonation depth values obtained from the AIPSR model test dataset is presented. It is clear that predicted curve follows fiel measurements for all values of sample index (0 to 160) and all high frequency oscillations and broader movement of the carbonation depth are captured. Moreover, quantitative alignment of the peak and trough correspondence suggests that AIPSR model reconstructions not only provide the mean value well but are also sensitive to local changes within the data. Even though minor differences can be noted around certain regions like 40 and 120, the strong agreement between these two curves appears unwavering.

The model accuracy described in the qualitative section is further corroborated by quantitative performance evaluation metrics displayed in Table 2. The R2 is 0.83, meaning that the model captures 83% of the variance in the carbonation depth for the assigned test set. Such level of explanatory power is significant especially for materials science and civil engineering fields where overpredictive environmental factors and microstructural uncertainties usually complicate the problem of model forecasting. The RMSE of the model is 0.69 mm translating to the average prediction error magnitude. A lower range of RMSE improves absolute accuracy of predictions and shows that the model is consistent across samples tested. The MAPE was measured at 0.04, indicating that the model prediction during on average overestimated or underestimated by only 4% which is exceptionally good for engineering situations demanding accuracy. Furthermore, the VAF value is 0.93, reinforcing that the predicted values capture 93% of the variance in the original data distribution.

Summing up, the AIPSR model exhibits powerful qualitative and quantitative predictive performance. It has low error rates for various statistical measurements. AIPSR’s high R² coupled with low RMSE and MAPE as well as high VAF demonstrates that the AIPSR pipeline successfully learned the underlying intricate dependencies between the input variables and carbonation depth, thus, providing a robust and interpretable solution for regression tasks in modeling physical systems.

Quantum machine learning (QML)

The designed QML pipeline combines traditional data handling with quantum computing techniques to estimate carbonation depth in concrete structures. This method takes advantage of the power of quantum circuits placed in the neural network to extract complex patterns from multi-dimensional feature spaces. The upcoming key points will elaborate the explanation of the model structure which is designed for QML in a stepwise fashion.

-

Quantum Circuit Design.

The quantum circuit, which serves as the backbone of the model, was built in PennyLane using the default.qubit simulator. The circuit features AngleEmbedding, which encodes classical features into qubit rotations, along with a configurable number of StronglyEntanglingLayers that apply nonlinear entanglement patterns among the qubits. The number of layers (i.e., depth) relates to how much the quantum circuit can express, with deeper circuits enabling more complex relationships to be captured at the expense of increased circuit complexity and longer training time. The circuit finally performs measurement of Pauli-Z expectations on each qubit, yielding a real-valued vector representation of the quantum output.

-

Hybrid quantum-classical architecture.

The results from the quantum circuit were sent to a classical fully connected neural network, forming a hybrid QML model. The classical part contained one hidden layer with adjustable amount of neurons (hidden dimension) and ReLU activations followed by a linear layer that predicted the carbonation depth as an output. This architecture harnesses the effectiveness of quantum computing for feature extraction while still incorporating the adaptability of classical algorithms.

-

Model training and loss minimization.

The hybrid model training was conducted with the AdamW optimizer which applies weight decay to limit overfitting and ensures fast convergence through an adaptive learning rate. Because the problem is regression-based, MSE was used as the loss function. The model was trained for 100–150 epochs, and evaluation was performed on a separate test set by measuring the predicted and actual carbonation depths.

-

Hyperparameter optimization using Optuna.

In order to improve the predictive accuracy of the model, a Bayesian optimization approach was applied through the Optuna framework. The objective function was set to return the R² score obtained on the test set which indicates the generalization ability of the model for its unseen data. A total of 20 trials were performed, each involving the training of a QML model with hyperparameters tuned by Optuna’s Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) suggesting a new configuration. As shown in Fig. 11, the best configuration was found at depth = 5, hidden_dim = 32, and lr ≈ 0.00627 with weight_decay ≈ 1.68e-5 which gave an R² score of around 0.69 on the test data. Compared to a manually set parameter approach, this optimization greatly improved the accuracy and robustness of the model.

-

Results analysis.

In Fig. 12, a graphical depiction contrasts the actual carbonation depth values and those predicted by the optimized QML model, which is further summarized in Table 3 alongside four quantitative metrics evaluating the model’s predictive accuracy on the test data set. Collectively, these results shed light upon both the QML model’s qualitative performance and its quantitative precision in estimating carbonation depth for concrete structures. From Fig. 12, it can be observed that the predicted values (red dashed line) track the general trend of the true values (solid blue line), which demonstrates that the model has some ability to capture the essence of data patterns. Although the predicted series exhibits local deviations, a substantial portion aligns closely with the actual observations. Usually, the model appears to effectively capture both the degree and direction of change. At the same time, it is clear that some high-frequency noise and sharp spikes found within true carbonation depth values are not fully represented within the predictions, indicating generalization by the model leads to smoothing these values.

Numerically, the R² score of 0.69 shown in Table 3 indicates that roughly 69% of the variance in the target variable is explained by the QML model. This score provides a strong indication of the model’s reliability in performing regression analyses, particularly in non-linear, intricate input-output relationships. The model also registered an RMSE of 0.95, underscoring its advancement compared to average deviation between actual and predicted values in consistent units. Also, the model’s estimation accuracy is confirmed by the MAPE of 0.08, which translates into relative errors averaging 8% from true values. Such precision can be especially valuable in assessing the durability of concrete structures where reliable estimates of carbonation depth are essential. Additionally, a VAF of 0.82 further supports QML model performance claiming that 82% of the variance in the test data is captured, which is a high ratio considering regression modeling standards.

Overall, the QML model continues to perform remarkably well for this particular task. Its capability to capture quantum features with quantum embedding and process them with classical learning layers has allowed it to carve out meaningful latent encodings that precede accurate predictions. Although some extreme variations may be out of reach, the overall fit along with relevant statistical measures show that the model strikes a balance between overfitting and generalization. This makes it especially useful in the context of further development of quantum-enhanced modeling of material degradation phenomena.

Explainable AI using quantum Shapley values (EAIQSV)

In this article, the EAIQSV model integrates the following three elements: (i) A feedforward neural network, (ii) Optuna-based hyperparameter optimization, and (iii) Explanation via SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) which has been inspired by quantum feature interactions akin to superposition and entanglement. The model that will be explained in the upcoming key points has been tailored for QML and will be presented in a stepwise manner.

-

Model architecture.

The main predictive model is a shallow fully connected neural network called SimpleNet which was developed in PyTorch. It has one hidden layer, which is activated with a ReLU function, and one output neuron that performs regression tasks. Such a straightforward architecture makes the model interpretable and captures the nonlinear interactions between the input features and the carbonation depth. The width of the hidden layer, referred to as hidden_dim, is a tunable hyperparameter which provides flexibility to the model’s complexity according to the intricacies of the dataset.

-

Hyperparameter optimization using Optuna.

For obtaining the best combination of hyperparameters, the Optuna framework was used. For the EAIQSV model, two important hyperparameters are optimized:

Learning rate (lr): The rate at which the model parameters are updated. It is sampled from a logarithmic uniform distribution ranging from 10− 4 to 10− 1. This controls the rate of adaptation during training.

Hidden layer dimension (hidden_dim): The hidden layer neuron count affects the model’s representation capability. Candidate values are drawn from the discrete set {8, 16, 32, 64}.

An optimization loop performs training with a new model for each trial configuration for 100 epochs. The model is then tested, and performance is measured with a test set. The configuration with the best performance is used to retrain a final model for interpretation. In this case, the configuration was determined by the highest R² score.

-

Model explainability via SHAP values.

To explain the predictions done by the model, SHAP is used to compute Shapley values, which come from cooperative game theory, to separate the measured value into parts contributed by each feature. The SHAP framework approximates these values with KernelSHAP, which is model agnostic and works with PyTorch models. The results of this step interpretability provide a global feature importance evaluation which summarizes the global and local influence of variables driving carbonation behavior, and local explanation for individual predictions. The EAIQSV could be metaphorically justified through quantum mechanics, where entities exist in superposition of states and influence each other non-locally, arguing that the contributions of features are non-linearly entangled. SHAP values provide a quantum-like decomposition of the prediction responsibility which each feature can be considered as a part of making the prediction and thus are used to give interpretable insights into the workings of the model.

-

Results analysis.

As shown in Fig. 13, a line plot is used to show the true values of carbonation depth alongside its predictions for the entire test set. It can be seen that the predicted values match closely with the true values for most sample indices, which denotes that the model is able to learn the underlying structure of the data. In highly oscillatory regions, some small differences can be seen, but on the whole, EAIQSV model is able to capture the overall shape and the maxima of the signal. The model also shows low deviation in flat or moderately varying areas, meaning that it is resilient to low-variance and moderate-variance regimes. There is no systematic over or under prediction for the true value, which is an indicator that bias is low for the model. All these observations visually confirm that the model is not overfitting the training data, and generalizes well.

As per Table 4, R² shows that 78% of the variance in the carbonation depth is dependent on the EAIQSV model. This high figure suggests that the model has sufficiently captured the functional relationship between the processes involved and thus can be relied upon for further predictions and sensitivity analyses. An RMSE of 0.79 mm suggests that the predicted values are, on average, less than 1 mm away from the actual measurements. This level of precision is more than acceptable in civil engineering and materials science. With a MAPE of 6%, the model achieved good relative accuracy for all predictions in the test set. In engineering, a MAPE under 10% is considered superb, especially in the presence of noise like that of the carbonation depth measurement. Having a VAF of 89% means the model explains a great deal of the target’s variability, and this reinforces the conclusion drawn from the R² score while further demonstrating the model’s ability to simulate the physical system’s behavior.

The results shown in Fig. 13; Table 4 give both visual and statistical proof confirming the EAIQSV framework’s effectiveness. The model through quantum-inspired Shapley analysis captures the complexity of the carbonation depth dynamics in a truly interpretable manner. Thus, EAIQSV stands out as a strong contender for implementation in engineering decision support systems, which require trust and transparency in addition to accuracy.

K-fold cross-validation

K-fold cross-validation is a trusted and widely adopted way to check how well a predictive model will perform on new or unseen data. The original dataset is divided into K roughly equal-sized pieces, known as folds. During each round of the procedure, one of these folds is set aside and treated as the validation set, while the other K-1 folds are used to train the model. This cycle continues until every fold has served as the validation set exactly once. After all K runs are complete, the performance scores from each round are averaged to give a single, more stable estimate. For the work reported here, K was set to five, so each model went through five training-evaluation pairs using different data splits. Using this approach reduces the risk of overfitting to a particular train-test split, balances any bias introduced by limited or uneven data, and ultimately offers a clearer picture of how the model will behave in real-world situations.

Table 5 gives a side-by-side look at how four fine-tuned machine-learning models (NOMPS, QML, EAIQSV, and AIPSR) performed when tested with 5-fold cross-validation, while Fig. 14 puts the numbers in a chart that shows their scores through R2 (ScoreR2), root mean squared error (ScoreRMSE), and variance accounted for (ScoreVAF). To make sense of the results, we turned each metric into a rank for every fold, added the scores together, and got a single ranking score, where a higher value means better overall accuracy. Out of all the models, AIPSR (the AutoML model built with TPOT), scored best with a ranking score of 59. It posted strong, near-identical R2 figures around 0.88, kept RMSE down to about 0.73 mm, and explained roughly %93 of the variance, proof that its predictions were both precise and reliable. In the stacked bars shown in Fig. 14, AIPSR consistently maintained the highest scores across all folds, demonstrating exceptional robustness and a strong ability to generalize to unseen data.

In contrast, the QML model sits at the bottom with a ranking score of 15. Its mean R2 around 0.656, RMSE near 1.02 mm, and mean VAF of just 0.77 point to that shortfall. Those numbers tell us that, the quantum-edge design either has too few trainable parameters or has not yet been tuned to a deeper learning curve. Figure 14 visually confirms QML’s limited effectiveness, as the total bar heights and individual score contributions are consistently the lowest across folds.

NOMPS achieves a ranking score of 33, placing it in an intermediate position. It demonstrates solid but not superior R² values (mean ≈ 0.732), moderate RMSE (mean ≈ 0.896 mm), and relatively strong VAF (mean ≈ 0.834). Its scores reflect a balanced performance, likely benefiting from its physics-informed operator learning approach that captures spatial-temporal relationships but may still lack the fine granularity of ensemble optimization like AIPSR.

EAIQSV sits in third place, earning a ranking score of 41. It boasts a solid R2 value that averages around 0.754, a VAF of about 0.846, and an RMSE of roughly 0.79 mm. Remarkably, this performance comes from a straightforward neural net called SimpleNet. The model leans on SHAP, a well-known explainability tool, which helps users understand individual predictions without adding much overhead.

In summary, AIPSR offers the best performance, with high consistency and accuracy, suitable for deployment in critical decision-making scenarios. EAIQSV provides a good balance between prediction and interpretability, making it suitable for applications where transparency is essential. NOMPS demonstrates reliable performance, likely due to its ability to encode domain knowledge, though not as optimized as AIPSR. QML, while innovative, currently lags in practical predictive capability and may benefit from deeper quantum circuit design or data-driven enhancements. These findings not only confirm the superiority of AutoML approaches like AIPSR in handling complex regression problems but also highlight the importance of model interpretability (EAIQSV) and emerging quantum techniques (QML) in advancing material degradation modeling.

It is vital to compare new models with existing machine learning frameworks for accuracy in predicting carbonation depth in concrete to ensure scientific rigor. The Taylor diagram is an efficient visualization for model evaluation as it illustrates standard deviation, correlation, and centered root mean square error simultaneously. Researchers can evaluate each model’s predictions against the observed data from multiple angles beyond just accuracy. Such rigorous analysis validates claims of enhanced predictive capability. This study reports the results from four optimized models used in this study (AIPSR, EAIQSV, NOMPS, QML) and compares them to seven widely used machine learning models from previous research including multilayer perceptron (MLP), SVR, Gaussian process regression (GPR), extreme gradient boosting regression (XGBR), ANN, decision tree regression (DTR), and random forest regression (RFR). All these models underwent hyperparameter optimization with Optuna, ensuring they were assessed at their best configurational settings. In addition, a consistent method for partitioning the dataset was applied: 80% of data for training and 20% for testing. This guarantees fairness and validity for all the comparisons made.

The Taylor plot (Fig. 15) provides a comprehensive assessment of the model performance by comparing the model predictions well with the reference data (indicated by the black star). Among all the models, AIPSR stands out as the most accurate model, which is closest to the reference point. This closeness is explained by the superior correlation coefficient of 0.83 and the standard deviation very close to the observed data, thus demonstrating the excellent ability of AIPSR to capture the trend and variability of carbonation depth. These results highlight the stability, robustness and accuracy of AIPSR in reproducing the variance of the real data, making it the best model in this study. In contrast, models such as EAIQSV, NOMPS and QML fall in the middle region of the plot, with correlation coefficients between 0.69 and 0.77 and higher standard deviations. Although they show reasonable predictive power, their ability to fit observed data is not as good as AIPSR, indicating that their performance, while respectable, is less refined.

Classical machine learning models such as MLP, SVR, and DTR exhibit significant dispersion from the reference point, with higher standard deviations and lower correlation coefficients. This suggests that they struggle to generalize well to unobserved data, especially in capturing the complex and nonlinear relationships inherent in carbonation behavior. While models such as GPR and RFR outperform these classical models, they still lag behind the remarkable performance of AIPSR.

AIPSR’s dominance in the Taylor series not only reflects its superior predictive accuracy, but also its ability to capture complex interactions between features that other models are unable to capture. The Optuna-optimized architecture underlying AIPSR is key to its exceptional performance. The system’s ability to integrate machine learning (AutoML), along with evolutionary search and optimal feature engineering, allows it to adapt and refine the model in real time, capturing carbonation depth nonlinearities with unparalleled accuracy. The excellent fit of AIPSR to the reference point confirms its ability to efficiently handle complex physical systems.

Therefore, the outstanding performance of the AIPSR model in terms of accuracy, stability, and interpretability highlights its potential as a reliable predictive tool for estimating carbonation depth in concrete structures. Its closeness to the ideal position on the Taylor series diagram highlights its remarkable generalizability, a critical factor for civil engineering applications where accurate carbonation depth predictions are essential for assessing concrete durability and managing the life cycle of infrastructure. Ultimately, the advantage of AIPSR over classical and advanced models lies in its automated pipeline, which enables efficient feature selection, model optimization, and accurate fitting to complex datasets, making AIPSR a powerful tool for future research on material degradation.

Uncertainty quantification