Abstract

The international consensus classification or the World Health Organization classifications underrepresented driver alterations enriched in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML). To address this, we retrospectively characterized the genomic landscape of 105 pediatric patients with AML of East Asian ancestry using transcriptome and whole-exome sequencing (WES). In addition to the common recurrent fusions such as RUNX1::RUNX1T1 and CBFB::MYH11, we identified rearrangements involving KMT2A, NUP98, GLIS, as well as FLT3 and UBTF tandem duplications. The median somatic mutation rate in AML was 0.97 per megabase, as estimated by WES. Frequently mutated pathways included signaling: 68.6% (72/105), transcription: 37.1% (39/105), epigenetic regulation: 26.7% (28/105), cohesin: 7.6% (8/105), RNA binding: 3.8% (4/105), and protein modification: 5.7% (6/105). When analyzed together, high-risk genetic subtypes including GLISr, UBTF tandem duplications, PICALM::MLLT10, and HOXr were significantly associated with poorer 5 year overall survival (OS) in multivariable analysis (p-value = 0.037). Although FLT3 internal tandem duplications were significantly associated with inferior 5 year OS in univariable analysis, this effect was not significant in multivariable analysis (p-value = 0.382). Patients with RUNX1 mutations had inferior 5 year OS in multivariable analysis (p-value = 0.009). These findings suggest specific genomic alterations that may refine risk stratification and guide future therapeutic protocols in Taiwanese pediatric patients with AML.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) accounts for approximately 15–20% of childhood leukemia cases. Despite the widespread use of cytogenetics, genetic aberrations and the assessment of treatment response by minimal residual disease for risk stratifications in pediatric AML protocols1,2,3,4,5, about 30% of children with AML still experience treatment failure. While outcomes for low-risk pediatric AML have improved significantly over recent decades, high-risk AML in children remains associated with an adverse prognosis despite intensified chemotherapy1,6. The inherent heterogeneity of AML—reflected in the diversity of blast morphology, surface markers, and cytogenetic and genetic alterations—continues to pose a major challenge to effective treatment7.

The rapid identification of novel recurrent somatic mutations in adult patients with AML through next-generation sequencing has greatly advanced molecular classifications. The first recurrent somatic mutations identified were in the IDH1 gene and its related gene IDH2, discovered via whole genome sequencing. This was soon followed by the identification of a frameshift mutation in the DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A, observed in the first two patients studied8,9. Subsequent unbiased genome and exome sequencing revealed mutations in core RNA spliceosome genes——including SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2—in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS)10. These spliceosome mutations are present in 7% of de-novo adult AML and 50% of secondary AML arising from MDS11,12. Additionally, mutations in the multiprotein cohesin complex, such as RAD21, SMC1A, SMC3, and STAG2, occur in 10–15% of AML cases13,14. The discovery of these molecular genetic alterations, together with established cytogenetic abnormalities and genetic alterations, has contributed to refining the prognostic classification system in AML15,16,17,18.

Following the identification of recurrent genomic alterations in adult AML, several studies focusing on the pediatric population have revealed that gene mutations are significantly less frequent in pediatric AML compared to those in adult cases19,20,21,22. The use of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), has highlighted that chromosomal translocations are more prevalent in pediatric patients, especially among younger children23,24. Notably, rearrangements involving KMT2A, as well as fusions with NUP98, members of the GLIS gene family, and UBTF tandem duplications (UBTF-TDs), are enriched in pediatric AML but are less in adult patients25,26,27,28. These molecular distinctions underscore the need for dedicated studies to better understand pediatric AML.

Recent AML classification systems, including the International Consensus Classification (ICC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) classification, have primarily been based on recurrent chromosomal translocations and genetic alterations identified over the past 15 years29,30. However, the utility of these frameworks to clinical risk stratification in pediatric patients remains insufficiently studied. Many newly identified recurrent driver alterations are still classified as “AML with other defined genetic alterations” under the WHO classification, or as “AML, not otherwise specified” in the ICC system. Although Umeda et al.31 conducted a comprehensive analysis of previously published samples—primarily from individuals of European ancestry—and defined 23 distinct molecular subtypes based on specific mutations, these proposed subtypes require further validation in populations of non-European ancestry, such as those of East Asian descent. Therefore, the aim of this study was to apply a similar classification strategy to pediatric AML cases in Taiwan and to examine the association between genetic alterations and clinical outcomes in this population.

Results

Patient cohort

Clinical features and major molecular subtypes are summarized in Table 1. A total of 105 pediatric patients with AML of East Asian ancestry (59 men, 46 women) were included in the study. The median age of onset was 11.55 years (range: 0.11–17.75). Initial white blood cell (WBC) counts were below 100 × 103/μL in 79% of patients, with a median WBC count of 21.58 × 103/μL. According to French–American–British (FAB) classification, the most common subtype was M2 (44.9%), followed by M4 and M5. The FAB subtype was unknown in four cases (Supplementary Fig. 1). Available cytogenetic data were consistent with the results of transcriptome analysis.

Molecular classification of AML by transcriptome analysis

To genetically characterize AML according to the ICC or WHO 2022 criteria, RNA-seq and whole-exome sequencing (WES) data were used. RNA-seq was employed to assess gene expression profiles and detect fusion transcripts, enabling the identification of specific AML subtypes. Tumor-only whole-transcriptome RNA-seq were performed on all 105 patients. Tumor-germline WES were performed on 61 patients, and tumor-only WES data were available for 43 samples. Pathogenic fusions or structural variants were systematically screened, with most of these genetic alterations being class-defining for AML. Notably, 80% of patients had subtype-defined fusions such as KTM2Ar, RUNX1::RUNX1T1, CBFB::MYH11, and NUP98r. Subtypes of NPM1r and CEBPA mutations were also identified. According to a recent publication by Umeda et al.31, other subtypes identified included UBTF-TD, GATA1, and MECOMr (Table 2)31. One rare fusion involving NPM1r was demonstrated in the Supplementary Fig. 2.

Transcriptomic analysis of 105 AML RNA-seq samples revealed distinct molecular subgroups within the disease. Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) based on the top 1,000 most variable genes identified three clearly separable subtypes—RUNX1::RUNX1T1, PML::RARA (acute promyelocytic leukemia [APL]), and CBFB::MYH11—while the remaining subtypes are not distinctly separated by gene expression alone (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table 1). This pattern was consistent when using 351, 500, 1000 or 2000 top gene expression (Supplementary Fig. 3). Heatmap clustering of 13 AML subtypes with at least three samples confirmed distinct expression patterns for these three subtypes and highlighted a fourth cluster corresponding to KMT2Ar AML (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table 2 for differentially expressed genes across 13 AML subtypes). Subtype-specific genes with top elevated expression were identified for each of these four groups (Fig. 1C–F). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of 50 Hallmark pathways, based on differentially expressed genes for each of four subtypes (RUNX1::RUNX1T1, APL, CBFB::MYH11 and KMT2Ar) compared to all other subtypes as controls, was demonstrated in Fig. 1G (Supplementary Table 3).

Integrative RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) tumors. (A) Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction (UMAP) plot based on the top 1,000 most variable genes from 105 AML tumor RNA-seq samples. The analysis reveals three major AML subtypes, including RUNX1::RUNX1T1, APL (acute promyelocytic leukemia), and CBFB::MYH11, which are clearly separable from the others, while the remaining subtypes are not distinctly distinguished by gene expression alone. (B) Heatmap showing subtype-level gene expression profiles (column-wise normalized log₂[CPM]) across 13 AML subtypes with at least three samples (see Supplementary Table 1 for differentially expressed genes across 13 AML subtypes) Consistent with (A), although only the same three subtypes are apparently separated, the cluster branches specific to four AML subtypes, comprising RUNX1::RUNX1T1 (n = 25), APL (n = 7), CBFB::MYH11 (n = 9), and KMT2Ar (n = 14) , are highlighted in different colors. (C–F) Top genes with higher expression in each of these four AML subtypes are shown. (G) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of 50 Hallmark pathways based on differentially expressed genes for each of four subtypes highlighted in (B) compared to all other subtypes as controls.

We compared gene set enrichment profiles between the NTU cohort and the dataset reported by Umeda et al. (NG cohort)31 for RUNX1::RUNX1T1, APL, KMT2Ar, and CBFB::MYH11 subtypes, particularly focusing on gene sets with upregulated genes in each major subtype (see method for details). A total of 193 gene sets were commonly upregulated and reproducibly enriched (FDR q < 0.05) in both cohorts. Clustering by normalized enrichment score (NES) revealed distinct subtype-associated patterns (Supplementary Fig. 4A). CBFB::MYH11 exhibited predominant enrichment of 12 gene sets, including KRAS oncogene signature and TRIM24 target up (Supplementary Fig. 4B). KMT2Ar and CBFB::MYH11 shared 40 gene sets linked to immune and cancer-related pathways (Supplementary Fig. 4C). RUNX1::RUNX1T1 showed five uniquely enriched gene sets (Supplementary Fig. 4D). APL demonstrated selective enrichment of Targets of IGF1 and IGF2 up and shared Basement membranes enrichment with RUNX1::RUNX1T1 (Supplementary Fig. 4E). Additional clusters of gene sets (n = 71) enriched primarily in CBFB::MYH11 but also observed in other subtypes were demonstrated in the Supplementary Fig. 4F–H.

Somatic mutations determined by WES

Putative driver mutations were identified from tumor–germline matched samples using multiple somatic variant callers, including Mutect2 (v4.1.2.0)32, SomaticSniper (v1.0.5.0)33, VarScan2 (v2.4.3)34, MuSE (v1.0rc)35, and Strelka2 (v2.9.10)36. The median somatic mutation rate across the cohort was 0.97 mutations per megabase (Mb), and the tumor mutation burden for available samples and molecular subtypes are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. Identified mutations were categorized into six functional pathways commonly implicated in the pathogenesis of pediatric AML, including signaling pathways, transcription factors, epigenetic regulators, RNA-binding proteins, the cohesin complex, cell cycle regulators, and protein modification pathways (Fig. 2). This classification was majorly based upon the report of Umeda et al.31. Frequently mutated pathways included signaling (68.6%, 72/105), transcription factors (37.1%, 39/105), epigenetic regulators (26.7%, 28/105), the cohesin complex (7.6%, 8/105), protein modification (5.7%, 6/105), and RNA-binding proteins (3.8%, 4/105).

Genomic Landscape and WHO Classification of Pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML). This figure summarizes the genomic landscape of pediatric AML with a focus on key genetic alterations identified through Genomic Random Interval analysis. Genetic mutations are illustrated across six mutated pathways: signaling, transcription factors, epigenetic regulators, cohesin complex, protein modification, and RNA-binding proteins. The genetic subtypes are categorized according to the WHO 2022 5th edition of the classification. The risk stratification was determined by classification framework proposed by Umeda et al31. WHO, World Health Organization; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; FAB, French–American–British; WES, whole-exome sequencing; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing

Signaling pathway mutations were identified in 80% (20/25) of patients with RUNX1::RUNX1T1 and in 89% (8/9) of patients with CBFB::MYH11. Notably, 11 c-KIT mutations were detected in 10 patients with RUNX1::RUNX1T1, representing 40% of this subtype, and in one patient with CBFB::MYH11. Further Fisher’s exact test revealed that c-KIT mutations were significantly enriched in CBF AML than in other genetic subtypes (P < 0.0001). ASXL1 or ASXL2 mutations were identified in 7 of 25 patients with RUNX1::RUNX1T1, but were absent in CBFB::MYH11 cases and detected in only 3 of 71 patients in other genetic subtypes. Overall, two ASXL1 and five ASXL2 mutations were significantly enriched in RUNX1::RUNX1T1 cases compared with those in all other subtypes combined (28% vs 3.8%, Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.001, odds ratio = 9.68). In addition, NRAS mutations were detected in 36% (5 of 14) of patients harboring KMT2Ar. Two ASXL2 and one ASXL1 mutations were identified in this group. Overall, RUNX1::RUNX1T1 exhibited a high enrichment of epigenetic mutations (56%) compared to CBFB::MYH11 (0%) and KMT2Ar (21.4%) (p = 0.0046, Fisher‘s exact test). In contrast, the signaling pathway did not show significant differences between the three genetic types. Similarly, there were no significant differences in the transcription factor and cohesin pathways, with all three mutation groups showing relatively low and comparable frequencies. Another heatmap focusing upon these three genetic subtypes were shown in the Supplementary Fig. 6.

FLT3 alterations were identified in 23 patients (21.9%), including 18 with FLT3 internal tandem duplications (FLT3-ITD; 17.1%), three with FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain mutations, and two with non-canonical FLT3 mutations (1.9%). These alterations were most prevalent in patients with NPM1 mutations (75%, 3/4), NUP98r (50%, 6/12), and DEK::NUP214 fusions (100%, 4/4). Additionally, five patients harbored RUNX1 mutations. A schematic of the RUNX1 protein domains and annotated mutations is presented in Supplementary Fig. 7. Another rare somatic mutations of USP9X were identified in two patients. The difference of clinical features, including initial white cell counts, cytogenetics and FAB classification of patients with FLT3-ITD and RUNX1 mutations was summarized in the Supplementary Table 4.

Tumor mutational signature in pediatric AML

Mutational signatures were constructed across all pair samples using WES. The most prevalent signatures identified in this cohort were COSMIC signatures 1, 5, and 6, observed across nearly all AML subtypes. According to Cosmic v10237, Signature 1 and Signature 5 are classified as clock-like mutational signatures, both correlating with the age of the individual. Notably, signature 5 has also been associated with bladder cancer harboring ERCC2 mutations and cancers linked to tobacco smoking38. Signature 3, indicative of defective homologous recombination repair, was also detected and is known to be strongly associated with biallelic inactivation of BRCA1 and BRCA239. Consistent with previous studies, AML subtypes with more than three samples in this cohort typically exhibited a combination of signatures 1 and 540. No strong subtype-specific mutational signatures were detected, likely due to the limited sample size and the restriction of WES to coding regions only (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Impacts of genetic subtypes on clinical outcomes

In accordance with previous reports and limited case numbers of some subtypes, we combined the high-risk genetic subtypes, including UBTF-TD, GLISr, PICALM::MLLT10, and HOXr as a single high-risk category due to limited case numbers in each subtype. Subtypes represented by only one case, such as KMT2A-PTD and MECOMr, were excluded from the survival analysis. We then focused our comparison on subtypes including RUNX1::RUNX1T1, NPM1r, KTM2Ar, CBFB::MYH11, GATA1, CEBPA, and DEK::NUP214—as well as the combined group of the above high-risk patients, which was analyzed as a single high-risk category. The 5 year event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) for each molecular type are presented in Supplementary Fig. 9 with event-free survival at a borderline significance (p = 0.06, Supplementary Fig. 9A) and statistically significant difference in overall survival (p = 0.034, Supplementary Fig. 9B). The high-risk genetic subtypes were significantly associated with poorer 5 year OS in multivariable analysis (p = 0.037, adjusted hazard ratio (HR) = 7.27, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.13–46.69) although the poorer 5 year EFS was not significant in multivariable analysis (p = 0.255, adjusted HR = 4.91, 95% CI: 0.32–76.25) (Supplementary Table 5–1 and 5–2).

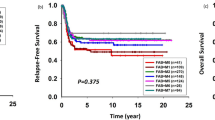

Additional prognostic markers provided by somatic mutations

The 5-year OS rate was significantly lower in patients with FLT3-ITD mutations (33.86%; 95% CI, 17.06–67.23) than in those without the mutation (65.96%; 95% CI, 55.63–78.21; p = 0.0066). The 5-year EFS was also poorer among patients with FLT3-ITD, although the difference showed borderline statistical significance (p = 0.058) (Fig. 3A and B). However, FLT3-ITD did not remain a significant factor in the multivariable analysis ((Supplementary Table 6–1 and 6–2). Patients with RUNX1 mutations had significantly inferior 5 year EFS and OS rates compared with those without the mutations (EFS: 0.0%; 95% CI, 0.0–0.0% vs. 51.70%; 95% CI, 42.02–63.60; p = 0.013; OS: 0.0%; 95% CI, 0.0–0.0% vs. 62.35%; 95% CI, 52.71–73.75%; p = 0.00057) (Fig. 3C and D). RUNX1 mutations remained a significant adverse prognostic factor in the multivariable analysis (p = 0.009; HR, 5.09; 95% CI, 1.51–17.14) (Supplementary Table 7–1 and 7–2). Although c-KIT mutations in RUNX1::RUNX1T1 were associated with a higher risk of relapse, it did not reach statistical significance in this cohort.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of 5 year event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) according to FLT3-ITD and RUNX1 mutation status (A, B) Patients with FLT3-ITD mutations showed significantly lower 5 year OS rates compared with those without the mutation (p = 0.007) and a trend toward poorer EFS (p = 0.058). (C, D) Patients with RUNX1 mutations demonstrated markedly inferior 5 year EFS and OS compared with wild-type cases (p = 0.013 and p = 0.0006, respectively). Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test.

Discussion

Although the cohort was relatively small due to the rarity of pediatric AML, RNA-Seq analysis enabled the identification of several recently recognized novel genetic subtypes, including ETS, UBTF-TD, GLISr, and GATA1. The clinical outcomes varied among different genetic subtypes. FLT3-ITD mutations may help identify patients who could benefit from targeted therapy; however, such treatments are currently not approved for pediatric AML in Taiwan. While RUNX1 mutations are less common in pediatric AML, their presence was associated with worse outcomes.

In the current ICC and WHO classifications, many fusion genes enriched in pediatric AML have yet to be assigned into distinct categories29,30. Our pediatric cohort identified several rare, high-risk AML subtypes. AML with NUP98r has been confirmed as high-risk in multiple pediatric studies due to its association with an increased risk of relapse27,28. Most cases of AML with KMT2Ar are also considered high-risk, though prognosis may vary depending on the fusion partner gene31. AML with GLISr, first described by Tanja et al.25. in acute megakaryocytic leukemia (AMKL), is not currently defined as a distinct molecular subtype in the ICC or WHO classifications25. The recently discovered UBTF-TDs, initially identified in pediatric AML, have also been reported in adults and are associated with poor prognosis26,41. When analyzed together, the high-risk genetic subtypes including GLISr, UBTF-TDs, PICALM::MLLT10, and HOXr were significantly associated with poorer 5 year OS in multivariable analysis. The identification of these high-risk genetic fusions in pediatric AML is crucial not only for refined risk classification but also for enabling clinical trials of novel targeted agents in these subtypes. In the Children’s Oncology Group trial, treatment by Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin significantly improved EFS in pediatric AML with KMT2Ar, though OS remained unchanged42. Menin inhibitors represent another promising therapeutic class and may be effective in patients harboring KMT2Ar, NPM1 mutations, NUP98r, or UBTF-TDs43,44,45. Recent preclinical studies have further elucidated that CBFA2T3::GLIS2-associated AMKL is critically dependent on apoptotic pathways mediated by the BCL2 and BCL-xL proteins. This dependence highlights the therapeutic potential of targeting these pathways using venetoclax and navitoclax, respectively46. Venetoclax, which selectively inhibits BCL2, may be effective when combined with chemotherapy in some patients with relapsed CBFA2T3::GLIS2 AMKL47. Collectively, these early findings provide hope that novel, targeted therapies will improve outcomes for children with high-risk genetic subtypes of AML48.

Faber et al.49 utilized whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing to characterize RUNX1::RUNX1T1 (n = 85) and CBFB::MYH11 (n = 80) AML, identifying NRAS as the most frequently mutated gene in CBF-AMLs. They also observed enrichment of c-KIT exon 17 mutations in the RUNX1::RUNX1T1 cohort (p = 0.005), which correlated with poorer outcomes (p = 0.01), and reported that frameshift mutations in ASXL2 were common and exclusive to RUNX1::RUNX1T1 cases. In the present cohort, ASXL1/ASXL2 and c-KIT mutations were similarly enriched in RUNX1::RUNX1T1 AML, consistent with previous reports. While c-KIT mutations have been associated with inferior prognosis in CBF-AML in prior studies, this association was not observed in our cohort50,51,52. Beyond genetic fusion subtypes, several somatic genetic alterations also warrant consideration in risk stratification for pediatric AML. Although patients harboring FLT3-ITD tend to exhibit poorer outcomes, this difference did not reach statistical significance in multivariable analyses within our cohort. Nevertheless, multiple international pediatric trials have demonstrated that the addition of sorafenib, a FLT3 inhibitor, may improve outcomes for patients with FLT3-ITD53. Expanding government-funded access to FLT3 inhibitors in regions such as Taiwan could provide substantial clinical benefit for this population. RUNX1 mutations represent another adverse prognostic marker, consistently associated with higher rates of treatment failure across both pediatric and adult AML cohorts54,55,56. In a Japanese cohort of 503 pediatric patients with AML, RUNX1 mutations were identified in 2.8% of cases and correlated with poor clinical outcomes, findings of which are in line with our data60. Another rare USP9X somatic mutations were identified in two patients. USP9X was identified as a female-specific B-ALL susceptibility gene associated with multiple congenital anomalies57. In sporadic pediatric B-ALL, USP9X acts as a tumor suppressor gene in both sexes57. In AML, the inhibition of USP9X induces apoptosis in FLT3-ITD positive cells58. However, the impacts or pathogenesis of USP9X somatic mutations might need further investigations.

This study has certain limitations. First, the cohort size was relatively small, which may have limited the detection of rare subtypes and reduced the statistical power of the survival analyses. Second, our previous analysis of treatment outcomes in pediatric AML showed that patients with low-risk genetic subtypes, particularly RUNX1::RUNXT1 and CBFB::MYH11, experienced poorer outcomes than those reported in other international studies. This discrepancy may have confounded the identification of certain genetic prognostic markers in the present study59. A prospective clinical trial to use a larger cohort size with the same genetic tools might be indicated in the future.

In conclusion, our findings are consistent with previous studies and highlight transcriptome analysis as a valuable tool for molecular subtyping in pediatric AML. Patients harboring high-risk genetic subtypes exhibited poorer outcomes compared to those with low-risk subtypes. Specifically, patients with FLT3-ITD mutations may benefit from targeted therapies, which necessitates government support in Taiwan. Additionally, patients with RUNX1 mutations showed particularly dismal outcomes, indicating a need for novel therapeutic agents or alternative treatment strategies. Finally, integrating minimal residual disease monitoring could enhance risk-adapted protocol design for pediatric patients with AML in Taiwan in the future60,61,62.

Methods

Patients and protocols

AML diagnosis was established based on morphological analysis of bone marrow or peripheral blood, combined with immunophenotyping using multiple combinations of monoclonal antibodies and cytogenetic studies. Between January 1997 and December 2019, a total of 105 pediatric patients with AML were enrolled. All patients received treatment according to the previously described TPOG AML-97A protocol59,63. The FAB classification system was used to determine AML morphological subtypes. Karyotypes were interpreted according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Beginning in 2012, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assays were used to screen for two common fusion transcripts: RUNX1::RUNX1T1 and CBFB::MYH11. All patients underwent morphological, immunophenotypic, and cytogenetic analyses.

The Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions approved the protocols, and the patients, parents, or guardians signed the written informed consent, as appropriately. The TPOG-AML-97A protocol has been published in detail previously59,63.

DNA and RNA extraction

Total RNA was extracted from leukemic cells using NucleoZOL (Macherey–Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, while genomic DNA was extracted using standard phenol/chloroform-based methods. These procedures have been described in detail previously64,65,66. Briefly, one million cells were lysed overnight using lysis buffer. PureLink RNase A (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) was added to degrade total RNA, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 10 min. An equal volume of phenol–chloroform–isopropanol (25:24:1) was then vigorously mixed with the lysate, followed by centrifugation at 16,100 × g at 4 °C for 5 min. The upper aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh tube, and genomic DNA was precipitated by adding two volumes of pure ethanol pre-chilled to –80 °C. The DNA pellet was washed with 75% ethanol and rehydrated in Tris–EDTA buffer.

FLT3-ITD determined by DNA-PCR

FLT3-ITDs were detected by PCR amplification of genomic DNA using the following primers: forward (F) 5′-GCAATTTAGGTATGAAAGCCAGC-3′ and reverse (R) 5′-CTTTCAGCATTTTGACGGCAACC-3′20,67. The 50 μL reaction mixture contained approximately 500 ng of genomic DNA and 10 pmol of each primer. Samples were amplified using standard PCR conditions and PCR products were resolved on a 2% agarose gel alongside positive and negative controls.

Transcriptome sequencing and bioinformatic analyses

The TruSeq library preparation kit and the HiSeq 2000 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) were used for RNA sequencing. The sequence reads were paired-end, 150 base pairs (bp) in length. All software were run using default parameters on a high-performance computing environment, and fastq files were mapped and aligned to GRCh38 human genome reference by STAR v2.5.3a68. Gene annotation downloaded from the Ensembl website (http://www.ensembl.org/) on January 1, 2023, was used for STAR mapping and subsequent read-count evaluation. The bioinformatics tools for fusion calling include Cicero69, STAR-Fusion (v1.8.1)68, FusionCatcher (1.2.0)70, squid (1.5)71, pizzly (0.37)72, arriba (1.2.0)73, and Pindel (0.2.0)74, with the combined approach of the latter, Arriba, and Cicero specifically used to search for the internal tandem duplication75.

UMAP analysis

STAR68 aligned GRCh38 RNA-seq BAM files of 105 AML samples were calculated for gene read counts using RSEM76. The resulting count was further transformed into log2(cpm) using the Limma Voom R package77. UMAP for dimension reduction78 with default setting (n components = 2, n neighbors = 15, and min distance = 0.3) was conducted using the top 1000 variable genes that were selected using the median absolute deviation method, as described by Umeda et al31.

Identifying differentially expressed genes and enriched gene sets for each major subtype

A read count matrix for 105 AML RNA-seq samples (log₂[CPM]) was generated using the Limma Voom pipeline77. Differential gene expression analysis was then performed for each AML subtype (with n ≥ 3 samples) compared to all remaining samples combined as the control group. In the NTU cohort, two subtypes were dominant, including RUNX1::RUNX1T1 (n = 25) and KMT2Ar (n = 14), while other subtypes, such as CBFB::MYH11 (n = 9) and APL (n = 7), had fewer samples. Due to this imbalance, differential expression analyses using a simple “subtype vs. others” design may result in biased detection of genes that are lowly expressed in minority subtypes but highly expressed in the dominant ones. To minimize such bias and better capture subtype-specific expression patterns, we focused only on upregulated genes within each subtype. This approach reduces the likelihood of identifying genes upregulated in major subtypes but downregulated in minor ones, ensuring that the selected genes are more informative for distinguishing subtypes.

For each subtype, genes significantly upregulated at FDR q < 0.01 were selected. The mean expression of these genes across all samples was clustered and visualized using the MATLAB (version 2025b) function clustergram, which allows interactive selection and coloring for major subtype-specific clusters. Through this supervised clustering approach, we identified sets of highly expressed genes corresponding to four major AML subtypes with distinct clustering branches: RUNX1::RUNX1T1, CBFB::MYH11, APL, and KMT2Ar. These genes were further visualized in separate heatmaps to highlight top differentially upregulated genes among these subtypes.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using the GSEA software with MSigDB human gene sets: H (hallmark, n = 50) and C2 (curated, n = 7,561)79. Since only the four major subtypes, comprising RUNX1::RUNX1T1, CBFB::MYH11, APL, and KMT2Ar, showed clear subtype-specific expression clusters in previous clustering analysis, GSEA was focused on pathways enriched in upregulated genes within these subtypes.

To assess reproducibility, the GSEA results from the NTU cohort were compared with those reported by Umeda et al.31 for the NG cohort. Although Umeda et al. did not provide raw expression matrices or DEG lists for their 887 AML samples, they published GSEA results (based on MSigDB C2 gene sets) obtained using a similar case–control design. We therefore overlapped the top enriched and upregulated gene sets (FDR < 0.05) from both NTU and NG cohorts to identify replicable, subtype-enriched pathways for the four major subtypes.

Finally, gene sets significantly enriched and upregulated (FDR < 0.05) in both NTU and NG cohorts (n = 193) were clustered using MATLAB clustergram function based on their normalized effect sizes (NES) of enrichment. Sub-branches showing distinct or shared enrichment patterns across subtypes were colored and visualized in individual heatmaps to facilitate comparison of subtype-specific and common biological pathways.

WES

The SureSelect Human All Exon 50 Mb or 38 Mb kit (Agilent) was used for library preparation, targeting a sequencing depth of 120 × . Paired-end sequencing (2 × 150 bp) was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 instrument. Sequencing adapters and low-quality reads—defined as reads where more than 50% of bases had a Phred quality score below 5—were removed. The remaining high-quality reads were aligned to the reference human genome (GRCh38). Variant sites differing from the reference genome were then independently identified in each sample26. Somatic variants were called by paired analysis of diagnosis-germline samples. For 41 tumor WES samples without matched germline samples, we performed tumor-only variant calling using Mutect280, with a panel of normal samples (n = 96) aggregated internally at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital80. To exclude non-rare SNPs, we excluded variants observed in gnomAD (v3.1.2)81 with population-level allele frequency > 0.01 among any of four major populations, including European, East Asian, South Asian, and African populations. Variant annotation was performed using ANNOVAR80, and coding mutations that potentially disrupt protein coding sequences were further underwent manual assessment and evaluation of read depth, mapping quality, and strand bias, in order to eliminate additional artifacts82.

Statistics

Complete remission (CR) was defined as trilineage hematopoietic recovery with less than 5% blasts in the bone marrow. Failure to achieve CR after two courses of induction chemotherapy was considered refractory disease. Relapsed disease was defined as recurrence after an initial CR. Secondary malignancies were categorized as separate events. Risk classification was based on the criteria described by Umeda et al. and prior cohort studies31. Patients were classified as high-risk if they had one of the following alterations: UBTF-TD, GLISr, PICALM::MLLT10 or HOXr. Samples represented by a single case, including KMT2A-PTD and MECOMr were excluded for survival analysis, as were patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Differences in mutation frequencies between subgroups were evaluated using Fisher’s exact test. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. OS was defined as the time from the start of treatment to death from any causes. EFS was defined as the time from the start of treatment to relapse or death from any causes. Patients who did not achieve first remission were assigned an EFS of zero. Patients without an event were censored at their last follow-up. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Survival rates are reported as mean percentages ± standard deviation. Cox proportional hazard models were constructed for EFS and OS, with covariates, including sex, white blood cells (< 10 × 103/μL, or > 100 × 103/μL). All statistical analyses, unless otherwise specified, were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Data availability

The data used for this study will be made available to other researchers upon reasonable request.

References

Zwaan, C. M. et al. Collaborative efforts driving progress in pediatric acute Myeloid Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 2949–2962. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.62.8289 (2015).

Rubnitz, J. E. & Inaba, H. Childhood acute myeloid leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 159, 259–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.12040 (2012).

Rubnitz, J. E. et al. Minimal residual disease-directed therapy for childhood acute myeloid leukaemia: Results of the AML02 multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 11, 543–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70090-5 (2010).

Lange, B. J. et al. Outcomes in CCG-2961, a Children’s Oncology Group Phase 3 Trial for untreated pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Blood 111, 1044–1053. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-04-084293 (2008).

Egan, G., Chopra, Y., Mourad, S., Chiang, K. Y. & Hitzler, J. Treatment of acute myeloid leukemia in children: A practical perspective. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 68, e28979. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.28979 (2021).

Reedijk, A. M. J. et al. Improved survival for children and young adolescents with acute myeloid leukemia: A Dutch study on incidence, survival and mortality. Leukemia 33, 1349–1359. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-018-0314-7 (2019).

Shimony, S., Stahl, M. & Stone, R. M. Acute Myeloid Leukemia: 2025 Update on Diagnosis, Risk-Stratification, and Management. Am. J. Hematol. 100, 860–891. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.27625 (2025).

Mardis, E. R. et al. Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. N Engl J Med 361, 1058–1066. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0903840 (2009).

Ley, T. J. et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 2424–2433. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1005143 (2010).

Yoshida, K. et al. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature 478, 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10496 (2011).

Chiara, C. et al. Clinical significance of chromatin-spliceosome acute myeloid leukemia: A report from the Northern Italy Leukemia Group (NILG) randomized trial 02/06. Haematologica 106, 2578–2587. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2020.252825 (2021).

Lachowiez, C. A. et al. Impact of splicing mutations in acute myeloid leukemia treated with hypomethylating agents combined with venetoclax. Blood Adv. 5, 2173–2183. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2020004173 (2021).

Thol, F. et al. Mutations in the cohesin complex in acute myeloid leukemia: Clinical and prognostic implications. Blood 123, 914–920. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-07-518746 (2014).

Thota, S. et al. Genetic alterations of the cohesin complex genes in myeloid malignancies. Blood 124, 1790–1798. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-04-567057 (2014).

Ley, T. J. et al. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 368, 2059–2074. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1301689 (2013).

Papaemmanuil, E. et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 2209–2221. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1516192 (2016).

Döhner, H. et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood 140, 1345–1377. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2022016867 (2022).

Duncavage, E. J. et al. Genome sequencing as an alternative to cytogenetic analysis in Myeloid cancers. N Engl. J. Med. 384, 924–935. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2024534 (2021).

Liang, D.-C. et al. Cooperating gene mutations in childhood acute myeloid leukemia with special reference on mutations of ASXL1, TET2, IDH1, IDH2, and DNMT3A. Blood 121, 2988–2995. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-06-436782 (2013).

Andersson, A. K. et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in pediatric acute leukemia. Leukemia 25, 1570–1577. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2011.133 (2011).

Oki, K. et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are rare in pediatric myeloid malignancies. Leukemia 25, 382–384. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2010.307 (2011).

Shiba, N. et al. DNMT3A mutations are rare in childhood acute myeloid leukaemia, myelodysplastic syndromes and juvenile myelomonocytic leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 156, 413–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08879.x (2012).

Bolouri, H. et al. The molecular landscape of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia reveals recurrent structural Alterations and age-specific mutational interactions. Nat. Med. 24, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4439 (2018).

Shiba, N. et al. Transcriptome analysis offers a comprehensive illustration of the genetic background of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 3, 3157–3169. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000404 (2019).

Gruber, T. A. et al. An Inv(16)(p13.3q24.3)-encoded CBFA2T3-GLIS2 fusion protein defines an aggressive subtype of pediatric acute megakaryoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell 22, 683–697, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.007 (2012).

Umeda, M. et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies UBTF tandem duplications as a recurrent lesion in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Cancer Discov. https://doi.org/10.1158/2643-3230.Bcd-21-0160 (2022).

Bertrums, E. J. M. et al. Comprehensive molecular and clinical characterization of NUP98 fusions in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 108, 2044–2058. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2022.281653 (2023).

Struski, S. et al. NUP98 is rearranged in 3.8% of pediatric AML forming a clinical and molecular homogenous group with a poor prognosis. Leukemia 31, 565–572. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2016.267 (2017).

Arber, D. A. et al. International consensus classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and acute Leukemias: Integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood 140, 1200–1228. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2022015850 (2022).

Khoury, J. D. et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia 36, 1703–1719, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-022-01613-1 (2022).

Umeda, M. et al. A new genomic framework to categorize pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Genet. 56, 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-023-01640-3 (2024).

Cibulskis, K. et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2514 (2013).

Larson, D. E. et al. SomaticSniper: Identification of somatic point mutations in whole genome sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 311–317. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr665 (2012).

Koboldt, D. C. et al. VarScan 2: Somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome. Res. 22, 568–576. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.129684.111 (2012).

Fan, Y. et al. MuSE: Accounting for tumor heterogeneity using a sample-specific error model improves sensitivity and specificity in mutation calling from sequencing data. Genome. Biol. 17, 178. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-1029-6 (2016).

Kim, S. et al. Strelka2: Fast and accurate calling of germline and somatic variants. Nat. Methods 15, 591–594. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-018-0051-x (2018).

Alexandrov, L. B. et al. Clock-like mutational processes in human somatic cells. Nat. Genet. 47, 1402–1407. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3441 (2015).

Kim, J. et al. Somatic ERCC2 mutations are associated with a distinct genomic signature in urothelial tumors. Nat. Genet. 48, 600–606. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3557 (2016).

Alexandrov, L. B. et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500, 415–421. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12477 (2013).

Brandsma, A. M. et al. Mutation signatures of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia and normal blood progenitors associated with differential patient outcomes. Blood Cancer Discov. 2, 484–499. https://doi.org/10.1158/2643-3230.Bcd-21-0010 (2021).

Duployez, N. et al. UBTF tandem duplications define a distinct subtype of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 37, 1245–1253. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-023-01906-z (2023).

Gibson, B. et al. Favourable outcomes in newly diagnosed paediatric AML with Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin and risk-stratified therapy: Results from the International Phase III Myechild 01 Trial. Blood 144, 968. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2024-198419 (2024).

Barajas, J. M. et al. Acute myeloid leukemias with UBTF tandem duplications are sensitive to menin inhibitors. Blood 143, 619–630. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2023021359 (2024).

Cuglievan, B. et al. Menin inhibitors in pediatric acute leukemia: a comprehensive review and recommendations to accelerate progress in collaboration with adult leukemia and the international community. Leukemia 38, 2073–2084. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-024-02368-7 (2024).

Issa, G. C. et al. The menin inhibitor revumenib in KMT2A-rearranged or NPM1-mutant leukaemia. Nature 615, 920–924. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05812-3 (2023).

Neault, M. et al. CBFA2T3-GLIS2-dependent pediatric acute megakaryoblastic leukemia is driven by GLIS2 and sensitive to navitoclax. Cell Rep 42, 113084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113084 (2023).

Mishra, A. K., Mullanfiroze, K., Chiesa, R. & Vora, A. Azacitidine and venetoclax for post-transplant relapse in a case of CBFA2T3/GLIS2 childhood acute myeloid leukaemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 68, e29221. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.29221 (2021).

Egan, G. & Tasian, S. K. Precision medicine for high-risk gene fusions in pediatric AML: A focus on KMT2A, NUP98, and GLIS2 rearrangements. Blood 145, 2574–2586. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2024026598 (2025).

Faber, Z. J. et al. The genomic landscape of core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemias. Nat. Genet. 48, 1551–1556. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3709 (2016).

Ishikawa, Y. et al. Prospective evaluation of prognostic impact of KIT mutations on acute myeloid leukemia with RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and CBFB-MYH11. Blood Adv 4, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000709 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. Outcomes of children and adolescents with acute Myeloid Leukemia and KIT mutations treated with low- or standard-dose chemotherapy plus dasatinib on the CALSⅢ-AML18 trial. Blood 144, 6050–6050. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2024-211911 (2024).

Srinivasan, S. et al. KIT exon 17 mutations are predictive of inferior outcome in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia with RUNX1::RUNX1T1. Pediatr Blood Cancer 71, e30791. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.30791 (2024).

Pollard, J. A. et al. Sorafenib in combination with standard chemotherapy for children with high allelic ratio FLT3/ITD+ acute myeloid Leukemia: A report from the children’s oncology group protocol AAML1031. J Clin Oncol 40, 2023–2035. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.21.01612 (2022).

Gaidzik, V. I. et al. RUNX1 mutations in acute myeloid Leukemia: Results from a comprehensive genetic and clinical analysis from the AML study group. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 1364–1372. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2010.30.7926 (2011).

Tang, J.-L. et al. AML1/RUNX1 mutations in 470 adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: Prognostic implication and interaction with other gene alterations. Blood 114, 5352–5361. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-05-223784 (2009).

Yamato, G. et al. RUNX1 mutations in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia are associated with distinct genetic features and an inferior prognosis. Blood 131, 2266–2270. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-11-814442 (2018).

Sisoudiya, S. D. et al. Identification of USP9X as a leukemia susceptibility gene. Blood Adv. 7, 4563–4575. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2023009814 (2023).

Akiyama, H. et al. Inhibition of USP9X induces apoptosis in FLT3-ITD-positive AML cells cooperatively by inhibiting the mutant kinase through aggresomal translocation and inducing oxidative stress. Cancer Lett. 453, 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2019.03.046 (2019).

Yang, Y. L. et al. Treatment outcomes of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: A retrospective analysis from 1996 to 2019 in Taiwan. Sci Rep 11, 5893. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85321-3 (2021).

Inaba, H. et al. Comparative analysis of different approaches to measure treatment response in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 30, 3625–3632. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2011.41.5323 (2012).

Maurer-Granofszky, M. et al. Genomic breakpoint-specific monitoring of measurable residual disease in pediatric non-standard-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 109, 740–750. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2022.282424 (2024).

van der Velden, V. H. et al. Clinical significance of flowcytometric minimal residual disease detection in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia patients treated according to the DCOG ANLL97/MRC AML12 protocol. Leukemia 24, 1599–1606. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2010.153 (2010).

Liang, D. C. et al. Improved treatment results for childhood acute Myeloid leukemia in Taiwan. Leukemia 20, 136–141. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2403979 (2006).

Balgobind, B. V. et al. Integrative analysis of type-I and type-II aberrations underscores the genetic heterogeneity of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 96, 1478–1487. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2010.038976 (2011).

Yu, C.-H. et al. MLPA and DNA index improve the molecular diagnosis of childhood B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Rep. 10, 11501. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68311-9 (2020).

Yu, C. H. et al. TP53 alterations in relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Sci 111, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.14238 (2020).

Meshinchi, S. et al. Clinical implications of FLT3 mutations in pediatric AML. Blood 108, 3654–3661. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-03-009233 (2006).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 (2013).

Tian, L. et al. CICERO: A versatile method for detecting complex and diverse driver fusions using cancer RNA sequencing data. Genome. Biol. 21, 126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02043-x (2020).

Nicorici, D. et al. <strong>FusionCatcher</strong> – a tool for finding somatic fusion genes in paired-end RNA-sequencing data. bioRxiv, 011650, https://doi.org/10.1101/011650 (2014).

Ma, C., Shao, M. & Kingsford, C. SQUID: Transcriptomic structural variation detection from RNA-seq. Genome Biol. 19, 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-018-1421-5 (2018).

Melsted, P. et al. Fusion detection and quantification by pseudoalignment. bioRxiv, 166322, https://doi.org/10.1101/166322 (2017).

Haas, B. J. et al. Accuracy assessment of fusion transcript detection via read-mapping and de novo fusion transcript assembly-based methods. Genome Biol. 20, 213. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1842-9 (2019).

Ye, K., Schulz, M. H., Long, Q., Apweiler, R. & Ning, Z. Pindel: A pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics 25, 2865–2871. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp394 (2009).

McLeod, C. et al. St. Jude Cloud: A Pediatric Cancer Genomic Data-Sharing Ecosystem. Cancer Discov 11, 1082–1099, https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-20-1230 (2021).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 12, 323. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-323 (2011).

Law, C. W., Chen, Y., Shi, W. & Smyth, G. K. voom: Precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol 15, R29. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r29 (2014).

Becht, E. et al. Dimensionality reduction for visualizing single-cell data using UMAP. Nat Biotechnol https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4314 (2018).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0506580102 (2005).

Chang, T. C. et al. Genomic determinants of outcome in acute lymphoblastic Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 3491–3503. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.02238 (2024).

Chen, S. et al. A genomic mutational constraint map using variation in 76,156 human genomes. Nature 625, 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06045-0 (2024).

Chang, T. C., Xu, K., Cheng, Z. & Wu, G. Somatic and germline variant calling from next-generation sequencing data. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1361, 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91836-1_3 (2022).

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor D. C. Liang for his valuable contributions to the protocol design. We are also deeply grateful to all the patients who participated in this study and to their parents for their support and cooperation. The authors also acknowledge the data collection of the Childhood Cancer Foundation in Taiwan. We also thank the Pharmacogenomics Laboratory of the National Core Facility for Biopharmaceuticals, as well as the NGS and Microarray Core Facility of the NTU Centers of Genomic and Precision Medicine, for their technical support.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the (a) Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (110–2314-B-002–091-MY3 to YLY; NSTC-114–2740-B-002–002-, to SLY), (b) National Taiwan University (NTU-CC-109L 104704, to YLY), (c) National Taiwan University Hospital (110-L1007, to YLY), (d) US NCI Cancer Center Grant CA021765, and (e) American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZS.C., S.L.Y., C.H.Y., C.H.P., and Y.L.Y, conceived and designed the study; ZS.C., T.C.C, Y.H.C, and G.W., analyzed the RNA-seq and WES data; S.T.J., M.Y.L., K.H.L., H.H.C., S.W.C., C.J.D., and D.T.L. provided the samples; Z.E.L., C.W.K., P.T.L., Y.L.N., and S.W.L., did the experiments; C.Y.L., and H.Y.C., did the survival analysis; and all authors performed data analysis and interpretation, wrote the manuscript, and provided final approval of the manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board of National Taiwan University Hospital (REC number: 202207005RINB) approved this study. The parents, guardians, or patients signed the written informed consent in according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher‘s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, Z., Yu, SL., Yu, CH. et al. Genetic landscape of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia in Taiwan. Sci Rep 16, 4024 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34152-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34152-7