Abstract

Potato is highly susceptible to phytopathogens such as Dickeya solani, Pectobacterium atrosepticum and P. carotovorum, which cause an oxidative stress in the vegetal tissues, promote necrosis, and ultimately compromise postharvest quality. In many Gram-negative bacteria, virulence is regulated by quorum sensing (QS) via N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs). Quorum quenching (QQ), the enzymatic degradation of AHLs, has emerged as a promising biocontrol strategy. This study evaluated the biocontrol potential of two halotolerant bacterial strains, Pseudomonas kilonensis B34 and Psychrobacter sp. B38, capable of partially degraded AHLs produced by these phytopathogens. Co-cultures of these QQ strains with the mentioned pathogens significantly reduced tissue maceration in potato tubers, with strongest protective effect observed against D. solani. Under this biotic stress, both strains enhanced antioxidant defense responses in potato tissues, with strain B38 demonstrating the highest effectiveness. This protection was related with higher levels of phenolic compounds, which supported the antioxidant machinery and preserved tissue integrity. Overall, these results highlight the potential of halotolerant QQ bacteria as efficient biocontrol agents and sustainable alternatives to chemical treatments in potato disease management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The agricultural sector plays a fundamental role in ensuring human sustenance and driving socio-economic development worldwide1. The global population is projected to reach 9.7 billion by 2070 and may approach 10 billion by 21002. The global demand for food is undeniable, being one of the most significant problems of developing countries. Consequently, food production will need to increase by approximately 70% to meet future demands3. Nevertheless, the prevailing model of intensive agriculture, which heavily depends on synthetic fertilizers and chemical pesticides, has raised numerous environmental and health-related concerns. The excessive use of agrochemicals has led to soil degradation, salinization, eutrophication of aquatic ecosystems, loss of biodiversity, and the development of pesticide-resistant pests and pathogens4. In addition, the accumulation of chemical residues in food products poses significant risks to human health5.

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is one of the most important crops in the world, ranking as the fourth most consumed food crop globally after rice, wheat, and maize6. Its broad adaptability to a diverse climatic and soil conditions makes it a valuable crop for both subsistence and commercial farming systems. In many regions, potato plays a key role in ensuring food security, poverty alleviation, and promoting rural development. Despite its significance, potato cultivation faces numerous challenges, particularly from pests and diseases, which are estimated to cause losses of 30–70% in both yield and quality. These losses are attributed to a wide variety of pest, including bacterial pathogens7. These pests not only reduce crop productivity but also increase use of chemical pesticides, raising environmental concerns and production costs.

Among the different phytopathogenic bacteria that affect potato crops, certain species highlight due to their significant contribution to global economic losses. These include Pectobacterium atrosepticum8, P. carotovorum9 and other soft rot Enterobacteriaceae10, which are responsible for diseases such as blackleg and soft rot. These necrotrophic infections lead to extensive tissue degradation and reduced tuber quality by disrupting both the enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant activities in vegetable tissues11,12.

Given these impacts, there is an urgent need to develop and implement more sustainable agricultural practices that reduce chemical inputs while enhancing plant health and protection against pathogenic bacteria13,14. One of the most promising approaches in this context is the use of biocontrol strategies based on the interference of quorum sensing (QS)15. QS is a type of microbial intercellular communication system through which bacteria coordinate gene expression and collective behaviours in response to population density. This mechanism is mediated through the production, release and detection of specific signal molecules, such as N-acylhomoserine lactones (AHLs) produced primarily by Gram-negative bacteria. QS regulates the expression of different phenotypes, including biofilm formation, antibiotic production, exoenzyme synthesis, siderophore production and motility16. Several of these traits have been identified as key virulence factors in phytopathogens17. In the case of the phytopathogens D. solani, P. atrosepticum and P. carotovorum, QS plays a critical role in regulating virulence factors18,19,20,21.

QQ involves the enzymatic degradation or modification of AHL molecules through three main types of enzymes: acylases, lactonases and oxidoreductases22. A particularly advantageous aspect of QQ is that it does not directly inhibit bacterial growth, consequently it minimizes the selective pressure for the development of antibiotic resistance23.

This study aims to characterize and evaluate the QQ activity of two halotolerant bacterial strains isolated from a hypersaline environment in southern Spain. The research investigates their potential to attenuate the virulence of three potato pathogens and examines their effects on oxidative metabolism in the vegetable tissue. By disrupting QS systems, these bacterial strains may offer a promising and environmentally sustainable approach for controlling pathogen-induced infections.

Result and discussion

Recent global efforts have highlighted the need for innovative approaches to plant protection, given the limitations of traditional methods. Over the past decades, QQ has gained recognition as a sustainable alternative for combating phytopathogens. QQ is particularly advantageous, as it reduces reliance on chemical pesticides and disrupts bacterial communication rather than directly eliminating pathogens, which may help minimize the risk of resistance development15,24,25.

In this context, this study evaluated the QQ activity of the two halotolerant strains, Pseudomonas kilonensis B34 and Psychrobacter sp. B38, and investigates their potential to reduce the virulence of the three major potato pathogens Pectobacterium atrosepticum, P. carotovorum and Dickeya solani, all of which are responsible for significant economic losses in potato production. Strains B34 and B38 were previously selected due to their demonstrated capacity to degrade C10-HSL, identified during an initial screening of 25 bacterial strains isolated from a hypersaline environment.

Characterization of the AHL degrading activity of strains B34 and B38

The QQ activity of strains B34 and B38 was initially assessed based on their ability to degrade a wide range of synthetic AHLs, using a well-diffusion agar-plate assay with various biosensor strains. The results indicated that both strains completely degraded C8-HSL, C10-HSL, 3-OH-C10-HSL, C12-HSL and 3-oxo-C12-HSL as AHLs, as evidenced by the lack of biosensor activation. In contrast, C6-HSL was only degraded by strain B34 (Fig. 1a). Previous studies have proposed that QQ could operate by recycling or degrading AHLs by bacteria itself26. Importantly, no AHL production was detected from either strain under our assay conditions, ruling out interference from endogenous AHLs (Fig. S3).

(a) Detection of AHL-degrading activity using a well-diffusion agar-plate assay with the biosensors C. subtsugae CV026, C. violaceum VIR07 and A. tumefaciens NTL4 (pZLR4) against synthetic AHLs. Supernatants were obtained from 24 h cultures of strains B34 and B38 grown in LB medium supplemented with 10 µM of each synthetic AHL. Controls consisted of cell-free LB medium supplemented with the same concentration of each AHL. (b) Functional characterization of potential gene with AHL-degrading activity of strain B38 in E. coli DH5α. Detection of remaining C10-HSL and C12-HSL by well-diffusion agar-plate assay using the biosensors VIR07 and NTL4 of the protein No. WP_346716607.1. “Penicillin acylase family protein”. Controls consisted of strain B38 culture and cell-free LB medium supplemented with 10 µM of each AHL.

To investigate whether the observed enzymatic activity was attributable to an AHL lactonase, overnight cultures of strains B34 and B38 were incubated with C10-HSL and C12-HSL, and the resulting supernatants were acidified to pH 2. If a lactonase enzyme were involved, the opened lactone ring of AHL molecules would be expected to restructure itself under acidic conditions27. However, the AHL concentration detected under acidic conditions remained similar to those measured at neutral pH in both cases, as assessed by well-diffusion agar-plate assay. This finding was further confirmed by HPLC-MRM analysis (Fig. S1a), suggesting that the QQ activity of both strains is unlikely to be mediated by a lactonase enzyme.

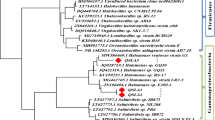

To identify the enzyme responsible for the QQ activity in Psychrobacter sp. B38, genome analysis revealed a gene annotated as encoding an acylase (accession number WP_346716607.1), consisting of 815 amino acids. The corresponding gene (~ 2500 bp) was successfully amplified using specifically designed primers, purified and ligated in the pGEM-T vector, which was then transformed into E. coli DH5α. The resulting recombinant plasmid, pGEMT::B38acylase, demonstrated QQ activity against C10-HSL and C12-HSL in a well-diffusion agar-plate assay (Fig. 1b). This finding is consistent with previous reports of AHL-degrading acylases in Psychrobacter species28.

Since the genome of strain B34 has not been sequenced, comparative analysis was performed in the available genomes of related P. kilonensis strains BS3780 and DSM 13647. Two putative acylase-encoding genes were identified, corresponding to accession numbers SEE64333.1 (annotated as “acyl-homoserine-lactone acylase”) and WP_053188614.1 (annotated as “bifunctional acylase PvdQ”) consisting of 784 and 782 amino acids respectively). Specific primers were designed based on these sequences (see Method section). The PCR fragments obtained (~ 2300 bp) were cloned and expressed in E. coli, but none of them exhibited detectable QQ activity. Notably, AHL acylases have been identified in other Pseudomonas species, including P. aeruginosa PAO129, P. segetis P630, P. fluorescens PF0831, P. halotolerans B2232 and P. multiresinivorans QL-9a33. In general, AHL acylases preferentially degrade long-chain AHLs and exhibit greater substrate specificity than AHL lactonases34. Notably, strain B34 was capable to degrade a wide range of AHLs.

The cellular localization of QQ activity was evaluated by assessing C10-HSL degradation in both the cell-free supernatant (SN) and crude cellular extract (CCE) of strains B34 and B38. A well-diffusion agar-plate assay using C. violaceum VIR07 showed QQ activity only in the SN fractions for both strains, whereas no AHL degradation was observed in CCE fractions (Fig. S1b). These results suggest that the QQ enzymes are secreted as previously showed by other authors35. Interestingly, Nain et al.36 reported that while lactonases may be cytoplasmic, AHL acylases are often periplasmic.

QS interference in potato phytopathogens by in vitro co-culture assays

The capacity of strains B34 and B38 to degrade AHLs produced by the major potato phytopathogens D. solani LMG 25,993T, P. atrosepticum CECT 314T and P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum CECT 225T was firstly evaluated through in vitro co-cultures assays. Previously, antagonist assays confirmed that strains B34 and B38 did not interfere with the growth of any of the tested pathogens, as no inhibitory effect was shown (Fig. S2).

For the co-culture experiments, pathogens were grown in the presence of strains B34 and B38 for 24 h and the initial concentration of each bacterium was maintained throughout the experiment. The remaining AHLs in each case were detected using NTL4 and CV026 as biosensors. As shown in Fig. S3, strain B34 partially degraded the AHLs produced by the three pathogens. In all cases, no activation of CV026 was observed, while the biosensor NTL4 was activated to lesser extend compared to the control. Similarly, strain B38 exhibited partial degradation of AHLs, as indicated by the reduced activation of both biosensors relative to the control samples. An exception was observed for NTL4, which showed no activation when exposed to AHLs from D. solani-B38 cocultures.

These results indicated that both strains, B34 and B38, were capable of partially degrading the AHLs produced by D. solani, P. atrosepticum and P. carotovorum, with strain B34 showing higher efficiency. In agreement with our observations using synthetic AHLs, strain B34 was able to degrade a broader range of AHLs than strain B38 (Fig. 1). This is consistent with previous studies reporting that Bacillus toyonensis AA1EC137 and P. halotolerans B2232 also partially degrade AHLs produced by the same pathogens, thereby interfering with their QS systems.

Virulence suppression in potato slices and modulation of pathogen virulence factors

To evaluate whether QS interference by strains B34 and B38 impacts the virulence of major phytopathogens, potato tuber slice assays were conducted. These experiments aimed to assess the protective potential of the strains and support their application as biocontrol agents.

Potato slices inoculated with D. solani monoculture showed typical soft rot symptoms, with a large tissue maceration area (65.38 ± 3.21%) (Fig. 2). In contrast, co-cultures with strains B34 and B38 significantly reduced the tissue maceration area to 7.47 ± 1.40% and 2.97 ± 0.47%, respectively. Similarly, co-cultures of strains B34 and B38 with P. atrosepticum reduced tissue maceration (3.56 ± 0.06% and 9.66 ± 3.06%, respectively) compared with potatoes infected with monocultures of P. atrosepticum (26.09 ± 2.32%). However, in assays with P. carotovorum, co-cultures of strains B34 and B38 with the pathogen did not significantly reduce infection symptoms. Potato slices inoculated with P. carotovorum showed a maceration area of 40.58 ± 3.20%, while maceration in B34 and B38 co-cultures was 38.90 ± 0.75% and 41.26 ± 0.90 respectively (Fig. 2).

(a) Virulence and maceration of monocultures and co-cultures of strains B34 and B38 and the pathogens D. solani, P. atrosepticum and P. carotovorum on potato slices. Sterile water was used as a negative control. (b) Percentage of maceration area on potato slices. Groups represent inoculation with the corresponding pathogen (D. solani, P. atrosepticum and P. carotovorum) and co-cultures of strains B34 and B38 and the pathogens. Controls are no represented as no maceration was observed. Data are means ± SD of three independent experiments performed on four potato slices. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically differences according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

The results demonstrate that strain B34 reduced soft rot symptoms caused by D. solani and P. atrosepticum by 88.58% and 86.35%, respectively, while strain B38 achieved reductions of 95.46% and 62.97%. The marked decrease in symptoms caused by D. solani in the presence of strain B38 may be associated with the high level of AHL degradation previously observed (Fig. S3). Nevertheless, neither strain mitigated the virulence of P. carotovorum. It is important to highlight that B34 and B38 strains did not cause any symptoms in potatoes slices when inoculated alone, emphasizing their safety for agriculture use (Fig. 2). Additionally, the stability of bacterial cell counts throughout the assay indicates that the observed reduction in maceration was not due to the growth inhibition of the pathogens but rather to interference with their virulence mechanisms. Similar reductions in soft rot symptoms have been reported by Rodríguez et al.30, who demonstrated that P. segetis P6 decreased maceration caused by D. solani and P. atrosepticum in co-culture assays. This protection was not only observed in potato, but also with carrot slices and tomato fruits against Pantoea agglomerans in co-culture with P. segetis P6 and B. toyonensis AA1EC138.

Given the higher protective effect observed against D. solani, this pathogen was selected for further analysis of virulence-related traits modulated by QS. Alkaline phosphatase and lecithinase activity in D. solani were inhibited when co-cultured with strain B34. Caseinase activity of D. solani was inhibited in co-culture with strain B38 (Fig. S4). Further phenotypic analyses of D. solani could not be conducted as both strains B34 and B38 showed high endogenous enzymatic activity, that interfered with the assays. Previous studies have demonstrated that degradation of AHL signals, either through heterologous expression of QQ enzymes or by co-cultivation with AHL-degrading bacteria, often leads to decreased enzymatic activity and reduced virulence in the pathogens mentioned in this study, D. solani, P. atrosepticum and P. carotovorum32,37,39,40 and other pathogens such as P. agglomerans38 and Xanthomonas campestris41. In particular, P. segetis P6 has demonstrated QQ activity against relevant phytopathogens30,38, and Psychrobacter strains have been reported to disrupt QS and biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa28,42.

The reduction in pathogen virulence observed in this study strongly suggests that strains B34 and B38 interfere with QS-regulated pathogenicity, most likely through AHL degradation, although additional mechanisms contributing to this effect remain to be elucidated. These results highlight their potential use as effective biocontrol agents for crop protection. Moreover, the fact that virulence of the pathogens was reduced without interfering the growth of the pathogen tested aligns with previous studies that suggest QQ targets communication pathways instead of essential bacterial functions43,44, supporting the interpretation of our data.

Evaluation of parameters of oxidative and phenolic metabolism

Following the observed reduction in D. solani virulence in potato slices inoculated with bacterial co-cultures, we studied associated changes in oxidative metabolism in the vegetal tissue. Among the analysed parameters, particular attention was given to the polyamine putrescine, a key molecule involved in several cellular regulatory processes, including programmed cell death45. Our results showed a significant increase in putrescine content in potato tissues inoculated with D. solani, indicating a possible link between bacterial infection and altered metabolism of this polyamine. On the contrary, this increase was not observed in potato tissues inoculated with co-cultures of strains B34 and B38, obtaining values comparable to control treatment (Fig. 3a). The most notable reduction was observed in samples inoculated with the D. solani-B38 co-culture. Although we did not find preceding assays on potatoes, earlier studies have outlined an increase in the levels of polyamines in plants in interaction with pathogens. Previous research confirmed that the increase in polyamine levels can occur during the early stages of infection by phytopathogens, which can influence both plant defense and pathogen virulence. The synthesis of polyamines is activated, leading to increased accumulation of compounds like putrescine in tomato46 or Arabidopsis thaliana plants inoculated with P. syringae pv. tomato47. PGP bacteria contribute to maintaining polyamine homeostasis under pathogenic stress by modulating hormone balance and defense signaling against Dickeya species, thereby suppressing excessive stress responses48,49. These results suggest that the accumulation of putrescine may form part of the plant’s defense response to pathogen infection, a response that appear attenuated or absent in the presence of halotolerant bacteria in co-culture.

Changes in the content of polyamine putrescine (a), FRAP (b) and TEAC (c) in potato treated with sterile water (control), monocultures and co-cultures of strains B34 and B38 and the pathogen D. solani. Data are means ± SD of three independent experiments. Each treatment was conducted in four replicates. Different letters indicate statistically differences according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

The antioxidant capacity of potato tissues was evaluated using ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) and Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) assays. Both tests showed significant differences among treatments, and the trend observed was opposite to the results for putrescine content. In both assays, co-cultures increased the antioxidant capacity of potato tissue compared with D. solani treatment (Fig. 3b and c). Notably, the D. solani-B38 co-culture exhibited the highest antioxidant capacity, even in FRAP showing higher values than control treatment. Neshat et al.50 confirm that inoculation with PGP bacteria activates antioxidant pathways in plants, increasing the levels of antioxidant enzymes and compounds that are quantified by FRAP and TEAC assays. Additionally, previous studies have reported that the high antioxidant capacity of potato is related to the high content of polyphenols, which blocks oxidation and activates other antioxidants mechanisms51,52. This coincides with the results of our study, in which the higher levels of phenols detected corresponded to the treatments with higher antioxidant capacity (Fig. 5a).

The inoculation of bacteria with QQ activity, which increased the antioxidant capacity of plant tissue, could help mitigate the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) during pathogen infection. Under biotic stress plant commonly produce ROS such as H2O2, which can cause damage to plant cell membranes and macromolecules53. H2O2 can be produced in plants in the apoplast or different cytoplasmatic organelles (peroxisome, mitochondria and chloroplasts) through enzymes such as superoxide dismutase or through processes such as transport electron chain, β-oxidation of fatty acid and photorespiration54. After having analysed the levels of H2O2 in potato tissues, we observed a significant decrease in H2O2 content with QQ bacteria in comparison to the potato treated with D. solani, more obvious with B38 strain inoculation (Fig. 4a). Therefore, oxidative damage in potatoes inoculated with co-cultures could be less than potatoes infected only with the pathogen. Previous studies demonstrated that the inoculation of Pseudomonas spp. and other PGP bacteria reduce hydrogen peroxide accumulation, improving potato defense and reducing disease severity during Dickeya infection55. Superoxide anion (O2−) is also a ROS produced in plants under stress conditions53. Superoxide anion radical scavenging capacity changed significantly among the different treatments (Fig. 4b). No significant differences were observed between the control treatment and those treated with strains B34 and B38. However, in potatoes inoculated only with the pathogen, this capacity was reduced by around 80%. Comparing all the samples inoculated with D. solani, the co-cultures showed greater superoxide anion inhibition, especially with the strain B38. This increase in superoxide anion inhibition suggests that the inoculation of bacteria with QQ activity has triggered the tuber’s defence mechanisms against oxidative damage. This is also confirmed with the data observed for superoxide dismutase activity (SOD), which is also considered an important protection mechanisms against oxidative damage. This antioxidant activity increased drastically with the inoculation of strains B34 and B38 reaching values from 0.8 to 1.1 U/mg prot min even in co-cultures with the pathogen, whereas in the potatoes inoculated only with D. solani, a value of around 0.2 U/mg prot min was observed (Fig. 4c). Previous experiments also studied the SOD enzyme and found that its activity increased in plants treated with biocontrol agent-pathogen co-cultures56,57. The application of PGP bacteria increases SOD activity in potatoes under Dickeya pathogen stress, supporting plant health by mitigating oxidative damage58. Furthermore, recent research with the PGPB Serratia plymuthica A30 in potato tubers co-inoculated with D. solani showed transcriptomic upregulation of antioxidant enzyme genes, including SOD, which forms part of the biocontrol mechanism against soft rot59.

Changes in the content or activity of H2O2 (a), superoxide anion scavenging (b) and superoxide dismutase (c) in potato treated with sterile water (control), monocultures and co-cultures of strains B34 and B38 and the pathogen D. solani. Data are means ± SD of three independent experiments. Each treatment was conducted in four replicates. Different letters indicate statistically differences according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Phenolic compounds are a major class of plant secondary metabolites, which are essential for plant growth and development. While some are produced constitutively, others are induced under biotic and abiotic stresses. Phenols have a key role as antioxidants, reducing oxidative damage in plants by scavenging ROS60. We analysed the levels of total free phenols in the different treatments. In potatoes inoculated only with the pathogen, total free phenols decreased by nearly half compared to control treatment. However, the treatment with strains B34 and B38 significantly increased total free phenols, even in the co-cultures, where we detected a higher content of these antioxidant compounds than in the control treatment and highlighting that the increase with B38 co-culture was the highest (Fig. 5a). Philip et al.56 also reported that the biocontrol agent-pathogen co-culture increased the content of total phenolic compounds. Moreover, Sorahinobar et al.57 proposed that the increase observed may act as signalling molecules and induce resistance in plants. Transcriptomic analysis showed that inoculation with the PGPB S. plymuthica A30 in potatoes infected with D. solani led to upregulation of polyphenol biosynthesis59. On the contrary, guaiacol peroxidase (GPX) activity exhibited the highest values in the samples that contained only D. solani. However, the activity notably decreased in co-cultures with strains B34 and B38 (Fig. 5b). GPX is an enzyme that prefers aromatic compounds as electron donors and is related to the oxidation of phenolic compounds61. The induction of this activity could explain the lower levels of free phenols observed in this treatment, since GPX is an enzyme that oxidates phenols. Therefore, potatoes inoculated with strains B34 and B38, which exhibited higher free phenol content, showed reduced GPX activity. A decrease in guaiacol peroxidase with PGP bacteria has been previously observed suggesting that bacterial inoculation effectively reduces plant stress62. Thus, by scavenging H2O2 and oxidizing phenols, GPX activity supports lignification, suberization, and other defence barriers that restrict pathogen spread. Polyphenol oxidase (PPO) is another key enzyme involved in the oxidation of phenolic compounds. PPO catalyses the oxidation of phenols and produces ROS and quinones61, followed by the transformation of the quinones to dark pigments that result in the browning of vegetable tissues such as potatoes63. In our assays we found the higher PPO activity in potatoes tissues infected solely with D. solani. In contrast, PPO activity in samples inoculated with the B34 and B38 co-cultures was comparable to that of the control (Fig. 5c). These biochemical results were consistent with phenotypic observation from of Fig. 2, where potatoes inoculated with both co-cultures exhibited noticeably reduced maceration and browning compared to those inoculated with D. solani alone. This effect was particularly evident in the B38 coculture, where the appearance of the potato tissue closely resembled that of the control.

Changes in the content or activity of total free phenols (a), guaiacol peroxidase (b) and polyphenol oxidase (c) in potato treated with sterile water (control), monocultures and co-cultures of strains B34 and B38 and the pathogen D. solani. Data are means ± SD of three independent experiments. Each treatment was conducted in four replicates. Different letters indicate statistically differences according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the halotolerant strains Pseudomonas kilonensis B34 and Psychrobacter sp. B38 exhibit QQ activity that reduce the virulence of phytopathogens in potato tissues, with the most pronounced effect observed against D. solani. Both strains enhance the antioxidant defence system in potato tubers infected by D. solani, with strain B38 triggering the strongest protective response against oxidative stress. This protection is associated with the suppression of PPO and GPX activities, contributing to the maintenance of higher phenolic compounds levels, supporting the potato’s antioxidant machinery and preserving tissue integrity and quality. Notably, unlike many conventional biocontrol agents, these strains confer protection without relying on antibiotic production.

Methods

Bacterial strains, media, compounds and culture conditions

The strains Pseudomonas kilonensis B34 and Psychrobacter sp. B38 selected for this study, were previously isolated from the rhizosphere and phyllosphere, respectively, of the Salicornia hispanica plant collected from El Saladar de El Margen, Cúllar, Granada (37° 38’ 50.6’’N, 2° 37’ 22.2’’ W). The plant bacterial pathogens used in the study included Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum CECT 225T, P. atrosepticum CECT 314T and Dickeya solani LMG 25993T. Strains B34 and B38, as well as the pathogens, were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) or tryptic soy broth (TSB) media. The biosensor Chromobacterium subtsugae CV02664 was employed to detect C4- to C8-HSL, while C. violaceum VIR0765 was used for C10- and 3-OH-C10-HSL. Agrobacterium tumefaciens NTL4 (pZLR4)66 was used to detect C8- to C12-HSL. VIR07 and CV026 were grown in LB medium, whereas NTL4 was cultured in LB medium supplemented with 2.5 mmol L− 1 CaCl2 × 2H2O and 2.5 mmol L− 1 MgSO4 × 7H2O (LB/MC) or Agrobacterium broth (AB) medium67. All the strains were grown at 28 °C and 120 rpm in a rotary shaker. Antibiotics kanamycin (Km) and gentamicin (Gm) were used at final concentrations of 50 mg mL− 1 when necessary.

The following synthetic AHLs (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, USA) were used: C6-HSL (N-hexanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone), 3-O-C6-HSL (N-3-oxo-hexanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone), C8-HSL (N-octanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone), 3-O-C8-HSL (N-3-oxo-octanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone), C10-HSL (N-decanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone), 3-OH-C10-HSL (N-3-hydroxydecanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone), C12-HSL (N-dodecanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone) and 3-O-C12-HSL (N-3-oxo-dodecanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone).

Quorum quenching activity against synthetic AHLs

The QQ activity of strains B34 and B38 against synthetic AHLs was analysed by the well-diffusion agar-plate assay outlined by Torres et al.68. In this assay, each AHL was added to an overnight culture of strains B34 or B38 at a final concentration of 10 µM and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h. As a negative control, cell-free LB medium supplemented with the same concentration of AHLs was used. The remaining AHLs were detected by placing 100 µL of the supernatant from each sample onto LB agar plates overlaid with C. subtsugae CV026 or C. violaceum, or onto AB agar plates supplemented with 80 µg mL− 1 of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-ß-D-galactopyranoside (Xgal) overlaid with A. tumefaciens NTL4 (pZLR4). After 24 h of incubation at 28 °C, the presence of purple or blue coloration around the wells indicated the presence of remaining AHLs. This assay was repeated three times for validation.

AHL production of strains B34 and B38 was analyzed by a well-diffusion agar plate assay as described above.

Characterization and location of the AHL degrading enzyme

For the identification of the type of QQ enzyme of strains B34 and B38, an acidification-based assay was performed27. Summarily, C10-HSL and C12-HSL were added to an overnight culture of strain B34 or B38 and incubated for 24 h at 28 °C. Sterile LB medium supplemented with the same concentration of the corresponding AHL served as the negative control. Afterwards, the supernatant was acidified to pH 2 using HCl 1 N and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h. The remaining AHLs were detected using the well-diffusion-agar plate method with C. violaceum VIR07 and A. tumefaciens NTL4 (pZLR4) as biosensors. In addition, the remaining amount of C10-HSL and C12-HSL was extracted twice with 1 volume of dichloromethane. Dried extracts were resuspended in acetonitrile and analysed by HPLC/HRMS68.

The cellular localization of QQ activity was assessed by measuring the enzymatic activity using the previously described well-diffusion agar-plate assay in both the crude cellular extract (CCE) and in the supernatant fractions obtained from 24 h cultures of strains B34 and B38. The CCEs were prepared by centrifugation of the cultures, resuspension of the resulting cell pellet in PBS buffer (pH 6.5), and then, sonication of the suspension for 5 min. The resulting CEEs and supernatants were subsequently filtered through a 0.22 μm-pore membrane filter69.

The identification of AHL-degrading genes was carried out through in silico analysis of the annotated genomes for both strains. For strain B34, annotated genomes of P. kilonensis BS3780 (GCF_900105635.1) and P. kilonensis DSM 13647 (GCF_001269885.1) were used as template, and putative acylase encoding genes were selected (protein SEE64333.1 “acyl-homoserine-lactone acylase” and protein WP_053188614.1 “bifunctional acylase PvdQ”) and used to design the following primers: SEE64333.1-Fw 5’-gtgagaatgtccgtgcag-3’ and SEE64333.1-Rev 5’-ttattgcgtcgccaccctgcc-3’; WP_053188614.1-FW 5’-atgtccgtgcagttatcgagg-3’ and WP_053188614.1-REV 5’-ttattgcgtcgccaccctgccc-3’. For strain B38, the genome was annotated using RAST server and deposited as NZ_JBDKWD010000002.1, and a gene encoding a putative acylhomoserine lactone acylase (WP_346716607.1 “Penicillin acylase family protein”) was identified based on sequence homology. Specific primers were designed: B38-acilgen-FW 5’-atgagcattcaagtgcttaatcg-3’ and B38-acilgen-REV 5’-ctattctcttaattgaacc-3’). The PCR fragments were purified and cloned into the pGEM-T cloning vector (Promega). The constructs were subsequently transferred into Escherichia coli DH5α, and AHL-degradation activity was tested in LB media supplemented with IPTG and AHLs (C10-HSL and C12-HSL) as described earlier.

Antagonist assay

The antagonist activity of strains B34 and B38 was assessed by using the well-diffusion method70. A 24 h culture of each pathogen was overlaid on LB agar plates, and 100 µL aliquots of the filtered supernatant from a 5-day culture of strains B34 and B38 were placed on the previous wells overlaid with pathogens. The plates were incubated at 28 °C for 48 h, and the presence of growth inhibition halos around the wells was evaluated.

Interference with the QS system of phytopathogens by co-culture assays

Co-culture assays involving phytopathogens and strains B34 and B38 were conducted following the methodology outlined by Torres et al.71 and Rodríguez et al.30. Concisely, 107 CFU mL− 1 of each pathogen was co-cultured with 109 CFU mL− 1 of strains B34 and B38 in LB medium and incubated 24 h at 28 °C. Negative controls were prepared using a similar concentration of each strain in sterile LB medium. The remaining AHLs from the different co-cultures were quantified in conformity with the well-diffusion agar-plate method using NTL4 and CV026 as biosensors. The bacterial abundance in the co-culture was assessed through serial dilutions and plate counting on TSA medium. For differentiating colonies with similar morphologies, double plate counts were performed, using TSA and King B as selective media for strain B34 and LB agar supplemented with 7.5% (w/v) NaCl as selective medium for strain B38. The assays were repeated three times.

The interference of strains B34 and B38 with virulence-associated cellular functions regulated by QS in the pathogens was evaluated by spotting 10 µL aliquots of 24 h mono- and co-cultures onto specific media. The following phenotypic activities, known to be present in D. solani but absent in strains B34 and B38, were analyzed: alkaline phosphatase72 and the production of hydrolytic enzymes, including caseinase73 and lecithinase74. After a 5-day incubation period, activity was considered positive when a clear halo was observed surrounding the bacterial growth. The bioassays were repeated at least three times.

Virulence assays in potato slices and determination of parameters of oxidative and phenolic metabolism

The ability of strains B34 and B38 to mitigate soft rot caused by P. atrosepticum CECT 314T, P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum CECT 225T and D. solani LMG 25993T was tested on potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) slice assays as described in previous studies30,75. Briefly, whole potatoes were washed, surface-sterilized with ethanol, sliced, and then, placed in Petri dishes. Co-cultures of strains B34 or B38 with the pathogens (100:1 ratio) were centrifuged, resuspended in sterile water and 15 µL of the mixture was inoculated onto potato slices via three equidistant incisions. Controls included sterile water, and monocultures of each bacterium. Each treatment was conducted in four replicates, and each assay was repeated three times. Potatoes were incubated at 28 °C for 2–3 days, depending on the pathogen, after which the maceration area was visually examined, and the extent of tissue damage was quantified via image analysis using ImageJ software.

After the incubation period, potatoes inoculated with mono and co-cultures of D. solani were processed using liquid nitrogen, a part of the material was stored at − 80 °C, and the rest was lyophilized. The following parameters were measured:

Putrescine content: Putrescine was extracted from lyophilized material with 5% (v/v) cold perchloric acid containing diaminoheptane as internal standard. The homogenate was centrifuged (3000 x g, 5 min, 4 °C) and 0.2 mL of the supernatant was used for free putrescine determination. Samples were reacted with dansyl chloride and sodium carbonate, incubated overnight in darkness, and excess reagent was quenched with proline. Dansylated putrescine was extracted with toluene, evaporated, and redissolved in acetonitrile. Finally, putrescine was separated by HPLC on a C18 column and quantified using a fluorescence detector (415/510 nm) following Flores and Galston76.

Antioxidant capacity of the potato tissue: Lyophilized material was homogenized in acetone and centrifuged at 3500 x g for 15 min at 4 °C. Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay (FRAP) was done according to Benzie and Strain77 with some modifications. Potato extracts were allowed to react with FRAP solution [0.3 M acetate buffer pH 3.6, 0.01 M TPTZ (2, 4, 6-tripyridyl-s-triazine) in 0.04 M HCl, and 0.02 M FeCl3·6H2O (10:1:1, v/v/v)] for 30 min in the dark condition at 37 °C. Readings of the colored product were then taken at 595 nm. The Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) of extracts was estimated by the ABTS+ radical cation decolorization assay following the method of Re et al.78, with modifications. The ABTS reagent (7 mM ABTS in 20 mM potassium acetate buffer pH 4.5) after 16 h of incubation was mixed with the potato extract. After 1 h of incubation, its absorbance was measured at 734 nm. The percentage of inhibition of the formation of the radical cation ABTS by the antioxidant sample was calculated by means of a Trolox standard curve.

Hydrogen peroxide content: The hydrogen peroxide was assayed spectrophotometrically by the procedure previously described by Alexieva et al.79. Potato was ground in liquid nitrogen and homogenized with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (1:4, w/v). After centrifugation at 4 °C and 12,000 x g for 15 min, the supernatant was collected. The reaction mixture consisted of 0.25 mL supernatant, 0.25 mL 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7) and 1 mL 1 M KI. The reaction was developed for 1 h in darkness and absorbance measured at 390 nm.

Superoxide anion radical scavenging capacity assay: The superoxide radical anion (O2−) scavenging assay was conducted as described by Green and Fellman80 with modifications. Reaction mixture was made by adding to 0.1 mL of sample the following reagents: 0.1 mL of methionine (10 mM), 0.05 mL of 0.8 mM nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT), 0.05 mL of 5 mM riboflavin and 1.75 mL of 65 mM phosphate-biphosphate buffer (pH 7.8). Radical production was initiated by illuminating the samples with an 800 W halogen lamp for 20 min. Finally, nitroblue formazan was quantified spectrophotometrically at 560 nm. Results were expressed as scavenging activity (%).

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity: For the analysis of this enzymatic activity, the potato tissue ground in liquid nitrogen was homogenized in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.8 containing 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 10% (w/v) insoluble polyvinylpolypyrrolidone. The homogenate was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min (4 °C) and the resulting supernatant was used to determine enzymatic activity. SOD activity was analysed by measuring its ability to inhibit the photochemical reduction of nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) following Beyer and Fridovich81.

Free phenolic compounds content: Phenols were determined following the protocol described by Singleton et al.82 with modifications. The lyophilized potato sample was extracted with acetone 80% (v/v) in darkness for 30 min at 4 °C and centrifuged at 8000 x g for 10 min at 4 °C. Finally, the phenolic content of the supernatant was determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu method.

Guaiacol peroxidase (GPX) and Polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity: These enzymatic activities were determined following the protocol described by Castro-Cegrí et al.83 with modifications. Potato tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen and homogenized with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.5. Homogenates were centrifuged for 20 min at 4 °C and 20,000 x g, and supernatant proteins were precipitated with ammonium sulphate at 100% saturation. Precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation for 15 min at 4 °C and 15,000 x g, resuspended in 3 mL of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.5, and dialyzed at 4 °C in the same buffer. The reaction mixture for PPO activity was composed by 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 6, 20 mM pyrocatechol, and 0.1 mL of protein extract. The increase of absorbance at 410 nm was recorded for 1 min. The reaction mixture for GPX activity was composed by 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.8, 72 mM guaiacol, 118 mM hydrogen peroxide, and 0.1 mL of protein extract. GPX was assayed by measuring absorbance at 470 nm.

Protein determination: Total protein concentration was measured using the Bradford assay84.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 28.0.0 (https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/spss-statistics/28.0.0). Data normality was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk test. Finally, ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey analyses were used to assess the effects of each treatment.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The state of Food and agriculture. Addressing land degradation across landholding scales. https://www.fao.org/publications/fao-flagship-publications/the-state-of-food-and-agriculture/en (2025).

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdf) (2022).

Godfray, H. C. J. et al. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327, 812–818. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1185383 (2010).

Tripathi, S., Srivastava, P., Devi, R. S. & Bhadouria, R. Influence of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides on soil health and soil microbiology. In Agrocemicals Detection, Treatment and Remediation (eds. Narasimha, M., Prasad, V.) 25–54, (Elsevier, 2020).

Beyuo, J., Sackey, L. N. A., Yeboah, C., Kayoung, P. Y. & Koudadje, D. The implications of pesticide residue in food crops on human health: a critical review. Discov Agric. 2, 123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44279-024-00141-z (2024).

Ahmadu, T., Abdullahi, A. & Ahmad, K. The role of crop protection in sustainable potato (Solanum tuberosum l.) production to alleviate global starvation problem: An overview. In Solanum tuberosum - A Promising Crop for Starvation Problem. (eds. Yildiz, M., Ozgen, Y.).

Shi, H., Li, W., Zhou, Y., Wang, J. & Shen, S. Can we control potato fungal and bacterial diseases? Microbial regulation. Heliyon 9, e22390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22390 (2023).

Kergaravat, B. et al. Quorum quenching lactonase alters virulence of Pectobacterium atrosepticum and reduces maceration in potatoes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 72, 26796–26808. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.4c07881 (2024).

Li, B. et al. Effects of Rhapontigenin as a novel quorum-sensing inhibitor on exoenzymes and biofilm formation of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum and its application in vegetables. Molecules 27, 8878. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27248878 (2022).

Marok-Alim, D., Marok, M. A. & Krimi, Z. First detection, identification and characterisation of Dickeya solani-caused potato soft rot in Algeria. Potato Res. 67, 495–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-023-09645-5 (2024).

Márquez-aVillavicencio, M. P., Weber, B., Witherell, R. A., Willis, D. K. & Charkowski, A. O. The 3-hydroxy-2-butanone pathway is required for Pectobacterium carotovorum pathogenesis. Plos One. 6, e22974. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022974 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals differential mechanisms of soft rot resistance in lettuce grown under white and blue light. Food Energy Secur. 14, e70038. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.70038 (2025).

Schneider, K., Barreiro-Hurle, J. & Rodríguez-Cerezo, E. Pesticide reduction amidst food and feed security concerns in Europe. Nat. Food. 4, 746–750. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00834-6 (2023).

Finger, R. & Möhring, N. The emergence of pesticide-free crop production systems in Europe. Nat. Plants. 10, 360–366. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-024-01650-x (2024).

Zhu, X. et al. Innovative microbial disease biocontrol strategies mediated by quorum quenching and their multifaceted applications: A review. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 1063393. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1063393 (2023).

Abisado, R. G., Benomar, S., Klaus, J. R., Dandekar, A. A. & Chandler, J. R. Bacterial quorum sensing and microbial community interactions. mBio 9, e02331–e02317. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02331-17 (2018).

Baltenneck, J., Reverchon, S. & Hommais, F. Quorum sensing regulation in phytopathogenic bacteria. Microorganisms 9, 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9020239 (2021).

Crépin, A. et al. N-acyl Homoserine lactones in diverse Pectobacterium and Dickeya plant pathogens: diversity, abundance, and involvement in virulence. Sensors 12, 3484–3497. https://doi.org/10.3390/s120303484 (2012).

Põllumaa, L., Alamäe, T. & Mäe, A. Quorum sensing and expression of virulence in Pectobacteria. Sensors 12, 3327–3349. https://doi.org/10.3390/s120303327 (2012).

Moleleki, L. N., Pretorius, R. G., Tanui, C. K., Mosina, G. & Theron, J. A quorum sensing-defective mutant of Pectobacterium carotovorum ssp. brasiliense 1692 is attenuated in virulence and unable to occlude xylem tissue of susceptible potato plant stems. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 18, 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/mpp.12372 (2017).

Potrykus, M., Hugouvieux-Cotte‐Pattat, N. & Lojkowska, E. Interplay of classic Exp and specific Vfm quorum sensing systems on the phenotypic features of Dickeya solani strains exhibiting different virulence levels. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 19, 1238–1251. https://doi.org/10.1111/mpp.12614 (2018).

Grandclément, C., Tannières, M., Moréra, S., Dessaux, Y. & Faure, D. Quorum quenching: role in nature and applied developments. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 40, 86–116. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuv038 (2016).

Munguia, J. & Nizet, V. Pharmacological targeting of the host–pathogen interaction: alternatives to classical antibiotics to combat drug-resistant superbugs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 38, 473–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2017.02.003 (2017).

Torres, M., Dessaux, Y. & Llamas, I. Saline environments as a source of potential quorum sensing disruptors to control bacterial infections: A review. Mar. Drugs. 17, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17030191 (2019).

Verma, R. et al. A review article: Anti-quorum sensing agents as a potential replacement for antibiotics in phytobacteriology. J. Pharm. Innov. 10, 121–125. https://doi.org/10.22271/tpi.2021.v10.i11b.9200 (2021).

Katoch, S., Kumari, N., Salwan, R., Sharma, V. & Sharma, P. N. Recent developments in social network disruption approaches to manage bacterial plant diseases. Biol. Control. 150, 104376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2020.104376 (2020).

Yates, E. A. et al. N-acylhomoserine lactones undergo lactonolysis in a pH-, temperature-, and acyl chain length-dependent manner during growth of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 70, 5635–5646. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.70.10.5635-5646.2002 (2002).

Reina, J. C., Romero, M., Salto, R., Cámara, M. & Llamas, I. AhaP, a quorum quenching acylase from Psychrobacter sp. M9-54-1 that attenuates Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Vibrio coralliilyticus virulence. Mar. Drugs. 19, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/md19010016 (2021).

Sio, C. F. et al. Quorum quenching by an n -acyl-homoserine lactone acylase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Infect. Immun. 74, 1673–1682. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.74.3.1673-1682.2006 (2006).

Rodríguez, M. et al. Plant growth-promoting activity and quorum quenching-mediated biocontrol of bacterial phytopathogens by Pseudomonas Segetis strain P6. Sci. Rep. 10, 4121. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61084-1 (2020).

Wang, D. et al. Screening and validation of quorum quenching enzyme PF2571 from Pseudomonas fluorescens strain PF08 to inhibit the spoilage of red sea Bream Filets. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 362, 109476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109476 (2022).

Sánchez, P., Castillo, I., Martínez-Checa, F., Sampedro, I. & Llamas, I. Pseudomonas halotolerans sp. nov., a halotolerant biocontrol agent with plant-growth properties. Front. Plant. Sci. 16, 1605131. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2025.1605131 (2025).

Liu, S. et al. The isolate Pseudomonas multiresinivorans QL-9a quenches the quorum sensing signal and suppresses plant soft rot disease. Plants 12, 3037. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12173037 (2023).

Yu, M., Liu, N., Zhao, Y. & Zhang, X. Quorum quenching enzymes of marine bacteria and implication in aquaculture. J. Ocean. Univ. China. 48, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.16441/j.cnki.hdxb.20170202 (2018).

Romero, M., Martín-Cuadrado, A. B. & Otero, A. Determination of whether quorum quenching is a common activity in marine bacteria by analysis of cultivable bacteria and metagenomic sequences. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 6345–6348. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01266-12 (2012).

Nain, Z. et al. Computational prediction of active sites and ligands in different AHL quorum quenching lactonases and acylases. J. Biosci. 45, 26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12038-020-0005-1 (2020).

Roca, A. et al. Potential of the quorum‐quenching and plant‐growth promoting halotolerant Bacillus toyonensis AA1EC1 as biocontrol agent. Microb. Biotechnol. 17, e14420. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.14420 (2024).

Cruz, A. A., Cabeo, M., Durán-Viseras, A., Sampedro, I. & Llamas, I. Interference of AHL signal production in the phytophatogen Pantoea agglomerans as a sustainable biological strategy to reduce its virulence. Microbiol. Res. 285, 127781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2024.127781 (2024).

Garge, S. S. & Nerurkar, A. S. Attenuation of quorum sensing regulated virulence of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum through an AHL lactonase produced by Lysinibacillus sp. Gs50. PLOS ONE. 11, e0167344. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167344 (2016).

Vega, C., Rodríguez, M., Llamas, I., Béjar, V. & Sampedro, I. Silencing of phytopathogen communication by the halotolerant PGPR Staphylococcus equorum strain EN21. Microorganisms 8 (1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8010042 (2019).

Ye, T. et al. Cupriavidus sp. HN-2, a novel quorum quenching bacterial isolate, is a potent biocontrol agent against Xanthomonas Campestris pv. Campestris. Microorganisms 8 (45). https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8010045 (2019).

Packiavathy, I. A. S. V. et al. V. AHL-lactonase producing Psychrobacter sp. from Palk Bay sediment mitigates quorum sensing-mediated virulence production in gram negative bacterial pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 12, 634593. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.634593 (2021).

Rodríguez-Urretavizcaya, B., Vilaplana, L. & Marco, M. P. Strategies for quorum sensing Inhibition as a tool for controlling Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 64, 107323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2024.107323 (2024).

Patel, K. et al. Combatting antibiotic resistance by exploring the promise of quorum quenching in targeting bacterial virulence. Microbe 6, 100224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microb.2024.100224 (2025).

Benkő, P., Gémes, K. & Fehér, A. Polyamine oxidase-generated reactive oxygen species in plant development and adaptation: the polyamine oxidase—NADPH oxidase nexus. Antioxidants 11, 2488. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11122488 (2022).

Solmi, L. et al. The influence of the polyamine synthesis pathways on Pseudomonas syringae virulence and plant interaction. Microbiology 171, 001569. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.001569 (2025).

Kim, S. H. et al. Putrescine regulating by stress-responsive MAPK cascade contributes to bacterial pathogen defense in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 437, 502–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.06.080 (2013).

Xie, C. et al. Polyamine signaling communications play a key role in regulating the pathogenicity of Dickeya fangzhongdai. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e01965–e01923. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.01965-23 (2023).

Yi, Q., Park, M. J., Vo, K. T. X. & Jeon, J. S. Polyamines in Plant-Pathogen interactions: roles in defense mechanisms and pathogenicity with applications in fungicide development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 10927. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252010927 (2024).

Neshat, M. et al. Plant growth promoting bacteria (PGPR) induce antioxidant tolerance against salinity stress through biochemical and physiological mechanisms. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 28, 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-022-01128-0 (2022).

Abdelkhalek, A., Al-Askar, A. A. & Behiry, S. I. Bacillus licheniformis strain POT1 mediated polyphenol biosynthetic pathways genes activation and systemic resistance in potato plants against alfalfa mosaic virus. Sci. Rep. 10, 16120. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72676-2 (2020).

Elsharkawy, M. M. et al. Systemic resistance induction of potato and tobacco plants against Potato virus Y by Klebsiella oxytoca. Life 12, 1521. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12101521 (2022).

Hussain, S. S., Ali, M., Ahmad, M., Siddique, K. H. M. Polyamines: Natural and engineered abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in plants. Biotechnol. Adv. 29, 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.01.003 (2011).

Smirnoff, N. & Arnaud, D. Hydrogen peroxide metabolism and functions in plants. New. Phytol. 221, 1197–1214. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15488 (2019).

Raoul des Essarts, Y. et al. Biocontrol of the potato Blackleg and soft rot diseases caused by Dickeya dianthicola. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 268–278. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02525-15 (2015).

Philip, B. et al. Trichoderma afroharzianum TRI07 metabolites inhibit Alternaria alternata growth and induce tomato defense-related enzymes. Sci. Rep. 14, 1874. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52301-2 (2024).

Sorahinobar, M., Eslami, S., Shahbazi, S. & Najafi, J. A mutant Trichoderma harzianum improves tomato growth and defense against Fusarium wilt. Eur. J. Plant. Pathol. 172, 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-024-02992-0 (2025).

Osei, R. et al. Antagonistic bioagent mechanisms of controlling potato soft rot. Plant. Protect Sci. 58, 18–30. https://doi.org/10.17221/166/2020-PPS (2022).

Hadizadeh, I. et al. Transcriptome analysis unravels the biocontrol mechanism of Serratia plymuthica A30 against potato soft rot caused by Dickeya solani. Plos One. 19, e0308744. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0308744 (2024).

Cappellari, L. D. R., Chiappero, J., Santoro, M. V., Giordano, W. & Banchio, E. Inducing phenolic production and volatile organic compounds emission by inoculating Mentha piperita with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Sci. Hortic. 220, 193–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2017.04.002 (2017).

Sánchez-Rodríguez, E., Moreno, D. A., Ferreres, F., Rubio-Wilhelmi, M. D. M. & Ruíz, J. M. Differential responses of five Cherry tomato varieties to water stress: changes on phenolic metabolites and related enzymes. Phytochem 72, 723–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.02.011 (2011).

Mesa-Marín, J. et al. PGPR reduce root respiration and oxidative stress enhancing Spartina maritima root growth and heavy metal rhizoaccumulation. Front. Plant. Sci. 9, 1500. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01500 (2018).

Friedman, M. Chemistry, biochemistry, and dietary role of potato polyphenols. A review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 45, 1523–1540. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf960900s (1997).

Harrison, A. M. & Soby, S. D. Reclassification of Chromobacterium violaceum ATCC 31532 and its quorum biosensor mutant CV026 to Chromobacterium subtsugae. AMB Express. 10, 202. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-020-01140-1 (2020).

Morohoshi, T., Kato, M., Fukamachi, K., Kato, N. & Ikeda, T. N -acylhomoserine lactone regulates Violacein production in Chromobacterium violaceum type strain ATCC 12472. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 279, 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01016.x (2008).

Shaw, P. D. et al. Detecting and characterizing N-acyl-homoserine lactone signal molecules by thin-layer chromatography. PNAS 94, 6036–6041. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.12.6036 (1997).

Chilton, M. D. et al. Agrobacterium tumefaciens DNA and PS8 bacteriophage DNA not detected in crown gall tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 71, 3672–3676. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.71.9.3672 (1974).

Torres, M. et al. I. N-acylhomoserine lactone-degrading bacteria isolated from hatchery bivalve larval cultures. Microbiol. Res. 168, 547–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2013.04.011 (2013).

Romero, M. et al. In vitro quenching of fish pathogen Edwardsiella tarda AHL production using marine bacterium Tenacibaculum sp. strain 20J cell extracts. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 108, 217–225. https://doi.org/10.3354/dao02697 (2014).

Frikha-Gargouri, O. et al. Lipopeptides from a novel Bacillus methylotrophicus 39b strain suppress Agrobacterium crown gall tumours on tomato plants. Pest Manag Sci. 73, 568–574. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.4331 (2017).

Torres, M. et al. Selection of the N-acylhomoserine lactone-degrading bacterium Alteromonas stellipolaris pqq-42 and of its potential for biocontrol in aquaculture. Front. Microbiol. 7, 646. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00646 (2016).

Baird-Parker, A. C. A classification of Micrococci and Staphylococci based on physiological and biochemical tests. J. Gen. Microbiol. 30, 409–427. https://doi.org/10.1099/00221287-30-3-409 (1963).

Barrow, G. I. & Feltham, R. K. A. Cowan and Steel’s Manual for the Identification of Medical Bacteria, 3rd edition. (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Larpent, J. P. & Larpent-Gourgaud, M. Mémento technique de microbiologie: La Cellule bactérienne, métabolisme, systématique, bactéries utiles, milieux de culture et réactifs. Tech. Document. (1975).

Torres, M. et al. HqiA, a novel quorum-quenching enzyme which expands the AHL lactonase family. Sci. Rep. 7, 943. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01176-7 (2017).

Flores, H. E. & Galston, A. W. Analysis of polyamines in higher plants by high performance liquid chromatography. Plant. Physiol. 69, 701–706. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.69.3.701 (1982).

Benzie, I. F. F. & Strain, J. J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of antioxidant power: the FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 239, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1006/abio.1996.0292 (1996).

Re, R. et al. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol. Med. 26, 1231–1237. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3 (1999).

Alexieva, V., Sergiev, I., Mapelli, S. & Karanov, E. The effect of drought and ultraviolet radiation on growth and stress markers in pea and wheat. Plant. Cell. Environ. 24, 1337–1344. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00778.x (2001).

Green, T. R. & Fellman, J. H. Effect of photolytically generated riboflavin radicals and oxygen on hypotaurine antioxidant free radical scavenging activity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 359, 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-1471-2_3 (1994).

Beyer, W. F. & Fridovich, I. Assaying for superoxide dismutase activity: some large consequences of minor changes in conditions. Anal. Biochem. 161, 559–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(87)90489-1 (1987).

Singleton, V. L., Orthofer, R. & Lamuela-Raventós, R. M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. In Methods in enzymology. 299, 152–178. (Academic Press, 1999).

Castro-Cegrí, A. et al. Application of polysaccharide-based edible coatings to improve the quality of zucchini fruit during postharvest cold storage. Sci. Hortic. 314, 111941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2023.111941 (2023).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 (1976).

Funding

This research was funded by PID2023-150154OB-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI /10.13039/501100011033 and by ERDF/EU, PID2019-106704RB-100 funded by MICIU/AEI /10.13039/501100011033/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and B-AGR-222-UGR20 funded by Consejería de Universidad, Investigación e Innovación de la Junta de Andalucía and, ERDF A way of making Europe.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.S conducted experimental work, data curation, formal analysis and prepared the figures. P.S. wrote the original draft), A.M. conducted experimental work and formal analysis, F.P. contributed to the conceptualization and methodology of the study and supervised and wrote the main manuscript text, I.S. contributed to the conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition and wrote the original draft, I.L. contributed to the conceptualization, experimental work, methodology, project administration, funding acquisition and wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sánchez, P., Monzón-Ramos, A., Sampedro, I. et al. Quorum-quenching halotolerant bacteria as biocontrol agents against potato phytopathogens. Sci Rep 16, 3986 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34087-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34087-z