Abstract

Road extraction from remote sensing imagery is essential for urban planning, traffic monitoring, and emergency response. However, existing methods often focus solely on spatial-domain features, limiting their ability to model complex topological structures like narrow or fragmented roads. To address this limitation, we propose a dual-branch framework—DSWFNet—that fuses spatial and frequency domain features for road extraction. The model introduces a frequency-domain branch constructed via Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) to complement the RGB-based spatial branch in modeling fine image details. To further enhance feature representations, we design two dedicated attention mechanisms: the Multi-Scale Coordinate Channel Attention (MSCCA) module for spatial features, and the Enhanced Frequency-Domain Channel Attention (EFDCA) module for frequency features. These are followed by a Bidirectional Cross Attention Module (BCAM) that enables deep interaction and fusion of the two feature types, significantly improving the model’s sensitivity to road targets and its ability to preserve structural continuity. Experiments on two representative datasets validate the effectiveness of our approach. Specifically, on the Massachusetts dataset, DSWFNet achieves an IoU of 66.07% and an F1 of 79.57%, improving upon the best spatial-domain method, OARENet, by 1.25% and 0.92%. On the CHN6-CUG dataset, performance is further enhanced with an IoU of 70.76% and an F1 of 82.88%, surpassing the leading baseline by 1.64% and 1.13%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the continuous advancement of aerospace technologies and sensor precision, the spatial resolution of remote sensing imagery has steadily improved, resulting in increasingly rich and clear representations of ground objects such as land, mountains, rivers, urban areas, and roads1. Accurate extraction of road information from remote sensing imagery has become a research focus of considerable practical significance, with widespread applications in urban development2, traffic planning3, map updating4, and post-disaster emergency route design5. However, road extraction from remote sensing imagery remains challenging. Roads are elongated structures that occupy only a small portion of the image, causing severe class imbalance. Their materials often vary in color and may appear visually similar to surrounding terrain or buildings, while occlusions from trees and tall structures further disrupt boundary continuity. These difficulties have motivated researchers to develop more robust and efficient methods to improve the practical applicability of remote sensing imagery in real-world scenarios.

Road extraction from remote sensing imagery can be broadly categorized into traditional methods and deep learning-based approaches. Traditional methods rely on manually designed shallow road features for extraction6. However, these handcrafted features are often overly specific or incomplete due to subjective biases, and they suffer from limitations such as time-consuming annotation processes and high sensitivity to changes in road characteristics. As a result, traditional approaches tend to perform poorly and exhibit limited generalizability when applied to new remote sensing images or complex road scenarios7,8. With the rapid development of deep learning networks, enhanced computational capabilities, and the availability of high-resolution remote sensing images, deep learning has become the mainstream approach for road extraction9. Deep learning treats road extraction as a semantic segmentation task, where pixels in remote sensing images are classified into foreground (roads) and background. Leveraging deep neural networks, these methods can automatically extract multi-scale semantic features and learn discriminative representations to accurately distinguish road pixels10.

Remote sensing images cover large areas, and roads usually extend continuously, creating strong long-range dependencies. Conventional convolutional neural networks (CNNs), limited by local receptive fields, struggle to capture global context in high-resolution imagery, which affects road extraction accuracy11,12. Deep networks like ResNet and DenseNet mitigate this with residual and dense connections, while LinkNet combines ResNet and UNet to fuse low- level and high-level features, improving segmentation13. Zhou et al. further enhanced LinkNet with multi-scale dilated convolutions to balance local detail and global context14.

Subsequent studies have focused on the integration of attention mechanisms into road extraction tasks15. For instance, Yang et al. employed a spatial enhancement attention mechanism (DULR) that sequentially learns directional features from four orientations of the feature map, and integrated it with a densely connected UNet architecture for road feature extraction16. Wan et al. designed a dual-attention module combining spatial and channel-wise attention to build a densely connected network for road extraction17. Chen et al. incorporated spatial and channel attention mechanisms into a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based semi-supervised framework to address class imbalance between road and non-road pixels18. Recently, state-space models (SSMs) such as Mamba have emerged for efficient long-range modelling. Mamba-DCAU couples an optimized Mamba with U-Net via dual attention and center sampling, achieving accurate full-scene HSI classification with linear-time complexity; its principles are transferable to road segmentation19. Beyond spatial/channel attention, graph-based global modelling has also been explored. A temporal–spatial multiscale graph attention network (TSMGA) introduces shortest-path graph attention to aggregate long-distance context more efficiently while highlighting bitemporal disparities, improving robustness under complex backgrounds and lighting changes20.

Despite these advancements, most existing attention mechanisms still depend on fixed receptive fields, limiting their ability to capture long-range dependencies. Transformers, through self-attention, compute relations between arbitrary positions, enabling global context modeling21. For example, He et al. proposed integrating a Swin Transformer with a UNet-like spatial interaction module for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images22, while Wu et al. constructed a semantic segmentation framework based on ResNet-18 and a multiscale local-context transformer to jointly model global and local features in remote sensing maps23. In parallel, multi-branch fusion frameworks that combine CNNs and Transformers have been proposed in change-detection settings; MVAFG fuses low-/high-dimensional features via personalised filtering and an attention-based position-adjustment module, yielding complementary local edge/detail cues and global semantics24.

However, spatial features alone are often inadequate under complex imaging conditions such as lighting variation, shadows, or terrain changes. Frequency features, being more sensitive to edges and textures, can better highlight low-contrast targets. Their fusion thus provides more robust representations and improves segmentation. Inspired by biological vision studies, predators in nature frequently exploit frequency-sensitive perceptual mechanisms to identify camouflaged prey, enabling them to detect subtle textural or structural variations that are often imperceptible to the human visual system, which is limited to the RGB spectrum25,26. This frequency-dependent predation strategy provides a compelling biological rationale for incorporating frequency-domain features into camouflaged object detection frameworks, offering a pathway to surpass the limitations of conventional image analysis confined to spatial cues alone27.

Recent studies have begun incorporating frequency information into remote sensing segmentation. For example, Li et al. proposed RoadCorrector, a multi-branch network that integrates intersection features with frequency-domain information for road extraction, effectively improving road connectivity28; however, its frequency fusion remains relatively shallow, limiting the ability to fully exploit complementary spatial–frequency cues in complex backgrounds. Yang et al. introduced SFFNet, which extracts spatial features and maps them into high/low-frequency and global/local domains via a two-stage process, followed by multidimensional fusion to improve segmentation accuracy29; yet, the model lacks targeted enhancement for critical frequency bands. Li et al. developed LCMorph, which embeds frequency-aware modules in the encoder to separate low-contrast roads from the background and employs morphological perception blocks in the decoder to adaptively restore road details; while effective for detail recovery, it does not explicitly address the semantic misalignment between spatial and frequency features, which may limit generalization to diverse road textures30. Recent work also fuses frequency cues with spatial semantics. STWANet couples a wavelet feature-enhancement path with a dual-attention aggregation module and a spatio-temporal differential self-attention block, strengthening high-frequency edges/textures while preserving global layout31.

The fusion of spatial and frequency features has undergone gradual development. Traditional methods typically adopt shallow fusion, such as directly concatenating or adding Fourier- or wavelet-transformed frequency features with spatial features. While these methods improve low-level details to some extent, they often overlook the semantic discrepancy between the two domains, resulting in insufficient global consistency32. With the rise of deep learning, researchers have proposed multi-scale and attention-driven fusion mechanisms. For example, SFFNet integrates wavelet decomposition with the Multi-domain Attention Fusion (MDAF) module, which alleviates part of the semantic heterogeneity but still relies on a fixed interaction pattern, essentially remaining unidirectional29. Building on frequency decomposition, Zhu et al. enhanced boundary modeling to better align spatial and frequency representations33, while Wei et al. introduced uncertainty modeling to improve fusion robustness34; nevertheless, such methods generally suffer from feature misalignment and static fusion strategies. More recently, such as those by Zhao et al. and Zhang et al., incorporate frequency-domain denoising, multi-scale attention, and Transformer architectures to improve consistency and detail restoration35,36, but they still face challenges in terms of training stability and computational cost.

Building upon the aforementioned challenges and recent research advances, a deep convolutional network architecture that fuses spatial and frequency-domain features is proposed for road extraction in remote sensing imagery. The architecture consists of two parallel branches: a spatial-domain encoder and a frequency-domain encoder, both employing ConvNeXt-T37 as the backbone. The frequency branch is based on DWT, using the Haar wavelet to transform input RGB images into multiple frequency sub-bands. The model integrates MSCCA and EFDCA to enhance the discriminative capacity of features during encoding. During feature fusion, BCAM is introduced to deeply integrate spatial and frequency features, effectively mitigating semantic discrepancies between the two domains. The main contributions of this research are as follows:

-

1.

We propose DSWFNet, a dual-branch architecture that fuses spatial and frequency-domain features using ConvNeXt-T as the backbone and the Haar wavelet transform for complementary feature extraction.

-

2.

We design three attention modules—MSCCA for spatial features, EFDCA for frequency features, and BCAM for cross-domain fusion—to enhance feature representation and capture road structures.

-

3.

We validate DSWFNet on the Massachusetts38 and CHN6-CUG39 datasets, achieving superior performance over state-of-the-art methods and confirming the contribution of each module through ablation studies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 provides a detailed description of the proposed spatial-frequency fusion network for road extraction. Section 3 presents comparative and ablation experiments, along with the analyses of the results. Section 4 offers a discussion of the research, and Sect. 5 concludes the paper with a summary and prospects for future research.

Methods

DSWFNet architecture

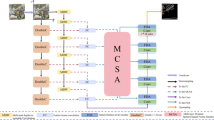

Unlike conventional architectures that rely solely on spatial-domain feature encoding, the proposed DSWFNet introduces a frequency-domain branch in the encoder to complement the spatial features of RGB images (Fig. 1). The backbone adopts ConvNeXt-T, which has been shown to achieve competitive performance in semantic segmentation compared with both CNNs and Transformer-based networks29,37. Through skip connections, low-level details are fused with high-level semantics, while spatial features are enhanced via the MSCCA module for multi-scale perception, and frequency features are refined with the EFDCA module to improve discriminability. These enriched features are further integrated by the BCAM to enable effective interaction between spatial and frequency features. The fused representations are decoded using the D-LinkNet decoder to reconstruct the final segmentation map.

During encoding, ConvNeXt-T performs multi-scale feature extraction in both the spatial and frequency branches. The input RGB image is denoted as \({\mathbf{X}} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{3 \times h \times w}}\), where 3 corresponds to the RGB channels, and h and w represent the height and width of the image in pixels, respectively. ConvNeXt-T contains four stages with output channels C = (96, 192, 384, 768) and block numbers B = (3, 3, 9, 3). After each stage, the height and width of the feature maps are halved to progressively capture deeper semantic features.

The spatial branch directly processes the original RGB image, while the frequency branch applies a Haar wavelet decomposition to each RGB channel, producing four sub-bands (LL, LH, HL, HH) per channel, for a total of 12 frequency maps as input. Cross-domain skip connections are introduced from the second stage onward to facilitate complementary interactions between branches, strengthening feature completeness and robustness. The decoder then progressively upsamples these fused features to generate refined road-extraction results.

Haar wavelet transform

Common DWT families—Daubechies (db), Symlets (sym), Coiflets (coif), and Biorthogonal (bior) and their typical orders are used to decompose an image. The R-channel HL sub-bands are compared in Fig. 2, showing that db1 (Haar) yields sharper road boundaries and better connectivity, more clearly delineating thin, low-contrast road structures. As the order increases, wavelets become smoother and represent higher-order polynomials; however, this requires longer filters, raises computational cost, and exacerbates boundary effects. Accordingly, we employ the Haar wavelet as the DWT basis: its low computational cost, memory efficiency, and strong sensitivity to local discontinuities (road edges) make it particularly suitable for large-scale remote sensing segmentation, where edge preservation and structural boundary detection are critical.

During frequency-domain feature extraction, the input RGB image is decomposed via a 2D Haar wavelet transform to generate sub-band energy maps. Specifically, for a 2D image f(x, y), the wavelet transform can be expressed as40:

Here, the four sub-bands LL, LH, HL, and HH correspond to different frequency components. The LL sub-band primarily preserves the overall structural and brightness information of the image, albeit at reduced resolution, while the LH, HL, and HH sub-bands capture edge and texture features in the vertical, horizontal, and diagonal directions, respectively. Applying the decomposition to each RGB channel produces 12 frequency-domain feature maps in total (Fig. 3). Notably, road information is particularly prominent in the HL sub-bands, which emphasize horizontal edge structures.

Multi-scale coordinate-channel attention

The MSCCA module enhances the network’s ability to jointly model spatial structures and semantic channels by integrating a channel-attention mechanism41 with a multi-scale coordinate-orientation attention mechanism42,43, as illustrated in Fig. 4. This module is designed to adaptively capture both channel-wise importance and spatial directional information while preserving the spatial resolution of the feature maps. By introducing multi-scale horizontal and vertical strip convolutions, MSCCA effectively models the geometric shapes and directional arrangements of targets under varying receptive fields. Combined with a channel reweighting mechanism, it further strengthens the representation of critical features, thereby improving the network’s perception of fine-grained targets—such as road edges and narrow structures—and enhancing its semantic discrimination capability.

First, statistical aggregation is performed along the channel dimension of the input feature map \({\mathbf{X}} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{B \times C \times H \times W}}\) to generate directional statistical feature maps. The horizontal and vertical statistical feature maps are defined as follows:

\({\text{Mea}}{{\text{n}}_c}( \cdot )\) and \({\text{Ma}}{{\text{x}}_c}( \cdot )\) refer to the channel-wise average and maximum computations. This procedure is analogous to the directional feature compression used in coordinate attention, but with the advantage of preserving the full spatial structure of the original feature map.

In recent years, researchers have adopted strategies that multi-scale convolutional kernels and multi-scale strip convolutions, effectively enabling the integration of features with different receptive fields for joint modeling of fine-grained details and global context44,45. Based on this idea, we apply multi-scale depth-wise directional convolutions separately to the horizontal and vertical statistical feature maps to fully capture road structures at different scales. The corresponding convolution operations are defined as follows:

where Conv1 × k and Convk × 1 denote two-dimensional convolutions with kernel sizes 1 × k and k × 1, respectively. Strip–conv kernels of sizes k ∈ {3, 7, 11, 15} are employed to capture road structures at multiple scales. Smaller kernels (3, 7) are effective in extracting local and medium-range details such as road edges and short segments, while larger kernels (11, 15) capture long-range continuity without exceeding the spatial extent of the feature maps, with all sizes constrained within the feature map resolutions (128 × 128, 64 × 64, 32 × 32, 16 × 16). This configuration strikes a balance between local precision and global connectivity. The resulting 8 directional feature maps (4 from each direction) are concatenated and passed through a 1 × 1 convolution to restore the channel dimension, forming a unified direction-aware feature representation.

the concatenation (Concat) operation is performed along the channel dimension, and f1 × 1 denotes a fusion convolution used to compress the channel dimension and facilitate cross-directional information integration.

In convolutional neural networks, each channel typically encodes a specific feature type, such as edges, textures, or color distributions. However, not all channels contribute equally to semantic segmentation. To address this, MSCCA introduces a channel attention module based on the classic SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation) mechanism. This module applies global pooling and nonlinear transformations to extract channel-wise importance weights, enabling the model to assign adaptive attention to different channels and focus on the most informative features.

To obtain the feature response intensity of each channel, the input feature map \({\mathbf{X}} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{B \times C \times H \times W}}\) is processed by both global average pooling and global max pooling to describe and capture distinctive channel-wise characteristics. The two outputs are then concatenated along the channel dimension to form a joint channel descriptor:

where AvgPool(·) and MaxPool(·) denote adaptive global pooling operations, and Z denotes the concatenated channel features. Next, a two-layer convolution is applied to compress and then expand the channel dimension, introducing a nonlinear transformation (ReLU) to generate the channel attention weights Achannel:

\({W_1} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{\frac{C}{r} \times 2C}}\) and \({W_2} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{C \times \frac{C}{r}}}\) denote two sequential 1 × 1 convolutions used for dimensionality reduction and expansion, where r is the channel reduction ratio. Finally, the channel attention map Achannel and the spatial-directional attention map Aspatial are combined via element-wise addition, followed by a sigmoid activation function to normalize the fused attention map.

σ(·) denotes the sigmoid activation function, which maps the fused attention weights into the range of [0, 1], assigning an explicit attention response strength to each spatial position and channel. Subsequently, the attention weights are applied to the original input feature map X in an element-wise manner. A learnable scaling factor γ and a residual connection are introduced to enhance the model’s stability and representational capacity. The final output feature map is given by:

where · denotes element-wise multiplication, and γ is a learnable parameter initialized to 0. This initialization ensures that the network behaves as an identity mapping at the beginning of training, allowing it to gradually learn effective attention modulation during optimization.

Enhanced frequency domain channel attention

As shown in Fig. 5, EFDCA is an enhanced module based on the channel attention mechanism46,47, designed to improve the representation and selectivity of frequency-domain features. This module combines two types of channel-wise statistical descriptors: global average pooling (GAP) and global max pooling (GMP). The pooled statistics are passed through multiple nonlinear transformation layers to generate a set of channel-wise weights, which are then used to reweight the input feature map along the channel dimension. This enhances the model’s sensitivity to critical frequency-domain features. In addition, a DropPath (stochastic depth) strategy is introduced to improve generalization and training stability, helping to mitigate overfitting.

Given the input feature map \({\mathbf{X}} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{B \times C \times H \times W}}\), EFDCA applies GAP and GMP independently to each channel, resulting in two global descriptors for each channel:

these two descriptors are then concatenated to form a joint channel descriptor:

this joint descriptor is then passed through three consecutive 1 × 1convolution layers with ReLU activation and Batch Normalization (BN) to generate the channel attention weights:

here, \({W_1} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{C \times 2C}}\)reduces the channel dimension, \({W_2} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{\frac{C}{r} \times C}}\) restores the channel dimension, and \({W_3} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{C \times \frac{C}{r}}}\) maps it back to the original number of channels. σ(·) denotes the sigmoid activation function, and BN represents the Batch Normalization operation.

To enhance the regularization effect of EFDCA, a DropPath strategy is introduced to randomly drop attention weights during training. The mechanism is defined as:

where p denotes the drop probability, set to 0.1. Higher drop rates were found to cause over-regularization, thereby impairing fine-grained road detail extraction. \({\mathbf{m}} \in {\{ 0,1\} ^{B \times 1 \times 1 \times 1}}\) is a random binary mask generated per batch, \(\widetilde {{\mathbf{A}}}\)denotes the retained attention weights after dropping. A is scaled by 1 / (1 - p) to maintain the expectation and ensure training stability. Finally, the attention weights are applied to the input feature map via channel-wise multiplication:

Bi-directional cross-attention module

To address the semantic heterogeneity between the frequency and spatial domains, the Bidirectional Cross-Attention Module (BCAM) (Fig. 6) is proposed as a flexible and adaptive fusion mechanism that explicitly models cross-domain discrepancies. Spatial and frequency features are first projected into a unified embedding space via lightweight 1 × 1 convolutions. Two complementary attention pathways are then constructed: a horizontal branch, which rearranges features along the row dimension, and a vertical branch, which rearranges features along the column dimension. This orthogonal design enables more effective modeling of elongated road structures and their orientation-specific dependencies.

For each branch, queries are obtained from one domain while keys and values are derived from the counterpart domain, enabling bidirectional information exchange (spatial→frequency and frequency→spatial). To stabilize training and emphasize relative similarity, Q and K are normalized in cosine space and scaled by a learnable temperature. Furthermore, learnable positional biases are added in both horizontal and vertical directions to enhance structural consistency and compensate for the lack of explicit positional priors in axis-wise attention.

The outputs of the two branches are then adaptively integrated through a gated fusion mechanism, where a learnable gate balances horizontal and vertical dependencies according to the scene context. Finally, a residual connection and MLP refinement are applied to preserve original semantics and strengthen feature discriminability.

Compared to conventional unidirectional attention, BCAM establishes stronger bidirectional dependencies across spatial–frequency representations and captures heterogeneous correlations more effectively. This design enhances both the structural continuity of narrow, elongated road segments and the contextual awareness of surrounding textures, yielding more robust and semantically aligned fusion results.

\({{\mathbf{X}}_s} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{B \times C \times H \times W}}\) and \({{\mathbf{X}}_f} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{B \times C \times H \times W}}\)denote the spatial-domain and frequency-domain inputs, respectively. To align the semantic space of both domains, BCAM first applies a shared convolution to unify their representation:

where Wp denotes the shared 1 × 1 convolution kernel used for dimension alignment. The features are then split into h heads (C = h · d) along the channel dimension and used to construct horizontal and vertical attention paths across spatial and frequency branches, enabling deep bidirectional interaction. Horizontal attention on frequency features:

vertical attention on spatial features:

To improve the stability of similarity computation and avoid dot-product explosion, cosine normalization is adopted before computing attention matrices. Additionally, learnable positional bias terms Ph and Pw are introduced to enhance direction-aware modeling:

where τ is a temperature parameter controlling the attention sharpness.

The context features are then computed by applying the attention weights to the value features, and a residual connection with the original query is added to form a compensation path, preserving local information while integrating global dependencies:

to adaptively fuse horizontal and vertical attention outputs, a learnable gating mechanism g ∈ [0, 1] is introduced to balance the spatial and frequency contributions:

here, g = σ(·) is obtained through a sigmoid activation, controlling the fusion ratio. Finally, the fused features are passed through a 1 × 1 convolution to restore the original channel dimension. A lightweight Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) is further applied for local enhancement, and a residual connection is used to preserve information flow and ensure training stability:

Loss function

Road pixels are significantly outnumbered by background pixels in remote sensing images. To mitigate this class imbalance, Focal Loss48, an extension of Binary Cross Entropy (BCE), introduces a modulating factor that emphasizes learning on road pixels with fewer pixels:

where pt = p if the true label y = 1 (road), and pt = 1 - p if y = 0 (background); γ = 2 is the focusing parameter; αt denotes the balancing factor between road and background classes.

Dice Loss49, derived from the Dice Coefficient, measures the overlap between the predicted and ground truth regions. It is particularly effective for boundary prediction and small object segmentation:

p and y denote the predicted and ground truth values, ε is a small constant (set to 1 × e− 6) added to prevent division by zero.

Accordingly, the overall loss function used is a weighted sum of the two:

where λ1 = λ2 = 1.

Results

Datasets

The Massachusetts dataset consists of 1,171 remote sensing images with annotated road labels. The official split includes 1,108 training images, 14 validation images, and 49 testing images. Each image has a resolution of 1500 × 1500 pixels, covering an area of 2.25 square kilometers with a spatial resolution of 1 m/pixel. In total, the dataset spans approximately 2,600 km2. The CHN6-CUG dataset comprises high-resolution remote sensing images, covering six representative towns in China. Each image has a spatial resolution of 0.5 m/pixel. The original dataset includes 4,511 images, but those without road content—such as ocean areas—were removed during preprocessing. After cleaning, 3,532 images containing road pixels were retained. The dataset is randomly divided into 2,425 training images, 303 validation images, and 304 testing images. CHN6-CUG features diverse urban road patterns and is well-suited for training and evaluating deep learning models for road extraction tasks.

Some state-of-the-art methods

D-LinkNet14, proposed by Zhou in 2018, enhances LinkNet by incorporating dilated convolution blocks with varying dilation rates, expanding the receptive field and improving feature extraction. It achieved the highest IoU in the DeepGlobe road extraction challenge at CVPR 2018.

SDUNet16, proposed by Yang in 2022, improves UNet with a Spatial CNN module and a densely connected encoder–decoder, enabling better multi-level context modeling and road-specific feature learning.

REF-LinkNet50, proposed by Zhao in 2023, adopts a U-shaped architecture with receptive field enhancement modules and dual attention in skip connections, strengthening multi-scale feature representation and fusion.

SFFNet29, proposed by Yang in 2024, fuses spatial and frequency features. Spatial features are mapped into both domains and fused through multi-scale convolution and dual cross-attention, improving segmentation of complex structures.

OARENet51, proposed by Yang in 2024, introduces an occlusion-aware decoder with varying dilation rates and randomized convolutions to better extract road features under building and tree occlusions.

LCMorph30, proposed by Li in 2025, integrates frequency cues and morphological perception to address low-contrast road extraction, particularly where roads resemble backgrounds or appear thin and curved.

DenseDDSSPP-DeepLabV3+52, proposed by Mahara in 2025, incorporates Dense Depthwise Dilated Separable Spatial Pyramid Pooling into DeepLabV3 + to enhance extraction of complex road structures.

AEFNet53, proposed by Gao in 2025, fuses frequency and spatial features using an Adaptive Frequency–Spatial Interaction Module and a Selective Feature Fusion Module, effectively integrating global context with local details.

Evaluation metrics

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of different methods in road extraction, we adopt common evaluation metrics including Precision (P), Recall, F1 Score (F1), and Intersection over Union (IoU). These metrics assess the accuracy and completeness of road detection from different perspectives. Their calculation formulas are defined as follows:

Here, TP (True Positive) refers to the number of pixels correctly predicted as road; FP (False Positive) refers to the number of pixels incorrectly predicted as road; and FN (False Negative) refers to the number of road pixels mistakenly predicted as non-road. In addition, TN (True Negative)—although not used in the formulas—is defined as the number of pixels correctly predicted as non-road. These four components form the foundation for classification performance evaluation and are used to calculate key metrics such as Precision, Recall, F1 Score, and IoU.

To comprehensively evaluate the computational cost and deployment feasibility of each model, the number of parameters (Params), floating-point operations (FLOPs), inference time, and GPU peak memory allocated (Peak Alloc) are reported. These metrics indicate structural complexity, computational overhead, and the practicality of model deployment.

Implementation details

Experiments were conducted on Ubuntu 18.04 equipped with an NVIDIA RTX A4000 GPU. The deep learning framework was built using PyTorch 2.5.1. The Adam optimizer was employed with an initial learning rate of 1e-4, and a combination of Warmup and Cosine Annealing learning rate scheduling strategies was applied. This setup ensures a smooth transition during the early training phase, followed by periodic convergence, thereby enhancing model stability and final performance. For data augmentation, the original remote sensing images were randomly cropped to 512 × 512 pixels. Various augmentation techniques were applied, including random horizontal flip, vertical flip, random 90-degree rotation, and affine transformation, to increase sample diversity and improve model generalization, while also reducing computational cost and GPU memory usage. The batch size was set to 4, and the model was trained for a total of 100 epochs. Multi-scale test-time augmentation (MS-TTA) was used for testing.

Experimental results

Massachusetts dataset calculation results and analysis

Table 1 presents quantitative results on the Massachusetts dataset using Params, FLOPs, Precision, Recall, F1, and IoU as evaluation metrics. The proposed DSWFNet achieves superior performance across most metrics, with a dual-branch encoder that leads to 61.33 M parameters, the second highest among the models, but balances complexity with strong feature extraction capability. This balance is largely attributed to the ConvNeXt-T backbone, which employs Depthwise and Pointwise Convolutions for efficient representation, replaces Batch Normalization with Layer Normalization to reduce batch-size dependence, and reduces spatial dimensions through strided convolution rather than pooling. These optimizations make the model parameter-rich yet computationally efficient, with FLOPs ranked second-lowest at 18.47G, enabling fast inference. By comparison, SDUNet has the fewest parameters (2.47 M) but incurs 234.72G FLOPs due to its direction-aware modules that convolve feature maps along four directions, substantially increasing computation despite improved directional sensitivity. LCMorph, with 71.9 M parameters, adopts a ResNet-101 backbone, multi-frequency channel computation, and snake convolution, resulting in 587.72G FLOPs and significantly greater computational burden. Overall, the analysis demonstrates that DSWFNet achieves a well-balanced architectural design, offering effective feature representation while maintaining relatively low complexity.

According to the definitions, P indicates the accuracy of predicted roads—high precision means fewer false alarms but may miss some roads. Recall reflects detection completeness—high recall finds more roads but may include false positives. F1 balances precision and recall to represent overall performance. IoU measures the overlap between predicted and ground truth road areas, capturing spatial continuity and serving as a key indicator of road extraction completeness.

As presented in Table 1, DSWFNet consistently outperforms competing models in terms of P, F1, and IoU, underscoring its superior accuracy and spatial completeness in road extraction from remote sensing imagery. While models such as D-LinkNet, SDUNet, and SFFNet achieve slightly higher Recall than DSWFNet—with OARENet surpassing it by 1.93%—this gain comes at the expense of markedly lower Precision and F1 scores, reflecting a higher incidence of false positives and reduced extraction reliability. These findings suggest that a higher Recall does not necessarily translate into more comprehensive extraction, particularly when accompanied by degraded precision. Notably, OARENet attains the second-best IoU of 64.82%, attributable to its Swin Transformer-based encoder, which offers a favourable trade-off between parameter efficiency and representational power. Nevertheless, DSWFNet achieves the highest IoU of 66.07%, representing a 1.25% improvement over OARENet, thereby demonstrating more faithful reconstruction of road geometry and coverage. This advantage highlights the effectiveness of dual-domain feature fusion in enhancing both the accuracy and the overall completeness of road extraction, compared with methods that rely solely on spatial-domain representations.

The blue-marked models SFFNet, LCMorph, and AEFNet employ dual-domain fusion strategies for road feature extraction, achieving IoU scores of 65.67%, 64.45%, and 63.77%, respectively. Notably, SFFNet outperforms OARENet by 0.85% in IoU. Both DSWFNet and SFFNet adopt ConvNeXt-T as the backbone encoder. However, their fusion strategies differ. SFFNet first extracts spatial features and then transforms them into the frequency domain, followed by the fusion of both domains—where the frequency features are derived from the spatial features. In contrast, DSWFNet utilizes a dual-branch encoder to independently extract features from the spatial and frequency domains of the input RGB image. This architecture leads to an IoU that is 0.4% higher than that of SFFNet, indicating more complete road extraction. In summary, the proposed DSWFNet demonstrates superior road extraction completeness on the Massachusetts dataset, benefiting from its explicit dual-domain features representation and fusion design.

Figure 7 presents a qualitative comparison of different models on the Massachusetts dataset. In the results, white regions represent correctly identified roads (TP), black regions represent correctly identified background (TN), blue regions indicate background areas mistakenly predicted as roads (FP), and red regions indicate actual roads mistakenly predicted as background (FN). In the first and second groups of images, several models, in pursuit of completeness, misclassify courtyards, parking lots, and internal access roads as roads, producing blue regions. By contrast, DSWFNet employs MSCCA to model channel saliency and directional spatial structures, suppressing speckle-like textures while retaining responses to slender roads. In the third group, the roads are thin and partially occluded by buildings and sandy/soil areas, leading other methods to frequent false negatives. EFDCA enhances frequency-domain selectivity, thereby strengthening high-frequency edges and weak-contrast features; this helps DSWFNet recover slender and shadowed road segments and reduces false negatives. However, in areas where roads are heavily covered by sand/soil and where annotations of internal access roads are inconsistent across the dataset (labeled as roads in some scenes but omitted in others), DSWFNet still struggles, yielding inferior extraction results. In the fourth group, which contains numerous small branches, most models suffer from broken predictions and missing intersections. BCAM aligns spatial and frequency features into a shared embedding and applies orthogonal cross-attention, improving directional consistency through curves and intersections; this yields more continuous topology with fewer breaks. There are also dirt roads that are difficult to perceive, which none of the models detect. Overall, DSWFNet outperforms the other methods in terms of accuracy, completeness, and robustness, making it well suited to complex remote-sensing road-extraction tasks.

CHN6-CUG dataset calculation results and analysis

Table 2 presents the quantitative comparison results of different models on the CHN6-CUG dataset. Similar to the findings on the Massachusetts dataset, DSWFNet achieves superior scores in Precision, F1, and IoU, demonstrating its strong capability in accurately and completely extracting road features from remote sensing images. However, DSWFNet’s Recall is slightly lower than that of D-LinkNet, REF-LinkNet, AEFNet, and especially OARENet, which surpasses DSWFNet by 3.47%. These models tend to sacrifice precision in favor of improved road completeness.

Among the spatial-domain methods, OARENet achieves the best road extraction performance with an IoU of 69.12%, which is only 1.64% lower than that of DSWFNet. However, this comes at the cost of a 5.88% reduction in precision. Although OARENet, which is built upon a Swin Transformer-based architecture, demonstrates strong overall performance in road extraction, its lower precision indicates a higher false positive rate compared to DSWFNet. Among the frequency–spatial domain fusion models, SFFNet ranks second only to DSWFNet. Nevertheless, it consistently underperforms DSWFNet across all evaluation metrics: Precision (− 0.20%), Recall (− 1.29%), F1-score (− 1.13%), and IoU (− 1.14%). These findings further confirm that DSWFNet surpasses compared methods in both spatial-only and frequency–spatial fusion strategies for road extraction on the CHN6-CUG dataset, offering clear advantages in terms of both accuracy and structural completeness.

Figure 8 shows the road extraction results of different models on the CHN6-CUG dataset, comparing four typical scenes. In the first group, SDUNet performs the worst, with many false edges and incomplete road extraction. In contrast, DSWFNet achieves the best results, with clear and complete roads. OARENet ranks second, while other models show various levels of errors and missing roads. The second group is more challenging due to the road’s similarity to the background, especially in the red box area. SDUNet still performs poorly with large false detections. Although other models improve slightly, they still make mistakes at edges and turns. DSWFNet again performs best, accurately outlining narrow roads and maintaining continuity, with the fewest errors.

In the third group of images, the red box highlights a road section with noticeable color changes, testing the model’s spatial resolution. Most models show road breaks or merging in this area, while DSWFNet successfully extracts the main road structure and recognizes the color transitions along the edges, improving boundary clarity. The fourth group evaluates the model’s ability to maintain road connectivity in a bent junction area. Most models fail to preserve the complete structure, showing breaks and blurred outputs. In contrast, DSWFNet restores the full road shape with fewer edge artifacts and noise, demonstrating stronger geometric consistency. Overall, the visual analysis on the CHN6-CUG dataset confirms that DSWFNet outperforms other models in road extraction under complex conditions, especially in maintaining edge integrity, recovering fine details, and preserving connectivity.

Inference time and GPU peak memory allocated

To more comprehensively assess deployment feasibility, we compared the average per-image inference time and Peak Alloc of all methods under identical hardware and input settings. Table 3 shows that D-linkNet, with its relatively simple ResNet-34 backbone and encoder containing only dilated convolutions, achieves the shortest single-image inference time (210.37 ms) with Peak Alloc of 481.9 MB. AEFNet uses a ResNet-18 backbone and has fewer parameters, but inserts three Adaptive Frequency Enhancement Blocks for frequency–spatial enhancement; although it attains the lowest Peak Alloc (349.1 MB), the extra frequency-domain convolutions and feature movements lead to a longer inference time (734.59 ms). DSWFNet adopts a dual-branch ConvNeXt-T backbone and integrates MSCCA, EFDCA, and BCAM to realize spatial–frequency complementarity and long-range dependency modelling. Therefore, its latency (765.84 ms) and Peak Alloc (759.5 MB) are increased, but its segmentation accuracy and IoU are the highest.

All the above evaluations were conducted using MS-TTA (3 scales × 8 flips; 24 forward passes), which substantially increases end-to-end latency. After disabling MS-TTA, the average latency of D-linkNet decreases from 210.37 ms to 7.94 ms (~ 26.5 × speedup) and its Peak Alloc from 481.9 MB to 375.2 MB; DSWFNet decreases from 765.84 ms to 28.38 ms (~ 27.0 × speedup) with Peak Alloc reduced from 759.5 MB to 641.6 MB. The IoU drops only slightly: D-linkNet 68.63% to 66.71% (− 1.92%) and DSWFNet 70.76% to 69.12% (− 1.64%). These results indicate that, in real-time deployment scenarios, disabling MS-TTA can substantially reduce latency and memory with only minor accuracy loss.

Ablation study

To evaluate the contribution of each module in DSWFNet—including MSCCA, EFDCA, BCAM, the frequency domain branch (FDB), and the spatial domain branch (SDB)—ablation experiments were conducted on the Massachusetts datasets.

Table 4 presents the ablation results on the Massachusetts dataset. Comparing WoMSCCA and WoEFDCA, their IoU scores are nearly identical; however, WoMSCCA achieves a higher Recall of 80.85% but a lower Precision of 77.93%, indicating more false positives. This demonstrates that MSCCA is critical in enhancing model precision by suppressing incorrect predictions. When contrasting WoFDB with WoSDB, WoFDB yields higher Recall, F1, and IoU by 5.84, 1.03, and 1.39%, respectively, while its Precision is 3.70% lower. These findings confirm the complementary roles of the two branches: SDB contributes to structural completeness of road connectivity, whereas FDB strengthens feature extraction accuracy. Furthermore, compared with separate spatial and frequency branches, BCAM effectively integrates both domains, balancing Precision and Recall and thereby improving F1 and IoU. Although BCAM exhibits a marginal reduction in Precision (–0.13%) relative to BCAM2Cat, it achieves higher Recall, F1, and IoU—with IoU increasing by 0.40%. This result highlights BCAM’s ability to enhance road feature completeness by promoting effective interaction between spatial and frequency-domain representations, making it a key component for the superior performance of DSWFNet.

Discussion

By explicitly fusing spatial geometry with frequency cues, DSWFNet improves delineation of thin, low-contrast, and partially occluded roads, which benefits map updating, post-disaster routing, traffic monitoring, and HD-map maintenance. With MS-TTA disabled, the ~ 26–27× speedup with minor IoU loss suggests a tunable accuracy–efficiency operating point for near-real-time use. Nevertheless, DSWFNet still has several areas for improvement: (1) Inference efficiency and memory usage. Although ConvNeXt-T offers strong feature extraction with relatively low FLOPs, the dual-branch encoder and attention fusion increase inference time and Peak Alloc, which is especially pronounced when multi-scale TTA is enabled. Future work will explore lightweight backbones (e.g., Mobile, Shuffle, and Rep families or lightweight ViTs) as partial or full backbone replacements to improve deployment feasibility. (2) Misclassification or omission due to annotation inconsistency. In the dataset, internal access roads and dirt tracks are annotated as roads in some scenes but not in others, leading to apparent FP/FN fluctuations. We plan to incorporate uncertainty estimation and active learning to mitigate annotation bias in training and evaluation. (3) Topological consistency under occlusion or low contrast. Although overall performance is strong, breaks or omissions may still occur under tree shade, building occlusion, or low-contrast segments. We plan to integrate topology-aware learning—introducing centerline, node, and connectivity constraints—and to apply graph neural networks with graph decoding for structural correction, enabling continuous road inference across occlusions. In summary, these directions are expected to further enhance deployment feasibility, cross-domain robustness, and topological integrity without sacrificing boundary quality.

Conclusions

This paper presents DSWFNet, a dual-branch spatial–frequency fusion network designed to enhance the accuracy and robustness of road extraction from remote sensing imagery. The architecture combines geometric features from the spatial domain with frequency components capturing edge, texture, and color variations, enabling more comprehensive and discriminative feature extraction. Based on the lightweight ConvNeXt-T backbone, DSWFNet employs parallel spatial and frequency encoders to improve feature representation. To strengthen the skip connections, MSCCA and EFDCA are introduced to refine spatial and frequency features, respectively. BCAM further integrates the two domains, improving semantic consistency and boundary detail. The fused features are decoded progressively to achieve more accurate road segmentation.

Experiments on the Massachusetts and CHN6-CUG datasets show that DSWFNet outperforms multiple mainstream methods. Each module contributes substantively to the overall performance, and the model exhibits good deployment feasibility. In particular, DSWFNet achieves higher Precision, F1, and IoU, reflecting its ability to suppress false positives and improve spatial completeness, albeit with a slight reduction in Recall due to its conservative prediction strategy. Challenges with DSWFNet include higher latency and Peak Alloc, inconsistent road labels, and topological breaks under occlusion or low contrast. To address these issues, we plan to employ lightweight backbone variants, incorporate uncertainty estimation and active learning, adopt topology-aware learning, and investigate multimodal fusion. These measures aim to improve deployment feasibility, robustness, and network connectivity while maintaining boundary quality. The approach can also be extended to building detection, medical image segmentation, machine vision, and change detection.

Data availability

The public datasets used in this study are the Massachusetts dataset and the CHN6-CUG dataset, both of which are publicly accessible for academic research purposes. The Massachusetts dataset can be downloaded from [https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~vmnih/data/](https:/www.cs.toronto.edu/~vmnih/data) (accessed in 2013). The CHN6-CUG dataset is available at [https://grzy.cug.edu.cn/zhuqiqi/zh\_CN/index/32366/list/index.htm](https:/grzy.cug.edu.cn/zhuqiqi/zh_CN/index/32366/list/index.htm) (accessed on May 25, 2021). The DSWFNet code will be released after the paper is accepted: [https://github.com/ZHANGKUNLUN001/DSWFNet](https:/github.com/ZHANGKUNLUN001/DSWFNet) .

References

Li, R., Zheng, S., Duan, C., Wang, L. & Zhang, C. Land cover classification from remote sensing images based on multi-scale fully convolutional network. Geo-spatial Inf. Sci. 25, 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/10095020.2021.2017237 (2022).

Wang, S., Cao, J. & Yu, P. S. Deep Learning for Spatio-Temporal Data Mining: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 34, 3681–3700. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2020.3025580 (2022).

Sravanthi Peddinti, A., Singh Chouhan, A. & Kumar Panigrahy, A. Road extraction using aerial images for future navigation. Mater. Today Proc. 6306–6308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.05.537 (2021).

Stewart, C., Lazzarini, M., Luna, A. & Albani, S. Deep learning with open data for desert road mapping. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12142274 (2020).

Gheidar-Kheljani, J. & Nasiri, M. M. A deep learning method for road extraction in disaster management to increase the efficiency of health services. Adv. Industrial Eng. 58, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.22059/aie.2024.367277.1880 (2024).

Pan, H., Jia, Y. & Lv, Z. An adaptive multifeature method for semiautomatic road extraction from High-Resolution stereo mapping satellite images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 16, 201–205. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2018.2870488 (2019).

Liu, P., Wang, Q., Yang, G., Li, L. & Zhang, H. Survey of road extraction methods in remote sensing images based on deep learning. PFG - J. Photogrammetry Remote Sens. Geoinf. Sci. 90, 135–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41064-022-00194-z (2022).

Zhou, M. et al. A boundary and topologically-aware neural network for road extraction from high-resolution remote sensing imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm Remote Sens. 168, 288–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2020.08.019 (2020).

Lu, X. et al. Cascaded Multi-Task road extraction network for road Surface, Centerline, and edge extraction. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2022.3165817 (2022).

Li, X. et al. SemID: blind image inpainting with semantic inconsistency detection. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 29, 1053–1068. https://doi.org/10.26599/TST.2023.9010079 (2024).

Zhu, X. X. et al. Deep learning in remote sensing: A comprehensive review and list of resources. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 5, 8–36. https://doi.org/10.1109/MGRS.2017.2762307 (2017).

Chen, L. C., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F. & Adam, H. Rethinking atrous convolution for semantic image segmentation. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1706.05587 (2017).

Chaurasia, A., Culurciello, E. & LinkNet exploiting encoder representations for efficient semantic segmentation. 2017 IEEE Visual Communications and Image Processing, VCIP. 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/VCIP.2017.8305148 (2017).

Zhou, L., Zhang, C. & Wu, M. D-LinkNet: LinkNet with pretrained encoder and dilated convolution for high resolution satellite imagery road extraction. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW). 192–1924. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW.2018.00034 (2018).

Akhtarmanesh, A. et al. Road extraction from satellite images using Attention-Assisted UNet. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs Remote Sens. 17, 1126–1136. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2023.3336924 (2024).

Yang, M., Yuan, Y., Liu, G. & SDUNet road extraction via spatial enhanced and densely connected UNet. Pattern Recognit. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2022.108549 (2022).

Wan, J. et al. A Dual-Attention network for road extraction from high resolution satellite imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs Remote Sens. 14, 6302–6315. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2021.3083055 (2021).

Chen, H. et al. A semi-supervised network for road extraction from remote sensing imagery via adversarial learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm Remote Sens. 198, 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2023.03.012 (2023).

Cui, X., Zhang, L. & Mamba -DCAU: state space dual attention center-sampling U-Net for hyperspectral image classification. Int. J. Remote Sens. 46, 5523–5547. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2025.2530237 (2025).

Zhang, X., Yuan, G., Hua, Z. & Li, J. T. S. M. G. A. Temporal-Spatial multiscale graph attention network for remote sensing change detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 18, 3696–3712. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2025.3526785 (2025).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2010.11929 (2020).

He, X. et al. Swin transformer embedding UNet for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2022.3144165 (2022).

Wu, H., Zhang, M., Huang, P., Tang, W. & CMLFormer CNN and multiscale Local-Context transformer network for remote sensing images semantic segmentation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs Remote Sens. 17, 7233–7241. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2024.3375313 (2024).

Zhang, X., Wang, Z., Li, J. & Hua, Z. M. V. A. F. G. Multiview fusion and advanced feature guidance change detection network for remote sensing images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 17, 11050–11068. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2024.3407972 (2024).

Merilaita, S., Scott-Samuel, N. E. & Cuthill, I. C. How camouflage works. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 372. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0341 (2017).

Cuthill, I. C. & Camouflage. J. Zool. 308, 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/jzo.12682 (2019).

Zhong, Y. et al. Detecting camouflaged object in frequency domain. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 4494–4503. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00446 (2022).

Li, J. et al. A Structure-Aware road extraction method for road connectivity and topology correction. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2024.3380914 (2024).

Yang, Y., Yuan, G., Li, J. & SFFNet: A wavelet-based spatial and frequency domain fusion network for remote sensing segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2024.3427370 (2024).

Li, X. et al. LCMorph: exploiting frequency cues and morphological perception for Low-Contrast road extraction in remote sensing images. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17020257 (2025).

Zhang, X. et al. Spatio-Temporal wavelet attention aggregation network for remote sensing change detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 18, 8813–8830. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2025.3551093 (2025).

Yang, Y. & Soatto, S. F. D. A. Fourier domain adaptation for semantic segmentation. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 4084–4094. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00414 (2020).

Zhu, C. et al. DBL-Net: A dual-branch learning network with information from Spatial and frequency domains for tumor segmentation and classification in breast ultrasound image. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2024.106221 (2024).

Wei, G. et al. Dual-Domain fusion network based on wavelet frequency decomposition and fuzzy Spatial constraint for remote sensing image segmentation. Remote Sens. 16, 3594 (2024).

Zhao, Q. et al. A fusion Frequency-Domain denoising and multiscale boundary attention network for sonar image semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2024.3492340 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Boundary-Aware Spatial and frequency Dual-Domain transformer for remote sensing urban images segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2024.3430081 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 11966–11976. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01167 (2022).

Mnih, V. Machine Learning for Aerial Image Labeling (University of Toronto (Canada), 2013).

Zhu, Q. et al. A global Context-aware and Batch-independent network for road extraction from VHR satellite imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm Remote Sens. 175, 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2021.03.016 (2021).

Wen, H. et al. Design and embedded implementation of secure image encryption scheme using DWT and 2D-LASM. Entropy 24 (2022).

Hou, Q., Zhou, D. & Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 13708–13717. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.01350 (2021).

Deng, Y., Yang, J., Liang, C., Jing, Y. & Spd-linknet upgraded D-linknet with strip pooling for road extraction. In: 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS. 2190–2193. https://doi.org/10.1109/IGARSS47720.2021.9553044 (2021).

Guo, H., Su, X., Wu, C., Du, B. & Zhang, L. Building-Road collaborative extraction from remote sensing images via Cross-Task and Cross-Scale interaction. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2024.3383057 (2024).

Ma, X., Zhang, X., Zhou, D., Chen, Z. & StripUnet A method for dense road extraction from remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 9, 7097–7109. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2024.3393508 (2024).

Yan, L., He, Z., Zhang, Z. & Xie, G. LS-MambaNet: integrating large strip Convolution and Mamba network for remote sensing object detection. Remote Sens. 17, 1721 (2025).

Hu, J., Shen, L. & Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 7132–7141. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00745 (2018).

Feng, S., Song, R., Yang, S. & Shi, D. U-net remote sensing image segmentation algorithm based on attention mechanism optimization. In: 2024 9th International Symposium on Computer and Information Processing Technology (ISCIPT). 633–636. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCIPT61983.2024.10672691 (2024).

Lin, T. Y., Goyal, P., Girshick, R., He, K. & Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 42, 318–327. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2858826 (2020).

Sudre, C. H., Li, W., Vercauteren, T. & Ourselin, S. & Jorge Cardoso, M. Generalised dice overlap as a deep learning loss function for highly unbalanced segmentations. Deep Learn. Med. Image Anal. Multimodal Learn. Clin. Decis. Support 240–248. (2017).

Zhao, H., Zhang, H. & Zheng, X. RFE-LinkNet: LinkNet with receptive field enhancement for road extraction from high Spatial resolution imagery. IEEE Access. 11, 106412–106422. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3320684 (2023).

Yang, R., Zhong, Y., Liu, Y., Lu, X. & Zhang, L. Occlusion-Aware road extraction network for High-Resolution remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2024.3387945 (2024).

Mahara, A. et al. Automated road extraction from satellite imagery integrating dense depthwise dilated separable Spatial pyramid pooling with DeepLabV3+. Appl. Sci. 15, 1027 (2025).

Gao, F., Fu, M., Cao, J., Dong, J. & Du, Q. Adaptive frequency enhancement network for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 63, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2025.3558472 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) and the Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) for their continuous support of this research. We are also grateful to the authors who have released their codes to the public, as this has significantly contributed to the advancement of academic research. Finally, we would like to express our sincere appreciation to the proof-readers and editors for their valuable assistance in improving the quality and clarity of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Geran Putra Inisiatif (GPI) fund (GPI /2024 /9794100).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Z. X.S. and A.A.; methodology, K.Z. W.Q. and A.A.; software, K.Z. and X.S.; validation, K.Z., and A.A.; formal analysis, K.Z. X.S. and A.A.H.; investigation, K.Z. and X.S.; resources, K.Z. X.S. and A.A.; data curation, K.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Z.; writing—review and editing, K.Z. A.A. and M.K.H.; visualization, K.Z. M.K.H. and X.S.; supervision, A.A. and X.S.; project administration, A.A. A.A.H. and W.Q.; funding acquisition, A.A. and W.Q.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, K., As’arry, A., Shen, X. et al. DSWFNet: dual-branch fusion of spatial and wavelet features for road extraction from remote sensing images. Sci Rep 16, 3966 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34091-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34091-3