Abstract

The persistent occurrence of rock burst phenomena during roadway excavation poses a critical safety challenge in modern underground mining operations. This research systematically investigates zonal evolution patterns of acoustic emission (AE) events, developing quantitative indicators to evaluate rock burst risks and progressive damage quantification in surrounding rocks and reveals the failure mechanisms with rock burst. The results show that the elastic strain energy in the surrounding rock instantly releases suddenly, causing the deformation and failure of the shallow damaged surrounding rock and inducing rock burst in the excavation roadway. In horizontal, the risk of rock burst increases with the increase of horizontal tectonic stress; in vertical, the risk first increases and then decreases with the increase of mining disturbance stress. Dynamic stress has a significant impact on the degree of damage to the surrounding rock and increases the possibility that rock burst. The coordinated prevention and control method of “pressure relief—load reduction - reinforcement” for roadway excavation was proposed based on the energy zoning characteristics of the roadway effectively reduces the risk of rock burst during the roadway excavation process and provides certain reference experience for the prevention and control of rock burst in roadway excavation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rock burst represents a dynamic failure phenomenon characterized by sudden ejection of coal-rock masses, occurring when accumulated elastic strain energy under high-static stress conditions undergoes rapid release triggered by mining-induced disturbances1,2,3,4,5. With the gradual depletion of shallow coal resources, resource extraction is gradually extending to deeper levels. Deep roadways situated in complex multi-physics environments (high in-situ stress, elevated geothermal temperatures, high pore pressures, and excavation disturbances) face critical challenges including large deformation and sudden failure6. In particular, the excavation roadways under complex geological conditions are prone to induce rock burst, which imposes higher requirements for the safe extraction of coal3,7. For example, multiple rock burst disasters occurred during the roadway excavation in the Liuhuanggou Coal Mine in Xinjiang, resulting in a large-scale collapse of the roadway roof8. A rock burst happened during the excavation of the No. 1 Auxiliary Haulage Main Roadway in a mine in Shaanxi, causing a maximum rib spalling of 0.5 m within a range of 30 m behind the working face and the tearing of the bolt-mesh support9. In the excavation working face of the Gaojiapu Coal Mine in Shaanxi, the sound of coal bumps was loud, the roadway deformation was obvious, and the bolts and cables were snapped10. The excavation roadway is a dead-end roadway, making it difficult to escape after a rock burst and resulting in a high fatality rate in accidents. Approximately 13,000 km of roadways are excavated annually, and accidents reported in mining roadways account for a staggering 80–90% of all coal mine accidents in China11. Therefore, the prevention and control of rock burst during the roadway excavation period has become one of the main issues for the safe production of mines12.

Reliable laboratory experiments are widely used in the study of surrounding rock failure mechanisms. Wang et al. found that with the increase in the dynamic loading input into the system, obvious damage occurred to the surrounding rock of the roadway, with some roadways showing the impact form of local floor heave and being in a semi-enclosed state13. He et al. carried out true triaxial unloading experiments, and the experimental results indicated that when the rock mass shifted from a triaxial stress state to a uniaxial stress state, a dilation phenomenon emerged in the unloading direction, and gradually increases with the augmentation of the unloading surface14. Liu et al. investigated the rheological failure characteristics of roadway-surrounding rocks utilizing an MTS rock testing system and proposed an enhanced three-dimensional creep constitutive model that effectively captures the nonlinear features inherent in rock creep stages15. Gong et al. observed symmetrical V-shaped failure patterns developing along roadway sidewalls through triaxial compression experiments on cuboid specimens containing prefabricated circular boreholes, systematically elucidates the strain rock burst failure mechanisms in roadways16. In fact, rock burst fundamentally constitutes a dynamic phenomenon inherently coupled with energy dissipation. A comprehensive understanding of this process in excavated roadways can be established through rigorous energy-based analyses2,17,18. W.J. Gale systematic investigation revealed three critical determinants of rock burst manifestation: volume of the coal mass, available energy, resistance of the coal as well as the position of the energy triggering the burst, and that when the coal mass is damaged and its cohesive strength is relatively low, small-energy mine tremors near the free face of the roadway may also trigger rock burst19.

Numerical simulation method demonstrates distinct analytical advantages in characterizing fracture propagation and energy distribution patterns within roadway surrounding rock systems. Zuo et al. study concentrates on the zonal disintegration phenomenon in the roadway longitudinal direction and the time-lag effect, finding that microcracking in the disintegration zone within the model decreases gradually from the roadway surface to the interior of the model, the volume of the disintegration zone within the model reduces as well, and the diameter of the same disintegration zone becomes larger20. Meng’s numerical modelling replicated tensile fractures and associated fragmentation and detachment in shallow roadway stress relaxation zones, demonstrating grouting-enhanced strength effectively mitigates deformation and failure21. Gao analysed the laws of elastic strain energy absorption and release during the incubation process of rock burst in the surrounding rock of coal seam roadways, and discovered the variation laws of the roadway butterfly-shaped plastic zone with the stress environment22. Zhang et al. analysed strain energy evolution in coal-rock composite samples under uniaxial compression, revealing that increasing roof strength elevates the coal’s strain energy storage limit23. Du et al. revealed that roadway rock burst originates from butterfly-shaped plastic failure in surrounding rock, demonstrating that the rock burst intensity correlates positively with the magnitude of released elastic strain energy24. While many scholars have conducted in-depth research on the failure mechanisms of roadway rock burst and the response characteristics of surrounding rock from the perspectives of rock damage and energy release, studies focusing on the conversion relationship between elastic strain energy and plastic dissipated energy as well as their influence on rock burst remain relatively scarce. Particularly, the mechanism of how excavation-induced disturbance stress affects rock burst failure mechanisms during roadway development remains unclear. This has resulted in current prevention measures for rock burst in excavation roadways being unable to effectively reduce the risk of rock burst.

This study employs a self-developed PWS-500 excavation dynamics test system to systematically characterize AE event distribution patterns associated with excavation-induced failure mechanisms under multifactor conditions. A rock burst risk index and surrounding rock damage quantification method are established for roadways. The mechanical roles of elastic strain energy and plastic dissipation energy in roadway rock burst failure processes are elucidated through numerical simulations, with energy zoning characteristics being revealed and excavation-induced failure mechanisms being clarified. Factor-specific influence patterns on excavation-induced rock burst risks are systematically investigated through field applications, along with prevention strategies developed to provide engineering control references.

Experimental methodology

Test apparatus and stress path

While current true triaxial experimental systems can effectively reveal the failure mechanisms of rock burst under various conditions, the existing experimental equipment is incapable of drilling the specimens during the experiment to simulate the disturbance caused by roadway excavation. To systematically investigate rock burst failure mechanisms in roadways under excavation disturbance, this study employing the self-developed PWS-500 excavation dynamic disaster mechanism experimental system to conduct on coal-rock samples under multi-factor conditions. This system integrates a true triaxial testing system, a roadway excavation system, and a digital control system, as shown in Fig. 1a. The core apparatus features a four-column frame structure, equipped with a vertical dynamic loading actuator capable of applying a force of 500 kN, achieving a peak transient speed of 0.8 m/s. Additionally, the system includes three horizontally arranged loading actuators, each with a capacity of 800 kN as illustrated in Fig. 1b.

The AE signals during the roadway excavation process were monitored using the PCI-2 AE system developed by Physical Acoustics Corporation. The threshold value was set to 40 dB, the sampling rate was set at 2 MSPS and the preamplifier gain was set to 40 dB. The parameters for PDT, HDT, and HLT were set to 50 µs, 200 µs, and 300 µs, respectively, ensuring real-time monitoring of energy, amplitude and counts for each event. Six RS-15 A Soft Island AE sensors were used, each with a diameter of 18.8 mm, a height of 30 mm, a central frequency of 70 kHz, and a frequency range of 40–150 kHz. These sensors were mounted in pre-reserved sensor holes of the experimental apparatus, with springs installed behind them to ensure tight contact between the AE sensors and the sample surface during the experiment, as shown in Fig. 2a. After installing the AE sensors, AE coupling agents were applied to the sensor surfaces to fully fill the gaps between the sensors and the sample to minimize energy reflection losses and reduce friction25.

The experimental procedure was as follows: (a) The specimen was placed into the testing machine and a displacement loading rate of 0.001 mm/s was applied until reaching the specified initial stress state26. (b) A constant displacement was maintained in the X, Y, and Z directions and the pressure was held for 60 s to ensure the stress within the specimen reached full equilibrium, closely replicating the field conditions. (c) A drilling machine was used on the Y-face of the specimen to simulate roadway excavation, with a drilling rate of 0.1 mm/s and a total drilling depth of 100 mm. (d) The drill rod was withdrawn, and the experiment was concluded. The loading method for the specimen was shown in Fig. 2b.

Test specimens and scheme

The test specimens were obtained from a mine in northwestern China. Prior to testing, the specimens were prepared into cubic coal-rock composite samples with dimensions of 150 mm in length, width, and height, as shown in Fig. 3. Among them, Fig. 3a–d were composed entirely of coal, while the remaining specimens were coal-rock composite samples. Specimens A-1 and A-2 were taken from depths of 600 m and 800 m, respectively, and specimen A-3 was subjected to a lateral pressure coefficient of 2 at a depth of 600 m. Specimen A-4 simulated a folded coal-rock sample at a depth of 600 m, with increased horizontal stress caused by folding. As shown in Fig. 3e,f, specimens B-1 and B-2 represented excavation along and perpendicular to the fault plane, respectively. Specimens C-1 and C-2 simulated excavation in the roof and floor of the coal seam, while specimens C-3 and C-4 represented different excavation speeds in the roadway, as shown in Fig. 3g–j. Specimens D-1 and D-2 simulated excavation in coal seams transitioning from thin to thick and from thick to thin, as shown in Fig. 3k,l. The detailed testing scheme was provided in Table 1.

Experimental sample. (a) Buried depth of 600 m. (b) Buried depth of 800 m. (c) Lateral pressure coefficient. (d) Folded structure. (e) Excavate along the fault plane. (f) Excavate vertical along the fault plane. (g) Excavate along the roof of the coal seam. (h) Excavate along the floor of the coal seam. (i) Rapid excavation of roadway. (j) Normal excavation of roadway. (k) Coal seam changes from thin to thick. (l) Coal seam changes from thick to thin.

Test results and analysis

Distribution patterns of AE events

The distribution of AE events during the experiments is shown in Fig. 4. At a burial depth of 600 m the A-1 sample exhibits fewer AE events with high energy events primarily concentrated around the roadway within the roof and floor coal seams (see Fig. 4a). As the depth increases in the A-2 sample, the in-situ stress rises, resulting in more AE events, though their distribution remains consistent, with a concentration in the roof and floor areas and fewer events along the sidewalls (see Fig. 4b). As shown in Fig. 4c, for the A-3 sample, increasing the confining pressure significantly raises the number of AE events, which are mainly concentrated in the central part of the floor seam. However, when a differential confining pressure is applied in the A-4 sample, the number of AE events decreases compared to A-3 but remains higher than A-1, with more events distributed in the roof and floor, and the floor exhibiting a broader range of events (see Fig. 4d). As shown in Fig. 4e,f, for the B-1 and B-2 samples, which simulate excavation along different fault directions, AE events are predominantly located along the fault plane, with a higher density on the coal side. When the lithology of the roof and floor differs, as in the C-1 and C-2 samples, the AE events display distinct patterns: in the “coal roof and rock floor” configuration (see Fig. 4g), low energy AE events concentrate in the roof coal seam, while in the “rock roof and coal floor” configuration (see Fig. 4h), such events are primarily found in the floor coal seam. Under different excavation speeds, the distribution patterns of AE events remain consistent between the C-3 and C-4 samples, though the faster excavation C-4 sample shows more AE events than C-3 (see Fig. 4i,j). Finally, as shown in Fig. 4k,l, for the D-1 and D-2 samples, which represent excavation from thin to thick and thick to thin sections, respectively, the number of AE events is higher when excavation progresses from a thick to thin section.

The AE counts and energy for each sample during the experiments are shown in Fig. 5. AE counts and energy are generally highest during the loading phase, are moderate during the excavation phase, and lowest during the holding phase. During excavation in normal strata, like samples at 600 m (Fig. 5a) and 800 m (Fig. 5b), AE counts and energy values are relatively low, indicating that excavation disturbance is limited and coal fracture is minor in these conditions. However, when the confining pressure (Fig. 5c,d) changes, high energy AE events occur during excavation. In particular, AE counts and energy in Sample A-3 rise significantly as excavation reaches the sample center, reaching a peak AE energy of 1.7E + 08 aJ, suggesting that an increase in lateral pressure factor intensifies energy release, raising the rock burst risk in the roadway. During excavation in faulted samples, AE counts are high while AE energy remains low, which indicates that excavation disturbances induce extensive micro - crack development along the fault plane and increase the rock burst risk in the fault area. Additionally, Sample B-2 shows higher AE counts and energy than Sample B-1, indicating greater rock burst risk when excavating along the fault plane, as shown in Fig. 5e,f. For samples with “coal roof and rock floor” and “rock roof and coal floor” configurations, low energy events are predominant, and the energy release levels are comparable in both configurations, as shown in Fig. 5g,h. Similar to Sample C-3, the maximum AE counts in Sample C-4 are around 500 during excavation; however, the AE counts in Sample C-4 reach 34,000. AE energy also varies with excavation speed: at 0.2 mm/s, the maximum AE energy reaches approximately 1.2E + 07 aJ during excavation, whereas at 0.1 mm/s, the maximum AE energy is merely about 2.0E + 06 aJ, as shown in Fig. 5i,j. When the coal seam thickness varies, AE counts and energy increase. Notably, when excavation transitions with a 10 mm change from a thick to a thin coal seam, AE counts and energy surge and maintain this elevated level, indicating that changes in coal thickness affect the rock burst risk, especially when excavation moves from thicker to thinner seams, where the risk is more pronounced, as shown in Fig. 5k,l.

Energy distribution characteristics along roadway dip orientation

In the above experimental, several experimental groups that received sufficient AE signals during the excavation process were selected. The AE event numbers, as well as the AE counts and energy, were statistically analysed at varying distances from the roadway centerline during the excavation process, as shown in Fig. 6. Due to the variation in the disturbance range of the excavation process, the AE event numbers generally increases and then decreases with increasing distance from the roadway surface, as shown in Fig. 6a. For sample A-1, influenced by self-weight stress, the maximum AE event numbers occurs at 30 ~ 40 mm from the roadway surface, which is approximately one roadway diameter in length. Sample B-1, which was excavated perpendicular to the fault plane, shows that the maximum AE event numbers occurs at 20 ~ 30 mm from the roadway surface. In contrast, for sample B-2, excavated along the fault plane, this distance is reduced to 10 ~ 20 mm, indicating that the disturbance range is smaller in roadways excavated along the fault plane compared to those excavated perpendicular to it. When the roadway roof consists of coal seams (sample C-1), AE counts fluctuate little regardless of the distance from the roadway surface, suggesting minimal variation in both the disturbance range and intensity under these conditions. However, a slight increase in AE event numbers is observed at 20 ~ 30 mm from the roadway surface, which corresponds to the position of maximum disturbance, slightly less than one roadway diameter in length. When the excavation speed is higher, a greater number of AE events is observed, indicating that as excavation speed increases, the disturbance intensity also increases. Additionally, the variation in AE event numbers with increasing distance from the roadway surface becomes more pronounced, suggesting that at higher excavation speeds, the rate of change in disturbance intensity is also higher, with the maximum disturbance occurring at approximately one roadway diameter in length. In sample D-1, a higher number of AE events is observed, and these events decrease with increasing distance from the roadway surface. This indicates that roadways excavated in the coal seam transformation zone experience higher disturbance, with the maximum disturbance occurring relatively close to the roadway surface, less than half the roadway diameter in length.

As shown in Fig. 6b,c, the region with the highest AE event numbers, corresponding to the maximum disturbance intensity, generally also exhibits higher AE counts and energy. However, unlike the pattern observed for AE event numbers, there is no clear correlation between the location of maximum AE energy and its distance from the roadway surface.

In summary, the regions with a higher AE event numbers correspond to areas where the coal-rock mass is most affected by roadway excavation disturbances, indicating a higher risk of rock burst. However, regarding the intensity of the rock burst, it is not necessarily the case that regions with higher rock burst risk also experience the greatest rock burst intensity. The intensity of the rock burst is influenced by both the properties of the coal-rock mass in the rock burst area and the conditions of the roadway after excavation. Therefore, in the prevention and control of roadway rock burst, it is essential to not only implement necessary pressure relief and hazard mitigation measures, but also to regularly inspect the quality of roadway support and the integrity of the roadway structure. Timely repairs should be made to damaged areas, and additional reinforcement should be applied to areas where the support has failed.

Energy distribution characteristics along roadway strike orientation

The spatial relationship between the locations of AE event numbers and the excavation face during sample excavation is shown in Fig. 7a. AE event numbers during roadway excavation is influenced by geological factors and mining techniques. Generally, about 80% of AE event numbers occur ahead of the excavation face. However, as observed in experimental datasets B-1 and D-1 (Fig. 7a), significant variations in the number of AE events in front of and behind the excavation face can occur when geological conditions affecting roadway excavation change abruptly along the excavation direction. Specifically, in areas of coal seam phase transition, AE event numbers behind the face increases, reducing the proportion of AE event numbers in front of the face to 57%. When the roadway is excavated perpendicular to the fault plane, more frequent AE event numbers occur behind the excavation face after it crosses the fault, with only 46% of AE event numbers located in front of the face. This indicates that when geological and technical factors align consistently with the excavation direction, the risk of rock burst is generally higher in front of the excavation face. However, abrupt changes in these factors along the excavation direction can lead to variations in rock burst risk in both front and back areas of the excavation face.

The AE counts and energy for each sample are shown in Fig. 7b,c. When the influencing factors along the excavation direction are consistent, the AE count is generally higher in front of the excavation face, accounting for approximately 80% of the total count. However, when abrupt changes in influencing factors occur along the excavation direction, the variation in AE counts follows a similar trend, with a sharper decrease in the count in front of the face, reducing its proportion to about 30%. Conversely, during excavation along the fault plane, the count in front of the face rapidly rises to around 98%. Under normal conditions, the energy of AE in front of the excavation face generally represents about 74% of the total energy. However, when the excavation speed increases, the energy proportion behind the face rises sharply, reducing the proportion in front of the face to 37%. During perpendicular excavation through a fault plane, the energy proportion in front of the face decreases to 31%, and when excavating from a thinner to a thicker coal seam, this proportion drops to only 12%. In contrast, when excavating along the fault plane, nearly all energy is concentrated in front of the excavation face.

Generally, the risk of rock burst is higher in front of the excavation face. When excavation speed increases, the burst risk remains high in front, but the energy behind the face is not fully released, leading to a higher burst intensity. Additionally, due to the influence of faults and variations in coal seam thickness, the risk of rock burst increase in the surrounding rock behind the excavation face.

Energy-based method for rock burst in excavation roadways

Identification indicators for roadway rock burst

In practical engineering, rock mass materials typically show strain-softening behaviours, that is, during the deformation and failure process of rock masses, the physical and mechanical properties of the rock continuously deteriorate as fractures develop within the material. Considering a circular roadway (as shown in Fig. 8) with a radius is R, the roadway is subjected to a triaxial isotropic stress state. At infinity, the in-situ stress of the rock mass is P0. Without considering any support measures, the following conditions apply:

where, σ1, σ2, σ3 mean the maximum principal stress, intermediate principal stress, and minimum principal stress of the surrounding rock at infinity, MPa; and P0 means the in-situ stress of the rock mass at infinity, MPa.

After roadway excavation, the stable triaxial stress equilibrium state of the coal mass is disrupted, leading to a readjustment of the stress environment to achieve a new equilibrium state27. The coal mass undergoes sequential stages of crack compaction, elastic deformation, plastic deformation, and fracturing, ultimately resulting in failure. During this process, the crack field within the rock mass continuously evolves, accompanied by crack closure or coalescence. Therefore, describing the failure process of the roadway surrounding rock solely from the perspective of stress is unlikely to yield satisfactory results28,29. According to the laws of thermodynamics, energy transformation is the fundamental characteristic of the physical change process of materials. The failure of a material represents an instability phenomenon driven by energy transformation30, as illustrated in Fig. 9.

Assume the coal mass is in a closed system with no energy exchange with the external environment, and the coal is a homogeneous isotropic material. When the coal mass is subjected to compressive loading, the degree of crack development evolves from A to D as stress increases, leading to deformation and changes in energy. When the applied stress on the coal mass is less than the crack initiation stress, σcis, the coal undergoes only elastic deformation. At this stage, no cracks develop inside the coal mass (ignoring pre-existing cracks), and all external work is converted into elastic strain energy, as shown in stages A to B in Fig. 9.

When the applied stress exceeds σcis, cracks begin to develop within the coal mass. Elastic deformation occurs alongside plastic deformation, during which part of the external work continues to be stored as elastic deformation energy, while the remainder dissipates as frictional heat, surface energy, radiation energy, and other forms, as shown in stages B to C.

As stress continues to increase, the coal mass reaches its maximum stress-bearing capacity, σc. At this point, when the elastic strain energy stored in the coal exceeds its storage limit, the coal undergoes a transition from C to D, accompanied by significant energy release. This process can be described using Eq. (2) to represent the energy transformation31,32,33.

where, Uw represents the total work done by external forces on the coal mass, kJ; Ua represents the elastic strain energy stored due to elastic deformation of the coal mass, kJ; Ud represents the dissipated energy consumed during the failure of the coal mass, kJ.

In the principal stress space, the total work done by the principal stress of the rock mass in the direction of the principal strain can be calculated using the following formula, as represented in Eq. (3).

the elastic strain energy density of the surrounding rock can be calculated through the following formula34,35,36,37:

Existing experimental results indicate that the maximum elastic strain energy that coal-rock can store under failure conditions is essentially the same under the same confining pressure and unloading rate38. Therefore, assuming that the maximum elastic strain energy coal-rock can store under certain conditions is Um. Xie introduced the energy release rate and derived the global failure criterion for coal-rock under triaxial stress conditions39.

During roadway excavation, the stress state of the coal-rock mass rapidly adjusts and ultimately transitions into a uniaxial stress state, where σ1 = σc, σ2 = σ3 = 0 MPa. Thus, the above equation can be simplified as:

The energy dissipation reflects the development of internal cracks and the weakening of strength in the rock mass, which is an intrinsic property of the material. In fact, the failure of materials is primarily caused by irreversible energy dissipation. Before reaching peak strength, the rock mass mainly dissipates the stored releasable elastic strain energy by converting it into forms such as frictional heat, surface energy, and radiation energy through crack development. After the peak strength, the rock mass reaches its maximum capacity for storing elastic strain energy. As external forces continue to act, the work done by external forces is entirely used to further crack development. The extensive coalescence of internal cracks leads to the overall failure of the rock mass. The previously stored releasable elastic strain energy is rapidly released in a very short time. If this energy cannot be dissipated through the generation of cracks, it may leads to the ejection of fractured rock masses, resulting in rock burst. This can be expressed as:

where, Uγ represents the plastic deformation energy through mechanisms such as frictional heat, surface energy, and radiation energy, kJ; Uλ represents the energy consumed by the ejection and impact of rock masses, kJ.

Therefore, the plastic dissipation of energy is also crucial in the dynamic failure of rock masses. Based on the plastic potential function, the plastic energy dissipation per unit volume of rock mass can be obtained40,41.

where, ε1p、ε2p、ε3p are the plastic strains in the directions of the maximum, intermediate, and minimum principal stresses respectively, MPa; dλ is the plastic multiplier determined by the loading conditions; and g is the plastic potential function.

The dissipation energy is used to characterize the deterioration of rock mass strength, and the damage rate of the surrounding rock of the roadway is defined as ω.

When ω = 1 is assumed, the elasticity of the rock mass material is completely lost and it no longer has the ability to store elastic strain energy, that is, Ua = 0. Meanwhile, the occurrence of rock burst is not considered at this time either, namely, Uλ = 0.

The accumulation of elastic strain energy inside the rock mass is the main driving energy source for the occurrence of rock burst. Therefore, the risk level of rock burst occurrence can be judged by the accumulated elastic energy of the surrounding rock. The rock burst risk index is defined as the ratio of the current elastic strain energy density accumulated in the surrounding rock to the minimum energy required for rock burst occurrence.

Evolution process of rock burst in excavation roadway

In fact, in a similar simulation, since the experimental device cannot monitor the elastic strain and plastic strain separately, it is difficult to quantitatively calculate the surrounding rock damage ω and rock burst risk index ζ during the excavation roadway process through Eqs. (9) and (11). Therefore, to address this limitation and ensure the accuracy of the simulation, the numerical simulation method was applied to calculate the evolution law of each index, considering the practical constraints of laboratory testing42,43.

The calibration process was simplified by adopting standard test conditions and using a strain-softening constitutive model44,45. A parameter modification process is shown in Fig. 10a21. A normal displacement of (2.5 × 10− 6) m/step was applied to the coal specimen’s top and bottom surfaces. The model’s axial plane was set as a free boundary, and a strain-softening constitutive model was utilized. The calculation halted after 1000 steps. Experimentally validated simulated parameters are listed in Table 2. When extensive tensile failure occurred within the coal specimen, its uniaxial compressive strength was about 7.8 MPa (the uniaxial compressive strength of the coal sample was about 7.5 MPa through experimental testing). When extensive shear failure happened within the rock specimen, its uniaxial compressive strength reached 33.6 MPa (the uniaxial compressive strength of the rock sample was about 32.5 MPa through experimental testing). The consistency of the simulation results with actual physical and mechanical test results demonstrates the rationality of the calibrated parameters, despite the simplified nature of the model (taking coal as an example, the stress-strain curves as shown in Fig. 10b). The minimum energy Um required to calculate the dynamic failure of coal and rock mass according to Eq. (6) is 0.020 MJ/m3 and 0.109 MJ/m3, respectively. The dissipated energy consumed by complete damage of coal mass is 3.46 MJ/m3 and 38.29 MJ/m3 (Fig. 10c).

Based on the above parameters, a FLAC3D numerical simulation model with a length, width, and height of 80 m each and a grid size of 0.5 m was established, as shown in Fig. 11a. To simplify the model, fixed boundaries were applied to the bottom and four sides of the model, while the top of the model was set as a free boundary to represent typical excavation conditions. The roadway was located in a coal seam with a burial depth of approximately 500 m. There was a 25 m thick roof strata above the coal seam, and the burial depth of the upper boundary of the model was 475 m. The unit weight of the strata was about 25 kN/m3. Therefore, a uniform load of 11.875 MPa was applied to the top of the model to simulate the overlying strata self-weight. According to the in-situ stress test results, the horizontal principal stress was 1.62 times the vertical stress. Thus, the lateral pressure coefficient of the model was determined to be 1.646. The simulated roadway was located at X: 37.5 ~ 42.5 m, Y: 0 ~ 40 m, and Z: 43 ~ 47 m, that is, the roadway was in the center of the model, with a top coal retention of 7.5 m and a bottom coal retention of 18.5 m, and the roadway excavation length was 40 m, as shown in Fig. 11b.

The energy distribution of the surrounding rock at the position of 40 m in the roadway when the roadway is driven to 30 m, 40 m and 50 m are shown in Fig. 11c–e respectively. Energy adjustment zones were observed within certain ranges on both sides as well as the roof and floor during the roadway excavation process, acknowledging that the simplified boundary conditions still capture the essential energy distribution trends. In the roadway sidewall, the elastic strain energy of surrounding rock accumulates 4.5 ~ 6.5 m from the roadway center, while decreasing in other areas. Regarding the roadway floor, as the distance from the center rises, the surrounding rock elastic energy transitions from full release, to accumulation-then-release, and finally to full accumulation. Also, in both the sidewall and floor, the variation degree of elastic strain energy gradually lessens as the distance from the center increases.

Characteristics of energy distribution during roadway excavation. (a) Numerical simulation model of roadway excavation. (b) Monitoring plane (Y = 40 m). (c) Elastic strain energy density nephogram of monitoring plane. (d) Elastic strain energy density curve of rib. (e) Elastic strain energy density curve of floor.

The surrounding rock is divided into energy accumulation area and energy release area according to the change of elastic strain energy during the excavation process of the roadway, and the area where the plastic dissipation energy exceeds 10% Ul is divided into damage area. In accordance with the aforementioned methodology, the energy distribution characteristics within the simulated model obtained through FLAC3D computations as shown in Fig. 12. The energy accumulation area mainly develops to the upper and lower sides of the roadway, and the energy release area mainly develops to the left and right sides of the roadway. The damage area is mainly distributed in the energy release area of the surrounding rock in the shallow part of the roadway, and there is also a small range of energy accumulation areas on the upper and lower sides of the roadway.

As shown in Fig. 13, taking the roadway floor as an example, the elastic strain energy density reaches its maximum at a position approximately 9 m away from the roadway floor, and the rock burst risk index is about 1.2. The plastic dissipation energy density of the surrounding rock begins to increase rapidly. While the surrounding rock is gradually accumulating energy, plastic deformation is also occurring simultaneously. At a position approximately 5 m away from the roadway floor, the plastic deformation reaches its maximum, and the damage rate of the surrounding rock is about 0.4. It should be noted that the reason why the plastic deformation energy density of the floor starts to decline after reaching its maximum is mainly that the stress adjustment process after roadway excavation cannot be fully realized in the simulation calculation. In actual situations, the closer the area is to the roadway, the greater the damage degree of the surrounding rock. That is, the shallow surrounding rock beneath the roadway is widely damaged, its ability to accumulate elastic energy is greatly reduced, and the rock burst risk index is basically zero; while the deep surrounding rock has a smaller damage degree but accumulates more elastic energy, which is the main source of rock burst in the heading roadway.

In summary, the roof and floor were respectively the released elastic strain energy region and the accumulated elastic strain energy region from shallow to deep before roadway excavation, as shown in Fig. 14. The roadway sides were released elastic strain energy region, and the front of the working face was an accumulated elastic strain energy region. After excavation, the roof and floor had the adjust-released elastic strain energy region and the adjust-accumulated elastic strain energy region in the excavated area; the roadway sides had the adjust-released elastic strain energy region; and the front of the working face had adjust-accumulated elastic strain energy region.

The rock burst mechanism during roadway excavation is that the elastic strain energy amassed in the shallow surrounding rock on the roof, floor and sides is released. Meanwhile, the plastic dissipation energy spikes, worsening the surrounding rock’s condition. In contrast, the deep surrounding rock suffers less damage but accumulates ample elastic strain energy, being the main source of rock burst. Notably, the region where plastic dissipation energy builds up is the main damage zone. When the stored elastic strain energy is suddenly released, it triggers instant deformation and failure of the damaged shallow surrounding rock, leading to a rock burst.

Discussion

The phenomenon of energy zone evolution in the excavation roadway was discovered through similar simulation experiments. Meanwhile, the rock burst risk index for the excavation roadway was established and the occurrence process of rock burst in the excavation roadway was simulated. Based on the above research findings, taking a mining face in Huating as an example, the influencing factors of impact risks at the excavation face were analyzed, and numerical simulation models of the roadway excavation process under different factors were established. According to the influence of different factors on the rock burst risk index and the surrounding rock damage, The collaborative prevention and control method of “pressure relief - load reduction - reinforcement” for the excavation roadway was proposed, which can effectively reduce the rock burst risk during the excavation process.

Engineering overview

The main mined No. 5 coal seam in a rock burst-prone coal mine in Gansu Province is an extra-thick coal seam with a thickness ranging from 21.2 m to 39.2 m and an average thickness of 31.5 m. It has a strong rock burst tendency and the fully mechanized top-coal caving mining technology in slices is adopted. The 2501 mining area is the main mining area of this coal mine. The 250107-1 working face is the seventh working face on the upper slice in the 2501 mining area, with an average slice thickness of 12.1 m.

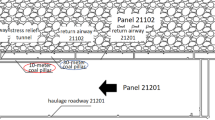

On the west side of the WF250107-1 is solid coal, on the east side is the goaf of the 250106-1 gob, on the north side is the main roadway of the 2502 mining area of the adjacent mine, and on the south side is the main roadway of the 2501 mining area, as shown in Fig. 15. The tailgate of the WF250107-1 is 6 m away from the 250106-1 gob, and the headgate of the WF250107-1 is 200 m away from its tailgate. The headgate is 5.4 m wide and 3.9 m high, with a top coal thickness of 8.5 m and a bottom coal thickness of 15.7 m. The tailgate is 5.0 m wide and 3.8 m high, with a top coal thickness of 7.3 m and a bottom coal thickness of 18.8 m. The open-off cut is a rectangular roadway, which is 8.2 m wide and 3.2 m high.

The damage and seismic source locations of the seven rock bursts during the roadway excavation of the WF250107-1 were counted (see Fig. 15). The general details of previous accidents are shown in Table 3. The two most severe rock bursts happened on January 10, 2020 (damage range: 100 m) and May 20, 2020 (damage range: 120 m). Notably, the excavation roadway of WF250107-1 mainly exhibits floor heave, typically around 0.2 m.

The distribution of microseismic events with energy greater than 0.1 × 104 J during the roadway excavation of 250107-1 as shown in Fig. 15. The spatial prediction of rock burst areas during the excavation of 250107-1 was carried out by using the bursting strain energy index47,48,49,50. According to the characteristics of rock burst manifestations and the distribution of bursting strain energy index, there were three rock burst areas during the excavation period: A was mainly affected by the goaf and the outward offset of the open-off cut; B was mainly affected by the goaf and folds; C was mainly affected by folds.

The characteristics of all microseismic events in the three areas were shown in Fig. 16. The average energy of microseismic events in Area A is the largest, and the microseismic energy per unit area is also the greatest, approximately 12.0 J/m2; the microseismic energies per unit area in Area B and Area C are basically the same, being 4.7 J/m2 and 4.5 J/m2 respectively. However, due to the influence of lateral hanging roof in the goaf, the rock burst area range in Area B is larger and the frequency is higher. Under the influence of folds and the goaf, microseismic events happen rather frequently in the two roadways. The gob-side tailgate is substantially affected by the lateral hanging roof of the goaf, leading to a relatively high frequency and large energy of microseismic events. It can be inferred that the rock burst risk during the excavation of roadways is also considerably influenced by the dynamic load generated from roof breakage.

To sum up, folds, goafs and the dynamic load are the main influencing factors for the rock burst in the excavation roadways. Among them, folds have an insignificant impact on the vertical stress of the coal and rock mass but a greater impact on the horizontal stress51,52; goafs will lead to an increase in the vertical stress and a decrease in the horizontal stress of the surrounding rock nearby53,54. Therefore, the influencing factors for the rock burst in the excavation roadways can be divided into three aspects: horizontal tectonic stress, mining disturbance stress and dynamic load.

Effect of different conditions on rock burst of roadway excavation

The control variable method was adopted to investigate the effects of different influencing factors on rock burst behavior during roadway excavation. Specifically, the stress boundary conditions of the model were modified, or additional stress waves were applied, to independently simulate the three influencing factors. Although each factor was analyzed in isolation due to modeling simplifications, this approach allows the fundamental influence trends of individual factors to be accurately captured, which can be further superimposed to infer multi-factor coupled responses in practical engineering applications55. The simulation schemes are summarized in Table 4, where m represents the ratio of horizontal stress to vertical stress, n represents the ratio of vertical stress to horizontal stress, and D denotes the ratio of dynamic loading stress to horizontal stress.

Horizontal tectonic stress

The characteristics of the surrounding rock region within a 30 m range of the roadway under the influence of different horizontal tectonic stresses are shown in Fig. 17. (Given that the disturbance range induced by roadway excavation is comparatively limited, in the area beyond the 30 m range, the elastic strain energy exhibits only slight alterations, the plastic dissipation energy remains at a low level, the degree of damage is insignificant, and consequently, the influence on rock burst is relatively negligible. Hence, for the purpose of discussion, the energy accumulation zone, energy release zone, as well as the surrounding rock damage area within the 30 m vicinity of the roadway, which play a more prominent role in contributing to the rock burst hazard, have been singled out.) When the horizontal stress coefficient m = 1.0, the overall shape of the energy accumulation area and the main damage area of the surrounding rock of the roadway is approximately diamond-shaped, and the overall range is relatively small. When m = 1.2 ~ 1.4, the energy accumulation area of the surrounding rock begins to develop towards the upper and lower sides, and the energy accumulation areas on the left and right sides disappear. The main damage area of the surrounding rock develops at the coal on the top and bottom of the roadway, and the plastic dissipation energy density gradually increases with the increase of the horizontal stress coefficient. When m = 1.6 ~ 2.0, the energy accumulation areas at the top and bottom of the roadway continue to expand, and the distance from the roadway surface gradually increases. The plastic dissipation area develops several slender horizontal branches in the coal at the top and bottom, and the length of the branches gradually increases with the increase of the horizontal stress coefficient. With the increase of the horizontal stress, the development of fractures in the horizontal direction is restricted, and the main damage areas of the surrounding rock are manifested in the roof and floor. Meanwhile, the energy accumulation areas are also located in the roof and floor of the roadway. Therefore, the excavation roadway dominated by horizontal stress is more likely to experience rock burst instability in the roof and floor of the roadway.

As illustrated in Fig. 17, it becomes manifest that the horizontal tectonic stress wields a pronounced influence on the magnitude of energy accumulation at the top and bottom of the roadway. The influence of the horizontal tectonic stress on the length of each region within the roadway roof were shown in Fig. 18a. Notably, the length of the energy accumulation zone exhibits a trend of initially increasing and subsequently diminishing with the increase of the horizontal stress coefficient m. When m = 1.6, the length of the energy accumulation zone reaches its maximum value of approximately 12 m. The lengths of the energy release area and the surrounding rock damage area gradually increase with the increase of the horizontal stress coefficient m. When m increases from 1.0 to 2.0, the lengths of the energy release area and the surrounding rock damage area increase by about 2.6 times (the length of the energy release area increases from 2.5 m to 9 m, and the length of the surrounding rock damage area increases from 3.3 m to 12 m).

The variations of ω and ζ under different horizontal tectonic stress coefficients are shown in Fig. 18b. In the roadway roof, the peak position of the rock burst risk index ω gradually moves further away from the roadway as the horizontal tectonic stress coefficient m increases. The magnitude of the ω peak exhibits an initial upward trend followed by a downward shift as the value of m ascends, and thereafter it remains essentially stable. When m = 1, the peak position of the rock burst risk index ω is approximately 3.5 m away from the roadway, and the peak value of ω is about 1.67; when m = 1.6, the peak position of the rock burst risk index ω is about 9.5 m away from the roadway, and the peak value of ω reaches its maximum of approximately 9.06, which is 442.5% higher than that when m = 1; when m = 2, the peak position of ω is the farthest from the roadway, approximately 11.5 m, which is about 228.6% deeper into the roadway compared to when m = 1, and the peak value of ω is about 8.4.

Both the peak position and the peak magnitude of the surrounding rock damage ζ gradually increase as the horizontal tectonic stress coefficient m increases. When m = 1, the peak position of ζ is approximately 2 m away from the roadway, and the peak value of ζ is about 0.025; when m = 2, the peak position of ζ is the farthest from the roadway, approximately 6 m, which is about 200% deeper into the roadway compared to when m = 1, and the peak value of ζ is about 0.358, which is about 13.3 times higher than that when m = 1.

Mining disturbance stress

The characteristics of the surrounding rock partition in the roadway under the influence of different mining disturbance stresses are illustrated in Fig. 19. The variation of the elastic strain energy and the distribution trend of the plastic dissipation energy of the surrounding rock do not change significantly. The energy accumulation areas are mainly distributed on the sides of the roadway. As the mining disturbance coefficient rises, the extent of the energy accumulation area expands to a certain degree. When the mining disturbance stress coefficient n = 2.0, the energy accumulation area of the roadway surrounding rock is approximately butterfly-shaped. As the mining disturbance stress coefficient increases, the energy accumulation area enlarges. When n = 3.2, the energy accumulation areas on the sides of the roadway gradually connect, forming a relatively large energy accumulation area. When n = 2.0, the surrounding rock damage areas are distributed on sides of the roadway, approximately semi-circular. With the increase of n, the surrounding rock damage areas gradually expand. When n = 3.2, the length of the surrounding rock damage area remains basically unchanged, and several vertical branches develop on floor and roof, and their heights gradually increase with the increase of the mining disturbance coefficient. With the increase of the mining disturbance stress, a butterfly-shaped plastic zone may develop on both sides of the roadway, resulting in relatively obvious deformation of the two sides of the roadway. Meanwhile, when n = 4.0, the damage areas at the top and bottom of the roadway all tend to close. Therefore, when the mining disturbance stress is relatively large, a wide range of deformation of the roadway roof and floor may occur.

The influence of the mining disturbance stress on the length of each region within the right side of the roadway is shown in Fig. 20a. Notably, the length of the energy accumulation zone exhibits a trend of initially increasing and subsequently diminishing as the mining disturbance stress coefficient n increases. When n = 3.2, the length of the energy accumulation zone reaches its maximum value of approximately 33.5 m. The lengths of the energy release area and the surrounding rock damage area gradually increase with the increase of the mining disturbance stress coefficient n, but the overall growth rate is not significant. When n increases from 2.0 to 4.0, the lengths of the energy release area and the surrounding rock damage area increase by 2.5 times and 1.3 times respectively (the length of the energy release area increases from 2 m to 7 m, and the length of the surrounding rock damage area increases from 3.5 m to 8 m).

The variations of ω and ζ under different mining disturbance stress coefficients are shown in Fig. 20b. In the rib of roadway, the peak position of the rock burst risk index ω gradually moves further away from the roadway as the mining disturbance stress coefficient n increases. The magnitude of the ω peak initially rises and subsequently declines as the value of n goes up, and after that, it remains largely static. When n = 2.0, the peak position of ω is approximately 3 m away from the roadway, and the peak value of ω is about 2.87; when the mining disturbance stress coefficient n = 2.8, the peak position of ω is about 4.5 m away from the roadway, and the peak value of ω reaches its maximum of approximately 4.56, which is 58.9% higher than that when n = 2.0; when the mining disturbance stress coefficient n = 4.0, the peak position of the rock burst risk index ω is the farthest from the roadway, approximately 8 m, which is about 166.7% deeper into the roadway compared to when n = 2.0, and the peak value of ω is about 3.51.

Both the peak position and the peak magnitude of the surrounding rock damage ζ gradually increase as the mining disturbance stress coefficient n increases. When n = 2.0, the peak position of ζ is approximately 1.5 m away from the roadway, and the peak value of ζ is about 0.042; when n = 4.0, the peak position of ζ is the farthest from the roadway, approximately 4 m, which is about 1.7 times deeper into the roadway compared to when n = 2.0, and the peak value of ζ is about 0.316, which is about 6.5 times higher than that when n = 2.0.

Dynamic stress

Dynamic loading simulations were conducted after roadway excavation and static equilibrium. The model boundaries were set as viscous boundaries to absorb reflected waves. A sinusoidal stress time history with a frequency of 20 Hz was applied at the center of the model top boundary, with stress amplitudes of 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20 MPa. Rayleigh damping with a coefficient of 0.02 was also adopted to account for stress-wave attenuation. After the dynamic calculations, energy indices including elastic strain energy and plastic dissipated energy were extracted to analyze the zoning characteristics of the surrounding rock under different dynamic stress.

The characteristics of the surrounding rock partition in the roadway under the influence of dynamic stress are shown in Fig. 21. Dynamic stress does not lead to changes in the energy accumulation characteristics of the roadway surrounding rock. As the dynamic stress increases, the energy accumulation area and the surrounding rock damage area are still distributed at the floor and roof of the roadway, while the energy release area is distributed on the rib of the roadway. However, with the increase of the dynamic stress, the ranges of energy accumulation and release of the surrounding rock both expand. When the dynamic stress is 20 MPa, the ranges of the surrounding rock damage area and the energy accumulation area increase significantly compared with those under low dynamic stress (D = 0.25). Therefore, the distribution range of the energy density of the surrounding rock in the roadway excavation is relatively sensitive to dynamic loads. During the roadway excavation process, it is imperative to focus on implementing preventive and control measures aimed at reducing dynamic stress within the mining area. This is crucial for alleviating the rock burst that may occur during the roadway excavation.

The influence of the dynamic stress on the length of each region within the roadway roof is shown in Fig. 22a. The length of the energy accumulation area remains basically unchanged. The main reason is that the disturbance range of the dynamic stress on the roadway surrounding rock is relatively large, and the length of the energy accumulation area may have already exceeded the scope of numerical simulation. The lengths of the energy release area and the surrounding rock damage area gradually increase with the increase of the dynamic stress D. When D increases from 0 to 1, the lengths of the energy release area and the surrounding rock damage area increase by about 9.3 times and 1.1 times respectively (the length of the energy release area increases from 7 m to 13.5 m, and the length of the surrounding rock damage area increases from 9 m to 19 m).

The variations of ω and ζ under the influence of the dynamic stress are shown in Fig. 22b. In the roadway roof, the peak position of ω gradually moves further away from the roadway as the dynamic stress D increases. The magnitude of the ω peak gradually decreases as the value of D increases. When there is no dynamic stress, the peak position of ω is approximately 8.5 m away from the roadway, and the peak value of ω is about 9.99; when the dynamic stress D = 1, the peak position of the rock burst risk index ω is about 18.5 m away from the roadway, which is about 117.6% deeper into the roadway compared to when there is no dynamic stress, and the peak value of ω is about 3.50 at this time, which is 65.0% lower than when there is no dynamic stress. The peak position of the surrounding rock damage ζ remains basically unchanged, approximately 5.5 m, but the peak magnitude of ζ gradually increases as the dynamic stress D increases. When there is no dynamic stress, the peak value of ζ is about 0.273; when D = 1, the peak value of ζ is about 0.527, which is about 93.0% higher than when there is no dynamic stress.

That is to say, the dynamic stress reduces the rock burst risk index of the roadway, but this does not mean that the dynamic stress reduces the possibility of rock burst occurring in the roadway during excavation. Because under the influence of the dynamic stress, the damage area of the roadway develops on a large scale, and the damage degree of the surrounding rock in the shallow part of the roadway increases, resulting in a reduction in the roadway’s ability to resist rock burst. On the contrary, it increases the possibility of large deformation and instability of the roadway surrounding rock, making the roadway under the influence of dynamic stress more likely to experience rock burst during excavation.

Field test

The key to preventing and controlling rock burst in roadway excavation was artificially controlling the accumulated elastic strain energy in the deep surrounding rock of the roadway and strengthening the damaged surrounding rock in the shallow part. That is to say, the prevention and control of rock burst in roadway excavation mainly focuses on three aspects: reducing concentrated static loads, weakening impact dynamic loads, and strengthening the damaged surrounding rock. Therefore, a collaborative prevention and control method of “pressure relief - load reduction - reinforcement” has been proposed for roadway excavation, as shown in Fig. 23.

-

(1)

Pressure relief measures: For the coal seam, measures such as borehole pressure relief, blasting pressure relief or hydraulic slotting are adopted to reduce the concentrated static load of the surrounding rock of the roadway and release the accumulated elastic energy of the surrounding rock56,57,58.

Large-diameter boreholes in the coal mass are used to relieve pressure on the front, both sides and the floor of the roadway. The sidewall boreholes are 150 mm in diameter, 1 m in spacing and 20 m in depth. The boreholes in front of the roadway also have a diameter of 150 mm, with two placed on each side of the centerline, each 20 m deep. Additionally, an outward hole is drilled 0.5 m away from each sidewall, 30 m deep, having a horizontal spacing of 1.5 m and a vertical spacing of 1 m. The floor boreholes are 150 mm in diameter, with a spacing of 1 m and a depth of 19.5 m.

-

(2)

Load reduction measures: For the roadway on the goaf side, measures such as deep-hole presplitting blasting of the roof or hydraulic roof cutting are taken to cut off the hanging roof on the goaf side in advance and weaken the intensity of the dynamic load generated by the roof movement and breakage55,59.

Considering that the outside of the 250107-1 open-off cut is adjacent to the main roadway of the mining area in the neighboring mine, to cut off the hanging roof caused by its large-area goaf, deep-hole presplitting blasting of the roof is adopted to break the roof. The blasting holes are 38 m deep, with an inclination angle of 75°, constructed perpendicular to the roadway trend. The spacing between the holes is 5 m, the explosive charge amount is 40 kg, and the hole-sealing length is 15 m.

-

(3)

Reinforcement measures: For the areas with broken surrounding rock, grouting reinforcement measures are adopted to improve the overall strength of the surrounding rock of the roadway60,61.

Low-pressure grouting is carried out through 2 m shallow holes to fill the fractured areas on the roadway surface and improve the self-stabilizing ability of the roadway surface. Combined with high-pressure grouting through 4 m deep holes to seal the internal cracks in the shallow surrounding rock and enhance the strength of the shallow surrounding rock of the roadway.

During the driving of 250107-1 open-off cut, the pre-pressure relief plan was implemented. Merely 108 microseismic events were detected, with only 4 above 1 × 104 J and the max at 2.76 × 104 J. The microseismic energy per meter, microseismic frequency per meter and average microseismic energy of the open-off cut and Region B were shown in Fig. 24a. After optimizing the relief plan, for the open-off cut, the average microseismic energy was about 1.7 × 103 J, microseismic energy per meter was about 900 J, and microseismic frequency per meter was about 0.54, which decreased by 19.0%, 18.2% and 3.6% respectively compared with those in region B.

The drill cuttings method was used to monitor the rock burst risk during roadway for open-off cut. The amount of drill cuttings within the range of 2 ~ 12 m of the roadway sidewall in a 30 m range around Point H7–23, which is 50 m away from the transportation roadway, was generally between 1.6 ~ 2.5 kg/m, far less than the critical value of 3.12 kg/m, as shown in Fig. 24b. During the drilling process, no dynamic phenomena such as bit sticking and hole burst occurred.

All in all, the pressure relief effects of the pre-pressure relief measures for the open-off cut are quite good, which has ensured the safe driving of the 250107-1 open-off cut.

Conclusions

This study analyzes the energy evolution laws of excavation roadways under different stress environments, geological structures and coal seam occurrence conditions based on the mechanism of excavation dynamic disasters experimental system. The quantitative indicators for the rock burst risk and the damage to the surrounding rocks of excavation roadways were put forward. The mechanism of rock burst in excavation roadways was summarized and the variation of the rock burst risk index and the damage to the surrounding rocks of excavation roadways under the influence of horizontal tectonic stress, mining disturbance stress and dynamic load were analyzed based on three-dimensional numerical simulation. The main conclusions are as follows

-

(1)

The significant increase in the AE event numbers and energy is influenced by stress environments, geological structures, and coal seam occurrence conditions. In the dip direction of the roadway, the AE event numbers generally increase first and then decrease as the distance from the roadway surface increases. In the strike direction of the roadway, the AE event numbers in front of the excavation face is generally higher. However, regarding the intensity of the rock burst, it is not necessarily the case that regions with higher rock burst risk also experience the greatest rock burst intensity. The intensity of the rock burst is influenced by both the properties of the coal-rock mass in the rock burst area and the conditions of the roadway after excavation.

-

(2)

The distribution characteristics of the surrounding rocks of the excavation roadway were analyzed, and the rock burst risk index and the damage index of the surrounding rocks of the roadway were put forward. The rock burst mechanism of the excavation roadway was revealed: the area where elastic strain energy accumulates is the main source of the rock burst in the excavation roadway, and the area where plastic dissipation energy accumulates is the main area of the surrounding rock damage. When the elastic strain energy accumulated in the surrounding rocks is suddenly released, it will promote the instantaneous deformation and failure of the damaged surrounding rocks in the shallow part, thus inducing the rock burst in the excavation roadway.

-

(3)

The variation laws of the rock burst risk index and the damage index of the surrounding rocks of the excavation roadway under the influence of horizontal tectonic stress, mining disturbance stress and dynamic stress were simulated based on the actual situation of the mine. In the horizontal direction, the risk of rock burst increases with the increase of horizontal tectonic stress. In the vertical direction, it first increases and then decreases with the increase of mining disturbance stress. The dynamic stress disturbance significantly damages the surrounding rocks, weakening the roadway’s rock burst resistance, heightening the likelihood of large scale deformation and instability, and increasing the possibility of rock burst during excavation.

-

(4)

The coordinated prevention and control method of “pressure relief - load reduction - reinforcement” for rock burst in excavation roadways was put forward. It can effectively reduce the microseismic energy release during excavation roadway and ensure the safe excavation of the roadway, which has certain reference significance in the practice of preventing and controlling rock burst in excavation roadways.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, F. et al. Numerical investigation of dynamic disturbance process induced by a mining tremor based on time-dependent moment tensor. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 184, (2024).

Cook, N. G. W. The failure of rock. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstracts. 2, 389–403 (1965).

Askaripour, M., Saeidi, A., Rouleau, A. & Mercier-Langevin, P. Rockburst in underground excavations: A review of mechanism, classification, and prediction methods. Undergr. Space. 7, 577–607 (2022).

He, M., Cheng, T., Qiao, Y. & Li, H. A review of rockburst: Experiments, theories, and simulations. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 15, 1312–1353 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Cluster analysis of moment tensor solutions and its application to rockburst risk assessment in underground coal mines. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56, 6709–6734 (2023).

He, M., Xie, H. P., Peng, S. P. & Jiang, Y. D. Study on rock mechanics in deep mining enguneering. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Engineering 2803–2813 (2005). (in Chinese).

Xie, H. et al. Study on the mechanical properties and mechanical response of coal mining at 1000 m or deeper. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 52, 1475–1490 (2019).

Zhu, S. et al. Mechanism and monitoring and early warning technology of rock burst in the heading face of compound Thick coal seam. J. China Coal Soc. 45, 1659–1670 (2020). (in Chinese).

Zhang, C. et al. Influence mechanism and application analysis of bottom coal layer thickness on floor rock burst. J. China Coal Soc. 45, 3984–3994 (2020). (in Chinese).

Lv, J. et al. Failure characteristics and stability control technology of dynamic pressure roadway affected by the mining activity: A case study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 131, (2022).

He, M., Wang, Q. & Wu, Q. Y. Innovation and future of mining rock mechanics. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 13, 1–21 (2021).

Dai, L. et al. Quantitative mechanism of roadway rockbursts in deep extra-thick coal seams: theory and case histories. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 111, (2021).

Wang, G. et al. Behaviour and bursting failure of roadways based on a pendulum impact test facility. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 92, (2019).

He, M., Li, J., Liu, D., Ling, K. & Ren, F. A novel true triaxial apparatus for simulating strain bursts under high stress. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54, 759–775 (2020).

Liu, W., Zhou, H., Zhang, S. & Zhao, C. Variable parameter creep model based on the separation of viscoelastic and viscoplastic deformations. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56, 4629–4645 (2023).

Gong, F., Si, X., Li, X. & Wang, S. Experimental investigation of strain rockburst in circular caverns under deep three-dimensional high-stress conditions. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 52, 1459–1474 (2019).

Cook, N. G. W. The basic mechanics of rockbursts. J. South Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 64, 71–81 (1963).

Salamon, M. D. G. Energy considerations in rock mechanics: fundamental results. J. South Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 84, 233–246 (1984).

Gale, W. J. A review of energy associated with coal bursts. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 28, 755–761 (2018).

Zuo, Y. et al. Numerical study of zonal disintegration within a rock mass around a deep excavated tunnel. Int. J. Geomech. 12, 471–483 (2012).

Meng, N., Bai, J. & Yoo, C. Failure mechanism and control technology of deep soft-rock roadways: numerical simulation and field study. Undergr. Space. 12, 1–17 (2023).

Gao, X., Ma, Z., Shi, H. & Feng, J. Energy release induced rockbursts based on butterfly-shaped plastic zones in roadways of coal reservoirs. PLoS One 16, (2021).

Zhang, D. et al. Energy evolution law during failure process of coal-rock combination and roadway surrounding rock. Minerals. 12, (2022).

Du, F. et al. Rockburst mechanism and the law of energy accumulation and release in mining roadway: a case study. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 9, 67 (2022).

Cao, A. et al. Experimental study on damage characteristics of coal samples under true triaxial loading and dynamic unloading. Lithosphere. 2022 (2022).

ISMR. Suggested methods for determining the strength of rock materials in triaxial compression. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstracts. 15, 47–51 (1978).

Huang, R. Q. & Huang, D. Evolution of rock cracks under unloading condition. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 47, 453–466 (2013).

Xie, H., Li, L., Ju, Y., Peng, R. & Yang, Y. Energy analysis for damage and catastrophic failure of rocks. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 54, 199–209 (2011).

Xie, H., Lu, J., Li, C., Li, M. & Gao, M. Experimental study on the mechanical and failure behaviors of deep rock subjected to true triaxial stress: A review. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 32, 915–950 (2022).

Fan, Y. et al. Influence of tunneling methods on the strainburst characteristics during the excavation of deep rock masses. Eng. Geol. 201, 85–95 (2016).

Huang, D. & Li, Y. Conversion of strain energy in triaxial unloading tests on marble. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 66, 160–168 (2014).

Munoz, H., Taheri, A. & Chanda, E. K. Fracture energy-based brittleness index development and brittleness quantification by pre-peak strength parameters in rock uniaxial compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49, 4587–4606 (2016).

Li, C. C., Zhao, T. B., Zhang, Y. B. & Wan, W. K. A study on the energy sources and the role of the surrounding rock mass in strain burst. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 154, (2022).

Gong, F., Yan, J., Li, X. & Luo, S. A peak-strength strain energy storage index for rock burst proneness of rock materials. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 117, 76–89 (2019).

Meng, Q., Zhang, M., Han, L., Pu, H. & Nie, T. Effects of acoustic emission and energy evolution of rock specimens under the uniaxial cyclic loading and unloading compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49, 3873–3886 (2016).

Gong, F., Wang, Y. L., Wang, Z. G., Pan, J. F. & Luo, S. A new criterion of coal burst proneness based on the residual elastic energy index. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 31, 553–563 (2021).

Li, K., Luan, Y. Q., Zhang, J. P. & Liu, C. X. Experimental study on mechanical behavior, AE response and energy evolution of fissure-filled sandstone from mine roadway under conventional triaxial compression. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 130, (2024).

Chen, W., Lu, S. P., Guo, X. H. & Qiao, C. J. Research on unloading confining pressure tests and rockburst criterion based on energy theory. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 28, 1530–1540 (2009). (in Chinese).

Xie, H., Ju, Y. & Li, L. Y. Criteria for strength and structural failure of rocks based on energy dissipation and energy release principles. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 3003–3010 (2005). (in Chinese).

Darabi, M. K., Al-Rub, A., Omidi, O. & R. K. & A thermodynamically consistent framework to derive local/nonlocal generalized nonassociative plasticity/viscoplasticity theories. Int. J. Plast. 110, 19–37 (2018).

Kostina, A., Izuimova, A. & Plekhov, O. Numerical modeling of energy dissipation during fatigue crack propagation in metals. Proc. Struct. Integr. 42, 425–432 (2022).

Yuan, C. et al. Influence of tunnel excavation on the magnitude and rotation angle of principal stress in surrounding rock. Sci. Rep. 14, 25512 (2024).

Song, Z. Y., Zhao, Y., Dang, W. G. & Zhang, M. Mechanical responses of sandstone exposed to triaxial differential Cyclic loading with distinct unloading rates of confining stress: A particle-based numerical investigation. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 58, 4159–4184 (2025).

Cui, L., Sheng, Q., Zhang, J., Dong, Y. & Guo, Z. Evaluation of input geological parameters and tunnel strain for strain-softening rock mass based on GSI. Sci. Rep. 12, 20575 (2022).

Tian, X., Song, Z., Shen, X. & Xue, Q. Study on progressive failure mode of surrounding rock of shallow buried bias tunnel considering strain-softening characteristics. Sci. Rep. 14, 9608 (2024).

Gao, F. Numerical analysis on the influence of maximum horizontal principal stress on surrounding rock stability of roadway. Min. R D. 62–64. https://doi.org/10.13827/j.cnki.kyyk.2008.01.018 (2008).

Cai, W., Dou, L. M., Si, G. Y. & Hu, Y. W. Fault-induced coal burst mechanism under mining-induced static and dynamic stresses. Engineering 7, 687–700 (2021).

Dou, L., Cai, W., Cao, A. Y. & Guo, W. H. Comprehensive early warning of rock burst utilizing microseismic multi-parameter indices. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 28, 767–774 (2018).

Cai, W. et al. A new seismic-based strain energy methodology for coal burst forecasting in underground coal mines. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 123, (2019).

Bai, X. et al. Rock burst mechanism induced by stress anomaly in roof thickness variation zone: a case study. Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk. 13, 1805–1830 (2022).

Chen, G., Wang, Z. R., Dou, L. M. & IEEE. The study on prevention of rockburst when mining in folding structure areas. In Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference (APPEEC) (2011).

Xue, C. et al. Study on stress evolution law and rock burst mechanism in upright fold structure area of deep mine. Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk 14, (2023).

Tulu, I. B. et al. Analysis of global and local stress changes in a Longwall gateroad. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 28, 127–135 (2018).

Zhang, C., Zhao, Y. X., Han, P. H. & Bai, Q. S. Coal pillar failure analysis and instability evaluation methods: A short review and prospect. Eng. Fail. Anal. 138, (2022).

Lv, H., Cheng, Z., Xie, F., Pan, J. & Liu, F. Study on hydraulic fracturing prevention and control of rock burst in roof of deep extra-thick coal seam roadway group. Sci. Rep. 14, (2024).

Song, D., Wang, E., Liu, Z., Liu, X. & Shen, R. Numerical simulation of rock-burst relief and prevention by water-jet cutting. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 70, 318–331 (2014).

Gao, M., Zhao, Y. C., Chen, X., Lu, Q. T. & Liu, A. Destruction mechanism of rock burst in mine roadways and their prevention. Disaster Adv. 6, 34–43 (2013).

Li, J. et al. Dynamic response mechanism of impact instability induced by dynamic load disturbance to surrounding rock in high static loading roadway. Minerals. 11, (2021).

Hao, Q. et al. Crack extension characteristics of deep hole pre-splitting blasting under different in-situ stress fields and drill geometries: A numerical study. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 58, 1427–1449 (2025).

Wang, Q. et al. Comparative study of model tests on automatically formed roadway and gob-side entry driving in deep coal mines. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 31, 591–601 (2021).

Fu, J. et al. Research on the technology of gob-side entry retaining by pouring support beside the roadway in ‘three soft’ coal seam: A case study. Phys. Fluids 36 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the projects: National Natural Science Foundation of China (52274098, U21A20110), National Key Research and Development Program (2022YFC3004603), Jiangsu Province International Collaboration Program- Key national industrial technology research and development cooperation projects (BZ2023050).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (52274098, U21A20110), National Key Research and Development Program (2022YFC3004603), Jiangsu Province International Collaboration Program- Key national industrial technology research and development cooperation projects (BZ2023050).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. P. and (A) C. wrote the main manuscript text and acquired funding. C. X. analyzed the formals. Q. H and G. L. Conducted numerical simulations. Y. P. and C. X. analyzed the theory and simulation results. Y. P. and X. (B) Collected and organized data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article