Abstract

High-resolution cyclostratigraphic and sequence stratigraphic analyses are often compromised and lead to incorrect interpretations due to the unavailability or critical, proven errors in the reference Gamma-Ray (GR) and Density (RHOB) logs in hydrocarbon wells. This issue creates operational risks, delays, and costly re-logging procedures, directly impacting reservoir modeling and development decisions. This study presents an innovative, multi-Proxy methodology to address this critical problem by assessing the capability of the Sonic (DT), Neutron (NPHI), and Resistivity (RT) logs as reliable substitutes. The research focuses on three wells (A, B, and C) in the Oligocene to Miocene Asmari Formation of the Dezful Embayment, Southwest Iran. Available logs were analyzed to delineate third- and fourth-order sedimentary sequences based on Inflection Points. Subsequently, several advanced, distinct methods were used for comprehensive validation and the study of astronomical cycles: Spectral Analysis (SA) and Evolutionary Spectral Analysis (ESA) to isolate the influential Milankovitch cycles; Correlation Coefficient (COCO) and Evolutionary Correlation Coefficient (eCOCO) analysis to determine the Sediment Accumulation Rate (SAR); Wavelet Transform Scalogram analysis to identify intense frequency variations and interpret corresponding lithological changes; and Lag-1 Autocorrelation Coefficient (ρ1) to examine sedimentary noise and determine global sea-level trends. The outputs of the substitute logs were compared with the results of the reference GR and RHOB logs to establish their validity. The results strongly confirm the utility of the multi-proxy substitute logs. The DT and NPHI logs demonstrated a high degree of correlation across all analytical methods and reliably identified the third-order sequences. However, the RT log exhibited greater variability, particularly in high-frequency cyclicity (fourth-order) and SAR calculation, which underscores the necessity of a multi-proxy approach. This validated, multi-proxy methodology offers a definitive, cost-effective, and rapid solution for accurate stratigraphic analysis and reservoir characterization in data-scarce or error-prone environments. It allows the petroleum industry to make reliable geological and engineering decisions in the very early stages of interpretation, significantly enhancing informational certainty for exploration and development projects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cyclostratigraphy and sequence stratigraphy are vital for understanding the complex evolution of hydrocarbon reservoirs because they establish a reliable time-stratigraphic framework and map reservoir geometries. These analyses primarily depend on continuous, high-quality reference logs, such as the GR and the RHOB log. However, due to logging tool failure, poor borehole conditions, or operational limits, these reference logs are often unavailable or contain significant errors and data gaps in certain wells. The absence or inaccuracy of these main logs leads to errors in data-driven stratigraphic analyses (such as this study). Unverifiable primary data compromises the identification of sedimentary sequences and the analysis of astronomical cycles, both essential for understanding reservoir geology and well performance. This problem directly impacts Zonation, well correlation, and the accuracy of models. Re-running the logging process to fix these issues and obtain new, high-quality GR and RHOB data is costly, time-consuming, and operationally risky, often leading to incorrect calibration, drilling stoppage, and major financial loss. Therefore, the main challenge in data-scarce scenarios is finding reliable and cost-effective substitutes that can maintain the integrity of cyclostratigraphic and sequence stratigraphic interpretations.

A vast body of research continually advances sequence stratigraphy and cyclostratigraphy methods. Past studies have successfully used cyclostratigraphy to analyze influential Milankovitch cycles1,2,3,4,5, calculate SAR6,7,8,9,10, and apply advanced techniques like Wavelet11,12,13,14,15 and ρ1 analysis16,17,18,19 across various basins. Similarly, sequence stratigraphy has been widely used to map depositional trends through the analysis of third- and fourth-order sequences20,21,22,23,24. Critically, almost all these foundational studies rely exclusively on the GR log as the principal reference. While previous work has explored the use of a single alternative log, the rigorous, multi-proxy validation of several unconventional logs as substitutes remains a significant, unaddressed gap in the literature.

This study directly addresses the existing data gap by providing a robust, multi-proxy methodology for using fewer common logs as reliable substitutes. The primary objective is to investigate the consistency of outputs among the DT, NPHI, and RT logs and validate their ability to replace the GR and RHOB logs in cyclostratigraphic and sequence stratigraphic analyses. The key innovation lies in the multi-Proxy approach: it utilizes all three substitute logs simultaneously (which were available in all studied wells) and validating the results against several distinct advanced analytical methods (SA/ESA, COCO/eCOCO, Wavelet, ρ1, and the identification of third- and fourth-order sequences from the inflection points of each log) to ensure the highest degree of confidence. This comprehensive approach is a significant methodological advance over existing single-proxy techniques. The research focuses on three wells (A, B, and C) in the Asmari Formation (Oligocene to Miocene) of the Dezful Embayment, Southwest Iran. The resulting validated method is a fast, low-cost, and operational study that significantly reduces the need for re-logging. This approach allows the petroleum industry to make reliable geological and engineering decisions early in the interpretation process, even with incomplete data, improving well correlation and providing a clearer picture of the reservoir’s stratigraphic quality. Such a model serves as an efficient tool for quick interpretation, managing available data, and supporting real-time decisions during drilling and field development. This study addresses a critical and previously unfilled knowledge gap in cyclostratigraphic and sequence stratigraphic research: the absence of a validated, multi-proxy framework for substituting GR and RHOB logs when primary data are unavailable or unreliable. While previous studies have typically relied on a single unconventional log, none have systematically evaluated the combined performance of DT, NPHI, and RT logs across multiple advanced analytical techniques. The novelty of this work lies in its integrated multi-proxy approach, which simultaneously applies sequence boundaries, spectral analysis, SAR estimation, wavelet transforms, and noise filtering to ensure cross-method consistency and rigorous validation. This framework not only advances the scientific understanding of log-based astronomical and depositional signals, but also provides the petroleum industry with a practical, low-cost, and operationally safe alternative for accurate reservoir characterization in data-scarce scenarios, significantly reducing the need for re-logging and the associated financial and operational risks.

Geological setting

This study focuses on the Asmari Formation within the Dezful Embayment, a subzone of the Zagros Fold-Thrust Belt characterized by a northwest-southeast (NW–SE) structural trend in Southwest Iran25.

During the deposition of the Asmari Formation (Rupelian to Burdigalian), the study area was strongly influenced by active compressional and faulting phases within the Zagros Fold-Thrust Belt. These tectonic activities generated local anticlines and depressions, exerting a significant control over the distribution of carbonate and sandstone sediments. Structural highs, such as anticline cores, were typically characterized by thin, dense carbonate layers, whereas the depressions accumulated thicker and more porous sediment packages26. These local variations in thickness and porosity are consistent with the observed sequence boundaries (SB) and maximum flooding surfaces (MFS) identified from DT, NPHI, and RT logs. Furthermore, the spatial heterogeneity in lithology and layer thickness influenced the SAR calculated via COCO/eCOCO and the frequency variations detected in the Wavelet analysis. This heterogeneity explains the observed depth-dependent variations and differing behaviors of the logs across wells A, B, and C. Consequently, tectonic control not only shaped depositional and reservoir characteristics but also directly impacted the reliability and interpretation of the substitute logs in sequence stratigraphic and cyclostratigraphic analyses.

The Asmari Formation is recognized as one of Iran’s most significant and strategic carbonate hydrocarbon reservoir rocks. Stratigraphically, the formation overlies the Pabdeh Formation, which serves as its primary source rock, and is capped by the evaporitic Gachsaran Formation27. This well-defined stratigraphic framework makes the Asmari Formation particularly suitable for high-resolution sequence and cyclostratigraphic studies, especially when integrated with petrophysical data interpretations (Figs. 1 and 2).

Geographical map of Iran (Sheet No. 4, South-West Iran) illustrating key structural features at a 1:1,000,000 scale. The leftmost image shows the study area within Iran; the middle image highlights the southwestern region, focusing on the Dezful Embayment among structural zones; and the rightmost image zooms in the studies Oilfield, highlighted in green. The map was originally compiled by the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) in collaboration with the Geological Survey of Iran, and has been modified by the author for clarity and emphasis.

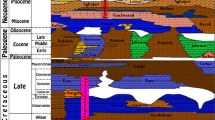

Integrated stratigraphic framework for the Iranian sector of the Zagros Basin, compiled and illustrated by the author based on multiple references. The left panel shows chronostratigraphy following the Geologic Time Scale v. 6.054,55,56,57. The middle and lower panels display the Cenozoic stratigraphy chart, illustrating lithological and facies variations across various structural zones, modified from58 and59, with interpretations from60. The right panel presents sea-level changes adapted from61. The ‘Coastal Onlaps’ column indicates relative sea-level shifts: black (< 25 m, negative), gray (25–75 m, moderate), and red (> 75 m, positive). The ‘Sea Level Change’ column shows both short- and long-term trends, referenced to present-day sea level52,53,62.

Materials and methods

Petrophysical log analysis

Petrophysical data from the three wells (A, B, and C) were analyzed using Geolog software, version 7. The lithology of these wells is composed of clastic, mixed clastic-carbonate, and carbonate rocks. To identify third- and fourth-order depositional sequences, we used the inflection points of the DT, NPHI, and RT logs. MFSs and SBs were determined based on the maxima and minima of these logs, respectively. Specifically, major inflection points were correlated with third-order sequences, while minor and secondary inflection points were used to identify fourth-order sequences, as shown in. This type of analysis is also observed in recent literature20,22,23,24,28,29.

Spectral and evolutionary spectral analysis

Astronomical cycles influencing the petrophysical data were identified using Acycle software, version 2.8. Data underwent a series of preprocessing steps, including SUE (sort/unique/empty), interpolation (0.1524 sampling rate), and detrending (mean method). The primary Milankovitch cycles—long eccentricity (405 kyr: E), short eccentricity (100 kyr: e), obliquity (41 kyr: O), and precession (20 kyr: P)—were selected for detailed analysis. The impact of each cycle was examined using the multi-taper Method (MTM) and Fast-Fourier Transform (FFT) to distinguish its spectral signature.

This method was first established by30, further developed by31,32, and finally implemented in the Acycle software by Mingsong Li and colleagues. The depth-to-time conversion in this software utilizes the Nyquist frequency formula, f_nyq = 1 / (N * \Delta t)33. Our methodology aligns with recent applications of this method2,3,5,34,35,36.

Correlation coefficient (COCO) and evolutionary correlation coefficient (eCOCO) methods

The COCO method computes a single, average SAR for the entire dataset. Statistical significance is verified using a null hypothesis test (h0), with confidence levels greater than 95% considered significant. The eCOCO method displays these parameters continuously through sequential plots.

This method was initially introduced by37. Its underlying principles were further elucidated in studies by38,39,40, which led to its inclusion in the Acycle program by41. The application of this technique is consistent with up-to-date research in the field8,9,10,42,43.

Wavelet transform scalogram analysis

Continuous wavelet transform was employed to identify the dominant and significant frequencies at each depth. Dominant frequencies are visualized in yellow and orange. A detrended plot was used to remove small, unstable frequency effects, highlighting strong, stable, and geologically meaningful signals. This method allows attributing regions of intense frequency change to corresponding lithological variations.

This methodology was first presented by44, later clarified by45, and subsequently incorporated into the Acycle software by by Mingsong Li and colleagues. Our application of this method is in line with recent literature11,12,14,46,47,48.

Noise analysis using Lag-1 autocorrelation (ρ1)

The ρ1 analysis serves as a method for removing sedimentary noise and recovering the stratigraphic signal, which can be generalized to represent sea-level trends at different depths. This facilitates a better understanding of marine transgressive and regressive patterns. The results are compared with the global sea-level curve for the Oligocene to Miocene period.

This method was first introduced by18 and its utility is demonstrated in recent studies16,17,19,49,50.

It is important to note that the specific form of the Gamma-Ray log used in this study for all subsequent time-series analyses is the Computed Gamma-Ray (CGR) log. The CGR log is preferred over the raw GR due to the necessity of environmental and drilling effects corrections, which are vital for accurate cyclostratigraphic results.

Results

Identification of third- and fourth-order depositional sequences

This analysis, based on the inflection points of the DT, NPHI, and RT logs, revealed a clear distribution of third- and fourth-order sequences across the three studied wells (A, B, and C). The findings are as follows:

Third-order sequences

Analysis of third-order sequences indicated that in Well A, the DT log identified one complete sequence, the NPHI log showed one complete and one partial sequence, and the RT log specified one partial sequence. In Well B, all three logs (DT, NPHI, and RT) consistently showed one complete and one partial sequence. In Well C, the DT log indicated two complete sequences, the NPHI log specified one complete sequence, and the RT log showed one complete and one partial sequence (Table 1).

Fourth-order sequences

In Well A, the DT log showed four complete and one partial sequence, the NPHI log revealed nine complete and one partial sequence, and the RT log identified four complete and one partial sequence. In Well B, the DT log identified three complete sequences, the NPHI log showed seven complete sequences, and the RT log revealed four complete sequences. In Well C, the DT log indicated four complete sequences, the NPHI log showed four complete and one partial sequence, and the RT log identified two complete and one partial sequence (Table 1).

Milankovitch cycle identification

The application of SA and ESA in Acycle software allowed for the identification of dominant Milankovitch cycles for each log in each well. The results are presented below, where E, e, O, and P represent the long eccentricity (405 kyr), short eccentricity (100 kyr), obliquity (41 kyr), and precession (20 kyr) cycles, respectively. The numbers reported below indicate the detected frequency of each cycle in the analyzed log data. In Well A, the DT log identified a cycle at 666.6 m for E and 63.2 m for O, with no cycles meeting the significance level for e or P. The NPHI log showed a cycle at 666.6 m for E and 75.5 m for O, with no cycles identified for e or P. The RT log identified cycles at 172.4 m for E, 43.1 m for e, 14.5 m for O, and 10.4 m for P. In Well B, the DT log identified cycles at 196 m for E and 48.4 m for e, with no cycles identified for O or P. The NPHI log showed cycles at 172.4 m for E, 12.4 m for O, and 5 m for P, with no cycle identified for e. The RT log showed cycles at 156.2 m for E, 33.5 m for e, 11.4 m for O, and 6.4 m for P. In Well C, the DT log observed a cycle at 104.1 m for E, 10.3 m for O, and 5.1 m for P, with no cycle identified for e. The NPHI log observed a cycle at 10.4 m for E, with no cycles identified for e, O, or P. The RT log observed a cycle at 109.8 m for E and 5.2 m for P, with no cycles identified for e or O (Table 1).

SAR calculation results

The SAR was calculated using the COCO and eCOCO methods. The results showed significant variability among the logs and wells: In Well A, the DT log yielded SARs of 3.8 and 16.7 cm/kyr, the NPHI log provided SARs of 1.9, 3.8, 6.5, 8.5, and 13.5 cm/kyr, and the RT log yielded a single SAR of 2.4 cm/kyr. In Well B, the DT log indicated an SAR of 3 cm/kyr, the NPHI log showed SARs of 2.8 and 12.6 cm/kyr, and the RT log yielded an SAR of 53.3 cm/kyr. In Well C, the DT log indicated an SAR of 3.5 cm/kyr, the NPHI log provided SARs of 2.4, 6.2, 8, and 10.3 cm/kyr, and the RT log yielded SARs of 8.6 and 36.8 cm/kyr. The SAR results for Wells B and C were explicitly validated, and all results across the study were found to be statistically significant by the null hypothesis (h0) test. A key finding from the eCOCO analyses is that, on average, approximately seven astronomical parameters influenced the data at various depths (Table 1).

Frequency variation analysis (Wavelet)

The Wavelet analysis was performed to identify depth intervals with significant frequency variations, which can be indicative of abrupt lithological changes. The results for each well and log are detailed as follows: In Well A, significant variations were observed in the DT log from 2470 to 2710 m, in the NPHI log from approximately 2470 to 2870 m, and in the RT log from 2640 to 2780 m. In Well B, the DT log showed significant variations from 2580 to 2820 m, the NPHI log had significant variations from 2580 to 2840 m, and the RT log showed significant variations in the specific intervals of 2640–2660 m, 2690–2710 m, 2730 m, and 2770–2870 m. In Well C, the DT log exhibited significant variations from 2580 to 2860 m, the NPHI log showed variations from 2580 to 2860 m, while the RT log had significant variations in the intervals of 2610–2640 m, 2660–2670 m, and 2750–2860 m (Table 1).

Sea-level trend and noise analysis

The ρ1 analysis was primarily used to remove sedimentary noise, but its results can also be extended to interpret relative sea-level trends (transgressions and regressions) for each log in the three wells. This approach provides a better understanding of marine transgressive and regressive patterns. The results were as follows: In Well A, the DT log indicated a regression (sea-level fall) from 2450 to 2820 m, followed by a transgression (sea-level rise) from 2820 m onwards. The NPHI log showed a regression from 2450 to 2650 m, a transgression from 2650 to 2800 m, and a subsequent regression from 2800 m onwards. The RT log showed a regression from 2550 to 2800 m, a transgression from 2800 to 2820 m, and a renewed regression from 2820 m onwards. In Well B, the DT log indicated a regression from 2570 to 2700 m, followed by a transgression from 2700 to 2880 m. The NPHI log showed a regression from 2600 to 2800 m, followed by a transgression from 2800 to 2870 m. The RT log showed a regression from 2570 to 2665 m, followed by a two-stage transgression from 2665 to 2880 m. In Well C, the DT log showed a regression from 2580 to 2650 m, followed by a two-stage transgression from 2650 to 2870 m. The NPHI log indicated a regression from 2590 to 2630 m, followed by a transgression from 2630 m onwards. The RT log showed a regression from 2580 to 2620 m, a transgression from 2620 to 2840 m, and a subsequent regression from 2840 m onwards (Table 1).

Discussion

Third- and fourth-order sequences

In this study, MFS and SB were identified by analyzing the peak and trough inflection points in the DT, NPHI, and RT logs for wells A, B, and C. Major and prominent inflection points were interpreted as third-order depositional sequences, while minor and subordinate inflection points were considered fourth-order sequences. The identified third- and fourth-order sequences are detailed as follows: In Well A, the DT log revealed one complete third-order sequence and four complete and one partial fourth-order sequence. The NPHI log delineated one complete and one partial third-order sequence, alongside nine complete and one partial fourth-order sequence. The RT log indicated one partial third-order sequence and four complete and one partial fourth-order sequence. In Well B, all three logs (DT, NPHI, and RT) consistently identified one complete and one partial third-order sequence. The logs varied in their fourth-order counts: the DT log showed three complete sequences, the NPHI log revealed seven complete sequences, and the RT log indicated four complete sequences. In Well C, the DT log revealed two complete third-order sequences and four complete fourth-order sequences. The NPHI log identified one complete third-order sequence and four complete and one partial fourth-order sequence. The RT log showed one complete and one partial third-order sequence, along with two complete and one partial fourth-order sequence.

Third-order sequences are generally linked to major tectonic events and global sea-level fluctuations over a million-year timescale (e.g., System Tracts), whereas fourth-order sequences are tied to local changes, such as glacial melting and fault activity over a thousand-year timescale (e.g., Parasequence Sets)51.

On average, the observed trend across these three logs and wells suggests a general pattern of 1 complete and 1 partial third-order sequence (1.5 sequences total), and approximately 4 complete and 1 partial fourth-order sequences (4.5 sequences total). Any significant deviation from these calculated averages is attributed to logging weaknesses or the inherently variable nature of the petrophysical logs, rather than simply data inaccuracy. This is because each log is differentially influenced by specific formation parameters:

-

The DT log is affected by factors like porosity and cementation, which are products of diagenetic processes.

-

The NPHI log is primarily influenced by the hydrogen content in the formation (i.e., fluid type, clay, and shale content).

-

The RT log is highly sensitive to the salinity and saturation degree of the formation water, in addition to porosity.

While general factors such as porosity, formation water, and rock matrix composition have a relatively uniform influence on all three logs, specific parameters like compaction, cementation (diagenesis), hydrogen content (shale/clay), and salinity/saturation exert a differential influence. The distinct effects of these varying factors are highly pronounced and visible in the analyses of this section, leading to the observed variations in sequence identification (Figs. 3, 4, 5, and Table 1).

Integrated sequence stratigraphic interpretation for Well A using DT, NPHI, and RT logs. The figure displays a layout of three petrophysical logs from Well A. The green diagrams correspond to the DT log, the blue diagrams to the NPHI log, and the red diagrams to the RT log. Third- and fourth-order depositional sequences were determined in each log based on minimum and maximum inflection points. In each diagram, the upward-pointing triangles represent the Transgressive Systems Tract (TST), while the downward-pointing triangles indicate the Highstand Systems Tract (HST). The intersection of two triangle bases marks a SB, and the intersection of two triangle vertices identifies an MFS.

Integrated sequence stratigraphic interpretation for Well B using DT, NPHI, and RT logs. The figure displays a layout of three petrophysical logs from Well B. The green diagrams correspond to the DT log, the blue diagrams to the NPHI log, and the red diagrams to the RT log. Third- and fourth-order depositional sequences were determined in each log based on minimum and maximum inflection points. In each diagram, the upward-pointing triangles represent the Transgressive Systems Tract (TST), while the downward-pointing triangles indicate the Highstand Systems Tract (HST). The intersection of two triangle bases marks a SB, and the intersection of two triangle vertices identifies an MFS.

Integrated sequence stratigraphic interpretation for Well C using DT, NPHI, and RT logs. The figure displays a layout of three petrophysical logs from Well C. The green diagrams correspond to the DT log, the blue diagrams to the NPHI log, and the red diagrams to the RT log. Third- and fourth-order depositional sequences were determined in each log based on minimum and maximum inflection points. In each diagram, the upward-pointing triangles represent the Transgressive Systems Tract (TST), while the downward-pointing triangles indicate the Highstand Systems Tract (HST). The intersection of two triangle bases marks a SB, and the intersection of two triangle vertices identifies an MFS.

The average number calculated for the third-order sequences (i.e., 1.5) is exactly similar to the number observable from the CGR log output in Well B (as shown in Fig. 6). However, the average number assigned to the fourth-order sequences (i.e., 4.5) shows no similarity to the numbers observable from the CGR log output in any of the wells. This difference is directly attributed to the differential influence of the substitute logs (DT, NPHI, and RT) from the sedimentary environment, as detailed previously. It appears that the substitute logs are more accurate in describing third-order sequences than fourth-order sequences.

Outputs of the sequence stratigraphic interpretation for the reference logs (CGR and RHOB) across three panels. The figure is organized into three main panels: the First Panel corresponds to Well A, the Second Panel to Well B, and the Third (Final) Panel to Well C. Within each panel, the first column indicates depth variations; the second column displays the behavior of the reference logs, where the CGR curve is shown in black and the RHOB curve is shown in red. Additionally, the CGR track’s left side is shaded gray to indicate the Shale Line; the third and fourth columns show the third- and fourth-order sedimentary sequences, respectively, based on their inflection points; and the final column defines the boundary of each sequence.

Milankovitch astronomical cycles

Milankovitch astronomical cycles were identified using the multi-Taper method in SA and the FFT method in ESA. The results are summarized as follows: In Well A, the DT log showed 1E, 0e, 1O, and 0P cycles; the NPHI log identified 1E, 0e, 1O, and 0P cycles; and the RT log showed 1E, 1e, 1O, and 1P cycles. In Well B, the DT log indicated 1E, 1e, 0O, and 0P cycles; the NPHI log identified 1E, 0e, 1O, and 1P cycles; and the RT log showed 1E, 1e, 1O, and 1P cycles. In Well C, the DT log showed 1E, 0e, 1O, and 1P cycles; the NPHI log identified 1E, 0e, 0O, and 0P cycles; and the RT log showed 1E, 0e, 0O, and 1P cycles. The analysis clearly demonstrates that the long eccentricity (E) astronomical cycle consistently influenced all data sets. Conversely, the short eccentricity (e) cycle did not consistently meet the required threshold of accuracy and significance. Its sporadic presence suggests that the absence of its consistent influence can be generally confirmed, indicating a negligible overall impact on the data. The influence of the obliquity (O) and precession (P) cycles is characterized by instability, as they are not observed across all logs or wells. However, their repeated identification in multiple instances confirms their presence and probable influence on the sedimentary record.

In summary, the long eccentricity cycle is definitively a primary control factor on the data, while the short eccentricity cycle is likely not influential. The influence of the obliquity and precession cycles is considered probable based on their observable occurrence (Fig. 7 and Table 1).

Results of the SA and ESA analyses for three wells (A, B, and C). The figure displays the outputs for nine panels, organized by well and log type: Panels (a–c) correspond to Well A, (d–f) to Well B, and (g–i) to Well C. Within each well’s set of plots, the results are shown sequentially for the DT, NPHI, and RT logs. Each sub-panel is divided into two sections. The Top Section displays the results of the SA, where all identified Milankovitch cycles are plotted by their depth location in meters and are color-coded as follows: Dark Blue for the E ∼405 kyr, Light Blue for the e ∼100 kyr, Green for the O ∼41 kyr, and Red for the P ∼20 kyr. The Lower Section presents the results of the ESA, showing only the influential Milankovitch cycles. The yellow-shaded areas indicate regions of highest influence and significance.

A comparison of the results derived from these methods with the outputs of the CGR and RHOB logs reveals the strong correlation and viability of the substitute logs:

-

The DT and NPHI logs in Well A exhibit behavior exactly analogous to the RHOB log in Well A.

-

The RT log in Wells A and B demonstrates similar behavior to the CGR log in Well C.

-

The DT log in Well B is exactly analogous to the behavior of the RHOB log in the same well.

-

The NPHI log in Well B and the DT log in Well C are exactly analogous to the behavior of the CGR log in Well A, with the only difference being that the counts for the obliquity (O) and precession (P) cycles are not identical, although their presence is demonstrably similar.

-

The behavior of the NPHI and RT logs in Well C does not show similarity to any of the reference logs.

It is necessary to acknowledge that the CGR log, used as the primary basis for comparison in this study, suffers from deficiencies in data recording and measurement error; consequently, the RHOB log has been utilized as a complementary witness log to complete the reference data.

Collectively, these comparisons suggest that the DT log tends to show behavior similar to the RHOB log, while the RT log exhibits behavior similar to the CGR log. What is universally generalizable across all substitute logs (and is also observable in the CGR and RHOB outputs (Fig. 10)) is the certain influence of the long eccentricity cycle on all data. Conversely, the behavior of the short eccentricity cycle ranges from less probable to rare. The presence of both the obliquity and precession cycles is considered probable to definite. What is clear is that although the substitute logs are not an exact match for the reference logs (CGR and RHOB), they clearly track the same overall trends and are highly reliable and trustworthy. It is also evident that the impact of sedimentary noise and the failure of certain cycles to meet the threshold of accuracy are inherently reflected in our observations.

Sediment accumulation rate (SAR)

The SAR was calculated using the COCO and eCOCO methods, along with the Laskar algorithms38,39 and 2000 Monte Carlo simulations. The results for the individual logs and wells are detailed as follows: In Well A, the DT log yielded SARs of 3.8 and 16.7 cm/kyr; the NPHI log provided SARs of 1.9, 3.8, 6.5, 8.5, and 13.5 cm/kyr; and the RT log yielded an SAR of 2.4 cm/kyr. In Well B, the DT log indicated an SAR of 3 cm/kyr; the NPHI log showed SARs of 2.8 and 12.6 cm/kyr; and the RT log yielded an SAR of 53.3 cm/kyr. In Well C, the DT log indicated an SAR of 3.5 cm/kyr; the NPHI log provided SARs of 2.4, 6.2, 8, and 10.3 cm/kyr; and the RT log yielded SARs of 8.6 and 36.8 cm/kyr. All of the SAR values listed above were validated by the null hypothesis (H0), confirming their accuracy and reliability at a 95% confidence level.

The average SAR across the three wells typically falls within the range of 2 to 20 cm/kyr. While other reading values may be correct at a specific local depth, they cannot be generalized to represent the entire well log sequences.

Crucially, the significant variations in SAR, such as the outlier value of 53.3 cm/kyr in the RT log of Well B, should not be dismissed as mere data recording errors, but rather reflect localized geological controls. High SAR values are geologically indicative of periods of rapid sediment accommodation and deposition, typically associated with intense clastic input (sandstone/shale) or specific seismic/mass transport events, which locally increase the sedimentation flux. Conversely, low SAR values (e.g., 1.9 cm/kyr) often denote condensed sections (e.g., MFS) or intervals with strong diagenetic overprint (cementation, dolomitization) where mechanical compaction reduces the apparent accumulation rate. These localized changes are a direct consequence of the cyclical alternation between the clastic and carbonate components of the Asmari Formation, which is the primary driver of lithological and petrophysical heterogeneity in the study area.

The eCOCO analysis indicated that up to seven astronomical parameters influenced the calculated SAR, with an overall average SAR of approximately 10 cm/kyr in most depths. Based on this observation, the NPHI log appears to have demonstrated superior performance in capturing these subtle variations.

Values falling outside the typical range (e.g., 0 or 100 cm/kyr) are most likely attributable to data recording errors and should be disregarded for the purpose of establishing a regional trend (Fig. 8 and Table 1).

COCO and eCOCO analysis results from three wells (A, B, and C) using different petrophysical logs. The figure displays the outputs for nine panels, organized by well and log type. Panels (a–c) correspond to Well A, (d–f) to Well B, and (g–i) to Well C. Within each well’s set of panels, results are shown sequentially for the DT, NPHI, and RT logs. The COCO method output includes the average SAR and the confirmation of the null hypothesis (h0), along with the average number of high-accuracy, effective astronomical parameters. The eCOCO plot shows the variation of these three dominant trends, where the yellow-shaded areas represent regions of highest confidence and strongest astronomical influence for the SAR value at each depth. An average rate of 10 cm/kyr for the SAR has been assigned to each eCOCO plot.

A review of the reference logs, CGR and RHOB, in Fig. 10 reveals that the calculated average value of approximately 10 cm/kyr is precisely observable within the trends of these logs as well. This demonstrates a very high correlation between the SAR derived from the substitute logs (DT, NPHI, and RT) and that derived from the reference logs (CGR and RHOB). Consequently, the substitute logs accurately reflect the SAR trends of the reference logs. Although certain specific depths in all logs and wells exhibit isolated SAR values outside the stated range (which are not generalizable to the entire sequence) the overall, generalizable limit of approximately 10 cm/kyr is consistently validated as the correct rate.

Wavelet analysis

Wavelet Analysis was performed to identify significant frequency variations within the well logs. The results detailing the depth intervals where these variations were observed are as follows: In Well A, the DT log showed significant variations at a depth of 2470–2710 m, the NPHI log at 2470–2870 m, and the RT log at 2640–2780 m. In Well B, the DT log showed significant variations at a depth of 2580–2820 m, the NPHI log at 2580–2840 m, and the RT log across multiple intervals: 2640–2660 m, 2690–2710 m, 2730 m, and 2770–2870 m. In Well C, the DT log showed significant variations at a depth of 2580–2860 m, the NPHI log at 2580–2860 m, and the RT log across multiple intervals: 2610–2640 m, 2660–2670 m, and 2750–2860 m. All the depth intervals identified in this analysis are consistently observed and confirmed in the detrended plot, which serves as an auxiliary diagnostic tool alongside the main wavelet plot. On average, the frequency variations are continuous and pervasive throughout the entire principal logging interval; in other words, the majority of the depth sections in both the wavelet and detrended plots exhibit intense frequency changes.

As established in wavelet studies, depths with the maximum oscillation magnitude are attributable to lithological changes. The intense and pervasive frequency variation observed across all analyzed logs is a direct manifestation of the pronounced petrophysical heterogeneity within the Asmari Formation. This heterogeneity stems from the constant, cyclic alternation between clastic sandstone and carbonate-dolomite lithologies, which are further complicated by strong diagenetic overprints. These diagenetic processes, such particularly cementation and dissolution, create sharp, high-frequency contrasts in log readings (especially in DT and NPHI) that generate the observed powerful wavelet signals. This interpretation strongly links the high-frequency cyclicity derived from the wavelet analysis to underlying lithological and diagenetic controls, validating the geological significance of the spectral output (Fig. 9 and Table 1).

ρ₁ and Wavelet analyses results from three wells (A, B, and C). The figure displays the outputs for nine sub-panels (a–i), organized by well and log type. Panels (a–c) correspond to Well A, (d–f) to Well B, and (g–i) to Well C, with the results for the DT, NPHI, and RT logs, respectively. Each sub-panel consists of three plots. The top plot illustrates sea-level changes derived from the ρ₁ method, where a decreasing trend indicates a regressive sea-level fall and an increasing trend suggests a transgressive sea-level rise. The middle plot shows the detrended time series, and the bottom plot presents the continuous wavelet transform results. In the wavelet plots, the yellow-shaded areas indicate the regions of highest frequency changes and strongest periodic signals.

By examining the wavelet plot for the reference logs, CGR and RHOB, in Fig. 10, we observe that in Well A and Well B, the maximum magnitude of frequency changes is seen approximately from the top of the logs to the 2700–2800 m depth interval. This peak magnitude is also observable in the CGR log of Well C, but the RHOB log in this well exhibits maximum variation throughout all depths.

Outputs of cyclostratigraphic analyses of the reference logs (CGR and RHOB). The figure organizes the comprehensive results of the reference logs for three wells (A, B, and C) into three main panels. The First Panel displays the outputs of the SA and ESA analyses; the Second Panel shows the outputs of the COCO and eCOCO analyses; and the Third (Final) Panel includes the outputs of the ρ1, DETREDNDED LOG, and WAVELET analyses. Six sub-panels are contained within each of these main panels: sub-panels A and B belong to Well A, sub-panels C and D belong to Well B, and sub-panels E and F belong to Well C. Furthermore, the sub-panels (A, C, and E) display the results related to the CGR log, while the sub-panels (B, D, and F) show the results related to the RHOB log.

A comparative observation with the substitute logs is possible, provided we disregard the highly variable behavior of the RT log (likely due to its logarithmic recording nature) and the measurement errors present in the CGR log of Well B:

-

The DT log generally follows the behavior of the reference logs (i.e., maximum variation from the top to the middle, roughly 2700–2800 m), accurately showing the magnitude and precise details of the frequency changes.

-

The NPHI log exhibits maximum frequency variations across almost all depths, similar to the RHOB log in Well C.

From these observations, we deduce that nearly all logs exhibit maximum frequency variations across all depths. Specifically, the DT log displays a behavior highly similar to the reference logs and can therefore be reliably used as a substitute. The NPHI log also shows acceptable performance and provides awareness of the general trend of changes, though it may lack complete accuracy and full detail. Conversely, the RT log, due to its inherent logarithmic nature, is not effective or reliable in these specific wavelet analyses.

The Lag-1 autocorrelation (ρ1) analysis

The ρ1 analysis was primarily employed to remove sedimentary noise from the data. While not a direct sea-level indicator, the ρ1 method effectively clarifies noise registration shifts across various depths and, most importantly, its general trends (ascents and descents) align with relative sea-level changes (transgressions and regressions). This method provides a better understanding of marine transgressive and regressive patterns. The sea-level trend results for the three wells are as follows: In Well A, the DT log indicated a regression (sea-level fall) from 2450 to 2820 m, followed by a transgression (sea-level rise) from 2820 m onwards. The NPHI log showed a regression from 2450 to 2650 m, a transgression from 2650 to 2800 m, and a subsequent regression from 2800 m onwards. The RT log showed a regression from 2550 to 2800 m, a transgression from 2800 to 2820 m, and a renewed regression from 2820 m onwards. In Well B, the DT log indicated a regression from 2570 to 2700 m, followed by a transgression from 2700 to 2880 m. The NPHI log showed a regression from 2600 to 2800 m, followed by a transgression from 2800 to 2870 m. The RT log showed a regression from 2570 to 2665 m, followed by a two-stage transgression from 2665 to 2880 m. In Well C, the DT log showed a regression from 2580 to 2650 m, followed by a two-stage transgression from 2650 to 2870 m. The NPHI log indicated a regression from 2590 to 2630 m, followed by a transgression from 2630 m onwards. The RT log showed a regression from 2580 to 2620 m, a transgression from 2620 to 2840 m, and a subsequent regression from 2840 m onwards.

A comparison of the ρ1 results across the DT, NPHI, and RT logs indicates a high degree of consistency and correlation. This confirms the reliability of these logs for identifying sea-level trends, even when used as alternative methods.

These findings are consistent with the global sea-level trend documented for the Oligocene to Miocene (Rupelian to Burdigalian), as confirmed by52,53 (Fig. 2). The overall regional sea-level change observed in this study is characterized by an initial regression followed by a transgression, although other local trends are present but cannot be generalized across the entire study area. It is important to note that the initial and final behaviors of all analysis plots are disregarded due to edge effects (i.e., the lack of prior or subsequent data).

The observed sea-level trends strongly correlate with the lithological changes and reservoir quality:

-

Pre-2700 m Interval (Regression): This interval, which is dominated by a regressive trend, corresponds to a carbonated and dolomitic environment. While reservoir presence is confirmed, the reservoired volume is not significant or noteworthy based on petrophysical analysis (Fig. 9 and Table 1).

-

Post-2700 m Interval (Transgression): The depth interval from 2700 m to the end of the logs shows a prevalent transgressive sea-level trend. This section is characterized by clastic sandstone (predominantly quartz), which, upon visual inspection of the U.oil column in the corresponding lithology diagram (Fig. 11), is revealed to be a high-quality reservoir with excellent hydrocarbon content.

Lithology diagrams versus depth for three wells (A, B, and C). In all three panels, the first column displays depth. The second column illustrates the dominant lithological changes throughout the depth, with the following color coding: YELLOW for Quartz, MAGENTA for Dolomite, CYAN for Calcite, and BROWN for Anhydrite. The four subsequent columns present the separate volumes of each of these four lithologies, showing the detailed rock composition at every depth. The final three columns—U.GAS, U.OIL, and U.WATER—indicate the potential and relative volume of the reservoir fluids (gas, oil, and water) as a function of depth. It is important to note that Well B lacks the three fluid potential columns.

Although this high-quality reservoir is not immediately apparent in Well B, the analysis of the three logs suggests that the log behaviors are fundamentally similar in this critical interval. Therefore, based on this interpretation, the interval from 2700 m to the bottom of the logs is considered a suitable location for future drilling operations.

By observing the behavior of the reference plots, CGR and RHOB, in its figure, it is clear that the 2700 m depth serves as a key reference horizon. The trend of initial noise reduction (or, more accurately, the initial regression followed by sea-level transgression) is precisely captured in these reference plots. This establishes an unprecedented convergence, correlation, and match between the substitute logs and the reference logs. Consequently, any of the substitute logs can be expected to yield results exactly similar to those of the reference logs in this analysis.

Although this high-quality reservoir is not immediately apparent in Well B, the analysis of the three logs suggests that the log behaviors are fundamentally similar in this critical interval.

Conclusion

This study successfully evaluated the efficacy of alternative petrophysical logs (DT, NPHI, and RT) as substitutes for the GR and RHOB logs in the Oligocene to Miocene Asmari Formation of Southwest Iran. The primary objective was to assess the reliability and internal correlation of these substitute logs for both sequence stratigraphic and cyclostratigraphic analyses in wells where primary data are compromised or unavailable. This work also clarifies an important gap in current stratigraphic practice, because a comprehensive and validated framework for evaluating multiple unconventional logs in the absence of reliable GR and RHOB data was previously lacking. By examining the combined performance of DT, NPHI, and RT logs through a wide suite of analytical approaches, including sequence-boundary identification, spectral analysis (SA and ESA), SAR estimation (COCO and eCOCO), wavelet, and noise filtering using the ρ1 method, the study develops a coherent and cross-validated methodology that strengthens confidence in log-based interpretations. In addition to the scientific contribution, the integrated multi-proxy approach provides a practical benefit for the petroleum industry by reducing the need for costly re-logging operations and lowering operational and financial risks during early-stage reservoir evaluation.

The findings from the sequence stratigraphic analysis, which used inflection points to identify sedimentary sequences, showed a significant overall convergence among the logs, with results consistently indicating an average of 1.5 third-order and 4.5 fourth-order sequences. From a cyclostratigraphic perspective, the combined SA and ESA methods confirmed that the long eccentricity cycle is the primary control factor, while the short eccentricity cycle demonstrated negligible influence. The COCO and eCOCO methods further validated this consistency, estimating the general average SAR to be approximately 10 cm/kyr with a strong common trend across all logs. Wavelet analysis revealed continuous and severe frequency changes across the interval, interpreted as a direct result of the cyclic alternation between clastic and carbonate-dolomite lithologies and localized diagenetic events. The lag-1 autocorrelation method also revealed clear sea-level trends characterized by an initial regression followed by a transgression, and these trends showed a very high degree of consistency with established global sea-level curves. Altogether, the results strongly support the viability of the DT, NPHI, and RT logs as scientifically robust and trustworthy substitutes for the GR and RHOB logs in cyclostratigraphic and sequence stratigraphic studies where primary data are limited. This research provides a distinctive and valuable perspective for interpreting hydrocarbon reservoirs and offers a pathway to reducing operational risks and costs by supporting more reliable decisions in exploration, drilling, reservoir modeling, and Enhanced Oil Recovery projects. Despite the strong internal consistency, a primary limitation of this study was the absence of complementary stratigraphic data such as isotope analyses, elemental analyses, and micropetrographic observations that are essential for external validation. Incorporating such datasets in future research will be crucial for achieving a more comprehensive and precise chronostratigraphic framework for the Asmari Formation and similar reservoirs.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DT:

-

Sonic log

- NPHI:

-

Neutron log

- RT:

-

Resistivity log

- GR:

-

Gamma-ray log

- RHOB:

-

Density log

- SA:

-

Spectral analysis

- ESA:

-

Evolutionary spectral analysis

- COCO:

-

Correlation coefficient

- eCOCO:

-

Evolutionary correlation coefficient

- SAR:

-

Sediment accumulation rate

- CM/KYR:

-

Centimeter per thousand years

- ρ1:

-

Lag-1 autocorrelation

- E:

-

Long eccentricity

- e:

-

Short eccentricity

- O:

-

Obliquity

- P:

-

Precession

- SB:

-

Sequence boundary

- MFS:

-

Maximum flooding surface

References

Fang, Q. et al. Trends and rhythms in climate change during the early permian icehouse. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 36, e2021PA004340 (2021).

Mohamed, H., Mabrouk, W. M. & Metwally, A. Delineation of the reservoir petrophysical parameters from well logs validated by the core samples case study Sitra field, Western Desert. Egypt. Sci. Rep. 14, 26841 (2024).

Munther, A. & Sahaab, A. M. Well logs analysis and reservoir evaluation of Hartha formation in the East Baghdad oil field central Iraq. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1300, 012028 (2024).

Shi, M. et al. Middle miocene-pleistocene magneto-cyclostratigraphy from IODP Site U1501 in the Northern South China sea. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 882617 (2022).

Tang, Y. et al. The floating astronomical time scale for the terrestrial Early Permian Fengcheng Formation from the Junggar Basin and its stratigraphic and palaeoclimate implications. Geol. J. 57, 4842–4856 (2022).

Cheng, D. et al. An astronomically calibrated stratigraphy of the Mesoproterozoic Hongshuizhuang Formation, North China: Implications for pre-Phanerozoic changes in Milankovitch orbital parameters. J. Asian Earth Sci. 199, 104408 (2020).

Gong, Z. Cyclostratigraphy of the Cryogenian Fiq Formation, Oman and its implications for the age of the Marinoan glaciation. Glob. Planet. Change 204, 103584 (2021).

Ramos, J. M. F. et al. Orbital tuning of short reversed geomagnetic polarity intervals in the cretaceous normal polarity superchron. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL110530 (2024).

Tang, Y. et al. Cyclostratigraphy of lower permian alkaline lacustrine deposits in the Mahu Sag, Junggar basin and its stratigraphic implication. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1232418 (2023).

Wichern, N. M. A. et al. Astronomically paced climate and carbon cycle feedbacks in the lead-up to the Late Devonian Kellwasser Crisis. Clim. Past 20, 415–448 (2024).

Chu, R. et al. Orbital eccentricity and internal feedbacks drove the Triassic megamonsoon variability. Sci. Rep. 15, 24190 (2025).

Liang, J. et al. Astronomical chronology framework of the Lingshui Formation (Oligocene) in the Northern South China Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 13, 86 (2025).

Omar, H., Da Silva, A.-C. & Yaich, C. Linking the variation of sediment accumulation rate to short term sea-level change using Cyclostratigraphy: Case study of the lower Berriasian Hemipelagic sediments in central Tunisia (Southern Tethys). Front. Earth Sci. 9, 638441 (2021).

Ren, C. et al. Cyclostratigraphic correlation of Middle-Late Ordovician sedimentary successions between the South China Block and Tarim Basin with paleoclimatic and geochronological implications. J. Asian Earth Sci. 246, 105577 (2023).

Wang, X., Zhang, X., Gao, F. & Zhang, M. Astronomical cycles of the late permian Lopingian in South China and their implications for third-order sea-level change. J. Ocean Univ. China 19, 1331–1344 (2020).

Dong, Y. et al. Orbital cycle records in shallow unconsolidated sediments: Implications for global carbon cycle and hydrate system evolution in deep-sea area sediments of the Qiongdongnan Basin. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1525477 (2025).

Jin, S. et al. Orbital and millennial-scale cycles through the Hirnantian (Late Ordovician) in Southern China. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 25, e2023GC011127 (2024).

Li, M., Hinnov, L. A., Huang, C. & Ogg, J. G. Sedimentary noise and sea levels linked to land-ocean water exchange and obliquity forcing. Nat. Commun. 9, 1006 (2018).

Sári, K. et al. Integrated stratigraphy of an Upper Miocene lignite-bearing succession based on wireline log, seismic and organic petrographic data in the Tiszapalkonya-1 core section. NE Hungary. Int. J. Coal Geol. 307, 104825 (2025).

Cao, H. et al. Astronomical cycles calibrated the sea-level sequence durations of late Miocene to Pliocene in Qiongdongnan Basin, south China sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 143, 105813 (2022).

Falahatkhah, O., Kordi, M., Fatemi, V. & Koochi, H. H. Recognition of Milankovitch cycles during the Oligocene-Early Miocene in the Zagros Basin, SW Iran: Implications for paleoclimate and sequence stratigraphy. Sediment. Geol. 421, 105957 (2021).

Falahatkhah, O., Ghaderi, A., Kadkhodaie, A. & Rezaee, R. Milankovitch-driven terrigenous deposit influx in Middle Ordovician marine successions of Western Australia: Insights for paleoclimate and geochronology. Mar. Pet. Geol. 173, 107282 (2025).

Falahatkhah, O. & Kordi, M. Earth’s orbital control on the Albian sedimentary sequences along the southern Neo-Tethys margin. Int. J. Earth Sci. 114, 749–768 (2025).

Liu, G. et al. Cyclostratigraphy and high-frequency sedimentary cycle framework for the Late Paleozoic Fengcheng Formation. Junggar Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1206835 (2023).

Soleimani, M., Soleimani, B. & Seifi, J. Dolomitization quality, development, and its impact on oil production in the Bangestan reservoir, Ahvaz oil field [Translated title]. Adv. Appl. Geol. 9, 1–9 (2019).

Khalili, A., Vaziri-Moghaddam, H., Arian, M. & Seyrafian, A. Carbonate platform evolution of the Asmari Formation in the east of Dezful Embayment, Zagros Basin. SW Iran. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 181, 104229 (2021).

Safi, M. & Alipour-Asll, M. Geochemical characterization of the oil source rocks in the Ahwaz oilfield. Southwest Iran. Geopersia 12, 1–21 (2022).

Fragoso, D. G. C. et al. Cyclicity in Earth sciences, quo vadis? Essay on cycle concepts in geological thinking and their historical influence on stratigraphic practices. Hist. Geo- Space Sci. 13, 39–69 (2022).

Zhou, Y. & Li, Z. Terminal Ediacaran microbialite lithofacies associations with paleo-environmental constraints in a high-frequency sequence stratigraphic framework of Sichuan Basin. SW China. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1085313 (2023).

Thomson, D. J. Spectrum estimation and harmonic analysis. Proc. IEEE 70, 1055–1096 (1982).

Vaughan, S., Bailey, R. J. & Smith, D. G. Detecting cycles in stratigraphic data: Spectral analysis in the presence of red noise. Paleoceanography 26, 2011PA002195 (2011).

Weedon, G. P., Page, K. N. & Jenkyns, H. C. Cyclostratigraphy, stratigraphic gaps and the duration of the Hettangian Stage (Jurassic): Insights from the Blue Lias Formation of southern Britain. Geol. Mag. 156, 1469–1509 (2019).

Li, M., Hinnov, L. & Kump, L. Acycle: Time-series analysis software for paleoclimate research and education. Comput. Geosci. 127, 12–22 (2019).

Chen, F. & Mitchell, R. N. Is One Sample Enough? Testing the Importance of Lateral Sedimentary Variability in Cyclostratigraphy. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 26, e2024GC012087 (2025).

Feng, X.-F. et al. Cyclostratigraphy of the Middle Jurassic Aalenian Sha-1 member lacustrine record in central Sichuan Basin, southwestern China. J. Palaeogeogr. 14, 452–475 (2025).

Leu, K. et al. Cyclostratigraphy of the lower Aalenian Opalinuston Formation in the Swabian Alb deduced from downhole logging data. Z. Dtsch. Ges. Für Geowiss. 174, 53–67 (2023).

Meyers, S. R. & Sageman, B. B. Quantification of deep-time orbital forcing by average spectral misfit. Am. J. Sci. 307, 773–792 (2007).

Laskar, J. et al. A long-term numerical solution for the insolation quantities of the Earth. Astron. Astrophys. 428, 261–285 (2004).

Laskar, J., Fienga, A., Gastineau, M. & Manche, H. La2010: A new orbital solution for the long-term motion of the earth. Astron. Astrophys. 532, A89 (2011).

Waltham, D. Milankovitch Period Uncertainties and Their Impact On Cyclostratigraphy. J. Sediment. Res. 85, 990–998 (2015).

Li, M., Kump, L. R., Hinnov, L. A. & Mann, M. E. Tracking variable sedimentation rates and astronomical forcing in Phanerozoic paleoclimate proxy series with evolutionary correlation coefficients and hypothesis testing. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 501, 165–179 (2018).

Martínez-Rodríguez, R. et al. Integrated cyclostratigraphy of the Cau core (SE Spain) - A timescale for climate change during the early Aptian Anoxic Event (OAE 1a) and the late Aptian. Glob. Planet. Change 233, 104361 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Cyclostratigraphy and paleoclimate analysis of the Lingshui Formation in Changchang Sag, Qiongdongnan Basin. China. Energy Geosci. 5, 100224 (2024).

Torrence, C. & Compo, G. P. A Practical Guide to Wavelet Analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 79, 61–78 (1998).

Grinsted, A., Moore, J. C. & Jevrejeva, S. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 11, 561–566 (2004).

Arts, M., Corradini, C., Pondrelli, M., Pas, D. & Da Silva, A.-C. Age and orbital forcing in the upper Silurian Cellon section (Carnic Alps, Austria) uncovered using the WaverideR R package. Front. Earth Sci. 12, 1357751 (2024).

Vallner, Z., Haas, J. & Pálfy, J. Astronomical control on the origin and preservation of Lofer cyclicity in the Late Triassic Dachstein platform. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 680, 113365 (2025).

Walsh, C. R. et al. Late 20th Century Hypereutrophication of Northern Alberta’s Utikuma Lake. Environments 12, 63 (2025).

Sun, Z., Jiang, T., Zhu, H., Feng, X. & Wei, P. Reconstruction of Lake-Level Changes by Sedimentary Noise Modeling (Dongying Depression, Late Eocene, East China). Energies 16, 2216 (2023).

Wang, M., Li, M., Kemp, D. B., Boulila, S. & Ogg, J. G. Sedimentary noise modeling of lake-level change in the Late Triassic Newark Basin of North America. Glob. Planet. Change 208, 103706 (2022).

Zhao, Z. et al. Milankovitch cycles in the upper ordovician lianglitage formation in the Tazhong-Bachu area. Tarim Basin. Acta Geol. Sin. 84, 518–536 (2010).

Haq, B. U. & Al-Qahtani, A. M. Phanerozoic cycles of sea-level change on the Arabian platform. GeoArabia 10, 127–160 (2005).

Haq, B. U. & Shutter, S. R. A chronology of Paleozoic sea-level changes. Science 322, 64–68 (2008).

Cohen, K. M., Finney, S., & Gibbard, P. L. International Chronostratigraphic Chart. (2012).

Cohen, K. M., Finney, S. C., Gibbard, P. L., & Fan, J.-X. The ICS International Chronostratigraphic Chart. (2021).

Geological Society of America. Geologic time scale (Version 6.0). (2022).

Gradstein, F. M., Ogg, J. G., & Schmitz, M. D. The geologic time scale 2012. (2012).

Beydoun, Z. R., Clarke, M. W. H. & Stoneley, R. Petroleum in the Zagros Basin: A Late Tertiary Foreland Basin Overprinted onto the Outer Edge of a Vast Hydrocarbon-Rich Paleozoic-Mesozoic Passive-Margin Shelf. AAPG 55, 0 (1992).

Motiei, H. Stratigraphy of Zagros. In A. Hushmandzadeh (Ed.), Treatise on the Geology of Iran [Translated Title]. (Geological Survey of Iran, Tehran, Iran, 1993).

Sepehr, M. & Cosgrove, J. W. Structural framework of the Zagros Fold-Thrust Belt. Iran. Mar. Pet. Geol. 21, 829–843 (2004).

Snedden, J. W. & Liu, C. A Compilation of Phanerozoic Sea-Level Change, Coastal Onlaps, and Recommended Sequence Designations. 1–3 https://www.searchanddiscovery.com/pdfz/documents/2010/40594snedden/ndx_snedden.pdf.html (2010).

Hardenbol, J. et al. Mesozoic and Cenozoic sequence chronostratigraphic framework of European basins. In P. C. de Graciansky (Ed.). SEPM 60, 3–13 (1998).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was written by Amir Alimardanian. Revisions and editorial corrections were contributed by Ali Kodkhodaie and Mohsen Aleali. Conceptual guidance and practical expertise were provided by Mehran Arian and Davood Jahani.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alimardanian, A., Kodkhodaie, A., Aleali, M. et al. Application of porosity logs for cyclostratigraphic analysis in the absence of gamma ray logs. Sci Rep 16, 3841 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33964-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33964-x