Abstract

With ongoing global warming, vegetation succession in alpine meadows has become increasingly prominent, substantially altering soil ecological processes. To investigate the patterns and regulatory mechanisms of soil nutrient, heavy metal, and microbial trait changes during vegetation succession, we selected a typical alpine vegetation succession sequence—ranging from grassland to shrubland to mixed forest—in Shangri-La, China. Using a space-for-time substitution approach, we systematically analyzed changes in soil nutrients, heavy metals, and microbial properties (including enzyme activities and microbial biomass) across different succession stages. Our results revealed significant differences in soil nutrients, heavy metals, and microbial characteristics along the succession gradient. Notably, soil enzyme activities, microbial biomass, and concentrations of Cu, Zn, Cr, As, and Cd were lowest in the shrubland co-dominated by Rhododendron racemosum Franch. And Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz. (G2). With the progression of vegetation succession, all measured soil nutrients—except for total potassium (TK)—including available potassium (AK), available phosphorus (AP), soil organic carbon (SOC), pH, total nitrogen (TN), and total phosphorus (TP), exhibited significant increases at the late successional stage, represented by the mixed forest co-dominated by Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz. and Picea asperata Mast. (QG). Soil nutrients and heavy metals jointly drove microbial dynamics, with their combined effects explaining 50.0% of the observed variation. Among these, heavy metals had a greater independent explanatory power (35.0%) than soil nutrients (11.3%). This study provides theoretical support and scientific evidence for understanding ecosystem stability mechanisms and guiding ecological restoration in climate-sensitive alpine regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Grasslands, as one of the most critical terrestrial ecosystems globally, play a vital role in maintaining ecological balance and supporting biodiversity1,2. However, due to the intensification of global climate change and anthropogenic disturbances, grassland degradation has become increasingly severe and is now a prominent challenge in global environmental and ecological research3. The United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021–2030) initiative4 advocates for halting and reversing ecosystem degradation to enhance global ecosystem stability and sustainability, thereby mitigating associated ecological and environmental risks. In grassland restoration and vegetation succession studies, plant–soil feedback mechanisms are recognized as key ecological processes that drive community succession and ecosystem functional shifts. These mechanisms provide theoretical guidance for ecosystem recovery and reconstruction5. Plants modify both biotic and abiotic soil conditions through root exudates, litter inputs, and interactions with soil microorganisms. Specifically, they influence soil properties by contributing organic matter and biochemical compounds, altering hydrological processes and surface soil temperature, and providing habitat or resources for micro- and macro-organisms6,7. In recent years, plant–soil feedbacks have been widely employed to explain both primary and secondary vegetation succession processes8, with growing contributions to understanding biodiversity maintenance and nutrient cycling.

Alpine meadow ecosystems are experiencing pronounced and long-lasting changes in surface morphology and hydrothermal conditions under the dual influence of climate warming and human disturbance9. These changes promote vegetation succession in alpine regions, often accompanied by patterns of either progressive development or degradation10. Climate-induced vegetation succession in alpine areas has led to declines in grassland quality, reduced aboveground biomass, and weakened carbon sink capacity, ultimately threatening ecosystem stability and sustainability10,11. Vegetation succession is a key ecological process that not only alters plant community composition but also influences energy flow and biogeochemical cycling within soil ecosystems12. Soil microbes, as integral components of plant–soil feedback systems, are deeply involved in these dynamic processes13. Successional changes in the quantity and quality of plant litter inputs can directly influence microbial biomass, soil enzyme activities, and nutrient availability14. Previous studies have demonstrated that succession can increase soil organic carbon and total nitrogen content while decreasing soil pH, with microbial biomass also rising along the succession gradient15. However, divergent results may arise from environmental heterogeneity across different succession stages16. Although many studies have examined soil properties and microbial changes during succession, most have focused on secondary succession17,18 and relatively short timescales, limiting our understanding of long-term ecosystem dynamics. In contrast, natural succession processes occurring under undisturbed conditions can more accurately reflect the persistent effects of vegetation changes on soil systems and aid in predicting long-term ecological trajectories19.

Shangri-La, located on the southeastern edge of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau within the Three-River-Source Region of the Hengduan Mountains, is a critical component of the ecological security barrier in southwestern China. It plays a crucial role in maintaining regional biodiversity and ecosystem stability20. The alpine meadow ecosystems in this area are undergoing notable natural succession, characterized by a gradual transition from meadows to shrublands and even to mixed forests. However, systematic studies on the interrelationships among soil nutrients, heavy metals, microbial biomass, and enzyme activity across different succession stages remain scarce. To address this knowledge gap, we applied a space-for-time substitution approach to investigate how soil physicochemical and microbial properties vary along a natural vegetation succession gradient. Specifically, we hypothesized that: (1) soil nutrient and heavy metal contents differ significantly across succession stages; (2) Microbial biomass and soil enzyme activities show distinct variation across different stages of vegetation succession; and (3) compared with heavy metals, soil nutrients are the primary drivers of microbial property changes. Our study helps to elucidate the changes in belowground ecological processes during alpine meadow succession, providing theoretical support and scientific evidence for understanding ecosystem stability in climate-sensitive regions.

Materials and methods

Study area overview

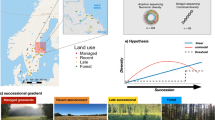

The study area is located in Jiantang Town, Shangri-La City, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (27°85′99″N, 99°75′01″E) (Fig. 1). This region lies on the southern edge of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and is characterized by a cold temperate monsoon climate with distinct features of a low-latitude plateau monsoon system. The elevation ranges from 2824 to 4554 m. The area receives an average annual precipitation of approximately 1300 mm, with a mean annual temperature of 5.5 °C, an average annual sunshine duration of 2180.3 h, and a frost-free period of about 121 days. The climate exhibits distinct dry and wet seasons, with the dry season occurring from November to April and the wet season from May to October. The region experiences large diurnal temperature variations and intense solar radiation. The dominant soil type in the region is meadow soil, and the vegetation type is subalpine meadow. Representative plant species include Stellera chamaejasme L., Poa annua L., Argentina lineata (Trevir.) Soják, Vincetoxicum forrestii (Schltr.) C. Y. Wu & D. Z. Li, Carex alatauensis S. R. Zhang, Rhododendron racemosum Franch., Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz., Juniperus squamata Buch.-Ham. ex D. Don, and Picea asperata Mast.

Study area location map. (The Review Number: GS (2024) 0650) The map was created using ArcGIS Pro software (version 3.1.5) (https://www.esri.com/zh-cn/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview) Abbreviations: CK, alpine meadow; G1, shrubland dominated by Rhododendron racemosum Franch.; G2, shrubland co-dominated by Rhododendron racemosum Franch. and Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz.; QG, mixed forest co-dominated by Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz. and Picea asperata Mast.

Plot design and soil sampling

This study was conducted in Lazha Village Group, Jiantang Town, Shangri-La City, within a typical vegetation succession zone. Plant species were formally identified by Dr. Wenguang Yang at the Plant Resource Survey, Evaluation and Identification Center, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Voucher specimens (KUN165821, KUN165822, KUN165823) are deposited in the Herbarium of the Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Herbarium code: KUN). An official identification report has been issued and is available upon request. To ensure the validity of the space-for-time substitution approach, we selected plots that were located in close proximity, under similar topographic and climatic conditions, and derived from the same parent material. Prior field surveys and geopedological investigations indicated that these sites shared comparable initial soil conditions before vegetation divergence. The different vegetation types represent stages of natural succession primarily driven by ecological processes such as species competition and environmental filtering. No major anthropogenic disturbances were identified in the selected sites, ensuring the reliability of the successional gradient. Based on field surveys, including assessments of geology, topography, and micro-geomorphology, four representative vegetation types along the succession gradient were selected. For each type, three 20 m × 20 m plots were established, with a distance of more than 10 m between plots. Within each plot, three 3 m × 3 m subplots were randomly arranged using a completely randomized block design, separated by 3 m buffer zones and access paths. The vegetation types represented four typical successional stages: alpine meadow (CK, control, representing the initial stage of succession); shrubland dominated by Rhododendron racemosum Franch. (G1, early successional stage); shrubland co-dominated by Rhododendron racemosum Franch. and Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz. (G2, mid-successional stage); and mixed forest co-dominated by Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz. and Picea asperata Mast. (QG, late successional stage). Soil sampling was carried out on June 22, 2024 (wet season). Surface litter was removed prior to soil collection. From each subplot, soil samples were collected at a depth of 0–20 cm using the five-point composite method. Samples from three replicates within each vegetation type were thoroughly homogenized and sieved to remove roots, then divided into two portions. One portion was stored at − 80 °C for the determination of microbial biomass and enzyme activities; the other was air-dried and sieved for soil physicochemical property analysis.

Soil analysis

Soil chemical properties were determined following the methods described by Bao21. Total nitrogen (TN) was measured using the semi-micro Kjeldahl method. Total phosphorus (TP), available phosphorus (AP), and total potassium (TK) were analyzed using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). Available potassium (AK) was determined using 1 mol·L⁻¹ neutral ammonium acetate and flame photometry. Soil organic carbon (SOC) was measured using the external heating potassium dichromate oxidation method. Soil pH was measured using a glass electrode with a soil-to-water ratio of 1:2.5 (w/v). Microbial biomass carbon (MBC), nitrogen (MBN), and phosphorus (MBP) were determined using the chloroform fumigation–extraction method. Absorbance measurements were performed using an Agilent Cary100 dual-beam UV spectrophotometer at wavelengths of 590 nm (MBC), 220 nm & 275 nm (MBN), and 880 nm (MBP). Soil enzyme activities, including sucrase (SC), urease (UE), and acid phosphatase (ACP), were measured using commercial assay kits provided by Suzhou Grace Biotechnology Co., Ltd., following the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance values were recorded at 540 nm for SC, 578 nm for UE, and 405 nm for ACP, respectively. Enzyme activities were calculated based on standard curves and expressed as follows: 1 mg of reducing sugar produced per gram of soil per day (SC), 1 µg of NH₃-N released per gram of soil per day (UE), and 1 nmol of p-nitrophenol (PNP) released per gram of soil per hour (ACP) were defined as one unit of enzyme activity, respectively.

Data analysis

Microbial biomass (MBC, MBN, and MBP) and the activities of the three enzymes were integrated as biological indicators to assess changes in soil ecological function across different successional stages. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 27.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA), with significance levels set at P < 0.05. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s multiple range test were used to evaluate differences in soil nutrients, heavy metals, and microbial properties among successional stages. Correlation analyses and visualizations were performed using the OmicStudio platform (https://www.omicstudio.cn). In R software (version 4.3.1; accessed on July 20, 2024, http://www.r-project.org/), the “vegan” 22 and “ggplot2” 23 packages were employed to calculate variance inflation factors (VIF) and eliminate multicollinear environmental variables. Redundancy analysis (RDA) was then conducted to identify key soil properties influencing microbial characteristics, with significance tested by permutation analysis. Variation partitioning analysis (VPA) was further used to quantify the relative contributions of multiple environmental factors to microbial variation.

Results

Soil nutrient characteristics at different successional stages

As shown in Fig. 2, soil nutrient characteristics varied significantly across different vegetation succession stages. Except for AP, all other nutrient indicators exhibited significant differences among successional stages (P < 0.05). Compared with the CK, the mixed forest stage QG had significantly higher levels of AK, SOC, TN, TP, and pH. In contrast, G2 exhibited the lowest values for most parameters except AK and TK. Notably, TK showed a decreasing trend along the successional gradient. Overall, soil nutrients tended to increase with vegetation succession, albeit with fluctuations, suggesting that succession significantly influenced nutrient accumulation and distribution in the soil.

Soil nutrient characteristics at vegetation succession stages. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among succession stages (P < 0.05). Abbreviations: CK, alpine meadow; G1, shrubland dominated by Rhododendron racemosum Franch.; G2, shrubland co-dominated by Rhododendron racemosum Franch. and Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz.; QG, mixed forest co-dominated by Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz. and Picea asperata Mast.; AK, available potassium; AP, available phosphorus; SOC, soil organic carbon; TN, total nitrogen; TP, total phosphorus; TK, total potassium.

Soil heavy metal characteristics at different successional stages

The concentrations of seven heavy metals were measured at each successional stage, revealing significant differences among vegetation types (P < 0.05; Fig. 3). Compared with CK, the levels of Cu, Zn, Cr, and As peaked in G1 and significantly declined in G2. Cd reached its lowest concentration in G2, while Hg showed a continuous increase across succession stages, peaking in QG. Pb exhibited the highest concentration in G2 and an overall increasing trend. These findings indicate that vegetation succession may influence the accumulation and migration of heavy metals in soils.

Changes in soil heavy metal concentrations across different vegetation succession stages. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among succession stages (P < 0.05). Abbreviations: CK, alpine meadow; G1, shrubland dominated by Rhododendron racemosum Franch.; G2, shrubland co-dominated by Rhododendron racemosum Franch. and Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz.; QG, mixed forest co-dominated by Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz. and Picea asperata Mast.

Changes in soil microbial characteristics during vegetation succession

Soil microbial characteristics, including enzyme activities (SC, UE, ACP) and microbial biomass (MBC, MBN, MBP), varied significantly across succession stages (P < 0.05; Fig. 4). Specifically, all enzyme activities and microbial biomass indicators were significantly elevated in G1 compared with CK, but declined sharply in G2. In QG, MBC and MBN reached their highest values. These results suggest distinct stage-specific variations in microbial traits during vegetation succession.

Characteristics of microorganisms across different vegetation succession stages. (a–c) Soil enzyme activities, (d–f) Soil microbial biomass. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among succession stages (P < 0.05). Abbreviations: CK, alpine meadow; G1, shrubland dominated by Rhododendron racemosum Franch.; G2, shrubland co-dominated by Rhododendron racemosum Franch. and Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz.; QG, mixed forest co-dominated by Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz. and Picea asperata Mast. SC, Soil Sucrase; UE, Soil Urease; ACP, Soil Acid Phosphatase. MBC, Microbial Biomass Carbon; MBN, Microbial Biomass Nitrogen; MBP, Microbial Biomass Phosphorus.

Relationships among soil Nutrients, heavy metals, and microbial characteristics

Multidimensional visualization analyses revealed the differential regulatory mechanisms of soil nutrients and heavy metals on microbial characteristics (Fig. 5). Correlation analysis (Fig. 5a) showed significant relationships among soil nutrients, heavy metals, and microbial traits. SC and UE were positively correlated with TP, Cu, Zn, As, and Cr, and negatively correlated with Pb. ACP showed significant positive correlations with SOC, TN, TP, Cu, Cd, and Cr, indicating that both nutrients and metals may jointly influence soil enzyme activity. MBC and MBN were significantly positively correlated with pH, AK, SOC, TN, TP, Hg, and Cd, while MBP was not significantly associated with soil nutrients but was positively correlated with Cu, Zn, and As. These results suggest that nutrient accumulation may promote microbial growth. Redundancy analysis (RDA, Fig. 5b) indicated significant relationships between microbial characteristics and environmental factors, with RDA1 and RDA2 explaining 67.33% and 26.87% of the variation, respectively. Samples from different vegetation types were clearly separated, indicating marked differences in soil properties and microbial traits across successional stages. Variation partitioning analysis (VPA, Fig. 5c) revealed that soil nutrients and heavy metals together explained 50.0% of the variation in microbial traits, with nutrients accounting for 11.3%, heavy metals for 35.0%, and unexplained variation only 3.7%. These results suggest that heavy metals exert a stronger influence than nutrients on microbial communities and that the two factors interact significantly.

Relationship between soil properties and microbial characteristics. (a) The relationship analysis between soil nutrients, heavy metals and soil microbial properties. (b) Relationships between soil nutrients, heavy metals and enzyme activities, microbial biomass according to RDA (Redundancy Analysis). (c) Variance partition analysis (VPA) shows the effect of soil nutrients, heavy metals on the variance of microbial characteristics. Abbreviations: SC, Soil Sucrase; UE, Soil Urease; ACP, Soil Acid Phosphatase. MBC, Microbial Biomass Carbon; MBN, Microbial Biomass Nitrogen; MBP, Microbial Biomass Phosphorus; AK, available potassium; AP, available phosphorus; SOC, soil organic carbon; TN, total nitrogen; TP, total phosphorus; TK, total potassium.

Discussion

Changes in soil nutrients, heavy metals and microbial characteristics during vegetation succession

Consistent with our initial hypothesis (1), our findings demonstrate significant differences in soil nutrient contents and heavy metal concentrations across vegetation successional stages. Vegetation succession represents a bidirectional interaction between plants and soil, in which plants affect the accumulation, distribution, and availability of soil elements through root exudates and litter inputs, while soil properties in turn influence plant growth and community structure24. Research in the hilly Loess Plateau has shown that soil nutrient levels during succession often exhibit a pattern of initial decline followed by a subsequent increase25, which aligns with our observations—soil AK, SOC, TN, TP, and pH were all significantly higher in the QG stage compared to other stages. This trend may be attributed to minimal human disturbance, greater vegetation cover, and increased litter input at the QG stage, which together improved soil properties and structure while reducing nutrient loss24. Moreover, different vegetation types exert distinct influences on soil quality, though the magnitude and mechanisms of improvement vary26, further highlighting the critical role of succession in regulating soil ecological functions. TK showed a consistent decline along the successional gradient, likely due to increasing plant biomass and root density associated with more structurally complex communities, thereby enhancing plant demand for potassium. As a highly mobile nutrient, potassium is readily taken up and sequestered in plant tissues, leading to gradual depletion in the soil during long-term nutrient cycling27.

Soil heavy metals are widely distributed in the environment and may pose potential threats to plant growth. Studies have shown that elevated heavy metal concentrations negatively impact plant diversity28. Interestingly, our results indicated significant reductions in Cu, Zn, Cr, As, and Cd in the G2 stage. Previous studies suggest that plants can take up heavy metals in soluble forms and facilitate their dissolution through root exudates29, thereby decreasing soil concentrations. The variation in heavy metal levels among successional stages may also reflect differences in plant species composition and their specific uptake capacities30. In contrast, soil Hg content increased significantly along the successional gradient, reaching a peak in the QG stage. This trend may result from greater aboveground biomass and litter input during later successional stages. Litterfall has been recognized as a key vector for atmospheric Hg deposition into soils, and its decomposition can release Hg, contributing to accumulation in the soil profile31,32. Furthermore, the slow decomposition rates of litter in alpine ecosystems likely promote Hg retention. Our study also revealed a significant positive correlation between SOC and soil Hg content, suggesting a potential association between higher SOC levels and Hg accumulation. Previous studies have indicated that soil organic matter plays an important role in regulating Hg distribution in terrestrial ecosystems33. For instance, research on forest soils in the Qinling Mountains of China has shown that organic matter exhibits a strong geochemical affinity for Hg, potentially promoting its retention and accumulation in soils34.

Our study revealed significant differences in enzyme activities and soil microbial biomass across successional stages, displaying distinct patterns during vegetation succession. These findings indicate that vegetation succession exerts substantial influence on microbial activity and functional potential, supporting our second hypothesis that soil enzyme activity and microbial biomass exhibit stage-specific variation during succession. Soil enzyme activities, which reflect microbial metabolic demand and the biochemical potential for organic matter turnover, are widely employed as indicators of microbial activity and nutrient cycling capacity35,36, Microbial biomass, on the other hand, is a sensitive proxy for changes in soil carbon and nitrogen reservoirs37. Generally, enzyme activities and microbial biomass are higher in forest ecosystems compared to grasslands and shrublands38, a pattern also observed in our study, where MBC and MBN increased with succession. However, the activities of all three enzymes and MBP were significantly higher in the G1 stage than in the QG stage. This could be attributed to differences in plant species and community composition, which influence litter quality and subsequent decomposition dynamics39. Plants can also regulate enzyme activities indirectly by releasing root exudates, exogenous enzymes, and oxygen into the rhizosphere40. The notably higher enzyme activities in the G1 stage may therefore be linked to specific litter chemistry or rhizosphere effects of Rhododendron racemosum Franch. In contrast, both enzyme activities and microbial biomass were lower in the G2 stage, possibly due to the high lignin and tannin content of Quercus monimotricha (Hand.-Mazz.) Hand.-Mazz. litter, which decomposes slowly and inhibits microbial activity41. Additionally, the root systems of this species may exhibit allelopathic effects and compete strongly with Rhododendron racemosum Franch. for soil nutrients, further suppressing rhizosphere microbial activity and biomass accumulation42.

Environmental drivers of microbial changes across different successional stages

By integrating correlation analysis, redundancy analysis (RDA), and variation partitioning analysis (VPA), we systematically explored the relative contributions of soil nutrients and heavy metals to variations in microbial properties (Fig. 5). Although previous studies have commonly identified soil nutrients as the dominant drivers of microbial biomass and metabolic activity43, our results showed that heavy metals independently explained 35.0% of the variation in microbial traits, significantly more than the 11.3% explained by soil nutrients, contradicting our third hypothesis. This unique pattern may be linked to the specific environmental conditions of alpine ecosystems, where low temperatures and slow organic matter decomposition promote heavy metal accumulation in soils. Soil microorganisms in these environments are highly sensitive to metals such as Cr, Cd, As, and Cu, which can disrupt microbial activity by inhibiting intracellular enzyme systems, inducing oxidative stress, and damaging cell membranes44. The importance of these stressors is particularly evident in the mid-successional stage (G2), where both microbial biomass and enzyme activities reached their lowest levels. Our RDA results further revealed that the dominant environmental drivers of microbial traits varied across successional stages. In the initial and early stages (CK and G1), microbial traits were closely associated with TK, Cu, As, and Cr, likely due to high nutrient cycling rates and rapid litter turnover, which release large quantities of organic acids and nutrients. These substances may reduce the bioavailability of metals through chelation or adsorption processes45,46. In contrast, in the middle stage of succession (G2), the correlation between microbial traits and most of the environmental factors was relatively weak, a phenomenon that may reflect the transitional state of vegetation structure at this stage, increased competition among species, and decreased decomposition rate and poor quality of apoplastic materials, leading to insufficient supply of soil carbon sources, which inhibited microbial activity. At the same time, the elevated concentrations of some heavy metals (Pb and Hg) in the soil at this stage may also have a negative impact on the microbial community. This “low biomass-high stress” characteristic suggests that microbial processes in the G2 stage may be limited by both nutrient supply and heavy metal stress. During the late successional (QG) period, microbial traits such as MBC and MBN were more significantly correlated with SOC and Cd, and the accumulation of SOC may have supported the increase in microbial biomass by providing more available carbon sources. However, the synchronized accumulation of Cd may have caused chronic stress to the microbial community, counteracting to some extent the positive facilitating effect of SOC47,48, and these differences in successional stages reflect a gradual shift in the dominant regulatory mechanism of the microbial processes from being driven by nutrient inputs in the early stages to a composite mechanism that is co-regulated by organic matter accumulation and heavy metal deposition. This temporal shift in key environmental drivers highlights that microbial dynamics are not regulated uniformly throughout the successional process. Instead, they exhibit a dynamic pattern characterized by early-stage control via rapid resource cycling and rhizosphere inputs, and late-stage regulation through organic matter accumulation and metal-induced stress. Previous studies have also shown that microbial community structure and function are jointly governed by heavy metal concentrations and soil physicochemical properties49. Our VPA results further support this view, showing that the combined effects of soil nutrients and heavy metals accounted for 50.0% of the total variation in microbial traits. The RDA analysis also confirmed their synergistic influence on microbial processes. This is likely because soil nutrients serve as essential resources for microbial growth and metabolism, while heavy metals act as environmental stressors that modify microbial composition, activity, and enzymatic function. Their interactions may regulate both resource availability and physiological stress simultaneously, thereby influencing microbial communities in synergistic or antagonistic ways50.

Conclusion

Overall, our study elucidates the dynamics and regulatory mechanisms of soil nutrients, heavy metals, enzyme activities, and microbial biomass across different vegetation successional stages in an alpine meadow ecosystem. All measured soil properties exhibited significant variation along the successional gradient, with nutrients generally increasing over time, while certain heavy metals, enzyme activities, and microbial biomass reached their lowest levels in the G2 stage. The results of this study support Hypotheses 1 and 2. However, contrary to Hypothesis 3, heavy metals exerted a stronger influence on microbial traits than soil nutrients. Notably, the variation in microbial characteristics was jointly driven by soil nutrients and heavy metals, with heavy metals playing a predominant role. Our findings reveal the patterns of belowground ecological processes across different stages of vegetation succession in alpine meadows, highlighting the key roles of soil nutrients and heavy metals in shaping microbial characteristics. These results provide a basis for understanding how ecosystem functions evolve during vegetation succession in alpine environments. Future studies should incorporate long-term field monitoring and molecular approaches to better understand microbial community succession and functional responses across temporal and spatial scales.

Data availability

The author confirms that all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. The data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Fan, F., Liang, C., Tang, Y., Harker-Schuch, I. & Porter, J. R. Effects and relationships of grazing intensity on multiple ecosystem services in the inner Mongolian steppe. Sci. Total Environ. 675, 642–650 (2019).

Zhang, R., Feng, Q., Zhang, Y., Mai, J. & Liang, T. Estimation and trend analysis of grassland aboveground biomass on the Qinghai-Xizang plateau based on machine learning. Ecol. Indic. 177, 113715 (2025).

Bardgett, R. D. et al. Combatting global grassland degradation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 720–735 (2021).

Geekiyanage, N. U. N. & Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021–2030: Are we ready for the grand challenge? Sri Lankan J. Agric. Ecosyst. 4 (2022).

Hou, Y., Zhao, W., Zhan, T., Hua, T. & Pereira, P. Alpine meadow and alpine steppe plant-soil network in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Catena 244, 108235 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Restoration of degraded alpine meadows from the perspective of plant–soil feedbacks. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 60, 941–953 (2024).

Van der Putten, W. H. et al. Plant–soil feedbacks: the past, the present and future challenges. J. Ecol. 101, 265–276 (2013).

Florianová, A. et al. Plant–soil interactions in the native range of two congeneric species with contrasting invasive success. Oecologia 201, 461–477 (2023).

Balser, A. W., Jones, J. B. & Gens, R. Timing of retrogressive thaw slump initiation in the Noatak Basin, Northwest Alaska, USA. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 119, 1106–1120 (2014).

Wu, M. H. et al. Soil microbial distribution and assembly are related to vegetation biomass in the alpine permafrost regions of the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 834, 155259 (2022).

Tang, L. et al. Changes in vegetation composition and plant diversity with rangeland degradation in the alpine region of Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Rangel. J. 37, 107–115 (2014).

Jiang, S. et al. Changes in soil bacterial and fungal community composition and functional groups during the succession of boreal forests. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 161, 108393 (2021).

Shang, W. et al. Seasonal variations in labile soil organic matter fractions in permafrost soils with different vegetation types in the central Qinghai–Tibet plateau. Catena 137, 670–678 (2016).

Smith, A. P., Marín-Spiotta, E. & Balser, T. Successional and seasonal variations in soil and litter microbial community structure and function during tropical postagricultural forest regeneration: A multiyear study. Global Change Biol. 21, 3532–3547 (2015).

Wang, W. et al. Effects of vegetation succession on soil microbial communities on karst mountain peaks. Forests 15, 586 (2024).

Seabloom, E. W., BJøRNSTAD, O. N., Bolker, B. M. & Reichman, O. J. Spatial signature of environmental heterogeneity, dispersal, and competition in successional grasslands. Ecol. Monogr. 75, 199–214 (2005).

Zhou, Z., Wang, C., Jiang, L. & Luo, Y. Trends in soil microbial communities during secondary succession. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 115, 92–99 (2017).

Lee, H. et al. Successional variation in the soil microbial community in Odaesan National Park, Korea. Sustainability 12, 4795 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Microbes require a relatively long time to recover in natural succession restoration of degraded grassland ecosystems. Ecol. Indic. 129, 107881 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Spatiotemporal evolution and attribution analysis of ecological quality in the alpine meadow region of Shangri-La based on natural-social dimensions. Sci. Rep. 15, 29 (2025).

Bao, S. D. Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis (China Agricultural, 2000).

Oksanen, J. et al. Package ‘vegan’. Comm. Ecol. Package Version 2, 1–295 (2013).

Wickham, H., Chang, W. & Wickham, M. H. Package ‘ggplot2’. Create Elegant Data Vis. Using Gramm. Graph. Version. 2, 1–189 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Long-term forest succession improves plant diversity and soil quality but not significantly increase soil microbial diversity: Evidence from the loess plateau. Ecol. Eng. 142, 105631 (2020).

Gu, M., Liu, S., Duan, H., Wang, T. & Gu, Z. Dynamics of community biomass and soil nutrients in the process of vegetation succession of abandoned farmland in the loess plateau. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 580775 (2021).

Yu, P., Liu, S., Zhang, L., Li, Q. & Zhou, D. Selecting the minimum data set and quantitative soil quality indexing of alkaline soils under different land uses in Northeastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 616, 564–571 (2018).

Sardans, J. & Peñuelas, J. 10, 419 (2021).

Narayanan, M. & Ma, Y. Mitigation of heavy metal stress in the soil through optimized interaction between plants and microbes. J. Environ. Manag. 345, 118732 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Organic acid compounds in root exudation of Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys pubescens) and its bioactivity as affected by heavy metals. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 23, 20977–20984 (2016).

Khan, I. et al. Effects of silicon on heavy metal uptake at the soil-plant interphase: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 222, 112510 (2021).

Guo, W. et al. Warming-Induced vegetation greening May aggravate soil mercury levels worldwide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 15078–15089 (2024).

Lim, A. G. et al. A revised pan-Arctic permafrost soil hg pool based on Western Siberian peat hg and carbon observations. Biogeosciences 17, 3083–3097 (2020).

Obrist, D. et al. Mercury distribution across 14 US forests. Part I: Spatial patterns of concentrations in biomass, litter, and soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 3974–3981 (2011).

Ma, H. et al. Distribution of mercury in foliage, litter and soil profiles in forests of the Qinling Mountains, China. Environ. Res. 211, 113017 (2022).

Wang, B. et al. Changes in soil nutrient and enzyme activities under different vegetations in the loess plateau area, Northwest China. Catena 92, 186–195 (2012).

Wang, L. et al. Using enzyme activities as an indicator of soil fertility in grassland-an academic dilemma. Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 1175946 (2023).

dos Bastos, S., Barreto-Garcia, T. R., de Carvalho Mendes, P. A. B., Monroe, I., de Carvalho, F. F. Response of soil microbial biomass and enzyme activity in coffee-based agroforestry systems in a high-altitude tropical climate region of Brazil. Catena 230, 107270 (2023).

Liu, G. et al. Soil enzyme activities and microbial nutrient limitation during the secondary succession of boreal forests. Catena 230, 107268 (2023).

Song, Y. et al. Linking plant community composition with the soil C pool, N availability and enzyme activity in boreal peatlands of Northeast China. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 140, 144–154 (2019).

Ma, W., Li, G., Wu, J., Xu, G. & Wu, J. Response of soil labile organic carbon fractions and carbon-cycle enzyme activities to vegetation degradation in a wet meadow on the Qinghai–Tibet plateau. Geoderma 377, 114565 (2020).

Wan, X., Yu, Z., Wang, M., Zhang, Y. & Huang, Z. Litter and root traits control soil microbial composition and enzyme activities in 28 common subtropical tree species. J. Ecol. 110, 3012–3022 (2022).

Ma, W. et al. Root exudates contribute to belowground ecosystem hotspots: A review. Front. Microbiol. 13, 937940 (2022).

Xu, Z. et al. Soil nutrients and nutrient ratios influence the ratios of soil microbial biomass and metabolic nutrient limitations in mountain peatlands. Catena 218, 106528 (2022).

Dai, Z. C. et al. Cadmium hyperaccumulation as an inexpensive metal armor against disease in Crofton weed. Environ. Pollut. 267, 115649 (2020).

Ginocchio, R. et al. Micro-spatial variation of soil metal pollution and plant recruitment near a copper smelter in central Chile. Environ. Pollut. 127, 343–352 (2004).

Zhen, Z. et al. Significant impacts of both total amount and availability of heavy metals on the functions and assembly of soil microbial communities in different land use patterns. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2293 (2019).

Hao, X. et al. Cadmium speciation distribution responses to soil properties and soil microbes of plow layer and plow Pan soils in cadmium-contaminated paddy fields. Front. Microbiol. 12, 774301 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. Effects of heavy metals and soil physicochemical properties on wetland soil microbial biomass and bacterial community structure. Sci. Total Environ. 557, 785–790 (2016).

Jiang, Y. et al. Responses of microbial community and soil enzyme to heavy metal passivators in cadmium contaminated paddy soils: an in situ field experiment. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 164, 105292 (2021).

Zhang, F., Xie, Y., Peng, R., Ji, X. & Bai, L. Heavy metals and nutrients mediate the distribution of soil microbial community in a typical contaminated farmland of South China. Sci. Total Environ. 947, 174322 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the project of the China Geological Survey (No. DD20230482) and the Science and Technology Innovation Foundation of Survey Center of Comprehensive Natural Resources (KC20230021). The sequence of funding sources has been adjusted accordingly and revised to: This work was supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Foundation of Survey Center of Comprehensive Natural Resources (KC20230021) and the project of the China Geological Survey (No. DD20230482).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZH: Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – Original draft, Writing - review & editing. CD and ZL: Conceptualization, Visualization, Methodology, Data curation. RL and KZ: Investigation, Methodology, Data curation. YL, PL and HW: Investigation, Validation, Software. MY: Resources, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration. YZ: Project administration, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, Z., Dong, C., Li, Z. et al. Vegetation changes drive alterations in soil nutrients, heavy metals and microbial traits in alpine meadows. Sci Rep 16, 4048 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34172-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34172-3