Abstract

Functional veterinary music, defined as music specifically designed in its tempo, rhythm, harmonic structure, and frequency ranges to modulate animal emotional states and behavior, has emerged as an innovative strategy for managing lactating sows. Exposure to functional music in other studies during gestation and lactation has been shown to reduce stereotypic behaviors and increase positive interactions between humans and piglets, with potential indirect benefits for piglet survival and behavior. However, little is known about the effects of functional music applied specifically during lactation, a period in which environmental enrichment is often limited. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of functional music as an enriched auditory stimulus on maternal behavior, pre-weaning piglet mortality, and piglet coping styles during lactation. Three experimental groups were established: (1) Functional Music Group (FMG), animals stimulated with functional music designed and composed for use in pigs; (2) Pink Noise Group (PNG), animals exposed to pink noise as first control; and (3) Non-stimulated Group (NEG), animals not subjected to auditory stimulation as second control. Variables recorded included birth weight, causes of mortality, and several expressions of maternal behavior. The results showed a reduction in crushing-related mortality in the treatment group and behavioral improvements in the sows, suggesting that functional veterinary music may represent a practical enrichment tool for enhancing welfare and improving piglet survival during lactation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Environmental, management, and genetic factors influence piglet welfare and survival in early stages1,2,3. Despite advances in production technologies, pre-weaning piglet mortality remains one of the most persistent challenges in modern pig farming, with crushing and starvation being the most frequent causes of death4,5. Within swine production systems, the gestation and lactation phases represent critical periods, not only because of the physiological demands on the sow but also because of housing system constraints1,6. Confinement in individual crates limits the expression of natural behaviors, such as nest building, and restricts the sow’s ability to distance herself from her offspring, thereby favoring the development of stereotypic behaviors, such as bar-biting or motor restlessness7,8.

Piglet mortality has a significant economic impact, with estimated costs per litter loss ranging between €12 and €239. High mortality during the first days of life is also a negative welfare indicator9. In Europe, it is estimated that one out of five piglets is stillborn or dies before weaning, which has led to the conceptualization of this condition as a production disease resulting from a complex interaction among the animal, the mother, and the environment9,10. Manipulable materials, such as wood or straw, are provided during gestation to improve the sow’s emotional state, reduce peripartum stress, and decrease neonatal mortality11,12,13. Tactile and auditory stimulation, as well as the implementation of background music in farrowing rooms, have shown favorable outcomes in enhancing the human-animal bond and reducing stress8,14.

Functional veterinary music, defined as music specifically designed to modulate animal emotional states and behavior through its tempo, rhythm, harmonic structure, and frequency ranges, has emerged as an innovative form of environmental enrichment15. Exposure to functional music during gestation and lactation can reduce stereotypical behaviors and increase positive interactions between humans and piglets14. This approach not only benefits sow welfare but also has indirect effects on piglet survival and behavior. Unlike conventional or background music, functional music is intentionally composed to target physiological and behavioral responses. Evidence in pigs demonstrates that musical structure influences emotional reactions, with animals displaying distinct affective responses according to harmonic complexity and acoustic features16. Recent research has shown that functional music programs can reduce both psychological and physiological indicators of stress, including decreased salivary cortisol, lower alpha-amylase levels, reductions in skin lesions, fewer aggressive behaviors, and improved neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios—suggesting reduced chronic stress and better immune function. Moreover, pigs exposed to functional music exhibit increases in positive affective states such as contentment, playfulness, sociability, and relaxation15. These findings support the use of specially designed music as an effective environmental enrichment strategy, capable of reducing aggressive behaviors during regrouping, improving animal welfare, and providing pig producers with a practical solution to the negative impacts of aggression14. However, knowledge regarding the application of functional music during lactation –a phase in which environmental enrichment is particularly constrained– is scarce. Most available studies have focused on gestating sows or regrouping contexts, leaving unanswered whether functional music can influence maternal behavior, piglet survival, or piglet coping styles during the early-life period. Addressing this gap is essential to determine whether designed auditory enrichment provides measurable benefits during the critical pre-weaning phase. Within this context, to offer information about welfare-oriented auditory enrichment, the present study aimed to evaluate the effect of functional veterinary music on maternal behavior, pre-weaning piglet mortality, and piglet coping styles during lactation, and to determine if these effects lead to improved piglet survival and welfare outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study population

This study was conducted at a commercial swine farm, located in the municipality of Santa Rosa de Osos, Department of Antioquia, Colombia, at 2,550–2,630 m above sea level. The region presents a cool climate with annual mean temperatures of ~ 13 °C, high rainfall from March to December, and reduced solar radiation in October. Ecologically, it combines lower montane very humid forest and sub-páramo ecosystems, with rolling to mountainous topography and frequent soil saturation. This production unit works with commercial pigs from the Solla–Choice Genetics line and has facilities for various stages of the production cycle, including breeding, rearing, and finishing. The Solla–Choice Genetics line includes maternal lines such as CG36 (hybrid derived from Large White x Landrace, selected for docility, prolificacy, and maternal behavior), CGM3 (Large White, focused on growth efficiency and litter uniformity), and SM52 (Super Mom 52, hybrid for high numerical productivity and reproductive efficiency). This line was used for both sows and sires of the piglets.

Experimental design and sampling methods

An experimental study was conducted with multiparous pregnant females (n = 35) with reproductive histories ranging from 1 to 8 farrowings, distributed in independent modules with comparable environmental conditions. The farrowing pens consisted of standard commercial farrowing crates (manufactured by Hog Slat, dimensions: crate 20 inches at top, length 84 inches, height 40 inches, anti-crush bars, and creep area for piglets). The sows were assigned in a controlled manner to three experimental groups: (I) Group 1 – Treatment (n = 12), exposed to functional music specifically designed for pigs; (II) Group 2 – Control 1 (n = 11), exposed to pink noise as a non-musical auditory stimulus; and (III) Group 3 – Control 2 (n = 12), with no auditory stimulation. Each group remained under its respective conditions continuously throughout the study period, from entry into the farrowing room until weaning, ensuring consistency in exposure and analysis. All three experimental groups were assessed simultaneously in separate farrowing rooms to avoid cross-contamination of auditory stimuli. Sows were allocated to groups using a stratified randomization based on parity to ensure comparable average ages across groups (mean parity approximately 3–4 per group) and to avoid imbalance in maternal experience across groups. However, due to farm constraints in the availability of sows of each maternal line at the time of farrowing, genetic composition could not be fully balanced between groups. This limitation was recorded a priori and considered during the interpretation of the results. All sows were allocated according to the planned randomization scheme. A Directed Acyclic Graph (Fig. 1) was constructed a priori to identify potential confounders for weight gain and mortality. Genetic line was included as a background variable but not as an adjustment factor, since it was not part of the randomization criteria, and no causal pathway from music exposure to genotype exists. Genetic-line information was used to contextualize behavioral variation, not as an explanatory variable of treatment effects.

Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) to represent the effect of musical stimulation on pre-weaning mortality. For the construction of the model, the green and red arrows show the causal and biasing paths, respectively. The green with a triangle mark circle indicates the exposure, the blue with “I” mark circle the outcome, and the blue and red circles indicate the ancestor of outcome and the ancestor of exposure and outcome, respectively. Minimal sufficient adjustment sets for estimating the total effect of Musical Stimulation on Weight Gain: Ambiental Variables, Birth Weight, Diet, Disease, Productive Management.

Use of experimental animals

Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the commercial swine farm, which authorized the use of animals, facilities, and production data for research purposes. This study has the approval of the Animal Experimentation Committee of the University of Antioquia, Colombia (Act 12917), and all experiments were performed in accordance with the principles of respect, autonomy, beneficence, and non-maleficence for biomedical ethics18 and the regulations for the use of live animals in experiments of the Colombian Government statute for the protection of animals (Law 044 of 2009). All the experiments were performed in accordance with ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines19.

Musical intervention

The auditory stimuli used in this study were based on previous developments by the authors, who have explored the potential of musical stimulation in animal species as a tool to improve welfare and productive outcomes14,20. The composition of these pieces was based on a detailed analysis of piglets’ and sows’ natural vocalizations, intrauterine sounds recorded during gestation, psychoacoustic parameters, and music production techniques adapted to the auditory physiology of pigs. The methodology of functional music creation and composition was previously validated at the University of Antioquia’s Experimental Farm20. The functional music consisted of original compositions, incorporating elements like low-frequency melodies and harmonic structures derived from porcine vocalizations, played via JBL Control 1 Pro speakers at 60–70 dB measured at sow ear level. Pink noise was generated using a digital audio processor with a balanced spectrum (20 Hz–20 kHz), differing from white noise by having equal energy per octave rather than per frequency, serving as a neutral auditory control. Sound levels were consistent for both stimuli (60–70 dB at sow ear level). For the treatments, Group 1 (FMG) was stimulated (two daily sessions of one hour, from 9:00–10:00 a.m. and 3:00–4:00 p.m. for three weeks) with musical pieces based on acoustic elements derived from intraspecific porcine communication. Group 2 (PNG) was stimulated with pink noise (neutral frequency) at the same time as FMG. Group 3 (NEG) did not receive auditory stimulation.

Maternal behavior recording

A structured ethogram was developed to evaluate maternal behavior that included information on mother–offspring interaction (Table 1). A single observer, previously trained in behavioral observation techniques, conducted the observations to reduce inter-observer bias and improve the reliability of the records. The observer was blinded to treatment by conducting observations with auditory stimuli turned off during recording sessions. The instantaneous focal sampling method was used with sampling intervals every 30 s. Each sow was observed during 20-minute sessions twice a day: one in the period before stimulation (8:00–9:00 a.m.) and another during stimulation (3:00–4:00 p.m.), totaling 20 observation points per session per animal. Behavioral recording was performed twice a week for three consecutive weeks, starting one week after farrowing and ending during the weaning week.

Evaluation of piglets and sows

The following measurements were taken in piglets: birth weight (BW): recorded individually immediately after farrowing. Weaning weight (WW): determined at 4 weeks of age. Mortality and associated causes (M): All deaths occurring from birth to weaning were documented and classified according to their etiology (crushing, starvation, disease, others). Variables were recorded in the sows: maternal behavior (measured as count variables) and in the piglets: birth weight (kg), weaning weight (kg), mortality at four weeks postpartum (%), and causes of mortality (%).

Back-test

For the back-test, adapted from21, a total of 116 piglets were randomly selected (38 from the treatment group, 39 from the pink-noise control group, and 39 from the control group without stimuli). The test was conducted three times: at 5, 12, and 19 days of age. A fourth assessment at 26 days, as recommended by22, was not performed because weaning occurred at 21 days.

The test was carried out in the farm corridor. At 5 and 12 days of age, piglets were removed from the pen and placed on the lap of one of the operators. At 19 days of age, a V-shaped table was used to hold the piglets, with the assistance of two people. During the test, piglets were placed on their backs for 60 s. In each session, three parameters were evaluated and recorded: latency, defined as the time taken by the piglet to initiate movement; duration, defined as the total time spent moving; and frequency, defined as the number of attempts to move.

Statistical analysis

The study included variables related to pre-weaning mortality, productive performance variables at weaning (weight), maternal behavior, piglet behavior, and sow genetic composition. Significance was set at P < 0.05 for all analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata (version 19.0). Data are reported as means ± standard error or as percentages with 95% CI, unless otherwise specified. Data were analyzed using a combination of generalized linear models and classical inferential procedures, as guided by causal diagrams (Directed Acyclic Graphs, DAGs).

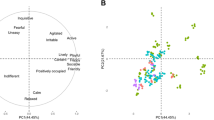

Pre-weaning mortality was modelled with a Poisson regression to account for the count nature of deaths per litter, adjusting for litter size where appropriate. The initial model included treatment group (musical stimulus, pink noise, control), sow breed, parity, and net birth weight of the litter. Variables were selected through a stepwise procedure (entry criterion P < 0.20). Model adequacy was assessed by the likelihood-ratio test, Pseudo R², and inspection of residuals. Results were expressed as regression coefficients with standard errors, z values, 95% confidence intervals (CI), and significance levels. Weight gain and productivity were first summarized descriptively. Daily weight gain, total weight weaned per treatment, and adjusted body weight at 21 days were compared by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test or Kruskal Walis Test when appropriate. To explore determinants of average daily gain, a multiple linear regression was fitted according to a directed acyclic graph – DAG, built using DAGitty v3.0 software23 and is presented in Fig. 1 to estimate the total effects of the exposures of interest on the outcome and identify potential confounders based on the presence of spurious (non-causal) exposure-outcome associations24. The DAG includes housing modules, litter mortality, and net weaned weight as explanatory variables. The coefficient of determination (R²) and its adjusted value were used to evaluate model fit. Maternal behaviors (frequency of stereotypies and other behaviors) were analyzed descriptively across treatments and sow genetic lines (CG36, CGM3, SM52). Piglet temperament was assessed with the Back Test in weeks 1–3. Frequencies of passive, intermediate, and active coping styles were plotted for each treatment and week. Differences among treatments and weeks were evaluated using contingency tables and χ² tests; when assumptions were not met, Fisher’s exact test was applied.

Results

Pre-weaning mortality

A total of 419 live-born piglets were recorded, distributed as follows: FMG group = 145, PNG group = 143, and NEG group = 133. Pre-weaning mortality rates were 4.36%, 7.33%, and 8.65% for groups FMG, NEG, and PNG, respectively. The group FMG exhibited the lowest number of losses (n = 4), with starvation accounting for 75% of deaths and crushing for the remaining 25%. Mortality causes in PNG (n = 4) were crushing (50%) and splay leg (50%). The group NEG shows more deaths (n = 6), with crushing, low birth weight, and starvation as the mortality causes at 50%, 33%, and 17% of losses, respectively.

A Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) was designed (Fig. 1) to represent the effect of musical stimulation on pre-weaning mortality. Accordingly, the variables included in a Poisson count model were treatment, sow breed, parity, and net birth weight of the litter. Through a stepwise selection process (criterion of P < 0.2), the model (Pseudo R² = 0.23; P = 0.005) did not find an effect of musical stimulation on pre-weaning mortality (Table 2). However, a trend toward lower losses was observed in the group of sows that received musical stimulation. In the model, parity did not show a relation with piglet mortality (p-values < 0.05 with no significant confidence intervals) and lower birth weight (Coef. −2.49; P = 0.024; 95% CI −4.665 −0.23) was associated with higher mortality (Table 2).

Weight gain and productivity at weaning

The FMG and PNG groups showed average daily weight gains of 0.269 kg/day and 0.260 kg/day, respectively, which were numerically similar to that observed in the NEG group (0.256 kg/day). The comparison of means did not reveal statistically significant differences among the treatments for daily weight gain (P = 0.802; Table 3). When adjusting weight gain to day 21—the usual weaning point—it maintained a similar pattern. Piglets in the FMG group reached an adjusted body weight of 7.21 kg, compared with 6.95 kg in the PNG group and 7.01 kg in the NEG group. Although the FMG group showed the highest numerical adjusted weight, one-way ANOVA indicated no statistically significant differences among treatments for body weight adjusted to 21 days (P = 0.21). Considering the total weight of weaned piglets per group (a variable with direct impact on the profitability of the production system), it was observed that the FMG group achieved the highest cumulative yield, followed by the PNG and NEG groups. However, these differences reflected numerical variation rather than statistically significant treatment effects.

A multiple linear regression model (Table 4) was constructed to explore the causal relationships among factors potentially affecting the daily weight gain of piglets, guided by a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG). In this model, the independent variables included were module, total litter mortality, and net weaned weight. The results indicated that the model was not statistically significant and that the adjusted coefficient of determination was negative (Adjusted R² = 0.0494), demonstrating a very low explanatory capacity.

Maternal behavior and genetic composition of the sows

Variables related to sow maternal behavior and their potential association with genetic line were evaluated (Fig. 2). Sows in the FMG group exhibited a lower frequency of stereotypic behaviors, such as bar-biting, than those in the NEG group. The ethogram (Table 1) details the observed behaviors, with frequencies reported as means ± SE in Fig. 2. No significant differences in overall maternal behaviors were found among groups (p = 0.15 by ANOVA), but trends suggest reduced stereotypies in FMG.

The experimental farm maintains its own genetic line, which was developed from imports based on the DEKALB breeding stock foundation. The maternal line CG36 (Fig. 3) is a hybrid derived from the cross between the grandparental lines M3 (Large White) and M6 (Landrace), both of French origin, selected for their traits of docility, prolificacy, and maternal behavior. The CGM3 line, also from Choice Genetics, is a maternal line exclusively developed from the Large White breed, with a focus on growth efficiency and litter uniformity. The maternal line SM52—commercially known as Super Mom 52—is a hybrid sow also developed by Choice Genetics, characterized by high numerical productivity and reproductive efficiency, although it may present behavioral challenges in high-demand environments.

Evaluation of piglet temperament

The individual behavioral test—Back test (Fig. 4)—conducted on piglets revealed that, overall, all groups displayed a passive coping style, with no statistically significant differences observed among them.

Sow–piglet interactions

The ethogram of sow–piglet interactions (Fig. 5) revealed a reduction in two key maternal behaviors in the group stimulated with functional music, Group 1 (FMG): grunting at piglets (outside the nursing context) and intentional tactile contact, such as touching piglets with the snout. These behaviors are typically associated with maternal communication, bonding, and the regulation of piglet activity.

Discussion

In this study, auditory stimulation influenced welfare and productive performance during the lactation period. Differences were observed in pre-weaning mortality, piglet weight gain, and sow maternal behavior, with notable variations among the three experimental groups: FMG (group with musical stimulation), PNG (group with pink noise), and NEG (group without stimulation). The FMG presented the lowest pre-weaning mortality rate (4.36%), compared with 7.33% in NEG and 8.65% in PNG. Although the difference may appear modest, it is relevant within the multifactorial context surrounding neonatal pig rearing. In the FMG group, composed mainly of CG36-line sows, the reduction in crushing deaths could be associated with lower stress levels during the peripartum period, which favored more stable maternal behavior and greater attention to litter. This result is consistent with the findings of25, who linked peripartum stress with increased neonatal mortality.

The results of this study indicate that the auditory stimulation group with functional music shows a lower number of deaths due to crushing. Although we can’t directly connect these findings with the experimental factors (based on causality web on Fig. 1), the hypothesis that functional music can generate positive effects on piglet neonatal survival, particularly by reducing deaths due to crushing is consistent with previous research that demonstrated the ability of certain types of music to induce relaxation states in farm animals, thereby enhancing general welfare and maternal behavior3,26.

Statistical analysis using Poisson regression allowed the identification of risk factors associated with pre-weaning mortality. A significant increase in risk was observed in parities 3, 7, and 8, likely related to greater physiological wear in advanced stages or the peak of metabolic demand in mid-parities27. In contrast, the negative association between birth weight and mortality indicates that piglets from heavier litters had better survival outcomes. In this context, birth weight acts as a protective factor, underscoring the importance of adequate maternal nutrition and management practices that support optimal fetal growth27,28. The differences observed in mortality and behavior cannot be directly attributed solely to the auditory stimulation due to the confounding influence of genetic lines across groups, as sows were not balanced by genotype owing to farm logistical constraints. However, the trends suggest a positive effect of functional music, particularly in reducing crushing incidents, independent of parity, as no direct association with parity was found beyond a trend in parity 3. The statement on net birth weight refers to its role as a protective factor against mortality, emphasizing the importance of optimizing birth weights through nutrition and management to complement auditory interventions. The differences in maternal behavior (Figs. 2 and 5) and piglet mortality cannot be attributed to parity or genetic line. Parity did not explain the pattern of mortality across groups, and although genetic lines differed in proportion (Fig. 3), this imbalance resulted from farm availability at farrowing, not from the allocation procedure. The differences in mortality and behavior align temporally and mechanistically with the auditory stimulation, supporting the interpretation that functional music acted as an environmental modulator, rather than genetic or parity effects driving outcomes. Although parity was not significant in the general model, an important trend was evidenced in parity 3 (coef. = 3.33; p = 0.059), which could reflect a critical stage in the maturation of maternal behavior, consistent with the observations of29. Complementarily, net birth weight of the litter emerged as a significant protective factor (coef. = −2.49; p = 0.024), confirming previous reports regarding its role as a predictor of postnatal viability2. Low-birth-weight piglets show reduced postnatal growth, lower feed efficiency, and require more time to reach market weight. Furthermore, low birth weight is associated with competitive disadvantages in accessing the udder and reduced colostrum intake, thereby exacerbating mortality risk30,31. Although musical stimulation did not remain as a significant variable in the final model, its exclusion does not rule out indirect or mediating effects—such as maternal behavior, cortisol levels, or mother–offspring bonding—that were not addressed in this quantitative analysis. In this sense, auditory stimulation may be considered an environmental modulator with subtle yet relevant effects on sow welfare and behavior, and consequently, on piglet survival.

A detailed analysis of causes of death revealed specific patterns in each group. In the FMG, only four deaths were recorded (three from starvation and one from crushing), with no cases of low birth weight or splay leg syndrome. This outcome suggests that music has an indirect influence on mother–offspring interaction and litter competition. In addition, sows in this group showed lower incidence of bar-biting (an indicator of chronic stress), despite having more alarm calls, and spent more time in the ventral position, thereby reducing abrupt lateral movements and the risk of crushing6,12. Sows in the FMG spent more time in the ventral position, which may reflect a calmer behavioral state with fewer abrupt postural changes. Increased time in the ventral lying position is widely considered beneficial because this posture reduces the risk of piglet crushing compared with more active or abrupt postural changes, particularly when sows remain calm, and transitions are gradual32. Previous findings show that sow postural patterns are closely associated with piglet survival and early growth (Girardie et al. 2023. Together, these indicators support the hypothesis that functional music positively modulates the emotional environment, promoting protective behaviors and greater postural stability during lactation33.

Among music-stimulated sows (Fig. 5), Group 1 (FMG), two maternal behaviors declined—grunting toward piglets outside the nursing context and purposive tactile interactions through snout contact—while the time spent in the ventral lying position increased. These behaviors are well-established components of maternal communication, bonding, and the modulation of piglet activity. The observed decrease may reflect a shift toward calmer behavioral states in sows exposed to music, consistent with evidence that auditory enrichment can promote relaxation. Moreover, Ocepek and Andersen34 reported that resting sows that engaged more frequently in non-nursing communication with their piglets exhibited higher postnatal piglet mortality, attributed to starvation, overlying, and overlying either with or without milk. This pattern supports the notion that maternal communication during active states, rather than passive or resting ones, is a stronger predictor of maternal performance and piglet survival.

In contrast, the PNG group also registered four deaths, but with a different distribution (two from crushing and two from splay leg). Although pink noise is generally considered a neutral stimulus, the results suggest that it may interfere with environmental perception or induce a basal state of alertness that affects maternal interaction. In this sense, auditory environmental stimuli can influence alertness, environmental perception, and potentially the quality of maternal interaction35. This group, dominated by the SM52 line, showed a lower proportion of low-birth-weight piglets but a higher incidence of splay leg, possibly linked to metabolic characteristics inherent to the genetic line36, warranting future studies to explore this relationship.

The NEG group without auditory stimulation, mostly composed of CGM3 sows, recorded the highest mortality (six deaths: one from starvation, three from crushing, and two from low birth weight). This suggests a potential genetic influence on neonatal survival, supporting previous findings on the combined role of environment and genetics in pre-weaning mortality37.

The role of genetics emerged as a key factor in the interpretation of the results. The CG36 line, which is predominant in the FMG, has been associated with low reactivity, better maternal behavior, and higher docility—traits that may have facilitated a better response to musical stimulation. Conversely, the SM52 line represented in the PNG exhibited higher restlessness and stereotypies, whereas the CGM3 line, present in the NEG, reflected lower stability in maternal behavior. These findings reinforce the need to include welfare and behavioral indicators in genetic selection programs beyond purely productive criteria38.

Regarding daily weight gain, the multiple linear regression analysis did not reveal significant differences among treatments. Nevertheless, the FMG achieved the highest total weaning weight. Although this finding could be explained by the greater number of piglets in this group, the adjustments for piglets per litter (e.g., average daily gain per piglet) showed similar trends with a possible cumulative effect of auditory stimulation on performance39. observed productive and behavioral improvements in piglets exposed to music during gestation and lactation. Although no statistically significant associations were detected, the observed trends highlight the need for more robust analytical models that integrate individual, environmental, and behavioral factors.

The individual behavioral test—Back test (Fig. 4)—conducted on piglets revealed that, overall, all groups displayed a passive coping style, with no statistically significant differences observed among them. This result suggests that the type of auditory stimulation applied to the sows during lactation did not exert a direct, observable effect on piglet temperament or early reactivity at this developmental stage. Since all piglets exhibited a similar coping style, it is hypothesized that their behavioral responses were comparable across the three groups, thereby reducing variation in piglet behavioral outcomes. Piglets with similar coping styles tend to show reduced behavioral variability, although individual differences and environmental factors may still influence specific behavioral responses40.

The absence of significant differences in mortality and weight gain among treatments may reflect the already satisfactory productive baseline of the farm. In such conditions, additional enrichment (such as auditory stimulation) may improve behavioral or emotional indicators without necessarily producing detectable changes in performance. This interpretation aligns with the observed trends in maternal behavior and with reports that welfare-oriented interventions often yield subtle or non-linear effects under high-performing conditions. This study presents certain limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, although sows were allocated using stratified randomization based on parity, the genetic composition of the groups could not be fully balanced due to the availability of farrowing sows at the time of allocation. This imbalance reflects a logistical constraint of the commercial production system rather than an error in the experimental design. Second, the farm already exhibited satisfactory reproductive and rearing outcomes, which may have limited the ability to detect treatment-related differences in piglet mortality or growth. Finally, welfare-oriented interventions such as auditory enrichment may induce subtle behavioral effects that require larger sample sizes or more refined behavioral metrics to translate into measurable productive changes. These limitations should guide the interpretation of our findings and inform future research directions.

Conclusions

In the present study, auditory stimulation through functional veterinary music is shown to be a practical and effective environmental enrichment strategy for enhancing maternal behavior and improving pre-weaning piglet survival in intensive pig production systems. It is recommended to increase sample size, extend observation periods, and include additional variables—such as suckling efficiency, individual piglet behavior, and microenvironmental conditions—to deepen the understanding of the underlying mechanisms. The lack of significant differences may also reflect already satisfactory baseline production levels on the farm, where additional stimulation enhances welfare without dramatic production shifts41,42,43.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Audio files for the functional music and pink noise are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, enabling replication of the auditory stimuli.

References

Loftus, L. et al. The effect of two different farrowing systems on Sow behaviour, and piglet behaviour, mortality and growth. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 232, 105102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2020.105102 (2020).

Quesnel, H., Gondret, F., Merlot, E., Loisel, F. & Farmer, C. Sow influence on neonatal survival: A special focus on colostrum. Bioscientifica Proc. 19, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1530/biosciprocs.19.0013 (2013).

Zhang, X., Li, C., Hao, Y. & Gu, X. Effects of different farrowing environments on the behavior of sows and piglets. Animals 10(2), 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020320 (2020).

Ellis, M., Pol, K., Cooper, N. & Shull, C. Observations on pre-weaning piglet mortality. J. Anim. Sci. 97(Suppl. 3), 56. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skz122.060 (2019).

Muns, R., Nuntapaitoon, M. & Tummaruk, P. Non-infectious causes of pre-weaning mortality in piglets. Livest. Sci. 184, 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2015.11.025 (2016).

Oliviero, C., Heinonen, M., Valros, A., Hälli, O. & Peltoniemi, O. A. T. Effect of the environment on the physiology of the Sow during late pregnancy, farrowing and early lactation. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 105(3–4), 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anireprosci.2007.03.015 (2008).

Brajon, S., Ringgenberg, N., Torrey, S., Bergeron, R. & Devillers, N. Impact of prenatal stress and environmental enrichment prior to weaning on activity and social behaviour of piglets (Sus scrofa). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 197, 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2017.09.005 (2017).

Mendes, J. P. et al. Behavior of sows exposed to auditory enrichment in mixed or collective housing systems. J. Veterinary Behav. 73, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2024.04.001 (2024). & da Silva, M. I. L.

Stygar, A. H. et al. Economic feasibility of interventions targeted at decreasing piglet perinatal and pre-weaning mortality across European countries. Porcine Health Manage. 8(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40813-022-00266-x (2022).

Langendijk, P. & Plush, K. Parturition and its relationship with stillbirths and asphyxiated piglets. Animals 9(11), 885. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9110885 (2019).

de Oliveira, R. F. et al. Effects of environmental enrichment on pigs’ behavior and performance. Revista Brasileira De Zootecnia. 52, e20210123. https://doi.org/10.37496/rbz5220210123 (2023).

Ringgenberg, N., Bergeron, R., Meunier-Salaün, M. C. & Devillers, N. Impact of social stress during gestation and environmental enrichment during lactation on the maternal behavior of sows. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 136(2–4), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2011.12.012 (2012).

Vanheukelom, V., Driessen, B. & Geers, R. The effects of environmental enrichment on the behaviour of suckling piglets and lactating sows: A review. Livest. Sci. 143(2–3), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2011.10.002 (2012).

Álvarez-Hernández, N., Vallejo-Timarán, D., de Rodríguez, B. & J Adapted original music as an environmental enrichment in an intensive pig production system reduced aggression in weaned pigs during regrouping. Animals 13(23), 3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13233599 (2023).

Zapata Cardona, J., Ceballos, M. C., Morales, T., Jaramillo, A. M., de Rodríguez, B. & E. D., & J Music modulates emotional responses in growing pigs. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 2446. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07300-6 (2022).

Zapata Cardona, J., Ceballos, M. C., Morales, T., Jaramillo, A. M., de Rodríguez, B. & E. D., & J Spectro-temporal acoustic elements of music interact in an integrated way to modulate emotional responses in pigs. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 983. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30057-5 (2023).

Colombia & Cámara de Representantes. Proyecto de Ley 044 (20 de Julio de 2009). Por La Cual se reforma La Ley 84 de 1989 Estatuto Nacional de Protección de Los animales y se dictan Otras disposiciones. Bogotá D C : Cámara De Representantes. Acta 26, 20–p (2010).

Beauchamp, T. L. & Childress, J. F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics 5th edn, 480 (Oxford University Press, 2001).

ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: guidelines for reporting animal research. (2020). Available at: https://arriveguidelines.org/sites/arrive/files/documents/ARRIVE%20guidelines%202.0%20- Accessed [February 2024].

Zapata Cardona, J. et al. Effects of a veterinary functional music-based enrichment program on the Psychophysiological responses of farm pigs. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 18660. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68407-6 (2024).

Zebunke, M., Nürnberg, G., Melzer, N. & Puppe, B. The backtest in pigs revisited—Inter-situational behaviour and animal classification. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 194, 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2017.05.011 (2017).

Zebunke, M., Repsilber, D., Nürnberg, G., Wittenburg, D. & Puppe, B. The backtest in pigs revisited—An analysis of intra-situational behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 169, 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2015.05.002 (2015).

Textor, J., van der Zander, B., Gilthorpe, M. K., Liskiewicz, M. & Ellison, G. T. H. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package ‘dagitty’. Int. J. Epidemiol. 45(6), 1887–1894 (2016). http://www.dagitty.net/dags.html

Shrier, I. & Platt, R. W. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), Article 70. (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-70

Pajor, E. A., Kramer, D. L. & Fraser, D. Regulation of contact with offspring by domestic sows: Temporal patterns and individual variation. Ethology 106(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0310.2000.00516.x (2000).

Mkwanazi, M. V., Ncobela, C. N., Kanengoni, A. T. & Chimonyo, M. Effects of environmental enrichment on behaviour, physiology and performance of pigs—A review. Asian-Australasian J. Anim. Sci. 32(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.17.0138 (2019).

Roehe, R. & Kalm, E. Estimation of genetic and environmental risk factors associated with pre-weaning mortality in piglets using generalized linear mixed models. Anim. Sci. 70(2), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1357729800054692 (2000).

Will, K. et al. Risk factors associated with piglet pre-weaning mortality in a Midwestern U.S. Swine production system from 2020 to 2022. Prev. Vet. Med. 232, 106316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2024.106316 (2024).

Yang, K. Y. et al. Effect of different parities on reproductive performance, birth intervals, and tail behavior in sows. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 61(3), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.5187/jast.2019.61.3.147 (2019).

Smit, M. et al. Consequences of a low litter birth weight phenotype for postnatal lean growth performance and neonatal testicular morphology in the pig. Animal 7(10), 1681–1689. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731113001249 (2013).

Tucker, B. et al. Piglet morphology: indicators of neonatal viability? Animals 12(5), 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12050658 (2022).

Girardie, O. et al. Analysis of image-based Sow activity patterns reveals several associations with piglet survival and early growth. Front. Veterinary Sci. 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2022.1051284 (2023).

Zeng, F. & Zhang, S. Impacts of Sow behaviour on reproductive performance: current Understanding. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 51(1), 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/09712119.2023.2185624 (2023).

Ocepek, M. & Andersen, I. Sow communication with piglets while being active is a good predictor of maternal skills, piglet survival and litter quality in three different breeds of domestic pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus). PLoS ONE. 13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206128 (2018).

Collarini, E., Capponcelli, L., Pierdomenico, A., Norscia, I. & Cordoni, G. Sows’ responses to piglets in distress: an experimental investigation in a natural setting. Animals 13(14), 2611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13142261 (2023).

Liu, X., Li, H., Wang, L., Zhang, L. & Wang, L. The effect of Sow maternal behavior on the growth of piglets and a genome-wide association study. Animals 13(24), 3753. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13243753 (2023).

Hessing, M. J. C., Hagelsø, A. M., Schouten, W. G. P., Wiepkema, P. R. & Van Beek, J. A. M. Individual behavioral and physiological strategies in pigs. Physiol. Behav. 55(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9384(94)90007-8 (1994).

Quesnel, H., Brossard, L., Valancogne, A. & Quiniou, N. Influence of some Sow characteristics on within-litter variation of piglet birth weight. Animal 2(12), 1842–1849. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175173110800308X (2008).

Lippi, I. C. C. et al. Effects of music therapy on neuroplasticity, welfare, and performance of piglets exposed to music therapy in the intra- and extra-uterine phases. Animals 12(17), 2230. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12172211 (2022).

Zebunke, M., Langbein, J., Manteuffel, G. & Puppe, B. Autonomic reactions indicating positive affect during acoustic reward learning in domestic pigs. Anim. Behav. 81(2), 481–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.11.023 (2011).

Li, X. et al. Behavioural responses of piglets to different types of music. Animal 13(11), 2411–2417. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731119000260 (2019).

Quiniou, N., Brossard, L. & Quesnel, H. Impact of some sow’s characteristics on birth weight variability. Parity 3, 4–6 (2007).

Vargas, L. B. et al. Environmental enrichment strategies for weaned pigs: welfare and behavior. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 24(3), 248–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2021.1967753 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank SOLLA S.A. – Colombia, and the QUIRON Research Group of the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation, MINCIENCIAS, Government of Colombia; University of Antioquia, and SOLLA S.A. —Agreement 890 – Strengthening CTeI in Public Higher Education Institutions - Mechanism 3, code 2021 − 1091.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. Conceptualization: JMZ, NAH, PBC, and BR; Data curation: JMZ, NAH, and DVT; Funding acquisition: BR; Investigation: JMZ, PBC, BR, and NAH; Methodology: PBC and DVT; Project administration: BR; Resources: BR and JMZ; Supervision: DVT; Visualization: DVT; Writing– original draft: JMZ, BR, PB, and NAH; Writing– review & editing: JMZ and DVT. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The project has the ethical approval of the Animal Experimentation Committee of the University of Antioquia, Colombia (Act 129, 2021).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Montoya-Zuluaga, J., Álvarez-Hernández, N., Betancourth-Chaves, P. et al. Musical stimulation in lactating sows affects pre-weaning piglet mortality and maternal behavior. Sci Rep 16, 4049 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34051-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34051-x